In 1921, a leading Japanese department store, Mitsukoshi, established a “tōyōhinbu” (Oriental goods section) and began to deal in art and artifacts from China, Korea, Taiwan, Java, and India. In the following year, Mitsukoshi's rival, Takashimaya, opened a “shinabu” (Chinese section), which exhibited and sold primarily, but not exclusively, Chinese art and artifacts.Footnote 1 By the 1930s, almost every Japanese department store supplied Asian art and artifacts to its customers.Footnote 2 The emergence of this transnational art market has a correlation with the ideological and discursive construction of “tōyō” (the Orient). Employing an imperialistic claim to Japan's guardianship of Asian cultures, department stores stimulated people's interest in the Orient and created consumer desire for Oriental art and artifacts. On the other hand, the success of the Oriental sections of department stores could also be attributed to the burgeoning urban middle class's craving to partake in an old cultural practice derived from the feudal elite's taste for Chinese and other Asian objects called karamono 唐物. This article reveals how Japanese department stores materialized and sustained Japanese imperial consciousness through the marketing of their Oriental sections and how the stores, capitalizing on Japan's imperial dominance, offered the new middle class opportunities to collect and appreciate Asian art and artifacts that had previously been confined to the elite class.

A few pioneering studies have explored the profound connection between Japanese taste for Oriental art and artifacts and the Japanese imperialist enterprise in the early twentieth century. Jordan Sand (Reference Sand2000) examined the Meiji elite's Western-style rooms decorated with Japanese, Chinese, and other Asian antiquities, and claimed that this interior decorating paralleled and reiterated the Japanese nation and empire building, “orientalizing” the rest of Asia, the West, and the past of Japan itself. Kim Brandt (Reference Brandt2007) and Yuko Kikuchi (Reference Kikuchi2004) have argued that Japanese intellectuals’ celebration and promotion of the folk art of Korea, China, Manchuria, Okinawa, and Southeast Asia mirrored the Japanese state's project to construct a pan-Asian empire. Sand and Brandt also investigated the ways in which Japanese imperial consciousness was commodified as forms of aesthetic objects by Japan's emerging capitalist consumerism. Building on these previous studies, this article examines imperial Japan's Oriental taste by expanding the subjects and objects of this taste. While Sand focused on the aesthetic choices of the Meiji elite during the earlier years of the Japanese empire, when only upper-class Japanese were able to access art and artifacts from Asia, I look at popular interest in Oriental taste during the 1920s and 1930s when Japan achieved enough full-fledged imperial power to offer even its new middle-class households authentic Asian art and artifacts. While the focus of Brandt's and Kikuchi's books were on the mingei movement initiated by Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889–1961) and his circle's admiration of Chosŏn period Korean ceramics, my study includes a wider range of Asian art and artifacts, from antique celadon flower vases to modern literati paintings, which were exhibited and sold at Japanese department stores.

The Oriental sections of Japanese department stores have not been studied, despite their importance as a venue where the movement of artistic goods, people, and knowledge between Japan and its Asian neighbors occurred most actively in the early twentieth century. This article pays attention to this neglected topic. Yet it does not aim to simply add a new case study to the well-established research on Japan's “orientalization” of Asia. It tries to complicate imperial Japan's Oriental taste through the expansion of its subject and object. Whereas the Meiji elite decorated their Western-style rooms with Oriental art and artifacts, following the style and taste of the Victorian West, the new middle class collected Asian art and artifacts in order to make their interior décor closer to the historical Japanese elite's reception room decorated with karamono. Although the folk art of the Japanese colonies and semicolonies was popular among new middle-class customers, their taste for Oriental art and artifacts was not limited to the folk aesthetic, described as childlike, rustic, and primitive. The various Asian objects the feudal elite had admired were welcomed by new middle-class customers at the Oriental sections of department stores. The Oriental taste of imperial Japan cannot be reduced solely to its fascination with other Asian art and artifacts as exotica or its nostalgia for the primitive. This article explores the way in which tōyō shumi 東洋趣味 (Oriental taste) proliferated during the 1920s and 1930s as Japan's Orientalist attitude toward Asia, imported from the West, was entwined with the legacy of Japan's long-standing enthusiasm for imports from Asia.

About Tōyō Shumi

Both Mitsukoshi and Takashimaya stated that they decided to begin selling Asian art and artifacts in response to the rising tōyō shumi (Mitsukoshi 1921b, 24; Takashimaya 1960, 322). How, then, did the stores define and approach tōyō shumi at that time? We can find answers to this question in an article titled “About Tōyō Shumi” that Mitsukoshi published in its in-house magazine of October 1922 to introduce its Oriental section (Mitsukoshi 1922b):

What people call “tōyō” has various meanings. Originally the term “tōyō” was coined by Europeans with Europe as the center. Thus it refers to the entire region from Anatolia to India and China. Japan is also included within it. From the Japanese point of view, it sounds strange to call Anatolia, which is located to the west of Japan, “tōyō.” Strictly speaking, it is still an odd translation for India and China. However, it can't be helped if Europeans took the initiative in calling these regions “tōyō.”

What is now called “tōyō” includes Japan along with India and China. However, the Oriental section of Mitsukoshi is stocking goods from China, Korea, Taiwan, Java, and India, excluding Japan.

Each section of Mitsukoshi is categorized according to the kind and use of its goods. On the other hand, the Oriental section is categorized by the region its goods come from. Consequently, the Oriental section itself seems like a small department store which sells a variety of items, from furniture to table wares, writing implements, and pouches.

Since the goods from the same region are put together, the distinct characteristics of each region, the so-called local color, is well brought out, allowing a wide range of goods to be unified. In other words, Chinese goods have a distinctive Chinese character; Indian goods have a unique Indian aspect throughout the wide range of goods.

In terms of shumi (taste), the goods embody so-called tōyō shumi and make the Oriental section a unified one. Within tōyō shumi, however, shina shumi (Chinese taste), chōsen shumi (Korean taste), indo shumi (Indian taste), and taiwan shumi (Taiwanese taste) exist respectively. Among them, shina shumi is central to tōyō shumi and has been in fashion recently in Japan. China is a nation that developed a culture from ancient times and its taste has something unreachable by others. Various aspects of our taste have been greatly influenced by China for a long time. It is fair to say that today's nihon shumi (Japanese taste) also has its origin in China in numerous cases. Even these days when seiyō shumi (Occidental taste) is prevalent, shina shumi coexists since our ancestors’ taste was inherited by us.

