Highlights

-

In our population of ALS patients, the 30-day post-gastrostomy mortality rate was 9.3%, and the incidence of major complications was 16.7%.

-

Predictive factors of complications were pre-existing pulmonary disease and hypercapnia.

-

Slow vital capacity was not associated with the occurrence of adverse outcomes.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease affecting the motor neurons, associated with a rapidly progressive course. Mortality rate at 5 years is estimated to be around 80%, Reference Carbó Perseguer, Madejón Seiz, Romero Portales, Martínez Hernández, Mora Pardina and García-Samaniego1 and life expectancy is between 20 and 48 months. Reference Chio, Logroscino and Hardiman2 Throughout the evolution of the disease, the installation of a percutaneous gastrostomy tube is often required to treat severe dysphagia or malnutrition.

Despite the fact that there is no randomized controlled trial on the subject, the benefit of gastrostomy in ALS has been demonstrated in many studies. Reference Miller, Jackson and Kasarskis3–Reference Czell, Bauer, Binek, Schoch and Weber11 This procedure has been suggested to improve nutritional status and weight loss, two important factors for survival and quality of life in ALS. Reference Chio, Logroscino and Hardiman2,Reference Andersen and Abrahams12–Reference López-Gómez, Ballesteros-Pomar and Torres-Torres15 However, gastrostomy insertion carries some mortality risks (between 2% and 25%, Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8,Reference Sulistyo, Abrahao, Freitas, Ritsma and Zinman16–18 depending on the reference, which is higher than for the general population) and some major complications risks (between 2% and 16%). Reference Sulistyo, Abrahao, Freitas, Ritsma and Zinman16 Major complications include peritonitis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, necrotizing fasciitis, pulmonary aspiration and respiratory failure, among others. Reference Sidaner17 Forced vital capacity (FVC) has been identified in some studies as a factor related to complications, particularly respiratory failure and pulmonary aspiration. Reference Chiò, Finocchiaro, Meineri, Bottacchi and Schiffer5,Reference Kasarskis, Scarlata, Hill, Fuller, Stambler and Cedarbaum19,Reference Bokuda, Shimizu and Imamura20

Indeed, there is uncertainty in the current medical literature regarding the optimal timing of the gastrostomy procedure in the course of the disease. The 2020 Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for the Management of ALS Reference Shoesmith, Abrahao and Benstead21 suggest considering the installation of a gastrostomy tube when the FVC approaches 50%, so as to minimize the risk of complications (particularly pulmonary aspiration secondary to procedural sedation). Similarly, several studies and guidelines recommend that it is best to perform the procedure before the FVC becomes lower than 50%, Reference Miller, Jackson and Kasarskis3–Reference Chiò, Finocchiaro, Meineri, Bottacchi and Schiffer5,Reference Andersen and Abrahams12,Reference Desport, Mabrouk, Bouillet, Perna, Preux and Couratier13,Reference Boostani, Olfati and Shamshiri22 whereas some evidence suggests that gastrostomy could be performed safely with lower FVC values, Reference Gregory, Siderowf, Golaszewski and McCluskey6,Reference Dorst, Dupuis and Petri23–Reference Spataro, Ficano, Piccoli and La Bella26 even with FVC values below 30%. Reference Sarfaty, Nefussy, Gross, Shapira, Vaisman and Drory27,Reference Kim, Kang, Suh, Jung, Park and Choi28 This uncertainty in the medical literature is best portrayed by the fact that certain guidelines do not emit a specific recommendation on the optimal moment for this procedure in relation to pulmonary function. Reference Petri, Grehl and Grosskreutz29,30

Objectives

Our main objective was to identify the 30-day mortality rate and the procedural complications of gastrostomy insertion in patients with ALS in our center.

A secondary objective was to evaluate for the presence of any predictive factors of adverse outcomes, particularly regarding pulmonary function. Also, we wished to compare the post-procedural mortality and complications between percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and radiologically inserted gastrostomy (RIG) procedures. Finally, we aimed to describe the survival and weight fluctuations in this population following gastrostomy.

