Personal autonomy – i.e. the ability to make informed, free, uncoerced decisions – constitutes a key aspect of democratic institutions. Developing, supporting, and maintaining autonomy is a central challenge for modern societies, which today are characterized by a growing pressure on people to adapt their behavior considering vastly increasing climate change, health care costs and multicultural diversity in social context. Institutions also restrict personal autonomy by imposing rules and regulations on human conduct (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005). Although restrictions may be necessary for maintaining public safety, health and social order, they do nonetheless undermine personal autonomy, having downstream consequences for people’s experiences of agency and control, including negative arousal, resistance and motivation to act (Brehm and Brehm, Reference Brehm and Brehm1981; Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000; Sheeran et al., Reference Sheeran, Wright, Avishai, Villegas, Rothman and Klein2021). Considering that the experience of agency is essential for health and well-being (Renes and Aarts, Reference Renes, Aarts, de Ridder, Adriaanse and Fujita2017), undermining personal autonomy thus poses major scientific and ethical challenges to the design of policies and regulations on which democratic institutions are built.

Previous research has convincingly shown that people’s experience of agency decreases as stronger choice restrictions are being imposed upon them (Barlas and Obhi, Reference Barlas and Obhi2013; Driessen et al., Reference Driessen, Dirkzwager, Harte and Aarts2023; Akyüz et al., Reference Akyüz, Marien, Stok, Driessen and Aarts2024a). However, it remains unclear whether qualitatively distinct aspects of restrictions in choice and decision making differentially impact the experience of agency. Exploring the impact of different aspects of restrictions can provide a more nuanced understanding of personal autonomy in social context and, in turn, may facilitate an autonomy-supportive design of policies and regulations. In the present study, we aim to address how institutional restrictions of choice impact experiences of agency by drawing upon a functional model of human autonomy (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023) that distinguishes between three core decision-making components underlying human goal-directed behavior: what action to pursue, when to pursue it and how to pursue it.

Previous research has commonly considered autonomy as a one-dimensional construct where restrictions are primarily evaluated in terms of their severity or impact as a result of intervention techniques of behavioral change that are supposed to undermine personal autonomy (e.g., Nuffield Bioethics Council, 2007; Diepeveen et al., Reference Diepeveen, Ling, Suhrcke, Roland and Marteau2013; Griffiths and West, Reference Griffiths and West2015). More recent insights suggest that distinguishing between qualitatively different kinds of autonomy restrictions provides a more comprehensive understanding (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023) proposed that personal autonomy is grounded in three core components of decision-making: which behavioral goal to achieve (what), which moment to execute the behaviour (when) and in which manner to achieve the goal (how). According to this model, autonomy is not only about the presence of choice, but about who determines the what, when and how of behavior. The model proposes that personal autonomy is a direct function of the degree to which individuals can freely decide on each of these three components (see Haggard, Reference Haggard2008, for a neural implementation of these aspects of choice).

In this model of autonomy, removing the freedom to decide on any of these components undermines the overall experience of agency (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). Initial empirical evidence shows that when an external party decides on any of the three components, experiences of agency decreases compared to when all components are self-chosen. Furthermore, restrictions on the what component appear to have a larger detrimental effect on agency experiences than restrictions on the when and how components (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). This may be because the ‘what’ represents the goal of an action (Locke and Latham, Reference Locke and Latham1990; Austin and Vancouver, Reference Austin and Vancouver1996; Aarts and Elliot, Reference Aarts and Elliot2012). Restrictions to the ‘when’ and ‘how’ components are perceived as less of an intrusion, although they still curtail individuals’ flexibility and spontaneity (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). Furthermore, while restrictions on the ‘what’ component have consistently been found to exert the largest negative impact on experiences of agency, the relative effects of ‘how’ and ‘when’ restrictions have shown some variability across studies and individuals (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023).

It is important to note that in previous studies, the external party was another human agent relevant for the situation at hand (e.g., a supervisor at work), thus situating the functional model of autonomy in interpersonal context. Whereas interpersonal processes can be represented in institutional context of autonomy, such as in marriage and families (e.g., Kluwer et al., Reference Kluwer, Karremans, Riedijk and Knee2020), autonomy restrictions that result from policy and regulations speak to a more general context typical for institutions. Institutions structure human interaction through the instigation and maintenance of both formalized constraints and rules as well as more informal behavioral guidelines (North, Reference North1990; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005; Scott, Reference Scott2014). An institution can take different bodies of structure and administration, such as represented in public and private organizations, companies and corporations and local or national governments. Importantly, institutional restrictions can limit one’s ability to freely decide about the ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘how’ components in various daily situations. For example, in the institutional context of a company, the company might determine ‘when’ to have a holiday but not ‘what’ to do, as agreements of work conditions put constraints on vacation dates. Additionally, governmental rules may enforce people to only go to work by public transport (rather than the preferred mode of car transportation), thus signifying that the ‘how’ component is institutionally restricted. Despite that institutions can restrict people in deciding what, when and how to act, it remains an open question whether the functional model of human autonomy tested in interpersonal settings generalizes to institutional contexts.

Current research

The present research reports two studies to extend and further test the functional model of autonomy by investigating how experiences of agency are affected when different kinds of institutional contexts impose restrictions. As an initial test of this idea, in our first experiment we adapted the scenario-based paradigm designed by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023) and examined effects on a measure of experienced agency resulting from institutional restrictions in different domains such as holiday planning, work planning, improving health, organizing social events and grocery shopping during virus quarantine.Footnote 1

In the second experiment, we further extend previous research by considering the role of goal framing as part of the general sense of having freedom. A recent study by Sankaran et al. (Reference Sankaran, Zhang, Aarts and Markopoulos2021) suggests that individuals are less receptive to autonomy restrictions when these restrictions serve a more general purpose that speaks to having personal autonomy over people’s future objectives. Highlighting the importance of achieving one’s final goals as a signal of freedom of choice thus might compensate for the loss of control. In line with this notion, focusing a person’s attention to goals and freedom of choice has been associated with accepting institutional control as part of democratic constitutions (Passini, Reference Passini2017; Holcombe, Reference Holcombe2021). Accordingly, restrictions of personal autonomy are considered to have a weaker impact on the experience of agency if they are compensated or ensured to lead to the achievement of goals that represent freedom of choice in the eye of the autonomy-restricted beholder. We therefore examine whether explicitly highlighting the enjoyment of freedom because of the attainment of a goal moderates the impact of institutional restrictions on experiences of agency.

