Introduction

The first communities in the High Arctic of North America are understood to have been established in the Early Paleo-Inuit period (c. 4500–2700 cal BP). At that time, many of the ecological relationships that define the Arctic today—covering species distributions, seasonal cycles and trophic dynamics—were still at an early stage of formation following glacial retreat. The Early Paleo-Inuit communities who thrived in these conditions remain poorly understood as preservation biases obscure the full complexity of their lifeways (see Friesen Reference Friesen2015 for discussion of Paleo-Inuit terminology in Arctic archaeology). Organic materials, such as watercraft components, clothing and zooarchaeological remains, are largely under-represented in the record of this period across the Arctic. As a result, archaeologists primarily interpret Early Paleo-Inuit culture through variation in lithic toolkits, dwelling structures, and the spatial distributions of sites, but these accounts offer only a partial view of technology and environmental legacies (Friesen Reference Friesen, Friesen and Mason2016; Darwent & LeMoine Reference Darwent, LeMoine, Keighley, Olsen, Jordan and Desjardins2021; Jensen & Gotfredsen Reference Jensen and Gotfredsen2022; Grønnow Reference Grønnow, Howkins and Roberts2023).

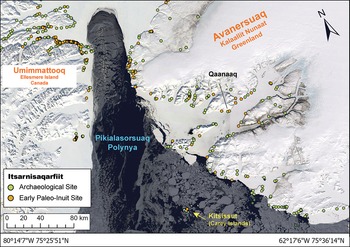

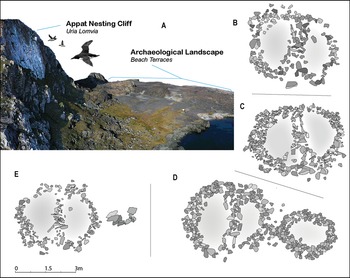

In this article, we offer new insights on Early Paleo-Inuit watercraft, a key technology through which they accessed and influenced the world around them. Observations are based on dense concentrations of features identified during an archaeological survey at Kitsissut, a remote group of islands at the heart of a rich but precarious marine environment called Pikialasorsuaq polynya (Figure 1). Kitsissut can be accessed only by crossing a difficult stretch of water that remains open (i.e. not ice-bound) year-round, thus the presence of Early Paleo-Inuit features permits inference on certain parameters of watercraft design and navigational ability. Beyond a greater understanding of technology, this discovery demonstrates that Early Paleo-Inuit had species relationships that bridged terrestrial and marine systems. We argue that this evidence reflects a community deeply committed to maritime lifeways, where watercraft had a central role in subsistence, social organisation and ecological agency. This expanded view is significant in the context of a changing circumpolar world and opens new questions about the influence of Early Paleo-Inuit communities in the deep ecological structure of High Arctic environments.

Figure 1. Pikialasorsuaq polynya, the Inughuit home territory, showing archaeological sites that include identified Early Paleo-Inuit features. The MODIS satellite imagery is from March 2017 and depicts the cold-season icescapes and open-water expanse (image source: NASA; figure by authors).

The early polynya as a human–environment system

Polynyas are areas of Arctic ocean that remain open—free of land-fast ice—for extended periods, even in the coldest months of winter. Pikialasorsuaq is the largest polynya in the High Arctic, and it acts as a corridor of animal movement, linking seasonal migrations across the Arctic. Pikialasorsuaq is sustained by the annual formation of an ice bridge across Smith Sound, combined with ocean currents, strong winds and heat flux from the deep ocean (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Howell and Brady2023). This stability of open water allows for high primary productivity/phytoplankton blooms, which in turn attracts large concentrations of fish, marine mammals and seabirds. Seabirds cycle nutrients to surrounding landscapes, enhancing vegetation and soil development, creating a form of polynya-dependent terrestrial oasis in an otherwise polar desert. The complex icescapes that form each year around the polynya’s margins remain important hunting grounds for the contemporary Inughuit community, who use them to access sea mammals through the cold seasons (Gearheard et al. Reference Gearheard2013; Hastrup Reference Hastrup2018; Jeppesen et al. Reference Jeppesen, Appelt, Hastrup, Grønnow, Mosbech, Smol and Davidson2018).

Critically, Pikialasorsuaq may not have a pre-Indigenous history. Recent palaeoecological and marine sediment studies indicate that the conditions of the present polynya environment coalesced around 4500 cal BP (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro2021; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Andreasen, Oksman, Andersen, Pearce, Seidenkrantz and Ribeiro2022), suggesting that its formative period coincides with the first known occupation by Early Paleo-Inuit communities. These communities made subsistence choices even as the polynya stabilised, along with the species distributions and ecological relationships that define it today. Seabirds, crucial to the surrounding terrestrial system, were still establishing nesting grounds, while marine mammals adjusted migration routes to seasonal ice edge conditions (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson2018; Mosbech et al. Reference Mosbech2018; Schreiber et al. Reference Schreiber2025).

