Introduction

Globally, unhealthy diets and other modifiable health behaviours contribute to the burden of non-communicable disease(Reference Afshin, Sur, Fay, Cornaby, Ferrara and Salama1). While systems level approaches are needed to promote healthful behaviours and diets, effective health and nutrition communication also play a crucial role(Reference Rimal and Lapinski2). In recent years, strategic health and nutrition communication have both been identified as key priorities for improving health behaviours and outcomes, with authoritative organisations including the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasising their importance(3–Reference Silva, Araújo, Lopes and Ray5). Within health communication, awareness raising, which aims to make people conscious of a health issue, risk or behaviour, is considered an important first step towards behaviour change(3).

A range of challenges for health and nutrition communication for public health exist. Firstly, many people are exposed to advertising of unhealthy products including alcohol and discretionary and fast foods(Reference Nieto, Jáuregui, Contreras-Manzano, Potvin Kent, Sacks and White6,Reference Ireland, Bunn, Reith, Philpott, Capewell and Boyland7) . Commercial actors, including producers of discretionary foods, often have large advertising budgets and use sophisticated marketing techniques(Reference Kickbusch, Allen and Franz8). As a result, public health and nutrition messaging struggles to compete in visibility and persuasive impact, making it harder to encourage healthy choices(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9). Secondly, health and nutrition misinformation are widespread, which can lead to an inaccurate understanding of important health and nutrition concepts(Reference Denniss, Lindberg and McNaughton10,Reference Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez11) . Misinformation has contributed to an erosion of trust in science and health organisations, institutions and experts, meaning that people are less likely to follow health advice from these sources(Reference Denniss and Lindberg12). In particular, the erosion of public trust in nutrition science has been highlighted as a major challenge for public health nutrition(Reference Penders, Wolters, Feskens, Brouns, Huber and Maeckelberghe13,Reference Penders14) . In addition, exposure to conflicting nutrition information in the media is associated with confusion about nutrition(Reference Clark, Nagler and Niederdeppe15–Reference Vijaykumar, McNeill and Simpson17). Such nutrition confusion is in turn associated with backlash and negative views towards nutrition science, which is linked to lower intakes of fruit and vegetables(Reference Clark, Nagler and Niederdeppe15–Reference Vijaykumar, McNeill and Simpson17). Thirdly, many individuals have limited health, nutrition and food literacy, with those experiencing greater disadvantage more likely to have limited literacy(Reference Silva, Araújo, Lopes and Ray5,Reference Coughlin, Vernon, Hatzigeorgiou and George18,19) . Low health literacy is associated with poor health outcomes and poor use of healthcare services(Reference Berkman, Sheridan, Donahue, Halpern and Crotty20), and similarly, low nutrition literacy is associated with unhealthy dietary patterns(Reference Taylor, Sullivan, Ellerbeck, Gajewski and Gibbs21). Furthermore, research has shown that low health literacy strongly predicts susceptibility to misinformation(Reference Scherer, McPhetres, Pennycook, Kempe, Allen and Knoepke22), and individuals with low food literacy also have low levels of scepticism toward food advertising(Reference Scheiber, Karmasin and Diehl23).

Considering these challenges and the burden of preventable non-communicable disease, it is important that public health and nutrition messaging is accepted (understood and believed) and persuasive (inducive of a change in attitudes, beliefs, emotions or behaviours)(Reference Epton, Harris, Kane, van Koningsbruggen and Sheeran24,Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West25) . Acceptance of a message is vital to it being persuasive and health and nutrition messages do not always result in acceptance or persuasion(Reference Epton, Harris, Kane, van Koningsbruggen and Sheeran24). Messages must be designed and disseminated in ways that are likely to be persuasive. The characteristics of messages such as their style, wording, framing, length, tone and visual elements, and how messages are delivered, including communication channels and messengers can impact acceptance and persuasiveness. As such, it is important to understand the evidence and best practice approaches for developing and disseminating persuasive messages to inform health and nutrition communication efforts.

There are extant reviews in the literature that synthesise evidence regarding specific and narrow facets of health or nutrition messaging (for example, gain versus loss framing)(Reference Akl, Oxman, Herrin, Vist, Terrenato and Sperati26,Reference Gallagher and Updegraff27) . However, to the knowledge of the authors, no review has comprehensively synthesised evidence regarding the development and characteristics of persuasive messages for raising awareness about health and nutrition issues. Therefore, the aim of this review was to systematically identify best practice recommendations and evidence for the development and characteristics of persuasive health and nutrition messages for awareness raising among adults. Findings from this review will contribute to the establishment of a communication framework to guide nutrition messaging for awareness raising in Australia.

Methods

This study used rapid review methodology to systematically review relevant literature. Rapid reviews follow the same process as systematic reviews; however, one or more steps is removed or simplified to expedite the process(Reference Hamel, Michaud, Thuku, Skidmore, Stevens and Nussbaumer-Streit28). To manage time constraints, this review deviated from standard Cochrane review methodology in the following ways: only review articles and grey literature reports published in English were eligible, grey literature search results were screened by one author only, data extraction was completed by one author only, and risk of bias was not assessed. An extension of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines is currently being developed to provide reporting requirements for rapid reviews and is not yet available(Reference Stevens, Garritty, Hersi and Moher29,Reference Stevens, Hersi, Garritty, Hartling, Shea and Stewart30) . In line with current advice for rapid reviews, the PRISMA checklist has been used (Supplementary File 1) and modifications to systematic review methodology are highlighted(Reference Stevens, Hersi, Garritty, Hartling, Shea and Stewart30,Reference King, Stevens, Nussbaumer-Streit, Kamel and Garritty31) . The protocol was registered with PROSPERO: CRD42024558146 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID = 558146) in June 2024.

