Some developed countries( Reference Ward, Gaboury and Ladhani 1 – Reference Robinson, Hogler and Craig 4 ) have reported a resurgence of vitamin D deficiency and rickets in children and infants, in spite of national recommendations for vitamin D supplementation in infancy. The content of vitamin D in breast milk is very low( Reference Hollis, Roos and Draper 5 , Reference Kunz, Niesen and von Lilienfeld-Toal 6 ) and thus exclusively breast-fed children have greater risk of developing vitamin D deficiency than children receiving infant formula( Reference Kreiter, Schwartz and Kirkman 7 ). Adequacy of prenatal vitamin D transfer depends on maternal vitamin D stores, which have been shown to be inadequate in many countries( Reference Weiler, Fitzpatrick-Wong and Veitch 8 ). Natural food sources of vitamin D are few, the most common being egg yolk and fish( Reference Cavalier, Delanaye and Chapelle 9 ). Vitamin D fortification of foods has become common in various countries. Typical fortified food items are milk, margarine, juices and breakfast cereals( Reference Calvo, Whiting and Barton 10 ). Also, infant formulas are fortified with vitamin D. Recommendations given for the use of vitamin D supplements during infancy are currently quite uniform in different countries( Reference Hochberg, Bereket and Davenport 11 – 13 ), while compliance with these recommendations varies widely( Reference Perrine, Sharma and Jefferds 14 – Reference Räsänen, Kronberg-Kippilä and Ahonen 16 ). There is a lack of internationally comparable data on vitamin D supplement use.

The Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk (TRIGR; IDDM = insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) is an international, randomized, double-blinded study testing the hypothesis whether weaning to an extensively hydrolysed infant formula reduces the risk of developing type 1 diabetes (T1D) in children with increased genetic disease susceptibility( 17 ). The TRIGR prospective nutrition questionnaires provide a unique opportunity to compare information on vitamin D supplement use in different countries. Through that study we aimed to determine how vitamin D supplements were used in infancy in the TRIGR countries and to assess adherence with national recommendations. Further, we assessed how infant feeding, sociodemographic and perinatal factors, region and maternal T1D were related to the use of vitamin D supplements.

Experimental methods

Study population

Newborn infants with a biological first-degree relative affected by T1D as defined by the WHO were invited into the study. The families were recruited when the mother was in late pregnancy (gestational age 35 weeks or more) or immediately after the delivery. Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping was performed from cord blood or from a blood sample obtained before the age of 8 d. Infants with increased HLA-conferred susceptibility to T1D were eligible to participate in the study. Altogether 2159 infants from twelve countries in Europe and from the USA, Canada and Australia, born between May 2002 and February 2007, were included in the TRIGR study. Of these, 1095 were born to women with diabetes and 1064 to unaffected women. The TRIGR countries have been divided into seven regions: Northern Europe (Finland and Sweden, n 521); Central Europe I (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Poland, n 317; i.e. transition economies); Central Europe II (Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland, n 184); Southern Europe (Italy and Spain, n 114); the USA (n 393); Canada (n 528); and Australia (n 102). The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical committee of each site approved the study and signed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the infant.

Exclusion criteria included multiple gestation, an older sibling already participating in TRIGR, recognizable severe illness, gestational age <35 weeks, age of the infant more than 7 d at randomization, or no HLA sample drawn before the age of 8 d. Breast-feeding was encouraged. Infants were randomized to receive either a regular cow's milk-based infant formula or an extensively hydrolysed infant formula (Nutramigen®; Mead Johnson, Evansville, IN, USA) upon weaning from breast milk in the first 6–8 months of life. If mother's own breast milk or banked breast milk was not available before randomization, these infants were given Nutramigen in order to avoid exposure to intact cow's milk proteins. Those infants who had received any infant formula other than Nutramigen prior to randomization were excluded. Finally, families having any other reasons (e.g. religious, cultural, unwillingness) to refuse feeding the infant with cow's milk-based products were excluded. Study formulas were enriched with vitamin D. The study did not interfere with the standard feeding practices of the infants other than the avoidance of non-study formulas and foods containing cow's milk or beef.

