Lower socioeconomic status (SES), which represents lower access to both financial and nonfinancial resources, is associated with poorer mental health outcomes, including internalizing, externalizing, and attention symptoms, as well as lower academic achievement (Peverill et al., Reference Peverill, Dirks, Narvaja, Herts, Comer and McLaughlin2021; Rakesh, Lee, et al., Reference Rakesh, Lee, Gaikwad and McLaughlin2025; Reiss, Reference Reiss2013; Sirin, Reference Sirin2005). Previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews have found that low SES is associated with increased risk for internalizing and externalizing problems (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Duffett-Leger, Levac, Watson and Young-Morris2013), as well as attention difficulties (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Ford, Williams and Russell2016). Further, meta-analyses indicate that low SES is associated with lower academic performance in children and adolescents (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Peng and Luo2020). However, the mechanisms underlying these associations remain unclear. Risk for psychopathology rises substantially during adolescence, a period characterized by profound social, psychological, and biological changes, including the onset of puberty (Scheiner et al., Reference Scheiner, Grashoff, Kleindienst and Buerger2022; Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2022). Rooted in life history theory, one suggestion is that early-life adversity, including socioeconomic disadvantage, may trigger a cascade of physiological changes that contribute to accelerated pubertal development, ultimately leading to elevated risk for mental health issues as well as lower academic performance (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg and Draper1991; Belsky, Reference Belsky2019; Ellis, Reference Ellis2004). However, longitudinal studies, which are needed to test whether pubertal development is a mechanism linking SES with children’s outcomes, are scarce. Understanding these developmental pathways is crucial for informing interventions aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of low SES on youth development.

From a cumulative risk perspective (Baker, Reference Baker, Cockerham, Dingwall and Quah2014; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013), low SES is associated with multiple co-occurring risks such as material hardship, family conflict, and exposure to neighborhood crime which together may contribute to risk for mental health problems and lower academic performance. Pubertal development – a biological process sensitive to environmental influences including chronic stress and resource scarcity – may serve as a key mechanism linking socioeconomic disadvantage to mental health and academic outcomes. Indeed, many factors can influence the rate of pubertal development, with environmental stressors playing a particularly significant role (de Angelis et al., Reference de Angelis, Garifalos, Mazzella, Menafra, Verde, Castoro, Simeoli, Pivonello, Colao, Pivonello, Foresta and Gianfrilli2021; Toppari & Juul, Reference Toppari and Juul2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Needham and Barr2005). According to life history theory, adversity including threat, deprivation, and economic hardship can accelerate pubertal development (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Steinberg and Draper1991; Ellis & Essex, Reference Ellis and Essex2007; Hill & Kaplan, Reference Hill and Kaplan1999). There is empirical support for this hypothesis: research by Ellis and Garber (Reference Ellis and Garber2000) and a meta-analysis by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Zhang and Sun2019) has shown that early-life stress can lead to an earlier age of menarche. Similarly, meta-analytic findings suggest that stress and adversity can lead to the early onset of puberty (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Rosen, Williams and McLaughlin2020; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Xu, Kondracki and Sun2024). These theories propose that chronic adversity shifts developmental trajectories toward earlier or faster maturation, increasing vulnerability to mental health difficulties (Rakesh et al., Reference Rakesh, Whittle, Sheridan and McLaughlin2023; Senger-Carpenter et al., Reference Senger-Carpenter, Seng, Herrenkohl, Marriott, Chen and Voepel-Lewis2024). In unpredictable or resource-scarce environments – including disadvantaged households and neighborhoods – accelerating reproductive readiness may enhance short-term fitness over long-term health, resulting in earlier pubertal timing and heightened risk for psychopathology. Indeed, low SES may act as a chronic stressor that accelerates pubertal maturation by altering the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Growing up in stressful environments, such as with financial strain or family conflict, can cause repeated HPA activation leading to dysregulation of cortisol release. High or irregular cortisol levels can then disrupt signaling between the HPA and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axes which may contribute to the earlier onset of puberty (Callaghan & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan and Tottenham2016; Shalev & Belsky, Reference Shalev and Belsky2016). Importantly, accelerated development is not only about when puberty begins but also how quickly it progresses (tempo). Because reproductive maturity is not reached at pubertal onset – for example, menarche precedes full reproductive maturity in girls – life history theory implies that adversity shapes both earlier initiation and faster progression through pubertal stages. In this view, both timing and tempo may serve the same adaptive function, underscoring the importance of considering both initial status and developmental progression when testing acceleration models (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Pham, Smith, Hidalgo-Lopez, Becker, Portengen, Heitzeg, Kaplan and Berenbaum2026).

Several theoretical models aim to explain how earlier pubertal development can contribute to risk for psychopathology and academic outcomes. Many frameworks (e.g., Angelo et al., Reference Angelo, DeFendis, Yau, Alves, Thompson, Xiang, Page and Luo2022; Ge & Natsuaki, Reference Ge and Natsuaki2009; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, Lambert and Natsuaki2014) highlight puberty as a sensitive period in which physical changes can trigger psychological instability and social disruption. Early maturing youth, for instance, may experience negative self-image or heightened self-consciousness which can undermine emotional well-being (Mendle et al., Reference Mendle, Turkheimer and Emery2007). They may also face social-behavioral risks, such as difficulties navigating peer relationships or reliance on maladaptive coping strategies. These risks appear to follow different temporal patterns by sex, with early maturation tending to bring quicker and longer-lasting risk of depression for girls but a slower, more gradual risk for boys (Mendle et al., Reference Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn and Graber2010).

