Carnival war was born during the brief but intense cultural moment of the Shanghai–Nanjing campaign when new literary, technological, military, and social forces swept into the Japanese home front. Out of this volatile maelstrom, mass media organs spawned the new wartime creatures of “thrills” and “speed” to reconfigure the violence of total war for mass consumption. Even with the fall of Nanjing and the fading of the war hysteria, these media-constructed phantasms continued to shape how intellectuals, reporters, and other agents of the culture industries promoted, debated, and gave meaning to total war until the twilight of the Japanese empire.

In a narrow sense, “carnival” refers to the chaotic media coverage of the Shanghai–Nanjing campaign from August to December 1937, which Japanese military and police officials criticized as a literal “raucous carnival” (omatsuri sawagi) for undermining state-managed spiritual mobilization. Irreverent celebrations of violence undermined government efforts to construct deep emotional connections to the war among the populace through economic frugality, public service, and participation in a variety of patriotic rituals.Footnote 1

In a broader sense, however, carnival describes the nature of Japanese state–society relations in wartime. At first glance, the media-driven war fever during the first stage of the China War in 1937 seemed to replicate patterns found in the 1931–2 Manchurian Incident. During the Manchurian Incident, the major dailies, driven by commercial ambitions to expand circulation into rural areas and dominate the national news market, mobilized the public into war frenzy to support the Kwantung Army’s invasion of Northeast China. This resulted in a more homogeneous narrative glorifying Japanese military expansion into Manchuria that dovetailed nicely with the government’s policy of “go-fast” imperialism.Footnote 2 When the China War erupted in July 1937, newspapers once again sensationally denigrated the Chinese and proclaimed the righteousness of Japanese military action in North China, not only to attract readers and boost circulation but also out of a sense of patriotic duty to nation.

One important difference in the media landscape after 1937 was that the state censorship system had become much more intrusive. When fighting between Japanese and Chinese forces broke out near Beijing in July 1937, the Army, Navy, Foreign, and Home Ministries all invoked Article 27 of the old Newspaper Law, requiring government clearance before the mass media could publish any reports about the war. The government decrees were designed to carefully manage both how the home front understood the significance of the fighting and to present a positive image of Japan overseas. In addition, the Army Ministry ordered censors to “safeguard military secrets in light of the danger of bringing out great harm to the military’s strategic plans.” After initially urging a “non-expansion policy” in China, the Konoe cabinet reversed course on July 11 to approve the army’s request for reinforcements in North China. At the same time, Prince Konoe summoned leading figures from the financial and publishing worlds to his official residence and secured their agreement to adopt a “national unity” position in supporting the government’s policies in China. Home Ministry censors issued a separate notice to all local officials on July 13 to ban the printing of “fallacies that are fundamentally mistaken on our China policy or reveal territorial ambition or bellicose use of force,” which would “contradict national goals” and “confuse the hearts of people and induce social unrest.” The Home Ministry further ordered newspapers not to print any “anti-war or anti-military articles,” “articles that give the impression that Japanese people are bellicose,” and “articles harboring suspicions that Japan’s external policy is aggressive.” These top-down commands were reinforced by informal consultations between media representatives and Home Ministry officials to prevent the publication of objectionable materials and clarify the boundaries of acceptable reporting. In other words, the wartime censorship rules were implemented by both official bureaucratic directives and appeals to the good graces and “courtesy” of media companies to practice “internal guidance” and self-policing.Footnote 3

Elaborate state controls restricting press coverage were supplemented in September 1937 with positive messaging from the government-sponsored National Spiritual Mobilization Campaign Central League. Under the joint supervision of the Home and Education Ministries, this organization was charged with channeling popular support for the war around the ideas of “national unity,” “loyalty and patriotism,” and “untiring perseverance.”Footnote 4 Just as soldiers were tirelessly fighting for the nation overseas, the Spiritual Mobilization Campaign called on civilians to devote themselves to “loyally serve the emperor and give back to the nation,” and prepare for long-term sacrifice.Footnote 5

In the face of such extensive state measures to tightly control and unify press coverage of the war, scholars have typically viewed the mass media in the China War as degenerating into mere parrots of government propaganda. Hata Ikuhiko argues that deviation by journalists from the official line was prevented by a powerful censorship system and the unconscious self-censorship of the media. Consequently, he contends, war coverage during the 1937 Shanghai–Nanjing campaign was based primarily on military press releases and traditional heroic war tales.Footnote 6 Although acknowledging the general media excitement on the home front, Haruko Taya Cook also finds that “the newsmen were only covering the story exactly along the lines provided by army headquarters. Their perspective is completely that of Japanese military authorities and not that of either troops or independent observers.”Footnote 7 Gregory Kasza similarly concludes that, after 1937, “given the penetration of mobilization policies, the resistance of the mass media was feeble on the whole, and the fundamental reason was patriotic support for the country at war.”Footnote 8 Indeed, the media did not report on the great massacre at Nanjing or other related mass killings by Japanese soldiers in any way that might provoke the ire of military censors.Footnote 9

However, as the war in China quickly spiraled out of control beyond the overly optimistic predictions of the Japanese military, media coverage escalated to unprecedented sensational excess, provoking harsh criticism and private anxieties from military censors and civilian commentators. The resulting media-promoted spirit of irreverence found during the first phase of the China War may have acted as a safety valve to soothe popular disgruntlement over the rigors of spiritual mobilization, a fact which points to the limits of carnival’s subversive nature.Footnote 10 But it also destabilized state propaganda by forcing consumer-subjects to constantly switch between an official and a “carnivalized” understanding of the war.Footnote 11 In other words, Japanese society was mobilized for war through these conflicting visions of modern life: one that was regimented formally and informally by the state and another which eluded such controls to celebrate the grotesque and nonsensical.

The reasons for this bifurcated condition of mass mobilization can be traced to the relative powers and cultural cachet of censors and reporters. In practice, Japan’s military censorship system during the first six months of the China War was decentralized and starved of adequate resources and staff. War correspondents embedded with army units took advantage of the unevenly repressive censorship system to construct new spaces and content for aggressive and wild war coverage that would electrify the masses over a full-scale war against China. As a result, amid Shanghai street-fighting and particularly during the race to Nanjing, it was the war correspondents and not the military censors who shaped the tone of the news coverage.

This chapter explores three general but interconnected aspects of carnival war – the resilient sense of play within national mobilization, the ambiguous meaning of subversion, and the celebration of both the brutality and exhilaration of modern warfare. Exploring these issues requires historians to rethink the unquestioned dominance of wartime state ideologies within industrialized mass culture.Footnote 12 A close reading of carnival war shows how state ideologies promoting rigid discipline, selfless sacrifice, and solemn patriotism clashed with contradictory media celebrations of the grotesque pleasures of modern life. And that clash in turn inspired further improvisation and revolts among state and non-state institutions. However multiple and contradictory, these visions, weaving together repression and joy, demarcated the broad parameters of carnival war. The figure who tried to control how the war was talked about was the unfortunate military censor. And the figure who outfoxed the censor to give a joyful voice to the world of carnival war was the reporter.

