Introduction

Military threat levels are increasing. We must be prepared for the worst-case scenario – an armed attack on Sweden … Our courage and will to defend our open society are vital, even though it may require us to make certain sacrifices. If Sweden is attacked, we will never surrender. Any suggestion to the contrary is false.Footnote 1

In times of increased military threats and new geopolitical challenges, national defence has rapidly become a top priority on political agendas, even in countries with little or no recent experience of armed conflict. Additionally, many states have revived the Cold War-era concept of civil defence, reintroducing it as part of a broader national security strategy. This shift of strategy views citizens as active participants in a so-called total defence approach, in which every individual contributes to the protection of the nation against antagonistic actors. Given the magnitude of this shift, how political leaders and authorities communicate these expectations, and how individual citizens and residents perceive, understand, and internalise them, becomes an important component of the national defence effort. This development also constitutes an important question in terms of what role such communication, here referred to as crisis communication, plays in shaping individuals’ defence willingness and how this context of new security challenges is perceived at the population level.

Recently, there has been a development in research on individual threat perceptions and willingness to participate in national defence. One important study, combining global data with focus groups,Footnote 2 challenges the sometimes-claimed notion that defence willingness is in decline,Footnote 3 instead demonstrating that conflict proximity plays an important role. Another relevant study, comparing survey data before and after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, shows that threat perceptions have limited explanatory value,Footnote 4 while yet others find that alliance supportFootnote 5 or identityFootnote 6 play pivotal roles. However, albeit of clear relevance to our study, much of this research focuses on willingness to engage in military defence as the measured outcome, while overlooking other components of a comprehensive total defence strategy. Moreover, with some notable exceptions,Footnote 7 the role of crisis communication by authorities in affecting public defence willingness is rarely addressed.

We believe this is an oversight in need of exploration. Given the limited interest amongst security and defence studies regarding the effects of authority crisis communication on individual defence willingness, insights from adjacent research areas different areas of crisis and communication can be of value. The field of crisis management studies, for instance, has prompted a dynamic research field that spans across academic disciplines. However, the crises examined mainly concern societal threats like hurricanes, pandemics, and earthquakes. Strategic communication often connects to national security and defence but mainly focuses on different aspects of the sender of communication. How individual citizens react to and perceive this communication has often been overlooked in these analyses.

Thus, while engaging with the different fields of defence studies, crisis management, and strategic communication studies, a gap nevertheless exists in terms of pinpointing the relationship between authorities’ communication and framing, and individual defence willingness. This paper attempts to contribute to the understanding of the complex phenomenon of how crisis communication from government authorities is perceived and internalised by individuals, asking: How does crisis communication influence individuals’ willingness to engage in total defence?

To answer this question and theorise on the logics behind individuals’ information internalisation and agency, we draw on research in social and political psychology, as this field has developed theoretical arguments about mechanisms explaining different forms of political behaviour by focusing on emotional reactions and threat perceptions.Footnote 8 We hypothesise that individuals might respond to crisis communication in different ways, and that the emotions and perceptions that arise when exposed to such communication matter for whether the individual will respond with an increased willingness to defend the country. More specifically, we hypothesise that when exposed to crisis communication, individuals will feel a sense of empowerment and become more willing to engage in the national defence. We also hypothesise that crisis communication will increase the perceived risk of war, which in turn may increase an individual’s willingness to defend the country.

To evaluate our hypotheses, we collected representative survey data among 2,068 Swedish respondents during the period when the brochure In Case of Crisis or War was distributed to every household in Sweden by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Myndigheten för samhällsskydd och beredskap/MSB) during November 2024. Our research design implies that some respondents responded to our questionnaire before they had received and read the crisis communication brochure, and others answered the questionnaire after they had read the brochure, allowing us to evaluate the effects of communication on individuals’ defence willingness in a form of quasi-experimental setting. The results support our hypotheses, showing that individuals experience a higher sense of empowerment and perceive a higher risk of war after having read the brochure, which was associated with a higher defence willingness.

Background and theory

The revival of total defence and individuals’ defence willingness: An overview

To examine the impact of crisis communication on individuals’ defence willingness in times of military threat, it is crucial to understand the concept of total defence and its security and societal implications. Total defence encompasses both military and civil defence and represents a ‘whole of society approach to national security’,Footnote 9 meaning that national security is not solely a matter for the political or military spheres of a state. Instead, security is a ‘shared task of the entire society – it must be based on a people’s defense’.Footnote 10 The comprehensive aspect makes it an effective security strategy for small states, aiming to deter a potential enemy by increasing the cost of military aggression and reducing the chances of success.Footnote 11 Traditionally, the total defence approach was employed by the militarily small and non-aligned, as this was regarded as the only way to withstand more powerful adversaries. Switzerland, Sweden, and Finland are examples where non-alignment and total defence served as guiding principles throughout the Cold War. Given the current international security situation, mid-sized states have also indicated an interest in this security arrangement, thus making it relevant to a wide array of actors.Footnote 12

While researchers and practitioners agree on the importance of both military and civilian actors in a society under threat of armed conflict,Footnote 13 most prior total defence research has studied the role of government agencies and the civil servants therein.Footnote 14 Although attempts of problematising the individual citizen in a total defence context indeed exist, for instance by examining changing perceptions of the individual in Swedish civil defence planning,Footnote 15 or how constructed identity predications shape discourses regarding the role of individuals in total defence efforts,Footnote 16 most previous studies have focused on different aspects of military participation.Footnote 17

Willingness to defend is a complex concept. It can be applied to both the individual, societal, or national level of analysis and has a myriad of meanings and definitions. In an ambitious review of the concept’s various synonyms, semantics, and meaning-making from a historical perspective, Wedebrand and Jonsson arrive at the fairly open-ended definition of being ‘inclined to act or think in certain ways for defence-related purposes’.Footnote 18 They argue that such a definition allows the usage of the concept towards both ‘contributing to the actual defense of one’s own country against an aggressor, or more generally, of contributing to the country’s overall defense capability’. Such a definition can also be ‘applied to different types of subjects (individuals or groups, military or civilian, and so on), situations (such as peace, gray zone, or war), and types of antagonism (armed or unarmed)’.Footnote 19

Adhering to this definition, and to the broad concept of total defence, we focus on three aspects of individuals’ willingness to defend, which ranges from low-cost efforts to having actual combative roles in case of war. Thereby we can capture a general effect on willingness to defend that can add to the study on defence willingness that goes beyond the often-asked questions of being willing to contribute to the military defence.Footnote 20

This focus on the military aspect of individual engagement also becomes apparent when surveying the field of other academic contributions. One strand of research focuses on willingness to fight in professional military forces such as the Canadian or the US armed forces.Footnote 21 Other studies focus on individuals’ willingness to defend, either in relation to conscriptionFootnote 22 or, as with most recent research, with the Ukraine invasion as a case in point.Footnote 23 Yet another set of studies analyse willingness to fight or to defend in global analyses, paying particular attention to the role of territorial proximity.Footnote 24 In relation to the Swedish setting there exist both some academic work and several survey reports on defence willingness. As mentioned above, Persson and Widmalm examine Swedish defence willingness in relation to threat perceptions,Footnote 25 and in a recent study Sundberg and Gustavsson analyse the effects of identity on defence willingness.Footnote 26

Several surveys have been conducted on this topic, for example the degree of crisis and defence willingness amongst individuals with a non-Swedish background,Footnote 27 and in annual opinion polls on matters relating to total defence and defence willingness.Footnote 28 As found in these different studies, and as summarised in a 2025 report: ‘the defense willingness in Sweden is high’.Footnote 29

Crisis communication and defence willingness

Although these prior works provide important insights regarding the mechanisms as to why people are willing to go to war or defend their country, they fail to capture and explain the broader dynamics of individual agency and what role communication by authorities play in the context of external military threats. When surveying the field exploring this relation, it becomes apparent that the research on this topic is scant. However, there are a few notable exceptions. Some prior works examine the role of framing on people’s resilience or willingness to defend ranging from studying framing effects and social desirability bias in survey questionsFootnote 30 to cross-national comparisons of authorities’ framing strategies in their risk communication to citizens.Footnote 31

In a study focusing on Sweden, Larsson analyses a large corpus of material in relation to authorities’ information campaigns and communication to demonstrate that a specific genealogy, linking together societal and national security strategies, has unfolded since the end of the Cold War.Footnote 32 Similarly, but with an explicit focus on gender, another article finds that gender-based power and norms dominate total defence communication.Footnote 33

While these studies constitute an important point of departure for the current study, they mostly focus on the sender of crisis information rather than what mechanisms or emotions are triggered at the receiving end of such information. Turning to adjacent research fields studying, for example, crisis information regarding non-military issues, it is found that information originating from organisations relevant to the issue at hand, along with traditional media, tends to affect individual responses and trigger certain emotions.Footnote 34 Additionally, studies on crisis management in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic show that information from authorities can induce emotions such as outrage,Footnote 35 but also feelings of national pride and trust.Footnote 36

Studies of strategic communication, another proximate area of study, also study individual responses with the explicit focus on psychological operations, so-called PSYOPs, as part of warfare. Here, scholars have found different psychological mechanisms at play when explaining individuals’ reactions to PSYOPs and that PSYOP communication measures were facilitated by ingroup identification and outgroup generalisations.Footnote 37

Taken together, this prior research demonstrates that the framing by authorities plays an important role in raising the public’s attention to problem areas and shaping the responses to them. It has also been shown that this crisis communication can elicit responses and emotions in individuals, something that points to the relevance of engaging with political and social psychology when explaining individuals’ reactions to the framing by authorities.