First of all, we can see that the term “tōyō” was understood as a translation of the Western word “Orient.” The Chinese-character word “tōyō” 東洋 was initially used by Chinese merchants to refer to the sea to the east of China, which is what it literally means, but the definition and domain of “tōyō” have changed over time in Japan (S. Tanaka Reference Tanaka1993, 4). In Mitsukoshi's article, which had to appeal to the popular imagination of the time, the origin of the word “tōyō” was forgotten and “tōyō” was conceived as the Orient as defined by Eurocentric cartographic imagery.

The next thing we should note is that the effort to separate Japan from other Asian nations is manifested in the selection of the Oriental section's goods. Japanese department stores most likely modeled their Oriental sections after European and American department stores’ Oriental sections, which had emerged due to the huge popularity of Japonisme and Chinoiserie.Footnote 3 Interestingly enough, however, whereas Japanese art and artifacts, along with those from China, constituted an essential part of the Oriental sections of English and French department stores, Japanese art and artifacts were completely excluded from Mitsukoshi's Oriental section.Footnote 4 As Stefan Tanaka (Reference Tanaka1993) has pointed out, modernizing Japan internalized the gaze of the West toward the Orient and placed Japan in the position of the Orientalist subject, a position that had been occupied by the West. The consciousness, which considered the rest of Asia as “Japan's Orient,” is well reflected in the organization of the Oriental sections of Japanese department stores.Footnote 5

Within the Mitsukoshi store, only the Oriental section was categorized not by use of the goods but by their geographical origin. In an institutional as well as an epistemological sense, the overall layout of Japanese department stores mirrored that of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century international expositions, which distinguished colonial pavilions from main thematic pavilions. According to Timothy Mitchell (Reference Mitchell and Dirks1992, 293), international expositions rendered the Orient as an object on display to be observed and consumed by the dominating European subjects. Just as the colonial displays of the international expositions created the Orient as a spectacle and as a commodity, Japanese department stores presented tōyō itself as an object of consumer desire. The Oriental section marketed the Orient, like the kimono section marketed kimono and the furniture section marketed furniture. In turn, each single object displayed and sold in the Oriental section was treated as a metonym for China, Korea, Taiwan, Java, or India respectively. Each nation or region was regarded as a culturally monolithic entity, whose distinctive taste—local color—was considered to be inherent in all its goods.Footnote 6 The emphasis on the local color of each nation reiterated the cultural essentialism on which Western Orientalist thought was premised.

At the end of the quoted Mitsukoshi article, an interesting twist occurred in the attitude that objectified the rest of Asia as “Japan's Orient.” Whereas French and English department stores created an exotic fantasy about the Orient through their catalogues, posters, and displays to promote their Oriental goods, Mitsukoshi's article rarely employed the rhetoric of exoticism to describe tōyō. Instead, it praised shina shumi as the preeminent source of tōyō shumi and stressed that nihon shumi originated from shina shumi. This statement sounds contradictory to the previously mentioned attempt to separate Japan from its Asian neighbors. Rather, it resonates with the idea of Asianism that claimed a cultural affinity among Asian nations in order to construct a unified entity of Asia countering Western powers. The Mitsukoshi article defined tōyō shumi as an inevitable product resulting from the Oriental origin of Japanese cultures. As the last sentence of the quotation sets “inherited” shina shumi against “imported” seiyō shumi, tōyō represented by shina was considered as “Japan's origin” vis-à-vis seiyō (the West) as the Other of Japan. The contradiction and paradox of tōyō, which was “Japan's Orient” and simultaneously “Japan's origin,” complicated the mechanism of tōyō shumi.

Tōyō Shumi, Japan's Orientalism

If Japan is part of a historically and culturally unified Asia, how could Japan designate its Asian neighbors as the objects of its aesthetic consumption? Japanese department stores forged the Japanese position as the subject in tōyō shumi by Japanese knowledge and appreciation of other Asian cultures rather than by the aesthetic otherness or the exoticness of them. Since department stores first emerged in Japan at the turn of the twentieth century, the stores not only provided the latest goods but also served as purveyors of advanced knowledge about modern cultured life (Hatsuda Reference Tōru1993; Jinno Reference Yuki1994).

Department stores’ prominence as cultural institutions was achieved through their advisory groups, which consisted of well-known intellectuals. The stores invited prominent artists, scholars, and journalists to proffer their advice and expertise on a variety of topics.Footnote 7 By the 1920s, most Japanese department stores were publishing in-house magazines that not only advertised their goods but also included novels and semi-academic articles, and were hosting a variety of events including literary contests, photography contests, lecture series, classical music concerts, and exhibitions. Both the collecting of manuscripts for the magazines and the planning of various cultural events relied on the stores’ intellectual advisors. The close relationship of department stores with the most noted intellectuals of the time also played a crucial role in the business of the Oriental sections.

With the opening of their Oriental sections, department stores actively worked with Asian specialists to seek their expert advice. For example, Takashimaya invited Gotō Asatarō (1881–1945), one of the most renowned specialists in Chinese studies at the time, to be a consultant for its Chinese section.Footnote 8 In addition to Gotō, Kyoto-based Sinologists such as Nagao Uzan (1864–1942) were directly or indirectly engaged in the projects of the Takashimaya Chinese section.Footnote 9 Through the use of catalogues, pamphlets, in-house magazines, and special exhibits, the stores provided their customers with information about the culture and customs of each Asian nation from which their Oriental goods came. It is not hard to find manuscripts written by art historians and curators in the catalogues of exhibitions held at department stores for the sale of Oriental art and artifacts. Masaki Naohiko (principal of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and director of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, 1862–1940); Kobayashi Taichirō (a curator at the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, 1901–63); Hirose Toson (a curator at the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, ?–?); Tanabe Takatsugu (a faculty member at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, 1890–1945); Kawai Kanjirō (a potter and a key figure in the mingei movement, 1890–1966); Okuda Seiichi (founder of the Oriental Ceramic Research Institute, 1883–1955); Asakawa Noritaka (an expert on Korean ceramics, 1884–1964); and others wrote essays for department stores’ publications. In order to enhance the market value of Oriental art and artifacts, the stores asked Asian art specialists to write for their catalogues; in turn, the essays informed and educated the public about Asian art history.

In May 1921, a month before the launch of its Oriental section, Mitsukoshi mounted an exhibit titled “Exhibition of Buddhist Art Materials” (see figure 1). This exhibition displayed photographs, drawings, and rubbings that archaeologist Sekino Tadashi (1868–1935), Buddhologist Tokiwa Daijō (1870–1945), Sinologist Gotō Asatarō, poet and art historian Kinoshita Mokutarō (1885–1945), and artist Kimura Shōhachi (1893–1958) produced during their then recent trips to Buddhist historic remains in China, including the Yungang, Longmen, and Tianlongshan grottoes (Mitsukoshi 1921a). Most of the materials displayed in this exhibition were valuable research resources that had never before been introduced in Japan.Footnote 10

Figure 1. Installation view of “Exhibition of Buddhist Art Materials” (Mitsukoshi 1921a).

