1.1 Why Are Rivers Important?

Rivers are integral to Earth’s hydrological cycle as well as major agents of landscape change. One of the distinguishing characteristics of Earth is that much of its surface consists of water. Oceans cover 71% of Earth’s surface, glacial ice about 10% of the total land surface, and lakes about 2.0% to 3.5% of the total nonglaciated land area (Verpoorter et al., Reference Verpoorter, Kutser, Seekell and Tranvik2014; Messager et al., Reference Messager, Lehner, Grill, Nedeva and Schmitt2016). The global surface area of rivers is only about 0.58% of Earth’s nonglaciated land surface (Allen and Pavelsky, Reference Allen and Pavelsky2018). In addition to surface water, shallow groundwater supports the growth of terrestrial plants, which consist mainly of water. Through evapotranspiration, sublimation, advection, condensation, and precipitation, water is transferred into the atmosphere, moved laterally to new locations, and redelivered to Earth’s surface. Water supplied to land surfaces moves back to the oceans through runoff, lateral flow of groundwater, and atmospheric processes. Within this hydrological cycle, rivers are the main natural features that convey water from the land surfaces to the oceans. The movement of water over and through landscapes induces solution and erosion of earth materials, the products of which are flushed into rivers. Thus, rivers convey not only water but also sediment and a host of biogeochemical constituents.

Rivers are important for a variety of reasons. From a human standpoint, rivers are a major source of water. Although they contain only 0.006% of the freshwater on Earth (Shiklomanov, Reference Shiklomanov and Gleick1993), rivers supply drinking water for many communities around the world. Water from rivers also is used in industrial operations and for irrigation of agricultural land. Rivers afford opportunities for recreational activities and aesthetic enjoyment. Through the construction of dams for the generation of hydropower, rivers contribute substantially to energy production. As of 2016, hydropower accounted for about 16% of total global electricity generation and supplied 71% of all renewable electricity (World Energy Council, 2019). Large navigable rivers serve as vital transportation corridors for the movement of material goods of economic value. Historically, humans have exploited rivers as convenient disposal receptacles for wastewater from domestic, industrial, commercial, and agricultural activities. Recognition of the adverse effects of wastewater disposal on water quality has led to the development of management strategies that seek to prevent or mitigate pollution of rivers and protect clean water. The intersection between rivers and humans also can have negative consequences for society. Flooding is the most expensive natural hazard in the United States, generating billions of dollars in losses each year. Erosion of riverbanks can threaten structures located along rivers and lead to loss of property. In some areas of the world, rivers have been established as political boundaries, and changes in the courses of rivers over time may result in disputes between governments. From an ecological perspective, rivers are important components of ecosystems, supporting diverse animal and plant communities. Alteration or pollution of rivers through human action can disrupt these communities, generating environmental concern about ecosystem degradation. Finally, from a geomorphological perspective, rivers are primary agents of landscape change on Earth, delivering the majority of sediment eroded from terrestrial landscapes to the ocean basins. Clearly, rivers are vital to human existence and integral components of Earth’s environment.

1.1.1 Why an Emphasis on River Dynamics?

A key emphasis of this book is that rivers are inherently dynamic features. The flow of water in rivers is ever changing in response to variations in precipitation and runoff. Hydrological fluctuations occur over the short term with changes in weather and over the long term with changes in climate. Anthropogenic modifications of climate associated with greenhouse gas emissions have the potential to change the hydrology of rivers on a global scale (Nijssen et al., Reference Nijssen, O’Donnell, Hamlet and Lettenmaier2001; Arnell and Gosling, Reference Arnell and Gosling2016). As flow varies, so does the amount of transported sediment, which responds to changes in the delivery of eroded material to the river from the surrounding landscape and to changes in the capacity of the river to move sediment derived from its bed and banks. Changes in flow and the amount of transported sediment occur frequently and are conspicuous to anyone who observes a river regularly. Less obvious in many cases, even to a regular observer, is change in the form of a river. Although many rivers appear, at least from a human perspective, to change little over time, this lack of evident change merely reflects the long timescales over which change occurs. A view of almost any river in which timespans of decades to centuries were compressed into a few minutes would reveal considerable change. Over such timescales, rivers move and shift across landscapes through processes of erosion and deposition. Over timescales of thousands to millions of years, rivers develop and are eradicated in conjunction with the evolution of entire landscapes.

1.1.2 How Is Fluvial Geomorphology Related to the Study of Rivers?

The study of rivers as natural components of the Earth system falls within the science of fluvial geomorphology – an interdisciplinary field that is embedded within parent disciplines of geography and geology, but that also draws upon and intersects with concepts from fluid mechanics, hydraulics, hydrology, and ecology. Growth in scholarship in fluvial geomorphology over the past 60 to 70 years has exploded as Earth scientists have fully recognized the important role that rivers play in Earth surface systems. Moreover, throughout human history, settlements ranging from small villages to large cities have developed near rivers to take advantage of access to water for human consumption, for agriculture, for industry, for power generation, and for recreation. Increasing societal concern about management of rivers, especially management aimed at protecting environmental values and sustaining natural functions, has greatly enhanced public awareness of the relevance of fluvial geomorphology for generating useful knowledge to guide environmental policy and decision-making. Thus, fluvial geomorphology – once a rather small, esoteric branch of science – has blossomed into a field of considerable scholarly and societal importance.

1.1.3 What Is the Purpose of This Book?

This book presents foundational principles in fluvial geomorphology and explains why these principles are important for understanding rivers as dynamic agents of change in the Earth system. It also relates scientific understanding of rivers to important societal concerns, including the response of rivers to global change; impacts on rivers of land-use change, dams, channelization, and other human activities; and efforts to manage rivers to balance considerations of natural hazards versus environmental quality. It presents essential information on the current understanding of river dynamics and, at least to some extent, relates this understanding to management concerns. The goal is to provide a resource both for scientists interested in fluvial geomorphology and for practitioners dealing with river management issues.

The book is organized around questions related to topics encompassed by fluvial geomorphology. As it is a scientific field, research within fluvial geomorphology is driven by questions. Scientists, including fluvial geomorphologists, are curious about the world and seek knowledge by asking questions and then engaging in research to answer those questions. In some cases, answers to the questions are concrete, whereas in many cases, definite answers have yet to emerge. The search for definitive answers to research questions fuels the process of scientific inquiry.

1.2 What Is a River?

At first glance, the answer to the question “What is a river?” may seem obvious. At the broadest level, a river can be thought of as a body of flowing water that follows a distinct course. This general view, while not inaccurate, does not fully capture the complexity and, to some extent, uncertainty of what a river is or, for that matter, is not. A river is a stream of water in the sense that stream refers to flow. Stream also is a term typically used to describe a small river, but no absolute scientific criteria exist for distinguishing a river from a stream. The form and dynamics of rivers are generally similar over a large range of scales, indicating that the distinction between a stream and a river is mainly colloquial.

