I Looking at the Roman empire from Remetschwil (Aargau, Switzerland)

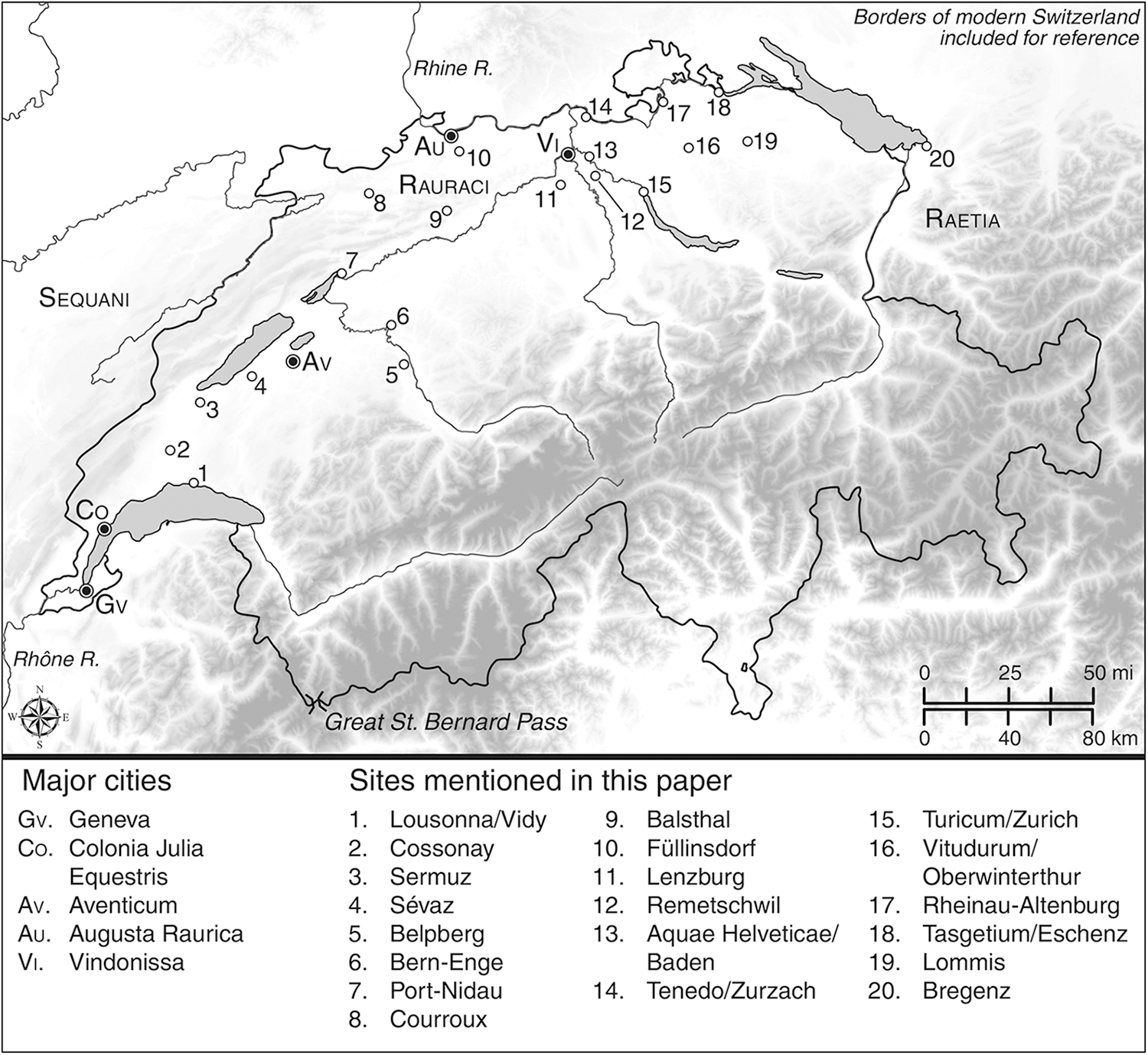

Switzerland, September 1948. A forestry guard, working on a tree nursery above the village of Remetschwil, uncovers an assemblage of pottery, glass, organic remains and corroded metal. The news excites the interest of a young enthusiast, Albert Conrad. He performs soundings. The find turns out to be a cremation tomb of the first half of the first century c.e. (c. 40 c.e.);Footnote 1 in fact, a Waffengrab or ‘weapons-grave’, that rarity in Swiss archaeology, especially for the LTD2 and Roman periods.Footnote 2 The findspot sits in one of the valleys leading to the Wasserschloss where the three great rivers of the Swiss Plateau converge (Aar, Reuss, Limmat) before joining the Rhine (Fig. 1).Footnote 3

Fig. 1. Sketch-map of ‘Roman Switzerland’ across the Swiss Plateau with rough indications of principal sites mentioned in this paper. Map by Gabriel Moss.

The tomb intrigued the great Swiss archaeologist Rudolf Laur-Belart. In a letter to young Conrad, he interpreted the tomb as that of ‘a Celtic warrior’ in the first century c.e., belonging to the Helvetian army described by Tacitus in the Histories (1.67–9). ‘From your fine discovery’, he mused, ‘we can see how in our regions, at the start of the Roman period, the old Gallic weapons culture and military independence had perpetuated themselves, and also how quickly Roman mores were adopted by the fickle Helvetians.’Footnote 4 Such musings about army, independence and identity reflect modern Swiss investments and anxieties; but they also touch upon the interest of the Remetschwil burial in its context.

Here I develop Laur-Belart’s insights. This paper rests on a formidable body of national scholarship by generations of Swiss archaeologists. I supplement the archaeological evidence with literary texts, inscriptions, and the plentiful numismatical material, found during excavation and surveying but also by metal detectorists. Furthermore, I connect the Remetschwil Waffengrab, and the archaeological work on ‘Roman Switzerland’ which forms its immediate context, to several important recent developments in the study of the material culture and social history of Gaul in the late Iron Age and early Julio-Claudian period, notably on militaria Footnote 5 and wine consumption.Footnote 6 I hence combine a survey of the archaeology with awareness of political history in order to study the Helvetian polity during the transitional period between the conquest of Gaul and the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (58 b.c.e.–69 c.e.).

Local agency plays a crucial role in my argument, as manifested in military capacities which should not be described merely as ‘auxiliary’ service. This viewpoint invites us to reinterpret the material record for militaria in Roman Switzerland between LTD2 and 69 c.e., and indeed across late Iron Age and early Roman Gaul. The implications go beyond the persistence of ‘militarism’ in eastern Gaul. The capacity of Gallic civitates in the first century c.e. to operate as state-like entities shaped the practice and the experience of empire. The present paper is written between event and structure, and between the local knowledge of regional archaeology and the broader perspectives of imperial history.

II The weapons-grave at Remetschwil

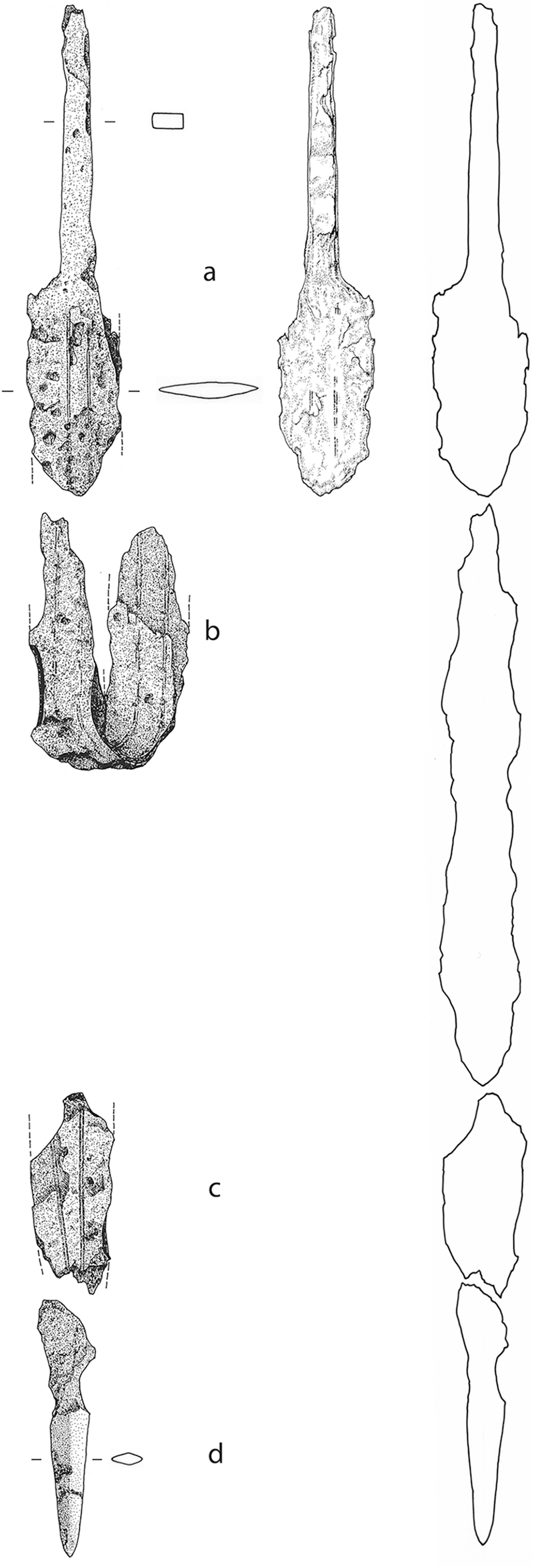

These may seem large claims to make before the pit at Remetschwil. The objects themselves are a bit unprepossessing. However, even a summary description reveals their interest. The first weapon is a sword: ritually folded, damaged by fire, corroded. Enough survives to reconstruct a straight lenticular-section blade, originally around 60 cm long, tapering to an elongated diamond-section point, reinforced for thrusting (Fig. 2). Such ‘Type-2’ blades were inspired by late-republican gladii but produced in the western provinces. Other examples are found at Port-Nidau (Bern), and at Goeblingen-Nospelt (Luxemburg), in Treviran territory.Footnote 7 (We will return to these places). The sword was accompanied by a round, domed shield boss (Fig. 3), reminiscent of Germanic types particularly well attested in the region of Trier (in Treviran territory, again).

Fig. 2. The Remetschwil hybrid gladius (after Berger et al. Reference Berger2007). © Kantonsarchäologie Aargau.

Fig. 3. The Remetschwil shield boss (from Berger et al. Reference Berger2007). © Kantonsarchäologie Aargau.