Methods

The medical charts of all patients with ALS who had a gastrostomy procedure at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS) (a tertiary care center in Quebec, Canada) between 2010 and 2023 were reviewed. Patients were excluded if they had a final diagnosis of a disease other than ALS or if they had a surgical gastrostomy performed. We recorded information regarding demographics, comorbidities, disease course, clinical data, biochemical data, respiratory function, details concerning the procedure and subsequent hospitalization, minor complications, major complications and mortality. Complications that were considered “major” included peritonitis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, abscess, gastric wall ischemia, leakage causing pneumoperitoneum, necrotizing fasciitis, pulmonary aspiration, respiratory failure, organ perforation, gastro-colic fistula and any complication requiring re-intervention. Mechanical complications included buried bumper syndrome, tube leakage, hypergranulation tissue, tube obstruction and tube displacement.

To standardize this process, the data collection was performed by the same member of the research team. No other source than the electronic patient record was consulted. The data were then sent for statistical analysis to our biostatistical service, where R Statistical Software (v4.4.1; R Core Team 2024) was used. If particular data were missing, listwise deletion was considered for analysis.

In our center, pulmonary function is measured using slow vital capacity (SVC) for patients suffering from ALS. It is an easier test to perform in patients with bulbar involvement than the FVC. In ALS, lung involvement is usually restrictive rather than obstructive. Furthermore, it has been shown that in patients with restrictive disease, the SVC seems to correlate closely with the FVC. This has been specifically studied as well in the population suffering from ALS. Reference Pinto and de Carvalho31 We have chosen a cutoff of 6 months before the procedure or 3 months after the procedure for the pulmonary function test to be considered valid and included in the statistical analysis. The reason for this choice of a long time-window is addressed in the discussion section. Finally, the decision to perform PEG versus RIG in our center is commonly based on availability at the moment of the procedure.

Statistical Methods

All descriptive data are reported as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile interval] for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. This includes the description of the study population, the 30-day mortality rate and the incidence of complications. To identify predictive factors of complications and mortality, simple logistic regression models were performed when sufficient data were available (n > 8). If this was not the case, either a Wilcoxon rank sum test or a Fisher’s exact test was performed. Considering the small number of events, no multivariable model was performed. The predictive factors examined were all the demographic information, comorbidities, ALS disease course, clinical data, biochemical data, respiratory function and details concerning the procedure (data from Tables 1–3). A threshold of statistical significance of 0.05 was chosen, which is standard. However, data close to statistical significance are mentioned in the text. By performing multiple univariable logistic regressions on a large number of variables, we wished to identify which factors could be associated with increased risk of complications or mortality in our population. Since this is purely exploratory, no multiple testing adjustments were performed. For survival description, a Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed.

Table 1. Sociodemographic information and clinical data

Note: ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS-R = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale – revised; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD = standard deviation.

