I. Introduction

After decades of instability in Liberia, the Accra Peace Accords brought an end to civil conflict in August 2003. Liberia’s postwar transitional government faced enormous challenges and several postwar assessments revealed the arduous task ahead for strengthening access to justice and the rule of law. An evaluation of the justice sector by the International Legal Assistance Consortium, in 2003, revealed “an almost unanimous distrust of Liberia’s courts, and a corresponding collapse in the rule of law.”Footnote 1 A 2006 report by the International Crisis Group (ICG) found institutional dysfunction and serious infrastructure constraints in the justice sector in particular; more than half of the justices of the peace, the lowest level of the statutory legal system, were estimated to be illiterate. Of the 130 Magistrate’s Judges identified by ICG, only three were trained as lawyers.Footnote 2 Nearly all formal court buildings were destroyed during the conflict. With this baseline, the Government of Liberia and its international partners began the task of supporting the emergence of accountable and representative public institutions.

Much of the post-conflict development in the justice sector concentrated on formal institutions. Western donors and the Liberian elite, who predominantly managed these reforms, set about reconstructing a formal justice system modeled largely on the United States. As these efforts were ongoing, however, a smaller set of Liberian civil society activists, Western donors, and Liberian government officials embraced community-based paralegals as a complementary, and at times alternative, model of legal development. These non-lawyer paralegals came to be a front line of legal assistance for many Liberians.

The cases of Hauwa, a rural Liberian mother of four children, and of a community in River Gee County are illustrative of the diverse roles community paralegals play in Liberia.Footnote 3 When Hauwa’s husband stopped supporting his children, she found herself unable to cover the cost of living. Hauwa considered taking her partner to court to compel him to support his children, but with uncertainty about her legal position and the fear of high court fees, Hauwa instead approached a paralegal from a Liberian civil society organization, the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission (JPC). The community paralegal counseled Hauwa and began by describing the options available to her under Liberia’s dual legal framework, from pursuing a case in court, mediation by a civil society organization, to appealing to traditional leadership. Hauwa weighed these options and eventually asked the paralegal to mediate between her and her husband. The paralegal explained to Hauwa’s partner his legal responsibilities concerning child support and the seriousness of a charge of “persistent non-support” under the Domestic Relations Law and Penal Law. With this information, and with the engagement of the JPC paralegal, the husband agreed to resume support for his children and Hauwa received the support she needed: Hauwa reports that her husband now provides “food [and] the children are going to school.”Footnote 4 Her life and the lives of her four children changed for the better.

In a community in River Gee County, the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI), another Liberian civil society organization, trained two community members as paralegals (called “community animators”). These animators were trained to help strengthen the community’s governance of its land and natural resources, document property boundaries, and assist with pursuing formal registration of the community’s land with the Land Commission. The community paralegals worked with existing community leadership as well as other community members to develop and refine bylaws for governing land and natural resources. Each step of the way the paralegals worked to ensure widespread participation, including of vulnerable groups within the community, through mobilization and outreach.Footnote 5 Over time, and with the paralegals’ assistance, the community advanced through multiple revisions of the community bylaws with the regulations becoming more inclusive of different community members. One community member reported real change in the way decisions are made: “In the past elders and our big people made all the decisions. Now we call meetings for everyone to take part.”Footnote 6

This chapter describes and analyzes the use of community-based paralegals in post-conflict Liberia. This chapter begins by discussing the Liberian justice system, then reviews paralegal models in Liberia, particularly the approach of JPC, and finally uses a recent working paper to analyze the impact of JPC paralegals across three domains: rights consciousness, private disputes, and state or corporate accountability cases.Footnote 7 The conclusion discusses the determinants of success and the future of the paralegal movement in Liberia.

II. Liberia’s Justice System

Following the conflict, as Liberian and international policymakers began to address the severe capacity and infrastructure constraints throughout Liberia, Liberia’s dual justice system posed a particular paradox.Footnote 8 The origins of Liberia’s legal dualism trace back to the founding of the modern Liberian state. The Liberian state was founded by freed American slaves who, with the support of the American Colonization Society, “returned” to a part of Africa from which few had originally come. As the new government of Liberia began to consolidate power, first in Monrovia and then outside of the capital in what came to be known as the “hinterland,” it established a dual legal system whereby a settler elite were deemed “civilized” and subject to Western law, whereas “uncivilized natives” were subject to customary law. Natives could not use the Western system and, similarly, chiefs could not preside over disputes that included a civilized party.Footnote 9

This dual approach was further refined and institutionalized in 1949 through the Rules and Regulations Governing the Hinterland of Liberia (the “Hinterland Regulations”).Footnote 10 The Hinterland Regulations, as in the British colonial administration next door in Sierra Leone, reinforced a codified system of indirect rule over rural Liberia, grounded in the legal dualism harnessed by governing elites in many colonial states.Footnote 11 The Hinterland Regulations sanctioned the executive branch of government, through the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) rather than an independent judiciary, to have general oversight over a nationwide system of dispute resolution managed by government-recognized chiefs. Under this system, dispute resolution was not required to comply with principles of due process or equal protection codified under the Liberian constitution. The MIA could license ordeal doctors who could use trial by ordealFootnote 12 “of a minor nature and which do not endanger the life of the individual” to ascertain the guilt of parties.Footnote 13 Cases in this chieftaincy system would be appealed to the president of Liberia, not the Supreme Court. This system of governance and dispute resolution was valuable in extending state control over rural areas while simultaneously avoiding the need for a large government footprint outside Monrovia.