In addition, the finds included a single Hispanic amphora of the Haltern-70 type, which can be dated typologically to the ‘Tiberian-Claudian period’. Its tip was incised with some sort of symbol, the whole vessel broken into small sherds. This sort of offering (harking back to Iron Age practices) was a rarity in the early Roman Empire;Footnote 8 thus the first-century c.e. non-elite cemetery at Avenches at the site À la Montagne contains no amphoras.Footnote 9 A large globular ceramic bowl relates to drinking practices. Its dimensions (23.6 cm high, the diameter tapering from 22 cm down to nine, and containing nearly ten litres) suits the mixing of drink from the defrutum contained in the amphora. The bowl recalls (at a larger scale) types from late La Tène contexts found (yet again) around Trier. Finally, the soundings produced a fragment of imitation sigillata (from a plate of Drack-2 type) and a fragment of fire-damaged glass.

The amphora situates the tomb in the ‘Tiberian-Claudian’ period, while the Type-2 hybrid gladius finds parallels earlier, from the LTD2 and the early Augustan periods.Footnote 10 Heirloom or deliberate throwback? The larger question is to whom we should attribute this grave. I favour the solution intuited by Laur-Belart: a soldier serving in the Helvetian army, which Tacitus shows meeting a large Roman army with terrible results.

III The events of 69 c.e.

After Vitellius’ acclamation as emperor in early January 69 c.e., in Lower Germany, two battle groups marched down towards the passes into Italy, Fabius Valens striking through eastern Gaul, Caecina Alienus leading the second battlegroup down from Moguntiacum (Mainz) along the Rhine valley. Caecina reached the Swiss Plateau by early February.Footnote 11 Tacitus’ extensive narrative of both marches abounds in dramatic detail.Footnote 12 Caecina comes down the Rhine in haste, reaching the bend at modern Basel. There he crosses into the Plateau. He destroys the vicus at Baden (in modum municipii extructus locus, amoeno salubrium aquarum usu frequens, ‘a place built in the fashion of a town, frequented for the pleasant use of healthy waters’, 1.67.13). Modern excavation at the site of Baden (Aquae Helveticae) has revealed traces of destruction serious enough to alter the urban fabric.Footnote 13 The civilian settlement next to the legionary camp at Windisch went up in flames. Though there seem to be no clear archaeological traces of wholesale destruction across the western part of the Swiss Plateau, destruction layers c. 70 c.e. in eastern Switzerland, at Vitudurum/Oberwinterthur (Zurich), could relate to the Vitellians’ march.Footnote 14 Scattered burials of aurei down to Nero across the Plateau might also be connected.Footnote 15

Legio XXI Rapax plays an important role in Tacitus’ narrative in provoking Caecina’s vengeful progress (ultum ibat, 1.67.2).Footnote 16 Some legionaries hijack a convoy carrying the pay of a garrison maintained ‘of old’ by the Helvetians (rapuerant pecuniam missam in stipendium castelli quod olim Helvetii suis militibus ac stipendiis tuebantur, 1.67.1). Disastrously, the Helvetians respond by arresting envoys from the Germanic legions, bearing letters to the Danubian troops. Much is obscure here concerning motivations and topography. The location of the Helvetian fort is still uncertain, as is that of the final battle. What did Legio XXI do before Caecina’s arrival? Was it blockaded in Vindonissa? Caecina summoned reinforcements from Raetia (missi ad Raetica auxilia nuntii ut versos in legionem Helvetios a tergo adgrederentur, 1.67.2), but how were these supposed to attack the Helvetians ‘in the rear’, arranged as the latter were ‘against the legion’ after the sack of Baden (east of Vindonissa)? Does legionem designate Legio XXI or Caecina’s infernal column? Only the final scenes are securely located at Aventicum, modern Avenches (Vaud), the gentis caput (1.68.2).

Yet Tacitus’ narrative, despite unclarities and tendentious effects, provides an entry into provincial life,Footnote 17 starting with the initial incident. For Tacitus, the seizure of the pay of the Helvetian garrison is an act of greedy haste by Legio XXI Rapax — part of the general anarchy of civil war. But Tacitus notes that the Helvetian fort and its garrison were an ancient institution by 69 c.e. (olim).Footnote 18 Both the existence of this fort and its history are highly instructive for the workings of the Helvetian civitas and its place within the development of Roman imperialism in Eastern Gaul.

IV Helvetian institutions and autonomy 58–15 b.c.e.

In Caesar’s account, we see that the Helvetians in 58 b.c.e. had political institutions which allowed them to organise their attempted migration. These institutions are particularly striking because the Helvetian polity itself only emerged around 100–80 b.c.e.Footnote 19 Among these institutions were officeholders with the capacity to put on trial the powerful aristocrat Orgetorix; when he called in his partisans, the Helvetians responded by mustering military forces. The tensions of a segmented, competitive society existed within the framework of an organised and capable state. The Helvetians must have had their own financial institutions, namely taxes and tolls, comparable to those mentioned for the Haedui. These might have been collected at fortified points at the sites near modern Avenches and Zurich.Footnote 20

Financial and political institutions are implied by the numismatic evidence. Even before the emergence of the Helvetian polity, the Swiss Plateau had used coins from eastern Gaul, perhaps for military and political purposes, for instance hiring mercenaries or paying tribute.Footnote 21 Such practices continued after c. 80 b.c.e., when the Helvetians struck their own silver quinarii (inaugurating what Swiss numismatists call the Silberhorizont in the material record).Footnote 22 Payment for troops may have been particularly necessary in eastern Gaul because of the turbulent political competition between powerful Gallic polities and the involvement of violent actors from across the Rhine. These circumstances would provoke the intervention of a particularly active Roman proconsul in 58 b.c.e. Finds of silver coins from fortified sites at the eastern end of the Plateau, namely Bern-Enge and Rheinau (Zurich), may be connected to military activity in the first part of the first century b.c.e.Footnote 23

Analogously, the neighbouring nation of the Rauraci may have kept paid troops (even though they were subordinate to the Sequani). This is suggested by two large hoards of silver coins dating to the first half of the first century b.c.e. These were found at strategic points of Rauracan territory, namely Balsthal (Solothurn) and Füllinsdorf (Basel) at both ends of the route from the Plateau though the Jura to the Rhine bend.Footnote 24 Additionally, I suggest that Republican denarii deposited at Füllinsdorf in the first century c.e. circulated earlier as payment for troops.Footnote 25 The large size of the hoards and their strategic location reinforce the ‘military’ interpretation.Footnote 26 Other finds of silver coins at urban sites such as Basel and Tarodunum/Kirchzarten (Baden-Württemberg) could likewise be military in purpose.Footnote 27 In addition, hoards found in the countryside, some very substantial like that from Nunningen (Solothurn), could have paid for rural garrisons or patrols.Footnote 28

The troops paid by the Helvetians and Rauracans might have been local rather than mercenaries. Celtic polities likely raised standing continents of ‘crack troops’ comparable to the late Classical Greek epilektoi; we might call such salaried troops ‘guardsmen’.Footnote 29 It is also possible that the Helvetians compensated conscripts in cash during campaigns, as Greek poleis and Italian medieval communes did. After 52 b.c.e., the Helvetians probably continued to pay for locally recruited troops, as suggested by late first century b.c.e. and early first century c.e. concentrations of silver coinage at the fortified sites of Sermuz (Vaud) and Bois-de-Châtel near Avenches.Footnote 30 A similar interpretation may apply to hoards dating to the 40s or 30s b.c.e. and found at Deitingen (Solothurn) and especially Belpberg (Bern). The latter hoard combined 61 Helvetian quinarii with 40 Roman denarii and was buried between 42 and 32 b.c.e.Footnote 31 Later on, Helvetian guardsmen were doubtless paid with Roman currency after the disappearance of the quinarii, though there is no numismatic evidence.Footnote 32

The assumption that silver coinage was in the main meant for military purposes is difficult to substantiate conclusively.Footnote 33 Yet it is worth emphasising that the abundant numismatic evidence from the Swiss Plateau after 80 b.c.e., if interpreted as military payments, gives crucial background to the events of 69 c.e. Conversely, the presence of pay for Helvetian guardsmen in 69 c.e. provides support for the military uses of silver coinage in earlier periods. The pay chest seized by Legio XXI belonged to an ancient institution connected with the martial history of Celtic polities. Additionally, Tacitus shows that the Helvetian civitas could muster a levy numbering in the thousands (just as they did in 58 b.c.e. during civil unrest). The civitas had administrative institutions to manage its manpower, as part of its state-like apparatus.Footnote 34 The epigraphical evidence, characteristically eloquent on elite benefaction and civic honours, remains silent on the mechanisms of local self-government.Footnote 35

Traces of state-like capacity are relevant to the specific crux in the history of the Helvetians, namely whether in 69 c.e. the civitas was foederata. The status is attested in Cicero but Pliny the Elder, in his list of Gallic civitates (and specifically in the section surveying Gallia Belgica), does not mention it for the Helvetians.Footnote 36 I propose that an alliance with Rome came as a reward for activities during the Civil Wars or Triumviral period; for instance, the capture of Caesar’s murderer Decimus Brutus in 43 b.c.e.Footnote 37 This is exactly the period of the Belpberg hoard. The omission of the status in Pliny would then be due to either faulty transmission, or Pliny’s source predating the alliance.

