Introduction

Globally, women’s representation in national legislatures has almost doubled in the last two decades. A rich literature has examined whether and how women’s increased presence in legislatures affects the advancement of women’s interests, issues, and priorities in public policy. Across a variety of cases, gender and politics scholars generally find that women’s presence in politics is associated with increased advocacy for policies that advance the status of women as a group (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019; Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). Yet, scholars also find that the strength of this relationship is highly contingent. Institutional rules and norms constrain women representatives’ willingness and capacity to advocate for women’s interests in the legislative process (Barnes Reference Barnes2016; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009).

This paper examines one potential constraint to women’s legislative behavior: party discipline. Whereas scholars of intraparty variation in party discipline have examined how mutable MP characteristics, such as seat type, shape legislators’ incentives to toe the party line (Benedetto and Hix Reference Benedetto and Hix2007; Kam Reference Kam2009), the role of MP gender has been less central in this research. In a separate literature, gender scholars have documented cases in which women tend to exhibit more party discipline than their men colleagues and have noted that party loyalty seems to inhibit some women representatives from taking stronger positions on women’s rights (see e.g., Britton Reference Britton2010; Cowley and Childs Reference Cowley and Childs2003; Goetz and Hassim Reference Goetz and Hassim2003; Walsh Reference Walsh2010, chap. 7).Footnote 1 Our work brings together these literatures to theorize about the origins and consequences of gender differences in party discipline. Empirically, we focus on a world region where studies of legislative behavior in general and party discipline in particular are rare: Africa’s emerging party systems.

Using member of parliament (MP) survey data from African legislatures, we ask the following: (1) Do women legislators exhibit more party discipline than men representing the same parties? and (2) How do any observed gender differences in party discipline affect women representatives’ prioritization of women’s rights in their legislative work?

We theorize that women MPs are more constrained by expectations of party discipline than are men and that this constraint may occur through two channels: In the first, we argue that parties tend to recruit and select men and women legislators based on different criteria, leading to the (s)election of more disciplined women than men. We theorize this occurs because women are less able than men to use clientelism to establish a political following and thus have less latitude to depart from the party line. Moreover, drawing from feminist institutionalism, we argue that whereas men can rely on homosocial capital to advance in their parties, women, as historical outsiders, must do more to signal their commitment to the party, including through outward displays of party loyalty. As a second channel, drawing on role congruity theory we argue that, once elected, gendered expectations about proper behavior constrain women MPs’ ability to go against their parties. Finally, regardless of which of these two broad channels is at play—gendered recruitment patterns or gendered expectations of parliamentary behavior—we theorize that women MPs with higher levels of party discipline will be less likely to list women’s rights as a top government priority than less disciplined women.

We test our expectations through a survey of over 800 parliamentarians in over 100 political parties in 17 African countries collected through the African Legislatures Project (ALP) (see Barkan et al. Reference Barkan, Mattes, Mozaffar and Smiddy2010). Our analysis includes all of the continent’s large democracies as well as the majority of its hybrid regimes.Footnote 2 The countries in our sample cover over half of the continent’s population and include over 25% of the legislators from these parliaments. These cases are ideal for examining the causes and consequences of women’s legislative behavior. Women’s representation in African parliaments has doubled in the last 15 years and tripled in the last 25 in large part due to the rapid diffusion of electoral gender quotas across the region (see Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008). Many African nations are now world leaders in women’s parliamentary representation; for instance, the single or lower parliamentary houses of Senegal, Namibia, South Africa, Rwanda, and Mozambique all consist of 40% women or more. Yet how women’s presence affects policy making in these rapidly diversifying legislatures is still underexplored.

In line with our expectations, we find that women report significantly higher levels of party discipline than do men parliamentarians representing the same party. These results hold when controlling for MP characteristics such as the MP’s time in office and ministerial and party leadership positions as well as pre-election variables, including education and previous political experience. In a separate exercise, we validate our self-reported measure of party discipline by examining gender differences in legislative speech patterns that should be associated with party discipline. Relying on new data that we generate from parliamentary debate transcripts from five of our cases, we find that women MPs speak significantly less than do men MPs during parliamentary debates. And, when they do speak, we find that women refer to their parties more frequently than do men. Returning to the ALP data, confirming our expectations from our second research question, we find that women who report higher levels of party discipline are less likely to prioritize women’s rights as a top legislative issue than are less disciplined women. Finally, we supplement our quantitative analysis with a qualitative case study of the Namibian Parliament. Relying on dozens of elite interviews conducted over multiple years, we illustrate how party loyalty serves to constrain both the selection and behavior of women representatives.

In addition to contributing to research on party discipline, our work contributes to the growing scholarship linking women’s presence in political decision making to substantive outcomes that benefit women as a group (Clayton and Zetterberg Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018; Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). Our findings here are consistent with the general consensus from this body of work: across levels of party discipline, women MPs are more likely than men MPs to list women’s rights as a top government priority. Yet, at the same time, the election of women party loyalists as opposed to less constrained women appears to weaken the potential for an even stronger women’s rights lobby in parliament.

Our results also have notable, albeit mixed, implications for the potential consequences of diversifying parliaments on legislative development. On one hand, legislative scholars typically consider cohesive political parties as an essential building block to strong functioning legislatures. Disciplined parties provide party cohesion and are thus crucial for providing voters with consistent policies and for governments to advance their agendas. On the other hand, African legislatures and parties are considerably weaker than those in established democracies, and in such contexts party discipline is far more ambiguous, particularly if it shores up rather than serves as a check on executive strength (see Barkan Reference Barkan2009; Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2018; Opalo Reference Opalo2019). That women’s rising numbers are also ushering in cohorts of more disciplined parliamentarians presents a decidedly ambiguous picture of the prospects for continued democratization among Africa’s emerging party systems.

Party Discipline in African Legislatures

Scholars typically define party discipline as party members’ acquiescence to the demands of the party’s leadership, typically because the leadership has the means to induce recalcitrant party members to act upon their commands (Bowler, Farrell, and Katz Reference Bowler, Farrell and Katz1999, 4). In this way, party discipline is a tool that aids party cohesion: the degree to which party members work together in pursuance of the party’s goals (Özbudun Reference Özbudun1970, 305). Party discipline thus provides party leaders with the means to push members to act in a united way even when they disagree on policy (Raymond and Overby Reference Raymond and Overby2016). Although there is variation across party systems, party leaders typically discipline members through their control of renomination and promotion procedures, as well as MP committee assignments, staff allocation, and spending on constituency development (Kam Reference Kam2009).

Party discipline in Africa’s emerging democracies tends to be weaker than in established democracies, in large part because parties typically lack clear programmatic differences and because legislatures themselves tend to be weakly institutionalized (Barkan Reference Barkan2009; Elischer Reference Elischer2013). In instances in which “there are real issues at stake between legislative parties” (Barkan Reference Barkan2009, 236), party discipline is enforced through measures similar to those used in more consolidated democracies. For instance, in political parties in which party leaders control candidate (re)selection (mostly in closed-list proportional representation [PR] systems), party members who vote against the party line run the risk of being denied renomination or even losing their seats midterm (Barkan, Reference Barkan2009). Another universal mechanism is party leaders’ control over promotion to ministerial positions. These posts carry particular value in African legislatures because they grant access to state resources (Arriola and Johnson Reference Arriola and Johnson2014, 497). More broadly, access to public funds and business contracts are important means to induce MP loyalty. More than in established party-based democracies, such access aids reelection efforts, as African MPs are often dependent on the services they provide to their constituencies for reelection (Barkan and Mattes Reference Barkan and Mattes2014). Finally, ruling parties in African parliaments can also threaten to mobilize state resources against disloyal party members, including using state resources or voter intimidation to support challengers in the party primaries (Opalo Reference Opalo2019).

To analyze party discipline, most scholarship examines MP roll-call votes to examine the frequency with which MPs depart from a majority of their copartisans. However, in Africa, recorded roll-call votes are exceptionally rare. Rather, MPs will either voice their support or opposition in a plenary vote that is not recorded or cast a secret vote which is meant to shield MPs from potential repercussions from the executive branch. MPs can also engage in expressions of party discipline through other fora. Work within ministries and inter- and intraparty caucuses as well as participation in standing committees and plenary debates are all arenas for MPs to influence legislation, amend state budgets, or engage in executive oversight. Through these venues, MPs may choose to behave in ways that either align with their parties’ chapter-and-verse or to exert more independence.

