Introduction

Autophagy and mitophagy are fundamental processes that play a crucial role in cellular maintenance, stress response and ageing(Reference Palmer, Wilson and Son1, Reference Picca, Faitg and Auwerx2). Both processes involve the degradation and recycling of cellular components, with autophagy targeting damaged or redundant cell organelles, and mitophagy focusing specifically on dysfunctional mitochondria. In recent years, attention has turned to two promising compounds, urolithin A (UroA) and spermidine, which have been shown to enhance these pathways and offer potential benefits for human health. Urolithin A is a metabolite derived from ellagitannins found in foods such as pomegranates, whereas spermidine is a naturally occurring polyamine found in various plant-based foods such as wheat germ and soyabeans. There have been several in vitro studies with both compounds that have traced their involvement in autophagy and mitophagy, as well as in vivo studies confirming the positive health effects of supplementation with UroA and spermidine(Reference Kuerec, Lim and Khoo3, Reference Arthur, Jamwal and Kumar4).

Urolithin A and spermidine have garnered interest as potential anti-ageing supplements(Reference Kothe, Klein and Petrosky5, Reference Hofer, Daskalaki and Bergmann6). However, the critical question remains: which of these compounds offers the most substantial benefits for human health, particularly as a dietary supplement? The objective of this article is to critically assess the comparative advantages of UroA and spermidine, with focus on their respective roles in cellular health, longevity and clinical application.

Urolithin A: sources, dosage and mechanism of action

Urolithin A is a metabolite produced by the gut microbiota through the transformation of ellagitannins, a class of polyphenols commonly found in fruits such as pomegranates, raspberries, strawberries and nuts, especially walnuts. The metabolic conversion occurs through microbial fermentation in the gastrointestinal tract, primarily involving bacterial species such as Proteobacteria, Clostridium, and Bifidobacterium (Reference Hua, Wu and Yang7). The biotransformation of ellagitannins and ellagic acid into urolithins has been characterised in several pivotal studies that established the foundation for contemporary research on urolithin A. Cerdá et al. initially demonstrated that specific human gut microbial consortia convert ellagic acid into urolithins, thereby highlighting pronounced interindividual variability in metabolite profiles(Reference Cerdá, Espín and Parra8). Subsequently, Seeram et al. provided the earliest in vivo confirmation that urolithin metabolites appear in human plasma and urine following the consumption of ellagitannin-rich foods, thereby establishing the relevance of these compounds for human nutrition(Reference Seeram, Henning and Zhang9). These findings were subsequently synthesised and expanded upon by Espín et al., who presented the first comprehensive review of the biological significance, metabolic pathways and emerging physiological roles of urolithins(Reference Espín, González-Barrio and Cerdá10). Collectively, these foundational studies provide essential context for understanding the origin, metabolism and translational relevance of urolithin A as discussed in modern mechanistic and clinical research.

However, not all individuals produce UroA efficiently owing to variations in gut microbiome composition, which has led to the development of direct supplementation strategies to achieve consistent levels across different populations(Reference Singh, D’Amico and Andreux11).

This interindividual variability has led to the classification of three urolithin metabotypes: the UM-A strain is distinguished by its predominant production of urolithin A, while the UM-B strain produces urolithins A and B, along with their isomers. In contrast, the UM-0 strain exhibits a complete absence of urolithin production. These metabotypes exhibit variation in their prevalence across different age demographics and populations. They have been associated with distinct metabolic and inflammatory phenotypes. Notably, these factors also influence the physiological and potentially clinical response to urolithin A, as individuals with UM-A generally achieve higher endogenous exposure compared with those with UM-B or UM-0. The concept was originally defined by Cortés-Martín et al. (Reference Cortés-Martín, García-Villalba and González-Sarrías12), and was subsequently expanded upon in a following publication that demonstrated the relevance of urolithin-based metabotyping in the interpretation of the effects of polyphenol-rich diets and microbiome-dependent nutraceutical interventions(Reference Meroño, Peron and Gargari13). Therefore, incorporating this metabotype framework is essential for understanding the personalised effects and translational relevance of urolithin A supplementation.

The typical supplemental dosage of UroA ranges between 500 mg and 1000 mg per day, which has demonstrated effective bioavailability in humans. This dosage results in a dose-dependent increase in plasma concentrations of UroA and its glucuronide and sulfate conjugates, supporting its physiological activity in target tissues, particularly muscles and their mitochondria(Reference Andreux, Blanco-Bose and Ryu14). UroA’s bioavailability is higher when consumed in encapsulated or liposomal forms, which enhances its absorption compared with dietary sources alone(Reference Ryu, Mouchiroud and Andreux15).

The primary action of UroA centres around its ability to induce mitophagy and autophagy. Research suggests that UroA is more potent in inducing mitophagy than autophagy (see later). Mitophagy is a process by which damaged mitochondria are selectively degraded and recycled to maintain mitochondrial quality. This mechanism is critical for energy metabolism, particularly in tissues with high energy demands such as skeletal muscle. Urolithin A activates the PTEN induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PRKN) pathway, which tags dysfunctional mitochondria for degradation, while also stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis via the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) signalling axis(Reference Ryu, Mouchiroud and Andreux15). These combined effects result in improved mitochondrial function, increased ATP production and enhanced muscle endurance, making UroA particularly effective in combating age-related mitochondrial dysfunction(Reference Liu, D’Amico and Shankland16).

By contrast, autophagy is a process that involves complex molecular interactions and performs key functions in cellular homeostasis, adaptation and cell survival. The detailed mechanisms of autophagy are further discussed in relation to spermidine and in the following text.

In addition to its role in mitophagy and autophagy, UroA exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Research demonstrates that UroA modulates the inflammatory response by reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and increasing the production of anti-inflammatory markers such as IL-10. Furthermore, it enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase, thereby reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protecting cells from oxidative damage(Reference Liu, D’Amico and Shankland16). These properties not only support mitochondrial health but also contribute to UroA’s potential to reduce the risk of chronic inflammatory diseases and support overall cellular longevity. Recent in vivo studies have further demonstrated UroA’s efficacy in extending lifespan and improving muscle function in animal models. For instance, administration of UroA to Caenorhabditis elegans led to a significant extension of lifespan, while rodent studies showed enhanced muscle endurance and reduced signs of muscle ageing(Reference Ryu, Mouchiroud and Andreux15). Human subject clinical trials have also shown promising results, with older adults experiencing improved muscle strength and endurance following supplementation, highlighting UroA’s potential as a therapeutic agent for age-related muscle decline(Reference Singh, D’Amico and Andreux17).

In summary, UroA offers a potent mechanism for targeting mitochondrial health through mitophagy, which not only supports muscle function but also plays a critical role in cellular health, inflammation control and oxidative stress reduction. These characteristics position UroA as a promising candidate for dietary supplementation, particularly for individuals aiming to enhance mitochondrial function and mitigate the effects of ageing.

Spermidine: sources, dosage and mechanism of action

Spermidine is a naturally occurring polyamine that is ubiquitously found in various organisms, including humans. It is abundant in plant-based foods such as wheat germ, soyabeans, mushrooms and aged cheese. Spermidine plays a crucial role in cellular processes such as DNA stabilisation, regulation of gene expression and modulation of cell growth and proliferation. However, its levels decline with age, sparking interest in spermidine supplementation as a means of supporting healthy ageing(Reference Madeo, Carmona-Gutierrez and Kepp18). Spermidine supplementation is typically administered through extracts from polyamine-rich plant sources, with dosages varying depending on the formulation. Clinical trials commonly use doses of 750 mg of spermidine-rich plant extract, corresponding to approximately 1·2 mg of pure spermidine per day(Reference Schwarz, Horn and Benson19). Higher doses, such as 15 mg/d, have also been tested in short-term studies, though these did not significantly increase plasma spermidine levels owing to pre-systemic conversion into other polyamines, such as spermine(Reference Senekowitsch, Wietkamp and Grimm20).