Japanese intellectuals’ interest in Chinese cave temples was sparked by European archaeologists’ research on them. In the early twentieth century, European scholars went to study Chinese grottoes located on the Silk Road and brought precious relics from the sites back to their countries. This encouraged Japanese scholars to visit historic sites in China and undertake investigations into them in the name of protection of Chinese arts and cultures abandoned for a long time as a result of China's indifference and threatened recently by Western imperialist ambitions.Footnote 11 Given the fact that China had served as a cultural mentor for Japan over many centuries, the Japan-driven archaeological excavations and investigations of remains and relics in China were an effective way for Japan to take cultural hegemony away from China and reverse the cultural hierarchy in Asia.

Mitsukoshi's exhibition, which introduced prominent Japanese intellectuals’ scientific studies and aesthetic appreciation of Buddhist relics in China, not only stimulated public interest in Chinese arts and cultures but also inculcated cultural confidence in the Japanese public by propagating the idea that Japan, as the only modern nation in Asia on par with the West, had exclusive authority to study, collect, appreciate, and preserve Asia's artistic achievements. Japanese department stores endeavored to convert such newly acquired intellectual and cultural confidence into a desire to consume artistic objects from other Asian nations. This is why Mitsukoshi, despite being a profit-oriented institution, held such a seemingly purely academic exhibition that did not bring immediate commercial benefits.

The claim for Japan's credentials as the guardian of Asian arts and cultures was not new. In 1903, Okakura Kakuzō (1862–1913) had already asserted Japan's special role in the preservation and appreciation of the once-great and unified Asiatic civilization in his book The Ideals of the East. However, this book was initially published in English in London and took almost twenty years to be translated into Japanese. The idea of “Japan as a museum of Asiatic civilization” had existed only in a few elite nationalists’ minds, and had not been prevalent in the popular imagination in Meiji Japan.Footnote 12

It is noteworthy that a series of cultural movements demonstrating various Japanese subjects’ interest in Chinese and Korean arts and cultures occurred simultaneously around the time when Mitsukoshi and Takashimaya opened their Oriental sections. In the year 1922, the general-interest magazine Chūō Kōron published a special issue on “research on shina shumi,” the art journal Kokka’s February issue included an article titled “Our People's Interest in Chinese Studies,” the literary magazine Shirakaba devoted a special issue to “Richō ceramics” (Yi dynasty Korean ceramics), the monthly art magazine Shina Bijutsu (Chinese Art) was first issued, and Japanese art dealers in colonial Seoul founded a “Keijo bijutsu kurabu” (Seoul art club).Footnote 13 Only around then was Okakura's ideal implemented by the Japanese public.

The explosion of Japanese popular understanding of and interest in Asian arts in the early 1920s was inseparable from a transition in the Japanese state's strategy to gain ascendancy over other Asian nations. After the end of World War I, anti-Japanese nationalism arose in Asia. The March First Movement of Korea and the May Fourth Movement of China in 1919 triggered a major turn in Japan's foreign and colonial policy. In Korea, the Japanese colonial government replaced “budan seiji” (military rule) with “bunka seiji” (cultural rule), promising increased educational opportunity for Koreans, permission for the publication of Korean-language newspapers, and general respect for Korean culture. For example, Yanagi's plan for the construction of the Korean Art Museum (Chōsen Minzoku Bijutsukan) was able to be realized with the support of the colonial government as part of bunka seiji (Brandt Reference Brandt2007, 26). For China, the Japanese foreign ministry undertook “Taishi Bunka Jigyō” (Japanese Cultural Project toward China) with the plan of founding research institutions in both China and Japan, inviting Chinese students to Japan, and supporting cultural exchange programs between the two countries. Chinese painting exhibitions such as “Exhibition of Masterpieces from Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties” (1928) were held in Japan with the sponsorship of this project (Kuze Reference Kanako2014). Art was an important apparatus taken by the new colonial and foreign policies to show Japanese respect for Korean and Chinese cultures. Among the specialists who wrote for department stores’ Oriental art exhibitions, Masaki Naohiko, Tanabe Takatsugu, and Kobayashi Taichirō were also engaged in the Taishi Bunka Jigyō or the projects carried out under bunka seiji.Footnote 14 In other words, the same scholars worked for both the imperial state's cultural projects toward Asia and the department stores’ marketing of Asian art and artifacts, popularizing their expertise on Asian arts and cultures. The aesthetic respect for other Asian cultures was, in fact, the most colonialistic attitude that Japan could take toward Asia. Karatani Kōjin (Reference Kōjin1997, 48) argued that aesthetic appreciation was possible only in the consciousness that people who made the works were or could be colonized at any time. According to his theory, the Japanese were able to express aesthetic respect for other Asian cultures only after Japan had established political and economic domination as well as intellectual and ethical superiority over other Asian nations. It was the 1920s when the Japanese acquired enough confidence, built on Japan's imperial power, to aesthetically acknowledge and embrace other Asian cultures.

It is not unrelated as well to Japanese imperial confidence that nanga (southern painting), which had originated from Chinese bunjinga (literati painting), came to be reappraised from the late 1910s in Japan. Chiba Kei (Reference Kei2003) argued convincingly that a change in the evaluation of nanga reflects a transition in Japanese political interest from nationalism to imperialism. During the 1880s and 1890s, nanga had been completely devalued and rejected by Okakura Kakuzō and Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) in the course of constructing the tradition of nihonga (Japanese painting) around the ideological axis of nationalism. Contradictory to his arguments in The Ideals of the East about a decade later, Okakura had criticized nanga as a “Sinophile” and excluded it from the two most important projects that he participated in to institutionalize the “national art” of Japan: the establishment of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and the publication of the art journal Kokka. Nanga was neither included in the curriculum of the nihonga department of the school when it opened in 1889 nor covered in Kokka when it was first issued in the same year.Footnote 15 While nanga was rejected during the 1880s and 1890s owing to its Chinese origin, it was revived and reappraised as a key element of tōyō bijutsu (Oriental art) during the 1910s and 1920s.

