Introduction

The end of the 3rd c. BCE witnessed the construction of a new permanent marketplace in Rome: the macellum, built on the northern side of the Forum where the Basilica Aemilia would later be located. Livy’s account of this construction is ambiguous: he describes how the Forum Piscatorium, or fish market, burned down in 210 BCE but later mentions that the censors had the macellum rebuilt in 209 BCE.Footnote 1 While Livy might be using both terms to refer to the same structure, implying the existence of a macellum before 209 BCE,Footnote 2 I propose a different interpretation. The renaming of the rebuilt market as a macellum may reflect a more profound conceptual and functional shift in market architecture, one that was linked to economic transformations, such as the early monetization of the retail trade.

The earliest archaeologically datable examples of macella in the western Mediterranean, with their characteristic enclosed plans, do not appear until the second half of the 2nd c. BCE, and the plan of the building described by Livy is unknown. But the introduction of this new terminology at this particular time, originating in the Greek word for enclosure (μάκϵλλον), is of particular relevance here.Footnote 3 Whether the market in Livy’s account was entirely new or a restoration of an earlier structure, the terminology signals the same closed-off architecture known from later examples whose enclosed and walled plan, in contrast to the open and undoubtedly disorderly character of commercial fora, provided both physical security and the means for administrative oversight by officials of coin purchases and revenues.Footnote 4 Around the same time as the market described by Livy appeared, in the late 3rd c. BCE, the use of coinage emerged in Roman cities, with the new denarius system introduced in 212 BCE. This system, which included small denominations for daily shopping, may have coincided with, or contributed to, the development of a centralized space intended to streamline the control and exchange of these emerging high-value items.Footnote 5 What more effective way to oversee this new commercialized trade than by building a permanent, inward-facing marketplace, with controlled access points, in the political and administrative center of the city?Footnote 6

Even if the importance of control has been considered with differing levels of detail in studies on macella,Footnote 7 the aspect of supervision has never been contextualized within broader economic transitions, nor has it been presented as part of an underlying administrative mechanism that was, as I argue, the primary motivator behind the emergence and construction of these specialized markets. This fresh perspective challenges the current consensus among scholars who define the key driving force and long-term purpose of the macellum, and its contained layout, as being to facilitate elite consumption of high-end food products, mostly fish, meat, and game, in a tightly regulated setting.Footnote 8

In this paper, I wish to complicate this established understanding of macella as symbols of an elite lifestyle by advocating that these markets primarily functioned as control structures within an increasingly integrated economy. Economic restructuration between the 3rd and 2nd c. BCE, comprising financial innovations, the rise of market-oriented rural production, and an increasing dependency on institutional and material arrangements for the management of trade, trends that were formalized during the later Republic and early Empire, drastically changed economic behaviors.Footnote 9 Rather than being a market privileging upper-class lifestyles, the macellum, first and foremost, embodied these new economic behaviors and, in particular, the management of this intensified economic complexity. I will begin by challenging the argument related to elite consumption more broadly and will then explore what I define as the main economic motivating factors in the development and construction of macella.

The macellum: a symbol of Roman elite consumption?

Following Claire De Ruyt’s authoritative publication synthesizing historical and archaeological data for 78 macella across the Roman Empire,Footnote 10 academic interest in this type of Roman food market has flourished. To date, a total of 149 macella have been identified through historical, epigraphic, and archaeological data, with 43 of them located in Roman Italy and 106 in the provinces (Figs. 1–2; Table 1).Footnote 11

Fig. 1. Distribution of macella across the Roman Empire. See Figure 2 for detail. (Map by author.)

Fig. 2. Distribution of macella across the Roman Empire. Detail. See Table 1 for key to numbers. (Map by author.)

Table 1. Macella identified across the Roman Empire with presumed original construction date. In the case of inscriptions, the inscription is dated and explicitly refers to either construction, restoration, or maintenance. In the latter two cases, the original construction must have occurred prior to the stated date. Markets with recorded faunal assemblages are marked with an asterisk. Data are drawn from primary and secondary sources, including publications, archaeological reports, and epigraphic sources. Where “uncertain” appears, it indicates that the identification remains doubtful.

Modern research aligns in characterizing these markets as upscale and exclusive buildings dedicated to the sale of luxury foodstuffs, such as fish, meat, poultry, and game. This focus on costly merchandise privileged elite customers and provided them with a setting in which to substantiate and practice their extravagant urban lifestyles. As per the findings of C. De Ruyt and Joan Frayn, the macellum existed for those social classes that could afford expensive products,Footnote 12 representing an upper-class lifestyle associated with and stimulating luxury trade for the organization of elite dinners and banquets.Footnote 13 John Patterson and Claire Holleran elaborated on and emphasized this latter argument: the macellum was the quintessential place for purchasing delicacies traditionally served at dinner parties and, thus, materialized the important social role of banqueting in the 1st and 2nd c. CE.Footnote 14 Both authors correlate the enclosed form of the macellum with elite consumption norms of control, and Holleran goes on to infer that the intention behind the development of these markets may have been “to ensure that the wealthy could purchase food in a suitable and regulated environment.”Footnote 15

While I certainly do not dispute that elites were significant customers of macella in Roman towns, I would like to explore two key arguments that problematize the idea that the macellum is a representation of elite lifestyles exclusively. First, the claim of high-end consumption is supported almost entirely by textual records that concern the city of Rome. Literary anecdotes sketch the shopping behaviors of wealthy consumers in the macella of Rome, stressing excessive spending and expensive goods, along with governmental attempts to limit these ostentatious practices. Aside from the fact that these accounts, particularly the reports of high prices, were likely exceptional and exaggerated, a more crucial consideration is that it is not reasonable to extrapolate from these texts, which mirror the dominant concentration of elite consumers in the largest and most densely populated metropolis of the Roman Empire, to the situation in the numerous smaller and more socially diverse towns that were equipped with a macellum.Footnote 16

Second, this conventional interpretation largely relies on the basic premise that fish and meat, especially their fresh varieties, were commodities emblematic of elite food preferences. However, recent archaeological research is uncovering much broader access to these food products across different social strata in the Roman world,Footnote 17 with distinctions in socioeconomic status primarily reflected in the quality of these foodstuffs.Footnote 18 Therefore, for a more accurate reconstruction of the customers of these markets, and most importantly one that is supported by empirical evidence rather than literary testimonies, it is essential to consider more closely the archaeozoological findings that were recorded during excavations of macella, an aspect that has strangely been overlooked thus far. Reviewing the faunal remains from individual excavations would allow for evaluating the social clientele within each local context, rather than, as at present, generalizing that these markets catered to rich customers Empire-wide.

By carefully revising these two arguments, I challenge the idea that macella were market structures developed and constructed throughout the Roman world solely to facilitate and empower economic behaviors associated with high-status consumption.

Evidence for high prices beyond Rome?

