The first of the two sonnets quoted in the epigraph to this chapter is addressed “To the Author of Clarissa” and has, since its publication in 1750 with the third edition of that novel, served as testimony to the sociable literary relationship between one author, Thomas Edwards, and another, Samuel Richardson. The second sonnet, from the same pen and equally warm in its praise, similarly celebrates a sociable literary relationship, but one less readily recognizable to the historian of eighteenth-century literature. It is addressed to a young married couple, to Philip Yorke, son of the first Earl of Hardwicke, then Lord Chancellor of England, and his wife Jemima, Marchioness Grey, then aged twenty-four and twenty, respectively. If Richardson’s accomplishment was that he had combined “wit, strength, truth, [and] decency” in his fiction in order “to lead our Youth to Good, and guard from Ill,” Yorke and Grey were those young people; unlike “other youths, sprung from the good and great” who might become “meanly debauch’d, or insolently vain,” they would show “degenerate Britain, what the great should be.”1

Philip Yorke and his wife, like Samuel Richardson, centered a literary coterie in the middle decades of the eighteenth century; indeed, the Yorke–Grey coterie prefigured that of Richardson by about a decade. The earlier group, operating primarily by means of scribal circulation and restricted publication, has been largely invisible to literary scholars, while there has been considerable discussion of the various circles surrounding Richardson by virtue of their relation to his novels. Paradoxically, in mid-eighteenth-century England, it was the Yorke–Grey group that possessed the visibility and prestige, providing a model for the sorts of sociable literary ideals Richardson himself sought to enact at the height of his fame. In this chapter I will first bring the Yorke–Grey coterie into view, profiling its character and influence, and then turn to the short-lived Richardson–Highmore–Edwards–Mulso coterie as a case study of how a denizen of the London print trade might engage in the practices of scribal literary culture. I will conclude by demonstrating the fame attained by the young writer Hester Mulso in the 1750s through these scribal networks.

