1. Introduction

The occurrence of ‘corner eddies’, a sequence of vortices of decreasing size and strength in the vicinity of a sharp edge, was initially revealed and analysed by Moffatt in the 1960s, in the context of continuum incompressible flows (Moffatt Reference Moffatt1964a , Reference Moffattb ). Ever since, follow-up continuum-flow investigations have been carried out (see Shankar & Deshpande (Reference Shankar and Deshpande2000) and works cited therein), considering the two-dimensional wedge-confined problem, as well as the three-dimensional cone-edge configuration. Both free-surface (external-flow-induced) and lid-driven set-ups have been examined, and the impacts of solid-wall dynamics and thermodynamic conditions have been investigated in detail, to examine their effect on the developed flow field.

While numerous works have focused on the problem at continuum-flow conditions, relatively few studies have analysed the effect of continuum breakdown on the appearance of corner recirculation. Considering lid-driven set-ups containing rarefied gases, the rectangle-shape hole geometry has been examined in several contributions (e.g. Qian & Wang Reference Qian and Wang2005; Naris & Valougeorgis Reference Naris and Valougeorgis2005; Kandemir & Kaya Reference Kandemir and Kaya2012; Wu, Reese & Zhang Reference Wu, Reese and Zhang2014; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Su, Zhu and Zhang2019; Nabapure & Murthy Reference Nabapure and R.C.Murthy2021), examining the impacts of cavity aspect ratio and surface conditions on vortical flow formation. Non-rectangular configurations, including circular (Zhu, Roohi & Ebrahimi Reference Zhu, Roohi and Ebrahimi2023) and other cavity shapes (Zakeri & Roohi Reference Zakeri and Roohi2021), have been similarly studied. In particular, triangular-cavity flows were considered (Roohi, Sahabi & Bagherzadeh Reference Roohi, Sahabi and Bagherzadeh2018), including a case where the cavity walls are stationary and fluid motion is induced through non-homogeneous wall temperatures (Mousivand & Roohi Reference Mousivand and Roohi2022).

In a separate list of studies, non-lid-driven (i.e. open) cavity flows, where fluid motion inside a pore is excited by external shear flow, were considered. Such set-ups are commonly encountered in grooved-wall geometries. Primarily, these are found in microchannel set-ups, where non-regular wall patterns are ubiquitous, as well as in outer-space flight vehicles, where design constraints result in non-smooth surface structures. In the former, flows passing in rough microchannels have been analysed, to study the impact of wall irregularities on channel permeability and cavity vortex formation (Tan, Kang & Wang Reference Tan, Kang and Wang2015; Rovenskaya & Croce Reference Rovenskaya and Croce2018; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Liu, Xu, Shan and Li2019; Sazhin Reference Sazhin2020). In the latter context of high-altitude flight, the effect of surface grooves on the vehicle overall aerodynamic efficiency (and, in particular, the drag force) has been examined (Guo & Luo Reference Guo and Luo2018; Nabapure, Singh & Kalluri Reference Nabapure, Singh and Kalluri2023; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Zhao, Su and Wu2023). Existing works have considered a variety of open-cavity configurations, including rectangular, semicircle and triangular (‘V-shape’) geometries, and examined a wide scope of rarefaction rates, encompassing near-continuum- to near-free-molecular-flow regimes (Guo & Luo Reference Guo and Luo2018; Jin et al. Reference Jin, Cheng, Wang and Wang2023; Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Cai, Chen, Yuan, He and Liu2023; Ghamartale, Tsai & Tang Reference Ghamartale, Tsai and Tang2025). In this respect, a focus on the high-Knudsen-number limit is of particular interest, as it plays a vital role in high-altitude aerospace and microfluidic contexts, yet is relatively less explored compared with continuum-based studies. Evidently, the breakdown of continuum assumptions does not allow the application of conventional vortex analyses to study the problems in hand. A rigorous study of the generation of vortical flows at highly rarefied conditions, based on gas kinetic theory, is therefore of evident significance.

Almost entirely, all works studying rarefied gas cavity flows rely on numerical simulations. The prevailing scheme of solution applied is the direct simulation Monte Carlo (DSMC) method (Bird Reference Bird1994), which is routinely used for the description of rarefied gas flows. While DSMC calculations are known to converge to the solution of the Boltzmann kinetic equation (Wagner Reference Wagner1992), they require considerable computational efforts and lack the insight that may be gained through rigorous analyses. In relevance to the present topic, corner flow DSMC calculations are particularly challenging, as low flow speeds are expected, resulting in an inevitable decrease in the signal-to-noise ratio. This prohibits a detailed description of vortex formation near sharp corners, which is the main focus in corner flow studies.

In view of the above, the objective of the present work is to investigate the formation of corner circulation in the highly rarefied gas-flow regime. To this end, we consider the high-Knudsen-number limit of the two-dimensional gas flow developed in the vicinity of a sharp edge and driven by an external stream. Closed-form analysis is made in the free-molecular limit, where the impact of corner sidewall conditions is determined based on the Maxwell boundary model. The results obtained are compared with counterpart DSMC calculations, to test their validity and examine the effect of few molecular collisions (at large yet finite Knudsen numbers) on the vortical flow field. The impact of using other more elaborate gas–surface interaction models, namely the Cercignani–Lampis–Lord (CLL) law, is also discussed.

In the next section, the problem is formulated, for both circular (azimuthal) and straight outer flows. In § 3, the free-molecular solution is derived, and in § 4 the application of the DSMC numerical scheme is described. Our results are presented in § 5, and the work conclusions are discussed in § 6. Technical details are relegated to the appendices.

2. Statement of the problem

A schematic of the problem is presented in figure 1. Consider a perfect monatomic gas passing in the vicinity of a two-dimensional corner confined between solid walls of length

![]() $R^*$

(hereafter, asterisks denote dimensional quantities) with angle opening

$R^*$

(hereafter, asterisks denote dimensional quantities) with angle opening

![]() $0\lt 2\alpha \lt \pi$

. The outer flow is set at uniform density

$0\lt 2\alpha \lt \pi$

. The outer flow is set at uniform density

![]() $\rho _{\textit{out}}^*$

and temperature

$\rho _{\textit{out}}^*$

and temperature

![]() $T_{\textit{out}}^*$

. Using the marked Cartesian

$T_{\textit{out}}^*$

. Using the marked Cartesian

![]() $(x^*,y^*)$

or polar

$(x^*,y^*)$

or polar

![]() $(r^*,\theta )$

coordinate systems, two set-ups are examined, where the outer-flow velocity

$(r^*,\theta )$

coordinate systems, two set-ups are examined, where the outer-flow velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{V}_{\textit{out}}^*$

is directed in either the azimuthal

$\boldsymbol{V}_{\textit{out}}^*$

is directed in either the azimuthal

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat {\theta }}$

(figure 1

a) or vertical

$\boldsymbol{\hat {\theta }}$

(figure 1

a) or vertical

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat {y}}$

(figure 1

b) direction. These represent the open-cavity counterparts of circular- and straight-wall lid-driven flows, respectively, that may be generated by the corresponding motion of a far-field wall, not modelled in the present work. Placing the axis origin at the corner edge, we seek to describe the steady gas motion inside the corner in the highly rarefied flow regime, where the corner length

$\boldsymbol{\hat {y}}$

(figure 1

b) direction. These represent the open-cavity counterparts of circular- and straight-wall lid-driven flows, respectively, that may be generated by the corresponding motion of a far-field wall, not modelled in the present work. Placing the axis origin at the corner edge, we seek to describe the steady gas motion inside the corner in the highly rarefied flow regime, where the corner length

![]() $R^*$

is assumed small compared with the gas mean free path.

$R^*$

is assumed small compared with the gas mean free path.

Figure 1. Schematic of the problem. A two-dimensional corner of length

![]() $R^*$

and angle opening

$R^*$

and angle opening

![]() $2\alpha$

is affected by an external uniform flow in the azimuthal

$2\alpha$

is affected by an external uniform flow in the azimuthal

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat {\theta }}$

(a) or vertical

$\boldsymbol{\hat {\theta }}$

(a) or vertical

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat {y}}$

(b) direction, set at density

$\boldsymbol{\hat {y}}$

(b) direction, set at density

![]() $\rho _{\textit{out}}^*$

, temperature

$\rho _{\textit{out}}^*$

, temperature

![]() $T_{\textit{out}}^*$

and speed

$T_{\textit{out}}^*$

and speed

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}^*$

.

$V_{\textit{out}}^*$

.

In the framework of gas kinetic theory and the present two-dimensional steady-flow set-up, the gas state is determined through its probability density function

![]() $f^*=f^*(r^*,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*)$

, of finding a particle at position

$f^*=f^*(r^*,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*)$

, of finding a particle at position

![]() $(r^*,\theta )$

with molecular velocity of about

$(r^*,\theta )$

with molecular velocity of about

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }^*$

. To analyse the velocity space, a cylindrical coordinate description is applied, putting

$\boldsymbol{\xi }^*$

. To analyse the velocity space, a cylindrical coordinate description is applied, putting

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }^*=(\xi ^*_r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z^*)$

. Here,

$\boldsymbol{\xi }^*=(\xi ^*_r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z^*)$

. Here,

![]() $\xi ^*_r\in [0,\infty )$

is the molecular velocity magnitude in the corner plane of motion,

$\xi ^*_r\in [0,\infty )$

is the molecular velocity magnitude in the corner plane of motion,

![]() $\theta _\xi$

is the corresponding in-plane velocity direction with respect to the positive

$\theta _\xi$

is the corresponding in-plane velocity direction with respect to the positive

![]() $x^*$

axis and

$x^*$

axis and

![]() $\xi _z^*\in (-\infty ,\infty )$

is the velocity component normal to the corner plane.

