Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychiatric disorder characterised by recurrent intrusive thoughts, impulses and images and/or repetitive rituals or mental acts, which affects between 2 and 4% of children and adolescents. Reference Geller1–Reference Zohar3 OCD has a number of similarities to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by impaired communication, impaired reciprocal social interaction and restricted and repetitive interests or patterns of behaviour, which affects more than 2.7% of the general child and adolescent population. 4,Reference Lai, Lombardo and Baron-Cohen5 The phenotypical similarities between the two disorders include repetitive and stereotypical behaviours, the need for sameness and inflexibility. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6 Touching, tapping, ordering and hoarding are all repetitive behaviours found in both ASD and OCD. Reference Zandt, Prior and Kyrios7–Reference Cath, Ran, Smit, van Balkom and Comijs10 Although relatively similar, the repetitive behaviours serve different functions in these two conditions. Reference Murray, Jassi, Mataix-Cols, Barrow and Krebs11–Reference South, Ozonoff and McMahon13 In OCD, typically the behaviour is carried out to relieve anxiety, is egodystonic and overall is associated with distress and anxiety, whereas in ASD, the behaviour is not usually associated with distress, but rather intense preoccupations with new objects or idiosyncratic circumscribed interests. Reference Murray, Jassi, Mataix-Cols, Barrow and Krebs11–Reference South, Ozonoff and McMahon13 The overlap between the two disorders led to the nosological debate as to whether OCD had been correctly placed as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV-TR, and, in more recent classifications, OCD has been moved under the Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders category’. Reference Bartz and Hollander14,15

Research has suggested shared underlying mechanisms between OCD and ASD. Reference Leyfer, Folstein, Bacalman, Davis, Dinh and Morgan16–Reference Baribeau, Doyle-Thomas, Dupuis, Iaboni, Crosbie and McGinn18 In both ASD and OCD, neuroanatomical findings indicate that thinner cortical regions are associated with an increase in social deficits. Reference Baribeau, Dupuis, Paton, Hammill, Scherer and Schachar19 This is supported by previous studies that found reduced temporal/parietal cortical thickness in patients diagnosed with ASD or OCD. Reference van Rooij, Anagnostou, Arango, Auzias, Behrmann and Busatto20,Reference Boedhoe, Schmaal, Abe, Alonso, Ameis and Anticevic21 Abnormalities with the prefrontal cortex have also been identified in both OCD and ASD. Reference Kennedy, Redcay and Courchesne22–Reference Sakai, Narumoto, Nishida, Nakamae, Yamada and Nishimura24 Genetic factors further emphasise the association between the two disorders, with some studies having found that family members of individuals with ASD are more likely to demonstrate compulsive personality traits. Reference Hanna, Himle, Curtis and Gillespie25 A systematic review and meta-analysis found that 10% of parents of children with ASD had a diagnosis of OCD, which was elevated compared with OCD prevalence in the general population. Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters26–28 Ozyurt and colleagues also found that mothers of children and adolescents with OCD scored significantly higher on the Autism Quotient compared with mothers of the control group, suggesting further overlap between these conditions. Reference Ozyurt and Besiroglu29

OCD and ASD commonly co-occur in children and adolescents. A systematic review and meta-analysis completed by Aymerich and colleagues in 2024 identified a pooled prevalence rate of ASD in children, adolescents and young adults with OCD of 9.46%. Reference Aymerich, Pacho, Catalan, Yousaf, Perez-Rodriguez and Hollocks30 To the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review and meta-analysis to date has evaluated both ASD diagnosis and traits within a population of children and adolescents with OCD. Reference Aymerich, Pacho, Catalan, Yousaf, Perez-Rodriguez and Hollocks30

Functional impairment is associated with both ASD and OCD individually in the paediatric population, but there has been less exploration of the impact on functioning when both conditions co-exist. Comorbid OCD and ASD is associated with an increase in functional impairment in school, at home and in social aspects of life when compared with children and adolescents with OCD only. Reference Aymerich, Pacho, Catalan, Yousaf, Perez-Rodriguez and Hollocks30,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White31 The additive effects of comorbidities may be associated with an increase in functional impairment. Reference Caron and Rutter32 To date, the impact of comorbid ASD or ASD traits on global functioning in children and adolescents with OCD has not been adequately explored.

The aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis are:

-

(a) To provide a prevalence estimate of ASD traits and diagnosis in children and adolescents with a diagnosis of OCD.

-

(b) To compare ASD trait severity between child and adolescent OCD populations and control groups/normative data.

-

(c) To examine whether the severity of OCD symptoms is related to the severity of ASD traits or presence of a diagnosis in children and adolescents diagnosed with OCD.

-

(d) To examine whether the severity of comorbid ASD traits or presence of a diagnosis in children and adolescents diagnosed with OCD impact negatively on their global functioning.

Method

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO before data collection (number: CRD42018106411), and details can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10936.

Search strategy

PRISMA guidelines were followed throughout this systematic review. Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow33 Electronic searches were carried out on 25 February 2025, using Embase, Medline and PsycINFO, with the keywords of ‘obsessive compulsive disorder,*’ ‘Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder/’ ‘ocd,’ ‘autis,*’ ‘Asperger,*’ ‘ASD,’ ‘child,*’ ‘adoles,*’ ‘p?diatric,’ ‘youth,’ ‘juvenile,’ ‘teen,*’ ‘infant,’ ‘young people’ and ‘young person.’ Thesaurus searches were also used for the main keywords, including ‘adolescent’, ‘ASD’ and ‘obsessive-compulsive disorder’. Boolean operators OR and AND were used as appropriate. The language for the searches was restricted to English. The publication type was restricted to journal article, but no restrictions were set for the date of publication. The search was also restricted to human studies. The author (C.T.) conducted a systematic search of the literature alongside a medical librarian. Screening of titles, abstracts and full text was performed by two authors (C.T. and P.L.) working independently and in duplicate. Interrater agreement was calculated with Cohen’s κ coefficient. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers until a consensus was reached, or by consultation with a third senior author (M.K.) when necessary. The search was completed by manually searching through previous literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analysis on this topic.

Eligibility criteria

For this review, the participants had to be up to 18 years of age and have a diagnosis of OCD (either according to the ICD or the DSM). Papers that evaluated (a) ASD or associated traits in young people with a diagnosis of OCD, (b) the relationship between OCD severity and ASD trait severity/diagnosis or (c) the relationship between ASD trait severity/diagnosis and global functioning in children and adolescents diagnosed with OCD, were included in this review. A diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder was also included as falling under the umbrella of ASD. Any study design where this data could be extracted or calculated were included. Papers investigating disorders related to OCD, including body dysmorphic disorder, compulsive skin picking, trichotillomania and hoarding disorder, were excluded. In addition, papers were excluded if the sample included adults where data about the adolescent sample could not be extracted and where this data was not available from the authors. Papers that were not written in English, poster abstracts and dissertations were also excluded. If there was a potential for sample overlap between two or more studies, where original authors did not respond, author C.T. presumed sample overlap between the studies and excluded the study with the smaller sample size.