The Censor Becomes the “Effeminate Bookworm”

Although fearsome in appearance, the sprawling military censorship system that sprang up in the summer of 1937 was only unevenly applied by authorities. For example, in August 1937, the Army Ministry received 1,360 requests from newspapers to print military-related articles or photographs. Almost 80 percent (1,086) of the requests were approved, while only 20 percent (274) were rejected. Thereafter, to the alarm of Home Ministry police observing the Army Ministry’s censorship activities, “whatever the month, almost all submitted articles are approved.” The high approval rate was likely due to self-censorship among newspaper editors, who only submitted for review pieces they knew were likely to be approved. So long as articles mostly promoted valorous exploits of Japanese soldiers, and did not contain photographs or content that showed Japanese atrocities against Chinese or suggest the Japanese military was in a strategically disadvantageous position, newspapers were given relatively wide breadth of coverage. The one exception to this lax attitude was press photography on the frontlines. The military recognized the power of photography in swaying popular opinion back home and thus aggressively censored more images than text.Footnote 13

The Navy Ministry introduced its own system of censorship in August 1937 after a naval clash with Chinese soldiers in Shanghai prompted direct naval participation in the war. On August 16, the Navy Ministry invoked Article 27 of the Newspaper Law to prohibit “the printing in newspapers of items concerning the operations of the fleet, vessels, airplanes, and units, and other classified military strategy.” Following the Army Ministry, the Navy Ministry also set up its own direct pre-censorship review system. And like the Army Ministry’s “ministerial decrees,” the Navy Ministry typically rubber-stamped the vast majority of articles while rigorously reviewing newspaper requests to print photographs.Footnote 14

But the most hands-on censorship and coordination of the early war coverage was handled by the Army Ministry’s Military Press Department (gun hōdōbu). On August 20, 1937, a few days after the war expanded to Shanghai, a small group of army officers arrived in the city’s International Concession to establish the Press Department’s onsite office. The Press Department’s primary purpose was to act as liaison between the Japanese newspaper correspondents and the field armies for arranging interviews and press briefings. The first few months of the Press Department were difficult, as the location of the office was exposed to daily mortar shelling by Chinese forces. The dangerous work conditions contributed to a chronic personnel shortage, and the office had trouble finding even a copyist and a driver. Inexperience was another problem. Major Mabuchi Itsuo, the department head, later admitted that he was a “complete novice” in media matters. Despite little training in dealing with the press, Mabuchi was picked by superiors to serve as official army spokesman for the Japanese press corps in Shanghai, which quickly ballooned to over one hundred reporters. He recalled how he “was at a total loss as to how to handle this. I wished that a bullet would just hit me or that I quickly be made into a battalion commander and leave for the frontlines.”Footnote 15

In addition to the lack of resources, dangerous conditions, and inexperienced staff, military censors sometimes struggled to gain even minimal recognition or understanding from other military personnel. Mabuchi recalled “all kinds of nonsense” happening in the early days with lost Japanese soldiers separated from their units stopping by the Press Department to ask for directions. Due to the similar-looking characters used for each term, soldiers confused the relatively new word “press” (hōdō 報道) with street guide office (michiannai 道案内). Other soldiers would stop by the office to seek counseling, having confused “press” (hōdō 報道) with “guidance” (michibiku 導く).Footnote 16

Within the military, there was institutional contempt for propaganda and censorship work. Despite years of research about the importance of propaganda following the defeat of Germany in the First World War, senior officers viewed military posts dealing with the media as tedious and decidedly unglamorous. Instead, most officers coveted higher-profile appointments overseeing military strategy, tactics, and field command.Footnote 17 One lieutenant colonel transferred to do censorship work grumbled that “the press department is not a place for a real warrior.” Another former Press Department staffer, alluding to the fact that press officers essentially sit in an office all day reading books, magazines, and newspapers, recalled that he and his colleagues were known within the military as “effeminate bookworms” (bunjaku).Footnote 18

On the China front, some field commanders accommodated the Press Department’s requests to allow reporters to visit the frontlines, but others were annoyed at being followed around, while still others worried about reporters leaking classified information to the public. Not a few officers flatly refused to cooperate with the Press Department. Hearing reports of “troubles” (toraburu) between reporters and officers in early September 1937, Mabuchi decided to personally escort a group of correspondents to cover the fighting in Wusong, only to have to turn back to Shanghai upon receiving a terse message from one of the field commanders: “War correspondents are a nuisance and useless in carrying out operational duties. The embedding of reporters is for now denied.”Footnote 19

According to his 1941 memoirs, Mabuchi recalled a major incident breaking out in October 1937 between the military and the press when one newspaper (discreetly unnamed) broke the news that the army was preparing to launch a new offensive against the Chinese city of Dachang. Field commanders were enraged that reporters had publicized a classified campaign, thereby removing the element of surprise and allowing the Chinese time to fortify their defenses. The field commanders accused the Press Department of leaking the plan to reporters and demanded the court-martial of press officers. Mabuchi defended his staff and, after an investigation, concluded that the leak was the result of inadvertent misunderstandings. His explanation also revealed how understaffed the department was: “I was away traveling in the front and a temp who was filling in for my absence did the inspection [of the newspaper article]. Of course, he had no idea about the operational plans and gave the article a pass.” Although “all kinds of troubles arose from this issue,” Mabuchi noted that “somehow things calmed down.” Yet, reflecting on the uproar four years later, he lamented the weak coordination of military propaganda and censorship and reiterated his criticism of uncooperative field armies. Mabuchi also endured irate complaints from newspaper executives when his office blocked the reporting of certain war stories. “It was just impossible,” he remembered, “because someone like me with no tools was standing over and trying to regulate the person who had all the tools.”Footnote 20

Indeed, Mabuchi frequently blamed the troubled relationship with field armies for making the Press Department’s job all the more challenging. Field commanders withheld so much intelligence from military censors that he had to personally drive out to the front every morning to find out the latest war developments for press briefings. The Press Department was also in charge of censoring all articles before they were sent back to Japan. However, since the department was understaffed, Mabuchi finally asked the newspaper bureau chiefs to conduct their own internal censoring and only submit drafts to the Press Department to verify specific facts. To his relief, Mabuchi recalled, the newspapers were in “complete agreement.”Footnote 21

When the Imperial General Headquarters issued the order for the Nanjing assault in early December 1937, the Press Department immediately banned all newspapers from reporting the fall of Nanjing until an official military announcement was made. Reporters, vying with each other to scoop the news of Nanjing’s capture, hounded Mabuchi for clues as to which unit would reach the capital first. The competition among the correspondents during the Nanjing campaign, he observed, “grew more passionate than the besieging units.” During the chaotic march from Shanghai to Nanjing, some correspondents sent off reports of the capture of a Chinese city before it had really happened: “When a staff officer of one unit murmured, ‘looks like such-and-such town can be taken,’ the war correspondent standing next to him said, ‘All right, then it’s already occupied,’ and sent a telegram that such-and-such town was occupied. In the strict sense of the word, this was problematic communication, but I understood his impatience.”Footnote 22 Market competition placed intense pressure on news outlets to be the first to report the fall of Chinese cities, even if such reports turned out to be erroneous. For instance, both the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun and Dōmei Tsūshin news agency announced the fall of Wuxi on November 22, although Wuxi did not actually fall for another three days.Footnote 23

The powers of Mabuchi’s Press Department were further circumscribed by the permissive behavior of press officers. In early December, a “certain newspaper” ignored the department’s strict ban and scooped its rivals by printing a story about the Yoshizumi Unit seizing Nanjing’s Guanghua Gate. The blatant insubordination, according to Mabuchi, “created a huge uproar on the home front … and threw local regulation and controls on reporters into disarray.” The press officer conceded that “our controls over local reporting fell into chaos right at the critical moment of Nanjing’s imminent fall.” Nonetheless, Mabuchi and his colleagues imposed only mild punishment on the newspaper – one-week suspension from the Shanghai Reporters Club and no more complementary frontline inspections aboard military planes until the day before the army’s ceremonial entry into Nanjing. Harsher punishments were proposed by others, but Mabuchi was reluctant to crack down too hard: “I could not bear to impose a handicap (handekyappu) on the war correspondents working on the frontlines and risking their lives for articles and photographs.” He admitted that “outsiders” found the Press Department’s measures to be surprisingly “lukewarm” and “lenient.” However, he defended his decision, claiming that “in those tense moments when every second counted, the punishment was quite severe and, indeed, sufficient, for the newspaper.”Footnote 24

This is not to say that censorship was completely ineffective. The highly restrictive measures imposed on reporters by military and government agencies prohibited reports of battlefield operations except in the vaguest of terms, thereby driving newspapers to seek other kinds of war stories. As the casualties mounted, for instance, newspapers competed to be first to report the names and hometowns of the war dead, thereby drawing in civilian readers eager to find out the fate of loved ones.Footnote 25

But the intensive market pressures among newspapers helped undermine the elaborate wartime censorship system, so painstakingly created months earlier by Home Ministry bureaucrats and military officials. Thrill-seeking war correspondents stepped into this vacuum, as the first kings of carnival war, to capture the excitement of modern warfare for Japanese consumer-subjects.