Rivers are commonly characterized as watercourses where flow occurs within a channel with well-defined banks. This characterization is generally consistent with the geomorphic perspective of a river as a channeled flow of water. Nevertheless, complications abound. Some rivers, those referred to as intermittent or ephemeral, flow only occasionally and are identified as such in the absence of flow based on the existence of a dry riverbed. Others have multiple channels or poorly defined channel banks. Thus, not all rivers flow all the time, well-defined banks may not always exist, and the number of channels can vary.

Rivers also do not occur in isolation but are components of river networks. The identification of the path of any particular river within a network can be somewhat subjective, based on human preferences. For example, if average amount of flow provided the basis for making such decisions, the Ohio River would be designated as the Mississippi River (or, alternatively, the lower Mississippi River would be renamed the Ohio River), because the amount of flow in the Ohio River typically exceeds that of the upper Mississippi River on an annual basis. The arrangement of rivers in networks can also lead to debate about the length of a particular river. For many years, the Rio Apurimac basin in Peru was considered the source of the Amazon River; however, in 2014, geographers claimed that the Rio Mantaro basin is the most headward source, adding 75–92 km to the maximum length of the river (Contos and Tripcevich, Reference Contos and Tripcevich2014).

Another complicating issue is whether features produced by contemporary river processes should be included as part of the river. Rivers often are associated with flow within a channel or set of channels; however, in alluvial rivers, or those carved within sediment deposited by the river itself, the development of depositional areas of land known as floodplains (discussed in detail in Chapter 14) is linked closely with processes that shape and maintain the channel. In such cases, an appropriate perspective is to view the channel and floodplain as integrated components of the river, rather than identifying the river with the channel only and viewing the floodplain as a separate feature. By contrast, bedrock rivers, or those carved into rock, may not develop floodplains. Also, rivers that are actively incising may become disconnected from their floodplains, so that this feature no longer is an integral component of the river system.

Such complications show that an answer to the question “What is a river?” is more nuanced than it may first appear. The contents of this book inform this question comprehensively, at least from a geomorphological perspective. Rivers are also vital components of ecosystems, an issue that will be touched upon briefly but not treated in detail.

1.3 What Is a River System?

The concept of a system is useful for examining rivers as geomorphological features. A system is a group of interacting components that constitute a unified whole. It is delineated by temporal or spatial boundaries and situated within an environmental setting. In open systems, energy and matter can cross system boundaries to influence internal interactions among system components, which determine system dynamics.

Drainage basins, also known as watersheds and catchments, provide natural geomorphological units for defining river systems within terrestrial landscapes (Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Wolman and Miller1964). A drainage basin delimits a portion of the Earth’s surface that contributes runoff, sediment, and dissolved constituents to a river system. It consists of two basic components: hillslopes and the river network. The drainage divide, a topographic boundary separating runoff between adjacent watersheds, defines the boundary of a drainage basin (Figure 1.1). Runoff within the boundary of the drainage basin will move over or through hillslopes into the river network within the watershed. The downstream locus, or mouth, of the watershed provides a common outlet for all water and sediment exiting the watershed (Figure 1.1). A drainage basin can be defined upstream of any particular location along a river network, ranging from the downstream limit, where a large river flows into the ocean, to the most headward locations, where the smallest streams begin. Thus, drainage basins are arranged in a hierarchical, nested configuration.

Figure 1.1. Three-dimensional view of a drainage basin for the upper part of the Sangamon River in Illinois, United States, showing drainage divide (black line), basin outlet (red dot), and stream network (blue lines).

Rivers develop within drainage basins and are influenced by inputs of precipitation to these basins, which produce runoff on and through hillslopes, supplying water to rivers. Runoff on hillslopes also erodes sediment that moves into the rivers. Thus, rivers are open systems that receive fluxes of material from hillslopes within drainage basins.

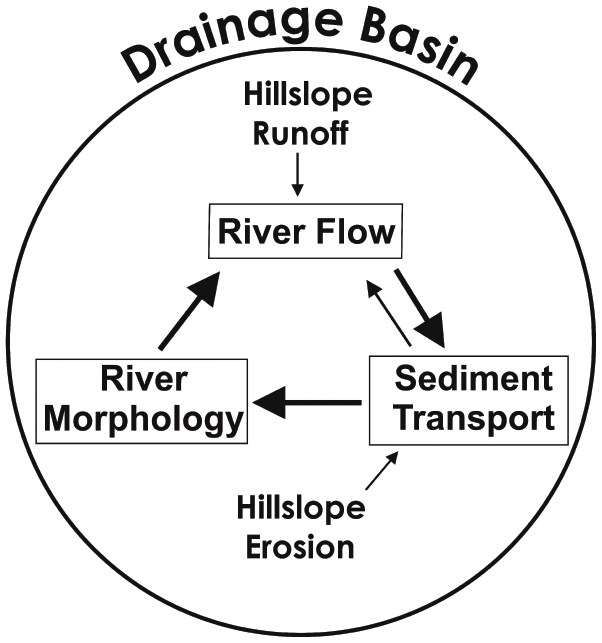

Three interrelated components – flow, sediment transport, and morphology – characterize a river system (Figure 1.2). Flow varies with changes in runoff and provides the mechanism for erosion, transportation, and deposition of sediment within the river system. Under certain circumstances, sediment transported by the river can affect hydraulic characteristics of the flow, leading to feedback between the flow and sediment transport. The movement of sediment shapes the morphology of the river, especially material mobilized along the boundaries of channelized flow – the bed and banks of the river. In many cases, the main morphological feature associated with the river system is a channel, but morphology includes any component of form that is part of the river system. Some morphological features, such as floodplains, are influenced by deposition of fine material delivered to the river from hillslopes. River morphology constrains hydraulic conditions, thereby influencing characteristics of the flow. According to this view, river dynamics involve inputs of water and sediment from drainage basins that drive interaction among flow, sediment transport, and morphology (Figure 1.2). This structure, which appears simple, in reality leads to complex dynamics, in part because the interdependence is typically highly nonlinear. For example, the existence of thresholds in river systems can result in an abrupt change in the state or morphology of a system when the threshold is attained or surpassed.

Figure 1.2. Basic structure of a river system. Runoff and erosion on hillslopes within drainage basins deliver water and sediment to rivers, the dynamics of which are characterized by interaction among flow, sediment transport, and morphology.

1.4 What Is Fluvial Geomorphology?

The field of fluvial geomorphology derives its name from fluvius – the Latin word for river, stream, or running water; gé (Γή) – the Greek word for land or earth; and morphé (μορφή) – the Greek word for form or shape. This branch of science not only studies how rivers shape Earth’s surface; it also examines the dynamics of rivers. It is a subfield of geomorphology, a relatively young science rooted in the development of the earth sciences, particularly geology and physical geography (Tinkler, Reference Tinkler1985).

