Introduction

The knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are increasingly recognized as vital for strengthening and enriching the foundations of biodiversity conservation (Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Austin, Danielsen and Fernández-Llamazares2021; Molnár et al., Reference Molnár, Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Babai, Díaz, Garnett and Hill2023). Beyond merely filling data gaps and being regarded as ancillary data within scientific research, these knowledge systems provide grounded, place-based perspectives and finely tuned ecological insights that often reveal patterns and changes overlooked by conventional scientific approaches (Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Ban, Claxton and Darimont2022; Wall Kimmerer & Artelle, Reference Wall Kimmerer and Artelle2024). Numerous examples demonstrate how collaboration between scientists and Indigenous Peoples and local communities has significantly deepened our global understanding of species’ ecological distribution ranges, baselines and trends (Dayer et al., Reference Dayer, Silva-Rodríguez, Albert, Chapman, Zukowski and Ibarra2020; Torrents-Ticó et al., Reference Torrents-Ticó, Fernández-Llamazares, Burgas and Cabeza2021). Such observations stem from long-term interaction and experimentation with species and ecosystems, offering rich and novel insights into diverse ecological processes (Durand-Bessart et al., Reference Durand-Bessart, Akomo-Okoue, Ebang Ella, Porcher, Bitome Essono, Bretagnolle and Fontaine2024; López-Maldonado et al., Reference López-Maldonado, Anstee, Neely, Marty, Mastracci and Ngonyani2024).

Indigenous knowledge and local ways of knowing often differ from Western science not only in their epistemological foundations but also in the values and worldviews that shape them (Lopez-Maldonado, Reference López-Maldonado2025), frequently emphasizing relationality, spiritual significance and reciprocity in human–nature interactions (Salomon et al., Reference Salomon, Okamoto, Wilson, Happynook and Mack2023; Teixidor-Toneu et al., Reference Teixidor-Toneu, Fernández-Llamazares, Álvarez Abel, Batdelger, Bell and Caillon2025). However, across these differences, there are important points of convergence and shared conceptual foundations that offer fertile ground for respectful and mutually enriching partnerships (Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Austin, Danielsen and Fernández-Llamazares2021; Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Ban, Claxton and Darimont2022). Collaboration between science-based wildlife monitoring (e.g. radio tracking, telemetry, transect surveys) and observations and knowledge from Indigenous Peoples and local communities can help monitor local biodiversity in more comprehensive ways than relying solely on one single knowledge system (Moller et al., Reference Moller, Berkes, Lyver and Kislalioglu2004; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Maseko, Sosibo, Dlamini, Gumede and Ngcobo2021), in line with the multiple evidence base approach, which emphasizes the value of engaging diverse knowledge systems as equally valid and complementary sources of understanding (Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Brondízio, Elmqvist, Malmer and Spierenburg2014). The idea that diverse knowledge systems can work in mutually enriching ways is reflected in the aspirations of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (McElwee et al., Reference McElwee, Fernández-Llamazares, Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Babai, Bates and Galvin2020).

The vital roles that Indigenous Peoples and local communities have played in advancing global knowledge of biodiversity are increasingly recognized in the scientific literature (Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Ban, Claxton and Darimont2022; Molnár et al., Reference Molnár, Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Babai, Díaz, Garnett and Hill2023). Here, we specifically focus on the field of ornithology, drawing on the knowledge that different communities with long-term histories of place-based living have about the birds in their territories (Moller et al., Reference Moller, Berkes, Lyver and Kislalioglu2004; Iñiguez-Gallardo et al., Reference Iñiguez-Gallardo, Reyes-Bueno, González-Coronel, Freile and Ordóñez-Delgado2024; Lilleyman et al., Reference Lilleyman, Pascoe, Robinson, Legge, Woinarski and Garnett2024). Indigenous Peoples and local communities have developed a sophisticated understanding of the ecological, cultural and spiritual significance of birds, through their direct and intimate interactions with them (Anderson, Reference Anderson2017; Ibarra et al., Reference Ibarra, Caviedes and Benavides2020; Villar et al., Reference Villar, Thomsen, Paca-Condori, Gutiérrez Tito, Velásquez-Noriega and Mamani2024).

The description and interpretation of the place-based relationships between people and birds is the subject of ethno-ornithology (Tidemann & Gosler, Reference Tidemann and Gosler2010). Ethno-ornithologists have long examined the breadth and depth of local bird-related knowledge (Sault, Reference Sault2016; Bonta et al., Reference Bonta, Gosford, Eussen, Ferguson, Loveless and Witwer2017; Wyndham & Park, Reference Wyndham and Park2018). Some of these studies highlight that this culturally grounded knowledge could help fill gaps in our global understanding of bird distribution patterns and trends (Clarke, Reference Clarke2016; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Maseko, Sosibo, Dlamini, Gumede and Ngcobo2021), although some emphasize that this rich place-based knowledge should not be treated as mere instrumental material to fill scientific data gaps (Latulippe & Klenk, Reference Latulippe and Klenk2020; Lopez-Maldonado, Reference López-Maldonado2025). In this study, we view these knowledge systems as holding inherent value, irrespective of their contributions to the advancement of science. Building upon collaborative data collection efforts across multiple sites, we aspire to bring scientific and ethno-ornithological knowledge systems into dialogue to contribute to an enriched understanding of bird diversity patterns and trends.

