Introduction

We invite you to walk or ride with us to regenerate an ethos featuring karlup bidi Footnote 1 , or pathways home. Along the way, we visualise the landscapeFootnote 2 of central Perth and Kaarta Koomba, Karrgatup or Kaart Gennunginyup Bo (Kings Park) as it has been over deep time, while bringing that learning into the continuing present. Noongar families may use different place names to describe landscape features (Collard et al., Reference Collard, Harben and Rooney2015). This is because place names may reflect ecological happenings (such as place of kangaroo), events (such as trading or meeting place), geographical features such as a hilltop or specific story locations and may change from time to time. In this account, we use Kaart Gennunginyup Bo for Kings Park because it is Collard and extended family network knowledge.

From an ecological perspective, three distinct plant communities feature in the 400 hectares of Kaart Gennunginyup Bo, according to the Urban Bushland Council of WAFootnote 3 (2025). These are limestone heathland; Banksia woodland (with bull banksia, slender banksia, firewood banksia and acorn banksia); and low moist areas featuring holly-leaved banksia. There are many common tree types including tuarts, jarrah, peppermint, wattles and marri.

In Noongar language, kaartdijin means learning or knowing. In this paper, we use some Noongar language to convey the story and culture of Noongar landscape in a Noongar voice, for inhabitants of Whadjuk Boodja to use in everyday lifewaysFootnote 4 . First author Len Collard explains:

Nyungar moort kaartditjin kura yeye boorda nguni wirrin nyinniny burranging ngullakiny. We the people of the Aboriginal families understand that in the past, same now and into the future, our ancestors as spirit are holding us all.

Please see Appendix A for a short list of Noongar words used in this paper. As you will see, boodja(Country), kaartdijin(knowledge) and moort (family) form the heart of a Noongar lifeway and through this paper we offer it to deepen social practices of regeneration. By this we mean to care for Country and the cultures that care for it like family. At Figure 1 is a simple map showing the broad region in relation to the rivers and ocean, showing Boorloo (a location in what is now known as PerthFootnote 5 ), which is the setting for this narrative.

Figure 1. Map of part of the Perth metropolitan area.

This paper addresses a key question in Critical Forest Studies related to cultural, temporal and linguistic dimensions of societal place-care, inclusive of regenerative narratives. It is: how can environmental educators help people come to know their localities as “home” in an Aboriginal sense? It illustrates a way to deepen one’s sense of place, by engaging Aboriginal onto-epistemologies, imagination and practical experience of walking places in ways dedicated to learning and transformation. It contributes to the environmental humanities, to critical forest studies and to the literature on regenerative cultures.

This Kaartdijin bidi, or learning pathway, begins with some small yarns to help understand a Noongar worldview as distinct from colonial-corporate perspectives. Noongar wellbeing from a cyclical/seasonal standpoint is next, using historical prose that is based on the work of Stasiuk et al. (Reference Stasiuk, Taylor, Sillifant, Hardy, Newsome, Ladd, Craig, Kennedy, Kent, Owen and Somerville1998). After this, we hear colonial stories, all the while recognising that these knowledge sets are shared by Noongar on a regular basis. All these stories live on in places. The final part of karlup bidi takes the form of a storied walking/riding trail.

Through this learning journey “homewards” to knowing place anew, we illustrate how Boodja or Country and karlup or home place, is key to knowledge for place-family relations. To illustrate Noongar time as past–present, in this paper we use present-continuing tense where possible.

Baranginy Kaartdijin – Searching for knowledge: Whose story?

When we want to understand a Noongar interpretation of place, the pathway to learning can be tricky. The discipline of history – or what is known as history – has a very interesting history itself! History is (or has been) his story, and it often tells the story from the “victor’s” perspective. This means that most available records present a male, coloniser standpoint – even though there are multiple viewpoints on any event. A strong historical account will provide men’s stories, women’s stories, place-stories, children’s stories and accounts by people of a variety of ethnicities, particularly those who may be the subject of the history. Due to oppressive colonial practices, published Noongar historical accounts from Noongar standpoints are uncommon in Western Australia until the 1970s and 80s. Colonial authors (such as Bates, Reference Bates1909) generally offered Noongar stories to a totally different audience and in a different way than her Noongar story tellers might have intended.

This paper includes historical disruptions brought by colonisation, sketching how Noongar leaders navigate loss, negotiation and resistance; co-creating resilience through cultural strength. We bring the narrative together in a trail for walking through Kaart Gennunginyup Bo and walking or riding along Derbal Yerrigan, which is called derbal or estuary because of its mixing of salt and fresh waters adjacent to several important Noongar camps. We refer to many websites in this paper, footnoted to easily supply images and voice. These are gathered at Appendix B.

Before setting out on our journey, we acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of Australia and recognise their ongoing role, responsibilities and continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Len is boordiya (cultural leader) for this research and is a Whadjuk Noongar Traditional Owner of the Perth Metropolitan area and surrounding lands, rivers, swamps, ocean and culture. Len’s kaartdijin bidi – his own learning journey – has taken up much of his life’s work. Noongar kaartdijin bidi has taken up much of Sandra’s life’s work too, through collaboration on many Noongar history and language projects, some of these with Len. Louisa is a geographer, philosopher, mapmaker, co-author and colleague who has recently completed her PhD. This research was conducted as per the Notre Dame Human Research Ethics Committee guidelines, approval 2023-062.

Kaartdijin bidi – Learning journey

In Noongar boodja, another wangkiny (language) has covered an ancient wangkiny, and some new placenames have replaced original ones. But if we look under that layer of time, we can all share the vibrant, rich, and continuing Noongar history. We can value the Noongar lifeway through stories left for us by Elders and moort that explain relations, culture, weirn (spirituality), food and kaartdijin (knowledge) (Collard & Martin, Reference Collard and Martin2019, p. 2)

In this paper we look under that layer of time to learn how to respect and care for Noongar places using Noongar wisdom, through schools, universities and society. This has potential to collaboratively enrich a modern Perth in times of rapid social change. At the start, we encourage you to think of time in a Noongar way, which holds millennia of wisdom. It allows us to understand our places creatively and deepens our sense of what it means to inhabit Whadjuk boodja. This imaginative, visual, experiential and practical way of thinking can help understand events of the past and walk or ride together in this landscape, which always was and always will be Noongar Land – as the South West Native Title Settlement attests (Government of Western Australia, 2016). Ecologists, staff, volunteers and visitors use and care for Kaart Gennunginyup Bo in ways continuous with the practices handed on from carers of the past. The place offers engaging education programmes, such as the Noongar Boodja Six Seasons programmeFootnote 6 , and a range of cultural toursFootnote 7 .