Spermidine’s primary health benefit arises from its ability to induce autophagy. Autophagy is a conserved fundamental mechanism used by cells to maintain homeostasis; remove damaged or unnecessary organelles, proteins, and other cellular debris, as well as pathogens, and toxins; and respond to stress conditions such as nutrient deprivation. By doing so, autophagy plays a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and has been implicated in the regulation of ageing and longevity. Spermidine enhances autophagy by modulating several key signalling pathways, including the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway and the SIRT1 pathway, both of which are central regulators of energy metabolism, stress responses and cellular longevity(Reference Jeong, Cha and Han21). Moreover, spermidine inhibits histone acetyltransferase p300 (EP300), a protein that suppresses autophagy, thereby enabling the activation of autophagy-related genes (Atg)(Reference Madeo, Carmona-Gutierrez and Kepp18).

Beyond its autophagic role, spermidine also influences other cellular processes, including mitophagy, which is the selective removal of damaged mitochondria. Studies have shown that spermidine activates the PINK1/PRKN mitophagy pathway, similar to UroA, but spermidine’s broader effects on autophagy extend its impact to other organelles and cellular components(Reference Eisenberg, Knauer and Schauer22). These effects contribute to its ability to protect against oxidative stress, reduce inflammation and improve overall cellular health. In addition, spermidine has been shown to reduce the accumulation of ROS and enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and catalase, thereby mitigating oxidative damage at the cellular level(Reference Jeong, Cha and Han21).

The benefits of spermidine extend to various systems of the body, with particular influence on neuroprotective effects. Animal studies indicate that spermidine supplementation improves cognitive function, delays neurodegeneration and protects neurons from apoptosis by enhancing autophagy and reducing inflammation in the brain. These effects are mediated through the activation of autophagy-related proteins, such as microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) and Beclin-1 (BECN1), and the reduction of pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-1β and TNF-α(Reference Xu, Li and Dai23). Furthermore, spermidine’s impact on neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity suggests its potential to mitigate age-related cognitive decline and improve memory function in both animals and humans(Reference Schwarz, Horn and Benson19).

In summary, spermidine is a potent inducer of autophagy and mitophagy with broad cellular benefits, ranging from neuroprotection to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Its role in maintaining cellular homeostasis, promoting cognitive health, and reducing the risk of age-related diseases makes it a valuable candidate for dietary supplementation. Spermidine’s ability to modulate key signalling pathways involved in cellular longevity, combined with its accessibility through dietary sources and supplementation, supports its growing popularity as an anti-ageing nutraceutical.

Urolithin A and spermidine in autophagy and mitophagy: studies in vitro

The mechanism of autophagy involves the formation of double-membraned vesicles, called autophagosomes, that sequester damaged organelles, proteins, etc. The autophagosome fuses with lysosomes and its contents are degraded by enzymes. Breakdown products (lipids, saccharides and amino acids) can be recycled and reused as energy sources or for building new cellular components(Reference Aman, Schmauck-Medina and Hansen24).

Within autophagy, several distinct types can be distinguished: macroautophagy, microautophagy (including selective autophagy such as mitophagy) and chaperone-mediated autophagy.

Autophagy can be induced by nutrient deprivation, which activates AMPK (a sensor of energy depletion) and inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR, an autophagy suppressor), as well as oxidative stress, hypoxia, exercise, drugs (rapamycin, metformin) and hormones (glucagon). Natural substances can also induce autophagy. Besides UroA and spermidine, resveratrol can also be mentioned as an example(25).

Numerous studies have confirmed that compromised autophagy and mitophagy are associated with ageing, leading to shortened lifespan in a wide range of ageing models, whereas restoration and enhancement of autophagy prolongs life and health in various animal species(Reference Aman, Schmauck-Medina and Hansen24, Reference Zimmermann, Madeo and Diwan26).

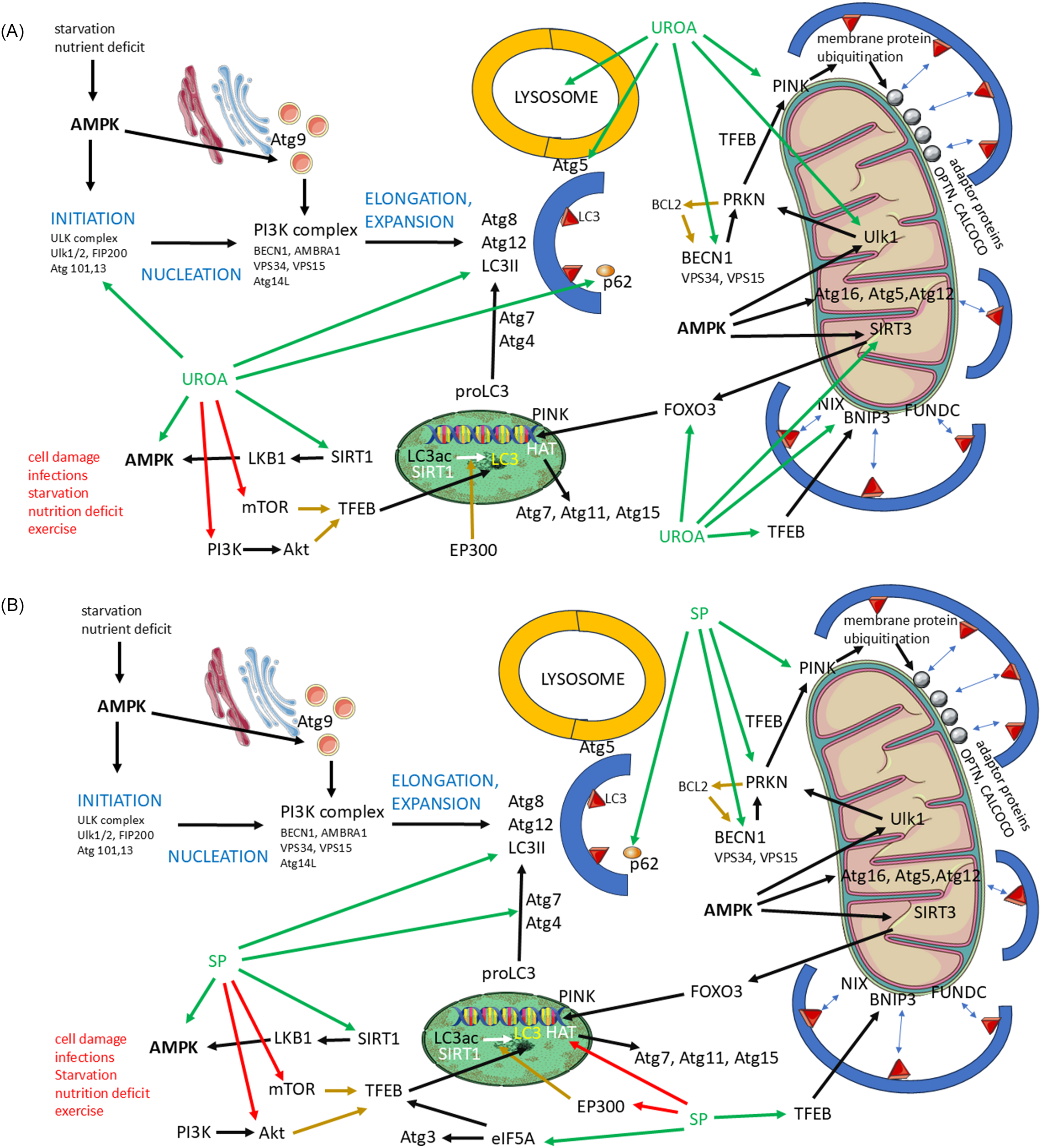

Both autophagy and mitophagy proceed through multiple steps, during which the autophagosome is formed and enlarged. The autophagosome is subsequently fused with the lysosome to allow degradation of the sequestered material (Fig. 1)(Reference Lamark and Johansen27).

