Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of tables and figure

- List of abbreviations and transcription conventions

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Multiple approaches for a complex issue

- 3 Contextualising address choice

- 4 Institutions, domains and medium

- 5 National variation

- 6 Conclusions

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- References

- Index

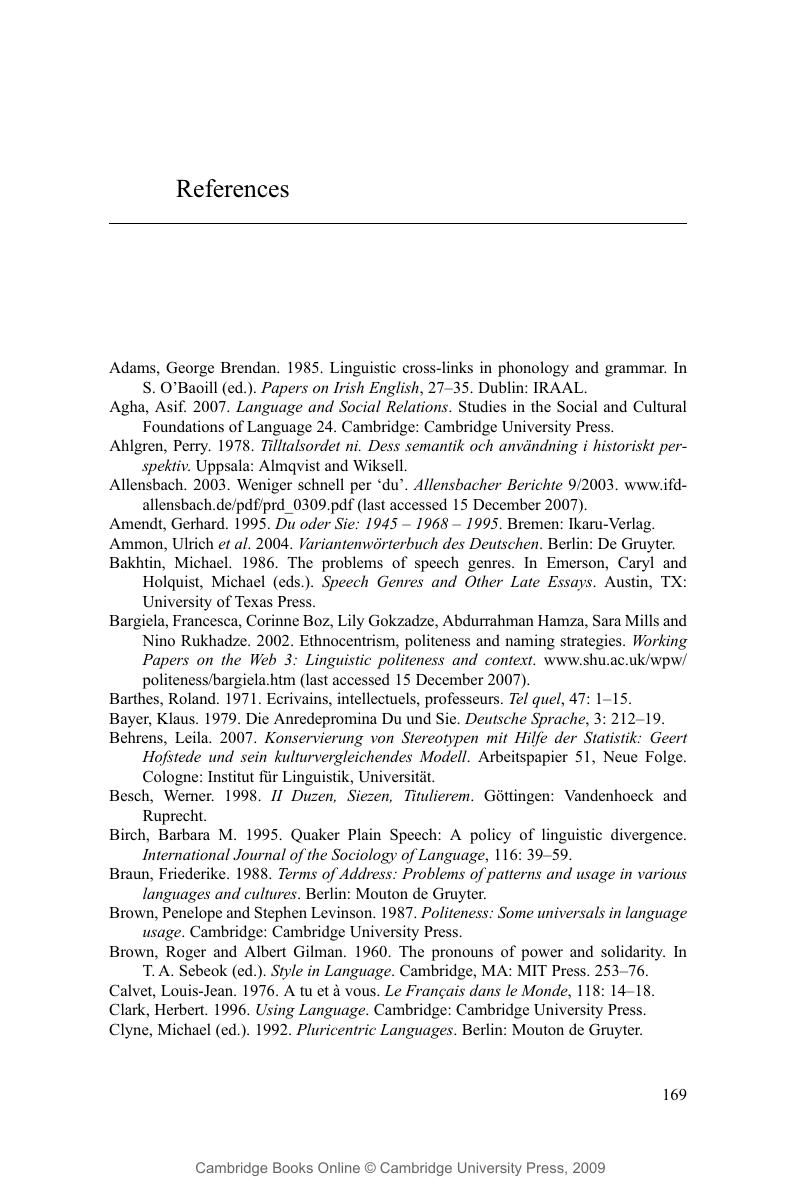

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of tables and figure

- List of abbreviations and transcription conventions

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Multiple approaches for a complex issue

- 3 Contextualising address choice

- 4 Institutions, domains and medium

- 5 National variation

- 6 Conclusions

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Language and Human RelationsStyles of Address in Contemporary Language, pp. 169 - 176Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2009