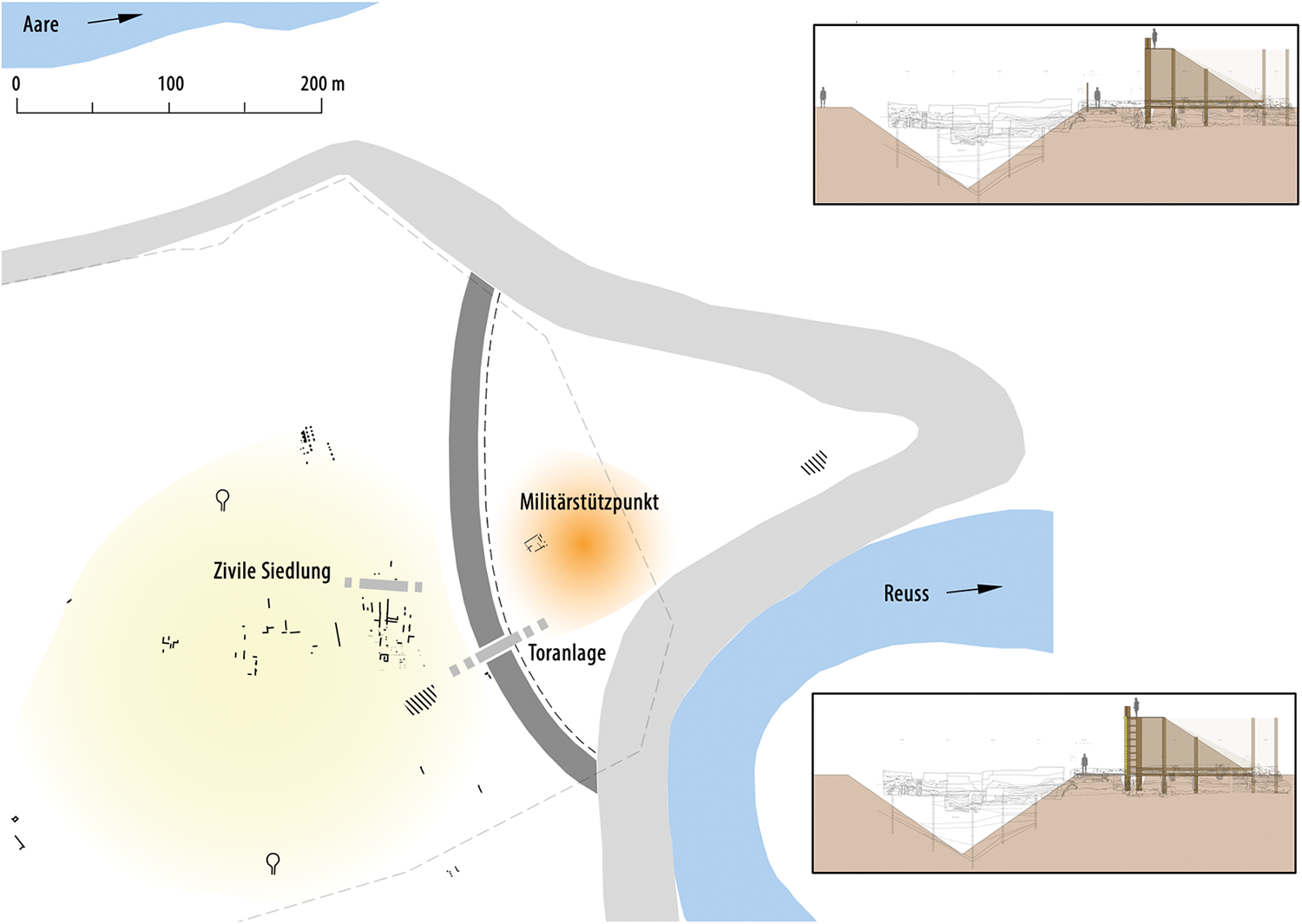

Autonomy had its role to play within the Roman Empire. In 58 b.c.e. already, Caesar envisioned the Helvetians (resettled home after their defeat) as a bulwark against the Germans.Footnote 38 Additionally, the Helvetians contained Raetian incursions along the Rhine or down Alpine corridors.Footnote 39 The fort mentioned in Tacitus as held by a Helvetian garrison could have worked to this end, if it was located at Turicum/Zurich, on the Walensee–Zurich corridor (Fig. 1), or further east.Footnote 40 In addition, I would like to suggest (in contrast with current interpretations) that the archaeology of the early phases of Vindonissa fits the presence of a Helvetian garrison. The Windisch spur was protected by a set of LTD2-dated timber-framed fortifications. These were refaced, in the early Augustan period, with a new, Roman-inspired technique (the timber posts are embedded in a continuous trench rather than individual post-holes); yet the whole site does not seem to have been occupied by Roman troops (Fig. 4).Footnote 41 The new wall likely protected a fortified position of the Helvetian civitas. The substantial presence of silver coins, mostly quinarii, may have paid Helvetian guardsmen.Footnote 42 In other words, I propose that this fort, protecting the Rhine frontier, was one anchor of the Helvetian military system, the second being the fort mentioned by Tacitus, set further back in Helvetian territory and directed mainly against the Raetians from the East.

Fig. 4. The Windisch spur with the two stages of its timber-faced fortifications (after Flück Reference Flück2022a). © Kantonsarchäologie Aargau.

Such an arrangement fits within the historical and military geography of the Swiss Plateau (Fig. 1). Colonia Julia Equestris, at Nyon (Vaud), founded in the 40s, kept watch over the Plateau and the route towards Geneva and the Little St Bernard Pass. A colony founded by L. Munatius Plancus in 44 b.c.e. (probably on the site of modern Basel) was meant to control the strategic bend of the Rhine. The Helvetians (granted autonomy and alliance during the Triumviral period) stood to fend off Germans and Raetians in the early Augustan period.Footnote 43 They hence existed as a free and allied state within Gallia Belgica. Likewise, the Rauraci (granted freedom from the Sequani) held a fortified settlement at Basel-Münsterhügel, fulfilling the military functions of Munatius Plancus’ foundation once the latter had disappeared.Footnote 44 The Balsthal and Courroux hoards (above) could date to this context. A parallel for the role of Helvetians and Rauraci is the contribution made by the Batavians at the other end of the Rhine frontier zone. Despite obvious differences (the Batavians were a Germanic community which was displaced and installed on the hostile lower Rhine, in a process of imperially sponsored ethnogenesis), the Batavians also developed a martial culture connected to their position on the Roman frontier.Footnote 45

V Autonomy, obsolescence and charivari: 15 b.c.e.–69 c.e.

By 69 c.e., the Helvetians’ role had long been an anachronism, their contribution superseded by more recent developments in Roman imperialism, namely the conquest of the Alps in 15 b.c.e., the subsequent campaigns in Germany, the creation of a military frontier zone along the Rhine and the emergence of regular auxiliary units integrated in the Roman army.Footnote 46 The Helvetian fortress was rendered obsolete by the conquest of Raetia and by military posts in the Walensee corridor. Turicum/Zurich probably received a Roman military detachment at this point.Footnote 47 Roman establishments appeared in the Rhine valley, at Basel-Münsterhügel and at Kaiseraugst (soon succeeded by the colony of Augusta Raurica). The military contribution of the Rauraci now ceased: at Füllinsdorf, the appearance of caliga hobnails, dated typologically to the mid- or late Augustan period, suggest that Roman troops took over from a Rauracan garrison.Footnote 48 At Vindonissa, the reinforced late La Tène fortified spur was taken over by a Roman detachment.Footnote 49 Konstanz and Bregenz also received Roman forts. The whole stretch of the Rhine from Basel to Lake Constance was militarised and manned by regular Roman troops.

The Helvetians kept their military institutions, but under conditions of rapidly increasing irrelevance. Roman forts appeared on the right bank of the Rhine when the Roman frontier shifted yet further away from what had been the Helvetian advanced positions. Under Tiberius, the fortified spur at Vindonissa was abandoned, its walls demolished, and the large new legionary camp was built on the Plateau to the west of the spur, to be occupied by Legio XIII Gemina, then Legio XXI Rapax. Under Claudius, the opening of the Great St Bernard Pass facilitated direct communications between Italy and the Rhine (as illustrated in 69 c.e.). An anachronism along the Roman frontier, the Helvetian fort — the sole remnant (I believe) of a mightier in-depth defence system — continued to fulfill its role for the Helvetians, namely expressing autonomy and partnership in empire. On those grounds, the Helvetians staked out their territory, especially at the northern end where it was fluid and meshed with the Roman military zone, and where the fort at Vindonissa threatened to cut off the eastern territories from the rest of the civitas. The eastern fort and the regular conveying of military pay from Aventicum to the fort made clear the Helvetians’ conception of their territory. Furthermore, the Helvetians could claim on the basis of their military contribution that they should be exempt from contributions to support the Roman army on the Upper Rhine frontier. Mommsen suggested that the Helvetian troops served to guard the communications between the Great St Bernard and the Rhine.Footnote 50

The seizure of pay by men of Legio XXI Rapax was not merely plunder, but an act of political communication, contesting the Helvetians’ claims and making clear that local resources, which the Helvetians drew on for their own antiquated military arrangements, should rightfully go to the Roman army. The convoy of military pay, journeying past the great legionary camp to the eastern fort, had long been an irritating statement as well as a concrete temptation. The heist of 69 c.e. was a piece of serious charivari by the legionaries, in whose eyes there was perhaps no difference between the Helvetians and the Raetians who garrisoned their own fort.Footnote 51 The response by the Helvetians was equally symbolical. The arrest of the Vitellian couriers demonstrated autonomy within their territory, just as the arrest and execution of Roman citizens was sometimes attempted by Greek cities during the Julio-Claudian period.Footnote 52 Furthermore, the Helvetians showed their autonomy by deliberately intervening in imperial politics (supporting Galba, whose death they had not yet heard of, against the German legions), just as the Lingones and Treviri actively had opposed Vindex the previous year.Footnote 53 Things got out of hand once the actual Vitellian armies burst onto the scene, leading to violent and ironical outcomes: plunder by the Raetians whom the Helvetians had once been set up to contain, massacre by units from other frontier provinces such as Thrace.Footnote 54

VI Military culture on the Swiss Plateau 52 b.c.e.–50 c.e.

What were the cultural consequences of militarism and local autonomy? It would be tempting to turn to the religious sphere and look for traces of military identity and political autonomy — for instance to the cult of Mars Caturix, preserving the name of a Celtic god of war.Footnote 55 However, the evidence is scanty and inconclusive (the few inscriptions are impossible to date). A fragmentary bronze inscription from Avenches, a metrical dedication addressed to Mars Gradivus mentioning the dedicator’s fatherland and fellow-citizens (hanc patriam cive[s ?]), is also impossible to date and remains enigmatic.Footnote 56

Hence the interest of the Remetschwil weapons-grave. It prolongs late La Tène practice, asserting ‘martiality’ (N. Roymans) alongside high social status.Footnote 57 The inclusion of an amphora and of a mixing-bowl with the grave goods harks back to old claims to status based on consumption and feasting, characteristic of the ‘Wine Age’ of independent Gaul.Footnote 58 These echo Tacitus’ remark about the Helvetian memory of a glorious military past (Gallica gens olim armis virisque, mox memoria nominis clara, ‘a Gallic nation, famed in the past for its weapons and its men, then for the illustrious memory of its name’, Hist. 1.67.1). The Remetschwil warrior fits within the martial culture and the institutions of the free civitas of the Helvetians. At the same time, the hybrid gladius (Fig. 2) reflects Roman influence since it implies shifts in body technique but also in visible material identity and masculinity.Footnote 59

The cultural meanings of the hybrid gladius are brought out by L. Pernet’s brilliant analysis of an earlier statue (late first century b.c.e.) found far from Switzerland, at Vachères (Vaucluse), in the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis (Fig. 5). The torc-wearing figure has a hybrid gladius on his right hip, in a Roman-style scabbard with four suspension rings. But these hang empty: the sword is rigged up with a leather sleeve which, we are to understand, allows the man to hang his weapon off a separate side strap: he wears his gladius like a La Tène sword with its complex suspension system. The statue carefully represents this arrangement, complete with unused suspension rings.Footnote 60 Militaria result from practical choices, political constraints and identity-performance.Footnote 61

Fig. 5. Vachères warrior. Limestone, preserved height 1.53 m. © Institut Calvet.