The Yorke–Grey coterie, 1740–66

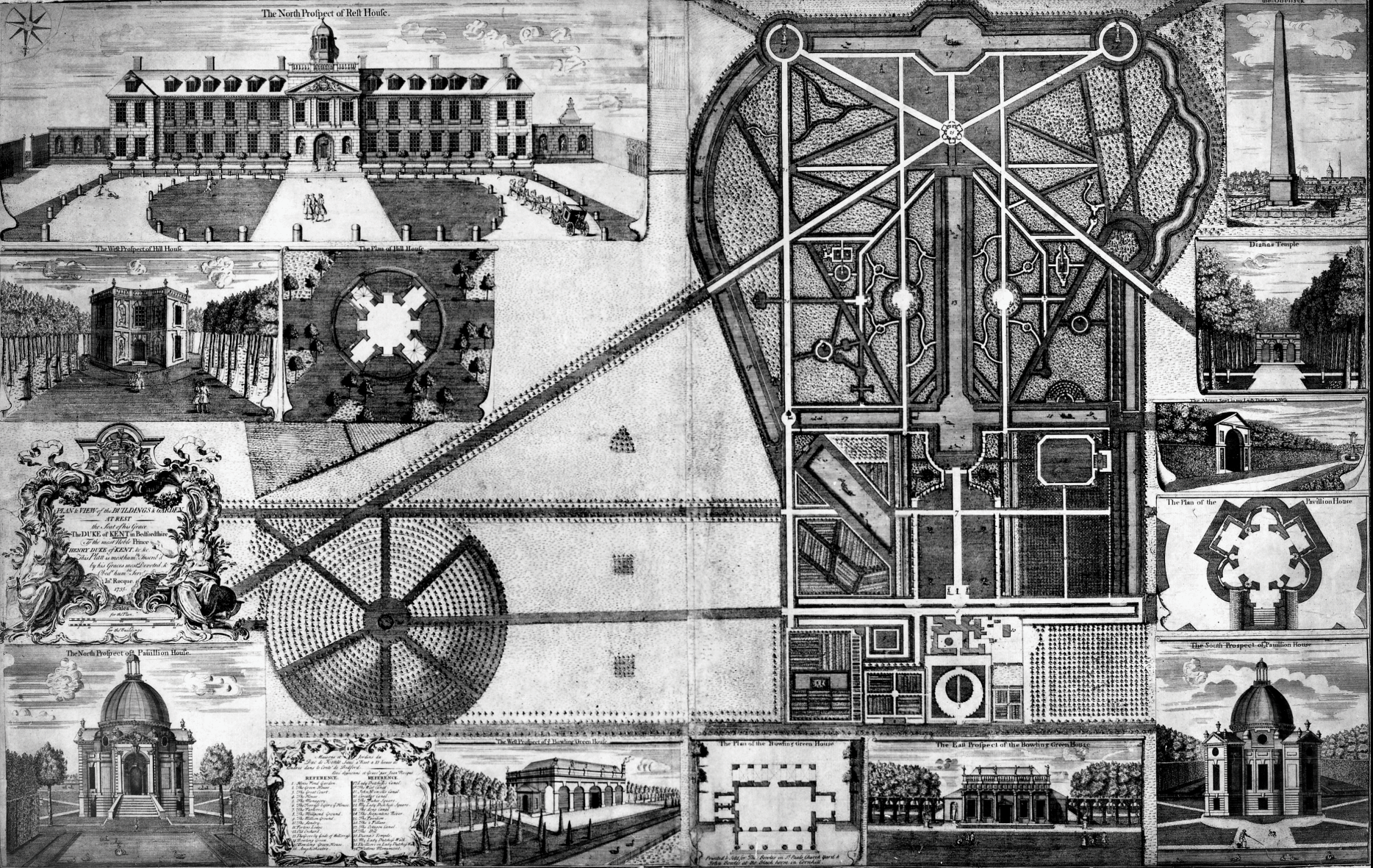

The brightest coterie constellation on the cultural horizon of the 1740s was centered upon the newlyweds Philip Yorke and Jemima, Marchioness Grey, heirs to two of Britain’s wealthiest and most prominent Whig families. As the eldest son of Chancellor Hardwicke, Yorke held the lucrative sinecure of Teller of the Exchequer, in 1741 was elected Member of Parliament for Reigate, in 1754 was created Lord Royston, and in 1764 inherited his father’s title and became high steward of Cambridge University. While at St. Bene’t’s or Corpus Christi College at Cambridge, Philip and his brother Charles, both intelligent young men with strong literary interests, gathered around themselves a number of “wits” with shared interests. But it was in 1740, when at the age of twenty Yorke left Cambridge to marry the seventeen-year-old Jemima Campbell, that this cluster of friends gained a social and geographical center and became a recognizable coterie. Campbell was the granddaughter and principal heir of Henry Grey, the Duke of Kent, who at the end of his life arranged both for her marriage and for her to become by royal decree the Marchioness Grey. Informally educated, she was nevertheless, as the remains of her youthful correspondence indicate, witty, inquiring, and widely read in the classics (in translation), French literature (including romances), history, and theology.2 The Duke of Kent’s principal seat had been the Bedfordshire estate of Wrest Park. Although Joyce Godber notes in her biography of Grey that the Marchioness inherited Wrest encumbered with debts and that the couple did not immediately reside there,3 from 1743 the estate with its great house, library, and garden walks was the principal focal point of sociable literary life for their combined circles (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 John Roque’s Plan of Wrest Park, 1735, illustrates features of Wrest Park as it appeared when Jemima, Marchioness Grey, inherited it. Thomas Edwards refers to this plan in his letter to Philip Yorke dated August 10, 1745, quoted below.

This was an alliance not only of powerful families and fortunes but of two bookish individuals who had already formed active, homosocial literary connections in their adolescence. For Yorke, these connections were developed through family, including older men who had received patronage appointments from his father, and friendships from Hackney School and Cambridge. At the time of his marriage, the inner members of this circle were his brother Charles (“the Licenser”); John Lawry, a Cambridge friend; Samuel Salter, the Yorke brothers’ tutor at Cambridge; and above all, Daniel Wray, from 1745 Philip’s deputy teller of the exchequer, but initially a man of antiquarian and literary pursuits based at Cambridge who had attracted the patronage of the first earl. Wray, referred to by one of the group as “the delight of every Man among us,” clearly was fundamental in generating both “mirth” and composition in the group. The Hardwicke correspondence in the British Library is full of his schemes, from Lawry reporting that “the incomparable Bearer of these Tablets [i.e. Wray] who is all things to all Men … has set your humble Servant during his leisure here … at Rochester upon cultivating Hebrew Roots,” to Yorke recounting proposals to “[throw] out one Number of a Grubstreet Literary Journal” and to erect a Mithraic altar in the gardens at Wrest.4 For Grey, the women of her family were even more key to her intellectual development – before marriage, her core group consisted of Lady Mary Grey, the aunt three years her elder with whom she had been brought up, and Catherine Talbot, whose guardian Thomas Secker, as Bishop of Oxford and rector of St. James, Picadilly, had informally overseen care of Jemima and Mary when they resided in London as adolescents. With Grey’s marriage, Philip’s sister Elizabeth Yorke (later Lady Anson) became part of this inner circle, as did, to a lesser extent, his younger sister Margaret. The coterie was shortly also to gain two key new members: Thomas Birch, a London-based historian, biographer, and clergyman who had already been serving Lord Hardwicke in various capacities, and Thomas Edwards, a legally trained country gentleman and longtime friend of Wray who had recently settled on a modest farm at Turrick in Buckinghamshire.5 Along with Catherine Talbot, both feature importantly in the story of this circle and its influence.

The Yorke–Grey coterie was thus traditional in many respects in its social foundations – its basis in kinship and friendship relations, its mix of elites and clients of more modest status, and its coalescence around a geographical center, Wrest, where Philip and Jemima entertained guests constantly through the months of May to September. The importance of Wrest to Jemima Grey, and by extension to the coterie which she and her husband anchored there, is captured in her letter to Lady Mary Grey, written in the spring of 1743 upon reoccupying her childhood home as its mistress:

My Attachment to this Place is by no means lessen’d by above Three Years Absence, for so long I must call it, since the Time I have seen it between has been but as a Stranger, & have [sic] convey’d a lively Pleasure indeed but a very mix’d & short One. – But it is now again my Home. It is not only returning to the Country & a Country-Life (which I love everywhere) but in the only Place I am fond enough of to make those Words peculiarly charming, to the only Place that can heighten my Enjoyment of my Friends, & to that Place where I hope soon to see you.

