Introduction

Living with a serious mental illness (SMI), such as bipolar disorder (BD) or schizophrenia (SCHIZ), is associated with a reduction in life expectancy of 12–15 years [Reference Chan, Correll, Wong, Chu, Fung and Wong1]. Despite the high risk of suicide, in SMI, most deaths and years of life lost are due to natural causes [Reference Jayatilleke, Hayes, Dutta, Shetty, Hotopf and Chang2]. Cardiovascular, metabolic, and respiratory diseases, present at a younger age and with a generally worse prognosis, are the main threat [Reference Biazus, Beraldi, Tokeshi, de S Rotenberg, Dragioti and Carvalho3, Reference Correll, Solmi, Croatto, Schneider, Rohani-Montez and Fairley4]. These patients are exposed to multiple risk factors at different levels: individual factors, healthcare systems, and social determinants of health [Reference Liu, Daumit, Dua, Aquila, Charlson and Cuijpers5].

Most of the meta-research on physical health in this population has focused in recent years on cardiovascular and metabolic risks. However, data from different European and US cohorts highlight a high risk of respiratory mortality, especially in young populations [Reference Hayes, Miles, Walters, King and Osborn6, Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup7]. Among individuals with SMI, the smoking rate – a key critical factor for respiratory disease – is up to three times higher than that of the general population, with greater levels of dependence and a lower probability of quitting [Reference Lê Cook, Wayne, Kafali, Liu, Shu and Flores8, Reference Diaz, James, Botts, Maw, Susce and de Leon9]. Recent meta-research, based on clinical samples and population databases, shows an association between SMI and the most frequent respiratory diseases [Reference Suetani, Honarparvar, Siskind, Hindley, Veronese and Vancampfort10, Reference Ruiz-Rull, Jaén-Moreno, del Pozo, Gómez, Montiel and Alcántara11], as well as a higher likelihood of altered respiratory parameters in spirometry [Reference Ruiz-Rull, Jaén-Moreno, del Pozo, Gómez, Montiel and Alcántara11–Reference Viejo Casas, Amado Diago, Agüero Calvo, Gómez-Revuelta, Ruiz Núñez and Juncal-Ruiz13].

Lung function is considered a marker of overall physical health [Reference Papi, Beghé and Fabbri14]. Spirometry is the gold standard for studying lung volumes in a simple, inexpensive, and noninvasive way [15]. The test defines several expiratory flow volumes: forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and the ratio between them (FEV1/FVC), all of which are associated with the risk of premature mortality in general population samples [Reference Duong, Islam, Rangarajan, Leong, Kurmi and Teo16]. Recently, the usefulness of this test for detecting individuals at risk and developing prevention measures has been highlighted [Reference Agusti, Fabbri, Baraldi, Celli, Corradi and Faner17].

As part of the longitudinal follow-up of a clinical trial designed for smoking cessation in people with SMI, we prospectively studied a sample of smokers with BD and SCHIZ. For the first time in individuals with SMI, and based on the hypothesis that respiratory function can help identify those at special risk in populations with a high probability of premature mortality, we evaluated the ability of different baseline lung volumes, measured by spirometry, to predict mortality in people with SMI.

Patient and methods

Design

This longitudinal, prospective, observational study was conducted at eight community mental health centers in Andalucia (southern Spain). The Reina Sofía Hospital Ethics Committee, Córdoba, approved the study (reference 4883, act no. 320).

Study population

In 2017, patients were recruited to participate in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the effect of a motivational tool for smoking cessation (see Jaen-Moreno et al. [Reference Jaen-Moreno, Feu, del Pozo, Gómez, Carrión and Chauca18]).

Patients were included in the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) age between 40 and 70 years; (2) diagnosed with SCHIZ or BD (as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision criteria); (3) active smokers (current consumption of at least 10 cigarettes per day with more than 10 packs/year for a cumulative consumption); and (4) clinical stability, defined as a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [Reference Bobes, Bulbena, Luque, Dal-Ré, Ballesteros and Ibarra19] score < 14, a Young Mania Rating Scale [Reference Colom, Vieta, Martinez-Aran, Garcia-Garcia, Reinares and Torrent20] score < 6, or a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [Reference Peralta and Cuesta21] score < 70 points. We excluded patients if they had (1) a current or previous respiratory disease, (2) a diagnosis of any pathology that contraindicates the performance of spirometry, and (3) a current psychiatric or cognitive state that significantly impaired ability to understand and follow spirometry instructions.