The resurgent popularity of nanga not only recuperated the tradition of nanga within Japanese art history but also aroused interest in contemporary Chinese bunjinga. Mitsukoshi and Takashimaya regularly held exhibitions of contemporary Chinese bunjinga painters including Wu Changshou (1844–1927), Wang Yiting (1866–1938), and Qi Baishi (1864–1957), whose works were highly regarded and enjoyed great commercial success in 1920s and 1930s Japan (Matsumura Reference Shigeki2005; Wong Reference Wong2006, 95). Other department stores did not overlook the marketability of contemporary Chinese bunjinga either. Ueno Matsuzakaya held “Exhibition of Wang Mengbai's Paintings” in 1929 and “Exhibition of Shanghai's New Famous Painters” in 1930. Osaka Hankyu held “Exhibition of Qi Baishi and Wang Yiting's Recent Works” in 1936 and “Exhibition of Qi Baishi's Recent Works” in 1938. The exhibitions of contemporary Chinese bunjinga painters were handled by both Oriental sections and art sections of the stores. Occasionally bunjinga paintings were exhibited together with other Chinese artifacts, as in Mitsukoshi's “Contemporary Chinese Painting and Ceramic Exhibition” in March 1922 (see figure 2).

Figure 2. “Contemporary Chinese Painting and Ceramic Exhibition” (Mitsukoshi 1922a).

Department stores propagated Japan's authority over Asian arts and cultures not only through special exhibitions like the “Exhibition of Buddhist Art Materials” but also through regular sales in their Oriental sections. The stores endeavored to provide scholarly information about Oriental art in order to help their customers acquire the cultural pride and confidence to collect and appreciate Oriental art and artifacts. The catalogues of the Oriental sections not merely featured the objects for sale with their images and descriptions but often offered art historical knowledge about the objects. Takashimaya's Chinese section held an “Exhibition of Chinese Ceramic Flower Vases” in July 1924, displaying about one hundred antique ceramics produced during the period of the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. All works on display were destined for sale. Takashimaya published a tabloid-size pamphlet for the exhibition with images of selected works and a price list for all of the works (Takashimaya 1924c; see figure 3). On the first page of the pamphlet, a brief history of Chinese ceramics was included, giving a lesson in their origins, techniques, and styles by region and kilns. With the success of this exhibition, which sold out, Takashimaya organized another Chinese ceramic flower vase exhibition, which focused on Ming and Qing ceramics, in November of the same year. A promotional pamphlet was also published (Takashimaya 1924a; see figure 4). The highlights of the exhibition were introduced first and art historical information followed, this time providing a more in-depth lesson on Chinese celadons. Since these pamphlets did not name their authors, it is difficult to determine who actually wrote them. Given the fact that Takashimaya invited China specialists to be consultants for its Chinese section, an expert adviser might have been involved in creating the content. At the “Exhibition of Chinese Antique Ink Stones” held in March 1925, Takashimaya exhibited pieces of old ink stones that Gotō Asatarō had selected among its new collection of ink stones imported from China. The Chinese section also produced a pamphlet that provided various kinds of information, from how to discern a good ink stone to how to use it appropriately (Takashimaya 1925).

Figure 3. Takashimaya pamphlet for the “Chinese Ceramic Flower Vase Exhibition” held in July 1924 (Takashimaya 1924c).

Figure 4. Takashimaya pamphlet for “The Second Chinese Ceramic Flower Vase Exhibition” held in November 1924 (Takashimaya 1924a).