Substantial research has convincingly shown how mismeasured the avian extinction crisis is (Lees et al., Reference Lees, Haskell, Allinson, Bezeng, Burfield and Renjifo2022; Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Sayol, Andermann, Blackburn, Steinbauer, Antonelli and Faurby2023). Given that many birds have small bones and do not fossilize easily, many bird extinctions have gone unnoticed by science (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Triantis, Wayman, Martin, Hume and Cardoso2024). A corollary to this is that the world is emptier of birds than we probably realize, which in turn undermines our ability to recognize the crucial roles birds play in our wider environments (Dayer et al., Reference Dayer, Silva-Rodríguez, Albert, Chapman, Zukowski and Ibarra2020; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Turvey, Massimino and Papworth2020). Some studies have consistently recorded that the average body mass of birds has declined over time, because large-bodied bird species tend to go extinct more rapidly than small-bodied ones (e.g. Gaston & Blackburn, Reference Gaston and Blackburn1995; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Edwards and Thomas2022; Olah et al., Reference Olah, Heinshohn, Berryman, Legge, Radford and Garnett2024). However, we still do not know the extent to which such changes are being identified, understood, and recorded in the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Examining how place-based communities perceive changes in bird assemblages offers insights into the perceptibility of biodiversity change and highlights the societal implications of the avian extinction crisis.

In this study, we draw on a detailed ethno-ornithological dataset collected during 2019–2021 through a globally coordinated survey with adult participants from Indigenous Peoples and local communities across three continents. To explore whether the perceived shifts in bird species composition over 8 decades (1940–2020) were also associated with changes in body size, we combined this ethno-ornithological knowledge with scientific trait data. Drawing on scientific data about the mean body mass of the different bird species reported, we specifically assess whether the bird species locally reported as most abundant have experienced assemblage-level changes in size over time. Our aim was not simply to juxtapose two separate datasets, but to demonstrate that both knowledge systems can contribute meaningfully and equitably to evidence-making. We approach this dialogue between knowledge systems with deep respect for their distinct epistemological foundations and a recognition of the integrity and value of each knowledge system on its own terms (see researcher positionality statement, below).

Methods

We collected data through in-person surveys conducted within the framework of the Local Indicators of Climate Change Impacts project, a collaborative research project that investigated reports of climate change impacts and other social-ecological changes by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, García-del-Amo, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, Calvet-Mir and Junqueira2024). The main goal of the project was to increase the transferability, applicability and scalability of Indigenous and local knowledge into climate research through the creation of a community of practice that used a standardized protocol for the collection and coding of locally relevant but cross-culturally comparable information (Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, García-del-Amo, Junqueira and Labeyrie2023). Although most of the information collected through this project focused on local understandings of climate change, some parts of the protocol were specifically designed to address other aspects of human–nature relations and communities’ lifeways.

Selection of study sites

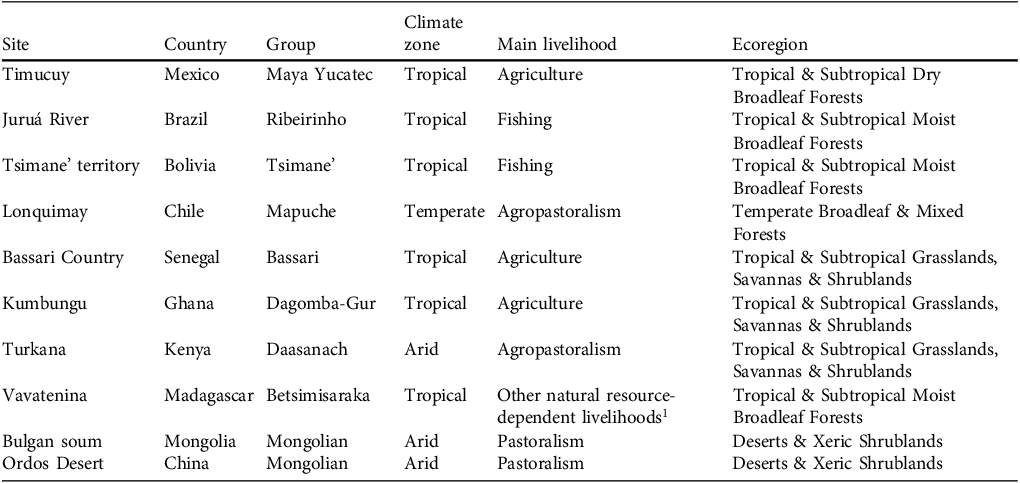

We collected first-hand data at 10 study sites, across 10 countries on three continents, inhabited by place-based communities with predominantly nature-dependent livelihoods (Fig. 1, Table 1). A site was defined as a group of households having relative environmental and sociocultural homogeneity (see Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, García-del-Amo, Junqueira and Labeyrie2023 for study site selection criteria). All the sites are characterized by the presence of Indigenous Peoples or local communities relying on subsistence-oriented activities, but otherwise span a wide range of societal, cultural and environmental features (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Locations of the 10 study sites (Table 1).

Table 1 The 10 sites (Fig. 1), with their main social and ecological characteristics.

1 Activities such as timber extraction, wild plant harvesting and small-scale trade of forest products.

The sites included here are a subset of those originally included in the Local Indicators of Climate Change Impacts project, chosen according to their suitability to contribute to the project’s goals (Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, García-del-Amo, Junqueira and Labeyrie2023). These criteria resulted in a geographically dispersed and diverse collection of 48 study sites. All research partners in these 48 sites were invited to enlarge the protocol and collect bird-related data for this study, with 10 responding to our call (Table 1).

Sample selection

Data were collected in 3–5 villages per site, in each of which one research partner undertook the responsibility of selecting the villages (understood as the lowest administrative unit in an area normally overseen by a leader). The selected villages were intended to be representative and relatively uniform in terms of both the environmental and sociocultural conditions specific to each site (Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, García-del-Amo, Junqueira and Labeyrie2023). Villages exhibiting atypical circumstances (e.g. heavily urbanized) were excluded. Additionally, for logistical efficiency, only villages with < 20 households were selected, and those with > 500 households were subdivided into smaller units.

To select households, we employed simple random sampling, selecting households from a local census (Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, García-del-Amo, Junqueira and Labeyrie2023). Within each household, partners relied on convenience quota sampling among household heads to select 1–2 participants to independently answer our survey, aiming for an approximately equal overall representation across gender and age categories. Convenience quota sampling combines the pragmatic accessibility of convenience sampling with predefined quotas for key variables (e.g. gender, age), ensuring balanced representation while maintaining feasibility in contexts where full random sampling is not possible (Daniel, Reference Daniel2012). In total, we interviewed 690 women (48% of the sample) and 744 men (52% of the sample), with ages of 20–88 years (median 45 ± SD 15.6).