In reflecting the paradoxes of military autonomy under empire, the Remetschwil weapons-grave invites similar analyses for other weapon finds in Switzerland. Instead of interpreting them as products of the Roman army,Footnote 62 we should read them in relation to the long-standing Helvetian militia. (Naturally, I will not consider material contexts clearly connected to the Roman military, such as the legionary fort at Vindonissa and nearby sites.)Footnote 63 The survey below proceeds chronologically, starting in the late first century b.c.e. and ending with 69 c.e., with attention to the context of retrieval.

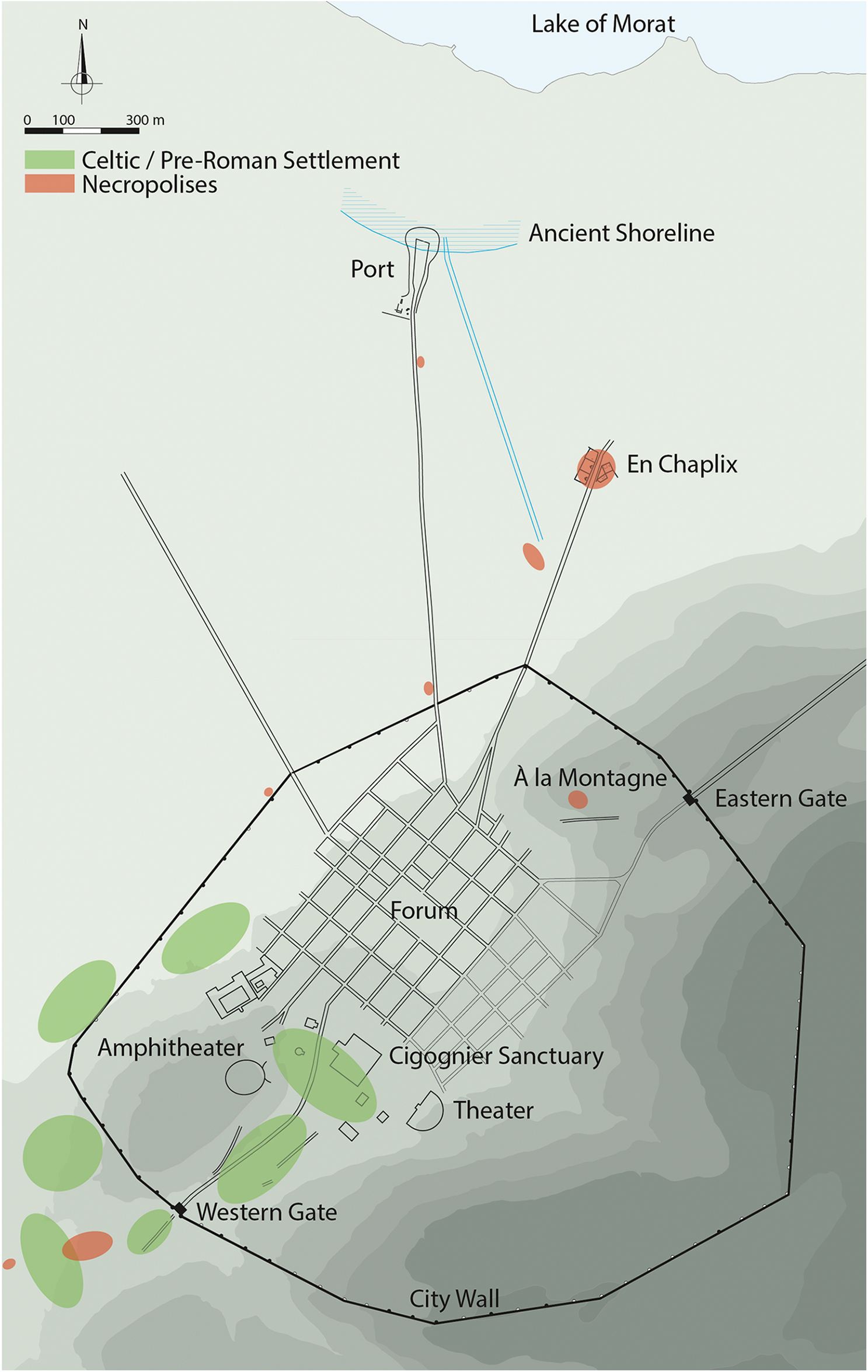

From sacred contexts at Port-Nidau (Bern) and Bern-Enge come artifacts dated typologically to the late first century b.c.e. (LTD2b): a long hybrid Type-2 gladius and iron helmets of late La Tène style, showing that Helvetian military men of this period might have looked like the Vachères statue, combining Celtic with Roman(-inspired) equipment (Fig. 6).Footnote 64 In spite of the Roman inspiration of the gladius, and the late emergence of the Port-Nidau type helmet (see below, Section IX), there is no reason to consider this as the equipment of Roman soldiers; it rather equipped the men who held the Swiss Plateau against Raetian raids, before 15 b.c.e. Similar militaria (including a helmet fragment and shield edging) dated to LTD2b and the early Augustan period have appeared to the south-west of the later Roman city at Aventicum. These finds show the existence of a ‘Celtic’ predecessor settlement (Fig. 7).Footnote 65 The Remetschwil gladius, buried c. 30–40 c.e., might reflect deliberate continuity in self-fashioning with the military style of this era; the folding of the blade is another old-fashioned trait (this must be the latest example of the practice in the Swiss archaeological record). As emphasised by Daniel Goldhorn, the details of the weaponry suggest a combination of indigenous traditions and Roman influence.Footnote 66 The material is contemporary with numismatic finds of silver (Belpberg, Sermuz, Avenches, Bois de Châtel)Footnote 67 and the first phase of fortifications at the Windisch fortified spur.

Fig. 6. Port-Nidau weapon finds. Sword, L. 740 mm. Top helmet (Alesia type), H. 150 mm. Bottom helmet (the name helmet for Port-Nidau type), H. 175 mm. (Bern Historical Museum inv. 13714, 26452, National Museum Zurich inv. A5520). From Pernet Reference Pernet2010, figure 188, drawing on Wyss et al. Reference Wyss, Rey and Müller2002: nos. 82, 159, 160. Courtesy of L. Pernet.

Fig. 7. Avenches with recent explorations of the pre-Roman city. © Site et Musée romains d’Avenches.

In a different register, around 10–20 c.e., a burial near Sévaz (Fribourg) contained a rather old-fashioned looking spearhead (reminiscent of second-century b.c.e. examples), a single-edged knife and a belt with a decorated metal buckle; the cremated remains were placed in an amphora (Fig. 8).Footnote 68 Rather than hunting-gear as Dominique Bugnon proposes, the material might be the military equipment of a local big-man. The spear might allude to military status, and the big knife and amphora to feasting, i.e. wine-drinking and meat-carving. Despite differences in contexts and appearance, the Sévaz burial and the Remetschwil weapons-grave share an antiquarian orientation, linked with social structure and community identity.

Fig. 8. Material from the grave of the Sévaz ‘big man’. Drawing by M. Humbert and R. Marras. © Service archéologique de l’Etat de Fribourg (SAEF).

If one leaves aside the occasional appearance of militaria in single farmhouses and the isolated Remetschwil burial, the most important finds come from secondary settlements, namely Lenzburg (Aargau) or Turicum/Zurich.Footnote 69 Vitudurum/Oberwinterthur (Zurich) constitutes a particularly rich case. At this last site, excavations of several neighbourhoods have revealed over the last decades a remarkable concentration of first-century c.e. militaria, including fragments from gladius furniture, a variety of iron points, belt-plaques, equestrian harness-pieces, fittings for chainmail, and even helmet fragments and segmented armour.Footnote 70 About 20 km east of Vitudurum, near Lommis (Thurgau), a cremation grave contained a well-preserved Pompeii-type gladius, datable to 60–80 c.e. on the basis of typology.Footnote 71

The largest assemblage of militaria is found at Avenches (Fig. 7).Footnote 72 Chronologically relevant finds include spears, two gladii of the ‘Pompeii’ type of which one is datable stratigraphically to the second half of the first century c.e. (Fig. 9), and gladius scabbard furniture datable stratigraphically to c. 50 c.e.Footnote 73 Recently, a fragment from another gladius (specifically a piece of the bronze backing of the wooden guard) and an iron javelin head or bolt point with a quadrangular section have been found in a mid- to late first-century c.e. context of habitat and workshops.Footnote 74 Finds of defensive armament and kit include two elements of segmented armour (but the stratigraphical dating of these fits loosely between the first and second centuries c.e.), elements from the Roman-style belt apron (one piece is datable to the Augustan period), and decorations from horse-harnesses (perhaps paralleled in finds from the settlement at Bern-Enge).Footnote 75 A complete glass military medal (phalera) represents Agrippina Maior, likely Claudian in date; it likely rewarded military service in a Roman unit.Footnote 76 This find reminds us that, as shown by an honorific inscription, the Helvetian notable C. Julius Camillus served as a military tribune in a Roman legion on the Rhine, IIII Macedonica (under — the future emperor! — Ser. Sulpicius Galba, legate of Upper Germany), and was recalled to serve in Britain with Claudius, who decorated him with the hasta pura and a golden crown.Footnote 77

Fig. 9. ‘Pompeii’-type gladius, Avenches. Iron, bone, ivory, L. 690 mm. Avenches Museum, inv. 96/9933-01. © Site et Musée romains d’Avenches.

VII Interpreting Late Julio-Claudian militaria in the Helvetian context

It is immediately noticeable that the profile of the Vitudurum and Aventicum material does not look like that from Port-Nidau, Bern-Enge, Sévaz or Remetschwil. It simply appears more ‘Roman’. The usual reflex has been to assign such material to the Roman army. But the view that the Swiss Plateau saw a sustained Roman military presence is problematic. I would like to reexamine the evidence and argue for an at least partially different interpretation.