Dietary interviews

Information on infant feeding was acquired from the family through standardized dietary interviews. Data on vitamin D supplement use were collected with a validated( Reference Vahatalo, Barlund and Hannila 18 ) FFQ at several time points during the first year of life. The content of vitamin D in the supplements was not inquired and therefore the amount of supplemental vitamin D could not be calculated. In the present study, vitamin D supplementation refers to the use of vitamin D as supplements and does not include the intake of vitamin D from infant formulas or other foods. Mothers were interviewed by a study nurse or dietitian by telephone when the child was 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months, 4 months and 5 months old, and at study centre visits at the ages of 3 and 6 months.

Of randomized families, 99·6 % (varied between 98·3 and 100 % in the different regions) participated in the first interview (at the age of 2 weeks) and 98·8 % (varied between 98·1 and 100 % in the different regions) of them answered the question concerning vitamin D supplement use. Of randomized families, 98·8 % (varied between 95·6 and 100 % in the different regions) participated in the study visit at the age of 6 months and 95·0 % (varied between 92·4 and 98·3 % in the different regions) of them answered the vitamin D supplement question.

Statistics

The use of vitamin D supplements was divided into two categories: (i) any use and (ii) daily use. The daily use was defined as 4–7 times/week. The use of vitamin D supplements was recorded at each dietary interview. The associations of sociodemographic and perinatal factors with the use of vitamin D supplements at 6 months of age were analysed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. The results are shown as odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals. All statistical tests were two-sided, at a significance level of P < 0·05, and performed using the SAS statistical software package version 9·1.

Results

Vitamin D supplementation from 2 weeks to 6 months of age varied significantly by region (Table 1). Most of the infants who received vitamin D supplements were given them daily. From 2 weeks up to 6 months of age, more than 80 % of the infants received vitamin D supplements in Northern (Finland and Sweden) and Central Europe (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland), over 60 % in Southern Europe (Italy and Spain), and approximately 50 % in Canada. Less than 2 % of infants in the USA and Australia received vitamin D supplements between the age of 2 weeks and 6 months (Table 1).

Table 1 Use of vitamin D supplementation in different regions according to child age: TRIGR (Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk) study, 2002–2007

IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

†The following regions were included: Northern Europe (Finland and Sweden); Central Europe I (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Poland; transition economies); Central Europe II (Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland); Southern Europe (Italy and Spain); the USA; Canada; and Australia.

‡Use of vitamin D supplements in any frequency.

§Use of vitamin D supplements 4–7 times/week.

There were no significant differences in the vitamin D supplementation of infants between mothers with and without T1D (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). When vitamin D supplement use was examined in relation to exclusive breast-feeding, differences between those exclusively breast-fed up to at least 5 months and the others were notable only for Canada, with exclusively breast-fed infants receiving more supplementation than the other infants (Table 2).

Table 2 Use of vitamin D supplementation in different countries by exclusive breast-feeding status when the child was 5 months old: TRIGR (Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk) study, 2002–2007

IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

†The following regions were included: Northern Europe (Finland and Sweden); Central Europe I (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Poland; transition economies); Central Europe II (Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland); Southern Europe (Italy and Spain); the USA; Canada; and Australia.

Maternal T1D, caesarean section and living in Central Europe II, Southern Europe and Canada were associated with less frequent use of vitamin D supplements, whereas higher gestational age was associated with more frequent use of vitamin D supplements at the age of 6 months in univariate analysis (Table 3). When all the factors associated with the use of vitamin D supplementation at 6 months of age were considered simultaneously in a multivariate analysis, higher gestational age, older maternal age and longer maternal education were associated with more frequent use of vitamin D supplements (Table 3). Infants living in Central Europe II, Southern Europe and Canada were less likely to get vitamin D supplementation when compared with those living in Northern Europe. The USA and Australia were not included in the analysis as the use of vitamin D supplements in those regions was very low.

Table 3 Risk for the use of vitamin D supplements according to sociodemographic, perinatal and other background factors at 6 months of age: TRIGR (Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk) study, 2002–2007

IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

*P < 0·05.

†Adjusted for all the variables in the table.