The dual system of dispute resolution and governance helped to promote the government’s core pursuit of extractive economic development. The government advanced a strategy of enclave investment that enriched a small elite. Private corporations and individuals were encouraged to lease large tracts of state “public land.” Indeed, by the 1960s, one-fourth of Liberia’s total land area was under concession, including rubber, iron, and timber.Footnote 14 The settler-dominated government closely guarded benefit flows. However, competing claims between private interests, public interests, and local communities were facilitated and exacerbated by the dual justice system. Competition over revenues and sharing of environmental and social costs was a major source of grievance. The 1980 coup d’état by indigenous military officer Samuel Doe was motivated, at least in part, by a desire to gain control over the valuable resource rents the Monrovia government controlled. The Doe (1980–90) and the Taylor governments (1997–2003) both used land and resource access and revenues to solidify constituencies at the local and national levels. Such a policy did little to build institutional coherence and continued to maintain the historical system of indirect rule and parallel governance.Footnote 15

A. The Preeminence of Local Dispute Resolution

Despite the discriminatory history surrounding the codification of Liberia’s dual justice system, and years of civil conflict, local systems continue to serve as the dominant form of dispute resolution and are generally an accepted part of Liberian communities. The community-based or traditional system is made up of family heads, elders, a range of customary authorities, and officials in secret societies. Some of these institutions are recognized and codified by Liberian law; other elements are not. Many Liberians view these different local institutions – even after they were coopted and shaped by the dual system – as more accessible than the formal justice system and report that they are more directly responsive to their normative preferences. A US Institute of Peace (USIP) study in 2009 found that Liberians viewed physical accessibility, cost, comprehensibility (both in terms of languages used and terminology) and transparency as some of the most important features of a functional justice system.Footnote 16 The USIP study found that the chieftaincy system regulated by the MIA, while not without flaws, was largely seen to better respond to these preferences.

Average Liberians know much more about how to access community-based systems and are often unfamiliar with formal court processes. A 2011 national household survey found that 91 percent of respondents said they had little or no knowledge of the formal court system.Footnote 17

While customary systems are viewed as more accessible and locally relevant, they are also at times in conflict with human rights and the Liberian constitution. Vulnerable groups, including women, children, and those foreign to local communities (called “strangers” by Liberians), suffer through these systems. Indeed critics contend that customary forums are, in particular, susceptible to elite capture.Footnote 18 A University of California, Berkeley population-based survey from 2011 also elucidated widespread mistrust of the formal system; less than 20 percent of survey respondents who reported being victims of a crime said they reported it to the police. Of the 19 percent who reported the crimes, more than half reported paying for the service.Footnote 19 Another survey found that 43 percent of respondents believe the Liberian National Police (LNP) is corrupt, 40 percent of respondents believe courts are corrupt, and nearly two-thirds of respondents said that they believe they would have to pay for the police to investigate a crime.Footnote 20 One in four Liberians reported feeling unsafe or not very safe,Footnote 21 and nearly one in seven households had a member who was a victim of crime or violence.Footnote 22

The challenge for Liberian and international policymakers working in the justice sector in this immediate postwar period was to put aside preconceptions of what Liberian institutions should look like and try to find ways to provide immediate and effective means of dispute resolution for the multitude of grievances present in Liberian society – from large-scale land and resource conflict to petty crime or corruption. Paralegal organizations have sought to bridge this divide and lay a foundation for a more equitable justice system.

III. Building on Community Capacities with Community-Based Paralegals

Peace came to Liberia at the same time as a growing movement of community paralegals was gaining traction across Africa. The 2008 Commission on Legal Empowerment documented such programs in other developing and post-conflict countries – for example, Kenya, Malawi, and Sierra Leone. Drawing on inspiration from these experiences, a handful of individuals within the Liberian government, civil society, and international development organizations in Liberia began to explore the role non-lawyer, community paralegals might play in Liberia. These groups theorized that given weak state capacity, the historically discriminatory role justice institutions played in Liberia and the widespread distrust of state institutions paralegals might help expand rights consciousness and resolve disputes – both private disputes at the community level and disputes with government or corporate interests. Multiple paralegal models have subsequently emerged in Liberia over the past ten years. This section discusses several of these paralegal models before focusing on the JPC.