$\xi _z^*\in (-\infty ,\infty )$

is the velocity component normal to the corner plane.

Outside the corner (where

![]() $r^*\gt R^*$

), the flow is set at

$r^*\gt R^*$

), the flow is set at

![]() $f_{\textit{out}}^*=f_{\textit{out}}^*(r^*,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*)$

, approaching a uniform Maxwellian at the indicated velocity

$f_{\textit{out}}^*=f_{\textit{out}}^*(r^*,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*)$

, approaching a uniform Maxwellian at the indicated velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{V}_{\textit{out}}^*$

, density

$\boldsymbol{V}_{\textit{out}}^*$

, density

![]() $\rho _{\textit{out}}^*$

and temperature

$\rho _{\textit{out}}^*$

and temperature

![]() $T_{\textit{out}}^*$

with increasing

$T_{\textit{out}}^*$

with increasing

![]() $r^*$

. At free-molecular conditions, gas particles entering the corner are strictly unaffected by outgoing particles, and therefore retain their far equilibrium Maxwellian. This condition becomes less effective with decreasing rarefaction rates. Yet, focusing on highly rarefied conditions, the impact of intermolecular interactions between outgoing and incoming particles is arguably minor, causing only a slight deviation from the above Maxwellian. We therefore apply the above-mentioned condition in subsequent DSMC calculations at high yet finite rarefaction rates. A more detailed study of the applicability of this approximation requires the simulation of the gas reservoir flow outside the corner. Such a study is skipped here, however, as similar investigations of counterpart gas systems at highly rarefied conditions (e.g. Ben-Adva & Manela Reference Ben-Adva and Manela2024) indicate that this effect is negligible at high rarefaction rates.

$r^*$

. At free-molecular conditions, gas particles entering the corner are strictly unaffected by outgoing particles, and therefore retain their far equilibrium Maxwellian. This condition becomes less effective with decreasing rarefaction rates. Yet, focusing on highly rarefied conditions, the impact of intermolecular interactions between outgoing and incoming particles is arguably minor, causing only a slight deviation from the above Maxwellian. We therefore apply the above-mentioned condition in subsequent DSMC calculations at high yet finite rarefaction rates. A more detailed study of the applicability of this approximation requires the simulation of the gas reservoir flow outside the corner. Such a study is skipped here, however, as similar investigations of counterpart gas systems at highly rarefied conditions (e.g. Ben-Adva & Manela Reference Ben-Adva and Manela2024) indicate that this effect is negligible at high rarefaction rates.

The specific form of

![]() $f_{\textit{out}}^*$

differs between the set-ups described in figure 1. For the circular-flow system shown in figure 1(a) we put

$f_{\textit{out}}^*$

differs between the set-ups described in figure 1. For the circular-flow system shown in figure 1(a) we put

\begin{align} \nonumber &f_{\textit{circ}}^* \! \left (R^*,-\alpha \lt \theta \lt \alpha ,\xi ^*_r,\theta +\pi /2\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta +3\pi /2,\xi _z^*\right ) \\ & \quad =\frac {\rho ^*_{\textit{out}}}{\pi ^{3/2}U^{*3}_{\textit{mp}}} \exp\! \left [-\frac {{{\xi ^*_r}^2+{V_{\textit{out}}^{*2}}}-2\xi _r^*V_{\textit{out}}^*\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )+{\xi _z^*}^2}}{U^{*2}_{\textit{mp}}}\right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \nonumber &f_{\textit{circ}}^* \! \left (R^*,-\alpha \lt \theta \lt \alpha ,\xi ^*_r,\theta +\pi /2\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta +3\pi /2,\xi _z^*\right ) \\ & \quad =\frac {\rho ^*_{\textit{out}}}{\pi ^{3/2}U^{*3}_{\textit{mp}}} \exp\! \left [-\frac {{{\xi ^*_r}^2+{V_{\textit{out}}^{*2}}}-2\xi _r^*V_{\textit{out}}^*\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )+{\xi _z^*}^2}}{U^{*2}_{\textit{mp}}}\right ]\!, \end{align}

whereas for the straight-outer-flow case in figure 1(b) we set

\begin{align} \nonumber &f^*_{\textit{straight}}\! \left (R^*\cos \alpha/ \cos \theta,-\alpha \lt \theta \lt \alpha ,\xi _r^*,\pi /2\lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi /2,\xi _z^* \right ) \\ & \quad =\frac {\rho ^*_{\textit{out}}}{\pi ^{3/2}U^{*3}_{\textit{mp}}}\exp\! \left [-\frac {{{\xi _r^*}^2+{V^{*2}_{\textit{out}}}}-2\xi _r^*V^*_{\textit{out}}\sin {\theta _\xi +{\xi _z^*}^2}}{U^{*2}_{\textit{mp}}}\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \nonumber &f^*_{\textit{straight}}\! \left (R^*\cos \alpha/ \cos \theta,-\alpha \lt \theta \lt \alpha ,\xi _r^*,\pi /2\lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi /2,\xi _z^* \right ) \\ & \quad =\frac {\rho ^*_{\textit{out}}}{\pi ^{3/2}U^{*3}_{\textit{mp}}}\exp\! \left [-\frac {{{\xi _r^*}^2+{V^{*2}_{\textit{out}}}}-2\xi _r^*V^*_{\textit{out}}\sin {\theta _\xi +{\xi _z^*}^2}}{U^{*2}_{\textit{mp}}}\right ]\!. \end{align}

In (2.1) and (2.2),

![]() $U^*_{\textit{mp}}=(2\mathcal{R}_g^*T^*_{\textit{out}})^{1/2}$

denotes the most probable speed of a gas particle at the outer-flow temperature, where

$U^*_{\textit{mp}}=(2\mathcal{R}_g^*T^*_{\textit{out}})^{1/2}$

denotes the most probable speed of a gas particle at the outer-flow temperature, where

![]() $\mathcal{R}^*_g$

is the specific gas constant.

$\mathcal{R}^*_g$

is the specific gas constant.

To model gas–surface interactions of the gas particles with the corner solid walls, we apply the prevailing Maxwell condition (Sone Reference Sone2007):

\begin{align} &\nonumber f^*\! \left (0\lt r^*\le R^*,\theta =\pm \alpha ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}\gt 0\right ) \\ & \quad =\beta \frac {\rho ^*_\pm (r^*)}{\pi ^{3/2}U^{*3}_{\textit{mp}_\pm }}\exp\! {\left [-\frac {{\xi ^*}^2}{U^{*2}_{\textit{mp}_\pm }}\right ]} + (1-\beta ) f^*(r^*,\pm \alpha ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*-2(\boldsymbol{\xi }^*\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\hat {n}})\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}), \end{align}

\begin{align} &\nonumber f^*\! \left (0\lt r^*\le R^*,\theta =\pm \alpha ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}\gt 0\right ) \\ & \quad =\beta \frac {\rho ^*_\pm (r^*)}{\pi ^{3/2}U^{*3}_{\textit{mp}_\pm }}\exp\! {\left [-\frac {{\xi ^*}^2}{U^{*2}_{\textit{mp}_\pm }}\right ]} + (1-\beta ) f^*(r^*,\pm \alpha ,\boldsymbol{\xi }^*-2(\boldsymbol{\xi }^*\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\hat {n}})\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}), \end{align}

where the relative

![]() $\beta$

and

$\beta$

and

![]() $(1-\beta )$

parts of the gas molecules are emitted diffusely and specularly, respectively, at each point along the boundaries. Here,

$(1-\beta )$

parts of the gas molecules are emitted diffusely and specularly, respectively, at each point along the boundaries. Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}$

is a unit vector directed normal to each wall and into the corner domain and

$\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}$

is a unit vector directed normal to each wall and into the corner domain and

![]() $\rho ^*_\pm (r^*)$

are as yet unknown functions associated with the mass flux of particles reflected from the surfaces

$\rho ^*_\pm (r^*)$

are as yet unknown functions associated with the mass flux of particles reflected from the surfaces

![]() $\theta =\pm \alpha$

, respectively. Additionally,

$\theta =\pm \alpha$

, respectively. Additionally,

![]() $U^*_{{mp}_\pm }=(2\mathcal{R}_g^*T^*_\pm )^{1/2}$

denotes the most probable speed of gas particles at the corner wall temperatures

$U^*_{{mp}_\pm }=(2\mathcal{R}_g^*T^*_\pm )^{1/2}$

denotes the most probable speed of gas particles at the corner wall temperatures

![]() $T^*_\pm$

. We hereafter assume that the corner surfaces are isothermal and maintained at the reference outer-flow temperature; thus

$T^*_\pm$

. We hereafter assume that the corner surfaces are isothermal and maintained at the reference outer-flow temperature; thus

![]() $T^*_\pm =T^*_{\textit{out}}$

and

$T^*_\pm =T^*_{\textit{out}}$

and

![]() $U^*_{{mp}_\pm }=U^*_{\textit{mp}}$

.

