Introduction

In moments of culture-contact, diet and material culture are fundamental elements of identity-making. In early-medieval Europe (c. AD 400–1100), the significance of fish to the Scandinavian diet (relative to other parts of northern and western Europe) is frequently remarked upon, and the appearance of individuals with marine-heavy diets in Viking Age Britain (c. AD 793–1066) has been taken as an indicator of ‘viking’ migration (e.g. Barrett & Richards Reference Barrett and Richards2004; Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Ditchfield, Piva, Wallis, Falys and Ford2012; Buckberry et al. Reference Buckberry2014; Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Grimes, Buckberry, Evans, Richards and Barrett2014). Furthermore, from c. AD 1000, faunal data from England indicate an increase in the consumption of marine fish, related to a rapid intensification of deep-sea fishing and an associated trade in stored fish. This phenomenon has become known as the Fish Event Horizon (e.g. Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Locker and Roberts2004; Barrett Reference Barrett, Gerrard and Gutiérrez2018). Concurrently, variation in culinary material culture is apparent, with ceramics more widely used for cooking in first millennium England than in Scandinavia.

However, much of our understanding of the role of marine products in Viking Age diet has emerged not from pottery, but from fish remains and the isotopic analysis of human remains. Against this backdrop, we demonstrate how lipid analysis of ceramic cooking vessels can enhance our understanding of Viking Age fish processing. We consider the degree to which the practice was spatially and chronologically variable, and what happened when a group of ichthyophagic migrants settled in new communities and encountered complex ceramic repertoires. Were fish—perhaps previously grilled, smoked, baked or stewed in steatite/metal vessels—now incorporated into dishes that used these new ceramic technologies? In this context of conflict, migration and settlement, we explore the role played by cooking technologies in cultural accommodation.

Fish, pots and cooking in Scandinavia

Faunal remains and isotopic analyses of human bones demonstrate that fish was consumed in quantity in Scandinavia and many of its Viking Age colonies. Key contributors to fishbone assemblages include members of the cod (Gadidae) and herring (Clupeidae) families (e.g. Enghoff Reference Enghoff1999: 52–3; Perdikaris Reference Perdikaris1999; Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Nicholson and Cerón-Carrasco1999; Wigh Reference Wigh2001: tab. 6), although quantitative comparison is frequently confounded by differential taphonomy, recovery and species visibility (e.g. Jones in O’Connor Reference O’Connor1989: 197).

In Norway, zooarchaeological analyses indicate that gadid exploitation pre-dates the Viking Age (Perdikaris Reference Perdikaris1999; Perdikaris et al. Reference Perdikaris, Hambrecht, Brewington, McGovern and Plogmann2007), with increases in the representation of marine species in the eighth/ninth century interpreted in relation to the growing importance of fishing (e.g. Naumann et al. Reference Naumann, Price and Richards2014; Garnier & Vedeler Reference Garnier and Vedeler2021). In Sweden and the Baltic, although difficult to quantify (Craig et al. Reference Craig, Bondioli, Fattore, Higham and Hedges2013), isotopic evidence suggests that diet was less dominated by marine foods (e.g. Kosiba et al. Reference Kosiba, Tykot and Carlsson2007; Olsson & Isaksson Reference Olsson and Isaksson2008; Kjellström et al. Reference Kjellström, Storå, Possnert and Linderholm2009), and elevated marine intake may have been status related (Linderholm et al. Reference Linderholm, Jonson, Svensk and Lidén2008). In southern Scandinavia—traditionally viewed as an important area of origin for the settlement of England—the picture is complex. Viking Age populations in Aarhus (Jutland) and Galgedil (Funen) seem to have been reliant on meat from terrestrial animals, though their diets also included a range of freshwater and marine resources; at Galgedil there was greater isotopic variation in males than in females (Price et al. Reference Price, Prangsgaard, Kanstrup, Bennike and Frei2014; Swenson Reference Swenson2019).

Culinary technologies in Viking Age Norway were aceramic, with vessels manufactured from soapstone (Hansen & Storemyr Reference Hansen and Storemyr2017). Chemical investigations into the uses of cooking equipment have been limited, though marine residues were recently detected in medieval vessels and bakestones (Garnier & Vedeler Reference Garnier and Vedeler2021; Wickler Reference Wickler2024). Sweden’s ceramic culture during this period incorporated local traditions and Slavic introductions (Roslund Reference Roslund2007), and chemical analyses suggest significant diversity in diet, with residues at some sites depleted in marine products relative to human-bone isotopes (e.g. Olsson & Isaksson Reference Olsson and Isaksson2008; Isaksson Reference Isaksson2009, Reference Isaksson2010). In Denmark, locally produced pottery was largely hand-thrown and bonfire-fired (Madsen Reference Madsen, Mortensen and Rasmussen1991: 232–34). Prior to this study, few analyses of organic residues from vessels found in Viking Age contexts from Denmark had been undertaken (though see Madsen & Sindbæk Reference Madsen, Sindbæk, Roesdahl, Sindbæk, Pedersen and Wilson2014: 216).