Gender and Party Discipline: Previous Work

While party cohesion is imperative for meeting party goals, legislators’ personal incentives sometimes clash with those of their party. Given the large body of work that suggests that women MPs tend to prioritize women’s interests, issues, and perspectives more than the men in their parties, women MPs may have a personal incentive to push harder on gender-equality issues than what their party platforms stipulate.Footnote 3 As such, gender scholars commonly portray party discipline as something negative, as a constraint to women’s maneuverability within their legislatures, and as a potential obstacle to women’s substantive representation (see e.g., Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012).

Yet is party discipline gendered? Past studies from the United Kingdom, the United States, and Ukraine have found that women MPs (or specific groups of women MPs) are less likely than are men to vote against the party line (Cowley and Childs Reference Cowley and Childs2003; Heuwieser Reference Heuwieser2018; Hogan Reference Hogan2008; Thames and Rybalko Reference Thames and Rybalko2011). One cross-national study of consolidated democracies with gender as a control variable finds a similar relationship, but the results are not statistically significant (Shomer Reference Shomer2016). An exception to this pattern is an analysis of the Korean National Assembly, which finds that women elected to single-member districts (but not those in PR seats) are more likely to rebel than are men (Jun and Hix Reference Jun and Hix2010). Thus, although there may be important variation across (and within) cases, most existing quantitative studies suggest that women are more likely to toe the party line than are men.

Specific to African parliaments, rich qualitative accounts have detailed the many ways that politicians must manage pressure from party leaders in their legislative work and that this pressure might be more acutely felt by women (Goetz and Hassim Reference Goetz and Hassim2003). The widespread adoption of gender quotas in African legislatures may further exacerbate the pressure women feel to toe the party line, particularly among women in ruling parties who often owe their positions to government-initiated gender quotas (see Longman Reference Longman, Britton and Bauer2006; Tamale Reference Tamale1999, 105). In addition, many Africanist scholars have detailed how party discipline limits the ability of women MPs to use their positions to lobby for women’s rights reforms. For example, scholars of South African politics have noted how the increasingly centralized nature of the ruling party has limited the ability of women MPs to make use of their numbers to collaborate on women’s rights legislation (Britton Reference Britton2010; Hassim Reference Hassim2003; Walsh Reference Walsh, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). Relying on MP interviews in Cameroon, Fokum, Fonjong, and Adams (Reference Fokum, Fonjong and Adams2020, 1) make a similar claim, noting that “Cameroon’s executive-dominant political system and norms of party loyalty impede the ability of women MPs to advance gender equity legislation.”Footnote 4

Taken together, quantitative work (mostly from consolidated democracies) and qualitative studies of African parliaments generally find that women are more party loyal than are men. We bring together this previous work to develop and test a unified theory explaining gender differences in party discipline. Our analysis does so in world region that has received little empirical attention, despite the relevance of our cases to theory building on the origins of gender differences in legislative behavior. Expanding on previous work, we also provide the first comparative measure of the consequences these gender differences have for the substantive representation of women’s interests in legislative policy making.

A Gendered Theory of Party Discipline

We theorize that women parliamentarians will express higher levels of party discipline than do men in their parties due to gendered dynamics along two dimensions. First, we theorize that parties will select and advance disciplined women, while men are less bound to this pathway to office. Second, we posit that social gender norms constrain women MPs’ behavior and compel women to act in ways that are less assertive than those of the men in their parties. We also consider several alternative explanations that might account for the emergence of a discipline gender gap, such as gender differences in MPs’ parliamentary tenure or women’s selection into party systems that favor party loyalty. Finally, because women’s rights reforms are often controversial, particularly if they fundamentally challenge patriarchal authority, we argue that more disciplined women will be less likely to list women’s rights as a top legislative priority than more independent women.

Gender and Candidate Selection

Our argument on gender and candidate selection primarily draws on two literatures. The first is work that suggests electoral and party systems shape the emergence of various types of candidates, and these candidate types, in turn, tend to exhibit different legislative behaviors (Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Siavelis and Morgenstern Reference Siavelis and Morgenstern2008). While our argument is generally comparative, we draw heavily on work on candidate selection in African politics. Second, we draw from feminist institutionalist scholarship that suggests that men and women are subject to different informal rules and norms that shape how party elites recruit and select legislative candidates (see e.g., Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2016; Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995). We argue that even within the same parties or party systems, women are more likely than are men to emerge as party loyalists. Moreover, we argue that even among party loyalists, women tend to be subject to stricter expectations than men to toe the party line.

To begin, we theorize that whereas several different pathways to candidacy are open to men politicians, fewer tend to be open to women. Around the world, politicians in emerging democracies and hybrid regimes often come to power through their prominence in local clientelistic networks (Stokes Reference Stokes and Goodin2009). Work from Pakistan (Mufti and Jalalzai Reference Mufti and Jalalzai2021) to Argentina (Daby Reference Daby2021) suggests that men have more success than women in using clientelism to build a political following. Moreover, in African elections, clientelistic networks often overlap with ethnic politics, which can further reinforce women’s exclusion (Arriola and Johnson Reference Arriola and Johnson2014).Footnote 5 Put another way, almost by definition, “big men” in African politics tend to be men. Parties view these men as particularly valuable, as they bring in ethno-regional blocks of voters or other resources to the party (Arriola and Johnson Reference Arriola and Johnson2014; Beck Reference Beck2003; Muriaas, Wang, and Murray Reference Muriaas, Wang and Murray2019).Footnote 6 Legislators who emerge from clientelistic networks tend to be less beholden to party leaders for their (re)nomination and thus are less compelled to express high levels of party discipline (Siavelis and Morgenstern Reference Siavelis and Morgenstern2008). In contrast, we argue that one of the few opportunities for women to advance in their parties is to take on the legislative style of the party loyalist. Candidates of this type owe their positions to the active support of party leaders, and thus have heightened incentives to toe the party line or risk losing future support.

Moreover, we argue that even among candidates who are in party systems that privilege loyalist candidates (such as closed-list PR systems) or in electoral systems in which ethnicity is less politicized or clientelism is less severe, women are still at a disadvantage. This is because women may have a more difficult time signaling their loyalty to the party than will men. Feminists institutionalist scholars have documented how parties dominated by men tend to reproduce existing gender power asymmetries (Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005). Informal party networks determine who is selected to stand for and advance within party hierarchies. When party elites make decisions about which candidates to support for election or appoint to important posts, they look for individuals already within their networks. Party gatekeepers have traditionally perceived women as outsiders: those not meeting formal or informal criteria for becoming candidates (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013). While men may lean on informal connections and homosocial capital to advance in their parties, women may need to signal their merit not by virtue of their connections to preexisting networks but by their stated and observed commitments to the party.

Whereas our feminist institutionalist argument about candidate selection draws from comparative accounts across a number of world regions, we expect it to pertain well to African parliaments. Men have traditionally dominated both formal and informal leadership positions in African politics, a tendency often codified during colonial rule (Tamale Reference Tamale1999, chap. 1). Many ruling African parties developed out of struggles for independence from colonial rule or from military groups that fought during civil conflicts after independence (Opalo Reference Opalo2019; Riedl Reference Riedl2014). In their capacity as freedom fighters, warlords, or rebel leaders, men often came to dominate party leadership positions in postconflict governance (see e.g., Melber, Kromrey, and Welz Reference Melber, Kromrey and Welz2016). By extension, parties, as the key organizational feature of politics in the postcolonial era, tend to function as highly gendered institutions. Even when women have been able to lobby for inclusion and reform in postconflict legislatures (see Tripp Reference Tripp2015), these political institutions still tend to reinforce male authority (see e.g., Tamale Reference Tamale1999, chap. 5). Moreover, as party structures become increasingly institutionalized after times of social upheaval, men party leaders often entrench their positions within party hierarchies, leading, in some instances, to the return of socially conservative policies (Ahikire Reference Ahikire2014, 18; Walsh Reference Walsh, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012).