$U^*_{{mp}_\pm }=U^*_{\textit{mp}}$

.

Describing the

![]() $\beta =1$

and

$\beta =1$

and

![]() $\beta =0$

limit cases in (2.3), the former diffuse scattering occurs over rough surfaces, where the colliding particles attain thermal equilibrium with their reflecting boundaries. Specular (

$\beta =0$

limit cases in (2.3), the former diffuse scattering occurs over rough surfaces, where the colliding particles attain thermal equilibrium with their reflecting boundaries. Specular (

![]() $\beta =0$

) interactions take place where the incident molecules collide with a solid surface and rebound elastically as if hitting a perfectly smooth wall. While none of these idealised scenarios exists in reality, it is commonly accepted that wall reflections from realistic surfaces may be described as a combination of diffuse and specular interactions, as formulated in (2.3). In particular, the practical realisation of nearly smooth walls, analysed in detail below, has been highlighted in a series of experimental investigations, showing close agreement between laboratory measurements and Maxwell-based theoretical predictions with

$\beta =0$

) interactions take place where the incident molecules collide with a solid surface and rebound elastically as if hitting a perfectly smooth wall. While none of these idealised scenarios exists in reality, it is commonly accepted that wall reflections from realistic surfaces may be described as a combination of diffuse and specular interactions, as formulated in (2.3). In particular, the practical realisation of nearly smooth walls, analysed in detail below, has been highlighted in a series of experimental investigations, showing close agreement between laboratory measurements and Maxwell-based theoretical predictions with

![]() $\beta \ll 1$

(Honig & Ducker Reference Honig and Ducker2010; Bowles & Ducker Reference Bowles and Ducker2011; Seo & Ducker Reference Seo and Ducker2013, Reference Seo and Ducker2014; Lei & McKenzie Reference Lei and McKenzie2015; Yousefi-Nasab, Safdari & Karimi-Sabet Reference Yousefi-Nasab, Safdari and Karimi-Sabet2024). Noting the dominant effect of gas-surface interaction on the flow field obtained at highly rarefied conditions, we additionally examine the application of the more elaborate CLL kernel (Cercignani & Lampis Reference Cercignani and Lampis1971; Lord Reference Lord1991) on the results in § 5.4.2. Yet, our discussion focuses primarily on the Maxwell condition, due to its common use and relative simplicity, which allows for the closed-form analysis carried out below.

$\beta \ll 1$

(Honig & Ducker Reference Honig and Ducker2010; Bowles & Ducker Reference Bowles and Ducker2011; Seo & Ducker Reference Seo and Ducker2013, Reference Seo and Ducker2014; Lei & McKenzie Reference Lei and McKenzie2015; Yousefi-Nasab, Safdari & Karimi-Sabet Reference Yousefi-Nasab, Safdari and Karimi-Sabet2024). Noting the dominant effect of gas-surface interaction on the flow field obtained at highly rarefied conditions, we additionally examine the application of the more elaborate CLL kernel (Cercignani & Lampis Reference Cercignani and Lampis1971; Lord Reference Lord1991) on the results in § 5.4.2. Yet, our discussion focuses primarily on the Maxwell condition, due to its common use and relative simplicity, which allows for the closed-form analysis carried out below.

To render the problem dimensionless, we scale the position by the corner wall length

![]() $R^*$

, the velocity by the outer-temperature-based most probable molecular speed

$R^*$

, the velocity by the outer-temperature-based most probable molecular speed

![]() $U^*_{\textit{mp}}$

and the density and temperature by

$U^*_{\textit{mp}}$

and the density and temperature by

![]() $\rho ^*_{\textit{out}}$

and

$\rho ^*_{\textit{out}}$

and

![]() $T^*_{\textit{out}}$

, respectively. The system non-dimensional description is subsequently governed by the outer-flow reduced velocity

$T^*_{\textit{out}}$

, respectively. The system non-dimensional description is subsequently governed by the outer-flow reduced velocity

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

, the corner semi-angle

$V_{\textit{out}}$

, the corner semi-angle

![]() $\alpha$

and the wall accommodation coefficient

$\alpha$

and the wall accommodation coefficient

![]() $\beta$

. In addition, the gas mean Knudsen number is introduced:

$\beta$

. In addition, the gas mean Knudsen number is introduced:

where

![]() $\lambda ^*$

is the mean free path of a gas molecule at the outer-flow conditions. Assuming a hard-sphere gas model,

$\lambda ^*$

is the mean free path of a gas molecule at the outer-flow conditions. Assuming a hard-sphere gas model,

![]() $\lambda ^*=m^*/(\pi \sqrt {2}\rho _{\textit{out}}^*d^{*2})$

, where

$\lambda ^*=m^*/(\pi \sqrt {2}\rho _{\textit{out}}^*d^{*2})$

, where

![]() $m^*$

and

$m^*$

and

![]() $d^*$

denote the gas molecular mass and diameter, respectively (Sone Reference Sone2007).

$d^*$

denote the gas molecular mass and diameter, respectively (Sone Reference Sone2007).

In what follows, we first analyse the free-molecular problem, where

![]() $\textit{Kn}\rightarrow \infty$

. Considering steady flow conditions, the cases of specular and diffuse wall reflections are studied separately, yielding explicit solutions for the collisionless flow regime in the set-ups described in figures 1(a) and 1(b). The application of the DSMC scheme, used to analyse the problem at large yet finite Knudsen numbers, is described in a subsequent section.

$\textit{Kn}\rightarrow \infty$

. Considering steady flow conditions, the cases of specular and diffuse wall reflections are studied separately, yielding explicit solutions for the collisionless flow regime in the set-ups described in figures 1(a) and 1(b). The application of the DSMC scheme, used to analyse the problem at large yet finite Knudsen numbers, is described in a subsequent section.

3. The free-molecular limit

Assuming

![]() $\textit{Kn}\rightarrow \infty$

and steady flow conditions, the gas kinetic problem is governed by the collisionless two-dimensional time-independent Boltzmann equation:

$\textit{Kn}\rightarrow \infty$

and steady flow conditions, the gas kinetic problem is governed by the collisionless two-dimensional time-independent Boltzmann equation:

stating that

![]() $f=f(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

remains unchanged along ‘free-flight’ particle trajectories in the absence of molecular collisions. Variations in the probability density function may therefore occur solely due to particle–surface interactions, governed by the scaled form of (2.3):

$f=f(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

remains unchanged along ‘free-flight’ particle trajectories in the absence of molecular collisions. Variations in the probability density function may therefore occur solely due to particle–surface interactions, governed by the scaled form of (2.3):

The solid-wall condition in (3.2) is supplemented by the non-dimensional counterpart of (2.1) or (2.2), prescribing the outer-flow state. In what follows, the free-molecular problem is analysed separately for the cases of fully specular (

![]() $\beta =0$

, § 3.1) and fully diffuse (

$\beta =0$

, § 3.1) and fully diffuse (

![]() $\beta =1$

, § 3.2) configurations. Discussion of the combined specular-diffuse (

$\beta =1$

, § 3.2) configurations. Discussion of the combined specular-diffuse (

![]() $\beta \neq 0,1$

) set-up, obtained through superposition of the above two limits, is deferred to § 5.4.1.

$\beta \neq 0,1$

) set-up, obtained through superposition of the above two limits, is deferred to § 5.4.1.

Once the probability density function has been obtained, the hydrodynamic fields are calculated via appropriate quadratures over the molecular velocity space (Sone Reference Sone2007). Specifically, the density

![]() $\rho (r,\theta )$

, radial and azimuthal velocity components

$\rho (r,\theta )$

, radial and azimuthal velocity components

![]() $u_r(r,\theta )$

and

$u_r(r,\theta )$

and

![]() $u_\theta (r,\theta )$

, respectively, and pressure

$u_\theta (r,\theta )$

, respectively, and pressure

![]() $p(r,\theta )$

fields are given by

$p(r,\theta )$

fields are given by

\begin{align} \nonumber &\rho = \int _{-\infty }^{\infty } f{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \ \ ,\ \ u_r = \frac {1}{\rho }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\xi _r \cos {(\theta _\xi -\theta )} f {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \ \ , \ \ u_\theta = \frac {1}{\rho }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )} f {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \\ & \quad {\rm and} \quad p =\frac {2}{3} \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\left (\left (u_r-\xi _r \cos {(\theta _\xi -\theta )}\right )^2+\left (u_\theta -\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )}\right )^2+\xi _z^2\right )f{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } , \end{align}

\begin{align} \nonumber &\rho = \int _{-\infty }^{\infty } f{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \ \ ,\ \ u_r = \frac {1}{\rho }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\xi _r \cos {(\theta _\xi -\theta )} f {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \ \ , \ \ u_\theta = \frac {1}{\rho }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )} f {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \\ & \quad {\rm and} \quad p =\frac {2}{3} \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\left (\left (u_r-\xi _r \cos {(\theta _\xi -\theta )}\right )^2+\left (u_\theta -\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )}\right )^2+\xi _z^2\right )f{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } , \end{align}

where

![]() ${\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }=\xi _r{\rm d}\xi _r{\rm d}\theta _\xi {\rm d}\xi _z$

. The temperature is computed via the scaled form of the equation of state for an ideal gas,

${\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }=\xi _r{\rm d}\xi _r{\rm d}\theta _\xi {\rm d}\xi _z$

. The temperature is computed via the scaled form of the equation of state for an ideal gas,

![]() $T(r,\theta )=p/\rho$

.

