1. Introduction

Embodied cognition research emphasizes that mental simulation constitutes an internal mechanism in language processing, engaging modality-specific brain systems to reactivate memory-stored sensorimotor experiences (Bergen & Chang, Reference Bergen, Chang, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013). Within this broader framework, mental imagery refers to the conscious reconstruction of perceptual and motor experiences without external sensory stimuli (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou1999, Reference Barsalou2008). Most investigations of mental imagery have focused on first language (L1) processing, demonstrating both compatibility and interference effects, with inconsistencies often attributed to language abstractness and task demands (e.g., Hauf et al., Reference Hauf, Nieding and Seger2020; Liu & Bergen, Reference Liu and Bergen2016; Ostarek & Huettig, Reference Ostarek and Huettig2019).

In contrast, research on mental imagery in second language (L2) comprehension remains limited, with findings ranging from native-like to reduced or absent imagery effects (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Su and Wang2024; Shiang et al., Reference Shiang, Chern and Chen2024; Zeelenberg et al., Reference Zeelenberg, Pecher, van der Meijden, Trott and Bergen2025). A recent development in this area is Zhao et al.’s (Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025) simulation-based L2 comprehension model, which posits that crosslinguistic (dis)similarity, construction-specific semantic properties, learner-specific factors (e.g., proficiency, onset age of L2 learning and language dominance) and contextual factors (e.g., immersive environment, multimodal input) significantly influence L2 mental imagery effects. However, few studies have directly examined how construction-specific lexical-semantic properties affect L2 mental imagery or adopted a multidimensional view of learner variability.

The present study investigates the role of mental imagery in L1 and L2 speakers’ processing of English phrasal verbs (PVs), a linguistic construction characterized by polysemy and semantic complexity. It examines how differences between abstract and concrete PV meanings, as well as semantic transparency, affect L1 and L2 mental representations during incremental sentence processing. To capture the temporal dynamics of mental imagery, this study used a self-paced sensibility judgment task interleaved with schematic diagrams.

1.1. Mental imagery in L1 processing

Rooted in embodied cognition, mental imagery is a fundamental framework in cognitive linguistics (CL) that emphasizes the sensorimotor basis of language and cognition. This perspective assumes that language processing reactivates neural patterns formed by prior sensorimotor experiences, enabling comprehenders to mentally reconstruct sensory and motor representations to interpret language input (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou1999, Reference Barsalou2008). This mechanism allows comprehenders to visualize objects, simulate related actions and recall associated sensory modalities (e.g., vision, sound and smell) (Bergen & Chang, Reference Bergen, Chang, Östman and Fried2005).

Research on L1 mental imagery has predominantly examined perceptual and motor simulation using sentence–picture verification tasks (SPVTs), where participants determine whether a picture matches the implied meaning of a preceding sentence. These studies manipulate perceptual dimensions (e.g., orientation, shape, size, color) and motor features, with most findings revealing compatibility effects where congruent perceptual-sensory input enhances processing speed and accuracy (e.g., Hauf et al., Reference Hauf, Nieding and Seger2020; Norman & Peleg, Reference Norman and Peleg2022).

In contrast, some studies have reported interference effects, where language processing slows when paired with compatible images (Connell, Reference Connell2007; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Spivey, Barsalou and McRae2003). The underlying mechanism remains debated. One account attributes it to competition for shared cognitive resources, as simultaneous activation of perceptual-motor resources for language-related mental imagery and visual input may cause mutual inhibition and increased processing demands (Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Lindsay, Matlock and Narayanan2007). Others argue that certain perceptual properties, such as color, are inherently unstable and less conducive for simulation (Connell, Reference Connell2007).

Variability in findings may reflect differences in task design, the sensorimotor features manipulated and language abstractness. For instance, Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Spivey, Barsalou and McRae2003) found that both abstract and concrete language facilitated performance in a visual memory task but interfered performance in a visual discrimination task. These contrasting results have contributed to an ongoing debate about whether abstract concepts engage sensorimotor systems similarly to concrete concepts. While some studies report comparable simulation effects across abstract and concrete language (e.g., Guan et al., Reference Guan, Meng, Yao and Glenberg2013; Harpaintner et al., Reference Harpaintner, Sim, Trumpp, Ulrich and Kiefer2020), others argue that simulation is restricted to concrete language (e.g., Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Lindsay, Matlock and Narayanan2007; Bergen & Wheeler, Reference Bergen and Wheeler2010). Further evidence of this distinction comes from Liu and Bergen (Reference Liu and Bergen2016), who employed a sensibility judgment task to examine location–sentence compatibility effects. They found facilitation for concrete sentences (e.g., ‘Ben is feeding his child’) but interference for abstract sentences (e.g., ‘Calvin is submitting the request to the committee’). This pattern suggests that abstract language may involve distinct and more temporally extended simulation processes compared to concrete language, possibly due to weaker or more diffuse connections with sensorimotor experience.

1.2. L2 mental imagery: Mixed evidence and theoretical challenges

Despite extensive L1 research, evidence on L2 mental imagery remains limited and mixed. Some behavioral studies report native-like compatibility effects for features such as orientation, shape, color, motion and negation (e.g., Shiang et al., Reference Shiang, Chern and Chen2024; Zeelenberg et al., Reference Zeelenberg, Pecher, van der Meijden, Trott and Bergen2025), suggesting similar cognitive mechanisms for L1 and L2 mental simulation. Neuroimaging studies further indicate shared motor activation for both L1 and L2 processing (e.g., Birba et al., Reference Birba, Beltrán, Martorell Caro, Trevisan, Kogan, Sedeño, Ibáñez and García2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yang, Wang and Li2020), though L2 learners may recruit motor cortex more extensively to compensate for weaker linguistic representations (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Chen, Zhao, Wu, Zhang, De, Leppänen, Cong and Parviainen2020, Reference Tian, Chen, Heikkinen, Liu and Parviainen2023). Conversely, others report reduced or absent mental simulation effects in L2 processing, possibly due to weaker sensorimotor grounding and L1 dominance (e.g., Ahlberg et al., Reference Ahlberg, Bischoff, Kaup, Bryant and Strozyk2018; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Su and Wang2024; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Xie, Lu, Niu and Marmolejo-Ramos2024). These inconsistencies raise questions about the extent of L1–L2 divergence in mental representations and the factors shaping such variation.

Abstractness is a critical factor influencing L2 mental imagery, as abstract language comprehension tends to pose greater challenges for L2 learners than concrete language (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Peng and Li2023). However, evidence for sensorimotor activation during L2 abstract language processing is still sparse and inconclusive. Some studies report compatibility effects regardless of abstractness (Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2023; Yang, Reference Yang2016), while others report task-dependent interference effects influenced by conceptual abstraction (Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2024a, Reference Wang and Zhao2024b).

Considering abstractness as a continuum – ranging from literal (e.g., seize the arm), metaphorical (e.g., seize the chance) and abstract (e.g., cherish the chance) – Tian et al. (Reference Tian, Chen, Zhao, Wu, Zhang, De, Leppänen, Cong and Parviainen2020) found graded motor engagement (literal > metaphorical > abstract) in both L1 and L2 processing. The strongest motor activation for literal phrases likely reflects their direct connection with physical actions. However, Tian et al. (Reference Tian, Chen, Heikkinen, Liu and Parviainen2023) failed to replicate these effects, possibly due to methodological differences (fMRI passive reading vs. MEG semantic judgment). These inconsistencies suggest that abstractness effects on L2 simulation are both context-sensitive and task-dependent.