Strategy for data extraction, synthesis and statistics

Data extraction commenced on 28 May 2025. The authors (C.T. and P.L.), working independently and in duplicate, extracted data from the identified studies. Interrater agreement was calculated with Cohen’s κ coefficient. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus and by consulting a senior author (M.K.). Where specific data was not available from the manuscript, author C.T. contacted authors of the original studies to request the required data. Authors P.L. and M.S. completed the methods of data synthesis and statistics described below.

Prevalence of ASD diagnosis

Prevalence of ASD diagnosis was reported as a percentage, calculated by using the total number of children and adolescents diagnosed with comorbid ASD as the numerator and the total OCD sample as the denominator.

In regards to the meta-analysis, for the summary effect of the ASD diagnosis prevalence, unadjusted prevalence rates were calculated based on the information of crude numerators and denominators provided by individual studies. Prevalence was reported with 95% confidence intervals and the degree of heterogeneity was estimated by I 2-statistics. Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page34 As considerable heterogeneity was expected, the random effects model was primarily employed, but an estimate based on common effects model was also presented. Meta-analytic calculations were performed with R version 4.3.1 on macOS.

We aimed to assess publication bias with funnel plots and Egger’s regression test, Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder35 provided that a reasonable number of studies were available, defining this minimum as ten studies. Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page34

Prevalence of ASD traits

ASD traits were reported as the percentage of participants scoring over a specified cut-off score in the questionnaires used to screen for or assess ASD. Questionnaires used to measure ASD traits included the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), Social Responsiveness Scale – Version 2 (SRS-2), Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ), Autism Quotient and Children’s Social Behaviour Questionnaire (CSBQ). Reference Constantino and Volkmar36–Reference Hartman, Luteijn, Serra and Minderaa42

Comparison of ASD traits between OCD samples and controls

Aggregate mean scores of the relevant ASD questionnaires were compared between the OCD group and the control group (those individuals without a diagnosis of OCD).

Exploring the effect of comorbid ASD diagnosis on OCD severity

Aggregate mean scores of the Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) in an OCD-only group were compared with comorbid group diagnosed with OCD and ASD. Reference DerSimonian and Laird43,Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King and Goodman44

For comparisons above, a pairwise meta-analysis was conducted to provide a more comprehensive description and visualisation of score differences between groups in the questionnaires used to measure ASD traits or OCD symptoms. The effect size used was the mean difference. However, if included studies used different scales, the standardised mean difference (SMD), expressed as Hedges’ adjusted g-statistic, was estimated. The pooling of studies utilised the standard inverse variance weighting method. Considering the anticipated heterogeneity among the studies, which was quantified by the I 2-statistic, Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page34 the Der-Simonian and Laird random effects model was consistently employed. Reference DerSimonian and Laird43,Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King and Goodman44 Meta-analytic calculations were performed with R Version 4.3.1 on macOS.

Reviewing the effect of comorbid ASD trait severity on OCD severity

Correlation of aggregate mean scores of the relevant questionnaires used to measure ASD and aggregated mean scores of the CY-BOCS questionnaire (used to measure OCD) were described. Reference DerSimonian and Laird43,Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King and Goodman44

Reviewing the effect comorbid ASD trait severity on functional impairment

Correlation of aggregate mean scores of relevant ASD questionnaires and questionnaires used to measure functional impairment (Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) score and Child OCD Impact Scale – Parent Version (COIS-P)) Reference Shaffer, Gould, Brasic, Ambrosini, Fisher and Bird45,Reference Piacentini, Peris, Bergman, Chang and Jaffer46 were described. More details on the questionnaires used for ASD, OCD and functional impairment can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Analysing the effect of comorbid ASD diagnosis on functional impairment

Aggregate mean scores of questionnaires used to measure functional impairment were compared between an OCD-only group and a comorbid group diagnosed with OCD and ASD.

Quality assessment

To assess quality of the studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale adaptions for case–control, cohort and cross-sectional studies were used. Reference Wells, Shea, O’Connell, Peterson, Welch and Losos47,Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil48 To assess the quality of any randomised control trials, the Jadad score was used. Reference Jadad, Moore, Carroll, Jenkinson, Reynolds and Gavaghan49 The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was not used as this paper was not examining interventions or treatments. Quality was assessed independently and in duplicate by two authors (C.T. and P.L.), with interrater agreement calculated with Cohen’s κ coefficient. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers (C.T. and P.L.) and, when necessary, consultation with a senior author (M.K.).