In a letter written from Wrest almost a decade later, Talbot similarly captures this combination of natural, social, and literary pleasures associated with the place, describing it as “an enchanted Castle” of “absolute unquestioned liberty. The most delightful groves to wander in all day, and a library that will carry one as far as ever one chuses to travel in an evening.”6

Literary life at Wrest is also recognizable as that of a traditional coterie: correspondence between those at Wrest and distant friends records daily communal reading, critical discussion of contemporary publications or genres such as satire, and a veritable outpouring of occasional poems, imitations, and parodies – of Horatian odes, Miltonic sonnets, Italian comedy, Young’s “Night Thoughts,” Crébillon “novels,” and so on – stimulated by the shared reading and generally in response to relations between members of the group, or to current political and literary affairs. Visiting Wrest in May and June of 1745, Talbot kept a journal which offers a valuable glimpse into this way of life: on the evening of her arrival, for example, the assembled group is occupied in reading “Humorous Manuscripts of theirs full of Wit & Entertainment”; on the third day, knowing she will be called to account for her time, she records “Writ two Sonnettos (abusive) in five Minutes & produced as my Evenings Work. At the instigation of A. [Angelina, her coterie name for Grey] writ a third before Supper,” in answer to one addressed to her by Charles Yorke; on day five, she copies figures out of Raphael’s Bible while Angelina reads Locke aloud.7 As chief “patron” of the group, Yorke, often aided or instigated by Wray, set tasks and proposed literary projects to other members.8

Also typical of a coterie ethos was the restricted access to the literary activity and productions of Wrest – called “Vacuna” by its initiates, after an ancient Sabine goddess associated with rural life. The correspondence records both the efforts of outsiders to gain glimpses of circulating materials and the enthusiasm and gratitude of those who were invited to Wrest and shown its literary compositions. When at last invited there in 1743, after envious comments to his good friend Wray about the pleasures of that select society, Edwards finds himself unable to accept for a number of practical reasons but chiefly out of diffidence; two years later, having become a member of the Wrest circle at last, Edwards writes in a letter of thanks to Yorke:

I make You many mental visits, as Sir Mars in the Toast fights mental battles, for I have the plan of Wrest (Rocque’s I mean, not that after Mr Wright) hanging by my bedside, there I frequently morning and evening pace over the gardens and cast a look at the Library, recollecting the pleasant hours I have spent in the most agreeable company whom I cannot describe better than in your Horace’s words Animæ quales neque candidiores etc.

Writing to Wray of the desire of Richard Owen Cambridge, another mutual friend and wit, to be included in the “Wrestiana,” a compilation of coterie manuscripts kept at Wrest, Edwards says, “I do not wonder at Cambridge’s ambition to get into the Wrestiana, it is a Templum Honoris, and a Niche there of equal value with an Olympic Crown.”9

At the same time, several features unique to the Yorke–Grey coterie contributed to its profile and appeal to individuals such as Edwards. One of these was the combination of youth, privilege, and talent at its core, creating a sense of promise on the cusp of a bright political, social, and cultural future and thereby making association with it highly desirable. Yorke and Grey seem to have been unusually mature for such a young couple. Talbot’s 1745 Wrest journal records with admiration the good order and hospitality of the household: Yorke leads family prayers at eleven every evening, and Talbot’s entry for June 9 notes of the mistress of the house, “how great is your [Grey’s] Merit & yet how quiet & silent. While she regulates every thing one always finds her disengaged & easy, as if she had nothing to do or think of.” In Edwards’ perspective, “the Conversation, and the way of spending their time are what one seldom meets with among the Great; their regular hours, and temperate meals, may set an example to most private families.”10 Even accounting for a certain element of flattery and deference in letters to Yorke, correspondents demonstrate an expectation that he will become a leader in the world of letters, perhaps a great author himself. John Lawry in 1740, for example, speculating that Yorke may have changed printers, parallels him to the most prominent writers of the century to date: “very likely to encourage a young beginner [Mr. Harris] you have procur’d that Gentleman a Patent that He & no one else for such a term of years shall print the Philosophers only. thus Addison & Steele encouragd Tonson, & Pope was in some measure the making of Bernard Lintot.”11 Yorke and his brother Charles, assisted by Wray, apparently felt this cultural responsibility; while no doubt indulging their own predilections, they encouraged and supported the creative and critical projects of others. Thus, they were sought out by both older men and young contemporaries such as Conyers Middleton, William Warburton, George Lyttelton,12 Isaac Hawkins Browne, Richard Owen Cambridge, and Soame Jenyns, often to serve as dedicatees, support subscription publications, and lobby for antiquarian causes; while Yorke occasionally declined for reasons of political sensitivity, and while he asked on at least one occasion that a pseudonym be used on a subscription list, the correspondence record, again, indicates that such requests must have come with some frequency and were treated graciously. An overriding interest of both brothers was the preservation of the manuscript materials that were the repository of Britain’s history; their personal efforts and their support of the many antiquarians who were collecting, transcribing, and epitomizing such materials played a role in the founding and early years of the British Museum, as I will elaborate below, and in the great flowering of history-writing in the eighteenth century.