Experiment 1

In this experiment, we examined institutional restrictions across five behavioral domains. The institution involved in the decision-making process was not specified. Instead, participants were encouraged to think about a specific institutional context they find relevant and that comes to mind first. For example, in the context of the scenario of arranging a holiday, relevant institutions that could restrict decisional freedom that our participants might consider are employers and transportation organizations. By leaving the institutional identity open for interpretation, we aimed to ensure that the effects of restricting the three decision-making components map on the personal understanding of the situation at hand.

Based on earlier findings (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023), we predict that restrictions applied by an institution on decision-making negatively impact agency experiences. Moreover, we expect that experienced agency decreases as the number of restricted decision-making components increases, and that restrictions on the ‘what’ component produce the largest negative effect. Although previous research suggests that the relative effects of ‘how’ and ‘when’ restrictions may vary across contexts and individuals, we did not formulate specific a priori hypotheses as to the ordering of these components across the behavioral domains we used in the current study.

Method

Participants

Our sample size was determined with reference to Study 1 of Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023), who analyzed data of 120 participants and revealed robust effects of the decision-making components (what, when and how) as within-subjects factors. To be on the safe side, we recruited 150 participants. We used the Prolific.co recruitment platform to enlist participants for our study. Inclusion criteria required participants must be native English speakers, aged between 18 and 65 years, and possess an approval rate exceeding 75% on the Prolific platform based on the experiments they participated previously. Individuals reporting any mental health disorder that significantly affected daily functioning were automatically excluded by the platform’s internal filters. The average age of our sample was 34.86 (SD = 12.85). The majority of participants (N = 100, 75%) identified as female, and approximately 75% were British. Each participant received £3.75 for their time. To maintain data confidentiality, participants were assigned random ID codes. The full survey was designed to take approximately 30 minutes to complete.

Design and procedure

The study employed a 2 × 2 × 2 within-subjects design, in which each decision-making component (what, when and how) was either determined by the participant or by an institutional body. The study was administered via an online survey. Following recruitment through the Prolific.co website, participants were directed to the Qualtrics survey platform, where the experiment was hosted. First, participants were informed about the content of the study and asked to provide informed consent. The procedure (used for Experiment 1 and 2) was approved by the Social Sciences Faculty Ethical Review Board of Utrecht University (FETC 20-293).

At the beginning of the survey, participants received an explanation of the what, when and how components of decision-making, along with a concrete example of each. This was followed by a brief description that these decision restrictions might be imposed by external institutions. Participants then completed two practice trials designed to familiarize them with the survey structure. These trials used a scenario (arranging dinner) that was not included in the main experiment.

Participants then proceeded to the main agency judgment task, which was based on a modified version of Zhang and colleagues’ task (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). The task was designed to probe the nuances of agency experiences across diverse institutional contexts. It included 40 trials, divided into five thematic domain blocks: planning a holiday, creating a work plan, enhancing personal health, organizing a social event and implementing Covid-19 safety measures. To prevent a general negative impact of the Covid-19 scenario on the other four autonomy restricted domains, the Covid-19 block was always placed last, while the order of the other blocks was randomized to control for order effects. Brief 30-second breaks were inserted between blocks to reduce participant fatigue.

In each block, participants read a narrative vignette of one domain describing a decision-making scenario from everyday life. These vignettes were crafted to immerse participants in the situation and prompt them to consider the what, when and how aspects of decision-making. To simulate varying degrees of autonomy, participants were informed that each decision component could either be self-determined or determined by an institutional entity that has policies and rules to control people’s behavior. They were encouraged to think about a specific institutional context that came to mind first and they believed to be relevant for the situation at hand. The narratives and content of the what, when and how decision of each domain are presented in the supplementary materials.

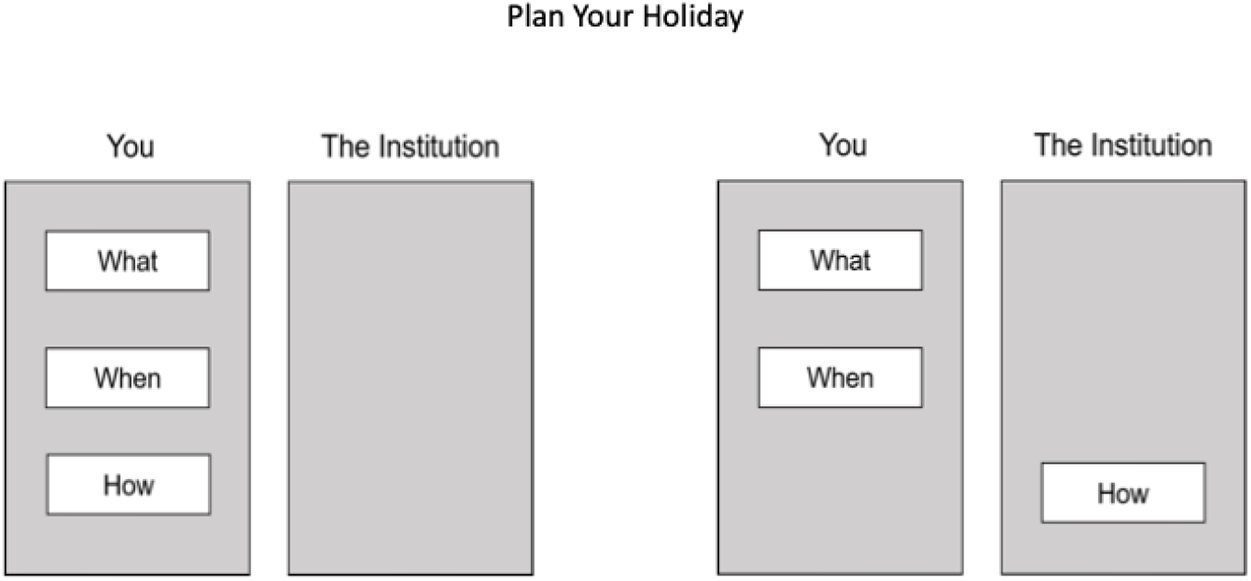

Each participant completed eight agency judgment trials within each block. Across the task, a full factorial combination of all possible permutations of decision control (self vs. institution) was presented. These trials were visually illustrated (see Figure 1) to clearly show who held decision-making authority for each component. We used the same presentation order as Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023) where ‘what’ is at the top, and ‘when’ and ‘how’ below; however, they tested and ruled out the possibility that the presentation order of the three components on the screen contributed to the specific effects of the three components on experienced agency. At the end of the study, participants answered questions related to the five behavioral domains and provided demographic information. Finally, they were thanked, debriefed and redirected to the Prolific website.