Results

Identified studies

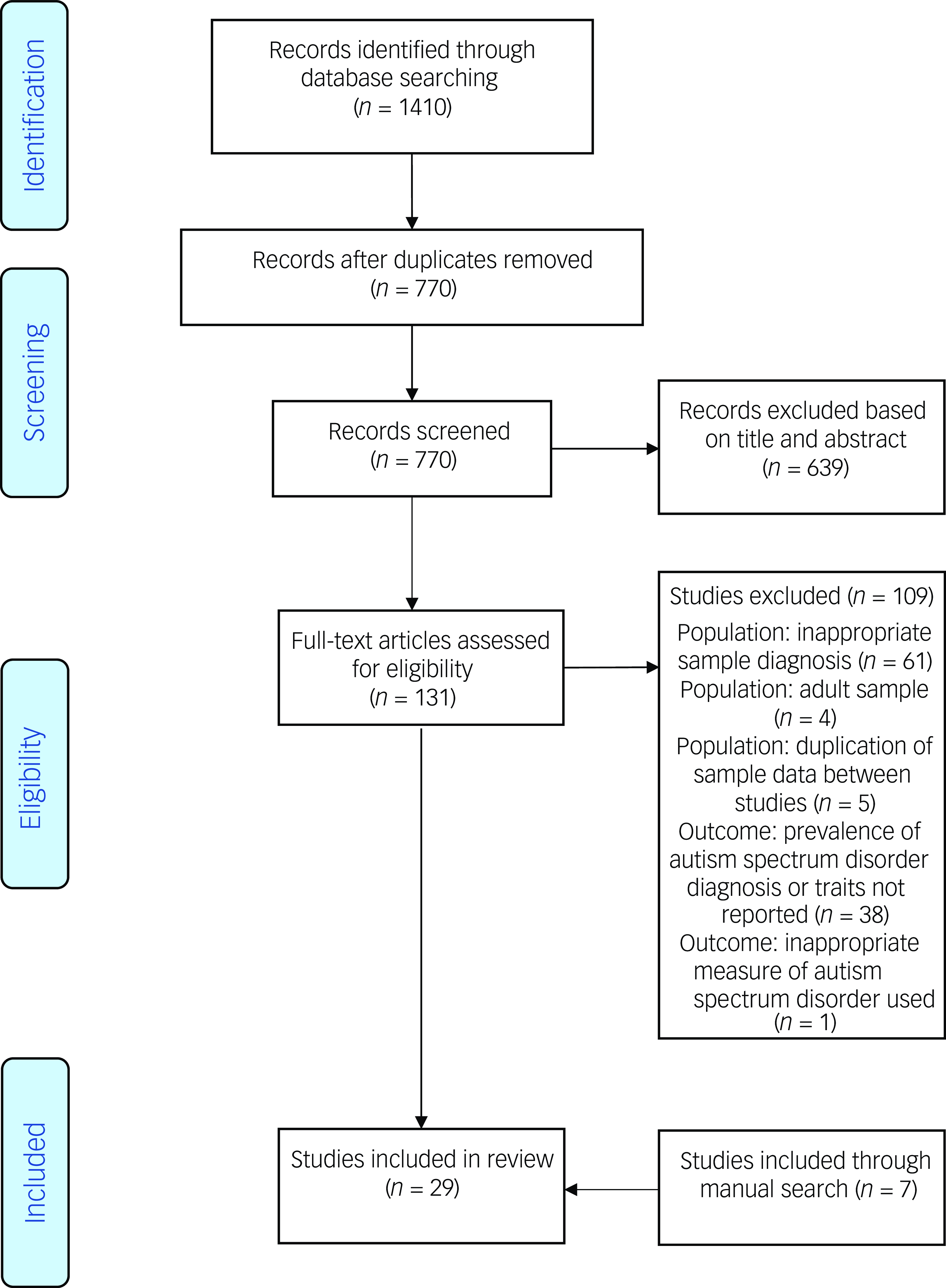

A total of 1410 studies were identified through the electronic search, and 770 studies remained once duplicates were removed. The remaining studies were screened based on their title and abstract. After screening 131 full-text studies, we excluded 109 studies (as shown in Fig. 1), including five studies displaying potential sample duplication. Reference Murray, Jassi, Mataix-Cols, Barrow and Krebs11,Reference Baribeau, Doyle-Thomas, Dupuis, Iaboni, Crosbie and McGinn18,Reference Baribeau, Dupuis, Paton, Hammill, Scherer and Schachar19,Reference Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Nissen, Hybel, Ivarsson and Thomsen50,Reference Choi, Vandewouw, Taylor, Stevenson, Arnold and Brian51 This left 22 studies for inclusion. Seven additional studies were included through manual searches, meaning a total of 29 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Weidle, Melin, Drotz, Jozefiak and Ivarsson12,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White31,Reference Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Nissen, Hybel, Ivarsson and Thomsen50,Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52–Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76 Cohen’s κ coefficient indicated near perfect agreement for screening (κ = 0.95) and there were no conflicts in data extraction. From the 29 studies where data extraction was possible, 13 were case–control studies, ten cross-sectional studies, four cohort studies and two randomised controlled trials (full details available in Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 1 Journal identification process.

Of the 29 studies included in this review, 13 studies reported on the prevalence of ASD diagnosis in children and adolescents diagnosed with OCD, eight studies reported on the prevalence of ASD traits in this population scoring above a specified clinical cut-off, and seven studies compared ASD measure scores in an OCD sample versus a control group or normative data.

The SCQ was the most commonly administered questionnaire used to measure ASD traits or to support an ASD diagnosis, followed by the ASSQ. Five studies used the SCQ Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Weidle, Melin, Drotz, Jozefiak and Ivarsson12,Reference Ozyurt and Besiroglu29,Reference Choi, Vandewouw, Taylor, Arnold, Brian and Crosbie63,Reference Mahjoob, Cardy, Penner, Anagnostou, Andrade and Crosbie75 and four studies used the ASSQ, Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52,Reference Perez-Vigil, Ilzarbe, Garcia-Delgar, Morer, Pomares and Puig74,Reference Hojgaard, Arildskov, Skarphedinsson, Hybel, Ivarsson and Weidle77 three studies used the SRS, Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Sturm, Rozenman, Chang, McGough, McCracken and Piacentini56 one of which used the second edition of the SRS (SRS-2). Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53 One study used both the SCQ and SRS. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6 Two studies used the Autism Quotient Reference Oyku Memis, Sevincok, Dogan, Baygin, Ozbek and Kutlu58,Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76 and one study used the CSBQ. Reference Wolters, de Haan, Hogendoorn, Boer and Prins57

