1. Introduction

The Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) initiative has been focused on creating a global inventory of glacier outlines (outside of Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets) since 1995. GLIMS began with the creation of data acquisition requests for the ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer) instrument (Raup and others, Reference Raup, Kieffer, Hare and Kargel2000), using those optimized images to map glaciers around the world, and continues glacier mapping using various satellites. The result is a database, housed at the National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (NSIDC DAAC, one of the archive centers for NASA data), of multi-temporal glacier outlines and metadata on how they were produced, with as-of dates from the Little Ice Age (c. 1800, depending on location) to the present. The database is globally complete, and while many glaciers have only one or two outlines, some have twenty or more.

A related data product is the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) (Pfeffer and others, Reference Pfeffer2014; RGI 7.0 Consortium, 2023), which is a subset created directly from the GLIMS Glacier Database. The current version of the RGI, version 7.0 (Maussion and others, Reference Maussion2023), has outlines (one per glacier) as close as possible to the year 2000. Future versions will target other times, likely starting with more recent years. The RGI is packaged in a simple shapefile format and is designed to be easy to use by glacier modelers and others.

Without exception, glaciers in all regions of the world are losing mass (Gardner and others, Reference Gardner2013; Zemp and others, Reference Zemp2017; The GlaMBIE Team, 2025). Because the state of a glacier reflects the average of short-term weather and responds to local climatic conditions, glaciers are visible and easily understood indicators of climate change. When a glacier goes extinct, the illustration of climate warming is even starker. Recognizing the importance of keeping a record of extinct glaciers, GLIMS was augmented in 2023 to be able to mark a glacier as “extinct”.

2. Definition and methods

What does it mean for a glacier to be “extinct”? For the purpose of registering glaciers’ disappearance in GLIMS, we decided on the following:

• A glacier that has completely melted away, or shrunk to the extent that it no longer is considered by experts to be a glacier, is deemed “extinct” (the term “vanished” is sometimes used interchangeably). Many national glacier inventories use a size cutoff (which can vary) to exclude snow and ice patches that are too small to be detected as glaciers within the limits of the imagery used. Other inventories do sometimes include small ice bodies that may have been glaciers in the past. Such small ice bodies are of interest to glacier archaeologists (Andreassen and others, Reference Andreassen, Nagy, Kjøllmoen and Leigh2022). The availability of high resolution aerial and satellite images also enables mapping of very small (e.g. less than 0.02 km2) glaciers and ice bodies (Fischer and others,Reference Fischer, Huss, Barboux and Hoelzle2014; Paul and others, Reference Paul, Winsvold, Kääb, Nagler and Schwaizer2016; Andreassen and others, Reference Andreassen, Nagy, Kjøllmoen and Leigh2022), sometimes called “glacierets” (Cogley and others, Reference Cogley2011). In GLIMS the recommendation of the regional collaborators is followed for registering a glacier as “extinct”.

• The focus is on glaciers that have been mapped within the GLIMS initiative; in practice this incorporates the last 25–75 years. Clearly, many glaciers have vanished since their Little Ice Age maximum extent, but here we are interested in glaciers that are victims of more recent changes to climate.

Most determinations of a glacier’s demise are based on remote sensing assessments of glacier area. Other definitions do exist, however. Glacier flow, or lack thereof, can also be determined from space-based measurements of flow velocities. A glacier can be defined as “A perennial mass of ice, and possibly firn and snow, originating on the land surface by the recrystallization of snow or other forms of solid precipitation and showing evidence of past or present flow” (Cogley and others, Reference Cogley2011). When an ice body has shrunk below a size cutoff (e.g. 0.05 km2) and has become stagnant, it is no longer an active glacier, but it is still a glacier according to this definition. Our decision in GLIMS to rely on local glacier experts reflects these slightly varying criteria.

Once a researcher has determined that one or more glaciers have disappeared, data on each glacier can be sent to the GLIMS team at NSIDC for marking as “extinct” in the GLIMS Glacier Database. For each glacier, data must include: GLIMS Glacier ID, estimated year of extinction, uncertainty in this date, and a note on source of information, such as an image ID. An example from New Zealand would look like: “G170154E43469S, 2020-03-03, 1, image_id_X”. When downloading GLIMS data, the included field “glacier_status” (or “glac_stat”) is “exists” for still-existing glaciers, and “gone” for ones marked as extinct.