The idea that macella were food markets for luxury produce is largely supported by Latin literary records related exclusively to consumption practices in Rome. Countless textual accounts, starting with the 3rd-c. BCE writings of Plautus, underline the high prices of food products for sale, or report on price regulations in Rome’s macella, prompting scholars to argue that these markets were accessible exclusively to upper-class citizens.Footnote 19

Yet, it must be stressed that most of the literary anecdotes concern a particular type of fish, the mullus, or red mullet. Horace and Seneca, for instance, mention prices of 3,000 and 5,000 sesterces for a single mullet.Footnote 20 Suetonius reports that Tiberius, upon hearing that three mullets were sold for 30,000 sesterces, ordered annual supervision of prices in the macellum.Footnote 21 This type of fresh marine fish was particularly valued because of its scarcity: Roman elites preferred these fish large and fatty, yet catching larger specimens was extremely rare, and the species was unsuitable for artificial cultivation in fishponds.Footnote 22 It is, therefore, unsurprising that big mullets were sold for big prices. Annalisa Marzano also associates these high prices with the social value of displaying large specimens at banquets and the elite competition that resulted from this practice.Footnote 23 Latin satirists thus mocked these price battles through literary exaggeration, while emperors attempted to restrain such excessive behavior and display of luxury among elites in the city by introducing new laws and increasing control in the market.Footnote 24

Consequently, the frequency of mullet sales in the macellum is undoubtedly overstated in the literary tradition from Rome. It is far more reasonable to assume that smaller fish, mentioned by Apuleius as being sold at much lower prices, were more commonly purchased but did not receive the same literary attention.Footnote 25 Terence, by way of example, distinguishes between cetarii, specialized in the sale of large fish, and piscatores, dealing in small fish, at the macellum.Footnote 26 While mullet may have been accessible only to rich citizens, Terence’s enumeration of traders implies that differently priced products were available in the market and were, potentially, affordable for broader segments of society. This applies not only to fish but also to meat: among the professions Terence lists are fartores, or sausage makers. Sausages, often sold in tabernae or popinae, were considered one of the cheapest type of meat snacks.Footnote 27 Unsurprisingly, Plautus’s Aulularia does not mention these inexpensive options in his account of Euclio’s visit to the macellum, which serves to emphasize (and exaggerate) overpriced products.Footnote 28 A 2nd-c. imperial decree from Pergamum reveals that, for many ordinary people, small fish were the only food they could afford at the marketplace (agora) – these could be purchased by one person alone using bronze coins, or jointly, with silver denarii, before splitting the purchase.Footnote 29

Moreover, even if ancient sources are silent on this matter, one might speculate – following A. Marzano’s interpretation and by analogy with modern market practices – that fresh food products were sold at reduced prices toward the end of the day to avoid spoilage and loss of profit. This would have offered lower social classes the opportunity to purchase produce that was normally out of their financial reach.Footnote 30

With the exception of price data for mullet in Rome, no written records survive on the cost of goods in the Empire’s macella. Nevertheless, scholars have taken the high prices observed in Rome – where the concentration of elite consumers was unparalleled – as indicative of price levels and, by extension, the socio-economic makeup of market clientele in other urban centers.

Following this line of reasoning, macella would likely have been constructed only in towns with a sufficient presence of wealthy elites who could afford expensive products and sustain the market buildings, as J. Frayn has previously argued.Footnote 31 However, their widespread presence in medium-sized and smaller urban centers – in both Italy and the provinces – where elites were certainly present but in fewer numbers than in Rome, suggests that macella in these towns were perhaps tailored to serve more varied consumer demands, offering a broader selection of products across various price categories – and possibly even fulfilling alternative local functions. If we accept that macella were adapted to local habits of consumption and production, we should also consider greater flexibility in their social demographics, something that may have been reflected in the particular social fabric of each town. As will be discussed momentarily, the archaeological material related to the types of food sold in local markets, while limited, makes it difficult to uphold that they catered exclusively to high-status consumers across the Empire.

Macella and their archeozoological records: opportunities and challenges

Standard views of the Roman diet have long considered meat and fish consumption among non-elites as rare, implying a primarily vegetarian diet based on grains and vegetables, with occasional meat during public (religious) festivals.Footnote 32 Such assumptions were largely based on elite textual sources, which provide minimal insight into the animal-based foodstuffs consumed by less privileged classes.Footnote 33

Recent zooarchaeological and osteological studies, in both urban and rural areas and across Italian and provincial Roman contexts, have demonstrated that animal products were part of the diet of various socio-economic groups.Footnote 34 Yet, an important distinction is apparent: although archaeological evidence proves that meat and fish were more frequently consumed than previously thought, it also shows that significant disparities existed in the quality and quantity of these foods available to different social classes. Not only could elites afford more meat and fish overall; they also had access to a wider range of products, including rare items such as large marine fish and wild game, and higher-quality cuts. Zooarchaeological studies identify rarity and quality as key indicators of luxury diets at archaeological sites.Footnote 35

Rarities, like the red mullet, were costly due to their scarcity and because they involved significant effort to procure, produce, and transport, driving up their price on the market.Footnote 36 Such scarce fresh marine fish were purchased by elites, while non-elites typically ate more ordinary varieties, like small marine fish, freshwater fish, fish-based sauces, and preserved fish.Footnote 37

Wild game also fell into the luxury category, especially due to the high cost – or risks – involved in hunting.Footnote 38 For example, Varro noted a price difference between wild boars and those raised on estates, which De Ruyt attributed to the greater risk associated with capturing wild animals.Footnote 39 Similarly, Columella observed a higher market value for wild-caught fish than for fish bred in villa fishponds.Footnote 40 These examples illustrate how scarcity drove up the cost and perceived value of certain foods in contrast to the more “abundant” products reared on villa estates. This again proves that products in the macellum fluctuated over a range of price categories.

In addition to rarity, the quality of meat, as inferred from anatomical body parts and age categories in zooarchaeological assemblages, is another significant marker of elite consumption. Wealthy individuals preferred premium cuts from young animals, like the fattier body parts around the ribs, vertebrae, shoulder, and pelvis, while less affluent social classes consumed leaner cuts from older animals, processed meats like sausages, and more common poultry such as chicken.Footnote 41 As noted, sausage making – one of the most disreputable trades – appears in Terence’s list of macellum trades. While scholars often emphasize the high-end professions, like cuppedinarii, makers of delicacies, they tend to neglect these low-status trades, which may point to a more inclusive customer base.Footnote 42

To counter the ambiguous, elite nature of literary texts, evaluating faunal remains from excavations could offer an archaeologically supported view of the clientele in these markets. A preliminary exploration of the archaeozoological data currently published from macella excavations reveals both challenges and opportunities in this type of analysis.