1.4.1 What Is the History of Fluvial Geomorphology?

Recognition of the importance of fluvial processes in shaping Earth’s surface emerged in the eighteenth century and was closely associated with the advent of uniformitarianism. This principle holds that natural processes operating over long timespans govern the dynamics of the Earth system. The foundation of uniformitarian thought was established by James Hutton (Reference Hutton1795), who has been referred to as the founder of modern geology (Bailey, Reference Bailey1967), the first great fluvialist (Chorley and Beckinsdale, Reference Chorley and Beckinsdale1964), and even the founder of geomorphology (Orme, Reference Orme, Shroder, Orme and Sack2013). Hutton’s ideas emphasized the importance of fluvial processes in ceaselessly reshaping Earth’s surface. Although Hutton died shortly after publishing his work, his ideas were championed by John Playfair (Reference Playfair1802), who expanded on Hutton’s scheme and expressed its central tenets with a degree of inspirational clarity that greatly surpassed the convoluted prose of Hutton. What has become known as Playfair’s Law is a shining example of his eloquent style and a beautiful articulation of the way in which rivers, arranged in networks, carve the landscape into a system of valleys (Box 1.1). At the time it was written, the statement countered the prevailing notion that Earth’s valleys were carved by one or more divinely instigated catastrophic deluges (Orme, Reference Orme, Shroder, Orme and Sack2013).

Every river appears to consist of a main trunk, fed from a variety of branches, each running in a valley proportioned to its size, and all of them together forming a system of vallies, communicating with one another, and having such a nice adjustment of their declivities, that none of them joins the principal valley, either on too high or too low a level; a circumstance which would be infinitely improbable, if each of these vallies were not the work of the stream that flows in it.

The term “geomorphology” was introduced in the late 1800s, probably by geologist W.J. McGee (Tinkler, Reference Tinkler1985), at a time when the nascent field of landform studies was growing rapidly through insights gained from explorations of the dramatic landscapes of the American West (Chorley and Beckinsdale, Reference Chorley and Beckinsdale1964; Sack, Reference Sack, Shroder, Orme and Sack2013). Fluvial processes stood at the center of ideas emerging from these explorations. John Wesley Powell (Reference Powell1875, p. 208), who undertook the first organized scientific expedition of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, noted in his report: “All the mountain forms of this region are due to erosion; all the cañons, channels of living rivers and intermittent streams, were carved by the running waters, and they represent an amount of corrasion difficult to comprehend.” Powell introduced the seminal concept of base level, the idea that erosion by rivers has a vertical limit. In the case of a tributary, it is the level of the main river it joins, and in the case of a main river that flows into the ocean, it is sea level.

Grove Karl Gilbert, who worked under the direction of John Wesley Powell, set an example for much contemporary research in geomorphology, including fluvial studies (Pyne, Reference Pyne1980). Through his training in geology and mechanics, Gilbert approached problems of landform development by integrating field observations with physical theory. His work on the Henry Mountains in Utah invoked systems concepts, equilibrium thinking, and force-balance relations to explain how running water acts to shape landscapes through erosion and deposition (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1877). He introduced the concept of grade, a state of dynamic adjustment whereby a river attains a capacity of transport equivalent to the amount of sediment supplied to it. Later in his career, he conducted seminal experimental research on the transportation of sediment by running water (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1914) and tried to use knowledge he gained from these experiments to understand how the introduction of vast amounts of sediment by humans from hydraulic mining for gold affected rivers of the Sierra Nevada (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1917) (see Chapter 15).

The development of geomorphology accelerated between the late 1800s and the early 1900s when William Morris Davis, a geologist at Harvard who also championed the development of geography as a formal academic discipline in the United States, proposed his theory of the geographical cycle, or cycle of erosion (Davis, Reference Davis1889, Reference Davis1899). This theory held that landscapes uplifted above sea level and eroded by fluvial action evolve through a systematic sequence of distinctive stages (Figure 1.3). An uplifted landscape progresses through stages of youth, maturity, and old age as rivers incise into it and hillslopes produced by river incision are worn down by surface runoff. Eventually, the entire landscape, if not uplifted beforehand, is beveled to a flat surface standing just above sea level – a feature Davis referred to as a peneplain. The cyclic aspect of the theory comes into play when uplift eventually recurs, reinitiating the sequential stages of development. The scope of the theory addressed the evolution of landscapes of regional extent over timespans involving millions or tens of millions of years. The impact of Davis and his theory was enormous and dominated geomorphological inquiry from the late 1800s to the middle of the twentieth century (Chorley et al., Reference Chorley, Beckinsdale and Dunn1973). This method of inquiry mainly involved trying to classify landscapes into stages of the cycle through visual observations or map-based analysis of landscape characteristics combined with descriptive geological investigations that focused on defining the relative timing of different stages of landscape evolution. Although cyclic models were developed for landscapes other than those dominated by fluvial erosion in humid-temperate environments (e.g. Hobbs, Reference Hobbs1921), and alternative perspectives on landscape evolution emerged in response to the Davisian view (e.g. King, Reference King1953; Penck, Reference Penck1972), all these models also were qualitative. Thus, geomorphology textbooks published between 1900 and 1950 were largely descriptive treatises on how landforms, including rivers, develop and change (Rhoads, Reference Rhoads, Shroder, Orme and Sack2013).