Fish, pots and cooking in Anglo-Saxon and Viking Age England

In England, ichthyological remains suggest a low baseline of fish consumption prior to c. AD 1000 (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Locker and Roberts2004), followed by an increase in the exploitation of marine relative to freshwater fish (e.g. York; O’Connor Reference O’Connor1989: 196; Harland et al. Reference Harland, Jones, Orton, Barrett, Barrett and Orton2016). Outside of urban centres, fish remains from Anglo-Saxon and Viking Age contexts are rare, even in sieved assemblages (Dobney et al. Reference Dobney, Jacques, Barrett and Johnstone2007: 228–31).

Studies of the human-bone isotope record from Viking Age contexts in Atlantic Scotland (e.g. Barrett & Richards Reference Barrett and Richards2004; Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Grimes, Buckberry, Evans, Richards and Barrett2014) have identified elevated marine intake comparable to that seen in parts of Norway (e.g. Naumann et al. Reference Naumann, Price and Richards2014). To date, there is little evidence for a similar elevation in pre-Viking or Viking Age England (e.g. Buckberry et al. Reference Buckberry2014; Barrett Reference Barrett, Gerrard and Gutiérrez2018), and documentary sources suggest that fish consumption may have had status associations long before the Norman Conquest in 1066 (e.g. Fleming Reference Fleming2001: 5–6). In this context, the arrival of migrants steeped in maritime economy should be discernible (e.g. Jarman et al. Reference Jarman, Biddle, Higham and Bronk Ramsey2018; Leggett & Lambert Reference Leggett and Lambert2022: 28).

However, we know little about fish processing in early-medieval England, or whether cooking technologies changed under the influence of Scandinavian settlement. While some regions were effectively aceramic in the Middle Saxon period (c. AD 650–793), the seventh century saw the establishment of a significant pottery industry at Ipswich, with other regional industries following over the next century or so (Mainman Reference Mainman, Ashby and Sindbæk2020: 65). By the ninth century, the areas of northern and eastern England into which Scandinavians settled were characterised by widespread use of ceramics.

A new approach

There is a need to understand the role played by marine resources in Anglo-Scandinavian cuisine, as patterning in exploitation may contribute substantially to the study of culture contact. Hybridity and acculturation are recognised in diverse sources—from artefacts and burial customs to linguistics and law—complicating the identification of individuals who migrated from Scandinavia to Viking Age England (e.g. Hadley & Richards Reference Hadley and Richards2000).

Here, we exploit a new line of evidence—the use of domestic cooking pots—to explore potential changes in diet at high resolution. Pottery use reflects culinary choices and may tell us how past communities valued different foodstuffs. Determining the use of domestic containers through residue analysis is an archaeologically well-established method; lipid biomarkers associated with aquatic processing are well described and frequently identified in prehistoric vessels (Cramp & Evershed Reference Cramp, Evershed, Holland and Turekian2014; Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021). In a recent study of pottery use in the island communities of Atlantic Scotland, Norse period (c. AD 1100–1300) pots at Jarlshof, Shetland showed evidence of use in the intensive processing of marine products, while at Bornais, South Uist, the proportion of pots containing aquatic biomarkers did not increase substantially between the Iron Age (c. AD 400–800) and Norse (c. AD 900–1400) periods (Cramp et al. Reference Cramp2014). However, the island communities from which these samples were drawn are unlikely to be representative of other parts of Britain.