$T(r,\theta )=p/\rho$

.

3.1. Specular reflecting corner (

$\beta =0$

)

$\beta =0$

)

Considering a specular-wall corner set-up (see (3.2) with

![]() $\beta =0$

), the impermeability condition is satisfied identically. Thus, given a particle in-corner phase-space location

$\beta =0$

), the impermeability condition is satisfied identically. Thus, given a particle in-corner phase-space location

![]() $(r,\theta ,\xi _r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z)$

, the specular-wall problem reduces to tracking its initial state at entering the corner, denoted by

$(r,\theta ,\xi _r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z)$

, the specular-wall problem reduces to tracking its initial state at entering the corner, denoted by

![]() $(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\bar {\xi }_r,\bar {\theta }_\xi ,\xi _z)$

(note that, while

$(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\bar {\xi }_r,\bar {\theta }_\xi ,\xi _z)$

(note that, while

![]() $\bar {r}=1$

in the circular-outer-flow case,

$\bar {r}=1$

in the circular-outer-flow case,

![]() $\bar {r}=\cos \alpha /\cos \bar \theta$

in the straight-outer-flow problem; see figure 1). Clearly, since the magnitude of particle velocity does not change due to specular-wall interactions,

$\bar {r}=\cos \alpha /\cos \bar \theta$

in the straight-outer-flow problem; see figure 1). Clearly, since the magnitude of particle velocity does not change due to specular-wall interactions,

![]() $\bar {\xi }_r=\xi _r$

. Then, observing the change in particle trajectory direction with each specular-wall collision, we find

$\bar {\xi }_r=\xi _r$

. Then, observing the change in particle trajectory direction with each specular-wall collision, we find

\begin{equation} \bar {\theta }_\xi = \begin{cases}(-1)^k(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k) , \quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ (-1)^k(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k) , \quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \bar {\theta }_\xi = \begin{cases}(-1)^k(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k) , \quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ (-1)^k(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k) , \quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{cases} \end{equation}

where

![]() $k$

marks the total number of wall collisions since the particle has entered the corner. The maximum number of wall collisions encountered by a particle at a given

$k$

marks the total number of wall collisions since the particle has entered the corner. The maximum number of wall collisions encountered by a particle at a given

![]() $\theta$

location is independent of

$\theta$

location is independent of

![]() $r$

, and given by

$r$

, and given by

\begin{align} \begin{split} &n_{\textit{max}}^+(\theta ) = \left \lceil \frac {\pi +\theta -\alpha }{2\alpha }\right \rceil\! , \quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ &n_{\textit{max}}^-(\theta ) = \left \lceil \frac {\pi -\theta -\alpha }{2\alpha }\right \rceil\! , \quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{split} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{split} &n_{\textit{max}}^+(\theta ) = \left \lceil \frac {\pi +\theta -\alpha }{2\alpha }\right \rceil\! , \quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ &n_{\textit{max}}^-(\theta ) = \left \lceil \frac {\pi -\theta -\alpha }{2\alpha }\right \rceil\! , \quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{split} \end{align}

where ‘

![]() $+$

’ and ‘

$+$

’ and ‘

![]() $-$

’ specify whether the last collision occurred with the

$-$

’ specify whether the last collision occurred with the

![]() $\theta =\alpha$

or

$\theta =\alpha$

or

![]() $\theta =-\alpha$

surfaces, respectively, and

$\theta =-\alpha$

surfaces, respectively, and

![]() $\lceil \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rceil$

is the integer ceiling of a number.

$\lceil \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rceil$

is the integer ceiling of a number.

Inspecting (3.5), it is observed that the maximum values of

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}^\pm (\theta )$

are achieved at the

$n_{\textit{max}}^\pm (\theta )$

are achieved at the

![]() $\theta =\pm \alpha$

solid walls, respectively, and are equal to

$\theta =\pm \alpha$

solid walls, respectively, and are equal to

In fact, the trajectories separating particle pathlines with different number of surface reflections are those passing through the wall-edge points,

![]() $(r,\theta )=(1,\pm \alpha )$

. The corresponding separating

$(r,\theta )=(1,\pm \alpha )$

. The corresponding separating

![]() $\theta _\xi$

directions are

$\theta _\xi$

directions are

\begin{align} \begin{split} &\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k}(r,\theta ) = a^+\pi + \theta +\arctan {\left (\frac {\sin \left (\alpha (2k+1)-\theta \right )}{\cos \left (\alpha (2k+1)-\theta \right )-r}\right )} , \quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ &\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k}(r,\theta ) = a^-\pi +\theta +\arctan {\left (\frac {\sin \left (\alpha (2k+1)+\theta \right )}{r-\cos \left (\alpha (2k+1)+\theta \right )}\right )} , \quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi . \end{split} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{split} &\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k}(r,\theta ) = a^+\pi + \theta +\arctan {\left (\frac {\sin \left (\alpha (2k+1)-\theta \right )}{\cos \left (\alpha (2k+1)-\theta \right )-r}\right )} , \quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ &\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k}(r,\theta ) = a^-\pi +\theta +\arctan {\left (\frac {\sin \left (\alpha (2k+1)+\theta \right )}{r-\cos \left (\alpha (2k+1)+\theta \right )}\right )} , \quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi . \end{split} \end{align}

In (3.7), each

![]() $k=0,1,\ldots , n_{\textit{max}}^{{+/-}}(\theta )-1$

value (see (3.5)) fixes the limit

$k=0,1,\ldots , n_{\textit{max}}^{{+/-}}(\theta )-1$

value (see (3.5)) fixes the limit

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+/-,k}$

trajectory direction that separates particle pathlines with

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+/-,k}$

trajectory direction that separates particle pathlines with

![]() $k$

and

$k$

and

![]() $k+1$

wall collisions. Here, the integer constants

$k+1$

wall collisions. Here, the integer constants

![]() $a^+$

and

$a^+$

and

![]() $a^-$

are the

$a^-$

are the

![]() $\pi$

-multiples allotted such that

$\pi$

-multiples allotted such that

![]() $\theta _\xi$

is contained within the permitted

$\theta _\xi$

is contained within the permitted

![]() $(\pi ,2\pi +\theta )$

and

$(\pi ,2\pi +\theta )$

and

![]() $(2\pi +\theta ,3\pi )$

intervals, respectively.

$(2\pi +\theta ,3\pi )$

intervals, respectively.