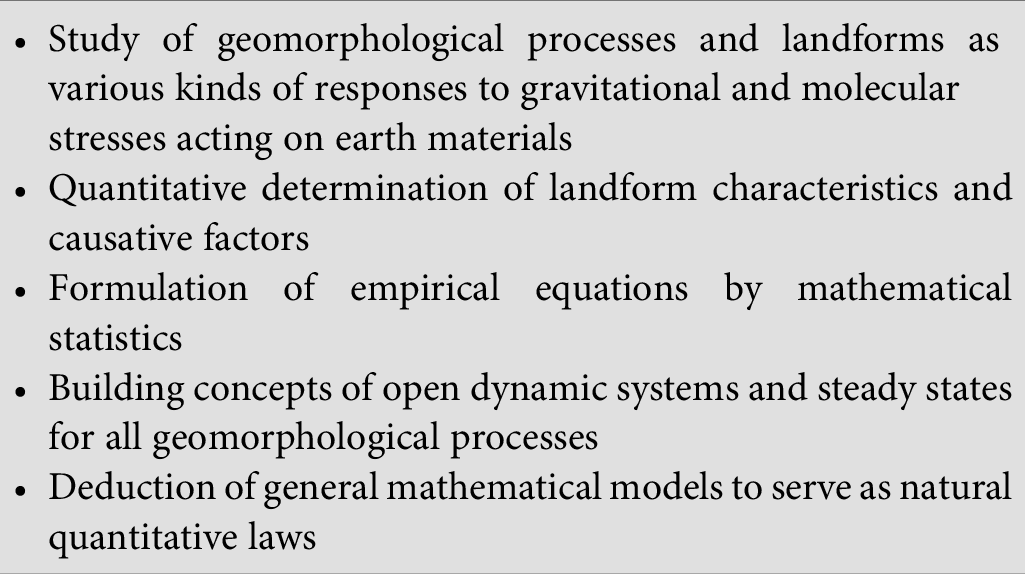

Seminal work by Robert E. Horton (Reference Horton1945), a hydraulic engineer, on the erosional development of drainage basins and stream networks based on physical reasoning planted a seed of change amongst a new generation of geomorphologists who were increasingly dissatisfied with the qualitative Davisian approach. A subsequent landmark paper by Arthur Strahler (Reference Strahler1952a) called for a dynamic basis of geomorphology focusing on a quantitative approach to the study of landforms and the processes that shape landforms (Table 1.1). This new perspective, which supplanted the Davisian view and has persisted since the 1950s, emphasizes the importance of understanding processes and process–form interactions in producing knowledge of geomorphic systems (Rhoads, Reference Rhoads, Shroder, Orme and Sack2013). It is consistent with Gilbert’s approach to geomorphological inquiry, which was long overshadowed by Davis’s ideas. The conception of geomorphic processes, including those related to rivers, as the manifestation of mechanistic action has led to the infusion of principles from classical (Newtonian) mechanics into geomorphology. Foundational work in fluid dynamics and hydraulics by Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782), Antoine de Chezy (1718–1792), Robert Manning (1816–1897), William Froude (1810–1879), and Osbourne Reynolds (1842–1912) has become relevant to process-based studies of river dynamics. Thus, contemporary fluvial geomorphology has twin historical roots: one planted in the earth sciences (geology and physical geography) and the other in the development and application of classical mechanics to topics related to rivers (hydraulics and fluid dynamics) (Orme, Reference Orme, Shroder, Orme and Sack2013).

Table 1.1. Elements of a dynamic basis of geomorphology.

|

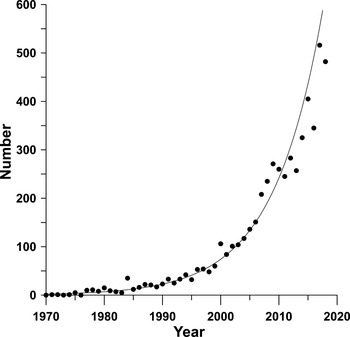

A major change in fluvial geomorphology that accompanied the shift toward process-based inquiry has been a focus on issues with time and space scales that coincide with societal concerns related to rivers. Whereas the Davisian perspective tended to examine how rivers shaped landscapes over regional scales and millions of years, the process approach embraces studies examining how individual rivers or sections of rivers are influenced by individual formative events or changes in the frequency of these events. It also explores the role of humans as geomorphic agents who are capable of changing rivers directly and triggering responses to these changes. The relevance of fluvial geomorphology to river management and to attempts to protect, preserve, or improve the environmental quality of river systems has therefore increased, resulting in rapid growth in research in this field of science (Figure 1.4) and in its visibility within the public domain.

Figure 1.4. Increase in number of publications containing topic words fluvial and geomorphology between 1970 and 2018 based on a Web of Science© search.

1.4.2 What Are the Different Styles of Scientific Inquiry in Fluvial Geomorphology?

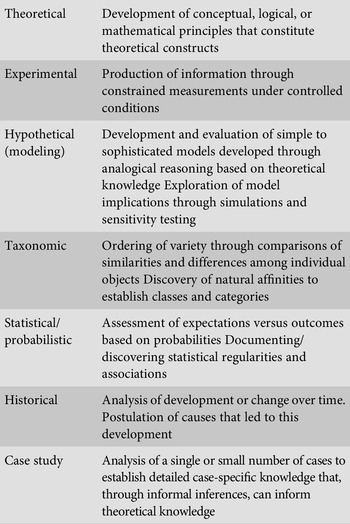

Scientific inquiry in fluvial geomorphology is diverse. Any scheme that attempts to capture the full range of diversity will almost certainly be incomplete. With that in mind, at least seven different styles of inquiry can be recognized (Table 1.2). These styles are not necessarily mutually exclusive and often intersect to some extent within individual investigations.

Table 1.2. Styles of inquiry in fluvial geomorphology.

| Theoretical | Development of conceptual, logical, or mathematical principles that constitute theoretical constructs |

| Experimental | Production of information through constrained measurements under controlled conditions |

| Hypothetical (modeling) | Development and evaluation of simple to sophisticated models developed through analogical reasoning based on theoretical knowledge Exploration of model implications through simulations and sensitivity testing |

| Taxonomic | Ordering of variety through comparisons of similarities and differences among individual objects Discovery of natural affinities to establish classes and categories |

| Statistical/probabilistic | Assessment of expectations versus outcomes based on probabilities Documenting/discovering statistical regularities and associations |

| Historical | Analysis of development or change over time. Postulation of causes that led to this development |

| Case study | Analysis of a single or small number of cases to establish detailed case-specific knowledge that, through informal inferences, can inform theoretical knowledge |

Many theoretical principles in fluvial geomorphology derive from the basic sciences such as physics, chemistry, and biology. Examples from physics include conservation of mass and momentum as well as force–resistance relations. Gravitational forces and fluid forces are the principal types of forces acting in river systems, and expressions for these forces typically are derived from principles of mechanics, at least at the highest level of formalism. Developing foundational principles within fluvial geomorphology that have the same level of certainty as principles from foundational sciences has proven challenging. For example, sediment transport is an essential fluvial process, and considerable effort has been devoted to the search for universal geomorphic transport laws (Dietrich et al., Reference Dietrich, Bellugi, Sklar, Wilcock and Iverson2003; Hicks and Gomez, Reference Hicks, Gomez, Kondolf and Piegay2016). Despite this effort, the development of such universal relations remains elusive.

Other principles, sometimes referred to as regulative principles, are qualitative. Regulative principles constrain possibilities related to the structure or dynamics of a fluvial system and therefore provide a basis for the development of explanatory frameworks (Rhoads and Thorn, Reference Rhoads and Thorn1993). Examples of such principles include optimality conditions, such as a fluvial system tending toward a steady state or toward a state that minimizes or maximizes a system property, and nonlinear dynamical behavior, such as evolution of the system toward an attractor state or along a distinct trajectory. Whether qualitative or quantitative, sets of principles provide guidance for the development of models, either mathematical or conceptual, to represent the structure and dynamics of fluvial systems.