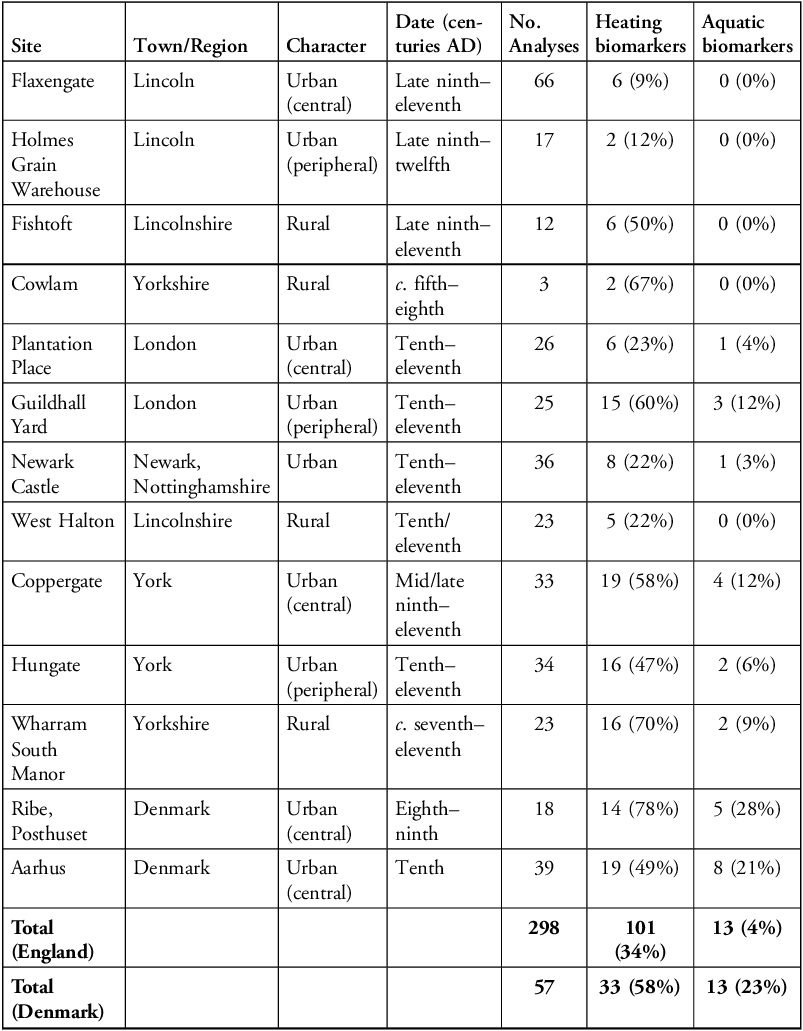

We expand this approach to a much larger sample of pottery from diverse urban and rural contexts, across ninth- to eleventh-century England (n = 298, Table S1), including sites both within and beyond the area traditionally seen as the focus of Scandinavian settlement (Figure 1). Sites were selected for their secure stratigraphy and ceramic sequences, and provide a transect across the northern Danelaw (Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire) together with a comparative sample from later Anglo-Saxon London. In each urban centre (York, Lincoln and London), we sampled from two sites—one central to the settlement and one more peripheral—to discern any intra-settlement variation. These data are compared with data from previously published Anglo-Saxon pottery and newly analysed samples from the Danish urban centres of Aarhus (n = 39) and Ribe (n = 18).

Figure 1. Map of sites included in the study. Surveyed urban sites (large red circles): 1) York (Coppergate; Hungate); 2) Lincoln (Flaxengate; Holmes Grain Warehouse); 3) London (Guildhall Yard; Plantation Place). Surveyed rural sites (small white circles): 4) Wharram (South Manor); 5) West Halton; 6) Newark Castle; 7) Fishtoft (White House Lane). Published comparator sites (green diamonds): 8) Flixborough (Colonese et al. Reference Colonese2017); 9) Oxford (multiple city centre sites; Craig-Atkins et al. Reference Craig-Atkins2020); 10) West Cotton, Northamptonshire (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Chapman, Blinkhorn and Evershed2020). The ‘Danelaw’ boundary of the Alfred-Guthrum Treaty is provided as a point of reference regarding the extent of Scandinavian settlement echoed in the distribution of Old Norse placenames; it should not be assumed that this constituted a formal border (figure by authors).