Study procedures

We offered follow-up under clinical practice conditions for patients who participated in the RCT and had validated spirometry results. We collected baseline data on sociodemographics, cardio-metabolic comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia), key predictors of mortality [Reference Teixeira, Almeida, Lavin, Barbosa, Alda and Altinbas22], psychiatric conditions, anthropometrics (abdominal circumference), vital signs, smoking habits, and physical activity. We assessed physical activity using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [Reference Roman, Majem, Hagströmer, Ramon, Ribas and Sjöström23], which allows us to calculate an activity index (based on metabolic equivalents of task [METS]) and a sedentary index. We conducted spirometry evaluations at each participant’s site using the DATOSPIR Touch Easy D+ spirometer (Sibelmed, Barcelona, Spain). The head of the Functional Test Unit in the Pneumology Service at Reina Sofia Hospital (Córdoba, Spain) assessed all spirometry measurements.

We conducted a mortality analysis with a data cutoff on December 31, 2022, using medical records to identify patients who died and the causes of death during the follow-up period.

Spirometry procedure

The spirometry procedures followed the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) standardization criteria [Reference Graham, Steenbruggen, Barjaktarevic, Cooper, Hall and Hallstrand24] for equipment validation, quality control, acceptability, and repeatability. A maximum of eight maneuvers was performed until three acceptable maneuvers were achieved. Reversibility testing involved repeating three maneuvers 15 min post-bronchodilation with salbutamol. FVC, FEV1, and FEV1/FVC were measured. Personnel were trained by the pulmonology service of Reina Sofía Hospital (Córdoba, Spain) and underwent accredited training covering theoretical principles, equipment handling, and spirometry performance [Reference Jaén-Moreno, Feu, Redondo-Écija, Montiel, Gómez and Del Pozo25]. Following the 2021 ATS and ERS standards [Reference Stanojevic, Kaminsky, Miller, Thompson, Aliverti and Barjaktarevic26], z-scores were calculated using the Global Lung Initiative reference equations, which are based on standardized values derived from the general population. Based on this procedure, the lower limit of normal (LLN) represents the cutoff values that fall outside the normal range (5th percentile or −1.645). The severity of lung function – FEV1, FVC, and the ratio FEV1/FVC (for all measures using the z-score) – was considered mild (−1.65 to −2.5), moderate (−2.51 to −4.0), or severe (<−4.1).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations (SDs), while non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves, with mortality as a dependent variable, were used to represent the differences between groups based on gender, the presence of cardio-metabolic comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia), and severity categories (mild, moderate, and severe) for the lung function parameters. These differences have been statistically tested by using the log-rank test.

Furthermore, univariate Cox proportional hazards regression (HR) analyses were performed to estimate potential risk factors and mortality associations. Variables included in the univariate analyses were age, gender, smoking status (pack-years), abdominal circumference (cm), presence of comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia), FEV1 z-score, FVC z-score, and FEV1/FVC ratio z-score.

Two separate multivariate Cox regression models were constructed to address potential multicollinearity and adjust for confounders. Variables that were significant (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis or exhibited trends (p < 0.1) were included in the regressions.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