Interview surveys

Surveys were conducted in person, in the local language. To minimize interviewer and coder biases, all partners participated in a 1-week in-person training workshop in Barcelona, Spain, in 2019 (Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Álvarez-Fernández, Benyei, García-del-Amo, Junqueira and Labeyrie2023). In the training, partners were acquainted with the project’s rationale and received comprehensive explanations regarding the implementation of data collection protocols. The training encompassed discussions of the ethical considerations (see Ethical standards, below). In most sites, research partners worked with local researchers fluent in the local language, who helped test the surveys, identify any potential points of confusion, and select the best wording for translation (Supplementary Table 1). All questions were tested with at least 10 people and adjusted if required. This local adaptation and testing phase, involving local researchers and community members, was crucial for ensuring the relevance and clarity of the survey within each cultural context.

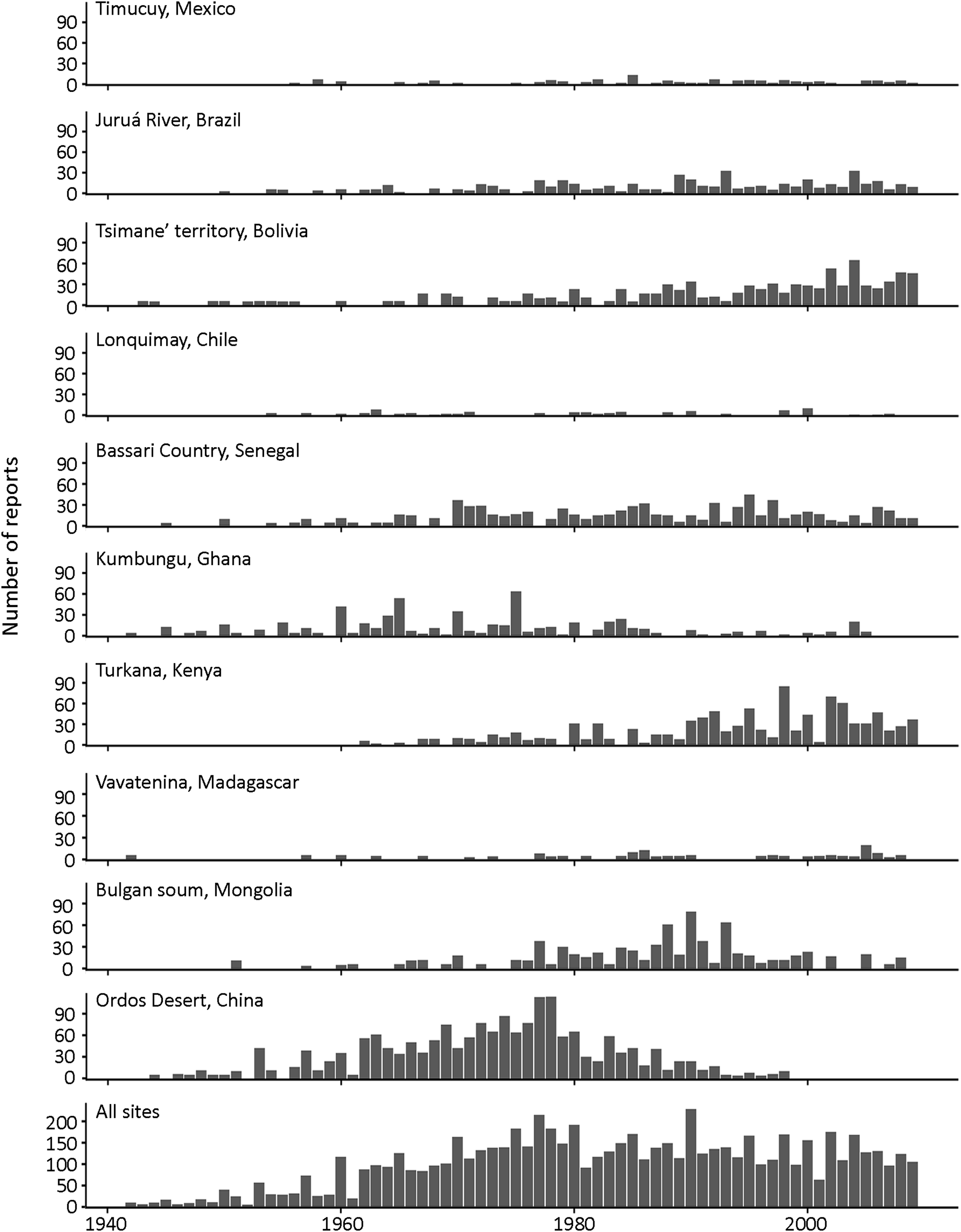

At each site, participants were asked about the three bird species most commonly encountered around their territories in the past when they were c. 10 years old, following previous ethnobiological studies setting the decade of birth as a baseline for assessing ecological changes observed by individuals since their childhood (e.g. Fernández-Llamazares et al., Reference Fernández-Llamazares, Díaz-Reviriego, Luz, Cabeza, Pyhälä and Reyes-García2015; Torrents-Ticó et al., Reference Torrents-Ticó, Fernández-Llamazares, Burgas and Cabeza2021). Additionally, participants were asked about the three bird species most encountered across their territories at present. A total of 1,434 participants reported the presence of birds in the present and in the past (i.e. 1 decade after their birth). The distribution of these observations across time is reported in Fig. 2. At all sites we collected standard sociodemographic data from participants (e.g. age, place of birth), and took notes of any additional insights shared spontaneously during the surveys (e.g. locally perceived drivers of changes in bird assemblages, qualitative observations). Although this qualitative information was not gathered systematically, it offers valuable contextual depth. These statements were not formally analysed but are included as illustrative examples to support and enrich the interpretation of our structured data. We recognize they may not capture the full range of community perspectives, but serve to ground the quantitative findings in locally situated understandings.