Our theorizing leads not only to our main implication—that women will express higher levels of party discipline than men—but also to two corollary implications that are consistent with this mechanism: first, women should be more likely than men to come to higher office from a previous political position and, second, previous political experience should be a stronger predictor of party discipline for women parliamentarians than it is for men parliamentarians. Related to the first implication, we expect that if women are investing in the party loyalist route to political office, we should observe gender differences in MPs’ occupational backgrounds: women should be more likely than men to have previously served in state or local government. Men, in contrast, should have more success than women in coming to higher office without first having had to climb the party ranks. Related to the second implication, we expect that the experience of serving in a previous political position will reinforce a sense of party loyalty in women to a greater degree than men if women in these positions learn that toeing the party line is particularly helpful in advancing in their parties. Because we expect men to have other career tactics available to them—in particular, homosocial capital and clientelism—we do not expect previous political experience to reinforce party loyalty to the same degree in men parliamentarians.

Gendered Expectations of Legislative Behavior

In addition to candidate selection, we also expect gender differences in party discipline to stem from gendered expectations about MP behavior. Our argument draws heavily on role congruity theory, which suggests that there are certain social roles attributed to men and women that come with prescribed behaviors (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Women tend to be associated with communal qualities (e.g., collaborating and caring for others), whereas men are associated with agentic qualities (e.g., being aggressive, competitive, and ambitious).Footnote 7 At its core, party discipline is about obeying rather than confronting party leadership. The former (obeying) is women’s expected behavior, whereas the latter (confronting) is not. As such, members of the (s)electorate may be more likely to punish undisciplined behavior when it comes from women. While parties or voters might tolerate “maverick” men, undisciplined women may have less influence in their legislative work and may be less likely to be renominated, reelected, or promoted (Baumann, Bäck, and Davidsson Reference Baumann, Bäck and Davidsson2019). In sum, assertive behavior, such as rebelling against the party line, may be a more effective legislative style among men than among women.

Many qualitative accounts describe how women in African legislatures are expected to conform to traditional gender roles. For instance, Tamale (Reference Tamale1999) describes the pervasiveness of sexual harassment in the Ugandan Parliament, which is filled with a “male ethos” that reinforces gender hierarchies. She describes how conforming to social expectations about gendered behavior is “political pragmatism” on the part of women MPs in all aspects of their legislative behavior (Tamale Reference Tamale1999, 122). Similarly, Berry, Bouka, and Kamuru (Reference Berry, Bouka and Kamuru2020, 16) describe how newly quota-elected women MPs in Kenya face physical and psychological violence as a form of backlash for breaking gender roles by entering male-dominated parliaments. Recalling interviews with party gatekeepers in Malawi, Kayuni (Reference Kayuni2016, 88) describes how “cultural attributes which expect women to obey their men extend into the political parties where most women remain virtually quiet.” Collectively this literature suggests that across African parliaments, norms associated with appropriate gender roles constrain the ability of women MPs to act assertively as a way to advance in their parties.

Other empirical work outside of African parliaments also suggests that men legislators tend to be rewarded for agentic behavior, while women legislators tend to be punished. Analyzing thousands of parliamentary speeches in Turkey, Yildirim, Kocapnar, and Ecevit (Reference Yildirim, Kocapnar and Ecevit2021) find that whereas men MPs who were active on the legislative floor were significantly more likely to get renominated and promoted in the party rank, women who were active in legislative speech making were less likely to be renominated and promoted. Similarly, research on ministerial selection in Sweden shows that women MPs who deviated from the party line during parliamentary speeches were less likely to be appointed to cabinet posts, whereas this pattern was not found among men (Baumann, Bäck, and Davidsson Reference Baumann, Bäck and Davidsson2019). We expect a similar dynamic in our cases. If women are penalized for assertive behavior such as active speech making, we should observe that debate participation is positively associated with reelection for men, but negatively associated with reelection for women. We test this implication with new data that we collect on MPs’ legislative speech patterns for a subset of our cases, detailed more extensively below.

Alternative Explanations

We also consider several alternative explanations that might predict higher levels of party discipline among women parliamentarians. First, women may report higher discipline because they are newer to their positions than are men. If this is the case, any observed gender gap should attenuate when we control for MPs’ parliamentary tenure. Second, because of disparate access, women MPs may have less formal education than do men MPs. If legislative independence is associated with higher levels of education, the gender gap in discipline should weaken once we account for MPs’ educational attainment. Third, it is also possible that women MPs have higher levels of party discipline because they select into highly disciplined parties or parliaments. In contrast to party systems in more established democracies, African parties tend to not be organized around ideological differences (Elischer Reference Elischer2013). African opposition parties tend to be weak, fractionalized, and based either on support from smaller ethnic groups or headed by political entrepreneurs hoping to challenge ruling party hegemony (Weghorst and Bernhard Reference Weghorst and Bernhard2014). Women may be more risk adverse than men as they choose political careers and thus more likely to affiliate with more established and stable ruling parties. Because ruling parties also tend to be more hierarchical and centralized, we expect ruling party MPs to express higher levels of party discipline than do opposition MPs. Finally, women’s representation tends to be higher in more party-centered electoral systems, such as in closed-list PR regimes, and such systems also tend to favor party loyalist candidates. Moreover, even within party-centered electoral systems, parties or parliaments that particularly favor loyalist candidates tend to have higher rates of women representatives (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Taylor-Robinson, Siavelis and Morgenstern2008). Broadly, controlling for MP party will allow us to test whether gender gaps in discipline are driven by women’s selection into disciplined parties or parliaments.

Party Discipline and the Prioritization of Women’s Rights

Our second research question is whether and how party discipline affects the substantive representation of women’s interests in policy making. We conceptualize women’s interests as issues that disproportionally affect the rights and well-being of women as a distinct social group—or more colloquially, as women’s rights. Higher levels of party discipline may be associated with women MPs’ decreased prioritization of women’s rights for at least three reasons, which might exist in any combination across our cases. First, if, as we argue, parties tend to select party loyalist women, these women might also happen to hold more conservative views about women’s rights and be less reformist than women who built their careers outside of political parties. Hassim (Reference Hassim2003, 88) comments on this occurrence in party-dominated systems like South Africa, noting, “party leaders will choose women candidates who are token representatives, least likely to upset the political applecart, rather than those candidates with strong links to women’s organisations.” Party loyalists are also less likely to use their positions to advocate for policy reform broadly, and women’s rights may be the sort of issue that implies significant reform (see Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2015). Additionally, it may be the case that undisciplined women are more likely to represent more progressive constituencies (such as in urban areas) than are women who are more party loyal.

Second, it is possible that women MPs may change their behavior once they realize that parties will punish them for speaking out on women’s rights issues in particular. In such cases, women MPs may come into parliament with feminist agendas, but come to learn both that their parties are not supportive of this agenda and, more generally, that adopting a disciplined legislative style is imperative for a successful career. Third, parties may tend to punish both women and men MPs who advocate for reforms broadly (see Barkan Reference Barkan2009), and reformist women may also be strong advocates for women’s rights. In such instances, it may be that women’s rights reforms are not controversial per se but rather that more outspoken women MPs prioritize women’s rights in addition to other issues that go against the party line. For example, a Ugandan activist describes how women legislators who advocated for women’s rights along with democratic reforms have been selectively kicked out of Uganda’s hegemonic ruling party, noting,

Maria Mugene was a lecturer in women’s studies before she came into politics. She had a falling out with the government about lifting presidential term limits… . The state mobilized people against her. She managed to get reelected, but she wasn’t reappointed to cabinet. In the 2011 election, she opted not to stand, because she knew what was coming. Maria Matembe [a prominent Ugandan feminist], the same thing. She opposed the removal of term limits, so she was successfully ousted in the election after that.Footnote 8

Below we offer some preliminary tests to adjudicate between these three mechanisms, but our main contention is that all three imply a negative correlation between party loyalty and the prioritization of women’s rights, specifically among women legislators. Implicit in our argument is the expectation that men MPs, on average, will not advocate for women’s rights to the same degree as will women MPs, and thus they will show little variation in this tendency across discipline levels. This expectation is borne from previous work from African legislatures that repeatedly shows that women MPs prioritize women’s rights in their legislative work to a greater degree than do their men copartisans (Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2017; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019). Put another way, our expectation is that highly disciplined women MPs will look more like (all) men MPs in their tendency to list women’s rights as a top priority, whereas undisciplined women will be the group most likely to push for women’s rights.Footnote 9