The Reporter Becomes the “War Correspondent”

Despite his complaints about insubordinate reporters, Mabuchi praised war correspondents for keeping the home front informed about the fate of loved ones fighting on the front. He likened them to soldiers for “running around in the battlefield, with a pen instead of a gun, a camera instead of a cannon.” He believed that reporters played an especially important role in “modern warfare” for boosting the spirits among soldiers on the warfront and civilians on the home front with the latest war news. Thus, for Mabuchi, reporters were not to discover and report the “truth” of the war. Rather, their role was to provide critical psychological uplift for soldiers and civilians so that everyone would fully contribute to the war effort. “This is their most important mission,” Mabuchi intoned.Footnote 26

Indeed, the military demonstrated a conciliatory attitude toward the media in recognition of their important role in presenting a favorable picture of the war to the Japanese public. On August 4, 1937, the Army Ministry officially recognized all newspaper reporters, cameramen, and film operators working in China as “army war correspondents” (rikugun jūgun kisha).Footnote 27 The number of war correspondents quickly ballooned as the war escalated. In October 1937, nearly 500 reporters were covering the war on the front.Footnote 28 By the end of November 1937, this figure doubled to 1,000 reporters.Footnote 29

Perhaps unsurprisingly, newspapers feted reporters with praise typically given to soldiers, as on August 8, 1937, when the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun declared, “Let us pray for the War Correspondent.” The paper reported that the Tsuruoka Hachiman Shrine in Kamakura held a special prayer service not for soldiers but for “the newspaper reporters of all papers toiling alongside soldiers in the intense heat of the North China frontline, fulfilling their important mission of patriotic writing.”Footnote 30 The Tsuruoka Hachiman Shrine also donated 53 “talismans” to the Asahi for their reporters in China.Footnote 31 In November 1937, the powerful ad agency Dentsū put out four large notices urging civilians to give the same “comfort” honoring reporters killed in China as that given to fallen soldiers: “We believe that the glory of these victims has not one bit of difference with the honor of those killed in battle.”Footnote 32 On December 6, 1937, the New Japan Sailors Union in Osaka passed a resolution to “express gratitude to the newspaper special correspondents undergoing hardships on the frontlines since the outbreak of the Incident, along with imperial soldiers.”Footnote 33

Basking in official endorsement and glory normally reserved for soldiers, reporters frequently became the topic of discussion among intellectuals as a new phenomenon peculiar to total war with the power to sway public opinion. In October 1937, the literary commentator Sugiyama Heisuke noted that the role of journalists is to “be the first to report on a situation where some dangerous phenomenon has arisen, then analyze, interpret, and tell its significance to people.” However, he worried that this approach had led journalists toward superficiality and sensationalism, with “newspapers going wild with craze, devoting an entire page if there were stories about a serial killer or someone killing his son for insurance money.” For Sugiyama, the unfolding war in China only intensified this thirst for sensationalism among reporters on a massive scale: “If a serial killer story in peacetime would fill one page in the society section, then even a 300-page newspaper wouldn’t be enough to cover a single day of war.” Already in the early months of the war, Sugiyama noticed how reporters could easily shift the public’s attention to the latest battle at the expense of other stories which normally would have garnered significant coverage. “The murder of one or two people can be written off in a couple lines,” he lamented. “This is the age we are in now.”Footnote 34 The reporter was understood to be vitally important for the home front to stay abreast of the war, but also had the potential to dangerously disrupt and inflame public opinion.

However, in November 1937, journalist Ōya Kusuo was more sanguine about the reporter’s role on the home front. He believed that a new relationship had taken shape between the press and the military. In previous conflicts such as the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, reporters were dismissed by the military as “outsiders” (tanin) and “nuisances” (yakkaimono). In the earlier wars, reporters would just stay behind the frontlines at the general staff headquarters and only visit the battlefield after fighting had finished to file a report. “But in this current Incident,” Ōya wrote, “such a leisurely, unhurried thing” (yūchō na koto) would not be tolerated by the frontline press corps. Starting with the Manchurian Incident, and especially in the current war in China, he felt that the relationship between the military and the press corps had remarkably improved, to the point that “already today the reporters are not treated as annoying burdensome bystanders.” Indeed, Ōya saw reporters as becoming assertive and even aggressive participants in war: “The reporters themselves will not take being treated like a nuisance lying down.” Reporters now worked right alongside soldiers on the frontlines, he said, and suffered casualties just like soldiers. “They are by no means writing ‘observations of military operations’ (kansen kiji),” he claimed. “While they may not be armed with guns, they fight alongside soldiers and dispatch ‘notes about real fighting’ (jissen shuki).”Footnote 35

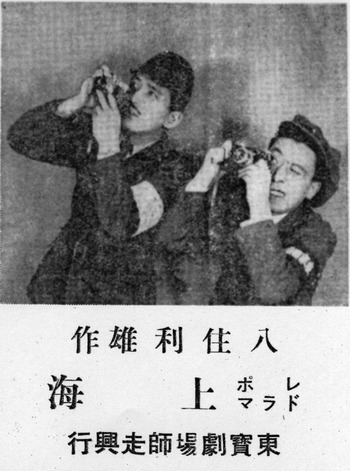

But because the reporter was now imagined to be actively covering the war right alongside soldiers on the frontlines, observers of the newspaper industry all agreed that reporters must be young and enthusiastic. According to one anonymous columnist for Nippon Hyōron (Japan Review) in October 1937, “it is deeply felt that the war correspondent must be young. Reporting out on the frontlines is not suitable for one who is an old, seasoned veteran.” The columnist admitted that old reporters may still be suited for covering the occasional story outside of battle, but their headlines still required touching up by editors to fully capture the excitement of war. Seasoned reporters had become too accustomed to war and were no longer fazed by the scale of violence in battle. The columnist gave as an example a recent newspaper headline about Japanese forces destroying Tianjin’s East Station. The headline had to be revised by the editor into a more exciting style to draw reader attention: “East Station Blown to Smithereens, No Trace Left” (koppa mijin). While the headline was probably “a bit grandiose” and not close to the actual experience of the jaded old reporter, the columnist conceded, it was the kind of headline that war coverage needed. This made the youthfulness of reporters all the more important. “The writings of a young reporter will be personally different,” the columnist concluded. “You can liken it to baseball broadcasting, but he will certainly connect with the hearts of readers” (see figure 1.1).Footnote 36

Figure 1.1 Two war correspondents as depicted in Tōhō Theater’s December 1937 “reportage drama” (repo dorama), “Shanghai.” Sunday Mainichi (December 12, 1937): 35.

Another industry insider concurred in October 1937, writing that “being young in age is an indispensable condition for newspaper reporters.” For this anonymous writer, youthfulness would mean reporters with “physical strength” (tairyoku) able to keep up with soldiers fighting on the frontlines. Thus, “at the very least, around thirty years old or so.” He was a little concerned with the average age of Mainichi reporters being between 36 and 37 years old: “Quite astonishingly old reporters,” he lamented. He cited the case of Special Correspondent Hirata from the Mainichi as a cautionary tale for allowing reporters above a certain age to cover the war. During a recent campaign in China, Hirata fell behind following a “much younger” reporter and ended up being killed by Chinese soldiers. Although acknowledging Hirata’s talents as a writer, the columnist felt he was past his prime: “if pushed I’d say that he was at the age when he should have been an advisor at headquarters.”Footnote 37

Writing two years later in 1939, the noted journalist and founder of Japan’s first journalism school Yamane Shinjirō rapturously described the national importance of the reporter as “a kind of public figure (kōjin) whose actions resemble that of a teacher, physician, priest, and attorney, with the professional duty to work with the masses to cover and criticize the various matters of state and society.” He noted the enormous power of the reporter, despite growing state censorship controls: “If with one stroke of the pen, the reporter can disrupt public peace and endanger people’s daily lives, then his character is definitely not something we can ignore.” Reiterating earlier claims by others that the reporter in wartime must be relatively young and physically strong, Yamane argued that “the Reporter today is required to have vigorous health and strength. He must have excellent physical strength, working late into the night, performing superhuman feats covering a big story, or else he simply cannot do the job.” He noted approvingly that “during the China Incident, many war correspondents on the frontlines would dive through gunfire, or run through kilometers of mud carrying a wireless radio. They struggled with hardships unimaginable to a public who just thinks of the reporter with his fountain pen.” Yamane also believed that “common sense” (jōshiki) in knowing a little bit of everything was important to be a successful journalist, as well as being attentive and observant of everything. Thus, an individual with an educated background twinned with youthful vigor was the ideal journalist.Footnote 38