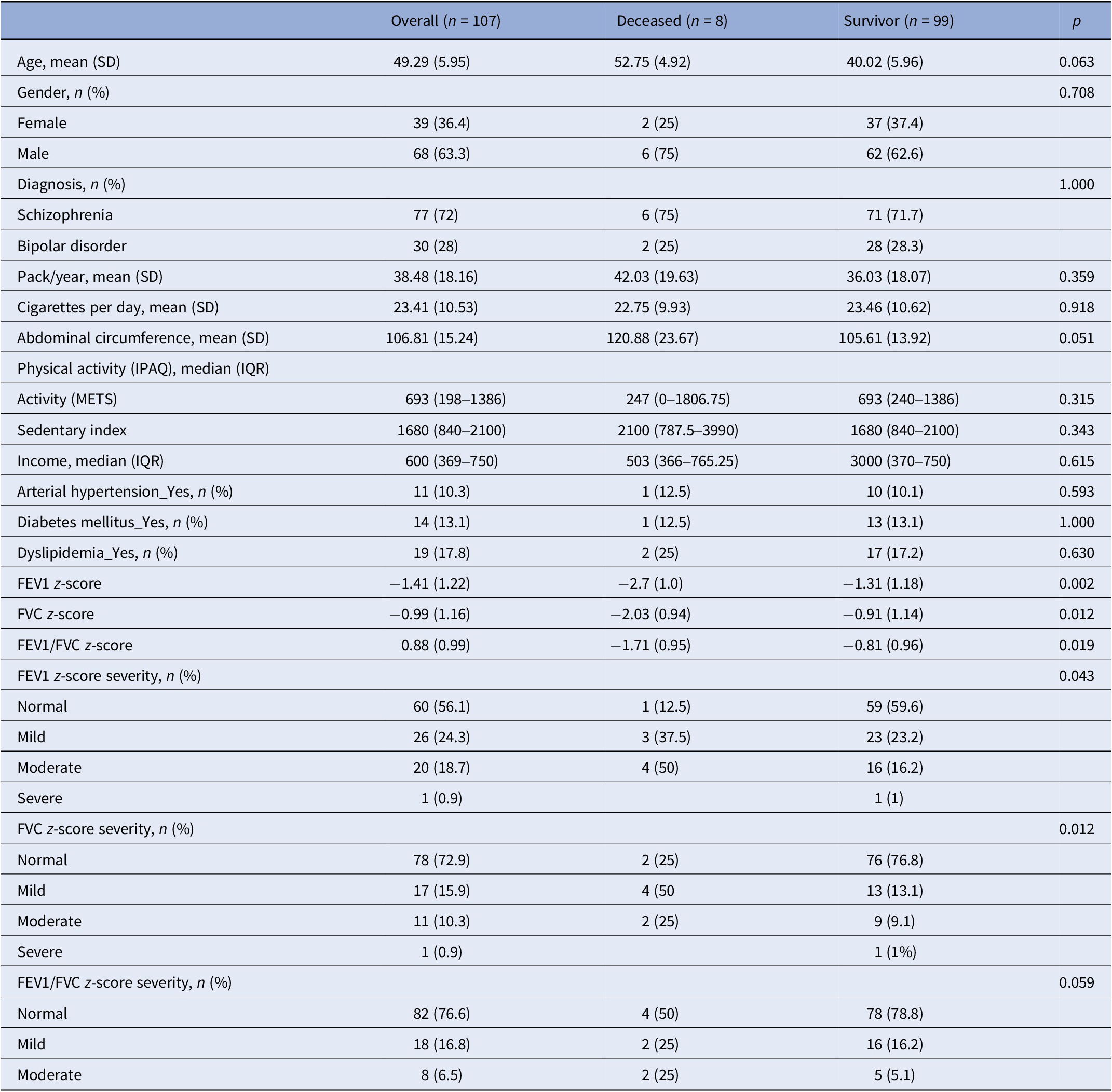

Our study included 107 participants diagnosed with SMI in the analysis. The mean age of the sample was 49.3 years, and 63.3% were male. Seventy-two percent were diagnosed with SCHIZ, and all participants were active smokers. During the follow-up, eight participants had a natural death. Three cases were attributed to oncological causes, while five were to cardiovascular ones. About the comorbidities, 13.1% of the sample had been diagnosed with diabetes, 17.8% had dyslipidemia, and 10.3% had hypertension. Regarding lung function parameters, z-scores for FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC were −1.41 (1.22), −0.99 (1.16), and 0.88 (0.99), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FEV1/FVC, ratio forced expiratory volume/forced vital capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity; METS, metabolic equivalents of task.