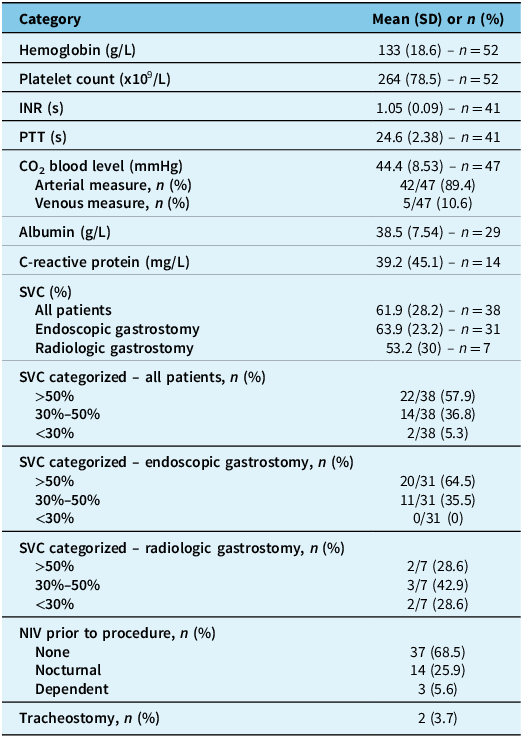

Table 2. Biochemical data and respiratory status

Note: CO2 = carbon dioxide; INR = international normalized ratio; NIV = noninvasive ventilation; PTT = partial thromboplastin time; SD = standard deviation; SVC = slow vital capacity.

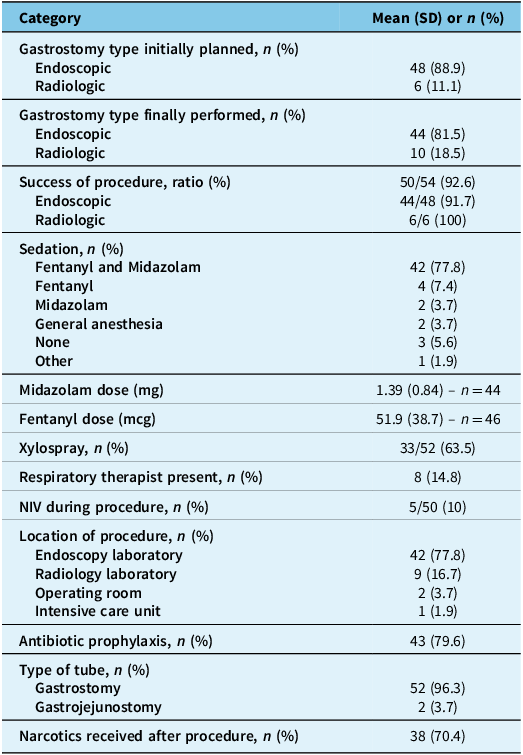

Table 3. Procedural information

Note: NIV = noninvasive ventilation; SD = standard deviation.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations and patient consents

The study protocol (study #2024-5474) was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee and Scientific Committee of the CRCHUS, and informed patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, which consisted solely of medical chart review.

Data availability

Anonymized data not published within this article or other necessary documents such as the study protocol will be made available by request from any qualified investigator. Data will be stored for 10 years following the date of publication of the study results.

Results

Study population

We included 54 patients. Clinical and paraclinical data are described in Tables 1 and 2. The mean age was 63.9 years, with 53.7% female patients. Thirty-eight patients (70.4%) had bulbar-onset ALS. Mean SVC was 61.9% in general, 63.9% in patients undergoing a PEG procedure and 53.2% in patients undergoing a RIG procedure. However, only 38 patients (70.4%) had an SVC measured.

Procedural information regarding the gastrostomy is detailed in Table 3. Of 48 patients initially planned to have a PEG, only 44 patients (81.5%) finally had this procedure, which means that 10 patients (18.5%) underwent the RIG procedure.

Mortality and complications

The 30-day mortality after the procedure was 9.3% (5/54 patients). These results were similar in both types of gastrostomy procedures. Of these five patients, three died from respiratory failure, and two transitioned to palliative care. In total, nine patients received medical assistance in dying. However, none of these occurred in the 30-day period following the gastrostomy procedure.

