1. Introduction

The transition to a carbon-free energy system will heavily rely on chemical energy carriers like green hydrogen (

![]() $\textrm {H}_{2}$

) to meet the requirements for energy transport and long-term storage (Dreizler et al. Reference Dreizler, Pitsch, Scherer, Schulz and Janicka2021). From an engineering perspective, fuel-lean premixed hydrogen combustion is especially relevant, primarily as it limits thermal

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

) to meet the requirements for energy transport and long-term storage (Dreizler et al. Reference Dreizler, Pitsch, Scherer, Schulz and Janicka2021). From an engineering perspective, fuel-lean premixed hydrogen combustion is especially relevant, primarily as it limits thermal

![]() $\textrm {NO}_{x}$

formation (Verhelst & Wallner Reference Verhelst and Wallner2009; Pitsch Reference Pitsch2024). However, lean hydrogen flames are known to be susceptible to intrinsic flame instabilities under operating conditions typical of practical combustion systems, including gas turbines at elevated pressures and temperatures, and domestic heaters at low temperatures and ambient pressure (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Attili and Pitsch2022a

,

Reference Berger, Attili and Pitschb

; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a

,

Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasseb

).

$\textrm {NO}_{x}$

formation (Verhelst & Wallner Reference Verhelst and Wallner2009; Pitsch Reference Pitsch2024). However, lean hydrogen flames are known to be susceptible to intrinsic flame instabilities under operating conditions typical of practical combustion systems, including gas turbines at elevated pressures and temperatures, and domestic heaters at low temperatures and ambient pressure (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Attili and Pitsch2022a

,

Reference Berger, Attili and Pitschb

; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a

,

Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasseb

).

Intrinsic flame instabilities comprise hydrodynamic (Darrieus–Landau, DL) instabilities, caused by the density jump across the flame front, and thermodiffusive (TD) instabilities, stemming from the disparity between heat and mass diffusivity, amplified by hydrogen’s high molecular diffusivity (Matalon Reference Matalon2007; Creta et al. Reference Creta, Lapenna, Lamioni, Fogla and Matalon2020). TD instabilities promote local mixture enrichment and burning-rate fluctuations. Furthermore, although TD instabilities are localised effects, they lead to significant acceleration of the global flame speed (Altantzis et al. Reference Altantzis, Frouzakis, Tomboulides, Matalon and Boulouchos2012; Berger et al. Reference Berger, Kleinheinz, Attili and Pitsch2019; Howarth, Hunt & Aspden Reference Howarth, Hunt and Aspden2023), thereby posing challenges to maintain stable flame operation.

Additionally, technical combustion systems are typically confined by walls, leading to flame–wall interactions (FWIs). These interactions potentially increase pollutant formation due to flame quenching and incomplete combustion, while also inducing wall heat fluxes that may lead to material degradation (Dreizler & Böhm Reference Dreizler and Böhm2015). FWIs have been studied mostly in hydrocarbon flames (e.g. Bioche, Vervisch & Ribert Reference Bioche, Vervisch and Ribert2018; Steinhausen et al. Reference Steinhausen2020, Reference Steinhausen, Zirwes, Ferraro, Scholtissek, Bockhorn and Hasse2023) and partially also in hydrogen flames under fuel-rich operating conditions (e.g. Gruber et al. Reference Gruber, Sankaran, Hawkes and Chen2010, Reference Gruber, Chen, Valiev and Law2012; see Dreizler & Böhm (Reference Dreizler and Böhm2015) for a detailed overview). Furthermore, other studies have examined the influence of non-unity Lewis numbers on the quenching process in turbulent HOQ flames (e.g. Lai & Chakraborty Reference Lai and Chakraborty2015; Lai et al. Reference Lai, Ahmed, Klein and Chakraborty2022). Addressing an aspect not covered in previous studies, Schneider et al. (Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a , Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasseb ) have demonstrated for the first time that TD instabilities fundamentally alter the quenching behaviour of multidimensional lean premixed (laminar) hydrogen flames, leading to significantly higher wall heat fluxes and markedly shorter quenching distances than a one-dimensional (1D) reference flame under identical conditions.

Toward more application-relevant configurations, simulations that resolve detailed chemical kinetics and transport become increasingly complex and may become prohibitively expensive or even practically infeasible (Fiorina, Veynante & Candel Reference Fiorina, Veynante and Candel2014). This motivates the use of reduced-order models, among which tabulated chemistry (TC) methods offer particularly high computational efficiency (Fiorina et al. Reference Fiorina, Veynante and Candel2014; van Oijen et al. Reference van Oijen, Donini, Bastiaans, ten Thije Boonkkamp and de Goey2016). These methods rely on the assumption that the thermochemical state of the flame resides on a lower-dimensional manifold, typically derived from 1D laminar flame simulations and parametrised by a set of reduced control variables

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_i$

. This allows for only solving the transport equations for

$\mathcal{Y}_i$

. This allows for only solving the transport equations for

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_i$

at runtime and retrieving the corresponding thermochemical state directly from the manifold. Various tabulation strategies, such as flame prolongation of intrinsic low-dimensional manifold method (Gicquel, Darabiha & Thévenin Reference Gicquel, Darabiha and Thévenin2000), the flamelet–progress variable (FPV) method (Pierce & Moin Reference Pierce and Moin2004) and flamelet-generated manifolds (FGM) (Oijen & Goey Reference Oijen van and Goey de2000; van Oijen et al. Reference van Oijen, Donini, Bastiaans, ten Thije Boonkkamp and de Goey2016), have been successfully developed for hydrocarbon fuels and shown to yield accurate results even in complex configurations.

$\mathcal{Y}_i$

at runtime and retrieving the corresponding thermochemical state directly from the manifold. Various tabulation strategies, such as flame prolongation of intrinsic low-dimensional manifold method (Gicquel, Darabiha & Thévenin Reference Gicquel, Darabiha and Thévenin2000), the flamelet–progress variable (FPV) method (Pierce & Moin Reference Pierce and Moin2004) and flamelet-generated manifolds (FGM) (Oijen & Goey Reference Oijen van and Goey de2000; van Oijen et al. Reference van Oijen, Donini, Bastiaans, ten Thije Boonkkamp and de Goey2016), have been successfully developed for hydrocarbon fuels and shown to yield accurate results even in complex configurations.

In recent years, extensions of TC approaches to FWIs have been intensively investigated in laminar and turbulent side-wall quenching (SWQ) configurations to improve pollutant predictions in hydrocarbon flames (Ganter et al. Reference Ganter, Heinrich, Meier, Kuenne, Jainski, Rißmann, Dreizler and Janicka2017, Reference Ganter, Straßacker, Kuenne, Meier, Heinrich, Maas and Janicka2018; Efimov, de Goey & van Oijen Reference Efimov, de Goey and van Oijen2019; Steinhausen et al. Reference Steinhausen2020, Reference Steinhausen, Zirwes, Ferraro, Scholtissek, Bockhorn and Hasse2023). These studies demonstrated that manifolds based on head-on quenching (HOQ) flamelets offer superior accuracy, particularly regarding CO formation, compared with those based on freely propagating (FP) flames with varying levels of enthalpy, as usually employed to capture heat losses in lifted flames (Ketelheun, Kuenne & Janicka Reference Ketelheun, Kuenne and Janicka2013). However, these studies focus exclusively on hydrocarbon fuels, where differential and preferential diffusion effects are typically assumed to be negligible. As a result, the unity Lewis number assumption is commonly applied in both manifold generation and the transport equations with minimal impact on the model accuracy (Ganter et al. Reference Ganter, Heinrich, Meier, Kuenne, Jainski, Rißmann, Dreizler and Janicka2017). Note that in the following, the term differential diffusion comprises both differential diffusion through the disparity of heat and species diffusion (i.e. non-unity Lewis numbers) and preferential diffusion between individual species (i.e. non-equal Lewis numbers).