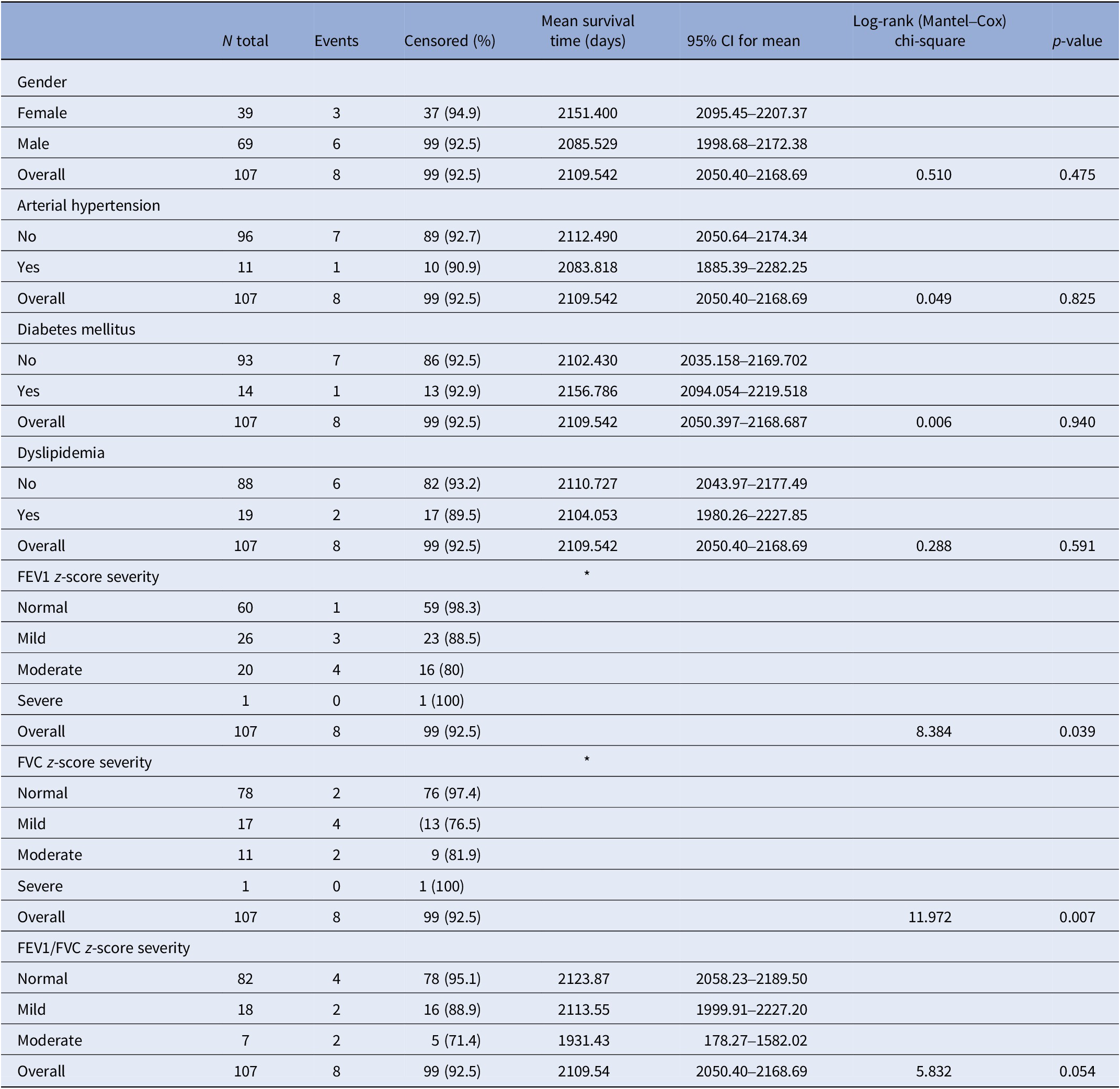

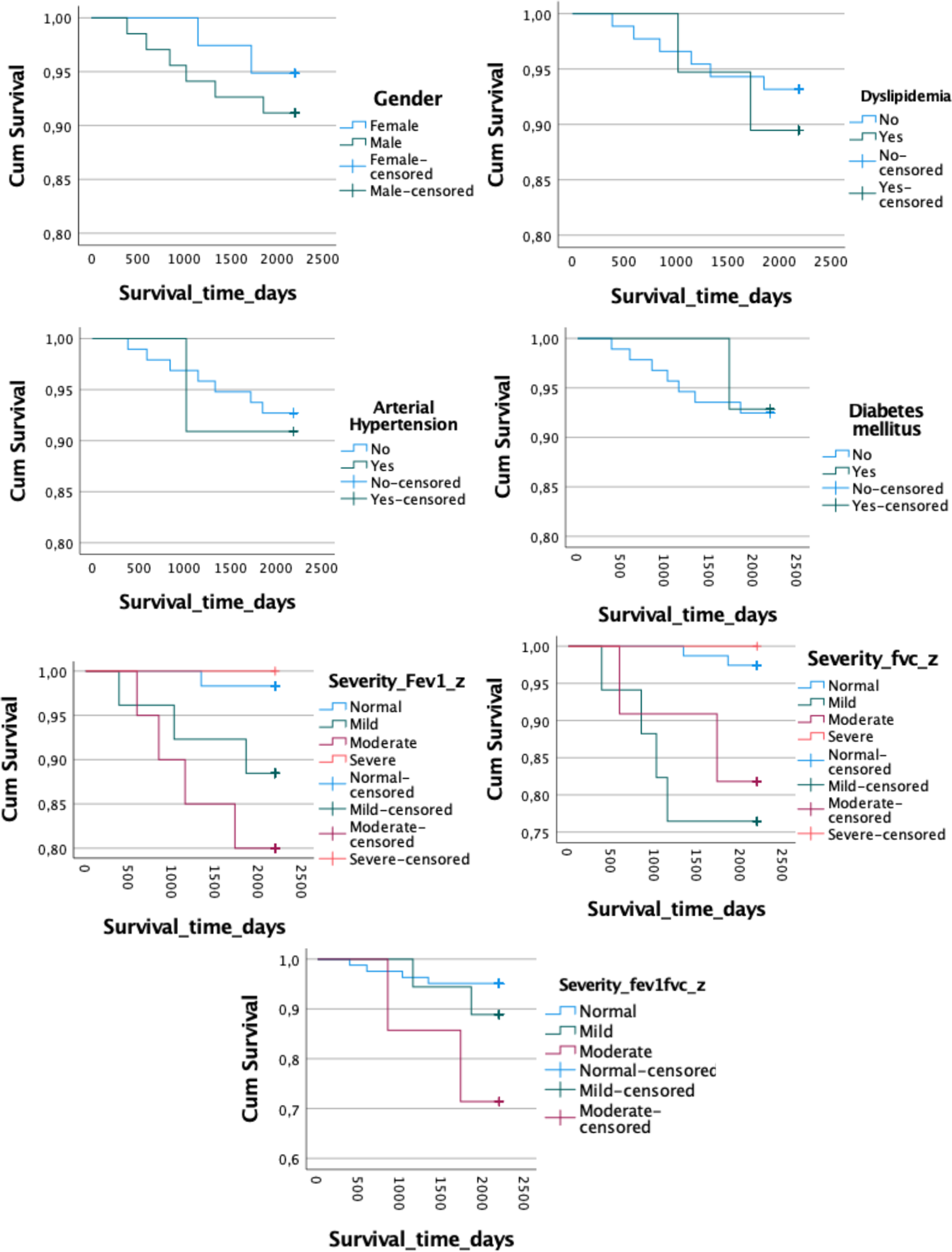

The Kaplan–Meier curves revealed no significant differences in survival time between the deceased group and survivors for gender (log-rank test, χ 2 = 0.510, p = 0.475) or the presence of hypertension (log-rank test, χ 2 = 0.049, p = 0.825), diabetes (log-rank test, χ 2 = 0.001, p = 0.940), dyslipidemia (log-rank test, χ 2 = 0.288, p = 0.521), or FEV1/FVC z-score severity (log-rank test, χ 2 = 5.832, p = 0.054). However, survival time differed significantly based on FEV1 z-score severity categories (log-rank test, χ 2 = 8.384, p = 0.039), and FVC severity (log-rank test, χ 2 = 11.972, p = 0.007; Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2. Kaplan–Meier curves

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FEV1/FVC, ratio forced expiratory volume/ forced vital capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity.

The significance is in the “overall” row at the same of the others variables.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier curves. FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FEV1/FVC, ratio forced expiratory volume/forced vital capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity.