Further, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain why puberty might influence educational outcomes. Hormonal changes can heighten arousal and emotional reactivity, making adolescents’ responses to teachers and parents less predictable (Marceau et al., Reference Marceau, Dorn and Susman2012). Early maturation may also push adolescents into adult-like roles before they are ready, or foster a self-concept in which they see themselves as “grown up,” increasing the likelihood of rejecting school norms and authority (Williams & Currie, Reference Williams and Currie2000). Finally, early physical maturation has been linked to greater involvement in risky behaviors such as smoking and drinking, which can compete with academic priorities and can further disrupt frontal cortical development and thus executive function and attention (Arım et al., Reference Arım, Tramonte, Shapka, Susan Dahinten and Douglas Willms2011; Crews et al., Reference Crews, He and Hodge2007). Pubertal timing may also influence attention and executive functioning. Biologically, rising sex hormones trigger synaptic reorganization in the prefrontal cortex and youth who mature earlier may temporarily experience imbalances in excitatory and inhibitory neurons, which may influence executive control (Alloy et al., Reference Alloy, Black, Young, Goldstein, Shapero, Stange, Boccia, Matt, Boland, Moore and Abramson2012; Selemon, Reference Selemon2013). Importantly, developmental cascade models highlight how experiences in one domain can set in motion a sequence of changes that accumulate across development. Within this framework, socioeconomic disadvantage may shape the course of pubertal development, which then influences adolescents’ emotional, social, and cognitive functioning. These linked processes can contribute to emerging differences in mental health and academic performance. Over time, these cascading effects can compound, leading to heightened risk for psychopathology and poorer academic outcomes (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Weissman and Bitrán2019).

Pubertal development can be described along different dimensions: pubertal status (an individual’s current stage of physical development during the process of puberty), timing (referring to the level of pubertal status relative to same age, same sex peers), and tempo (the rate of progression from onset to completion). Much of the existing literature linking SES to puberty focuses on pubertal status or timing at a single time point. However, puberty is a dynamic process that unfolds over several years, and pubertal tempo needs to be studied to investigate questions pertaining to the pace of biological development. This study focuses on both status and tempo to more fully capture individual differences in pubertal development trajectories.

A few studies have examined associations of low SES with pubertal timing and reported mixed results. For example, some work using large samples of adolescents showed both low household and neighborhood SES to be associated with the early onset of puberty, increasing the risk of future health problems (Arim et al., Reference Arim, Shapka, Dahinten and Willms2007; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mensah, Azzopardi, Patton and Wake2017). In contrast, a recent meta-analysis examining associations between SES and pubertal timing in males observed no association between SES and pubertal timing (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Norton and Rahman2018). Further, research on the association between SES and pubertal tempo remains limited and has also yielded inconsistent findings. Recent work showed that higher neighborhood SES predicted slower pubertal development (Thorpe & Klein, Reference Thorpe and Klein2022). In contrast, another longitudinal study found that those from higher SES families were less likely to have entered puberty by age 13, but more likely to go through puberty at a faster rate (Arim et al., Reference Arim, Shapka, Dahinten and Willms2007). In line with this, Oelkers and colleagues found that lower household SES was associated with a longer duration of puberty in overweight and obese girls (Oelkers et al., Reference Oelkers, Vogel, Kalenda, Surup, Körner, Kratzsch and Kiess2021). These inconsistencies highlight the need for further longitudinal research to clarify how SES influences the pace of pubertal development. In particular, there is a need for longitudinal studies that track pubertal tempo across multiple time points as well as a dearth of studies using male samples.

Further, SES is a multifaceted construct reflecting both disadvantage at the household and neighborhood level. Different measures of SES, such as family income and area-level disadvantage, are only moderately correlated with one another (Oakes & Rossi, Reference Oakes and Rossi2003; Rakesh et al., Reference Rakesh, Zalesky and Whittle2021, Reference Rakesh, Zalesky and Whittle2022), which suggests that they each may capture distinct aspects of the environment. Relying on single measures of SES may cause key information to be overlooked (Duncan & Magnuson, Reference Duncan and Magnuson2012); for instance, household SES can reflect nutrition and parental stress but may not account for neighborhood factors (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn2000). Indeed, neighborhood SES has been shown to play a crucial role in children’s outcomes over and above the household (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn2000). Neighborhood disadvantage may be associated with higher exposure to crime, lower access to green spaces, quality institutions, and supportive relationships, which can increase stress and dysregulate stress response systems (Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Burt, Gard, Burton, Clark, Klump and Hyde2022; Theall et al., Reference Theall, Shirtcliff, Dismukes, Wallace and Drury2017), ultimately contributing to accelerated pubertal development. As described above, although some studies, including recent cross sectional work using data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (Senger-Carpenter et al., Reference Senger-Carpenter, Seng, Herrenkohl, Marriott, Chen and Voepel-Lewis2024), have examined the role of family income in pubertal timing, to our knowledge, no longitudinal studies have directly tested hypotheses regarding the association of both family and neighborhood disadvantage with the pace of pubertal development. Studies that track pubertal status at multiple points of time to examine the role of family and neighborhood SES are needed.

In light of these gaps, the present study leveraged longitudinal data from the ABCD Study to investigate links between socioeconomic disadvantage, both at the household and neighborhood level, and pubertal development longitudinally. We examined two different aspects of pubertal development– pubertal status at baseline (hereafter referred to as pubertal status) and pubertal tempo (i.e., the rate in change of pubertal development over time). In addition, we also examined whether pubertal status and pubertal tempo mediate the association of SES with mental health and academic achievement during adolescence. Based on life history theory, we hypothesized that individuals from disadvantaged households and neighborhoods would have higher pubertal status at baseline. However, given limited longitudinal work, we refrained from making specific hypotheses about longitudinal development over time. Additionally, we expected that higher pubertal status would mediate the association of socioeconomic disadvantage with greater mental health problems and lower academic achievement.