This narrative is designed to help residents and visitors recognise themselves as part of Whadjuk boodja and incorporate these practices into our own ways of knowing, being, doing and understanding. In colonial history, these care practices between landscapes and people changed. Reconnecting the past with the present in a Noongar way is an important step in regeneration.

Wangkiny: S mall y arns for Kaartdijin bidi

Since our everyday practices often use habitual ways of thinking that we may not be aware of, these small yarns are to assist readers in understanding a Noongar worldview and to help us see the big picture more clearly. By worldview, we mean the sum-total of values, assumptions and beliefs about what is important in the world and in our lives. A worldview is our way of seeing the world from one’s own personal-cultural perspective. One’s worldview affects communication, and people can find it difficult to converse if they are starting from different core principles (Wooltorton et al., Reference Wooltorton, Poelina and Collard2022).

A participative worldview understands the world as interconnected, emphasising healthy relationships among all beings and concepts, rather than seeing separations between them. In Noongar culture, waugyl is an ancestral being who is the spiritual protector of waterholes and a great connector of landscapes, places and people, through shared cultural meanings across boodja. Bidi connect places, and moort – family relationship systems – connect people and places. As Collard writes, in Noongar culture three overarching and inseparable concepts are moort (family relationships), boodja (Country) and kaartdijin (knowledge) (Collard et al., Reference Collard, Harben and van den Berg2004). This worldview informs Noongar culture and practice.

You are welcome to jump to Appendix A and B at times, to learn and incorporate language, concepts and images.

Wangkiny (talking) or yarning (sharing) is a way of communicating and learning that gives respect to every person in the group, particularly the leader, boordiya. No person’s view is more – or less – important than anyone else’s (Wain et al., Reference Wain, Sim, Bessarab, Mak, Hayward and Rudd2016). In this project, with Len’s boordiya leadership, decisions are made by wangkiny or yarning. Most yarning circles are collaborative, democratic and cooperative, and everyone listens carefully to boordiya. Some yarning circles use facilitation, and in these cases, the facilitation needs to be “invisible,” to focus participants upon the process of listening. The big idea behind wangkiny or yarning, is “we not me.” This is a way to prioritise the interests of the group. In Noongar language, wangkiny and dwangk (ears) have a common stem. To yarn involves listening and speaking.

‘We not me’ is a concept described by Anne Poelina and others (Cameron & Poelina, Reference Cameron and Poelina2021). It reminds readers that in Aboriginal community governance and various types of cooperative meetings, the interests of the individual are backgrounded while foregrounding the interests of the group. This is not to say that individuals and their issues are not important, but it is a fundamental way of thinking that brings forward community interests. For local communities in Noongar boodja, this way of making decisions dramatically changes during early colonial times.

Boodja, Country. In Australia, when the word Country is capitalised, it refers to a more complex notion than the standard English usage of the word. Country is Boodja, which includes spirituality, social systems, well-being, kinship, laws and obligations to care for karlup, or home place. To apply this thinking, imagine that a beautiful tree in your neighbourhood is a kin relation that recognises you and cares for you, and for which you care in return. How does this change the way you move through your neighbourhood? Throughout boodja, bidi criss-cross places and landscapes, as Noongar are family people with seasonal obligations to undertake certain tasks, ceremonies and maintenance protocols.

Karlup (or kaleep) is a very important concept in Noongar culture. Karlup is the home place of a family group and the boordiya of that family is responsible for proper cultural burning of it, to ensure the ecosystem is maintained. Karlupgur (or kaleepgur) are the people who belong to that karlup and are its rightful owners. Karl means both home and fire/hearth. Home does not refer to a building, as it does in English, but to the living ecosystem of which people are an important part. A koornt, or maya maya (hut), is an ephemeral or temporary structure, that is renewed on each seasonal return – a koornt is not “home,” karlup is. See Figure 2 for an image of a maya in the early 1900s.

Figure 2. Camp at Herdsman’s Lake, Njookenbooro, early 1900s. Photo: Noongar Culture.

Noongar understand that we are interrelated with karlup and responsible for caring for boodja, a language-embedded relationship. For example, beeliar refers to both the river and the people of the river, and derbalung describes the people of the derbal, or estuary (Bates, Reference Bates1909). In Noongar tradition and identity, people and place interweave and cannot disconnect without great emotional and physical pain. Anthropologist William Stanner, based on his work in Northern Australia, commented that there are no English words that can give a sense of the connection between Indigenous people and their homeland (Stanner, Reference Stanner1979). We might think about this linkage as enmeshment. Stanner says:

When we (colonisers) took what we call ‘land’ [from Aboriginal people] we took what to them meant hearth, home, the source and locus of life, and the everlastingness of spirit (Stanner, Reference Stanner1979, p. 230).

Bidi is a very important term in this literature review because pathways lead us to shared destinations. Metropolitan Perth holds many bidi, or Noongar pathways, some of which the initial colonisers follow with Noongar guidance. Nowadays, these bidi form roads and pathways that many of us travel daily. In this simple way we can see how the past and the present enmesh, and this knowledge helps us to understand ways of continuing together. Interestingly, bidi co-arises with the word boordiya(sometimes spelt like bidiya), which means Elder or leader; a person of significant respect because of their knowledge of pathways through karlup, homeplace (Wooltorton et al., Reference Wooltorton, Collard and Horwitz2015). Further research shows that ‘Bidi’ or ‘Biritt’ is one of the names of what we now call Perth.

Ni! (listen!) and kaartdijin (understanding) are Noongar ways of deep listening to places and people. This form of listening involves deeply attentive skills and practices, as well as a foundational view of boodja, Country, as a sentient, living, feeling participant. To try this, sit quietly in King’s Park or beside a healthy river with your eyes closed. What do you hear that you do not usually notice in a busy day? It needs a lot of practice if this is new for you. Underneath listening, learning and responding to boodja is the important notion of care. As Noel Nannup says (Reference Nannup, Morgan, Mia and Kwaymullina2010), Noongar are traditionally carers of everything. Care of place is the heart of life, necessary for the wellbeing of all human and more-than-human beings. To look after our animate, thriving places is to look after culture and each other.