In contrast, assuming a unity Lewis number in hydrogen combustion artificially suppresses differential diffusion effects and thereby predicts incorrect flame properties, such as flame speeds and flame thicknesses, and, most critically, fails to capture TD instabilities. To overcome this limitation, in recent years, a number of studies (de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Regele et al. Reference Regele, Knudsen, Pitsch and Blanquart2013; Abtahizadeh, de Goey & van Oijen Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015; Donini et al. Reference Donini, Bastiaans, van Oijen and de Goey2015; Schlup & Blanquart Reference Schlup and Blanquart2019; Mukundakumar et al. Reference Mukundakumar, Efimov, Beishuizen and van Oijen2021; Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Chen, Xie, Scholtissek, Chen and Hasse2022; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022; Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Lulic, Steinhausen, Wen, Hasse and Scholtissek2023, Reference Böttler, Kaddar, Karpowski, Federica, Scholtissek, Nicolai and Hasse2024; Fortes et al. Reference Fortes, Pérez-Sánchez, Both, Grenga and Mira2025; Pérez-Sánchez et al. Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025; Schepers & van Oijen Reference Schepers and van Oijen2025) have extended TC approaches to capture differential diffusion effects in premixed hydrogen flames. While some studies focus on TD instabilities and others on heat losses, none simultaneously address both effects with explicit consideration of FWIs, a critical gap given their coupled impact in practical combustion systems.

Accordingly, to provide reliable reduced-order simulations of near-wall TD instabilities, the objectives of this work are as follows:

-

(i) To develop an accurate TC model for the FWI of TD unstable

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

/air flames, advancing a recently proposed flamelet tabulation framework by Abtahizadeh et al. (Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015), Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022); Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025).

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

/air flames, advancing a recently proposed flamelet tabulation framework by Abtahizadeh et al. (Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015), Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022); Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025). -

(ii) To derive a universal approach for accurately and efficiently determining the additional terms in the transport equations resulting from differential diffusion.

-

(iii) To incorporate thermal (Soret) diffusion into the flamelet tabulation framework, acknowledging its significant role in lean hydrogen combustion, including the near-wall regions (Schlup & Blanquart Reference Schlup and Blanquart2017, Reference Schlup and Blanquart2018; Zirwes et al. Reference Zirwes, Zhang, Kaiser, Oberleithner, Stein, Bockhorn and Kronenburg2024).

-

(iv) To examine two different flamelet databases: one derived from 1D FP flames with enthalpy variation, and another based on 1D HOQ flamelets, which have demonstrated superior accuracy for hydrocarbon flames.

-

(v) To validate the framework and the manifolds in both an a-priori and a-posteriori manner against reference detailed chemistry (DC) simulations.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows: § 2 presents the flamelet tabulation approach, highlighting the novel extensions introduced in this work beyond the base model, with a particular focus on the formulation and computation of additional terms capturing differential diffusion effects. Section 3 outlines the numerical methods used, while § 4 introduces the different manifolds employed in this study, targeting either TD instabilities or heat losses. Furthermore, a combination of these manifolds into joint manifolds is developed to simultaneously capture both effects. Subsequently, § 5 evaluates the manifolds across a sequence of increasingly complex configurations: 1D FP flames for model verification; 1D HOQ flames to assess the model’s capabilities to capture heat losses; two-dimensional (2D) TD unstable flames to assess the model’s capabilities to capture TD instabilities and, finally, 2D HOQ of a thermodiffusively unstable flame, which demands that the manifolds simultaneously capture both instabilities and heat losses. In this context, both a-priori analyses and a-posteriori evaluations based on fully coupled TC simulations are conducted and compared against DC reference simulations. The paper concludes with a summary and outlook in § 6.

2. Differential diffusion in TC models: background and model extensions

Various TC modelling approaches from the literature are first briefly summarised to demonstrate the foundation of the proposed model and to contextualise its differences from other model formulations. Subsequently, the TC model employed in this study is derived in detail and the manifold construction is outlined.

2.1. Model background and classification

To incorporate differential diffusion, various approaches have been proposed in the literature (Oijen & Goey Reference Oijen van and Goey de2000; Vreman et al. Reference Vreman, van Oijen, de Goey and Bastiaans2009; de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Regele et al. Reference Regele, Knudsen, Pitsch and Blanquart2013; Abtahizadeh et al. Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015; Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Scholtissek, Chen, Chen and Hasse2021; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022; Pérez-Sánchez et al. Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025). All these models within the TC framework have in common that they are constructed from precomputed flamelets (see van Oijen et al. Reference van Oijen, Donini, Bastiaans, ten Thije Boonkkamp and de Goey2016 for details) and employ a reaction progress variable

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

as one of the controlling variables of the manifolds, typically defined as a linear combination of species mass fractions:

$Y_{{c}}$

as one of the controlling variables of the manifolds, typically defined as a linear combination of species mass fractions:

\begin{equation} Y_{{c}} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k Y_k . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Y_{{c}} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k Y_k . \end{equation}

Here

![]() $a_k$

is the weighting factor associated with the mass fraction

$a_k$

is the weighting factor associated with the mass fraction

![]() $Y_k$

of species

$Y_k$

of species

![]() $k$

. The transport equation for the progress variable can be derived from the species transport equation. The general form of the transport equation for a species mass fraction

$k$

. The transport equation for the progress variable can be derived from the species transport equation. The general form of the transport equation for a species mass fraction

![]() $Y_k$

is given by

$Y_k$

is given by

where

![]() $u_i$

is the velocity in direction

$u_i$

is the velocity in direction

![]() $i$

,

$i$

,

![]() $V_{k,i}$

is the diffusion velocity of species

$V_{k,i}$

is the diffusion velocity of species

![]() $k$

in direction

$k$

in direction

![]() $i$

,

$i$

,

![]() $\rho$

is the density and

$\rho$

is the density and

![]() $\dot {\omega }_k$

is the reaction source term of species

$\dot {\omega }_k$

is the reaction source term of species

![]() $k$

. An equation for the progress variable

$k$

. An equation for the progress variable

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

follows by summing the species transport equations, weighted by

$Y_{{c}}$

follows by summing the species transport equations, weighted by

![]() $a_k$

:

$a_k$

:

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho Y_{{c}}}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i Y_{{c}}}{\partial x_i} = -\frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left ( \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k Y_k V_{k,i} \right ) + \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k \dot {\omega }_k. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho Y_{{c}}}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i Y_{{c}}}{\partial x_i} = -\frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left ( \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k Y_k V_{k,i} \right ) + \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k \dot {\omega }_k. \end{equation}

Notably, the diffusion term involves a summation over the diffusion fluxes of all species contributing to the progress variable, which necessitates an appropriate closure. In contrast, assuming a unity Lewis number implies identical diffusion coefficients for all species, which can be factored out of the summation, thereby enabling an analytical closure of the term.