‡The following regions were included: Northern Europe (Finland and Sweden); Central Europe I (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Poland; transition economies); Central Europe II (Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland); Southern Europe (Italy and Spain); and Canada. The USA and Australia were not included in the analysis as the use of vitamin D supplements in those regions was very low (Tables 1 and 2; online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

Discussion

In the TRIGR study, the use of vitamin D supplements during the first 6 months of life varied by region with more than 80 % of the infants living in Northern and Central Europe receiving supplementation, over 60 % in Southern Europe and only half in Canada. The use of vitamin D supplements was extremely rare in the USA and Australia, where very few infants received any supplementation during the first 6 months of life. Higher gestational age and maternal age and longer education were associated with more frequent use of vitamin D supplements. Maternal T1D was not associated with vitamin D supplement use. Considerable difference in supplementation by breast-feeding status was only seen in Canada, where exclusively breast-fed infants received more supplementation.

The present study provides valuable comparative information about vitamin D supplement use in infancy from fifteen countries on three continents. The information on vitamin D supplementation was acquired by an FFQ which was validated against two 48 h recall interviews( Reference Vahatalo, Barlund and Hannila 18 ). In the validation study, the agreement of the two methods for vitamin D supplementation was shown to be moderate.

Limitations of the present study are that we did not assess either the dosage of vitamin D supplementation nor vitamin D intake from food. Nor had we an opportunity to measure vitamin D from the peripheral circulation. We were not able to collect data regarding vitamin D supplement use after the age of 6 months. The generalizability of the findings is limited because the study subjects represent a select group of children as they have an increased HLA-conferred susceptibility to T1D as well as a family member affected by T1D. The use of vitamin D supplements may be more frequent in the present risk group since vitamin D intake has been associated with decreased risk of T1D( Reference Hypponen, Laara and Reunanen 19 ).

At the time of the dietary data collection in the TRIGR study (from 2002 to 2007), several of the countries involved in TRIGR had given dietary recommendations for vitamin D supplementation in infants: Sweden and Switzerland recommended a daily supplementation of 10 μg( 20 , Reference Spalinger, Schubiger and Baerlocher 21 ); Finland and Estonia from 5 to 10 μg depending on breast-feeding status or amount of infant formula consumed( Reference Hasunen, Kalavainen and Keinonen 22 , Reference Mägi 23 ); Germany 10 μg( 24 ); the Netherlands 5 μg( 25 ); and Canada 10 μg until the intake from other sources reached that level( 13 ). In the USA, vitamin D supplements were previously recommended only for those breast-fed infants not exposed to adequate sunlight and/or whose mothers were vitamin D-deficient( 26 ). From 2003 onwards, a daily supplementation of 5 μg was recommended in the USA unless a certain amount of fortified infant formula or milk was consumed( Reference Gartner and Greer 27 ), and in 2008, the recommended dosage for supplementation was doubled to 10 μg( Reference Wagner and Greer 28 ). Also Finland( 12 ), Estonia( 29 ) and the Netherlands( 25 ) have increased their recommendation for vitamin D supplementation to 10 μg, and Poland( 30 ), Italy( Reference Bartolozzi 31 ) and Spain( 32 ) have given a recommendation of 10 μg daily depending on breast-feeding status or amount of infant formula consumed. In the Czech Republic, the recommended dose for vitamin D supplementation is currently 12·5 μg/d( Reference Frühauf 33 ) and in Hungary 10 μg( 34 ). In Australia, vitamin D supplements are recommended only for specific infant groups with very little sun exposure due to dark skin and/or children with veiled mothers( 35 ). With the exception of Australia, the overall recommended amounts of supplementation are now very similar during the first year of life in these countries and also the differences in the recommended age at introduction and end of supplementation are minor. The European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology Bone Club recommends that all breast-fed infants should receive 10 μg of supplemental vitamin D daily from birth until they are receiving the same amount of vitamin D daily from their diet( Reference Hochberg, Bereket and Davenport 11 ).