Expectations about crisis communication and the defence willingness of individuals

Although situating our study in relation to earlier works on total defence and defence willingness, as well as crisis management and strategic communication, when specifying our hypotheses we draw from the fields of social and political psychology. In particular, we build on research on empowerment,Footnote 38 and studies on the role of perceived threat in explaining political behaviour.Footnote 39

Psychological empowermentFootnote 40 is a motivational construct described as a subjective, cognitive, and attitudinal process that helps individuals feel effective, competent, and as though they have agency.Footnote 41 Hence, psychological empowerment increases self-determination,Footnote 42 that is, the feeling that one has choice and freedom. While the concepts of psychological empowerment and self-determination originate in organisational psychology, these concepts are fruitful to apply to political psychology, and in relation to motivation to engage in total defence. In this context, empowerment would be associated with feelings of efficacy and agency and the potential that one’s efforts have effects.

We believe that when individuals read crisis communication, their level of self-determination and empowerment may increase and spur action. More specifically, we argue that feelings of empowerment evoke positive emotions that play an important role in determining individuals’ willingness to engage in total defence. Some specific positive emotions seem significant for empowerment, such as pride, determination and honour, which we focus on here.Footnote 43

Determination can be viewed as one key aspect of empowerment,Footnote 44 and determination in the form of sensing the need to perform one’s civic duty has been found to be an important factor in, for example, studies on national conscription. Safeguarding the nation is viewed as a greater good promoted by narratives on ‘patriotism, collective responsibility, and camaraderie’, thereby consolidating a perception of obligation and determination ‘to serve one’s country as an undisputed value that sustains society’.Footnote 45 Determination can also be linked to the sense of power a person gets from engaging in a collective effort such as defence.Footnote 46

Pride, or the positive feeling towards one’s community, group, or nation in terms of which values they represent, is another emotion that contributes to empowerment.Footnote 47 Feelings of pride can positively relate to emphasis on ingroup membership. Thus, if such feelings are evoked, for instance in crisis communication, it is reasonable to believe that when key values one supports or feels pride in are claimed to be threatened, a sense of empowerment regarding the need to manage the threat is activated.

In psychological research, honour is deemed to be an important emotion that affects both intrapersonal, interpersonal, and intergroup processes in the context of external threats. Honour is often conceptualised as a form of cultural logic that serves to structure beliefs, values, and practices within a particular context.Footnote 48 Studies have found that perceived threats to an individual’s honour can result in altered behaviour, for example resulting in people being more likely to take risks.Footnote 49 Threats towards honour have been shown to result in different types of aggressive behaviours; for example, leaders from so-called honour cultures are more likely to engage in interstate conflict.Footnote 50 Importantly for our study is the finding that professional or peer honour in professional militaries affects the willingness to fight.Footnote 51

Taken together, we argue that determination, pride, and honour constitute positive emotions related to empowerment, focusing on when an individual senses a need to act to handle a situation but also the power to contribute to such an endeavour. Drawing on the literature on the consequences of such positive emotions, we hypothesise that,

H1. Being exposed to crisis communication increases a sense of empowerment, which increases an individual’s willingness to engage in the defence.

Besides such positive emotions that may arise when individuals are exposed to crisis communication, we hypothesise that the perception of whether there is a risk of conflict should matter for the individual’s defence willingness. Here we can draw on the extensive literature within the field of political psychology focusing on how threats affect political behaviour. Much of the research that has examined the relationship between perceived threat and political behaviour draws on intergroup threat theory.Footnote 52

An important aspect of intergroup threat theory is that the threats may be perceived and not actual threats and still evoke the same negative responses. For instance, believing that immigrants threaten one’s job leads to prejudice against immigrants regardless of whether one’s job security is in fact threatened by immigrants or not.Footnote 53 Thus, the extent to which individuals perceive that there is a risk of war is an individual-level, psychological feature. Recent research on threat perceptions indicates that this may motivate political action.Footnote 54

Research that focuses on other types of threats, such as existential threat, has found mixed effects on political attitudes and behaviour.Footnote 55 This type of research shows that the existential threat elicited by the thought of an unavoidable and imminent death, so-called mortality salience, elicits existential anxiety.Footnote 56 Mortality salience has been linked to political conservatism, increased nationalism, and increased Republican voting.Footnote 57 Focusing on political participation, Denny found that experimentally induced financial anxiety increased political participation when participation was easy and immediate, such as signing an online petition. Hence, there is some evidence suggesting that risk perceptions may increase an individual’s willingness to take action,Footnote 58 even though the results in the previous literature on defence willingness are mixed.Footnote 59

Similarly, we argue that crisis communication that creates a sense of urgency, stressing the immediate risk of war, should influence whether people are willing to engage in the national defence or not. When people perceive that there is an imminent risk of war, they should be more willing to defend the country, and we thus hypothesise that,

H2. Being exposed to crisis communication increases the perceived risk of war, which increases an individual’s willingness to engage in the defence.

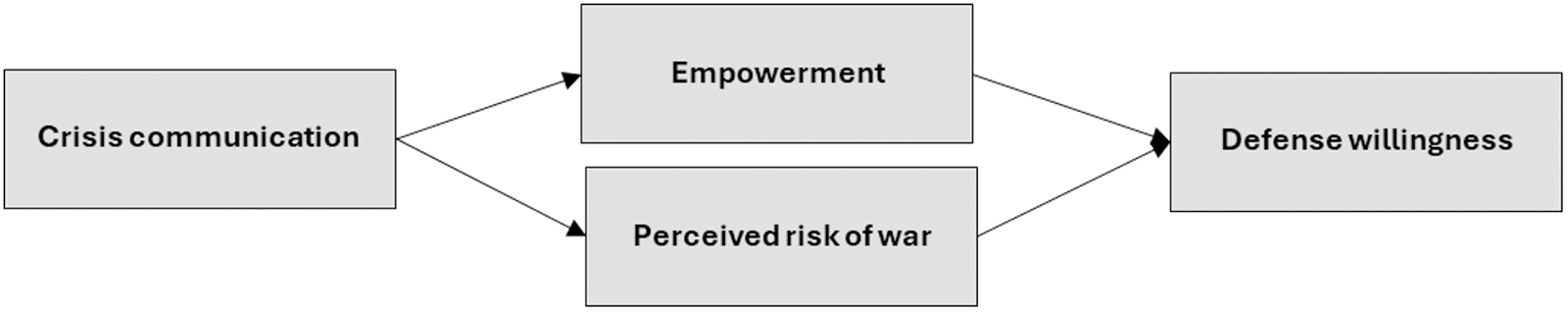

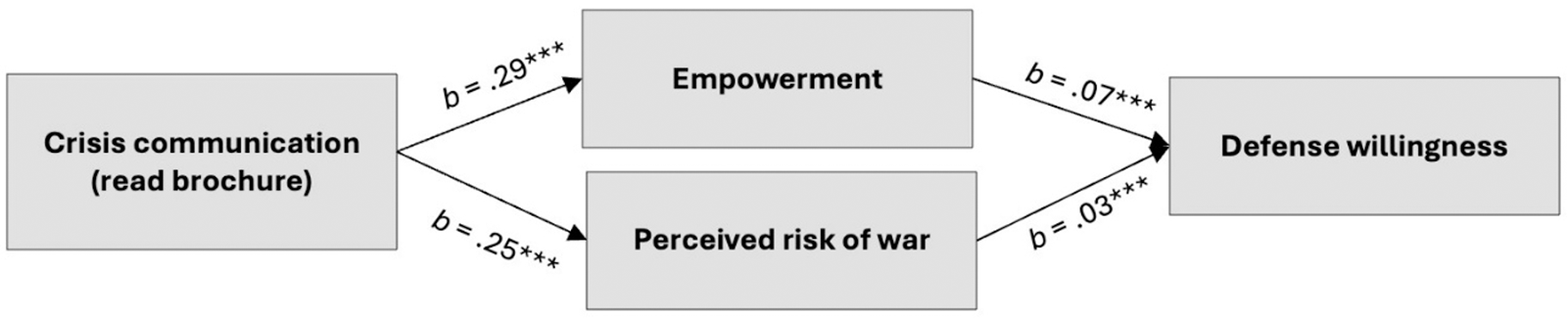

In sum, as our two proposed hypotheses suggest, and as illustrated by Figure 1, we argue that there are two possible pathways to understanding the linkage between the crisis communication by authorities and the defence willingness of the individual citizen, focusing on the role of a sense of empowerment and the perceived risk of war.