Fig. 2 Distribution of bird reports over time in the 10 study sites (Fig. 1) and across all sites combined.

Only individuals who answered both questions (i.e. presence of birds in the present and in the past) were included in the analyses. The year of report for birds in the past was calculated as 2020 (i.e. middle year of 2019–2021) − age of individual + 10. We only considered individuals > 20 years old who were born and raised in the same area. We excluded participants born in the 2010s to avoid the potentially minimal differences in reports between their present and their decade of birth, which could introduce biases into our dataset.

Ethno-taxonomic classification

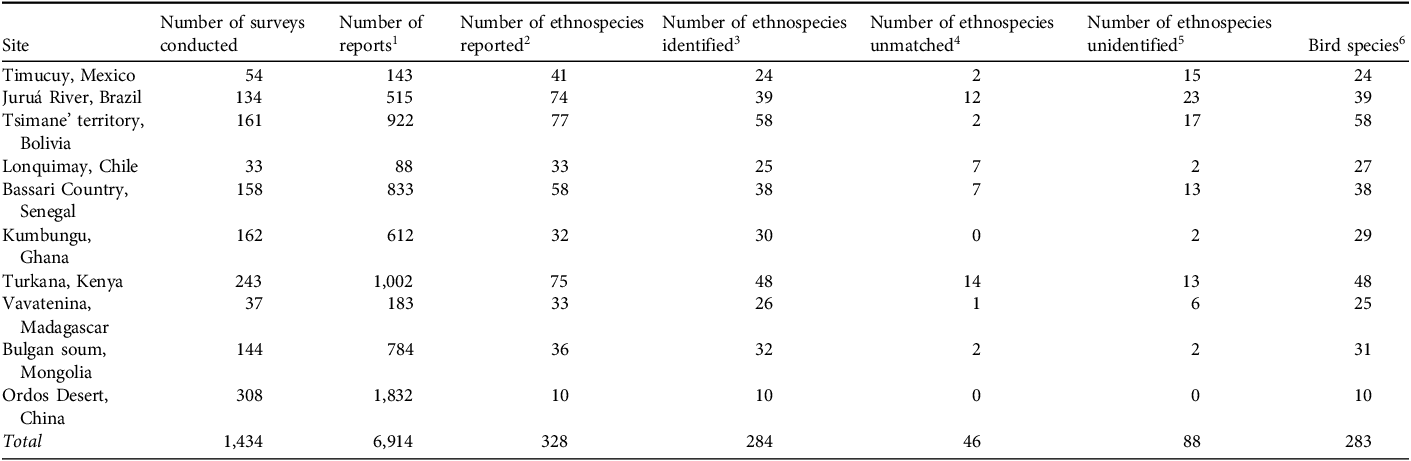

A total of 6,914 bird reports were recorded (i.e. total number of birds that were reported by participants across all surveys; Table 2), corresponding to 283 bird species. Birds were generally reported using vernacular names in local languages. All vernacular names given by participants are referred to as bird ethnospecies. A total of 86% of the bird ethnospecies reported across all study sites (i.e. 95% of all bird reports) were linked to their corresponding scientific name based on site-specific ethno-ornithological research (Supplementary Table 2). We associated a vernacular name with a scientific one when a single species was documented as the equivalent of the vernacular name reported.

Table 2 Ethno-ornithological data collected at each of the 10 sites (Table 1).

1 Individual bird reports reported by participants across all surveys.

2 All distinct vernacular names reported at each site.

3 All ethnospecies for which we were able to find a single corresponding scientific name.

4 All ethnospecies for which we could not identify a single scientific corresponding name.

5 All ethnospecies for which we did not find any scientific information (not even at the genus level).

6 Number of species identified by their scientific name (considering that several ethnospecies can refer to a single scientific species). For Lonquimay, Chile, see main text for details).

Bird ethnospecies for which no reliable corresponding scientific name could be established (i.e. 131 bird ethnospecies, including 87 unidentified and 44 not matched to a single species; Table 2) were excluded from the analyses. These ethnospecies were reported rarely, representing only 4.7% of all bird reports. Although they may hold cultural significance, the absence of clear taxonomic identification precluded their inclusion in the analysis. Additionally, in Lonquimay (Chile), two bird species were biologically identified but lacked corresponding vernacular names, resulting in a slightly higher number of recorded species than identified ethnospecies at that site (Table 2).

Analyses

We did not explicitly ask about changes in the body mass of birds. This information was obtained a posteriori, by combining the information derived from our ethno-ornithological survey with scientific information. For each reported bird species, body mass (in g) was obtained using bird data compiled in the AVONET database (Tobias et al., Reference Tobias, Sheard, Pigot, Devenish, Yang and Sayol2021), the most authoritative global source of bird trait data. This database contains exhaustive functional and morphological trait data for all described bird species, summarized as species averages.

Average decadal body mass was computed as the mean body size of the species reported for that decade and at each site (e.g. bird reports for 1970–1979 were computed as the 1970s). Temporal trends in body mass were assessed at the site level as well as globally with regression models with a logarithmic link and a gamma distribution considering decadal trends. This modelling approach was chosen because the gamma distribution is defined only for positive values, making it particularly suitable for continuous variables such as body mass that cannot take negative values. In addition, the logarithmic link function is commonly used for right-skewed data, as it stabilizes variance and ensures that predicted values remain positive. Together, these features make the gamma regression with a log-link appropriate for modelling temporal trends in body mass.