Despite the identification of 84 macella through stratigraphic excavation, faunal remains, including bones from mammals, birds, and fish, have been reported rather infrequently: bones from larger mammals have been reported in 24 market buildings, whereas remnants of fish, like scales and shells, were documented in only six markets (Table 1). Two potential explanations for this limited archaeological registration of faunal remains are worth underlining here. First, the scarcity of animal remains may be due to ancient practices, like food and butchering waste disposal elsewhere, routine cleaning of the markets, and the markets’ subsequent repurposing for industrial and domestic usage during the Late Antique period.Footnote 43 Second, bone materials might have been missed due to inadequate excavation strategies, notably a lack of archaeozoological sampling. Especially in older excavations, where sampling was absent and/or the focus was on retrieving luxury objects rather than studying bone remains to address socioeconomic questions, these items might have been (literally) overlooked.

Unfortunately, the underreporting of zooarchaeological documentation strategies in fieldwork publications limits our understanding of faunal assemblages. Some studies list the types of domestic and wild specimens found but omit any further details, such as the number of identified specimens, or variables like sex, age, and anatomical body part distribution.Footnote 44 For most excavated macella with recorded faunal remains, it is unclear whether further classification and analysis have been conducted, whether they remain unpublished, or whether the bones were – and perhaps still are – simply stored without any follow-up analysis.

In the case of Pompeii’s macellum, a vague reference to “large quantities of fish scales” from the tholos drainage reflects that zooarchaeology was not an established discipline at the time of the 19th-c. excavations.Footnote 45 But even in macella excavated during the 20th and 21st c., faunal remains often appear to have been treated as secondary or negligible during the excavation and analysis process. For example, fish waste and animal bones unearthed in the sewer system and a shop during late 20th-c. excavations at the macellum of Herdonia are absent from the archaeological site report.Footnote 46 Similarly, at the macellum of Aquileia, although a brief excavation summary notes the faunal analysis of numerous bone finds – mainly cattle and pig – the results were never published.Footnote 47 At the macellum of Segesta, excavations have indicated that the tholos, the primary criterion used to identify the market, may have functioned as a butchery, given the abundance of butchered animal bones recovered from its floor levels.Footnote 48 Unfortunately, no further zooarchaeological details have been published.

Excavation at the macellum of Thasos revealed butchery and fish waste from oxen, molluscs, tuna, and angelfish. Although preliminary results from the archaeozoological study have been published, a full assessment remains pending.Footnote 49 At Sagalassos, the substantial volume of animal bones points to butchery, food preparation, and craft production within the Late Antique macellum.Footnote 50 One room contained a waste dump with over 10,000 bone fragments, predominantly from domestic species such as cattle, sheep/goat, and pig. A brief evaluation of the assemblage seems tentatively to indicate a clientele from a wide social spectrum,Footnote 51 though more comprehensive publication is needed to confirm this. Clearer evidence for a varied customer base, however, is found in the food markets of Viroconium Cornoviorum, Colonia Ituci Virtus Iulia, and Iruña-Veleia, which are briefly discussed below.Footnote 52

Excavations carried out between 1955 and 1985 at Viroconium, modern Wroxeter (Britain) (Fig. 3), produced large amounts of animal bone from portico pits abutting the macellum.Footnote 53 These fragments, deriving from butchery waste from the macellum or from wooden stalls that sold meat in its portico, are dated to the first half of the 3rd c. CE.Footnote 54 Iron hooks found in the pits were most probably used for hanging the carcasses during butchery or for the sale of the meat. The majority of the bone fragments (13,477) belonged to cattle, with only 10% of these animals slaughtered at an age younger than 36–42 months. Sheep, goat, and pig were slaughtered at a similarly mature age, undermining traditional views that equate macellum consumption with high-quality meat from young animals.Footnote 55 Due to the sampling strategy, hand collection and no sieving, small bone fragments are almost entirely absent from the assemblage. This possibly explains why small mammals, such as birds, form only a minor part of the sample.Footnote 56 The predominance of old animals has been interpreted as a local practice either of not slaughtering animals before maturity – for instance, using cattle for traction first and sheep for textiles – or of rural producers simply not responding to demands of urban elites.Footnote 57 Yet, in combination with a study of the skeletal body parts, which, especially for cattle, represent a mixture of high-, medium-, and low-value meat bones, and only a small sample of game, these data might also prove that the macellum was not exclusively related to luxury consumption.Footnote 58

Fig. 3. Architectural plan of the macellum at Viroconium (Wroxeter). (After Ellis Reference Ellis2000, fig. 5.3, 343.)