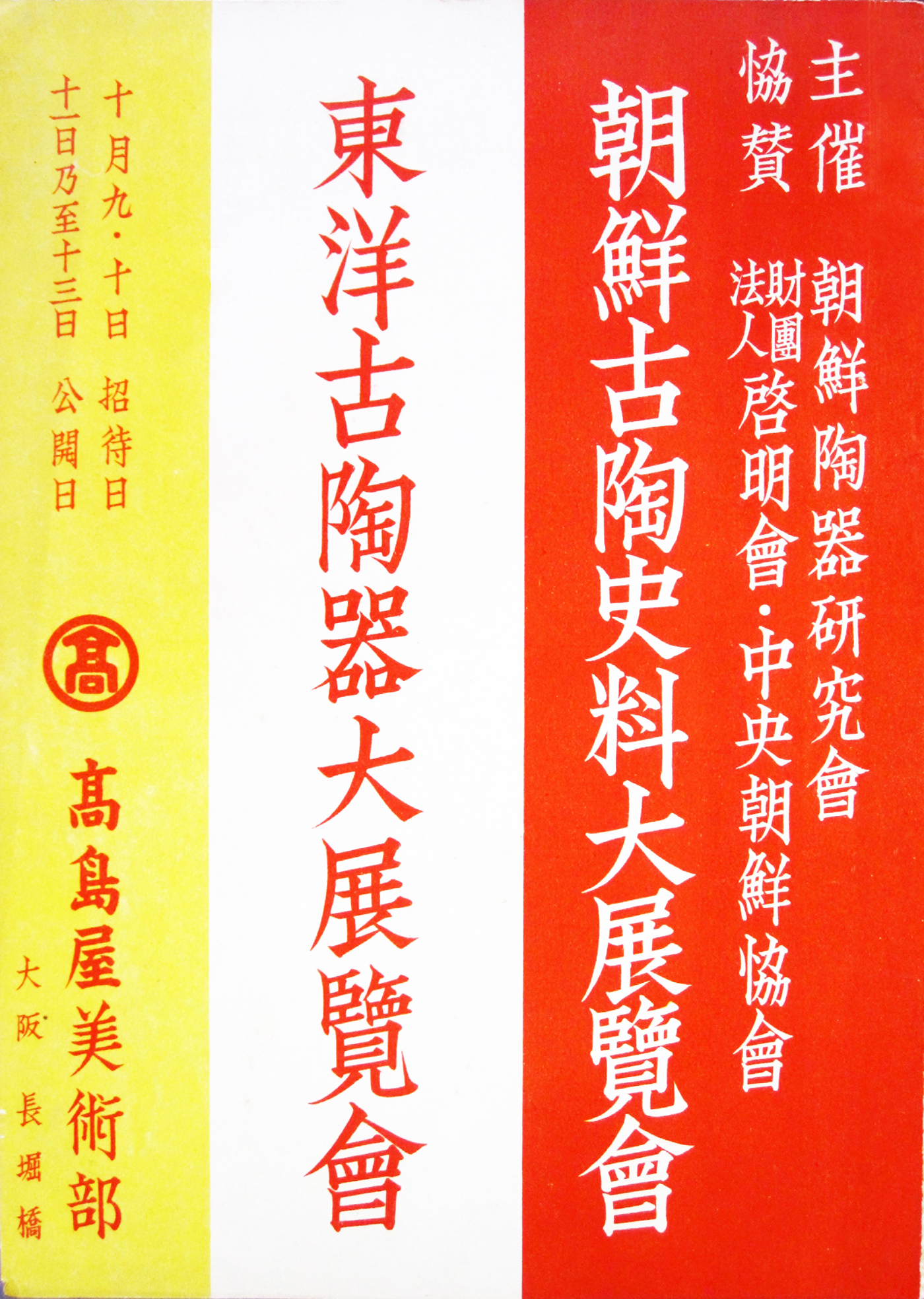

Ultimately the exhibits and publications that department stores produced for the marketing of Oriental art and artifacts contributed to the distribution of Japan's colonial knowledge about tōyō. An “Exhibition of Historical Materials of Korean Antique Ceramics” was held in Tokyo Shirokiya in July 1934 and then in Osaka Takashimaya in October of the same year. This exhibition introduced the results of Asakawa Noritaka's twenty years of research on Korean ceramics. Asakawa Noritaka is well known as a pioneer in the study of Korean ceramics along with his brother Takumi (1891–1931), and he is also famous for introducing Chosŏn ceramics to Yanagi Muneyoshi. At the exhibition, ten thousand ceramic sherds collected by Asakawa from four hundred old kiln sites throughout the Korean peninsula were displayed chronologically, geographically, according to shape, and according to technique. On the wall, information panels were installed to help the audience to understand the content of the exhibition, and the illustrated panels among them showing the production process and the structure of Korean kilns were reproduced in the exhibition catalogue (Shirokiya 1934). During the period of the exhibition in Shirokiya, Asakawa gave public lectures over the course of three days on “periodic changes in Korean ceramics,” “ceramics made in Yi dynasty's official kilns,” and “Korean tea bowls in our country” respectively.Footnote 16

Regarding this exhibition, there is an interesting photo published in the Takashimaya catalogue (see figures 5 and 6).Footnote 17 The photo depicts Yi Eun (1897–1970), King of Korea and his wife Bangja (Masako Nashimoto, 1901–89), who were viewing the Korean ceramics on display while listening to Asakawa's explanations.Footnote 18 Certainly this picture was very useful in advertising the exhibition as authoritative enough that the king of Korea came to see it in person. More importantly, the photo clearly demonstrates who is the subject of this art historical research and who is the object of this educative exhibition. Here the king of Korea was being taught about the artistic objects of “his” country, which were collected, studied, and exhibited by the Japanese. The organizer of this exhibition was the Korean Ceramic Research Group (Chōsen Tōki Kenkyūkai), which was formed in 1929 to support Asakawa Noritaka's research.Footnote 19 On the first page of the exhibition catalogue, the prospectus of the research group was reprinted. Not surprisingly, the main point of the prospectus was to convey that only Japanese could conduct scientific research on the sites of old and new kilns on the Korean peninsula and save the tradition of Korean ceramics from the threat of extinction. The content of the exhibition was seemingly academic and educational. However, it is undeniable that the exhibition contributed to the production of Japan's intellectual ascendancy over Korea and the justification of Japan's colonization of Korea. Japan's identity as the “civilized” nation, which was the basis for its right to represent, protect, and even rule other Asian nations, could not have existed prior to its domination of them, but rather was being constructed through the very process of investigating, collecting, and consuming Asian arts and cultures. Department stores’ exhibits and sales of Asian art and artifacts played a significant role in the process.

Figure 5. Catalogue of “Exhibition of Historical Materials of Korean Antique Ceramics” held in the Osaka Takashimaya in October 1934 (Takashimaya 1934).

Figure 6. Yi Eun and his wife at “Exhibition of Historical Materials of Korean Antique Ceramics” held in the Tokyo Shirokiya in July 1934 (Takashimaya 1934).

Japanese access to Asian artworks was facilitated by Japan's imperial power in East Asia. Not only local art dealers but also Japanese consulate offices or colonial governments sometimes engaged in the supply of Oriental art and artifacts to be sold in department stores. In a pamphlet published for an exhibition of famous products from Fuzhou in July 1924, Takashimaya (1924b) stressed the rarity of its Chinese goods by saying, “It is very difficult even for Chinese high officials to get colored lacquerware made in Fuzhou, but it is possible for us to procure them by a favor of the Japanese Consulate General in Fuzhou.” As for the works from Korea, the involvement of the colonial government appeared in a more formal and extensive way. A good example was the “Korean Old Art and Craft Exhibition,” which was held in Tokyo and Osaka from 1934 to 1941. Among a total of seven exhibitions, the fourth to seventh took place under the auspices of the Government-General of Korea (GGK, Chōsen Sōtokufu) (see figure 7). For this series of Korean art and crafts exhibitions, a Korean art dealer, Lee Heeseop, supplied works he gathered from every corner of Korea, and Japanese department stores provided exhibition venues and potential consumers.Footnote 20 In 1932 in Seoul, Lee Heeseop met Tanabe Takatsugu, who came to serve as a judge of the Chōsen Bijutsu Tenrnaki, and expressed his desire to hold a Korean craft exhibition in Japan (Park Reference Jeoung2015, 452). At the recommendation of Tanabe, Masaki Naohiko, then the director of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, viewed first in Seoul the works Lee collected and helped bring them to exhibit in Japan (Asahi Shinbun 1934). The Korean Craft Research Group (Chōsen Kōgei Kenkyūkai) was founded with renowned Japanese artists to serve as the organizer of the exhibitions.Footnote 21 Furthermore, the GGK officially supported the exhibitions from the fourth on. For every exhibition, one to three thousand pieces of Korean art and artifacts were brought to Japan. The exhibitions showed a comprehensive selection of Korean art in terms of genre, from ceramics, metalwork, lacquerware, Buddhist sculpture, and stonework to furniture, and in terms of period from Nakrang relics to Chosŏn products. The quality of the works was also high. Not a few works displayed and sold at the exhibitions had been introduced in the Album of Korean Antiquities (Chōsen Koseki Zufu), published by the GGK. The GGK hired Japanese scholars including Sekino Tadashi to investigate and document ancient sites and relics across the Korean peninsula and published the results as the fifteen-volume series entitled Album of Korean Antiquities between 1915 and 1935 (Pai Reference Pai2000, 32). The artworks included in the album came to be established as the representative works of Korean art through this institutional validation. It would have been virtually impossible for the “Korean Old Art and Craft Exhibition” to exhibit and export such a large volume of superb Korean arts and crafts over a period of many years without the support of the GGK.Footnote 22

Figure 7. Advertisement for “Korean Old Art and Craft Exhibition” (Asahi Shinbun 1939).

Japanese department stores developed their Oriental sections against the background of Japan's imperial expansion. They not merely appropriated the discourse of tōyō, which was politically and academically constituted by state officials and intellectuals, but also materialized this ideological construct through their exhibitions and sales of Oriental objects. The Oriental sections of the stores had a particularly strong influence in shaping the general public's attitudes toward and images of tōyō. As is well illustrated in Tony Bennett's (Reference Bennett1988) article on the exhibitionary complex, department stores were one of the modern institutions that through the display of objects articulated power relations and inculcated them in the general public. Shopping for Oriental art and artifacts at department stores offered Japanese people an opportunity to envision the imagined space of tōyō as well as Japan's privileged position in tōyō. The aesthetic and intellectual consumption of Oriental art and artifacts was promoted as a way to demonstrate Japan's superiority over the other parts of Asia, ultimately consolidating Japan's cultural hegemony in Asia.