The material at Vitudurum has been explained variably, but always in connection with Roman presence: a Roman outpost complete with workshops, troops on the march, or settled veterans. Strikingly, a fragment of writing-tablet explicitly relates to the Roman army: it bears the mention of (centuria) Exomni, ‘(e.g. soldier) of the centuria of Exomnus/Exomnius’.Footnote 78 At the very least, the evidence is compatible with the passage of elements from the Roman troops based at Vindonissa. M. Reddé has observed, in the context of Gaul, how Roman military units travelled far afield on logistical missions.Footnote 79

However, the isolated and undated writing tablet cannot by itself constitute a decisive argument. There might have been a temporary outpost set up during the campaign of 15 b.c.e., but, as noted by Thomas Pauli-Gabi, ‘there is up to now no positive evidence for a durable presence of the Roman military.’Footnote 80 Many of the militaria are found mingled with ‘civilian’ artifacts such as jewellery or mirrors, which argues for their being the property of members of the local population. The Lommis gladius has been interpreted as that of a Roman veteran,Footnote 81 but this interpretation is doubtful on the grounds of distance from Vindonissa (about 60 km away as the eagle flies). Additionally, there is no clear epigraphical evidence for the passage or presence of soldiers or veterans in eastern Switzerland, in the form of votives, building inscriptions or tombstones (whereas such inscriptions abound at Windisch and its environs).Footnote 82

Likewise, the scanty militaria at Turicum have been interpreted as the sign of a Roman military detachment stationed there. The main argument is that they coincide with massive changes in material culture, namely the importation of ceramics and containers from a much wider horizon than prevalent in the late Iron Age site: amphoras from the eastern Mediterranean, dolia, Italian sigillata, etc. Yet this new profile coexists with traces of older material culture (notably ceramics), which hint at the continuity of population with the older Celtic settlement and generally share traits with sites on the remainder of the Swiss Plateau. As at Vitudurum, the militaria are found in civilian contexts.Footnote 83

At Aventicum, the militaria have been interpreted as the property of legionaries detached from Vindonissa or of veterans retaining their weaponry. In addition, as in north-eastern Switzerland, it is possible formations kept watch over supply routes and communications. But it is difficult to imagine a massive presence of Roman detachments and Roman veterans over 110 km away from Vindonissa, without any separate infrastructure for command, logistics, or supply. Such an interpretation is difficult to reconcile with the description in Tacitus of a polity with a strong military identity and institutions. In addition, the same dearth of epigraphical evidence for the presence of the Roman army can be seen for the area around Avenches as for north-eastern Switzerland (of three tombstones of soldiers from Avenches, two date to the Flavian period).Footnote 84 Mommsen’s suggestion (see above, Section V), namely that the Helvetian polity watched over the security of communications on the Swiss Plateau, retains its attraction.

Obviously, the Helvetians’ territory was not sealed off. The presence of the military frontier and the huge camp at Vindonissa entailed contact with the Roman state and army. But even if it is possible that some of the militaria at Avenches, Zurich and Oberwinterthur (along with the writing tablets mentioning centuriae) relate to movements by Roman troops across Helvetian territory, it is unclear on what scale. At any rate this explanation cannot account for all the militaria. Many or most of the first-century c.e. Roman-looking militaria of Avenches likely were used by Helvetian militiamen, living in the urban settlement of the civitas. I favour a similar explanation for the militaria from Vitudurum and Turicum. Such an analysis is consistent with a finding by Michel Feugère and Matthieu Poux: militaria in Gaul from the first century c.e. onwards tend to concentrate in urban contexts.Footnote 85 The material record of militaria in civilian context suggests that Vitudurum might have been the site of the Helvetian fort of 69 c.e., though there is currently no evidence of fortifications.Footnote 86 At Aventicum, the ‘Roman’ militaria should be viewed as a prolongation of the LTD2b and Augustan-era militaria found at the Celtic settlement next to the site of Aventicum. The likeliest explanation is that the population of this settlement (including its military men) relocated to Aventicum, and that the ‘Roman’ militaria belonged to their descendants.

A possible objection to this interpretation is the lack of any numismatic evidence which could be associated with military payments (already noted in Section IV), in contrast with the plentiful silver Celtic coinage found on the Swiss Plateau and indeed at Avenches itself. However, it may be that the need for military pay, and indeed the rate and frequency of mobilisation, was less intense in the Julio-Claudian period than during the tumultuous first century b.c.e. Another objection is the presence of elements of segmented armour at Aventicum and Vitudurum, since this is usually associated with legionary troops.Footnote 87 We could assign these fragments to the Roman troops passing through Helvetian territory that even my reconstruction admits. Alternatively, we could imagine the Helvetian militiamen experimenting with such equipment.

The upshot is that by c. 50 c.e., the Helvetian militiamen had adopted a ‘Roman’ look with gladii and military ‘apron’. Paradoxically, the Helvetian army, embodying an autonomous civitas allied to Rome, was converging with the Roman imperial army in terms of material culture. This is the outcome of a process starting with the Roman-style ‘second wall’ at early Vindonissa and the hybrid gladii at Port-Nidau and Remetschwil. It may have been furthered by members of the Helvetian elite serving in the Roman army (see below, Section VIII). For the Helvetians, the dilemma concerned the appearance and functions of autonomy: in different ways, both the old LTD2 style and the more modern style threatened to reveal the obsolescence of their institutions.

VIII Military institutions and social structure

Perhaps diversity survived, if the old hybrid style of the Remetschwil warrior and the Roman-style guardsmen overlapped. The Lommis gladius, though found in a rural burial, might be explained by (relative) proximity to the urban settlement at Vitudurum. The picture of diversity could be enriched by supposing (without any direct evidence, true) that the epigraphically attested boatmen of the Arar and Lake Lemannus were armed like their Parisian counterparts with shield, spear and bulbous helmet.Footnote 88 Such differences, if they persisted, would have reflected the nature of the Helvetian troops as a ‘national’ army.

The connections between social structure, elite display, antiquarianism and local military means are strikingly illustrated by the finds at a site near Avenches, ‘En Chaplix’ (Figs 7, 10).Footnote 89 At this spot, excavation during highway works revealed a cultic and funerary ensemble from the first century c.e., located on either side of a road leading out of the urban site towards the modern Lake of Morat. A late first-century b.c.e. female burial was covered by an early first-century c.e. cultic zone structured by two temples (of the central cella and peripheral gallery type). Most astonishingly, on the other side of the road, two monumental multi-storied tombs were erected, each in its own enclosure, one in the 20s and one in the 40s c.e. (they are thus contemporary to the Remetschwil burial). The mausoleums, executed in a highly ornate post-hellenistic style, carried at their top aedicula protecting limestone statues in Roman dress and naturalistic style. Among the sculptural fragments figures a vividly executed male head which once wore a metallic crown, perhaps a military decoration comparable to that bestowed on C. Iulius Camillus (Fig. 11). A find from the shrine at Thun-Allmendingen (Bern) offers a parallel: a limestone fragmentary head, originally from an over-lifesize statue, with an attachment hole for a metal wreath, and dating to c. 40 c.e.—another Helvetian elite individual with a Roman military career?Footnote 90

Fig. 10. En-Chaplix mausoleums. From left to right: reconstructed Northern Monument (23–8 c.e.; H. 23.52 m); reconstructed Southern Monument (c. 40–5 c.e.; H. 25.20 m); plan of the area (1. northern temple; 2. southern temple; 3. ‘chapel’; 4. Augustan-era ditch; 5. northern enclosure; 6. southern enclosure; 7. boundary wall of private estate (‘Villa du Russalet’); 8–9. road and ditches; 10–11. Northern Monument and enclosure; 12–13. Southern Monument and enclosure; 14. necropolis). © Site et Musée romains d’Avenches.

Fig. 11. Head from funerary statue, Southern Monument, En-Chaplix. Limestone, H. 345 mm. Inv. 89/7888/15: Bossert Reference Bossert2002: 36. © Site et Musée romains d’Avenches.

Yet the cultural horizons of the En-Chaplix mausoleums were also local and ancient. Three funerary deposits reflect rituals accompanying the erection of the monuments: large-scale cremation on timber structures, the destruction of luxury grave goods of Mediterranean origin (including a dining couch), the sacrifice of a horse, and feasting, as shown by masses of amphora fragments (of Dressel 2-4 type, carefully smashed after use).Footnote 91 The remains of at least eleven amphoras were found at the northern monument, and of at least eight at the southern burial, equalling 330 and 240 litres of wine. The amphora deposits hark back to the aristocratic feasts of the La Tène Iron Age and the ‘Wine Age’.Footnote 92 The archaising practices at En-Chaplix lie on a spectrum with the offerings, at a much more modest scale, in the tombs of Sévaz and Remetschwil.

Finds also establish a connection with the Helvetian militia. Elements from Roman-style belts and thong-aprons, decorative pieces from cavalry harness, and a possible bronze phalera, were found in the area, one in the Augustan-period shrine.Footnote 93 Military parades or musters were perhaps held along the road: the shrine and mausoleums, though associated with a family, may have been the venue for the demonstration of Helvetian military capacity. Elite status and social hierarchies were clearly bound with local autonomy and cultural identity, in a way which we can suspect for the cities of the Greek East but which is harder to substantiate.Footnote 94

Military autonomy perpetuated not just the collective memory of the Helvetians, but also social hierarchies within the community. This is the lesson of the coexistence, within the same social space-time (around 40 c.e.) of the En-Chaplix mausolea and their offerings-rich precincts, the non-elite and austere cemetery of À la Montagne, the Remetschwil weapons-grave and its grave goods and the Roman-influenced militaria of Aventicum, Vitudurum and Thommis. The Helvetian militia symbolised local history and identity, but also worked as a token of social structure, namely the close relationship between autonomy, a large militarisable class, and an elite whose horizons looked to past, present and imperial horizons at the same time.

IX Materiality and martiality in first-century c.e. Gaul

The Helvetian test-case is connected with the question of martiality in the north-western provinces of the Roman empire. L. Pernet has systematically interpreted Roman-influenced weaponry (for instance the hybrid Type-2 gladius), and generally any weaponry at all as an index of military service as auxiliaries to the Roman army.Footnote 95 But the categories need reconsideration.Footnote 96 The story of emergence of auxiliary units in the Roman army is well known. For military aid, the Roman Republic drew extensively on local communities, starting with the Italian communities but also including various polities encountered abroad.Footnote 97 Local communities were especially put to contribution during the late decades of the Republic and their civil wars. Their contingents are the ancestors of the standing auxiliary units (cohorts or alae) recruited locally in the provinces and serving for fixed periods in return for Roman citizenship. This system, a corollary of the Augustan standing army, emerged during the early Julio-Claudian period. The legionary forces at Vindonissa were supported by various auxiliary cohorts, billeted with them but also distributed along the Rhine frontier.Footnote 98 Individuals enrolled in regular auxiliary units, without necessarily coming from the area of original recruitment. Thus, in the first century c.e. two Helvetians served in the Ala I Hispanorum.Footnote 99

Pernet remains careful to take the concept of ‘auxiliaries’ in its broadest sense as any provincial fighting-men serving the Roman empire, especially in the earlier periods and in allied or ad hoc units. Yet even this broad definition obscures the importance of locally recruited troops under the authority of a civitas rather than the Roman army. Mommsen in 1887 already underlined the importance of Provinzialmilizen, as the ‘third military branch’ (dritter Heerteil) alongside legions and auxiliary cohorts. Local associations of young men were often paramilitary in nature, and the cities across the empire needed forces to keep order within their territories.Footnote 100 The Helvetian militia is only one example. The Raetian iuventus constitute another case, all the more striking because Raetia did not enjoy autonomy. The Raetian militia trained alongside Roman forces and fulfilling military duties shows how local military forces operated within the overarching military system of the Roman empire. Other examples include the Batavians and generally the ‘Germans living on this side of the Rhine’ which Germanicus drew upon during his campaign of 15 c.e.Footnote 101 The Pannonian rebels of 6 c.e. are said by Velleius to have had some experience of ‘Roman discipline’ (as well as Latin), surely acquired in similar contexts.Footnote 102 In other words, the old system of allied contingents persisted into the Julio-Claudian period, overlapping with the new system of standing auxiliary units.

