Article contents

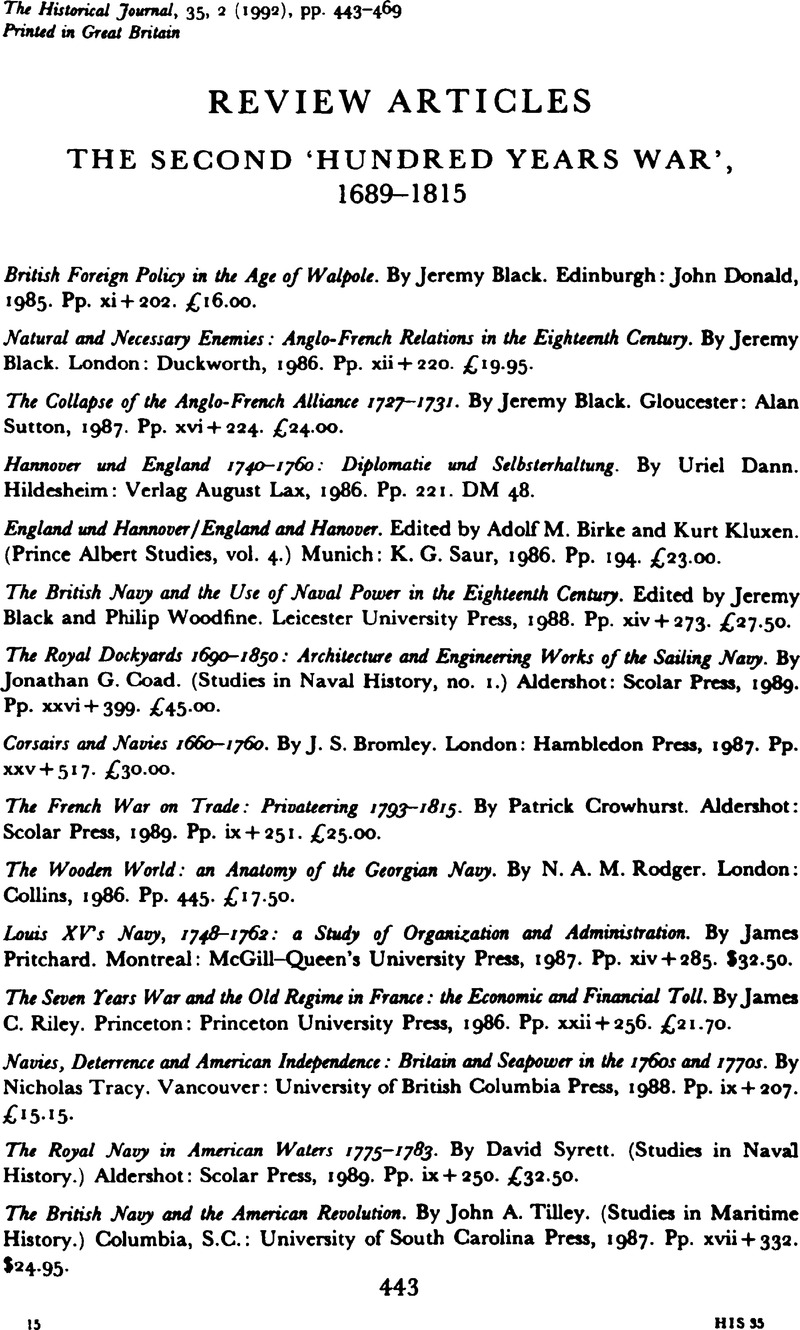

The Second ‘Hundred Years War’, 1689–1815

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 March 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Review articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1992

References

1 For this quotation and its correct attribution see Blanning, T. C. W., ‘Frederick the Great andenlightened absolutism’, in Scott, H. M., ed.,Enlightened absolutism: reform and reformers in later eighteenth-century Europe (London, 1990), p. 270 and n. 24, p. 368Google Scholar.

2 The precise figure would depend on what is defined as a ‘war’. England's principal wars during this period were: (1) the Nine Years War (1689–97); (2) the Warof the Spanish Succession (1701/2–1713/14); (3) the Anglo-Spanish War/War of the Austrian Succession (1739/40–1748); (4) the Seven Years War (1756–63); (5) the War for America (1775–83); (6) the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France (1793–1815).