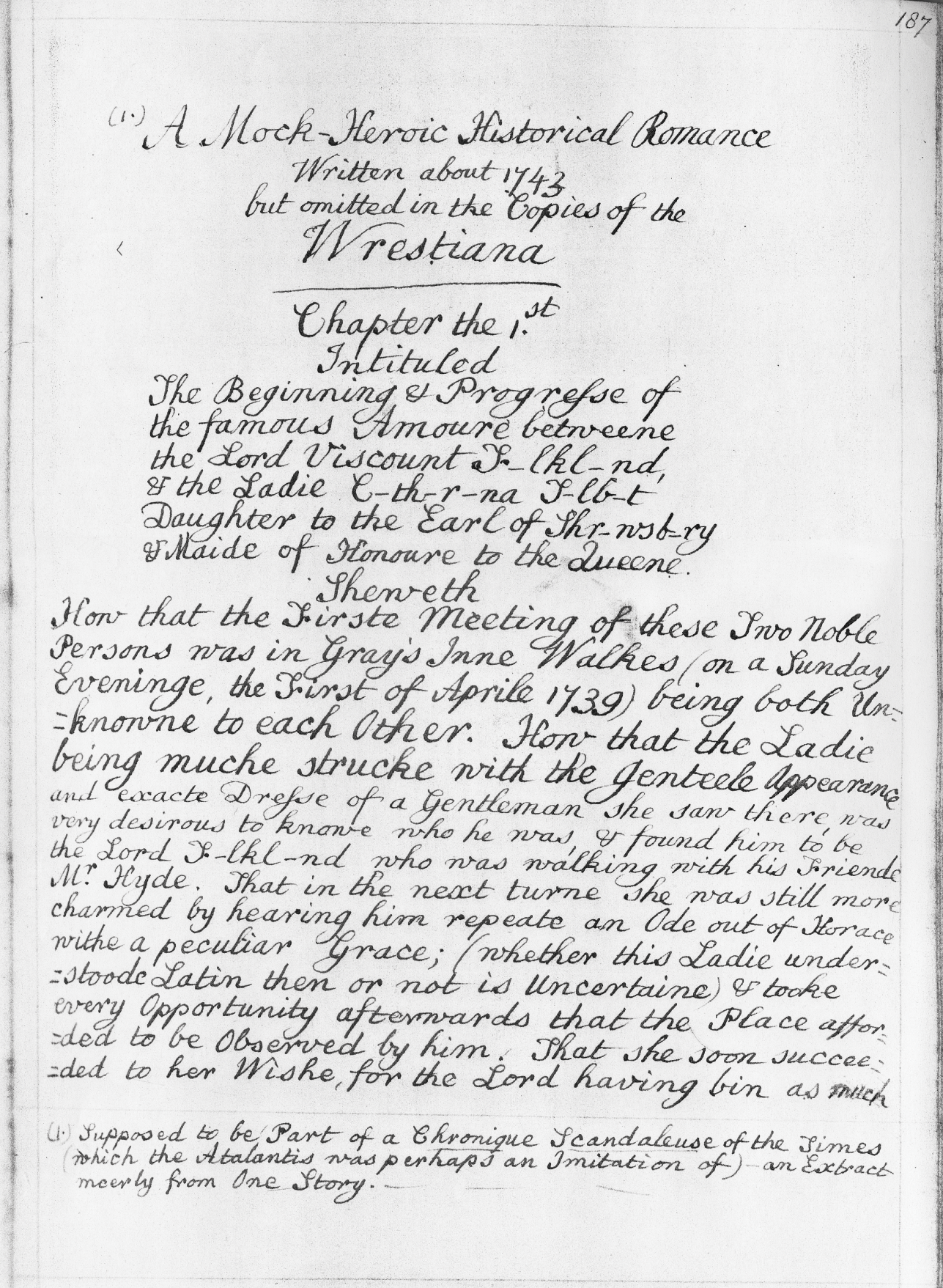

A second distinguishing feature of this group was its mixed gender. Thomas Edwards, for example, found remarkable the centrality of Jemima and her female friends to the literary as well as the sociable life of Wrest, reporting after his first visits there: “The Library is the general rendezvous both for the Ladies and Gentlemen at their leisure hours; hither the Ladies bring their work, and here if there is no company, they drink Tea”; ever the enthusiast for the place, he later writes to Wray, “I am indeed surprised at the Lady [Grey], so superior not only to her own Sex but to most of ours. I entirely agree with You that that Alliance is one of the greatest happinesses of that happy House; I envy every body in proportion to their acquaintance with it, and regret nothing in my own circumstances so much as that they allow me no more of it.”13 Among the inner circle, Talbot in particular commands the respect of a literary equal, as indicated by her nickname of “Sappho,” by her role as the only female contributor to the Athenian Letters, discussed below, by Charles’s game of matching sonnets with her, and by group jeux d’esprit such as the mock-heroic romance captured in Figure 1.2, taken from a facsimile copy of the “Wrestiana.” Another of these, a mock-epic titled The Borlaciad, ends with Talbot as heroine rewarded by academic honors at Oxford and by “a Long Line of … Posterity” that includes “Generals, Wits, Deans of Ch[rist] Ch[urch], Poetesses, Bishops, Royal Mistresses, Emperors, & Pope Joans.”14 While earlier feminocentric coteries such as that of Longleat, centered on the Duchess of Hertford (later Somerset) and nurturing writers such as Elizabeth Singer Rowe, were renowned in their own way, this meeting of literary cultures that were often quite strictly divided along gender lines was noteworthy and flavored the coterie’s productions, particularly in its first decade.

Figure 1.2 Wrestiana, “A Mock-Heroic Historical Romance,” p. 187 (facsimile reproduction), featuring “the Ladie C-th-r-na T-lb-t.”

Finally, the feature of this coterie that perhaps most reflects its moment in the history of letters, and indeed its importance for this study, is its articulation with the London print trade. While key members of the group, such as Talbot, were extremely ambivalent about allowing their work to enter the print medium, the coterie as a collective made selective and self-conscious use of print, for everything from anonymous letters to the public, to forged Elizabethan newspapers, to its own in-house productions, to editions of diplomatic papers. It thus represents the kind of adaptive intermediality that is characteristic of mid-eighteenth-century manuscript cultures as well as of the authors, presses, and booksellers on the print side of the exchange. Key to this integration was Thomas Birch, whose status as an oddity of sorts in the Yorke–Grey circle made him a bridge between the two worlds; as the language of network theory would put it, Birch brokered information across the “structural hole” that divided the values and assumptions of his Wrest friends from those of the London print trade.15 