Fig. 1 Involvement of urolithin A and spermidine in autophagy and mitophagy. (A) Diagram of Urolithin A involvement in autophagy and mithophagy. (B) Diagram of Spermidine involvement in autophagy and mitophagy. UroA/spermidine (SP): green arrows, positive influence (induction/activation/increase activity); red arrows, negative influence (block function, block synthesis). Other factors: black arrows, positive influence; brown arrows, negative influence. Abbreviations: Akt, protein kinase B; AMBRA1, activating molecule in Beclin-1-regulated autophagy; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; Atg, autophagy-related genes; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BECN1, Beclin-1; BNIP3, BCL2 interacting protein 3; CALCOCO, calcium-binding and coiled-coil domain-containing protein; EIF5A, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A; EP300, E1A binding protein p300; FIP200, focal adhesion kinase family interacting protein of 200 kDa; FOXO3, forkhead box O3; FUNDC, FUN14 domain-containing protein; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; LKB1, liver kinase B1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NIX, NIP3-like protein X; OPTN, optineurin; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PINK, PTEN-induced kinase; PRKN, Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; SIRT, sirtuin; SP, spermidine; TFEB, transcription factor EB; ULK1, unc-51-like kinase 1; UROA, urolithin A; VPS, vacuolar protein sorting.

The first step of autophagy is initiation, which depends on AMPK activation. AMK activates the ULK complex (ULK1/2, FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200) and autophagy related genes Atg101 and Atg3). AMPK is activated by nutrient deficiency and starvation. Other factors that can induce AMPK include SIRT1, which induces liver kinase B1 (LBK1), in turn activating AMPK. It is necessary to mention that SIRT1 influences more than one step of autophagy.

Urolithin A can induce autophagy as it is a positive regulator of the activity of AMPK, ULK1/2 and SIRT1(Reference Wang, Long and Hou28–Reference Lin, Zhuge and Zheng30). Similarly to UroA, spermidine supports the activity of AMPK and SIRT1. Both substances are recognised as inducers of autophagy(Reference Hofer, Daskalaki and Bergmann6, Reference Kriebs31).

The second step, nucleation, is more complex, involving the Atg9 system and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) complex. The PI3K complex consists of BECN1, autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1 (AMBRA1), VPS34 and VPS15 (components of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases), and Atg14L. Atg9 vesicles are produced by the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, and their production is regulated by AMPK, whose activity, as we know, is enhanced by UroA and spermidine(Reference Holzer, Martens and Tulli32).

Urolithin A also increases the expression and activity of BECN1, which also plays an important role in mitophagy. Spermidine also influences the amount of BECN1. This is because of its ability to target caspase 3, which reduces BECN1 levels. Caspase 3 cleaves BECN1, and inhibition of caspase 3 activity leads to an increase in BECN1 levels(Reference Wang, Long and Hou28, Reference Yang, Chen and Zhang33).

The third step of autophagy is elongation and expansion. Key roles in these processes are played by the LC3, Atg8 and Atg12 conjugation system. We first focused on the genetic and epigenetic aspects of the expression of the molecules mentioned.

LC3 expression depends, among others, on the activity of SIRT1, transcription factor EB (TFEB), histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and p300 HAT (EP300). SIRT1 is a deacetylase that epigenetically influences the expression of a wide variety of genes, including the gene for LC3. HAT and EP300 are acetyltransferases that prevent deacetylation and gene activation. TFEB acts as a transcription factor that regulates LC3 expression, and its function can be blocked by mTOR and protein kinase B (Akt). It is worth mentioning that the production of TFEB, as well as Atg3, is enhanced by eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 (eIF5A), which increases the translation of mRNA for these substances on ribosomes(Reference Lubas, Harder and Kumsta34, Reference Prasher, Sharma and Singh35).

Both UroA and spermidine increase the activity of SIRT1, and thus the expression and function of LC3, while inhibiting mTOR activity. Spermidine also blocks Akt activity, while UroA inhibits PI3K activity, which can activate Akt(Reference Niu, Jiang and Guo36–Reference Hofer, Simon and Bergmann39).

Spermidine supports the activity of eIF5A and thus enhances the synthesis of TFEB and Atg3. Spermidine reduces EP300 and HAT levels, which results in an increase in the production of LC3, Atg7, Atg11 and Atg15. Atg3 and Atg7 are important in the processing of pro-ILC3, which must be transformed into the active product(Reference Hofer, Daskalaki and Bergmann6, Reference Zhou, Pang and Tripathi40–Reference Kojić, Spremo and Đorđievski42).

To form definitive autophagosomes, the p62 protein is crucial. It is a sequestosome that delivers cargo into developing autophagosomes and thus reflects autophagic flux. p62 is degraded through autophagic processes, along with the cargo it delivers to the autophagosome. p62 is important for the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, which leads to the formation of autophagolysosomes(Reference Liu, Ye and Huang43). p62 is also regulated by UroA and spermidine, which improves lysosome function(Reference Jiménez-Loygorri, Viedma-Poyatos and Gómez-Sintes44–Reference de Wet, Du Toit and Loos46).

Atg5, whose activity is enhanced by UroA, plays a role in the final step of autophagy, specifically in the fusion of the autophagosome and the lysosome. Thus, UroA is also involved in the final step of autophagy(Reference Hou, Chu and Park47).

Mitophagy is closely related to autophagy; an autophagosome must be formed, enclosing the mitochondria, which then fuses with the lysosome. Mitophagy is induced when mitochondrial stress occurs, including mitochondrial damage, ROS production, depolarisation or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations. Factors involved in induction and progression of autophagy, especially AMPK, TFEB, LC3 and BECN1, play crucial roles in mitophagy(Reference Wang, Chen and Li48, Reference Zheng, Wang and Zhou49).

As we mentioned previously, UroA and spermidine enhance AMPK activity. AMPK is involved in the recruitment of UKL1, sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) and Atg16L (Atg16, Atg5, Atg12). Atg16L binds to LC3 on the membrane of the developing autophagosome. Urolithin A also increases the activity of SIRT3, which mobilises forkhead box O3 (FOXO3), responsible for the expression of PINK. PINK activity is also enhanced by UroA and spermidine. The interaction between PRKN and PINK is modulated by TFEB(Reference Faitg, D’Amico and Rinsch50–Reference Di, Xue and Li52).

There are two main pathways driving mitophagy: PINK/PRKN-dependent and PINK/PRKN-non-dependent, both of which are regulated by UroA and spermidine. In the PINK/PARKIN-dependent pathway, PRKN activates PINK, leading to the ubiquitination of membrane proteins on the mitochondrial membrane. These proteins recruit the adaptor proteins optineurin (OPNT) and calcium binding and coiled-coil domain (CALCOCO), etc., which subsequently bind to LC3(Reference Narendra and Youle53, Reference Padman, Nguyen and Uoselis54).

The activity of PRKN is increased by UroA, ULK1 and BECN1, all of which are induced by UroA and spermidine. BECN1 is blocked by B-cell lymphoma 2, apoptosis regulator (BCL2), which, in turn, is inhibited by PRKN. Urolithin A also stabilises the interaction between PRKN and PINK(Reference Fairley, Lejri and Grimm51, Reference Jayatunga, Hone and Khaira55, Reference Jang, Hong and Mo56).

The PINK/PARKIN non-dependent pathway consists of membrane receptors that can bind to LC3. These include Nip3-like protein X (NIX), BCL2 interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) and FUN14 domain-containing protein (FUNDC). Urolithin A regulates the activity of NIX and BNIP3(Reference Andreux, Blanco-Bose and Ryu14, Reference Il Cho, Jo and Song57).

The fusion of the autophagosome or automitophagosome is regulated by tectonin beta-propeller repeat containing 1 (TECRP1), which is located in the lysosome, and Atg5. The efficacy of degradation is mediated by lysosomal function, which can be supported by UroA(Reference Hou, Chu and Park47).

In vivo studies on urolithin A and spermidine

Even though both UroA and spermidine can affect autophagy and mitophagy, in vivo studies with UroA predominantly focus on mitophagy, while those with spermidine focus more on autophagy.