More importantly, L1 and L2 mental simulations related to abstractness differ significantly. Embodiment effects for abstract concepts appear to be language-dependent, with stronger effects in L1 than in L2 (Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2024a; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Yang, Oppenheim, Hu and Thierry2024). For instance, Chinese-English bilinguals process abstract senses of English prepositions more slowly than spatial senses, whereas native speakers show no such difference (Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2024a). This asymmetry may arise from weaker perceptual-motor associations in L2, impeding learners’ ability to intuitively construct L1–L2 constructional mappings (Dudschig et al., Reference Dudschig, De La Vega, De Filippis and Kaup2014).

To address these inconsistencies, Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025) proposed a simulation-based L2 comprehension model, which assumes that cognitive simulations grounded in real-world experiences underlie L2 comprehension, mirroring L1 processes. The model outlines three stages. In constructional analysis (Stage 1), learners identify constructions from L2 input and map L1 and L2 linguistic forms onto their corresponding meanings. L2 speakers’ ability to achieve native-like mental simulation is strongly influenced by their existing linguistic construction knowledge and indirectly shaped by individual learner differences. Both the complexity and frequency of the construction would affect learners’ simulation outcomes. In contextual resolution (Stage 2), discourse cues and world knowledge are integrated to construct a coherent semantic representation. In embodied simulation (Stage 3), this semantic representation engages sensorimotor systems, triggering perceptual-motor simulations that ground the linguistic input in embodied experiences.

The model further proposes that L2 mental simulation is modulated by linguistic knowledge (i.e., L1–L2 construction mapping), learner-specific factors (i.e., proficiency, onset age of L2 learning, language dominance) and contextual factors (i.e., world knowledge, communicative context). Variability in native-like to non-native-like perceptual-motor simulations may result from the interaction of these factors. Recent evidence shows that learner-specific and contextual factors collectively modulate the magnitude of L2 embodiment effects (e.g., Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2025; Nishide et al., Reference Nishide, Zhao and De Deyne2025).

Among these, L2 proficiency has received particular attention in relation to mental simulation, though findings are mixed – some report significant effects (Ahlberg et al., Reference Ahlberg, Bischoff, Kaup, Bryant and Strozyk2018; Nishide et al., Reference Nishide, Zhao and De Deyne2025), while others find no or minimal effects (Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2025; Zeelenberg et al., Reference Zeelenberg, Pecher, van der Meijden, Trott and Bergen2025). However, there is a paucity of research exploring other learner factors beyond proficiency. Lu and Yang (Reference Lu and Yang2025) found that earlier L2 age of acquisition (AoA) and greater exposure predicted stronger embodiment for English action verbs, whereas proficiency and dominance had no effect. Given the multidimensional nature of bilingual experience, learner factors alone cannot fully account for variability in L2 mental simulation. A comprehensive understanding of L2 embodiment requires examining the simulation-based model in relation to a broader range of variables, including proficiency, dominance, AoA and exposure.

Importantly, the L2 simulation model emphasizes the dynamic, temporally unfolding nature of L2 mental simulation, paralleling L1 simulation (Bergen & Chang, Reference Bergen, Chang, Östman and Fried2005, Reference Bergen, Chang, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013), yet the temporal dimensions of L2 simulation remain underexplored.

1.3. Temporal dynamics in mental imagery

Numerous studies have demonstrated simulation effects during L1 incremental sentence processing, but the precise timing of mental activation remains debated (Sato et al., Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013; Taylor & Zwaan, Reference Taylor and Zwaan2008; Zwaan & Taylor, Reference Zwaan and Taylor2006). Using a self-paced reading task with manual knob-turning, Zwaan and Taylor (Reference Zwaan and Taylor2006) found compatibility effects at the verb region but no effects at other regions (before/after the verb or sentence-final regions). Taylor and Zwaan (Reference Taylor and Zwaan2008) further showed that motor resonance was triggered by action-relevant elements (e.g., verbs, action-modifying adverbs like ‘quickly’), but not agent-modifying adverbs (e.g., happily). Complementing these findings, Sato et al. (Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013) found shape–sentence compatibility effects across preverbal, verb and postverbal regions, which were strongest when complete spatial information was available, typically at later stages of sentence processing. These findings indicate that comprehenders integrate linguistic cues incrementally, continuously updating mental representations as information unfolds (Pickering & Gambi, Reference Pickering and Gambi2018). These findings reinforce the dynamic and context-dependent nature of mental simulation.

While most studies on the timing of mental imagery focus on L1 speakers, fewer studies examine its temporal dynamics in L2 contexts. Nishide et al. (Reference Nishide, Zhao and De Deyne2025) applied a self-paced sentence–video verification task with Dutch and Japanese L2 English learners, reporting compatibility effects at both sentence-medial and sentence-final positions (e.g., The/ ball/ rolled/ under/ [video]/ the/ car vs. …under/ the/ car/ [video]), with stronger effects when the video appeared at the sentence-final position. Similarly, Wang and Zhao (Reference Wang and Zhaounder review) showed increasing compatibility effects as diagrams appeared later in sentences among Mandarin-English bilinguals. These findings suggest that L2 learners engage in simulation incrementally rather than postponing it until spatial information is complete and benefit from more robust integration of perceptual information at later stages. This aligns with previous L1 studies (e.g., Sato et al., Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013; Taylor & Zwaan, Reference Taylor and Zwaan2008) and supports the incremental nature of imagery, where L2 learners form and refine visual representations as spatial information unfolds.

Existing research has implied that earlier sentence segments may not provide sufficient information to trigger robust imagery effects for both L1 and L2 speakers. However, given the complex and dynamic nature of L2 simulation, more empirical evidence is needed to explore the temporal dynamics of mental representations in L2 processing, particularly considering L2 learners’ greater reliance on lexical-semantic cues in predictive processing (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Martin and Nieuwland2017).

1.4. The processing of English phrasal verbs

PVs are formulaic expressions combining a verb and a particle to form a single semantic unit, often marked by polysemy and idiomaticity. Their discontinuous structure, complex semantics and high polysemy encompassing both literal and abstract senses often pose challenges for L2 learners (Garnier & Schmitt, Reference Garnier and Schmitt2015).

In response, CL-inspired research has examined image schemas (Johnson, Reference Johnson1987) – fundamental cognitive structures (e.g., UP-DOWN, CONTAINER) derived from sensorimotor experiences – to support PV comprehension through spatial and metaphorical mappings (Mahpeykar & Tyler, Reference Mahpeykar and Tyler2015). Abstract senses often involve conceptual motion, where spatial and force dynamics are metaphorically mapped onto non-physical domains (Gibbs & Matlock, Reference Gibbs, Matlock and Gibbs2008). For example, the VERTICALITY schema explains look up both literally (as in physically looking upward) and figuratively (as in seeking information, metaphorically conceptualized as being stacked vertically). From an embodied cognition perspective, such abstract PVs may evoke simulation effects via activation of conceptual motion schemas (Bergen & Chang, Reference Bergen, Chang, Östman and Fried2005), even without physical motion. Schematic diagrams have been applied to visually represent spatiotemporal structures underlying image schemas and their corresponding linguistic expressions (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Huang, Zhou and Wang2020).