Figure 1. A framework on crisis communication and willingness to defend.

Research design and data

Case of crisis or war: Total defence and crisis communication in Sweden

To understand the effects of crisis communication from government authorities on individual defence willingness, the Swedish revival of its total defence doctrine, along with the distribution of the brochure In Case of Crisis or War, provides a particularly illuminating case.

The brochure In Case of Crisis or War has since the Cold War played an important role in Swedish civil defence. First published in 1943 and titled Om kriget kommer, or, In Case of War, the brochure was ‘guidance for the citizens in case of war’.Footnote 60 It spelt out the different functions of citizens in wartime, ranging from conscripted soldiers to civil volunteer troops, civil non-combatants, and the civil authorities. The brochure was published in four additional editions until its termination in 1987, although the last two issues were only published as part of the telephone directory. All printed versions of the brochure had the same overarching theme but with increasingly more detailed conceptualisations on the meaning of total defence and resilience, as well as practical tips on what to pack in the case of evacuation, what to do during an attack or when you hear an air raid siren, and radioactive protection.Footnote 61

As the Cold War ended so did the idea of total defence, and Swedish authorities saw no continued need for the brochure. Based on broad political consensus, the Swedish Armed Forces’ wartime strength was reduced by 95 per cent and most of the military bases in Sweden were closed. Military conscription in peace time was inactivated 2010–17 on behalf of a professional all-volunteer force, and the Swedish Armed Forces changed its focus from invasion defence to operational defence.Footnote 62 Sweden’s civil defence was replaced by crisis management, focusing on crises such as forest fires and flooding rather than war. Thus, the concepts of total defence, civil defence, and defence willingness did not play any significant role in Swedish society for thirty years.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the proxy wars in eastern Ukraine became a wake-up call, and in 2015 the Swedish government once again decided to reinstate a total defence. To activate the civilian population, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB) decided in 2018 to issue a new version of the brochure, now including ‘crisis’ in the title. Although containing information on total defence, warning systems, and one page on what the effects of an armed attack could be, the 2018 version of the brochure mainly focused on societal preparedness should a crisis happen, including checklists of foodstuffs to keep in the house.Footnote 63

After some years of increased geopolitical tensions and a deteriorating security situation, not least epitomised by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the authorities saw the need for another, updated brochure, and in November 2024 it was distributed to every household in Sweden.Footnote 64 After the initial distribution round, the brochure could also be accessed at the website of the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency in easy-to-read Swedish, sign language, audio format, braille, Arabic, English, Farsi, Finnish, Meänkieli, Polish, Romani Chib, Somali, Ukrainian, and northern and southern Sámi. In other words, the Swedish authorities took every available measure to ensure that their crisis communication reached everyone residing in Sweden.

Despite sharing the same title, the 2024 edition of In Case of Crisis or War is a very different publication compared to both its Cold War counterparts and to the 2018 edition. Combining the wartime narratives of the Cold War editions with the views on societal and non-military threats of the twenty-first century, the brochure constitutes an interesting mixture of simultaneously installing fear and promoting resolve, all in the setting of a modern, gender equal, and multicultural society.

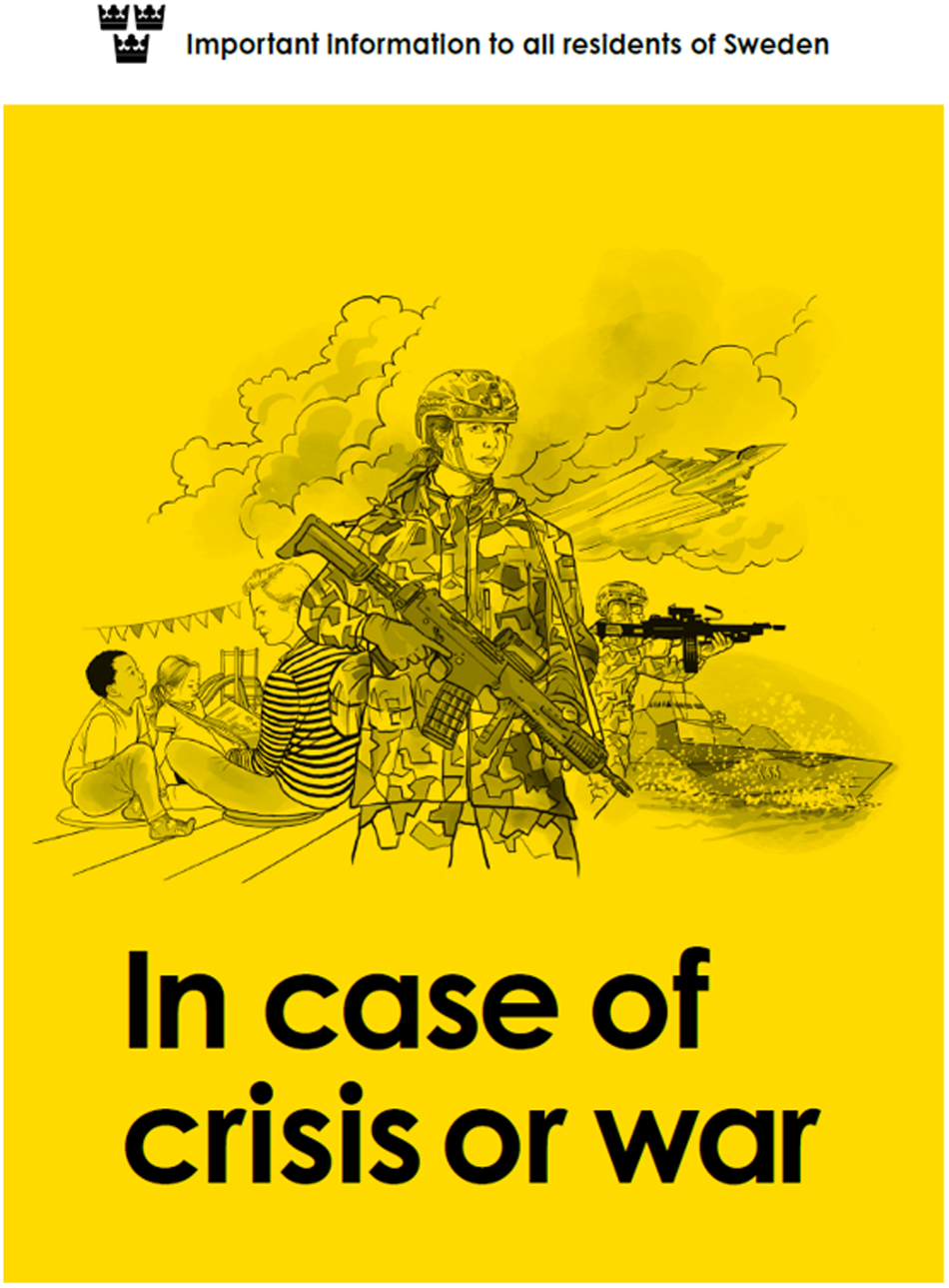

In Case of Crisis or War provides a wide array of crisis communication messaging. A substantial part of this reflects our theoretical constructs of empowerment and perceived risk of war. On the cover of the brochure, there is an illustration of a woman in combat uniform (see Image 1 ), holding an Automatic Carbine 5, looking determined. Behind her, another soldier aims his gun, a navy ship speeds through the water, a JAS Gripen fighter jet flies through the sky, and a man in a striped sweater sits on the floor, reading stories to children. The brochure then continues to cover topics such as ‘In uncertain times, it is important to be prepared’Footnote 65 and ‘Together we make Sweden stronger’.Footnote 66 These themes are followed by topics such as total defence duty, warning systems, how to seek shelter during air raids, how to stop bleeding, and how to take care of your pets in the event of crisis or war.