Colonisation is a practice of making and imposing decisions from elsewhere onto a particular group of people. We know about historical colonisation in which decisions made in England impose upon Noongar people in southwest Western Australia. After arrival, the colonisers disembark at Derbal Nara (now called Cockburn Sound, but it is still Derbal Nara) and the coastal waters around Walyalup (now also known as Fremantle), then travel up the river, renaming it Swan River. (You might like to refer to Figure 1 to visualise this.) They take up a location they later call Perth (Stocker et al., Reference Stocker, Collard and Rooney2016). Colonisation involves making new rules for Noongar places, without understanding the history, stories, or biocultures of places. The colonisers initially seem to have respect for Noongar because they need to ask for directions and sources of freshwater. In most cases, Noongar helpfully oblige, in accordance with cultural protocols of welcome (Collard et al., Reference Collard, Harben and Rooney2015). Nonetheless, Perth’s is a military colonisation.

Generally, colonisers cease their respectful ways once the colony establishes, because they want to control Noongar boodja and use it for economic gain (Aborigines Protection Society, Reference Society1837). Soon, there are many violent clashes, widespread Noongar imprisonment and later, the use of force to remove Noongar from their karlup, homeplace, to camps on the outskirts of Perth and country towns (Haebich, Reference Haebich1992). Colonisation continues today, whereby people elsewhere make decisions relating to Aboriginal people and places. This happens frequently in WA and is a form of power-over (Poelina et al., Reference Poelina, Brueckner and McDuffie2021). It is anticipated that now with the Southwest Native Title Settlement in place, cultural governance will take hold once again to strengthen Noongar place-based decision-making.

The Southwest Native Title Settlement formally recognises the living Noongar cultural, spiritual, familial and social relationship with boodja that is continuous since time immemorial (South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, 2016). The Southwest Native Title Settlement is a step towards decolonisation, which is a way of removing colonial power-over structures and allowing the restoration of cultural governance, which returns deep respect for Noongar Elders and ways of knowing, being and doing. Decolonisation and decolonial thinking can become part of one’s worldview within daily life and work.

Time is an important concept that is deeply cultural. For example, modern consumerist lifeways use a linear sense of time. We often see this as dates in a straight line from the past to the future, depicting how significant events take place from one point of view. A linear sense of time carries an assumption that the past is past, and gone (Wooltorton et al., Reference Wooltorton, Collard, Horwitz and Ellis2019). Some people even say, “let it go, it belongs in the past and we need to move on with the present and plan the future.” In our heart of hearts, many of us know this is not the case, because we understand how trauma in the past can keep recurring in the present until we deal with it. Some pain never leaves us, neither do some pleasures.

Noongar Time is a sense of time in which the past is always with us, without disappearing. The concepts of kura, yeyi, boordawan – past, present and emerging – blend into the long now (Poelina et al., Reference Poelina, Wooltorton, Harben, Collard, Horwitz and Palmer2020). This means that all things “happen” rather than talking of occurrences that “have happened” or “are happening” or “will happen.” Seasons, rhythms and patterns bring about a cyclical sense of time in which the stories of the past–present continue and inform what we do every day, which produces the emergent. In this way, we see the ancestral creators are still with us today, shaping our lives and lifeways. Past colonial violence does not go away either, making truth-telling necessary for justice and social transformation for all Western Australians. Unresolved issues continue to cause pain and trauma, often continuing as lateral violence. Changing practices towards those that are respectful of Noongar truths, histories and presence in the long now is also a key part of addressing climate change and species loss, given that Noongar culture preserves healthy systems for millennia. This recognition is becoming known internationally as re-indigenisation.

Re-indigenisation reconnects the people of the planet with their local part of the planet. Indigenous teaching for transformative learning is becoming increasingly well known, particularly for re-shaping responses to global crises (Williams, Reference Williams2019, Reference Williams2021). Re-indigenisation is a way of learning, valuing and practising Indigenous ways of knowing and being in landscape. To try this, imagine the landscape you see on the way home from work as it was in pre-colonial times, like Noongar language, just underneath how it is today. With practice, you’ll be able to interweave both in your mind’s eye. What are the connections you see that bring the past into the present? Re-Indigenization creates a learning journey of decolonisation that brings everyone together with a common purpose. To genuinely be decolonising though, we need to deeply engage with truth telling. This is significant for Australians of all ancestries, because the past never goes away. Its archetypes and shadows remain – like any trauma – embedded in individual and national memories, in stereotypes. assumptions and statistics. Having looked under the layers of time and engaged with small yarns for reflective learning, we continue walking the pathway for a year of Noongar seasons.