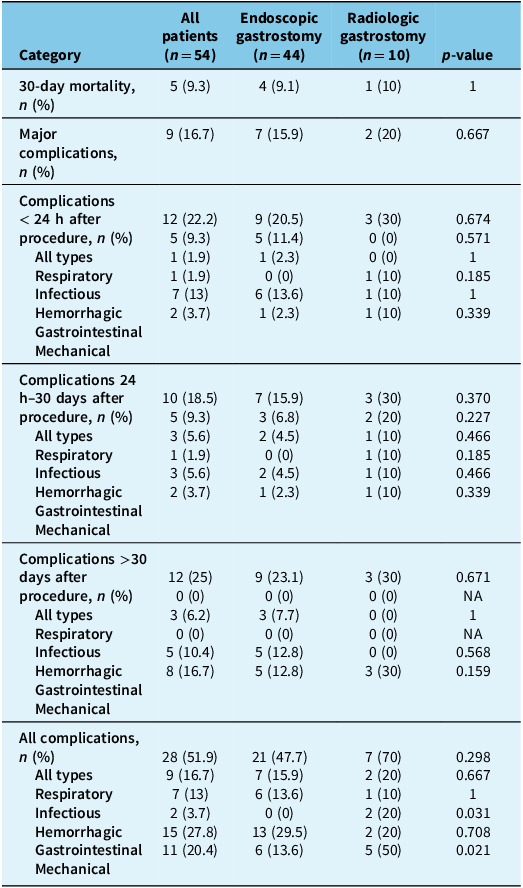

Table 4 details the 30-day mortality rate and the incidence of the different complication categories for both PEG and RIG procedures.

Table 4. Procedural complications and mortality

Major complications following the procedure occurred in nine patients (16.7%). Of these, three patients (5.6%) had respiratory failure, two patients (3.7%) had aspiration pneumonia, one patient (1.9%) had gastric wall ischemia, one patient had tube leakage causing pneumoperitoneum, one patient had gastrointestinal hemorrhage and one patient had an abscess. In total, 28 patients (51.9%) suffered from at least one complication. The different complications that occurred in this study are detailed in Appendix 1.

Predictive factors for adverse outcomes

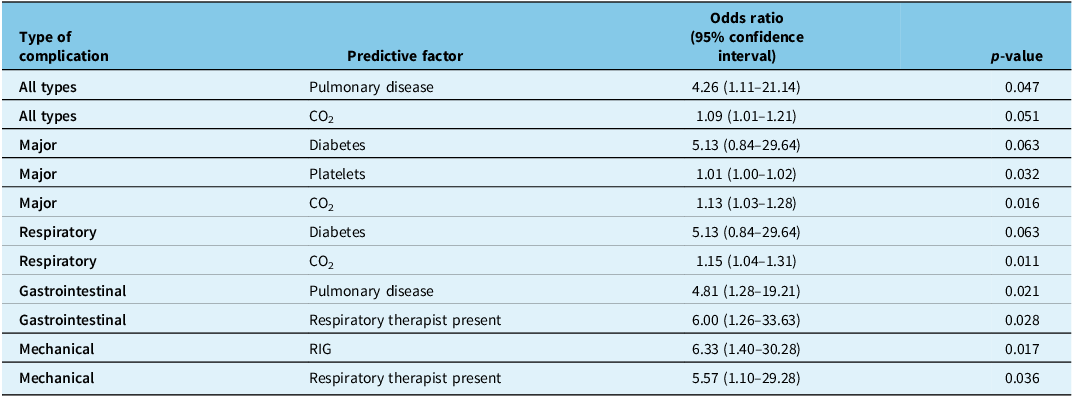

The logistic regression analysis performed to identify any predictive factors of complications is detailed in Appendix 2. Table 5 summarizes only the results of the logistic regression, which seem statistically significant. For all complications, pulmonary disease had an odds ratio of 4.26 (1.11–21.14), and hypercapnia had an odds ratio of 1.09 (1.01–1.21). For major complications, diabetes had an odds ratio of 5.13 (0.84–29.64), thrombocytosis (elevated platelet levels) an odds ratio of 1.01 (1.00–1.02) and hypercapnia an odds ratio of 1.13 (1.03–1.28). For respiratory complications, diabetes had an odds ratio of 5.13 (0.84–29.64), and hypercapnia had an odds ratio of 1.15 (1.04–1.31). For gastrointestinal complications, pulmonary disease had an odds ratio of 4.81 (1.28–19.21), and the presence of a respiratory therapist had an odds ratio of 6.00 (1.26–33.63). Finally, for mechanical complications, RIG had an odds ratio of 6.33 (1.40–30.28), and the presence of a respiratory therapist had an odds ratio of 5.57 (1.10–29.28).