Indeed, some of his exchanges with Yorke are nothing more or less than exercises in translation. Other individuals, however, served similar bridging functions: Catherine Talbot’s connection, along with those of Edwards and Birch, with the Richardson coterie will be discussed later in this chapter. Before examining the Birch–Yorke relationship and then turning to the Richardson coterie, however, I will use a collective production – the Athenian Letters – to demonstrate the fame and influence that could be achieved by a coterie publication and to initiate a fuller discussion of the distinctive coterie features I have been enumerating.

The Athenian Letters and the influence of the Yorke–Grey coterie

The most noted production of the Yorke–Grey coterie came to fruition in the early 1740s with the private printing of twelve copies of the four-volume Athenian Letters, or, the Epistolary Correspondence of an Agent of the King of Persia, Residing at Athens during the Peloponnesian War, published in 1741 (three volumes) and 1743 (a final volume).16 A collection of epistles purportedly written by one individual, Cleander, the work represents carefully researched customs, attitudes, and mores in the form of diplomatic dispatches. A collaboration of the Yorke brothers, Wray, Lawry, Salter, Talbot, and seven others, the Athenian Letters were conceived at Cambridge but the final compendium reflects the group formed in the early 1740s. The collection was loosely planned and vetted by a “Committee”17 (probably the Yorke brothers and Wray), with Thomas Birch serving as London editor preparing the manuscript for the press. Especially notable are the four letters composed by Talbot as the only female contributor and one by Birch, who quickly gained the respect and appreciation of the collaborators and was led to offer a piece of his own.18

A candid and insightful outline of three functions of the project is provided retrospectively by Lawry, who, regretting its completion, writes in 1743:

Before the book of the Athenian Letters was closed, I believe every body was sensible of two principal good effects that flowed naturally from the undertaking first that it renderd Men ingenious who had it in them to be so, and kept their Witts in Motion. And Secondly that it kept up a correspondence between Friends. Perhaps I may go further and affirm that it gave to some Men a certain degree of importance, Who at other times are absolutely Nothing. fit only to attend to Polyp’s, to speculate upon a Flea, or seek out congenial object in the cockle kind, but not to be honoured with any Notices from those Sublime Geniuses queis Mens divinior, atqe. os. magna Sonaturum19

The collaborative generation of “wit,” the solidification of social bonds, and the prestige factor of membership in an exclusive circle – all are attractions of the coterie in a sociable literary culture. Conspicuously absent from the list of pleasures named by the various contributor-recipients as they acknowledge their copies is the simple fact of appearing in print, an omission that underscores the function of this “publication” as entirely an extension of the coterie for its own benefit.20