In the current study, the majority of the European children received vitamin D supplements. Almost all the infants (96 %) in Northern Europe (Finland and Sweden) were provided vitamin D supplementation daily at the age of 6 months. In an earlier Finnish cohort study, the proportion of children receiving vitamin D supplements was slightly lower: 91 % of infants were given supplements at 6 months of age( Reference Räsänen, Kronberg-Kippilä and Ahonen 16 ). In a large Swedish cohort, 99 % of the infants had received vitamin D supplements during the first year of life( Reference Brekke and Ludvigsson 36 ). In our survey, 96 % of infants were receiving vitamin D supplementation daily at the age of 6 months in Central Europe I countries (transition economies), which include Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Poland. In a previous Polish study, 82 % of infants received regular and 14 % occasional vitamin D supplementation at the age of 6 months( Reference Pludowski, Socha and Karczmarewicz 37 ). In the Central Europe II countries (Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland) 79 % of the infants were given vitamin D supplements daily at the age of 6 months and 76 % of infants in Southern Europe (Italy and Spain). In an earlier Swiss study, only 64 % of infants aged 0–9 months had been given vitamin D supplements within the preceding 24 h( Reference Dratva, Merten and Ackermann-Liebrich 38 ). In a Canadian survey the supplementation rate was higher in 2010 than in our study: 80 % of infants were supplemented with vitamin D at 2 months of age( Reference Crocker, Green and Barr 39 ). In the USA, a low use of vitamin D supplements during infancy has also been reported in previous studies, being only 4–16 % during the first 10 months of life in 2005–2008( Reference Perrine, Sharma and Jefferds 14 , Reference Taylor, Geyer and Feldman 15 ). It is possible that the low rates of supplementation observed in the US TRIGR population are partly due to the fact that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for vitamin D supplementation was introduced only in 2003, after the TRIGR intervention had started. The lack of vitamin D recommendations for the general population in Australia is reflected in the results of the present study and it is likely that the children participating in TRIGR did not belong to those specific groups for whom supplementation has been recommended.

Even though exclusively breast-fed children have greater risk of developing vitamin D deficiency than children receiving infant formula ( Reference Kreiter, Schwartz and Kirkman 7 ), it was observed in a recent Canadian report that also those infants consuming both breast milk and infant formula and those consuming only infant formula represented groups at risk of not meeting the recommended 10 μg of vitamin D daily( Reference Gallo, Jean-Philippe and Rodd 40 ). In a study from the USA it was observed that most (81–98 % during the first 10 months of life) exclusively formula-fed infants met the 2003 American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation (5 μg vitamin D/d) that was applicable during the data collection, but only 20–37 % would have met the current recommendation of 10 μg/d( Reference Perrine, Sharma and Jefferds 14 ). Among infants fed both breast milk and infant formula, only around one-third met the target of 5 μg/d and less than 15 % would have met the current recommendation. In most TRIGR regions, there were no significant differences in vitamin D supplementation between infants exclusively breast-fed for at least 5 months and those who were not. Canada was an exception in this respect; supplement use was more common in the exclusively breast-fed group. Higher frequencies of use compared with the present study but similar difference by breast-feeding status was seen in a report from Canada where 98 % of exclusively breast-fed and 88 % of infants consuming both breast milk and infant formula had received vitamin D supplementation at some point during the first 6 months of life in 2008( Reference Gallo, Jean-Philippe and Rodd 40 ). None of the formula-fed infants had been supplemented with vitamin D. In 2010 in another Canadian study, the supplementation rate of infants receiving only breast milk at 2 months of age was 91 % while the corresponding figures for infants receiving both breast milk and infant formula or only infant formula were 79 % and 20 %, respectively( Reference Crocker, Green and Barr 39 ). Also, in the USA differences in vitamin D supplementation of infants fed only breast milk (5–13 % received supplementation), infants consuming both breast milk and infant formula (4–11 % received supplementation) and infants consuming only infant formula (1–4 % received supplementation) during the first 10 months of life were observed over the time period 2005–2007( Reference Perrine, Sharma and Jefferds 14 ).

Some sociodemographic factors have been associated with the use of vitamin D supplements. Mothers who are younger have been reported to be less likely to give vitamin D supplements to their infants( Reference Räsänen, Kronberg-Kippilä and Ahonen 16 , Reference Dratva, Merten and Ackermann-Liebrich 38 ); this was also seen in our study. Having more than one child in the family may be associated with less use of vitamin D supplements( Reference Räsänen, Kronberg-Kippilä and Ahonen 16 , Reference Dratva, Merten and Ackermann-Liebrich 38 ). Higher maternal education was associated with more frequent use of vitamin D supplements in the current study as has been reported before( Reference Gallo, Jean-Philippe and Rodd 40 , Reference Marjamäki, Räsänen and Uusitalo 41 ).