3 English society 1688–1832 (Cambridge, 1985). This point was previously made byGoogle ScholarInnes, Joanna, ‘Jonathan Clark, social history and England's “Ancien Régime”’, Past and Present, cxv (05, 1987), esp. pp. 197–199Google Scholar.

4 (London, 1967.)

5 (London, 1989.)

6 See also his important article: ‘The English state and fiscal appropriation, 1688–1789’, Politics and Society, XVI (1988), 335–85. Simultaneously,Google ScholarJones, D. W. published a major study of War and economy in the age of William III and Marlborough (Oxford, 1988)Google Scholar.

7 Brewer, , Sinews of power, p. 29Google Scholar.

8 See now: Black, Jeremy, A system of ambition?: British foreign policy 1660–1733 (London, 1991)Google Scholar.

9 His view is concisely set out in ‘Foreign policy in the age of Walpole’, in Black, j., ed., Britain in tht age of Walpole (London, 1984), pp. 145–69CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

10 British foreign policy in the age of Walpole, p. v.

11 These years were most authoritatively examined in the vintage study of Wilson, Arthur McCandless, Frenchforeign polity during the administration of Cardinal Fleury 1726–1743 (Cambridge, Mass., 1936), a book whose value Dr Black is inclined to belittleCrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12 ‘The Anglo-French alliance 1716–31’ in Coville, A. and Temperley, H., eds., Studies in Anglo-French history (Cambridge, 1935), p. 17Google Scholar.

13 British foreign policy in the age of Walpole, pp. 76, 166; The collapse of the Anglo-French alliance, P.93.

14 See, in particular: ‘Parliament and foreign policy in the age of Stanhope and Walpole’, English Historical Review, LXXVII (1962),18–37;CrossRefGoogle Scholar‘The revolution in foreign policy’, in Holmes, G., ed., Britain after the Glorious Revolution (London, 1969)Google Scholar; ‘Newspapers, parliament and foreign in the age of Stanhope and Walpole’, Mélanges offerts à G. Jacquemyns (Brussels, 1968)Google Scholar; ‘parliment and the treaty of quadruple alliance’, in Hatton, R. and Bromley, J. S., eds., William HI and Louis XIV (Liverpool, 1968)Google Scholar; and ‘Britain and the alliance of Hanover, April 1725-Febniary 1726’, English Historical Review, LXXIII (1958)Google Scholar.

15 British foreign policy in the age of Walpole, pp. 89–92.

16 ‘Laying treaties before Parliament in the eighteenth century’, in Hatton, R. and Anderson, M. S., eds.. Studies in diplomatic history: essay in memory of David Baynt Horn (London, 1970), pp. 116–37; cf.Google ScholarBlack, , Natural and necessary enemies, pp. 97–8, and British foreign policy in the age of Walpole, pp. 75–92.Google Scholar

17 The British Navy and the use of naval potver in the eighteenth century, eds. Black, J. and Woodfine, P. (Leicester, 1988), p. 21Google Scholar.

18 ‘Naval power and British foreign policy in the age of Pitt the Elder’, in The British navy and tht use of naval power, eds. Woodfine, Black and, pp. 100–3Google Scholar.

19 See Doran, P. F., Andrew Mitchell and Anglo-Prussian diplomatic relations during the Seven years War (New York, 1986)Google Scholar.

20 The fullest study is Margaret M. Escott, ‘Britain's relations with France and Spain, 1763–1771’ (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Wales, 1988), p. 517 and passim; cf.Google ScholarThomas, P. D. G., The Townsshend duties crisis: the second phase of the American revolution 1767–1773 (Oxford, 1987), pp. 16–17, for a similar conclusion in respect of American policyGoogle Scholar.