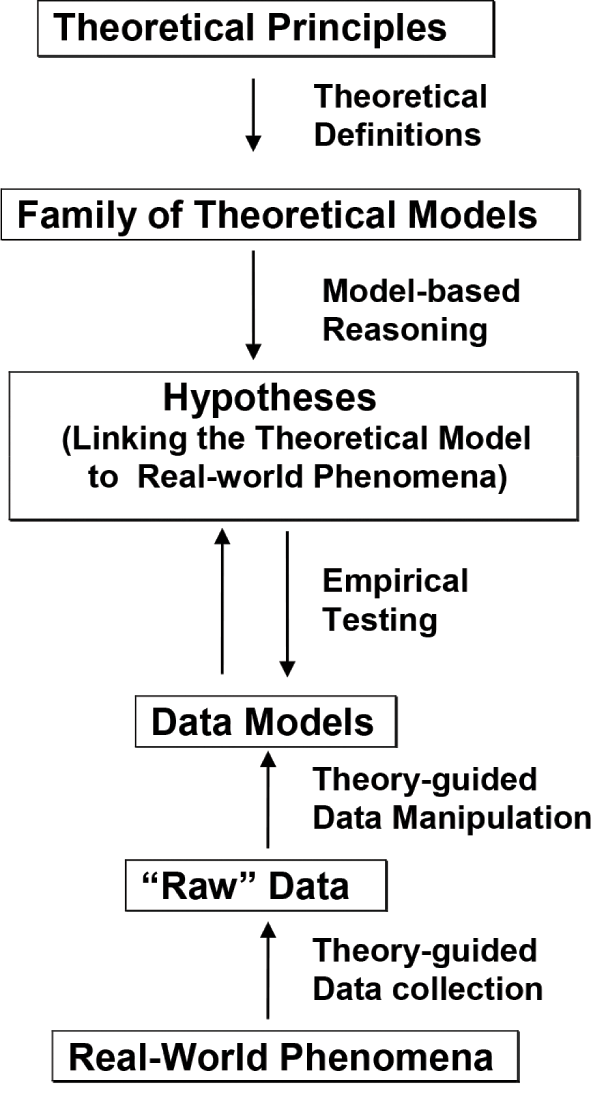

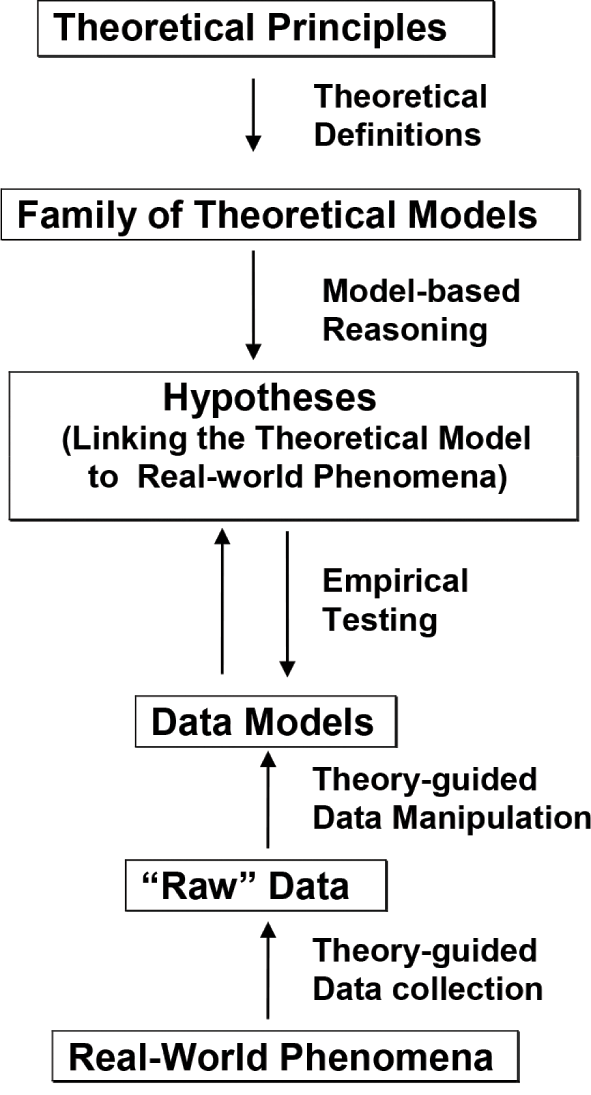

Contemporary perspectives within geomorphology embrace the model-theoretic view (MTV) of scientific theory (Rhoads and Thorn, Reference Rhoads, Thorn, Gregory and Goudie2011). According to MTV, models are the primary constituents of theory structure. Models connect theoretical and regulative principles to testable hypotheses about the real world (theoretical models) and also provide data-based representations of these models (data models). Empirical testing involves comparing hypotheses derived from theoretical models with evidence embedded in data models (Figure 1.5). Theoretical models are representational devices that facilitate intellectual access to real-world phenomena; in the case of fluvial geomorphology, representation focuses on river systems. The manner of representation includes descriptions, mathematical equations, probabilistic functions, computer algorithms, diagrams, pictorial displays, images, and physical artifacts (i.e., “hardware”) (Odoni and Lane, Reference Odoni, Lane, Gregory and Goudie2011; Grant et al., Reference Grant, O’Connor, Wolman, Schroder and Wohl2013; van de Wiel et al., Reference van de Wiel, Rousseau, Darby, Kondolf and Piegay2016). However, no single model fully captures the content of a theory. Because many different discrete representations of theoretical principles are possible, these principles provide support for an interconnected set, or family, of models. Thus, according to MTV, a theory comprises a set of theoretical principles and a family of models that embodies these principles (Giere, Reference Giere1988).

Figure 1.5. The model-theoretic view of scientific theory.

Data models also are representational, but these models represent real-world phenomena through information, or data, collected about the phenomena. The collection and processing of data are guided by theory and conducted with a theoretical objective in mind – usually a hypothesis or set of hypotheses derived from a theoretical model. The result of data processing is a data model. The processed information embodied in the data model provides the basis for testing the hypotheses derived from the theoretical model. In cases where theoretical understanding of a phenomenon is uncertain, data models may be developed relatively autonomously from theoretical models. However, scientists continuously strive to link data models that yield intriguing patterns or outcomes to explanatory theoretical principles through the development of theoretical models. Thus, models and theory are intertwined at all levels of scientific practice.

The MTV also provides a basis for embracing different styles of inquiry (Table 1.2). Theoretical, hypothetical, and taxonomic styles provide the basis for the formulation of theoretical models, whereas experimental, historical, and case study approaches relate closely to the production of data models. Statistical/probabilistic styles of inquiry may contribute to either type of model, depending on the specific way in which the model is applied.

Over the past several decades, the development of analytical and numerical models of river systems has increased dramatically (Coulthard and Van de Wiel, Reference Coulthard, van de Wiel, Shroder and Wohl2013a; Nelson et al, Reference Nelson, McDonald, Shimizu, Kondolf and Piegay2016; Pizzuto, Reference Pizzuto, Kondolf and Piegay2016). Such models provide the basis for the development of sets of hypotheses about the dynamics of fluvial systems. Predictions about some aspect of a river system produced by a model represent hypotheses. In using the model to generate predictions, it is assumed that the underlying governing equations of the model represent valid representations of a river system. Hypothesis testing involves comparing the model predictions with results of data models derived from a systematic measurement program. Validated models can then be used to develop additional predictions about river systems that extend beyond the domain of the information and setting on which the data model was based. This use of validated mathematical models to explore potential real-world implications can be thought of as a form of experimentation (Kirkby, Reference Kirkby, Rhoads and Thorn1996; Church, Reference Church, Gregory and Goudie2011); however, the outcomes of numerical experiments, to be connected to the real world, must be validated through empirical testing using appropriate data models. Thus, numerical experimentation is a method of hypothesis generation rather than a method of generating observations for model testing, as is the case with empirical experimentation. In this sense, predictions or forecasts generated by mathematical models represent sophisticated thought experiments (Kirkby, Reference Kirkby, Rhoads and Thorn1996).