The Thrills of Total War and the Crowning of the “Thrill Hunter”

Along with the new upstart status as “war correspondent,” the reporter also drew upon a new vocabulary which instantly conveyed battlefield violence to the masses as exhilarating, modern, and playful. In the early 1930s, intellectual observers of new social trends began using the word “thrills” (suriru) to refer specifically to the tension experienced watching an exciting film that induced fear or terror. One of the earliest descriptions of thrills is in the 1930 Modern Terminology Dictionary, which defined it as “emotionally moving, shuddering, shivering. The thrill of movies is the climax where the audience is drawn in and made to shudder.”Footnote 39 The 1932 Latest Encyclopedic Social Language Dictionary similarly described thrills as “a film term referring to a climax or tension that sends a chill down one’s spine.”Footnote 40

By the summer of 1936, the growing popularity of the word inspired literary critic Ōya Sōichi to write about a “theory on thrills” (suriru ron).Footnote 41 Modern societies, according to Ōya, are full of “thrill hunters” (suriru hantā) seeking relief from the stresses of modern life because the “modern man” was “suffocating” in an increasingly atomized mass society. Ōya found that thrills had a rather nihilistic quality. There is no purpose in thrills other than to seek them out. There is also no universal standard to judge the quality of thrills, since it all depended on individual tastes and circumstances. Instead, quantity is the only thing that matters, along with the amount of perceived danger. Incidents of sensationalized violence such as murder cases or even the recent February 1936 attempted army coup, Ōya continued, provide the “perfect opportunities” for throngs of “thrill hunters” (a word he used several times) to “satiate their lust for ordinary thrills.” He stressed the modernity of thrills by arguing that they were particular to a mass capitalist society with a heavily commercialized mass media. “Modern men,” he explained, could no longer be satisfied by naturally occurring thrills and needed more intensive and “artificial” variants constructed by media, much “like morphine to a drug addict.” This metaphor underscored Ōya’s understanding of thrills as something modern, manufactured, and pleasurable, but also highly addicting and potentially deadly. To further illustrate the modern, commercialized, and addictive qualities of thrills, Ōya devised a “formula” to calculate the “thrill value” (suriru-ka) of anything:

The formula, he claimed, is used by people to decide which activity to engage in based on the quantity of thrills it contained. Likening “thrill value” to calories in food, Ōya argued that the most alluring thrills had to be mass produced and cheaply sold. An undercurrent of deviance or edge was also needed. It was for this reason, he said, that the popularity of traditional geisha among the urban masses was supplanted by more illicit and affordable street prostitutes who, in turn, lost their appeal upon gaining limited state recognition. “Thrill hunters” then turned to the new, sexually charged café waitresses knowledgeable of cutting-edge modern social mores.Footnote 42

The idea of thrills as a phenomenon of capitalist modernity, extreme pleasure, and momentary celebration of transgression was echoed in a “New Word Dictionary” definition appearing in the January 1937 issue of Gendai (Modern) magazine. Thrills, the dictionary explained, were “the pleasant aftertaste of pure fright,” while adding, “To the extent one knows that modern life is dangerous like walking on the edge of a sword, thrills exist everywhere in the everyday.”Footnote 43 Similarly, in November 1936, the Tokyo Asahi described parachute jumping as “a modern, thrilling stunt in which with one false step you fall down head over heels.”Footnote 44

With the launching of full-scale war in China in 1937, the reporter picked up thrills and turned them into code that mixed together the visceral pleasures of killing, violence, and humor into an arresting cocktail within the otherwise oppressively solemn and severe edifice of wartime tension. Reporters dispatched to the front became, in a sense, professional “thrill hunters,” seeking stories of increasing extremity to capture readers’ interest and drive up circulation. As fighting between Japanese and Chinese forces broke out in the late summer and early autumn of 1937, “thrills” appeared with increasing ubiquity in news coverage.

Shortly after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937, correspondents from the Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun (commonly abbreviated as Tōnichi) reported experiencing “life and death thrills” when coming under enemy mortar fire.Footnote 45 In the wake of the Konoe Cabinet’s escalation of the war from minor skirmish to a mission to “chastise atrocious China” in August 1937, a Tokyo Asahi reporter described to readers about the “thrills of a three-dimensional war” as Japanese residents in Shanghai watched “with stirring, unparalleled, thrilling, breathless excitement and cried out in wonder at the technological marvel of [the Japanese planes] dropping bombs.”Footnote 46 During the height of Shanghai street-fighting in October 1937, perhaps in recognition of its growing ubiquity in war coverage, the Tōnichi introduced the term to the public in its “New Word Explanation” column:

Thrills – In English, it means “shivering” or “shuddering” … the tone to “thrills” you hear on the streets nowadays closely matches the sensations of the modern man … if air raids are thrilling then mountain climbing is also thrilling. There are thrills even in evading your parent’s watchful eye to break the law for love. If one carries out these adventurous acts, then anything can be thrilling.Footnote 47

That same day, the Tōnichi described an account of one correspondent’s “miraculous” escape from enemy fire as “the Thrills of the Front Lines.”Footnote 48 In November 1937, a Tōnichi correspondent who went undercover as a Filipino reporter to infiltrate a Shanghai movie theater described watching an anti-Japanese film that “calmly showed atrocious, dead bodies one after the other; things got 120 percent thrilling as I shuddered in horror at the brutality of the Chinese.”Footnote 49 The capture of Nanjing in December 1937 similarly spawned a “thrilling tale” by Sublieutenant Shikata, whose unit was the first to enter the city. Shikata boasted of his unit finding and killing a group of fleeing Chinese soldiers near Chungshan Gate. “Look!” he excitedly told reporters, “All those corpses were killed by us.”Footnote 50

The idea of thrills was also used by reporters in conjunction with “humor” in battlefield violence. In November 1937, a group of journalists gathered in a roundtable sponsored by the weekly magazine Sunday Mainichi to discuss “thrills and humor (yūmoa) in bullet-ridden Shanghai.”Footnote 51 The discussion revolved around stories of narrow escapes from death while covering the Shanghai frontlines. In that same month, Tōnichi correspondents, in a long article filled with several references to thrills and humor, enthusiastically announced, “A World Rat-Trap Spectacle: The Last Chapter of Shanghai Street-fighting, Enjoying the Thrills of Modern Warfare, The Grand Finale to a ‘Hilarious Tale of Tragedy,’ Shocking an International Audience.” Hearing about a battle in the Zhabei district, the reporters rushed over “to witness the final three-dimensional war, one hundred percent thrilling Zhabei street-fighting.” Japanese troops had cornered a Chinese-held building and begun exchanging gunfire. By nightfall, the firing momentarily stopped until the reporters felt that “preparations for our offensive finally seem to be ready and before long, this sanctuary of thrills will be silenced by our evil-crushing sword.” Later that night, “the thrills thickened more and more” until the Japanese soldiers finally stormed the building.Footnote 52

The intersection of mass media and total war in 1937 transformed a foreign loanword to connote cinematic excitement into a code for carnival laughter in the face of violence. Thrills became the inverted doppelganger to the “tension” or “anxiety” (kinchō) of mobilization, distinct from the patriotism and seriousness of purpose promoted by the National Spiritual Mobilization Campaign, much to the chagrin of outside observers. A Bungei Shunjū magazine columnist complained that wartime newspapers were concerned only with finding “color, ideology, and thrills”:

War is not some drama at all, but newspapers treat it as a dramatic scene in which the reader becomes a character within his own drama. He forgets the purpose of war and its true nature. Although we keep saying there is still a long road ahead, he already gets drunk with the mood of victory. He desires a cheap peace and lacks any general tension.Footnote 53

The idea of thrills became a linguistic metaphor bringing the violence of total war up-close for mass consumption, overturning the seriousness of mobilization. In this sense, it was not a form of escapist fantasy or merely an outlet for people seeking relief from the stresses of wartime life. In the discursive space of mass culture, it emerged in reaction to the rising “tension” of mobilization. Thrills conveyed an aspect of wartime culture distinct from the patriotism and seriousness of purpose promoted by the National Spiritual Mobilization Campaign. Writer Kimura Ki observed that more intellectuals like him were heading over to the China front to write reportage accounts than during previous wars. Improvements in transportation and reduced travel costs, he speculated, made these journalistic opportunities more appealing to writers. “But as for me,” he insisted, “the first attraction was the thrills of war.”Footnote 54

“Thrills” also contained its own mode of disciplining consumers to a new world of modern dangers – forcing them to sharpen their senses, to viscerally feel the plunge of a sword into flesh, the cold sweat on their bodies after escaping gunfire or hearing the explosions and screams during an air raid. As Enda Duffy has argued about “thrillers” in modern “speed societies,” thrills essentially represented “incitement on the one hand, education through terror on the other.”Footnote 55 The adoption of “thrills” by reporters to capture the excitement of battlefield violence laid the foundations for increasingly irreverent stories from the front and a template through which war and mass culture could intersect. Through thrills, the mass media brought Japanese consumer-subjects into intimate contact with total war by transforming battlefield violence into a visceral and vicarious experience that brought together humor, exhilaration, and fear all into one alluring package.