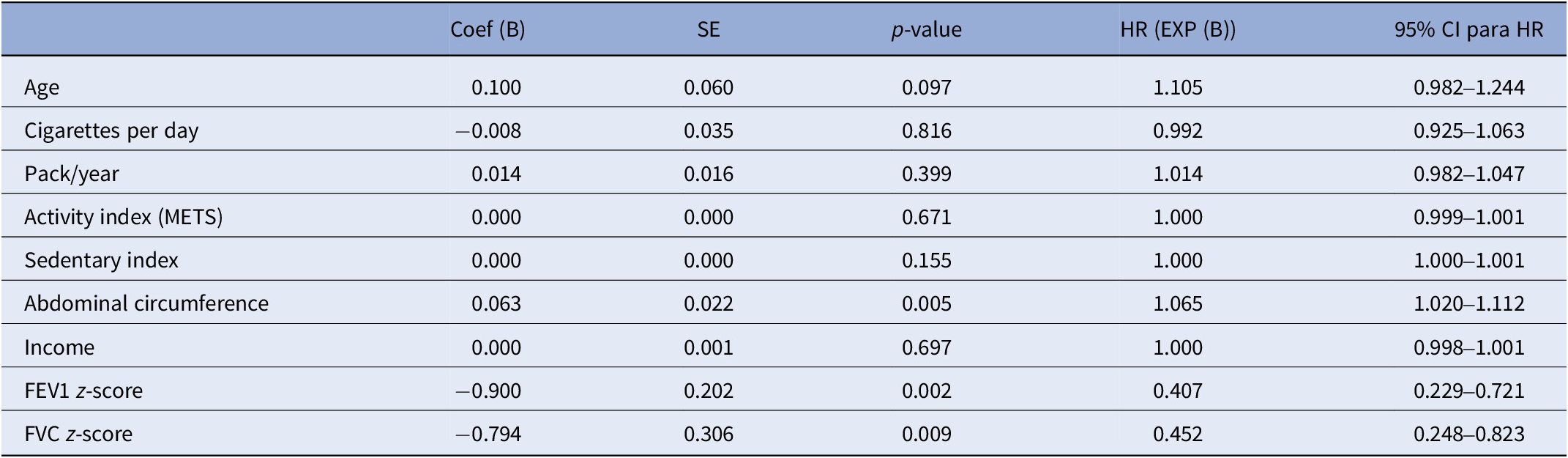

The univariate Cox regression analyses revealed that lower FEV1 z-score (HR = 0.407, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.229–0.721, p = 0.002), FVC z-score (HR = 0.452, 95% CI: 0.248–0.823, p = 0.009), and abdominal circumference (HR = 1.065, 95% CI: 1.02–1.112, p = 0.005) were significantly associated with an increased mortality risk in individuals with SMI, while age showed a nonsignificant trend toward an association with mortality (HR = 1.105, 95% CI: 0.982–1.233, p = 0.089). Other variables included in the univariate Cox regression (number of cigarettes, pack/year, activity index [METS], sedentary index, and income) were not significantly associated with mortality in our sample (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate Cox regression

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; METS, metabolic equivalents of task.

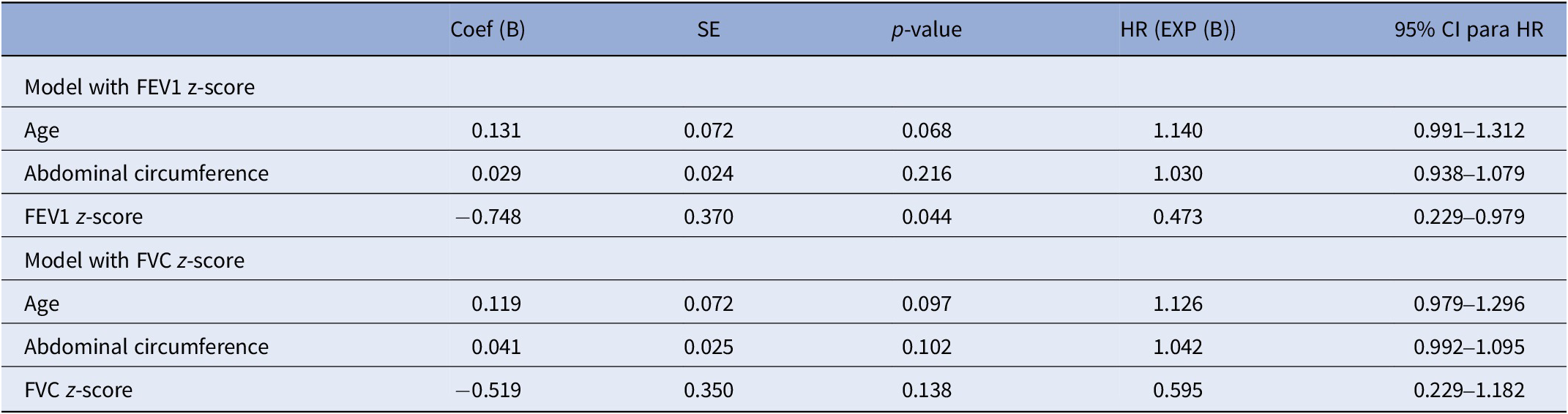

We constructed two Cox regression models to avoid multicollinearity based on the significant association observed in the univariate analyses. Each model included age, abdominal circumference, and one of the following lung function parameters: FEV1 z-score or FVC z-score (Table 4). Both models demonstrated a statistically significant overall fit, as indicated by the omnibus test of model coefficients (FEV1 model: χ 2 = 14.95, df = 3, p = 0.002; FVC model: χ 2 = 12.64, df = 3, p = 0.005). However, only the model with FEV1 demonstrated a statistically significant association between lower FEV1 (Coef (B) -0.748) and increased mortality risk (HR = 0.473, 95% CI: 0.220–0.979, p = 0.044).

Table 4. Multivariate models: Cox regression

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the predictive capacity of lung function on all-cause mortality in individuals with SMI, a population at high risk for premature mortality. In the prospective analysis of a clinical sample of middle-aged smokers with SCHIZ and BD, the lung function parameter FEV1 predicted all-cause mortality. Specifically, a lower baseline z-score FEV1 showed a significantly increased risk of death, adjusting with well-known mortality risk predictors, such as age, sex, abdominal circumference, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes.