The same trends were calculated considering annual trends (Supplementary Fig. 1). After a model selection process comparing different order polynomial models and generalized additive mixed models with 4, 5, 6 and 10 knots, we decided to use 2nd order polynomials because of their simplicity and the similarity of results across models (Supplementary Tables 4 & 5). Model comparison was based on both Akaike information criterion with correction for small sample size (AICc; Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002) and root mean squared error of the models (Supplementary Fig. 2–4). Polynomial models using the mean mass per decade against the decade of observation weighted by the inverse of the standard error of the mean were used to account for the potential non-linearity of ecological processes (Lindenmayer & Luck, Reference Lindenmayer and Luck2005; Melo et al., Reference Melo, Ochoa-Quintero, de Oliveira Roque and Dalsgaard2018). This weighting approach intrinsically considers the number of reports per decade, so that decades with fewer observations have relatively lower weight. We stress that our analysis examined changes in body size as a result of changes in the reported species composition of the bird assemblages over time (i.e. we did not assess changes in the size of bird individuals within species over time).

To evaluate the robustness of our results regarding global temporal trends, we ran a generalized linear mixed model, assessing the mean mass by year of observation and using site as a random factor. Models and visualizations were generated in R 4.3.0 (R Core Team, 2023), using the packages lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) and ggplot2 (Wickham Reference Wickham2016), respectively. Package car (Fox & Weisberg, Reference Fox and Weisberg2019) was used to assess model significance.

Researcher positionality statement

We approach this research as a transdisciplinary team of ethnobiologists, anthropologists, ecologists and environmental scientists that includes both Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, with affiliations across institutions in the Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe (Supplementary Table 1). Although most of us were primarily trained within Western scientific traditions, many authors have long-standing collaborative relationships with Indigenous Peoples and local communities and bring lived experiences and diverse epistemological perspectives to this study. We are committed to fostering equitable collaborations that recognize and respect the distinct contributions of different knowledge systems. Importantly, we view Indigenous knowledge and local ways of knowing as holding intrinsic value in their own right, and not solely for their alignment with or contributions to science. In this study, we have engaged with these knowledge systems through ethically grounded practices of collaboration based on mutual respect, trust and reciprocity.

Results

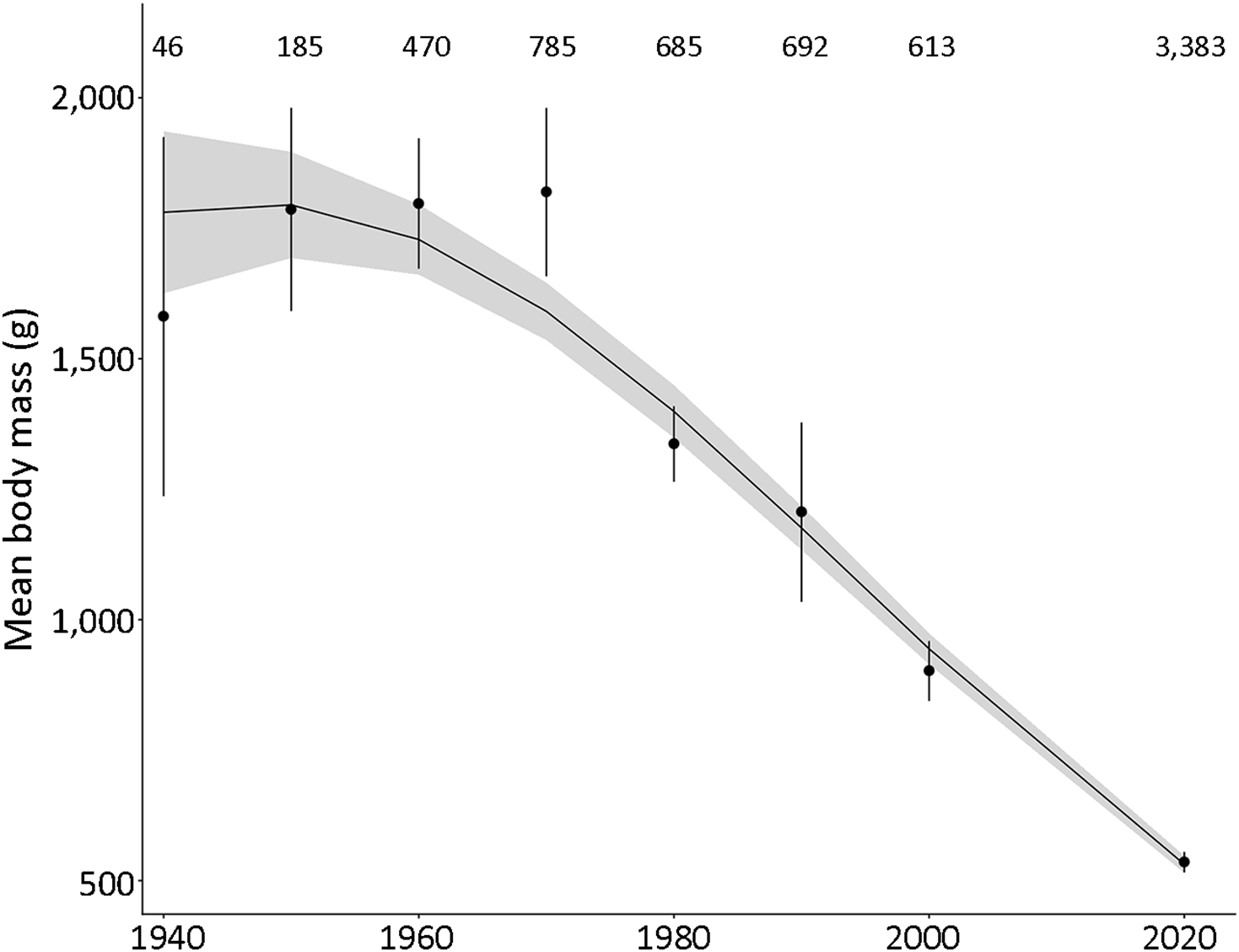

The mean decadal body mass of the assemblage of reported bird species significantly decreased from the 1940s to the 2020s across all 10 study sites (Fig. 3; F = 282.9, df = 2, P < 0.001). In the 1940s, the mean body mass of the assemblage of reported bird species was 1,580.7 ± SE 344.1 g, whereas the mean body mass of reported bird species in the 2020s was 535.4 ± SE 19.7 g, indicating an overall body mass reduction of c. 66%. This general decline was corroborated by our model assessing mass against year of observation, which showed a 72% decline from 1940 to 2020 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 3 Mean body mass ± SE of the assemblage of reported birds per decade (P < 0.001). The black line is a simple polynomial model of the mean mass per decade against decade of observation weighted by the inverse of the standard error. This weighting approach intrinsically considers the number of reports per decade (shown above the data plot), so that decades with fewer reports have relatively lower weight. The grey shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval around the weighted polynomial model of mean body mass per decade. There is no data for the 2010s, because individuals born in this decade were excluded from the analysis (see text for further details).

Within the general pattern of decreasing mean decadal body mass of reported bird species, variations across sites emerged. Notably, differing mean body masses were recorded in the starting decade of our trends, the 1940s. For instance, in Timucuy (Mexico), Juruá River (Brazil), Bassari Country (Senegal), Kumbungu (Ghana), Turkana (Kenya), and Vavatenina (Madagascar), the mean body mass of reported bird species was < 1,000 g, whereas in Tsimane’ territory (Bolivia), Lonquimay (Chile), Bulgan soum (Mongolia) and Ordos Desert (China), it was > 1,000 g. Substantial variation in site-specific patterns over time was also evident. Four sites showed a statistically significant decline (P < 0.05) in mean decadal body mass of reported birds from the 1940s to the 2020s (Tsimane’ territory in Bolivia, Timucuy in Mexico, Vavatenina in Madagascar, and Ordos Desert in China; Fig. 4). Other sites had non-significant trends, although most of them showed consistent declines over the last 4 decades, with the notable exceptions of Lonquimay (Chile) and Bulgan soum (Mongolia).

Fig. 4 Mean body mass ± SE of the assemblage of reported birds per decade, by site (Supplementary Fig. 2). Each line is a simple polynomial model of the mean body mass per decade against decade of observation weighted by the inverse of the standard error. This weighting approach intrinsically considers the number of reports per decade, so the decades with fewer reports have relatively lower weight. Solid and dashed lines indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) and non-significant trends, respectively. (P-values are indicted in parentheses with the site name). The grey shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval around the weighted polynomial model of mean body mass per decade. There are no data for the 2010s, because individuals born in this decade were excluded from the analysis (see text for further details). Note the differences in the y-axis scales.

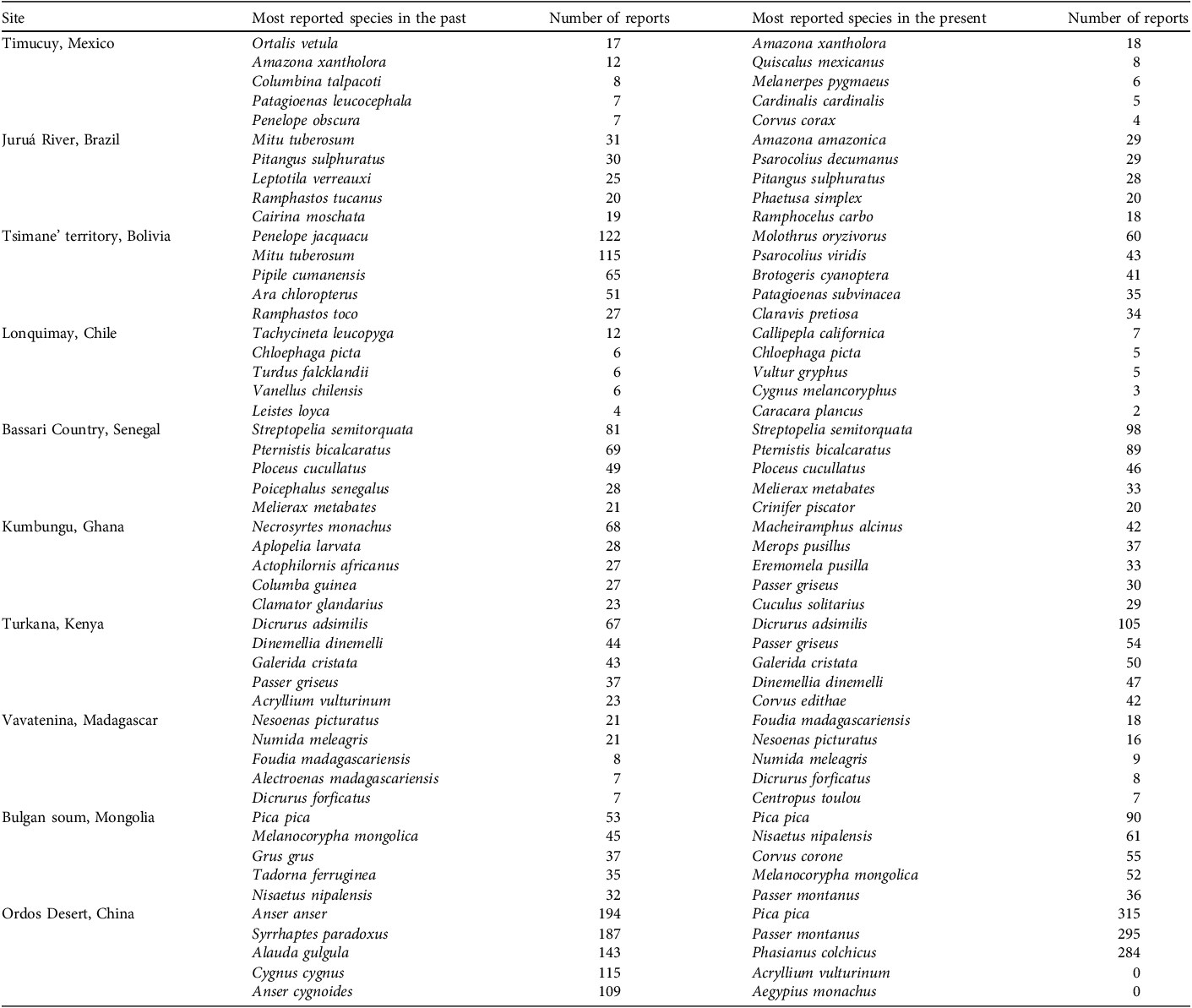

When comparing the bird species most reported in the past and in the present across all sites, the tendency to report smaller bird species in the present than in the past became apparent (Plate 1), even though the species reported varied substantially from one site to another (Table 3). Whereas six of the 10 bird species most reported in the past were > 1,000 g, only two out of the 10 most reported bird species in the present were > 1,000 g (Supplementary Table 3).