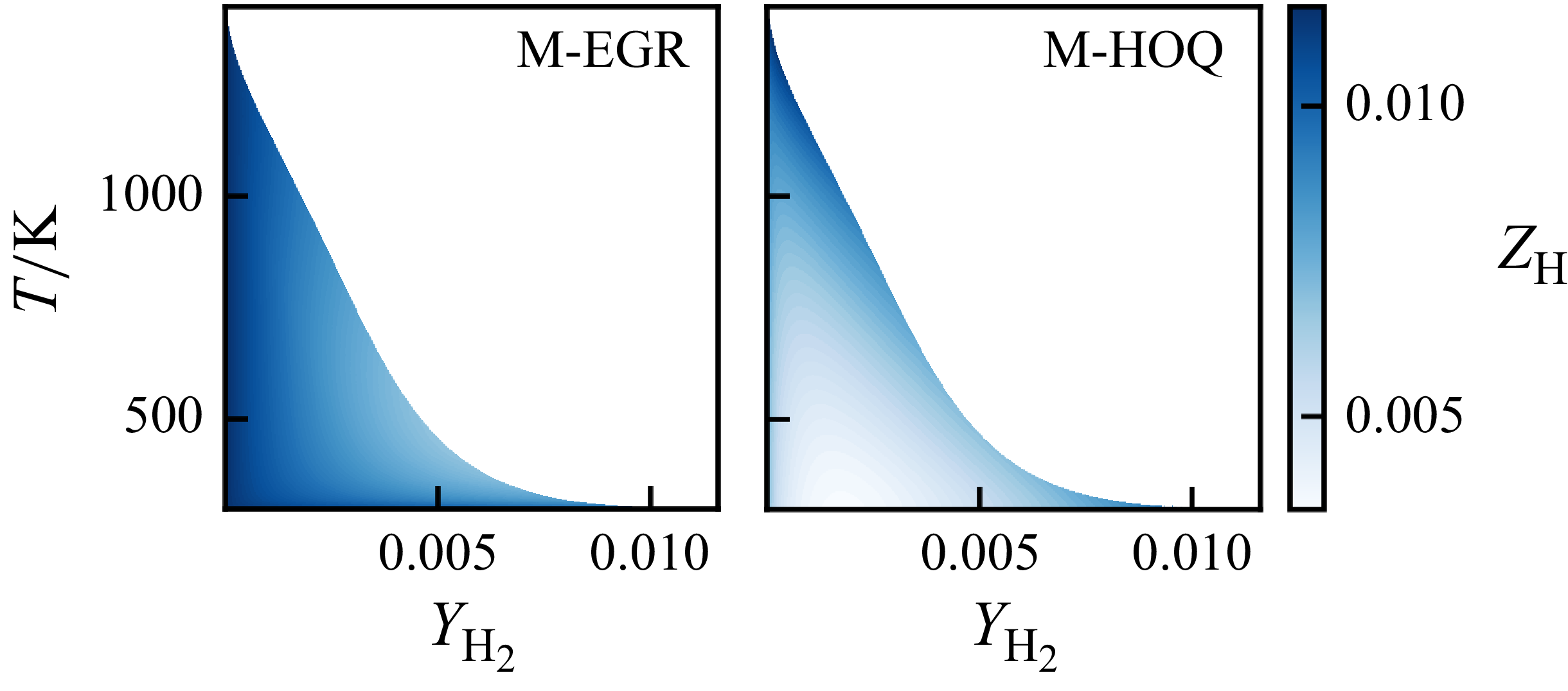

When differential diffusion becomes important, the multidimensional flame structure can deviate from a 1D profile due to flame front curvature, and might therefore vary locally. Thus, even in a purely premixed flame, multidimensional diffusion effects emerge, with transport occurring not only normal to the flame front but also tangential to it. As a result, the thermochemical state cannot be represented by a single controlling variable (de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Regele et al. Reference Regele, Knudsen, Pitsch and Blanquart2013). Thus, theoretically, to take differential diffusion into account in a three-element system (H, O, N), in addition to the reaction progress variable

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

, two elemental mass fractions, e.g.

$Y_{{c}}$

, two elemental mass fractions, e.g.

![]() $Z_{\textrm {H}}$

and

$Z_{\textrm {H}}$

and

![]() $Z_{\textrm {O}}$

(since the missing elemental mass fraction is determined from the element mass fraction unity constraint), are required to capture the local elemental composition and chemical equilibrium (de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022). In this context, elemental mass fractions (and mixture fractions in general) offer the key advantage for TC approaches that they are conserved during chemical reactions and, consequently, their transport equations contain no chemical source terms.

$Z_{\textrm {O}}$

(since the missing elemental mass fraction is determined from the element mass fraction unity constraint), are required to capture the local elemental composition and chemical equilibrium (de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022). In this context, elemental mass fractions (and mixture fractions in general) offer the key advantage for TC approaches that they are conserved during chemical reactions and, consequently, their transport equations contain no chemical source terms.

The elemental mass fraction of an element

![]() $e$

is defined as

$e$

is defined as

\begin{equation} Z_{e} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \gamma _{e,k} \frac {W_e}{W_k} Y_k, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Z_{e} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \gamma _{e,k} \frac {W_e}{W_k} Y_k, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\gamma _{e,k}$

is the number of atoms of element

$\gamma _{e,k}$

is the number of atoms of element

![]() $e$

in species

$e$

in species

![]() $k$

, and

$k$

, and

![]() $W_e$

and

$W_e$

and

![]() $W_k$

are the molar masses of element

$W_k$

are the molar masses of element

![]() $e$

and species

$e$

and species

![]() $k$

, respectively. Summing the species transport equations according to (2.4), the elemental mass fraction transport equation is obtained:

$k$

, respectively. Summing the species transport equations according to (2.4), the elemental mass fraction transport equation is obtained:

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho Z_e}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i Z_e}{\partial x_i} = -\frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left ( \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \gamma _{e,k} \frac {W_e}{W_k} Y_k V_{k,i} \right )\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho Z_e}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i Z_e}{\partial x_i} = -\frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left ( \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \gamma _{e,k} \frac {W_e}{W_k} Y_k V_{k,i} \right )\!. \end{equation}

Note that the same considerations also apply to other definitions of mixture fractions, for example,

![]() $Z_{\textit{Bilger}}$

, which is defined as a normalised linear combination of elemental mass fractions, allowing a corresponding transport equation to be derived, as detailed by Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025). The diffusion term in the transport equation(s) of the elemental mass fractions(s) (or mixture fraction(s)) also requires closure, as it involves the summation of the diffusive fluxes of multiple species. To simplify this, many studies adopt a reduced mixture fraction, though its definition often varies. Furthermore, to limit the number of controlling variables, which is computationally unfavourable, the dimensionality is often reduced by assuming a relation between the elemental mass fractions (and enthalpy) (de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Kuenne, Knappstein, Schneider, Becker, Hasse, Mare, di Dreizler and Janicka2020).

$Z_{\textit{Bilger}}$

, which is defined as a normalised linear combination of elemental mass fractions, allowing a corresponding transport equation to be derived, as detailed by Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025). The diffusion term in the transport equation(s) of the elemental mass fractions(s) (or mixture fraction(s)) also requires closure, as it involves the summation of the diffusive fluxes of multiple species. To simplify this, many studies adopt a reduced mixture fraction, though its definition often varies. Furthermore, to limit the number of controlling variables, which is computationally unfavourable, the dimensionality is often reduced by assuming a relation between the elemental mass fractions (and enthalpy) (de Swart et al. Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Kuenne, Knappstein, Schneider, Becker, Hasse, Mare, di Dreizler and Janicka2020).

In summary, existing models differ notably in how they treat diffusion, leading to variations not only in the definition of the mixture fraction but, in some cases, also in the flamelet database. These distinctions are examined in more detail through a review of the respective modelling strategies found in the literature.

2.1.1. Simplified mixture fraction models

Initial efforts to capture differential diffusion effects were conducted by Vreman et al. (Reference Vreman, van Oijen, de Goey and Bastiaans2009), who computed an effective Lewis number for each controlling variable. Their approach accounted for differential diffusion between heat and fuel but did not capture preferential diffusion between individual species. Moreover, the results were found to be sensitive to the choice of controlling variables.

Another approach to capture differential and preferential diffusion was proposed by Regele et al. (Reference Regele, Knudsen, Pitsch and Blanquart2013), who extended the FPV model to incorporate constant, non-unity Lewis numbers. They employed a reduced mixture fraction that considers only fuel and oxidiser, and assumed one-step chemistry for the derivation of its transport equation. This offers the advantage of a simplified closure of the diffusion terms, however, only the diffusion effects of the major species are taken into account. Note that the mixture fraction transport equation includes a cross-diffusion term that accounts for diffusion induced by the gradient of the progress variable. However, no corresponding cross-diffusion term is included in the progress variable transport equation. The authors employed a flamelet database consisting of 1D FP flames with varying equivalence ratios. Schlup & Blanquart (Reference Schlup and Blanquart2019) extended the work by Regele et al. (Reference Regele, Knudsen, Pitsch and Blanquart2013) and relaxed the constant Lewis number assumption to include mixture-averaged transport and thermal (Soret) diffusion. The model was tested on a spherically expanding flame and a TD unstable FP flame, both showing good results. A three-dimensional (3D) simulation of a turbulent premixed lean hydrogen/air flame showed good agreement in regions without superadiabatic temperatures, but deviations were observed in superadiabatic regions. Yao & Blanquart (Reference Yao and Blanquart2024) applied this model in the framework of the large eddy simulations (LES) of a low-swirl burner with a lean premixed hydrogen/air mixture using a presumed probability density function (PDF) approach for turbulence-chemistry interaction (TCI), while Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Attili, Gauding and Pitsch2025) also applied the model in the LES of a lean hydrogen/air slot flame also using a presumed PDF approach for TCI.