Noongar Boodja and belonging: Seasons and cycles

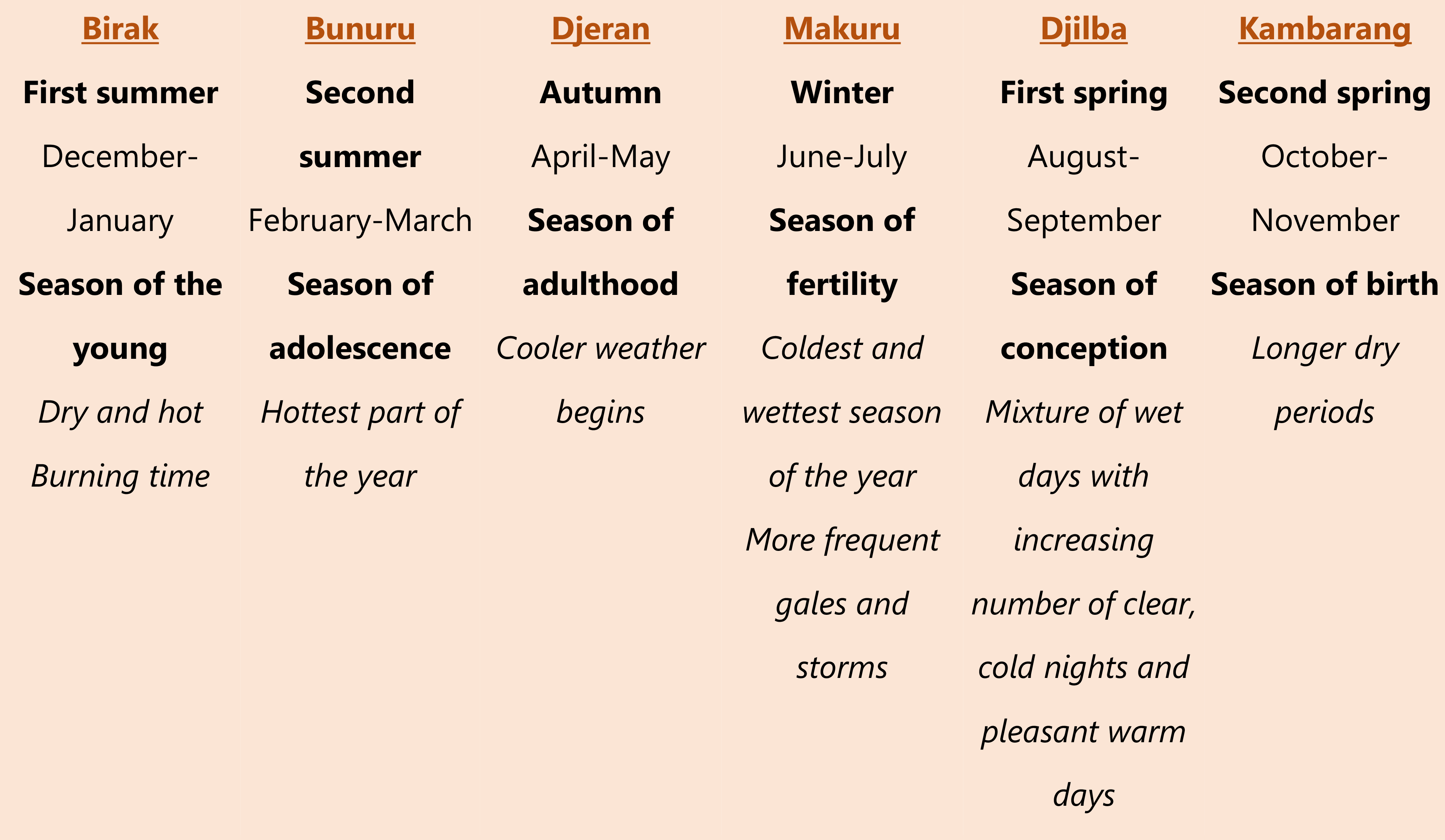

Understanding the seasons in Noongar lifeways makes this kaartdijin bidi – learning journey – experiential and practical. See Figure 3 below for a Noongar Seasons summary.

Figure 3. Noongar seasons (using information from Stasiuk et al. Reference Stasiuk, Taylor, Sillifant, Hardy, Newsome, Ladd, Craig, Kennedy, Kent, Owen and Somerville1998).

We highly recommend that you download and read the chart at Stasiuk et al.Footnote 8 (Reference Stasiuk, Taylor, Sillifant, Hardy, Newsome, Ladd, Craig, Kennedy, Kent, Owen and Somerville1998) and take time to understand the detail of the Noongar calendar each season, as it is a guide to healthy living in Noongar boodja. You may wish to keep observations of animal, plant, bird and weather cycles; to learn to feel and hear our everyday ecosystem with Noongar wisdom.

The enmeshment of Noongar people within their karlup and with their homeplaces as ecosystems means that health includes the wellbeing of moort, kaartdijin, boodja: family, ways of knowing, Country, spirituality, community and individual health. Noongar wellbeing includes the cultural big picture, including various uses of fire, smoking ceremonies, charcoal, coals, different kinds of clay and mud such as termite clay, animal fats and oils, and of course different plants. Plant medicines integrate with everyday activities and stories for life. For example, the custom of sitting around a fire maintains socio-emotional wellbeing, as well as keeping away mosquitoes and bugs, and discouraging bad spirits.

Djinanginy Kaartdijin: Seeing, feeling and understanding

In this section, a kaartdijin bidi or learning journey takes readers through narrative prose to comprehend one year of living in the seasonal cultural landscape of metropolitan Perth. Noongar are people of song (Bracknell, Reference Bracknell2019), drama, arts and story . As reminder, below we offer a refrain or chorus between seasons to convey a sense of active, place-alive cultural practice. For this narrative we used the work of Stasiuk et al., on Noongar seasons (Reference Stasiuk, Taylor, Sillifant, Hardy, Newsome, Ladd, Craig, Kennedy, Kent, Owen and Somerville1998) with Len’s stories from his grandfather (Bennell, Reference Bennell1993).

Birak, warming weather: easterlies in the mornings, afternoon sea breezes, rains slow and mostly stop. Mungaitch (jam wattle) is in full blossom; moodjar (Christmas Tree) begin to bloom so that the skies shimmer. Walking towards the west, Jualbup binjar koorliny, following bidi to the lakes and swamps. It is manju (trade) time, ready for collecting wilgi (ochre), assembling extended families. Fishing by firelight and torchlight for goodinyal (cobbler fish), goonak and tjilki (small freshwater crays)Footnote 9 . Formal teachings for teenagers, lessons in life for all children. Obey all the rules. Len’s grandfather Tom Bennell says: “… them tjilkies when we was kids they never let us touch ‘em till after Christmas”.Footnote 10

Campfires for wangkiny and yarning, dancing midar and yalgor, every night. Smoking as part of healing, ceremonies for newborns to keep them safe and help them grow up strong. New mothers are smoked as well, sometimes treated with steam to strengthen their bodies at this precious time.

In birak, reptiles shed old skin for new skin, fledgling birds leave the nests. It is season of the young. Kooyar frogs are fat and good to eat but hiding now. Steeping mungaitch (jam wattle flowers) in freshwater hollows, drinking happily. Boordiya maaman (men leaders with young men) firing karlap in mosaic patterns responding to vegetation type, young men droving yonga; opening up boodja.

Wangkiny, yarning, every sunset, performing the day as reflection. Songs celebrate and remember ancestral kaartdijin, characters of the everywhen, acknowledging waugyl and sacred places. Weirn moorditj: strong spirit.

Bunuru, hot time, little rain. Hot easterly winds blow. Marri is in flower, a signal to walk bidi to the coast for salmon and afternoon cooling breezes. Visit Derbal Nara Footnote 11 : estuary and bays of salmon. Mainly fishing now, traps, nets, gidji (spear) by daylight and torchlight, in estuaries, wetlands and lagoons. Cones are forming and turning red on the Djir-ly Zamia flowers. Burying them in sandy waterways produces good eating. Boordiya firing binjar swamp country, preparing for yanget bulb regrowth. Keep an eye out for waidtj – the emu, then catch him for good tucker for family.

Wangkiny, yarning, every sunset, performing the day as reflection. Songs celebrate and remember ancestral kaartdijin, characters of the everywhen, acknowledging waugyl and sacred places. Weirn moorditj: strong spirit.