Materials and methods

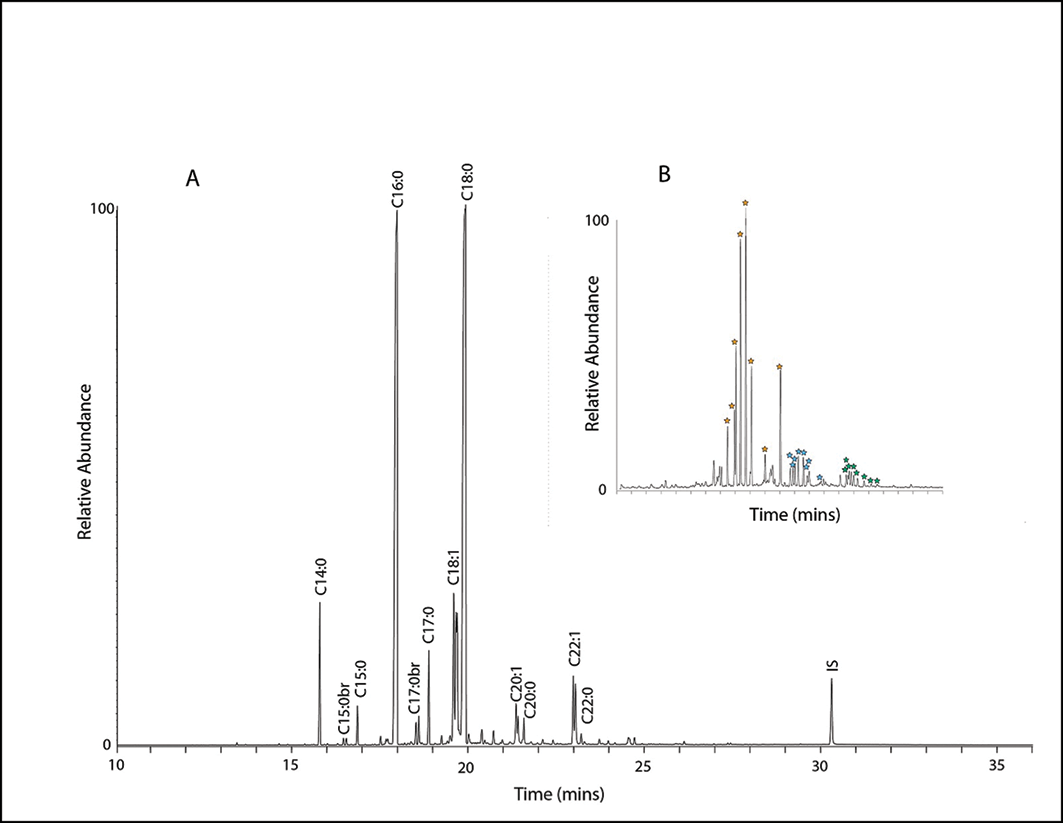

Examined vessels include jars (potentially including domestic cooking pots and storage jars) (n = 212), bowls (n = 86), pitchers (n = 14) and unspecified categories (n = 43), and incorporate diverse regional wares and fabrics (Table S1). We deployed an approach that incorporates two independent lines of evidence for the identification of aquatic animal resources, taken here to include fish, aquatic molluscs and aquatic mammals, in the analysis of powdered ceramic samples (details in online supplementary material (OSM)). First, we measured the carbon isotope values (δ13C) of individual saturated fatty acids (n-alkanoic acids) with 16 and 18 carbon atoms (C16:0; C18:0) released from the pots during extraction, and compared these with reference marine and freshwater fish oils (the former are expected to be enriched in 13C, while the latter are depleted in 13C; Cramp & Evershed Reference Cramp, Evershed, Holland and Turekian2014). As C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acids are routinely identified in archaeological pottery, this means of differentiation has the advantage of being applicable to a wide range of material. However, when aquatic products are mixed with other resources—either sequentially or concurrently—the resulting δ13C values are often more difficult to interpret. A second approach largely circumvents this issue by using the presence/absence of biomarkers for aquatic oils, including vicinal dihydroxy acids, isoprenoid fatty acids and ω-(o-alkylphenyl) alkanoic acids (APAAs; Cramp & Evershed Reference Cramp, Evershed, Holland and Turekian2014). We focused on the latter two criteria. APAAs are readily formed during protracted heating of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), which are abundant in fish oils, providing unequivocal evidence of fish processing (Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021). We define the presence of aquatic-derived oils according to the following criteria: the presence of either C20 and C22 APAAs and at least one isoprenoid fatty acid (Cramp & Evershed Reference Cramp, Evershed, Holland and Turekian2014); or C20 APAAs in a ratio of C18/C20 APAA <0.06 and at least one isoprenoid fatty acid (Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021).

Results and discussion

Most of the analysed pots produced lipid profiles dominated by saturated mid-chain-length fatty acids typical of animal fats. Of 355 samples, 270 provided sufficient quantities of C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acids for GC-c-IRMS (gas chromatography-combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometry) analysis. Occasionally, lipid profiles potentially derived from degraded plant waxes and oils were identified as additional components, but further elucidation of these compounds using high-temperature gas chromatography mass spectrometry is required, and will be reported separately. The presence/absence of these compounds does not affect our ability to identify aquatic-derived products.