Eligibility criteria

Academic review articles of any kind (for example, meta-analyses, systematic reviews and scoping reviews), as defined by Grant and Booth(Reference Grant and Booth32), and grey literature reports were eligible for inclusion. To be eligible, reviews must have either synthesised evidence or made recommendations about best practices for (i) the development (for example, audience segmentation, formative research, channels) or (ii) characteristics (for example, length, framing, tone) of persuasive health or nutrition messaging for awareness raising (see Table 1 for definitions). Grey literature reports that proposed communication frameworks or toolkits aimed at health or nutrition awareness raising were also eligible. Review articles and reports had to be focused on nutrition or general health communication aimed at the general population aged 18–65 years, written in English, peer-reviewed (in the case of review articles) and published since 2010. Studies and reports that focused on general health messaging were included to ensure a comprehensive synthesis of relevant evidence, given the extensive body of academic and grey literature in health communication and public health that offers valuable insights into persuasive messaging strategies that have relevance to nutrition (for example, prevention behaviours). Reviews and reports that focused on communicating about specific health conditions, behaviour change or were for expert audiences were ineligible. Grey literature reports that did not have global scope or focused on regions that did not include Australia were excluded.

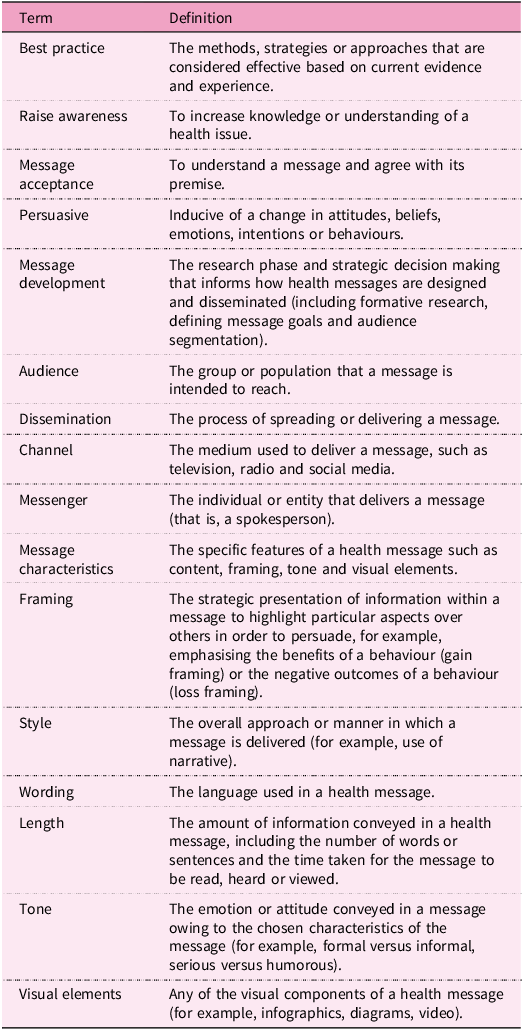

Table 1. Definitions of terminology relevant to the rapid review

Information sources, search strategy and selection process

Four academic databases, MEDLINE Complete (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Global Health (EBSCOhost) and Embase (Ovid), were systematically searched individually on 14 June 2024. The search strategy consisted of terms related to five concepts: health/nutrition; AND communication intervention type; AND best practice; AND review; AND messaging (Supplementary File 2). Relevant subject headings were included, and searches were conducted on titles and abstracts. The search strategy was chosen after consultation with a librarian and extensive testing using a list of articles that met the eligibility criteria. Search results were uploaded to Endnote (version 21·2, Clarivate), then imported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation) where duplicates were automatically excluded. Title and abstract screening were done independently in Covidence by two authors (E.D. and P.M.) and disagreements were discussed until consensus between the two screeners was reached.

Grey literature searches were conducted using the search function on the websites of health organisations in April–July 2024. A list of relevant international and Australian public health/nutrition organisations (for example, the WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization and Australian Government health agencies) to search was determined a priori by the authors on the basis of their experience and knowledge of the field (Supplementary File 2). Four searches were conducted on each organisation’s website: ‘communication framework’, ‘communication toolkit’, ‘message framework’ and ‘message toolkit’. The searches were conducted by the lead author, or a research assistant, and resources were screened for inclusion at the time of searching. When searches generated many results, a minimum of the first 100 results were screened, and screening was stopped when the relevance of search results diminished. If it was unclear whether a report met the eligibility criteria, it was saved for discussion by E.D. and P.M. to determine eligibility. The approach to grey literature searching and screening was developed in collaboration with a health research librarian.

Data collection process, data items and synthesis methods

A data extraction template informed by the review aims was developed in Microsoft Excel (version 2407). Data extraction was completed by one author (E.D.), and if any component of an included review or report was unclear it was discussed with the senior author (P.M.) before data were extracted. The following data were extracted where relevant: review details (aims, review type, date of publication, number of included studies, study design), report details (organisation, type of report, global/regional/Australia), target audience, message topic, message medium (for example, written, verbal), focus of recommendations or evidence, that is, development (for example, audience segmentation, message testing, dissemination), characteristics (for example, framing, length, tone) and communication outcomes. Some eligible records also provided evidence for communication aimed at behaviour change, when this occurred only data relevant to awareness raising were extracted (for example, only data relevant to the impact of messaging on facets of awareness raising such as message acceptance, knowledge or understanding were extracted). Owing to the predominantly qualitative nature of the recommendations and evidence, data were synthesised narratively. Reviews were grouped for synthesis according to the type of evidence or recommendations provided: audience segmentation, formative research, dissemination (channels, messengers) and message characteristics (framing, style, wording, length, tone and visual elements). The number of included reviews and reports that provided each type of evidence, and the level of consistency between the evidence, was then described. All included reviews and grey literature reports were equally weighted in data synthesis and conclusions drawn.