Figure 1. Visual representations of two decision-making scenario example trials. On the left, the participant has full control and decides on all three components (what, when, how). On the right, the participant decides on what and when, while the institutional control is directed at the how component.

Measures

For each decision-making agency scenario, participants rated four items that are typical to assess the experience of agency (e.g., Tapal et al., Reference Tapal, Oren, Dar and Eitam2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). These four items, measured on a 7-point Likert scales were: ‘To what extent do you feel that you have freedom of choice in this scenario?’; ‘To what extent do you feel that you have control over the decision-making situation in this scenario?’; ‘To what extent do you feel that your autonomy is restricted in this scenario?’; and ‘To what extent do you feel responsible if you fail to achieve your goal in this scenario?’ Consistent with the earlier study (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023), inter-item correlations between the four items across domains were high (between 0.61 and 0.94), as well as the overall internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93). We combined all four items across the five domains into a single score of experienced agency.

Scenario relevance was assessed at the end of the survey. For every scenario agency trial, participants were asked to rate the personal relevance of the scenario on a 7-point Likert scale (scale ranging from 1 = ‘not at all’ to 7 = ‘highly relevant’). This measure was used to exclude from data analysis trials that did not hold any personal relevance (as judged by a score of 1) to the participant. Furthermore, to assess whether the task was cognitively doable or too simple, scenario difficulty was measured at the end of the agency trials once for each domain (scale ranging from 1 = ‘very easy’ to 7 = ‘very difficult’).

At the end of the experiment, we collected some demographic information. Participants self-reported their age, gender, nationality, level of education and current employment status. This information was collected to provide a comprehensive understanding of the sample composition.

Statistical analysis

In line with Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023), we excluded participants who navigated through the instruction pages unusually quickly – specifically, those who read faster than 2.5 standard deviations below the mean log-transformed reading time (N = 7). However, unlike Zhang et al., we only used general information pages for this calculation, as a technical error prevented us from collecting reading-time data on the scenario-specific instruction pages. We then excluded trials in which participants rated the scenario as not relevant (i.e., relevance score = 1). After this exclusion, 5,464 trials remained, representing 91.1% of all trials.

To estimate the effects of self- vs institution-determined decisions on experienced agency for each component, we fitted a linear mixed-effects model. In this model, experienced agency served as the dependent variable, and the three decision components (what, when, how, each coded as self- vs institution-determined) were included as fixed-effect predictors. Random intercepts were included for participants and behavioral domains.

We used deviation coding for the predictors, allowing the regression coefficients to be interpreted as the average effect of institutional control (relative to the grand mean) across all conditions. Given our large sample size, we also evaluated practical effect sizes by comparing the full model to reduced models that excluded each decision component in turn. This approach allowed us to assess the proportion of variance explained by each component.

Finally, we examined individual-level variation by estimating person-specific slopes for each decision component using random slopes models. All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.3; R Core Team, 2020).

This study was preregistered on Open Science Framework Registries (https://osf.io/beaj8). We initially registered our statistical plan with an ANOVA-based analysis. However, after further consideration of the data structure and theoretical framework, we determined that a linear mixed-effects modeling approach was more appropriate to be able to account for both within and between-subject variability. Anonymized data and analysis scripts are publicly available at: (https://osf.io/q8ewj/)

Results

Descriptive statistics

Participants reported moderate levels of experiences of agency across all scenarios (M = 3.95, SD = 1.74). Scenario relevance was rated as moderately high (M = 5.05, SD = 1.75), indicating that participants found the domains relevant in their daily lives. Scenario difficulty was rated as moderate (M = 3.38, SD = 1.57), suggesting that the tasks were cognitively manageable without being overly simplistic.