Case Selection and Data

Our sample includes 17 emerging democracies and hybrid regimes that are typical of Africa’s Third Wave democratizing states. By the mid-1990s, the majority of African countries returned from periods of postcolonial conflict or other authoritarian rule to multiparty elections and began to form legislative branches with some degree of capacity and autonomy (Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and Walle1997). A few legislatures—most notably the Kenyan and South African Parliaments and to a lesser degree the Ugandan Parliament—emerged as semi-independent branches of government that have been able to yield significant legislative influence and at times have served as checks on executive power (Barkan Reference Barkan2009; Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2018; Opalo Reference Opalo2019). The countries included in our sample are representative of states that have successfully transitioned to democratic governance (e.g., Ghana, Botswana), are aspiring democracies (e.g., Kenya, Malawi), or are hybrid regimes that allow active legislatures with relatively free opposition parties (e.g., Nigeria, Tanzania). Our sample includes all of Africa’s emerging democracies (excluding small island nations), as well as a majority of its hybrid regimes.Footnote 10

We test the main implications of our theory with survey data collected through the African Legislatures Project (ALP), a research effort initiated by the Center for Social Science Research at the University of Cape Town (see Barkan et al. Reference Barkan, Mattes, Mozaffar and Smiddy2010). ALP conducted MP surveys between 2008 and 2011 with a random sample of 50 lower-house MPs in 17 countries. The response rates were very high for elite surveys, averaging 80% across cases. In total, the data include survey responses from 813 MPs in 109 parties, representing 25% of the total population of MPs across the 17 countries. Women MPs are 17.7% of respondents (

![]() $ n $

= 144), similar to the 19.1% of the total parliamentary seats held by women in the 17 cases at the time of the surveys. We report further details on the ALP data collection effort in SI § 2.

$ n $

= 144), similar to the 19.1% of the total parliamentary seats held by women in the 17 cases at the time of the surveys. We report further details on the ALP data collection effort in SI § 2.

We measure party discipline through MPs’ responses to six survey questions. Table 1 contains the question wording and original coding, with higher values associated with higher levels of party discipline. MP responses are correlated across the six questions (ranging from

![]() $ \rho $

= 0.11 to

$ \rho $

= 0.11 to

![]() $ \rho $

= 0.63), and load well onto a single factor (Cornbach’s

$ \rho $

= 0.63), and load well onto a single factor (Cornbach’s

![]() $ \alpha $

= 0.79), and we thus elect to use factor analysis to generate a composite score. Prior to construction of the composite score, component variables are mean-centered and standardized, so the indices have a mean of zero. A simple two-tailed t-test reveals a significant difference in women’s and men’s self-reported party discipline: men have an average score of -0.056 and women have an average score of 0.262 (see Table 2, difference significant at

$ \alpha $

= 0.79), and we thus elect to use factor analysis to generate a composite score. Prior to construction of the composite score, component variables are mean-centered and standardized, so the indices have a mean of zero. A simple two-tailed t-test reveals a significant difference in women’s and men’s self-reported party discipline: men have an average score of -0.056 and women have an average score of 0.262 (see Table 2, difference significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.001), a point difference associated with about half of a standard deviation on the composite index. We also find gender differences for each composite variable (five of these are significant at

$ \le $

0.001), a point difference associated with about half of a standard deviation on the composite index. We also find gender differences for each composite variable (five of these are significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.05 or lower, and the sixth is significant at

$ \le $

0.05 or lower, and the sixth is significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.10, see SI § 3, Table A2).Footnote

11

$ \le $

0.10, see SI § 3, Table A2).Footnote

11

Table 1. Coding of Party Discipline

Note: Higher values correspond with greater MP discipline and lower values correspond to lower MP discipline.

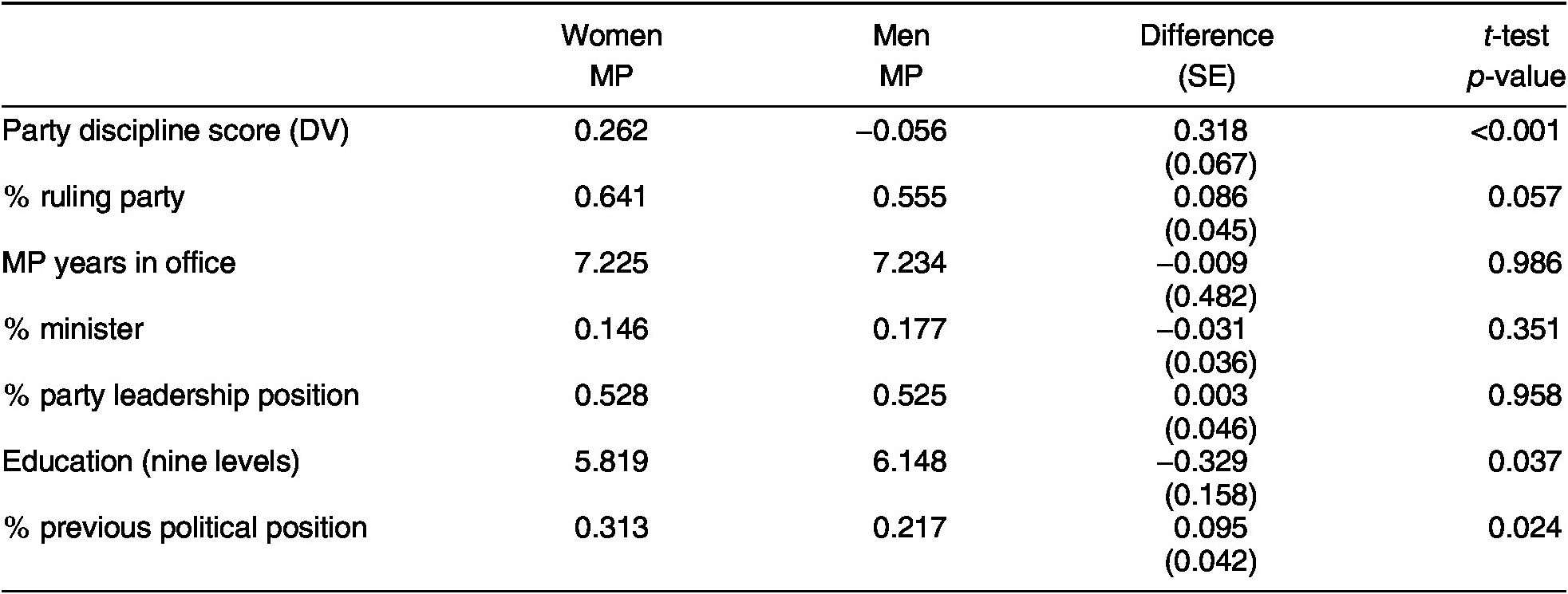

Table 2. Descriptive Characteristics by MP Gender

Note: N women MPs = 144; N men MPs = 668.

Descriptive Gender Gaps

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for women and men MPs, including the composite discipline score as well as other postelection characteristics that serve as controls in the multivariate analyses that follow: MP years in office, appointment to a ministerial post, a position in the party leadership, and ruling party membership. We also include two pre-election characteristics: highest level of education (on a nine-level scale from no formal schooling to a postgraduate degree) and whether the MP held a lower political position (e.g., a district or local councilor position) prior to being elected. We calculate the gender gaps for each characteristic and note their statistical significance with standard two-tailed t-tests.

Aside from our dependent variable, party discipline, three other gender gaps are statistically significant at the p

![]() $ \le $

0.10 level or below. The first is previous political experience. Above, we hypothesized that an implication of our argument about gendered pathways to power is that women more than men will tend to come to higher office from a previous political position. We find support for this implication: 31.3% of women MPs held a lower political post prior to their election, compared with 21.7% of men MPs (difference significant at

$ \le $

0.10 level or below. The first is previous political experience. Above, we hypothesized that an implication of our argument about gendered pathways to power is that women more than men will tend to come to higher office from a previous political position. We find support for this implication: 31.3% of women MPs held a lower political post prior to their election, compared with 21.7% of men MPs (difference significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.05). We also observe that 56% of men MPs are members of the ruling party, compared with 64% of women MPs (difference significant at

$ \le $

0.05). We also observe that 56% of men MPs are members of the ruling party, compared with 64% of women MPs (difference significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.10), and, on average, women appear to have slightly less formal education than do men MPs (difference significant at

$ \le $

0.10), and, on average, women appear to have slightly less formal education than do men MPs (difference significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.05).Footnote