CL-inspired experimental studies have shown that image-schema-based instruction enhances L2 PV learning outcomes (e.g., Hwang, Reference Hwang2023; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Ogura and Burden2022). However, far fewer studies have investigated mental imagery in PV comprehension, particularly incorporating schematic diagrams. In a self-paced sensibility judgment task, Yang (Reference Yang2016) found semantically aligned diagrams (e.g., an ‘up’ diagram paired with the particle ‘up’) facilitating processing of both concrete and abstract PVs in L1 speakers. However, the validity of these compatibility effects is questioned by the study’s use of only four two-dimensional diagrams (lines and arrows) that likely fail to capture PVs’ semantic nuances, and the lack of norming procedures to verify PV–diagram alignment.

Additionally, Lindstromberg (Reference Lindstromberg2022) proposed that PVs vary along two semantic continua: from literal (i.e., concrete) to figurative (i.e., abstract) meanings, and from semantically compositional to non-compositional structures. Among these, semantic transparency – the extent to which a PV’s meaning can be inferred from its components – is a key internal feature, reflecting a graded spectrum of compositionality (Zhao & Le, Reference Zhao, Le, Ortega, Tyler, Park and Uno2016).

Empirical research shows that both L1 and L2 speakers are sensitive to semantic transparency, with literal PVs (e.g., cover up) generally perceived as more transparent than opaque ones (e.g., chew out), though this perception varies across items and individuals (Blais & Gonnerman, Reference Blais and Gonnerman2013). Transparent PVs, which retain clearer links between their components and overall meaning, have been shown to facilitate L2 comprehension (Zhao & Le, Reference Zhao, Le, Ortega, Tyler, Park and Uno2016) and elicit robust priming effects in lexical judgment tasks (e.g., cover up | cover). These findings suggest that transparency enhances access to compositional meaning by reducing the inferential burden during processing. From the mental imagery perspective, this more direct form–meaning mapping may better support the activation of perceptual representations during real-time comprehension. Within the L2 simulation-based model (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025), such effects likely emerge during the constructional analysis stage, where semantic transparency supports the retrieval of schematic structure and eases the activation of embodied representations. This underscores the need to move beyond categorical distinctions between abstract and concrete PVs and to examine how gradient semantic transparency shapes mental imagery in L2 learners’ processing.

1.5. The present study

Despite the extensive research on L1 mental imagery, L2 mental simulation, particularly in PV processing, remains largely underexplored and contested, with mixed evidence regarding the extent of embodiment. The simulation-based L2 comprehension model (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025) proposes that cognitive simulations grounded in real-world experiences operate similarly in L1 and L2 comprehension, while emphasizing the iterative and dynamic nature of L2 mental imagery shaped by linguistic and learner-specific factors. However, the impact of lexical-semantic properties of target constructions (i.e., PVs) and multidimensional learner factors on the dynamic formation of mental imagery has yet to be thoroughly examined.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating how schematic visual cues influence sentence-level comprehension of English PVs in L1 and L2 speakers. We used a self-paced sensibility judgment task interleaved with image-schematic diagrams to track incremental sentence processing. Schematic diagrams were chosen instead of realistic pictures because they can depict both concrete and abstract PV meanings with consistent spatial schemas (Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2024a); abstract PV senses (e.g., pick up the melody) are not easily or reliably illustrated with concrete images. This design provides fine-grained reaction time (RT) measures of online comprehension and allows real-time assessment of mental imagery effects. These are advantages that alternative tasks such as post hoc sensibility judgment or simple SPVT cannot offer (cf. Sato et al., Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013; Yang, Reference Yang2016). The schematic diagrams representing the literal or metaphorical motion implied by the PV were presented either immediately after the PV or after the sentence-final word to probe the temporal dynamics of mental imagery. PVs vary in semantic transparency across concrete and abstract senses, allowing us to examine how the lexical-semantic property and conceptual abstraction modulate mental imagery effects.

The following research questions guide the study:

-

(1) Does diagram congruency facilitate sensibility judgments during incremental sentence processing of concrete and abstract PVs, and does this effect differ between L1 and L2 speakers?

-

(2) How does the lexical-semantic property of PVs (i.e., semantic transparency) affect participants’ sensitivity to diagram congruency in sentence comprehension?

-

(3) How do individual learner differences, including L2 proficiency, AoA, L2 exposure and language dominance, influence L2 learners’ sensitivity to diagram congruency in sensibility judgments?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

Fifty-six adult native English speakers (28 males, 27 females, 1 non-binary; mean age = 43.49, SD = 6.63) participated in the main experiment. They were recruited via Prolific and reported being right-handed with no literacy-related difficulties. All participants reported English as their mother tongue and were born and residing in the United Kingdom (n = 19), the United States (n = 33) or Canada (n = 4).

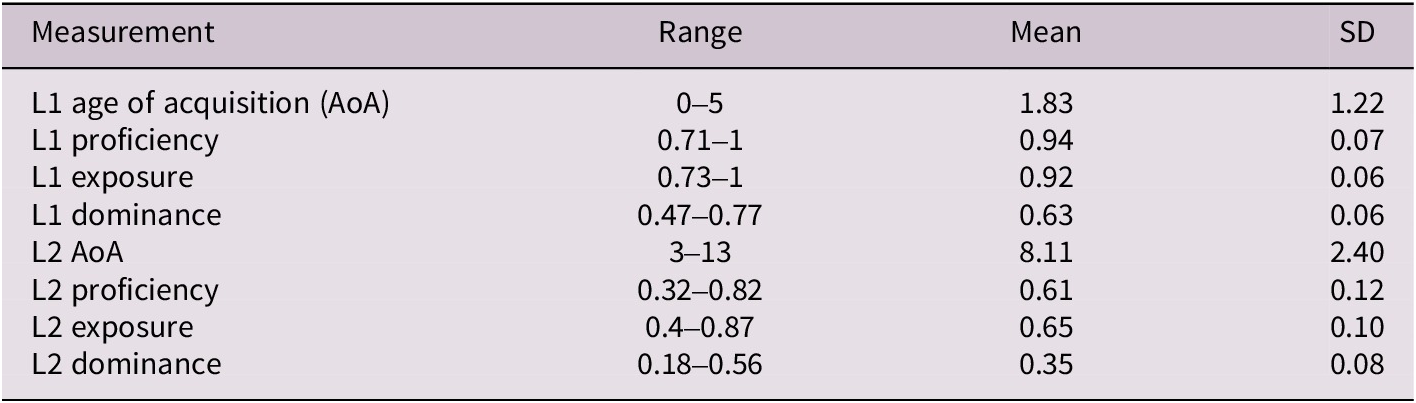

Sixty-three adult Chinese learners of L2 English (12 males, 51 females; mean age = 22.3, SD = 1.62) were recruited via Rednote, a Chinese social networking platform. L2 participants’ English proficiency was indexed by their College English Test Band 4 (CET-4) scores, a nationally administered, large-scale standardized test and one of the most influential high-stakes English proficiency assessments in China (Zheng & Cheng, Reference Zheng and Cheng2008). The test comprises four sections, including listening, reading, cloze/error correction and writing/translation, with a maximum score of 710. All L2 participants were college students in China, with an average CET-4 score of 538.11 (SD = 61.64), corresponding approximately to the B1–B2 range on the CEFR scale. Participants completed the Language History Questionnaire (LHQ3.0, Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Yu and Zhao2020). Following Li et al.’s (Reference Li, Zhang, Yu and Zhao2020) computing methods, Table 1 summarizes learner-related variables, including proficiency, exposure, dominance (standardized to a 0–1 scale) and self-reported AoA, which were all treated as continuous variables.