Urolithin A: in vivo studies

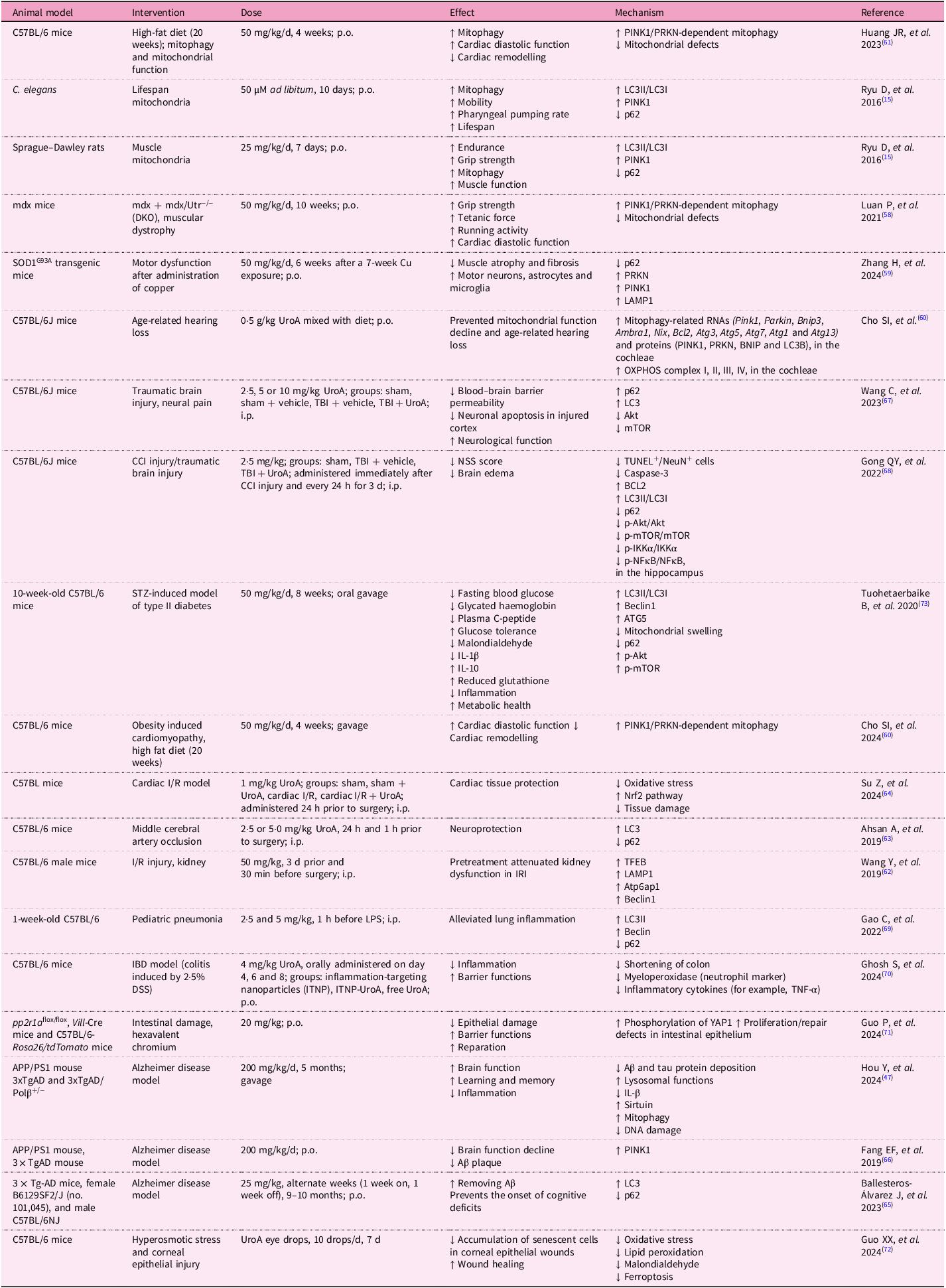

Urolithin A has emerged as a compound with extensive potential for improving health across multiple biological systems. Numerous in vivo studies have demonstrated its remarkable efficacy in enhancing mitochondrial function, promoting muscle health and potentially extending longevity (Table 1).

Table 1. In vivo studies on urolithin A

One of the most prominent studies conducted on C. elegans showed that Uro A can significantly prolong lifespan by inducing mitophagy. The study revealed that treated C. elegans exhibited enhanced mitochondrial clearance and reduced levels of oxidative stress, both of which contributed to the observed lifespan extension(Reference Ryu, Mouchiroud and Andreux15). Similar results have been observed in rodent models, where UroA supplementation led to improvements in muscle function and endurance. In a study involving aged mice, UroA enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and increased muscle strength, effectively reversing some of the age-related declines in muscle performance(Reference Ryu, Mouchiroud and Andreux15). Activation of the SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway was identified as a critical factor in this process, supporting the hypothesis that UroA’s effects on mitophagy play a key role in its ability to improve muscle health(Reference Andreux, Blanco-Bose and Ryu14).

Urolithin A has also been used in models of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. C. elegans and mice were used in the experiments. In both models, UroA supplementation led to restoration of impaired mitophagy, reduced muscular atrophy and fibrosis, and improved muscle function(Reference Luan, D’Amico and Andreux58, Reference Zhang, Gao and Yang59). The induction of mitophagy may also serve as a prevention against age-related hearing loss, as Cho et al. described. Their study showed that treatment with UroA improves mitochondrial DNA integrity and ATP production in the inner ear and auditory cortex. The health of mitochondria was preserved through the maintenance of mitophagy(Reference Cho, Jo and Jang60).

Studies show that UroA promotes not only muscle health but also cardiovascular health. It can mitigate the effects of an unhealthy lifestyle on the myocardium and also reduce the effects of blood vessel damage leading to ischaemia on the affected tissues. One study indicated that UroA may help with obesity-induced cardiomyopathy. The authors of the study found that decreased autophagy and mitophagy in this condition can be fully restored with UroA administration, resulting in improved cardiac function(Reference Huang, Zhang and Chen61).

Proper functioning of the heart and other organs requires a solid vascular supply. Studies demonstrate that UroA may play a critical protective role in cases of ischaemia–reperfusion injury. Ischaemic vascular diseases are very common, and even if reperfusion occurs, tissue damage can be significant, with severely impaired function in affected tissues. The most serious conditions tend to occur after blood vessel occlusion in the brain or heart. In mouse models of cerebral or renal artery occlusion, pretreatment with UroA appeared to mitigate the effects of ischaemia, reducing the extent of tissue damage and restoring impaired autophagy(Reference Wang, Huang and Jin62, Reference Ahsan, Zheng and Wu63). Su et al. showed that the positive effect of UroA on ischaemia–reperfusion injury is mediated by attenuation of oxidative stress and ferroptosis, as well as Nrf2 pathway activation(Reference Su, Li and Ding64).

With the ageing of the population, the incidence of not only cardiovascular but also neurodegenerative diseases is increasing. Supplementation with UroA in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease leads to the removal of amyloid β and a slowing of decline in brain function through restoration of autophagy and mitophagy(Reference Ballesteros-Álvarez, Nguyen and Sivapatham65, Reference Fang, Hou and Palikaras66). The positive effect of UroA on the central nervous system is also seen in brain injuries. Two studies focused on traumatic brain injury showed that supplementation with UroA in mice alleviates its consequences (neurological dysfunctions, neural pain, brain oedema and disruption of blood–brain barrier functions) by restoring autophagy. It increases LC3 and decreases the activity of Akt and mTOR(Reference Wang, Wang and Xue67, Reference Gong, Cai and Jing68).

However, the positive effect of UroA on health does not end there, it can also aid in managing infections, inflammation and metabolic diseases. In a mouse model of paediatric pneumonia, supplementation with Uro A resulted in a decrease in lung inflammation and damage(Reference Cao, Wan and Wan69).

The effect of UroA on the immune system and inflammation was evaluated in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Researchers developed nanoparticles loaded with UroA, and these formulations alleviated inflammation(Reference Ghosh, Singh and Goap70). Guo et al. also confirmed that UroA has the potential to limit inflammation and ameliorate intestinal damage caused by hexavalent chromium. It significantly improved tissue repair and intestinal barrier function(Reference Guo, Yang and Zhong71).

The regenerative effect of UroA was also described in a study by Guo et al., which focused on healing damaged corneal epithelium. They found that eyedrops containing UroA accelerated the healing of corneal epithelium, reduced cell senescence and inhibited ferroptosis(Reference Guo, Chang and Pu72).