12

$ \le $

0.05).Footnote

12

Results

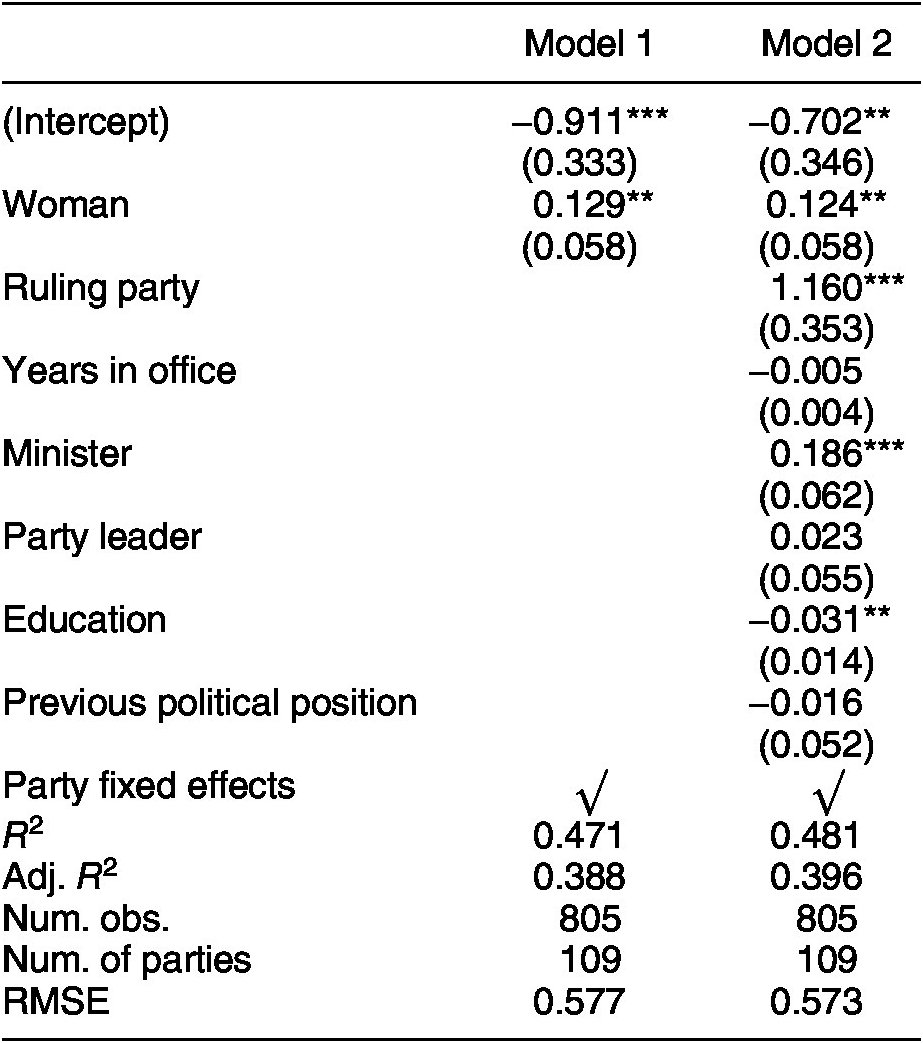

Gender Differences in Party Discipline

We expect that gender differences in party discipline will hold when controlling for other MP characteristics. To test this expectation, we first run a basic OLS model with party fixed effects. The inclusion of these fixed effects allows us to compare gender differences among MPs in the same country and in the same party.Footnote

13

Model 1 in Table 3 shows the gender gap in party discipline in this basic comparison. Controlling for party substantially reduces the magnitude of the descriptive gap presented in Table 1 (from 0.32 to 0.13 on the composite index), but the difference retains statistical significance at the

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.05 level. This reduction in effect size supports other empirical work that finds that women select into more disciplined parties and party systems (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Taylor-Robinson, Siavelis and Morgenstern2008). Yet, importantly, a gender gap remains even among copartisans.

$ \le $

0.05 level. This reduction in effect size supports other empirical work that finds that women select into more disciplined parties and party systems (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Taylor-Robinson, Siavelis and Morgenstern2008). Yet, importantly, a gender gap remains even among copartisans.

Table 3. The Relationship between MP Gender and Party Discipline

Note: OLS models. Dependent variable: party-discipline composite score. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

From the baseline fixed-effects model, we also include the MP covariates listed in Table 2 as control variables. The inclusion of these variables does not change the estimated gender difference in party discipline. In Model 2 in Table 3, we observe that women MPs score about 0.12 higher on the composite discipline index, associated with about 0.2 standard deviations on this scale. This represents a persistent small to moderate effect size between men and women copartisans, slightly less than the associated increase in party discipline expressed by ministers compared with backbenchers in the sample.Footnote 14

Validating the Dependent Variable: A Behavioral Measure of Party Discipline

Our measure of party discipline is self-reported, and a potential concern is that these self-reports are not representative of actual MP behavior. To address this concern, we collect new data on one form of MP behavior that is recorded in at least some of our cases during the ALP survey year: MP speech. Expanding on similar work from Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang (Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014; Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2017), we obtained the parliamentary transcripts (Hansards) for five cases in our sample (Ghana, Namibia, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) either through debate archives on parliamentary websites or through records obtained by contacting parliamentary librarians (for more details, see SI § 7). We code speech patterns for all 992 parliamentarians across these five legislatures. Although we cannot match speech patterns with the anonymized MPs in our survey, we can examine whether there are gender differences in legislative speech that we theorize should correspond with party discipline. We do this in two ways. First, we expect that more disciplined MPs will contribute less to parliamentary debates, on average. This expectation accords with the many qualitative accounts noted throughout that suggest that loyalist women MPs are relatively silent during plenary debates. More generally, speaking at great length in parliamentary debates is a way for MPs to represent various party factions or to bring new issues up for debate that have not been sanctioned by party leaders (on the Namibian case, see, e.g., Tjirera and Hopwood Reference Tjirera and Hopwood2007).

In all five cases, we find that women MPs speak less during plenary debates than do their men copartisans (see Figure A1, SI § 7). To allow for comparison across cases, we standardize the number of words spoken during all plenary debates (excluding official ministerial statements) during the ALP survey year. Standardized scores thus represent within-country standard deviations from the mean. Across countries, on average, we find that women speak about 0.2 standard deviations less than their men copartisans. In a basic OLS regression with party fixed effects, the coefficient for MP gender is significant at the

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.05 level (see Table A7, SI § 7).

$ \le $

0.05 level (see Table A7, SI § 7).

As a second and perhaps more direct test, we measure how many times each MP references his or her own party during speech making as a percentage of the total words he or she speaks. We skimmed the Hansards in the five countries to get a sense of how MPs refer to their parties. This is usually done as a form of praise (e.g., in Namibia: “The SWAPO Party Government has shown its steadfastness in fulfilling the expressed needs of our people”) or in reference to a particular party policy (e.g., in Uganda: “When the NRM Government came to power, it took up a policy of declaring HIV/AIDS as a pandemic for the country”, see SI § 7 for more textual examples). We find that conditional on speaking, women MPs make reference to their parties 40% more frequently than do their men copartisans (0.035% vs. 0.025% of total words spoken). In an OLS regression with party fixed effects, the coefficient for MP gender is significant at the

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.05 level (see Table A8, SI § 7). Together these findings indicate both that women MPs speak less than do men MPs, on average and that, when they do speak, women emphasize their positions as party members more so than do men. These gender differences in MP behavior give us increased confidence in our self-reported measure and in our main finding: women tend to express higher levels of party discipline than their men copartisans in Africa’s emerging party systems.

$ \le $

0.05 level (see Table A8, SI § 7). Together these findings indicate both that women MPs speak less than do men MPs, on average and that, when they do speak, women emphasize their positions as party members more so than do men. These gender differences in MP behavior give us increased confidence in our self-reported measure and in our main finding: women tend to express higher levels of party discipline than their men copartisans in Africa’s emerging party systems.

Evidence of Mechanisms

In order to better understand why women MPs are more disciplined than their men copartisans, we examine whether there is evidence consistent with our two proposed causal mechanisms: gendered candidate selection patterns and gendered expectations of legislative behavior. Related to the former, recall that above we found that women are more likely than are men to have prior political experience before entering higher office (see Table 2). Here, we also test whether previous political experience is a stronger predictor of party discipline for women than it is for men. We find some evidence that it is. In a model that regresses the discipline scores on our standard set of controls, party fixed effects, and an interaction between MP gender and previous political experience, we find that the interaction term is statistically significant at the

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.10 level (see Table A5 and Figure A1, SI § 6). In sum, we find evidence consistent with both corollary implications associated with the candidate selection argument: women are more likely to come to higher office with previous political experience and political experience serves to reinforce party discipline to a greater degree among women than among men.