A dataset from the carbon-isotope analysis of C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acids was assembled to include the new measurements reported here, and those previously reported from Anglo-Saxon contexts at Flixborough (Lincolnshire), West Cotton (Northamptonshire) and Oxford (Colonese et al. Reference Colonese2017; Craig-Atkins et al. Reference Craig-Atkins2020; Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Chapman, Blinkhorn and Evershed2020). Few of the analysed samples provided fatty-acid values that plot within the ranges of modern marine or freshwater fish oils (Figure 2). There are no discernible differences in values between sites situated in northern England (where Scandinavian placenames are numerous) and those in ostensibly Anglo-Saxon London. Considering the δ13C value of the C16:0 saturated fatty acid—the dominant fatty acid in aquatic oils and therefore the one least affected by mixing—only two vessels (Coppergate – CP27, Newark – New32) produced values within the expected marine range (i.e. <−25‰), and only three vessels (Newark – New25, London – PL25, PL 26) produced values within the anticipated range for freshwater organisms (>−31‰), although the latter also overlaps the δ13C16:0 for C3 plants (Drieu et al. Reference Drieu, Lucquin, Cassard, Sorin, Craig, Binder and Regert2021). For comparison, over 60 per cent of Norse (medieval) ceramic vessels analysed from Jarlshof, Shetland, had C16:0 values within the marine range (Cramp et al. Reference Cramp, Whelton, Sharples, Mulville and Evershed2015). Instead, the isotope data reported here overwhelmingly reflect mixtures of terrestrial animal fats, with nearly all samples plotting in the space between ruminant dairy (e.g. milk/yoghurts/butter), ruminant carcass fats (e.g. sheep/goat/cattle/deer) and non-ruminant carcass fats (e.g. pig/poultry). This is consistent with previous studies of Anglo-Saxon pottery (Colonese et al. Reference Colonese2017; Craig-Atkins et al. Reference Craig-Atkins2020; Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Chapman, Blinkhorn and Evershed2020). Mixtures involving ruminant animals and (particularly) dairy fats tend to result in more negative Δ13C values (defined by δ13C18:0 minus δ13C16:0). Dairy fats were slightly more prevalent at rural sites and, overall, the distribution of Δ13C values was significantly different between rural and urban sites, with the former having more negative values (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 10.464, df = 1, p-value = 0.001217).

Figure 2. Plot of stable carbon isotope values (δ13C) of C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acids extracted from early-medieval potsherds from England and Denmark, compared by context. The data are plotted against reference ellipses (67% confidence) derived from 315 measurements of authentic reference products, corrected for the addition of post-industrial carbon (figure by authors).

Even if the majority of lipids were derived from terrestrial animal sources, aquatic-derived lipids (biomarkers) may still be present, reflecting a minor contribution of freshwater or marine foods to the residue. For example, in tenth- to fourteenth-century phases at the Norse settlements of Bornais and Cille Pheadair (Western Isles, Scotland), around 20 per cent of vessels contained long-chain APAAs with at least 20 carbon atoms (C20AAPAA or C22-APAAs), despite having C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acid values largely indicative of ruminant fats (Cramp et al. Reference Cramp2014). The evidence from Viking Age England provides a stark contrast. From the total dataset (n = 298), only two samples—from a context at Guildhall Yard, London, dated to after c. AD 1050 (GHY 12, 22)—contained appreciable amounts of long-chain C20- and C22-APAAs (Figure 3), and only a further 11 samples contain C20APAAs and isoprenoid fatty acids, meeting the less stringent criteria for aquatic lipid identification (after Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021). Overall, only 4.4 per cent of vessels from England contained evidence of aquatic products: 3.5 per cent in Viking Age vessels and 7.1 per cent in pre-Viking vessels.

Figure 3. A) Partial gas chromatogram of an acid-methanol extract from Guildhall Yard, London (GHY12_200) showing principal fatty acids most likely derived from a mixture of terrestrial animal fats and aquatic oils; B) Partial ion chromatogram (m/z 105) showing a rare example of long-chain APAAs detected in GHY12_200, derived from heating aquatic oils (orange stars: C18APAAs; blue stars: C20APAAs; green stars: C22APAAs) (figure by authors).

Shorter chain C18-APAAs were present at relatively high abundance in 34 per cent of samples (Table 1) from all the sites in England, suggesting there was nothing to preclude the formation of APAAs in pottery from this period. While the C18 homologues are always found at higher concentrations than C20-APAAs in heated aquatic oils—typically five times greater (Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021)—the general lack of C20-APAAs in most samples suggests that, rather than an artefact of proportion, the C18-APAAs were more likely formed during the heating of shorter chain (C18:x) polyunsaturated fatty acids present in terrestrial plant and animal tissues (Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021), which is consistent with their isomeric distribution. In most samples, the ratio of E/H isomers of the C18-APAAs (Table S1) is consistent with leafy plants rather than cereals, although lower values can also be produced through prolonged heating (Bondetti et al. Reference Bondetti2021). The presence of C18-APAAs is also frequently observed (58%) in vessels from Aarhus and Ribe (Table 1), where, in contrast to the evidence from England, around 23 per cent of the vessels analysed contained aquatic-derived residues.