Table 1. Language background of L2 participants

2.2. Design and materials

This study adopts a 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 (PV–diagram congruency × PV abstractness × sentence sensibility × temporal sequences) factorial design. PV–diagram congruency and PV abstractness (concrete vs. abstract senses) are categorical within-subject variables. Sequence (diagram presented after the PV vs. after the sentence) is a between-subject variable. PV semantic transparency is treated as a continuous within-subject variable. The experimental stimuli comprised 40 sentence pairs constructed from 20 PVs (Garnier & Schmitt, Reference Garnier and Schmitt2015), each used in both concrete and abstract senses, with sensible and nonsensical versions. Nonsensical sentences were syntactically well formed but semantically implausible, typically created by pairing PVs with incongruous or contextually inappropriate objects and adjuncts. All sentences were used in the simple past tense and active voice.

Table 2 shows sample sentence stimuli using ‘hand over’ and ‘take down’ in four conditions with corresponding diagrams. To reduce predictability and maintain task engagement, grammatical filler sentences (adapted from Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Loewen, Elder, Reinders, Erlam and Philp2009) with varied structures and plausibility were included. Full materials (PVs, sentence stimuli and fillers) are available in Supplementary Material 1, which details the strict multistep criteria used to select target PVs and reports their string frequency and collocational strength (Mutual Information, Church & Hanks, Reference Church and Hanks1990).

Table 2. Sample diagrams, senses and test sentences

2.2.1. Visual stimuli

Viewing verb–particle combinations as unified constructions, diagrams were designed and organized according to the spatial motion patterns underlying the selected PVs (see Supplementary Material 1 for selection rationale). Because many target PVs share a particle (e.g., out, down, off) and therefore a common image schema (OUT, DOWN, SEPARATION), several PVs draw on the same diagram, for instance, PVs instantiating the DOWN schema (lay down, take down, put down) and those instantiating the OUT schema (lay out, give out, throw out, bring out, send out). This overlap reflects the theoretical assumption that particle meaning is schematic and construction-based.

Accordingly, 13 schematic diagrams (Appendix A) were created to illustrate the literal and metaphorical motion configurations implied by the 20 target PVs. Within each diagram, dotted and solid lines distinguished prior and subsequent motion, and arrows indicated directionality. To ensure consistency, a small ball depicted the moving object, and a rectangle represented the CONTAINMENT schema. Body effectors (e.g., a hand or arm) were included only when needed to clarify the motion trajectories, and tools (e.g., a shovel for break off) were shown only when an external force was essential to convey the intended motion. Diagrams were primarily black-and-white line drawings, with limited accents of red, yellow and gray to enhance the perceptual salience of motion trajectories.

Seven additional filler diagrams (Supplementary Material 1) were included to illustrate semantic configurations of four modal verbs (must, may, will, would) (adapted from Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Mueller and Ho2010) and three tense variations (simple present, past and future). Each diagram was presented in either a congruent condition, visually matching the PV’s conceptual motion, or an incongruent condition, visually conflicting with the PV’s meaning. For incongruent trials, the diagram accompanying the sentence was randomly selected from either non-matching target diagrams or filler diagrams, which effectively minimized the likelihood that the specific diagram features would bias participants’ judgments.

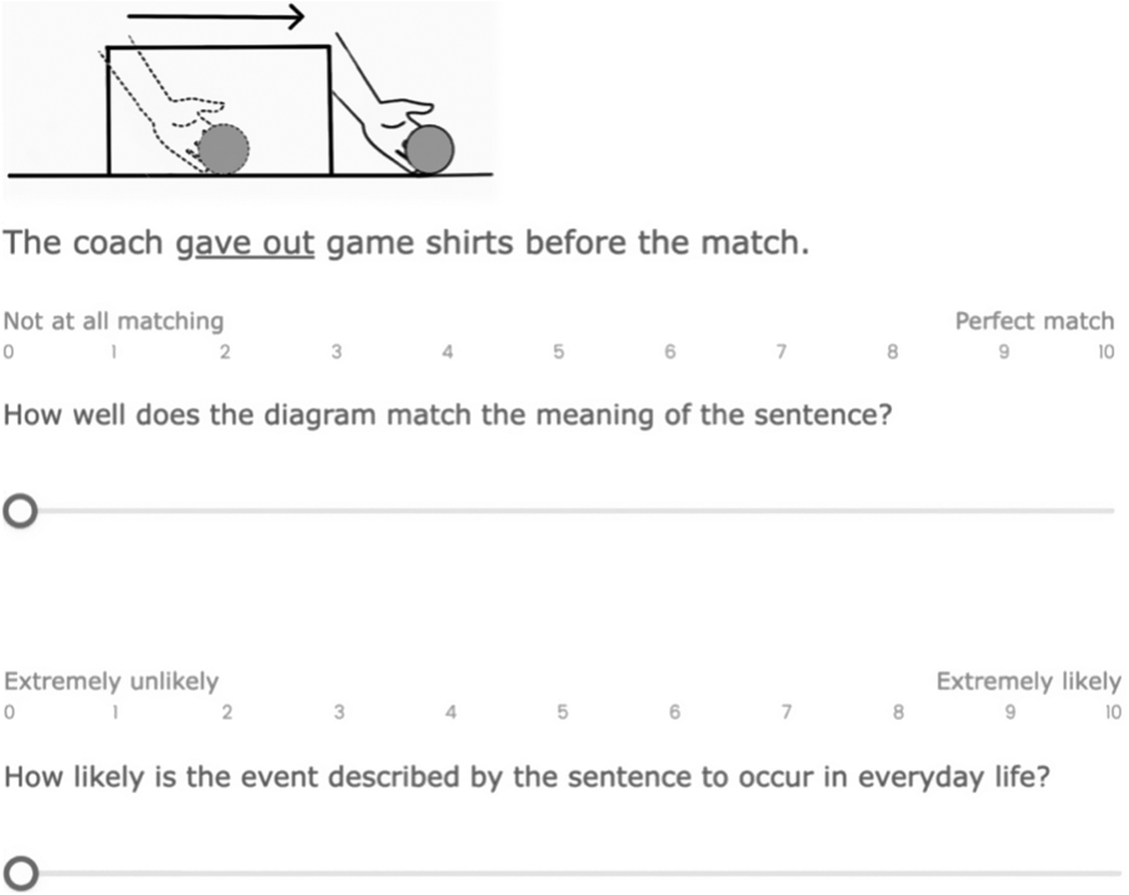

2.2.2. Norming study

A norming study was conducted online using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, 2025), including a sentence–diagram matching task and an event plausibility rating task. Twenty-two monolingual English speakers (11 males, 11 females; mean age = 42.73, SD = 14.78) were recruited via Prolific. Only sensible sentence stimuli were used in the norming study. To ensure enough critical stimuli and minimize plausibility bias, 20 PVs were initially used to generate 80 items (40 pairs crossing concrete/abstract senses), divided into two blocks of 40 sentences. Each participant completed one block, rating sentence–diagram compatibility (0 = not at all matching, 10 = perfect match) and event plausibility (0 = extremely unlikely, 10 = extremely likely) on ten-point Likert scales. Trials were randomized with no time limits or feedback. Figure 1 presents a sample trial.