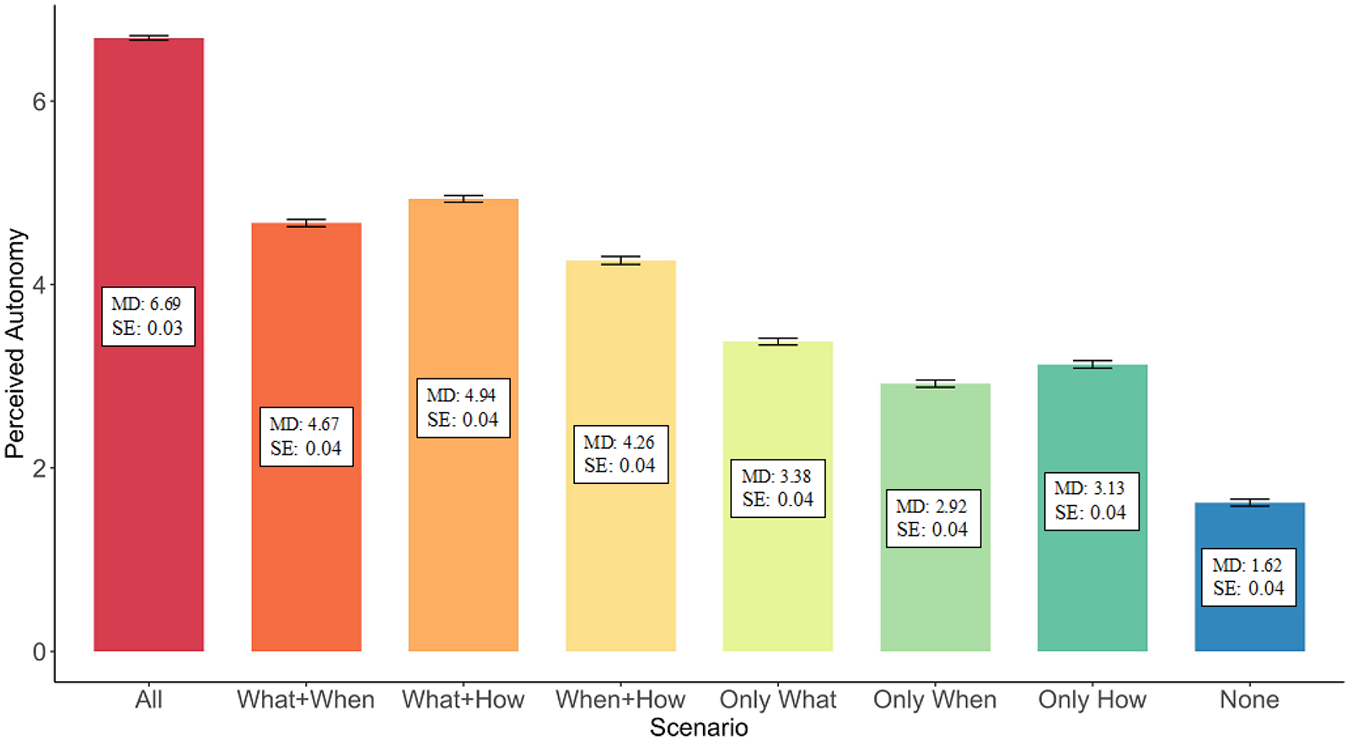

Estimating the effects of the three components and their interactions

We fit a linear mixed-effects model predicting experienced agency, with what, when and how decision components (self- vs. institution-determined) as fixed effects, and random intercepts for participants and domains. The model revealed strong main effects for all three components. (see also Figure 2). The effect estimate was the largest for the ‘what’ component (B what = 1.93, 95% CI = [1.88, 1.98], p < 0.001), followed by the ‘how’ component (B how = 1.61, 95% CI = [1.56, 1.65], p < 0.001) and the ‘when’ component (B when = 1.37, 95% CI = [1.32, 1.42], p < 0.001). These main effects collectively explained a large portion of the variance in experienced agency (marginal R 2 = 0.67).

Figure 2. The average experienced agency scores as a function of who (self vs Institution) determined each decision component (what, when, how). The figure also suggests possible interactions; however, these appear small relative to the main effects. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

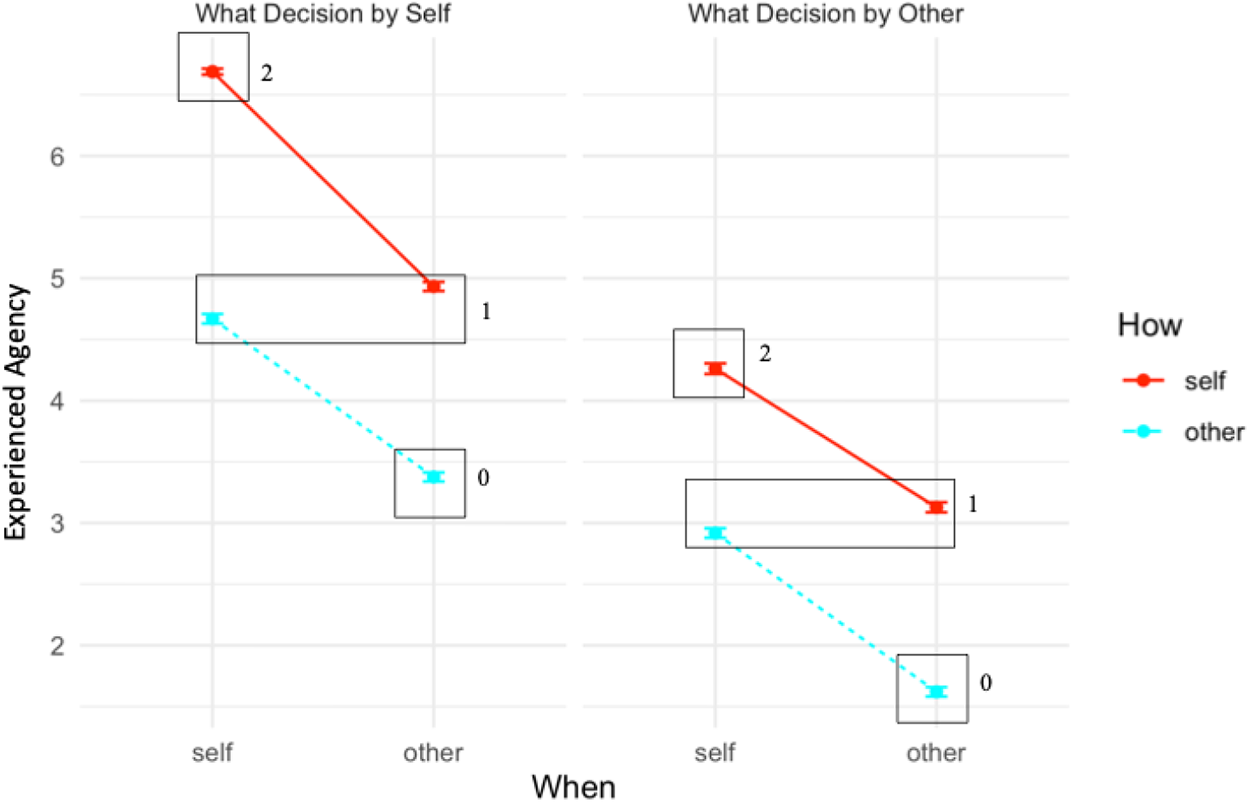

All two-way interactions were significant; between what and when (B what:when = 0.31, 95% CI = [0.21, 0.40], p < 0.001), what and how (B what:how = 0.36, 95% CI = [0.27, 0.46], p < 0.001), and when–how components (B when:how = 0.49, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.24], p = 0.002). There was also a significant three-way interaction between what, when and how components (B what:when:how = 0.63, 95% CI = [0.44, 0.81], p < 0.001). These interactions suggest that experienced agency decreases more steeply when decision control over multiple components is lost simultaneously. As shown in Figure 3, experienced agency drops most notably when going from two self-directed components to one or none.