A. Prison Fellowship Liberia (PFL)

Prison Fellowship Liberia (PFL),Footnote 23 founded in 1989, uses paralegals to improve accountability in Liberian detention and correctional facilities. In Monrovia, Buchanan, and Gbarnga, PFL paralegals promote rights consciousness among detainees and prison staff and respond to specific allegations of abuse. Beginning in 2009, PFL began working in partnership with Open Society Foundations, JPC, and the American Bar Association to implement a project aimed at reducing prolonged pretrial detention at Monrovia Central Prison (MCP). The project supported efforts by the judiciary and the Ministry of Justice to establish a mechanism for regular review of detainee status. The Liberian government, in partnership with PFL and others, established the Magistrate’s Sitting Program, which consisted of rotational meetings of magisterial courts at MCP for preliminary examination. PFL paralegals played an important role in this project by working inside MCP, eventually with the support of the Ministry of Justice, to assist with organization, record management, and monitoring of prison conditions. PFL’s organization and monitoring component linked to attorneys from JPC who provided free legal assistance to detainees. PFL has sourced funding from a variety of sources, including international donors such as Prison Fellowship International, the East-West Management Institute, Open Society Foundations and UN agencies.

B. The Sustainable Development Institute (SDI)

The Sustainable Development Institute (SDI) is a Liberian civil society organization that works to improve natural resource governance.Footnote 24 Beginning in 2009, SDI partnered with the International Development Law Organization (IDLO),Footnote 25 and now Namati, to explore the use of paralegals, along with other approaches, in demarcating and securing community land. The joint effort focused on (1) advancing community land titling in accordance with procedures agreed upon with Liberia’s Land Commission; (2) improving understanding of the most effective modalities of supporting communities to pursue community land titling; and (3) developing and testing approaches to improve intra-community land and resource governance through these processes.Footnote 26

The SDI project tested four different levels of assistance: monthly legal education, paralegal assistance, direct assistance of lawyers and other technical professionals, and a control group that received only hard copies of relevant information. A core objective was to understand how to best support communities to establish intra-community mechanisms to protect the land rights of women and other vulnerable groups. In communities selected for paralegal support, SDI conducted monthly training sessions for community members over the course of fourteen months. These training sessions lasted approximately three hours and included advice from legal and technical professionals on subjects including the statutory provisions for community land titling, advice on the legal framework on customary tenure, practical techniques to document community land, how to engage relevant government authorities, and effective strategies to deliberate intra-community land administration and governance. In addition to this support from SDI, two community-based paralegals were elected in each selected community. These two community members elected to serve as paralegals – typically one man and one woman – received an intensive two-day introductory training and then had monthly meetings and trainings with SDI over the course of the project. While these paralegals were not formally certified by the government, they helped supervise and implement the community titling processes within their community on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis.Footnote 27

An evaluation of the SDI program revealed that the paralegal treatment group was most effective in helping communities meet the requirements of the community land documentation process. The study authors suggested that paralegals were effective in three areas:

The success of paralegal communities in completing the land registration process seems to suggest that paralegal assistance was flexible enough to ensure that communities took ownership over the registration process.Footnote 28

Paralegals seemed to be particularly effective in helping communities “navigate through intra-community tensions or obstacles that a full-services team of outside professionals may either inadequately address, fail to perceive, or accidentally exacerbate.”Footnote 29

The authors also contend that there were spillover effects associated with community-based paralegals. The control groups and education-only communities that bordered paralegal communities were more successful than similarly situated communities that did not border paralegal treatment areas, which led the authors to suggest that “well-trained and rigorously supervised paralegals may not only help their own communities, but may also have spillover impacts throughout the region in which they are based.”Footnote 30

C. Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC)

From 2006 to 2014, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) supported a paralegal program focused on resolving land disputes.Footnote 31 Through its Information, Counseling and Legal Assistance (ICLA) program, NRC paralegals used mediation and “facilitated negotiation” to resolve land disputes, particularly related to the “return and reintegration of refugees and internally displaced persons.Footnote 32 Over the course of this program, NRC paralegals resolved thousands of land dispute cases.

D. The Catholic Justice and Peace Commission (JPC)

Beginning in 2007, The Carter Center partnered with the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission (JPC) to implement a paralegal program in southeast Liberia. The JPC is one of the largest human rights organizations in Liberia and former executive directors of the organization have recently served as the solicitor general, minister of labor, minister of public works, and vice president of the Liberian Bar Association. JPC was founded in 1991 as an interfaith effort supported by the Catholic Church’s global network to promote social justice, human rights, and accountability in Liberia.Footnote 33

1. Establishment and Funding

The Carter Center has worked on access to justice issues in Liberia since 2006. In partnership with the Ministry of Justice, JPC and The Carter Center began by training ten paralegals to operate in five southeastern counties. This area continues to be plagued with some of Liberia’s worst development indicators, including poor access to basic services and information and extremely limited infrastructure. During the rainy season, whole counties are, at times, inaccessible by road from the Liberian capital.

The ten paralegals, initially called community legal advisors, were trained to provide practical advice and support to citizens and communities in resolving their justice issues. Building on this approach, in 2008 the UN Peacebuilding Fund, through the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, expanded the program into central Liberia. Over the years, additional donors have assisted the program including Humanity United, a California-based foundation, and the US Agency for International Development. The Carter Center has also regularly contributed institutional funding to bridge gaps between donor assistance cycles.

By 2013, the program supported forty-five paralegals in seven counties, including Montserrado containing the Liberian capital of Monrovia. The title of “paralegals” was eventually changed in 2012 due to concerns raised by members of the Liberian legal community over the ability of non-lawyers to provide legal advice (evidencing how narrowly the formal legal professional views the justice system), and paralegals are now known as community justice advisors (CJAs).Footnote 34 CJAs typically possess secondary school or college education and many are recruited from the counties in which they work.