The Speed of Total War

The reporter used thrills alongside the foreign loanword and cultural concept of “speed” (supiido) to help reconfigure total war into media spectacle. Speed as cultural construct was already an important part of prewar modernism and modern life in Japanese mass culture from at least the early 1920s.Footnote 56 There was a self-conscious awareness among Japanese writers and intelligentsia that modern life was accelerating due to new technological innovations and rapidly changing social norms. In 1930, magazine articles appeared discussing the “Speed Age” and the “Speed Problem.”Footnote 57 In 1931, a writer on “The Art and Science of the Airplane” declared that the 1930s would be a “high-speed culture.”Footnote 58 The January 1932 edition of “Latest Encyclopedic Social Language Dictionary” had no fewer than five speed-related entries: “Speed,” “Speed-Up,” “The Speed Age,” “Speed Meter,” and “Speed Mania.”Footnote 59

By the mid-1930s, the popular understanding of speed accelerating the pace of modern life was confirmed by new media technological innovations. In September 1936, the Asahi pioneered the photo-telegram, which came equipped with an electric battery and 100 feet of aerial wire to transmit photographs electronically. Shortly thereafter, newspapers began using the radio telephone, which could be carried safely into the frontlines and had a range of up to 60 kilometers.Footnote 60 The development of shortwave radio telegraphy allowed reporters to wire news from branch offices in China and Manchuria to the home offices in Japan. In addition, military expansion into North China was followed by reporters who established more offices in Tianjin and Beijing.Footnote 61 Thus, by the summer of 1937, reporters enjoyed greater physical and technological proximity to China than ever before.Footnote 62

This technological proximity accelerated the pace of news reporting, thereby creating a paradox in social acceleration. As communication and media technologies accelerated, the amount of time reporters and consumer-subjects had to process the news decreased.Footnote 63 There was more news than ever before, but it was increasingly difficult for people to make sense of it all. When the China War began, reporters realized that it would be unlike any previous conflict, full of hundreds if not thousands of individual experiences scattered all over the front and encompassing an array of strikingly different scenes from dramatic and rapid urban street- fighting and soldiers slowly marching through the vast Chinese countryside, to terrifying air raids, and grotesque nonsensical anecdotes.Footnote 64 To be sure, reporters continued to practice tried-and-true traditional war reporting such as tales of battlefield heroism (bidan) and reprints of military press releases. However, the overwhelming enormity and rapidity of the conflict both challenged and inspired reporters to experiment with new methods to explain the war faster and more comprehensively through the news film (which was put into far wider practice than during the Manchurian Incident), tales of the nonsensical and grotesque, contrived media stunts celebrating speed, and the captivating new genre of “reportage” (ruporutāju) written in a hybrid mix of diary entry, novelistic style, and travelogue. In early 1938, one intellectual critic lavished praise on “reportage” while heaping scorn on conventional literature for failing to capture “a world which changes its appearance one after another in a filmic, speedy (firumuteki supiidii) way. This speediness (supiidiinesu) has very great significance in the mental every day of the present, which has seen the development of communication and media networks.”Footnote 65

Speed could also signify new state restrictions on the individual’s freedom of movement, reflecting the penchant of modernity to discipline and regiment everyday life through Taylorist modes of production and scheduling. But speed, like thrills, could also unlock liberated, intense visceral pleasure, thus illuminating the other side of modernity. The self-consciousness sensation of speed immediately gave the viewer, consumer, and producer a sense of being at once overwhelmingly powerful and highly vulnerable. Furthermore, both the term and concept of speed and thrills fed off each other. For the all-consuming, insatiable impulse of speed and thrills in a wartime setting demanded a deterritorialized space – a place stripped of all previous local historical distinctiveness and identity; a blank slate onto which thrill hunters and speed seekers could construct new fantasies of empire.Footnote 66

In this respect, reporters who internalized the urgency of speed turned China into a non-place in media coverage. Reporters referred to Chinese soldiers as nondescript “enemies” (teki) who existed only to be summarily wiped out by Japanese soldiers in spectacular fashion. Reporters would, in rather aggressively casual and inconsistent fashion, sometimes write out place names phonetically with furigana to approximate the actual Chinese pronunciation, but other times would instruct readers to pronounce Chinese place names with Japanese pronunciations of the characters. Even radio broadcasters would pronounce already well-known place names approximating the actual Chinese pronunciation but then during the same program switch to a Japanese reading of less-familiar names.Footnote 67 The authenticity of reporting from faraway China was tempered by a dismissiveness towards a need for any serious representation of China as place. While ethnographic, almost prurient details about Chinese women appeared repeatedly in the wartime press, parallel to this conversation was a discourse that deemphasized the particularities of China as place and instead celebrated the speedy, thrilling movements of Japanese soldiers and reporters into, through, and out of China as space. Much of the actual battle coverage consisted of a seemingly endless listing of Chinese towns and villages with no description to distinguish one from another. The Japanese military conquered the new non-place of China through various levels of speed such as the rapid deployment of soldiers, tanks, artillery, and airpower. Japanese reporters echoed this speediness of war through near-instantaneous reporting with radio, photography, and telegrams.

Back on the home front, references to speed shaped how some media industry observers viewed the growing news frenzy of the military campaigns. In the newspaper industry periodical Gendai Shinbun Hihan (Modern Newspaper Critique), critics, usually anonymous, grumbled that the Tōnichi always “jumps the gun” in projecting the fall of Chinese cities. By contrast, the Asahi was criticized as “too slow and cautious” or even just a “slow-mo” (suro mō).Footnote 68 In October 1937, one industry critic of journalism complained, “The editors aimlessly focus only on speed – anything will do, doesn’t matter, just hurry, hurry. Newspaper editors focus more on speed and quantity over quality.”Footnote 69 The columnist “KRK” called the acceleration of war reporting “news speedyism” (nyūsu supiidiizumu) in depressing terms: “Newspapers have deviated from their true nature and write nothing more than fictional works. Fictional works are turned into telegrams, then print, and then into news … From their willful news speedy-ism to leaking military secrets, newspapers themselves misguide national policy.”Footnote 70

Home Ministry officials overseeing domestic media censorship worried about magazines and newspapers becoming more sensationalized by adopting the worst features of each other, thereby accelerating the pace and coarsening of the news. The bureaucrats quoted approvingly at length an article from the October 1937 issue of the right-wing journal Tōdairiku (Great Eastern Continent) on “The Crisis and Vulgar Popular Journalism.” According to the article, since the war began, “magazines have become newspaper-ized (zasshi ga shinbunka),” meaning that formerly thoughtful magazine pieces have deteriorated into flimsy ill-researched articles rushed to publication in imitation of daily newspapers. Newspapers were also criticized by Tōdairiku for turning into magazines (shinbun no zasshika) by devoting more pages to the arts and entertainment sections and hiring popular writers. The piece blamed the pernicious influence of commercialism pushing newspapers and magazines to “pander to readers” through articles that focus on entertainment as opposed to serious topics.Footnote 71