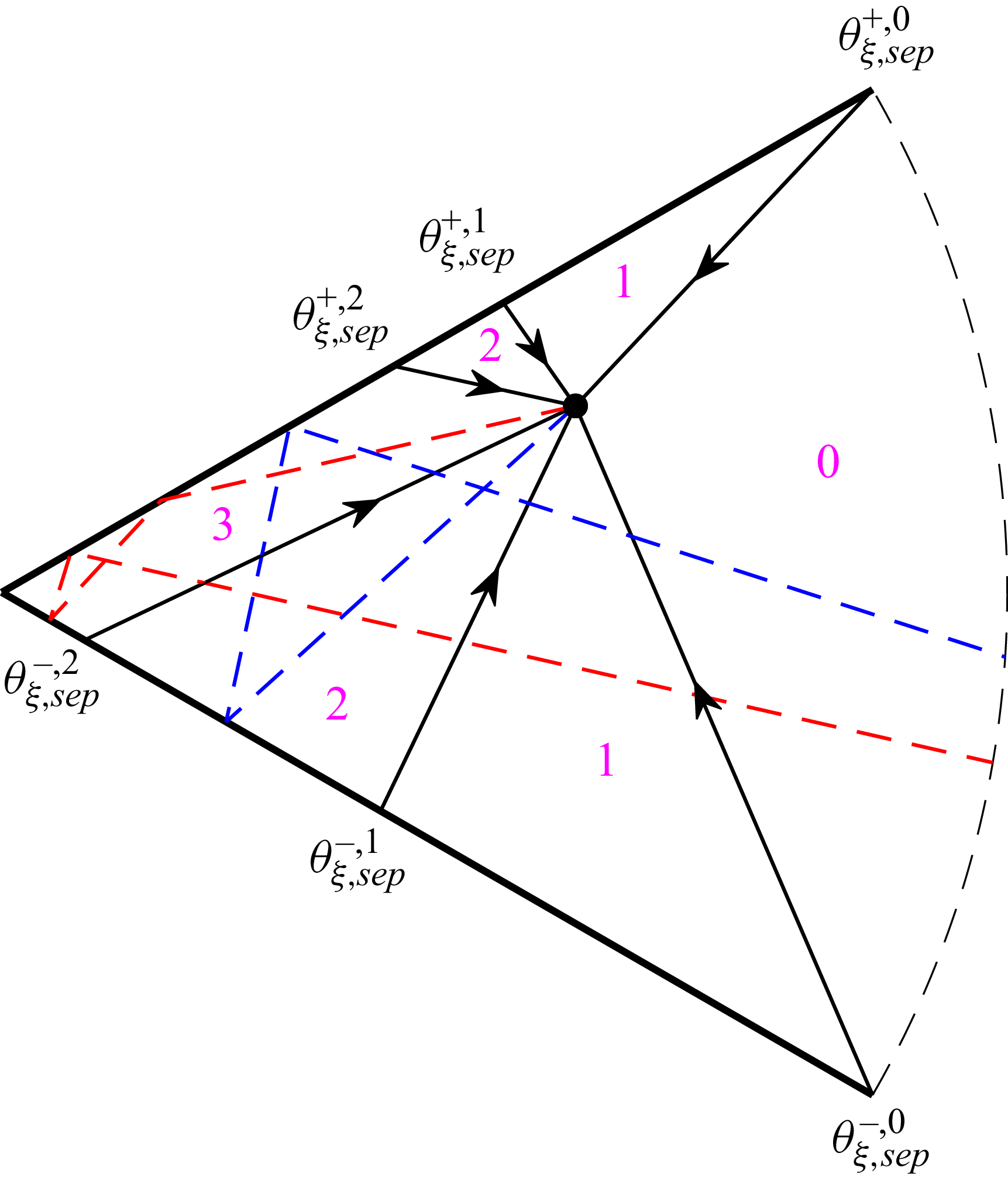

To illustrate the interpretation of (3.7), figure 2 shows, for a

![]() $2\alpha =\pi /3$

specular corner set-up at

$2\alpha =\pi /3$

specular corner set-up at

![]() $(r,\theta )=(0.6,\pi /10)$

, an example for the

$(r,\theta )=(0.6,\pi /10)$

, an example for the

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k}(r,\theta )$

division. Specifically, the

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k}(r,\theta )$

division. Specifically, the

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0-2}\approx 1.26\pi ,1.69\pi ,1.93\pi$

and

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0-2}\approx 1.26\pi ,1.69\pi ,1.93\pi$

and

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0-2}\approx 2.63\pi ,2.36\pi ,2.14\pi$

directions are depicted, respectively, by the arrowed lines (see (3.7)), together with indication of particle trajectories undergoing two (dashed blue curve) and three (dashed red curve) wall collisions. Here, particles arriving at

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0-2}\approx 2.63\pi ,2.36\pi ,2.14\pi$

directions are depicted, respectively, by the arrowed lines (see (3.7)), together with indication of particle trajectories undergoing two (dashed blue curve) and three (dashed red curve) wall collisions. Here, particles arriving at

![]() $(0.6,\pi /10)$

with in-plane velocity direction in the range

$(0.6,\pi /10)$

with in-plane velocity direction in the range

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2} \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,1}$

have collided twice with the corner walls (where the recent collision occurred with the

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2} \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,1}$

have collided twice with the corner walls (where the recent collision occurred with the

![]() $\theta =-\alpha$

surface), whereas particles with

$\theta =-\alpha$

surface), whereas particles with

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,2}$

have been reflected three times. At the chosen

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,2}$

have been reflected three times. At the chosen

![]() $\theta =\pi /10$

azimuthal direction,

$\theta =\pi /10$

azimuthal direction,

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}^\pm (\theta )=3$

, in accordance with (3.5).

$n_{\textit{max}}^\pm (\theta )=3$

, in accordance with (3.5).

Figure 2. Particle kinematics in a specular-wall corner: the arrow-marked lines show the

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{\pm ,k}$

(with

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{\pm ,k}$

(with

![]() $k=0,1,2$

) directions (see (3.7)) calculated at

$k=0,1,2$

) directions (see (3.7)) calculated at

![]() $(r,\theta )=(0.6,\pi /10)$

in a

$(r,\theta )=(0.6,\pi /10)$

in a

![]() $2\alpha =\pi /3$

corner. The

$2\alpha =\pi /3$

corner. The

![]() $\theta =\pm \pi /6$

corner walls are marked by the bold lines and the point is indicated by the circle. The numbers in magenta are the numbers of wall collisions encountered by particles arriving at

$\theta =\pm \pi /6$

corner walls are marked by the bold lines and the point is indicated by the circle. The numbers in magenta are the numbers of wall collisions encountered by particles arriving at

![]() $(r,\theta )=(0.6,\pi /10)$

through the respective sections confined by the arrow-marked lines. The dashed red and blue curves show example trajectories with

$(r,\theta )=(0.6,\pi /10)$

through the respective sections confined by the arrow-marked lines. The dashed red and blue curves show example trajectories with

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,2}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2}$

(containing three wall collisions) and

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,2}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2}$

(containing three wall collisions) and

![]() $\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,1}$

(having two surface reflections), respectively.

$\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,2}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,1}$

(having two surface reflections), respectively.

Once the sorting of particle trajectories at a given

![]() $(r,\theta )$

location is completed, the specular-wall

$(r,\theta )$

location is completed, the specular-wall

![]() $f^{\textit{(spec)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

is obtained as

$f^{\textit{(spec)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

is obtained as

\begin{align} f^{{(\textit{spec})}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }) = \begin{cases} f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z) \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ,\pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k-1}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k} \ \ \ \ \ \ ,k=1,\ldots ,n_{\textit{max}}^{+}(\theta )-1 \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k-1}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \ \ \ \ ,k=n_{\textit{max}}^+(\theta ) \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k-1} \ \ \ \ ,k=n_{\textit{max}}^-(\theta ) \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k-1} \ \ \ \ \ \ ,k=n_{\textit{max}}^{-}(\theta )-1, \ldots ,1 \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z) \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \\ \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} f^{{(\textit{spec})}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }) = \begin{cases} f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z) \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ,\pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k-1}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k} \ \ \ \ \ \ ,k=1,\ldots ,n_{\textit{max}}^{+}(\theta )-1 \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,k-1}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \ \ \ \ ,k=n_{\textit{max}}^+(\theta ) \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k-1} \ \ \ \ ,k=n_{\textit{max}}^-(\theta ) \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,(-1)^k(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k),\xi _z) \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k}\lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,k-1} \ \ \ \ \ \ ,k=n_{\textit{max}}^{-}(\theta )-1, \ldots ,1 \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\xi _r,\theta _\xi ,\xi _z) \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ,\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \\ \end{cases} \end{align}

where

![]() $f_{\textit{out}}$

differs between circular- and straight-outer-flow set-ups (or any other outer flow of interest), as specified by the non-dimensional counterparts of (2.1) and (2.2), respectively. The values of

$f_{\textit{out}}$

differs between circular- and straight-outer-flow set-ups (or any other outer flow of interest), as specified by the non-dimensional counterparts of (2.1) and (2.2), respectively. The values of

![]() $\bar {r}$

and

$\bar {r}$

and

![]() $\bar \theta$

similarly vary between the two configurations, as detailed in §§ 3.1.1 and 3.1.2.

$\bar \theta$

similarly vary between the two configurations, as detailed in §§ 3.1.1 and 3.1.2.

Once

![]() $f^{\textit{(spec)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

is known, the calculation of the hydrodynamic fields follows (3.3). All

$f^{\textit{(spec)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

is known, the calculation of the hydrodynamic fields follows (3.3). All

![]() $\xi _z$

and

$\xi _z$

and

![]() $\xi _r$

quadratures may be carried out in a closed form, yielding expressions containing the Gamma function. The integrations over

$\xi _r$

quadratures may be carried out in a closed form, yielding expressions containing the Gamma function. The integrations over

![]() $\theta _\xi$

are then evaluated numerically, requiring a minor computational effort.

$\theta _\xi$

are then evaluated numerically, requiring a minor computational effort.

3.1.1. Circular outer flow

In the circular-flow configuration,

![]() $\bar {r}=1$

. Scaling (2.1), we obtain

$\bar {r}=1$

. Scaling (2.1), we obtain

where, in line with subsequent geometrical considerations,

\begin{equation} \bar {\theta }= \begin{cases} (-1)^k(\theta _\xi -\pi -2\alpha k+\arcsin {(r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )})}) ,\quad\pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ (-1)^k(\theta _\xi -\pi +2\alpha k+\arcsin {(r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )})}) ,\quad2 \pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi . \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \bar {\theta }= \begin{cases} (-1)^k(\theta _\xi -\pi -2\alpha k+\arcsin {(r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )})}) ,\quad\pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ (-1)^k(\theta _\xi -\pi +2\alpha k+\arcsin {(r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\theta )})}) ,\quad2 \pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi . \end{cases} \end{equation}

Substituting (3.9) and (3.10) together with

![]() $\bar {r}=1$

into (3.8), we find

$\bar {r}=1$

into (3.8), we find

where the value of

![]() $k$

, denoting the number of particle–wall collisions along its trajectory, is determined through (3.7).

$k$

, denoting the number of particle–wall collisions along its trajectory, is determined through (3.7).