Böttler et al. (Reference Böttler, Chen, Xie, Scholtissek, Chen and Hasse2022, Reference Böttler, Lulic, Steinhausen, Wen, Hasse and Scholtissek2023) adopted an approach conceptually similar to that of Regele et al. (Reference Regele, Knudsen, Pitsch and Blanquart2013) and Schlup & Blanquart (Reference Schlup and Blanquart2019), employing a reduced mixture fraction based on the major species (

![]() $\textrm {H}_{2}$

,

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

,

![]() $\textrm {O}_{2}$

and

$\textrm {O}_{2}$

and

![]() ${\textrm {H}_{2}}\textrm {O}$

). However, instead of directly transporting this reduced mixture fraction, they solved transport equations for the major species and reconstructed both the reduced mixture fraction and the progress variable from those species prior to the table lookup. In the transport equations of the major species, the diffusion coefficients of the transported species are well defined and can be tabulated directly. The correction velocity and thermal diffusion are neglected in the transport equations, as their closure is not straightforward within this framework. As the model was originally developed for forced ignition in hydrogen/air mixtures (Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Chen, Xie, Scholtissek, Chen and Hasse2022), a transport equation for the enthalpy

${\textrm {H}_{2}}\textrm {O}$

). However, instead of directly transporting this reduced mixture fraction, they solved transport equations for the major species and reconstructed both the reduced mixture fraction and the progress variable from those species prior to the table lookup. In the transport equations of the major species, the diffusion coefficients of the transported species are well defined and can be tabulated directly. The correction velocity and thermal diffusion are neglected in the transport equations, as their closure is not straightforward within this framework. As the model was originally developed for forced ignition in hydrogen/air mixtures (Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Chen, Xie, Scholtissek, Chen and Hasse2022), a transport equation for the enthalpy

![]() $h$

was included, resulting in a 3D manifold with

$h$

was included, resulting in a 3D manifold with

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

,

$Y_{{c}}$

,

![]() $Z$

and

$Z$

and

![]() $h$

as controlling variables. For the differential diffusion term in the enthalpy equation, the gradients of the non-transported species were approximated using the corresponding gradients in the 1D flamelets. Instead of 1D FP unstretched flamelets, the composition space model (CSM) (Scholtissek et al. Reference Scholtissek, Domingo, Vervisch and Hasse2019a

,

Reference Scholtissek, Domingo, Vervisch and Hasseb

) was used for generating the flamelet database, enabling the representation of flame structures from various canonical premixed flame configurations, including arbitrary combinations of strain and curvature (Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Scholtissek, Chen, Chen and Hasse2021). The model was applied to a spherically expanding TD unstable lean hydrogen/air flame and compared with a second model, also based on the CSM, in which the mixture fraction and the curvature of the flamelets have been varied (Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Lulic, Steinhausen, Wen, Hasse and Scholtissek2023). Instead of using curvature directly as a controlling variable, the H radical was employed as a second progress variable, resulting in a 3D manifold with a reduced mixture fraction and two progress variables. The newly proposed model showed improved accuracy for TD unstable flames, although discrepancies with DC simulations remain. Schepers & van Oijen (Reference Schepers and van Oijen2025) effectively combined the two aforementioned models and replaced the major species

$h$

as controlling variables. For the differential diffusion term in the enthalpy equation, the gradients of the non-transported species were approximated using the corresponding gradients in the 1D flamelets. Instead of 1D FP unstretched flamelets, the composition space model (CSM) (Scholtissek et al. Reference Scholtissek, Domingo, Vervisch and Hasse2019a

,

Reference Scholtissek, Domingo, Vervisch and Hasseb

) was used for generating the flamelet database, enabling the representation of flame structures from various canonical premixed flame configurations, including arbitrary combinations of strain and curvature (Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Scholtissek, Chen, Chen and Hasse2021). The model was applied to a spherically expanding TD unstable lean hydrogen/air flame and compared with a second model, also based on the CSM, in which the mixture fraction and the curvature of the flamelets have been varied (Böttler et al. Reference Böttler, Lulic, Steinhausen, Wen, Hasse and Scholtissek2023). Instead of using curvature directly as a controlling variable, the H radical was employed as a second progress variable, resulting in a 3D manifold with a reduced mixture fraction and two progress variables. The newly proposed model showed improved accuracy for TD unstable flames, although discrepancies with DC simulations remain. Schepers & van Oijen (Reference Schepers and van Oijen2025) effectively combined the two aforementioned models and replaced the major species

![]() $\textrm {O}_{2}$

with the

$\textrm {O}_{2}$

with the

![]() $\textrm {H}$

radical. This substitution is motivated by the significant contribution of the

$\textrm {H}$

radical. This substitution is motivated by the significant contribution of the

![]() $\textrm {H}$

radical to the differential diffusion of enthalpy. To construct their model, they employed a flamelet database generated from 1D FP flames with varying enthalpy and mixture fraction levels. Their approach demonstrated improved accuracy when applied to a 2D TD unstable FP flame, while discrepancies remain, for example, in the linear regime of TD instabilities.

$\textrm {H}$

radical to the differential diffusion of enthalpy. To construct their model, they employed a flamelet database generated from 1D FP flames with varying enthalpy and mixture fraction levels. Their approach demonstrated improved accuracy when applied to a 2D TD unstable FP flame, while discrepancies remain, for example, in the linear regime of TD instabilities.

2.1.2. Full mixture fraction models

In contrast, the foundation for the framework presented in this study, originally proposed by Oijen & Goey (Reference Oijen van and Goey de2000) and de Swart et al. (Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010) within the FGM framework (van Oijen et al. Reference van Oijen, Donini, Bastiaans, ten Thije Boonkkamp and de Goey2016), is not based on a reduced mixture fraction definition. In their formulation, constant Lewis numbers were assumed (i.e.

![]() $\textit{Le}_i$

does not vary across the flame front). They demonstrated that, under the manifold assumption, i.e. that any quantity

$\textit{Le}_i$

does not vary across the flame front). They demonstrated that, under the manifold assumption, i.e. that any quantity

![]() $\xi$

depends solely on the controlling variables, the diffusion terms in the transport equations of the controlling variable can be closed, as illustrated through the following considerations.

$\xi$

depends solely on the controlling variables, the diffusion terms in the transport equations of the controlling variable can be closed, as illustrated through the following considerations.

While diffusion terms could be computed directly during simulation using the manifold, this would require storing all species mass fractions and diffusion coefficients, causing significant memory and computational overhead. Instead, gradients are partially precomputed in the manifold, greatly reducing the number of variables retrieved from the table. For any manifold quantity

![]() $\xi (\mathcal{Y}_1, \ldots , \mathcal{Y}_n)$

(e.g. a species mass fraction

$\xi (\mathcal{Y}_1, \ldots , \mathcal{Y}_n)$

(e.g. a species mass fraction

![]() $Y_k$

), the total differential is defined as

$Y_k$

), the total differential is defined as

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial x_i} = \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{c}}} \left .\frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}\right |_{\mathcal{Y}_1,\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{j-1},\mathcal{Y}_{j+1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{n}} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial x_i} = \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{c}}} \left .\frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}\right |_{\mathcal{Y}_1,\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{j-1},\mathcal{Y}_{j+1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{n}} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i}, \end{equation}

where gradients with respect to the controlling variables

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

are precomputed within the manifold, while spatial gradients of the controlling variables are obtained during the simulation. (Note that in the following,

$\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

are precomputed within the manifold, while spatial gradients of the controlling variables are obtained during the simulation. (Note that in the following,