$ \le $

0.10 level (see Table A5 and Figure A1, SI § 6). In sum, we find evidence consistent with both corollary implications associated with the candidate selection argument: women are more likely to come to higher office with previous political experience and political experience serves to reinforce party discipline to a greater degree among women than among men.

We also test one implication consistent with the role congruity mechanism. Using the Hansard data, we examine whether legislative speech is positively correlated with reelection for men, while negatively associated with reelection for women. We find some descriptive evidence in support of this claim. For men MPs, speech making is positively and significantly correlated with reelection (

![]() $ \rho $

= 0.12;

$ \rho $

= 0.12;

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.01), whereas there is a negative (albeit insignificant) correlation among women (

$ \le $

0.01), whereas there is a negative (albeit insignificant) correlation among women (

![]() $ \rho $

= −0.05;

$ \rho $

= −0.05;

![]() $ p $

= 0.549). Figure 1 plots the predicted probabilities from a basic logistic regression that regresses the likelihood of reelection on MP gender, the within-country standardized score of legislative speech, an interaction between gender and speech, and party fixed effects. The interaction term is at the threshold of traditional statistical significance levels, likely in part due to the limited number of women MPs who speak at great length during plenary debates (

$ p $

= 0.549). Figure 1 plots the predicted probabilities from a basic logistic regression that regresses the likelihood of reelection on MP gender, the within-country standardized score of legislative speech, an interaction between gender and speech, and party fixed effects. The interaction term is at the threshold of traditional statistical significance levels, likely in part due to the limited number of women MPs who speak at great length during plenary debates (

![]() $ p $

= 0.11; see Table A9 in SI § 8). Finally, we note that the general finding that women speak less than do men during parliamentary debates across all five cases may itself be an additional implication of this mechanism, as previous work suggests that women participate less in deliberative settings because of gendered expectations about proper behavior (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014). We thus treat the evidence associated with the role congruity mechanism as suggestive, yet tentative.

$ p $

= 0.11; see Table A9 in SI § 8). Finally, we note that the general finding that women speak less than do men during parliamentary debates across all five cases may itself be an additional implication of this mechanism, as previous work suggests that women participate less in deliberative settings because of gendered expectations about proper behavior (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014). We thus treat the evidence associated with the role congruity mechanism as suggestive, yet tentative.

Figure 1. Predicted Probability of Reelection for Men and Women MPs by Legislative Speech Making (Standardized within County)

Note: The interaction is significant at

![]() $ p $

= 0.11.

$ p $

= 0.11.

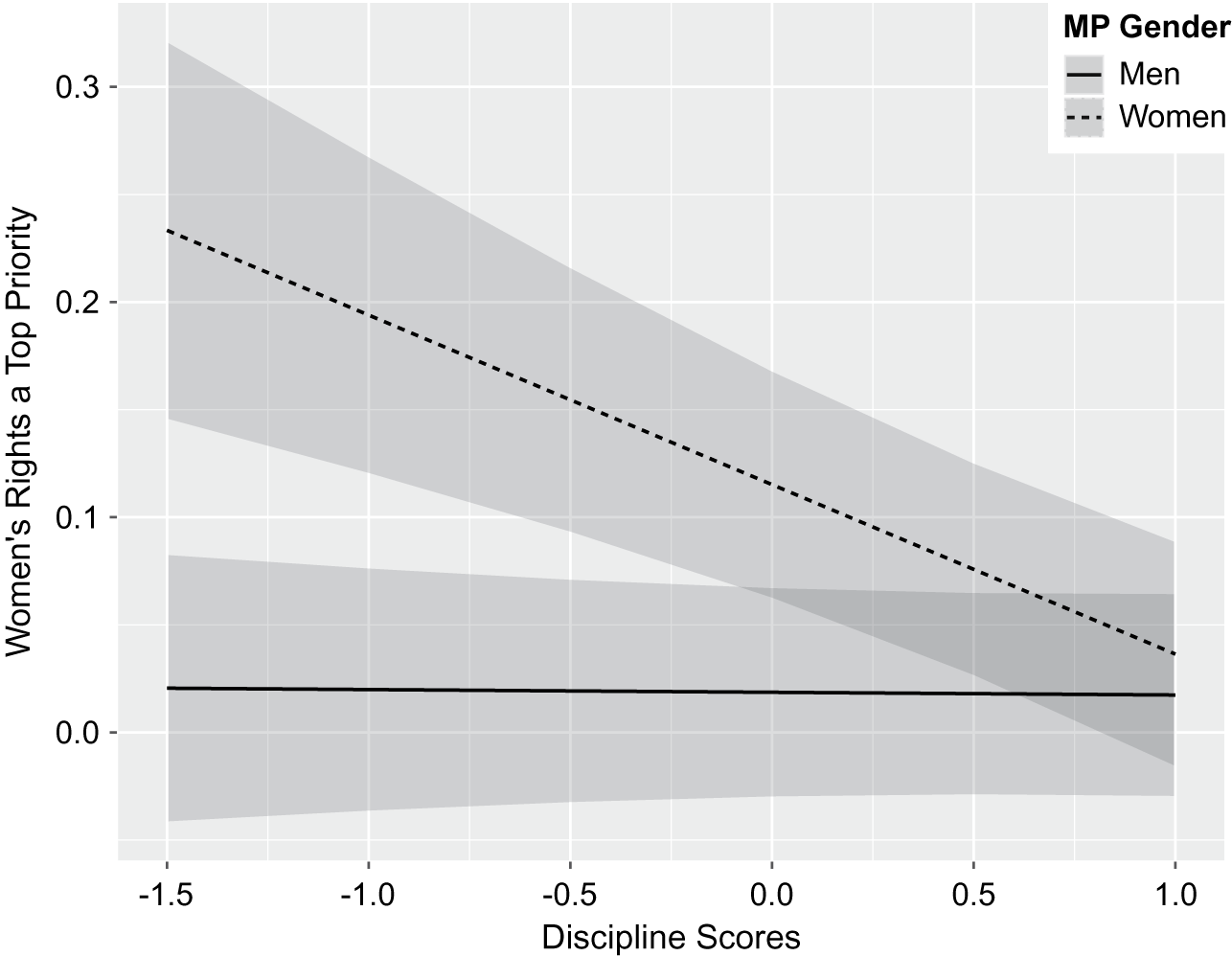

Party Discipline and Women’s Rights

Our second research question concerns how observed differences in party discipline are related to the likelihood that women MPs will prioritize women’s rights in their legislative agendas. To do this, we use a linear probability model to assess the likelihood that MPs will list women’s rights as a top government priority. The dependent variable is constructed from responses to an ALP survey question, which asks MPs, “In your opinion, what are the three most important problems facing this country that government should address?” Whereas issues such as the economy, public health, and poverty are generally more salient to both women and men than women’s rights, important gender differences do emerge: 10% of women MPs raised women’s rights as one the top three most important issues, while less than 1% of men MPs did so (also see Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019).

To assess the likelihood that women and men with varying levels of party discipline will prioritize women’s rights in their legislative work, we regress whether the MP listed women’s rights as a top government priority on the MP characteristics listed in Table 2, including party discipline, as well as party fixed effects. We continue to see a strong and significant tendency for women MPs to prioritize women’s rights to a greater degree than their men copartisans when controlling for other MP covariates (see Model 1 of Table A16, SI § 12). Next, we interact MP gender with the party discipline index. Here we see a strong negative interaction (significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.001; see Model 2 of Table A16, SI § 12). Women MPs with higher levels of party discipline are much less likely to list women’s rights as a top government priority than less disciplined women, whereas men, for their part, are unmoved. Figure 2 illustrates this finding by plotting predicted values for both men and women MPs across the range of discipline scores. Consistent with our expectations, we see that disciplined women behave more like men MPs on this issue and that it is undisciplined women in particular who most strongly prioritize women’s rights in their legislative work.

$ \le $

0.001; see Model 2 of Table A16, SI § 12). Women MPs with higher levels of party discipline are much less likely to list women’s rights as a top government priority than less disciplined women, whereas men, for their part, are unmoved. Figure 2 illustrates this finding by plotting predicted values for both men and women MPs across the range of discipline scores. Consistent with our expectations, we see that disciplined women behave more like men MPs on this issue and that it is undisciplined women in particular who most strongly prioritize women’s rights in their legislative work.