Taxonomy, or classification, as in any scientific endeavor, has played and continues to play an important role in fluvial geomorphology (Buffington and Montgomery, Reference Buffington, Montgomery, Shroder and Wohl2013; Kondolf et al., Reference Kondolf, Piegay, Schmitt, Montgomery, Kondolf and Piegay2016). The stages in Davis’s cycle of erosion (Figure 1.3) represent categories of landscape development. Today, fluvial geomorphologists continue to try to determine general characteristics of river systems to provide the basis for identifying distinct kinds of rivers. This effort to classify constitutes a basic form of theorizing, in the sense that generalization is accomplished by hypothesizing that different kinds of rivers exist and that each kind of river shares common properties compared with other kinds. Classes, once established, also provide the basis for further theorizing about causal mechanisms that lead to the development of different kinds of rivers. Over time, however, classes may change as theoretical understanding evolves (Church, Reference Church, Gregory and Goudie2011).

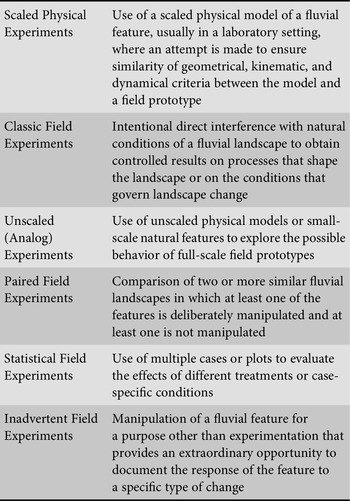

Empirical experimental research in geomorphology, which plays an important role in the development of data models, is not restricted solely to the use of scaled physical (hardware) models (e.g. Peakall et al., Reference Peakall, Ashworth, Best, Rhoads and Thorn1996) but can be viewed more generously as encompassing a variety of field investigations (Table 1.3). Unscaled physical models have been widely used in fluvial geomorphology to explore the dynamics of river systems (Schumm et al., Reference Schumm, Mosley and Weaver1987; Metivier et al., Reference Metivier, Paola, Kozarek, Tai, Kondolf and Piegay2016). Insights provided by such models, despite the lack of strict scaling with field prototypes, have been substantial (Paola et al., Reference Paola, Straub, Mohrig and Reinhardt2009). Inadvertent experimental opportunities to study river responses to human-induced change are not uncommon, given that humans have modified river channels in a variety of ways for purposes other than scientific experimentation. Intentional field experiments for a scientific purpose are less common, but recent efforts have sought to attain at least partial experimental control at field scales (Wohl, Reference Wohl2013a; Sukhodolov, Reference Sukhodolov2015).

Table 1.3. Types of experimental research in geomorphology.

| Scaled Physical Experiments | Use of a scaled physical model of a fluvial feature, usually in a laboratory setting, where an attempt is made to ensure similarity of geometrical, kinematic, and dynamical criteria between the model and a field prototype |

| Classic Field Experiments | Intentional direct interference with natural conditions of a fluvial landscape to obtain controlled results on processes that shape the landscape or on the conditions that govern landscape change |

| Unscaled (Analog) Experiments | Use of unscaled physical models or small-scale natural features to explore the possible behavior of full-scale field prototypes |

| Paired Field Experiments | Comparison of two or more similar fluvial landscapes in which at least one of the features is deliberately manipulated and at least one is not manipulated |

| Statistical Field Experiments | Use of multiple cases or plots to evaluate the effects of different treatments or case-specific conditions |

| Inadvertent Field Experiments | Manipulation of a fluvial feature for a purpose other than experimentation that provides an extraordinary opportunity to document the response of the feature to a specific type of change |

Process-based field investigations in fluvial geomorphology commonly implement rigorous measurement protocols designed explicitly to test hypotheses derived from theoretical models at a single site or a small number of sites. Measurement protocols for such investigations are based on a theory-guided experimental design, but in the field it is typically not possible to control boundary conditions, such as the inputs of flow and sediment to the reach under study or the composition and morphology of the channel bed and banks within this reach. It is possible, however, to document the boundary conditions in detail. This information on boundary conditions provides the basis for calibrating theoretical models to predict river dynamics in the specific field situation of interest. Testing involves comparing model predictions with outcomes of data models generated by field measurements. These process-based case studies (Table 1.2) are pseudo-experimental in the sense that complete experimental control is not achieved, but data are collected using an experimental design aimed at testing theoretical models within specific field contexts (Richards, Reference Richards, Rhoads and Thorn1996).

Statistical analysis became prominent in fluvial geomorphology after the transition to process-based research in the 1950s. Many field studies in fluvial geomorphology involve collection of data sets with large sample sizes and analysis of the collected data using statistical methods to try to isolate the independent covariance between variables of interest (Piegay and Vaudor, Reference Piegay, Vaudor, Kondolf and Piegay2016). Some of this work is highly exploratory with only a weak connection to explanatory theoretical principles. Other work, such as statistical modeling, intersects with the hypothetical style of inquiry (Rhoads, Reference Rhoads1992); statistical models are often formulated a priori based on theoretical reasoning, and then hypotheses embedded in the models are evaluated through significance testing by statistically fitting the model to empirical data. Many bivariate and multivariate relations in fluvial geomorphology are expressed in the form of power functions, given that variables related to rivers typically have log-normal probability distributions (Appendix A). Familiarity with power functions and the method by which such functions are derived statistically is therefore important for understanding statistical associations related to river systems.

Historical studies in fluvial geomorphology rely on two types of information: historical records produced intentionally by direct measurement or monitoring programs and geohistorical data derived from the artifacts of human or biophysical activities. Systematic attempts to collect scientific data of relevance to understanding rivers are relatively recent. Relevant sources that can provide information about past conditions of rivers include newspaper articles, old maps, land survey records, stream gaging data, sediment discharge information, ground-based photographs, bridge surveys, and travel accounts (Trimble and Cooke, Reference Trimble and Cooke1991; Trimble, Reference Trimble2008, Reference Trimble2013; Grabowski and Gurnell, Reference Grabowski, Gurnell, Kondolf and Piegay2016). Aerial photography, available for areas in the United States since the 1930s, and satellite remote-sensing imagery, available for most areas of the world since the 1960s, now afford remarkable opportunities to examine dynamic change in the characteristics of rivers over time (Gilvear and Bryant, Reference Gilvear, Bryant, Kondolf and Piegay2016), particularly given that most of these data are in the public domain. Geohistorical data typically extend beyond the limited temporal domain of human-generated information on river systems. Such data include sedimentological information, methods of absolute and relative dating, biogeochemical analyses, and archeological artifacts (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Petit, James, Kondolf and Piegay2016; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, O’Connor, Oguchi, Kondolf and Piegay2016).