Image 1. Front page of the brochure from the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency 2024.Footnote 67

The brochure seems to instil both a sense of urgency in the individual reader as it stresses the gravity of the current situation as well as a sense of resolve as it emphasises the role of the individual in the management of this endeavour. The threat is presented in a straightforward manner, as illustrated by the following quote:

We live in uncertain times. Armed conflicts are currently being waged in our corner of the world. Terrorism, cyber attacks, and disinformation campaigns are being used to undermine and influence us.Footnote 68

This troublesome context is further stressed by declaring that military threat levels are increasing and that an armed attack can be launched against Sweden. The different threat images are also visualised by drawings illustrating how people seek shelter in a ditch and under a bridge during air strikes, how people are running into a bomb shelter, and how a worried woman attempts to stop bleeding by pressing her hands to the wound of an unconscious person.

However, the brochure also provides a remedy for these threatening situations. Under the heading ‘Together we make Sweden stronger!’Footnote 69 the whole-of-society approach is declared, requiring that ‘we unite against an aggressor’.Footnote 70 Total defence duties apply to everyone aged between 16 and 70, and to citizens and foreign nationals residing in Sweden alike. At a heightened state of alert, one will either be part of the military defence protecting Sweden’s borders, the civil defence supporting the military and society at large, or the general national service in which one carries out work or other tasks that contribute to the total defence generally. This means that defence is not merely an activity for the military; instead, there is a role for every resident, and everyone can and must prepare and contribute:

To resist these threats, we must stand united. If Sweden is attacked, everyone must do their part to defend Sweden’s independence – and our democracy. We build resilience every day, together with our loved ones, colleagues, friends, and neighbours. In this brochure, you learn how to prepare for, and act, in case of crisis or war. You are part of Sweden’s overall emergency preparedness.Footnote 71

A representative survey on defence willingness in Sweden

To evaluate our hypotheses, we performed a large-scale survey study among the Swedish population during the weeks in November 2024 when the new brochure from the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency was distributed among Swedish citizens.Footnote 72 The brochure was sent by post to every Swedish household from 18 November to 29 November, while our survey was distributed between 11 November and 6 December. This setup provides for a unique design since it ensured that some respondents would respond to our questionnaire before they had received and read the brochure, and others would answer the questionnaire after they had read the brochure. Even though this does not mean that we have a fully randomised experimental treatment, the timing of our study implies that we can analyse the impact of the crisis communication in a form of ‘quasi-experimental’ setting, allowing us to evaluate the effect of this type of communication.

The survey study was performed in collaboration with the survey company Lysio, who distributed the survey among a representative sample of the Swedish population. The total sample (N = 2068) included 1019 (49.3 per cent) women and 1049 (50.7 per cent) men. Age ranged from 18 to 88 (M = 47.91, SD = 17.80). As for participants’ education level, 12 (0.6 per cent) had not completed primary school, 156 (7.5 per cent) had finished primary school or its equivalent, 973 (47.1 per cent) had completed upper secondary school or an equivalent level, 868 (42.0 per cent) held a higher education qualification such as a university or college degree, and 59 (2.9 per cent) had earned doctoral degrees. The average political ideology score was 5.39 (SD = 2.60), ranging from 1 (clearly to the left) to 10 (clearly to the right). In our sample, 380 individuals (18.4 per cent) reported having either own experience, and/or experience by someone close to them, of living in a war zone or of armed conflict. Finally, 1448 (70.3 per cent) reported Sweden as their country of birth, 293 (14.2 per cent) reported being born abroad, and 319 (15.5 per cent) had at least on parent born abroad.

Defence willingness: The dependent variable

The dependent variable in our analyses is willingness to defend, which was measured with three items that were collapsed into an additive (mean) index (α = .72). Participants were asked ‘To what extent would you be willing to do the following things in the event of war or crisis?’, and rated their responses on a scale from 1 (‘to a very small extent’) to 7 (‘to a very large extent’); ‘Have a combative role in an armed defence of Sweden’, ‘Join a civilian organisation that supports the military defence and maintains essential societal functions’, and ‘Perform my usual work or other tasks if they are important for total defence’.