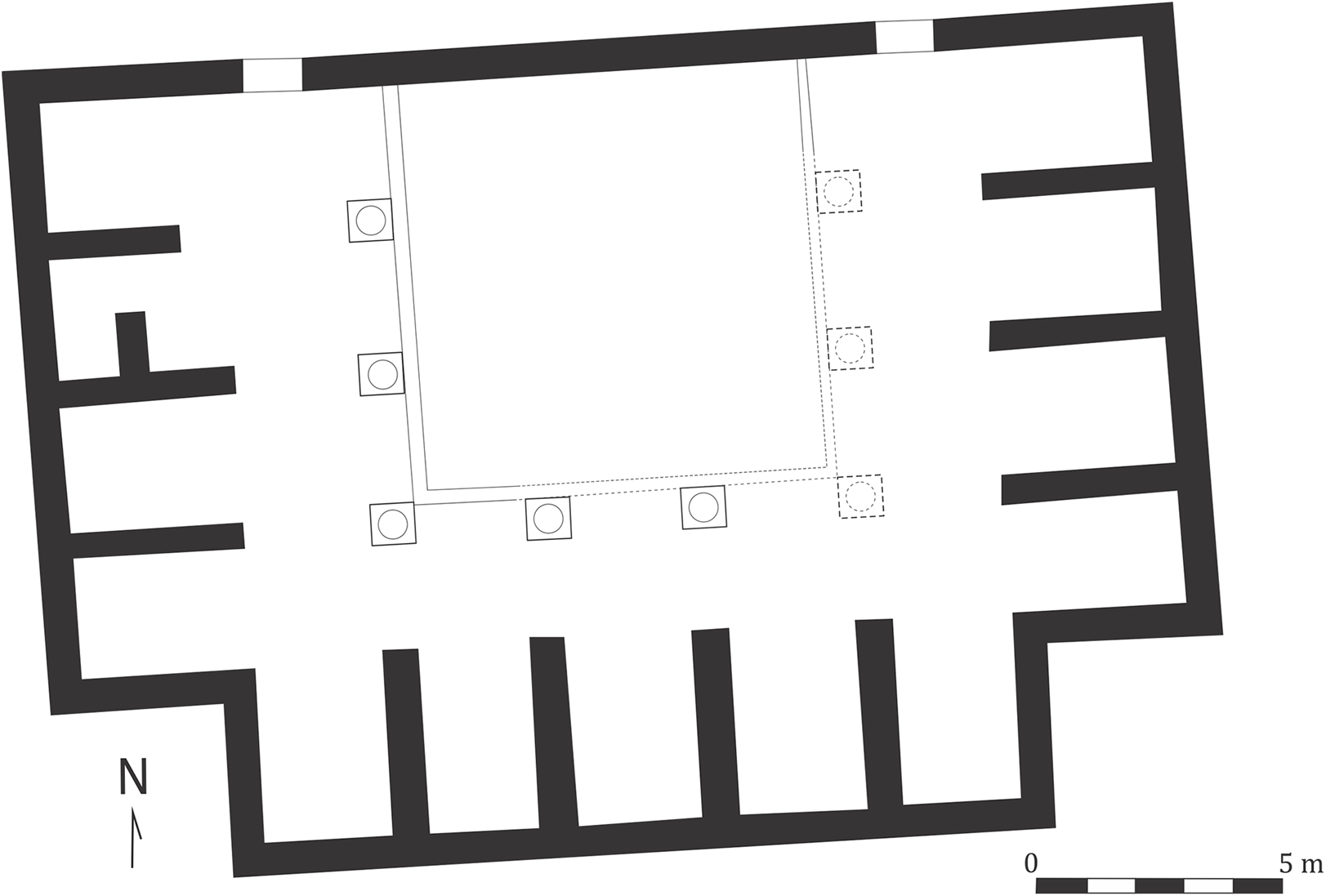

A similar picture emerges from faunal remains found at the market buildings excavated in two towns in Hispania: Colonia Ituci Virtus Iulia (modern Torreparedones, approximately 60 km east of Córdoba) (Fig. 4) and Iruña-Veleia (in the modern province of Álava). The former small Roman town was equipped with a macellum, a rectangular structure (24 x 16.50 m) with a courtyard surrounded by a portico and 13 tabernae on three sides, in the Tiberian/Claudian age.Footnote 59

Fig. 4. First construction phase of the macellum at Colonia Ituci Virtus Iulia. (After Morena López et al. Reference López, Antonio, Rosa and Martínez Sánchez2012, 49.)

Excavations of this structure between 2009 and 2010 uncovered a substantial quantity of animal bones (1,227 fragments) dating to three distinct phases.Footnote 60 While the first phase relates to the pre-construction of the building and is not considered here, the second and third phases align with the market’s active use.

A dump of butchery waste, located just outside the building and containing 652 bone fragments, relates to High Imperial activity in the market. Notably, cattle bones (483 anatomical fragments), which came from at least 14 individuals, nine of which were slaughtered in adulthood, predominated.Footnote 61 A later, 3rd-c. CE waste deposit shows a significant transition towards the sale of goats and sheep at the market. While butchery waste from the first half of the 3rd c. CE still mainly comprises adult cattle, the carcass remains from the second half of the century consist almost exclusively of caprines slaughtered between the ages of 1 and 3 years. Pig bones were notably underrepresented across these faunal assemblages, and game was rare, with the remains of only five wild boars and one deer present.Footnote 62 These consumption patterns likely reflect local animal husbandry strategies, where the predominance of older cattle, sheep, and goats are indicative of a focus on fully exploiting secondary resources such as wool, milk, and labor before slaughter.Footnote 63 The older age of cattle is particularly notable, indicating they served as draught animals up until a late age.Footnote 64 However, this faunal record also implies that the macellum at Ituci Virtus Iulia served a diverse customer base, as evidenced by the almost complete absence of wild specimens and the predominance of cattle, sheep, and goat bones over those of pigs. It is worth noting that Diocletian’s Price Edict confirms that meat from cattle, sheep, and goats was cheaper than pork meat.Footnote 65

In Viroconium and Ituci Virtus Iulia, the faunal assemblages lacked fish bones, which may point to a primarily meat-based diet in these inland towns, though the absence could also be attributed to the lack of wet sieving in the excavation’s sampling strategy. Excavations at the macellum of Iruña-Veleia (2010–18) (Fig. 5), approximately 55 km from the Bay of Biscay and situated along a major Roman road, employed systematic collection during excavation and the flotation of selected samples. This resulted in the recovery of 4,113 fishbone remains from at least 26 species, along with 800 mollusk remains, representing 13 taxa.Footnote 66 The analysis of these materials proves that fish formed an important supplement to the diet of this inland town’s consumers and, furthermore, illustrates that the sale of fish through the macellum targeted various socioeconomic groups among the urban population.

Fig. 5. Reconstructive drawing of the macellum at Iruña-Veleia. (After Reinares Fernández Reference Reinares Fernández2022, fig. 26, 31.)

During the active phases of the Iruña-Veleia macellum, a central porticoed courtyard structure with surrounding tabernae built in the Late Neronian period, both fluvial and marine fish species are represented. In the 1st c. CE, marine species, particularly maragota and snapper, dominate the assemblage. By the 2nd c. CE, there is a marked rise in river fish, with cyprinids becoming the most prominent product, while high-value fish like mullet and sea bass are only sparsely found.Footnote 67 The faunal assemblage from an excavated domus in the town shows a negligible presence of freshwater fish – only 15% of the identified remains, compared to over 40% in the macellum. Who, then, consumed the freshwater fish that were for sale in the macellum? Scholars claim that this high proportion of river species signals that the food market at Iruña-Veleia catered to a socioeconomically diverse group of consumers, who certainly benefited from the lower prices of some types of freshwater fish; marine fish were less readily available locally, their transportation over long distances greatly affecting their price.Footnote 68 This interpretation is further supported by the recovery of oysters in a wide range of sizes – mainly from the 2nd c. CE onwards – implying that more ordinary consumers may have been able to purchase the smaller, less expensive types.Footnote 69 These food habits surely fluctuated, as the desirability and market value of fish species were subject to shifts in culinary fashion and local and regional variability. What was once common could later become a prized delicacy, and vice versa.Footnote 70

In conclusion, despite the archaeological evidence being limited to only a few macella – because faunal remains were not always preserved or systematically recorded during excavations – this data substantiates the view that these specialized markets were not solely aimed at elite consumers. Instead, they addressed the needs of a more diverse range of social classes, which would have altered in accordance with local socioeconomic conditions and purchasing power. These findings highlight the importance of carrying out high-resolution zooarchaeological analysis during excavations of such market buildings, a focus that is only now emerging. Recent excavations at Aeclanum revealed significant quantities of animal bones – particularly cattle – indicating continued butchering activities in the Late Antique macellum, though it had fallen partially out of use.Footnote 71 Similarly, at Falerii Novi, recent systematic zooarchaeological sampling of the macellum shows cattle was most common, followed by pig and caprine bones.Footnote 72

The macellum as supervisory mechanism in a complex Roman economy

Having presented new arguments challenging the idea that the macellum was an index of elite consumption, I will now outline three alternative factors that account for the development of these specialized food markets. Specifically, this analysis positions the emergence and establishment of macella within the broader context of the increasing complexity and rationalization of the Roman economy that began in the Middle Republic, particularly between the 3rd and 2nd c. BCE. This complexity was shaped by financial innovations, agricultural specialization, and the growing standardization of food trade, developments that were formalized further in the Late Republic and Early Empire.