1.4.3 What Are the Basic Types of Scientific Reasoning in Fluvial Geomorphology?

Two distinct types of scientific reasoning are common in fluvial geomorphology: deductive reasoning and abductive reasoning. Both these types of reasoning are informed by theory, but in different ways (Rhoads and Thorn, Reference Rhoads and Thorn1993). Deductive reasoning is common in process-based approaches to inquiry, which typically involve testing of theoretical hypotheses about general process or process–form relations. Theoretical hypotheses are derived deductively from theoretical models. Such hypotheses typically have the form if A, then B, where commonly A is a cause and B is an effect. Testing of deductive theoretical hypotheses in process-based studies involves comparing the claims of these hypotheses with results embodied in a data model. Ideally, the test should involve generation of A and confirmation that A causes B through data-based evidence embodied in a data model. Of course, if B does not occur, or occurs because of a cause other than A, the outcome of the test would not support the hypothesis. In some instances (e.g., nonexperimental conditions), it may not be possible to generate A directly; in such cases, process-based studies typically rely on abductive reasoning.

Many studies based on historical sources of information, but particularly those that rely on geohistorical data, are fundamentally reconstructive in nature in that the goal is to determine the event or series of events (A) that caused the development of a contemporary fluvial feature. In such cases, data on the cause (A) are not directly or even indirectly available (e.g., a large flood that occurred in the distant past cannot be “remeasured” if it was not measured at the time it occurred). As a result, abductive, rather than deductive, reasoning is common in geohistorical investigations. This reasoning involves first observing a feature B (an effect) for which one seeks an explanatory cause (A). By consulting background knowledge, a potential explanation of the type “if A, then B” is identified as providing a possible explanation for B. In other words, A becomes a hypothetical cause of B. Abductive reasoning based on geohistorical information has an inherently higher level of uncertainty than deductive reasoning based on direct documentation of cause–effect relations because the documentation of a particular effect (B) does not guarantee the occurrence of a specific cause (A) (Rhoads and Thorn, Reference Rhoads and Thorn1993). Another cause (C) may also account for the particular effect of interest (B). Typically, further work is needed to evaluate the hypothesis. For example, if A causes D in addition to B, and evidence for D can be confirmed in conjunction with B, the hypothesis gains further support.

A complication of simple cause–effect reasoning in fluvial geomorphology is that rivers are situated within complex natural environments, where a variety of factors can affect these systems. In particular, contingency is often a major consideration in determining how rivers are structured and how they change through time. This contingency includes attributes of the particular contemporary environmental setting in which the river is located as well as the particular historical sequence of circumstances that have shaped the characteristics of the river. In this sense, every river is unique. Although this inherent contingency confounds determinations of the extent to which general physical principles govern river dynamics, it also highlights how manifestations of processes governed by general principles develop in particular instances. From a scientific perspective, the variety of different methods of inquiry (Table 1.2) provide tools for trying to unravel the interrelated roles of generality and specificity in river dynamics. From a practical standpoint of river management, consideration of the influence of contingent factors on river dynamics is important, particularly when the focus of management is on a particular river.

1.5 How Do the Dynamics of River Systems Vary over Time and Space?

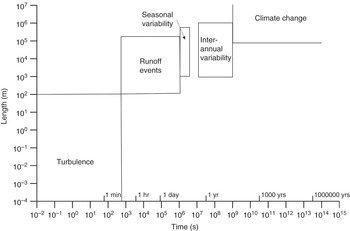

The dynamics of river systems, which are related to the hydrological and hydraulic characteristics of river flow, vary over a wide range of temporal and spatial scales. River flows are turbulent (see Chapter 4); thus, the smallest relevant scales of dynamic variability of these flows are defined by the smallest length (![]() ) and time (

) and time (![]() ) scales of turbulent flow, known as Kolmogorov microscales:

) scales of turbulent flow, known as Kolmogorov microscales:

(1.1)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.2)

where ν is the kinematic viscosity of water and ![]() is the turbulent dissipation rate (Tennekes and Lumley, Reference Tennekes and Lumley1972). Assuming a value of ν for water at 20 °C (1.00 × 10−6 m2 s−1) and a value of

is the turbulent dissipation rate (Tennekes and Lumley, Reference Tennekes and Lumley1972). Assuming a value of ν for water at 20 °C (1.00 × 10−6 m2 s−1) and a value of ![]() for turbulent river flow of 0.0005 m2 s−3 (Sukhodolov et al., Reference Sukhodolov, Thiele and Bungartz1998) yields Kolmogorov microscales of

for turbulent river flow of 0.0005 m2 s−3 (Sukhodolov et al., Reference Sukhodolov, Thiele and Bungartz1998) yields Kolmogorov microscales of ![]() m and

m and ![]() . The time-space domain of turbulence extends up to coherent turbulent structures that in the world’s largest rivers may be a hundred meters in diameter and evolve over timescales of many minutes (Figure 1.6).

. The time-space domain of turbulence extends up to coherent turbulent structures that in the world’s largest rivers may be a hundred meters in diameter and evolve over timescales of many minutes (Figure 1.6).

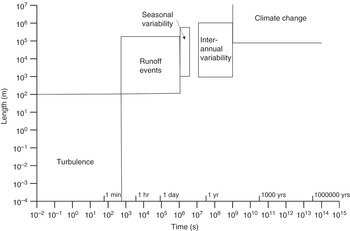

Figure 1.6. Time-space domains of flow dynamics in rivers.

Variations in runoff associated with changing weather conditions are a major source of flow variability in rivers. The duration of individual hydrological events can vary from a few minutes in the smallest streams to several weeks in large rivers. Highly localized events may affect only a few hundreds of meters of small streams, whereas large storms can produce variations in flow that extend over hundreds of kilometers of river length. Seasonal variability is another factor that can produce spatial and temporal variation in river flow. The timescale of this variability, which may affect broad geographic areas, is typically several months. Weather conditions also vary from year to year or over periods of years, resulting in interannual variability in river flow. Over timescales of decades to millennia, changes in climate can contribute to flow variability. The spatial domain of climate change extends to the global scale. Changes in river flow at this scale are of growing concern in relation to human-induced climate change.