Yet the raison d’être of local militias was not limited to service to Rome. In 69 c.e., the uprising of the Boian prophet Mariccus was suppressed by the armed iuventus of the Haedui, a social elite.Footnote 103 Just as Laur-Belart sensed that the Remetschwil tomb was connected to a Helvetian militiaman, T. Fischer, in his survey of militaria in ‘civilian’ context, already raised the possibility that many such finds, usually assigned to the Roman military, equipped local military forces.Footnote 104 Though Feugère and Poux have interpreted militaria in ‘civilian’ contexts in Gaul as showing the continuous presence of Roman military units in inland Gaul down into the first century c.e., I would rather interpret this material, especially in urban context, as relating to local militias.Footnote 105

The material record can be reread within this paradigm. Suggestive cases occur in LTD2b and early Roman Gallia Lugdunensis.Footnote 106 In the free civitas of the Bituriges, defensive and offensive weaponry (including the Type-2 gladius) in funerary context during the early Augustan period need not imply direct auxiliary service under Roman command. One of the Biturigian graves (at Fléré-la-Rivière) is a rich élite burial, dating to 20–1 b.c.e. The gladius was found with two other swords of the late La Tène long type; the grave goods included thirteen amphoras but also paraphernalia for feasting and iron-working. The whole assemblage expresses persistent claims to elite status in a style which emerged in the second century b.c.e.Footnote 107 Among the Bituriges as the Helvetians, military activity tied in with social relations. Militaria among other free civitates, especially in LTD2b and the early Augustan periods, can be related to militias, for instance at the fortified site of Gondole (Puy-de-Dôme), in Arvernian territory,Footnote 108 or Bibracte and Autun, among the Haedui.Footnote 109 The finds include Port-Nidau type helmets.Footnote 110 Such examples take on particular interest when considered alongside funerary representations of men wearing long swords in ‘civilian’ context.Footnote 111 The evolution of the material profile, tending towards Roman equipment (with finds of ‘apron’ pendants), parallels that at Aventicum.

The record of militaria is particularly dense in Gallia Belgica (of particular interest since, as mentioned above, the Helvetian civitas belonged to this province).Footnote 112 Some military funerary material occurs in the western parts of Belgica, away from the Rhine, here too mostly dated to the LTD2 and Augustan periods.Footnote 113 The weapons-tombs of the Augustan era at St-Nicolas (Pas-de-Calais, in the ancient territory of the Atrebates, a stipendiary community) included cingula among their finds of militaria. The great shrine at Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme), in the territory of the Ambiani (also a stipendiary community) yielded weapons from LTD2b and the Augustan period (including a Port-Nidau type helmet). The material parallels the late Iron Age material from Port-Nidau in Switzerland, and could have equipped local military men without them having served as ‘auxiliaries’.Footnote 114

The Helvetian test-case acts as a touchstone for my rereading of the militaria. The late first-century b.c.e. context of the find of the eponymous iron helmet at Port-Nidau (with iron bowl, ‘brows’ and nape protector), at a time of Helvetian political autonomy and military capacities, argues against Feugère’s interpretation of this type of helmet as Roman.Footnote 115 My argument is reinforced by the fragments of Port-Nidau helmet cheek-pieces found at Aventicum and Bern-Enge. The presence of the Port-Nidau type at Bibracte, Gondole or Ribemont-sur-Ancre does not imply the presence of Roman troops or past service as auxiliaries for the Roman army, especially since the first two sites belonged to the free civitates of the Haedui and the Arverni. Furthermore, if my interpretation of the militaria of Aventicum and Vitudurum is correct, even clearly Roman artifacts (such as the ‘apron’ pendants or the gladius) are not necessarily an index of the presence of Roman troops or auxiliary service, as opposed to the adoption by local military forces of certain ‘modern’ pieces of equipment.

A remarkable artifact comes from St Maur (Oise), in the territory of the Bellovaci (yet another stipendiary civitas in Belgica). A statuette of hammered bronze, probably dating to the late first century b.c.e. or the early first century c.e., shows in a distinctive non-Classical style a figure wearing a torc, textile armour and a Roman-style belt with a D-buckle, and holding a shield with the round, ‘Germanic’ umbo, like that known from Remetschwil (Fig. 12).Footnote 116 Jenny Kaurin speculates that the 55 cm tall statuette (whose technique resembles that of earlier boar-ensigns) adorned a military standard. This would imply some form of local army in a LTD2 or early Augustan context (or perhaps an armed procession in honour of an impressively military deity) rather than Roman auxiliary service. The cultural profile recalls the hybridity of the Helvetian finds at Port-Nidau or Remetschwil. The possible context of parades parallels the military musters which I propose for En-Chaplix outside of Avenches.

Fig. 12. Saint-Maur warrior. Copper alloy, H. 55 cm Musée de l’Oise, inv. no. 85.16. Photo Frank Raux. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

Across Gaul, martial culture is mostly visible in the LTD2 and early Roman periods. Subsequently, military identity was no longer commemorated in funerary ritual and offerings.Footnote 117 The free and allied civitas of the Lingones and its stipendiary neighbour the Sequani had military capacities and used them repeatedly during the first century c.e., down to the clashes of 68 and 69–70 c.e.; yet the archaeological record for these two civitates is devoid of militaria or weapons-tombs.Footnote 118 The mysterious massacre of 4,000 Mediomatrici (socia civitas according to Tacitus) in 69 c.e. might have occurred during an accrochage between a local militia and Valens’ column (similar to the debâcle of the Helvetians).Footnote 119 Yet they are absent from Pernet’s archaeological gazetteer of militaria. Remarkably, the Batavians, who served extensively in the Roman army, did not practise burial with weapons.Footnote 120

However, local autonomy could find another means of expression, namely the maintenance of urban fortifications, such as those Suetonius tells us that Galba ordered demolished as a punitive measure.Footnote 121 The phenomenon is noticeable in Gallia Narbonensis where it may be linked to the status of autonomy, but also in northern Gaul. The Lingones and the Mediomatrici likely had fortified urban centres in the early first century c.e. (Andematunnum/Langres for the former, Divodurum/Metz for the latter). At Durocortorum/Reims, the urban centre of the free civitas of the Remi, the Iron Age fortification works were reinforced c. 15–1 b.c.e.; in Hoët-van Cauwenberghe’s words, ‘its Celtic system of defence and display would survive until the reign of Trajan.’ Similarly, older fortifications were maintained by the Carnutes, a free civitas, at Autricum/Chartres in the late Augustan period.Footnote 122

Some stipendiary civitates also maintained walls. Vesontio, the capital of the Sequani, was protected by its Iron Age fortifications at least down to the Tiberian period (perhaps allowing the city to fend off Vindex in 68 c.e.). The stipendiary Ambiani surrounded their urban centre, Samarobriva/Amiens, with fortifications, including an impressive ditch dating to the first half of the first century c.e.Footnote 123 Amiens’ walls came after the earlier (LTD2 and early Augustan) militaria deposed at the shrine of Ribemont-sur-Ancre. Strikingly, even a secondary settlement such as Alisia/Alise Sainte-Reine (Côte-d’Or) maintained and actually extended its fortifications (building in the old murus gallicus style in the early decades of the first century c.e.).Footnote 124 Such practices cannot be related to ‘auxiliary’ service: rather, they offer striking statements of local communal identity.

X Treviri, Helvetians and martiality under the Roman empire

Among the rich record of militaria in eastern Gaul, particularly noticeable is the case of the Treviri.Footnote 125 The material resembles, at a much greater density of finds, the picture on the Swiss Plateau: high popularity at the very end of the first century b.c.e. (LTD2, the same as for the finds at Port-Nidau), persistence in the Augustan period, tailing off in the Julio-Claudian period.Footnote 126 Like the Helvetian finds, Treviran weapons-graves are characterised by a wide diversity.Footnote 127

It is true that Tacitus mentions (in the context of the unrest of 21 c.e.)Footnote 128 a unit of Treviran auxiliary cavalrymen serving locally alongside other such units and trained in Roman style. The great mausoleum of Bartringen/Bertrange (Luxemburg) might be that of a Treviran aristocrat who served in a Roman unit. Its astonishing fragmentary frieze shows Roman (?) cavalry defeating Germans or Celts; a fallen ‘barbarian’ is shown being despoiled of his torc and decapitated.Footnote 129 Nonetheless, according the principles I posit above, there is no a priori reason to call auxiliaries all the occupants of Treviran tombs containing simple spear-and-shield assemblages in, such as the two LTD2b tombs from Mayen (Rheinland-Pfalz). In three of the four elite tombs of Goeblange-Nospelt (Luxemburg), the deceased were buried with swords: one was an early ‘hybrid’ gladius, but two were magnificent La Tène-style swords with decorated scabbards. If the context for one of these Celtic swords dates to LTD2b, the other tomb dates around 15 b.c.e., later than the gladius. The scabbards show bold, innovative lattice-work decoration at the scabbard-top.Footnote 130 Here, too, the category ‘auxiliaries’ is arguably not the right one. Rather, we are dealing with members of local elites with military pretensions, claiming continuity with the past. A similar interpretation might be formulated for the tombs from Lebach (Saarland), where a single gladius appears among seven weapons-graves, or from Koblenz-Neuendorf (Rheinland-Pfalz) where gladii appear in two out of five weapons-graves.

The point of what precedes is not to minimise the impact of the Roman empire. In arguing for militias rather than auxiliaries, I may seem to quibble about mere terminology. In the end, the debate is one of perspective: whereas Pernet takes military service for the Roman empire as his lodestar, I read his gazetteer as a portfolio of snapshots of local martial society. The important point is that the Helvetian muster of 69 c.e. is not some trivial, obscure episode involving ‘tribesmen’ (as Gwyn Morgan regrettably writes).Footnote 131 It is of a piece with the history of Gaul in the transition from LTD2b to Julio-Claudian periods, and of its diverse communities endowed with political identities. These traits explain the unquiet history of northeast and central Gaul for a century after conquest, its violent convulsions until the Flavian period.Footnote 132 Instead of the material traces of Roman empreinte militaire or service within the Roman auxilia, the militaria reveal a political, institutional and cultural koine in the last lights of a long late Iron Age.