Figure 3. The differences in experienced agency based on whether the decision is made by oneself or determined by the institutional body, with consistently higher ratings for self-directed decisions across all components.

Comparing the effects of the three components at the individual level

To explore variability in experienced agency under restrictions at the participant level, we estimated person-specific slopes for each component. The linear-mixed model analysis showed that the ‘what’ component had a significantly higher weight than the ‘how’ component (B = 0.33, [CI = 0.25, 0.41], p < 0.0001), and the how component had a significantly higher weight than the ‘when’ component (B = 0.24, 95% [CI = 0.15, 0.32], p < 0.0001).

The differences among the three components accounted for 62.6% of the variance in the person-specific regression weights. However, there was still significant individual variation, which could explain an additional 40.03% of the variance. As indicated by the crossing lines in Figure 4, while the ranking of regression weights applied to the majority of participants, it was nonetheless different for some participants, for example, for whom the ‘when’ component influenced experienced agency the most.

Figure 4. Distributions of person-specific weights of the three components and within-person patterns.

Discussion

Experiment 1 showed that institutional restrictions on all decision-making components significantly reduced experiences of agency. The impact of restrictions on ‘when’ and ‘how’ was less severe compared to ‘what’ restrictions (see also Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023). These effects were consistent across behavioral domains that, on average, were rated to be personally relevant. In short, then, the functional model of human autonomy tested earlier in interpersonal settings seems to generalize to institutional contexts where more general policies and rules dictate what people must do.

Experiment 2

Whereas the findings of Experiment 1 clearly showed that restrictions of the three decision making components on behavior weakens experiences of agency, everyday experiences seem to suggest that such weakening effect can be compensated when attention is shifted to goal pursuit and achievement where freedom of choice can be fully enjoyed. For example, when driving from Amsterdam to Florence, one can picture oneself freely enjoying the wonderful experiences of Tuscany, even after being restricted to reach the final destination by traffic jams and detours. Whereas the impact of such constraints on human behavior might depend on the attributions that people make (e.g., Weiner, Reference Weiner1985); the general notion here is that focusing one’s attention on the final goal that one will achieve can buffer against the negative effects of choice restrictions of behavior.

There is research to suggest that the way people represent or focus on their behavior might matter for choice-restrictions effects on the experiences of agency to ensue. According to action identification theory, behavior is represented at different (action or goal) levels (Vallacher and Wegner, Reference Vallacher and Wegner1987). For example, a person may understand her own behavior of ‘pushing keys and making sound’ as ‘moving fingers’ (action level) or ‘playing a wonderful piece of piano’ (goal level). Behavior is experienced as more intentional and controlled when attention is directed at goals rather than actions (van der Weiden et al., Reference van der Weiden, Ruys and Aarts2013; Antusch et al., Reference Antusch, Aarts and Custers2019). Furthermore, construal-level theory (Trope and Liberman, Reference Trope and Liberman2010) considers psychological distance (e.g., spatial or temporal) to play a key role in how people represent and think about their actions. More distant events are construed at a higher, more abstract level, while closer events are construed at a lower, more concrete level. Furthermore, high-level construals are associated with stronger agency to achieve long-term goals. Accordingly, addressing actions in terms of achieving final goals may lead to high levels of experienced agency, even though the actions might be not self-chosen (Akyüz et al., Reference Akyüz, Marien, Stok, Driessen, de Wit and Aarts2024b). From this psychological perspective, institutional restrictions on human decision-making might impact experiences of agency less strongly when people consider these limitations as part of gaining freedom when achieving goals they value, that is those goals that matter to them in the end. Experiment 2 tested this idea.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. One group received the same scenarios as in Experiment 1, while the second group received versions of the scenarios that included additional information emphasizing that once the goal was achieved, participants would be fully free to enjoy the situation in any way they wished. This manipulation allowed us to test whether framing goal achievement in terms of freedom moderates the psychological impact of institutional restrictions of the three decision-making components on experienced agency.

Method

Participants

Ninety-seven participants completed the online survey on the Qualtrics Survey Software. Two of these participants were excluded because they completed the survey in the preview mode. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical to Experiment 1. The final sample consisted of 95 participants (34 males). This sample size is sufficient to detect small effects of the decision-making components (what, when and how) and goal-framing within-between interactions (assuming f = 0.10 with the following parameters: α = 0.05, power = 0.80, nonsphericity correction ε = 1 and r = 0.5). We collected data from Utrecht University students using SONA (Social and Behavioral Sciences research participation system) and other student groups at the university. All participants were Dutch with a mean age of 27 years (SD = 20.80) and they received 0.5 course credits as compensation.

Design and procedure

The design of Experiment 2 closely mirrored that of Experiment 1, with the addition of a between-subject factor: control condition or goal framing of freedom condition. This goal framing condition explicitly emphasized that once participants achieved their goal under different decision-making constraints, they would be fully free to enjoy the situation as they wished.

Due to the time of running Experiment 2 (in 2022), the Covid-19 scenario was removed from the study, as most Covid-19 measures were no longer in place. Furthermore, because of the specific nature of the sample (students), the workplan scenario was also removed, as this is less relevant to our sample population. The following three domains were used: holiday planning, improving health and organizing a social event. Within these domains, the exact same scenario texts from Experiment 1 were used, with an added information in the goal-framing condition (see Figure 5). The procedure and structure of the survey were largely identical to Experiment 1. The full survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Figure 5. Sample text taken from the ‘organizing a holiday’ scenario for the goal framing group, the additional sentences are shown with bold text.

Measurements

Experienced agency was measured using the same four items as in Experiment 1. Across domains, the items showed strong intercorrelations (R’s ranging from 0.62 to 0.92) and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.93). As in the previous study, the items were averaged across domains into a single index of experienced agency. At the end of the study, scenario relevance and difficulty were measured as in Experiment 1.