Table 5. Strength of association* with risk factor according to logistic regression analysis for complications following gastrostomy

Note: RIG = radiologically inserted gastrostomy. *Results close to statistical significance (p < 0.05) are also included in the table.

As described previously, logistic regression analysis could not be performed for mortality, infectious complications and hemorrhagic complications, as the numbers were too low. Thus, Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test were conducted to investigate specific predictive factors of such complications, but none yielded statistically significant results (see Appendix 3).

Survival analysis

When including patients receiving medical assistance in dying, the median survival was 1.77 years (95% CI = 1.66–2.08), 1-year survival was 81.05% (71.13–92.30), 2-year survival was 37.47% (25.85–54.30) and 5-year survival was 6.25% (1.72–22.60). When censoring such patients, median survival was 1.91 years (1.66–2.51), 1-year survival was 86.30% (77.31–96.30), 2-year survival was 45.50% (32.70–63.30) and 5-year survival was 13.40% (5.11–35.30). Furthermore, mean weight change at 6 months after the procedure (n = 16/54) was a weight gain of 1.44 kg (SD = 10.3), suggesting that gastrostomy helps to, at the minimum, stabilize weight.

Discussion

In our study, the 30-day mortality rate following gastrostomy is 9.3%, which is in the wide range of 2%–25% described in the literature for ALS patients. Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8,Reference Sulistyo, Abrahao, Freitas, Ritsma and Zinman16–18 As expected, the majority of these deaths (3/5 patients) are from respiratory failure, with the others being from transition to palliative care. Mortality rates are similar between percutaneous endoscopic and radiologically inserted gastrostomy (9.1% vs 10%).

The incidence of major complications is 16.7%, which is also similar to the incidence of 2%–16% described in the literature. Reference Sulistyo, Abrahao, Freitas, Ritsma and Zinman16 This major complication rate is in the upper range of the comparative to the literature. In our opinion, this is explained mostly by the fact that we were very inclusive in our definition of complications being labeled as “major.” Additionally, being a small volume center (54 patients in 13 years) can lead to a higher rate of complications. The most common complications in our study are benign pneumoperitoneum, buried bumper syndrome, tube leakage, respiratory failure, aspiration with or without pneumonia and peristomal cellulitis. In total, 51.9% of patients suffered from at least one complication. These data seem consistent with the literature, although precise values in this particular population seem to vary widely from one reference to the other. For example, one reference suggests that the rate of complications from the “pull” method is 74%, while the rate for the “introducer” method is 47%. Reference Sidaner17 In our center, the former is used for PEG insertion and the latter for the RIG procedure.

In the available literature, there is certain evidence suggesting that RIG is more advantageous than PEG since it requires less sedation and could thus be safer in patients with lower FVC values. Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8,Reference Russ, Phillips, Wilcox and Peter32–Reference Stavroulakis, Walsh, Shaw and McDermott34 This finding is inconsistent as other studies suggest that both procedures are equivalent in terms of safety, regardless of pulmonary function. Reference Desport, Mabrouk, Bouillet, Perna, Preux and Couratier13,18,Reference Allen, Chen and Ajroud-Driss35–Reference Yuan, He, Wang, Kong and Cao37 In our study, complications incidence appears to be slightly higher in the RIG group than the PEG group in terms of major complications (20% vs 15.9%), total complications (70% vs 47.7%), respiratory complications (20% vs 15.9%), hemorrhagic complications (20% vs 0%) and mechanical complications (50% vs 13.6%). This can be explained by the fact that in our center, it is usually the technically more challenging cases or generally sicker patients (e.g., patients with more advanced disease) who are referred to have their gastrostomy in radiology.