In this evolving economic landscape of the Middle Republic, the need for formal mechanisms to manage the food supply became more urgent. I propose that the macellum was established during this period as a distinct architectural type to address that need: a purpose-built market space aimed at regulating the sale and distribution of food in urban centers. From its inception, the macellum functioned as a supervisory instrument, with its architectural layout and administrative structure enabling constant monitoring by appointed public officials. This high level of control was warranted by the nature of the commodities sold: meat and fish, valuable foodstuffs that involved substantial investment. The supply chains for these products incorporated costly, time-consuming, and logistically demanding processes, such as rearing, catching, slaughtering, and preserving, given also their perishable nature without refrigeration. These factors, alongside the need for hygienic practices, heightened the importance of regulation. As Vasilis Evangelidis and Julian Richard observe, one of the principal advantages of these enclosed structures was their capacity to support sanitary practices. While open-air fora had access to nearby fountains, the macellum incorporated hydraulic infrastructure, ensuring cleaner environments and stricter control over sanitary conditions for food processing and sales.Footnote 73

Much like the grain supply, for instance, which was managed through horrea – tightly administered storage facilities with restricted access – the trade in meat and fish required regulated conditions. However, unlike horrea, macella were always municipal property, signaling the involvement of local administrations and/or elites in the management of food sales.Footnote 74 Throughout the later Republic and Empire, the macellum thus operated as a regulatory body, offering urban authorities and agents a means of supervising and intervening in the food trade.

Financial innovations

At the outset of this paper, I made the case that Livy’s use of the term macellum to denote the newly rebuilt food market on the Forum Romanum in 209 BCE was a direct consequence of monetary developments in the Roman economy. The introduction of the silver denarius system in the late 3rd c. BCE, with its smaller denominations of bronze coins facilitating everyday commercial trade and market transactions, led to growing monetization in both urban and rural contexts.Footnote 75 The macellum exemplifies this trend toward coin-based exchange both conceptually and architecturally.

First, it represents a new mentality and mode of urban commerce, where coins played a more crucial role in everyday purchases, encouraging attention to regulating payments and protecting the coins. Second, the walled and secure design of the macellum physically manifested this increased sense of control, an element missing from, for instance, commercial fora and temporary markets, which, with their open spatial arrangements, may have resulted in less careful and more loosely managed commercial interactions.Footnote 76

This difference might also be attributed to the fact that specialized fora, which continued to operate alongside macella, served an entirely different function. Fora were wholesale markets, where rural producers gathered with their animals and fresh produce, setting up temporary stalls or selling directly from their carts. They sold products in bulk, mostly to butchers or small-scale retailers.Footnote 77 After completing their commercial transactions, these farmers returned home with their profits, unsold goods, and even equipment. As a result, there was no need for continuous supervision of revenues or market infrastructure, particularly overnight, something evident in the open and accessible nature of these spaces.Footnote 78 In contrast, macella were markets where smaller quantities of products – maybe purchased at the fora or originating from the countryside – were sold directly to consumers and where retailers would return to their shops on a daily basis. Ancient texts give only a little information on the management of these shops.Footnote 79 It is conceivable, however, that shopkeepers left behind not only tools and equipment – some perhaps owned by the city (for example, immovable items like counters) and some perhaps belonging to the lessee (for example, moveable objects like knives) – but also their day’s earnings (or possibly the city’s?). Grooved thresholds at Herdonia and Puteoli, for instance, indicate that individual shops were equipped with shutters and could be locked, complementing the lockable entrances of the market complex itself. This would have allowed tenants to close their shops at night, as they did with the tabernae outside these markets.Footnote 80

As the first enclosed market structure in Roman towns, the macellum not only enabled the oversight of increasingly frequent financial transactions – a subject to which I will return below – but also, and perhaps initially, addressed the physical security of coins themselves. As newly introduced high-value items, coins required protection both while in circulation and afterwards, when they needed secure storage of the kind that the macellum – with its typically controlled and lockable access points – was well suited to provide.

At Morgantina (Fig. 6A), the macellum, built soon after the introduction of Roman control in 211 BCE, is the earliest example with secure archaeological documentation.Footnote 81 Its construction may have been directly linked to the region’s early role in the proliferation of Roman coinage – Sicily was one of the first areas where Roman coins were minted, particularly during the Second Punic War.Footnote 82 Numismatic finds from the shops lining the macellum’s courtyard confirm the high circulation of bronze coins during the 2nd and 1st c. BCE.Footnote 83 We may hypothesize that access to the market was, therefore, deliberately limited: a single, narrow, elongated corridor in the western façade provided the only entrance. Cuttings in the threshold prove that it was once fitted with a double-leaf door with a secure locking mechanism.Footnote 84 Similar controlled entrances appear at other sites in Italy and the provinces, where macella frequently adopted enclosed designs with restricted entry points. At Herdonia (Fig. 6B), for example, the 2nd-c. CE macellum could only be accessed via a similarly narrow passage, and marks in the stone threshold there likewise suggest the presence of gates.Footnote 85 Although there are exceptions, particularly among more monumental markets with multiple entrances (e.g., Leptis Magna and Puteoli), the majority appear to reflect a preference for limited and easily controllable access. Many macella also featured stairs, implying that regulation of access was embedded in the building’s architectural design.Footnote 86 This arrangement prevented carts from entering, meaning goods likely had to be brought in manually, which may have supported closer monitoring and registration of items arriving into the market. These design features contrast with the openness of fora and may signal a clear move toward managing the activities of the market, what entered it, and the protection of its contents, from coins and tools to other equipment and goods.Footnote 87

Fig. 6. Architectural plans of the macella at Morgantina (A) and Herdonia (B), with their entrances marked (X). (After Sharp Reference Sharp and Maniscalco2015, fig. 2, 173 and De Ruyt Reference De Ruyt1983, fig. 32, 81.)

A study of the distribution of money chests (casseforti) in Pompeii found that one chest was located in a public area, inside a shop connected to the macellum.Footnote 88 The contents of this chest – over 1,100 bronze coins and just 35 small silver coins – are further proof of the widespread circulation of bronze coins in the urban monetary economy. The rarity of such equipment in tabernae, with only one chest discovered across Pompeii’s extensive landscape of shops, highlights the particular role of the macellum as a public marketplace requiring dedicated equipment for the oversight of daily transactions and secure storage of revenues. While coins in tabernae may have been stored in other ways, for instance, in cupboards or pots, the use of a specialized object like the money chest hints at a more officialized manner of money handling in the macellum.Footnote 89 In contrast to macella, there is a lack of data to suggest that municipal authorities oversaw the day-to-day business transactions within tabernae.Footnote 90 In those shops, individual tenants and shopkeepers may have borne responsibility for regulating commercial activities.Footnote 91 The macellum and its individual shops – even when leased out – remained municipal property and, as such, a matter of public concern, functioning as a structured venue where trade was organized within a city-administered framework.