![]() $\left .{\partial \xi }/{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}\right |_{\mathcal{Y}_1,\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{j-1},\mathcal{Y}_{j+1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{n}}$

is abbreviated as

$\left .{\partial \xi }/{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}\right |_{\mathcal{Y}_1,\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{j-1},\mathcal{Y}_{j+1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{n}}$

is abbreviated as

![]() ${\partial \xi }/{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}$

.) Various approaches exist for this purpose, and the method employed in this work for calculating the gradients with respect to the controlling variables is discussed in detail in the following section. Assuming constant Lewis numbers, the diffusion flux is defined as

${\partial \xi }/{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}$

.) Various approaches exist for this purpose, and the method employed in this work for calculating the gradients with respect to the controlling variables is discussed in detail in the following section. Assuming constant Lewis numbers, the diffusion flux is defined as

![]() $Y_{k} V_{k,i} = - {\alpha }/{{\textit{Le}_k}}\,{\partial Y_k}/{\partial x_i}$

, which can be reformulated as

$Y_{k} V_{k,i} = - {\alpha }/{{\textit{Le}_k}}\,{\partial Y_k}/{\partial x_i}$

, which can be reformulated as

![]() $Y_k V_{k,i} = - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} ({\alpha }/{\textit{Le}_k} \, {\partial Y_k}{/\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}) {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} / \partial x_i = - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varLambda _{Y_k,\mathcal{Y}_l} \partial \mathcal{Y}_{l} / \partial x_i$

using (2.6).

$Y_k V_{k,i} = - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} ({\alpha }/{\textit{Le}_k} \, {\partial Y_k}{/\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}) {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} / \partial x_i = - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varLambda _{Y_k,\mathcal{Y}_l} \partial \mathcal{Y}_{l} / \partial x_i$

using (2.6).

For an exemplary controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

, the transport equation is given by

$\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

, the transport equation is given by

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left (\rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k} Y_k V_{k,i} \right ) + S_{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left (\rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k} Y_k V_{k,i} \right ) + S_{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}, \end{equation}

with the source term

![]() $S_{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}$

and the weighting factor

$S_{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}$

and the weighting factor

![]() $\varsigma _{j,k}$

of species

$\varsigma _{j,k}$

of species

![]() $k$

associated with the controlling variable

$k$

associated with the controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

, which, for example, corresponds to the weighting factor

$\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

, which, for example, corresponds to the weighting factor

![]() $a_{k}$

in the case of a reaction progress variable. The diffusion term in the

$a_{k}$

in the case of a reaction progress variable. The diffusion term in the

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

transport equation can be reformulated as

$\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

transport equation can be reformulated as

\begin{align} - \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k} Y_k V_{k,i} = \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k}\! \left (-Y_k V_{k,i}\right ) - \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} \notag \\ = \underbrace {\rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k}\! \underbrace {\left ( -Y_k V_{k,i} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_{\!p}} \frac {\partial {Y}_{k}}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{j_{k,i}}}_{\textit{differential diffusion}} + \underbrace {\frac {\kappa }{c_{\!p}} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i}}_{\textit{unity Lewis diffusion}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} - \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k} Y_k V_{k,i} = \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k}\! \left (-Y_k V_{k,i}\right ) - \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} \notag \\ = \underbrace {\rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k}\! \underbrace {\left ( -Y_k V_{k,i} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_{\!p}} \frac {\partial {Y}_{k}}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{j_{k,i}}}_{\textit{differential diffusion}} + \underbrace {\frac {\kappa }{c_{\!p}} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i}}_{\textit{unity Lewis diffusion}}, \end{align}

which is decomposed into a unity Lewis number contribution and a contribution accounting for differential diffusion, as proposed, for example, in the work of Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022). Using (2.6) (and the closure of the diffusion flux proposed above), the differential diffusion flux is obtained as

\begin{equation} \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}}\varsigma _{j,k} j_{k,i} = \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_{l}}\frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}}\varsigma _{j,k} j_{k,i} = \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_{l}}\frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

denotes the contribution of the controlling variable

$\varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

denotes the contribution of the controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{l}$

on

$\mathcal{Y}_{l}$

on

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

:

$\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

:

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{c},\mathcal{Y}_{l}} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l}^{*} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k}\! \left ( \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_p} \frac {\partial {Y}_k}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \right )\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{c},\mathcal{Y}_{l}} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l}^{*} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \varsigma _{j,k}\! \left ( \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_p} \frac {\partial {Y}_k}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \right )\!. \end{equation}

Finally, the transport equation for the controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

reads

$\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}$

reads

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left (\rho \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_l}\frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} \right ) + S_{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \rho \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial \rho u_i \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left (\rho \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_l}\frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} \right ) + S_{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}. \end{equation}

Based on these considerations, it becomes evident that the diffusion terms consist of two components: normal diffusion aligned with the gradient of each controlling variable and cross-diffusion (or drift) terms directed along the gradients of the other controlling variables. These terms effectively account for multidimensional differential and preferential diffusion effects. For instance, in a 2D manifold parametrised by the progress variable and the mixture fraction, the transport equation for each variable includes not only its own diffusion term but also an additional cross-diffusion term involving the gradient of the other controlling variable.

Some notes regarding the diffusion terms are as follows:

-

(i) In the original approach of Oijen & Goey (Reference Oijen van and Goey de2000), de Swart et al. (Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010), however, it was additionally assumed that the controlling variables

$\mathcal{Y}_i$

depend locally only on the progress variable

$\mathcal{Y}_i$

depend locally only on the progress variable

$Y_{{c}}$

, i.e.

$Y_{{c}}$

, i.e.

$\mathcal{Y}_i = \mathcal{Y}^{\textrm{1D}}_{i}(Y_{{c}})$

. This assumption effectively decouples the equations (as the cross-diffusion term in the progress variable transport equation vanishes) and implies that differential diffusion occurs only in the direction of the gradient of the progress variable. Donini et al. (Reference Donini, Bastiaans, van Oijen and de Goey2015) introduced enthalpy as an additional controlling variable and adopted the same assumptions as de Swart et al. (Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010). Mukundakumar et al. (Reference Mukundakumar, Efimov, Beishuizen and van Oijen2021) eliminated the additional assumptions by employing a mathematical reformulation that avoids the need to compute gradients within the manifold. Instead, additional terms are stored in the manifold, whose gradients are evaluated during the simulation. However, this approach is only valid under the assumption of constant Lewis numbers, as it relies on the spatial gradients of the Lewis numbers being zero.

$\mathcal{Y}_i = \mathcal{Y}^{\textrm{1D}}_{i}(Y_{{c}})$

. This assumption effectively decouples the equations (as the cross-diffusion term in the progress variable transport equation vanishes) and implies that differential diffusion occurs only in the direction of the gradient of the progress variable. Donini et al. (Reference Donini, Bastiaans, van Oijen and de Goey2015) introduced enthalpy as an additional controlling variable and adopted the same assumptions as de Swart et al. (Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010). Mukundakumar et al. (Reference Mukundakumar, Efimov, Beishuizen and van Oijen2021) eliminated the additional assumptions by employing a mathematical reformulation that avoids the need to compute gradients within the manifold. Instead, additional terms are stored in the manifold, whose gradients are evaluated during the simulation. However, this approach is only valid under the assumption of constant Lewis numbers, as it relies on the spatial gradients of the Lewis numbers being zero. -

(ii) Abtahizadeh et al. (Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015) and Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022) also relaxed the assumptions and included cross-diffusion fluxes between all controlling variables in the context of the autoignition of

$\textrm {CH}_{4}$

/

$\textrm {CH}_{4}$

/

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

flames (Abtahizadeh et al. Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015) and turbulent stratified

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

flames (Abtahizadeh et al. Reference Abtahizadeh, de Goey and van Oijen2015) and turbulent stratified

$\textrm {CH}_{4}$

/

$\textrm {CH}_{4}$

/

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

flames (Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022). However, as both studies also assumed constant, non-unity Lewis numbers, Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025) recently extended the model to incorporate a mixture-averaged diffusion formulation that also accounts for contributions to the diffusion fluxes arising from the correction velocity. Their flamelet database consists of FP flames with varying equivalence ratios and the extended model was tested on a stratified hydrogen/air triple flame and showed very accurate results. It was subsequently applied to 2D TD unstable FP hydrogen/air flames (Fortes et al. Reference Fortes, Pérez-Sánchez, Both, Grenga and Mira2025), where it also yielded good agreement with DC simulations with minor deviations, for example, in numerically obtained dispersion relations.