Methods

Sample

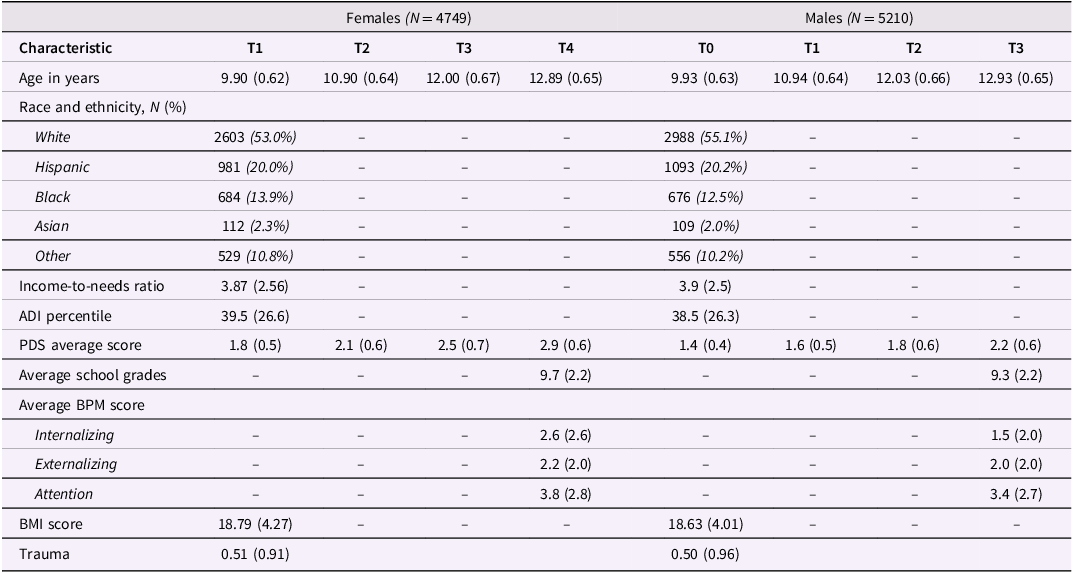

We used data from the ongoing ABCD Study® (release 5.0) (https://abcdstudy.org) with 11,868 participants aged 9–10 years at baseline. The ABCD study, a dataset spanning 21 data acquisition sites, assesses the psychological and neurobiological development from preadolescence into adulthood (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Cannonier, Conley, Cohen, Barch, Heitzeg, Soules, Teslovich, Dellarco, Garavan, Orr, Wager, Banich, Speer, Sutherland, Riedel, Dick, Bjork and Thomas2018). Assessments are conducted annually, with interim mental health assessments conducted every six months. Here, we used data collected from the first four annual time points: baseline (T1) at M age ± SD = 9.91 ± 0.63 years; year one (T2) at 10.92 ± 0.64 years; year two (T3) at 12.01 ± 0.67 years; and year three (T4) at 12.91 ± 0.65 years (year three was the last timepoint with complete data). Participants were excluded from the final dataset if they did not have complete data on the outcome variables at T4, were missing household or neighborhood SES data at T1, had no puberty data at any time point or were not biologically male or female at birth (i.e., intersex), resulting in a final sample consisting of 9,959 participants, with 5,210 (52.2%) males and 4,749 (47.8%) females. The sample was 54.3% White, 19.9% Hispanic, 13.1% Black, 2.2% Asian and 10.5% Other or Prefer not to respond. Demographic information can be found in Table 1. All parents or caregivers provided written informed consent, and assent was given by all children (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Bartsch, Conway, Decastro, Goldstein, Heeringa, Jernigan, Potter, Thompson and Zahs2018).

Table 1. Characteristics of the female and male study samples for all time points

Note: Descriptive Statistics for sample. Unless mentioned, values denote the mean and standard deviation (in brackets). ADI = area deprivation index; PDS = pubertal development scale; BPM = brief problem monitor; BMI = body mass index; N = sample size.

Measures

Pubertal development

Pubertal development was assessed at all time points using the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) to examine secondary sexual characteristics (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988). The PDS is a five-item measure that examines changes in height, skin, body hair, breast development and menstruation for females, and changes in height, skin, body hair, facial hair growth and deepening voice for males. Items were scored: (a) not started, (b) barely started, (c) underway and (d) seems complete, except for menstruation which is coded (a) not yet begun or (d) has begun. In line with recent recommendations, this study used parental reported data due to a significant number of “I don’t know” responses in the youth-reported data at baseline (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Pham, Smith, Hidalgo-Lopez, Becker, Portengen, Heitzeg, Kaplan and Berenbaum2026). At each wave (T1–T4), the PDS score was computed as the average of the five items. This yielded an average PDS score for each participant at each time point, which allowed us to model how PDS scores change across time. The PDS demonstrates satisfactory psychometric characteristics with an average alpha coefficient of 0.77, based on a concise set of five items. Additionally, it exhibits strong convergent validity, as evidenced by correlations ranging from 0.61 to 0.67 with physician ratings (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988). See Figures S2 and S3 for correlations among study variables.

Mental health

Mental health outcomes were assessed using the youth-reported Brief Problem Monitor (BPM) (Achenbach et al, Reference Achenbach, Mcconaughy, Ivanova and Rescorla2011) at T4. This measure captured internalizing (e.g., anxiety, depression), externalizing (e.g., aggression, conduct problems) and attention problems. Youth answered questions (e.g. “I act without stopping to think”) and then answers were scaled between 0–2 (ranging from 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = very true). As the distribution of the BPM-Y data was skewed, the Yeo-Johnson method (bestNormalise package in RStudio) was used to transform the data. BPM has good internal reliability (total Cronbach’s α = 0.85; internalizing Cronbach’s α = 0.84; externalizing Cronbach’s α = 0.74; attention problems Cronbach’s α = 0.78) (Rognstad et al., Reference Rognstad, Helland, Neumer, Baardstu and Kjøbli2022).