XI Political community, material culture and empire

In concluding my paper, I wish to prolong what has proven its central impulse, namely to explore the connections between the findings of a particular ‘national’ archaeology (that of the Swiss Plateau) with ever broadening historical contexts. As an empire-wide phenomenon, the militias of first-century c.e. Gaul find significant parallels in the eastern Mediterranean provinces of the Roman Empire. Many Greek poleis and small principalities of the East were warlike during the Hellenistic age and retained military capacities into the Triumviral period, fighting in their own defence and providing troops (‘auxiliaries’ if you will) to the Roman state. The Galatian ruler Amyntas drew on allied contingents from free cities such as Termessos as auxiliaries against other Pisidian cities such as Sandalion. A Termessian officer was even decorated by the king for bravery, before falling in battle.Footnote 133 The Lykian League kept military institutions until Lykia was reduced to provincial status in 43 c.e. As studied by Cédric Brélaz, even under the Roman Empire, Greek cities kept paramilitary forces to control their territory (and never forgot their glorious military past). Even under Hadrian, the polis of Trapezous supplied forces to fight with the Roman army against the Alani.Footnote 134 In the Roman Near East, as so strikingly shown by Fergus Millar, imperial control during the first century c.e. was surprisingly hesitant and variable, and coexisted with or even depended on local political actors such as client kingdoms; the armies fielded by these kingdoms and free cities play a notable role during the Jewish War.

In the north-western provinces as well as the eastern Mediterranean, the combination of imperial structure and local autonomy results in a noticeable messiness of arrangements on the ground throughout the early Principate, with considerable leeway for unrest and violence.Footnote 135 The Roman senatorial historian Dio Cassius shows awareness of this situation, even as he simplifies it away, in the programmatic speech he assigns to Maecenas: ‘if we allow all our subjects who are of military age to possess arms and undergo a military training, there will be a continual series of riots and civil wars.’Footnote 136

The parallel between West and East suggests that the study of Roman power in the Gallic provinces should not just focus on individuals and their choices, nor just listen to the elites, but also integrate communities endowed with corporate political existence and hence the capacity for fundamental interaction with an imperial state. This viewpoint is standard in the study of the eastern Mediterranean (where written sources make local corporate existence abundantly clear), but needs greater emphasis in the case of the western provinces. It would be merely piquant to draw a parallel between, on the one hand, the virtuoso swordsmiths of Goeblange, the builders patiently maintaining the murus gallicus of Vesontio and Alisia, or the militiamen of Port-Nidau and Remetschwil, and on the other, the performers and thinkers of Hellenic antiquarianism, or other manifestations of the Greeks’ ‘struggle for identity’ under the Roman Empire: the long late Iron Age and the long Hellenistic, both persisting within an empire of domination.Footnote 137 It is more important to keep in focus the political community, be it western civitas or Greek polis, when looking at landscapes of empire. Bringing back (something like) the state when considering the western communities goes beyond the traditional narrative of ‘becoming Roman’.Footnote 138

The importance of the civitas as the crucial level of interpretation has long been promoted for the study of religion in the western provinces, notably by William van Andringa and Thérèse Raepsaet-Charlier, in explicit dialogue with similar approaches in the study of ancient Greek culture (‘polis religion’).Footnote 139 Another example of interpretive work focusing on the importance of local state-like agency and identity is Andrew Johnston’s Sons of Remus, which combines the archaeological evidence dear to historians of western Europe with an awareness of collective identity and institutions, explicitly inspired by work on the Greek East.Footnote 140 It is at this level of the life of communities within empire that concepts such as elites, social complexity, nodal connectivity, region and territory, or imperial landscape come into their own, as ways to view the theatre of power and culture. For instance, according to my interpretation of the first-century c.e. militaria of the Swiss Plateau, ‘Romanisation’ of specific areas of material culture can be seen to happen at the level of the civitas. It results from its institutional and ideological needs, combined with the proximity of the military frontier, the homeostatic pressures of Roman administration, and the impact of elites engaged in the curation of social structure.

XII Exploring the political turn

This is not the place for a social and cultural history of the Helvetian civitas.Footnote 141 Here I would simply insist on the importance of grasping the political and the institutional factors when reading the material record. For instance, the story of urbanisation and settlement is a political one.Footnote 142 At Baden, the shift from the La Tène settlement at Kappelerhof (a cluster of shrines, tombs and enclosures) to the new vicus with its grid plan is not just a story of the erection of a city in modum municipii (in Tacitus’ phrase). An excavated section of the first-century c.e. vicus is characterised by the tight succession of deep, narrow-frontage timber houses: unparalleled in Italian municipal urbanism, this mimics the military architecture of the Rhine frontier (Fig. 13). It matches the situation of the northern fringe of the Helvetian territory as a middle ground of ambiguous encounters with the military frontier.Footnote 143

Fig. 13. Aquae Helveticae/Baden. Base map from Swiss Federal Office of Topography/swisstopo. (1) 1970s rescue excavations, vicus with timber houses, pre-69 c.e. (illustrated by inset plan from Schucany Reference Schucany1984, figure 2); (2) Stone terracing and buildings on slope; (3) Thermal area, hot springs.

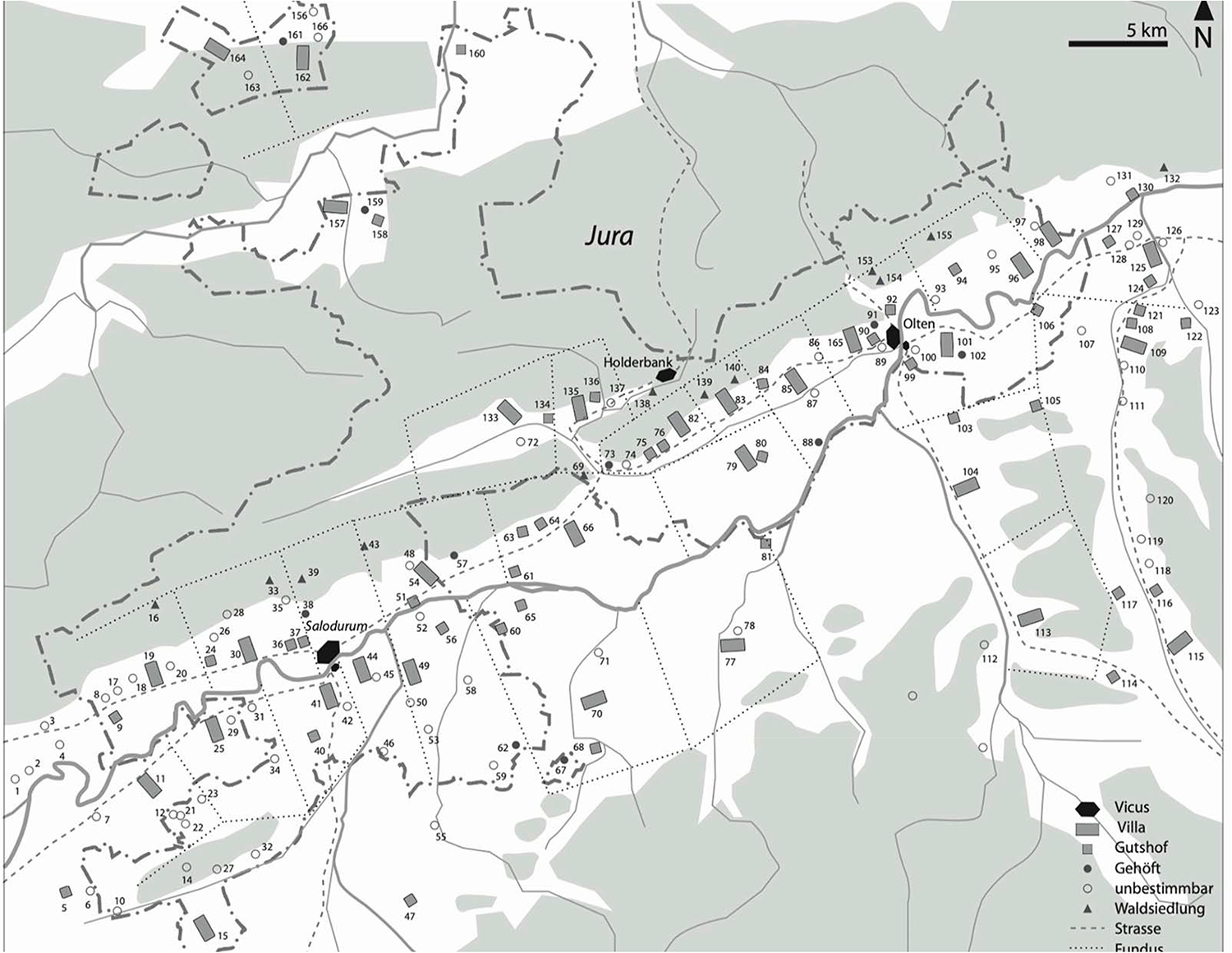

Another phenomenon that can be read politically is the intense settlement of the Helvetian landscape, starting early in the first century c.e. and intensifying in mid-century, namely the development of a regular network of vici, large farms and smaller settlements (Fig. 14). The phenomenon has notably been investigated in Western Switzerland (Aare valley, valley, pre-Alps, Aventicum area).Footnote 144 Schucany relates these changes to the economic demands of the Roman military frontier.Footnote 145 Here too I would also point to the pretensions of the Helvetian civitas: the deep social and economic mutations must have interacted with, and perhaps fuelled, the aspiration for autonomy. The vicus at Vitudurum, which emerges in the eastern part of the Swiss Plateau in the early Augustan period on an orthogonal plan, is part of an urbanising boom driven by endogenous developments within the civitas.Footnote 146 The processes may be connected to the social basis for a ‘middling’ element, which may in turn relate to Helvetian militarism. These examples illustrate the scope of a ‘political turn’ in classical archaeology (if the concept can be proposed non-ironically).

Fig. 14. The middle Aar valley. From Schucany and Wullschleger Reference Schucany, Wullschleger, Richard, Schifferdecker, Mazimann and Bélet-Gonda2013, figure 3, courtesy of C. Schucany.