Figure 2. Predicted Values of the Prioritization of Women’s Rights for both Men and Women MPs by Party Discipline Score

Note: The interaction between gender and party discipline is statistically significant at

![]() $ p $

$ p $

![]() $ \le $

0.001.

$ \le $

0.001.

We theorize that women’s rights are associated with political independence because they often imply fundamentally challenging institutions that uphold patriarchal power or are associated with other broadly reformist attitudes. As a robustness check, we further probe whether women’s rights are indeed a distinct type of issue by testing how varying levels of party discipline are associated with the prioritization of two placebo issues for which we also observe significant gender gaps: health care and poverty. Women MPs tend to prioritize both of these issues more often than do their men counterparts (see Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019). Unlike women’s rights, however, we do not observe any differences between more or less disciplined women on these two issues (see Table A19 and Figures A5 and A6, SI § 13). It appears that the prioritization of women’s rights, in particular, is associated with party rebellion among women MPs.

Finally, while it is beyond the scope of this paper to extensively test why women with higher levels of party discipline are less likely to list women’s rights as a top priority, we offer a basic test of implications that arise from the mechanisms we theorized above. If it is the case that women legislators become both more disciplined and less likely to prioritize women’s rights over time or that parties selectively kick out outspoken feminist women, then we should observe that women who have been in office longer are both more disciplined and less likely to prioritize women’s rights than are more recently elected women. To test this, we run two models that respectively regress women’s rights prioritization and party discipline on our standard set of MP covariates including party fixed effects (see Figure A4 and Table A18 in SI § 12). The interaction term (MP gender × years in office) is not significant in either model. Moreover, the years in office coefficient is negative in the party discipline model and positive in the women’s rights model, suggesting that, if anything, women who have spent more time in office are less disciplined and more likely to list women’s rights as a top priority than are more-recently elected women. Although very tentative, these results suggest that disciplined and undisciplined women come into parliament with different preferences about women’s rights. This finding is consistent with the rich case-based literature that suggests that earlier cohorts of women MPs (particularly in postconflict settings) were both less disciplined and more likely to be outspoken feminists than were more recent cohorts of women MPs in African legislatures (Goetz and Hassim Reference Goetz and Hassim2003; Tripp Reference Tripp2015; Walsh Reference Walsh, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012).

An Illustrative Case: The Namibian National Assembly

To illustrate our main findings and further interrogate our proposed causal mechanisms, we supplement our quantitative results with a qualitative case study of the Namibian Parliament. Our analysis is based on over 20 elite interviews with MPs, parliamentary staff, members of civil society organizations (CSOs), and women’s rights activists conducted in late 2012 and summer 2017, as well as participant observation through an author’s (Clayton’s) affiliation with a prominent gender CSO in Windhoek, Namibia for five months during the 2012 field visit.

Namibia is a typical case in our sample of countries. It is an emerging but weak democracy with a longstanding hegemonic party. The country holds elections for its lower parliamentary house, the National Assembly, through a closed-list PR system with one nationwide list. Members of Namibia’s ruling party, Swapo, currently hold 63 of the 96 elected seats, and opposition parties are weak and fractionalized. At the behest of the Swapo party president, in July 2013, the party formally amended its party constitution to require a “zebra list” gender quota with men’s and women’s names listed in alternate order on its candidate list for the National Assembly. The quota was applied for the first time in the 2014 elections, and women’s representation jumped from 23.6% to 46.2% the following electoral term. With a near parity lower house, Namibia joined several other African nations as a world leader in women’s legislative representation.

Like other closed-list PR systems with high district magnitude, in the Namibian National Assembly a candidate’s fate is entirely reliant on where she is placed on the party’s list. While allegiance to party leadership affects both men and women MPs, our interviews suggest that women are particularly constrained through the two channels that we theorize above: (1) women must navigate gendered candidate selection procedures, making them more likely to be party loyalists, and (2) women are expected to conform to traditional gender roles once in parliament, including avoiding what might be perceived as assertive behavior. Finally, we find abundant evidence that expectations of party discipline constrain women’s ability to push for women’s rights reforms in parliament.

Because candidate selection in Namibia is highly centralized and district magnitude is high, the case is well suited for understanding the role of party gatekeepers in gendered patterns of candidate selection and recruitment.Footnote 15 Historically, Namibian women have had few pathways to legislative office available to them. The Swapo Party emerged from the political wing of the chief military organization that fought for independence from apartheid-ruled South Africa. Whereas the country is now on its third postindependence president, this office has always been held by a member of the Swapo “old guard,” men who fought in the initial liberation struggle. This old guard continues to dominate the party’s leadership. Of the ministers appointed between independence in 1990 and 2015, over half (56%) were former exiled liberation fighters (Melber, Kromrey, and Welz Reference Melber, Kromrey and Welz2016, Table 3).Footnote 16 Consistent with theories on the role of homosocial capital in candidate selection, men’s dominance in the Swapo Party leadership means that there are fewer political career paths open to women party members. One civil society leader notes how this allows men MPs more latitude to depart from the party line:

Women are more

![]() $ \Big[ $

likely to be

$ \Big[ $

likely to be

![]() $ \Big] $

party hacks because it’s harder for them to succeed in the party… . It is the men who are powerful in the party. So [they] have the confidence that their positions are safe [and] they are prepared to sometimes say something that is outside the party chapter-and-verse because they know they are secure in their positions.Footnote

17

$ \Big] $

party hacks because it’s harder for them to succeed in the party… . It is the men who are powerful in the party. So [they] have the confidence that their positions are safe [and] they are prepared to sometimes say something that is outside the party chapter-and-verse because they know they are secure in their positions.Footnote

17

Above we theorized that because women are often outside of male-dominated party networks, one way that women can advance in their parties is through their fealty to party leaders. On this point, a gender scholar at the University of Namibia recounted how women MPs often adopt strategies to align themselves with this influential cadre of male elites:

It is not a dumb strategy. It is just a strategy where she realizes that the men know how the system functions. [She thinks] it is good for me to align myself with men if I want my agenda to move forward.Footnote 18

A second theme that emerges from our interviews relates specifically to role congruity theory. Many interviewees noted how patriarchal attitudes still dominate Namibian politics and set expectations for the type of behavior that is acceptable from women parliamentarians. When asked to speculate why she thought women spoke less than men in parliamentary debates, a former Swapo MP replied,

You have to go through a party… . And how do women belong? For so long they were told not to participate… . Men see themselves as leaders of this country and that has taken away the ability of women to speak out and to be different.Footnote 19

Swapo’s new gender quota seems to have only exacerbated gendered expectations about proper behavior. As one parliamentary staffer noted (emphasis added),

Because of the change in the

![]() $ \Big[ $

Swapo Party

$ \Big[ $

Swapo Party

![]() $ \Big] $

constitution to accommodate more women MPs, the MPs think they are only there because of the party. If they turn to work against the party, then their job is on the line. That is the fear. Most of them are very quiet and they are just there for voting in the house. The quota did not change it… . Women don’t want to be seen as disruptive, rocking the boat.

Footnote

20

$ \Big] $

constitution to accommodate more women MPs, the MPs think they are only there because of the party. If they turn to work against the party, then their job is on the line. That is the fear. Most of them are very quiet and they are just there for voting in the house. The quota did not change it… . Women don’t want to be seen as disruptive, rocking the boat.