Results

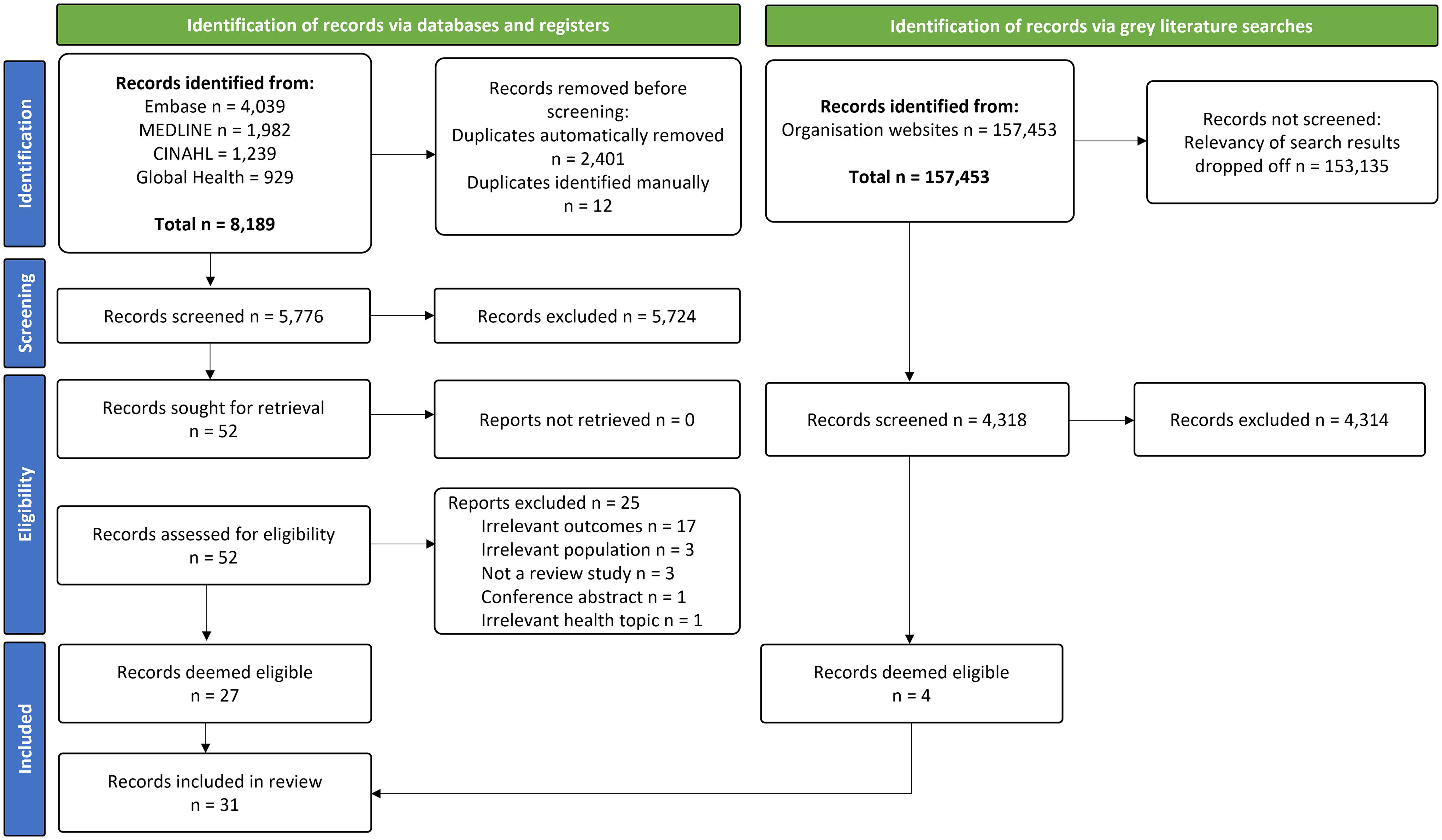

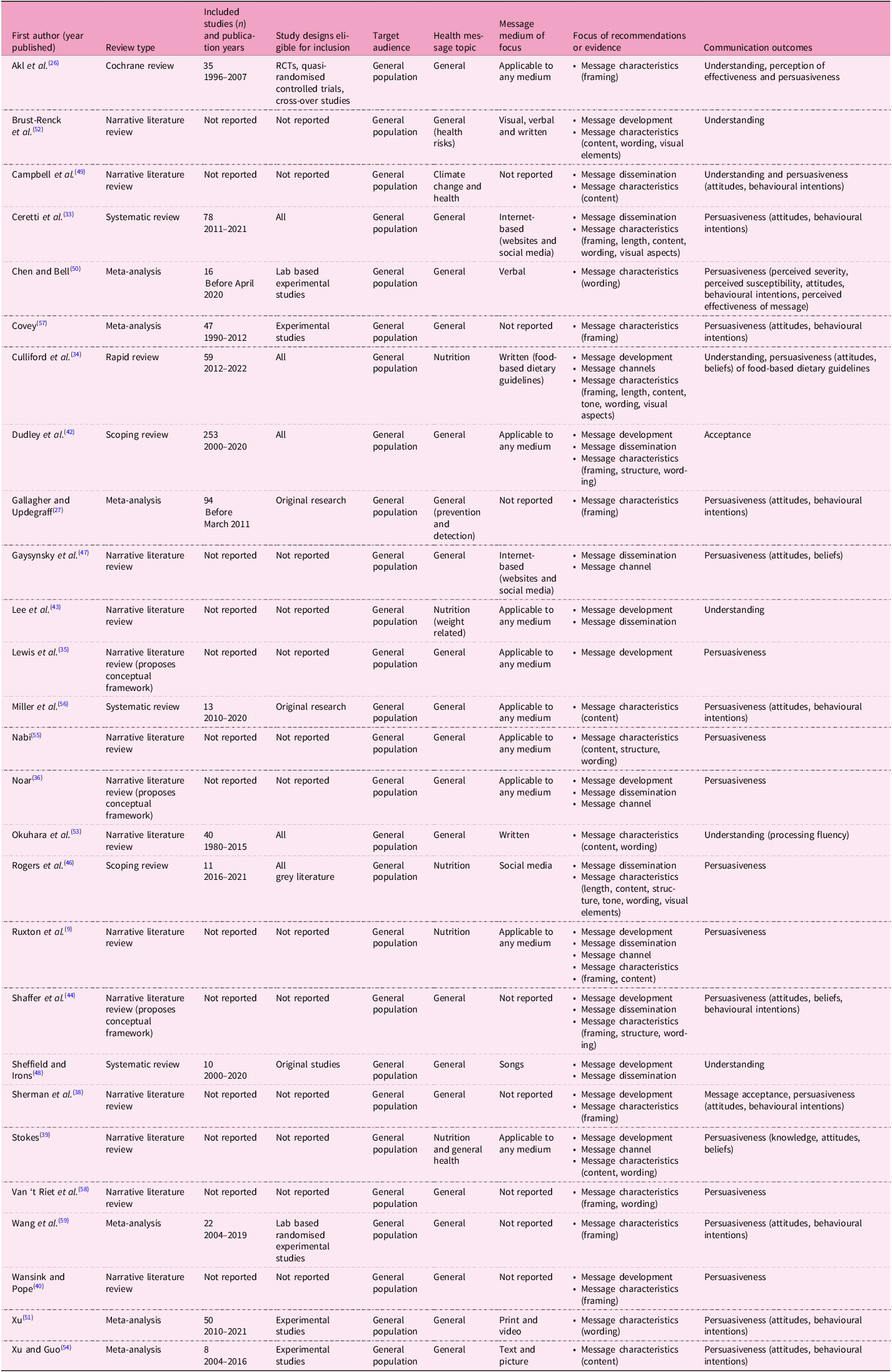

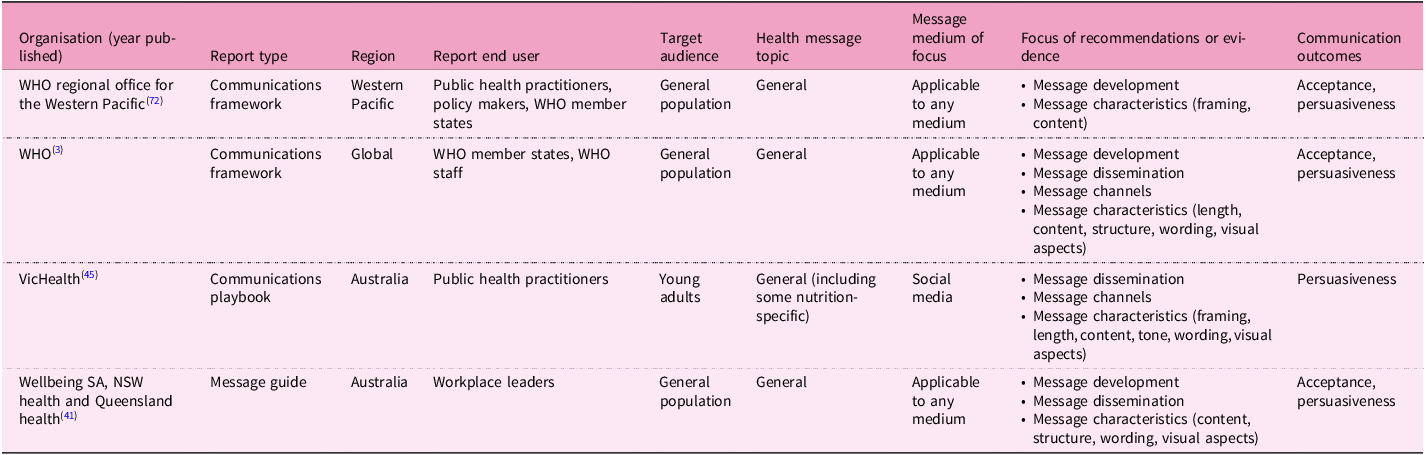

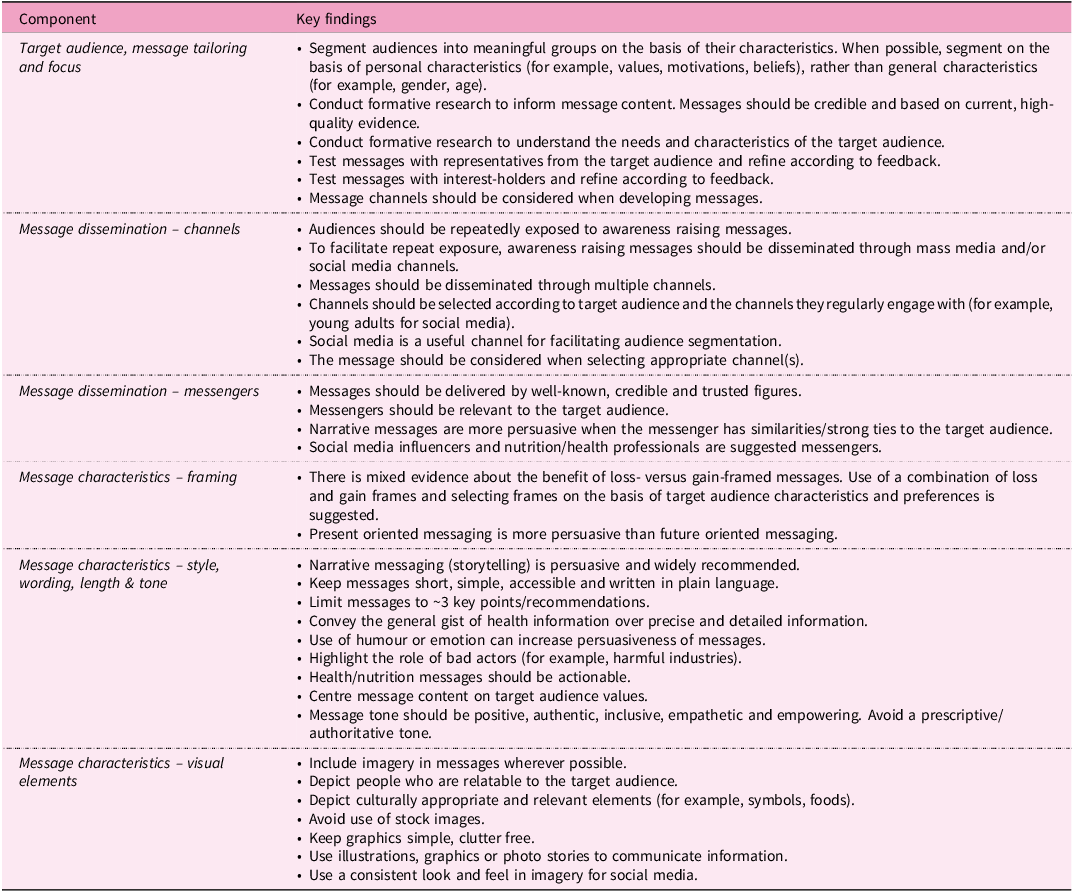

Twenty-seven reviews published in academic journals and four reports published in grey literature between 2010 and 2024 were included (Fig. 1). Characteristics of included reviews are presented in Table 2 and reports in Table 3. From the twenty-seven reviews, fourteen (51·9%) were narrative reviews (three proposed communication frameworks), seven (25·9%) were systematic reviews with meta-analyses, three (11·1%) were systematic reviews without meta-analyses, three (11·1%) were scoping reviews and one (3·7%) was a rapid review. Of the four reports, there were two (50%) communication frameworks, one (25%) message guide and one (25%) communication playbook. Fourteen reviews reported on the number of included studies, with a median of 37·5 (± 43) and a total of 736 studies. From the thirty-one records included, twenty-two reviews and four reports (83·9%) were focused on general health messaging, and five (16·1%) on nutrition-specific messaging. A summary of the recommendations and evidence synthesised is provided in Table 4.

Fig 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram(Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow73).

Table 2. Summary of characteristics of included review articles

N/A, not applicable; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

See Table 1 for relevant definitions.

Table 3. Summary of characteristics of included reports

NSW, New South Wales; SA, South Australia; WHO, World Health Organization.

See Table 1 for relevant definitions.

Table 4. Synthesis of best practice recommendations and evidence for persuasive health and nutrition messages for awareness raising

Evidence and recommendations regarding audiences, message tailoring and focus

Ten reviews and three reports provided evidence and recommendations about defining target audiences. There was consistent support for segmenting audiences into meaningful groups on the basis of their characteristics, such as demographics, values or motivations, then tailoring messages accordingly to increase persuasiveness(3,Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Ceretti, Covolo, Cappellini, Nanni, Sorosina and Beatini33–Reference Lee, Tan, Siri, Newel, Gong and Proust43) . Sherman et al. (Reference Sherman, Uskul and Updegraff38) acknowledged that there is a growing body of evidence indicating that message tailoring is most persuasive when audiences are segmented on the basis of characteristics such as values, attitudes and motivations, compared with more general characteristics such as age or gender. Similarly, one report recommended developing messages that centre on the target audience’s values(41).