School grades

School achievement was assessed at T4 through youth-reported school grades in response to the question: “What grades did you receive in school last year?.” Grades were reported on a twelve-point scale (1 = A+; 2 = A; 3 = A- etc. up to 12 = F; N/A, Refuse to Answer or Not Answered). Self-reported school grades were used due to the strong concordance between them and those documented in school records (Kuncel et al., Reference Kuncel, Crede and Thomas2005). For ease of analysis, grades were reverse coded so that higher values indicate better performance (1 = F up to 12 = A+).

SES

Household income-to-needs ratio (INR). We operationalized household SES using the INR at baseline, which was calculated by dividing the total combined family income by the 2017 Federal Poverty Guidelines (Health and Human Services Department, 2017) for the respective family size. A value of one reflects being at the poverty threshold and higher INR values reflect higher SES.

Neighborhood Disadvantage. We operationalized neighborhood disadvantage at baseline using the census-tract level Area Deprivation Index (ADI) for the participant’s primary address, which is a composite index based on 17 socioeconomic indicators, such as neighborhood income, unemployment rate, education, and housing quality (Kind & Buckingham, Reference Kind and Buckingham2018). Higher ADI values indicate higher disadvantage.

Covariates

BMI was modeled as a covariate given that weight status is known to be associated with SES (McLaren, Reference McLaren2007), pubertal development (Kaplowitz et al., Reference Kaplowitz, Slora, Wasserman, Pedlow and Herman-Giddens2001), mental health (Biro & Wien, Reference Biro and Wien2010; Russell-Mayhew et al., Reference Russell-Mayhew, McVey, Bardick and Ireland2012), and academic achievement (Santana et al., Reference Santana, Hill, Azevedo, Gunnarsdottir and Prado2017). BMI was calculated by dividing the individual’s weight in pounds by their height in inches squared all multiplied by 703 due to the imperial system. Further, evidence regarding the association between low SES and pubertal development remains inconsistent (Oelkers et al., Reference Oelkers, Vogel, Kalenda, Surup, Körner, Kratzsch and Kiess2021; Stumper et al., Reference Stumper, Mac Giollabhui, Abramson and Alloy2020; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Norton and Rahman2018). In contrast, specific forms of adversity (e.g., trauma) have been more robustly linked to earlier pubertal development (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Rosen, Williams and McLaughlin2020, Reference Colich, Hanford, Weissman, Allen, Shirtcliff, Lengua, Sheridan and McLaughlin2022; Hallam et al., Reference Hallam, Bilsborough and de Courten2018; MacSweeney et al., Reference MacSweeney, Thomson, Soest, Tamnes and Rakesh2024). Given the well-established association between low SES and increased trauma exposure among adolescents (Evans, Reference Evans2004; Mock & Arai, Reference Mock and Arai2011), it has been suggested that SES may serve as a risk factor for trauma exposure rather than having a direct association with pubertal development (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Rosen, Williams and McLaughlin2020). Therefore, to examine whether SES was associated with pubertal development and mental health and school achievement over and above trauma exposure, we included trauma exposure as a covariate in the LMMs and mediation models. Trauma was operationalized using the trauma exposure items from the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (KSADS) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) module, which index participants’ exposure to traumatic events (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Puig-Antich, Hirsch, Paez, Ambrosini, Tabrizi and Davies1985). The sum score ranged from 0 to17, with higher scores indicating exposure to a greater number of event types (See the Supplement for the list of items). Models that did not adjust for the effects of BMI or trauma are reported in the Supplementary Material (Tables S2–S4). In addition, we controlled for prior adolescent mental health and academic achievement in sensitivity analyses. We operationalized youth mental health at baseline using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Because youth self-reports were first collected at six months post-baseline, we used parent-reported CBCL scores at baseline to account for preexisting mental health. Further, we accounted for prior academic achievement at T3, which was the first time point at which data on school grades were acquired.

Statistical analysis

This statistical analysis used RStudio (R version 4.1.1). Due to sexual dimorphism in pubertal development at this age (Mendle et al., Reference Mendle, Beltz, Carter and Dorn2019), and in accordance with recent recommendations (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Pham, Smith, Hidalgo-Lopez, Becker, Portengen, Heitzeg, Kaplan and Berenbaum2026), analyses were conducted in males and females separately. For model results, we report standardized regression coefficient (β) and its standard error (SE) for each predictor, which allow direct interpretation of the effect size.

Associations between SES and pubertal status and tempo

We investigated the association of household and neighborhood SES with pubertal status and tempo using linear mixed-effects models (LMMs). Models were conducted using the lme4 package in R (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), and P-values were obtained using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). LMMs are well-suited for longitudinal analyses because they allow for the utilization of all available data, including participants with data at only one time point (Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Hedeker and DuToit2010). Participants with missing SES data at T1 were not included in analyses. Analyses used PDS scores as a time-varying dependent variable to test the association between SES and pubertal development. To examine whether SES influences change in PDS scores over time, we modeled an interaction term between baseline SES (i.e., INR and ADI) and the main effect of age. Age was included as a predictor in the longitudinal model to estimate the average change in PDS scores over time (i.e., pubertal tempo) across all individuals. This captured the overall pubertal developmental trend across several timepoints, while taking into account the variation across participants in the ages when the PDS was completed. In this model, given that age was centered using the mean age baseline, the main effect of SES reflected its association with pubertal status at baseline. The interaction term between SES and age assessed whether the estimated change in PDS scores over time (tempo) was different at different levels of SES. Analyses also used time-invariant measures for BMI and trauma at baseline, and random effects for site, family, and participant ID. All variables were standardized except age (which was centered based on the mean age at baseline). False discovery rate (FDR) was applied to account for multiple comparisons (pFDR < 0.05) (Benjamini & Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995) across both puberty variables (pubertal status and tempo) for two SES variables (INR and ADI), resulting in a total of four comparisons per sex.