If the macellum’s emergence in the Middle Republic was closely related to increasing monetization, its proliferation in the Imperial period should still be understood as, in part, a response to a continuing need to regulate coin-based transactions. By this time, coins had become ubiquitous in cities, but so too had practices of manipulation and forgery.Footnote 92 Market control measures may have curbed such abuses. Literary and epigraphic sources from the Empire affirm that local authorities and officials oversaw not only financial matters – like pricing and taxation – but also weighing equipment, product quality, and overall market order. Regulation was thus integral to the macellum’s role within the urban landscape. While this role is best documented for the Imperial period, the consistent emphasis on regulation implies that it was embedded in the macellum’s very concept. These marketplaces embodied the state’s effort to supervise and structure commerce – an incentive that underpinned their construction over time.Footnote 93 By the Imperial period, macella were increasingly funded through euergetism, enhancing the prestige of both the benefactor and the city.Footnote 94 Yet one cannot attribute the construction of these markets solely to a desire for prestige. While prestige may have been an ancillary benefit, it cannot, for instance, explain the choice to build a macellum before other structures that enhanced prestige, like theaters or bathhouses. Other purposes remained at play: the affordances built into the macellum’s design supported control, and if its forms retained similar affordances over time, then the actions it enabled in relation to increased supervision persisted.

City magistrates, aediles and agoranomoi, appear to have been crucial in managing the macella.Footnote 95 They oversaw the sale of food products, ensuring prices were correct and quality adequate, verified measurements, and prevented fraud related to weights and measures. In Rome, aediles had overseen public markets since the Republican period, but this role had weakened between the 1st and 2nd c. CE. Outside Rome, inscriptions attest to the continued duties of the aediles in the administration of the market.Footnote 96

The Lex Irnitana, a Flavian municipal law from Irni (Hispania), states that aediles were tasked with managing the market and “checking weights and measures.”Footnote 97 Inscriptions from various macella confirm that these magistrates supervised the use of measurement devices and even financed them, a point that is further discussed below.

The role of the aediles in monitoring prices is illustrated by a passage in Apuleius’s Metamorphoses that recounts an incident where an aedile was outraged by the high price of fish in the macellum.Footnote 98 Two additional sources signal this concern for maintaining fair prices in the market. A fragment from Diocletian’s Price Edict, displayed in the macellum of Aezani, emphasized the importance of “a fair and fixed price” in transactions.Footnote 99 Suetonius furthermore notes that, under Tiberius, the senate was tasked with annually regulating the annona macelli in Rome, a measure introduced after public complaints about fish prices.Footnote 100

As monetary transactions increased in cities, concerns about prices, profiteering, and inflation rose too, prompting stricter regulation of market practices. Price handling aligned with broader governmental efforts to curb excessive spending on foods. From the Middle Republic onwards, sumptuary laws in Rome targeted the consumption of costly goods such as meat and fish – commodities that were particularly susceptible to price manipulation and profiteering. It is unsurprising that these concerns were especially visible in the macellum, the principal urban venue for selling such goods.Footnote 101 Local responses to pricing challenges varied. In Magnesia, an inscription honored an agoranomos who either conducted or oversaw the sale of goods “below their cost price.”Footnote 102 One way it may have been possible for this urban official to do so was through the manipulation of taxes, which were commonly levied on products sold in the marketplace.

A taxation system in the macellum in Rome is implied by Pliny’s reference to the vectigal macelli, a market tax reportedly abolished under Nero due to public dissatisfaction.Footnote 103 Still, a 3rd-c. CE inscription from Rome mentions a procurator overseeing both grain supply and the Macellum Magnum.Footnote 104 While the evidence does not explicitly state his duties, it is plausible that they may have included oversight of the food supply and aspects of tax collection. Other inscriptions document similar roles elsewhere. In Placentia, the public slave Onesimus worked as vilicus, or market manager, in the macellum. Alongside his tasks of food inspection and measurement verification, he may also have managed tax collection.Footnote 105 In Lambaesis, two soldiers were appointed as agentes curam macelli, or caretakers of the macellum, and their duties may similarly have included overseeing tax collection.Footnote 106 Meanwhile, in Leptis Magna, a 1st-c. CE quattuorvir macelli funded a statue base dedicated to Liber Pater using 53 denarii of personal funds and 62 denarii from fines.Footnote 107 The inscription does not specify what these fines were for, but it is plausible that they derived from tax evasion or fraudulent practices, or violations involving selling low-quality goods or inaccurate measurements.

This evidence invites a reconsideration of the macellum’s broader urban role not just as a commercial structure but also as an instrument for tax collection. J. Patterson has previously argued that these markets were unlikely to have been built primarily to raise municipal revenue, proposing that their establishment instead reflects a desire to notably improve the cityscape.Footnote 108 While perhaps not the sole motive or initial incentive, two observations suggest that fiscal interests were a significant factor. First, taxes on macellum sales may have generated additional income for local governments, which could then be reinvested in civic infrastructure, maintenance, and public services. The importance of taxes, such as vectigalia, along with other municipal incomes, such as fines, in financing civic expenditure is supported by numerous ancient documents.Footnote 109 Second, the very structure of macella may have allowed for more efficient tax management. By converting agricultural surplus into coins, these markets helped city administrations meet their fiscal obligations to Rome. The involvement of local magistrates in constructing and restoring macella implies these spaces played a central role in financial governance.Footnote 110

Two inscriptions in particular prove that macella generated municipal income, at least in the case of rental revenues. A Flavian inscription, its origin uncertain, that refers to either the dedication of the macellum in Puteoli or the restoration of the market in Herculaneum mentions meritoria, or income-generating spaces within the market, possibly shops.Footnote 111 Considering the large number of shops encircling the courtyards of certain macella – as seen in Puteoli, for instance, where there were 36, and potentially as many again on the second floor – it is clear that renting out these units contributed substantially to urban revenue. Nicolas Tran posits that the vilicus at Placentia may have had duties similar to those of rural estate managers, including collecting rents.Footnote 112 A 1st-c. BCE inscription from Hirpinia records that six freedmen leased various spaces, including three tabernae, a passage arch, a porticoed area, and an open area, in return for paying a vectigal to the city. While the building is not named, the combination of these architectural features suggests they may have belonged to a macellum.Footnote 113

Additional evidence from Vienne includes a stone engraved with a floor plan resembling the Puteoli macellum (Fig. 7). Archaeologists believe it depicts the city’s macellum and that it was used to produce wax or lead prints for display in the market, informing market officials and prospective tenants which stalls were occupied and which were still available.Footnote 114

Fig. 7. Stone engraved on both sides, illustrating a layout resembling the Puteoli macellum. (Pelletier Reference Pelletier1966, fig. 55, 149.)