Djeran features hot days with cooling, progressively longer nights. Light breezes from the south keep temperatures pleasant. Sunsets are often a time for flying ants. Red flowers arrive, red flowering gum, kangaroo paws, some eremophila and summer flame flower; brown sheoak flowers begin to flower. Several species of banksia flower, offering nectar to small birds. Zamia cones from last year are now ready to eat, along with djubak (native potato) and yanget after careful preparation in Bunuru. Eating turtles, frogs and freshwater fish. Karda, racehorse goanna is nice and fat, ready to eat. Repair maya shelter for water proofing, rain begins. Use kangaroo skin to make bwoka (warm coat), attach buttons, prepare for the coming cold weather.

Wangkiny, yarning, every sunset, performing the day as reflection. Songs celebrate and remember ancestral kaartdijin, characters of the everywhen, acknowledging waugyl and sacred places. Weirn moorditj: strong spirit.

Makaru is cold, wet and sometimes stormy. Follow bidi inland to karlup – small groups of karlupgur – family of karlup. Rain across the landscapes. Wetlands, rivers, lakes and waterholes fill. Hunting yonga, koomal and waidtj, kangaroo, possum and emu, are important food sources. Cooking fires are nice and warm. Pairs of ravens fly together, flying intently and quietly. Marlee, black swan, prepares for nesting and breeding. Everything is fertile, in togetherness, some creatures attend to territoriality, some quarrelling for mates. Purple flowers begin, making way for the white, yellow and cream flowers of djilba, such as the white flowers of the peppermint tree.

Wangkiny, yarning, every sunset, performing the day as reflection. Songs celebrate and remember ancestral kaartdijin, characters of the everywhen, acknowledging waugyl and sacred places. Weirn moorditj: strong spirit.

Djilba, sometimes called ‘first spring’, offers a profusion of flowers in the southwest. Yonga, koomal and waidtj, kangaroo, possum and emu are important food sources. Yellow Acacias and soon, purple climbers flower across boodja. Kwongan, flowering heath of the sand plains is wildly alive with blossoms, insects and birds of all kinds. Cold nights and warming days are mostly clear and crisp. Follow bidi eastwards, the waugyl form can often be seen across a cloudy sky, proclaiming thunder and approaching rain, followed by sun. Acknowledge waugyl, sing out welcome.

Rivers swell with water, sometimes brown and sometimes clear. Wetlands are brimming with fish and lively activity, ngamar – water holes – are still full, and as the weather warms there is food for feasting aplenty. Leave birds like ducks and swans on nests for later. As the weather warms, the balga – grass tree – flowers. The balga is a very significant tree for Noongar, for medicinal, dietary and tool-making purposes. For instance, its resin is useful for tanning kangaroo (yonga) hides, as a glue, to start fires and to make booka Footnote 12 .

Wangkiny, yarning, every sunset, performing the day as reflection. Songs celebrate and remember ancestral kaartdijin, characters of the everywhen, acknowledging waugyl and sacred places. Weirn moorditj: strong spirit.

Kambarang offers still more flowers, while boodja is drying out. Banksia candles are re-emerging, moodjar is beginning to shine again, djubatj is blooming. Occasional showers, while days are warming, waters are receding, streams are flowing, brooks are babbling and soil is rich. Aliwah! Watch out for snakes, basking in the warmth: hungry and waiting. Animal babies are birthing, baby lizards are everywhere, and nestlings are screaming for mother to bring ever-more food. Parents such as koorlbardi (magpies) are protective of babies and nests. The world transforms as the weather warms. Still hunting waidtj, and tasty koomal possums. Beside a river, pick up a handful of sand, rub it under your ngai, your armpit, and sing out to waugyl. Let waugyl the river’s living spirit, know you are keen to learn Noongar ways of knowing, being and doing. Have your river fishing gear ready, licences in hand, and admire the turtles.

Wangkiny, yarning, every sunset, performing the day as reflection. Songs celebrate and remember ancestral kaartdijin, characters of the everywhen, acknowledging waugyl and sacred places. Weirn moorditj: strong spirit.

The long now is central in this narrative, a way of understanding time that includes the past, present and future – kura, yeyi, boordawan – all experienced together in the “yeyi,” now – on a seasonal basis, over and over again. Having considered a year of seasons in the life of Kaart Gennunginyup Bo and nearby boodja, the heart of the locality now known as Perth, let’s continue homewards. Since the pathway navigates modernity, it necessarily includes truth-telling as we cannot know the present without the past.

Yorga, Maaman, Kurrlong: Karlupgur women, men, children of place

On the riverside directly below Kaart Gennunginyup Bo Footnote 13 , looking towards the University of Western Australia, is the river-side camp of Yellagonga, a clan boordiya (Elder) at the time of colonisation. The location is the Swan River foreshore near a sacred wetland with permanent springs called Goonininup (Bates Reference Bates1909; Lyon, Reference Lyon1833). When the colonisers arrive, the 63rd regiment move onto Yellagonga’s camp and take possession. Yellagonga and family soon move to Galup, or Lake Monger. See Figure 4 for a photograph of the Galup camp in 1923. Galup is also karlup, or home place.

Figure 4. Women and children, at the Perth Zoo, between 1885 - 1902. Fanny Balbuk Yoreel is in the white dress on right. Photo: State Library of Western Australia.

The records indicate Yellagonga to have been a pacifist, who had what Lyon calls “martial courage” and the deference of boordiya from other boodja. “To him the settlers are greatly indebted for the protection of their lives and property.” (Lyon, Reference Lyon1833).

Similarly Miago, whose boodja is the Upper Swan area, is frequently described as a peace messenger and an excellent guide and tracker Anon (1835). His granddaughter, Fanny Balbuk, tells Daisy Bates that Kuraree is one of his favourite camps until it becomes the location of the Perth Town Hall. MiagoFootnote 14 is a relationship builder with the colonisers from the beginning, and he becomes a mediator and interpreter, working to find ways for Noongar to maintain their culture as their world turns upside down (Bates, Reference Bates1909). After the Pinjarra Massacre, Miago organises a meeting between some Murray River people and Governor Stirling, after which is a jeena middar, or corroborree, held in the vicinity of Kuraree (Anon, 1835).

Further evidence of his peacekeeping are in a Perth Gazette and Western Australian journal article on 7 September 1833, notably his visit to the Lieutenant Governor to request a treaty with the colonisers after sixteen Noongar men are shot for stealing flour (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1833). The men’s hunger is due to prevention of Noongar hunting and gathering on their karlup. During this period, resistance by Noongar people to the colonial invasion is referred to as “mischief.” We can never be certain of the number of murders carried out for creating “mischief,” such as a reported ‘skirmish with a strong party, who were evidently determined upon mischief’ in which 30 to 40 Noongar people are massacred (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Debenham, Pascoe, Smith, Owen, Richards, Gilbert, Anders, Usher, Price, Newley, Brown, Le and Fairbairn2022).