The impact of UroA on metabolic health was verified in a mouse model of streptozotocin-induced type II diabetes. Mice with this condition were supplemented with UroA, which led to decreased fasting blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin levels, plasma C-peptide, malondialdehyde (MDA) and interleukin-1β levels. It also increased reduced glutathione (GSH), interleukin-10 and glucose tolerance(Reference Cao, Wan and Wan69, Reference Tuohetaerbaike, Zhang and Tian73).

Spermidine: in vivo studies

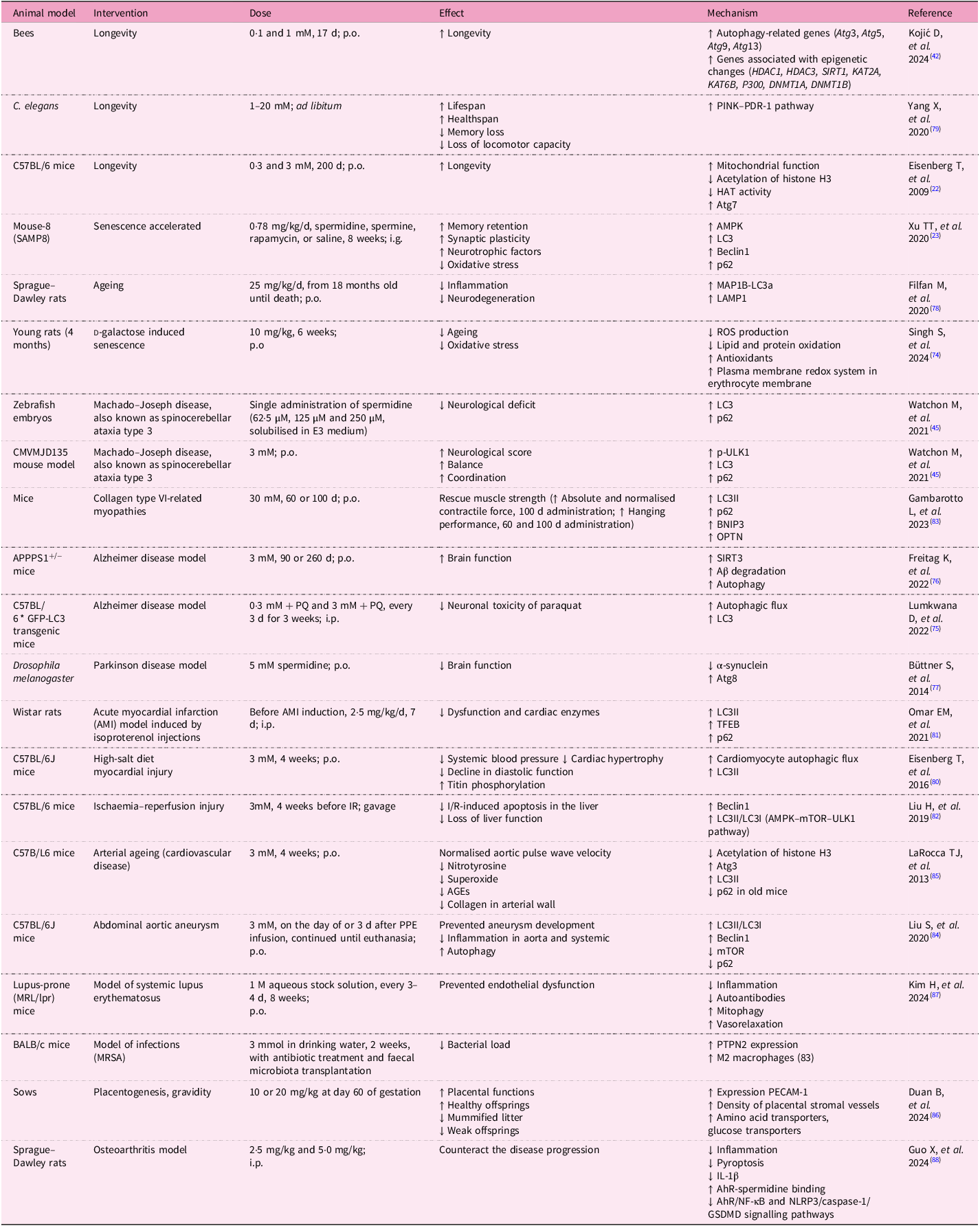

Spermidine has a wide range of effects that have been tested in animal models (Table 2).

Table 2. In vivo studies on spermidine

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AGEs, advanced glycation end-products; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; Akt, protein kinase B; AMBRA1, activating molecule in Beclin1-regulated autophagy protein 1; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; Atg, autophagy-related genes; Atp6ap1, ATPase H + transporting accessory protein 1; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BNIP3, BCL2 interacting protein 3; CCI, controlled cortical impact; DNMT1, DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1; DSS, dextran sodium sulphate; GSDMD, gasdermin D; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IKKα, IκB kinase α; IL, interleukin; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; IRI, ischemia-reperfusion injury; ITNP, inflammation-targeting nanoparticles; KAT, lysine acetyltransferase; LAMP1, lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAP1B, microtubule-associated protein 1B; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NeuN, neuronal nuclei; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NIX, NIP3-like protein X; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; NSS, neurological severity score; OPTN, optineurin; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PRKN, Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; PDR-1, Parkin homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans; PECAM-1, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1; PINK1, PTEN induced kinase 1; p.o., per os; PQ, paraquat; PTPN2, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SIRT, sirtuin; STZ, streptozotocin; TBI, traumatic brain injury; TFEB, transcription factor EB; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labelling; ULK1, unc-51-like kinase 1; UroA, urolithin A; YAP1, Yes-associated protein.

In vivo studies on spermidine have provided compelling evidence of its role in promoting longevity and improving cognitive function. Lifespan extension has been observed in various animal models, including yeast, flies and rodents. A study on bees showed that spermidine supplementation supports longevity by improving autophagy, which depends on the epigenetic changes that are induced by the presence of spermidine. It enhances the expression of genes coding for Atg proteins(Reference Kojić, Spremo and Đorđievski42).

In a study on C57BL/6J mice, lifelong supplementation with spermidine led to a significant extension of lifespan, with improvements in mitochondrial function, reduced oxidative stress and enhanced autophagic activity(Reference Eisenberg, Knauer and Schauer22).

The aforementioned oxidative stress is a key factor that accelerates biological ageing. In a study using a rat model of d-galactose-induced senescence and ageing, the authors focused on cellular redox status and ionic homeostasis. Spermidine consumption prevented the onset of age-induced increase in production of ROS, thus reducing lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation. Spermidine also increased antioxidant levels, which were associated with reduced cell damage and inflammation, and delayed biological ageing(Reference Singh, Verma and Garg74). Of note, these results are consistent across multiple species, highlighting the conserved nature of spermidine’s effects on cellular health and ageing.

Oxidative stress, inflammation and accelerated ageing are accompanied by damage to the central nervous system, including neurodegeneration. Spermidine’s ability to protect against neurodegeneration has been particularly well-documented. In a study involving SAMP8 mice, a model for ageing and cognitive decline, spermidine supplementation resulted in significant improvements in memory function and reduced neuroinflammation. Spermidine enhanced autophagic flux in neurons, facilitating the clearance of damaged proteins and improving mitochondrial function. These findings were accompanied by an increase in neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF), which are critical for synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival(Reference Xu, Li and Dai23).

The protection of the nervous system was also confirmed in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as in mouse and zebrafish models of ataxia (Machado–Joseph disease). Supplementation with spermidine preserved brain functions, increased amyloid β degradation and enhanced coordination and stability in mice. These improvements were dependent on the restoration of autophagy, confirmed by detection of increased levels of LC3 and components that enhance lysophagy(Reference Watchon, Wright and Ahel45, Reference Lumkwana, Peddie and Kriel75, Reference Freitag, Sterczyk and Wendlinger76).