Interestingly, the two sides of the stone show different layouts, with varying numbers of divisions between rooms or sales areas. Rental configurations may have changed over time to accommodate demand. Additionally, variations in room size hint at differential rental rates depending on the size of the shop. Radiating walls around the courtyard indicate that the columns of the tholos were used to demarcate shop spaces. Temporary wooden stalls could be placed between these columns, increasing the number of rental units and, consequently, urban income.Footnote 115

In sum, these observations challenge the view that macella outside of Rome were purely built as initiatives of euergetism, public benefactions meant to showcase the generosity and boost the prestige of elites. While the pursuit of prestige played a role, city governments and elites may have seen macella as strategic investments that improved urban infrastructure but also strengthened municipal finances and control over the food trade. By investing in them, authorities could influence what was sold, under what conditions, and by whom.

Agricultural production and specialization

In a recent paper, Nicholas Purcell states that the creation of permanent retail facilities, referring specifically to the appearance of tabernae on the Forum Romanum, reflects an underlying economic transition to a new type of market, one where significant specialization in the collection and processing of products has occurred.Footnote 116 The Middle Republican period witnessed the emergence of large-scale, market-oriented production, as evidenced by a rural settlement boom, with the construction of villas and farms, in Rome’s suburbium from the 3rd c. BCE onwards.Footnote 117

This rural specialization not only focused on the surplus production of the so-called Roman cash-crops, grain, wine and olive oil, but was more diversified, and included other types of cultivation, such as the rearing of livestock and other animals, fish, and birds, often grouped by the Latin agronomists under the heading of pastio villatica.Footnote 118 This resulted in intensifying local and regional commercial trading networks, with farmstead and villa owners competing and seeking to maximize their profits by selling their produce in the nearest urban market. Existing scholarship has recognized that the emergence of macella in Rome closely mirrors this increased specialization in the Roman agricultural sector: these new types of popular foodstuffs, and the rationalized and profit-driven behavior of their producers when selling, required a new permanent marketplace.Footnote 119

One could thus argue that villa-estate owners had much to gain from financing the construction of a macellum. Three obvious advantages can be listed here. First, investing in a macellum provided the landowning elite with one fixed distribution channel for marketing the surplus produced on their estates and raising profits. Second, landowners who marketed their agricultural surpluses to urban centers demanded new control measures, which were offered by the supervised environment of the macellum. Third, the presence of a nearby macellum guaranteed revenues in the case of adversity encountered when selling products through other channels, over both short and long distances. As such, it was the perfect way to mitigate risk. Especially beyond Rome, where macella were regularly financed by private citizens,Footnote 120 the construction of a macellum might have been part of a well-reasoned economic strategy that involved both short- and longer-term planning: a macellum secured the existence of a stable market for selling agricultural surplus as well as fueling the urban demand for this type of produce, ensuring profit both in the present and in the (near) future.

Archaeological findings from Imperial North African Thugga and its countryside support this line of reasoning and demonstrate that the funding of marketplaces was not driven exclusively by prestige motivesFootnote 121 but might have involved complementary motives, such as strategic and lucrative investment. A comprehensive field survey of the rural landscapes surrounding this small hill-town has identified the landowners of several estates through epigraphic evidence, more specifically, funerary and boundary stones.Footnote 122 It clearly appears that several of these rural properties were owned by local families, whose members frequently acted as benefactors of public monuments in the city. The patronus pagi M. Licinius Rufus, for instance, funded the construction of the macellum sua pecunia in 54 CE.Footnote 123 He owned 250 ha of farmland about 4.5 km from Thugga, strategically positioned along the Via a Karthagine Thevestem, which provided a direct connection with the urban (market) center. His name is mentioned in a funerary inscription dedicated to his deceased mother, Licinia Attica, which was found reused in a Late Antique restoration of the estate.Footnote 124

Archaeological study of the landed area has identified remains related to the hydraulic infrastructure of the estate, including a water conduit that was carved in limestone blocks and collected streams of water from the Djebel Cheidi mountain.Footnote 125 M. Licinius Rufus’s motives for investing in a permanent urban marketplace were surely intertwined: a combination of practical concerns for marketing his agricultural products and an ambition to enhance his public image.

More than a century later, during the reign of Commodus, Q. Pacuvius Saturus and his wife, Nehania Victoria, paid more than 120,000 sesterces to dedicate a temple to Mercury and restore the aream macelli.Footnote 126 Their estate, located some 3.5 km from Thugga, revealed the remains of a cistern and fountain house, which archaeologists have attributed to the cultivation of irrigated fruits and vegetables.Footnote 127 However, the water supply could have served multiple functions related to the rearing of all types of animals. There is little doubt that the Pacuvii financed the urban embellishments using the profits earned from their agricultural business; their decision to invest these revenues in urban structures related to food processing and sales – note the relationship with the Mercury temple, often closely related to macella for the slaughtering of animals – was clearly aimed at maximizing profit efficiency. The relatively small size of their estate, estimated at 0.8 ha, demonstrates that local families with smaller amounts of land were also able to participate in these new economic behaviors.

Instead of fulfilling a need for a higher-status market suited to the trade of costly foodstuffs, the macellum was perhaps first and foremost indicative of economic profit and risk-reduction strategies related to agricultural production, even if some of the products sold might have been costlier than others.

Standardization

Financial innovations and the increase in agricultural production and specialization contributed to the growth of expansive and complex exchange networks across the Roman world. These developments encouraged several forms of standardization, notably the introduction of uniform weight and volume measurement systems aimed at streamlining trade, the implementation of which was adopted as part of Republican and Imperial administrative mechanisms.Footnote 128 Justin Jennings identifies standardization as a hallmark of globalization, facilitating interaction across boundaries.Footnote 129 Accordingly, in the Roman world, the adoption of universal metrological standards simplified extra-regional transactions and became almost mandatory for participation in those trade networks,Footnote 130 even if local variations and resistance to the standards and their use were widespread.Footnote 131

The implementation of a universal measurement system involved not only an abstract or intellectual dimension, with municipal inspectors ensuring it was being respected, but also, evidently, a material dimension, including physical tools such as weights, balances, and measuring tables. As previously mentioned, ancient texts highlight the responsibilities of aediles and agoranomoi in verifying the accuracy of weights and measures in macella. Epigraphic evidence from food markets across the Empire highlights the role of these magistrates as sponsors of weighing and measuring equipment, often placed in designated rooms in the macellum that are sporadically attested archaeologically.

Regarding this material dimension, the macellum – with its enclosed structure and ample space – not only enabled the official inspection of quantities but also offered secure areas for storing weighing instruments. The increasing dependence on standardized equipment necessitated new mechanisms for its protection and oversight, which the macellum’s built environment accommodated. While other urban settings, such as fora or specialized commercial zones like Ostia’s forum vinarium, also featured weights and measures and/or ponderaria, buildings for storing these instruments, the macellum stands out for its direct physical integration of retail activity and measurement infrastructure.Footnote 132 Buying, selling, and verification all took place within a single architectural space, an arrangement that implies a more systematic and rigorously enforceable form of oversight. By contrast, transactions in tabernae or at temporary market stalls on fora likely relied on separate mensa ponderaria stations, which parties had to visit to resolve disputes and verify measurements. This would make the use of such devices more optional and dependent on individual initiative rather than standard practice. For example, at Lucus Feroniae, the measuring table was located in the forum porticus, near shops with dolia and service counters, allowing – but not obligating – merchants to use it.Footnote 133 There is little evidence that local authorities instructed or obliged traders to systematically use these tools in such urban contexts. In macella, however, the presence of standardized measures and their oversight by aediles and market officials – whose duties explicitly included verifying (correct) use – implies a model where control was built in, expected, and an inevitable component of the retail process.