Prevalence of ASD diagnosis

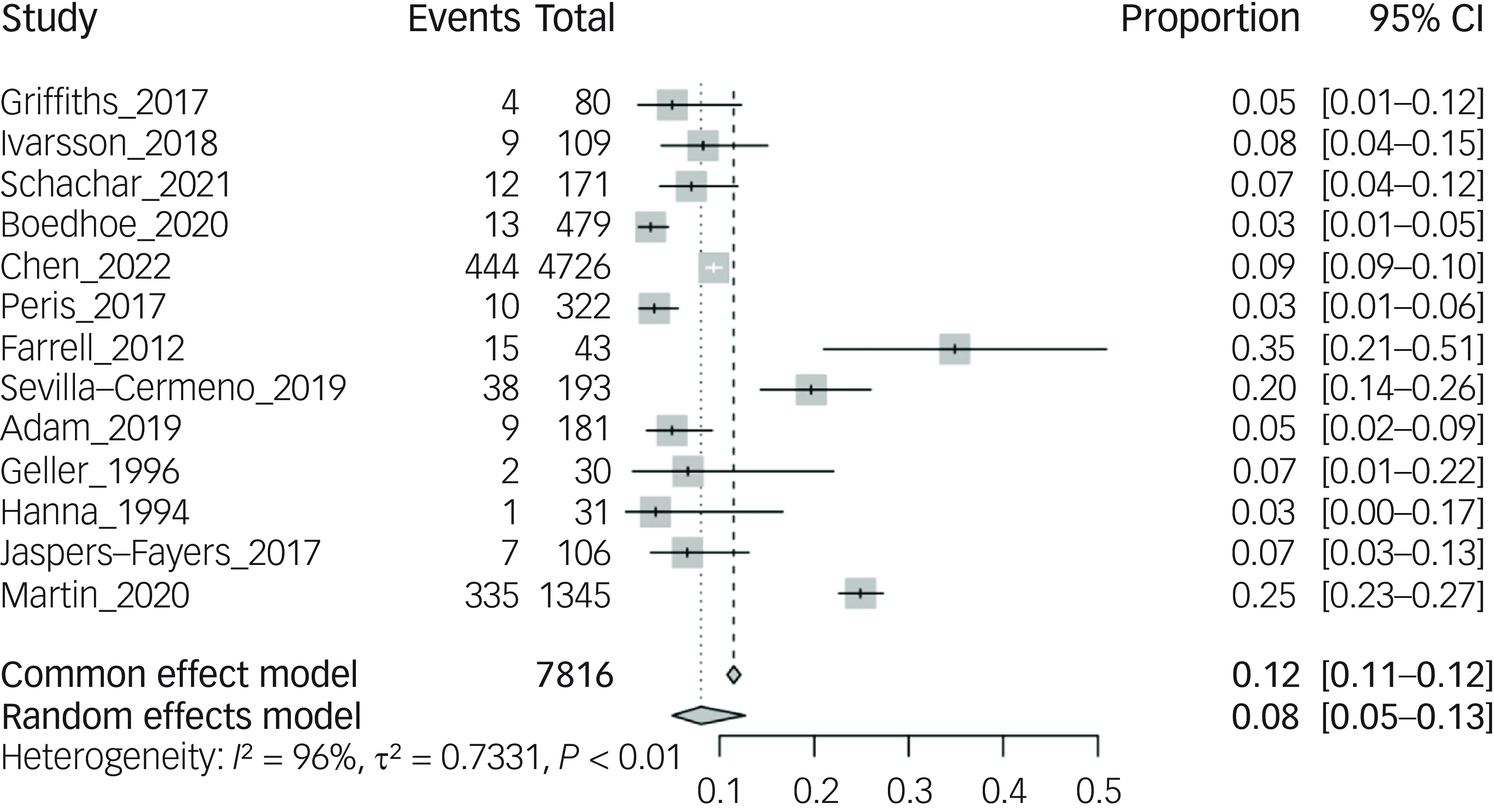

In the 13 studies that measured the prevalence of ASD diagnosis in 7816 children and adolescents with OCD (51.8% male), prevalence rates ranged from 2.71 to 34.9%. Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59,Reference Schachar, Dupuis, Anagnostou, Georgiades, Soreni and Arnold60,Reference Boedhoe, van Rooij, Hoogman, Twisk, Schmaal and Abe65–Reference Sevilla-Cermeño, Isomura, Larsson, Åkerstedt, Vilaplana-Pérez and Lahera72,Reference Chen, Tsai, Liang, Cheng, Su and Chen78 The pooled mean prevalence, using a random effects model, was 8.0% (95% CI 5.0–13.0%, P < 0.01). As displayed in Fig. 2, three of the studies appear to be outliers compared with the ten other studies, which may be explained by sample variation. There were not enough data to examine gender difference specific to ASD prevalence in this OCD population; however, four studies reported either increased prevalence rates within their male OCD population or a higher proportion of males in those diagnosed with ASD (Supplementary Table 3). Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59,Reference Schachar, Dupuis, Anagnostou, Georgiades, Soreni and Arnold60,Reference Hanna68,Reference Peris, Rozenman, Bergman, Chang, O’Neill and Piacentini71

Fig. 2 Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in children and adolescent obsessive–compulsive disorder samples.

Prevalence of significant ASD traits

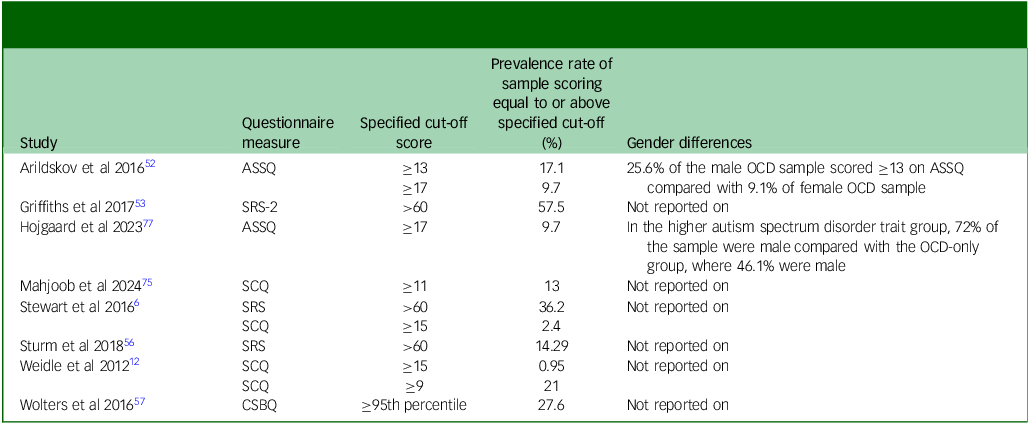

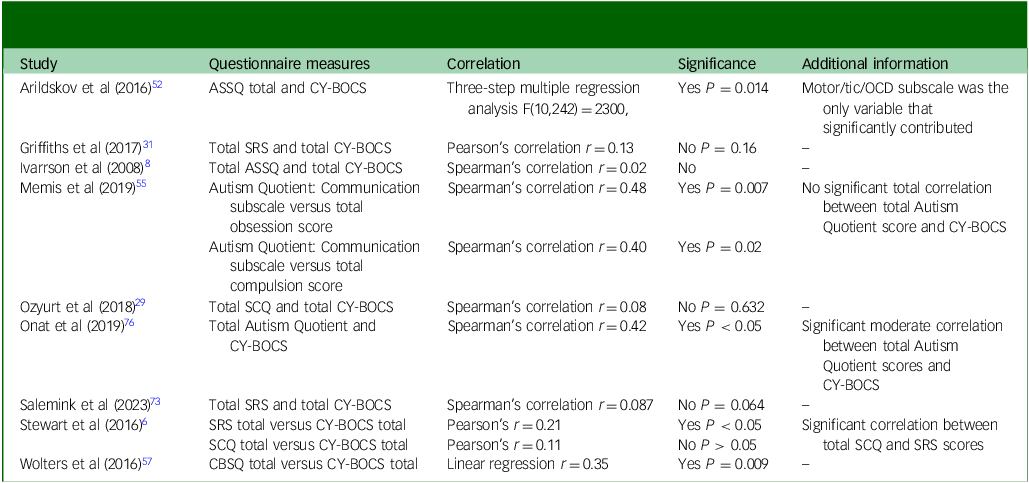

Eight studies reported on the prevalence of significant ASD traits as per clinical cut-off scores on the SCQ, SRS, ASSQ and CSBQ. Different definitions of trait cut-offs and scales were used across the studies, making it challenging to summarise and review the data both qualitatively and quantitatively. Prevalence rates are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1 Prevalence rates of significant autism spectrum disorder traits in children and adolescents diagnosed with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

ASSQ, Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire; SRS-2, Social Responsiveness Scale - Version 2; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; CSBQ, Children’s Social Behaviour Questionnaire.