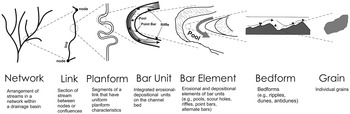

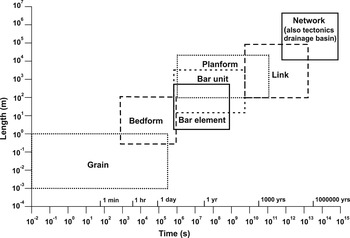

The morphological structure of alluvial river systems within drainage basins can be viewed hierarchically (Figures 1.7 and 1.8). At the largest scales, rivers form branching networks that extend throughout drainage basins. Discrete segments of rivers between nodes where streams join, also known as confluences, constitute links. Within links, the pattern or planform of the river – what it looks like when viewed from above – becomes evident. Within rivers with different types of planforms, distinctive patterns of erosion and deposition on the channel bed produce bar units. Parts of bar units are associated with discrete morphological features, or bar elements, that differ in substrate composition and elevation of the channel bed. At still smaller scales, different types of bedforms develop within the river system. Individual grains represent the smallest morphological units within river systems, but the absolute size of individual grains can vary over several orders of magnitude, ranging from large boulders a meter or more in diameter to microscopic clay particles.

Figure 1.7. Hierarchical morphological structure of alluvial river systems.

Figure 1.8. Time-space domains of fluvial morphodynamics.

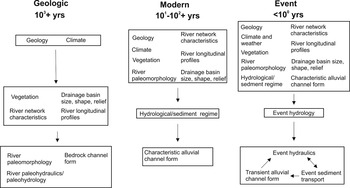

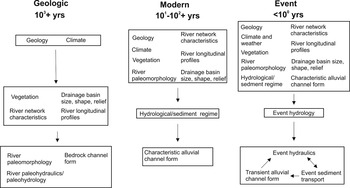

The morphodynamics of river systems vary depending on the morphological features of interest. Three relevant timescales can be identified: geologic, modern, and event (Figure 1.9) (Schumm and Lichty, Reference Schumm and Lichty1965). Large drainage basins and river networks evolve over thousands to millions or even tens of millions of years. The evolution of watershed size, shape, and relief; of vegetation throughout watersheds; and of the characteristics of the stream networks within these watersheds generally occurs over geologic timescales. These aspects of river system morphology are dependent mainly on the climatic and geological conditions that exist over these long time intervals (Figure 1.9). Geological conditions include the type of rock into which the watershed is carved, structural characteristics of this rock, such as folding and faulting, and the spatial extent and rate of tectonic activity. Over geologic timescales, drainage basins and river networks come into existence, coevolve, and are eradicated as the Earth’s terrestrial surfaces are affected by global changes in climate and tectonism. Climate influences runoff and erosion, which carve drainage basins and stream networks into the geological framework of the landscape. It also plays a major role in determining the type of vegetation on the landscape. The properties of the drainage basin, river network, and vegetation, along with climate and geology, in turn shape the form of bedrock channels, which typically evolve over geologic timescales. Moreover, these factors determine the past (paleo-) hydrology, hydraulics, and morphology of rivers, evidence of which is sometimes preserved in the sedimentary record.

Figure 1.9. Hierarchical structure of river morphodynamics and controlling factors over different timescales. Absolute times in years associated with geologic, modern, and event timescales are approximate. Arrows indicate direction of causality.

Although the properties of drainage basins, stream networks, and river longitudinal profiles change continuously over time through the interplay of erosional, depositional, and tectonic activity, amounts of change usually are negligible over timescales of decades to centuries. These properties, along with characteristics of vegetation, are, in many instances, relatively constant over modern timescales. The hydrological and sediment regimes of a river system within a drainage basin consist of flows and sediment fluxes of different magnitudes and frequencies occurring through time and over space in conjunction with characteristics of climate, vegetation, and drainage-basin morphology. Depending on the properties of these regimes and the extent to which the regimes are stationary, characteristic forms can develop in alluvial rivers. These aspects of river morphology exhibit constancy over time in the sense that they vary not at all or fluctuate only a small amount about a constant average state over modern timescales, even though the hydrologic and sediment regimes encompass considerable variability in the magnitudes of flows and sediment fluxes produced by discrete hydrological events. The concept of characteristic forms often is equated with the regulative principle of a steady or equilibrium state; however, considerable confusion surrounds the use of equilibrium terminology in geomorphology (Thorn and Welford, Reference Welford1994). Despite this confusion, the notion of equilibrium states in river systems often provides the basis for contemporary environmental management of rivers.

Over timescales of individual hydrological events or series of events, i.e., event timescales, many aspects of channel form exhibit transient dynamics (Figure 1.9). For many fluvial systems, event dynamics occur within the context of characteristic forms, which constrain these dynamics (Figure 1.9). Transiency in rivers that develop characteristic forms is limited because unchanging aspects of channel form regulate interaction among hydraulic conditions, sediment transport, and channel form. Nevertheless, in many rivers, even those that remain fairly constant in form, channel position can change through event-driven avulsion or migration. Bar forms and bed forms can be rearranged as flow varies within an event or between events. Sorting of sediment on the surface of bar elements may be altered as the flow rises and falls.

Not all rivers develop characteristic forms; some exhibit marked transient morphodynamics, even over modern timescales. In rivers that are highly sensitive to change, virtually all aspects of river morphology can be rearranged by discrete events. The form of such rivers does not vary closely about a constant average morphological state. For these rivers, event dynamics may occur over timescales much greater than 100 years.

The hierarchical structure of morphodynamics over space and time provides two important lessons for understanding river systems. First, processes that occur elsewhere along a river, within the network of which the river is part, and within the watershed within which the river is situated influence the form and dynamics of a river at any particular location. This lesson emphasizes the importance of spatial connectivity within river systems (Czuba and Foufoula-Georgiou, Reference Czuba and Foufoula-Georgiou2015), even though the understanding of this connectivity is far from complete (Fryirs, Reference Fryirs2013). Second, not all aspects of the river system change dynamically at the same rates or are influenced by the same temporal scales of flow variability. Thus, rivers have morphological “memories” related to historical change. A river is a “physical system with a history” (Schumm, Reference Schumm1977, p. 10). Although it is clear that river dynamics encompass an immense range of temporal scales, understanding of interconnections among processes and forms across this range of scales is far from complete.

1.6 What Is the Role of Humans in River Dynamics?

Missing from the time-space conceptual scheme (Figure 1.9) is the role of human agency. Increasingly, humans have become agents of change in river systems. An abundance of geomorphological research over the past several decades shows that humans are substantially affecting river systems at the event and modern timescales (see Chapter 15). In some cases, humans also appear to be producing long-lasting effects that may persist over geologic time. Through watershed-scale modifications of vegetation cover and climate, hydrological and sediment regimes are altered, resulting in changes in channel form. These same modifications can affect the characteristics of individual hydrological events and the responses of rivers to these events. Moreover, humans have directly altered rivers by reconfiguring the form of channels, by reshaping floodplains, and by constructing barriers, such as dams, along rivers. These activities have been pursued through attempts to manage rivers to achieve specific societal goals. Over the past several decades, management strategies have arisen that focus explicitly on environmental goals. Although such strategies seek to enhance environmental quality, in many cases they still involve active manipulation of rivers. Proper understanding of river dynamics is essential for effective river management. Past management efforts that have failed to fully consider how rivers respond to human intervention have often led to unanticipated and undesired consequences. Only by understanding how rivers respond to change can management attain the intended goals while avoiding negative consequences.