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

flames (Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022). However, as both studies also assumed constant, non-unity Lewis numbers, Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025) recently extended the model to incorporate a mixture-averaged diffusion formulation that also accounts for contributions to the diffusion fluxes arising from the correction velocity. Their flamelet database consists of FP flames with varying equivalence ratios and the extended model was tested on a stratified hydrogen/air triple flame and showed very accurate results. It was subsequently applied to 2D TD unstable FP hydrogen/air flames (Fortes et al. Reference Fortes, Pérez-Sánchez, Both, Grenga and Mira2025), where it also yielded good agreement with DC simulations with minor deviations, for example, in numerically obtained dispersion relations.

The framework employed in this work should incorporate the least restrictive assumptions in the model derivation, while ensuring the robust computation of diffusion terms, as the FWI introduces an additional effect that increases the complexity and further challenges the model. The least restrictive assumptions are provided by the previously introduced framework (Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022; Fortes et al. Reference Fortes, Pérez-Sánchez, Both, Grenga and Mira2025; Pérez-Sánchez et al. Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025), although these studies have focused exclusively on FP flames rather than on FWIs. Thus, the following section presents an extended modelling framework, which integrates a mixture-averaged diffusion model including thermal diffusion and accounts for heat losses via an additional controlling variable alongside the reaction progress variable and mixture fraction, usually employed for TC approaches focusing on TD unstable flames.

2.2. Detailed model formulation

First, the treatment of the (differential) diffusion terms for a mixture-averaged transport model including thermal diffusion is discussed. Subsequently, an extension of the framework to account for heat losses is proposed. Finally, a generalised procedure for accurately computing gradients of manifold quantities with respect to the controlling variables is detailed, as required for closure of the differential diffusion terms in the coupled simulations.

2.2.1. Closure of the diffusion terms

In this study, differential diffusion effects are taken into account by modelling the diffusive fluxes using the mixture-averaged approximation, including thermal (Soret) diffusion. Note that, in principle, any diffusion model can be used. In the supplementary material, the extension to the multicomponent diffusion model, including multicomponent thermal diffusion, is demonstrated and validated. Employing the mixture-averaged approximation (Hirschfelder, Bird & Curtiss Reference Hirschfelder, Bird and Curtiss1964), the diffusion flux in the transport equations is expressed as

where

![]() $V_{k,i}^{{D}}$

is the mixture-averaged diffusion velocity,

$V_{k,i}^{{D}}$

is the mixture-averaged diffusion velocity,

![]() $V_{k,i}^{{T}}$

is the thermal diffusion velocity and

$V_{k,i}^{{T}}$

is the thermal diffusion velocity and

![]() $V_{k,i}^{{C}}$

is the correction velocity, which is required for the non-mass conservative mixture-averaged approximation. Thermal diffusion is considered and is modelled using a simplified formulation from Chapman & Cowling (Reference Chapman and Cowling1990). It is applied only to light species with molecular weights

$V_{k,i}^{{C}}$

is the correction velocity, which is required for the non-mass conservative mixture-averaged approximation. Thermal diffusion is considered and is modelled using a simplified formulation from Chapman & Cowling (Reference Chapman and Cowling1990). It is applied only to light species with molecular weights

![]() $W_k \lt 5$

(specifically H and

$W_k \lt 5$

(specifically H and

![]() $\textrm {H}_{2}$

; see Reaction Design 2015; Schlup & Blanquart Reference Schlup and Blanquart2018; Howarth et al. Reference Howarth, Day, Pitsch and Aspden2024 for further details). Details on the formulation of the mixture-averaged diffusion velocity, thermal diffusion velocity and correction velocity are provided in the supplementary material. Overall, the diffusion flux

$\textrm {H}_{2}$

; see Reaction Design 2015; Schlup & Blanquart Reference Schlup and Blanquart2018; Howarth et al. Reference Howarth, Day, Pitsch and Aspden2024 for further details). Details on the formulation of the mixture-averaged diffusion velocity, thermal diffusion velocity and correction velocity are provided in the supplementary material. Overall, the diffusion flux

![]() $Y_kV_{k,i}$

of species

$Y_kV_{k,i}$

of species

![]() $k$

in direction

$k$

in direction

![]() $i$

is given by

$i$

is given by

\begin{align} Y_k V_{k,i} &= - D_{\textit{mix},k} \frac {\partial Y_k}{\partial x_i} - \frac {Y_k D_{\textit{mix},k}}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial x_i} - \frac {D_{\textit{therm},k}}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} \notag \\ &\quad + Y_k \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} \frac {\partial Y_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} + \frac {Y_k}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial x_i} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} Y_{\!j} \notag \\ &\quad + \frac {Y_k}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{therm},j}. \end{align}

\begin{align} Y_k V_{k,i} &= - D_{\textit{mix},k} \frac {\partial Y_k}{\partial x_i} - \frac {Y_k D_{\textit{mix},k}}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial x_i} - \frac {D_{\textit{therm},k}}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} \notag \\ &\quad + Y_k \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} \frac {\partial Y_{\!j}}{\partial x_i} + \frac {Y_k}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial x_i} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} Y_{\!j} \notag \\ &\quad + \frac {Y_k}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{therm},j}. \end{align}

Based on (2.6), similar to de Swart et al. (Reference de Swart, Bastiaans, van Oijen, de Goey and Cant2010), Nicolai et al. (Reference Nicolai, Dressler, Janicka and Hasse2022), Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025), the diffusion flux can be reformulated as

\begin{align} Y_k V_{k,i} &= - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \Bigg ( D_{\textit{mix},k} \frac {\partial Y_k}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} + \frac {Y_k D_{\textit{mix},k}}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} + \frac {D_{\textit{therm},k}}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \notag \\ &\quad - Y_k \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} \frac {\partial Y_{\!j}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {Y_k}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} Y_{\!j} \notag \\ &\quad - \frac {Y_k}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} {D_{\textit{therm},j}} \Bigg ) \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i} \notag \\ &\quad = - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i}. \end{align}

\begin{align} Y_k V_{k,i} &= - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \Bigg ( D_{\textit{mix},k} \frac {\partial Y_k}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} + \frac {Y_k D_{\textit{mix},k}}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} + \frac {D_{\textit{therm},k}}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \notag \\ &\quad - Y_k \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} \frac {\partial Y_{\!j}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {Y_k}{\overline {W}} \frac {\partial \overline {W}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} D_{\textit{mix},j} Y_{\!j} \notag \\ &\quad - \frac {Y_k}{\rho T} \frac {\partial T}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \sum _{j=1}^{N_{{s}}} {D_{\textit{therm},j}} \Bigg ) \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i} \notag \\ &\quad = - \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i}. \end{align}

This flux is included in the transport equations of the respective controlling variable (e.g. progress variable

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

).

$Y_{{c}}$

).

2.2.2. Extension to heat losses

To capture heat losses in flamelet manifolds, the flamelet database must be extended to account for heat losses within the flamelets. To distinguish these additional states, the enthalpy

![]() $h$

is typically employed as an additional controlling variable. However, in this study, temperature

$h$

is typically employed as an additional controlling variable. However, in this study, temperature

![]() $T$

has proven to be more suitable for the construction of manifolds involving differential diffusion and heat losses, which is discussed in detail in § 4. The transport equation for temperature can be derived from the enthalpy transport equation and is given by

$T$

has proven to be more suitable for the construction of manifolds involving differential diffusion and heat losses, which is discussed in detail in § 4. The transport equation for temperature can be derived from the enthalpy transport equation and is given by

\begin{align} c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho T}{\partial t} + c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho u_i T}{\partial x_i}\nonumber \\ &\quad = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left (\kappa \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i}\right ) -\! \left ( \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}}c_{{{p}},k} Y_k V_{k,i} \right ) \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} + \dot {\omega }_T^{\prime }, \end{align}

\begin{align} c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho T}{\partial t} + c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho u_i T}{\partial x_i}\nonumber \\ &\quad = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \left (\kappa \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i}\right ) -\! \left ( \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}}c_{{{p}},k} Y_k V_{k,i} \right ) \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} + \dot {\omega }_T^{\prime }, \end{align}

where

![]() $c_{\!p,k}$

is the specific heat capacity of species

$c_{\!p,k}$

is the specific heat capacity of species

![]() $k$

at constant pressure,

$k$

at constant pressure,

![]() $\kappa$

is the thermal conductivity and the heat release rate is defined as

$\kappa$

is the thermal conductivity and the heat release rate is defined as

![]() $\dot {\omega }_T^{\prime } = - \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}}h_k \dot {\omega }_k$

.