Again, most surviving evidence dates to the Imperial period, when efforts toward unified measurement standards intensified, particularly under Augustus, who imposed a uniform system. These initiatives encouraged local town magistrates to donate weighing and measuring tools.Footnote 134 But the origins of this regulatory impulse were Mid-Republican, when legal frameworks – particularly for wine and possibly dry goods – were first introduced.Footnote 135 This legal structure indicates an early institutional interest in commercial regulation, which in turn found expression in the organization of commercial spaces and the architectural development of the first Republican macella.

Donations of both pondera (weights) and mensae ponderaria (weighing and measuring tables with cavities for dry and liquid goods) by aediles, duumviri, and agoranomoi, are well attested in epigraphy.Footnote 136 An undated inscription from Histonium suggests that such offerings were often made once existing weights had become invalid. In this small town, two aediles installed new panaria, bread scales, in front of the marketplace.Footnote 137 A similar scenario is documented at Ostia, where two inscriptions record donations of weights to the macellum by members of the prominent Gamala family: one dating to the Late Republic or Early Empire, and the other to the mid-2nd c. CE.Footnote 138 Unfortunately, weighing tools are rarely preserved archaeologically and are usually limited to (fragments of) small weights or balances rather than complete measuring tables.Footnote 139

A few inscriptions show that macella were equipped with dedicated offices for storing weights and measures, known as ponderaria or zygostasia.Footnote 140 At Cuicul, L. Cosinius Primus paid 30,000 sesterces in the mid-2nd c. CE for the construction of a macellum cum columnis et statuis et ponderario et tholos.Footnote 141 Archaeologists have identified the ponderarium as a room south of the courtyard, where a limestone slab with 10 cavities (some still containing metal discs, remnants of the containers used for measuring) was discovered.Footnote 142 The presence of ponderaria has also been hypothesized in other North African macella, such as Hippo Regius, where two large stone blocks with cavities were found in a northern annex.Footnote 143

In Italy, Alba Fucens and Minturnae offer the most convincing evidence for weight rooms. At Minturnae, the macellum was furnished with an eastern vestibule. Oblong-shaped openings in the pavement represent the possible locations of two mensae ponderariae.Footnote 144 In the late 2nd or early 3rd c. CE, Alba Fucens added a vestibule and annexes to its macellum. In the largest of these rooms, the discovery of a stone weight beside a brick construction – interpreted as a platform for exhibiting weights – supports the hypothesis that this space functioned as a ponderarium.Footnote 145

Based on the architectural plans of numerous macella, which often include a range of rooms and annexes, commonly identified as shops, one can propose that ponderaria were more often installed than the material evidence currently documents. Significant gaps in the find assemblages of macella makes the identification of these facilities difficult. Yet, what is clear is that the abundance of easily manageable space in macella made them the perfect urban setting for storing and securing weights and measures. Where precisely these offices were placed in the market does not, however, appear to have been standardized. Recent archaeological findings from Aquincum, for example, demonstrate that the macellum’s central tholos was a closed-off structure that was largely inaccessible to customers, serving as an administrative office for the aediles overseeing weights and measures.Footnote 146

Moreover, local flexibility also appears in the measurement systems used, which did not always conform to the Roman standard. At Leptis Magna, for example, a decorated stone, possibly installed on a table, was carved with rectangles in three separate rows (Fig. 8). These have been identified as length measures based on the Punic cubit, the Roman-Attic foot, and the Ptolemaic cubit.

Fig. 8. Stone relief installed in the macellum of Leptis Magna, with depiction of three metrological units: the Punic cubit (top), the Roman-Attic foot (middle), and the Ptolemaic cubit (below) (https://www.manar-al-athar.ox.ac.uk/.)

The stone, dated to the 3rd c. CE, was most likely used as a measurement conversion tool, enabling trade interactions and transactions between citizens of diverse origins.Footnote 147 More than just a practical tool, in the case of Leptis Magna, the blending of measurement systems shows the intersection of and negotiation among the city’s unique local cultural identities.Footnote 148 Finally, the assemblage of weights recovered from the macellum at Iruña-Veleia indicates that some of them conformed to the official Roman metrological system, while others corresponded with local metrologies in use in this region and the broader province of Hispania. This further emphasizes the coexistence of different cultural and metrological practices in the Roman world.Footnote 149

Conclusion

The study presented here is the first to challenge the notion that the Roman macellum was a food market that emerged to fulfill elite demands empire-wide. I have demonstrated that the exclusive association of these markets with the elite is entirely grounded in literary texts, all originating from Rome, and in the long-held assumption that meat and fish were luxury food items available only to the highest ranks of Roman society. Until now, scholarship has never assessed this view against the archaeological evidence from macella across the Roman Empire. Using the most recent findings from archaeological faunal analysis in the Roman world, which prove that less affluent social classes had access to meat and fish of certain quality, preparation style, and age, I have attempted to dispute this claim by taking a closer look at the faunal assemblages from different macella. This has produced two major outcomes.

First, the archaeozoological records from macella are generally poorly understood, either because these materials have not been well preserved within the markets’ occupation layers or because zooarchaeological sampling and analysis has not been properly prioritized in excavation approaches, resulting in a substantial research lacuna. Second, the zooarchaeological assemblages from three macella in Roman Britain and Spain attest to locally diverse consumption patterns, where non-elites may have had access to at least some of the products for sale in the market. Even though this archaeological data comes from limited contexts, it calls for a reinterpretation of the macellum as urban symbol of elite consumption, one that centers on local material conditions rather than relying on Rome’s textual sources and imposing these onto local contexts without archaeological support.

In this reevaluation of the macellum, I have argued that this food market was an indicator of the increasing complexity and rationalization of the Roman economy. It follows that its development and construction need to be explained in light of deeper transformations within the Roman economy and the introduction of new economic behaviors. Financial innovations, agricultural production and specialization, and standardization were the motors driving a new mentality towards organizing the distribution and sale of foodstuffs in urban environments. This mentality, characterized by optimal control measures such as the supervision of sales, the use of coins and weights, as well as their physical protection, and profit strategies, was embodied and institutionalized in both the administrative and physical structure of the macellum.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which have greatly enriched the final version of this article. I am also grateful to Astrid Van Oyen for her thoughtful input, and to Marine Lépée for pointing me toward the archaeological evidence from Vienne.