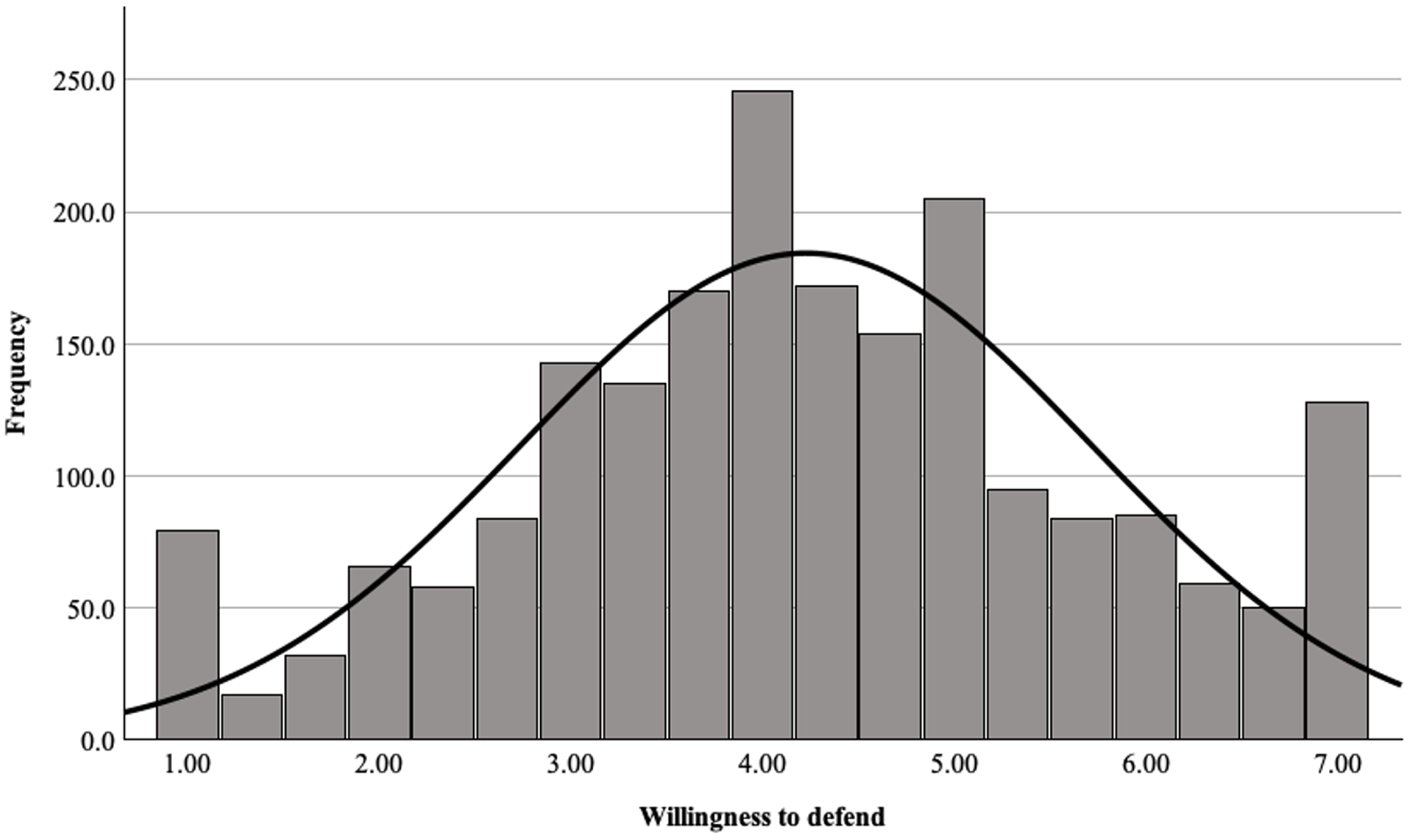

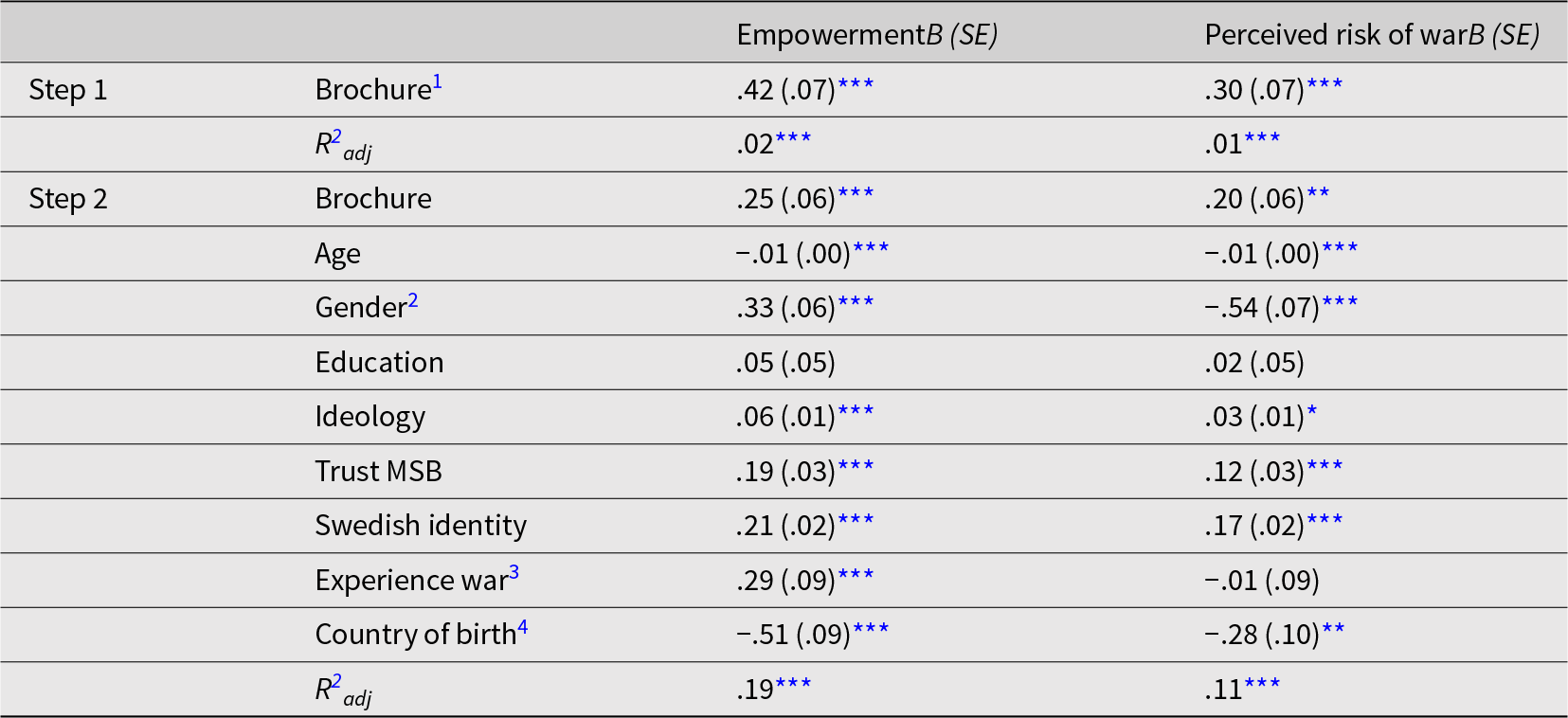

First, we present some descriptive statistics for the dependent variable willingness to defend (see also Table A2). On a scale from 1 to 7, where higher values reflect a greater willingness to defend, the average score was 4.23 (SD = 1.49). This suggests that the general defence willingness among Swedes is relatively high, something that mirrors the findings of previous studies.Footnote 73 Figure 2 shows the distribution of values across the entire sample.

Figure 2. Histogram willingness to defend index.

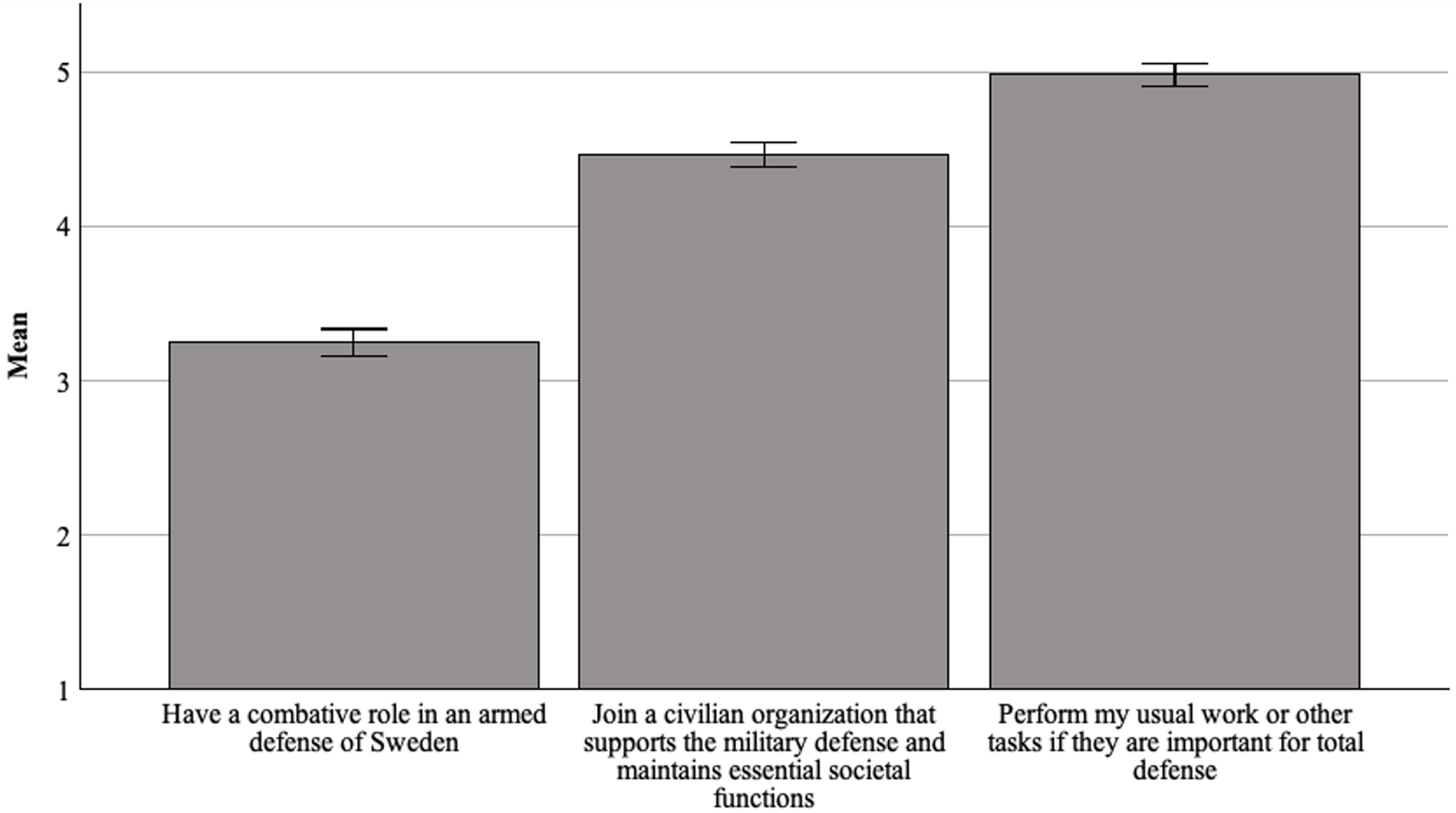

In Figure 3, we present the mean values for the three individual items measuring willingness to defend. To test whether the mean differences between items were significant, we conducted a repeated measures ANOVA. The results showed significant differences between all items, F(1.71, 3525.74) = 874.41, p < .001, η2 = .33. That is, the mean for the willingness to have a combative role in an armed defence in Sweden was the lowest (M = 3.24, SD = 0.05), followed by the willingness to join a civilian organisation (M = 4.46, SD = 0.04), and the willingness to perform one’s usual work/other tasks was the highest (M = 4.98, SD = 0.04).

Figure 3. Mean values for each item measuring willingness to defend.

Independent variables

The main independent variable measuring if the respondents had been exposed to crisis communication was a question asking whether they had read the MSB brochure: ‘During the month of November, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency sends out a new edition of its brochure Om krisen eller kriget kommer (In Case of Crisis or War). Have you reviewed the information in it?’ The response options were ‘Yes’, ‘No, I have not received it’, ‘No, I have not had the opportunity to read it yet’, and ‘No, and I do not intend to read it’. The distribution of responses on this variable is described in Figure 4. As shown, the largest proportion of the sample has read the brochure. However, when combining all three groups of non-readers, the total percentage surpasses the proportion of readers. In the following analyses, we use a dichotomous independent variable describing if the respondents had read the brochure (1) or not (0).Footnote 74

Figure 4. The percentage of the sample that has or has not read the brochure.

Our hypotheses propose two mechanisms that may lead to an increased willingness to defend when being exposed to crisis communication, focusing on either the sense of empowerment when getting such information, or the perceived risk of crisis or war when getting such information. Hence, empowerment and perceived risk of war constitute mediating variables.