3.1.2. Straight outer flow

In the straight-outer-flow set-up,

![]() $\bar {r}=\cos \alpha /\cos \bar {\theta }$

, and (cf. (2.2))

$\bar {r}=\cos \alpha /\cos \bar {\theta }$

, and (cf. (2.2))

Substituting (3.4) and (3.12) into (3.8) and carrying out some algebraic manipulations, we find

\begin{align} f_{\textit{straight}}^{\textit{(spec)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }) = \begin{cases} \pi ^{-3/2}\exp\! \left [-\xi _r^2-V_{\textit{out}}^2+(-1)^k2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}}\sin {(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k)}-\xi _z^2\right ]\! ,\quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \nonumber \\ \pi ^{-3/2}\exp\! \left [-\xi _r^2-V_{\textit{out}}^2+(-1)^k2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}}\sin {(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k)}-\xi _z^2\right ]\! ,\quad2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} f_{\textit{straight}}^{\textit{(spec)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi }) = \begin{cases} \pi ^{-3/2}\exp\! \left [-\xi _r^2-V_{\textit{out}}^2+(-1)^k2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}}\sin {(\theta _\xi -2\alpha k)}-\xi _z^2\right ]\! ,\quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \nonumber \\ \pi ^{-3/2}\exp\! \left [-\xi _r^2-V_{\textit{out}}^2+(-1)^k2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}}\sin {(\theta _\xi +2\alpha k)}-\xi _z^2\right ]\! ,\quad2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{cases} \end{align}

where

![]() $k$

, as above, is the number of wall collisions for each

$k$

, as above, is the number of wall collisions for each

![]() $\theta _\xi$

, determined using (3.7).

$\theta _\xi$

, determined using (3.7).

3.2. Diffuse reflecting corner (

$\beta =1$

)

$\beta =1$

)

Setting

![]() $\beta =1$

in (3.2), the probability density function associated with each gas particle is governed by its most recent interaction with one of the corner (solid or free) surfaces. Recalling that the prescribed outer-flow and corner-wall temperatures are equal (see (2.3) et seq.), the expression for the scaled diffuse-wall probability density function

$\beta =1$

in (3.2), the probability density function associated with each gas particle is governed by its most recent interaction with one of the corner (solid or free) surfaces. Recalling that the prescribed outer-flow and corner-wall temperatures are equal (see (2.3) et seq.), the expression for the scaled diffuse-wall probability density function

![]() $f^{\textit{(diff)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

is

$f^{\textit{(diff)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })$

is

\begin{equation} f^{\textit{(diff)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })= \begin{cases} \pi ^{-3/2}\rho _+(r_+)\exp\! \left [-\xi ^2 \right ]\! ,\quad \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ \pi ^{-3/2}\rho _-(r_-)\exp\! \left [-\xi ^2 \right ]\! ,\quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0} \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi }) ,\quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} \quad \text{or} \quad \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} f^{\textit{(diff)}}(r,\theta ,\boldsymbol{\xi })= \begin{cases} \pi ^{-3/2}\rho _+(r_+)\exp\! \left [-\xi ^2 \right ]\! ,\quad \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 2\pi +\theta \\ \pi ^{-3/2}\rho _-(r_-)\exp\! \left [-\xi ^2 \right ]\! ,\quad 2\pi +\theta \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0} \\ f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi }) ,\quad \pi \lt \theta _\xi \lt \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} \quad \text{or} \quad \theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}\lt \theta _\xi \lt 3\pi , \end{cases} \end{equation}

where

![]() $r_\pm$

denote the point of recent reflection of the particle from the

$r_\pm$

denote the point of recent reflection of the particle from the

![]() $\theta =\pm \alpha$

boundary, respectively. The wall flux

$\theta =\pm \alpha$

boundary, respectively. The wall flux

![]() $\rho _\pm (r_\pm )$

functions are fixed through the impermeability condition along each of the solid corner surfaces, taking the form

$\rho _\pm (r_\pm )$

functions are fixed through the impermeability condition along each of the solid corner surfaces, taking the form

Here, the first and second integrals express the separate contributions of the outgoing and incoming particles to the macroscopic gas velocity normal to the surface, respectively. We next calculate the explicit form of this condition on each of the corner walls.

Considering the impermeability balance over the

![]() $\theta =\alpha$

surface and starting with the contribution of reflected particles, we substitute (3.14) into the first integral in (3.15), to obtain

$\theta =\alpha$

surface and starting with the contribution of reflected particles, we substitute (3.14) into the first integral in (3.15), to obtain

Then, the contribution of the incoming particles to the flux balance, accounted for by the second integral in (3.15), is

\begin{align} \nonumber &{ \int _{\boldsymbol{\xi }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}\lt 0}\xi _r\sin (\theta _\xi -\alpha )f(r,\alpha,\boldsymbol{\xi })\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }}= \frac {1}{4\sqrt {\pi }} \int _{\alpha +2\pi }^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0} } \rho _-\left (\frac {r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}}{\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha )}}\right )\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}\,{\rm d}\theta _\xi \\ &\quad +\int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _\pi ^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \nonumber \\& \quad + \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}}^{3\pi } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }, \end{align}

\begin{align} \nonumber &{ \int _{\boldsymbol{\xi }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\hat {n}}\lt 0}\xi _r\sin (\theta _\xi -\alpha )f(r,\alpha,\boldsymbol{\xi })\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }}= \frac {1}{4\sqrt {\pi }} \int _{\alpha +2\pi }^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0} } \rho _-\left (\frac {r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}}{\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha )}}\right )\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}\,{\rm d}\theta _\xi \\ &\quad +\int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _\pi ^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \nonumber \\& \quad + \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}}^{3\pi } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }, \end{align}

where the

![]() $\xi _z$

and

$\xi _z$

and

![]() $\xi _r$

quadratures for the particles arriving from the

$\xi _r$

quadratures for the particles arriving from the

![]() $\theta =-\alpha$

wall were computed analytically. Combining (3.16) and (3.17), we obtain the no-penetration condition over the

$\theta =-\alpha$

wall were computed analytically. Combining (3.16) and (3.17), we obtain the no-penetration condition over the

![]() $\theta =\alpha$

surface:

$\theta =\alpha$

surface:

\begin{align} &\frac {\rho _+(r)}{2\sqrt {\pi }}- \frac {1}{4\sqrt {\pi }} \int _{\alpha +2\pi }^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0} } \rho _-\left (\frac {r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}}{\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha )}}\right )\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha })\,{\rm d}\theta _\xi \nonumber \\ & \quad =\int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _\pi ^{\pi +\alpha } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha })\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \nonumber \\ & \quad + \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}}^{3\pi } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha })\, {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }, \end{align}

\begin{align} &\frac {\rho _+(r)}{2\sqrt {\pi }}- \frac {1}{4\sqrt {\pi }} \int _{\alpha +2\pi }^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0} } \rho _-\left (\frac {r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}}{\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha )}}\right )\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha })\,{\rm d}\theta _\xi \nonumber \\ & \quad =\int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _\pi ^{\pi +\alpha } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha })\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \nonumber \\ & \quad + \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{-,0}}^{3\pi } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha })\, {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }, \end{align}

with the outer-flow contribution expressed as the forcing terms on the right-hand side. A similar calculation over the

![]() $\theta =-\alpha$

wall yields the no-flux balance:

$\theta =-\alpha$

wall yields the no-flux balance:

\begin{align} &\frac {\rho _-(r)}{2\sqrt {\pi }}+ \frac {1}{4\sqrt {\pi }}\int _{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0}}^{2\pi -\alpha } \rho _+\left (\frac {r\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha )}}{\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}}\right )\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha })\,{\rm d}\theta _\xi \nonumber \\& \quad = -\int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _\pi ^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha })\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \nonumber \\& \quad - \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _{3\pi -\alpha }^{3\pi } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha })\, {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }. \end{align}

\begin{align} &\frac {\rho _-(r)}{2\sqrt {\pi }}+ \frac {1}{4\sqrt {\pi }}\int _{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0}}^{2\pi -\alpha } \rho _+\left (\frac {r\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha )}}{\sin {(\theta _\xi -\alpha )}}\right )\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha })\,{\rm d}\theta _\xi \nonumber \\& \quad = -\int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _\pi ^{\theta _{\xi ,\textit{sep}}^{+,0} } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha })\,{\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi } \nonumber \\& \quad - \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _0^\infty \int _{3\pi -\alpha }^{3\pi } f_{\textit{out}}(\bar {r},\bar {\theta },\boldsymbol{\xi })\xi _r\sin {(\theta _\xi +\alpha })\, {\rm d}\boldsymbol{\xi }. \end{align}

Equations (3.18)–(3.19) form a system of coupled non-homogeneous integral balances for the wall-flux functions

![]() $\rho _+(r)$

and

$\rho _+(r)$

and

![]() $\rho _-(r)$

. Once

$\rho _-(r)$

. Once

![]() $f_{\textit{out}}$

is specified for either circular or straight outer flows (see (3.9) or (3.12), respectively), the problem is solved numerically by discretising the fluxes at equally spaced

$f_{\textit{out}}$

is specified for either circular or straight outer flows (see (3.9) or (3.12), respectively), the problem is solved numerically by discretising the fluxes at equally spaced

![]() $N_w$

points along the corner boundaries. The integral terms are evaluated using the trapezoidal rule with

$N_w$

points along the corner boundaries. The integral terms are evaluated using the trapezoidal rule with

![]() $N_{\theta _\xi }\approx 10^4$

points, yielding a system of

$N_{\theta _\xi }\approx 10^4$

points, yielding a system of

![]() $2N_w$

linear non-homogeneous algebraic equations, inverted using a MATLAB subroutine. Our calculations indicate that converged results (with an error

$2N_w$

linear non-homogeneous algebraic equations, inverted using a MATLAB subroutine. Our calculations indicate that converged results (with an error

![]() $\lesssim 0.1\,\%$

) are obtained for

$\lesssim 0.1\,\%$

) are obtained for

![]() $N_w\approx 10^3$

discretisation points. This requires a negligible computational effort compared with the molecular simulation calculation described in the next section.