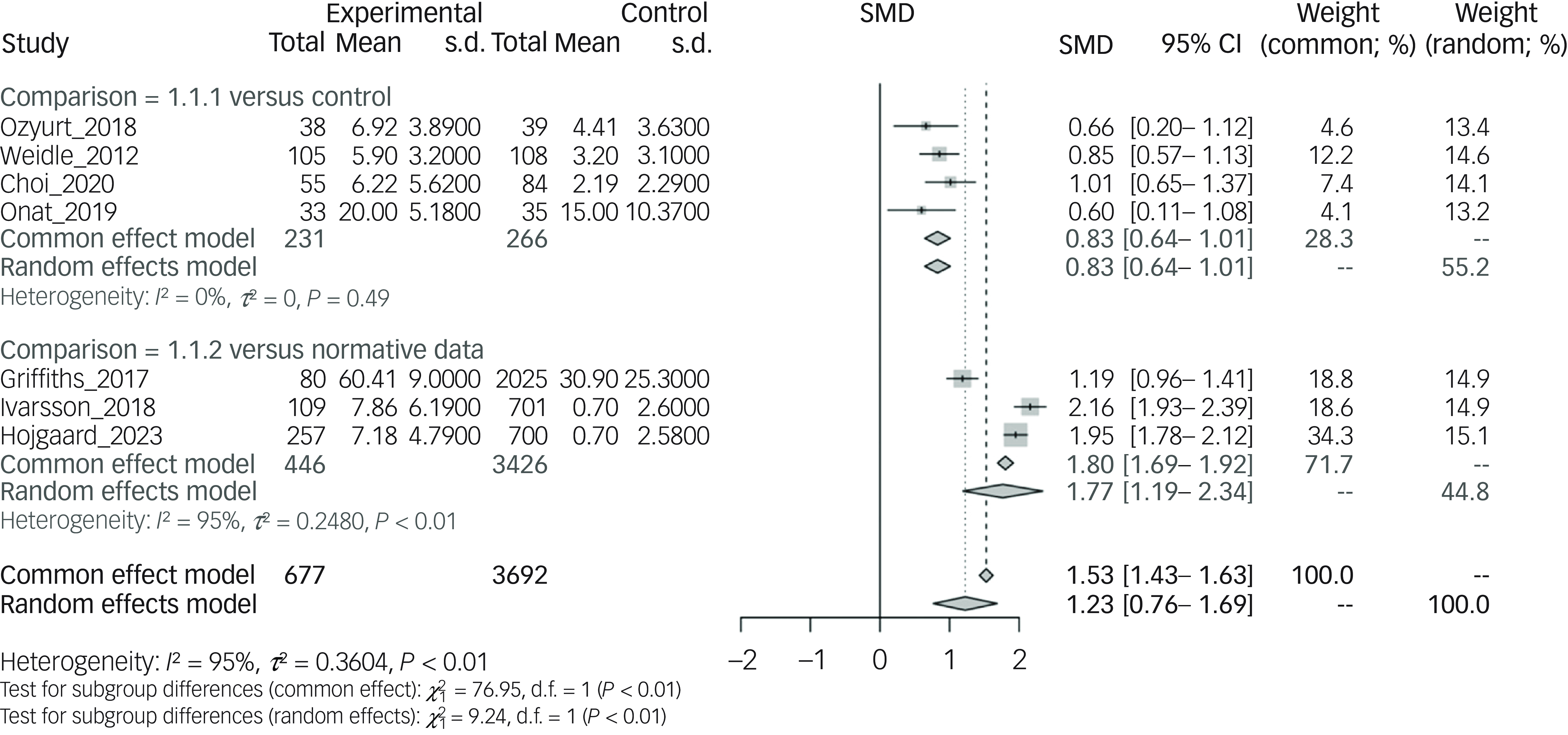

Comparisons of ASD questionnaire scores between OCD group and controls

In eight of the 29 studies, data from an OCD group were compared with a normotypical control group or normative data. Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Weidle, Melin, Drotz, Jozefiak and Ivarsson12,Reference Ozyurt and Besiroglu29,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Choi, Vandewouw, Taylor, Arnold, Brian and Crosbie63,Reference Perez-Vigil, Ilzarbe, Garcia-Delgar, Morer, Pomares and Puig74,Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76,Reference Hojgaard, Arildskov, Skarphedinsson, Hybel, Ivarsson and Weidle77 Only seven of the studies could be included in the meta-analysis, as the s.d. for mean scores in one study were not available. Reference Perez-Vigil, Ilzarbe, Garcia-Delgar, Morer, Pomares and Puig74 In all studies, participants with an OCD diagnosis had higher scores in the scale measuring ASD symptom severity (overall SMD of 1.23, 95% CI 0.76–1.69) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Comparison of autism spectrum disorder measure aggregate mean scores of obsessive–compulsive disorder samples versus control samples or normative data. SMD, standardised mean difference.

Four studies compared an OCD group with a control group consisting of normotypical children and adolescents. These studies included a total of 266 participants; ASD symptom severity was measured with the SCQ questionnaire in three studies and the Autism Quotient in one study. Control groups had significantly lower ASD symptom severity when compared with OCD groups, with an overall SMD of 0.83 (95% CI 0.64–1.01), as displayed on the forest plot in Fig. 3 (Comparison: 1.1.1 versus control).

As for the comparison with normative data, three studies including a total of 446 participants used either the SRS-2 or ASSQ questionnaires as a measure of ASD symptom severity. Normative data reported significantly lower ASD symptom severity compared with the OCD groups (SMD 1.77, 95% CI 1.19–2.34) as illustrated in Fig. 3 (Comparison: 1.1.2. versus normative data). There was not enough data to examine generalised gender differences; however, Ivarsson and colleagues reported that males obtained statistically significant higher total SCQ scores compared with females (P = 0.006). Reference Ivarsson and Melin8