In previous studies, certain factors have been associated with a higher risk of complications or mortality following gastrostomy insertion in the ALS population. These include a high C-reactive protein level, Reference Blomberg, Lagergren, Martin, Mattsson and Lagergren38 low albumin, Reference Sidaner17,Reference Blomberg, Lagergren, Martin, Mattsson and Lagergren38,Reference Nunes, Santos, Grunho and Fonseca39 low transferrin, Reference Nunes, Santos, Grunho and Fonseca39 low body mass index, Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8,Reference Nunes, Santos, Grunho and Fonseca39 weight loss before the intervention, Reference Chiò, Finocchiaro, Meineri, Bottacchi and Schiffer5,Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8,Reference Sidaner17 advanced age Reference Chiò, Finocchiaro, Meineri, Bottacchi and Schiffer5,Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8,Reference Sidaner17 and elevated CO2 levels. Reference Bokuda, Shimizu and Imamura20 The FVC has also been identified in some studies as a factor related to complications, particularly respiratory failure and pulmonary aspiration. Reference Chiò, Finocchiaro, Meineri, Bottacchi and Schiffer5,Reference Kasarskis, Scarlata, Hill, Fuller, Stambler and Cedarbaum19,Reference Bokuda, Shimizu and Imamura20,Reference Dorst, Dupuis and Petri23 For example, Pena et al. Reference Pena, Ravasco and Machado40 have shown that FVC < 50% is associated with greater mortality following PEG. However, as Castenheira et al. Reference Castanheira, Swash and De Carvalho8 have shown, this finding is inconsistent from one study to another, with some data suggesting that the procedure is safe in patients with an FVC lower than 50% and even in those with an FVC of less than 30%.

In our study, the following factors are statistically and clinically significant: pulmonary disease and total complications, hypercapnia and major complications and hypercapnia and respiratory complications. Thus, pulmonary disease and hypercapnia seem to be important predictive factors of complications following gastrostomy in patients with ALS. Therefore, these elements should be taken into consideration before the procedure.

SVC was not a significant factor associated with a heightened risk of complications in our study. This suggests that the traditional 50% vital capacity level could be too conservative and should be re-examined in future studies (i.e., there likely is a ventilatory risk level, but perhaps lower than 50%). However, it should be noted that only 38/54 patients (70.4%) had an SVC measured, which could represent a significant bias in our study. It is possible that these patients with missing data would have had lower SVC values (rapidly progressing ALS or more advanced bulbar involvement limiting pulmonary function tests). It is possible that only an arterial blood gas was performed for these patients. Thus, they were not included in the logistic regression for SVC but could have been included in the logistic regression for CO2 levels, which could explain why the latter was identified as a predictive factor and not the former. This bias is an important one to keep in mind when interpreting the results of this study.

Furthermore, the following factors are clinically significant and are close to statistical significance: hypercapnia and total complications, diabetes and major complications and diabetes and respiratory complications. As described above, hypercapnia does seem to be a predictive factor for complications. In addition, although not statistically significant, there is a signal for diabetes as a predictive factor for complications.

The following factors were of statistical significance, but of uncertain clinical significance: platelet count and major complications, pulmonary disease and gastrointestinal complications, presence of a respiratory therapist during the procedure and gastrointestinal complications, RIG and mechanical complications and presence of a respiratory therapist and mechanical complications. The association for platelet count was minimal (OR = 1.01), which undermines its relevance. Although the clinical relation between pulmonary disease and gastrointestinal complications is unclear, pulmonary disease was shown to be a factor associated with all complications following gastrostomy in our study population. Regarding the presence of a respiratory therapist for the procedure, this could be understood as a surrogate for the patient having a more severe disease or comorbidities that heighten the risks of the procedure. Finally, as stated earlier, it is the more technically challenging cases that are referred to radiology in our center. This could explain the association between this type of gastrostomy and the occurrence of mechanical complications.