21 See ‘The tory view of eighteenth-century British foreign policy’, The Historical Journal, XXXI (1988), 469–77.Google Scholar

22 The Duke of Newcastle (New Haven, 1975).Google Scholar

23 E.g. Natural and necessary enemies, pp. 52, 54 and passim.

24 Hatton, R., The Anglo-Hanoverian connection 1714–1760 (London, 1982)Google Scholar; Blanning, T. C. W., ‘“That horrid Electorate” or “Ma patric germanique”?: George III, Hanover and the Furstenbund of 1785’, The Historical Journal, xx (1977), 311–44CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

25 Hanover and Britain 1740–60 (Leicester Univenrity Press, 1991)Google Scholar.

26 E.g. Duffy's, Michael model study of Soldiers, sugar and seapower: the British expeditions to the West Indies and the war against revolutionary France (Oxford, 1987), orGoogle ScholarSchroedcr's, Paul W.article on ‘The collapse of the second coalition’, Journal 0f Modern History, LIX (1987), 244–90CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

27 See now Harding, Richard, Amphibious warfare in the eighteenth century: the British expedition to West Indies 1740–1742 (Woodbridge, 1991)Google Scholar.

28 The War for America 1775–1783 (London, 1964)Google Scholar; Statesmen at war: the strategy 0f overthrow, 1798–1799 (Oxford, 1974)Google Scholar; War without victory: the downfall 0f Pitt 1799–1802 (Oxford, 1984); andGoogle ScholarThe war in the Mediterranean 1803–10 (London, 1957)Google Scholar.

29 For convenient introductions see Crowl, P. A., ‘Alfred Thayer Mahan: the naval historian’, in Paret, P., ed., Makers of modern strategyfrom Machiavelli to the nuclear age (2nd edn, Princeton, N.J., 1986), pp. 444–77, and the special issue ofGoogle ScholarThe International History Review, x:I (1988), ‘On sea power’, and especially the contributions byGoogle ScholarKennedy, Paul, ‘The influence and the limitations of sea power’, and by Daniel A. Baugh, ‘Great Britain's “Blue-Water” policy, 1689–1815’ (respectively pp. 2–17Google Scholar and 33–58). Guilmartin, J. F. Jr, Gunpowder and galleys: changing technology and Mediterranean warfare at sea in the sixteenth century (Cambridge, 1974), pp. 16–41, provides a sprightly discussion of ‘The Mahanians' fallacy’ in the context of sixteenth-century Mediterranean warfare.Google Scholar

30 1st edition, Boston, 1890.

31 Forests and sea power (Cambridge, Mass., 1926)Google Scholar.

32 The Navy in the war of William III (1689–1697) (Cambridge, 1953).Google Scholar

33 (Princeton, 1965.)

34 Baugh, Daniel A., ed., Naval administration 1715–30 (‘Navy Records Society’, vol. 120; London, 1977)Google Scholar.

35 See, e.g. N. A. M. Rodger, The wooden world: an anatomy of the Georgian navy (London, 1986), 413.

36 Les Marines de Guerre Européennes XVIIe–XVIIIf sièles, eds. Acerra, Martinc, Merino, José and Meyer, Jean (Paris, 1985), is an especially important collection of conference proceedings and contains the raw material for some significant comparisons of naval powerGoogle Scholar.

37 The two most important of Dr Knight's articles are: ‘The building and maintenance of the British fleetduring the Anglo-French Wars (1688–1815)’ in Les Marines dt Guerre Europiéimes, eds. Acerra, et al., pp. 35–50;Google Scholar‘The performance of the royal dockyards in England during the American War of Independence’, Proceedings of the 14th Conference of the International Commission for Maritime History (London, 1974)Google Scholar; Morriss, R., The royal dockyards during the revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (Leicester, 1983)Google Scholar.

38 A conclusion endorsed By Webb, Paul, ‘Construction, repair and maintenance in the battle fleet of the Royal Navy, 1793–1815’, inGoogle ScholarBlack, and Woodfine, , eds., The British navy, 218Google Scholar.

39 This, too, is a misconception, laid to rest by Symcox, Geoffrey in his fine study of The crisis of French sea power 1688–1697: from the Guerre d'Escadre to the Guerre de Course (The Hague, 1974)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

40 The manning of the Royal Navy: selected public pamphlets, 1693–1873 (Navy Records Society, vol. 119, London, 1974)Google Scholar.

41 Notably in his War and trade in the West Indies 1739–63 (Oxford, 1936) and inGoogle ScholarColonial blockade and neutral rights 1739–1763 (Oxford, 1938)Google Scholar.

42 Especially in his The Dutch alliance and the war against French trade 1688–1697 (Manchester, 1923)Google Scholar.

43 Two of the best such studies are Gwyn, Julian, The enterprising Admiral: the personal fortune 0f Admiral Sir Peter Warren (Montreal, 1974), andGoogle ScholarMackay, R. F., Admiral Hawke (Oxford, 1965)Google Scholar.