By November 1937, as the Battle of Shanghai started to wind down, Japanese army units shifted their attention to the Chinese capital city of Nanjing. The war transitioned from grueling urban street-fighting to a high-speed blitzkrieg across the numerous cities and towns stretched between Shanghai and Nanjing. As individual army units began racing toward Nanjing, reporters created the “first to arrive” (ichiban nori) contest, in which the first unit to enter a Chinese city would be praised in newspaper articles as “first to arrive.” For example, the Tōnichi reported in early November that in the occupation of Yuci, “first to arrive was the Okazaki Unit, followed by the Kobayashi Unit.”Footnote 72 The Sunday Mainichi breathlessly recalled for its readers the fierce race among rival Japanese units to be “first to arrive” at Dachang.Footnote 73 An embedded Mainichi reporter similarly declared, “Our unit lets out the war cry of first to arrive! The soldiers of all the units equally burned with the desire to be ‘first to arrive in Dachang!’”Footnote 74 Reporters also claimed for themselves the title of “first to arrive” in freshly conquered Chinese cities. In the early morning of November 9, Tōnichi correspondents followed the Ōba Unit in climbing up the walls of Taiyuan, noting, “among newspaper reporters, we were truly first to arrive.”Footnote 75 The most-prized goal among reporters was to be crowned “first to arrive in Nanjing” (Nankin-jō ichiban nori). At Nanjing’s Chungshan Gate, Tōnichi reporters ran into a surprised Sublieutenant Shikata (the man with the “thrilling tale”) who exclaimed: “Hey, are you Tōnichi? You’re terrifically fast. I’ll vouch that you guys were the first from the press corps to arrive here.”Footnote 76 One Yomiuri reporter secured permission to board an army attack plane during a bombing mission over Nanjing. The Yomiuri then proudly announced, “As a reporter he succeeded in being first to arrive from the skies in Nanjing.”Footnote 77

Thrills and Kills

In addition to “first to arrive” contests, reporters from both the national dailies and regional papers actively covered kill-counts by Japanese soldiers. These stories combined the whimsical attitude of thrills with the rushed velocity of speed. The Tokyo Asahi trumpeted on August 22, “Shanghai Camp’s ‘Miyamoto Musashi’ slays twenty Chinese soldiers like watermelon” (Shinahei nijūmei suika giri Shanhaijin no “Miyamoto Musashi”), only to be countered by Tōnichi’s September 2 story of a unit that “counted up to forty but later could not recall 1000 kills” (yonjūnin made kazoeta ga ato wa oboenu senningiri) and a September 3 “interview with the ‘1000-man killing unit’” (“senningiri” butai wo tō). Several kill-count stories used the phrase “clean sweep” or “killing with one sword stroke” (nadegiri). The Tokyo Asahi printed on September 9 a story of “Unit Commander Kakioka who, using his blade like a saw, jumped into a trench and killed 34 men in one clean sweep” (sanjūnin nadegiri). On November 17, the Fukushima min’yū similarly described a soldier who “could still fight even without bullets, sixty killed in one clean sweep” (tama wa nakute mo tatakai wa dekiru rokujūnin nadegiri).Footnote 78

The extraordinary violence of the Japanese invasion of China has been well-documented. However, what is less remarked upon is that the very words used by newspapers to describe the killing of Chinese soldiers, such as senningiri and nadegiri, carried irreverent double-entendres. According to the 2001 edition of the Nihongo dai jiten (Great Dictionary of Japanese), the word senningiri (literally “thousand-man killing”) could mean either, “slaying one thousand people for practice or for prayer,” or “having sexual relations with one thousand women.”Footnote 79 A “new word dictionary” (shingo jiten) from 1938 defined senningiri as “1) cutting down many people and 2) having [sexual] relations with many women.”Footnote 80 The same new word dictionary defined nadegiri as: “Having [sexual] relations with women one after another like cutting down vegetation.”Footnote 81

Recognizing this wartime media context helps us historicize the most infamous kill-count story, the Tōnichi’s coverage of the “Hundred Man Killing Contest” (hyakunin giri kyōsō). This was a contest between two young Japanese officers competing to see who could be the first to kill one hundred Chinese soldiers with a sword. Unlike the one-off kill-count stories, the Tōnichi devoted four installments of this killing contest during the Nanjing campaign from late November to mid-December 1937.Footnote 82 Today, the killing contest is remembered primarily through arguments between the left and right wing in Japan over whether the contest even happened, or as a shocking symbol of the cruelty of Japanese militarism and grotesque prelude to the Nanjing Massacre.Footnote 83 But at the moment of its production and consumption on the Japanese home front, the Hundred Man Killing Contest and the other kill-count stories may be understood as the culmination of reporters’ efforts to tantalize readers with thrills and speed in total war.

After the Second World War, several Japanese right-wing writers dismissed the Hundred Man Killing Contest as a pure fabrication by reporters, citing the nonsensical tone in news coverage and the ludicrous idea of a private contest conducted within the imperial army.Footnote 84 Indeed, the other kill-count stories compared the killing of Chinese soldiers with slicing watermelons, made references to the legendary samurai hero Miyamoto Musashi, and described soldiers “mowing down” their targets or reaching the implausible figure of “1000 kills.”

From a different perspective, the kill-count stories suggest a new genre of war journalism being created by reporters for home front consumption. The irreverence of kill-count stories is a jarring contrast with the traditional wartime tales of heroism and bravery (gunkoku bidan) mass-produced by publishers during the Manchurian Incident and the China War. Bidan usually told the story of a soldier performing a self-sacrificial act in battle for the sake of the nation with particular focus on his glorious death. The tone was invariably sentimental and serious, without a trace of humor.Footnote 85 In the kill-count reports, by contrast, the focus was not on the glorious death of the Japanese soldier, but his spectacular killing of Chinese soldiers in whimsical fashion. The media’s fixation on kill-counts both dehumanized the enemy into an abstract numerical figure and transformed battlefield violence into a modern game with outcomes easy for readers to compare, classify, and track. According to Tōnichi reporters, the two officers participating in the Hundred Man Killing Contest eventually lost count of who first reached 100 kills. Using baseball terms, reporters noted that the contest became a “Hundred Man Killing Drawn Game” (hyakunin giri dōron geiimu) and that the officers decided to go into “extra innings” (enchōsen).Footnote 86

Given the playful tone of these stories, the sexual wordplay was certainly chosen by the reporters and likely to have been recognized by readers. It was through this wordplay that Chinese soldiers were dehumanized, emasculated, and broken down into interchangeable parts signaling violence, sex, and humor. The preoccupation with the body and bodily functions recalls Bakhtin’s concept of grotesque realism – the highly exaggerated and graphic embrace of the material body and its activities during the time of carnival. Grotesque realism stresses this “degradation” of the body as a positive force reaffirming the vitality and energy of social life.Footnote 87 In a similar vein, the kill-count stories used tongue-in-cheek wordplay that breezily linked celebrations of life (sex) and death (killing).Footnote 88

The relationship between the soldier and the reporter was at the heart of the kill-count stories. The killings must be performed or said to be performed by the former and witnessed and recorded by the latter to have any cultural valence. In one instance, the Tōnichi actively assisted a soldier in finding a new sword when his weapon broke down under the strain of killing nearly thirty Chinese soldiers.Footnote 89 In the Hundred Man Killing Contest, one of the contestants invited the Tōnichi and its sister paper, the Osaka Mainichi, to judge the contest and offered to donate his prized sword to the newspapers after the game was over.Footnote 90 Therefore, unlike bidan, which were created unilaterally by either military propagandists or newspaper editors on the home front, kill-count stories were coproduced by the correspondent and the soldier on the warfront. The soldier provided sensationalized material for the reporter otherwise limited by censorship rules. The reporter, in turn, granted the soldier public acclaim at home for spectacular battlefield exploits. Nearly 40 years after the event, one of the Tōnichi reporters covering the Hundred Man Killing Contest recalled the following:

I remember we were getting ready for a tent encampment that night there. M. and N. officers saw the newspaper flag we hoisted up and came over. I remember they asked, “Hey, are you guys Mainichi Shinbun?” and a conversation began. They said that because their unit is the smallest unit, they expressed dissatisfaction somewhat that their brave battle exploits have not been reported in newspapers back home. They talked about how the soldiers on the frontlines fought so bravely in high spirits. Now I don’t recall the various tales they told, but among them was the story of a contest plan of martial exploits (bukō) that was young officer-like (seinen shōkō rashii), and that they were planning, the “Hundred Man Killing Contest.” Among all the war tales we heard, we selected this contest idea. We then added and telegrammed this idea toward the end of that day’s many war progress articles. This was the first report of the “Hundred Man Killing Contest” series.Footnote 91

In return for publicizing their exploits, soldiers would also help reporters gain a better sense of the shifting warfront. Field commanders normally tried to keep the press “two or three kilometers behind the frontlines,” thereby making it difficult to cover the latest troop movements. However, frontline soldiers came to the rescue by burning local Chinese homes to signal to reporters back at headquarters where the frontline had moved that day. The reporters would see the smoke from a distance, then correlate the rising smoke in the horizon with a map to determine the new location of Japanese units.Footnote 92 The reporter was thus not simply a neutral observer of the news, but fulfilling his new wartime role of covering and creating the news for the home front.