Fanny Balbuk Yoreel is one of Perth’s first environmental protesters (Pickering, Reference Pickering2017). See Figure 5 for a photograph of Fanny. Granddaughter of Yellagonga and niece of Yagan (Pickering, Reference Pickering2017) she opposes development that would impede Noongar from travelling along their bidi and impact on cultural practices. It seems that Ms Balbuk Yoreel breaks down fences and other new obstructions in her way, when she walks her bidi from the islands and mudflats of Matagarup to a Gooloogulup swamp (now under or near the Perth train station). She collects tjilkies and bush tucker like yanjid which are the bulbous roots of the bulrush. Her path takes her past the Kureejup camp (now the corner of Adelaide Terrace and Hill Street), near the springs and shoreline of Dyeedyallalup (now Langley Park) (Western Australian Museum, nd-b).

Figure 5. Aboriginal Camp Galup 1923. Photo: State Library of Western Australia.

According the Western Australian Museum (nd-a), Fanny Balbuk was born in 1840 at Matagarup (a “leg deep ford” where the Causeway now stands), and her mother was born at Yoonderup (a small island off Burswood)Footnote 15 . Fanny lives with an Aboriginal man named Jimmy at a camp on Victoria Avenue, near the river in Claremont, in the late 1890s. They work for William and Louisa Caporn who live nearby, doing domestic tasks such as chopping wood, helping with washing and sweeping the paths. In return they apparently receive some food, clothes and boots. The family also stays at Guildford, perhaps for a fortnight at a time, shifting between the two camps – a walk along the river of about 24 km. Sometimes people from the Guildford camp come to stay with them at the Claremont camp (Cook, Reference Cook2019).

In recorded histories there are multiple examples of ‘kindness’ shown by colonising families such as the Caporns, and many good memories have been passed down through the generations of kind, mutual relationships. However, the overarching government context of the colony is one of increasing control and regulation of Noongar lives, livelihoods and lands. Ultimately, the colonisers claim Noongar boodja for themselves, and Noongar resistance to this is forced to cease (Haebich, Reference Haebich1992).

Wretched times

There is considerable historical evidence that the colonisers are generously welcomed by Noongar people to Country. However, while the stories we can draw from the records include humane, descriptive, generous accounts, the historical context of these records is sometimes very different. In early colonial Perth, there is shocking racism, destruction of Noongar places, particularly wetlands, and multiple forms of violence between colonisers and inhabitants. There is no doubt that the colonisers are very aware of Noongar opposition to the plans to develop a colony. The following comment about Yagan (a Noongar warrior), attributed to George Fletcher Moore by Reece (Reference Reece2019), appeared in a Perth newspaper in 1833:

I thought, from the tone and manner that the purport was this: ‘You came to our country—you have driven us from our haunts’Footnote 16 , and disturbed us in our occupations. As we walk in our own country, we are fired upon by the white men, why should the white men treat us so?’ (Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal 1 June 1833, 87, in Reece, Reference Reece2019).

Yagan along with his relation Hegan are murdered (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1833), Yagan at the hands of two boys for a government financial reward (Reece, Reference Reece2019). Similarly, in 1834 the Pinjarra Massacre of 80 or more Noongar is led by the Governor of Western Australia, Captain James Stirling. Referring to the period 1840–1907, Fanny Balbuk’s lifetime, Reece and Stannage (Reference Reece and Stannage1984) write that this is, “the most wretched chapter in the history of black–white relations in Western Australian history” (Pickering, Reference Pickering2017, p. 12).

Other Noongar leaders such as Yellagonga and his brother Miago carefully develop good relationships with colonisers, which takes huge restraint on their part, and led to a life of poverty as colonisation progressed. For instance, Lyon writes:

The camp of Yellowgonga, bearing his name, originally stood beside the springs at the West End of the town, as you descend from Mount Eliza; and on this very spot did the 63D pitch their tents when they came to take possession. So that the headquarters of the King of Mooro [aka Perth] are now become the headquarters of the territories of the British King in Western Australia. On this very spot too the King of Mooro, now holds out his hand to beg a crust of bread. (Lyon, Reference Lyon1833)

As Cook (Reference Cook2019) notes, Noongar often live in fear of the police in the days of town camps, as police have the dual role of protectors of Aboriginal people, as well as their prosecutors. Cook (Reference Cook2019) cites Toopy Bodney who remembers that at the time, the police “seemed to prey on Aboriginals” (p. 139).

Access to the City of Perth was prohibited to Aboriginal people between 1927 and 1954Footnote 17 (South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, 2012). Racism, exclusion and hardship is the result of government policies and practices, while hospitals and medical providers reflect the same rationale and worldview. Throughout this period however, Noongar people make their own entertainment in the camps and within the circumstances, make good with their lives. They hold middar (corrobborees), sing around the campfire, tell old stories and maintain Noongar language and culture. There are many beacons of light and Aboriginal stories of resilience are often celebrated today (Haebich, Reference Haebich1992). Having come this far, through Noongar yarns, seasonal wellbeing and colonial happenings, we will now finish our karlup bidi. We are nearly home.

Karlup bidi – Pathways home

In this section is an idea for walking bidi through Kaart Gennunginyup Bo and surrounds, including walking or riding to the riverside and city centre via footpaths (involving crossing roads). See Figures 6 and 7 for illustrative maps of some of the places referred to below. The walks we describe below are unmarked. If you are new to the area, we recommend first using the marked, formal Kings Park trails to grow your familiarity with the place. Check websites such as the Kings Park home pageFootnote 18 , the Kings Park Visitor mapFootnote 19 and the Urban Bushland Council (2025) for updates and walking information.

Figure 6. Map showing the Alternative Bidi; and the Wandaraguttagurrup, Karrgatup and Jualbup homeplaces and key sites without roads.

Figure 7. Map showing the Wandaraguttagurrup, Kaart Gennunginyup Bo and Jualbup homeplace and key sites as part of metropolitan Perth.

We suggest that as you walk or ride, you take the opportunity to reflect on the way things have been over time. You may envision walking trails and camps as you pass sites or views. You may consider the relationship between the past and the present, as there are many connections, once you listen, observe and reflect. Most of the places described below are visible, recognisable and ‘imaginable’ from the various lookouts in Kings Park.