The question measuring empowerment reads: ‘It is often stated that the global situation has become more unstable and that the risks of hostile military actions against Sweden have increased. When you think about the risk of war against Sweden – to what extent do you experience the following feelings?’ [determination, pride, honour]. Participants rated their experience of the emotions from 1 (‘to a very small extent’) to 7 (‘to a very large extent’). We created an index taking the average of these emotion items (α = .81). The mean was 3.62 (SD = 1.43).

The perceived risk of war was measured with two items collapsed into an additive index (r = .51, p < .001). The items were the following: ‘The likelihood of an armed conflict in Sweden has increased over the past year’, and ‘I have become more worried in the past month that a serious crisis will occur in Sweden’. Participants were asked how much they agreed with each item on a scale from 1 (‘do not agree at all’) to 5 (‘completely agree’). The mean was 4.23 (SD = 1.48).

We also include several control variables in our analyses, drawing on the previous literature.Footnote 75 Gender (man and woman) and age (in years) were obtained from the survey company. Education was measured on a scale from 1 (‘not completed basic schooling’) to 5 (‘doctorate degree’). Ideology was measured on a scale from 0 (‘clearly to the left’) to 10 (‘clearly to the right’). Trust in MSB was measured with the item: How much trust do you have in the way the following institutions and groups carry out their work? The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB), rated on a scale from 1 (‘very little trust’) to 5 (‘very high trust’). Swedish identity was measured with the question ‘How important would you say being Swedish is to your identity?’ with response options from 1 (‘not at all important’) to 7 (‘very important’). Previous experience of war was assessed with the item: Have you or someone close to you experienced living in a war zone or an armed conflict? The response options were yes and no. Finally, country of birth was measured with the item: Were you or any of your parents born abroad? (response options were ‘Yes, I was’, ‘Yes, at least one of my parents’, and ‘No’).

Empirical results

The effect on empowerment and perceived risk of war

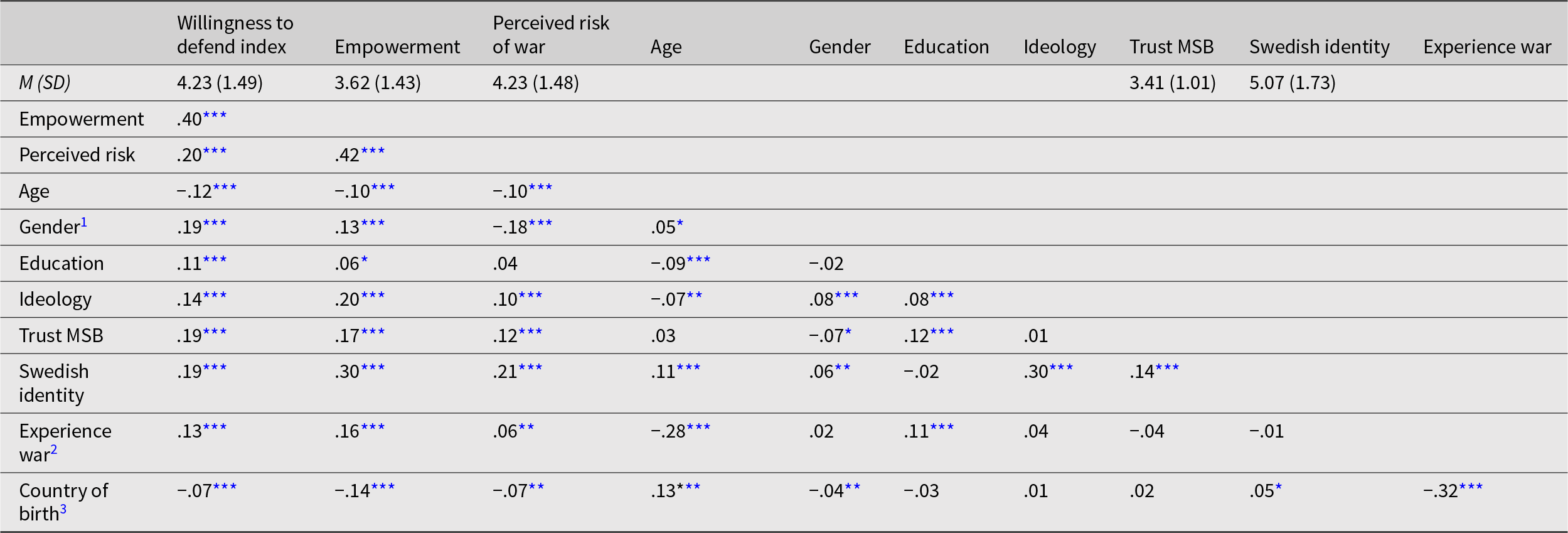

To evaluate the effects of crisis communication, we start out by analysing whether having read the brochure predicts our proposed mediators: a sense of empowerment when thinking about the risks of war against Sweden, as well as the perceived risk of war against Sweden. To this aim, we performed regression analyses in several steps. In Step 1, we included the main predictor variable of whether the participant has read the brochure, and in Step 2, we added control variables, namely age, gender, education, ideology, trust in MSB, Swedish identity, previous experience of war, and country of birth (descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are presented in the Appendix).

As demonstrated by Table 1, those who have read the brochure report a stronger sense of empowerment and a higher perceived risk of war. This result aligns with the theoretical claims that determination, pride, and honour are important sentiments that contribute to both individuals’ sense of belonging to a group and resolve to protect that group. Similarly, exposure to information on threats can make individuals more attentive to developments in their surrounding context, interpreting different events as elevated threat levels. Once the other relevant predictors have been accounted for in Step 2, the effect of having read the brochure decreases for both empowerment and the perceived risk of war. However, these effects are still significant.

Table 1. Predicting empowerment and the perceived risk of war.

Note:

1 Having read the brochure is coded 1 = have read, 0 = have not read.

2 Gender is coded as 1 = Men, 0 = Women.

3 Experience of war is coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

4 Country of birth is coded 1 = Born in Sweden, 0 = Born abroad. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Looking at the other predictors, older individuals report less empowerment, while men, those with a stronger right-wing ideology, a stronger Swedish identity, higher trust in MSB, and previous experience of war report more empowerment. Participants who are born in Sweden report less empowerment compared to participants born abroad. The results of the perceived risk of war are similar. Older individuals report lower perceived risk, while those with a stronger Swedish identity and higher trust in MSB report higher perceived risk. However, men report lower perceived risk, and also participants born in Sweden.

The effect on willingness to defend

We now move on to testing the full model analysing whether empowerment in response to thinking about the risk of war against Sweden and the perceived risk of war mediates the relationship between having read the brochure and one’s willingness to defend.

Before discussing the results, it is relevant to reiterate what defence actually entails in the context of total defence as discussed In Case of Crisis or War. First, the concept of a ‘heightened state of alert’ is clarified.Footnote 76 As described above, the total defence service requires everyone from the age of sixteen to seventy to participate. It applies to all residents in Sweden and to Swedish citizens living abroad. Total defence duty consists of three separate strands. The first is military service, which involves having a combat role in the territorial defence of the country. The second is civil service, which entails the support of the military or the maintenance of other central societal functions. Individuals who have been called into either military or civil defence service are to immediately proceed to their wartime posting location during a heightened state of alert. The third activity is the general national service, which means that people remain at their normal forms of employment ‘or carry out other tasks in support of Sweden’s total defense system’.Footnote 77

To examine how this resonated with the readers of the brochure, we present mediation analyses,Footnote 78 where the dependent variable is an index measuring willingness to defend, and we also present analyses on each item of defence willingness separately. These analyses are based on 5,000 bootstrapped iterations to generate confidence intervals for the indirect effects. The mediators are empowerment and perceived risk of war, and we include the same controls as in previous models.