Figure 1. A sample trial in the norming study.

Based on mixed-effects modeling results, the study retained 40 high-quality sentence stimuli that are (i) well matched to their diagrams (M concrete = 7.11, SD = 2.78; M abstract = 6.69, SD = 2.97), with no significant difference across abstractness (β = 0.45, SE = 0.32, t = 1.42, 95 % CI [−0.19, 1.09], p = 0.17); (ii) highly plausible (M concrete = 7.64, SD = 2.53; M abstract = 7.21, SD = 2.55), with comparable plausibility ratings for concrete and abstract items (β = 0.43, SE = 0.22, t = 1.95, 95 % CI [−0.02, 0.87], p = 0.06); and (iii) evenly distributed over concrete and abstract categories. A sensitivity analysis in G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009) (t tests, difference between two dependent means, two-tailed, α = 0.05, N = 22) indicated 80% power to detect a minimum effect of dz = 0.63. These results confirm that the final stimuli set is both semantically plausible and visually congruent, supporting its validity for use in the subsequent experimental task.

2.2.3. Sensibility judgment task

The main experiment used a self-paced sensibility judgment task interleaved with diagram presentation, involving two blocks: diagrams appeared either after the PV or after the sentence-final word. Following Sato et al. (Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013), each trial began with a central fixation cross, followed by a moving-window paradigm where participants pressed the spacebar to reveal sentence segments sequentially, each replacing the previous one to its right. Upon diagram presentation, participants made a diagram verification judgment to indicate whether the diagram matched the sentence meaning, allowing assessment of imagery accuracy. After completing each sentence reading, the full sentence reappeared for a sensibility judgment (‘J’ = sensible, ‘F’ = nonsensical) within 10,000 ms. For sensible sentences, a comprehension question followed, displayed until response. Accuracy was recorded for both sensibility judgments and comprehension responses. Participants completed seven practice trials with feedback before the formal task. Figure 2 illustrates a sample trial and two diagram presentation sequences.

Figure 2. (a) Sample trial in sequence 1. (b) Sample trial in sequence 2.

2.2.4. Diagram familiarization

Before the sensibility judgment task, a diagram familiarization task was implemented to support participants’ interpretation of abstract schematic diagrams. Thirteen animated GIFs were presented alongside their corresponding PV diagrams to strengthen intuitive form–meaning mappings and minimize visual ambiguity. Participants were required to review all pairings before proceeding the sensibility judgment task. Figure 3 displays a sample diagram familiarization phase, with schematic diagrams on the left and motion animations on the right.

Figure 3. Example display from diagram familiarization task.

2.2.5. Semantic transparency rating task

Following the sensibility judgment task, all participants undertook an offline semantic transparency rating task. Materials were identical to the main task, with the target PVs underlined. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of two rating blocks containing 20 sentences balanced for concrete and abstract items. Participants rated PV transparency on a 0–10 Likert scale, indicating how easily each PV’s meaning could be inferred from its verb and particle. Item-level transparency ratings were averaged and included as a continuous within-subject variable in the analysis.

2.3. Procedure

A digital informed consent form and a plain language statement were provided to participants prior to participation. The experiment began with a diagram familiarization phase using 13 animated GIFs, followed by the main self-paced sensibility judgment task implemented via PsyToolkit (version 3.6.2; Stoet, Reference Stoet2010, Reference Stoet2017). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two blocks: Sequence 1 (33 L1 and 31 L2 speakers), with the diagram presented after the PV, or Sequence 2 (23 L1 and 32 L2 speakers), with the diagram presented after the sentence. Within each block, participants were randomly assigned to one of eight counterbalanced lists, each containing 55 sentences (40 critical items and 15 fillers). After the main task, participants completed the PV transparency rating task via Qualtrics and the LHQ (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Yu and Zhao2020). The entire session lasted approximately 20 minutes for L1 participants and 30 minutes for L2 participants.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Mental imagery effects were calculated as the RT difference between congruent and incongruent PV–diagram pairs. Data were analyzed in R software (version 4.5.0; R Core Team, 2025), using linear mixed-effects models with the lme4 (version 1.1.37; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2025) and lmerTest (version 3.1.3; Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2020) packages. Only correct sensibility judgments with RTs (200–8000 ms) were included and log-transformed. Trials falling outside this conventional range (< 200 ms or > 8000 ms) for online self-paced sentence tasks and sensibility judgments were excluded as implausible responses, eliminating 2.68% of data overall (L1 = 1.56%; L2 = 3.69%). Exclusion rates were low and did not interact with congruency. Categorical variables (congruency, abstractness, sequence, sensibility) were treatment-coded.

The final models addressing RQ1 were fitted separately for L1 and L2 groupsFootnote 1, including fixed effects of congruency, abstractness, sequence, sensibility and their interactions, with random intercepts for participants and items. For RQ2, models for each group included fixed effects of congruency and its interaction with covariates, including PVs’ transparency, string frequency, collocational frequency, event plausibility and diagram–PV matching ratings. For RQ3, models tested each L2 learner factor (proficiency, AoA, dominance, exposure) interacting with congruency and sensibility. Random intercepts and participant-level slopes for congruency were retained when justified.

Fixed effects were evaluated using type III ANOVA with Satterthwaite’s approximation for degrees of freedom and p values (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). Post hoc comparisons were conducted with emmeans (version 1.11.1; Lenth et al., Reference Lenth, Banfai, Bolker, Buerkner, Giné-Vázquez, Herve, Jung, Love, Miguez, Piaskowski, Riebl and Singmann2025) and visualizations generated via ggplot2 (version 3.5.2; Wickham et al., Reference Wickham, Chang, Henry, Pedersen, Takahashi, Wilke, Woo, Yutani, Dunnington and Van Den Brand2025). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) followed Plonsky and Oswald’s (Reference Plonsky and Oswald2014) interpretation: small (0.60), medium (1.00), large (1.40) for within-subjects comparisons; small (0.40), medium (0.70), large (1.00) for between-subjects comparisons. Full model formulas and outputs are reported in Supplementary Material 2.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics of reaction times and accuracy rates

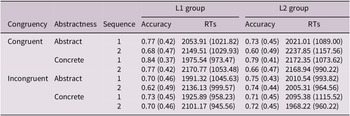

Tables 3 and 4 present descriptive statistics for diagram verification and sensibility judgments across nativeness, abstractness, sequence and congruency conditions. The diagram verification served primarily as a manipulation check to confirm that participants attended to the diagrams and understood their intended mappings. In this procedure, L1 and L2 participants spent approximately 2000 ms to verify the diagram. Importantly, mean verification accuracy for both groups exceeded 70%, which is significantly above chance level and consistent with previous sentence–diagram verification studies (e.g., Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2024a, Reference Wang and Zhao2024b). However, no robust sentence–diagram compatibility effect emerged in the verification procedure. Accordingly, we interpret the verification as confirming adequate attention to and comprehension of the diagrams, but not as providing a reliable index of imagery-based compatibilityFootnote 2.