The Oriental Section, the Legacy of Karamonoya

In addition to Japan's growing confidence as the guardian of Asian arts and cultures, an increase in the number of consumers who had an interest in and the ability to purchase Asian art and artifacts was a prerequisite for the establishment of Oriental sections in department stores. The Oriental sections came into being as part of the department stores’ expansion of their business in the 1920s. The 1920s was an era colored by the explosive growth of urban mass consumer culture in Japan. During World War I, Japanese industry expanded rapidly as Japan served as a wartime supplier to the Allies and increased its trade with other Asian nations by supplying goods that could no longer be imported from Europe. This unprecedented industrial expansion reordered the social and economic structure of Japan. Large numbers of rural dwellers migrated to urban areas and constituted the white-collar workers referred to as the “new middle class,” distinguishing them from the “old middle class” of shopkeepers and small landowners.Footnote 23 By the 1920s, about 10 percent of the nation's households belonged to the new middle class, and this percentage was doubled in urban areas.Footnote 24 The primary customer of department stores was from this rising urban middle class that consisted of civil servants, office workers, schoolteachers, and other professional workers (Oh Reference Oh2014, 353–54). Due to a combination of increased prosperity and greater purchasing power, consumption and leisure in everyday life expanded, particularly in the big cities. Mitsukoshi opened its Oriental section with other new sections dealing with medicine, musical instruments, sports equipment, and books when it enlarged its premises in 1921. Takashimaya inaugurated its Chinese section with the completion of the new building for its main store in Osaka in 1922.

As Louise Young (Reference Young1999) argued, department stores played a crucial role in creating the norms and behaviors of the new middle class in Japan. Department stores attracted customers from the new middle class by providing them with the latest goods required to enjoy a modern, cultured lifestyle. In addition, the stores offered their customers lessons on the novel forms of social relationships and practices related to these modern goods, often Western imports, through in-house magazines and various cultural events. By associating themselves with the cultured life, white-collar workers placed themselves in a different social category from factory laborers, although their salaries might not be higher than the wages of a skilled manual laborer (Gordon Reference Gordon, Zunz, Schoppa and Hiwatari2002, 115). After education and occupation, taste played a significant role in defining membership in the new middle class and the appeal of belonging to it (Oh Reference Oh2014, 354–55). In particular, the taste revealed in the interior décor of a household not only served to mark the social status of the household but also came to determine it within the fluid social conditions of modern Japan. Accordingly, goods associated with the decoration of domestic interiors were one of the core businesses of department stores.Footnote 25

In general, the ideal lifestyle that the new middle class sought was a Westernized one. Interestingly enough, however, the new middle class shared the common dream to reside in a house that was furnished with tokonoma 床の間 (decorative alcoves) (Mori Reference Hitoshi and Fumitarō2007, 296). Historically t okonoma had been a symbol and prerogative of the elite houses to which commoners had not been entitled.Footnote 26 As the old restrictions on the use of tokonoma were lifted with the Meiji Restoration (1868), tokonoma proliferated so extensively in the houses of the new middle class that regardless of architectural style, either Japanese-style or combined Japanese-Western style, most houses had tokonoma in the study or reception room. In an architectural pattern book published in 1913, ninety-nine out of one hundred house plans had tokonoma. Footnote 27 The only one without tokonoma was for a one-room house. Tokonoma were prevalent even in modern, Western-style apartments that Dōjunkai built after the Great Kantō Earthquake (1923) to provide collective housing in the Tokyo area (see figure 8). The liberation of tokonoma from feudal restrictions abolished the exclusive right of elite households not just to have tokonoma per se but also to partake in cultural practices around that space. T okonoma decorating became de rigueur among new middle-class households.

Figure 8. Interior of a room for the householder, Edogawa apartment (Architectural Japan 1936).

The expansion of tokonoma into the homes of the new middle class led to a significant increase in demand for artistic objects that could be used for this interior space. Even before opening their Oriental sections, department stores had already supplied works of art needed for tokonoma decorating through “bijutsubu” (art sections), which displayed and sold works of contemporary Japanese artists (Jinno Reference Yuki2015, 89–114; Oh Reference Oh2014). In 1907, Mitsukoshi was the first to establish an art section, and other department stores followed suit. To help customers imagine how their houses would look when they were decorated with the works of art on sale, department stores occasionally built a Japanese-style model room furnished with tatami (woven straw mats), tokonoma, and chigaidana (staggered shelves) for the display of art (see figure 9). To the new middle-class customers who had been alienated from tokonoma decorating, the formalities of this elite cultural practice were as foreign as the recently imported Western customs and goods. The stores provided their customers with lessons on the proper placement of artistic objects and the meanings of this cultural practice through their model rooms and in-house magazines. Takashimaya serialized “The Way of Reception Room Decoration” (Ozashiki no Kazarikata) in the 1921 issues of Takashimaya Bijutsu Gahō (Takashimaya Art Pictorial Magazine), giving detailed instructions on which theme of painting should be displayed in tokonoma according to the season, and how flower vases and other decorative objects should be arranged in tokonoma and chigaidana (Takashimaya Bijutsu Gahō 1921a, 1921b).

Figure 9. Tokonoma decoration for spring (Mitsukoshi 1916).