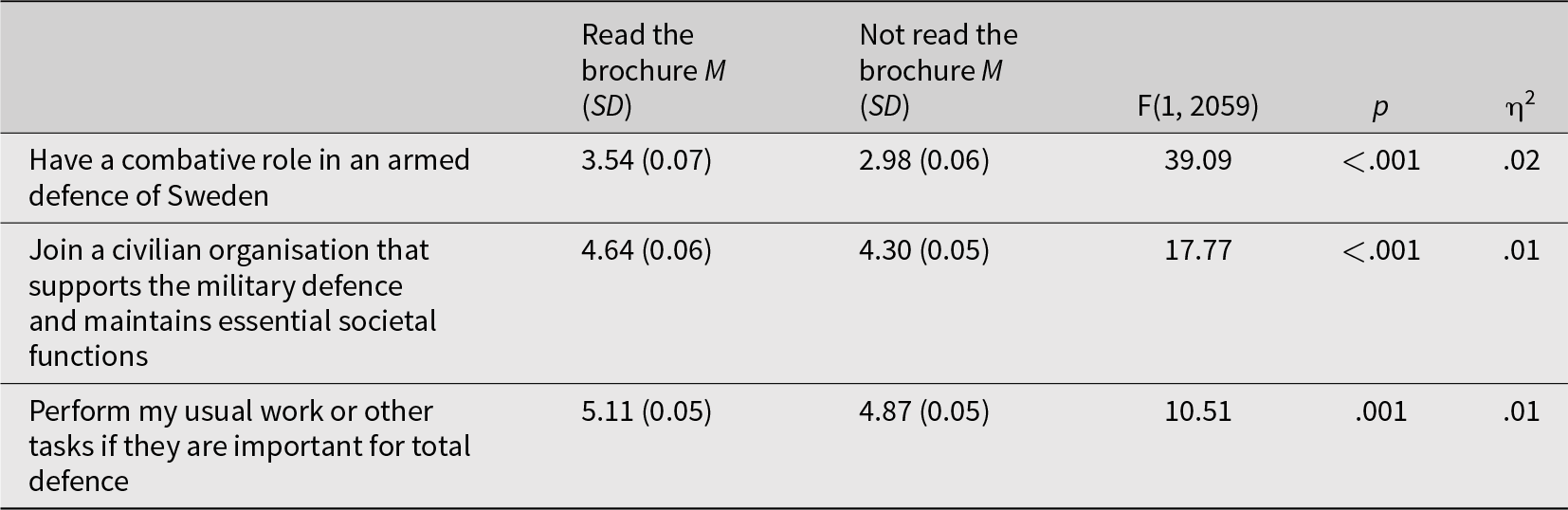

Before presenting these mediation analyses, we analyse the relationship between willingness to defend and our main independent variable, whether participants had read the brochure or not. First, we conducted an independent samples t-test and found that participants who had read the brochure reported a significantly higher willingness to defend (M = 4.43, SD = 1.49) compared to participants who had not read the brochure (M = 4.05, SD = 1.46), t(2059) = 5.84, p < .001, d = 0.26. Next, we test how the relationship appears for each individual item measuring willingness to defend, by conducting a MANOVA with having read the brochure or not as a between-participants factor (see Figure 5). All three items show significant differences between groups, with those who read the brochure reporting higher scores across all items of defence willingness. See Table A3 for an alternative coding of the independent variable.

Figure 5. Different forms of willingness to defend sorted by having read the brochure or not.

In Table 2, we present the results from the regression model predicting willingness to defend based on our main independent variable, whether participants had read the brochure or not, the mediators, and control variables. First, having read the brochure has a significant effect only when predicting the individual item ‘Having a combative role in an armed defence of Sweden’, whereas the effect of the brochure on the index and the other individual items becomes non-significant when controlling for the mediators and control variables. Second, both mediators, empowerment and the perceived risk of war, predict a higher willingness to defend, as measured by the mean index as well as by each individual item separately. Hence, individuals who feel empowered and who perceive an increased risk of war are more willing to engage in the total defence.

Table 2. Predicting willingness to defend.

Note:

1 Having read the brochure is coded 1 = have read, 0 = have not read.

2 Gender is coded as 1 = Men, 0 = Women.

3 Experience of war is coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

4 Country of birth is coded as 1 = Born in Sweden, 0 = Born abroad. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Looking at the control variables, we can see that older people generally report lower willingness to defend. However, there is no effect of age on willingness to join a civilian organisation, and older individuals report greater willingness to perform their usual work or other tasks.

Furthermore, men report higher willingness to defend on all measures compared to women. Individuals with higher education also report higher willingness to defend in general, but not when it comes to taking on a combative role. Those with greater trust in the Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB) report a higher general willingness to defend, but not for combative roles. Individuals with a stronger Swedish identity, as well as those with previous experience of war, report a higher willingness to take on a combative role, but not to join a civilian organisation or perform their usual work or other tasks. Finally, there is no effect of country of birth on willingness to defend, for either the mean index or individual items.

Moving on to the indirect effects presented in Table 3, as can be seen, all of the confidence intervals for the indirect effects of empowerment and perceived risk of war do not include zero when predicting willingness to defend, for both the index and the individual items. This indicates statistically significant effects. In other words, empowerment and perceived risk of war mediate the relationship between having read the brochure and a higher willingness to defend. Results from analysing the full model are described in Figure 6.

Table 3. Indirect effects from mediation analysis.

Note: LLCI = 95 per cent lower-limit confidence interval; ULCI = 95 per cent upper-limit confidence interval. Confidence intervals that do not include zero indicate statistically significant effects.

Figure 6. Results from mediation analysis using the index for the dependent variable.

The results from this analysis show that both empowerment and perceived risk of war significantly mediate the effect of having read the brochure on defence willingness (index). Similar results are found when analysing each individual item of defence willingness. That is, after having read the brochure and experiencing empowerment, or increased risk of war, participants reported higher willingness to have a combative role in an armed defence of Sweden, joining a civilian organisation that supports the military defence and maintains essential societal functions, and performing one’s usual work or other tasks if they are important for total defence.

Taken together, these results show that experiencing a higher sense of empowerment and a higher perceived risk of war statistically accounts for the relationship between having read the brochure and a higher willingness to defend. All in all, the results in these analyses support our hypotheses that individuals who respond to crisis communication with a higher sense of empowerment, and/or a higher perceived risk of war, are more willing to engage in the total defence.

Concluding discussion

The present article aimed to increase our understanding of how citizens internalise and react to crisis communication by authorities in times of international tensions, conflict, and military threat. In this endeavour, we built on the findings and theoretical arguments from different literatures such as defence studies, crisis management, strategic communication, and political psychology. Specifically, we wanted to better understand when such information may lead citizens to become increasingly willing to defend their country and to contribute to the growing research on total defence efforts and defence willingness.

To this aim we utilised the fact that the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Myndigheten för Samhällsskydd och Beredskap) distributed a brochure, In Case of Crisis or War, to all Swedish households during November 2024. This brochure is focused on preparation for crisis but also strongly focused on war – how to engage in total defence or where to find shelter during air raids. Its contents were illustrated by drawings mainly showing war-related images. By distributing a survey among individuals that varied in relation to having read this publication, we could establish the effects of having read the brochure.

Drawing from theories on social and political psychology, we hypothesised that having read the brochure would make individuals feel empowered through increased knowledge of how to act in the case of crisis or war and that this empowerment would also make them more willing to defend their country. Further, we also hypothesised that reading the brochure would make the possibility of crisis or war more salient and psychologically closer, evoking perceptions of threat, which in turn also should increase willingness to defend.

These expectations are supported by our empirical analyses. Having read the brochure was related to increased empowerment and perceptions of risk of war, which both were related to increased willingness to defend Sweden. These results are important for several reasons. First, they show that this kind of information about security and national threats influence citizens, making them more willing to defend their country. Second, we also show that this effect works through two separate mechanisms – empowerment and threat perceptions. For people to want to engage, it is necessary to feel empowered to do so – in terms of both feeling the capacity to act as well as that their actions will count for something. In this study, we conceptualised empowerment as an aggregated measure of positive emotions, specifically determination, pride, and honour. All of these emotions have previously been shown to have effects on individuals’ willingness to fight and defend.Footnote 79

The other mechanism we suggest for how crisis information influences individuals’ defence willingness is perceived threat, which was measured as perceptions of the risk of war. War can be seen as the ultimate form of intergroup threat – the perception that another group is in position to threaten the own group.Footnote 80 Such threats increase defensive actions in order to defend the ingroup, which here is translated into people becoming more willing to defend.

Our results are not completely in line with previous research performed in a Swedish context. In the comprehensive study performed by Persson and Widmalm there is no evidence that threat perceptions increase individuals’ defence willingness.Footnote 81 Their study focuses exclusively on military defence willingness, but we do not believe that this is the reason for the differences in the results found in our study compared to that study, since we find similar effects of risk perceptions when analysing military defence willingness only (i.e., in addition to when analysing our index, which also captures other forms of defence willingness). One potential explanation for the differences in the results may be that we use slightly different measures of threat perceptions. Another potential explanation is that our survey was conducted during a different time period. Their study was conducted a few years before our study, and it could be the case that threat perceptions have different consequences for behaviour during different time periods. Another potential explanation to why we find significant effects of threat perceptions on defence willingness whereas they do not could lie in the fact that our ‘quasi-experimental design’, where some individuals had been ‘treated’ with being exposed to the brochure, created a temporary heightened sense of threat among some individuals, resulting in a higher variation in the threat perception variable. A higher variation may in turn have led to stronger effects as this extra variation makes it more likely to detect significant effects.