Pubertal status and tempo as mediators of the relationship between SES and mental health and academic achievement

To investigate whether pubertal status and/or tempo mediated the relationship between SES at T1 and mental health and academic achievement at T4, we conducted mediation analysis using SEM in the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012). We operationalized pubertal status at baseline and pubertal tempo using the intercept and slope, respectively, derived from multilevel models in which PDS scores were predicted by age (Figure S1). Models with and without the random intercept for family ID were compared to determine the best-fitting model. Model fit was evaluated using AIC and BIC values, and the random effects (intercepts and slopes) from the selected model were subsequently extracted to represent pubertal status at baseline and tempo (rate of change). If the random intercepts and slopes were highly correlated (>0.90), as was the case with male data, we specified a model with uncorrelated random effects. Using this approach, for significant results from the preceding LMMs, the mediation analyses used T1 SES as the predictor, pubertal status at baseline and pubertal tempo as mediators (included in the same model), and T4 mental health and T4 academic achievement were modeled as the outcome (see Figure 1). We estimated separate models for each SES (INR/ADI) variable and each outcome (internalizing, externalizing, and attention problem and academic achievement). We adjusted for covariates including trauma exposure, BMI, and age. To determine whether findings were specific to neighborhood or household disadvantage, we also covaried for ADI in INR models, and vice versa. We controlled for multiple comparisons using the FDR across all indirect effects tested (2 SES variables, 2 mediators, and 4 outcome variables) within each sex. This resulted in correcting for 16 indirect effects in females and 12 indirect effects in males (as associations between ADI and pubertal tempo were nonsignificant in males).

Figure 1. Mediation model showing all pathways. INR = income-to-needs ratio; ADI = area deprivation index; PDS = pubertal development scale.

Sensitivity analyses

In addition, to examine whether effects existed over and above prior difficulties, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the same mediation framework as above and additionally adjusted for prior mental health and academic outcomes. Since the BPM was not included at baseline, we adjusted for parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist scores for externalizing, internalizing, and attention problems. In addition, due to the absence of baseline academic performance data, academic scores from the 2-year follow-up were included (which was the first time point at which data on academic performance were collected). Results for sensitivity analyses were provided in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Relationship between SES and pubertal development

Associations between household income-to-needs and pubertal status and tempo

Lower INR was significantly associated with a higher pubertal status at baseline for females (β = –0.08 [SE = 0.01], t = –6.50, pFDR < .001; Figure 2A) and males (β = –0.06 [SE = 0.02], t = –4.69, pFDR < .001; Figure 2B). Additionally, a lower INR was associated with a slower tempo (i.e., lower increases in PDS scores over time) for females (β = < 0.01 [SE < 0.01], t = 4.12, pFDR < .001; Figure 2A) and males (β = < 0.01 [SE = < 0.01], t = 2.97, pFDR = .004; Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Relationship between pubertal development and household income. note: developmental trajectories of raw PDS scores in relation to household income (measured by standardized INR values, mean ± 1 SD for visualization) in adolescence for A) females (orange) and B) males (blue) in adolescence.

Associations between neighborhood disadvantage and pubertal status and tempo

Higher neighborhood disadvantage was significantly associated with a higher pubertal status at baseline in females (β = 0.10 [SE = 0.01], t = 7.01, pFDR < .001; Figure 3A) and males (β = 0.08 [SE = 0.01], t = 6.32, pFDR < .001; Figure 3B). Higher neighborhood disadvantage was significantly associated with a slower tempo (i.e., less increase in PDS scores over time) in females (β = –0.002 [SE < 0.01], t = -4.875, pFDR < .001; Figure 3A) but not males (β = –0.0003 [SE = < 0.01], t = –0.907, pFDR = .985; Figure 3B). Full results are provided in the Supplemental Material (Table S1).

Figure 3. Relationship between pubertal development and neighborhood disadvantage. note: developmental trajectories of raw PDS scores in relation to neighborhood disadvantage (measured by standardized ADI values, mean ± 1 SD for visualization) in A) females (orange) and B) males (blue) in adolescence.

Pubertal development as a mediator of the relationship between SES and mental health and academic achievement