2. JPC Organizational Structure and Management

Following the end of the civil conflict in Liberia, JPC extended a nationwide network of staff and volunteers. Unlike many organizations in Liberia that keep offices only in the capital, Monrovia, JPC has a decentralized structure with three regional offices supporting activities in counties across the country. In addition to staff and volunteers at these central offices, JPC maintains a network of parish-based committees at the county and district levels where local volunteers work on the organization’s human rights mission.

The JPC aims to support individuals and deliver justice for marginalized communities through a mixture of front-line paralegals, lead paralegals, JPC regional coordinators, attorneys, and Carter Center staff. Paralegals are based in offices throughout their counties and are recognizable from their JPC-branded vests, motorbikes, and offices. In each county, paralegals are supported and mentored by staff from various levels. At the county level, lead JPC CJA paralegals are responsible for regularly working directly with the other paralegals in the county, ranging from four to six paralegals per county.

Paralegals are backstopped by trained attorneys who assist them through regular training, mentoring, and case-specific assistance. Paralegals are tasked with helping clients navigate complicated legal and administrative issues that sometimes require additional legal assistance. Even what might seem to be a simple case at the community level invariably will confront complex power relationships. JPC is directed by a Liberian attorney in the national office. The Carter Center also provides support to the program through a senior Liberian councilor-at-law, based in the Monrovia office, Liberian attorneys based in the regional offices, and a network of program staff to assist with general program and financial management. The Carter Center has also employed several foreign-educated lawyers in management and capacity-building roles.

JPC uses several tools to document and track case progress, including a client agreement form, a case record form, and a case options log. The case record form is filled out in triplicate and regularly sent to the JPC regional office to be included in its case database. This information is transmitted to The Carter Center head office in Monrovia, which maintains a master database. This database is used to track outcomes across the program and to refine training and program designs.

Every six months, the JPC secretary at each regional office will select twenty cases for every paralegal. Ten of these case records are transferred to the lead paralegal at the county level, and ten case records are given to The Carter Center’s regional office. The lead paralegals and The Carter Center review all of the case materials with each paralegal to ensure that the case records are complete and to talk through the legal ramifications of the case and potential strategy. Attorneys also review paralegal case files at quarterly trainings to strategize about opportunities for resolution. There are also regular evaluations of specific cases, involving direct meetings with clients and affected parties.

3. Tools

CJAs employ a range of tools to assist clients, including education, negotiation, organization, advocacy, and mediation. Empowerment of clients is stressed across the program and paralegals are encouraged to strategize about how each tool can be deployed in a way that ensures client ownership, direction, and control.

In nearly all cases, CJA engagement begins by counseling the client or clients on the relevant legal provisions and principles of equity. CJAs are trained to present all options to the clients and encouraged to seek advice from the lawyers on staff to ensure the accuracy of information and provide context-specific, flexible solutions. In addition to the relevant legal standards, CJAs explain to the clients the various steps required through different courses of action and what the clients can expect. The clients control case decisions.

Beyond giving information, advocacy and mediation are two of the most commonly used paralegal tools. CJAs advocate with government and disputing parties to address issues of injustice. Across a variety of case types, CJAs regularly find themselves forced to confront abuses of power: a local magistrate detains someone for the invented charge of “eye rape”; a county official takes it upon himself to help mediate a divorce while insisting that he should keep the family’s small generator as his “fee”; a chief issues a crippling fine for violating an unknown village ordinance. In each of these cases, CJAs have advocated on behalf of the less powerful and vulnerable parties to ensure that injustices are remedied. Often through an implicit or nuanced threat of escalating the case to more senior authorities, CJAs help local clients combat abuses of authority and advocate for more equitable outcomes.

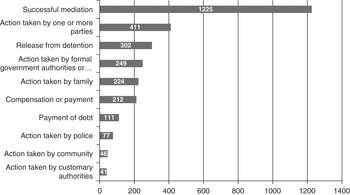

Mediation is one of the most commonly used tools employed by CJAs. CJAs are not an independent mediator, which you would find in some legal traditions; instead CJAs actively inform both parties about governing law, discuss principles of equity, and work for empowerment of the vulnerable and aggrieved party. In this sense, CJAs work toward a facilitated negotiation as opposed to a pure, impartial mediation. The program adopts this approach in an effort to even power asymmetries and promote more just and equitable outcomes. More than 40 percent of the CJA cases that have been “successfully resolved” (cases to which a resolution is found and the case is closed) since 2007 involved CJA mediation.

Figure 7.1 Successfully resolved cases: 2007–September 2012.

For JPC, a case is “successfully resolved” when its client can address a legal issue or dispute in accordance with the law and in a way that advances principles of fairness and equity. If a CJA is approached by an abusive spouse or partner asking advice on his or her rights, the CJA will provide information on what the law says and whether the individual is in violation of the law. The CJA would also seek to work with the other party to ensure that he or she is capable of exercising his or her rights. Where Liberian law itself is insufficient or discriminatory, JPC, The Carter Center, and partners will work toward reform.

