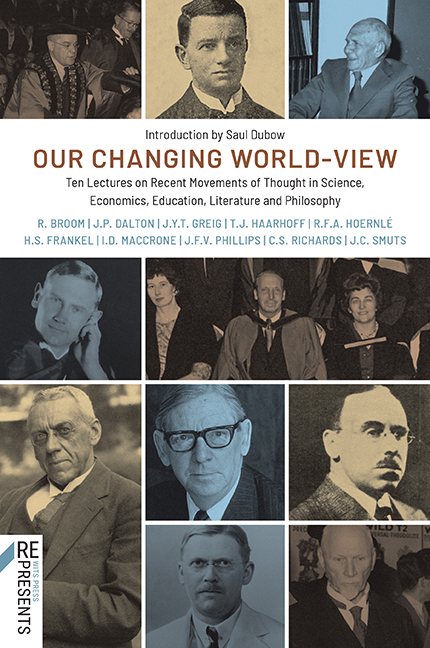

Our Changing World-View

Our Changing World-View Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2021

Several times since I selected the above title for my lecture I have wished that I had chosen a different one, for affairs in the economic world are changing so rapidly that it is extremely difficult to give any sense of perspective, though the position is not quite so bad as a recent correspondent to our University paper would have one believe when he said ironically that “to all who have studied economics as recently as even last week it is evident that what they have learnt is absolutely out of date.” In any case, its obviously changing character, often, indeed, more obvious than real, relieves one of the necessity of proving it; nor is our economic world apparently nearly as bad as the physical universe, which, according to a recent writer, “was once upon a time all tidy, with everything in its proper place, but ever since then has been growing more and more disorderly, until nothing but a drastic spring-cleaning can restore it to its pristine order.”

That flux and change are inherent in our economic world should be obvious to all, though the fact of change is not readily recognized by many, whose concern it is, with unfortunate results to Society; or, often, what is changing is frequently misunderstood. Variations in standards of living, changes in the mobility and supply of labour, alterations in the amount of capital available for investment, changes in the birth and death rates, exhaustion of supplies of raw materials and the substitution of others, changes in demand and in price levels, in the fruitfulness of the earth and the plenteousness of Nature, combined with new inventions and new ideas of economic organization make economic co-ordination much like doing “a jigsaw puzzle on a rolling ship.”

The changes I have enumerated are often more obvious than real, more apparent than basic, and I want this evening to distinguish if possible between these two kinds of economic change, between what is superficial and what is fundamental, and endeavour to leave you in the possession of certain principles in the light of which the present apparent chaos can be judged.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure no-reply@cambridge.org is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.