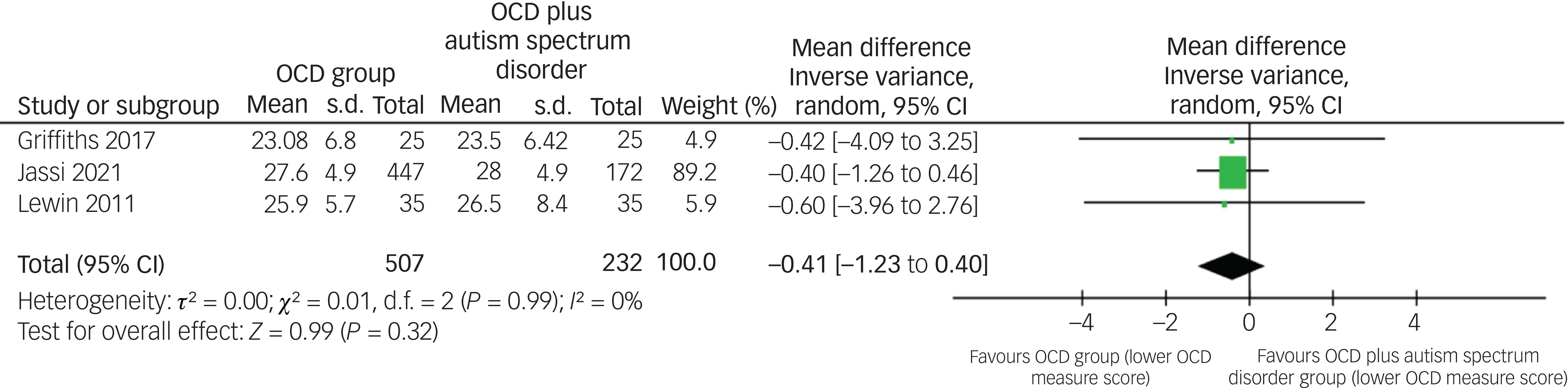

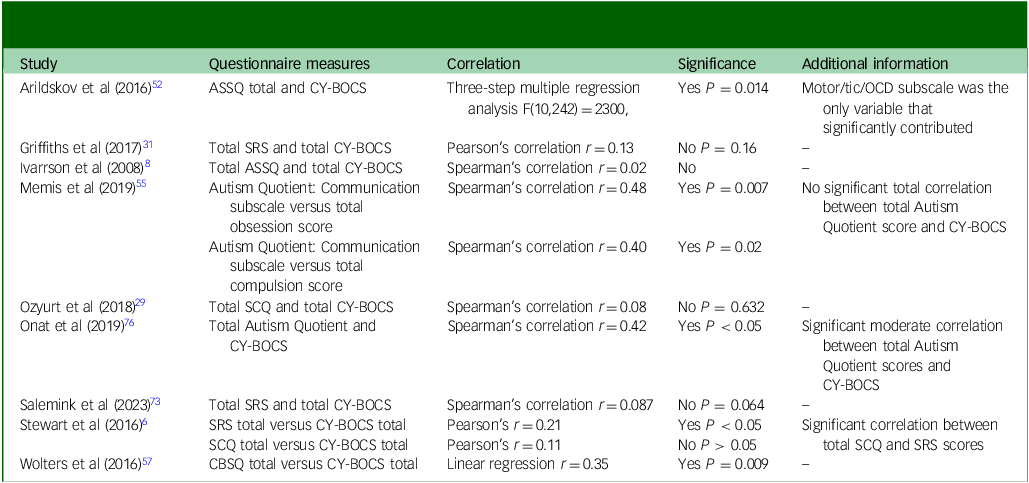

Correlation between OCD severity and the severity of ASD traits

Nine of the studies included in the review reported on the correlation between OCD severity and the severity of ASD traits (Table 2). Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Ozyurt and Besiroglu29,Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Memiş, Sevincok, Doğan, Kutlu, Çakaloz and Sevinçok55,Reference Wolters, de Haan, Hogendoorn, Boer and Prins57,Reference Salemink, Hagen, de Haan and Wolters73,Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76 ASD traits and OCD severity were measured by questionnaire scores. ASD traits were measured by the SCQ, SRS, ASSQ, Autism Quotient and CBSQ. OCD severity was measured with the CY-BOCS. More details on the questionnaires used can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2 Correlation between measures of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism spectrum disorder in children and young people with a diagnosis of OCD

ASSQ, Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire; CY-BOCS, The Children’s Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; CBSQ, Children’s Social Behaviour Questionnaire.

Four of the studies found that there was no significant correlation between questionnaire scores used to measure the severity of OCD symptoms and measures assessing ASD traits. Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Ozyurt and Besiroglu29,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Salemink, Hagen, de Haan and Wolters73

Wolters and colleagues found a weak correlation between mean CY-BOCS scores and the CSBQ scores (r = 0.35, P = 0.009). Reference Wolters, de Haan, Hogendoorn, Boer and Prins57 Stewart and colleagues found a weaker correlation between mean CY-BOCS scores and mean total SRS scores (r = 0.21, P < 0.05), and between mean CY-BOCS score and the autistic mannerisms subscale of the SRS (r = 0.21, P < 0.05). The correlation between mean CY-BOCS and SCQ score was not significant. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6

Onat and colleagues found a moderate correlation between mean CY-BOCS scores and Autism Quotient scores (r = 0.42, P < 0.05). Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76 Arildskov and colleagues also found a significant correlation between mean CY-BOCS scores and ASSQ. However, the motor/tic/OCD subscale was the only variable that significantly contributed to this. The autistic style and social difficulties subscales did not contribute significantly, as these autism specific symptoms did not significantly correlate with the mean CY-BOCS score. Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52

In the 2019 study by Memis and colleagues, there was no significant correlation found between mean CYBOCS score and mean total Autism Quotient score; however, the study did find that that there was a significant correlation between the mean total compulsion score of the CY-BOCS score and the communication subscale of the Autism Quotient (r = 0.40, P = 0.02). Reference Memiş, Sevincok, Doğan, Kutlu, Çakaloz and Sevinçok55

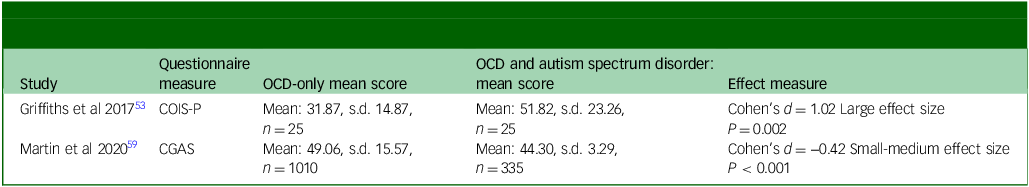

The impact of ASD diagnosis on the severity of OCD

Three studies reported on the impact of ASD diagnosis on the severity of OCD by comparing mean OCD scores in an OCD-only group to an OCD group with comorbid ASD. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White31,Reference Lewin, Wood, Gunderson, Murphy and Storch62 The CY-BOCS was used as a measure of OCD severity in each study (Fig. 4). No difference was found between the two groups (mean difference: −0.41; 95% CI −1.23 to 0.40) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Comparison of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) measure aggregate mean scores of OCD samples and comorbid OCD and autism spectrum disorder samples.