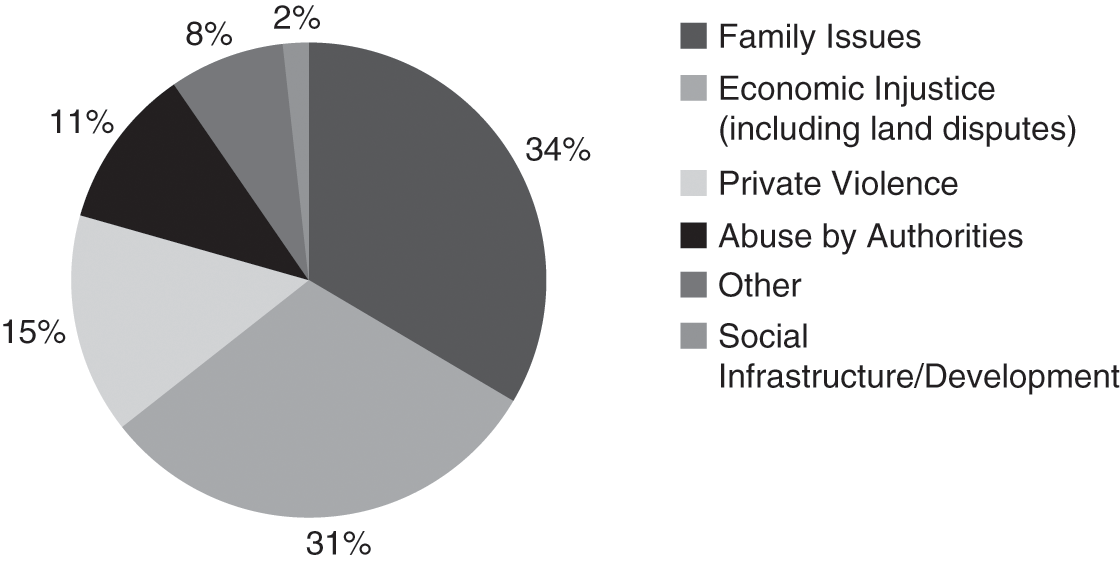

Over the years, CJAs have engaged in a wide variety of disputes. As indicated in Figure 7.2, CJAs regularly assist with family issues (34 percent of cases), economic injustice (31 percent of cases), private violence (15 percent of cases), abuse by authorities (11 percent of cases), and social infrastructure and development cases (2 percent of cases). Women bring approximately half of cases to the JPC, including 90 percent of child abandonment cases, 84 percent of domestic violence matters, and 81 percent of rape and sexual violence complaints.

Figure 7.2 Percentage of case type categories: 2007–September 2012.

IV. An Evaluation of the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission Program

Starting in 2008, The Carter Center and JPC agreed to work with researchers Justin Sandefur and Bilal Siddiqi to use a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the paralegal program. The study had two components, both of which are relevant to addressing the impact of community-based paralegals in Liberia: an initial household survey to document justice experiences of Liberians, and a specific focus on JPC’s model of paralegal assistance.

A. Forum Shopping and a Role for Community Paralegals

Sandefur and Siddiqi’s evaluation began with a household survey across more than 2,000 households spread across 176 communities in five Liberian counties. This survey identified, through self-reporting, some 4,500 separate disputes. Details were then collected for each dispute reported within the past year, covering the forums visited, time and costs incurred, and satisfaction with the outcome reported. Limited socioeconomic and demographic information was obtained about each disputant.

This initial analysis of household dispute data established a number of tendencies in the use of the forums that were of interest for the paralegal intervention. There was a clear tendency for violent crimes to be taken to the formal system (namely, justices of the peace, magistrates, police, and other military/government officials), while the civil cases that dominated the sample were likely to be taken to the customary system (including town, clan, and paramount chiefs, as well as elders, family leaders, and secret societies). The study found that the socially disadvantaged are on average significantly more likely to take their cases to the customary system.Footnote 35 The analysis concluded that, overall, the subjective satisfaction of this more “restorative” customary system, which is focused on redistributing loss from defendant to plaintiff, is far higher than that of the “punitive” formal, with a focus on remedies that “harm” defendants more than they benefit plaintiffs.Footnote 36

The discussion of the findings raises a core question leading Sandefur and Siddiqi to look at the role of legal assistance services in the Liberian context. The authors note the prima facie tension that exists between what appeared to be a documented bias in Liberian customary law against the less powerful party (women and marginalized), and the empirical fact that these disadvantaged plaintiffs choose to take most of their disputes to customary forums. They ask: “Why would marginalized groups choose to bring cases to customary courts that systematically repress them?”

A likely reason, as previously explored, is that despite the presence of bias, the formal justice system is viewed as more out of reach and even less responsive for many Liberians. Sandefur and Siddiqi suggest that the barriers to accessing justice through the formal system in Liberia are significant, ranging from prohibitive travel costs, to corrupt officials, to formidable formal legal procedures. The study posits that flexible, locally oriented legal assistance can offer the poor access to low-cost, remedial justice using quasi-formal alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, by way of pro bono mediation and advocacy services. These are the services provided by JPC’s community paralegal program.