Statistical analysis

As in Experiment 1, we excluded data from participants who completed the critical instruction pages unusually quickly (N = 2). We also removed trials in which participants rated the associated behavioral domain as not personally relevant. After applying these two exclusion criteria, 2,192 trials remained (96.1% of the total data).

To assess the effects of the three decision-making components and their interactions on experienced agency and to test whether these effects were moderated by goal framing of future freedom, we constructed a linear mixed-effects model. The model included what, when, how (self vs institution determined) and goal framing (between-subjects) as fixed effects, along with their interactions. Random intercepts were included for both participants and domains. All other analysis procedures followed the same approach as in Experiment 1. The experiment was preregistered on OSF Registries (https://osf.io/2ps8j). Anonymized data and analysis scripts are publicly available at: (https://osf.io/q8ewj/).

Results

Descriptive statistics

In Experiment 2, participants reported moderate levels of experienced agency across all three scenario domains (M = 3.98, SD = 1.72). Scenario relevance was rated as moderately high (M = 4.68, SD = 1.58), indicating that participants found the domains relevant in their daily lives. Scenario difficulty was rated as moderate (M = 3.43, SD = 1.59), suggesting that the tasks were cognitively manageable without being overly simplistic.

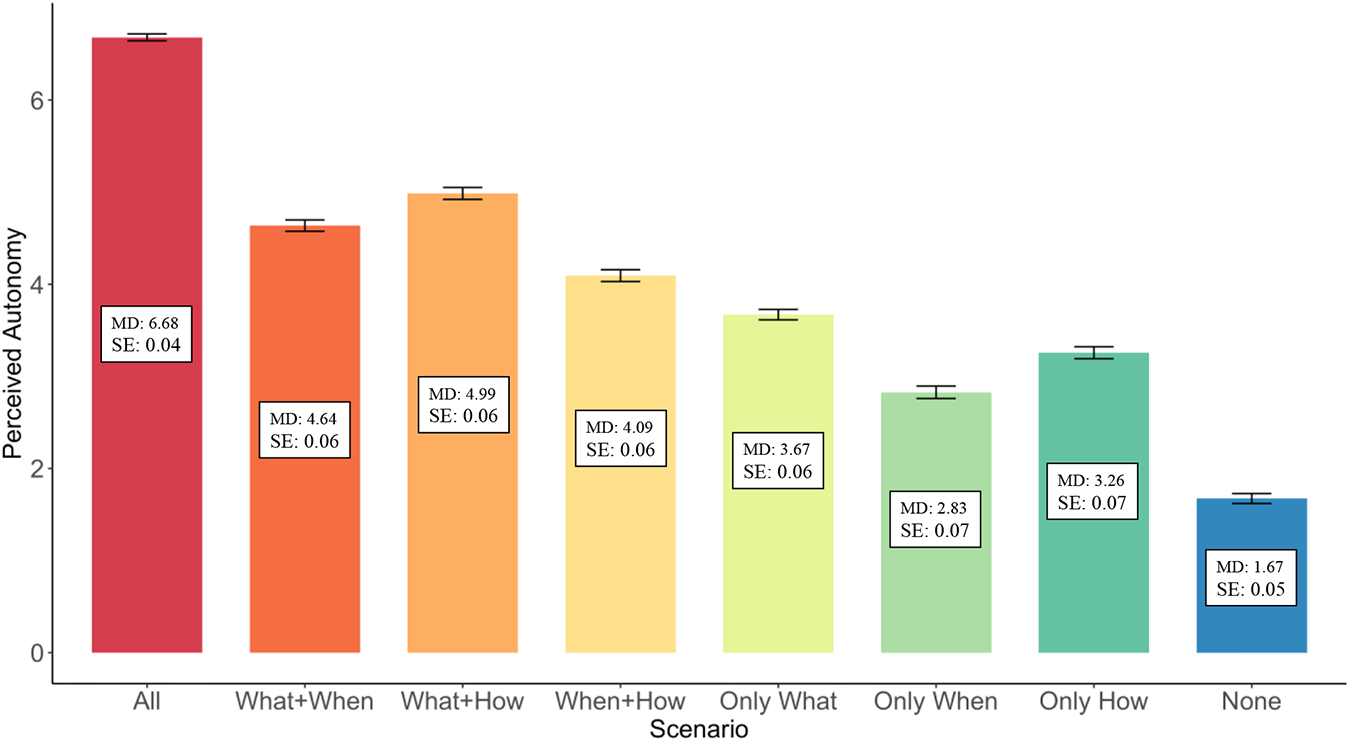

Estimating the effects of the three components, the effect of goal and their interactions