3. Geographic distribution

GLIMS currently records “extinct” status for 181 glaciers, distributed widely around the globe (Fig. 1). The extinct glaciers include: glaciers from New Zealand and western North America, ice caps from Arctic Canada, all glaciers in Venezuela, several from the southern tip of South America, and many from Scandinavia, the Pyrenees, and the European Alps. From discussions with colleagues around the world, we are certain that this is a small subset of the glaciers that have likely disappeared in the last 50 years. We are thus at the first stages of compiling this data atribute for the globe, and solicit more submissions from the community. At present, the larger number in the Northern Hemisphere results from the fact that early submitters of this information have mostly been from Europe or North America. The following are examples of glaciers registered as extinct in the GLIMS Glacier Database as of August 2025.

Figure 1. Distribution of glaciers registered as “extinct” as displayed in the GLIMS Glacier Viewer. More are thought to have disappeared than are shown here.

3.1. Example from USA

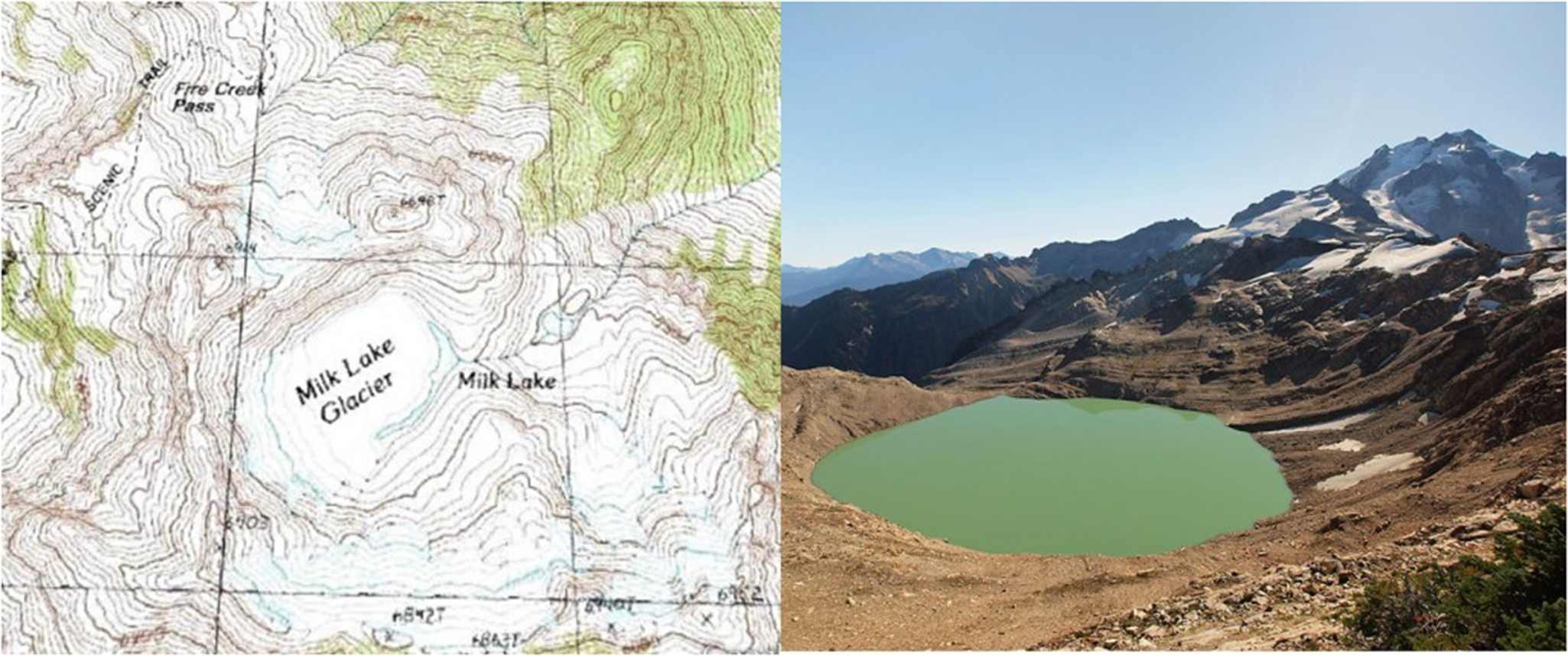

A recent data set by Fountain and others (Fountain and others, Reference Fountain, Glenn and McNeil2023) provided an updated inventory of glaciers for the USA (not including Alaska) up to 2015 identifying those from previous inventories that had been lost. They found that 52 previously identified glaciers could no longer be classified as glaciers, either due to transformation to snow patches or complete disappearance. Oregon Glacier Institute has