Included records also discussed the need for formative research to inform message development. It was recommended that message content should be credible and informed by scientific evidence(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Noar36,37) . The need for formative research to understand the target audience, for example, their knowledge and attitudes, was highlighted in WHO reports as important for informing the design and tailoring of messages(3,37) . There was also consistent support for messages to be tested with relevant interest-holders and the target audience and refined on the basis of feedback(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,Reference Noar36,37,Reference Dudley, Squires, Petroske, Dawson and Brewer42,Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher44) . Overall, the included resources indicated that an audience-centred approach is best practice when developing health and nutrition messages and tailored messages are most persuasive. However, it was also acknowledged that general messages for broad audiences are also required in some instances (for example, on website home pages)(41).

Evidence and recommendations for message channels and dissemination

Communication channels were discussed in seven reviews and two reports. The WHO(3) emphasised the importance of repeat exposure for raising awareness and recommended the use of mass and social media channels to facilitate repeat exposure. Evidence synthesised in narrative reviews and frameworks demonstrated that dissemination of health and nutrition messages through multiple channels increases the likelihood of repeat exposure and is more effective than the use of one channel(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Noar36,Reference Stokes39) . Included records discussed the importance of selecting appropriate channels and recommended they are chosen on the basis of the target audience and the channels they use(Reference Noar36). Social media was a recommended channel for nutrition messaging and communicating with young adults(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,45,Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46) . Furthermore, social media and other online channels offer a practical way of targeting audience segments on the basis of more than demographic characteristics (for example, digital segmentation on the basis of interests or