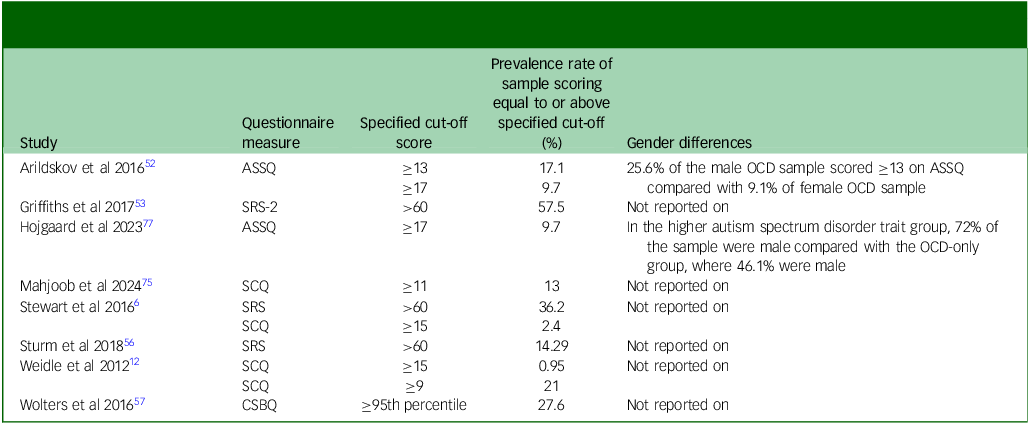

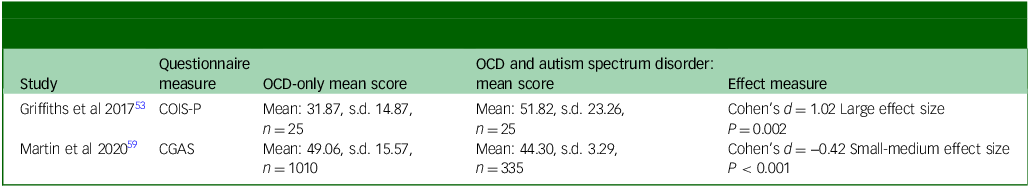

The impact of ASD trait severity or diagnosis on the global functioning of OCD samples

Three studies reported on the impact of significant ASD traits or diagnosis on the global functioning of individuals with OCD. Two studies used the COIS-P to measure the impact of functioning and one study used the CGAS score. Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White31,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59

Griffiths and colleagues found that the mean COIS-P impact score was weakly correlated with the mean SRS total t-score (r = 0.23, P = 0.02). The study reported that SRS total t-score was a significant predictor of OCD-related functional impairment. Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53

Griffiths and colleagues also found that when comparing total psychosocial impact on functioning between a comorbid OCD and ASD group and an OCD-only group, independent group t-tests showed significant differences between the groups t Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder35 = 3.41, P = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 1.02), demonstrating a large effect size. This indicated that there was a greater impairment in functioning in the comorbid group. Significant differences between the groups were also demonstrated when comparing specific aspects of the COIS-P, including school functioning, social functioning and home and family activities (Table 3). Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White31 Martin and colleagues also reported that participants with comorbid OCD and ASD presented with greater functional impairment when measured by the CGAS score (mean: 44.30) compared with the OCD-only group (mean: 49.06, Cohen’s d = 0.42, P < 0.001), demonstrating a small to medium effect size (Table 3). Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59 As only two studies directly compared aggregate mean questionnaire scores between groups, meta-analysis was not performed.

Table 3 Comparison of global functioning questionnaire scores between obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) only and comorbid obsessive–compulsive disorder and autism spectrum disorder groups

COIS-P, Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale (parent version); CGAS, Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

Quality assessment

There was variation in the study designs included within this systematic review and meta-analysis. The majority of studies used a case–control design, three studies used a cross-sectional design, cross-sectional data was also taken from a randomised controlled trial in one study and three studies were cohort studies. The number of randomised controlled trials was not important as the current systematic review and meta-analysis was not examining an intervention. Cohen’s κ coefficients indicated near perfect agreement for quality assessment (κ = 0.94). The quality assessment of each study is detailed in Supplementary Table 4.

Overall, the quality of studies included was good, particularly for the comparability, exposure and outcome domains for each study (Supplementary Table 4). All of the case–control studies lacked information on non-responders in both case and control groups and did not report whether the characteristics of non-responders matched those of participants included in the study, which may have contributed to non-response bias. Six studies had particularly small sample sizes, which may limit generalisability. Reference Sturm, Rozenman, Chang, McGough, McCracken and Piacentini56,Reference Oyku Memis, Sevincok, Dogan, Baygin, Ozbek and Kutlu58,Reference Geller, Biederman, Griffin, Jones and Lefkowitz67,Reference Hanna68,Reference Perez-Vigil, Ilzarbe, Garcia-Delgar, Morer, Pomares and Puig74,Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76 None of the cross-sectional studies used sample size calculations.

Discussion

Prevalence of ASD diagnosis and traits in OCD

Our systematic review and meta-analysis, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to report on the prevalence of both ASD diagnosis and traits in children and adolescents up to 18 years of age with a diagnosis of OCD, as well as comparing trait severity between this OCD sample and control samples. We identified 13 studies reporting on the prevalence of ASD diagnosis within this pooled OCD sample of 7816 patients, the largest pooled sample to date, finding a pooled prevalence rate of 8.0% (95% CI 5.0–13.0%, P < 0.01). The findings of this study also suggested an increase in prevalence of ASD traits in children and adolescents with OCD when compared with the general paediatric population.

Our review supports other previous suggestions of comorbidity between the two diagnoses. Reference Aymerich, Pacho, Catalan, Yousaf, Perez-Rodriguez and Hollocks30,Reference Lai, Kassee, Besney, Bonato, Hull and Mandy79 Aymerich and colleagues have previously completed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of ASD diagnosis in a population of children and young people with OCD, reporting a pooled prevalence rate of 9.46%. The elevated prevalence of ASD traits and diagnosis within the OCD population may be explained by shared underlying mechanisms of both disorders. Reference Leyfer, Folstein, Bacalman, Davis, Dinh and Morgan16–Reference Baribeau, Doyle-Thomas, Dupuis, Iaboni, Crosbie and McGinn18 Both neuroanatomical findings and genetic studies support this finding, including a systematic review and meta-analysis identifying that 10% of parents of children with ASD had a diagnosis of OCD, Reference Schnabel, Youssef, Hallford, Hartley, McGillivray and Stewart27 which is elevated compared with the prevalence of OCD within the general population. Reference van Steensel, Bögels and Perrin17,Reference Baribeau, Doyle-Thomas, Dupuis, Iaboni, Crosbie and McGinn18,Reference van Rooij, Anagnostou, Arango, Auzias, Behrmann and Busatto20,Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters26,Reference Schnabel, Youssef, Hallford, Hartley, McGillivray and Stewart27

In our review, ASD prevalence rates were similar between studies, ranging from 2.71 to 9.39% in most studies. Three studies found higher prevalence rates of 19.7, 24.9 and 34.9%, which are outliers compared with the other ten studies. Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59,Reference Farrell, Waters, Milliner and Ollendick66,Reference Sevilla-Cermeño, Isomura, Larsson, Åkerstedt, Vilaplana-Pérez and Lahera72 This may be explained by differences in the representativeness of the samples within these studies. Martin and colleagues reviewed records from children and adolescents who presented to South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust who had a diagnosis of OCD and/or ASD. The OCD service provided by South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust is a national and specialist OCD service that assesses and treats children and adolescents who have not responded to standard treatment for OCD by community child and adolescent mental health services in England. It is possible that the prevalence rates were higher in this sample because having comorbid ASD would likely impact the treatment response of these individuals, meaning they required referral to this specialist service. Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59 Sevilla-Cermeno and colleagues reviewed the records of all individuals living in Sweden between a specified time period, which may be more representative of the general community than other studies identified that reported on clinical samples. Reference Sevilla-Cermeño, Isomura, Larsson, Åkerstedt, Vilaplana-Pérez and Lahera72