conducted field investigation of glaciers in the Oregon Cascades and identified several that have vanished, including Clark and Glisan (Bakken-French and others, Reference Bakken-French, Boyer, Southworth, Thayne, Rood and Carlson2024). The North Cascade Glacier Climate Project carried out observations on 31 glaciers in the range, mapped in the first GLIMS inventory, that are no longer glaciers. In each case the glaciers have been observed in person. Hinman, Ice Worm, Lewis, Lyall, Milk Lake (Fig. 2), Snow Creek and Spider Glacier are examples (Pelto and Brown, Reference Pelto and Brown2012; Pelto and Pelto, Reference Pelto and Pelto2025). In collaboration with the Global Glacier Casualty List, specific reports on the loss of Darwin Glacier, Sierra Nevada, California and Anderson Glacier, Olympic Mountains, Washington have also been completed (Boyer and Howe, Reference Boyer and Howe2025b).

Figure 2. Milk Lake Glacier in 1958 USGS map and in 2009, now just Milk Lake. At the time of Pelto’s team’s first two visits to this glacier in 1986 and 1994 it was still present. (Photo: M. Pelto).

3.2. Example from Canada

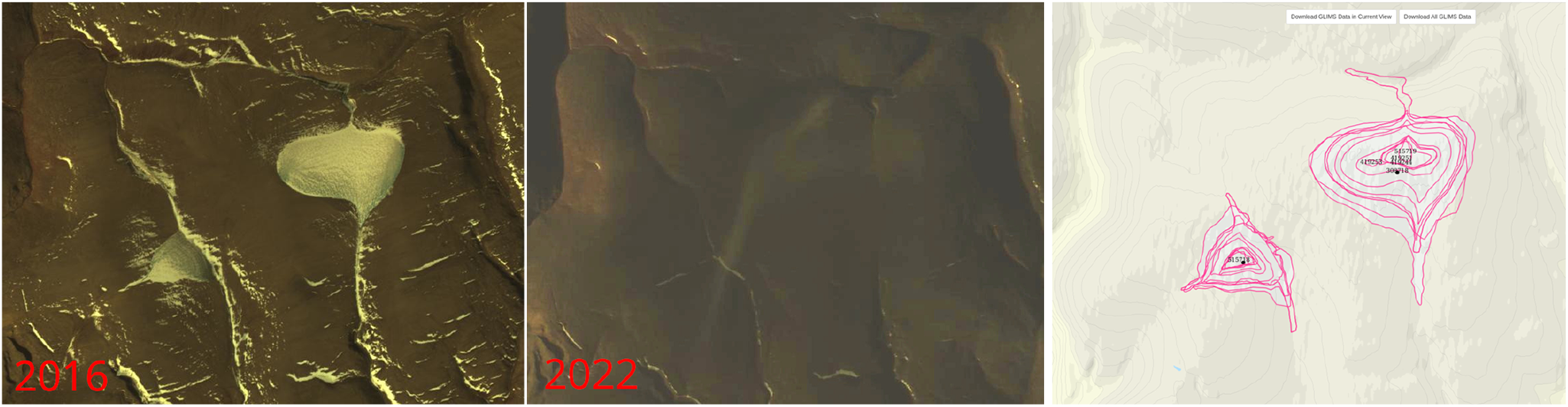

The Arctic is warming almost four times faster than the globe (Rantanen and others, Reference Rantanen2022), and the disappearance of smaller ice caps has been a result (Fig. 3). The Hazen Plateau ice caps had been shrinking since the 1980s at latest, and the pace accelerated since then (Serreze and others, Reference Serreze, Raup, Braun, Hardy and Bradley2017). These two ice caps had vanished by 2020, as shown by analysis by Raup and data in GLIMS.