A final issue is that of evolution across time. At first sight, community agency seems outmatched by the staying power of empire. The first-century c.e. empire fraught with messiness gives way to greater imperial control. The systematisation of empire in the Roman Near East, and the social consequences, constitute a major theme in Millar’s survey of the region.Footnote 147 In the case of the Helvetians, the civitas was refounded by Vespasian as Colonia Pia Flavia Constans Emerita Helvetiorum Foederata. The epithet emerita seems to indicate that the city received a deduction of veterans, and epigraphical material indicates a double civic structure of coloni and incolae. Footnote 148 The foundation might reflect punitive intentions after the uprising of 69 c.e. Yet the title foederata, illogical for a colony, connects with the long past of the Helvetian civitas. This past is also evoked in the fortification of the city on a massive scaleFootnote 149 (Fig. 7) and lives on in the militaria of Avenches and Vitudurum occurring in second-century c.e. contexts.Footnote 150 Political community continued to work as the framework for communal identity and social structures; that was the point of it.

Abbreviations

- CHRE

Coin Hoards of the Roman Empire, https://chre.ashmus.ox.ac.uk

- OMS

L. Robert, Opera Minora Selecta, 7 vols, Amsterdam, 1969–90.

- RIIG

Recueil Informatisé des Inscriptions de la Gaule, https://riig.huma-num.fr

- TitHelv

A. Kolb, Tituli Helvetici. Die römischen Inschriften der West- und Ostschweiz, Bonn, 2022.

Appendix 1: Some finds of militaria from the Swiss Plateau

a. First century c.e.

Turicum

Balmer Reference Balmer2009, cat. 765, 822 (harness pieces), 874 (sword furniture), 871 (D-ring belt buckle), 872 (rivet from cingulum). All c. 30–60 c.e.

Oberwinterthur

Rychener and Albertin Reference Rychener and Albertin1986: 84 (lone phallus-shaped pendant from southern part of vicus, late Augustan); Deschler-Erb Reference Deschler-Erb, Deschler-Erb and Pult1996: 78–104, 169–70 (stratigraphically dated first-century c.e. finds, from Unteres Bühl in western part of the vicus, to wit: cat. ME 300–301, gladius furniture; 304, helmet piece; 305, hamata hook; 313-14, ‘segmentata’ hinges, dated 40–60 c.e.; 313–31, 336–9, 342–5, 350, 353–7, 359–60, 365, 367, harness decorations; E 331-6, 340–7, points); Hedinger et al. Reference Hedinger, Janke and Jauch2001: 230–2 (stratigraphically dated finds from the north-east quarter, to wit: cat. ME 22, Claudian-era javelin point; 33, Augustan-era bridle fragment; 25, piece of military belt dated 50-100 c.e.; 26, 30–1, pieces of harness decorations, ‘Neronian-Flavian’); Jauch and Janke Reference Jauch and Janke2022: 201–3 (militaria from north quarter, of which half date to the first century c.e. down to c. 60 c.e.). Generally, Reddé Reference Reddé2009: 177.

Avenches

Voirol Reference Voirol2000, cat. 21, 24 (spears), 42, 43, 45 (swords), 47–8 (segmented armour), 65, 66, 67, 68, 70 (belt elements), 72, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80 (elements from military apron), 259 (phalera), 84, 89, 90, 92–9, 101, 103, 105–10, 117 (harness decorations), 231, 243, 247 (12 separate rivets/buttons).

b. Later militaria

Avenches

Voirol Reference Voirol2000, cat. 16, 23, 44, and many pieces of horse harness among the finds nos. 100–246.

Vitudurum

Deschler-Erb Reference Deschler-Erb, Deschler-Erb and Pult1996, e.g. for militaria in second-century c.e. contexts cat. ME 306–10, 315 (segmented armour), 337–8 (iron points); Hedinger et al. Reference Hedinger, Janke and Jauch2001, cat. ME 24 for ‘segmentata’ hinge dated 80–100 c.e.; Jauch and Janke Reference Jauch and Janke2022: 201–3.

Appendix 2: LTD2 and early Roman militaria from Gaul, possibly relating to militias in the early Imperial period

a. Gallia Lugdunensis

Cemetery of the ‘Vaugrignon’, at Esvres-sur-lndre (Indre-et-Loire): Riquier Reference Riquier2004, with Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C10 and generally Marton Reference Marton2021 (Turones).

Malintrat-Chaniat (Puy-de-Dôme), weapons-grave dating to 50–25 b.c.e. and found inside a precinct with traces of burnt offerings: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C17 (Arverni).

Feurs (Loire) two weapons-tombs, of LTD2 and early Augustan date: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C11 (Segusiavi).

Ménestreau-en-Villette (Loiret), early Augustan-period weapons-grave: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C19 (Carnutes).

Berry-Bouy ‘Fontillet’ (Cher), early Augustan weapons-graves: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C3 (Bituriges).

Fléré-la-Rivière (Indre), early Augustan elite burial: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C12 (Bituriges).

Chassenard (Allier), rich Tiberian-era tomb: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C5 (Haedui).

Gondole (Puy-de-Dôme), LTD2b militaria in urban context: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C14 (Haedui).

Bibracte (Saône-et-Loire), militaria in urban context: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: C21 (Haedui).

Autun (Saône-et-Loire), militaria in urban content: Fort and Labaune Reference Fort and Labaune2008 (Haedui).

b. Gallia Belgica generally

Notre-Dame-de-Vaudreuil (Eure), LTD2 tomb with sword and western Celtic helmet: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B29 (Veliocassi).

Cottévrard (Seine-Maritime), LTD2a tomb with sword: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B8 (Caletes).

Saint Aubin-Routot (Seine-Maritime), LTD2a necropolis with one weapons-grave: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B37 (Caletes).

Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme), militaria in sacred context (offerings at shrine): Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B34 (Ambiani).

St Nicolas (Pas-de-Calais), Augustan-era tombs with Roman-style militaria: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B38 (Atrebates).

Ronchin (Nord), gladius in Augustan-era grave: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B35 (Menapii).

Ville-sur-Retourne (Ardennes), LTD2 (but possibly pre-conquest) 40 tombs, 4 with weapons: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B45 (Remi).

c. Treviri

Goeblingen-Nospelt (Cappellen, Luxemburg), 4 elite tombs (LTD2b to Augustan): Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B11.

Mayen (Rheinland-Pfalz), two LTD2b weapons-tombs: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B25.

Koblenz-Neuendorf (Rheinland-Pfalz), 5 Augustan-era weapons-tombs: Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B17.

Lebach (Saarland), 8 weapons-graves (2 from LT2Db, 6 from Augustan and Julio-Claudian periods): Pernet Reference Pernet2010: B21.

Appendix 3: Numismatic evidence discussed in this paper

a. Early first-century b.c.e. finds of silver coins on the Swiss Plateau

Cossonay (Vaud), 59 quinarii: Geiser Reference Geiser2015 (possible votive deposit, c. 100 b.c.e.?)

Mont-Vully (Fribourg), 14 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.1042–8 (FR1/9).

La Tène (Neuchâtel): Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1218–25, awaiting separate publication.

Bern-Enge (Bern), 7 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.945, 946, 950, 952, 956, 957–8, 985 (BE-4).

Roggwil (Bern), 145 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2022.

Niederbipp (Bern), c. 60 b.c.e., 7 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.1007–10 (BE-20, 21).

Eppenberg-Wöschnau (Solothurn), c. 90–60 b.c.e., 4 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1272–3 (SO-6).

Stray finds of individual quinarii from the Swiss Plateau within canton Solothurn: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1274–6 (SO-7, 8, 9); Benken (Zurich): Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1565 (ZH-1).

Rheinau (Zurich), 131 quinarii, 8 ¼ quinarii: Frey-Kupper and Nick Reference Frey-Kupper and Nick2009: 73–6; Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1583–1621 (ZH-19 to 23).

b. Early first century b.c.e. coin finds from the territory of the Rauraci

Balsthal, 150-60 coins, c. 60–40 b.c.e.: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1263–7, SO-1.

Füllinsdorf, 335 silver coins, 90–80 b.c.e.: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.620; Nick Reference Nick and Ackerman2024.

Basel-Gasfabrik, 2 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.699 (BS-1/25).

Basel-Münsterhügel, 9 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.820-2, 845-8 (BS-2/9 and 18).

Nunningen (Solothurn), at least 50 coins c. 90–70 b.c.e.: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1278–89 (SO-11); Nick Reference Nick2017a: 49–50.

Basel canton, 9 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.623, 624, 643–5 (BS-7, 8, 23/1).

Courroux (Jura) ? 9 quinarii, one denarius: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1189–94 (JU-7). Possibly to be dated to the second half of the first century b.c.e.

c. Late first-century b.c.e. and early first-century c.e. silver coin finds from the Swiss Plateau

Sermuz (Vaud), 57 quinarii: Geiser Reference Geiser2007; Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1455–66 (VD-57); Geiser Reference Geiser2017.

Avenches (Vaud), 23 quinarii across the site: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1344–68 (VD-1 to 11).

Bois-de-Châtel (Vaud), 11 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1369–72 (VD-12).

Belpberg (Bern), 54 quinarii, 38 denarii, hoard buried between 42 b.c.e. and 32 b.c.e.: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.927–39 (BE-2); Nick Reference Nick and Ackerman2024, interpreting the hoard as military.

Bern-Enge (Bern), 64 silver coins, made up for 2/3 of quinarii and 1/3 of denarii struck under Augustus (located by detectorists in 2022): CHRE 21274; Lanzicher and Puthod Reference Lanzicher and Puthod2023.

Studen/Petinesca (Bern), 3 quinarii: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.1015–16 (BE-25).

Deitingen (Solothurn), 4 quinarii and 2 denarii struck between 47/6 and 42 b.c.e.: Nick Reference Nick2015: 3.1270–1 (SO-5); Nick Reference Nick2017a: 51.

Windisch (Aargau), 36 quinarii, of which 8 come from the area inside the trace of the LTD2 wall: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.505–52 (AG-26); Nick in Flück Reference Flück2022a: 333–4. In addition, 9 quinarii washed down from the Windisch plateau down to Brugg: Nick Reference Nick2015: 2.487–91 (AG-14).

d. Deposits of single aurei dating before 69 c.e. on the Swiss plateau (from west to east)

CHRE 12217 Murist (Fribourg), 12218 Granges-de-Vesin (Fribourg), 12174 Avenches, 6403 Villarepos (Fribourg), 12524 Bern, 12211 Burgistein (Bern), 12232 Opplingen (Bern), 12208 Bern-Enge, 12190 Meikirch (Bern), 12522 Niederosch (Bern), 12209 Biel, 9322 Bibern (Solothurn), 9334-5 Solothurn, 6614 Zuchwil (Solothurn), 6416 ibid., 12237 Roggwil (Bern, with Nick Reference Nick2022: 214–15), 6418 Suhr (Aargau), 6419 Gränichen (Aargau), 6617 Aarau, 6619 Remigen (Aargau), 6620 Bad Zurzach (Aargau), 6409 Umiken (Aargau), 1220 Herliberg (Zurich), 12529 Meilen (Zurich), 12235 Rickenbach (Zurich).