$N_w\approx 10^3$

discretisation points. This requires a negligible computational effort compared with the molecular simulation calculation described in the next section.

4. The DSMC scheme

The DSMC method is the most prevalent scheme for analysing rarefied gas flows (Bird Reference Bird1994), and is known to provide results that converge to the solution of the Boltzmann equation (Wagner Reference Wagner1992). In its numerical realisation, the physical domain is divided into computational cells and simulation particles are introduced. With each simulation particle representing a large number of real particles, the simulation evolves in time in discrete steps, and particle motions are divided into free-flight and collision parts. In the former, the particles are translated according to their instantaneous velocity. In the latter, collisions are treated in a stochastic manner, following a chosen collision scheme.

In the present work, we applied the two-dimensional Visual DSMC program for two-dimensional flows to analyse the micro-corner problem at finite large Knudsen numbers. By doing so we aim at validating the above free-molecular solution and describe its breakdown with decreasing rarefaction rate. The software has been frequently used as a reliable tool for computing rarefied gas flows, including recent investigations on supersonic jet expansion (Patel Reference Patel2021), compression corner detachment (Li, Yu & Bao Reference Li, Yu and Bao2021), shock-wave detection (Kovacs et al. Reference Kovacs, Passaggaia, Mazellier and Lago2022), microscale reaction–diffusion models (Zhang & Wang Reference Zhang and Wang2023) and curved microchannel flows (Ben-Adva & Manela Reference Ben-Adva and Manela2024). Applying the commonly used ‘no-time-counter’ collision scheme (Bird Reference Bird1994), we consider a hard-sphere gas model of molecular interaction. In each calculation, the micro-corner was initially set in vacuum. Particles were then allowed to enter the computational domain through its outer (circular or straight) open boundary, carrying their Maxwellian outer-flow equilibrium distribution. Outgoing particles were removed from the calculation, and the simulation was followed until a steady state was achieved. In line with the software settings, the simulation time step was taken as

![]() $1/3$

of the mean collision time and the mesh was locally adapted such that each computational cell size was considerably smaller than the local mean free path. Considering the large Knudsen numbers considered, a number of

$1/3$

of the mean collision time and the mesh was locally adapted such that each computational cell size was considerably smaller than the local mean free path. Considering the large Knudsen numbers considered, a number of

![]() $\approx 2\times 10^6$

particles and

$\approx 2\times 10^6$

particles and

![]() $\approx 1\times 10^5$

collision cells proved sufficient to ensure reliably converged results. A single run lasted several hours using an Intel 16-core i7 processor machine, marking a computational effort that is considerably more demanding than the above-described free-molecular calculation.

$\approx 1\times 10^5$

collision cells proved sufficient to ensure reliably converged results. A single run lasted several hours using an Intel 16-core i7 processor machine, marking a computational effort that is considerably more demanding than the above-described free-molecular calculation.

Considering the inevitably low flow speeds characterising the corner edge flow, the application of the DSMC scheme in the present context is particularly challenging, due to the non-large signal-to-noise ratio that typically appears in the results. This, in turn, hinders a detailed description and identification of the vortical flow structure obtained in the vicinity of the corner origin, which is a main focus of the current analysis. To reduce the simulation noise level, averaging over several separate calculations was carried out. Yet, the advantage of the above-described collisionless flow analysis, providing a noise-free description of the high-Knudsen-number flow regime, is evident.

The error margins in DSMC calculations may be assessed either through comparison of high-Knudsen-number computations with the analytical free-molecular solution, or by quantifying the relative change in results via an increase in the number of computational cells and particles. In both cases, our calculations indicate that a doubling of the number of particles and collision cells over the above-reported values impacts the density and temperature fields by less than

![]() $1\,\%$

. Larger deviations of up to

$1\,\%$

. Larger deviations of up to

![]() $\lesssim 5\,\%$

have been observed in the velocity field, a consequence of the characteristically small speed values present in the vicinity of the corner origin.

$\lesssim 5\,\%$

have been observed in the velocity field, a consequence of the characteristically small speed values present in the vicinity of the corner origin.

5. Results

The non-dimensional problem stated in § 2 is governed by the flow Knudsen number

![]() $\textit{Kn}$

, the outer-flow velocity magnitude

$\textit{Kn}$

, the outer-flow velocity magnitude

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

and type (circular or straight), the corner angle

$V_{\textit{out}}$

and type (circular or straight), the corner angle

![]() $2\alpha$

and the surface wall conditions. Focusing primarily on the free-molecular (

$2\alpha$

and the surface wall conditions. Focusing primarily on the free-molecular (

![]() $\textit{Kn}\rightarrow \infty$

) limit, we make use of the ballistic solution to rationalise the effect of problem parameters on the flow pattern in specular-corner (§ 5.1) and diffuse-corner (§ 5.2) set-ups. We then examine the impact of molecular collisions on the system behaviour using DSMC calculations, to validate the free-molecular description and inspect its breakdown with decreasing rarefaction.

$\textit{Kn}\rightarrow \infty$

) limit, we make use of the ballistic solution to rationalise the effect of problem parameters on the flow pattern in specular-corner (§ 5.1) and diffuse-corner (§ 5.2) set-ups. We then examine the impact of molecular collisions on the system behaviour using DSMC calculations, to validate the free-molecular description and inspect its breakdown with decreasing rarefaction.

5.1. Specular-wall corner

Starting with the specular-corner (

![]() $\beta =0$

) set-up, figure 3 presents the kinematic and dynamic divisions of the

$\beta =0$

) set-up, figure 3 presents the kinematic and dynamic divisions of the

![]() $(\alpha ,V_{\textit{out}})$

plane of parameters into domains with different number of maximal wall collisions (

$(\alpha ,V_{\textit{out}})$

plane of parameters into domains with different number of maximal wall collisions (

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

) and vortical structures in the free-molecular flow regime. The dashed vertical lines confine the zones with different

$n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

) and vortical structures in the free-molecular flow regime. The dashed vertical lines confine the zones with different

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

values, and the blue, light blue, green and yellow subdomains mark parameter areas with one, two, three and four vortices, respectively. The numbers and numbers in parentheses denote, in each zone, the number of vortices

$n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

values, and the blue, light blue, green and yellow subdomains mark parameter areas with one, two, three and four vortices, respectively. The numbers and numbers in parentheses denote, in each zone, the number of vortices

![]() $n_{{vor}}$

and the values of

$n_{{vor}}$

and the values of

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

, respectively. The results for the cases of circular and straight outer flows are shown in figures 3(a) and 3(b), respectively, and are based on the solution derived in § 3.1.

$n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

, respectively. The results for the cases of circular and straight outer flows are shown in figures 3(a) and 3(b), respectively, and are based on the solution derived in § 3.1.

Figure 3. Free-molecular kinematic and dynamic division of the

![]() $(\alpha ,V_{\textit{out}})$

plane for a specular-wall corner into domains of different numbers of maximal wall collisions (

$(\alpha ,V_{\textit{out}})$

plane for a specular-wall corner into domains of different numbers of maximal wall collisions (

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

) and vortical structures. The dashed vertical lines confine the zones with different

$n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

) and vortical structures. The dashed vertical lines confine the zones with different

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

values, and the blue, light blue, green and yellow zones mark parameter subdomains with one, two, three and four vortices, respectively. The numbers and numbers in parentheses denote the number of vortices and the value of

$n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

values, and the blue, light blue, green and yellow zones mark parameter subdomains with one, two, three and four vortices, respectively. The numbers and numbers in parentheses denote the number of vortices and the value of

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

in each zone, respectively. (a) Results for circular outer flow and (b) counterpart data for straight external flow. The red circle, triangle and cross notations indicate the parameter combinations referred to in figures 4, 6 and 11, respectively.

$n_{\textit{max}}(\alpha )$

in each zone, respectively. (a) Results for circular outer flow and (b) counterpart data for straight external flow. The red circle, triangle and cross notations indicate the parameter combinations referred to in figures 4, 6 and 11, respectively.