Figure 3. The two Hazen Plateau ice caps on Ellesmere Island, Canadian Arctic, that disappeared in c. 2020. Left: 2016; center: 2022; right: outlines from 12 different years in GLIMS, spanning 1959–2017. These are now registered as “extinct” in the GLIMS database.

3.3. Example from France

For the French Alps, a multitemporal glacier inventory was contributed by local experts to the GLIMS database. The oldest outline represents the maximum extent during the Little Ice Age (Gardent and others, Reference Gardent, Rabatel, Dedieu and Deline2014). Depending on the glacier, the Little Ice Age maximum dates back from the mid-17th or the first half of the 19th century. This outline has been mapped from geomorphological evidence (e.g., moraines). In Fig. 4, we show the LIA extents and more recent outlines for glaciers at the sources of the Arc and Isère rivers: (1) the one of the late 1960s–early 1970s (named ‘1970’ in Fig. 4) mapped from the first topographical maps with a 1:25000 scale made by the French National Geographical Institute (IGN); (2) the one of the late 2000s mapped from aerial photographs taken between 2006 and 2009 depending on the glaciers (Gardent and others, Reference Gardent, Rabatel, Dedieu and Deline2014); and the recent most update of the glacier inventory in the French Alps made from Sentinel-2 images of August 2022 (Rabatel and Klee, Reference Rabatel and Klee2023). From Fig. 4, one can note that most of the glaciers’ disappearance in this sector of the French Alps occurred during the last 50 years.

Figure 4. Glaciers at the sources of the Arc and Isère rivers, French Alps. The different outlines show the glaciers’ extent at the Little Ice Age maximum (about 1850 CE) in black, in 1970 in blue, 2006 in yellow and 2022 in red (background image comes from Bing aerial).