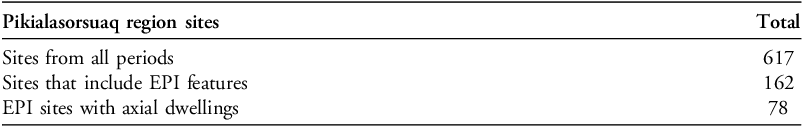

Landscapes on both sides of the polynya contain a dense archaeological record of repeated Indigenous settlement, spanning from that earliest formation of the polynya to the present (Figure 1) (Schledermann Reference Schledermann1990; Darwent et al. Reference Darwent, Darwent, LeMoine and Lange2007; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2010; Hastrup et al. Reference Hastrup, Andersen, Grønnow and Heide-Jørgensen2018; Sørensen & Diklev Reference Sørensen and Diklev2022). Early Paleo-Inuit features are present at about 26 per cent of known archaeological sites (Table 1) and Arctic archaeologists typically distinguish three Early Paleo-Inuit groups (Independence I, Saqqaq and Pre-Dorset). These are differentiated based on variation in lithic tools and house form, and all are represented around Pikialasorsuaq, in some cases at the same site (Schledermann Reference Schledermann1990; Sørensen & Diklev Reference Sørensen and Diklev2022). As a result, the region is interpreted as an area of overlap, or a gateway through which these groups passed to reach Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland).

Table 1. Archaeological sites in the Inughuit home territory depicted in Figure 1.

Most Early Paleo-Inuit (EPI) sites also have features from later periods.

The polynya environment clearly made Pikialasorsuaq an important region to Early Paleo-Inuit communities. Yet within Arctic archaeology, this period has long been interpreted through the lens of an early hypothesis that cast the first Arctic migrants as land-based foragers, moving across the High Arctic by following terrestrial species such as muskox (Steensby Reference Steensby1910). In a recent review, Jensen and Gotfredsen (Reference Jensen and Gotfredsen2022) argue that elements of this perspective endure, despite evidence from sites across the Eastern Arctic that marine mammals were an important feature of Early Paleo-Inuit subsistence (e.g. Milne & Park Reference Milne, Park, Friesen and Mason2016). In West Kalaallit Nunaat, assemblages from the Qajaa and Qeqertasussuk sites contain the only known fragments of Early Paleo-Inuit watercraft, consisting of driftwood fragments of the frame and paddles (Grønnow Reference Grønnow2017). However, these two sites are exceptional in terms of preservation, and the paucity of organic remains or large zooarchaeological assemblages from most sites from this period across the Arctic means that the full extent of maritime lifeways and the ability to intercept animals in open-water conditions remains poorly understood. The assumption therefore persists that Early Paleo-Inuit were relatively terrestrial-focused, at least in comparison with later Inuit communities where watercraft were central to community life and were used for a range of hunting practices to intercept everything from small seals to large baleen whales (Jensen & Gotfredsen Reference Jensen and Gotfredsen2022).

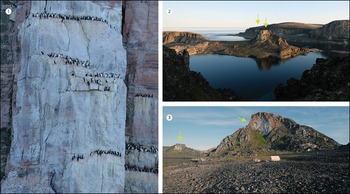

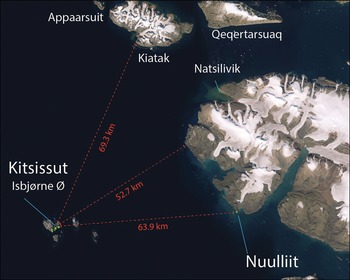

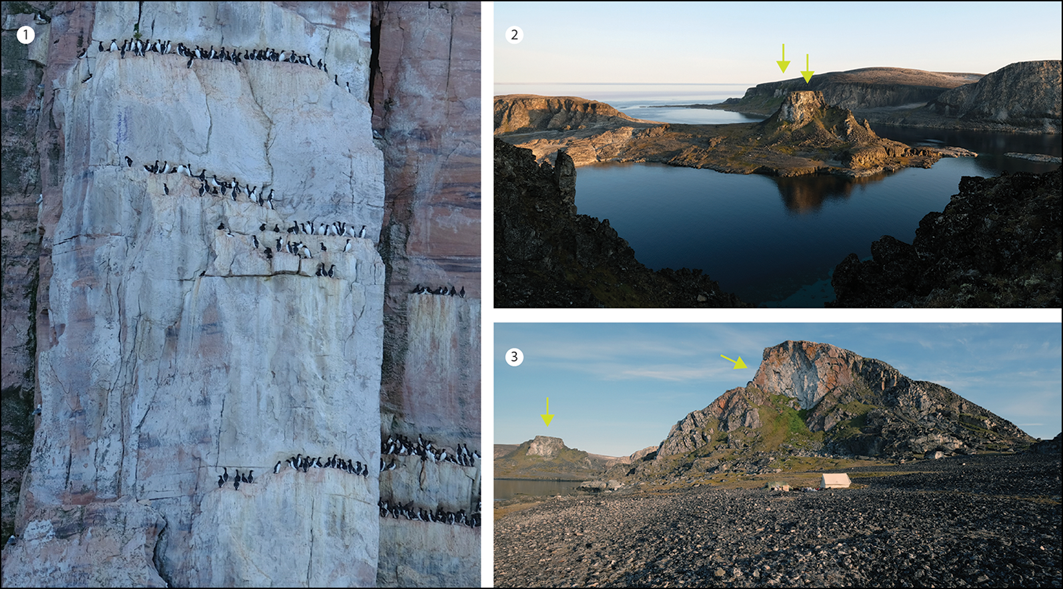

In this context, the significance of the Kitsissut island group, located at the heart of the polynya, comes into focus. Within the ethnographic component of the Inughuit Creativity and Ecological Responsiveness project, directed by the authors, Kitsissut was specifically identified by community partners as an important place for understanding long-term human–environment relationships. It is also an important place for hunting seabirds and accessing eggs, particularly thick-billed murres (Uria lomvia, or ‘Appat’ in Kalaallisut), which nest by the thousands along the cliffs in the early spring and remain until autumn (Figure 2). For Inughuit today, Kitsissut is a place of memory, risk and ecological significance—deeply embedded in oral traditions. In the project’s ethnographic component, contemporary accounts, including those from individuals who have attempted the journey, emphasise the difficulty of reaching the site, echoing the challenges Early Paleo-Inuit travellers would have faced.

Figure 2. Appat colonies at Kitsissut: 1) nesting cliffs; 2) Mellem Island and Nordvest Island in the background with nesting cliffs indicated; 3) beach ridges at Isbjørne Island with field camp and nesting cliffs in the background (figure by authors).

Kitsissut survey and results

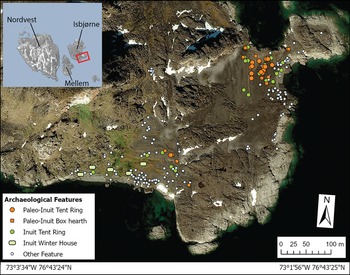

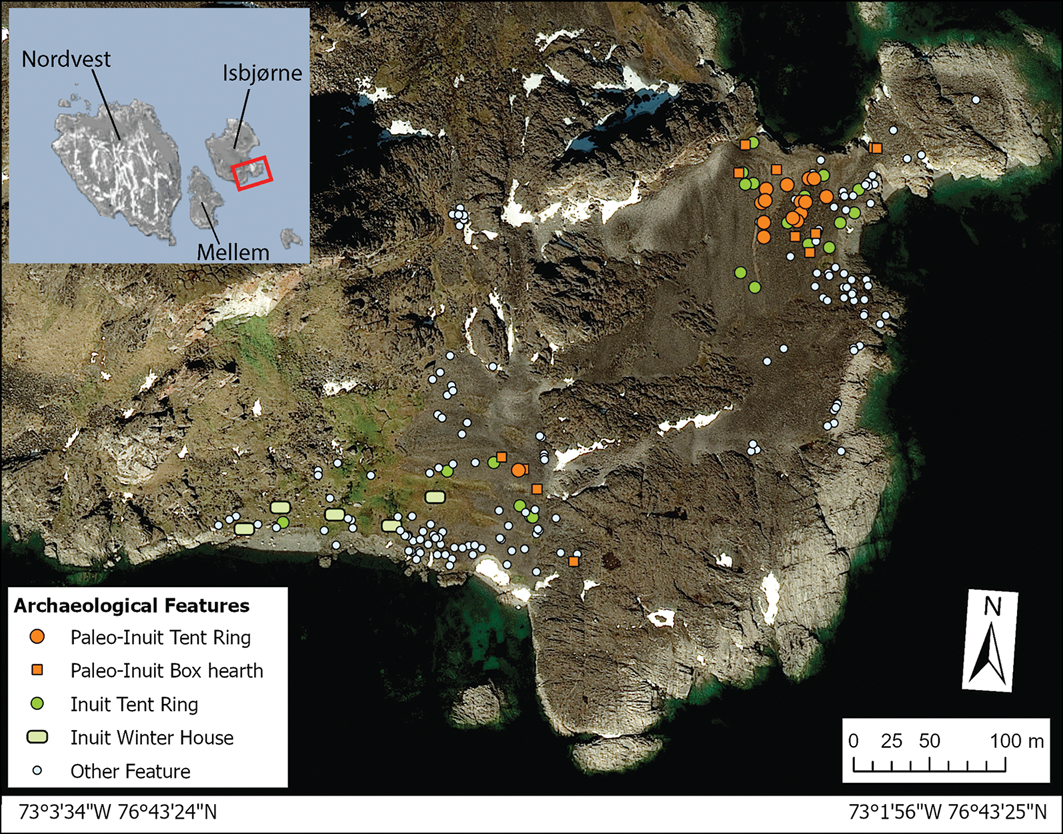

Prior archaeological investigation of Kitsissut has been limited. Lethbridge (Reference Lethbridge1939) documented dwellings associated with the early Inuit (Thule) period (1250 cal AD to present), while Bay (1980) suggested the possible presence of Early Paleo-Inuit features, though no systematic study was undertaken to confirm that. To this end, the research team visited Kitsissut in 2019, and focused on the three central islands: Isbjørne, Mellem and Nordvest Islands (Figure 3). With the assistance of community partners, the field team conducted a systematic archaeological survey along beach terraces, mapping and documenting surface features while also assessing artefact scatters and environmental impacts on site preservation. Results revealed a far more extensive archaeological landscape than previously recognised, shedding new light on how Kitsissut was used across multiple time periods. A total of 297 archaeological features were documented across five localities, with the largest at the south-east tip of Isbjørne Island. Most of these features were associated with Inuit period occupations, aligning with prior observations by Lethbridge (Reference Lethbridge1939). However, some dwelling features associated with the Early Paleo-Inuit period were also identified.

Figure 3. Kitsissut refers to the group of islands and skerries, many of which do not have individual names in Kalallisut. The archaeological features on Isbjørne Island were identified by the authors during a 2019 survey of Kitsissut and include features from the Early Paleo-Inuit and later periods (image source: Maxar; figure by authors).

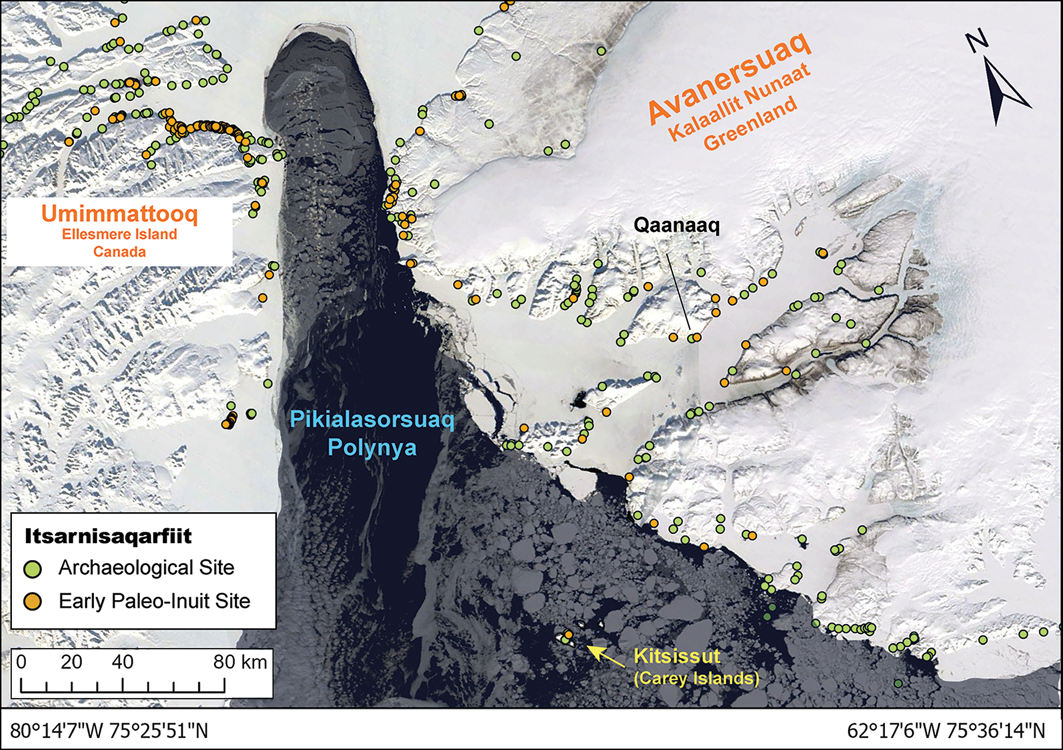

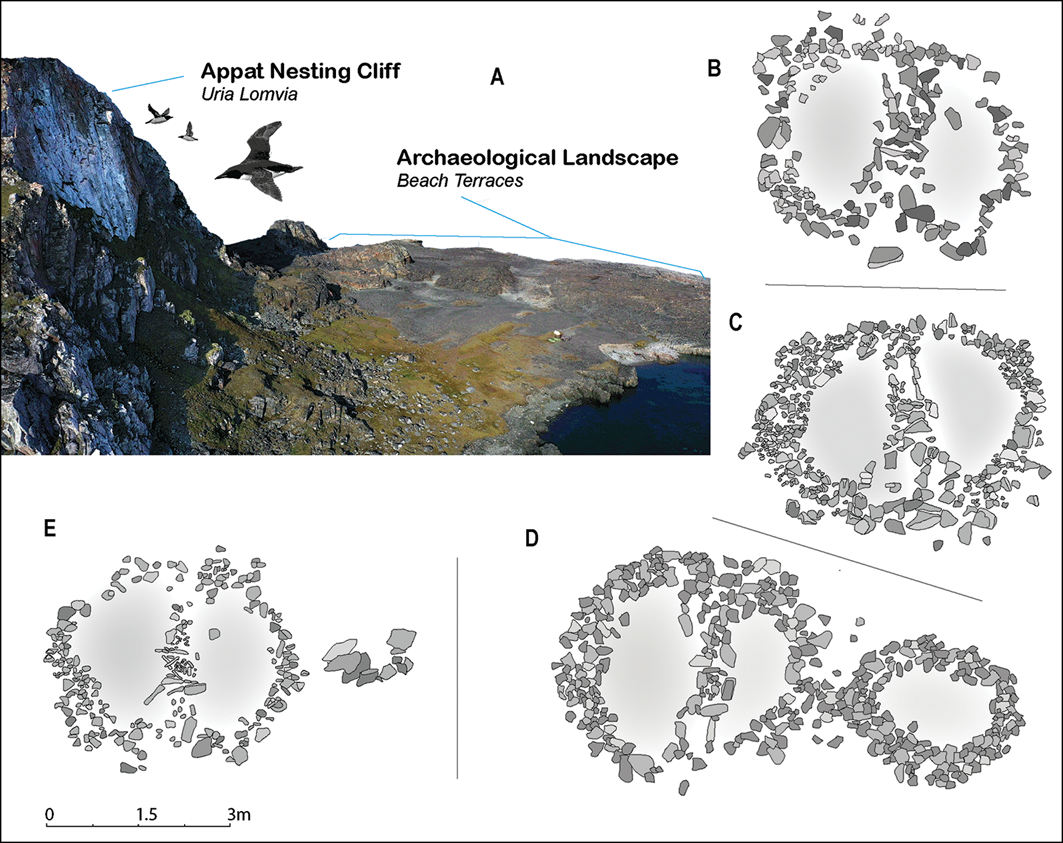

These Early Paleo-Inuit features are concentrated at two closely linked beach terrace sites on Isbjørne Island, situated below a large Appat nesting cliff (Figure 3). The largest cluster includes 15 dwelling structures, each consisting of a bilobate tent ring with axial structures (Figures 4 & 5). This architectural form comprises a bisecting stone feature, which sometimes has a hearth at the centre, and is recognised across the Arctic as diagnostic of the Early Paleo-Inuit period. Similar axial structures are identified at about 48 per cent of Early Paleo-Inuit sites documented from the Pikialasorsuaq region (Table 1). Archaeologists typically associate this with Independence I or Saqqaq, though these terms may not demarcate discrete cultural identities within the Pikialasorsuaq region. The function of the axial structures within these dwellings has been subject to various interpretations but is broadly understood as a spatial division associated with hearth placement and interior organisation. In addition, the survey identified seven external box hearths in close association with dwelling features—another pattern frequently observed at Early Paleo-Inuit sites.

Figure 4. Early Paleo-Inuit features on Isbjørne Island; A) location of site beneath the nesting cliff; B & C) sample of bilobate tent rings with axial features, which bisect the dwelling and include central hearths; D & E) Early Paleo-Inuit tent rings included adjacent dwelling structures or box hearths (figure by authors).

Figure 5. Bilobate tent ring with an axial feature at Isbjørne Island (figure by authors).

To establish a chronological framework, an animal bone was recovered from an exposure within one of the bilobate tent rings and sent for radiocarbon dating at the Czech Radiocarbon Laboratory (CRL 19_794). The sample consisted of a right humerus from Uria lomvia and returned an uncalibrated date of 4203±25 BP. Seabird bone is not ideal for dating as the marine reservoir effect leads to an artificial increase in age; to counteract this a regional correction (ΔR) using the Marine20 calibration curve was applied (see online supplementary material (OSM)). Because seabirds feed on marine organisms across vast migratory ranges, their radiocarbon ages can be offset from local baselines, requiring careful consideration. In addition, Arctic and Atlantic ocean currents and glacial meltwater all interact in the polynya, affecting carbon isotope ratios. Rather than selecting a single point estimate for calibration, the weighted mean ΔR for Zone 5 (West Greenland) was applied (as defined by Pearce et al. Reference Pearce2023), which is -49±59 radiocarbon years. Given the wide-ranging foraging behaviour of seabirds and the broad chronological aim of this study, this correction provides an appropriately cautious calibration, resulting in a date of 4400–3938 cal BP.

While this date range requires caution in interpretation, it effectively rules out a Late Dorset affiliation—a period about 3000 years later when a form of axial structure was used—which can be taken to confirm the association of the identified features with the Early Paleo-Inuit period. On its own, however, it does not provide sufficient resolution to situate the Isbjørne features within the broader chronology of the Early Paleo-Inuit period.

Comparative Pikialasorsuaq region sites

The features at Isbjørne Island represent a multicomponent site produced through repeated use during the Early Paleo-Inuit period. These indicate that the presence at Kitsissut was not adventitious—such as the chance landfall of a group blown off course—but part of broader patterns of settlement and mobility. It is helpful to view this in the context of Pikialasorsuaq regional site distributions, compiled from the Nunavut Archaeological Sites Database and Nunniffiit—the archaeological database of Nunatta Katersugaasivia (Greenland National Museum & Archives). Of the 162 archaeological sites from the region that have Early Paleo-Inuit features (Figure 1, Table 1), Isbjørne Island ranks 10th in terms of the total number of Paleo-Inuit dwellings present. Furthermore, 78 of these sites have dwellings with axial structures, and Isbjørne Island, with 15 axial structure dwellings, ranks fifth in terms of the total number present. This places Kitsissut as one of the most significant Early Paleo-Inuit localities in the Pikialasorsuaq region—comparable to Cape Farraday, Old Nuuliit and Qeqertaaraq, or sites in Inglefield Land such as Jens Jarl Fjord and Glacier Bay (Schledermann Reference Schledermann1990; Darwent et al. Reference Darwent, Darwent, LeMoine and Lange2007; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2010).

Discussion

Kitsissut was evidently a significant place of return for Early Paleo-Inuit communities and thus must be understood as a regular component of their relationships with the polynya, rather than an anomaly. This suggests a need to consider what can be inferred about the technology and skill required to voyage to Kitsissut and the insights this provides into Early Paleo-Inuit lifeways and their reach across the polynya’s terrestrial and marine systems.

Technological and social implications

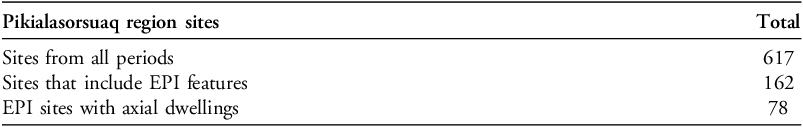

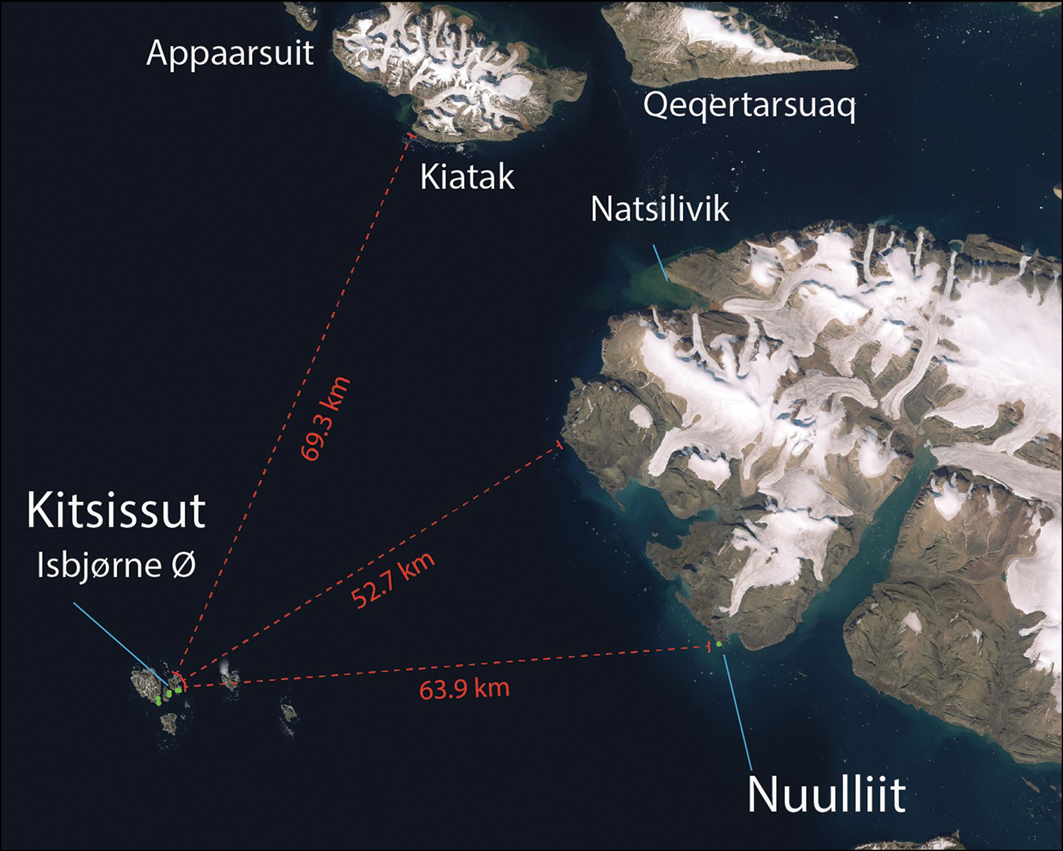

The possibility that Early Paleo-Inuit peoples reached Kitsissut via pedestrian access over land-fast ice can be excluded. The minimum journey to Isbjørne Island is 52.7km (Figure 6), including a stretch where the seafloor drops as much as 900m below sea level. While polynya environments are dynamic, current understandings of Pikialasorsuaq’s development indicate that Kitsissut would have seen year-round open-water conditions since the environment stabilised about 4500 cal BP (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro2021). Crucially, faunal material observed during the surface survey demonstrates that access to Appat colonies, available only during the warm season, was at least one feature of Early Paleo-Inuit interest in Kitsissut.

Figure 6. Distance of crossings to Kitsissut from key locations, including Nuuliit, the closest Early Paleo-Inuit site (image source: Copernicus Sentinel-2; figure by authors).

The character of this journey is remarkable and offers insight into the performance characteristics of Early Paleo-Inuit watercraft and their navigational skill. Even today, with powered boats, travel to Kitsissut is difficult and requires careful timing and preparation for Inughuit hunters. The route is marked by erratic crosswinds, dense fog and powerful mixing currents, where the cold Arctic current flowing southward through Nares Strait collides with warmer waters entering from the Davis Strait. Even when the islands are reached, they consist mostly of skerries with few places to safely land. The minimum time taken for open-water crossing also varies depending on the point of departure, with embarkation from further north possibly preferred given the strong southward winds (Figure 7).

Figure 7. UAV image from Isbjørne Island in clear weather looking towards key locations indicated in Figure 6, with beach ridges and Early Paleo-Inuit features in the foreground (figure by authors).

When compared to other water crossings attested either by Early Paleo-Inuit, related Arctic Small Tool tradition communities or later Inuit groups across the Arctic, this may be the longest journey (52.7km) that can be reasonably inferred from archaeological or ethnographic evidence, from any period. The Bering Strait, by contrast, is just 30km at its narrowest point. From a modern perspective, this voyage would be formidable even for an experienced adventure kayaker, equipped with GPS, current charts and satellite communication/weather reports. Under optimal conditions and with appropriate contingency plans, a modern recreational kayaker might complete such a crossing in 12–15 hours of continuous paddling. As a point of reference, 10 September marks the last day of the year when Kitsissut receives 15 hours of daylight, providing a seasonal window when a continuous crossing with line-of-sight visibility would have been possible under favourable conditions. This emphasises the extraordinary risk faced by Early Paleo-Inuit travellers, who crossed these waters without fallback technologies or rescue plans in a dynamic environment where conditions could change part way through the journey. They would likely have been transporting not only supplies but also family members, including children and elders. The consequences of failure—being blown off course, overpowered by current and dragged into open Baffin Bay—would have been severe.

As noted, the only preserved examples of watercraft-related artefacts from the Early Paleo-Inuit period come from the Saqqaq sites of Qajaa and Qeqertasussuk in the Ilulissat area (more than 1100km south from Kitsissut), where unique conditions allowed preservation of wooden frame fragments and paddles (Grønnow Reference Grønnow2017). Combined with the palaeocarpentry techniques implied by Early Paleo-Inuit lithic toolkits, available evidence suggests they must have used a skin-on-frame design to construct watercraft. This consists of lashed and pegged wooden frames, covered with animal skin and sealed with oil to make it watertight (Walls Reference Walls2010; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Knudsen and Larsen2016). Given the available materials, these vessels were likely similar in concept to the kayaks and umiaqs used by later Inuit communities, though the skin-on-frame approach allows for significant variability and choice in hull shape and performance characteristics (Golden Reference Golden2006). Skin-on-frame craft need regular maintenance, and there are limits in terms of how long the skins remain seaworthy before needing to be resealed; this requires associated technology around processing, sewing and maintenance of skins (most commonly seal).

The difficulty posed by the Kitsissut voyage—erratic conditions, sustained exposure and heavy seas—implies the need for a strong keel and low vessel profile, for a skilled paddler to deal with crosswind and swell. As with later Inuit communities, a mixed fleet of kayak and umiaq-like craft may have been constructed including smaller, closed-deck boats capable of manoeuvring, hunting and rolling in case of capsize, alongside larger, open craft designed for transporting people and materials. This combination seems a likely arrangement for family transit to Kitsissut. Potential use of skin sails is also conceivable given the distance and complexity of return travel—some form of wind assistance may have been employed, as documented in later historic periods for Inuit umiaqs (Petersen Reference Petersen1986).

To help understand the significance of the kind of technological system capable of reaching Kitsissut, it is useful to draw on ethnography, using the kayaks and umiaqs of later Inuit communities as relational analogues (Arima Reference Arima1987; Golden Reference Golden2006; Anichtchenko Reference Anichtchenko2016). Kayaks and umiaqs were used across much of the Inuit world, but their use varied greatly between regions and communities. This variation can be understood as a continuum, where watercraft become increasingly central to subsistence and lifeways. Among some communities, in central Nunavut for example, kayak and/or umiaq use was limited to short seasonal windows, involving comparatively low investment, minimal training and little use of advanced techniques such as rolling. These craft were often flat along the keel for stability in calm conditions and used in lakes, nearshore waters or at the ice edge.

Communities at the other end of this continuum, however, were deeply dependent on year-round kayak hunting and umiaq travel. In these contexts, watercraft design became highly specialised, with performance finely tuned to local weather and sea-ice conditions, and significant social meaning invested in their construction and use (Arima Reference Arima1987; Golden Reference Golden2006; Walls Reference Walls2016). Kayak hunters needed to travel in all conditions and required substantial training that structured childhood. Furthermore, the skills involved in skin work—the processing of sea-mammal skins, sewing and maintaining the watercraft—were also important aspects of daily community life. Apprenticeship in these skills was typically gendered, involved years of development, and was a defining feature of social life for communities on this side of the continuum (Walls Reference Walls2012).

Even in Inuit communities most dependent on watercraft—in Western Kalaallit Nunaat or the Bering Strait regions, where skill and ability were highly emphasised—long open-water crossings were avoided unless necessary, due to the risk. This pattern is well documented in the ethnography of Western Kalaallit Nunaat, for example, where larger-scale community movements were typically undertaken by fleets: kayaks provided support and safety for umiaqs, and travel was carefully planned to remain as close to shore as possible (Petersen Reference Petersen1986).

While the design of Early Paleo-Inuit watercraft cannot be fully surmised based on physical evidence, the early presence at Kitsissut implies that vessels were capable of sustained open-water navigation under difficult conditions. When compared to the range of Inuit watercraft systems documented above, we may infer that a community capable of reaching Kitsissut lies at the extreme end of the continuum with specialised watercraft and navigation skillsets. This reflects a strong commitment to maritime lifeways, where watercraft were central not only to subsistence, but to social organisation, mobility and ecological integration.

Ecological impact on terrestrial and marine systems

The technological capability demonstrated by features at Kitsissut in turn raises broader questions about Early Paleo-Inuit interactions with the formative stage of the polynya environment. A community invested in the construction and maintenance of watercraft/sea-mammal skins, skilled in open-water navigation and capable of making repeated crossings to Kitsissut was not simply adapting to an Arctic environment—they would have been actively embedded within its marine and terrestrial systems. This observation is important because Arctic environmental researchers and conservationists have tended to represent Pikialasorsuaq as an exclusively natural phenomenon rather than a complex human–environment system, where cultural and ecological processes potentially codeveloped over millennia. Indeed, dominant narratives on the vulnerability of Pikialasorsuaq call for external intervention and regulation, downplaying long-standing relationships between Arctic peoples and their environments (Eegeesiak et al. Reference Eegeesiak, Aariak and Kleist2017; Kleist & Walls Reference Kleist, Walls, Cantin-Savoie, Schuurman and Compton2019; Kleist et al. Reference Kleist, Walls, Sadorana, Simigaq and Peary2022; Olsvig Reference Olsvig2022; Buschman & Sudlovenick Reference Buschman and Sudlovenick2023; Hastrup Reference Hastrup2023). Such assumptions can be reconsidered to explore the implications of this evidence for realigning the human and environmental histories of the polynya.

Among the species interactions present at Kitsissut, seabirds are significant—both as a key subsistence resource and as ecological engineers shaping the broader polynya landscape (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson2018). Appat nesting colonies evidently drew Paleo-Inuit communities to Kitsissut, based on the location of dwelling structures at the base of the nesting cliffs along with the presence of bone within those dwellings. Seabirds play a crucial role in structuring the High Arctic’s terrestrial and marine interface, a point that has been increasingly emphasised in recent palaeoenvironmental research (Jeppesen et al. Reference Jeppesen, Appelt, Hastrup, Grønnow, Mosbech, Smol and Davidson2018; Mosbech et al. Reference Mosbech2018). Seabirds cycle marine-derived nutrients into terrestrial ecosystems through their droppings, supporting vegetation succession, soil formation and development of terrestrial food webs. A human community capable of transit to Kitsissut would have also had the capacity to intercept marine mammals, whether along the ice edge or deeper within the open water of the polynya system. Early Paleo-Inuit hunters were likely responding to and shaping long-standing patterns of movement and aggregation among these species as they unfolded, just as Inughuit communities continue to do so today.

At the time of Early Paleo-Inuit occupation, seabird populations were adjusting to the polynya’s stabilising conditions (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson2018). This early Indigenous presence—harvesting eggs, hunting birds and interacting with nesting sites—means that, from the beginning of the polynya’s development, human predation was likely part of seabird population dynamics and must be considered a potential factor in colony growth and distribution through time. In this context, Arctic researchers must reconsider the assumption of a ‘pre-human’ ecological baseline, which is a core premise of many seabird conservation proposals, particularly regarding Appat (Merkel et al. Reference Merkel2016; Sine Reference Sine2022). High Arctic species distributions and nutrient cycles, as a result, may have been shaped by collaborative human and seabird activity from an early stage. Rather than viewing seabird colonies as a passive resource that humans occasionally exploited, conservation biologists and policymakers must consider how Indigenous communities participated in, and possibly even structured, the ecological processes of the polynya through their interactions with these species. By actively participating in both marine and terrestrial ecosystems, Early Paleo-Inuit communities were not merely adapting to the Arctic environment, they were potentially integral to its development. Their interactions with seabirds, for example, suggest a coevolutionary process in which Indigenous practices helped shape ecological patterns that persist today.

Concluding thoughts

Early Paleo-Inuit voyages to Kitsissut reveal an environmental convergence, where choices, technologies and actions were inseparable from the dynamic world of the polynya, challenging archaeologists to rethink how the cultural and environmental accounts of the polynya are aligned. The long-held assumption that Early Paleo-Inuit groups were primarily terrestrial hunters, adapting to an already established High Arctic landscape, overlooks a crucial factor—at the time of their arrival, the terrestrial ecosystem that is dependent on the polynya had not fully developed. The ability to reach Kitsissut, and the technological, social and ecological implications of that ability, brings a new question into focus: were Early Paleo-Inuit not just adapting to ecological conditions but actively shaping them?

Recent research in the environmental history of the polynya has highlighted the role of seabirds as ecosystem ‘engineers’ (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson2018; Mosbech et al. Reference Mosbech2018), and Early Paleo-Inuit communities should also be considered as a creative component of this process. At Kitsissut, Early Paleo-Inuit hunters were not simply extracting resources but were evidently moving nutrients across ecological boundaries. Movement of marine-derived biomass onto land—through hunting, butchering and food processing—may have contributed to several phenomena: localised areas of nutrient enrichment around campsites, through activities such as butchering or skin work, mirroring and enhancing the fertilising effects of seabird guano; archaeological sites themselves becoming ecological anchors, where successive generations of humans, animals and vegetation shaped the landscape over time; and long-term structuring of animal movement and habitat use, with certain species responding to the accumulation of organic material in ways that persist into the present.

Rather than viewing Early Paleo-Inuit occupations in the region as isolated instances of settlement in a geographical crossroads/gateway, Pikialasorsuaq could have been a centre of innovation, where communities and the environment were dynamically co-evolving. Could Pikialasorsuaq have been a place of development for cultural and ecological innovations that later spread into other regions? The diverse lifeways that archaeologists have associated with Independence I, Saqqaq and Pre-Dorset are often assumed to represent discrete communities, yet their technological and behavioural strategies may have first developed in response to the challenges and opportunities presented during the polynya system’s formation. From the vantage of Kitsissut, we propose that, as Early Paleo-Inuit responded to the polynya’s shifting ice margins, species migrations and nutrient flows, they became part of the same emergent system, producing interdependent relationships that may still be in play today. This emphasises that contemporary discussions on Arctic governance must not overlook the deeper history via which environments have emerged through Indigenous responsive actions and ecological creativity.

Acknowledgements

The research team travelled with Inughuit project partners and received support from the Danish Navy’s science research programme aboard the HDMS Lauge Koch, which transported the team including small hunters’ boats to access the Kitsissut islands. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Otto Simigaq, Qalaseq Sadorana and Niels Miunge, who participated in the survey, offering essential expertise in navigation and ecological interpretation, which made this research possible. We also thank Pivinnguaq Mørch and Pia Egede for their field participation as student researchers.

Funding statement

Research took place as part of the Inughuit Creativity and Ecological Responsiveness project supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada (IG 435- 2018-0449) and by Naalakkersuisut (Namminersorlutik Oqartussat/The Government of Greenland – Tips og Lottomidlernes Pulje C).

Author Contributions: using CRediT categories

Matthew Walls: CRediT contribution not specified. Mari Kleist: Conceptualization-Equal, Funding acquisition-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Project administration-Equal, Writing - original draft-Supporting. Pauline Knudsen: Conceptualization-Equal, Funding acquisition-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Project administration-Equal, Supervision-Equal, Writing - original draft-Supporting.

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2026.10285 and select the supplementary materials tab.