44 The manning of the British navy during tht Seven Tears' War (London, 1980)Google Scholar.

45 (Cambridge, 1985.)

46 Corbett, J. S., England in the Seven years' War: a study in combined strategy (2vols., London, 1907)Google Scholar; Williams, B., The life of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham (2 vols., London, 1913)Google Scholar.

47 Tunstall, B., William Pitt, earl of Chatham (London, 1938)Google Scholar; Pares, R., ‘American versus continental warfare 1739–63’, English Historical Review, II (1936), 429–65CrossRefGoogle Scholar, reprinted in The historian's business and other essays (Oxford, 1961), pp. 130–72; idem, War and trade in the West Indies, 1739–63 (Oxford, 1936).

48 Browning, , Newcastle; Reed Browning, ‘The duke of Newcastle and the financing of the Seven Years War’, Journal of Economic History, XXXI (1971), 344–77CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

49 See also his earlier article, ‘Pitt, , Anson and the Admiralty, 1756–1761’, History, LV (1970), 189–98Google Scholar.

50 Above all from Richard Waddington's great work. La gutrrt de Sept Ans (5 vols., Paris, 1894–1907) or the even olderGoogle ScholarPajol, C. P. V., Les guerrts sous Louis XV (7 vols., Paris, 1881–1891). Waddington's work remained unfinished and was in some measure completed byGoogle ScholarRashed, Z. E., The peace of Paris 1763 (Liverpool, 1951). Two useful studies appeared in the 1960s:Google ScholarOliva, L. Jay, Misalliance: a study of French policy in Russia during the Seven years' War (New York, 1964)Google Scholar and Kennett, Lee, The French armies in the Seven years' War: a study in military organisation and administration (Durham, N.C., 1967).Google Scholar

51 See also his important article, ‘French finances, 1727–1768’, Journal of Modern History, LIx (1987), 209–43Google Scholar.

52 This emergesfrom Dickson's, p. G. M. great work Finance and government under Maria 1740–1780 (2 vols., Oxford, 1987)Google Scholar.

53 Navarro, José P. Merino, La Armada española en el siglo XVIII (Madrid, 1981) is an important detailed study of the Spanish navy.Google Scholar

54 ‘British assessments of French and Spanish naval reconstruction, 1763–68’, The Mariner's Mirror, LXI (1975), 73–85; ‘The administration of the duke of Grafton and the French invasion of Corsica’,Google ScholarEighteenth-century Studies, VIII (1974–1975), 169–82;Google Scholar‘The gunboat diplomacy of government of George Grenville, 1764–65’, The Historical Journal, XVII (1974), 711–31; ‘The Falkland Islands crisis of 1770: use of naval force’,Google ScholarEnglish Historical Review, xc (1975), 40–75CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

55 The French navy and American independence: a study of arms and diplomacy 1774–1787 (Princeton, 1975)Google Scholar.

56 See especially his Shipping and the American war 1775–83 (London, 1970)Google Scholar.

57 The wooden world, esp. pp. 323–7.

58 See, e.g. Langford, Paul, A polite and commercial People: England 1727–1783 (Oxford, 1989), pp. 320–3, 617; cf.Google ScholarWilson, Kathleen, ‘Admiral Vernon and popular politics in mid-Hanoverian Britain’, Past and Present, CXXI (11, 1988), 74–109, for a remarkable study of the later popularity, and the use made of, the admiral who captured Porto Bello at the beginning of the Anglo-Spanish war in 1739CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

59 See, e.g. Dinwiddy, J. R., ‘England’, in Otto Dann and Dinwiddy, J. R., eds., Nationalism in the age 0f the French revolution (London, 1988), pp. 53–70, esp. p. 54Google Scholar.

60 There are some stimulating comments in two articles by Linda Collcy, ‘The apotheosis of George III: loyalty, royalty and the British nation 1760–1820’, Past and Present, CII (02, 1984), 94–129Google Scholar, and ‘Whose nation? Class and national consciousness in Britain 1750–1830’, ibid, cxiii (November, 1986), 97–117.

61 In a broadside entitled The alarm: quoted by Dinwiddy, p. 62.

- 6

- Cited by