Footnote

20

Finally, the Namibian case lends insight to our finding that women MPs with higher levels of party discipline are less likely to list women’s rights as a top government priority. One consistent theme in our interviews was the sense that prominent women MPs in the ruling party owe their longevity to their unwavering support of the party’s policies. One civil society leader recalled how one of the most prominent women in Swapo would publicly tell women’s advocacy groups that she held no allegiance to them:

We were having a meeting, when

![]() $ \Big[ $

she

$ \Big[ $

she

![]() $ \Big] $

said, “People, I am in this position not because I am a woman. I am in this position, because Swapo put me here. And if I have to vote for anything if it is pro-women and anti-Swapo, I’m telling you openly, it is because of Swapo I am here, I will vote for Swapo.” She made it clear… . She said if it’s good for women and bad for Swapo, she’ll vote for Swapo… . And she’s done that. Whatever her reasons, she understands the situation.Footnote

21

$ \Big] $

said, “People, I am in this position not because I am a woman. I am in this position, because Swapo put me here. And if I have to vote for anything if it is pro-women and anti-Swapo, I’m telling you openly, it is because of Swapo I am here, I will vote for Swapo.” She made it clear… . She said if it’s good for women and bad for Swapo, she’ll vote for Swapo… . And she’s done that. Whatever her reasons, she understands the situation.Footnote

21

This sentiment seems to permeate Swapo rank-and-file women as well. Another interviewee relayed how Swapo women feel pressure to not depart from the party in any way:

Radicalism is something that is not appreciated. The word is still loyalty. You must be loyal… . And that is what we see. A woman will not advocate for a woman’s issue if it is not initiated from the leadership of the party. And the leadership of the party is still predominately male.Footnote 22

This sentiment was reinforced by women Swapo members themselves. When asked whether she would support an issue related to women’s rights if it was not initiated by her party, a Swapo woman MP and deputy minister answered, “You need to follow the principle of the party. It is not what you want—it is what the party is telling you to do. You cannot go outside the principle of the party.”Footnote 23

In sum, despite having one of the highest rates of women’s parliamentary representation in the world, one of the few ways for women to advance in the ruling party is to take on the legislative style of the party loyalist. Once elected, this tendency is exacerbated by gendered expectations about proper behavior, which limits the ability of women MPs to adopt a more assertive legislative style. Finally, a tendency towards party loyalty makes it unlikely that ruling party women will take a strong stance on women’s rights issues that are not sanctioned by party elites.

Party Discipline and Women’s Representation in Emerging Party Systems

Our analyses provide a clear and consistent finding: women exhibit higher levels of party discipline than do their men copartisans. We have theorized that this relationship is the result of gendered pathways to power and of gendered expectations about proper behavior while in office. While we do not exhaustively test which of these mechanisms explains the observed gender gap, we find robust evidence consistent with the former and some (weaker) evidence consistent with latter. Our fieldwork from the Namibian Parliament further suggests that both mechanisms are at play.

Our results have somewhat ambiguous implications for democratic consolidation on the continent. Most work on legislative development in long-standing democracies theorizes that party discipline leads to more cohesive political parties and builds legislative strength (see e.g., Bowler, Farrell, and Katz Reference Bowler, Farrell and Katz1999). Also in African legislatures, we find similar claims. In his volume on legislative power in emerging African democracies, Barkan (Reference Barkan2009, 8) observes that “[W]hen members focus overwhelmingly on constituency service, the legislature exists in name only—a conglomerate of elected representatives from separate constituencies that rarely acts as a whole.” In this sense, party discipline might be seen as a marker of legislative development. Commenting on the experience of the Beninese Parliament, Adamolekun and Laleye (Reference Adamolekun, Laleye and Barkan2009, 116) explicitly make this claim, noting, “The weakness of the party system has contributed significantly to the slow pace of strengthening the legislature in Benin.”

Yet, at the same time, high levels of party discipline, particularly by members of the ruling party, may signal a movement away from legislative autonomy if legislators feel excessively beholden to the executive branch (Longman Reference Longman, Britton and Bauer2006). Indeed, while not our focus here, we observe that average MP party discipline tends to be higher in less democratic cases in our dataset (see SI § 5), suggesting that party discipline is associated with creeping authoritarianism. It may also be the case that party discipline operates differently in strong versus weak legislatures, shoring up democratic consolidation in the former (particularly as expressed by opposition members) and weakening democracy in the latter (particularly as expressed by ruling party members) (see Opalo Reference Opalo2019).

We also find evidence that women MPs with high levels of discipline are unlikely to use their parliamentary platforms to push for women’s rights in ways that fundamentally challenge party doctrine. Our results thus suggest caution to any expectation that women will necessarily be able to use their new positions in ways that challenge patriarchal institutions, particularly once opportunity structures that may have opened during times of postconflict reconstruction begin to close (see Tripp Reference Tripp2015). However, at the same time, our findings also suggest that women’s presence does increase the degree to which legislators prioritize women’s rights in the aggregate. Whereas more disciplined women are less likely to list women’s rights as a top priority than more independent women, in general women still tend to prioritize women’s right more than do men. It is only the most disciplined women that are as unlikely to prioritize women’s rights to the same degree that we observe among (all) men. Methodologically, we do not know the counterfactual: what would women’s influence be if they entered parliaments similarly unconstrained as men? In such instances, we likely would observe even more fully realized women’s rights lobbies in national parliaments.

Our work focuses on one potential form of substantive representation: women MPs who both advocate for women’s rights and exert independence from their parties. Yet, women’s substantive representation can take many additional forms (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008). Perhaps most intuitively, women may try to work within their political parties in order to advocate for the revision of a specific party position. Additionally, women MPs may push for women’s rights by putting new issues on the legislative agenda for which their parties do not yet have a fixed position (Greene and O’Brien Reference Greene and O’Brien2016). In these ways, women can try to shape policy without having to rebel. Additionally, by collaborating across parties through women’s parliamentary caucuses, women can advocate for women’s rights reforms collectively, which may shield individual women from repercussions instigated by party leaders (Johnson and Josefsson Reference Johnson and Josefsson2016).

Our focus has been on women’s rights writ large, but within this domain there are many different types of issues. Whereas party loyalist women may be unlikely to push for issues that fundamentally challenge patriarchal power, they may instead advocate for reforms that increase women’s welfare while still upholding traditional gender roles. For example, Ugandan women parliamentarians collectively ran a highly visible and effective effort to increase funding for maternal health, whereas legislation that equalizes women’s rights in marriage and divorce and on land inheritance have either languished in parliament or been vetoed by the executive branch (Kawamara-Mishambi and Ovonji-Odida Reference Kawamara-Mishambi, Ovonji-Odida, Goetz and Hassim2003; Wang Reference Wang2013). Future work might systematically explore the adaptive strategies that women MPs use to substantively represent women’s interests in settings where they are constrained by expectations of party discipline.

Our work has many additional extensions. First, an outstanding question of our analysis is how country-level variables, such as electoral systems or the degree of democratic consolidation, condition the emergence and size of gender gaps in party discipline. Consistent with our findings here, most work from established democracies tends to suggest that women are more party loyal than are men but that the size of these gender differences might vary both within and across countries. Such variation may be attributed to the presence of our proposed mechanisms across cases. For instance, the role of homosocial capital in gendered recruitment patterns and gendered expectations about parliamentary behavior likely exist to some degree across parliaments, while the degree of clientelism in organizing political competition is likely more variable. A second and related extension is to better understand predictors of rebellion among women MPs. Not all women are more party loyal than men, and further analysis may shed light on why and when some women choose to rebel. By exploring these questions, it is possible to build a comparative research agenda on gender differences in party discipline and, more broadly, to better understand the gendered nature of legislative institutions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000368.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication files are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WQ1R5X.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

The authors are especially grateful to Robert Mattes and Shaheen Mozaffar for encouraging us to use the ALP data to examine gender differences in legislative behavior. We also thank Juan Manuel Pérez for exceptional research assistance. For invaluable feedback on the project, we thank panel participants at the 2017 APSA Conference, the 2019 European Conference on Politics and Gender (ECPG), and the Political Parties in Africa Conference, as well as seminar participants at Washington University, Oxford University, and the London School of Economics. We also thank Kendall Funk, Tumi Makgetla, Robert Mattes, Mona Morgan-Collins, Malu Gatto, Ana Catalano Weeks, Tessa Ditonto, four anonymous reviewers, and the editors of the American Political Science Review for enormously helpful comments and suggestions. The field research in Namibia would not have been possible without support from the Legal Assistance Centres Gender Research and Advocacy Project in Windhoek, Namibia, and in particular generous support from Dianne Hubbard. In Namibia, we are also grateful for the time and insights from Chippa Tjirera, Rosa Namises, Elma Dienda, Liz Frank, Immaculate Mogotsi, Max Weylandtt, and Nangula Shejavali. Please direct correspondence pertaining to this article to Amanda Clayton: amanda.clayton@vanderbilt.edu.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Amanda Clayton received support for this research from the American Association of University Women (AAUW) and the Vanderbilt Department of Political Science. Pär Zetterberg received financial support for this research from the Swedish Research Council (no. 201705640). Further information on funding for the ALP survey can be found in the Supporting Information.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the University of Washington and certificate numbers are provided in the appendix. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.