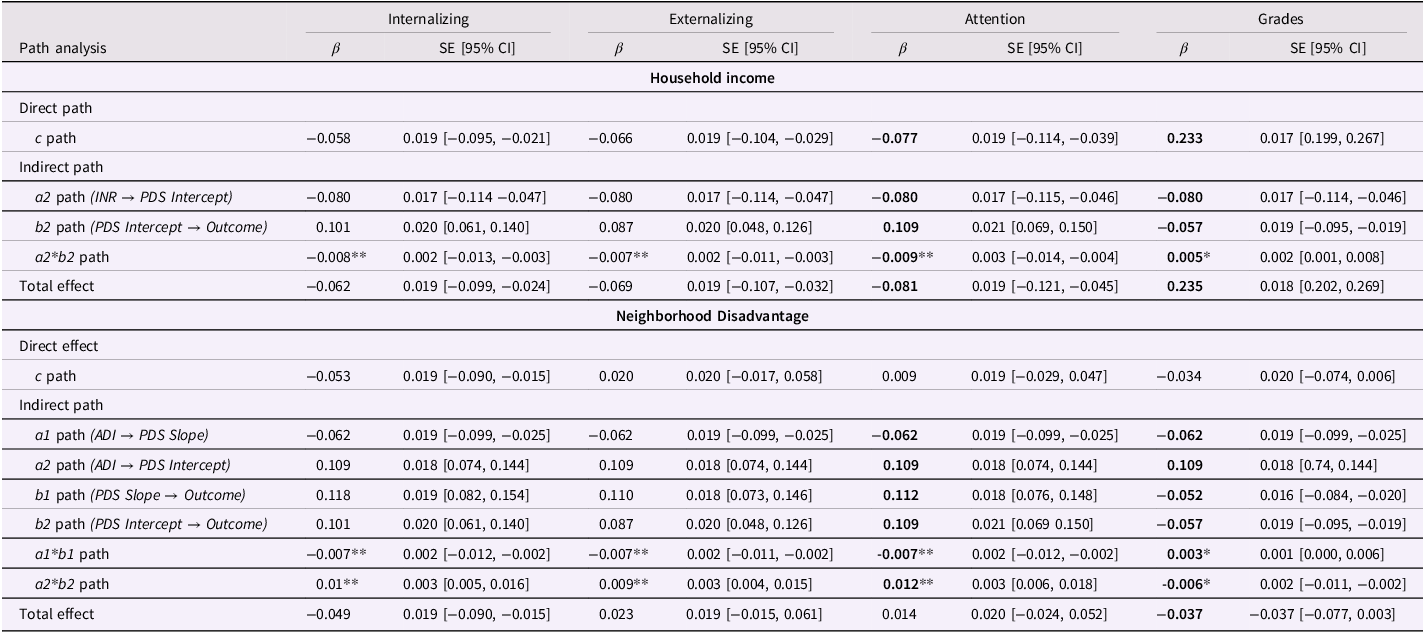

Household income-to-needs

Overall, in females, there was a significant total effect: higher INR was associated with lower internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems, as well as increased school grades (Table 2). We found that higher pubertal status at baseline significantly mediated the relationship between lower INR (indicating lower SES) and higher internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems (Table 2). In addition, higher pubertal status at baseline mediated the relationship between lower INR and lower school grades. All results remained significant when adjusting for the outcome at prior time points (see Table S7). Additionally, we observed significant direct effects of lower INR on increased internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems, as well as increased school grades (Table 2). No indirect effects were significant for pubertal status at baseline in males. While low INR was linked to slower pubertal tempo (i.e., change in PDS scores over time), it did not mediate associations between SES and outcomes (see Table S6).

Table 2. Results of analysis examining puberty as a mediator in the association between SES and mental health/academic outcomes for females

Notes: This table only reports significant associations; nonsignificant results have been reported in the supplement. Independent variables: income-to-needs ratio (INR) and area deprivation index (ADI). Dependent variables: mental health (internalizing, externalizing and attention problems) and school grades. Mediators: pubertal developmental scale (PDS) scores at baseline and PDS scores over time (extracted intercepts and slopes). 1 = slope pathway, 2 = intercept pathway, β = standardized coefficient, SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval. P-values for indirect effects (a1*b1 and a2*b2) were readjusted using false discovery rate. Bold indicates significance at the p < .05 level, uncorrected. * indicates significance at the .01 level for indirect effects (i.e., pFDR < .05); **indicates significance at the .01 level (i.e., pFDR < .01); *** indicates significance at the .001 level (i.e., pFDR < .001). Nonsignificant results are provided in the Supplemental Material (Table S5).

Neighborhood disadvantage

In females, there was a significant total effect for internalizing problems and grades: higher neighborhood disadvantage was associated with lower internalizing problems and lower grades (Table 2). We found that higher pubertal status at baseline significantly mediated the association between higher neighborhood disadvantage and greater internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems (Table 2), despite the absence of significant total effects for externalizing and attention problems. Higher pubertal status at baseline also mediated the relationship between higher ADI and lower school grades (Table 2). In males, pubertal status at baseline did not significantly mediate any relationships (see Table S6).

In females, higher neighborhood disadvantage was associated with slower pubertal tempo (i.e., slower change in PDS scores over time), which was in turn associated with lower mental health symptoms and higher school grades. The indirect effect was significant for all three mental health domains (internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and attention problems) and school grades (Table 2). These results suggest that slower pubertal tempo partially attenuated the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and outcomes, and in the case of internalizing problems, reversed the association observed through earlier pubertal timing.

Additionally, we found a significant direct effect of higher neighborhood disadvantage on decreased internalizing problems, but not on externalizing problems, attention problems, or academic performance (Table 2). All results remained significant when adjusting for the outcome at prior time points (see Table S7 for model output). All nonsignificant results have been reported in the Supplement (Tables S5–S6).

Discussion

This study explored the role of pubertal development in the relationship of household and neighborhood SES with mental health and academic achievement during early adolescence using longitudinal data. We found that higher household disadvantage was associated with higher pubertal status at baseline and slower tempo in both females and males. Higher neighborhood disadvantage was associated with higher pubertal status in both males and females, and slower tempo in females. In addition, higher pubertal status at baseline mediated the relationship of low household income and neighborhood disadvantage with higher mental health problems and lower school grades in females, but not males. Further, slower pubertal tempo attenuated the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and mental health problems and school grades in females, though this pattern may partly reflect ceiling effects, as adolescents who were more developed at baseline had less remaining development to complete.

Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that lower household income, over and above effects of trauma exposure, was associated with a higher pubertal status at baseline in both males and females. Our finding that low SES is associated with higher pubertal status is consistent with life history theory and the notion that exposure to stressors contributes to earlier pubertal development (Belsky, Reference Belsky2019; Colich et al., Reference Colich, Rosen, Williams and McLaughlin2020; Gluckman & Hanson, Reference Gluckman and Hanson2006; Senger-Carpenter et al., Reference Senger-Carpenter, Seng, Herrenkohl, Marriott, Chen and Voepel-Lewis2024). However, our findings stand in contrast to a meta-analysis of studies in males that found no significant associations between family SES and the timing of puberty (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Norton and Rahman2018). One potential reason for the discrepancy in findings may be in the wide age range in the studies included in the meta-analysis and how household SES was operationalized across studies. Our study used the income-to-needs ratio, a direct measure of financial SES, whereas other studies employed a range of other household SES indicators, including father absence and parental education. This heterogeneity in the operationalization of SES may have contributed to the null results observed in Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Norton and Rahman2018). Low household income can expose youth to chronic stress, including financial strain, family conflict, and childhood maltreatment (Evans, Reference Evans2004; Suglia et al., Reference Suglia, Saelee, Guzmán, Elsenburg, Clark, Link and Koenen2022). These early-life stressors can disrupt cortisol regulation through their influence on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Consten et al., Reference Consten, Keuning, Bogerd, Zandbergen, Lambert, Komen and Goos2002), which plays a crucial role in the body’s stress response. Dysregulation of the HPA axis as a result of chronic stress has been associated with accelerated biological aging (Kircanski et al., Reference Kircanski, Sisk, Ho, Humphreys, King, Colich, Ordaz and Gotlib2019), and may influence pubertal development. In such environments, the body may adapt by prioritizing earlier maturation as a survival strategy, enhancing reproductive success under perceived threat. However, these pathways remain to be directly investigated – a key direction for future work.