online behaviour)(Reference Stokes39,Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46,Reference Gaysynsky, Heley and Chou47) . One systematic review assessed the effectiveness of song-based health messaging, finding that songs are an effective medium for educating and raising awareness about health issues, particularly when audiences have limited literacy(Reference Sheffield and Irons48). The communication framework proposed by Noar(Reference Noar36) acknowledged the implications that communication channels and their properties have for the design of messages (for example, social media favours short video content) and certain messages may be more suited to certain channels. As such, the framework recommended that the channel is considered when developing messages, and vice versa, that the message is considered when choosing the appropriate channel.

The importance of carefully selecting appropriate messengers was discussed in nine reviews and three reports. Findings from these records indicated that health and nutrition messages should be disseminated by well-known, credible and trusted figures(3,Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Ceretti, Covolo, Cappellini, Nanni, Sorosina and Beatini33,Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,Reference Noar36,Reference Campbell, Uppalapati, Kotcher and Maibach49) . It was suggested that messengers should be chosen with the target audience in mind and be relevant to the audience(Reference Noar36,41) . Three reviews stated that narrative messages are more persuasive and produce fewer counter-arguments when the storyteller has strong ties or similarities to the audience (for example, existing parasocial relationships, the same ethnicity or sexual orientation)(Reference Dudley, Squires, Petroske, Dawson and Brewer42,Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher44,Reference Chen and Bell50) . Leveraging parasocial relationships by delivering health and nutrition messages via social media influencers was suggested in a further three reviews because influencers already have a communication style that resonates with their audience and tend to have a trusting follower-base(Reference Lee, Tan, Siri, Newel, Gong and Proust43,Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46,Reference Gaysynsky, Heley and Chou47) . Health and nutrition professionals were also suggested as messengers who are likely to be trusted by audiences and have the additional benefit of relevant content knowledge(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,45,Reference Campbell, Uppalapati, Kotcher and Maibach49) .

