Book contents

- Cicero

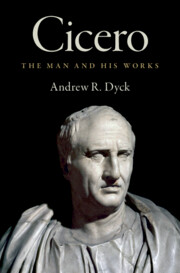

- Cicero

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- A Note on Sources

- Chapter 1 An Orator’s Education (106–80)

- Chapter 2 Orator 2.0 (79–71)

- Chapter 3 The “Reluctant” Prosecutor (70)

- Chapter 4 A “New Man” Rising (69–64)

- Chapter 5 Piloting the Ship of State on an Optimate Course (January–August 63)

- Chapter 6 Crisis Management (September–December 63)

- Chapter 7 The Aftermath of the “Annus Mirabilis” (62)

- Chapter 8 Seeking Shelter in the Past as Storm Clouds Gather (61–59)

- Chapter 9 To the Abyss and Back (58 to Early September 57)

- Chapter 10 Resurgence and Deflation (September 29, 57, to the End of April 56)

- Chapter 11 Strategies for Coping (May 56 to the End of 54)

- Chapter 12 Political Realities, Theoretical Constructs (The End of 54 to Mid-51)

- Chapter 13 Away from Rome (Mid-51–47)

- Chapter 14 Reclaiming a Voice (46)

- Chapter 15 Devastation and Recovery (January to Mid-45)

- Chapter 16 From Theory to Practice (Mid-45 through March 44)

- Chapter 17 A New Struggle Looms (April–December 44)

- Chapter 18 The Final Struggle (43)

- Chapter 19 Conclusion: An Intellectual between Tradition and Power

- Appendices

- References

- Index of Greek Words and Phrases

- Index of Latin Words and Phrases

- Index of Passages Discussed

- Index of Cicero’s Works Discussed

- Subject Index

- Index of Proper Names

- References

- Cicero

- Cicero

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- A Note on Sources

- Chapter 1 An Orator’s Education (106–80)

- Chapter 2 Orator 2.0 (79–71)

- Chapter 3 The “Reluctant” Prosecutor (70)

- Chapter 4 A “New Man” Rising (69–64)

- Chapter 5 Piloting the Ship of State on an Optimate Course (January–August 63)

- Chapter 6 Crisis Management (September–December 63)

- Chapter 7 The Aftermath of the “Annus Mirabilis” (62)

- Chapter 8 Seeking Shelter in the Past as Storm Clouds Gather (61–59)

- Chapter 9 To the Abyss and Back (58 to Early September 57)

- Chapter 10 Resurgence and Deflation (September 29, 57, to the End of April 56)

- Chapter 11 Strategies for Coping (May 56 to the End of 54)

- Chapter 12 Political Realities, Theoretical Constructs (The End of 54 to Mid-51)

- Chapter 13 Away from Rome (Mid-51–47)

- Chapter 14 Reclaiming a Voice (46)

- Chapter 15 Devastation and Recovery (January to Mid-45)

- Chapter 16 From Theory to Practice (Mid-45 through March 44)

- Chapter 17 A New Struggle Looms (April–December 44)

- Chapter 18 The Final Struggle (43)

- Chapter 19 Conclusion: An Intellectual between Tradition and Power

- Appendices

- References

- Index of Greek Words and Phrases

- Index of Latin Words and Phrases

- Index of Passages Discussed

- Index of Cicero’s Works Discussed

- Subject Index

- Index of Proper Names

- References

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- CiceroThe Man and His Works, pp. 915 - 1030Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2025