Similarly, and consistent with our hypotheses, we found that higher neighborhood disadvantage was associated with a more advanced pubertal status at baseline in both males and females. Neighborhood disadvantage, like with household disadvantage, may contribute to chronic stress due to factors such as exposure to violence and lower access to quality healthcare and schools, which could lead to activation of the HPA axis and increased cortisol levels, as well as low-grade inflammation (Hackman et al., Reference Hackman, Betancourt, Brodsky, Hurt and Farah2012; Hostinar et al., Reference Hostinar, Ross, Chen and Miller2015), ultimately contributing to earlier pubertal onset during late childhood (Grob & Zacharin, Reference Grob and Zacharin2020; Saxbe et al., Reference Saxbe, Negriff, Susman and Trickett2015; Keita et al., Reference Keita, Casazza, Thomas and Fernandez2009 ; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Frongillo, Black, Dong, Fall, Lampl, Liese, Naguib, Prentice, Rochat, Stephensen, Tinago, Ward, Wrottesley and Patton2022; Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Bellani, Karatsoreos, Chhua, Vernov, Conrad and McEwen2006). We also found sex differences in the association between neighborhood SES and pubertal tempo: neighborhood disadvantage was associated with a slower tempo (discussed in more detail in subsequent sections) in females but not in males. Given that females typically begin pubertal development earlier than males (Marshall & Tanner, Reference Marshall and Tanner1969, Reference Marshall and Tanner1970), the observed sex differences in our study may partly reflect insufficient data for males at more advanced developmental stages. Indeed, only a fraction of males had begun puberty (PDS = ∼2) by T3 and T4.

Further, we found that while low household and neighborhood SES were associated with higher pubertal status at baseline, they were associated with a slower tempo over time. These findings are consistent with other longitudinal work showing links between high SES and faster pubertal tempo (Arim et al., Reference Arim, Shapka, Dahinten and Willms2007; Oelkers et al., Reference Oelkers, Vogel, Kalenda, Surup, Körner, Kratzsch and Kiess2021) as well as recent work showing trauma exposure to be associated with higher pubertal status at baseline but a slower tempo over time (MacSweeney et al., Reference MacSweeney, Thomson, Soest, Tamnes and Rakesh2024). It is possible that youth from low-SES backgrounds may have already experienced a rapid phase of development (i.e., faster tempo) prior to the baseline wave of the ABCD study (i.e., before 9–10 years), as evidenced by higher pubertal status at baseline. Since all adolescents go through the same stages of puberty, the faster tempo seen in higher SES youth over subsequent timepoints could reflect a more contracted duration of progress through these pubertal stages. Our findings suggest that younger samples (ages 7 onwards) may be needed to examine the association between SES and faster pubertal tempo – an important avenue for future research. Alternatively, this pattern may partly reflect methodological artifacts. As noted in previous work (Marceau et al., Reference Marceau, Ram, Houts, Grimm and Susman2011; Mendle et al., Reference Mendle, Beltz, Carter and Dorn2019), analytic approaches such as mixed-effects or growth curve models can introduce dependencies between timing and tempo, whereby early developers appear to mature more slowly simply because they have less room for further change. Future research should use broader age ranges that start earlier in development and more frequent follow-ups to better capture developmental variability and avoid conflating status with tempo.

We found that higher pubertal status at baseline mediated the relationship between lower SES and both lower school grades and higher mental health problems in females. While associations were in similar directions, it is possible that early puberty may be associated with mental health and academic achievement through at least partially distinct pathways. For example, recent animal studies have demonstrated that an early increase in pubertal hormones may influence the regulation of neural circuits in the frontal cortex and hippocampus (Laube & Fuhrmann, Reference Laube and Fuhrmann2020; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Lew, Albaugh, Botteron, Hudziak, Fonov, Collins, Ducharme and McCracken2017; Piekarski et al., Reference Piekarski, Boivin and Wilbrecht2017), potentially contributing to differences in cognitive skills, including executive function. This may explain the observed links between low SES, early puberty, and lower grades, as well as attention problems.

Additionally, it is possible that early puberty is associated with internalizing and externalizing problems due to the differential development of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex during adolescence (Shulman et al., Reference Shulman, Smith, Silva, Icenogle, Duell, Chein and Steinberg2016). Given that pubertal hormones are closely related to the functional maturation of the limbic system (Arain et al., Reference Arain, Haque, Johal, Mathur, Nel, Rais, Sandhu and Sharma2013), earlier pubertal maturation may contribute to faster development of limbic regions involved in emotional reactivity and stress processing such as the amygdala and hippocampus (Crone & Dahl, Reference Crone and Dahl2012). As a result, early maturing adolescents may be more sensitive to social evaluation and interpersonal stressors, increasing their vulnerability to internalizing problems. Further, the developmental mismatch between the limbic and prefrontal systems, which develop more gradually across adolescence, may increase vulnerability to externalizing problems, including aggression and rule-breaking behaviors (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Goddings, Clasen, Giedd and Blakemore2014; Shulman et al., Reference Shulman, Smith, Silva, Icenogle, Duell, Chein and Steinberg2016).