The present results align with numerous previous studies that have demonstrated an association between reduced lung capacity and mortality risk in the general population [Reference Ashley, Kannel, Sorlie and Masson27–Reference Shibata, Inoue, Igarashi, Yamauchi, Abe and Aida30]. Although FVC has also been described as a robust predictor of mortality in the general population [Reference Godfrey and Jankowich31], FEV1 is considered a better predictor [Reference Menezes, Pérez-Padilla, Wehrmeister, LopezVarela, Muiño and Valdivia32, Reference Bikov, Lange, Anderson, Brook, Calverley and Celli33], even with a higher predictive power than blood pressure or body mass index (BMI) [Reference Gupta and Strachan34]. It is predictive even with mild-to-moderate volume reductions. It retains its effectiveness in nonsmoking populations, young individuals (under 50 years old), and healthy participants [Reference Duong, Islam, Rangarajan, Leong, Kurmi and Teo16], independent of other mortality risk factors, including cardiovascular ones [Reference Magnussen, Ojeda, Rzayeva, Zeller, Sinning and Pfeiffer35].

People with SMI are overexposed to a lifetime context of physical health risks, starting from intrauterine life throughout adulthood, which may also impact lung development and respiratory health. SMI is associated with an increased likelihood of prenatal tobacco exposure, low birth weight, preterm births, and early-life adversities [Reference Robinson, Ploner, Leone, Lichtenstein, Kendler and Bergen36] – determinant factors in reaching peak FEV1 in early adulthood, a central component in the current paradigm of respiratory health [Reference Agusti, Fabbri, Baraldi, Celli, Corradi and Faner17, Reference Agusti, Faner, Celli and Rodriguez-Roisin37]. Tobacco is the leading preventable mortality factor and the critical element in the reduction of FEV1 in people with BD and SCHIZ. These individuals have smoking rates of between 45 and 65%, respectively, younger onset, more intense smoking – depth and frequency of puffing – and a higher level of dependence [Reference Jaen-Moreno, Feu, del Pozo, Gómez, Carrión and Chauca18]. Other risk factors contribute to completing the complex network of environmental factors leading to a reduction in FEV1 and poor lung function among people with SMI: alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy dietary habits, metabolic syndrome, and poorer living conditions [Reference Agustí, Melén, DeMeo, Breyer-Kohansal and Faner38].

Despite the consistent relationship between respiratory diseases and SMI, respiratory function studies in that population are still scarce. However, in the last decade, three clinical samples of SCHIZ – one included BD – were studied by spirometry [Reference Ruiz-Rull, Jaén-Moreno, del Pozo, Gómez, Montiel and Alcántara11, Reference Viejo Casas, Amado Diago, Agüero Calvo, Gómez-Revuelta, Ruiz Núñez and Juncal-Ruiz13, Reference Vancampfort, Probst, Stubbs, Soundy, De Herdt and De Hert39] and one was extracted from a population database with SCHIZ and other nonaffective psychoses [Reference Filik, Sipos, Kehoe, Burns, Cooper and Stevens40]. Collectively, these studies confirm a higher frequency of altered respiratory patterns, with reductions in FEV1 and FVC, and their possible link with several risk factors, mainly to smoking, abdominal circumference, and metabolic syndrome. The longitudinal follow-up of one of the samples alerts suggests the possibility of an accelerated FEV1 decline in the first 3 years after detection, well above that described in the general population [Reference Ruiz-Rull, Jaén-Moreno, del Pozo, Camacho-Rodríguez, Rodríguez-López and Rico-Villademoros41]. Moreover, physical activity acted as a possible protective factor [Reference Ruiz-Rull, Jaén-Moreno, del Pozo, Camacho-Rodríguez, Rodríguez-López and Rico-Villademoros41].

In addition to the reduction in lung volumes, recent meta-research confirms that the risk of lung diseases, mainly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), is increased in the SMI population and especially in young people [Reference Laguna-Muñoz, Jiménez-Peinado, Jaén-Moreno, Camacho-Rodríguez, del and Vieta42]. Follow-up studies in high-income countries confirm high mortality rates due to COPD, with the risk being up to 11 times higher in individuals with SCHIZ and those under 50 years of age compared to the general population [Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup7]. Recently, in a community sample of individuals with SCHIZ and BD, with a mean age of 49 years and no previous respiratory symptoms, one in four patients was diagnosed with COPD, 80% of whom were at moderate or severe stage [Reference Jaen-Moreno, Feu, del Pozo, Gómez, Carrión and Chauca18].

The mechanisms linking low FEV1 to mortality are complex and not yet fully understood. Based on previous evidence from the general population, reduced FEV1 may appear within an obstructive (FEV1/FCV < LLN ratio) and pre-obstructive (preserved ratio) pattern, and thus is mainly linked to respiratory, cardiovascular, and oncologic pulmonary mortality [Reference Cestelli, Johannessen, Gulsvik, Stavem and Nielsen43]. In those patterns with preserved ratio and FVC < LLN, reduced FEV1 would be associated with mortality through metabolic disease and mainly cardiovascular and nonpulmonary oncologic risk [Reference Cestelli, Johannessen, Gulsvik, Stavem and Nielsen43]. In samples of smokers, such as the one we present, the relationship with mortality may also occur directly through the specific risks associated with smoking, and in all cases, through the link with the multiple risk factors previously described (unhealthy habits, physical inactivity, and socioeconomic determinants), which affect both overall physical health and respiratory health.