If the creation of the Athenian Letters typifies the practices of scribal culture, the intrigue surrounding the work’s very existence demonstrates both the contemporary interest in this coterie and the determination of its members to maintain control over its productions. The project’s printer was James Bettenham, a seasoned London veteran whom Yorke used frequently for his projects; as Birch assures Yorke, Bettenham’s “Fidelity justly intitles him to be Printer-General to the whole Class of anonymous, pseudonymous, & esoterical Writers.”21 Despite Birch’s assurances that the printing was being carried on with the utmost secrecy, he clearly underestimated the strictness of the code in this case, probably from his awareness of how often the coterie writer’s injunction against circulation was more of a modesty trope than a command to be obeyed absolutely. Thus, when he reports to Yorke on September 2, 1742, that William Warburton, a close associate of Charles, has got wind of the publication, “therefore desire[ing] [Yorke’s] Leave to present him with a copy of them, under ye usual Restrictions,” consternation ensues, and Yorke responds with a lengthy articulation of the dilemma of restricted circulation in an age of print:

I freely confess to you, I am not a little vexed, that a Scheme, wch was only intended for the Amusement of a very few Friends, who from being conversant in the same Authors, were tempted to take a share in it, & from an intimate acquaintance with each other, were disposed to fall into the same turn of speculation & writing, sd thus by degrees, & almost imperceptibly, circulate wider & wider, & at last have very little wanting of a public Performance, but the form of an Advertisement in the Papers. The worst is, that the Books wch are printed, reduce one to a sad dilemma, either of disobliging Those, who have heard of the work, & think from their being known to us, that they have a claim to desire a Copy; or else by indulging them, to draw on fresh demands, & add to the Number both of Readers & Publishers. I have found by Experience, that the Usual Restrictions are of no sort of avail; such is the natural desire of telling a secret, or such the more laudable, tho not less inconvenient eagerness of Friends to do you a credit, as they think, by trespassing upon the Modesty of young Authors; & breaking thro’ prohibitions, wch they question the reality of.

Charles Yorke adds a corroborating postscript to the letter confirming that “Warburton is on no acct to be intrusted with a printed Copy,” both because of his own “friendly impetuosity” and because of “our own situation & circumstances in general.” The upshot of this close call was an order from the Yorke brothers that the three or four copies remaining after the contributors had each received theirs should be “committed to Vulcan”;22 when Birch proved reluctant to feed the fire himself, they asked him to return the remainder to them for disposal.

About six months earlier, Catherine Talbot had been under similar pressure to show the manuscript originals of the third volume of the Athenian Letters to the Bishop of Derry, whom she had “suffer’d … to peep into” an earlier volume. The Bishop played coy about the source of his information, pleaded with her to assign names to the individual pieces, and suggested that to see the documents “transcribe[d] … in [her] own hand,” “before the Press hath made them like the Laws of the Medes & Persians, irrevocable & never to be changed” would offer a special frisson of pleasure.23 In fact, the brothers ensured that even the manuscript originals were destroyed. The effectiveness of this restricted access in creating desire for the text is demonstrated for decades to come, as letter-writers comment on the privilege of having been shown the Athenian Letters at Wrest or by one of the original contributors. Edwards, asking Wray in 1743 for an account of his most recent visit to Wrest, concludes with reference to the recently published work, “I thank you for the very great entertainment I have had from the Letters, and have taken the care You desired of them in case of any accident. I envy You the situation You are in with respect to those Gentlemen, but at the same time am very thankful for the share I have in their acquaintance through your means.” For Mary Capell, daughter of the third Earl of Essex, and with her sister Charlotte a member of the Marchioness Grey’s circle of friends, reading the copy Birch has lent her is like reading a roman à clef: “I cannot help mentioning the Athenian Letters, which amuse us more than I can express: I don’t know whether any particular Person is meant by Thucydides, in the Picture of him, (or rather of his Mind, & way of thinking,) in Vol. Ye. 1t. Page 196. I have given it in my own mind, to the Late Ld Lonsdale.” Talbot shared them with her friends the Berkeleys in the long 1753 Oxfordshire summer when they became intimates.24 In the early 1780s, these references shift to requests or grateful thanks for gift copies of a work long heard about, as Yorke, now Lord Hardwicke, distributes a second edition of one hundred copies to British aristocrats, scholars, and European contacts.25 The Letters were published again in 1798 with maps and engravings and in several further turn-of-the-century English and French editions.

Since so few individuals actually read the Athenian Letters in the eighteenth century, it may seem odd to speak of the collection as influential. A common theme across the decades of commentary, however, is that it represents an ideal of civic engagement, one that ought to serve as a model in the current degenerate times of political dissension. This kind of language is prefigured in the Edwards sonnet to Yorke and Grey that stands as second epigraph to the chapter. The Duke of Northumberland writes in 1782 “lament[ing] that more attention was not paid to the very judicious and prudent advice contained in them, which in all probability would have prevented the distressed situation to which this Country is unfortunately reduced,” while Sir Grey Cooper

presents his best respects & thanks to Lord Hardwicke for his very obliging present of the Athenian Letters: He is happy that he has at present leisure to read with attention a work which made part of the plan of the Education of persons so distinguished in the world, & which seems to him to be better calculated to give a comprehensive & a lasting knowledge of any great era of History, than can be acquired by reading, or meditation merely. He will recommend the Athenian letters to his Sons when their understanding & their advancement in Learning will enable them to relish such compositions; They were indeed written in better times than the present: Letters passing between two or more of the ablest & best informed men on the History of their own times wou’d not exhibit a pleasing representation to those who remember a former period.26