ASD trait prevalence was not included in the meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity between the questionnaire measures used to determine the percentage of participants scoring over clinical-cut-off for ASD traits. Particularly regarding the ASSQ and SRS-2, two different clinical cut-offs were used to determine whether moderate or severe traits were present. Significant differences were also seen in prevalence rates of significant ASD traits above the related cut-off, depending on the questionnaire measure used. Prevalence rates of studies using the SCQ found prevalence rates of between 1.0 and 14% compared with those using the ASSQ, SRS-2 and CSBQ, where rates ranged from 14.3 to 48.0%. This may be explained by the differences in sensitivity and specificity between the questionnaires. Regarding the SCQ, a meta-analysis by Chestnut and colleagues found that differences in sampling affected the accuracy of the SCQ as a screening tool. Reference Jassi, Vidal-Ribas, Krebs, Mataix-Cols and Monzani61 Particularly, clinic-referred samples have been found to perform poorer in classifying those with ASD, as was the case with many of the samples included in our systematic review. Reference Hollocks, Casson, White, Dobson, Beazley and Humphrey80 Other research has suggested that reducing the cut-off to 11 rather than 15 as being most accurate in children aged 4–12 years, with Stewart and colleagues questioning whether the yes/no responses in the SCQ were able to identify the milder spectrum of ASD traits. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Barnard-Brak, Brewer, Chesnut, Richman and Schaeffer81,Reference Berument, Rutter, Lord, Pickles and Bailey82 Conversely, both studies by Griffiths and colleagues and Stewart and colleagues raised concerns as to whether the SRS is too sensitive a measure to differentiate OCD from ASD, and is less effective in assessing the function of the behaviour, but rather captures symptom overlap. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53 All these considerations may be related to the large discrepancy in the prevalence of significant ASD traits in the OCD samples between questionnaires.

The impact of ASD trait severity or diagnosis on the severity of OCD

Our review explored whether there was an association between the severity of OCD and ASD traits within the child and adolescent OCD population. Only three out of the nine studies that reported on this found that there was a significant correlation between the two when focusing on total questionnaire scores (Table 2). Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52,Reference Wolters, de Haan, Hogendoorn, Boer and Prins57,Reference Onat, Nas Ünver, Şenses Dinç, Çöp and Pekcanlar Akay76 Meta-analysis also supported this lack of evidence when comparing OCD scores in an OCD only group with a comorbid OCD and ASD group, but only three studies provided data (Fig. 4). Amongst the studies, Arildskov and colleagues commented that the motor/tic/OCD subscales of the ASSQ were the only variables that significantly correlated with OCD severity as measured by CY-BOCS. Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52 This supports comments made in some studies as to whether the questionnaire measures used could successfully differentiate between the repetitive and stereotypical behaviours seen in ASD versus the repetitive ritualistic behaviours present in OCD. Reference Ozyurt and Besiroglu29,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53 In contrast, a correlation between only the communication subscale of the Autism Quotient measure and both lifetime obsessions and compulsions were reported, suggesting correlation is not only related to the subscales associated with repetitive behaviour. Reference Memiş, Sevincok, Doğan, Kutlu, Çakaloz and Sevinçok55 Again possible limitations of the SRS questionnaire to assess the function of the behaviour measured or to capture the symptom overlap between the two conditions need to be considered. Reference Stewart, Cancilliere, Freeman, Wellen, Garcia and Sapyta6

The impact of ASD trait severity or diagnosis on global functioning in OCD

Although there were not enough studies to perform a meta-analysis, our review suggests that increased ASD traits or diagnosis in children and adolescents with OCD are associated with an increase in functional impairment across school, home and social settings. Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White31,Reference Griffiths, Farrell, Waters and White53,Reference Martin, Jassi, Cullen, Broadbent, Downs and Krebs59 This is also supported by Aymerich and colleagues review who concluded that there were high rates of functional impairment in comorbid diagnosis of ASD and OCD, but were not able to use meta-analysis to support this. Reference Aymerich, Pacho, Catalan, Yousaf, Perez-Rodriguez and Hollocks30 As assessment of functioning is important for both the diagnosis and monitoring of OCD, further research in this area would be of significant benefit.

Limitations

Limitations highlighted in studies of the current systematic review and meta-analysis included the reliance on parental reporting in the measures used, which may skew the data. The lack of information on responders versus non-responders in the case-control studies may have contributed to non-response bias limiting the generalisability of our findings. Psychometrically validated interviews were suggested as a more reliable measure for identifying the diagnosis or traits of ASD. Differences in sample sizes was also noted in studies as a limitation. It was particularly evident when using the ASSQ normative data, which was based on a sample number of 1401, much larger than the OCD samples being studied. Reference Ivarsson and Melin8,Reference Arildskov, Hojgaard, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Ivarsson and Weidle52 Smaller samples used may not be generalisable to the general population, and studies with stricter exclusion criteria may not be generalisable to youth with more complex symptom presentation. Some children and adolescent in the OCD groups were also taking pharmacological treatment, which may affect findings specifically related to the correlation between the severity of OCD and ASD traits.

Clinical implications

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests an increase in prevalence of ASD diagnosis and traits in those individuals with OCD, with comorbidity contributing to more severe functional impairment and treatment resistance to standard care. Comorbid cases may require different treatment approaches or modifications of usual interventions. Reference Jassi, Fernández de la Cruz, Russell and Krebs83,Reference Krebs, Murray and Jassi84 By screening for and identifying those with co-occuring OCD and ASD, the rates of treatment resistance may decline and length of illness and severity could reduce.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that there is an increased prevalence of ASD traits and diagnosis in children and adolescents with OCD. However, the trials have inherent methodological limitations that restrict the generalisability of these findings. On reviewing the association between OCD severity and ASD trait severity or the presence of a diagnosis, there was conflicting evidence and further research in this area is needed. Finally, this review supports that ASD trait severity or the presence of a diagnosis is associated with an increase in functional impairment, including school functioning, social functioning and both home and family activities; however, data was limited and additional research is warranted.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10936

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Paul Lee, Clinical Library Team Leader in South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust, for his support with the literature searches for this review.

Author contributions

C.T. and M.K. had the idea to complete a meta-analysis and systematic review on this topic. C.T. and P.L. completed the literature search and identified appropriate journals, and M.K. with this in relation to any conflicts during screening. C.T. extracted the relevant data, and this was analysed by M.S. and P.L. C.T. drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised by all of the listed authors.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.