Evidence and recommendations for message characteristics

Message style, wording, length and tone

Four reviews (two meta-analyses, one narrative review and one scoping review) synthesised evidence regarding the use of narrative messaging (that is, storytelling). One of the meta-analyses investigated the effectiveness of narrative versus statistical messaging, concluding that narrative messaging was significantly more persuasive for prevention messaging(Reference Xu51). Similarly, the literature and scoping reviews both concluded that narratives are well accepted, more persuasive and lead to better recall compared with didactic messages(Reference Dudley, Squires, Petroske, Dawson and Brewer42,Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher44) . A meta-analysis by Chen and Bell(Reference Chen and Bell50) investigated the impact of point of view on the persuasive impact of health messages, finding that first-person narratives were significantly more persuasive than third-person narratives, which also aligned with findings from the narrative and scoping reviews(Reference Dudley, Squires, Petroske, Dawson and Brewer42,Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher44) . Furthermore, the use of narratives and case studies to deliver health messages was advocated in the four included reports(3,37,41,45) . In summary, there was consistent support for narrative health messaging.

Use of short, simple and accessible health messaging, constructed in plain, familiar language and avoiding the use of jargon was recommended in eight reviews and three reports(3,Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Ceretti, Covolo, Cappellini, Nanni, Sorosina and Beatini33,Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,Reference Stokes39,41,Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher44–Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46,Reference Brust-Renck, Royer and Reyna52,Reference Okuhara, Ishikawa, Okada, Kato and Kiuchi53) . For example, it was suggested that complex health and nutrition information should be broken down into manageable segments and messages should be kept to approximately three points to facilitate processing and recall(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Okuhara, Ishikawa, Okada, Kato and Kiuchi53) . Furthermore, two narrative reviews synthesised evidence regarding use of ‘fuzzy-trace theory’ in health messaging, both concluding that messaging that conveys the general gist of the information is more persuasive and comprehendible when compared with precise, detailed messaging(Reference Shaffer, Focella, Hathaway, Scherer and Zikmund-Fisher44,Reference Brust-Renck, Royer and Reyna52) .

Message tone refers to the emotion or attitude that is conveyed and included resources discussed the use of emotion to persuade audiences. One systematic review found that factual social media messaging had greater engagement when messages included emotion(Reference Ceretti, Covolo, Cappellini, Nanni, Sorosina and Beatini33). Similarly, a meta-analysis found a significant positive effect of guilt-based written messages on attitudes and intentions(Reference Xu and Guo54). However, the rapid review by Culliford et al. (Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34) suggested that nutrition messages should aim to generate pleasurable emotions to associate healthy food with pleasure. A narrative review by Nabi et al. (Reference Nabi55) suggested both positive and negative emotions can be addressed. They argued that messages with ‘emotional flow’, which target a range of emotions in sequence (for example, from fear to hope), are more persuasive than messages that target a singular emotion. In their scoping review, Rogers et al. (Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46) highlighted evidence that nutrition messages from popular social media influencers tend to highlight the role of bad actors (for example, harmful industries), and the narrative review by Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Uppalapati, Kotcher and Maibach49) found that emphasising the role of bad actors promotes emotional engagement with messaging.

Evidence regarding other elements of message tone, such as humour and formality, was also discussed in the included reviews. Findings from a systematic review indicate that humour can promote sustained attention and influence attitudes and behavioural intentions(Reference Miller, Bergmeier, Blewitt, O’Connor and Skouteris56). Although, Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Bergmeier, Blewitt, O’Connor and Skouteris56) note the impact of humour depends on the audience and most research has used university student cohorts, indicating that humour may be a useful strategy for this group. Complementary to this, VicHealth(45) endorse the use of humour in online messaging for young adults, and Rogers et al. (Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46) found that humour was a popular tactic used by influencers in nutrition messaging. Use of tone that is empathetic and empowering, rather than prescriptive and authoritative, was suggested for nutrition messaging(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34), and Rogers et al. (Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46) found that nutrition influencers tended to use a positive and motivational tone. VicHealth(45) also recommended a positive tone in messaging for young adults, and further recommended tone to be casual, inclusive and authentic.

Message framing

Ten reviews synthesised evidence regarding the impact of loss- versus gain-framed messages, including one Cochrane review and two meta-analyses. The Cochrane review found loss framing led to better understanding of messages; however, this was on the basis of a single study(Reference Akl, Oxman, Herrin, Vist, Terrenato and Sperati26). Conversely, gain framing led to greater perception of effectiveness, although the quality of evidence was low and effect size was small, and there was no benefit of loss or gain framing on the persuasiveness of messages. Meta-analyses by Covey(Reference Covey57) and Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher and Updegraff27) both found no significant effect of framing on attitudes or behavioural intentions. Similarly, an additional four reviews (two narrative, one scoping and one rapid) concluded that the evidence is mixed and there is no clear advantage of loss or gain framing(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,Reference Dudley, Squires, Petroske, Dawson and Brewer42,Reference Van ‘t Riet, Cox, Cox, Zimet, De Bruijn and Van den Putte58) . Considering the mixed evidence, Akl et al. (Reference Akl, Oxman, Herrin, Vist, Terrenato and Sperati26) and Culliford et al. (Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34) recommend a balanced approach through the use of both gain and loss framings. In contrast, Wansink and Pope’s(Reference Wansink and Pope40) narrative review posits that gain-framed messages are more persuasive because most audiences are unlikely to be interested in health messages.