In this sense the Athenian Letters might be described as contributing to the same spirit as the Roman tragedies and the calls to disinterested public service that characterized the middle decades of the century, strained as they were globally by war with France and the American colonies and nationally by continual changes of ministry and mass discontents. Such nostalgia was undoubtedly tinged by regret over a lost Whig ascendancy, as the Hardwicke family’s political power faded with the accession of George III in 1760 and the death of the first earl in 1764. Nevertheless, the elegiac orientation toward an idealized past that operates in two senses here – regret for a very distant Greek civilization and for the more recent past of a youthful coterie of promising young elites – might be fuelled even more effectively by an absent text than by a readily accessible one.

The Yorke–Grey coterie exerted a more definite, if indirect, influence on the development of one phenomenon generally associated with a sophisticated print culture: the notion of an indigenous literary history and the related idea of the critical edition. Thomas Edwards, for example, has been credited with influencing the revival of the English sonnet, but sonnets in imitation of Milton were being circulated regularly by the circle as early as 1742, and Edwards’ own first Spenserian sonnet seems to have been composed in 1744. Many of Edwards’ compositions were addressed to, amended by, and commented on by members of this group.27 Certainly, the inspiration of Wrest gave rise to some of Edwards’ most original sonnets, such as that addressed by the beech-roots of Turrick to the elm-roots of Wrest after he had spent a fortnight at the estate directing the construction of a forest dwelling made out of the latter in the summer of 1749. When Edwards innovates in another direction, turning the form to satirical purposes in his critique of Warburton and other renegade editors,28 Yorke appears to have continued to set Edwards these sorts of tasks, along with those of garden design and critical commentary.29 It was Edwards’ sonnets that were published in Robert Dodsley’s influential Collection of Poems by Several Hands (1748), but this occurred through the mediation of Wray. The set of thirteen sonnets printed there opens with the poem addressed to Yorke that serves as the second epigraph to this chapter; other Edwards poems in Dodsley’s Collection and in the later editions of his Canons of Criticism similarly honored other members of the coterie. Indeed, for Edwards, his collection of sonnets was to serve as a lasting memorial to “the friendship of worthy Men,” which “will be an honor to my memory”; he writes to Lawry in 1751, “Believe me I have often regretted that this acquisition [of Lawry’s friendship] came so late; and envy my Friend Wray for nothing so much as having had the start of me so long in the acquaintance of that ingenious sett of Gentlemen who were the Authors of the Athenian Letters.”30

The circle’s close connection with William Warburton, through Charles Yorke’s enthusiastic promotion of him, made the process of that bellicose critic’s career the subject of much discussion, with early tolerance of his personal failings giving way, perhaps under the influence of Edwards’ critical views, to a more fixed stance against his editorial methods. At any rate, stimulated by the Warburton controversies and by his discussions with the coterie at Wrest, Edwards published in print in 1748 a manifesto of modern critical principles, originally titled A Supplement to Mr. Warburton’s Edition of Shakespeare, which became, by its much-expanded third edition in 1750, The Canons of Criticism.31 The group’s collective interest in the editing of major English poets – specifically, Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton – also led to the active search for a suitable editor of Spenser and to the involvement of Birch (after Edwards had declined) as editor of the bookseller Brindley’s edition.32

Finally, Philip Yorke’s antiquarian tastes drew him to devote a great deal of attention to executing the vision of his father and others in the formation of the British Museum. As chairperson of the House of Commons committee that made the foundation of the institution possible through a 1753 Act of Parliament, Yorke led the effort to recommend to the House the purchase of the Hans Sloane collections recently bequeathed to the nation as well as the Harley manuscripts, to be combined into one national repository together with the Cotton library. One of the first elected trustees, working in close conjunction with Birch and stimulated by his brother Charles (also an avid collector and antiquarian), Yorke corresponded actively through the remainder of his life with agents overseas, librarians and fellows of university colleges, secretaries and executors of peers, and often those peers themselves to determine the location and contents of manuscript holdings and libraries. His role in relation to the Museum as it worked to collect and catalog manuscripts blended seamlessly with the pursuits of the amateur historian: in a 1759 letter, Thomas Gray describes a summer period of study in a British Museum reading room almost abandoned by the learned except for Dr. Stukeley, two Prussians, “& a Man, who writes for Ld Royston,” presumably as a copyist of manuscripts.33 In 1757, Yorke published an edition of the correspondence of Sir Dudley Carleton, a leading diplomat of the early Stuart monarchs, and in 1778 he produced an edition of Miscellaneous State Papers from 1501 to 1726 (which Elizabeth Montagu, incidentally, struggled valiantly to read through).