Plate 1 The five most reported bird species in the past and in the present across all 10 sites (see Table 3 for the five most reported bird species in each site). The number of reports is the addition of the individual reports of each bird species being reported as one of the most common species across all sites. Photographs: Daniel Burgas (A. anser, D. adsimilis, P. pica, P. montanus and S. semitorquata), Joan de la Malla (M. tuberosum, P. jacquacu and P. colchicus), Vedant Kasambe (A. gulgula) and Andrew Bazdyrev (S. paradoxus).

Table 3 The five most reported bird species in the past and the present, by site. The number of reports is the sum of the individual reports of each species reported by each person interviewed as one of the three most common species at each site.

Although our surveys were based on the listing of species, participants offered unsolicited qualitative explanations for the drivers of change. For example, ‘All the big birds are now gone’, reported a Daasanach elder in Turkana, Kenya. ‘Many animals have disappeared, because they [loggers] hunt more. They kill too many animals’, said another knowledge holder in the Tsimane’ territory, in the Bolivian Amazon. ‘Because now we have too many livestock, birds’ nests in the pasture areas have become much fewer. And the larger birds often die on the electricity grids’ said a herder from Bulgan soum, in Mongolia. Referring to the razor-billed curassow Mitu tuberosum, one of the largest bird species reported in the Juruá River, in Brazil, a ribeirinho informant stated ‘Before there was more mutum than today, because people have hunted a lot and also because they get scared of the noises and go away’. Although not derived from systematic analysis, these reflections offer meaningful glimpses into local perceptions of change and help contextualize the quantitative trends observed.

Discussion

Our analysis across 10 study sites on three continents reveals that Indigenous Peoples and local communities tend to report that the bird species around their territories are now smaller compared to the bird species in the past. Although a general pattern of decreasing mean decadal body mass of reported bird species emerges from the aggregated data, this trend is not uniform. There is substantial site-level variation in the strength, direction and significance of this pattern. In some sites, changes are pronounced and statistically significant, whereas in others, such as Lonquimay (Chile), the trend is weaker or absent altogether. This heterogeneity underscores the importance of interpreting these findings in the light of local ecological contexts, sociocultural dynamics and historical baselines. The observed patterns can be interpreted through two different, albeit not necessarily mutually exclusive, processes: (1) a local extinction of large-bodied bird species at the study sites, and (2) decreasing interactions with nature, resulting in the erosion of knowledge about large-bodied bird species. Each of these potential explanations is discussed below.

Firstly, this research adds further depth to science-policy discussions on the global avian extinction crisis (Lees et al., Reference Lees, Haskell, Allinson, Bezeng, Burfield and Renjifo2022; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Triantis, Wayman, Martin, Hume and Cardoso2024) by showing that a shift towards small-bodied bird species can be traced in the collective memory of 10 place-based communities with long-term connections to their local ecosystems. These findings suggest that large-bodied bird species could be becoming less abundant and replaced by smaller species. Such results align with recent studies showing a process of morphological homogenization across the avian class (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Edwards and Thomas2022), and large-bodied bird species being most likely to be threatened (Olah et al., Reference Olah, Heinshohn, Berryman, Legge, Radford and Garnett2024; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Triantis, Wayman, Martin, Hume and Cardoso2024). Our results are further corroborated by qualitative evidence emerging from our surveys. Overall, the evidence seems to indicate that bird assemblages at these sites are generally shifting towards more cosmopolitan and smaller bird species (Plate 1). Although we did not delve into the locally perceived drivers of such shifts, our in-depth ethnographic understanding of the social-ecological realities in these sites suggests these changes are related to increasing hunting pressure (e.g. increasing use of firearms in the Tsimane’ and Juruá sites in the Amazon), habitat loss (e.g. agricultural expansion in Vavatenina in Madagascar, and Bassari territory in Senegal), and the impact of infrastructure development (e.g. bird collisions with power lines in Inner Mongolia).