Six reviews acknowledged there was evidence that the persuasive impact of loss and gain framing may vary on the basis of the message topic(Reference Dudley, Squires, Petroske, Dawson and Brewer42) and audience’s characteristics(Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9,Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,Reference Sherman, Uskul and Updegraff38,Reference Wansink and Pope40,Reference Covey57) . Covey(Reference Covey57) found that although there were differences in the impact of gain versus loss framing on the basis of individuals’ motivations, these findings were inconsistent and no recommendation for framing on the basis of individual motivations could be made. Loss-framed messages were reported as slightly more effective for prevention-focused individuals(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34) and for those from collectivist cultures(Reference Sherman, Uskul and Updegraff38). Two reviews reached opposing conclusions regarding the impact of audience knowledge on the effectiveness of framing, with Wansink and Pope(Reference Wansink and Pope40) concluding that gain-framed messages are more persuasive when the audience has limited knowledge of the topic, while Ruxton et al. (Reference Ruxton, Ruani and Evans9) concluded that loss-framed messages are more persuasive in this instance. Message channels were also considered in the context of framing. Ceretti et al. (Reference Ceretti, Covolo, Cappellini, Nanni, Sorosina and Beatini33) concluded that gain framing on websites and social media leads to greater engagement and perception of source credibility. Similarly, two included reports recommended the use of gain-framed messages, specifically for young adults(45) and in workplaces(41). Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Thier, Lee and Nan59) conducted a meta-analysis investigating the persuasive impact of temporal framing of messages. Their analysis indicated that present-oriented messages (focused on immediate/short-term outcomes) had a greater impact on behavioural intentions than future-oriented messages (focused on long-term outcomes). They also investigated gain and loss framing as moderators and found that gain framing did not significantly moderate the persuasive effects of temporal framing(Reference Wang, Thier, Lee and Nan59). Overall, the evidence and recommendations about how to frame health and nutrition messages was mixed leading to the recommendation of a balanced approach. In addition, decisions about framing should be made according to audience characteristics and preferences.

Visual elements

Three reports recommended that imagery should be incorporated into messaging to attract attention and humanise the message(3,41,45) . Imagery that depicts people who are relatable to the target audience and culturally appropriate elements (for example, symbols, foods) were recommended in the three reports to enhance message relatability and acceptance. Practical recommendations about imagery were also made in these reports, including avoiding the use of stock images, keeping graphics simple and clutter free and using illustrations or photo stories to present technical information to enhance comprehensibility(3,41,45) . Use of imagery to improve message understanding was also evidenced as a useful tactic in one narrative and one rapid review(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici34,Reference Brust-Renck, Royer and Reyna52) . Furthermore, one systematic and one scoping review found that imagery with consistent layout and branding can attract attention and engagement on social media(Reference Ceretti, Covolo, Cappellini, Nanni, Sorosina and Beatini33,Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46) . In summary, included resources indicate that imagery can enhance the acceptance, understanding and accessibility of messaging.

Discussion

This rapid review synthesised evidence and best practice recommendations regarding the development and characteristics of persuasive health and nutrition messaging for awareness raising. Twenty-seven reviews and four grey literature reports were included. Results showed that there was consistent evidence in the literature for an audience-centred approach to health and nutrition messaging. Data synthesis also resulted in identification of key characteristics that can be used to enhance the persuasiveness of awareness raising messaging, including the use of narrative messaging, simple language, conveying the general gist of information and incorporating imagery. Findings can be used to inform health and nutrition promotion messaging in public health and research settings.

Included literature recommended an audience-centred approach to health and nutrition messaging. Key aspects of this approach include audience segmentation, formative research to inform the tailoring of messages to the audience, testing messages with interest-holders and target audiences, and refining messages on the basis of feedback. These elements are commonly used in health and nutrition communication and align with a social marketing approach, which has been widely used in health and nutrition promotion for many years(Reference Shams, Haider and Platter60). Furthermore, the mixed findings regarding some message characteristics such as framing observed in this review highlight the importance of segmenting audiences, testing messages and refining them to ensure they are persuasive. While an audience-centred social marketing approach may improve the persuasiveness of messages, it should be acknowledged that it can be resource intensive, and health and nutrition promotion often faces funding and resourcing constraints(Reference Barry61). As such, it may not always be feasible for organisations to follow all the recommendations outlined in this review. Potential solutions may include use of existing research, reports and open-access data to inform audience segments, communication channels and message tailoring. Examples of open-access resources include the DataReportal annual reports that provide global and regional data on digital communication channel usage (to inform channel selection)(62), the Communicating Health Toolkit, a resource developed by Australian universities and health organisations that provides information and templates for health communication(63), and values-based messaging resources and messaging guides by Common Cause (to inform message development and design)(64). In addition, establishing partnerships with researchers and not-for-profit organisations with similar goals may assist with formative research and message testing when resources are limited. The Commission on Excellence and Innovation in Health provide a four-step process and strategic framework for developing meaningful collaborative partnerships in public health, which may be useful for organisations seeking to establish partnerships for health or nutrition communication(65).

Some messaging characteristics and tactics that are effective and persuasive may risk unintended consequences. For example, three included reviews recommended working with social media influencers to disseminate health and nutrition messaging(Reference Lee, Tan, Siri, Newel, Gong and Proust43,Reference Rogers, Wilkinson, Downie and Truby46,Reference Gaysynsky, Heley and Chou47) . While, as their name suggests, influencers are good at persuading their audiences, they may contribute to body dissatisfaction, disordered eating and weight stigma(Reference Clark, Lee, Jingree, O’Dwyer, Yue and Marrero66,Reference Holland and Tiggemann67) . As such, care should be taken when working with influencers to ensure messages do not inadvertently promote weight bias and stigma. Influencers and their content should be thoroughly vetted and guidance from eating disorder organisations should be considered when communicating about food(68). In addition, Gaysynsky et al. (Reference Gaysynsky, Heley and Chou47) recommended digital segmentation and microtargeting in online environments to target key groups. They note that this approach shows promise for persuasive and audience-centred messaging; however, it raises ethical issues regarding utilisation of user data to inform segments and risk of harm from targeted messaging on potentially sensitive topics (for example, pregnancy messages are likely to reach people who recently experienced pregnancy loss)(Reference Gaysynsky, Heley and Chou47). When communicating about sensitive topics, content warnings and referrals to sources of support could be included to mitigate the risk of harm. While digital segmentation raises ethical questions that must be considered, it is also important to consider that most commercial industries, including harmful ones, use this method to advertise(Reference Dunlop, Freeman and Jones69,Reference Northcott, Sievert, Russell, Obeid, Angus and Parker70) , and public health messaging may be unable to compete without adopting similar approaches to target audience segments. More broadly, health and nutrition messaging can lead to psychological distress, anxiety, fear, guilt or stigma(Reference Rossi and Yudell71), and careful consideration of ethical practice and risk of unintended consequences is required when designing and disseminating persuasive public health and nutrition messages. Co-design, message testing and consultation with interest-holders, which are key recommendations from this review, can help to minimise potential harms(Reference Rossi and Yudell71). Consultation with the intended audience and interest-holders before large-scale dissemination provides an opportunity to receive meaningful feedback about potentially negative impacts of messages (for example, reinforcing stigma) and refine them accordingly so they are less likely to result in unintended consequences(Reference Rossi and Yudell71).