Table 1. Frequencies of heating and aquatic biomarkers inferred from presence of APAAs extracted from early-medieval potsherds from England and Denmark.

Heating biomarkers are defined by the detection of C18-APAAs, while aquatic biomarkers additionally have appreciable amounts of C20-APAA. Many of the sites are multiperiod; to ensure samples were taken from well-dated material, we targeted well-dated wares, focused on illustrated examples that preserved diagnostic morphology and, wherever possible, sampled sherds from sealed, well-dated contexts. See Table S1 for details.

The paucity of aquatic lipids in vessels from England is remarkably consistent. Our sampling strategy incorporated jars of various sizes, pitchers and bowls, incorporating vessels manufactured in more than 15 fabric types (including widely distributed wares and local, short-lived varieties). We sampled material dated to the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries; from northern, central and southern England; from rural settlements such as Wharram, and from peripheral and centrally located sites in the towns of York, Lincoln and London. None of these parameters was associated with any significant difference in the detection of aquatic lipids in pottery (Table 1), which appears to be independent of chronology, settlement character and geography.

Vikings, fish and the ceramic revolution

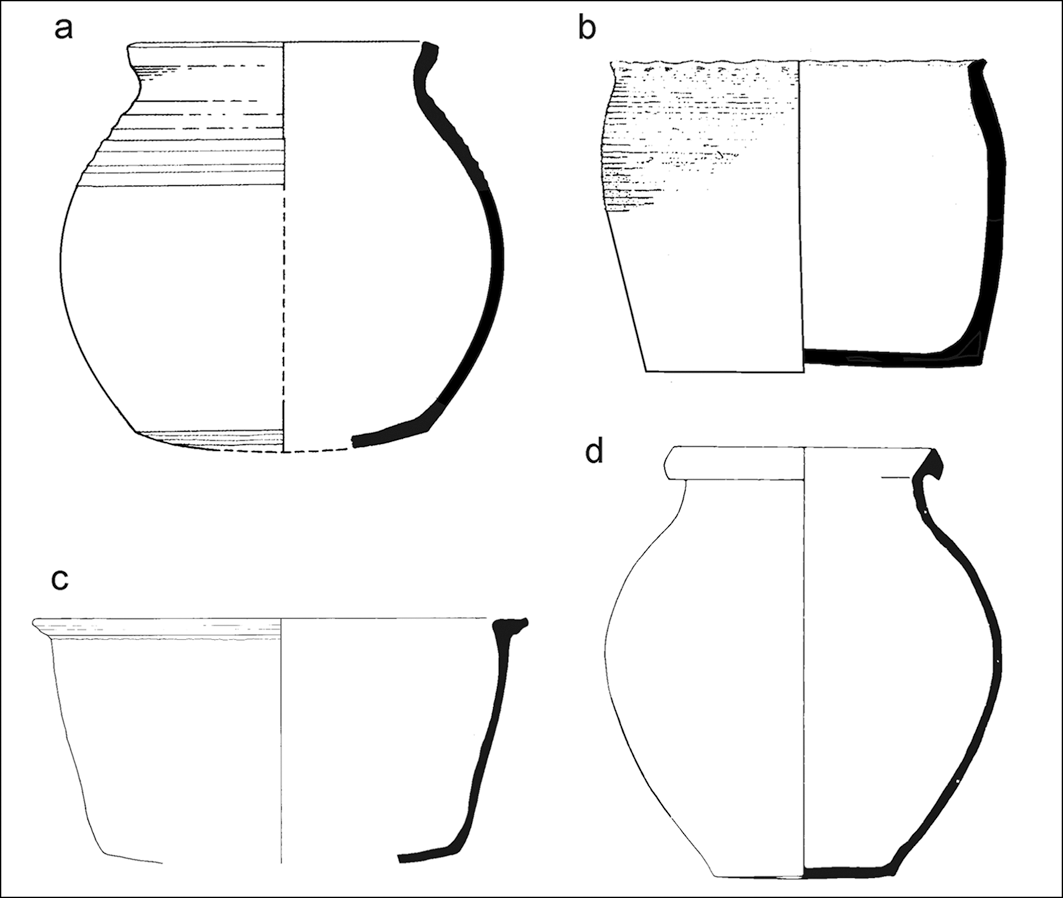

Late-ninth-century England saw a ceramic revolution (Figure 4), with the introduction of a range of high-fired, wheel-turned vessels of standardised form in the wake of the Viking Great Army’s campaigns (e.g. Hurst Reference Hurst and Small1965; Kilmurry Reference Kilmurry1977; Mainman Reference Mainman1990, Reference Mainman, Ashby and Sindbæk2020; Perry Reference Perry2016, Reference Perry2026). Yet, the appearance of this new ceramic repertoire does not seem to have had a discernible impact on the inclusion/exclusion of fish products from the vessels (Figure 2). Neither vessels of these new forms nor their Anglo-Saxon precursors contain an appreciable number of aquatic-derived residues (Table S1; Colonese et al. Reference Colonese2017). This also appears to be true of ceramics in central and southern England, where evidence for Scandinavian settlement is less pronounced (e.g. Craig-Atkins et al. Reference Craig-Atkins2020; Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Chapman, Blinkhorn and Evershed2019, Reference Dunne, Chapman, Blinkhorn and Evershed2020). The data from Aarhus/Ribe are consistent with aristocratic sites in Sweden, which do preserve evidence for the use of ceramic vessels in fish processing, though this evidence is under-represented relative to expectations based on isotopic analyses of human bone (Olsson & Isaksson Reference Olsson and Isaksson2008). Few comparative data are available from Viking Age Norway, where organic residue analysis studies have been rare (Wickler Reference Wickler2024: 176), but the differences between results from England and Denmark—typically seen as the homeland of many of England’s Viking Age settlers—are notable.

Figure 4. Middle Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Scandinavian pottery forms: a) Ipswich Ware jar; b) Maxey Ware jar; c) Torksey Ware bowl; d) Stamford Ware jar (drawings by G. Perry, after: a) Blinkhorn Reference Blinkhorn2012: fig. 12; b) Addyman et al. Reference Addyman, Fennell and Biek1964: fig. 14; c) Hadley et al. Reference Hadley, Richards, Craig-Atkins and Perry2023: fig. 12; d) Kilmurry Reference Kilmurry1980: fig. 7, not to scale).