Secondly, studies have shown that many societies are becoming increasingly disconnected from their local ecosystems and the birds they harbour (Lyver et al., Reference Lyver, Timoti, Davis and Tylianakis2019; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Turvey, Massimino and Papworth2020). As such, younger generations could be reporting smaller bird species as being more abundant around their territories, either because large-bodied species are disappearing, or because smaller birds tend to be more common around human settlements (Neate-Clegg et al. Reference Neate-Clegg, Tonelli, Youngflesh, Wu, Montgomery and Şekercioğlu2023). This pattern may also reflect the phenomenon of the shifting baseline syndrome, whereby each generation perceives the environmental conditions of their youth as normal, potentially masking longer-term ecological change (Fernández-Llamazares et al., Reference Fernández-Llamazares, Díaz-Reviriego, Luz, Cabeza, Pyhälä and Reyes-García2015; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Turvey, Massimino and Papworth2020). Current socioeconomic trends towards adopting Western lifestyles have disrupted the integral relationships that many Indigenous Peoples and local communities have with their local ecosystems (Fernández-Llamazares et al., Reference Fernández-Llamazares, Lepofsky, Lertzman, Armstrong, Brondizio and Gavin2021). We consider it plausible that similar trends could be occurring in some of our study sites (e.g. rapid cultural erosion has been documented among the Tsimane’ in Bolivia, the Daasanach in Kenya and the Bassari in Senegal; Reyes-García et al., Reference Reyes-García, Guèze, Luz, Paneque-Gálvez, Macía and Orta-Martínez2013; Torrents-Ticó et al., Reference Torrents-Ticó, Fernández-Llamazares, Burgas and Cabeza2021, Reference Torrents-Ticó, Fernández-Llamazares, Burgas, Nasak and Cabeza2023; Porcuna-Ferrer et al., Reference Porcuna-Ferrer, Calvet-Mir, Guillerminet, Alvarez-Fernandez, Labeyrie, Porcuna-Ferrer and Reyes-García2023). If bird species become scarcer or if the knowledge about them is disrupted, opportunities to engage with them through traditional cultural practices are likely to decline (Lyver et al., Reference Lyver, Timoti, Davis and Tylianakis2019). Given that the long-term relations established with bird species link these communities to other values such as cultural identity, connection to place, and community well-being, among others (Turpin et al., Reference Turpin, Ross, Dobson and Turner2013; Villar et al., Reference Villar, Thomsen, Paca-Condori, Gutiérrez Tito, Velásquez-Noriega and Mamani2024), establishing ethno-ornithological studies in these areas could be central to biocultural conservation efforts (Lilleyman et al., Reference Lilleyman, Pascoe, Robinson, Legge, Woinarski and Garnett2024).

One limitation of this study is the exclusion of several bird ethnospecies reported by participants that we could not confidently identify taxonomically. Lacking sufficient information to determine their corresponding biological species, these reports were excluded from the body mass analysis to ensure methodological consistency and comparability across sites. However, we recognize this decision reflects a broader tension inherent in research across knowledge systems. Rare or unidentified ethnospecies may embody locally significant observations, culturally important taxa or early indicators of ecological change. Their exclusion, while necessary in this context, highlights the epistemological limitations of conventional approaches and points to the need for more inclusive, reflexive methodologies that engage more fully with the diverse knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Overall, our findings suggest a notable alignment between the long-term observations shared by Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and recent scientific data documenting a global avian decline (e.g. Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Triantis, Wayman, Martin, Hume and Cardoso2024; WWF & ZSL, 2024). Rather than seeking to validate one knowledge system with another, we view this convergence as underscoring the magnitude and urgency of the avian extinction crisis (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Maseko, Sosibo, Dlamini, Gumede and Ngcobo2021; Lees et al., Reference Lees, Haskell, Allinson, Bezeng, Burfield and Renjifo2022). In this context, it is paramount to recognize the fundamental roles that Indigenous Peoples and local communities can play in ornithological research and conservation efforts (Tidemann & Gosler, Reference Tidemann and Gosler2010; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Maseko, Sosibo, Dlamini, Gumede and Ngcobo2021). Establishing ethical partnerships for knowledge co-creation between scientists and Indigenous Peoples and local communities, where scientific goals are aligned with the knowledge, views, needs and priorities of such communities, can broaden and deepen our understanding of the complex social-ecological processes underpinning bird–people connections globally (Moller et al., Reference Moller, Berkes, Lyver and Kislalioglu2004; Dayer et al., Reference Dayer, Silva-Rodríguez, Albert, Chapman, Zukowski and Ibarra2020).

Author contributions

Study conception and design: ÁF-L, SÁ-F, SF, ABJ, DB, MC, MT-T, VR-G; project administration: SÁ-F, LC-M, DGdA, ABJ, XL, VP, AP-F, AS, RS, VR-G; data collection: ÁF-L, AP-F, JC-S, RC, EC, TG, TH, YL-M, JM, EMNANA, MT-T, TU, RW; data cleaning: ÁF-L, SÁ-F, SF, DB, MC, MT-T; data analysis: ÁF-L, SÁ-F; writing: ÁF-L, SÁ-F, SF, MT-T; revision: all authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the people and communities who participated in this research for sharing their time and wisdom with us. The collective knowledge that constitutes the basis for the analyses presented here belongs to the 10 communities with whom we have worked and represents their shared intellectual property. We thank all the partners of the Local Indicators of Climate Change Impacts project, Petra Benyei for her coordination support, and Joan de la Malla for some of the photographs in Plate 1. Research leading to this paper has received funding from the European Research Council under a Consolidator Grant (FP7-771056-LICCI). ÁF-L was supported by a Ramón y Cajal grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RYC2021-034198-I) and the European Union through a Starting Grant from the European Research Council (ERC, IEK-CHANGES, 101117423). SF received financial support from the Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral program of the Government of Catalonia (2021-BP-00134). JC and JTI received support from the Center for Intercultural and Indigenous Research CIIR–ANID/FONDAP 15110006, Center of Applied Ecology and Sustainability CAPES–ANID PIA/BASAL FB0002, and Cape Horn International Center CHIC–ANID PIA/BASAL PFB210018. This work contributes to the “María de Maeztu” Programme for Units of Excellence of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CEX2024-001506-M funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) awarded to the Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of our institutions or funding agencies, including the European Union and the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the grant authority can be held responsible for any views and opinions expressed.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The Ethics Committee of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona approved the research protocol used in this project (CEEAH 4781). This research adheres to the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE, 2006) and abides by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. Before data collection began, we obtained research permits from local authorities at each site, and free, prior, informed consent from the political organizations representing the communities with whom we worked, and from each individual participant. Where necessary, we also obtained authorizations from national ethics committees and additional research permits (Supplementary Table 1). All procedures and documents were reviewed by an external, independent ethics advisor appointed by the European Research Council. In community meetings, partners facilitated an open dialogue in which participants were given the opportunity to express their preferences on how they wished the information to be returned and to communicate any additional requirements. Information has been returned through community meetings, dialogues with local leaders, seminars at local research institutions and/or the production of dissemination materials.

Data availability

The data generated and analysed, and the R script, are available at doi.org/10.34810/data1849.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article is available at doi.org/10.1017/S0030605325102615