Vitamin D is particularly important for the skeleton because it is needed for Ca absorption from the intestine. Insufficient vitamin D intake causes rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. Vitamin D supplementation in infancy has also been associated with reduced risk of T1D( Reference Hypponen, Laara and Reunanen 19 ). There is also some evidence that vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases in adults and lower respiratory infections in children( Reference Dawodu and Wagner 42 ). The main natural source of vitamin D is the synthesis in the skin induced by UV radiation from the sun( Reference Cavalier, Delanaye and Chapelle 9 ). With minimal sun exposure, for example at northern latitudes, or due to protective clothing or sunscreen, other sources of vitamin D are required. Because the intake of vitamin D from food is inadequate for most infants, supplementation is necessary. It is clear that new protocols and strategies are needed in some regions to ensure that families get enough information on the importance of adequate vitamin D intake, especially in infancy and childhood. Re-education about the importance of supplementation is essential as families tend to stop using supplements over time( Reference Räsänen, Kronberg-Kippilä and Ahonen 16 ).

Conclusion

The importance of adequate vitamin D intake in infancy is well known and supported by the current recommendations for use of vitamin D supplements. In the present study, the recommendations regarding vitamin D supplementation were quite well followed during the first 6 months of life in European countries and to some extent in Canada. The use of vitamin D supplements was conspicuously low in the USA and Australia. Due to increasing concern regarding the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in childhood, and especially in breast-fed infants, action is needed to train health-care personnel and develop strategies to inform families about the importance of adequate intake of vitamin D in infancy, particularly in those exclusively breast-fed.

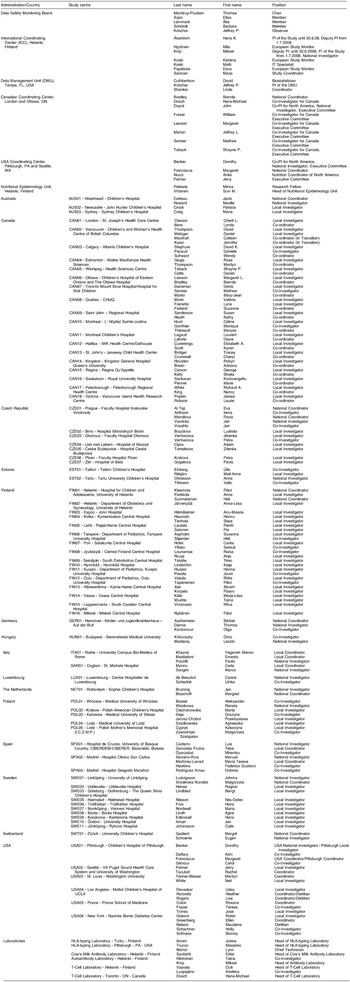

Appendix List of TRIGR investigators for publications/version January 2013

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This work was supported by grant numbers HD040364, HD042444 and HD051997 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health); the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International; the Commission of the European Communities specific RTD programme ‘Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources’, contract number QLK1-2002-00372 ‘Diabetes Prevention’ (the study does not reflect the views of the European Commission and in no way anticipates the Commission's future policy in this area); the Academy of Finland; and the EFSD/JDRF/Novo Nordisk Focused Research Grant. The study formulas were provided free of charge by Mead Johnson Nutrition. Conflicts of interest: None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest. The industry sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript. Authors’ contributions: S.M.V. and D.C. had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: S.M.V., S.S. and M.K. Acquisition of data: A.O., A.N., D.C., M.S., M.F., T.G.-F., D.J.B., J.P.K., M.K. and S.M.V. Analysis and interpretation of data: D.C., S.M.V., E.L., S.S., K.A. and J.P.K. Drafting of the manuscript: E.L., S.S., K.A. and S.M.V. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all of the authors. Statistical analysis: D.C. and J.P.K. Obtained funding: M.K., D.J.B., J.P.K. and S.M.V. Administrative, technical and material support: E.L., S.S., K.A. and M.S. Study supervision: S.M.V., J.P.K. and M.K. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the TRIGR investigators, coordinators, dietitians and study nurses at all clinical sites as well as the Data Management Unit, laboratories and administrative centres for their enthusiasm and excellent work, and also all TRIGR families for their willingness to participate.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013001122