Fish (including marine species, at a low level) are present in zooarchaeological assemblages from Viking Age towns in England, so this discrepancy between pottery use and faunal data could relate, in part, to the cooking of meats in socially prescribed ways. It is possible that the consumption of fish was an aristocratic privilege as early as the Viking Age (e.g. Fleming Reference Fleming2001: 5–6); at Birka, for example, male individuals buried with weapons tended to have more marine-rich diets (Linderholm et al. Reference Linderholm, Jonson, Svensk and Lidén2008), and there is evidence that a restricted number of individuals, possibly elites, had access to marine diets in early Viking Age Orkney (Barrett & Richards Reference Barrett and Richards2004). In Viking Age England, too, we might postulate a division between terrestrial meats and greens, which were commonly available and routinely stewed in pots, and fish, whose availability was more restricted and which may have been fried, grilled, baked or eaten raw, smoked or salted.

Indeed, there is some evidence that fish was cooked using non-ceramic technologies. Old English texts reference the broiling of fish (e.g. Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld1900: March 27), though the equipment used in this form of cooking is poorly represented in Viking Age collections. Aristocratic grave goods such as the Oseberg cauldron hint at metallic cooking wares as part of the repertoire (Petersen Reference Petersen1951: 369, 409; see also Graham-Campbell Reference Graham-Campbell1980: 15–20), and soapstone vessels were also important, but lipid extraction from this material has proven difficult (see Garnier & Vedeler Reference Garnier and Vedeler2021; Wickler Reference Wickler2024).

In England, soapstone vessels are present in early Viking Age settlement phases, and are best interpreted as possessions brought with the first wave of migrants (Sindbæk Reference Sindbæk, Barrett and Gibbon2015). Metal vessels are rare and often fragmentary, though examples are demonstrable, such as the large pan from Coppergate, York (Ottaway Reference Ottaway1992: 604–605; Figure 5). Osteoarchaeological evidence for fish-processing is similarly scarce. Transverse chopmarks on cod and salmon caudal vertebrae from late seventh- to early ninth-century phases at Flixborough may suggest the cutting of fish into steaks (Dobney et al. Reference Dobney, Jacques, Barrett and Johnstone2007: 109). Other assemblages lack cut-marks or any selective patterning in body part representation (e.g. Flaxengate, Lincoln; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson and O’Connor1982), though butchery evidence from medieval York may indicate the sagittal splitting and filleting of cod (Harland et al. Reference Harland, Jones, Orton, Barrett, Barrett and Orton2016: 194–96). More direct evidence for cooking is perhaps visible in the low-level burning of bones (e.g. Harland et al. Reference Harland, Jones, Orton, Barrett, Barrett and Orton2016: 176–77), though this might equally reflect disposal methods. A survey of fish remains from Anglo-Saxon and Viking Age sites in England provides little further data.

Figure 5. A tenth-century iron pan from excavations at 16–24 Coppergate, York (photograph by York Archaeological Trust, CC BY-NC 4.0).

The eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry shows a variety of food being cooked on spits and braziers, as well as the use of a large cauldron, but fish are only depicted whole, at Bishop Odo’s table (Figure 6). While this scene is probably an allusion to the biblical Last Supper (Gameson Reference Gameson1997: 74–75), it is consistent with suggestions regarding the status and ecclesiastical associations of fish, and with their processing being undertaken aceramically. Altogether, the artefactual, zooarchaeological and illustrative material for the consumption of fish is sparse, but the lack of diagnostic residues in pots is strong evidence that when eaten in Viking Age England, fish must have been prepared by non-ceramic means.

Figure 6. A representation of fish at the banqueting table: scene 43 from the Bayeux Tapestry (detail of the official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry – eleventh century; City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, photos: 2017 – La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie).

Fish, pots, identity

Migration and settlement are often marked by culinary change, whether through transformation or hybridisation (e.g. Barrett & Richards Reference Barrett and Richards2004; Holmes Reference Holmes2015; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2021). What is often taken as the most distinctive marker of ‘viking’ culinary identity—fish—does not appear to have made a substantial imprint on the material culture of Anglo-Saxon England. Instead, the culinary habits of communities living in pre-Viking and Viking Age England share remarkable similarities in relation to aquatic products, in contrast to what is seen in pre-Viking and Viking Age southern Scandinavia (Figure 2).

In the context of the late-ninth-century rapid, widespread adoption of an entirely new ceramic repertoire, the absence of appreciable differences in vessel contents across pre-Viking and Viking Age phases is striking. It is possible that adoption of local food technologies helped to ease Scandinavian integration into the Anglo-Saxon milieu. Food is central in identity-making, particularly in contexts of migration and culture contact, and potentially provides better access to private, less-conspicuous display than more archaeologically obvious markers such as architecture and dress accessories. The apparent adoption of native approaches to the use of ceramics is thus instructive.

Moreover, there is little evidence for changes in pottery use after the end of the tenth century and the Fish Event Horizon. This horizon is marked, across northern Europe, by the appearance of increased quantities of fish bones in coastal middens, a new focus on deepwater marine fish (particularly large gadids) and distinctive patterns in butchery marks and body-part representation (e.g. Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Nicholson and Cerón-Carrasco1999; Orton et al. Reference Orton, Morris, Locker and Barrett2014). However, only two of the 27 pots from our sample that clearly date beyond AD 1000 contain aquatic biomarkers, consistent with results from smaller organic residue studies in medieval Oxford and West Cotton, Northants (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Chapman, Blinkhorn and Evershed2019; Craig-Atkins et al. Reference Craig-Atkins2020: 4–8). The changes observed in fishbone assemblages during this time must therefore reflect foods prepared and consumed using aceramic methods. Larger changes in diet came later in the Middle Ages (Harland et al. Reference Harland, Jones, Orton, Barrett, Barrett and Orton2016), as the importation of stockfish to towns such as York made marine fish more accessible.

Conclusion

In Viking Age England, fish were not routinely processed using ceramic cooking pots, suggesting that the ninth-century arrival of Scandinavians in England did not result in observable change in ceramic use. Anglo-Scandinavian communities quickly adopted a new range of continental ceramics, but culinary conservatism appears to have discouraged their use in processing fish. This practice seems homogeneous across eastern England, marking a contrast with eighth- to tenth-century Denmark. The absence of evidence for Scandinavian influence on this aspect of Anglo-Saxon culinary technology echoes the long-discussed invisibility of Vikings in the material culture, settlement and funerary practice of Viking Age England (e.g. Hadley & Richards Reference Hadley and Richards2000) and provides a new line of evidence, arguably speaking more directly to private identities than to conspicuous display.

Data availability statement

Relevant ceramic and lipid data are provided in Table S1.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Harry Robson and Miriam Cubas for laboratory assistance, and to the following for making collections available for analysis: York Archaeology; Museum of London Archaeology; Lincoln Museum and Archives; Newark Museum; North Lincolnshire Museum; English Heritage; Sydvestjyske Museet; Dawn Hadley and Julian Richards. Thanks to Lyn Blackmore, Claus Feveile, Susan Harrison, Antony Lee, Rose Nicholson, Morten and Mette Søvso and Kevin Winter for facilitating access; to Ailsa Mainman for assistance in sample selection and for comments on the text; to André Colonese, Søren Sindbæk and Lars Krants Larsen (Moesgaard Museum) for allowing use of their lipid data; and to our anonymous reviewers. All errors remain the authors’ own.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council project ‘Melting pot: food and identity in the age of the Vikings’ (AH/M008568/1).

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2026.10288 and select the supplementary materials tab.