$\dot {\omega }_T^{\prime } = - \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}}h_k \dot {\omega }_k$

.

2.2.3. Controlling variable transport equations

Finally, the reformulated transport equations for the (up to) three controlling variables used in the manifolds employed in this study are provided.

The transport equation for the reaction progress variable

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

reads

$Y_{{c}}$

reads

\begin{align} \frac {\partial (\rho Y_{c})}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial (\rho u_i Y_{c})}{\partial x_i} &= \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \underbrace {\left ( \rho \sum _{l=1}^{N_{c}} \varGamma _{Y_{c},\mathcal Y_l} \frac {\partial \mathcal Y_l}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial Y_{c}}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{= -\,\rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{s}} a_k Y_k V_{k,i}} + \rho \dot {\omega }_{Y_{c}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial (\rho Y_{c})}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial (\rho u_i Y_{c})}{\partial x_i} &= \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \underbrace {\left ( \rho \sum _{l=1}^{N_{c}} \varGamma _{Y_{c},\mathcal Y_l} \frac {\partial \mathcal Y_l}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p} \frac {\partial Y_{c}}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{= -\,\rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{s}} a_k Y_k V_{k,i}} + \rho \dot {\omega }_{Y_{c}}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{Y_{{c}}} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k \dot {\omega }_k$

and

$\dot {\omega }_{Y_{{c}}} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_k \dot {\omega }_k$

and

![]() $\varGamma _{Y_{{c}},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

denotes the contribution of the controlling variable

$\varGamma _{Y_{{c}},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

denotes the contribution of the controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_l$

on

$\mathcal{Y}_l$

on

![]() $Y_{{c}}$

:

$Y_{{c}}$

:

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{Y_{{c}},\mathcal{Y}_l} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_{k} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l}^{*} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_{k}\! \left ( \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_p} \frac {\partial Y_{{c}}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \right )\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{Y_{{c}},\mathcal{Y}_l} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_{k} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l}^{*} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} a_{k}\! \left ( \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_p} \frac {\partial Y_{{c}}}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \right )\!. \end{equation}

For the transport equation of the elemental mass fraction

![]() $Z_e$

, it follows that

$Z_e$

, it follows that

\begin{align} \frac {\partial (\rho Z_e)}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial (\rho u_i Z_e)}{\partial x_i} &= \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \underbrace {\left ( \rho \sum _{l=1}^{N_{c}} \varGamma _{Z_e,\mathcal Y_l}\, \frac {\partial \mathcal Y_l}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p}\, \frac {\partial Z_e}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{=- \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{s}} \gamma _{e,k}\,\dfrac {W_e}{W_k}\,Y_k V_{k,i}} , \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial (\rho Z_e)}{\partial t} + \frac {\partial (\rho u_i Z_e)}{\partial x_i} &= \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}\! \underbrace {\left ( \rho \sum _{l=1}^{N_{c}} \varGamma _{Z_e,\mathcal Y_l}\, \frac {\partial \mathcal Y_l}{\partial x_i} + \frac {\kappa }{c_p}\, \frac {\partial Z_e}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{=- \rho \sum _{k=1}^{N_{s}} \gamma _{e,k}\,\dfrac {W_e}{W_k}\,Y_k V_{k,i}} , \end{align}

where

![]() $\varGamma _{Z_{e},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

denotes the contribution of the controlling variable

$\varGamma _{Z_{e},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

denotes the contribution of the controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_l$

to

$\mathcal{Y}_l$

to

![]() $Z_{e}$

:

$Z_{e}$

:

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{Z_{e},\mathcal{Y}_l} = W_e\sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \frac {\gamma _{e,k}}{W_k} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l}^{*} = W_e \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \frac {\gamma _{e,k}}{W_k}\! \left ( \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_p} \frac {\partial Y_k}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \right )\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{Z_{e},\mathcal{Y}_l} = W_e\sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \frac {\gamma _{e,k}}{W_k} \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l}^{*} = W_e \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} \frac {\gamma _{e,k}}{W_k}\! \left ( \varLambda _{Y_{k},\mathcal{Y}_l} - \frac {\kappa }{\rho c_p} \frac {\partial Y_k}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_l} \right )\!. \end{equation}

The transport equation of the temperature

![]() $T$

reads

$T$

reads

\begin{equation} c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho T}{\partial t} + c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho u_i T}{\partial x_i} = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}{\left (\kappa \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i}\right )} + \rho\! \underbrace {\left ( \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varGamma _{T,\mathcal{Y}_l} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{=\sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} c_{\!p,k} Y_k V_{k,i} } \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} + \dot {\omega }_T^{\prime },\end{equation}

\begin{equation} c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho T}{\partial t} + c_{\!p} \frac {\partial \rho u_i T}{\partial x_i} = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i}{\left (\kappa \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i}\right )} + \rho\! \underbrace {\left ( \sum _{l=1}^{N_{{c}}} \varGamma _{T,\mathcal{Y}_l} \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_l}{\partial x_i} \right )}_{=\sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} c_{\!p,k} Y_k V_{k,i} } \frac {\partial T}{\partial x_i} + \dot {\omega }_T^{\prime },\end{equation}

with the contribution

![]() $\varGamma _{T,\mathcal{Y}_l}$

of the controlling variable

$\varGamma _{T,\mathcal{Y}_l}$

of the controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_l$

to the temperature

$\mathcal{Y}_l$

to the temperature

![]() $T$

defined as

$T$

defined as

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{T,\mathcal{Y}_l} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} c_{\!p,k} \varLambda _{Y_k,\mathcal{Y}_l}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varGamma _{T,\mathcal{Y}_l} = \sum _{k=1}^{N_{{s}}} c_{\!p,k} \varLambda _{Y_k,\mathcal{Y}_l}. \end{equation}

To apply these transport equations in fully coupled simulations, the coefficients

![]() $\varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

must be computed from the gradients

$\varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_{\!j},\mathcal{Y}_l}$

must be computed from the gradients

![]() $\partial \xi / \partial \mathcal{Y}_k$

within the manifold. These gradients are efficiently evaluated during the construction of the tabulated flamelet manifold prior to the simulation, as detailed below.

$\partial \xi / \partial \mathcal{Y}_k$

within the manifold. These gradients are efficiently evaluated during the construction of the tabulated flamelet manifold prior to the simulation, as detailed below.

2.2.4. Calculation of gradients in the manifold

The following section outlines the calculation of gradients of quantities

![]() $\xi$

in the manifold for a general manifold with controlling variables

$\xi$

in the manifold for a general manifold with controlling variables

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_1$

to

$\mathcal{Y}_1$

to

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_n$

, as required in (2.14). An evaluation on the final manifold is not straightforward, as it is typically constructed in terms of normalised controlling variables. Therefore, a robust, generalised method is required for the efficient calculation of gradients with respect to the controlling variables. While Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025) proposed an approach for the controlling variables mixture fraction and progress variable, a general framework has not yet been established in the literature. Note that the proposed procedure also relies solely on the manifold assumption (i.e. that each quantity

$\mathcal{Y}_n$

, as required in (2.14). An evaluation on the final manifold is not straightforward, as it is typically constructed in terms of normalised controlling variables. Therefore, a robust, generalised method is required for the efficient calculation of gradients with respect to the controlling variables. While Pérez-Sánchez et al. (Reference Pérez-Sánchez, Fortes and Mira2025) proposed an approach for the controlling variables mixture fraction and progress variable, a general framework has not yet been established in the literature. Note that the proposed procedure also relies solely on the manifold assumption (i.e. that each quantity

![]() $\xi$

depends exclusively on the controlling variables) and introduces no further assumptions.