Boodja – Country. Winja – Where?

First, take the bus to Goordandalup , the current site of the University of Western Australia (UWA). Walk or ride along the Perth Waters shoreline. All along this shoreline, into and beyond Perth are Noongar camping places amidst impressive wetland ecosystems. Daisy Bates (Reference Bates1909) describes a tour that she calls “Along the Shore from Crawley”. We use her descriptions with other accounts of Noongar life. Many of these places are greatly modified but still here today, while some are covered by train stations, suburbs, or city infrastructure. Please imagine and envisage, to recreate the past within the present.

We shall begin with the camp close to Goordandalup (the present Crawley). Katamboordup (Gallup’s place) adjoined it, and on the flats and swamps between, with their special names - Goolililup, Burnawarranup, and Beenyup; [where] goonok or jilgees were sought for in their season…

At the foot of Mooro, the point of the Katta or hill—Mt. Eliza-sometimes called Katta Moor, crabs were plentiful, and easily obtained, and many a morning was spent crabbing by women and children while their men kind either loafed at the camp or went opossum or game hunting …. Goouininnup—the site of the former Old Men’s Depot— came next to Mooro, and was the name of the spring that still bubbles up in the vicinity. Beside this spring was the camp of NgalgoongaFootnote 20 and his families—

Ngalgoonga, who stood up in his native dignity to receive the detachment of soldiers… (Bates, Reference Bates1909, p. 16)

The Museum of Perth describes Goonininup as a campsite with a sacred site, being a large permanent spring at the base of Mount Eliza or Kaata Mooro, downstream from where the old Swan Brewery building stands. Goonininup is recognised by Noongar people as located where the ancestral creator, the waugyl, is said to have first risen to the surface before making its way to the sea, creating the present course of the beeliar (Swan River). Noongar people offer customary introductions at waugyl places such as Goonininup, a practice many people continue to do today. To neglect to do so is said to result in illness.Footnote 21

Kooyar (type of frog) provides a rich source of food in seasons, along with crabs the women and children gather. … Noongar yorga (women) use their wanna (digging sticks) to dig the kooyar out from the ground, as these were the best for eating.Footnote 22 Kooyamulyup extends from Goonininup around the shoreline to Goordaandalup , the present location of UWA. Collard and Martin (Reference Collard and Martin2019) explains that Goordaandalup was a ceremonial place for bringing together husbands and wives, prospective in-laws and extended families.

The Museum of Perth account describes the droving of the kangaroos called yonga-a-kabbin, from Kaart Gennunginyup Bo to Goonininup. This event also concludes the annual boys’ initiation programme of learning from Elders. After the hunt, Noongar hold feasts, ritual gift-giving and conduct the making of kangaroo skin cloaks (booka).Footnote 23

Into the hollow … the yongar and warr—male and female kangaroo—were driven, what time the natives assembled together for a yon’gar-a-kaa’been—kangaroo battue. All the residents in the surrounding district helped in this exciting hunt, driving the animals with shouts and yells, from their fastnesses in the hills and slopes of King’s Park, into the hollow which was a veritable cul-de-sac ready made for their reception… Great was the feasting and fighting and skin cloak making afterwards… (Bates, Reference Bates1909, p. 16).

Bates (Reference Bates1909, p. 16) also refers to a site around the shoreline east of what is now UWA, which is:

A favourite place for cranes this place must have been at one time, for the old legend told by the grandfathers runs thus: The wai’en (crane) rested on one leg and sang to the goonok:

“Moordaitch, moordaitch, wat’ gool, wat’ gool; goon’yok, goon’yok, yooal’gool yooal’gool,” (“Hard one, hard one, go away, go away, soft one, soft one, come here, come here.”)

The song is about the crane who watches the freshwater crayfish (goonak or Cherax preissii) during the season that it has a hard shell. The crane asks goonak to replace its hard shell with its soft one so the crane might eat it.

Goodinup is the camping ground which once formed the west end of the Perth Foreshore, adjacent and upriver from Kaart Gennunginyup Bo. Goodinup is also a site of freshwater springs, which flow into a large pool surrounded by jarrah and other gums. Being a permanent freshwater source, the pool supplies considerable quantities of food such as tjilkies and ducks. Many black cockatoos visit this site. Goodinyal in Noongar language means cobbler fish, therefore Goodinup possibly means place of cobbler in the river, a fishing site. Many historic sources comment that Noongar fires light up the riverbank after dark to attract goodinyal into the shallows, to easily spear them, then roast and eat them with family. With plenty of food sources in and around the area, Goodinup is an important camping place for Noongar people.Footnote 24

Walking east from Goodinup, further along the Perth Foreshore, is the fishing site and camping ground of Gumap , a name which suggests a place of urine smell. Located around the present-day Elizabeth Quay, the locality of Gumap extends north up the hill towards St George’s Terrace. The fishing site is situated amongst rushes and salt marshes. Noongar men fish, particularly at night with fires, while yorga (women) and koolangka (children) gather small animals, yurenburt (berries), yams and quandong. Footnote 25

Still walking east along the Perth Foreshore, the general location of the current Langley Park, is Dyeedyallup , where clay and ochre is located.

Gooloogulup is the name of the hill at the western end of St Georges Terrace and the lowlands to the north. Two swamps are here, part of a chain of freshwater lakes and wetlands which - in the long now - provide Noongar people food such as kooyar (frogs), tjilkies (freshwater crayfish), water birds, yakan (turtles) and plant foods like yanget, bulrushes, that thrive in the wetlands. It is likely that the sandy soil ecosystem suits Swamp Banksia and Melaleuca. Melaleuca tree oil is used by Noongar people in Perth for antiseptic requirements.Footnote 26 Soon after colonisation these wetland areas are drained for the railway station.

Yandilup lies east of or under the Perth Train Station. This is a low-lying swamp, which Len Collard translates as meaning ‘the reeds are on and by this place’. Yanjidee is the name of the rhizome root of the reeds, or bulrushes. In the long now, Noongar women use wanna (digging sticks) to gather these roots, during the season of Djeran (April – May). The Museum of Perth record suggests the likelihood of Yandilup being a site for bog iron deposits with high grade red ochre (mirda), which Yellagonga traded.Footnote 27

Alternative b idi

There is also the possibility of walking a modified trail in reverse, beginning at Matagarup (part of Heirisson Island). Thanks very much to the Kings Park and Botanic Gardens staff for this suggestionFootnote 28 . See Figures 6 and 7.