To date, results on the motivational value of providing spirometry test information for smoking cessation have been scarce and inconclusive in the general population. However, promising results have recently been described in a pilot study in which lung age was reported to smokers, who subsequently demonstrated high cessation rates at 12 weeks [Reference Khaldi, Derbel, Ghannouchi, Guezguez, Sayhi and Benzarti44]. Specifically in BD and SCHIZ, a controlled clinical trial that analyzed the value of spirometry-derived lung age information as a motivational tool demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of cigarettes/day and the biological measure of expired CO levels, as well as an increased likelihood of smoking cessation at 12 weeks [Reference Jaen-Moreno, Feu, del Pozo, Gómez, Carrión and Chauca18].

The evidence linking lung function and mortality risk is robust in the general population. The factors threatening respiratory health from lung development and through adulthood are common to those observed for other chronic diseases [Reference Duong, Islam, Rangarajan, Leong, Kurmi and Teo16], and the reduction in FEV1 may reflect a common, multiorgan inflammatory context [Reference Sin, Anthonisen, Soriano and Agusti45]. In any case, until there is a better understanding of these mechanisms, it seems that lung function – mainly through the reduction of FEV1 – could serve as “the canary in the coal mine,” alerting us to a broader risk to physical health. A simple, inexpensive, and therefore implementable test in the community care setting would permit identifying individuals with SMI at greater physical health risk and developing more intensive, individualized prevention actions of greater intensity. Such efforts should target mainly smoking cessation, but also the other highlighted risk factors.

Despite the strength of being the longitudinal design and of being the first study of its kind in an SMI sample looking into the observed independent predictive power of FEV1, some limitations should be considered when interpreting the present results. First, the relatively small sample size and lack of statistical power may have underestimated the true predictive power of FVC [Reference De Prisco and Vieta46]. It also limited the ability to discriminate mortality risk levels based on spirometry patterns and the presence or absence of respiratory symptoms, as well as its predictive value for the specific cause of death. Second, the variables analyzed were those measured at baseline, which did not allow us to assess the potential influence of a wider range of lifestyle factors and lung volume evolution on the mortality outcome [Reference Balanzá-Martínez, Kapczinski, de Azevedo Cardoso, Atienza-Carbonell, Rosa and Mota47]. Moreover, treatment was naturalistic, and its influence cannot be estimated [Reference Ilzarbe and Vieta48].

In summary, in a population at high risk of premature mortality, such as individuals with SMI, it is a priority to develop initiatives for a timely diagnosis and prevention. Longitudinal follow-up of larger samples will help confirm the results of lung damage described so far in the literature and those presented in this study regarding the predictive value of lung function on mortality. Deepening into the age ranges at greatest risk, severity levels depend on the degree of FEV1 reduction and the predictive value on cause-specific mortality. If replicated, spirometry could be an opportunity to diagnose COPD on time and identify individuals at a higher overall risk of mortality, enabling targeted, intensive, and individualized interventions.

Data availability statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients’ altruistic and generous participation in this project.

Author contribution

M.J.J.-M., D.L.-M., C.C.-R., and F.S. participated in the design of the study, collection of data, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. M.J.J.-M., I.G., and C.C.-R. participated in the interpretation of the data and in the drafting of the manuscript. I.G. and C.C.R. participated in the statistical analysis. G.I.d.P., V.B.-M., C.R.-R., and E.V. participated in the interpretation of the results and in the drafting of the manuscript. The rest of the authors participated in the collection of the data.

All the authors have critically reviewed the draft, given their final approval of the version to be published, and they agree to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/01657) and co-funded by the European Union.

Competing interests

E.V. has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, AbbVie, Adamed, Angelini, Biogen, Beckley-Psytech, Biohaven, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celon Pharma, Compass, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith Kline, HMNC, Idorsia, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Luye Pharma, Medincell, Merck, Newron, Novartis, Orion Corporation, Organon, Otsuka, Roche, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris, outside the submitted work. V.B., during the last 5 years, has been a CME speaker for Angelini, outside the submitted work. F.S., during the last 5 years, has been a speaker for Rovi and Janssen-Cilag. D.L.-M., during the last 5 years, has been a speaker for Lundbeck. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.