B. Exploring the Impact of the CJAs

Within this institutional environment, the study sought to track the effects of paralegal services on clients through an evaluation launched in July 2011 that extended through December 2011. Paralegals conducted civic education sessions and then met with potential clients. Each client was surveyed and then randomly assigned to a treatment group, to be assisted with their dispute right away, and a control group, to receive assistance three months after first contact. The control group was encouraged in the meantime to pursue the matter using other available forums and resources, the vast majority of whom did. In November 2011, follow-up surveys were administered to the clients. The cases themselves spanned a wide range of cases and case types, from commercial debt disputes to marital infidelity.

The engagement and findings of the evaluation cover the three domains associated with the JPC program as well as the other chapters of this volume: rights consciousness, private disputes, and corporate accountability cases.

C. Rights Consciousness

The JPC CJA program focuses on improving community awareness through civic education and outreach as well as through handling cases, helping clients directly claim entitlements. In their work plan each month, CJAs are expected to expand awareness of rights in their communities. The Carter Center has historically supported additional local civil society organizations to conduct awareness sessions, often through drama and question and answer sessions designed to directly engage community members. These groups were encouraged to refer specific cases or disputes to the JPC CJAs for resolution.

The study found that treatment of a case by the community paralegal strongly impacted the legal knowledge of the respondents over the three months of interaction with the CJA. This included knowledge of such topics as women’s rights to inheritance, domestic violence, and corruption.Footnote 37

Such knowledge of how the system should work has real, individual impacts. In a small village outside of Fishtown, in the southeast, for example, an old woman was accused of being a “witch” after a young boy fell from a palm tree. Community members accused her of casting a spell that caused the child to fall, injuring him badly. Following the accusations, the old woman was beaten and jailed in the bathroom of the paramount chief’s house. After managing to escape she fled to town to find the county attorney, who acknowledged that the treatment was wrong, but was not confident in resolving such an issue where the “formal” and “local” laws conflicted. Recognizing the flexible services offered by the CJAs, the county attorney referred her to the JPC. The local CJAs contacted the county inspector, an MIA official who is often responsible for these types of “mysterious” cases, who accompanied them to the village. At first the townspeople threatened to expel the CJAs and the inspector, but the CJAs talked with the townspeople and the paramount chief and advocated on the woman’s behalf. The CJAs explained the necessary formal legal process if they believed the woman had caused someone harm. The community eventually agreed that there was no proof the woman had caused the child to fall from the tree and trust was built. Today the CJAs report that “the people who wanted to [expel] us are now bringing cases to us.”

The authors also found that the paralegal intervention positively impacted justice-seeking behavior: paralegal intervention “increases the number of reported disputes by providing an outlet for grievances that otherwise would have gone nowhere.”Footnote 38

D. Private Disputes

A predominance of CJA cases are private disputes. As indicated, between 2007 and 2012, approximately a third of all cases were family issues and another third were economic injustice cases. Women, who bring approximately half of cases to the JPC, account for 90 percent of child abandonment cases. Indeed, in the evaluation, a high proportion of cases concerned child support. These private disputes all cover areas where there is potentially significant impact on issues such as food security, economic well-being, and social cohesion.

The research found that CJA work improved household food security, child food security, and the proportion of households with single mothers receiving child support payments from absentee fathers. The study found that “clients were 22.8% more likely to receive child support payments, and reported large increases in household and child food security.”Footnote 39 This finding suggests that CJAs were playing an important role in securing child support and that these funds were translating directly into improved child and household food security.

Like the case of Hauwa, who we met in the introduction, the case of Nandi and her child illustrates the individual impact of the CJA intervention. Nandi and her partner, John, lived together in central Liberia and, in 2011, they had a child. Soon after the birth, John abandoned Nandi and his child, telling her to stop breastfeeding and not to ask him for any assistance. Nandi approached a JPC CJA for advice. The CJA helped Nandi understand John’s legal obligations – from child support to the implications of his demand for her to stop breastfeeding. Nandi was fearful of pursuing a remedy through Liberia’s court system and instead asked the CJA to assist with mediation. During this process John learned that if Nandi decided to take him to court, a judge might decide whether and how much he should provide to Nandi and their child. Nandi and John eventually agreed to terms of support, and the CJA drafted the agreement detailing a monthly payment of Liberian dollars as well as twenty-five kilograms of rice. The CJA monitored this agreement for three months to make sure the terms were being upheld, which they were. A year after this initial agreement a Carter Center staff member, as a component of their evaluation process, followed up with Nandi and found that John had not missed a monthly payment.

While the study was able to confirm that these client-level impacts positively affected child and household food security, the study did not find that the work of the CJAs impacted some of the other household well-being indicators that were measured, such as the amount of farming land and the incidence of gender-based violence.