The emergence of the Oriental sections in Japanese department stores was related to their new middle-class customers’ desire to adopt the feudal elite class's zashiki (reception room) decorated with karamono in their homes. The term “karamono” literally means “things of Tang China.” However, it was used more broadly to refer to objects that were imported into Japan from Korea and South and Southeast Asia as well as China during the medieval and early modern periods. Japanese taste for Asian objects had existed well before the rise of Japan's imperialistic ambitions. The Japanese royal court had already sent missions called k entōshi to Tang China to learn from Chinese culture and institutions during the seventh to ninth centuries. The interest in karamono increased considerably in the Kamakura period (1185–1333) when Japan's trade with the Asian continent developed and Chinese Zen Buddhist monks entered Japan. The taste for karamono, called “karamono suki,” exploded during the Muromachi period (1333–1573) with the Ashikaga shoguns’ adoration for imported objects. Karamono served as a cultural signifier of the Ashikaga shogunate's power and authority as well as a political apparatus with which it both competed with and cultivated relationships with the imperial court and court nobles.Footnote 28 The formal reception room in the medieval elite's residence was decorated with karamono such as Song and Yuan dynasty paintings, flower vases, candleholders, incense burners and containers, trays, tables, and writing implements. Distinctive spaces in Japanese architecture such as tokonoma, chigaidana, and tsukeshoin (built-in desks) were first designed to display these imported objects. In other words, the desire to show off karamono created new forms of architecture to accommodate these new modes in social behavior and cultural life.Footnote 29 It is safe to say that in Japan the cultural practice of collecting and displaying artistic objects evolved from the taste for karamono. On the other hand, the establishment of the chanoyu (tea ceremony) as an essential part of elite social intercourse in the late fifteenth century contributed to the prevalence of karamono suki as well. Karamono were often collected with the intention of using or displaying them during tea gatherings. Despite the Tokugawa shogunate's seclusion policy, the phenomenon of karamono suki continued with a supply of karamono imported via Nagasaki during the Edo period (1603–1868). The Tokugawa shogunate's promotion of Confucianism as a means of keeping social order and norms stimulated interest in Chinese literati culture. Scholarly avocations including studying poetry, calligraphy, and painting; collecting antiquities and writing implements; and enjoying tea (sencha) became essential accomplishments for the samurai class (Graham Reference Graham and Pitelka2003).

Since knowledge of the Chinese language and classics and the wealth to afford luxury imports were available only to a privileged few such as imperial aristocrats, Buddhist priests, and high-ranking samurai, ownership of karamono played a significant part in differentiating elites from commoners and creating social distinctions. As a consequence, “kara” of karamono indicated not only the “foreign-ness” of its producers but also the “elite-ness” of its consumers. The continued strong desire for karamono in Japanese history grew out of an admiration for good taste and the education of the native elite class as well as out of curiosity about advanced material and cultural products from other parts of Asia. In particular, a rising class that newly acquired political or economic power strove to gain respect and prestige within Japanese society by involving itself in cultural practices associated with karamono. With the rise of the Kamakura shogunate, the samurai class deployed its taste for karamono to legitimize and preserve its social position vis-à-vis the imperial court and the old aristocracy. By the sixteenth century, new clientele for karamono emerged among wealthy urban merchants (machishū) who aspired to attain social parity with the elite members of society by participating in the practice of chanoyu and collecting karamono. Eventually, the growing demand for karamono gave birth to karamonoya (traders or shops specializing in karamono) in urban centers in the Edo period.Footnote 30 The proliferation of karamonoya made it possible for an increasing number of aspiring chōnin (townsmen) to take up the cultural practices that had previously been confined to the elite class.

Karamonoya supplied a wide variety of imports including teaware, incense burners, bronze vessels, flower vases, lacquerware, ceramics, Chinese paintings, writing implements, gold and silver objects, silks, brocades, sarasa (South Asian woodblock-printed cotton textiles), rugs, and furnishings. Interestingly enough, the items sold at karamonoya overlapped considerably with those sold in the Oriental sections of department stores in the 1920s and 1930s. The items that Mitsukoshi sold in its Oriental section included the following:

Items from China: ink stones; ink sticks; brushes; gems for seals; ceramics (celadon, namakote-style wares, blue and white porcelains) used as flower vases, incense burners, water jars, and stools; rosewood products; silks and satins; Tianjin carpets; bamboo works; fans; and rugs colored in red, white, and yellow

Items from Korea: products of the Yi Royal Household Art Workshop (Riōke Bijutsu Seisakujo) including ceramics, mother-of-pearl works, and bronze vessels; antiques

Items from Taiwan: rush mats, Carludovica tobacco pouches, insoles of geta sandals, bamboo mats, rattan products, works made of camphor wood, and camphor

Items from India: sarasa, wooden toys, glassworks, terracotta pottery

Items from Java: sarasa. (Mitsukoshi 1921b)

Although Takashimaya focused on Chinese objects, the items it was dealing with were not much different from those of Mitsukoshi. Takashimaya had its local office on Kunzan Street in Shanghai and imported ink stones, ink sticks, brushes, paper, and h ō jō (copybooks printed with reproductions of the works of old masters of calligraphy). It also sold ceramics, rosewood products, lacquerware, Chinese braziers, and textiles (Takashimaya 1960, 322). Most of the items sold in department store Oriental sections were objects used primarily for reception room decorating (zashiki kazari), which centered around the display of artistic objects in tokonoma.

With the establishment of their Oriental sections, department stores supplemented the repertoire of the art section, which was limited to the sale of Japanese arts and crafts, with art and artifacts imported from China, Korea, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Given the fact that tokonoma were initially installed in reception rooms to display karamono, the Oriental sections not only added variety to the artistic objects displayed in the new middle class's tokonoma, but also made their tokonoma decoration more “authentic.” The new Japanese middle class decorated their tokonoma on the model of the feudal elite's, just as the European bourgeoisie emulated aristocratic taste for the interior decorating of their houses. Most interior decorating advice manuals, including the above-mentioned Takashimaya's “The Way of Reception Room Decoration,” which the new middle class referred to, were modeled on Kundaikan Sōchōki written in the Muromachi period (see, e.g., Inoue Reference Sigejirō1909; Kondō Reference Shōichi1910; Sugimoto Reference Fumitarō1910, Reference Fumitarō1911, Reference Fumitarō1912a, Reference Fumitarō1912b, Reference Fumitarō1912c). Kundaikan Sōchōki was compiled by art stewards Nōami (1397–1471) and Sōami (1465–1523), who were caring for the art collection assembled by successive generations of Ashikaga shoguns. This book not only recorded the appraisal of paintings and crafts in its collection but also codified with illustrations the appropriate selection and placement of those artistic objects in a reception room for a variety of seasons and particular occasions. Kundaikan Sōchōki had served as a means of disseminating the rules of formal reception room decorating and continued to be the principal reference work even for modern interior decorating manuals. The more conservative and the closer to the feudal elite's zashiki kazari an interior decorating style was, the more authentic and the more authoritative the style was considered to be.