Finally, median survival (where T0 = time of diagnosis) was calculated to be 1.77 years when including patients having received medical assistance in dying and 1.91 years when censoring such patients. This is similar to what has been described in the literature, where life expectancy with ALS is said to be between 20 and 48 months. Reference Chio, Logroscino and Hardiman2 We have chosen to demonstrate survival both including and censoring patients having received medical assistance in dying because it represents real-world data.

Finally, our study has several limitations to consider. First of all, the retrospective nature of this study is a limitation inherent to its design, compared to a prospective trial. Consequently, certain patients were eventually lost to follow-up, so their outcomes are unknown. Although such patients were censored from survival analysis, missed adverse events could have an impact on the results, notably underestimating mortality rates and incidence of complications, as well as affecting the reliability of the logistic regression on predictive factors of such complications. This is particularly important with regard to the SVC, where missing information could represent more severe ALS, such as advanced bulbar or pulmonary disease. Another bias concerning the SVC is the time between the pulmonary function test and the gastrostomy procedure, which could be unreliable if there is a significant delay between both. As previously mentioned, we chose a cutoff of 6 months before the procedure or 3 months after the procedure for the pulmonary function test to be considered valid and included in the statistical analysis. This is a large time-window and could represent a source of bias as the actual SVC value at the time of the procedure could actually be different from the one measured at the time that the pulmonary function test was initially performed. The reason for this choice of a long time-window was to include as many patients as possible in this analysis (since already only 70.4% of patients had an SVC measure available), although we understand that it introduces another significant source of bias. Another bias that impacts the power of our study is the small sample size of our population (n = 54). Finally, the logistic regression performed on a wide variety of elements could be considered a form of “data dredging.” However, this was included in the protocol from the beginning of the study and is necessary to achieve our objectives. Moreover, positive results are interpreted critically to confirm their clinical relevance. Furthermore, we believe that our results are comparable to the literature, so they can be generalized to the bigger population.

Conclusion

In our study population, the 30-day mortality rate following gastrostomy in patients with ALS was 9.3% (5/54 patients), and the incidence of major complications following the procedure was 16.7% (9/54 patients).

Identified predictive factors of complications following gastrostomy that are statistically significant and appear to be most clinically significant are pulmonary disease and blood CO2 levels. There was a signal, although not statistically significant, for diabetes as a predictive factor. The SVC was not a predictive factor of complications in our study population, although only 70% of patients had a measure of SVC, which introduces a significant bias.

The results of our study provide additional evidence that the traditional 50% vital capacity level could be too conservative and should be re-examined (there likely is a ventilatory risk level, but perhaps lower than 50%). Further studies should be pursued in order to verify this suggestion and identify a clearer cutoff. Furthermore, precautions should certainly be taken in patients with reduced pulmonary function to limit the occurrence of complications such as minimizing sedation, providing noninvasive ventilation as required during the procedure and having a respiratory therapist present.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10510.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the biostatistical department of the CRCHUS, in particular Mr. Samuel Lemaire-Paquette, for their contribution to the statistical analysis of the study results.

Author contributions

JSD: Data collection, methodology, data analysis, manuscript writing. MPB: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, manuscript editing and revision. JS: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection. ELT: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, manuscript editing and revision.

Funding statement

The authors have no funding to report.

Competing interests

ELT has received consulting fees from Alexion for work on an advisory committee concerning myasthenia gravis, as well as honoraria from Pfizer for a presentation on familial amyloidosis.

MPB has received honoraria from Regeneron for a presentation on dupilumab in eosinophilic oesophagitis, as well as from AbbVie for consultation on inflammatory bowel disease and patient needs.

Authors JSD and JS have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Target article

Mortality and Complications of Percutaneous Gastrostomy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients

Related commentaries (1)

Reviewer Comment on Dallaire et al. “Mortality and Complications of Percutaneous Gastrostomy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients”