To give the transition from communism a viable chance at success, the new countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union required a state capable of governing on the ground. In order to explain why Poland, Russia and Ukraine govern the way they do, we need to explore how capable these three post-communist states are, particularly with respect to their ability to implement tax policy to raise revenue. The first step in doing so is to examine established theories in political science for variations in the capacity of states and then to construct a model of state capacity specific to post-communist states, which we can then test with respect to the ability of state administrative structures to raise tax revenue.

Defining State Capacity

State capacity is an elastic term in the literature. Despite its presence everywhere in political science, the term is not defined in a manner that entails it being easily measured and operationalized. Nevertheless, most political science definitions of state capacity include a sense of the state's ability to accomplish a task. Mary Hilderbrand and Merilee Grindle, in their study, define capacity as ‘the ability to perform appropriate tasks effectively, efficiently and sustainably’.Footnote 1 Grindle, in her own work, has identified a capable state as ‘one that exhibits the ability to establish and maintain effective institutional, technical, administrative and political functions’.Footnote 2 For Michael Bratton, ‘Capacity is the ability to implement political decisions.’ Bratton refers to Theda Skocpol's definition of capacity as the means to implement official goals.Footnote 3 Therefore, drawing upon these definitions, I define state capacity simply as the ability to implement state goals or policy.

Political scientists generally have had a sense that state capacity reflects the ability to achieve state goals.Footnote 4 Some have described state capacity as the ability of state leaders to get people to do something. ‘The main issues’, Joel Migdal describes as the purpose of his book, Strong Societies and Weak States, in its introduction, ‘will be state capabilities or their lack: the ability of state leaders to use the agencies of the state to get people in the society to do what they want them to do.’Footnote 5 Such a definition, then, denotes being able to identify what it means ‘to define’ a specific policy agenda, to distinguish who or what defines the state's goals and to discern what are the state's intentions. Moreover, related to these issues is the ability to set the rules in society (often through bureaus and state agencies) and the consistency of those rules.

Operationalizing State Capacity

The implementation of an extractive policy such as the collection of taxes is a good policy area to choose to assess state capacity, as it requires the penetration of society and utilizes a variety of resources and legitimacy on the part of the people in order to be successful.

Successful taxation through administrative structures has been viewed as an essential hallmark of a strong state. For Charles Tilly, in reflecting on how states were formed in the development of Europe, the essential ingredients for strong states are institutions (although he doesn't term them as such) that control the population. ‘The singling out of the organization of armed forces, taxation, policing, the control of food supply, and the formation of technical personnel stresses activities which were difficult, costly, and often unwanted by large parts of the population’, he writes. ‘All were essential to the creation of strong states; all were therefore likely to tell us something important about the conditions under which strong or weak, centralized or decentralized, stable or unstable, states come into being.’Footnote 6

Similarly, Skocpol has viewed states as ‘actual organizations controlling (or attempting to control) territories and people’, which is done largely through the extraction of resources and the building of administrative and coercive organizations.Footnote 7 For Skocpol, the process associated with rebuilding of state organizations ‘is the place to look for the political contradictions that help launch social revolutions’.Footnote 8 While Skocpol's analysis is based on discerning the origins of social revolutions, the processes by which state structures are rebuilt and taxes are collected in the aftermath of a revolution, such as that following the overthrow, or departure, of communism in 1989 in Poland and in 1991 in Russia and Ukraine, are critically important for the construction and maintenance of social order in the post-revolutionary society.

States cannot govern effectively if they cannot collect revenue. The enormous processes of democratic and economic consolidation require states to do precisely that. Examining this policy area thus provides a clearer picture of the foremost fundamental and prior task for states.

In addition, given Eastern Europe's and the former Soviet Union's inheritance of state socialist-designed institutions, focusing on state capacity through the collection of taxes presents a unique opportunity to evaluate how country-specific variables work in altering analogous institutional designs and similar post-communist goals. Why, given the fact that the centrally planned economies in Eastern Europe imitated the tax system of the Soviet Union, did Poland's inheritance of a poorly functioning tax administration not prevent it from being able to raise adequate revenues in the 1990s? By holding some aspects of past institutional design and current state intentions constant, this book can test for how differing political, economic, geographical and cultural variables have affected state capacity across these post-socialist states.

Explaining the Variance in Governance and State Capacity of Post-communist States

As the differing degrees of state capacity to collect taxes in Poland, Russia and Ukraine are established in this study, the causal forces behind this variation are explored. Specifically, three basic theories on state capacity are reviewed to explain patterns of post-socialist state capacity: One school within political science, led by Samuel P. Huntington, views state capacity as a function of political institutions such as parties (including the different party systems as they relate to regime type).Footnote 9 A second, exemplified by the work of Migdal, sees state capacity as a function of state–society relations.Footnote 10 Finally, a third school (Chalmers Johnson, Peter Evans and Max Weber) views state capacity as a function of the structure of the state itself.Footnote 11 By examining the variables behind these theories, I evaluate the relative causal weight of three competing explanations.

Theory #1: State Capacity as a Function of Political Institutions

Bureaucratic performance may be a function of broader levels of institutionalization within the polity. In 1968, Huntington wrote in Political Order and Changing Societies that only where the level of political institutionalization outstrips the level of political participation could there emerge stable politics working in the public interest.Footnote 12 Specifically, this theory hypothesizes that a focus on political parties – how well they are developed in relation to the state – would account for variance in state capacity.

The most important question for Huntington in his 1968 work is how states can gain the capacity to govern effectively. Huntington begins by observing that ‘[t]he most important political distinction among countries concerns not their form of government but their degree of government’.Footnote 13 To form capable, effective and legitimate governments, states need not hold elections, per se, but must succeed in creating organizations. What is good for the public is ‘whatever strengthens governmental institutions…A government with a low level of institutionalization is not just a weak government; it is also a bad government. The function of government is to govern.’Footnote 14 To develop into modern polities, authority must be rationalized through specified state structures, the development of which requires increased participation by social groups throughout society.

Hence, to involve society in the development of government structures, political parties are the vehicles for the public to keep tabs on state institutions so that they can govern effectively. Political parties, states Huntington, ‘broaden participation in the traditional institutions, thus adapting those institutions to the requirements of the modern polity. They help make the traditional institutions legitimate in terms of popular sovereignty…’Footnote 15 Furthermore, Huntington also argues that corruption – a sign that government agencies are not working as they should – ‘is most prevalent in states which lack effective political parties…’Footnote 16 Thus, Huntington argues that those political leaders and ‘promoters of modernization’ who ‘reject and denigrate political parties’ in order to modernize their society actually will fail to make their societies politically stable.Footnote 17

For Atul Kohli, the absence of effective parties often yields to state centralization accompanied by state powerlessness. ‘Without parties or other political institutions’, Kohli has written with respect to the processes by which India's leaders govern, ‘the links between leaders and their supporters remain weak…[I]t becomes very difficult to translate election mandates into specific policies…Policy failure in turn paves the way for other populist challengers, thus perpetuating the cycle of centralization and powerlessness.’Footnote 18 Similarly, in Democracy and Discontent, Kohli associates the erosion of established authority in certain provinces in India as owing to the lack of a cohesive party structure. Kohli argues for the strengthening of party organizations and for bringing the state's capacities into line with the state's commitments.Footnote 19

The issues raised in Kohli's work on India are quite similar to those in Political Order and Changing Societies insofar as ‘the problem of centralization and powerlessness is an integral aspect of the imbalance between institutional development and mobilized demands’.Footnote 20 Yet, whereas the focus for Huntington is on socioeconomic change, which causes societal mobilization that needs to be structured and organized, Kohli views the spread of democratic politics as encouraging greater political activism in society, which must be channelled through parties.

Hence, regardless of whether the 1989 and 1991 revolutions were about economic modernization or democratization, the new post-communist states, according to this theory, must have developed political parties in order to capture the polities’ interest in and oversight of state institutional activity. How parties are structured in relation to state structures, how they oversee such administrative institutions, whether they simply set overall agency goals or provide direction on more precise bureaucratic functions and how they incorporate society and direct public opinion to provide for oversight are deemed to be critical in accounting for variations in state performance.

Political Parties and Party Systems in Post-communist Poland, Russia and Ukraine

Poland. In Post-communist Party Systems, Herbert Kitschelt, Zdenka Mansfeldova, Radosław Markowski and Gábor Tóka assess how political party systems – born out of the legacy of the communist regime type and mediated through current institutions, rules and political alignment – affect pathways towards the consolidation of Central and East European democracies. In particular, the alignment of partisan divide impacts democratic governance. In the post-communist situation, the nature of a regime divide is the greatest obstacle to effective governance. ‘The deeper the regime divide’, the authors state, ‘the more likely even small policy differences among parties undermine their capacity to collaborate in legislative and executive coalitions.’Footnote 21 The regime types of bureaucratic authoritarianism and national-accommodative communism have led to democracies that have less sharp regime divides than those party systems emerging from patrimonial communist societies.Footnote 22

Kitschelt and his co-authors deem Hungary and Poland to have developed consensual democracy with competition around key economic issues, while the Czech Republic has produced a competitive democracy with significant divisions over economic issues coupled with incentives for collaboration.Footnote 23 The development of Poland's post-communist political party system traces its origins to the negotiated transition in the late 1980s during which the communist regime was rather tolerant in allowing opposition activity and the negotiated transfer of power in 1989. ‘In terms of post-communist party system, Poland shows a rather sharp programmatic crystallization around both economic and political-cultural issues resulting in crosscutting divisions, both of which have some consequence for party competition’, Kitschelt et al. remark with respect to the overall competitive nature of the Polish party system. ‘In Poland, politicians’ and voters’ formal left–right conceptions of their own and the competing parties’ positions are informed by both economic and socio-cultural issues.’Footnote 24

Poland's first free post-communist parliamentary elections in 1991, which followed the first presidential elections in 1990, brought forth a mushrooming of parties, with more than 100 across the spectrum taking part. The number of parties participating in national elections thereafter decreased dramatically. Since those first elections, seven parliamentary elections and five presidential elections – all free, fair, highly competitive and accompanied by a smooth transfer of power – have taken place. Not only has the centre-right – led by those associated with the anti-communist Solidarity movement of the 1980s – and the centre-left – led by post-communists who have become Social Democrats – each controlled the parliament and the presidency, but there has been significant alternation between the two sides of the political spectrum. No governing party since the start of the transition had won re-election to parliament until Civic Platform (PO) was re-elected in 2011.

Moreover, President Aleksander Kwaśniewski, a founder of the post-communist Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) who was elected in 1995 and re-elected in 2000, was succeeded by centre-right Law and Justice (PiS) candidate Lech Kaczynski, who was elected president in October 2005 (and later died in the Smolensk plane crash of April 2010), after a much contested race with PO candidate Donald Tusk, also of the centre-right. In May 2015, PO candidate Bronisław Komorowski, who had been president since his election in 2010, was defeated by PiS candidate Andrzej Duda. Meanwhile, after the October 2015 parliamentary elections, the nationalist-conservative PiS party returned to head the government for the first time since 2005–2007, having defeated the centre-right PO party, which had been ruling since 2007.

Hence, Poland's political party system is highly competitive between the two sides of the political spectrum, albeit especially so between the centre-right PO and the nationalist right PiS in recent years. The question, with respect to this first theory on state capacity, is whether a competitive party system is a primary reason for Poland's relatively greater post-communist state capacity and relatively good tax compliance.

Russia. Meanwhile, in states that succeed patrimonial communist societies such as those of the former Soviet Union, Kitschelt and his co-authors write that liberal-democratic parties tend to lack the skills, networks and resources to replace rent-seeking elites, while other parties in the system, often communist successor parties, ‘exploit their control of the policy process to (re)build clientelist networks and to funnel public assets into the hands of rent-seeking groups affiliated with the party’.Footnote 25 Deep regime divides, associated most with states that succeeded patrimonial communist regimes, further complicate effective reform and institutional oversight as the party system becomes oriented to negotiating the redistribution of assets to rent-seeking groups.

When applied to Russia, this analysis of a deep regime divide, formed from a patrimonial communist past, has great saliency in explaining the first decade of the transition. Parties were, indeed, the political key to mediating poor economic reform in Russia in the 1990s. Yet, in Russia, it is not just a bad party system at work; it is also the lack of party politics that has yielded bad reforms, or rather, a failure to implement government policy. In Russia, the underdevelopment of political parties under both President Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s and President Vladimir Putin since 2000, for different reasons, is also another facet of the underinstitutionalization problem that is viewed as having led to poor governance.

At the beginning of the 1990s, there was great hope that the transition from one-party rule would give rise to a fully competitive political party system. ‘Given Russia's thousand-year history of autocratic rule, the emergence of democracy must be recognized as a revolutionary achievement of the last decade’, wrote Michael McFaul in 2002. ‘Even so, Russia is not a liberal democracy. The Russian political system lacks many of the supporting institutions that make democracy robust. Russia's party system, civil society, and the rule of law are weak and underdeveloped.’Footnote 26 Moreover, in the Yeltsin era, the lack of a structured political party system at the national level led to a failure of Moscow politicians to link provincial politics with the national political agenda, which enabled regional elites to pursue interests in direct opposition to the centre's will.Footnote 27

With respect to filling the seat in the highest office in Russia, Yeltsin's re-election, as well as his transfer of power to Putin, was conducted by processes that were not entirely transparent or competitive. In the 1996 re-election, the media, largely controlled by the oligarchs, gave heavily biased coverage in favour of the president, who began the race with single-digit popularity ratings, enabling him to pull ahead and beat out the Communist Party's candidate, Gennadiy Zyuganov. Near the end of his second (and constitutionally mandated final) term, Yeltsin handed power over to Putin in a manner that resembled the passing of a baton to a protégé. Putin had been appointed prime minister in 1999 by Yeltsin, who himself resigned dramatically on the last day of 1999, paving the way for Putin, the new acting president, to win the election in March 2000 handily.

Since 2000, power gradually has become much more concentrated in the president, and the Duma, Russia's lower house of parliament, largely has been perceived as voting exactly as the Kremlin wants on key decisions, rendering parties less important than they were even in the 1990s. ‘The contrast between the Yeltsin and Putin presidencies is nowhere more visible than in president-parliament relations’, Thomas Remington wrote in 2003, indicating that even early on in Putin's tenure party politics began to fall in line with the Kremlin. ‘Whereas President Yeltsin never commanded a majority of votes in the Duma, Putin's legislative record is filled with accomplishments. Even on the most controversial issues – land reform, political parties, ratification of START – the president and government have won majorities. By comparison, Yeltsin faced a hostile Duma that came close to passing a motion of impeachment in 1999.’Footnote 28

Meanwhile, members of the upper house of parliament, the Federation Council, are no longer elected but appointed. Similarly, regional governors were appointed by legislative bodies of the Russian Federation subjects by recommendation of the president from 2005 to 2012. Further, while Russian politics does have some aspects of pluralism and competition, as M. Steven Fish as written, ‘falsification, coercion, and the arbitrary disqualification of candidates are frequent and pervasive – not merely occasional and deviant – features of elections in post-Soviet Russia’.Footnote 29 All of this has led to the virtual elimination of effective and popular opposition political parties. Hence, as candidates for president, both Yeltsin and Putin did not need a party to be elected – or re-elected. And a unified, pro-democratic reform party never truly developed in Russia.

That said, while in office, Putin has been promoting the elevation of the United Russia party, and, in so doing, has connected himself to a political party much more than his predecessor. United Russia emerged first in 1999, according to Henry Hale, as ‘a political party structure [that] could help take away votes from other parties, but also provide a significant base of support for the Kremlin in the Duma, and most importantly, could channel support from governors and corporations that might have otherwise supported an opposition party’.Footnote 30 Hence, United Russia has developed into the state's party of all sorts, enabling Russia to be governed nearly like a de facto one-party country and, most recently, in the September 2016 ballot, saw its majority control of the legislative branch grow from 238 to 343 of the Duma's 450 seats. As Brian Whitmore commented on that election, ‘The Kremlin has apparently given up on even pretending to have a multiparty system.’Footnote 31

In 2005, due in part to the lack of competitive party politics and in part to the lack of media independent from Kremlin loyalists, Russia was moved from being ‘partially free’ to ‘unfree’, according to the Freedom House classification. In January 2006, parliament passed a law, initiated by the president, that places NGOs under tighter scrutiny by the state. Hence, as Andrew Kuchins related in testimony before the US Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 2006, ‘President Putin has consistently and systematically eliminated competition among independent contending political forces and centralized, at least on paper, more and more political authority in the office of the Presidential administration. If Mr Putin does believe in democratic governance as he contends, he has an odd way of expressing it.’Footnote 32

In essence, the significant absence of an effective political party system and effective political parties might account for Russia's less successful levels of governance since the fall of communism.

Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, as both emerged from the same country, Ukraine, like Russia, has a history of patrimonial communist politics and a post-communist underdevelopment of political parties. While the political process has been competitive in what is largely a presidential–parliamentary system, with parties generally having to form coalitions in order to govern once elected to the parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, parties by and large (with the notable exceptions of the socialists and the communists) have eschewed ideology based on economic or social–political concerns, providing for intriguing coalition governments. At the same time, party membership among the public is quite low. As Paul D'Anieri has argued, ‘Ukrainian parties…are elite-based rather than mass-based.’Footnote 33 As such, they were not viewed early on as a necessary vehicle to political power. In Ukraine's second presidential elections in 1994, only one candidate for president was a member of a political party.

Political parties, like all things related to politics, often are viewed by the public and experts alike as being vehicles for protecting and enriching personal business, especially oligarchic, wealth. Elites have used less-than-transparent political parties and other government connections to capture the state and derive economic rents. ‘However, these “opaque” and oligarchic networks were not unified, and relied on various ad hoc alliances; and their influence on the state did not shut out other interests altogether’, writes Verena Fritz on the 1990s. ‘Political parties – as a potentially balancing force – remained weak in Ukraine. To some degree, there was a self-interest in building the Ukrainian state among political leaders and the bureaucracy.’Footnote 34 As D'Anieri has remarked, ‘“centrist parties” remained fronts for interest politics rather than real centralist parties seeking broad electoral appeal’.Footnote 35 Further, as Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way have observed, both Presidents Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma failed to be utilize parties to solidify support, as both leaders ‘suffered large-scale defections and lost power to former allies’ during their rule.Footnote 36

Stephen Kotkin was a bit more direct when interviewed in March 2014 in summing up the entire post-communist political scene of corrupt networks, without nuance with respect to different parties or presidents. ‘Ukraine is a wreck’, he stated. ‘Ukraine was destroyed by Ukrainian elites. Every regime in Ukraine since 1991 has ripped off that country. They ripped off everything that wasn't nailed down and then they ripped off everything that was nailed down. Ukraine gives corruption a bad name. The economy has shrunk…[T]he Ukrainian economy today is smaller than it was in 1991, by any measure. The economy in Poland is at least twice as big as it was in 1991. So Ukraine is a basket case because of the Ukrainian political class.’Footnote 37 Hale stated, prior to the EuroMaidan Revolution of 2014, that the country has had ‘little real rule of law’ and can be termed ‘clientelist’ or ‘patrimonial’ because its corrupt politics is so individualist-based.Footnote 38

In the 1990s, parliamentary politics was dominated largely by the communists, who won a surprise victory at the first post-communist parliamentary election in 1994. During Kuchma's presidency (1994–2005), parties began to be seen as vehicles for oligarchic clans, who have much greater influence to this day than their peers in Russia.

Broadly speaking, the parties that have developed over the years in post-communist Ukraine have been either pro-Western and pro-nationalist (such as President Viktor Yushchenko's Our Ukraine bloc of the mid-2000s, Vitaly Klitschko's Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform (UDAR), Fatherland (formerly the Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko) and the Petro Poroshenko Bloc), supported largely by voters in western and central Ukraine, or pro-Russian and EU-sceptical (such as the reconstituted Communist Party of the 1990s and the Party of Regions from the early 2000s up until the 2014 departure of Viktor Yanukovych), drawing upon voters broadly in eastern and southern Ukraine.

There have been two main attempts to break up the patrimonial system – both of which were mass-led protest events that brought into power new pro-Western, pro-nationalist parties. Hale regards the first, the Orange Revolution of 2004, as ‘dividing’ but not ‘eliminating’ the clientelist political machine.Footnote 39 And, in part due to the falling out of the Orange duo of Tymoshenko and Yushchenko, only a year after the Orange Revolution, the Party of Regions came in first in the 2006 parliamentary elections, after which Yanukovych, whose initial election ‘win’ the Orange camp successfully overturned in 2004, became prime minister. Yanukovych himself was elected to the presidency in 2010. Moreover, as parliament subsequently abolished a law requiring parliamentary blocs to vote as a whole when forming a coalition, Yanukovych was able to gain control over a revived patrimonial system by appointing a government without forming a coalition with an opposition party.Footnote 40

The second attempt, the EuroMaidan Revolution, brought the removal of Yanukovych in early 2014. The most recent parliamentary elections, which took place later that year, brought forth the most pro-Western parliament in the Rada's history, seemingly ready to consider new reform legislation to further democracy and also to get Ukraine out of its deep economic mire. Midsummer 2016, several of the EuroMaidan revolutionary leaders – a group of journalists and civil society activists rather than career politicians – launched a new European liberal political party, Democratic Alliance, seeking to unify the political centre and centre-right of the country by focusing on the free market, libertarian choices in private life and fierce anti-corruption endeavours that would cleave the electorate differently from previous cultural and populist approaches.Footnote 41 And, since a new law on parties was adopted, political parties in Ukraine beginning in 2016 are to be funded exclusively through the state budget in an effort to clamp down on corruption and financing, but the process, introduced in July 2016, may not be as beneficial to the reform efforts as originally intended, since the established political parties that made it into government with private funding will be awarded taxpayer money while newcomer competitors, which lack oligarch backing, will not.Footnote 42

The question, then, is whether the degree of institutionalization of the polity through political parties actually matters with respect to the development and maintenance of effective state capacity in Poland, Russia and Ukraine – that is, whether the differences in governance levels in the three states are due to the presence of competitive parties in Poland and the lack of them in Russia and Ukraine. If the competition of the parties in Poland is the critical difference, it must be shown to be due to the focus and direction that such parties place on the bureaucracies and administration.

As a way to test this political party hypothesis in order to explain variation in governance, during my field research stage, I interviewed officials and bureaucrats in the tax administrative structures on what input they receive from parties in helping them to implement their policy priorities or tasks. In addition, I examined what impact parties have on the development of bureaucracies and the civil service and on model preferences in each country.

Theory #2: State Capacity as a Function of State–Society Relations

According to the second theory on state capacity, social explanations point to the relationships between states and societies. Migdal has argued that where states lack significant capacity, it is due to the presence of ‘fragmented social controls’ embedded in society that invade administrative structures. In Strong Societies and Weak States, Migdal argues that ‘in societies with weak states a continuing environment of conflict – the vast, but fragmented social control embedded in the non-state organizations of society – has dictated a particular, pathological set of relationships within the state organization itself, between the top state leadership and its agencies’.Footnote 43

This enables the state, then, to become ‘the grand arena of accommodation’ in the polity. ‘First, local and regional strongmen, politicians, and implementers accommodate one another in a web of political, economic, and social exchanges’, Migdal continues. ‘Second, accommodation also exists on a much grander scale…The strongmen end up with an enhanced bargaining position or with posts in the state itself that influence important decisions about the allocation of resources and the application of policy rules.’Footnote 44 Hence, ‘a society fragmented in social control affects the character of the state, which, in turn, reinforces the fragmentation of the society’.Footnote 45 Indeed, across Eurasia, the rise of new post-communist forces that have not been incorporated into formal institutional frameworks might be responsible for state capture.

Joel Hellman's explanation for stalled economic reform in Eastern Europe as being the result of the rise of narrow, vested interests that benefited from rent-seeking opportunities accompanying the transition to the market also could be useful in explaining the stalled state recreation process.Footnote 46 The existence of social network ties between private sector businesses, state enterprise managers and government bureaucrats might be credited with hampering administrative reform and bureaucratic capacity. Therefore, some structural and legal constraints in the transition to a new economy imposed by the state on society are deemed to be necessary. Hence, where states lack significant state capacity, this theory suggests, it is due to the presence of ‘fragmented social controls’ embedded in society that invade state administrative structures.

A fragmented society also has been attributed to the nature of the political culture that reinforces such unconstructive state–society relations. John Elster, Claus Offe and Ulrich K. Preuss have argued that the conditions that favour consolidation of the transition in Central and Eastern Europe are political culture and historical legacy. The authors conclude ‘that the most significant variable for the success of the transformation is the degree of compatibility of the inherited world views, patterns of behaviour and basic social and political concepts with the functional necessities of a modern, partly industrial, partly already post-industrial society.’Footnote 47 Hence, the nature of the political culture, formed in the past, carries the transition forward in different ways.

In addition, while the political culture of society is seen to shape state–society relations, other cultural aspects, such as the nature of the religious background, also are seen to be important. For example, in Making Democracy Work, Robert Putnam argues that the nature of Catholicism, with the vertical structure of the church, has adverse effects on trusting relations between authority and society. Hence, where religious adherence to Catholicism is less intense, better governance is argued to be possible.Footnote 48 Meanwhile, with respect to Eastern Europe, there is a religious divide corresponding roughly between Catholicism, which is more ambivalent about the perception of power, in Central European states such as Poland, on one hand, and Slavic Orthodoxy, which tends to focus more on obedience, in former Soviet Union states such as Russia, on the other, and a mix of both within Ukraine. Differences, then, between the nature of state–society interaction in the two regions might be related to how the two different churches relate to their peoples.

State–Society Relations in Post-communist Poland, Russia and Ukraine

The post-communist transition began with a large disconnect between state and society. In the aftermath of the 1989 and 1991 revolutions, societies across the region shared a deep disillusionment with their bureaucratic states, which were viewed as dishonest and untrustworthy.Footnote 49 (At its nadir, the Soviet Union may very well have been, in Geoffrey Hosking's words, the ‘Land of Maximum Distrust’.Footnote 50) At a time in which much was required of both state and society to begin the transformation to a market economy and a democracy such inherited distrust of the state on the part of society made the tasks at hand more difficult.

Poland. Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan have described Poland in the 1980s as a very strong case of ‘civil society against the state’ – a dichotomy that emerged from centuries of struggle between the Polish nation and a foreign-imposed state authority, which became ‘a politically useful concept in the opposition period because it allowed a sharp differentiation between “them” (the Moscow-dependent party-state) and “us” (Polish civil society)’.Footnote 51 (Similarly, Grzegorz Ekiert titles his book on the communist-era political crises in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic The State Against Society.Footnote 52) In particular, the Catholic Church has been recognized by many as an institutional home for Polish national identity in opposition to the state throughout Poland's long history of foreign occupation – from the 1795–1918 partitioning of Poland by the Austrians, Prussians and Russians through to the Second World War and the post-war communist state.

After 1989, the establishment of a new state and the withdrawal of Soviet forces (and influence) allowed a complete break from this adversarial state–society relationship. However, the appearance of the new Polish state coincided with the initial shock of a severe economic recession that made society wary of state activity. Yet 1992 saw the emergence of economic growth that enabled society to begin to view the state and this new political venture of democracy much more positively. ‘Economic factors were thus favourable for democracy to take root, all the more so because they had a positive influence on public opinion’, Polish sociologist Lena Kolarska-Bobińska has observed. ‘Over time, social acceptance of democratic procedures also increased independent of economic factors.’Footnote 53

Nevertheless, the Polish public began to withdraw from public life as the transition progressed. Bohdan Szklarski has argued that six years after the beginning of the post-communist transition, Polish political culture and citizen perceptions appeared to carry over a ‘subject-apathetic’ character from the previous system. ‘However, the causes of apathy, powerlessness and low efficacy lie more with the feeling of being lost in the complexity of the new reality and in the disappointment with the post-communist elites than in formal or ideological prohibitions than it used to be previously’, he has written.Footnote 54 For Szklarski, then, the articulation of the general public is constrained by the fact that public policy in the economic arena ‘is a product of relationship between two most powerful actors: the state and the unions’.Footnote 55

Yet Kolarska-Bobińska has discovered that Polish society since 1989 ‘can be dissatisfied with elected elites, but not with the system overall, which allows it to make new choices’.Footnote 56 Hence, the inability of Polish society to articulate in a more fulfilling way to political elites regarding public policy issues has not resulted in a poor state–society relationship with respect to general support for the new system or with respect to public confidence in those more directly responsible for governing. Kolarska-Bobińska has even found that increased perception among the public has not resulted automatically in lower approval ratings for those in government.Footnote 57 In 1999, she observed that while local administration was listed in an opinion as the third most corrupt sector, it was listed as the most trusted level of government, aside from the president. Further, confidence in local government has remained stable and high since 1992. The perceived efficacy of these local state institutions with respect to serving local residents well might mitigate any perceptions of corruption, so that local governments can maintain their legitimacy and can enjoy the confidence of society.Footnote 58

Russia. Throughout the 1990s, state interests in Russia were largely co-opted by societal groups. The nature of the initial economic reforms, especially the large-scale privatization by which a significant amount of property ended up in the hands of those with management or communist party ties, enabled a small minority to maintain privileged relations with the state. Indeed, the 1995 ‘Loans for Shares’ scheme in Russia provides a powerful example of how state interests were so co-opted. That government plan, which called for the auctioning of shares in 29 large enterprises to banks that offered the largest loans, ended up benefiting only the interests behind a small group of Russian banks that oversaw the auctions.Footnote 59 Similarly, the manner in which Russian banks were able to funnel money out of the country just before the August 1998 collapse of the ruble so that bank owners benefited at the expense of small depositors also underscores the danger of government ties with concentrated private interests.Footnote 60 The irony of Russia's situation is that the application of the neo-liberal agenda with the goal of getting the state out of the marketplace in order to avoid the rent-seeking behaviour of the state actually ended up accomplishing the later.

In reaction to the neo-liberal agenda of the 1990s, Putin has initiated a number of initiatives to curb civil society since his election as president in March 2000. Several of the oligarchs who came to great wealth and influence in the Yeltsin era, some of whom even helped his election, were accused of financial fraud and tax evasion and either were placed in jail or went into self-imposed exile abroad. (According to Dmitri Trenin, about twenty-two people owned roughly 40 per cent of the Russian national economy in 2005.Footnote 61) The state also took control of the television networks, including the only independent national station (NTV). And Putin successfully pushed forward a new law, signed in January 2006, that places significant regulations on the activity and legal status of non-profit organizations, especially those that receive foreign funding. The creation of a Civic Chamber, tied to the office of the president, also has largely been viewed by analysts as not being a true forum for expression of citizen views on state activity.Footnote 62 On the economic side, in 2015, approximately 55 per cent of the economy was in state hands – the largest share in 20 years, with 20 million workers directly employed by the government, equal to 28 per cent of the workforce, up from 22 per cent in 1996.Footnote 63

Most critically, the manner in which elections are carried out throughout Putin's system of ‘managed democracy’ has dramatically curtailed citizen input into the governing of the state. ‘As for the electoral system, it's not that bad. It's worse’, Nikolay Petrov argues. ‘The centre can legally exclude any candidate. A healthier Russian democracy will not emerge without decentralization and federalism. For now, the lack of meaningful elections has seriously weakened civil society.’Footnote 64 In fact, Georgy Bovt, editor of the Russian newsmagazine Profil’, has observed that citizens no longer participate in the electoral process at the local level, adding, ‘and soon they'll stop voting in federal elections too. People boast about their lack of interest in politics. They don't read the papers. Television programs dealing with politics and social issues have been pulled because of low ratings.’Footnote 65 Hence, the lack of political choice and true public debate has led to a lack of interest in politics, evidenced most recently by the record low voter turnout of less than 48 per cent in the September 2016 parliamentary elections.Footnote 66

In his own way, Putin appears to have a different connotation of what a ‘civil society’ actually is. ‘[W]hat is more important is a mobilization of the nation before the general threat’, Putin said in his first televised address following the Beslan elementary school hostage drama, four days after it began on 1 September 2004. ‘Events in other countries prove that terrorists meet the most effective rebuff where they confront not only the power of the state but also an organized and united civil society.’Footnote 67 Following the Beslan debacle, Putin did not fire the law enforcement members who were bribed by the terrorists as they passed freely from Chechnya to North Ossetia, but, according to Anders Åslund, opted for sacking the editor-in-chief of the independent newspaper Izvestiya ‘who had committed the crime of accurate reporting’.Footnote 68 In essence, Putin seems to view a constructive ‘civil society’ solely as an entity to be in step with and channelled by the Kremlin.

With respect to political culture, three main arguments have been made in reference to the political culture of Russian society to explain its interactions with the state. First, unquestionably, the greatest applicability of this variable in explaining governance problems has been to the real lack of commitment or desire on the part of the populace to change over to a new economic system in the 1990s. In fact, Russians did not rebel en masse against their Soviet state in 1991 (at least outside of Moscow), but regretted the loss of it, especially in relation to the new one they inherited. Three years after the breakup of the USSR in 1991, 68 per cent of Russians stated in a poll that the dissolution was the wrong decision, while 76 per cent stated that the USSR's demise had affected Russian living standards for the worse.Footnote 69 ‘Russians during the Soviet era’, comments James R. Millar, ‘indicated high levels of satisfaction (two-thirds to three-fourths reported being “very satisfied” or “satisfied”) with their housing, jobs, access to medical care and higher education, and overall standard of living.’Footnote 70 The price liberalization policies initiated in 1992 encountered deep disapproval and scepticism on the part of the population towards the economic transition, which has never really gone away. In contrast, in Poland, the vast majority did not question the collapse of communism.

Second, many analysts have attributed the origins of Russia's state–society unconstructive relations to the fact that Russia is composed, for the most part, of those whose religion is Slavic Orthodoxy rather than Catholicism or Protestantism. Shock therapy architect Jeffrey Sachs has even joined in, recognizing the role that the religious divides among the different forms of Christianity played in the first decade after communism in Eastern Europe.Footnote 71

Linz and Stepan explain that the nature of the three branches of Christianity can impact the type of support given to democratic opposition groups, while carefully recognizing that Orthodox Christianity is not inherently an anti-democratic force. They argue that ‘Roman Catholicism as a transnational, hierarchical organization can potentially provide material and doctrinal support to a local Catholic church to help it resist state opposition’.Footnote 72 As such, the church could be considered as providing support to ‘a more robust and autonomous civil society’. (Interestingly, Putnam's arguments on Catholicism in Making Democracy Work also suggest that the vertical nature of the church leads to a ‘society versus the state phenomenon’.) Similar arguments could be made with regard to Protestantism, with its emphasis on individual conscience and its international networks.

‘Concerning civil society and resistance to the state, Orthodox Christianity is often (not always) organizationally and doctrinally in a relatively weak position because of what Weber called its “caesaropapist” structure, in which the church is a national as opposed to a transnational organization’, Linz and Stepan continue. ‘In caesaropapist churches, the national state normally plays a major role in the national church's finances and appointments. Such a national church is not really a relatively autonomous part of civil society because there is a high degree, in Weber's words, of ‘subordination of priestly to secular power’.’Footnote 73 Hence, according to this argument, whether the Orthodox Church supports civil society depends upon whether or not the state leaders truly are committed to democracy.

Further, how frequently individuals within a society attend religious services might also account for the nature of state–society relations, regardless of the religion. In 1993, only 16 per cent of Poles stated that they never or rarely went to church, whereas the corresponding figures for Belorussians and Ukrainians were 71 and 60 per cent, respectively.Footnote 74 (Figures were not given for Russia, but can be assumed to be similar to those for their post-Soviet Slavic Orthodox neighbours.)

Finally, there is the issue of corruption. ‘The real cause [of which] lies in deeply internalized Soviet cultural practices’, Vladimir Brovkin has stated. ‘Defrauding the state was an accepted practice under the Soviet regime.’Footnote 75 As Thomas Graham, Jr., explained in his September 1999 testimony before the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, ‘corruption has deep roots in the historical conflation of the private and the public in Russia. For most of Russian history, the state was for all practical purposes the property of the Tsar. There was no formal distinction between sovereignty and ownership, between the public sphere and the private sphere. Almost by definition, public positions were exploited for private gain.’Footnote 76 Communist Party rule changed little, other than that nominal ownership was transferred from the tsars to the Communist Party, so that state goods were readily available for private gain once the system began to fall apart.Footnote 77 Even US Vice President Al Gore, in defence of the US role in the reform of Russia, has attributed the prevalence of corruption in Russia to the ‘legacy of communism’.Footnote 78 However, such comments do not explain the dramatic explosion of corruption in the 1990s compared with the decade before – or even the greater growth in corruption that has accelerated under the Putin regime.

The level of corruption also has increased significantly in the Putin era, beyond that of the Gorbachev and Yeltsin eras. The Putin administration's own Interior Ministry's investigation committee has stated that they saw an increase of about 13 per cent from 1999 to 2003 in corruption-related crimes. In 2003 alone, crimes of bribery rose nearly 17 per cent, and they were up again by about 28 per cent in the first half of 2004.Footnote 79 In 2004, Transparency International (TI) stated that every fifth Russian gives bribes to solve problems and that of the $1 trillion in bribes worldwide, Russia accounts for at least $38 billion.Footnote 80 In 2014, Russia ranked 136 out of 175 on TI's Corruption Perceptions Index, equal to Nigeria.Footnote 81

The most recent comprehensive report on corruption from the INDEM Foundation, released in June 2011, found that

the average bribe grew nearly twofold in five years from US$90 in 2005 to US$176 in 2010;

the total volume of petty bribery in Russia grew from US$4.6 billion in 2005 to US$5.8 billion, albeit alongside inflation growth of 7–8%; and

the average amount of a petty bribe (1,817 rubles in 2001; 2,780 rubles in 2005 and 5,285 rubles in 2010) grew faster than inflation, becoming 93 per cent of an average salary in 2010.Footnote 82

Moreover, Russia's own Ministry of Interior relayed in August 2015 that the average bribe in the country nearly doubled, in ruble terms, from around 109,000 rubles (US$3050) in 2014 to 208,000 (US$3400) – startlingly high in any currency.Footnote 83 Hence, regardless of how high the numbers go, the general consensus of independent researchers is that despite Putin's many public statements and, most presumably, sincere wishes on curbing corruption, levels of corruption have grown since he became president.

Ukraine. As mentioned above, Ukraine has had a unique combination of oligarch-based, or rather oligarch-backed, politics with a very active civil society, willing to take to the Kyiv's Maidan (Independence) Square twice in less than a decade, demanding that their country become less corrupt and more Western and stable – in other words, in local parlance, ‘normal’.

Under Kuchma's presidency, control over society was exercised through ‘informal means’, or what D'Anieri has labelled ‘machine politics’ – activities that included the bankrupting of firms owned by opposition elites, the provision of immunity for firms that support the government, and the use of tax laws and fire codes to close opposition media.Footnote 84 Such patronage-based politics was structured more through ‘machine politics’ than ‘party politics’.

Three years after the Orange Revolution, in 2008, Freedom House labelled Ukraine as ‘free’ – the only Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) country so named. In many ways, the ‘free’ label was related to the fact that the media in Ukraine had become freer under Yushchenko. Of course, while less controlled, the media were hardly ‘independent’ in the truest sense, being under the control of various large (oligarchic) business groups.

Both the Orange and EuroMaidan revolutions have been credited with enlarging and making more active Ukraine's civil society due to the prominent role that NGOs and citizens had in both protest-led movements. ‘[The 2014] election demonstrated’, wrote D'Anieri in describing the role of civil society in the first revolution, ‘not only that large numbers of Ukrainians were willing to become politically active, but also that they had considerable organizational capacity. Organizing, training and deploying, first, election monitors, and later, protestors, required considerable logistical capacity…Once organized forces got the protests started, hundreds of thousands of citizens quickly joined in.’Footnote 85

Moreover, while participants from all around the country took part in both revolutions, greater participation has been credited to those from western Ukraine. And, indeed, there is a perception that western Ukrainians have played a large part in developing Ukraine's civil society across the whole country, drawing upon their experience from being part of the Austrian Empire. ‘Imperfect as they were, the Austrian models of parliamentary democracy and communal organization’, writes Serhy Yekelchyk, ‘shaped western Ukrainian social life. [Western Ukraine's] experience of political participation in a multinational empire and its successors also strengthened Ukrainian national identity.’Footnote 86

Currently, the post-EuroMaidan reform agenda, according to Olena Tregub, has been pushed from above by three distinct groups – reformers in the government; a professionalized civil society that has even drafted legislation as part of push for reforms in particular sectors; and foreign donor groups from the West such as the International Monetary Fund, the US Agency for International Development, the World Bank, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. ‘None of them’, she states, ‘necessarily have the same priorities as Ukrainian society as a whole.’Footnote 87 With respect to the current post-EuroMaidan reforms, the activity of the formal civil society, largely consisting of NGOs based in Kyiv that are a product of the now decades of foreign (Western) assistance programs, has been high – evidenced by the formation of a ‘Reanimation Package of Reforms’ coalition of NGOs that pushes for parliamentary bills, leads protests and monitors reforms, and of a National Anti-Corruption Bureau to investigate high-level graft – but has not been matched by a groundswell of criticism and involvement in national affairs by the general public.Footnote 88

What has been lacking – even post-EuroMaidan – has been an enlarged, spirited intellectual and political debate in society over the future of Ukraine – not just regarding its independence, but as to what type of state and what type of society should develop there. Admittedly, most of the conversation recently has been about the war in the East, whether and how the state should be decentralized and the desired return of Crimea. But, as Tymofei Mylovanov has stated, there has been little intellectual debate among prominent civil society members with regard to where Ukraine is going and how the old regime's void should be filled.Footnote 89 Ukraine needs a much more vibrant debate regarding its future direction, what type and flavour of democracy should develop and how the society should interact with the state. Further, while there has been much – and perhaps, surprising – consensus within Ukraine and the Verkhovna Rada regarding the need to push further with reforms and lively discussion as to whether the Yanukovych-era elites should be allowed to work for the state, both within the parliament and in society at large, there has been less of a discussion as to how the state institutions, agencies and bureaucracies should be reformed and made less corrupt.

In essence, most of the state–society literature suggests that governance depends on whether the society can be subordinated to the will of the state or whether society is strong enough to resist or to co-opt the state. The nature of the political culture, the historical legacy and the church in each country can contribute to the degree of independence enjoyed by the society in opposition to the state. If such a relatively zero-sum relationship between state and society does account for post-communist Russia's and Ukraine's less successful levels of governance, the question becomes, then, why were the Polish people with the communist-era state, the Polish People's Republic, to a lesser extent than the Russians, and possibly the Ukrainians, were with their Soviet state while the opposite appears to have been the case since the transitions began. Presumably, the natures of the culture, history and church did not change in these societies after 1989 and 1991. Further, if state–society relations, as defined in such a zero-sum approach, account for the significant difference, it must be shown that Polish civil society is somehow more subordinated to the state than in Russia and Ukraine. And, finally, for such a theory to hold, the increased state control at the expense of society in Russia under Putin should make governance even stronger.

On the other hand, healthy state–society relations might well be necessary for good governance, but not in a manner in which an independent civil society is pitted against the state. As suggested by the levels of trust in the state (if not in politicians) in Polish society, trust in the state by society might be the foundation for a constructive (and non-zero-sum) relationship between state and society. Further, repetitive and concerted healthy interactions between state and society may well have benefits for society too, as Samuel Greene has argued. ‘As iterations [between state and society] continue’, he has written, ‘there should ideally emerge a stable pattern of interactions, in which civic and state actors may reasonably judge the effectiveness of one or another course of action; this may be considered the consolidation of civil society.’Footnote 90

As a way to test whether state capacity is a function of state–society relations, I conducted interviews with central and local government bureaucrats, specifically inquiring about which types of social groups, actors in society, businesses and private entrepreneurs are most useful in helping them implement their policy priorities and tasks. In addition, I organized surveys on tax compliance to examine further the nature of relations between state bureaucrats and citizens on the ground.

Theory #3: State Capacity as a Function of the Structure of the State

The third school of thought on state capacity finds its origins in Johnson's MITI and the Japanese Miracle and Evans’ Embedded Autonomy.Footnote 91 For Evans, it is the state bureaucracies that are both coherent and embedded in society, through strong ties between the state and the private sector that can make good investment decisions that will yield growth such that otherwise atomized elites will invest.

Indeed, the post-communist institutional design of the new state agencies may account for differences in state capacity. A paradox, or fatal flaw, of the glasnost and perestroika programs initiated by the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, concerned the fact that the problems that were inherent in the system became more acute once those institutions attempted to start their own reforms from the top down. The process of correcting problems complicated those that existed, in turn threatening the legitimacy of the regime. When a system is based on being hyperinstitutionalized along vertical links, as the Soviet Union once was, that same system cannot undergo a complete overhaul of planning and management. Institutions cannot focus on their day-to-day tasks and at the same time restructure themselves by introducing new incentives for those at the bottom and reorganizing the command structure at the top. Ultimately, the Soviet system developed an economic fix requiring a clean break for new institutions to be created.

Phil Roeder, Steven Solnick and Valerie Bunce have offered three different accounts of the collapse of the Soviet Union, each of which places the cause in different aspects of the institutional design of the socialist system.Footnote 92 Roeder, in his book Red Sunset, has provided a neo-institutionalist approach to the collapse, stating that its cause lay with problems in the Bolshevik constitution – the fundamental rules of the Soviet system. The constitutional order was laid out in such a manner that policymakers built their power on bureaucratic constituencies, while bureaucrats in turn needed the continuing confidence of their patrons to remain in office. The institutionalization of reciprocal accountability and balanced leadership increased the stability of the polity, but it also had a perverse effect – it limited the polity's ability to innovate in policy and to adapt its institutions to social change. Instead, the Bolshevik constitution brought policy dysfunction and institutional stagnation.

Similarly, Solnick, in Stealing the State, offers a principal–agent model of Soviet-type bureaucracies, showing that agents were required to continue to abide by the agency contract and to manage institutional assets in the principal's interests, rather than in those of the agent. If an agent violated the contract and this went either unnoticed or unpunished (i.e., assets were not taken away from the agent by the principal), then the agent had appropriated the assets. In an analogy to a ‘bank run’, the state's institutions began to fall apart, triggered by the perception that principals could no longer control their resources.

Bunce, in her book Subversive Institutions, also has shown how the socialist institutions, by design, divided and weakened the powerful while homogenizing and strengthening the weak interests in society. In the end, socialism deregulated itself over time – a process that became accelerated when the institutions met the international and domestic events of the 1980s. Hence, differences found in organizational charts of post-communist bureaucracies may account for variation in post-communist state capacities.

With respect to Weber's characteristics of bureaucracies, Michael Mann has stated that ‘Bureaucratic offices are organized within departments, each of which is centralized and embodies a functional division of labour; departments are integrated into a single overall administration, also embodying functional division of labour and centralized hierarchy.’Footnote 93 Mann also has explained autonomous state power as relating to enhanced territorial-centralization, a concept central to state capacity.Footnote 94 In short, for Mann and for Weber, being able to implement certain tasks requires a state structure embodied with a certain amount of autonomy such that fairly consistent rules can be applied without undue and incapacitating interference from outside groups.

Hence, according to this third theory, bureaucratic structures that are designed in a centralized, hierarchical manner to allow an autonomous relationship to the wider society are necessary in order to provide for effective policy outcomes.

The Structure of the State in Post-communist Poland, Russia and Ukraine

The communist political system in East Europe and the Soviet Union essentially blurred the distinction between state administration and the Communist Party bureaucracy. ‘The almost complete subordination of economic and social life to the state’, writes Jacek Kochanowicz, ‘resulted in the growth of a bureaucracy tailored to manage a centrally planned, command economy through an extensive set of administrative agencies.’Footnote 95 Since the collapse of communism, states such as Poland, Russia and Ukraine have had to reconstruct their bureaucracies so that the lines between politics and policy implementation are more distinct. ‘Unlike countries that must rebuild classical administrations that have collapsed or new nations that have to erect government from scratch’, writes Barbara Nunberg, ‘[Central and East European] countries are in the midst of crafting a set of “unfinished” institutions, which combine aspects of both pre-communist and communist legacies with elements borrowed from abroad and with indigenous innovations developed in response to the exigencies of the transition.’Footnote 96

Poland. On the face of it, Poland inherited a bureaucratic history that is comparable to that of the former Soviet Union with respect to entrenched clientelism and strict hierarchical structure. Throughout Poland's complex bureaucratic history, Nunberg writes with respect to Poland's bureaucratic legacy, ‘several characteristics typified the state administration: a rigid and steep bureaucratic hierarchy – that is, many layers of bureaucracy with decisional autonomy only at the top of the command structure; power derived from personal ties and seniority rather than merit; and the prevalence of inflexible rules undermined by clientelism and circumvented by the use of załatwić (loosely equivalent to the American slang word “pull.”)’Footnote 97

Yet there is some question to what extent such ‘inflexible rules’ and entrenched clientelism have continued to exist in Polish bureaucracies since 1989. On the one hand, Freedom House's Nations in Transit 1998 report, for example, stated that corruption is less widespread in Poland than in other post-communist states.Footnote 98 On the other hand, despite Poland's advances in significant economic policy areas in the early 1990s, initial reforms such as public administration training and local government administration changes in 1989 and 1990 were not followed up with comprehensive bureaucratic reforms. State administrations held over from the communist era were required to implement the extensive economic programs required in the transition to the new economy. ‘The source of most corruption’, the Freedom House report does acknowledge, ‘is the discretionary power of bureaucrats to issue licenses, conduct inspections, grant waivers, and award contracts.’Footnote 99 Only in 1996 was Poland's government able to push through a package of significant administrative and constitutional changes including a new Civil Service law.

More recently, as elaborated in Chapter 3, the PiS government threw out several civil service regulations right after its 2015 electoral win, furthering the notion that Polish bureaucracies are spoils for election winners.Footnote 100

Russia. Despite the changes at the top of the system after the Soviet collapse, the basic communist employment and administrative practices were left intact throughout most of the 1990s. ‘While only 10 per cent of the old-style nomenklatura are still in state or government posts’, Freedom House reported in 1998, ‘the system suffers from corruption and an acute shortage of modern managers and civil servants.’Footnote 101

In 1995, the Russian State Duma passed the presidential version of a Law on the State Service, which divides public offices into three categories and bans civil servants from simultaneously holding any other employment, except teaching or research jobs. ‘Benefiting from exposure to civil service models from abroad and discussions with foreign experts, the legislation made a good start in establishing the essential functions and public service ethos of the civil service corps’, writes Nunberg. ‘But, the law is not without problems, and serious consideration of amendment or clarification through subsidiary legislation or regulation may be needed to ensure that robust civil service institutions are created and maintained.’Footnote 102

An additional unique feature of the design of Russia's institutional system is its selection of a federalist structure – a system that does not exist in any of the Central and East European states. In the 1990s, the adoption of a federalist system of government accelerated further the decentralization process that is normally associated with democratization.

Meanwhile, Putin has sought to reverse that decentralization trend and strengthen the capacity of the state with alterations in the system of fiscal federalism; the creation of seven federal districts with viceroys subordinated to the Kremlin to oversee the provinces; a reform of the Federation Council, the upper house of parliament, so that it no longer is composed of regional governors; and the appointment of officials with strong allegiance directly to the president rather than to other government institutions. Following the Beslan terrorist attack in 2004, Putin's proposal to nominate regional governors, subject to the approval of regional legislatures, was successfully passed, so that governors were no longer elected from 2005 to 2012, when direct popular gubernatorial elections resumed. Efforts were also undertaken to ensure that state agencies and bureaucracies fell in line with the strict hierarchical system of management. (And, of course, while prime minister in 1999, Putin began the second Chechen war in an effort to curb any regional secessions.) Hence, due to the ‘power vertical’ function of the Putin system, Russia is governed much more like a unitary state today than it was in the 1990s. And, since Putin's return to the presidency in 2012, Putin has been viewed as strengthening that ‘vertical’ in the executive branch even further rather than prioritizing economic reform.Footnote 103

Ukraine. In many ways, the efforts being undertaken in Ukraine since 2014 are the first major attempts to reform that country's state and administrative structures. Most recently, in December 2015, Ukraine's parliament passed a new law on civil service reform that is most promising, calling for administrative and personnel reforms that are more in line with EU standards in order to root out deeply entrenched corruption.

In 2015, the first full year after the EuroMaidan, the situation with regard to corruption was viewed through Transparency International data as quite severe. Compared with the year before, the average bribe of an official rose from 30,000 to 40,000 Ukrainian hryvnia (albeit falling in US dollar terms, due to the hryvnia's depreciation). In 2015, only 19 per cent of those receiving bribes were in jail, while a tenth of all convicted of bribery were acquitted. Situations also abounded in which the fine for bribes was less than the amount of the bribe itself.Footnote 104

Meanwhile, throughout nearly all of Ukraine's twenty-five-year history up to 2015 as an independent state, the country lacked significant legislation aimed at truly reforming its bureaucracies. As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, the process of administrative reform floundered under Kuchma and Yushchenko. In part, this was because the initial constitutional division of powers, drafted in the early 1990s between nationalists and older communists, was consistently up for reconsideration in Ukraine. Part of Ukraine's uniqueness, of course, lies in its hybrid presidential–parliamentary system, which has placed executive power not entirely in the presidency but in the Cabinet of Ministers as well. And Kuchma's presidency was viewed as veering towards moderate authoritarianism, with Yanukovych's presidency doing so much more. As such, amidst bureaucratic interference in the economy and amidst a truly oligarchic system in which oligarchs checked, balanced and stalemated each other as they intervened in politics, the regional governments also lacked power on their own to undertake any significant administrative reforms.

The extent to which the state is well organized and embodied with human and financial resources may well be an explanation for the state capacity outcomes in post-communist Poland, Russia and Ukraine. For this theory to hold, state structure must be shown to be primarily accountable for governance outcomes. Further, the manner in which the state is structured – in a hierarchical manner, similar to that of the former Soviet Union, or in a more Weberian one – must be shown to be of critical significance.

To test this hypothesis, I conducted interviews with bureaucrats at different levels of the Polish, Russian and Ukrainian states and examined historical and government documents in order to discern differences in the lines of authority and hierarchical patterns between the relevant policy agencies in the three states.

A Model of State Capacity for the Post-communist States

Despite the enormous contributions that each of the three theories on state capacity described above has made to the field of comparative politics, each has limitations in explaining post-socialist state capacity patterns. The first theory, with state capacity being a function of the development of political institutions such as parties, largely ignores dynamics of societal interaction with the state other than political parties. The second theory, with state capacity being a function of state–society relations, does pick up on such interaction missing in the first theory, but largely views state and society as engaged only in a zero-sum relationship. Finally, the third theory, focusing on state capacity as a function of state structure, is far too exclusively focused on the organization of the state itself. Furthermore, none of these theories highlight history and previous state–society interactions extensively. How the state has treated citizens in the past also is critically important in determining current state activity.

I revise these theories and develop a new model for state capacity. I construct a theory of state capacity for the post-communist states that incorporates some aspects of state–society interactions and relies on most of the state structural arguments. More specifically, my model focuses on the extent to which the state is organized and provided with resources in a Weberian sense and on the manner in which society becomes ready to be a compliant, willing partner in state activity. In focusing on society, the second theory on state capacity would predict that if society and social groups were powerful, one would not see effective implementation of state goals. My theory predicts, instead, that when trust is built up between state and society, society will comply. Rather than acting autonomously, I argue that the state can be effective when it penetrates civil society to complete a task by building and by drawing on trust on the part of society in the state itself.

In a broad sense, the term ‘trust’ and the term ‘legitimacy’ can be used interchangeably in this model, but I rely more on the term ‘trust’, as ‘legitimacy’ is a bit more government-specific, while ‘trust’ is more about the state as a whole, irrespective of government and power and focused more on the state apparatus. ‘Legitimacy’ also conveys notions related to a government being properly elected or powers being specifically allocated to rulers.

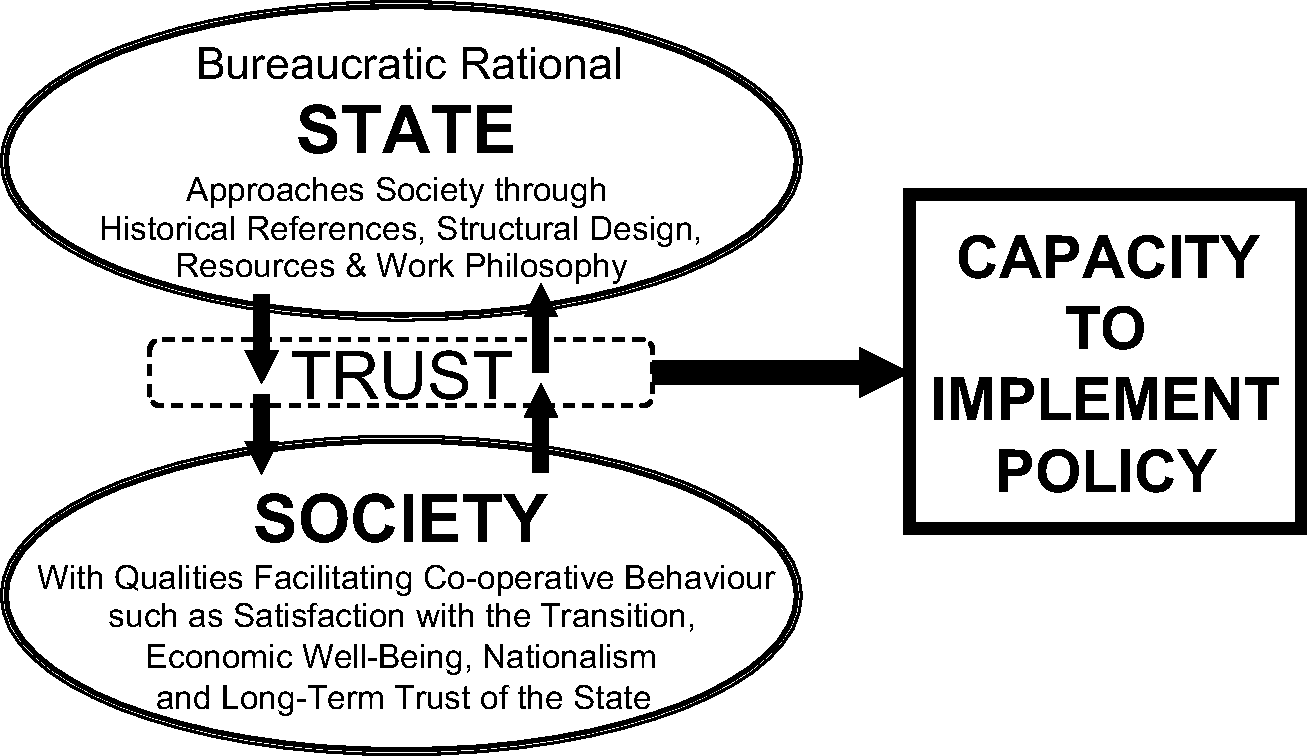

As shown in Figure 2.1, in this new model of state capacity for the post-communist states, state and society interact with each other through trust, enabling policy implementation. With respect to the state, if the question were only about building up resources and improving design, as the state structural theory would predict, then with a good police, army and military, citizens should be frightened and coerced into cooperating with the state. Instead, this new theory predicts that the state can be most effective when it involves civil society by creating citizens’ trust in itself. In short, a strong, independent civil society would choose to comply with the state rather than turn away when it trusts the state. Trust is essential. When citizens trust their state, they rely on the state to fulfil its commitments to them.

Figure 2.1 A model of state capacity for the post-communist states

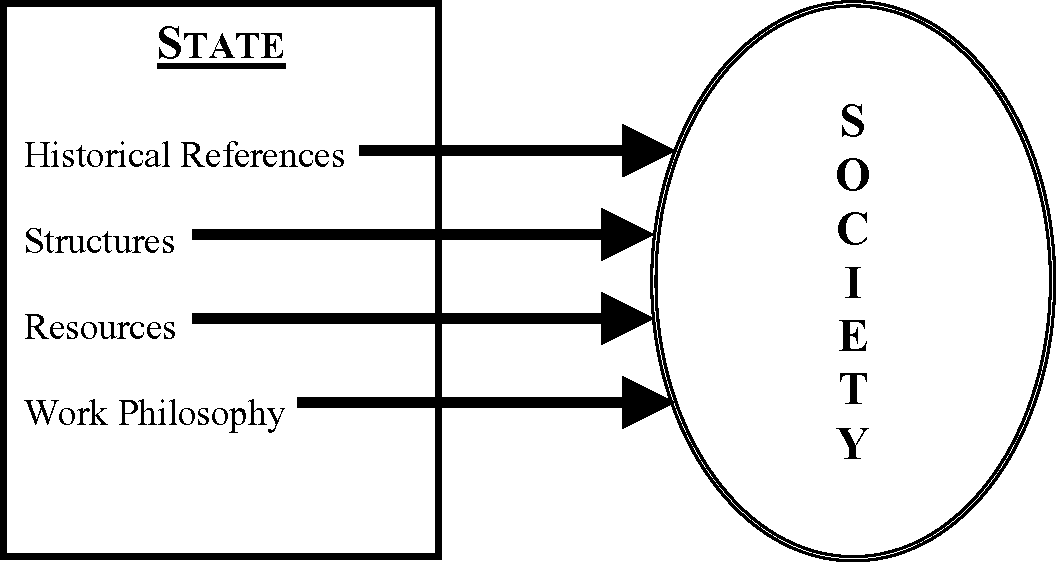

To be capable of building and drawing upon trust on the part of society, the state must be bureaucratically rational in a Weberian sense. In looking within the bureaucratic rational state itself, as shown in Figure 2.2, there are four principal aspects highlighted here: the use of constructive historical references of state–societal interaction (where available), efficient and well-organized structures, human and technological resources and a productive work philosophy.Footnote 105 All of these need to be oriented towards society so that trust can be built up. Hence, where attitudes of trust in the state prevail, individuals and groups in society will comply with the state regarding the given policy area, and there will be more successful policy implementation.Footnote 106

Figure 2.2 Where to find bureaucratic rationalism within a state

In general, trust may be defined, as Piotr Sztompka does, as ‘a bet on the future contingent actions of others’.Footnote 107 In contrast to certainty, trust, then, reflects one's confidence that others – either individuals or institutions – will act as one would expect they would and prove to be trustworthy.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that trust in the state is not synonymous with the other form of trust – trust in others, which has been referred more popularly to as social capital in the field of political science. Simply put, trusting the state to provide goods and to treat others fairly is not related to citizens’ trust in one another. Moreover, cross-country survey research has shown that such trust in the institutions of democratic governance is not correlated with social capital. ‘[T]here is no strong correlation between political trust, defined as trust in democratic institutions, and social trust’, Bo Rothstein has observed. ‘This has led many researchers to conclude that there is no convincing evidence showing that trust in democratic institutions produces social trust and social capital.’Footnote 108

In fact, with respect to post-communist Russia, Alena Ledeneva has observed that there is a lack of trust in newly built institutions, while at the same time there actually are really strong interpersonal ties within Russians’ relationships with one another.Footnote 109 Hence, a citizen can trust or not trust his or her government, but that type of trust is entirely different from the type of trust he or she has in others. We simply expect different things from other individuals than we do from our state. The ability to trust others on an immediate, close basis is quite different from providing a trusting relationship with the state writ large.