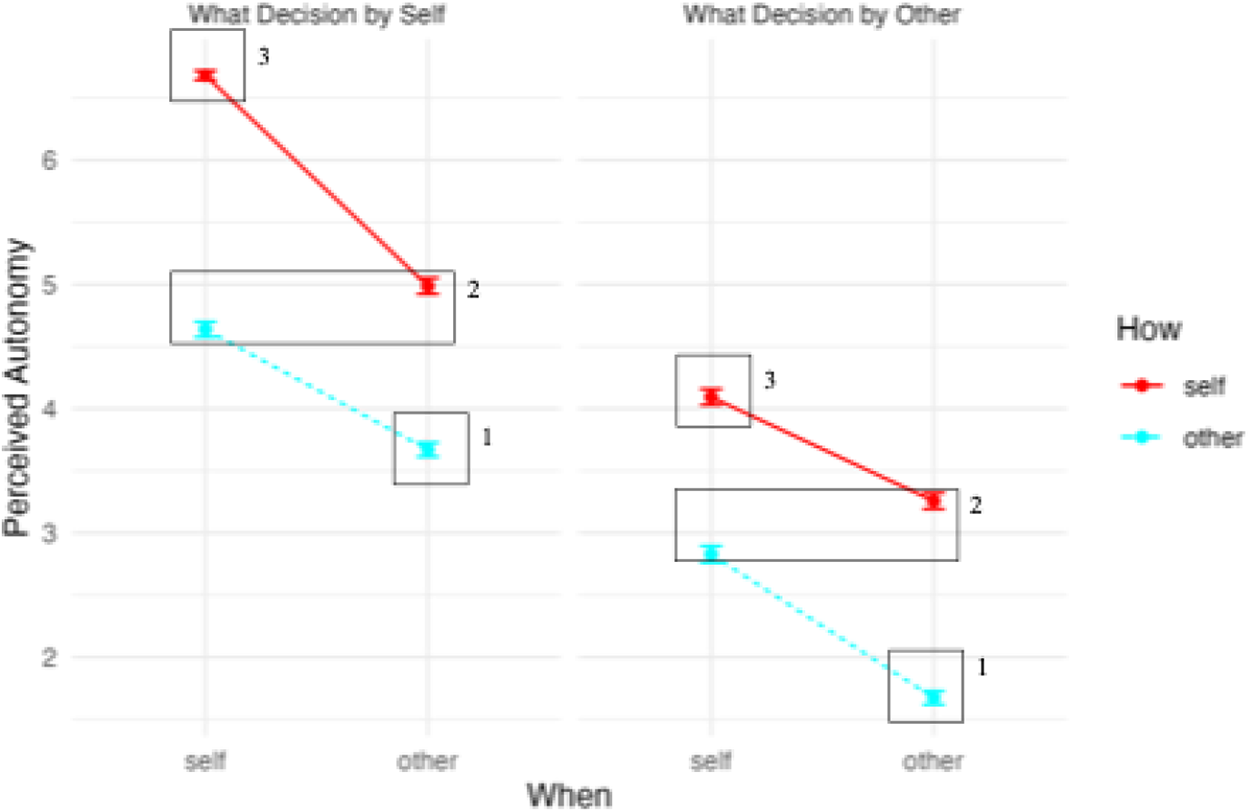

In the second experiment, we introduced ‘goal framing of future freedom’ as a between-subject factor to explore its potential influence on the experience of agency. A linear mixed model was used to estimate the effects of self- vs institution-made decisions for the ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘how’ components, the ‘goal-framing’ factor, as well as their interactions. The analysis revealed a substantial main effect of the decision being made by the participant vs the institution for all three components (see also Figure 6). This effect estimate was the largest for the ‘what’ component (Bwhat = 1.95, 95% CI = [1.85, 2.05], p < 0.001), followed by the ‘how’ component (Bhow = 1.56, 95% CI = [1.46, 1.66], p < 0.001) and the ‘when’ component (Bwhen = 1.20, 95% CI = [1.10, 1.30], p < 0.001). Similar to Experiment 1, the three main effects combined accounted two-thirds of the variance in experience of agency (marginal R 2 = 0.66).

Figure 6. The average experienced agency scores as a function of who (self vs Institution) for determined each decision component (what, when, how). The figure also suggests possible interactions; however, these appear small relative to the main effects. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Furthermore, the results indicated that ‘goal framing’ did not exert a significant impact on the outcome (Bgoal < 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.17, 0.17], p = 0.969). Additionally, the interactions between ‘goal framing’ and the decision-making components were not substantial. Specifically, in comparison to the strong main effects, the interaction between ‘goal framing’ and the ‘what’ component (Bgoal:what = 0.17, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.32], p = 0.025) the interactions with ‘when’ (Bgoal:when = − 0.08, 95% CI = [−0.23, 0.07], p = 0.281) and ‘how’ (Bgoal:how = − 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.16, 0.14], p = 0.886) were marginal to absent. Simple-slopes tests showed that the ‘what’ effect was large in both framing conditions (control: B = 1.95, 95% CI [1.85, 2.05], p < 0.0001, future-freedom: B = 2.12, 95% CI [2.01, 2.24], p < 0.0001). Although the difference between these slopes reached conventional statistical significance (ΔB = 0.171, p = 0.025) its magnitude is very small relative to the size of the simple main effects. These findings suggest that the addition of the ‘goal framing’ factor did not meaningfully alter the previously observed effects of the ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘how’ components on experienced agency.

Comparing the effects of the three components at the individual level

Figure 7 illustrates the person-specific effects of the three components on experienced agency. A linear-mixed model analysis revealed that the ‘what’ component had a significantly greater weight than the ‘how’ component (B = 0.47, 95% CI = [0.34, 0.61], p < 0.0001), and the ‘how’ component, in turn, had a significantly greater weight than the ‘when’ component (B = 0.39, 95% CI = [0.26, 0.53], p < 0.0001). The differences among the three components accounted for 89.9% of the variance in the person-specific regression weights. In contrast, the contribution of individual differences was minimal, explaining 0.04% of the variance, as depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 7. The differences in experienced agency based on whether the decision is made by oneself or determined by the institutional body, with consistently higher ratings for self-directed decisions across all components.

Figure 8. Distributions of person-specific weights of the three components and within-person patterns. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Discussion

Experiment 2 replicated and extended the core findings of Experiment 1. Experienced agency decreased systematically as more decision-making components (what, when and how) were institutionally constrained. Moreover, we established again that institutional restriction of the ‘what’ component had the strongest negative effect on agency experiences. Furthermore, we examined the role of framing goal achievement into freedom as a way to buffer against the negative impact of institutional restrictions on behavior. Contrary to our expectations, goal framing of freedom did not moderate the effects of restrictions on experiences of agency. This suggests that the immediate experience of decision-making autonomy of action is paramount and cannot be easily compensated for by freedom perspectives of goal achievement.

General discussion

Drawing on the functional model of human autonomy proposed and tested by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sankaran and Aarts2023) in interpersonal settings, we investigated how restrictions on different components of decision-making influence experiences of agency within institutional contexts. Across two studies, our findings indicated that participants felt most agentic when they had full control over all decision-making components, and experiences of agency declined as more components were determined by the institutional context. Furthermore, each time a new restriction applied to a component, it significantly reduced experiences of agency, suggesting a cumulative effect of institutionally determined restrictions.