Table 3. Diagram verification: Accuracy and response times by congruency × abstractness × sequence (L1 vs. L2)

Table 4. Sensibility judgments: Accuracy and response times by congruency × abstractness × sequence (L1 vs. L2)

For sensibility judgments, RTs of correct responses and accuracy rates were presented. Both groups responded faster in congruent trials. L2 learners showed higher accuracy in congruent trials compared to incongruent ones, whereas L1 speakers demonstrated similar accuracy across conditions. Overall, L1 speakers made faster and more accurate judgments than L2 learners. Additionally, both groups achieved high comprehension accuracy (L1: M = 0.86, SD = 0.34; L2: M = 0.80, SD = 0.40), confirming adequate task engagement and semantic understanding. Given the timed nature of the task, RTs serve as the primary dependent variable for assessing processing dynamics. Figure 4 provides violin plots depicting RTs and accuracy rates in diagram verification and sensibility judgment tasks, highlighting performance differences across language groups (L1 vs. L2) and congruency conditions. Furthermore, since accuracy rates were well above chance level and did not exhibit strong variability across congruency conditions, subsequent inferential analyses focus on RTs of correct responses to capture subtle processing differences.

Figure 4. Violin plots of reaction times and accuracy rates in diagram verification and sensibility judgment tasks.

3.2. Congruency facilitation effects on L1 and L2 sensibility judgments

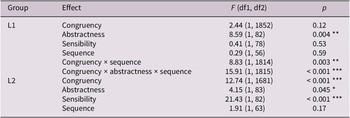

Two linear mixed-effects models were performed to analyze the effects of congruency, sensibility, abstractness, sequence and their interactions on sensibility judgment RTs for L1 and L2 groups. Table 5 summarizes the ANOVA results for the L1 and L2 groups. In the L1 modelFootnote 3, results showed significant fixed effects of abstractness, with abstract PVs eliciting slower responses than concrete PVs (β abstract-concrete = 0.19, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.059, 0.327], t = 2.868, p = 0.005; Cohen’s d = 0.40, SE = 0.141, 95% CI [0.127, 0.678], corresponding to a small effect). Also, there is a significant two-way interaction between congruency and sequence. Pairwise comparisons showed that the congruency facilitation effect emerged only in Sequence 2 (see Figure 5): participants responded 199 ms significantly faster to the congruent trials (M = 1801, SE = 130, 95% CI [1559, 2081]) than incongruent trials (M = 2000, SE = 145, 95% CI [1731, 2311]; t = −2.90, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.46, SE = 0.16, 95% CI [−0.76, −0.15], indicating a small compatibility effect). No significant congruency difference was observed in Sequence 1 (p = 0.267).

Table 5. Summary of ANOVA results of congruency, abstractness, sensibility and sequence for L1 and L2 groups

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 5. L1 and L2 reaction times across congruency, abstractness and sequences.

Additionally, the L1 modelFootnote 3 yielded a significant three-way interaction between congruency, abstractness and sequence. Post hoc tests revealed that the congruency facilitation effect occurred only for concrete PVs in both Sequence 1 (t = 5.7, p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.49, SE = 0.17, 95% CI [0.15, 0.83], indicating a small effect) and Sequence 2 (t = −8.47, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.91, SE = 0.22, 95% CI [−1.34, −0.48], indicating a medium to large effect). No significant congruency effects were found for abstract PVs (ps > 0.23).

In the L2 modelFootnote 4, significant main effects were found for congruency, abstractness and sensibility, but not for sequence. Post hoc analyses indicated that L2 learners judged 250 ms faster on congruent trials (M = 2302, SE = 104, 95% CI [2105, 2518]) than incongruent trials (M = 2552, SE = 116, 95% CI [2331, 2792]; t = −3.56, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.33, SE = 0.092, 95% CI [−0.505, −0.146], indicating a very small effect). For the significant effect of abstractness, L2 learners judged 205 ms slower for abstract PVs (M = 2528, SE = 122, 95% CI [2298, 2782]) than concrete PVs (M = 2323, SE = 111, 95% CI [2114, 2553]; t = 1.99, p = 0.049, Cohen’s d = 0.27, SE = 0.134, 95% CI [0.004, 0.53], corresponding to a very small effect). For the sensibility effects, post hoc results revealed that mean RTs in sensible sentences (M = 2203, SE = 103, 95% CI [2009, 2416]) were 464 ms shorter than in nonsensical sentences (M = 2667, SE = 131, 95% CI [2420, 2939]; t = −4.53, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 0.61, SE = 0.134, 95% CI [−0.867, −0.342], indicating a small to medium effect). No significant two-way or three-way interactions were found.

3.3. Lexical-semantic properties

According to the linear modelFootnote 5 for the L1 group, there were significant effects of PV string frequency and L1 transparency ratings. Table 6 presents a summary of lexical property effects for L1 and L2 groups. Follow-up post hoc analyses showed that higher string frequency (β = −0.043, SE = 0.015, t = −2.86, p = 0.004) and greater transparency (β = −0.033, SE = 0.016, t = −2.14, p = 0.032) were associated with shorter RTs. As illustrated in Figure 6, the modelFootnote 5 yielded a significant interaction between congruency and PV transparency. Higher transparency predicted significantly faster RTs in incongruent trials (β = −0.075, SE = 0.023, t = −3.32, p = 0.001), but no significant effects in congruent trials (t = 0.32, p = 0.75). An interaction between plausibility and congruency approached significance, with higher plausibility predicting faster RTs in congruent trials (β = −0.064, SE = 0.031, t = −2.04, p = 0.042), but not in incongruent trials (p = 0.694).

Table 6. Summary of ANOVA results for effects of lexical properties in L1 and L2 groups

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 6. Interaction of congruency with PV transparency and event plausibility.

In the modelFootnote 6 investigating the effect of lexical properties in the L2 group, results showed significant main effects of event plausibility ratings, PV–diagram matching ratings and collocational frequency. Post hoc analyses revealed that higher-rated plausible sentences were marginally associated with faster RTs (β = −0.08, SE = 0.04, t = −2.00, p = 0.052). Similarly, there was a marginal trend indicating that L2 learners responded faster to sentences with higher PVs’ collocational frequency (β = −0.02, SE = 0.01, t = −2.00, p = 0.052). Additionally, higher PV–diagram matching ratings predicted significantly faster RTs (β = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t = −2.07, p = 0.04). However, no significant interactions between lexical properties and congruency were found in the modelFootnote 6.

3.4. Individual difference factors

Table 7 provides a summary of ANOVA results examining bilingual experience effects. In the modelFootnote 7 concerning L2 proficiency, results showed a significant main effect of L2 proficiency and a three-way interaction between congruency, sensibility and proficiency. Follow-up analyses showed that higher L2 proficiency led to faster RTs (β = −0.661, SE = 0.312, t = −2.117, p = 0.038). Moreover, post hoc analyses of the three-way interaction indicated that high-proficiency learners responded significantly faster in incongruent-sensible trials (β = −1.14, SE = 0.36, t = −3.16, p = 0.002), but not in congruent-sensible trials (β = −1.14, p = 0.38). For nonsensical sentences, a significant proficiency effect was observed only in congruent trials (β = −1.06, SE = 0.39, t = −2.73, p = 0.007), indicating that higher proficiency was associated with faster responses. However, the effect was absent in incongruent-nonsensical trials (β = −0.12, p = 0.79).