Making use of its common definition, we describe a two-dimensional vortex as a region in the flow field where the fluid revolves about a fixed point. In the free-molecular regime, as well as in other finite-Knudsen-number set-ups, we apply this definition to the gas macroscopic velocity field, calculated via quadrature of the velocity distribution function over the microscopic velocity space, as specified in (3.3). To identify vortices, as discussed below, we seek for stagnation points along the walls as indicators for a change in the velocity direction. This is qualitatively different from the continuum regime, where the no-slip restriction implies that the gas is stagnant along solid boundaries. Advantageously, the high accuracy of the analytical free-molecular solution allows us to resolve the macroscopic flow streamlines and identify the closed recirculation zones with good precision.

Remarkably, the system kinematic (microscopic) and dynamic (macroscopic) descriptions are closely linked. This is unequivocally manifested in figure 3 through the common

![]() $\alpha$

angles separating between set-ups with different maximum number of particle–wall collisions (corresponding to corner angles

$\alpha$

angles separating between set-ups with different maximum number of particle–wall collisions (corresponding to corner angles

![]() $2\alpha ={\pi }/{n_{\textit{max}}}$

, where

$2\alpha ={\pi }/{n_{\textit{max}}}$

, where

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}=3,4,\ldots$

; cf. (3.6)) and different number of corner vortices. In line with (3.6), the

$n_{\textit{max}}=3,4,\ldots$

; cf. (3.6)) and different number of corner vortices. In line with (3.6), the

![]() $\alpha$

intervals pertaining to different

$\alpha$

intervals pertaining to different

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}$

values diminish with decreasing

$n_{\textit{max}}$

values diminish with decreasing

![]() $\alpha$

. At sufficiently low

$\alpha$

. At sufficiently low

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

speeds (

$V_{\textit{out}}$

speeds (

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}\lesssim 1$

),

$V_{\textit{out}}\lesssim 1$

),

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}$

variations are accompanied by an alternating change in

$n_{\textit{max}}$

variations are accompanied by an alternating change in

![]() $n_{{vor}}$

between one (for odd

$n_{{vor}}$

between one (for odd

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}$

) and two (for even

$n_{\textit{max}}$

) and two (for even

![]() $n_{\textit{max}}$

) vortices. At a fixed (and sufficiently low) value of

$n_{\textit{max}}$

) vortices. At a fixed (and sufficiently low) value of

![]() $\alpha$

, an increase in

$\alpha$

, an increase in

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

yields the appearance of multiple vortical structures, which are added in pairs. These features are common in both circular- and straight-flow configurations, indicating that the increase in

$V_{\textit{out}}$

yields the appearance of multiple vortical structures, which are added in pairs. These features are common in both circular- and straight-flow configurations, indicating that the increase in

![]() $n_{{vor}}$

occurs characteristically at lower values of

$n_{{vor}}$

occurs characteristically at lower values of

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

for lower

$V_{\textit{out}}$

for lower

![]() $\alpha$

.

$\alpha$

.

To visualise some of the flow fields described above, figure 4 presents free-molecular velocity amplitude colourmaps and streamlines in a specular-wall corner at the indicated combinations of

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

, also marked by circles in figure 3. Figure 4(a–d) show characteristically low

$V_{\textit{out}}$

, also marked by circles in figure 3. Figure 4(a–d) show characteristically low

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}=0.1$

results for circular (figure 4

a,c) and straight (figure 4

b,d) outer-flow configurations, at

$V_{\textit{out}}=0.1$

results for circular (figure 4

a,c) and straight (figure 4

b,d) outer-flow configurations, at

![]() $\alpha$

values that are slightly below and above

$\alpha$

values that are slightly below and above

![]() $\alpha (n_{\textit{max}}=6)=15^\circ$

. Figures 4(e) and 4(f) then show counterpart data at

$\alpha (n_{\textit{max}}=6)=15^\circ$

. Figures 4(e) and 4(f) then show counterpart data at

![]() $\alpha =14.9^\circ$

and large

$\alpha =14.9^\circ$

and large

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}=2.4$

, for the circular- and straight-flow set-ups, respectively.

$V_{\textit{out}}=2.4$

, for the circular- and straight-flow set-ups, respectively.

Figure 4. Free-molecular velocity amplitude colourmaps and streamlines in a specular-wall corner at the indicated values of the corner semi-angle

![]() $\alpha$

and outer-flow speed

$\alpha$

and outer-flow speed

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}$

for (a,c,e) circular outer flow and (b,d, f) straight outer flow.

$V_{\textit{out}}$

for (a,c,e) circular outer flow and (b,d, f) straight outer flow.

In line with figure 3, figures 4(a,b) and 4(c,d) show flow fields with one and two vortices, respectively, where the added vortex appearing at

![]() $\alpha =15.1^\circ$

is confined to the proximity of the corner origin. While the circular- and straight-flow fields are characteristically similar, higher flow speeds are observed in the former, reflecting the respective larger amount of ‘free-stream’ particles (i.e. that have not collided with the solid walls) that contribute to the corner flow at its outlet section. The maximum flow speed in both cases is nevertheless significantly lower than the outer

$\alpha =15.1^\circ$

is confined to the proximity of the corner origin. While the circular- and straight-flow fields are characteristically similar, higher flow speeds are observed in the former, reflecting the respective larger amount of ‘free-stream’ particles (i.e. that have not collided with the solid walls) that contribute to the corner flow at its outlet section. The maximum flow speed in both cases is nevertheless significantly lower than the outer

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}=0.1$

value, due to the strong effect of particles arriving at the outlet section from inside the corner, which reduce the total speed. At

$V_{\textit{out}}=0.1$

value, due to the strong effect of particles arriving at the outlet section from inside the corner, which reduce the total speed. At

![]() $\alpha =14.9^\circ$

and

$\alpha =14.9^\circ$

and

![]() $V_{\textit{out}}=2.4$

, both circular- and straight-flow set-ups contain three circulation zones that are differently distributed. Specifically, while the vortex centres are symmetrically located along

$V_{\textit{out}}=2.4$

, both circular- and straight-flow set-ups contain three circulation zones that are differently distributed. Specifically, while the vortex centres are symmetrically located along

![]() $\theta =0$

in the circular case in figure 4(e), they are asymmetrically distributed in the counterpart straight-flow configuration in figure 4(f).

$\theta =0$

in the circular case in figure 4(e), they are asymmetrically distributed in the counterpart straight-flow configuration in figure 4(f).

The asymmetric specular-wall vortex distribution, visible in high-speed straight-outer-flow configurations, may be rationalised through the symmetry properties found in the counterpart specular circular-flow set-up, yet missing in the former. To this end, substituting the solution for the specular circular case in (3.11) into (3.3), we obtain expressions for the respective radial and tangential mass fluxes, namely

\begin{align} \begin{split} &\rho u_r(r,\theta ) \\& \quad = \frac {1}{\sqrt {\pi }}\int _0^\infty \left (\sum _i \int _{\varTheta _i(r,\theta )}^{\varTheta _{i+1}(r,\theta )}\xi _r^2\cos (\theta _\xi -\theta ) \exp \big [-\xi _r^2- V_{\textit{out}}^2+(-1)^k 2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}} r \sin (\theta _\xi -\theta )\big ]{\rm d}\theta _\xi \right ) {\rm d}\xi _r \\ &{\rm and} \\ &\rho u_\theta (r,\theta ) \\& \quad = \frac {1}{\sqrt {\pi }}\int _0^\infty \left (\sum _i \int _{\varTheta _i(r,\theta )}^{\varTheta _{i+1}(r,\theta )} \xi _r^2\sin (\theta _\xi -\theta ) \exp \big [-\xi _r^2-V_{\textit{out}}^2+ (-1)^k 2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}} r \sin (\theta _\xi -\theta )\big ]{\rm d}\theta _\xi \right ) {\rm d}\xi _r , \end{split} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{split} &\rho u_r(r,\theta ) \\& \quad = \frac {1}{\sqrt {\pi }}\int _0^\infty \left (\sum _i \int _{\varTheta _i(r,\theta )}^{\varTheta _{i+1}(r,\theta )}\xi _r^2\cos (\theta _\xi -\theta ) \exp \big [-\xi _r^2- V_{\textit{out}}^2+(-1)^k 2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}} r \sin (\theta _\xi -\theta )\big ]{\rm d}\theta _\xi \right ) {\rm d}\xi _r \\ &{\rm and} \\ &\rho u_\theta (r,\theta ) \\& \quad = \frac {1}{\sqrt {\pi }}\int _0^\infty \left (\sum _i \int _{\varTheta _i(r,\theta )}^{\varTheta _{i+1}(r,\theta )} \xi _r^2\sin (\theta _\xi -\theta ) \exp \big [-\xi _r^2-V_{\textit{out}}^2+ (-1)^k 2\xi _r V_{\textit{out}} r \sin (\theta _\xi -\theta )\big ]{\rm d}\theta _\xi \right ) {\rm d}\xi _r , \end{split} \end{align}

respectively. Here,

![]() $\varTheta _i(r,\theta )$

are the direction angles separating, at each

$\varTheta _i(r,\theta )$

are the direction angles separating, at each

![]() $(r,\theta )$

position, section zones with different number of wall collisions (cf. (3.7)) and

$(r,\theta )$

position, section zones with different number of wall collisions (cf. (3.7)) and

![]() $k$