While carnivalized grotesquerie rendered the male Chinese body as an eroticized numerical abstraction, in a slightly different way, the female Chinese body also became the object of intense scrutiny in Japanese wartime media. (See figure 1.2) During the Battle of Shanghai in October 1937, in the otherwise serious intellectual journal Chūō Kōron (Central Review), the writer Inoue Kōbai wrote an article called “Erotic Grotesque Notes on Chinese Lewdness.” Below a drawing of an exotically dressed Chinese woman with slanted eyes and a face half-obscured by mysterious shadows, Inoue declared that the biggest hobbies in China are opium- and alcohol-induced stammering, gambling, hedonism, and games. For “hedonism” (hyō), he claimed that since Chiang Kaishek’s New Life Movement was launched in 1934, Chinese cities were now overrun by the proliferation of movie stars and dancers moonlighting as “street girls” (sutoriito gāru) who would extort money from male customers in restaurants and cafes. “Ill-mannered women of all sorts are allowed in China,” he observed, “which has many feminists (feminisuto).” Inoue disapproved of the recent popularity of the qipao dress in China for suggestively accentuating the female figure. He noted that they were mostly worn by “girl students and floozies (baita)” and that all women were now sporting short hair. “Spiritually and materially, they have thrown away the strong points of their country,” Inoue lamented.Footnote 93

Figure 1.2 “Erotic Grotesque: Notes on Chinese Lewdness.” Chūō Kōron (October 1937): 350.

A few months after the fall of Nanjing, in the March 1938 issue of Gendai magazine, the novelist Muramatsu Shōfu opined that although Nanjing women dressed plainly with little makeup, “underneath, in their underwear and lingerie, they wear more flamboyant, risqué things … with an even more suggestive effect.” He explained to readers that most Shanghai women were prostitutes while Guangzhou, “the city of the bizarre” (ryōki no tokai), was famous for blind prostitutes who could “satisfy bizarre local tastes.”Footnote 94 In November and December 1937, the Tōnichi reinforced this gendered depiction of China as a vulnerable, erotic, feminine creature with such sensational headlines as “China Finally Screams” (Shina, tsui ni hime wo agu) and “the Moans of Nanjing’s Annihilation” (Nankin shimetsu no umeki).Footnote 95

There was a particular Japanese media obsession about the Chinese army being filled with women masquerading as soldiers, thereby suggesting that Chinese soldiers represented a kind of perverted gender. According to Sayama Eitarō, writing in Fuji magazine in October 1937, there were Chinese female soldiers (onna no heitai) who “quite bravely serve as platoon or company commanders.” He described these women’s primary mission to teach Chinese soldiers “anti-Japanese thought.” But at other times, he claimed, “in the camps, they perform erotic services (ero sābisu) for the senior officers.” In their “handbags” (hando baggu), Sayama continued, the female soldiers kept “medicine, needle and thread, egg cream (depilatory), and strange sexual tools (myō na seigu),” in addition to “three to four love letters (rabu retā).”Footnote 96 In October 1937, Tokyo Asahi reporters found that retreating Chinese soldiers redoubled their efforts after encouragement from “two hundred young, short-haired female soldiers.” The Chinese male soldiers leapt over trenches to throw grenades at the Japanese camp, before going back to the female soldiers.Footnote 97 In November 1937, the Tōnichi reported that there were “frequent appearances of female troops (jōshigun) near Shanghai who would gain the following of Chinese soldiers in camp with amorous tactics (momoiro senjutsu).” After a brief battle, soldiers from the Ōno Unit were shocked to learn that their now-slain opponents were actually female soldiers, “with the same clothes as that of male soldiers except for a blue woolen knit hat. Scattered next to the corpses were invariably gramophones and records of Chinese pop songs.”Footnote 98

The idea of eroticized Chinese female soldiers was even taken up in a January 1938 routine by the male–female comedy duo Azabu Shin and Azabu Rabu, which was printed in Yūben (Eloquence) magazine:

Azabu Shin: Do you know about the female army (jōshigun) in the Chinese military called the Thank You Unit (irōtai)?

Azabu Rabu: What’s the Thank You Unit?

AZABU SHIN: As the name implies, it’s a “thank you” unit (irotai). In popular parlance, we would say it’s an erotic unit (erotai).

Azabu Rabu: What do you mean by “erotic unit?”

Azabu Shin: That is, they go to where the Chinese soldiers are on the frontlines and fully give their all (shikkari yatte chōdai yo). With that being said, they do various kinds of services (iroiro to sābisu).

Azabu Rabu: Then what?

Azabu Shin: Chinese soldiers love women. So their spirits are lifted when they hear the women’s seductive voices, and they rush out of the trenches. Then our military’s machine guns go bang, bang, and shoot them down.

Azabu Rabu: That’s a really weird battle tactic.

Azabu Shin: In this war, there’s a lot of weird tactics.

The comedians are making a word pun of irō (recognition of services) which sounds similar to iro (sensuality or lust), ero (erotic), and iroiro (various). Accompanying the printed comedic routine was an illustration of a young woman with bobbed hair and high heels, stylishly posing in a tight fur-lined black dress that exposed her breasts, while holding a cigarette. Around the woman are uniformed Chinese soldiers excitedly sniffing her dress or admiring her figure, while in the background other soldiers are shown rushing off to battle, armed with rifles.Footnote 99 These stories were most likely fabricated pieces designed to ridicule the Chinese military but also reflected the desire of reporters looking for the next bizarre or sensational story. Like the highly charged interplay woven into kill-count stories, these reportage accounts of Chinese women tied together ideas about the body, violence, and humor as part of a greater media transformation of war into a product for mass consumption.

Playful humor, killing, and wordplay were also found next to the Hundred Man Killing Contest story from early December 1937, in a long article entitled: “Such Interesting Colors at the Front! A Unit Full of Variety (baraietii). Policeman in Entertainment Trio. Unit Commander is Priest. An Instant Prayer for a Slain Enemy Soldier. A Whole Year’s Worth of Combat Standup Material.”Footnote 100 The article profiled a Japanese unit made up of three unlikely comrades – a policeman, a priest, and a manzai comedian. Matsudaira Misao, the comedian, tells the reporter the following “un-manzai-like mandan” story:Footnote 101

The story begins with the Jiading to Taicang offensive … outside Taicang [i.e., during the march from Shanghai to Nanjing], a regular soldier holding a hand grenade was captured alive. At that moment, Sergeant Gotō showed off his police training by cleanly finishing off [the soldier] with one stroke of the sword. Watching this was Sublieutenant Harada who, under his military uniform, fiercely aspired towards Buddhahood. He took out rosary beads from his pocket and, right then and there, said a sutra with all due ceremony. That night at Taicang, the three of them set up a bathtub and happily got inside. Later they discovered that the tub was not a water jug … but a vat for toilet use. At that moment, Private Matsudaira roared with a dodoitsu poem, “Gazing at the moon from the bathroom window, our luck sure ran out (benjo no mado kara, otsuki sama wo nagame, kore ga honto ni un no tsuki).”