Discerning this cultural trend, department stores emphasized the historical authenticity of the Asian art and artifacts that they exhibited and sold. For example, when Takashimaya held an exhibition of antique ceramics imported from the Malay Archipelago and New Guinea in 1941, it was highlighted that the southern ceramics had been admired enthusiastically by tea masters since the Ashikaga period and were proudly displayed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–98) when he invited daimyos to an exhibit he held at the Osaka castle (Takashimaya 1941). In 1937, Takashimaya held an “Exhibition of Nanban Old Pottery” and called pottery of southern islands on display “nanban yaki” (Takashimaya 1937). “Nanban yaki” is a term that refers to pottery that had been imported from southern China, the South Sea islands, the Philippines, Vietnam, and so on via the Nanban trade (Japan's trade with Spain and Portugal) from the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries. Thus, strictly speaking, the pottery imported into Japan in the twentieth century is not nanban yaki, although it came from the same region. However, Takashimaya deliberately called it nanban yaki and included a short article titled “About Nanban Yaki” in the catalogue of the exhibition, providing information about its kinds and origins. Such emphasis on nanban yaki by Takashimaya demonstrates how important the historicity of the objects was in the marketing of department stores’ exhibits and sales of Asian art and artifacts. The ownership of historical nanban yaki had apparently been available only to a narrow segment of elite society. The Takashimaya article praised the Japanese aesthetic discernment that had discovered the beauty of nanban yaki as much as it praised the beauty of nanban yaki itself.

It was Japan's imperial dominance in Asia that enabled the new middle class to participate in the practice of collecting karamono, which had previously been limited to the social elite who had the economic means to afford these objects and the cultural capacity to appreciate them. The disparity of political and economic power between the metropole and colonies or occupied territories allowed an unprecedented volume of artistic objects from other parts of Asia to flood Japan. Greater quantities of antiquities that had belonged to the Chinese royal court and aristocratic families were dispersed in the social disarray following the Boxer Rebellion in 1901 and the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912. Many burial objects surfaced while the Chinese Eastern Railway and South Manchurian Railway were being constructed across northeastern China by Russia and Japan. In the Korean peninsula, since the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) legal and illegal excavations and robberies abounded in order to unearth ancient artistic objects (Chŏng Reference Kyuhong2009; Yi Reference Kuyŏl1996). As the pressure of the imperial powers deconstructed the old, long-standing order within East Asia, artworks that had previously been out of circulation poured into the market in the midst of this turmoil. Under the deteriorating political and economic conditions of China and Korea, a large number of Japanese art dealers entered those countries and swept through their art markets, where good-quality objects could be acquired for reasonable prices.Footnote 31 The surge in imported art and artifacts from Asia shaped the new Japanese art market, targeting new middle-class households whose desire for cultural consumption was increasing.

Department stores decided to open Oriental sections with the assurance that Asian art and artifacts would become a popular commodity desired not just by a small number of art collectors and experts but even by those who had never before bought from antique shops or art dealers. At the above-mentioned “Exhibition of Chinese Ceramic Flower Vases” held at Takashimaya in 1924, the price range of the antique ceramics on display was wide, from 3 yen to 500 yen. Yet more than half of the pieces were priced under 50 yen. Given that the starting salary for a bank employee at that time was between 50 yen and 70 yen per month, the prices of Chinese antique ceramics sold at Takashimaya still represented substantial sums of money for new middle-class households.Footnote 32 However, the price was not so high that they could not even consider a purchase. After 1868, the great art collections amassed over the centuries by daimyo, aristocrats, and temples were dispersed with the social reordering of the Restoration. New Meiji elite such as entrepreneurial capitalists and high-ranking government officials competitively collected meibutsu (famous objects) that had once belonged to renowned feudal elites (Guth Reference Guth1993). Considering the fact that tens of thousands of yen were bid at auctions for meibutsu, the majority of which were karamono, it is understandable why department stores’ offerings of Oriental art and artifacts were so popular that they often sold out in an instant.

Capitalizing on the asymmetrical power relations between Japan and its colonies or semi-colonies, department stores provided the new middle class with both affordable Asian art and artifacts and the cultural confidence to appreciate them. As discussed earlier, department stores popularized knowledge of Asian arts through their exhibitions and catalogues produced in cooperation with intellectuals of the time. This allowed the new middle class access to knowledge and aesthetic discrimination that had been monopolized by the elite. Through the collection of Asian art and artifacts, a modern version of karamono, the new middle class assumed the social prestige associated with the historical Japanese elite. Japan's colonial opportunities in Asia made it possible for its new middle-class households to amass cultural capital, which determined their social position.

Conclusion

The identity of modern Japan was constructed in the constant oscillation between “datsu-a” (leaving Asia) and “kō-a” (raising Asia). The dilemma that Japan faced in needing to separate itself from Asia to hold hegemony over its Asian neighbors but at the same time needing to return to Asia to counter the encroachment of the West formulated the imagined geo-cultural entity “tōyō,” which was both “Japan's Orient” and “Japan's origin.” This ambivalence of tōyō allowed tōyō shumi to work as a kind of Orientalism and simultaneously to inherit the long-standing reverence for karamono.

It might sound contradictory to interpret tōyō shumi as both Japan's Orientalism and the legacy of the penchant for karamono because the former was premised on Japan's sense of superiority over its Asian neighbors but the latter was based on Japan's sense of respect for them. Interestingly enough, however, imperial Japan's desire for cultural power, which was articulated by internalizing the West's Orientalist attitude toward Asia, and the new Japanese middle class's desire for cultural capital, which was manifested by emulating the historical elite's taste for karamono, simultaneously provided the main impetus for department stores’ sales of Asian art and artifacts. These two desires were thus less contradictory than complicit. The imperial state sought to acquire cultural power, which was required to justify Japan’s colonization of Asia, by the aesthetic and intellectual consumption of other Asian art and culture. The new middle class was a key agent in this consumption, and its households’ interiors became a major venue to display the cultural power of imperial Japan. On the other hand, the new middle class tried to accumulate cultural capital, which was necessary to secure its social status, by participating in the collecting and display of karamono. Imperial Japan's political and economic predominance over the rest of Asia offered new middle-class households the means to access this elite cultural practice and enabled them to acquire their desired position within the domestic social and cultural hierarchies. In 1920s and 1930s Japan, the construction of the imperial state and the formation of the new middle class were interwoven through tōyō shumi.

Tōyō shumi was neither a simple copy of Western Orientalism nor a seamless continuation of karamono suki, but rather a hybrid of the two. Tōyō shumi could not operate the same way as did the Orientalism based on the dichotomy between the West as “Self” and the Orient as “Other,” since within the framework of tōyō shumi there existed the West as “the Other” of Japan as well as Japan as “Self” and the rest of Asia as “Other.” In addition, the social meaning of Asian art and artifacts, which had been historically called karamono, remained elite objects rather than exotica in Japanese people's imagination. On the other hand, the practice of collecting and appreciating karamono was refracted by the new regional order in Asia that was reconfigured by Japan's imperial dominance. Karamono shifted from objects of admiration to objects of protection, which should be under Japan's guardianship. The new middle class's taste for Asian art and artifacts derived more directly from an esteem for the historical Japanese elite's aesthetic discrimination that appreciated karamono than from veneration for the cultural sophistication of kara that produced karamono.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2015S1A5B5A01015340).