E. State and Corporate Accountability

The Sandefur and Siddiqi study showed that clients who had seen paralegals improved their relationships with aggrieving parties and that there was a decrease in having to pay a bribe to a police officer or a public official, suggesting that paralegal involvement may lower the corruption costs of access to justice through the formal system.Footnote 40

Such cases are common challenges for many Liberians. One instance is a case of an elderly beverage seller in River Gee County who was left virtually penniless when someone stole 875 Liberian dollars from his backpack. The perpetrator was apprehended, taken to the police, and imprisoned by the local magistrate until he could pay back the money. Seeing the man soon free in the town, the beverage dealer was upset, and heard rumors that the magistrate had stolen the money repaid by the perpetrator’s family. The beverage seller called the CJA, and the CJA was able to assist his client in meeting with the magistrate – who had in fact wrongfully retained the money – recovering the old man’s savings, and extracting a public apology from the justice official. Without the CJA, the man likely would have had nowhere to turn to enforce his rights. Instead, this case provided an important example of accountability for the community.

Musu’s case presents another example of accountability and assistance in navigating the formal justice system: her life was almost destroyed by domestic violence when her boyfriend threw acid over her, burning her face and upper torso. The perpetrator was arrested and charged, but due to a lengthy pretrial wait and an incomplete case file, he was eventually released back into the community. Musu feared for her life and brought the case to the JPC. A CJA used her psychosocial skills to counsel Musu, explained how the criminal justice system operates, and assisted her in meeting with the county attorney and agreeing to act as a witness. Her former partner was re-apprehended and successfully convicted. Through the CJA’s assistance, Musu utilized the formal court system to obtain justice. Without the CJA’s intervention, the case would likely have been forgotten, Musu’s justice denied.

Overall, Sandefur and Siddiqi show that paralegals improved client satisfaction, fairness, perceptions of well-being, and relationships with other parties. The study concluded that legal empowerment interventions aimed at improving access to justice and bringing to life otherwise “dead letter” laws can produce large socioeconomic benefits.

V. The Determinants of Success

Paralegalism and legal empowerment programming in Liberia are at a crossroads. On the one hand, studies like Knight et al and Sandefur and Siddiqi’s have shown client-level impacts. Program evaluations of people engaging with the CJA program report satisfaction and positive experiences from engaging with paralegals. Evidence of institutional impacts is beginning to emerge as well. But the policy and fiscal environment has not seen a similar improvement over the past ten years. Paralegal programs in Liberia remain reliant on externally sourced donor funding, which is not surprising given Liberia’s current budget, but implicit and explicit reticence on the part of Liberia’s legal community is hampering longer-term sustainable impacts.

What makes for success in paralegal organizations in Liberia? There are both organizational and institutional factors.

A. Organizational Determinants

The effectiveness of paralegals in Liberia is significantly impacted by the organizational effectiveness of the managing organization. Within the JPC program, effective supervision and support of paralegals from both JPC and The Carter Center has proven critical in ensuring high-quality service delivery for clients. Liberia lacks infrastructure and travel between regions is challenging for many Liberians. JPC and The Carter Center’s program infrastructure and management play important roles in bridging this gap.

As the Liberian legal community opens space for paralegals to operate, managers of paralegal programs and Liberian policymakers should further professionalize paralegal services. While specific projects have implemented their own standards, with degrees of success, paralegals are emerging as a dedicated class of professionals who have the responsibility to provide accurate and accountable advice to communities and individuals. Here the government and academia can play an important role by strengthening the programmatic approach. There are numerous contexts where governments and universities work collaboratively and proactively with frontline civil society legal aid providers to expand access to practical legal advice and assistance. In South Africa, for example, there are university courses in paralegal studies, and law students working in law clinics partner with the community advice offices described elsewhere in this volume. As discussed in Chapter 6, a legal aid bill sets the parameters for paralegal engagement at the local level, including minimum standards and required training.

What might this look like in the Liberian context? A key goal should be to maintain the programmatic flexibility and independence of civil society justice programs while simultaneously ensuring they have the organizational support required for effective and accountable service delivery. Liberian paralegal organizations, and those supporting these efforts, should come together to establish minimum standards for training, supervision, and support. An umbrella association bringing together paralegal providers across sectors might help to promote learning, maintain quality across programs and strengthen the voice of paralegal organizations more generally.

B. Institutional Determinants

The institutional environment has significant impacts on the paralegal sector in Liberia. Mistrust from the legal community is particularly inhibiting. In part due to the influence of the Liberian legal establishment, the Liberian government has allocated neither fiscal nor political support to the majority of paralegal efforts. There has been some progress engaging various government commissions, including the Land and Governance Commissions, as well as in MCP, but central state agencies have historically been wary to support or institutionalize independent paralegals. While the international community has been supportive at times, much of the large-scale support to the justice system is directed to the highest levels of the state justice and security system. The budget for the UN Peacebuilding Fund’s “quick start” justice and security hub initiative, for example, prioritized infrastructure support and capacity building for formal sector personnel as opposed to community-based assistance.Footnote 41

Some in the Liberian legal and political establishment have, however, moved closer to embracing a role for non-lawyers in the justice system. Indeed, in 2008 it appeared as if paralegals and community-based justice programming might be incorporated into the legal framework. Discussion around the applicability of paralegals in Liberia intensified following a visit to Malawi by a delegation of senior members of the Liberian legal establishment. These officials visited the Malawian government and paralegal organizations to see how the programs worked in practice and to explore opportunities for similar programming in Liberia. The lessons from this trip played an important role in helping some members of the judiciary temper their resistance toward non-lawyers operating in the justice sector. Many of these officials now agree that paralegals and other non-lawyers have an important role to play in improving the accountability and efficiency of the justice system.