Table 7. Summary of ANOVA results for effects of learner differences

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

In the modelFootnote 8 examining L2 dominance, results showed a significant main effect of L2 dominance, with higher L2 dominance predicting faster sensibility judgments (β = −1.01, SE = 0.5, t = −2.017, p = 0.048). Additionally, a significant three-way interaction emerged among dominance, congruency and sensibility. Pairwise comparisons revealed that greater L2 dominance led to significantly faster responses to incongruent-sensible sentences (β = −1.69, SE = 0.58, t = 2.9, p = 0.005). In contrast, for nonsensical sentences, higher dominance facilitated faster responses only in congruent trials (β = −1.52, SE = 0.65, t = −2.34, p = 0.019), with no significant effect in incongruent-nonsensical trials. Figure 7 presents the interaction effects between both learner-internal factors and congruency. The modelFootnote 9 concerning L2 AoA revealed no significant main effects or interaction effects.

Figure 7. Interaction effects between learner-internal factors and congruency.

In the modelFootnote 10 examining L2 exposure, no significant main effect of exposure itself was found. However, a significant interaction between L2 exposure and congruency emerged. Post hoc comparisons revealed no significant RT differences between congruent and incongruent conditions across L2 exposure levels (ps > 0.27).

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: L1–L2 mental imagery effects

Both L1 and L2 speakers showed facilitation when a schematic diagram matched the PV during the sensibility judgment procedure, echoing earlier motion-imagery research (e.g., Dudschig et al., Reference Dudschig, De La Vega, De Filippis and Kaup2014; Hauf et al., Reference Hauf, Nieding and Seger2020; Tomczak & Ewert, Reference Tomczak and Ewert2015), but our L1–L2 patterns differed markedly. L1 speakers showed facilitation only for concrete PVs and only when the diagram appeared after the sentence, whereas L2 speakers showed robust congruency effects across PV types and diagram presentation sequences. For L1 speakers, these findings are consistent with the recruitment of spatial-path imagery during sensibility-based judgment: mental representations of movement trajectories and spatial configurations implied by the verb–particle combination. Facilitation emerged only when diagrams followed the full sentence (Sequence 2), indicating that L1 comprehenders tend to first construct a complete semantic representation before integrating visual-spatial cues as confirmatory input. Presenting the diagram mid-sentence may interrupt or interfere with ongoing sentence integration, thereby reducing imagery-based facilitation. This sequence-sensitive pattern accords with prior work showing that full sentential context supports more robust simulation (e.g., Nishide et al., Reference Nishide, Zhao and De Deyne2025; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013).

The selective effect for concrete PVs aligns with embodied cognition literature, where spatial mental imagery is selectively recruited for spatially grounded expressions but less consistently for abstract language (Bergen & Chang, Reference Bergen, Chang, Östman and Fried2005; Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Lindsay, Matlock and Narayanan2007; Bergen & Wheeler, Reference Bergen and Wheeler2010). Importantly, the present effects differ from the motor-effector simulations reported in studies of action-verb processing, where participants reenact specific bodily movements (e.g., De Grauwe et al., Reference De Grauwe, Willems, Rueschemeyer, Lemhöfer and Schriefers2014; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Marmolejo-Ramos and Pei2015). Whereas those investigations targeted verbs like kick or grasp and documented activation in motor and sensorimotor brain areas, our schematic-diagram paradigm probed PVs whose concrete senses primarily encode spatial change-of-location (e.g., throw out, take down). The selective facilitation we observed thus reflects imagery of spatial configurations, not detailed motor-action reenactment. The absence of facilitation for abstract PVs further supports claims that abstract language evokes weaker or more temporally extended simulation processes requiring greater contextual integration (Liu & Bergen, Reference Liu and Bergen2016).

L2 learners, by contrast, showed generalized congruency effects for both concrete and abstract PVs and across diagram presentation sequences. This broader reliance on diagram congruency suggests task-constrained imagery that is more strongly anchored in external visual cues. This finding likely reflects reduced automaticity and weaker lexical-semantic entrenchment in L2 (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025), prompting learners to recruit visual input to support meaning construction within the demands of the sensibility judgment task. Comparable compensatory recruitment of sensorimotor resources during L2 comprehension has been observed in neuroimaging research: Tian et al. (Reference Tian, Chen, Zhao, Wu, Zhang, De, Leppänen, Cong and Parviainen2020) reported greater motor cortex activation during L2 processing, while Tian et al. (Reference Tian, Chen, Heikkinen, Liu and Parviainen2023) found that language-related regions (e.g., insular gyri, superior temporal gyrus) were more active in L1 during early semantic processing (~300–500 ms), whereas L2 processing showed stronger motor activation (central sulcus) at a later stage (~600–800 ms). They attributed the increased motor activity during L2 processing to learners’ compensatory recruitment of sensorimotor regions, arising from less efficient or incomplete activation of traditional language processing networks and reduced processing automaticity. The present finding that L2 speakers relied broadly on diagram congruency echoes this interpretation: in the context of sensibility judgment, the schematic diagrams, regardless of whether the accompanying PVs expressed a concrete or an abstract meaning or of when the diagram appeared, served as external visual-spatial scaffolding that L2 learners recruited to support task-driven imagery formation, complementing their less entrenched lexical-semantic representations.

4.2. RQ2: Lexical-semantic cue weighting in L1 and L2 imagery

Greater semantic transparency of PVs led to faster sensibility judgment in diagram-incongruent trials, suggesting that transparent PVs offer more decomposable form–function mappings and evoke more accessible mental imagery, which helped L1 speakers to detect incongruence efficiently. Within Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025) simulation-based L2 comprehension model, this transparency advantage reflects more effective Stage 1 constructional analysis, which supports downstream embodied representation at Stage 3. This result aligns with embodied and usage-based models of language processing (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2008; Zwaan, Reference Zwaan2008), which propose that meaning comprehension involves simulating sensorimotor and conceptual content. The ability to resolve conflict through lexical-semantic information also supports accounts of flexible cue integration in L1 processing (Altmann & Mirković, Reference Altmann and Mirković2009; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney, Kroll and de Groot2005; Trueswell & Tanenhaus, Reference Trueswell, Tanenhaus, Clifton, Frazier and Rayner1994), whereby comprehenders adaptively weigh lexical, structural or contextual cues depending on the reliability of available information.

In contrast, higher plausibility ratings predicted faster sensibility judgment only in congruent trials, suggesting that L1 speakers draw more heavily on Stage 2 contextual integration when visual and verbal information align. Together, these findings demonstrate L1 speakers’ flexible strategy adaptation based on visual-verbal congruency: prioritizing semantic plausibility when inputs align and reverting to lexical-semantic cues like PV transparency under conflict. This adaptability supports theories of adaptive simulation and predictive processing (Kuperberg & Jaeger, Reference Kuperberg and Jaeger2016; Pickering & Gambi, Reference Pickering and Gambi2018), where cue use is guided by input coherence and task demands.

L2 learners presented a different profile. They showed a strong diagram-congruency effect across all conditions, independent of PV transparency, PV–diagram matching ratings, event plausibility or collocational frequency. Their lack of sensitivity to transparency – a lexical property important for Stage 1 constructional processing – suggests difficulty in accurately identifying and mapping L2 PV constructions, especially given the lack of direct L1-Chinese equivalents. This finding echoes Tiv et al. (Reference Tiv, Gonnerman, Whitford, Friesen, Jared and Titone2019), who observed that real-time L2 sentence reading was largely unaffected by transparency, probably because learners depend on surface-level compositional strategies and underdeveloped lexicalized representations. In contrast, Blais and Gonnerman (Reference Blais and Gonnerman2013) found transparency effects in L2 decontextualized tasks such as semantic-similarity ratings and lexical priming (finish up – finish), tasks that tapped shallow lexical access with minimal contextual load, whereas our sentence-level comprehension task required deeper integration of visual and verbal information.