$\xi$

depends exclusively on the controlling variables) and introduces no further assumptions.

The controlling variables are normalised and stored on a regular grid to enable direct, search-free access and straightforward interpolation within the tabulated manifold. In this context, the normalised controlling variables (

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}$

to

$\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}$

to

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}$

) depend only on the preceding controlling variables through their respective normalisation bounds. They are independent of subsequent variables, as such dependencies would require iterative table access, something generally avoided in tabulated manifold approaches for performance reasons. Thus, a controlling variable

$\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}$

) depend only on the preceding controlling variables through their respective normalisation bounds. They are independent of subsequent variables, as such dependencies would require iterative table access, something generally avoided in tabulated manifold approaches for performance reasons. Thus, a controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_n$

is normalised as

$\mathcal{Y}_n$

is normalised as

Next, the manifold assumption

![]() $\xi = \xi (\mathcal{Y}_1,\mathcal{Y}_2,\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{n})$

is exploited. Applying the chain rule yields a coordinate transformation for any quantity

$\xi = \xi (\mathcal{Y}_1,\mathcal{Y}_2,\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{n})$

is exploited. Applying the chain rule yields a coordinate transformation for any quantity

![]() $\xi$

(note that

$\xi$

(note that

![]() $\big |_{\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j-1},\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j+1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}}$

is omitted here for brevity in the derivatives with respect to the normalised controlling variable

$\big |_{\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j-1},\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j+1},\ldots ,\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}}$

is omitted here for brevity in the derivatives with respect to the normalised controlling variable

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}$

):

$\mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}$

):

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} &= \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{1}} + \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{2}} \notag \\ &\quad + \ldots + \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{n}} \, . \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} &= \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{1}} + \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{2}} \notag \\ &\quad + \ldots + \frac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},j}} \frac {\partial \xi }{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{n}} \, . \end{align}

This can be expressed in matrix–vector form for all controlling variables

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_i$

:

$\mathcal{Y}_i$

:

\begin{equation} \underbrace { \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} \\[12pt] \vdots \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} \end{bmatrix} }_{\underline {g}_{\textit{norm}}} = \underbrace { \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} & \ldots & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} & \ldots & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} \\[12pt] \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} & \ldots & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} \end{bmatrix} }_{\underline {\underline {C}}} \underbrace { \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_1} \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_2} \\[12pt] \vdots \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_n} \end{bmatrix} }_{\underline {g}}\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \underbrace { \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} \\[12pt] \vdots \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} \end{bmatrix} }_{\underline {g}_{\textit{norm}}} = \underbrace { \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} & \ldots & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},1}} \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} & \ldots & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},2}} \\[12pt] \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_1}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_2}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} & \ldots & \dfrac {\partial \mathcal{Y}_n}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_{\textit{norm},n}} \end{bmatrix} }_{\underline {\underline {C}}} \underbrace { \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_1} \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_2} \\[12pt] \vdots \\[12pt] \dfrac {\partial \xi _i}{\partial \mathcal{Y}_n} \end{bmatrix} }_{\underline {g}}\!. \end{equation}

This expression can be inverted to obtain

![]() $\underline {g}$

from

$\underline {g}$

from

![]() $\underline {g}_{\textit{norm}}$

and

$\underline {g}_{\textit{norm}}$

and

![]() $\underline {\underline {C}}$

, whose entries can be directly computed on the (normalised) manifold:

$\underline {\underline {C}}$

, whose entries can be directly computed on the (normalised) manifold:

In this case, a linear system of equations must be solved. However, the relation in (2.22) can be exploited: if it holds for all controlling variables, the resulting matrix

![]() $\underline {\underline {C}}$

becomes upper triangular, since

$\underline {\underline {C}}$

becomes upper triangular, since

In this case,

![]() $\underline {g}$

can be directly determined from

$\underline {g}$

can be directly determined from

![]() $\underline {g}_{\textit{norm}}$

and

$\underline {g}_{\textit{norm}}$

and

![]() $\underline {\underline {C}}$

through back substitution.

$\underline {\underline {C}}$

through back substitution.

Furthermore, the entries of the matrix

![]() $\underline {\underline {C}}$

can be simplified through analytical derivation. The diagonal entries can be determined analytically from (2.22) as

$\underline {\underline {C}}$

can be simplified through analytical derivation. The diagonal entries can be determined analytically from (2.22) as

while the remaining non-diagonal entries can also be determined from a reformulation of (2.22):

These mathematical considerations enable the efficient calculation of the derivatives of any quantity

![]() $\xi$

with respect to the controlling variables

$\xi$

with respect to the controlling variables

![]() $\mathcal{Y}_i$

on manifolds of arbitrary dimension. This aspect will be discussed in more detail in the context of the specific manifolds used in this study (§ 4).

$\mathcal{Y}_i$

on manifolds of arbitrary dimension. This aspect will be discussed in more detail in the context of the specific manifolds used in this study (§ 4).

3. Numerical methods

Simulations in this work are performed using the open-source computational fluid dynamics library OpenFOAM (Weller et al. Reference Weller, Tabor, Jasak and Fureby1998), which employs the finite volume method.

For the DC reference simulations, the reactive compressible Navier–Stokes equations are solved. The reactive flow solver used for the simulations is an in-house solver derived from the standard OpenFOAM reactingFoam solver. In addition to the continuity and momentum equations, the species transport equations for all species

![]() $Y_{k}$

expect for

$Y_{k}$

expect for

![]() $\textrm {N}_{2}$

, which is computed from the constraint

$\textrm {N}_{2}$

, which is computed from the constraint

![]() $\sum _k^{N_{{s}}} Y_k = 1$

, and the enthalpy transport equation are solved. The ideal gas law is applied for closure of the system of equations. For detailed information on the DC simulations, the reader is referred to Schneider et al. (Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a

,

Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasseb

).

$\sum _k^{N_{{s}}} Y_k = 1$

, and the enthalpy transport equation are solved. The ideal gas law is applied for closure of the system of equations. For detailed information on the DC simulations, the reader is referred to Schneider et al. (Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a

,

Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasseb

).

For the TC simulations, the transport equations for the controlling variables of the respective manifold are solved in addition to the continuity and momentum equations. These simulations are conducted using an in-house solver derived from the standard OpenFOAM pimpleFoam solver. The quantities required in the equations, such as the density

![]() $\rho$

, transport properties (thermal conductivity

$\rho$

, transport properties (thermal conductivity

![]() $\kappa$

, diffusion coefficients

$\kappa$

, diffusion coefficients

![]() $\varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_i,\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}$

) and the source terms

$\varGamma _{\mathcal{Y}_i,\mathcal{Y}_{\!j}}$

) and the source terms

![]() $\dot {\omega }_{\mathcal{Y}_i}$

, are retrieved from the tabulated manifold, which is stored on a regular grid, using a non-search-based access method.

$\dot {\omega }_{\mathcal{Y}_i}$

, are retrieved from the tabulated manifold, which is stored on a regular grid, using a non-search-based access method.

To ensure comparability with the DC simulations, the same spatial resolution was used in all cases (

![]() $20$

points per thermal flame thickness, which has proven to be sufficient; see, e.g. Schuh, Hasse & Nicolai Reference Schuh, Hasse and Nicolai2024; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a

,

Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasseb

). An implicit second-order backward differentiation formula is employed for time integration, and second-order discretisation schemes are applied to all spatial derivatives, except for scalar convection, which is treated using a total variation diminishing limiter. The code is well validated and has been successfully employed in previous works (e.g. Schuh et al. Reference Schuh, Hasse and Nicolai2024; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Steinhausen, Nicolai and Hasse2024, Reference Schneider, Nicolai, Schuh, Steinhausen and Hasse2025a

,