In both studies, the ‘what’ component of decision making had the most pronounced effect on experiences of agency. Choosing ‘what’ to do appears to be most crucial for agentic experience. Considering that the ‘what’ of behavior commonly represents the goal one wants to achieve, this finding underscores the importance of goal selection in experiences of agency, consistent with prior research on volitional action (e.g., Gollwitzer, Reference Gollwitzer1999; Haggard, Reference Haggard2008). Similarly, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) describes autonomy as not simply the freedom to act but the sense that one’s actions are self-endorsed and congruent with one’s values and goals (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000). Within this framework, deciding ‘what’ to do may be particularly important because it aligns most closely with the intrinsic goal selection. On the other hand, decisions about ‘when’ and ‘how’ often relate more to action implementation than intentionality. Even though the moment and manner of action meaningfully contribute to the experience of agency, the ability to decide what to do appears to play the most important role.

In Experiment 2, we further explored whether framing future goal achievement in terms of freedom could buffer against a decrease in experienced agency in the face of institutional restrictions. There is empirical research to suggest that behavior is experienced as more intentional when represented in terms of goal achievement, i.e., when attention is directed at goals rather than actions (van der Weiden et al., Reference van der Weiden, Ruys and Aarts2013; Antusch et al., Reference Antusch, Aarts and Custers2019), and highlighting the importance of achieving one’s final goals as a signal of freedom of choice thus might compensate for the loss of control (Sankaran et al., Reference Sankaran, Zhang, Aarts and Markopoulos2021). However, despite arguing for such compensation effects, the current goal framing manipulation did not mitigate the negative impact of imposed restrictions in the institutional context at hand. Our findings, then, indicate that framing goal achievement in terms of freedom may not be sufficient when immediate restrictions on what, when and how to act are in place and externally controlled.

There are several possible explanations for absence of the moderator effect of goal framing. A straightforward explanation is that the manipulation of goal framing was inadequate. Whereas our instructions were very explicit, a limitation of the present study is that we did not include an empirical check to confirm whether the manipulation of goal framing was successful. Another explanation concerns the use of specific features of the agency judgement scenario task: The task of reporting experienced agency while seeing who is controlling what may have caused participants to focus strongly on the what, when and how aspects, and drew their attention away from the goal achievement and the freedom one will enjoy, thus undermining the impact of the goal framing manipulation effect. While both explanations may speak to the ineffectiveness of the goal-framing manipulation as a result of that the scenarios were not particularly relevant or compelling to participants, they rated the relevance of the scenarios as moderately high.

Apart from methodological concerns, there may be a more theoretical explanation for the absence of the goal framing of freedom moderator effect. Specifically, it might have been the case that, in the present scenario task, the effects of the institutional restrictions of the decision-making components on experiences of agency address a different process than the goal framing effects. Specifically, the what, when and how aspects pertain to the action selection process, while the goal framing of freedom refers to the outcome or attainment of the goal. This notion aligns with models of agentic behavior that link (perceptual and affective) inferential processes of agency to cues of action, and (cognitive) attributional processes of agency to causal understanding of goal achievement (Wegner, Reference Wegner2003; Synofzik et al., Reference Synofzik, Vosgerau and Newen2008; Dogge and Aarts, Reference Dogge, Aarts, Haggard and Eitam2015). While inferences are generally considered to emerge rather quickly and spontaneously without much thought, attributions take more time and conscious processing (Smith and Miller, Reference Smith and Miller1983; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert, Uleman and Bargh1989; Hassin et al., Reference Hassin, Bargh and Uleman2002). Because we did not design our experimental set-up to distinguish between these two processes, we do not know yet whether effects of decision-making constraints of action that are controlled in institutional context can be overruled by goal framing of freedom. Future research could address this further, for instance by encouraging participants to arrive at attributions in response to immediate restrictions on what, when and how to act and to test whether this interacts with focusing them on goal achievement in shaping experiences of agency.

Our findings also have implications for the design of policies and regulations. In today’s fast-changing world that calls for adaptation of human behavior, democratic institutions may struggle with the tension between preserving people’s agentic feelings and restricting them in their choices and behavior (Griffiths and West, Reference Griffiths and West2015; Passini, Reference Passini2017; Holcombe, Reference Holcombe2021). Ethical concerns may cause policy designers and rule makers to resort to softer measures, such as education, persuasion or nudging where people experienced more freedom is choosing their own courses of action. The present findings suggest that directing people’s attention to the freedom they may enjoy once they achieve their goals does not work to compensate for the imposed restrictions either. This insight aligns with broader critiques of behavior change approaches that emphasize individual responsibility without sufficiently modifying the surrounding institutional structures, thereby risking resistance, disengagement, or limited effectiveness (Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2023; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Betsch, Böhm, de Ridder, Drews, Ewert and Mata2025). At the same time, research on public responses to policy indicates that autonomy-threatening restrictions do not inevitably lead to reactance, but that acceptance depends on how constraints are structured, perceived and justified within the broader system (Proudfoot and Kay, Reference Proudfoot and Kay2014). Policy designers and rule makers might thus consider the three distinct components tested in the present study and should be aware of their additive effects that suggest a ‘compensation’ mechanism in itself: When one of the components is restricted, freeing another component can partially make up for the negative effects caused by the first component. For example, when the local government wants to control air pollution traffic congestion in the city center, a strategy might be to reduce freedom by restricting people how they can visit the city (public transport and not private car). This policy will inevitably undermine the citizens’ experienced agency, but this adversity can be partially restored by emphasizing the flexibility in deciding what to do (e.g., shopping, visiting historical buildings or going to theatre or a concert) and when to visit the city (e.g., all day).

Finally, the present study provides a test paradigm that can be easily used to evaluate different scenarios of control within different domains and institutional contexts at issue and to estimate the weights of the components in shaping experiences of agency (and likely resistance). Once the regression weights of what, when and how are known, these numbers provide additional information to priorities policies and rules that target the different components. By considering the trade-off between their weights, ethical concerns, and potential effectiveness in the real world one may have a way to find a balance between freedom and rules to establish institutions that support and structure human interaction in an acceptable way.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2026.10033.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chao Zhang for his support with the data analyses. The studies presented in this report are part of a larger project on the role of choice in the experience of agency in the societal context. The project was funded by a Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Utrecht University awarded to H.M. and M.S., and by Dutch Research Council (NWO) grant, project nr 406.18.GO.047, awarded to H.A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.