Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- 39 Polymer Banknote

- 40 Post-it Note

- 41 Betamax

- 42 Escalator

- 43 3D Printer

- 44 CD

- 45 Internet

- 46 Wi-Fi Router

- 47 Viagra Pill

- 48 Qantas Skybed

- 49 Mike Tyson Tattoo

- 50 Bitcoin

- About The Contributors

43 - 3D Printer

from The Digital Now

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- 39 Polymer Banknote

- 40 Post-it Note

- 41 Betamax

- 42 Escalator

- 43 3D Printer

- 44 CD

- 45 Internet

- 46 Wi-Fi Router

- 47 Viagra Pill

- 48 Qantas Skybed

- 49 Mike Tyson Tattoo

- 50 Bitcoin

- About The Contributors

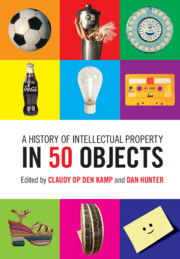

Summary

THE 3D PRINTER is not new: the technology dates back to the 1970s. Initially controlled by a thicket of patents, it only became commercially significant when the main patents expired and a range of homebrew developers saw the benefit in the widespread adoption of a range of 3D printing technologies.

The first patent for the technology was granted on 9 August 1977 to Wyn Kelly Swainson, an American. Although it did not lead to a commercially available 3D printer at the time, it paved the way for the manufacturing of 3D parts. Shortly thereafter, Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute published his work in producing a functional rapid-prototyping system using photopolymers, a photosensitive resin that could be polymerized by a UV light. In a process that is now familiar to most, a solid, printed model was built up in layers, each of which corresponded to a cross-sectional slice in the model. Kodama never patented this invention, and the first commercial 3D printer was launched in 1988 by Charles Hull— another American—following a patent for “Stereolithography” granted to him in March 1986. In 1988, at the University of Texas, Carl Deckard brought a patent for a different type of 3D printing technology, in which powder grains are fused together by a laser. From these three different approaches, and the patents that protected them, 3D printing born.

The 3D printer, and the process of 3D printing, has caused a great deal of hype in recent times for a range of reasons. The technology became widely accessible because of a move away from commercial and industrial printers to low-cost desktop printers, a movement caused by the expiration of the foundational patents. This gave rise to the “Maker Movement”—similar to the homebrew computer clubs that formed around personal computing in the 1980s— that made 3D printing more accessible and appealing, and which captured the imagination of the consumer. In 2005, Neil Gershenfeld predicted that “personal fabrication will bring the programming of the digital worlds we've invented to the physical world we inhabit.” Barely more than a decade later, Gershenfeld's prediction has become a reality.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 352 - 359Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019