8 KM trail. Start by parking at North Point or catching the bus to Point Fraser.

-

1. Matagarap (Heirisson Island) – Start

(Walk west along the footpath down Riverside Drive)

-

2. Dyeedyallup (Langley Park Area) – 1.0 Km

(Continue west along Riverside Drive to EQ)

-

3. Gumap (Elizabeth Quay Area) – 2.3 Km

(Loop north around the exhibition centre toward to northern end of John Oldhan Park)

-

4. Goodinup (West Perth Foreshore) – 3.6 Km

(Take jacobs ladder up to Kings Park)

-

5. Kaarta Mooro (Mt Eliza) – 4.6 km

(Check step 6 before leaving). (Walk south and down Kokoda steps)

-

6. Goonininup (Foreshore, Crawley) – 5 Km

Because it can be exceptionally busy crossing Mounts Bay Road, it may be best to walk south down Law Walk (not bike friendly) toward Crawley. Sections of this path may look down onto Kooyamulyup, possibly the Dryandra Lookout.

-

7. Kooyamulyup – 7 Km

(Continue toward Crawley steps, walking west until you reach Crawley Avenue, where it is safe to cross Mts Bay Road. From here walk south down Hackett Drive toward Matilda Bay)

-

8. Goordandalup (UWA Area) – 8 Km

This route allows walkers to use Law Walk trail within Kings Park to bypass Mounts Bay Road. If you are riding then use Forrest Drive which runs parallel to Law Walk, as Law Walk is not bicycle friendly.

Conclusion

In this paper we used Noongar onto-epistemologies and present-continuing tense to explore Kaart Gennunginyup Bo’s vital, living boodja which has enduring cultural significance. We answered the question of how environmental educators can help people come to know their localities as “home” in an Aboriginal sense, by “showing how.” Framed by Critical Forest Studies specifically and the Aboriginal environmental humanities more generally, we illustrated cultural, temporal and linguistic dimensions of societal place-care, to produce regenerative narratives about a locality-based sense of “home.” By centring karlup bidi or pathways home, we offered a Noongar way to see home not as a house, but as karlup – as home place. In Kaart Gennunginyup Bo and its hinterland to Derbal Yerrigan and several Perth sites of Noongar importance, we find layered sites that symbolise both colonial disruption and processes and opportunities for renewal. By engaging with these places through basic Noongar language, we encourage readers to walk or ride the karlup bidi – to learn with Noongar concepts in dialogue and reciprocity.

A Noongar worldview offers a reorientation for society towards Land as living Country, knowledge as collaborative, creative, musical, experiential and practical, and language as concepts for a relational worldview of cyclical, seasonal time. In embracing these principles, inhabitants of Whadjuk Boodja can walk together in ways that are regenerative and just.

The journey is ongoing. But each step along the karlup bidi brings us closer to a Noongar sense of place, and closer to the continuing wisdom in Noongar Boodja. Readers are encouraged to download maps and walk Noongar trails. The authors invite inhabitants and visitors to Whadjuk boodja to continue walking these places, as Noongar residents do and have done for thousands of years, remaking connection with the living past as continuing present.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge and thank Luke Clynick and the Park Management Officers of Kings Park and Botanic Gardens, for their advice on and contribution to this paper.

This research results from a “sense of place” project funded by the Queen Elizabeth II Medical Centre (QEIIMC) for its environs and hinterland and implemented by Moodjar Holdings Pty Ltd who worked with the Nulungu Research Institute of the University of Notre Dame Australia to complete the historical/cultural and contemporary interpretation.

Ethical standards

This research was conducted according to the Notre Dame Human Research Ethics Committee guidelines, approval number 2023-062.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper. The authors would like to disclose that Professor Sandra Wooltorton is an Associate Editor of The Australian Journal of Environmental Education (AJEE). In accordance with AJEE protocols, Professor Wooltorton was not involved in the editorial process or decision-making regarding this manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix A

Here is a glossary of key Noongar words, for you to learn as you go

Appendix B

The following websites offer useful resources for readers of this research.

-

https://www.indigenous.gov.au/stories/looking-out-from-kaart-gennunginyup-bo-place This is a visual and voice introduction to Kings Park, including explanation of the meaning of Kaart Gennunginyup bo, by Len Collard. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbRz1GzQbdI

-

https://museum.wa.gov.au/explore/wetlands/aboriginal-context/noongar This is one component of a project called ‘Reimagining Perth’s Lost Wetlands’ by The Western Australian Museum. We recommend a review of the whole site: https://museum.wa.gov.au/explore/wetlands/

-

Kaartdijin Noongar: https://www.noongarculture.org.au/ This is the Noongar Knowledge website, convened by the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council. We advocate all southwest Australians study this website. See: Kaartdijin Noongar

-

Culture and heritage | Kings Park. https://www.bgpa.wa.gov.au/culture-and-heritageThis is an official Kings Park website, directing readers to a range of Noongar-led programmes. You may be interested in the Noongar six seasons programme.

-

Nyoongar calendar | The Bureau of Meteorology. https://www.bom.gov.au/resources/indigenous-weather-knowledge/indigenous-seasonal-calendars/nyoongar-calendar This links to the Bureau of Meteorology Noongar seasons website.

For further information on places within this narrative, please see these websites:

-

Goongoongup: https://www.museumofperth.com.au/goongoongup

-

Weitch-Rutta https://www.museumofperth.com.au/weitchrutta

-

Boojoormelup: https://www.museumofperth.com.au/boojoormelup

-

Goonininup: https://www.museumofperth.com.au/goonininup

-

Kooyamulyup: https://www.museumofperth.com.au/kooyamulyup

-

Gooloogoolup: https://www.museumofperth.com.au/gooloogoolup

Author Biographies

Len Collard is an Adjunct Professor at the Nulungu Research Institute at the University of Notre Dame Australia, an Emeritus Professor at the University of Western Australia, and Director of Moodjar Holdings Pty Ltd, an Indigenous-led cultural education company.

Sandra Wooltorton is a transdisciplinary researcher, Professor and Senior Research Fellow at Nulungu Research Institute, at the University of Notre Dame Australia’s Broome Campus. Sandra lives in Noongar boodja and has an interest in nurturing place-relations as decolonial praxis.

Louisa Stredwick is an Early Career Researcher with ties in both the Kimberley and Tasmania, Australia. She has a special interest in all the ways of mapping and conceptualising place and humans’ existential and storied interdependencies within it.