3.4. Example from Norway

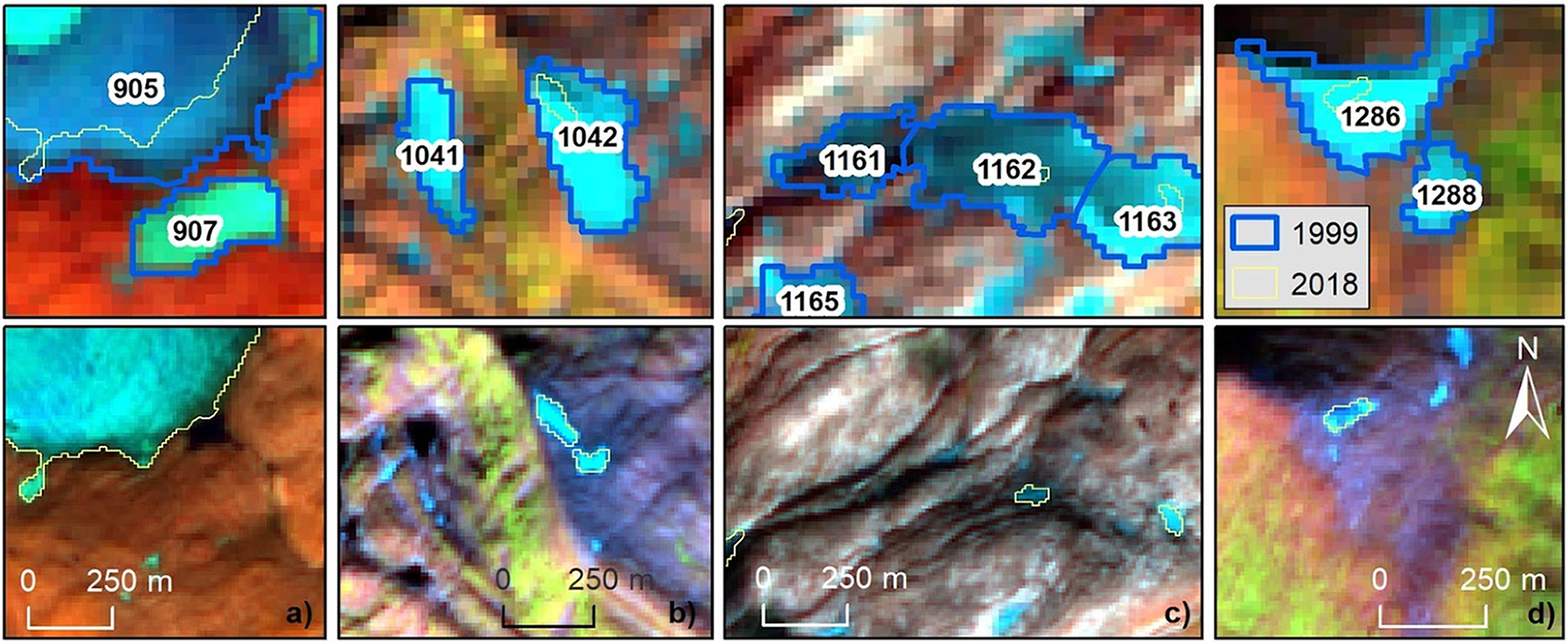

Two digital satellite based inventories have been compared (Andreassen and others, Reference Andreassen, Nagy, Kjøllmoen and Leigh2022) to assess extinct glaciers in Norway. The 1999-2006 Landsat based inventory of 30 m spatial resolution was compared with the 2018-2019 Sentinel-2 based inventory of 10 m spatial resolution. In this region snowfields can be persistent and change little over time. A challenge is therefore to distinguish glaciers from snow fields. The comparison revealed that, in total, 20 small glacier units disappeared from Norway between 1999 and 2018 (Fig. 5) (Andreassen and others, Reference Andreassen, Nagy, Kjøllmoen and Leigh2022). Moreover, several smaller glaciers had almost disappeared. All Norwegian extinct glaciers were in northern Norway and marked as extinct in GLIMS. There are as yet no large glaciers with names that have completely disappeared, but Breifonn (Andreassen and others, Reference Andreassen, Robson, Smith, Weber, Carrivick and Kjøllmoen2025) and a nameless glacier in southern Norway are examples of glaciers that had almost disappeared between the inventories, from 2003/2006 to 2019.

Figure 5. Example of small glaciers that went extinct between 1999 and 2018 in northern Norway. Numbers are national (local) IDs. Background images: upper row Landsat 7 ETM+ (30 m resolution) from 1999, and lower row Sentinel-2 (10 m resolution). Figure from Andreassen (Reference Andreassen2022).

3.5. Other regions

Glacier retreat and disappearance is striking in many regions. The remaining Pyrenees glaciers are small and shrinking, and are expected to disappear in the 2030s (Vidaller and others, Reference Vidaller2021; Izagirre and others, Reference Izagirre2024; López-Moreno and others, Reference López-Moreno, Revuelto, Izagirre, Alonso-González, Vidaller and Bonsoms2025). GLIMS now records 27 Pyrenean glaciers as extinct. In Switzerland, by comparing the two detailed glacier inventories from 1973 and 2016, Linsbauer and others (Reference Linsbauer, Huss, Hodel, Bauder and Barandun2025) found that 1019 glaciers, 40% of the number in 1973, had disappeared. These have not yet been marked as extinct in GLIMS. Continued retreat of glaciers in Bolivia and Venezuela has led to extinction for some in Bolivia and all glaciers in Venezuela (Ramirez and others, Reference Ramirez2001; Reference Ramirez, Melfo, Resler and Llambi2020). Glaciers in southern South America are retreating as well, and while GLIMS has documented only one extinct glacier there so far, we expect this number to increase as more analysis is done.