Although our selected research design allows us to some extent to gauge the effects of reading certain types of crisis information, it comes with some limitations. First, the fact that we distributed our questionnaire during the period when the Civil Contingencies brochure was circulated allowed us to analyse the effect of having read the brochure or not, but it does not constitute a proper experiment where individuals are randomised into a treatment and a control group. The design is what is known as a quasi-experiment, which is an experimental design that lacks the random distribution of participants into experimental and control groups. Yet, this design does come closer to studying causal mechanisms compared to a pure cross-sectional study.

Some individuals may have been more attentive to receiving the brochure in their mailbox and may have been more likely to read the information immediately, and some unmeasured features of these individuals may also influence their defence willingness. However, it is likely that due to the randomness of the brochure distribution (which was rolled out in different regions at different time points), these features should be equally present in the group who did not receive the brochure and thus had not read it. Further, we believe that this is less likely to be a problem since we control for a number of features that also influence if the individuals had read the brochure or not (see the Appendix, Table A1). However, it is a clear limitation of this study is that we cannot be completely certain about the suggested causal effects in the present study, and we therefore suggest that future research should perform controlled experiments analysing the effect of being exposed to different types of information on defence willingness.

A related important note concerns the statistical effects. As described in the manuscript, the direct effect of having read the brochure on willingness to defend when controlling for the mediators and additional control variables was only significant when predicting the individual item ‘Having a combative role in an armed defence of Sweden’, whereas the effect of the brochure on the index and the other individual items becomes non-significant when controlling for the mediators and control variables. This is important, as one might expect that the individual item ‘Perform my usual work or other tasks if they are important for total defence’ would show the strongest effects, since it can be interpreted as the individual being able to carry on with business as usual and it requires less personal sacrifice. However, given that our main independent variable did not have a significant effect on this item, we can also conclude that this item is not driving the effects. Furthermore, the results did show that the effects of having read the brochure on the mediators – empowerment and perceived risk of war – are significant, even when controlling for relevant background factors. In other words, our model indicates full mediation, where empowerment and perceived risk of war statistically account for the relationship between having read the brochure and willingness to defend.

The effect sizes can be considered small; however, it is important to note that small statistical effects are not necessarily less practically meaningful, as small effects in large samples are often more reliable.Footnote 82 In addition, smaller effects are also in line with what one would expect, given that there are countless other factors that can influence the results. Therefore, we do not exclude the possibility that other important factors, not accounted for in our study, may also contribute to a better understanding of willingness to defend.

For future research, we suggest that experiments should be performed where specific parts of the crisis communication are isolated, to determine what part of the texts spurred individuals’ emotions, perceptions, and defence willingness. This would allow scholars to further explore how specific types of crisis communication increase individuals’ willingness to engage in the national defence. Importantly, the brochure focused on different types of crisis events, like natural disasters, in addition to crises related to war, and since previous research has shown that there is a clear distinction between ‘crisis willingness’ and ‘willingness to defend’,Footnote 83 future research should explore whether different types of information lead to different types of engagement.

Some other findings that we have presented here are also worth commenting on. For example, we find that individuals with previous experience of war report a higher willingness to take on a combative role, but not to join a civilian organisation or perform their usual work or other tasks. These results suggest that individuals with some specific experiences are more likely to engage in the military defence. These results complement previous research that has shown that individuals who are born in another country than Sweden were more willing to engage in the military defence.Footnote 84 We suggest that future research focuses on how such experiences of conflict interact with being exposed to specific types of crisis communication in influencing defence willingness, for example through performing controlled experiments.

The present research has important consequences for the understanding of how citizens process crisis information from authorities and what mechanisms motivate them to engage in defensive actions. Our study has thereby generated different contributions in relation to both theoretical development and empirical findings. As discussed above, our engagement with the literature from social and political psychology has brought about insights regarding the conditions of which crisis communication is effective, and which emotions trigger individuals to participate in national defence. Although aspects of our proposed mechanisms have to some extent been validated previously in studies on willingness to fight and defend, our study demonstrates that framing is essential in eliciting certain emotions, which in turn affects the agency of the individual. Our mediation analysis helps to demonstrate this phenomenon.

Given the current state of international security affairs, countries are undergoing rapid changes concerning defence matters and on how national defence should be conducted. Although most states in Europe are continuously increasing their defence budgets, a successful national defence requires more than powerful armed forces in terms of vast manpower or sophisticated military technology. As the three years of Ukrainian resistance has demonstrated, military might does not necessarily equal walkover victories. On the contrary, this example points to the importance of comprehensive approaches that appreciate and disseminate information regarding the situation at hand but also contribute to a shared societal understanding that fosters resilience and resolve. As indicated by the findings presented in this paper, fairly simple measures, as epitomised by the crisis communication by the Swedish authorities examined here, can clearly contribute to the instalment of such sentiments and thereby contribute to the reconstruction of a total defence.

Funding Statement

The research is funded by the Swedish Research Council, research grant 2023-06114.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not made publicly available due to adherence to the ethical guidelines of the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Appendix

Predicting having read the brochure

We conducted a binomial regression model with having read the brochure or not as the dependent variable, using relevant predictors based on previous research. We chose to combine all the no responses so that (1 = yes, 0 = all no responses). The predictors we included were age, gender, education, right-wing ideology, trust in MSB, Swedish identity, and experience with war. Education, trust in MSB, Swedish identity, and having experience with conflict positively and significantly predicted having read the brochure.

Replicating the main analyses using an alternative coding of the independent variable

In this section, we present the same main analyses as in the manuscript, but the independent variable – having read the brochure – is instead coded as 1 = yes, having reviewed the information in the brochure, and 0 = no, not having received the brochure. The options of not having had the opportunity to review the information or not intending to do so are coded as missing. In Table A4, we present the regressions predicting the mediators, empowerment and perceived risk of war. In Table A5, we present the regression predicting the outcome, willingness to depend, including all predictors and mediators. Finally, in Table A6, we present the mediation effects of empowerment and perceived risk of war on willingness to depend. As can be seen in the tables, the effects are similar to those presented in the manuscript.

Table A1. Binomial regression model predicting having read the brochure or not.

Note:

1 Gender is coded as 1 = Men, 0 = Women.

2 Experience of war is coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

3 Country of birth is coded as 1 = Born in Sweden, 0 = Born abroad. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Table A2. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations.

Note:

1 Gender is coded as 1 = Men, 0 = Women.

2 Experience of war is coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

3 Country of birth is coded as 1 = Born in Sweden, 0 = Born abroad. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Table A3. MANOVA results.

Table A4. Predicting empowerment and the perceived risk of war.

Note:

1 Having read the brochure is coded 1 = have read, 0 = have not read.

2 Gender is coded as 1 = Men, 0 = Women.

3 Experience of war is coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

4 Country of birth is coded 1 = Born in Sweden, 0 = Born abroad. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Table A5. Predicting willingness to defend.

Note:

1 Having read the brochure is coded 1 = have read, 0 = have not read.

2 Gender is coded as 1 = Men, 0 = Women.

3 Experience of war is coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

4 Country of birth is coded as 1 = Born in Sweden, 0 = Born abroad. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Table A6. Indirect effects from mediation analysis.

Note: LLCI = 95 per cent lower-limit confidence interval; ULCI = 95 per cent upper-limit confidence interval. Confidence intervals that do not include zero indicate statistically significant effects.

Hanna Bäck is a professor of political science at Lund University, Sweden. Her research focuses on political parties, representatives and political behaviour in Western European democracies, for example on topics related to affective polarisation. She has published extensively on these topics, for example in journals such as British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, Journal of Politics, and Political Psychology.

Amanda Remsö is a PhD student in psychology at Kristianstad University and the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her dissertation focuses on political polarisation related to gender, and another research focus is polarisation related to climate change.

Emma A. Renström is a professor of psychology at Kristianstad University, Sweden. Her background is in social psychology and she has mainly worked on topics in political psychology, such as polarisation and political behaviour. Another topic of interest is anti-vaccination attitudes. She has published in high-ranked journals such as Political Psychology, European Journal of Social Psychology, and Sex Roles.

Roxanna Sjöstedt is an associate professor of political science at Lund University, Sweden. Her research centres around international security, national defence, threat construction, military intervention, and securitisation. She has published on these topics in journals such as European Journal of International Security, Cooperation and Conflict, Foreign Policy Analysis, and International Studies Review.