Following the Malawi trip, the Taskforce on Non-Lawyers was launched in 2008. The Taskforce was jointly organized by the judiciary and the executive to explore appropriate areas for paralegals to operate. Despite some initial progress by the Taskforce, in the end there was significant bureaucratic resistance to any reforms. By 2013, the Taskforce had been unable to approve its own terms of reference.

This may be unsurprising, given the history of efforts to diversify the legal profession in Liberia. In the immediate postwar period, for example, the Liberian National Bar Association fought off attempts by international development partners to explore the admission of foreign trained lawyers in an effort to expand the pool of qualified lawyers and improve the efficiency and accountability of the legal profession.Footnote 42 Liberia continues to have only one law school at the University of Liberia and entry into the Bar remains tightly controlled by law school administrators and senior members of the Bar Association. Despite some progress in reform, civil and criminal procedure remains extremely formalized and there are regular complaints that the system is essentially unintelligible for much of the population.

Opponents of Liberian paralegal programs typically argue that non-lawyers will provide misinformation to communities. One senior member of the legal establishment explained to us that paralegals carry a far greater risk than so-called barefoot doctors or primary healthcare professionals who work in local communities, providing information and helping refer serious medical cases to hospitals. According to this attorney, if a health worker provides misinformation, only the sick patient might die. If a paralegal, on the other hand, provides misinformation to a community on law and rights, the official suggested that the whole community would suffer irreparable harm (or “die” in his words).

Such views are commonly expressed in policy circles and many believe that paralegals should not be able to provide guidance on legal issues to communities and individuals. Liberian media reported, for example, that several members of the Liberian legal community attending the April 2013 National Criminal Justice Conference suggested that it was essential to avoid “non-lawyers posing as lawyers to exploit the common people who are already crying for justice.”Footnote 43 Lawyers also worry that paralegals will provide misinformation and prey upon the local population by demanding fees. Such positions overlook the reality that at this time the vast majority of Liberian paralegals provide services free of charge, or subject to a small fee.

While it is certainly important to raise questions of the cost and reliability of legal services, objections from many members of the Bar miss a fundamental reality confronting many in Liberia: most individuals simply cannot engage lawyers for advice or assistance or access formal courts with legal and administrative issues. The fees and geographic factors are prohibitive. The legal community is overwhelmingly based in Monrovia and, even there, it does not provide the types of services most people need: advice on rights, entitlements, and managing community-level disputes. Paralegal programs are instead working to respond to the actual needs and experiences of most Liberians in ways that are accessible.

Active obstruction by some in the legal establishment, compounded by a complex and slow-moving regulatory environment, has also limited international investment in paralegal programs and hampered efforts to diversify funding. For paralegal programs like the JPC’s CJA program to become sustainably successful in Liberia, they need to move from being exclusively externally funded to a central component of Liberia’s justice strategy. Rhetorically, there has been some support by senior officials, but policymakers, both Liberian and international, need to move away from short-term and iterant support to the sector. As several other chapters of this volume make clear, governments around the world are productively grappling with questions of how to integrate the paralegal model into state justice service delivery. Much as medical doctors work with a frontline of primary health care officials, the Liberian legal system might be strengthened through a broadening of avenues for legal information and assistance. A move away from a justice system that privileges legalistic approaches, and prioritizes the role of lawyers in formulaic proceedings, would respond to a call for just outcomes for the poor. Such efforts would be in line with the values of the majority of Liberians.

Developing ways to ensure the relative independence of paralegals while simultaneously providing sufficient funding will be a challenging task in the Liberian context. The availability of autonomous funding from government would require a reprioritization of justice sector activities and expenditure over a longer period of time. The international community should support such efforts to ensure the justice system is able to more holistically respond to the challenges most Liberians face.

VI. Conclusion

Liberia’s 2008 Poverty Reduction Strategy argues that a “culture of participation by all citizens and partnership with government is critical to increasing transparency and accountability, reducing corruption and improving governance.”Footnote 44 Community paralegals in Liberia play an important role in bringing this culture of participation to life. Beyond a focus on regulation, professionalization, and the perennial sustainability challenge of financing, a commitment by the Liberian government to focus on just outcomes, and strengthening the rule of law from a Liberian community and individual perspective, would be a necessary step in the right direction. The past ten years of experimentation with and rigorous evaluation of community-based paralegal models in Liberia has demonstrated quantifiable and positive results, in terms of both client satisfaction in the immediate case and broader socioeconomic benefits. There is a gradual realization in Liberia that rule of law reform that focuses predominantly on a foreign formal legal system is neither the only nor the best option for Liberians. Flexible, locally oriented legal assistance benefits the lived experience of the justice system and must factor in Liberian rule of law reform. This alternative path prioritizes engagement at the community level and empowers individuals and communities to navigate the administrative and bureaucratic structures that govern their lives, demand appropriate reform, and access a holistic justice system that can provide redress for wrongs and the peaceful and productive resolution of disputes.