4. Global glacier casualty list (GGCL)

The GLIMS team is coordinating and sharing data with other initiatives aimed at documenting extinct glaciers around the world. One such effort is the Global Glacier Casualty List (Boyer and Howe, Reference Boyer and Howe2025b), which launched in August 2024 as a collaboration between Rice University, the University of Iceland, the Icelandic Meteorological Office, ETH Zurich, CONICET (Argentina), University of Bristol, the Arctic Council, the World Glacier Monitoring Service, and UNESCO. The GGCL is a platform for communicating scientific information and stories about individual disappeared and soon-to-disappear glaciers. GGCL focuses on glaciers that have disappeared in the past twenty years or that are highly likely to vanish in the next twenty years. Like GLIMS, the GGCL team respects that there are different regional and local criteria for glacier loss and multiple scientifically valid standards for identifying when a particular glacier can be declared “extinct”. GGCL currently features 35 StoryMaps (combination of text, images, videos, and interactive maps to tell a story) of extinct glaciers from around the world, each of which emphasizes a blend of scientific documentation of the disappearance of the glacier together with information on the cultural, economic and social impacts for specific communities and settlements nearby (Boyer and Howe, Reference Boyer and Howe2025a). This emphasis on impacts on humans from vanishing glaciers (whether in the form of cultural heritage losses, agricultural or energy disruption, water insecurity or diminished tourism) is designed to make the immediate human stakes in extinct glaciers clearer (Boyer, Reference Boyer2024; Howe and Boyer, Reference Howe and Boyer2024, Reference Howe and Boyer2025).

5. Discussion and conclusion

The processes of glacier retreat, possible break-up, and mass loss are complex in general. The transition from “glacier” to “extinct glacier” is therefore also complex. Year-to-year mass change and end-of-year snow line elevation (a proxy for equilibrium line altitude (ELA)) are parameters that directly relate to climate. Changes in glacier geometry depend on the dynamics of the glacier (which depend on overall geometry, ice temperature, presence/absence of water at the terminus, etc.), lag behind mass changes, and are therefore less directly related to climate than the mass changes. As a glacier loses mass, it may physically fragment such that the number of glaciers can increase.

Whether one counts these pieces as additional glaciers that can then go extinct, or treats these as ephemeral ice masses that are never considered glaciers, and therefore never “extinct glaciers,” is somewhat arbitrary, since the starting date for such consideration is arbitrary. The general approach in GLIMS is to record data in as much detail as available to enable end users to filter and analyze the data as they deem appropriate.

Counting glaciers, in general, is not straight-forward. Ice bodies are inconsistently mapped, sometimes divided into separate “glaciers” along flow divides and sometimes not (Windnagel and others, Reference Windnagel2022), and glaciers can physically fragment over time as they shrink. On top of this, imagery can be difficult to interpret: snow conditions can lead to overestimation of the areal extent or hide glacier ice. Counting extinct glaciers is similarly complicated. For example, the total number of ice bodies that have disappeared from the main glacierized massifs of the French Alps (Mont-Blanc, Vanoise, Ecrins) is 272 since the Little Ice Age maximal extent, including 180 since about 1970. However, it is important to note that each of these ice bodies does not necessarily correspond to a single initial entity (at the Little Ice Age maximum); as a glacier loses surface area, it can fragment into several smaller entities, which disappear over time. Therefore, counting the number of disappearing entities and establishing statistics on the basis of this count may give a biased view due to the fragmentation process. Statistics of glacierized surface area and its evolution over time remains a more robust source of information from a glacio-climatic point of view.

As more glaciers vanish from our warming world, tracking their disappearance, as we are doing in GLIMS, is crucial for understanding and illustrating the speed at which we are losing ice. The GLIMS Glacier Database already has outlines of the world’s glaciers from many dates, and registering the timing of glaciers’ extinction is an important new function. In the future we aim to record in GLIMS many more glaciers known to be extinct, and to enhance the download options so that a user can select only extinct glaciers. We actively solicit data on extinct glaciers from the whole glaciological community (Raup, Reference Raup2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Association ofCryospheric Sciences (IACS) for covering the publication costs of this paper. We thank the Scientific Editor Etienne Berthier and two anonymous reviewers for comments that improved the paper.