Further, slower pubertal tempo attenuated the relationship between lower neighborhood SES and higher mental health problems and lower academic performance. Slower tempo, which reflects an extended overall course of development, may represent a compensatory process following earlier pubertal timing (Gamble, Reference Gamble2017). A longer developmental period may allow for more gradual adaptation to hormonal changes and social challenges, thereby reducing stress and mitigating vulnerability to psychopathology. Importantly, however, given that low SES is associated with higher pubertal status at baseline, had we measured pubertal tempo prior to age nine, it is plausible that faster pubertal development at earlier stages would have mediated the link between low SES and elevated mental health problems. Our findings suggest that the timing of pubertal assessments is crucial when investigating mental health outcomes among children and adolescents. Further, alongside data spanning late childhood to adolescence, nonlinear modeling approaches will be necessary to capture these nuances (i.e., rapid increases followed by a protracted pace of development among low SES youth).

Importantly, neither pubertal status nor tempo mediated any associations in males. Our findings are consistent with Stumper & Alloy (Reference Stumper and Alloy2023), whose systematic review indicated significant associations between earlier pubertal stage and higher depression rates among girls but not boys. According to the contextual-amplification model, effects of earlier maturation can be amplified or exacerbated by environmental risk factors, such as low SES, family conflict, or lack of emotional support (Rudolph & Troop-Gordon, Reference Rudolph and Troop-Gordon2010; Skoog & Stattin, Reference Skoog and Stattin2014). Girls from low SES backgrounds may face restrictive gender norms and have access to lower levels of emotional support, making it harder to cope with new social roles and body-related changes (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Piera Pi-Sunyer, Moses-Payne, Goddings, Speyer, Kuyken, Dalgleish and Blakemore2024; Mercader-Yus et al., Reference Mercader-Yus, Neipp-López, Gómez-Méndez, Vargas-Torcal, Gelves-Ospina, Puerta-Morales, León-Jacobus, Cantillo-Pacheco and Mancera-Sarmiento2018; Tobin-Richards et al., Reference Tobin-Richards, Boxer, Petersen, Brooks-Gunn and Petersen1983). These factors may amplify the emotional consequences of SES-related differences in pubertal development, increasing risk for internalizing symptoms among girls. Boys, by contrast, tend to receive social reinforcement for pubertal changes (e.g., strength, independence), which may buffer against such effects (Tobin-Richards et al., Reference Tobin-Richards, Boxer, Petersen, Brooks-Gunn and Petersen1983).

The current study benefits from a longitudinal design and large sample. Nonetheless, results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. One, the observational nature of this study precludes establishing causal relationships due to residual confounding. Future work should leverage causal inference methods such as marginal structural models and g-estimation to address questions about the links between disadvantage and pubertal outcomes. Two, greater attrition from low SES families in the ABCD study (Feldstein Ewing et al., Reference Feldstein Ewing, Dash, Thompson, Reuter, Diaz, Anokhin, Chang, Cottler, Dowling, LeBlanc, Zucker, Tapert, Brown and Garavan2022; Rakesh, Flournoy, et al., Reference Rakesh, Flournoy and McLaughlin2025) may have impacted the representativeness of the sample, potentially influencing our results. Three, while socio-demographically diverse, the American sample leveraged in the present study limits the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Future studies should strive to implement strategies to minimize attrition, especially among low SES participants, or expand to include diverse populations from different cultural contexts to ensure a more representative sample. Four, this study was limited to examining linear associations from a limited number of time points. As the ABCD study continues to collect more data, future research should incorporate additional assessments of pubertal development, mental health, and academic outcomes. Employing growth modeling techniques (e.g., latent growth modeling and cross lagged panel models) or nonlinear approaches would help better capture complex pubertal developmental trajectories and links with outcomes. Five, we simplified the random effects structure for male models by specifying a model with uncorrelated random effects due to model convergence issues. While this approach allowed models to be estimated, future releases of the ABCD data – when males are more advanced in pubertal development and additional timepoints are available – will enable more precise estimation of intercept–slope covariance and further investigation of potential associations between pubertal development, SES and outcomes in males. Finally, a limited age range was used spanning early to mid-adolescence, which captures a narrow window of pubertal development. To better understand the role of SES in pubertal development, future research would benefit from collecting data starting earlier in childhood and examining effects from late childhood through late adolescence.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that pubertal development is a pathway linking household and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage to mental health and academic outcomes in adolescent females. Our findings underscore the importance of considering both household and neighborhood environments when studying SES and adolescent development. These results point to puberty as a sensitive period during which socioeconomic contexts may exert lasting influence. Future research should examine the processes through which disadvantage accelerates or alters pubertal development and assess implications for intervention.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579426101187.

Data availability statement

The ABCD study data used in this project are publicly available (https://abcdstudy.org/). Access to the data is granted to qualified researchers via a data use agreement. For further information on how to obtain access to this dataset, visit the NIH Brain Development Cohorts data sharing platform (https://www.nbdc-datahub.org/).

Acknowledgements

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ABCD Study (https://abcdstudy.org) held in the NDA. This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children ages 9–10 years old and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123 and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, the US federal government or ABCD consortium investigators.

Author contributions

K.F. and Q.L. are joint first authors.

Funding statement

D.R. acknowledges support from a Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behaviour Research Foundation (32908) and a New Investigator Research Grant from the UKRI Medical Research Council (MR/Z506667/1).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Preregistration statement

This study was not preregistered. All hypotheses and analytic decisions were guided by an established theoretical framework and specified prior to data analysis.

Availability of code

The analysis code is available upon request.

Availability of methods/materials

The methods and materials used in this study are fully detailed within the manuscript.

AI statement

AI tools were used solely to assist with language clarity and readability. No AI tools were used in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or the generation of scientific content. All substantive content, analytic decisions, interpretations, and conclusions were made solely by the authors.