Another highly prevalent neurodegenerative disease among elderly people is Parkinson disease (PD). Spermidine has also been utilised in PD models. In a Drosophila melanogaster model of PD, spermidine reduced brain function decline and decreased accumulated α-synuclein by restoring autophagy(Reference Büttner, Broeskamp and Sommer77).

Some studies confirmed that in neurodegenerative diseases, spermidine also activates mitophagy by enhancing PINK expression, which prolongs lifespan, improves health span, protects against memory loss and increases locomotor activity(Reference Filfan, Olaru and Udristoiu78, Reference Yang, Zhang and Dai79).

Cardiovascular benefits have also been observed in vivo, particularly in models of age-related cardiac decline. A study involving aged mice found that spermidine supplementation reduced cardiac hypertrophy and improved left ventricular function. This was attributed to spermidine’s ability to activate mitophagy and autophagy, helping maintain mitochondrial quality and preventing the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in heart tissue(Reference Eisenberg, Abdellatif and Schroeder80).

In the Wistar rat model of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), supplementation before AMI induction reduced cardiac dysfunction and cardiomyocyte damage. Spermidine increased levels of LC3-II, TFEP and p62, which are important components of autophagy(Reference Omar, Omar and Shoela81).

In the context of myocardial infarction, it is important to mention that spermidine administration before liver ischaemia activates autophagy, reduces liver damage and decreases the number of apoptotic cells, suggesting a protective effect comparable to that observed in myocardial infarction(Reference Liu, Dong and Song82). Similarly to heart muscle, the improvement in its functionality despite AMI suggests that spermidine has a similar effect on skeletal muscle. Spermidine was used in a mouse model of collagen-type-VI-related myopathies. Importantly, spermidine induces both autophagy and mitophagy (LC3-II, p62, BNIP3 and OPTN) and restores muscle strength(Reference Gambarotto, Metti and Corpetti83).

Spermidine protects the cardiovascular system, even when mice are exposed to a high-salt diet. Such diet leads to increased blood pressure and damage to blood vessels and the myocardium. These negative effects can be alleviated by spermidine. It reduces blood pressure and myocardial hypertrophy by increasing autophagic flux(Reference Eisenberg, Abdellatif and Schroeder80). Spermidine supplementation may also suppress aortic aneurysm formation and inflammation in a mouse model. In addition, it may reverse arterial ageing(Reference Liu, Huang and Liu84, Reference LaRocca, Gioscia-Ryan and Hearon85). The effect of spermidine on the vascular system was further confirmed by Duan et al., who supplemented sows with spermidine during gestation, which improved placental quality and enhanced angiogenesis, and thus increased the number of healthy offsprings(Reference Duan, Ran and Wu86). Systemic inflammatory diseases are accompanied by endothelial damage. In a study using a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus, endothelial dysfunction was confirmed. This damage was ameliorated by spermidine supplementation, which reduced inflammation, decreased antibody production and increased vascular relaxation and mitophagy(Reference Kim and Massett87).

Joints are very often affected by inflammation and damage; this can result from autoimmune inflammation or degenerative processes caused by joint abrasion. In a study of induced osteoarthritis in rats, the authors demonstrated that spermidine supplementation reduced pyroptosis and proinflammatory cytokine production and limited pathological processes in the joints(Reference Guo, Feng and Yang88).

The anti-inflammatory effect of spermidine was also demonstrated in a mouse model of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. In mice infected with MRSA, which is an important and dangerous human pathogen, treatment with spermidine reduced the MRSA burden in the bloodstream and limited systemic inflammation by polarising macrophages toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. Thus, the results of the studies show that spermidine has the potential to prolong life, protecting both the nervous and cardiovascular systems(Reference Li, Tian and Guo89).

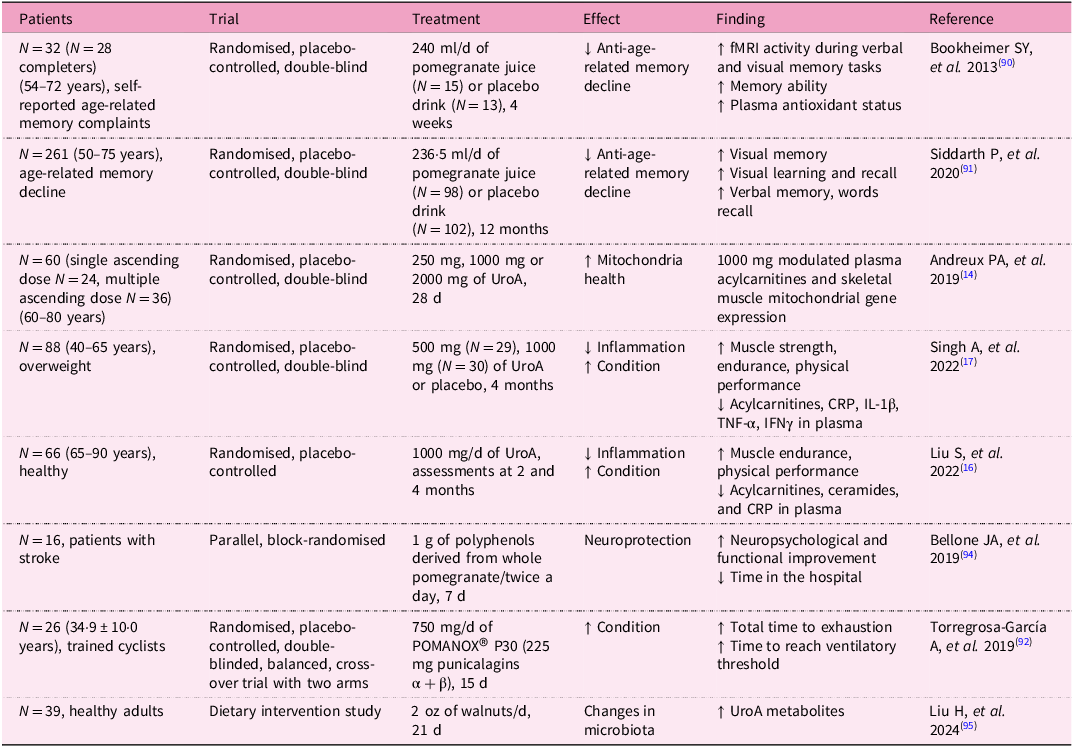

Clinical studies on urolithin A and spermidine

Urolithin A: clinical studies

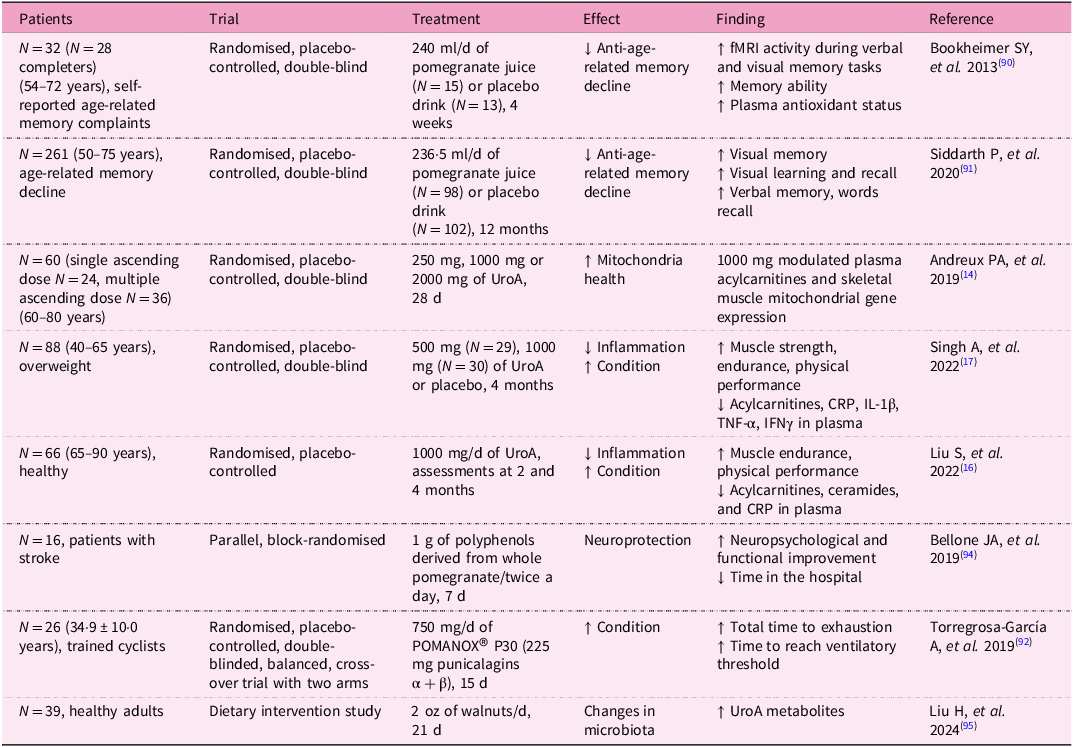

Owing to the promising results of in vivo studies with UroA, several clinical studies with volunteers have also been conducted (Table 3).