Matsudaira’s joke here makes two puns. In Japanese, the word un means both “fortune” and human feces (written with different characters but the reporter wrote the words in ambiguous phonetic script). Furthermore, the expression “bad luck” or “bad break” in Japanese is un no tsuki. Tsuki can mean “moon” as the first part of the joke implies and also a verb meaning something coming to an end, again with different characters used. The intricacies of the punning aside, this rapid-paced narrative casually intermixed violence (slaying a captured Chinese soldier for show) with ersatz religious piety (giving an “instant prayer” for the soul of the slain Chinese) and lowbrow bathroom humor (mistaking an oversized chamber pot for a bathtub).

The confluence of uneven censorship and the powerful market pressures on reporters to hunt for speed and thrills created a loosely structured environment in which carnival war flourished. Stories of grotesque violence, couched in playful humor and silliness, had little to no strategic significance or meaningful commentary on the politics of the war, so they avoided the watchful eyes of military censors. The killing contest stories, for example, usually appeared in the arts and entertainment section, behind the sports page. They frequently shared space with other stories featuring local units placed in dangerous, comical, or bizarre situations on the front, such as the “unit full of variety.”

The celebration of the grotesque through all these stories signaled the growing carnival energies surging through wartime mass culture. But it is also connected to the specific moment of late November to early December 1937, when the military campaign escalated from urban street-fighting in Shanghai to the siege of Nanjing. During those fateful weeks, kill-count stories and other bizarre reports began appearing with greater frequency in the pages of Japan’s largest newspapers as the “speed” of modern life swept into the media frenzy and accelerated the hunt for “thrills.”

“’Tis the Season for the Fall of Nanjing!”

From August to early November, the Battle of Shanghai became a stalemate with the Japanese side sustaining casualties of 9,115 deaths and 31,125 wounded. The stalemate was broken on November 5, 1937 when the Tenth Army made a surprise landing at Hangzhou Bay behind Chinese lines and forced Chinese soldiers to retreat to Nanjing. On November 7, General Matsui Iwane amalgamated all field armies into the Central China Area Army (CCAA) under his command to pursue fleeing Chinese troops. The Japanese Army and Navy in Tokyo belatedly established the Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) on November 20 to centralize and coordinate wartime strategy. The IGHQ ordered the CCAA to stop the advance and regroup near Lake Tai to await further instructions. However, CCAA frontline units ignored the demarcation line and pushed forward to Nanjing, followed by war correspondents.Footnote 102

Among the reporters embedded in the units racing to Nanjing was 28-year-old Asami Kazuo from the Tōnichi. Asami represented the ideal reporter for wartime; a young man in his late twenties who had attended elite Waseda University before joining the Mainichi newspaper company (parent company of the Tōnichi) in 1932.Footnote 103 Asami typified the youthful vigor and learned professional background of the reporter particularly sought after by intellectuals and journalists on the home front. During the march to Nanjing, on November 30, Asami and several colleagues wrote the first story about a “Hundred Man Killing Contest” (hyakunin giri kyōsō), recording that Sublieutenants Mukai and Noda already reached 56 and 25 kills respectively. The Tōnichi reporters interviewed Mukai and Noda during a break from campaigning at Changzhou Station:

Sublieutenant Mukai: I’ll probably kill about 100 by the time we get to Danyang, let alone Nanjing. My sword cut down 56 and was only nicked a little, so Noda will lose.

Sublieutenant Noda: We’ve decided that we won’t kill those that run away. I’m working at the [censored]-office so my results won’t go up, but I’ll show a big record by the time we reach Danyang.Footnote 104

The next day, on December 1, the IGHQ authorized a full-scale assault on Nanjing but instructed the units to march in orderly stages. The plan was for all units to regroup at a closer location, and then launch a united general assault on the city, thereby avoiding a chaotic, haphazard campaign. But the CCAA’s Shanghai Expeditionary Force and the Tenth Army ignored the plan and moved straight toward Nanjing city walls ahead of schedule.Footnote 105 Japanese newspapers excitedly covered their race to Nanjing and the imminent capture of China’s capital city. On December 3, the Tōnichi announced, “Nanjing, now at hailing distance.” The next day, the Tōnichi printed a second story from Asami and his colleague Mitsumoto which reported that Mukai was up to 86 kills, while Noda had 65 kills. The correspondents caught up with Mukai at the now-conquered city of Danyang:

My man Noda is no blockhead because he’s really catching up. Don’t worry about Noda’s cut. It’s not serious. Because of the bones of the guy I killed at Lingkou, there’s a nick in one place on my Magoroku. But I can still kill 100 or 200 men. You guys from Tōnichi and Daimai [i.e., Tokyo Nichinichi and Osaka Mainichi] can be the referees.Footnote 106

By December 6, as thousands of Nanjing residents fled into the “Nanjing Safety Zone” set up by Westerners in the city, Asami’s third report on the killing contest appeared in the Tōnichi. He noted that the competition had become a “close contest,” full of “bravery” with Mukai at 89 and Noda at 78.Footnote 107 The following day on December 7, Chiang Kaishek and his government officially evacuated Nanjing for Hankou.Footnote 108

As media excitement intensified over Nanjing’s imminent capture, army officials began to complain about the media coverage. On the evening of December 6, at the Army Ministry’s annual press club gathering, army press officers rebuked journalists for over-sensationalizing the fall of Nanjing: “All this raucous carnival is troubling” (omatsuri sawagi) said one unamused officer. The army urged people to exercise more “self-control” in the festivities and go pray for the war dead at Yasukuni Shrine. Whether the Tōnichi reported this story with a straight face is unclear, especially since its account gratuitously mentioned that the press club dinner menu had been, ironically, “Chinese food” (chūka ryōri).Footnote 109

On December 9, General Matsui issued an ultimatum to remaining Chinese forces in Nanjing to surrender. When the deadline passed on the following day with no response, Matsui ordered all CCAA forces to begin the general assault on the city walls.Footnote 110 By the evening of December 10, a military telegram had arrived in Tokyo announcing that Japanese soldiers were now mopping up the enemy within Nanjing city walls. The telegram created an excited uproar in Tokyo, as explained by the Tōnichi with a hint of sarcasm at the end:

The attention of all citizens is focused on this one point in newspaper extras and radio. Excited hearts from all over the country are beating faster and faster … today especially, in the imperial capital, an explosion of cheers and Japanese flags buried underneath the waves of fire from the lantern processions. But we must not forget the officials’ attitude to “avoid raucous carnival” and try to go to shrines to commemorate the spirits of the war dead.Footnote 111

After repeating the military’s buzzword of “raucous carnival,” the Tōnichi reporter went on to describe the night’s commotion from the telegram. Tokyo residents flooded the Army Ministry Newspaper Group office with phone calls asking, “Did Nanjing really fall?” Meanwhile, journalists at the Army Ministry headquarters pressed officials on when a formal telegram announcing Nanjing’s conquest would be released. A beleaguered Lieutenant Colonel Hayashi promised that “as soon as the official telegram arrives, I will make an announcement.” The unsatisfied reporters remained at the ministry late into the night to await more answers. The atmosphere was so chaotic that the reporter overheard an excited office boy happily declaring, “Tonight, I’m staying,” before pulling out a chair and blanket to settle in for a long night.Footnote 112

The formal issuance of surrender terms by General Matsui on December 9 and the official authorization for a full-scale assault on December 10 were somewhat lost in the growing media excitement over Nanjing’s capture and the presumption by reporters that the campaign had already begun. Although the national dailies all covered the Nanjing campaign with fervor, the Tōnichi was the most aggressive in its coverage. After years of falling behind the Asahi and Yomiuri in circulation, the Tōnichi suddenly soared to the top of the newspaper world during the China War by boldly injecting “loud and flashy” elements in its war coverage. The newspaper slyly invented its own scoops by simply attaching the qualifiers “virtually fallen” (jijitsujō kanraku) and “completely fallen” (kanzen kanraku) to maximize the number of breaking stories it could report. On December 8, the Tōnichi released the headline, “Nanjing – Virtually Fallen: Enemy Forces Routed, Offensive Suspended, Outside of City, Leisurely Awaiting Entry.”Footnote 113 The Tōnichi never seemed to lack vigor during the Nanjing frenzy. According to one anonymous critic, “the Tōnichi put out an extra on the evening of December 7, saying, ‘Nanjing – virtually fallen.’ The Tōnichi is very adept at making gullible people … they make people think that ‘Hey, Nanjing has fallen!’”Footnote 114