Similarly, the absence of any plausibility-by-congruency interaction suggests weaker Stage 2 contextual integration in L2 processing, likely due to limited discourse exposure or underdeveloped world knowledge. This constraint may hinder L2 learners’ ability to construct coherent mental models that integrate linguistic and situational information, especially for semantically complex expressions like PVs. Their strong but unmodulated diagram congruency effect suggests that L2 representations in this task were largely perceptually anchored: external diagrams trigger representation building, while internal lexical-semantic and contextual integrations remain limited. This interpretation aligns with the simulation-based model’s proposal that native-like Stage 3 embodied representations depend on robust constructional and contextual processing at earlier stages, which may be underdeveloped for many L2 learners.

Altogether, these findings show that in sensibility judgment, L1 speakers flexibly integrate lexical-semantic and contextual cues, drawing on PV transparency when visual and verbal inputs conflict. L2 learners rely consistently on diagram congruency and exhibit weaker integration of semantic and contextual information – a pattern that aligns with bilingual embodiment research reporting weaker or more variable sensorimotor activation in L2 processing (e.g., Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2025; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Yang, Oppenheim, Hu and Thierry2024; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Xie, Lu, Niu and Marmolejo-Ramos2024).

4.3. RQ3: Influence of learner-specific and contextual factors

L2 proficiency and language dominance enhanced learners’ sensitivity to diagram incongruency, enabling faster sensibility judgments when visual and verbal information conflicted. Learners with higher proficiency or greater dominance integrated lexical-semantic and perceptual cues more efficiently under these demanding conditions, but this advantage disappeared in congruent trials where visual-verbal alignment already supported comprehension. Thus, while proficiency and dominance aid conflict resolution, their influence diminishes when inputs are fully coherent.

Overall, these findings align with prior research (e.g., Birba et al., Reference Birba, Beltrán, Martorell Caro, Trevisan, Kogan, Sedeño, Ibáñez and García2020; Nishide et al., Reference Nishide, Zhao and De Deyne2025), showing that higher L2 proficiency supports sensorimotor embodiment and efficient integration of linguistic knowledge with embodied mental models (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025). L2 proficiency, therefore, not only shapes linguistic and executive functioning but also modulates sensorimotor grounding (Kogan et al., Reference Kogan, Muñoz, Ibáñez and García2020), explaining the observed proficiency-driven imagery effects. Greater L2 dominance, reflecting broader language usage, similarly fosters grounded representations that aid comprehension. However, no facilitation emerged for nonsensical sentences with incongruent diagrams, indicating that proficiency and dominance offer limited compensatory benefits under high semantic-perceptual conflict.

No significant effects of L2 AoA on mental imagery were found, possibly due to limited variability in our sample, as most participants were sequential bilinguals who began learning English around age eight. Although earlier AoA is typically linked to stronger L2 embodiment (Lu & Yang, Reference Lu and Yang2025; Norman & Peleg, Reference Norman and Peleg2022), our results indicate that sensorimotor recruitment in L2 processing may not be strictly age-dependent, with certain lexicosemantic domains engaging embodied networks irrespective of acquisition timing.

Additionally, L2 exposure did not predict learners’ sensitivity to diagram congruency, diverging from Lu and Yang (Reference Lu and Yang2025), who found both L2 exposure and AoA predictive of embodiment effects for action verbs. This discrepancy may reflect differences in focused constructions: action verbs are closely linked to sensorimotor experience, whereas interpreting semantically complex PVs may depend more on linguistic competence than on exposure alone. The null exposure effect may also reflect measurement limitations. According to Stage 2 of Zhao et al.’s (Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025) simulation-based model, successful contextual integration requires immersive, multimodal L2 discourse engagement. While the LHQ offers standardized exposure metrics, it may overlook the depth, quality or context-sensitive nature of L2 engagement. Moreover, although our controlled PV set ensured experimental consistency, its limited scope may constrain ecological validity. Incorporating more diverse, contextually rich PVs could enhance generalizability.

4.4. Future studies

L2 learners in this study showed pronounced dependence on external visual support, suggesting that the self-paced sensibility judgment task interleaved with schematic diagrams may impose substantial cognitive demands on lower-intermediate learners. Our L2 sample primarily comprised learners at lower-intermediate proficiency (B1–B2 on the CEFR) and did not span the full proficiency continuum. Accordingly, these findings may not extend to higher-proficiency learners, who may engage mental imagery in a more native-like manner when processing L2 input. Prior research indicates that higher L2 proficiency is associated with more advanced, native-like embodiment (Ahlberg et al., Reference Ahlberg, Bischoff, Kaup, Bryant and Strozyk2018; Nishide et al., Reference Nishide, Zhao and De Deyne2025), likely reflecting richer lexical-semantic knowledge and more successful functional restructuring of form–function mappings that supports the development of L2-specific processing strategies (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Vanek and MacWhinney2025). Future studies should therefore recruit learners across a broader proficiency range and with varied ages of onset to test whether advanced or earlier-acquiring learners rely less on external visual support and show more native-like effects of diagram congruency.

Additionally, while our schematic diagrams were normed for PV–diagram congruency, subtle differences in visual details, such as the presence of tools, body effectors (e.g., a hand or arm) or other manipulable objects, may have provided varying degrees of visual affordance. Neuroimaging research shows that visually salient, action-related features can engage motor-related cortical regions (e.g., Buccino et al., Reference Buccino, Binkofski, Fink, Fadiga, Fogassi, Gallese, Seitz, Zilles, Rizzolatti and Freund2001; Grèzes et al., Reference Grèzes, Tucker, Armony, Ellis and Passingham2003), suggesting that such features may influence how comprehenders integrate visual information when forming task-based mental imagery. In the present study, these variations did not produce systematic effects on sensibility judgment outcomes: the same set of schematic diagrams was used across concrete and abstract senses, and incongruent trials always paired sentences with non-matching diagrams or filler diagrams, reducing the likelihood that specific visual features could drive the observed compatibility patterns. Even so, because schematic diagrams necessarily simplify spatial relations and vary in their perceptual specificity, future research may benefit from further reducing diagrammatic variability or employing complementary temporal methods (e.g., eye-tracking, EEG) to more precisely trace how visual characteristics modulate imagery-based processing within sensibility judgment paradigms.

5. Conclusion

Overall, this study found that L2 learners’ imagery-based simulation was not dynamically modulated by lexical-semantic or contextual factors, reflecting a broad reliance on external visual support. In contrast, L1 speakers strategically engaged visual cues, guided by their internalized semantic knowledge. Crucially, L2 imagery effects were shaped by L2 proficiency and dominance, whereas AoA and exposure showed no significant impact. These findings support the simulation-based model of L2 comprehension, suggesting that mental imagery reflects the gradual restructuring of conceptual and linguistic associations as they unfold in a visual-verbal integration context. Pedagogically, image-schematic diagrams representing spatiotemporal or metaphorical structures may facilitate learners’ form–meaning mappings and promote deeper conceptual integration for complex expressions like PVs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2026.10062.

Data availability statement

The supplementary materials and anonymized data are accessible from https://osf.io/qsfbn/?view_only=de18db648d0f4910839e5b20a2173827.

Appendix A. Target Phrasal Verbs and Corresponding Schematic Diagrams