Table 3. Clinical studies on urolithin A

Clinical trials on UroA have demonstrated its potential in improving muscle function and mitochondrial health, particularly in older adults. One notable study was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the effects of UroA supplementation in elderly individuals. Participants were given daily doses of UroA over a period of 4 months. The results showed significant improvements in ATP production, muscle strength, 6-min walk distance and endurance in those who received the supplement compared with the placebo group. In addition, the study observed increased mitochondrial activity in muscle biopsies, confirming UroA’s role in enhancing mitochondrial function(Reference Singh, D’Amico and Andreux17). Indeed, the increase in muscle strength and endurance is closely linked to mitochondrial function. As was already mentioned, homeostasis is crucial, including the biogenesis of new mitochondria and the removal of damaged and dysfunctional ones(Reference Singh, D’Amico and Andreux17).

Studies show that in people over 50 years, supplementation with UroA in the form of pomegranate juice for at least 1 month led to improvements in brain function, as well as in visual and verbal memory(Reference Bookheimer, Renner and Ekstrom90, Reference Siddarth, Li and Miller91). Similarly, consumption of pomegranate juice by trained cyclists resulted in increased time to exhaustion and time to reach the ventilatory threshold(Reference Torregrosa-García, Ávila-Gandía and Luque-Rubia92). Considering the fact that pomegranate juice is an important source of UroA, such beneficial effects can be indirectly ascribed to this compound.

Zhao et al. conducted an 8-week study on male athletes undergoing resistance training to evaluate the effect of UroA on muscle endurance, strength, inflammation, oxidative stress and protein metabolism. Participants consumed 1 g of UroA daily. The UroA supplementation increased voluntary isometric contraction and repetitions to failure performance. The levels of CRP and superoxide dismutase were lower compared with the control group. Urolithin A improved physical condition and reduced oxidative stress and inflammation(Reference Zhao, Zhu and Yun93).

In another clinical trial, UroA supplementation was tested for its impact on mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolic health. Participants, including both healthy middle-aged and older adults, received UroA supplements for 28 d. The study reported an increase in the expression of genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis, as well as improvements in markers of mitochondrial function and reduction in fatigue. These findings suggest that UroA may have broad applications for improving energy metabolism, especially in populations experiencing age-related declines in mitochondrial efficiency(Reference Andreux, Blanco-Bose and Ryu14).

It can be summarised that UroA’s positive effects are because of its ability to inhibit inflammation and oxidative stress, while inducing and enhancing mitophagy and autophagy. In vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that UroA is able to protect nerve cells and alleviate neurodegenerative processes such as those seen in Alzheimer’s disease, where autophagy and mitophagy play a significant role in the pathogenesis of such neurodegenerative diseases. It is therefore possible to assume that in clinical trials in which neurodegenerative diseases were alleviated, mitophagy and autophagy were also enhanced.

It has been also reported that polyphenols, including UroA, can also protect the brain in the event of a cerebral infarction, shorten hospital stay after a stroke and improve neuropsychiatric and motor function(Reference Bellone, Murray and Jorge94). Finally, the effect of UroA on human health is also mediated by its effect on the gut microbiota. The influence of the gut microbiota on UroA levels has been described, as it is responsible for producing UroA from the polyphenol ellagic acid. However, the consumption of certain foods, in this case walnuts, has also been shown to influence the composition of the gut microbiome. In a study with healthy volunteers, the gut microbiome composition differed before and 21 d after walnut consumption. Alpha and beta diversity were significantly altered. Roseburia, Rothia, Parasutterella, Lachnospiraceae UCG-004, Butyricicoccus, Bilophila, Eubacterium eligens, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, Gordonibacter, Paraprevotella, Lachnospira, Ruminococcus torques and Sutterella were identified as the thirteen genera most enriched following daily walnut intake(Reference Liu, Birk and Provatas95).

Importantly, safety and tolerability studies have been conducted to ensure that UroA is safe for human consumption. One study assessed the safety of UroA in humans, finding no adverse effects at dosages ranging from 250 mg to 1000 mg per day administered over a 4-week period. Participants exhibited no significant changes in vital signs, blood chemistry or electrocardiograms, confirming the compound’s safety profile for long-term use(Reference Andreux, Blanco-Bose and Ryu14).