This review is novel because it synthesised evidence and recommendations regarding broad facets of awareness-raising messaging, from development to message characteristics, and has implications for practice and research. Evidence was synthesised to provide actionable advice to inform persuasive messaging (for example, summary in Table 4). This advice can be used by health and nutrition promotion organisations and researchers to guide their messaging and may be particularly useful for small organisations without dedicated communications staff. Findings will be used to inform the development of a framework to guide nutrition messaging for awareness raising in Australia, which will be disseminated to relevant organisations. While this review is intended to inform a communication framework for the Australian context, most reviews and reports that were captured had an international focus, and findings are also relevant to regions outside of Australia, particularly English-speaking populations and high-income countries. However, some evidence from non-English-speaking and low- and middle-income countries was also captured, and findings may also have relevance to these settings. Furthermore, outcomes from this review have relevance to other health topics and can be used to guide the development of awareness raising messages in other contexts. Future research should explore the novel approaches to health and nutrition communication that were recommended in the included studies, such as working with influencers and use of digital segmentation, as research in this area is in its infancy. To date, most studies have been small pilot studies and relied on measures such as social media engagement and reach to measure impact(Reference Gaysynsky, Heley and Chou47), and future research should therefore employ larger samples and measures of persuasion, such as changes in attitudes, beliefs and intentions. Case studies that investigate partnerships between influencers and health organisations would also be useful to inform future communication campaigns with influencers.

Limitations of this rapid review should be acknowledged. The search strategy used may have missed some relevant literature; however, it was thoroughly tested and developed in consultation with a librarian and members of the research team highly experienced in research synthesis. Only one researcher conducted grey literature screening, which could have also resulted in relevant reports being missed. Similarly, only one researcher was responsible for data extraction, which may have led to mistakes or errors in the interpretation and extraction of data. To help ensure reliability in grey literature screening and the extraction of data from reviews and reports, any resources that were ambiguous or difficult to judge were flagged for discussion with the senior author who then assisted with screening and extraction decisions. Reviews and grey literature reports that were written in languages other than English, or published by public health organisations that did not include Australia as a region of focus, were excluded from this review, which may limit the generalisability of findings to non-English-speaking populations and low- and middle-income countries. However, importantly, some of the literature that was captured did include evidence for non-English-speaking populations and low- and middle-income countries, for example, the WHO and WHO Western Pacific communication frameworks(3,37) . Another limitation is that the risk of bias of included reviews was not assessed, and therefore, the quality of the evidence was not considered. Finally, there was some overlap between the topics covered in the included reviews (for example, ten reviews covered gain- versus loss-framed messages) and this review may have captured the same piece of original research multiple times because it was included in multiple reviews. However, the overall impact of this is likely to be small.

This review also has some important strengths. To the knowledge of the authors, it is the first review to synthesise evidence regarding broad facets of health and nutrition messaging for awareness raising. The inclusion of review articles and general health topics enabled synthesis of a large scope of evidence about many aspects of awareness raising messaging from over 700 studies. Furthermore, the inclusion of grey literature extended the scope of content captured beyond academic evidence to also include experience and recommendations from prominent public health organisations. The breadth of evidence and recommendations captured in this review makes it a valuable contribution to the field and it provides a resource to inform awareness raising messaging in research and practice, which has been highlighted as a priority area for health and nutrition(3,4) . While the risk of bias of included reviews was not assessed, ten systematic reviews (including one Cochrane review and seven meta-analyses) were included. Compared with reviews that use non-systematic methods, these review types are more rigorous, with Cochrane reviews considered the gold standard, indicating that high-quality evidence was captured. In addition, there was a high degree of consistency in the findings and key recommendations of the included resources, further increasing confidence in the findings of this rapid review.

Conclusions

This rapid review provides a synthesis of evidence and recommendations for the development of persuasive and health and nutrition messages for awareness raising. Results showed that there was consistent support in academic and grey literature for an audience-centred approach to health and nutrition messaging that uses social marketing principles to segment audiences, tailor messages and test them with audiences and interest-holders. Characteristics related to the style, wording, length, tone and visual elements of awareness raising messages were identified and summarised to provide practical guidance to inform health and nutrition communication in research and health promotion settings.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422426100328

Data availability statement

No new data were generated from this research. The extracted data from included studies will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nicole Biggs who assisted with the screening of grey literature and health librarian Lisa Grbin who provided consultation on the search strategy.

Financial support

This work was funded by a Heart Foundation Vanguard Grant (number 107268).

Competing interests

In the last 5 years N.K. has consulted for the Pan American Health Organization, Resolve to Save Lives, John Hopkins University and UNICEF. None of these organisations had involvement in the current research. All other authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Authorship

E.D. conducted the literature searches, screening, data extraction, synthesis and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. P.M. acquired the funding, conceptualised the research, contributed to methodological decisions, screening of literature and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. C.G.R., N.K. and S.A.M. acquired the funding, contributed to the conceptualisation of the research, methodological decisions and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. K.W. contributed to methodological decisions and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.