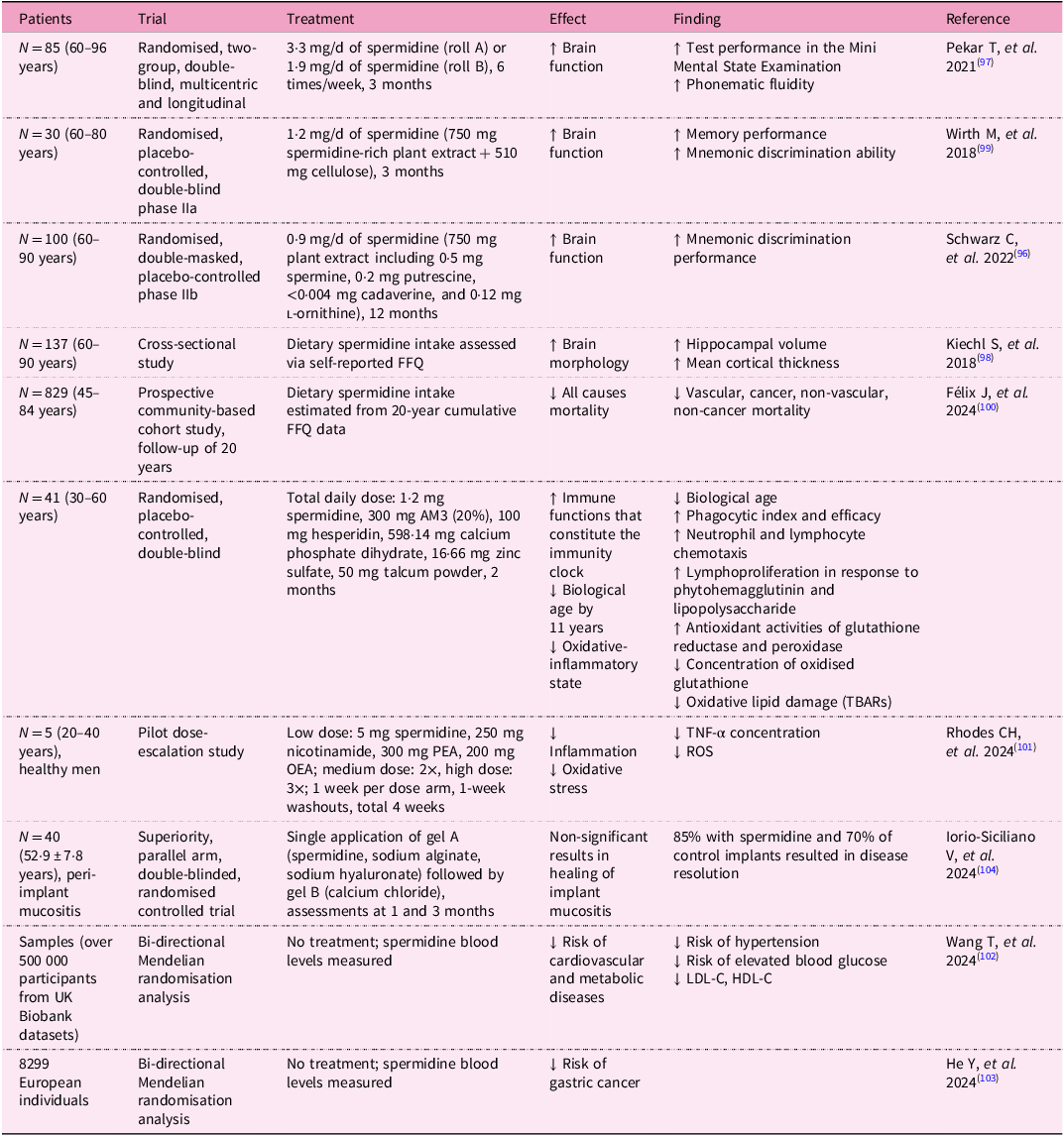

Spermidine: clinical studies

Spermidine has also been studied extensively in human populations, with a focus on its ability to improve cognitive function, promote longevity and reduce the risk of age-related diseases (Table 4). One pivotal randomised, placebo-controlled trial tested the effects of spermidine supplementation in older adults with subjective cognitive decline. Over a period of 12 months, participants received daily doses of a spermidine-rich plant extract. The study reported significant improvements in memory performance and cognitive function, particularly in those with mild cognitive impairment. These findings suggest that spermidine supplementation may help slow cognitive decline and enhance brain function in ageing individuals(Reference Schwarz, Benson and Horn96). Another study found that spermidine supplementation improves brain functions in elderly people aged 60–96 years. Participants showed improvements in standardised tests of mental function, including Mini Mental State Examination and phonematic fluidity(Reference Pekar, Bruckner and Pauschenwein-Frantsich97). It has also been shown that a diet rich in spermidine can alter brain morphology in the elderly. Interestingly, subjects with higher dietary spermidine intake had greater hippocampal volume, mean cortical thickness and cortical thickness in Alzheimer’s-disease-vulnerable brain regions(Reference Schwarz, Horn and Benson19). Another large-scale epidemiological study examined the relationship between dietary spermidine intake and all-cause mortality. This study followed a cohort of more than 800 participants over a 20-year period and found that individuals with higher dietary spermidine intake had a significantly lower risk of death from all causes, including cardiovascular disease and cancer. These findings align with spermidine’s role in promoting autophagy, reducing oxidative stress and enhancing cellular longevity(Reference Kiechl, Pechlaner and Willeit98).

Table 4. Clinical studies on spermidine

Abbreviations: AM3, Immunoferon®; CRP, C-reactive protein; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IFNγ, interferon gamma; IL-1β, interleukin 1 beta; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OEA, oleoylethanolamide; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TBARs, thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor alpha; UroA, urolithin A.

In terms of metabolic health, clinical trials have shown that spermidine supplementation can improve glucose metabolism and reduce insulin resistance in obese individuals. In one study, participants who consumed a spermidine-rich diet for 3 months exhibited improved insulin sensitivity and lower fasting glucose levels, suggesting spermidine’s potential as a therapeutic agent for managing metabolic disorders(Reference Wirth, Benson and Schwarz99). The anti-ageing, immune-stimulating and antioxidation properties of spermidine were tested in a study by Felix et al., who supplemented participants with capsules containing AM3, spermidine and hesperidin. The supplementation reduced biological age and oxidative stress while increasing immune system function(Reference Félix, Díaz-Del Cerro and Baca100). Finally, the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and cardioprotective effects of spermidine were evaluated and confirmed in a study by Rhodes et al. (Reference Rhodes, Hong and Tang101).

There was also a cardioprotective effect of spermidine as demonstrated by Wang et al. In this study, they determined the levels of spermidine in the blood of participants. They found that higher spermidine levels are associated with a lower risk of hypertension, lower levels of blood glucose and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). These data suggest that increased spermidine intake can also improve cardiovascular and metabolic health(Reference Wang, Li and Zeng102).

A bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study was conducted by He et al., who, based on a genome-wide associated study of 8299 European individuals, found that the spermidine to N(1)+N(8)-acetylspermidine ratio negatively correlated with gastric cancer(Reference He, Cai and Hu103). A study performed by Iorio-Siciliano et al. used a product with spermidine to treat peri-implant mucositis. Spermidine was incorporated into a gel that was applied locally to the gums. Although no significant differences were initially observed between the groups after 3 months, the use of the gel resulted in an 85% disease resolution rate, compared with a 70% resolution rate without adjunctive application of the gel(Reference Iorio-Siciliano, Marasca and Mauriello104).

Finally, spermidine’s safety profile has been extensively tested. In a 12-month randomised clinical trial, spermidine supplementation was found to be safe, with no significant adverse effects reported. Participants receiving up to 1·2 mg of spermidine daily exhibited no significant changes in blood parameters or organ function, confirming the safety of long-term supplementation(Reference Bookheimer, Renner and Ekstrom90). The safety and tolerability of spermidine were also tested by Keohane et al., who supplemented older men with a dose as high as 40 mg/d for 7d and 28 d. The dose was well-tolerated, and no adverse events were reported. Spermidine did not alter lipid levels, blood chemistry or haematological parameters(Reference Keohane, Everett and Pereira105).

Conclusions

Urolithin A and spermidine are two promising compounds that have gained significant attention for their potential to enhance cellular health, promote longevity and mitigate the effects of ageing through the activation of autophagic and mitophagic pathways.

Urolithin A stimulates mitophagy, a process that selectively clears damaged mitochondria. Its ability to target mitochondrial dysfunction makes it particularly effective in improving muscle function and energy metabolism, as demonstrated in both preclinical and clinical studies. Moreover, UroA has shown significant potential in addressing age-related muscle decline, metabolic disorders and enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis, particularly in older adults. Its safety profile is well-established, making it a viable option for long-term supplementation, particularly for individuals seeking to improve mitochondrial health.

By inducing autophagy, spermidine supports the degradation and recycling of a wider range of cellular components, including damaged proteins and organelles. This comprehensive impact on cellular homeostasis enables spermidine to provide additional benefits, including neuroprotection, cardiovascular health and cognitive enhancement. Spermidine’s ability to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, and support cognitive function in ageing individuals, makes it a versatile anti-ageing supplement with far-reaching effects beyond muscle health.

When comparing the two candidates on the basis of available clinical studies, UroA is more focused on mitochondrial health and may be particularly beneficial for individuals facing age-related muscle decline and metabolic dysfunctions. Spermidine, in contrast, offers broader systemic benefits, particularly in terms of neuroprotection and cognitive health, while also contributing to overall longevity through its modulation of autophagy.

On the basis of the current evidence, spermidine may be the superior supplement for individuals seeking comprehensive anti-ageing benefits that extend beyond mitochondrial health, particularly for those concerned with cognitive decline and cardiovascular health. However, UroA may be more appropriate for those specifically targeting muscle endurance, metabolic health and mitochondrial function.

In conclusion, there are no reports that highlight any specific toxicity of either compound. Only non-specific side effects such as allergies, overuse and potential interactions with drugs which target mitochondrial or metabolic function should be considered. Thus, both compounds are safe and hold great potential as dietary supplements, but the choice between UroA and spermidine ultimately depends on the individual’s specific health goals. For a more targeted intervention aimed at mitochondrial function, UroA stands out, while for broader anti-ageing effects, including cognitive and cardiovascular health, spermidine is the more versatile option.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the use of pictures from Servier Medical Art, by Servier (http://smart.servier.com).

Financial support

The review was supported by The Biomedical Indicators for Personalized Medicine project (BIPOLE), project ID CZ.02.01.01/00/23_021/0008439, co-funded by the European Union. The review was supported by Charles University, Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove, the Czech Republic, by project SVV-2025-260776.

Competing interests

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest.

Authorship

PB was responsible for conceptualisation, conducted the literature search and wrote the original draft. DH, OS, TP and MH assisted in the literature search. DH, OS, TP, ZF and MH performed manuscript editing. LB and OS provided funding acquisition.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT v1 in order to rewrite parts of the manuscript. After using this service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.