While members of the Yorke family, and even Talbot, teased the three men about their devotion to “old papers,”34 there is no doubt that it fostered an attitude of valuing the material traces of Britain’s past that contributed to the collection, preservation, cataloging, and use of such materials. Historians of the Museum have highlighted the reality of limited access to the library’s precious deposits in the early decades, despite their ostensibly belonging to “the people,” and there are certainly records in the Hardwicke correspondence of applications to Yorke, as a trustee, for permission to look at various collections.35 Nevertheless, it is clear from such exchanges that individuals with a scholarly claim were admitted and these attitudes, which were of their time, were accompanied by diligent efforts to gather and preserve what was at risk of being lost through sales of country house papers and mere neglect or ignorance. Chapter 5 will return to Yorke’s efforts, as the elderly Lord Hardwicke, to preserve and manage access to the world of the coterie from more personal motives, but in these early decades the energetic efforts of members of the Yorke–Grey coterie were devoted to preserving the British historical record as a national good.

Philip Yorke and Thomas Birch: friendship as intermediation

As already noted, the young Philip Yorke and Thomas Birch, if acquainted before the latter became what Lawry calls “overseer of the Press” for the Athenian Letters, were not initially friends in a sociable sense. Fifteen years Yorke’s senior and a product of Clerkenwell in the City, Birch seems to have been brought into the project simply as a client of the senior Lord Hardwicke who could serve as on-the-spot agent to ensure that the second volume of the Letters was more correctly printed than the first had been. But he entered with great enthusiasm into the spirit of the Letters, and writing from London to Yorke on October 6, 1741, Lawry describes a growing bond that is breaking down the social and geographical barriers (represented vividly by the butchers’ stalls of Hockley Hole) that stand between a university man and this City-bred scholar: “I find too much pleasure & improvement from his conversation to lose any opportunity of conferring with him; Neither did Hockley in the Hole discourage me from investigating his house, when I knew no better way of passing from mine to his and I daresay he will do me the justice to witness that I have not been an unfrequent Visitor.”36 In the course of several months in the autumn of 1741, the relationship between Birch and Yorke blossoms quickly: the former responds gratefully to the latter’s appreciation of his editorial labors and “with the utmost Diffidence” submits a Socratic dialogue of his own out of an “ambition to show myself among you in an higher character than that of a mere Editor”; is told by Yorke that his correspondence offers “a relaxing of the mind in the most ingenuous way, communicating the fruits of one’s studies, & speculations & repairing the loss of a Friends good Company in the most effectual manner”; makes his first visit to Yorke and the Marchioness and describes those days as the “most agreeable of my whole Life”; and expresses his gratitude for “a Friendship, which I feel the influence of in the kind Opinion entertain’d of me by others, whose Esteem is the highest Sanction to any Character, & which I shall always consider as the Ornament as well as the Happiness of my Life.”37

While there is no doubt that the “friendship” offered by Yorke and so gratefully accepted by Birch is of the eighteenth-century kind, bringing with it expectations of social and material advantage to Birch in exchange for services rendered, this does not preclude there being an affective dimension to this relationship, one that is based on mutual intellectual interests and the attractiveness for the constitutionally reserved Yorke of Birch’s loquacious and energetic character. In addition to his own editing of historical documents, Yorke’s unflagging encouragement of Birch’s parallel labors is encapsulated in a 1748 letter to Birch which he signs “Yrs affectionately”:

I earnestly recommend it to You not to give over the Investigation of original Papers as You seem to have done of late; that laudable Ardor for old Sacks, bad Hands, & dusty Bundles wants to be rekindled; Let me raise ye dying flame before It quite expires, Non solum in tanta pericula mittam; Is application necessary I will second it; Is Money wanting I will advance it, Is the Labor of the Eyes demanded, I will at least share with You ye glorious Toil. I think this not ill worked up, & if It does not set You to work, I shall say, good Writing is lost upon You.

Yorke’s note appended to one of the final letters from his friend is poignant: “N.B. July the 6th 1766/ When I left Wrest last Year I little Thought my Correspondence with my valuable Friend Dr. Birch of 20 Years standing almost uninterrupted should have had so fatal a Period as was put to it in January 1766 by a fall from his Horse – quem semper acertum semper honoratum &c. H.”38

Of particular value to an investigation of the interaction between scribal and print media cultures in the period is the way in which this friendship “translates” the print trade. Birch, as indicated by Lawry’s description of the route required for a visit to him, was somewhat of a foreigner, inhabiting an unfamiliar socioeconomic space for the more socially elevated members of the circle. Typical is Edwards’ astonishment in 1747 that Birch has just completed a lengthy rural sojourn: “Nothing I suppose but the Company at Wrest could have detained him so long in the Country; Three weeks – and with out even Mr Williams’s Coffeehouse too, must be as bad to him as three yards of uneven ground to Sir John Falstaff”; on another occasion, Yorke tries to entice him to visit with the promise that “if you insist upon it, the old smoaking Room shall be fitted up as a Coffee house & ye Neighbours summoned in.”39 Yorke’s attitudes toward the business of print, in turn, are initially derivative and uninformed; taking his cue from Pope’s Dunciad, he assumes that the booksellers are rapacious enslavers of a scholar like Birch: “Booksellers are Booksellers; that is to say, People, who care not what Trouble others have, provided the profit is theirs.” When Yorke implies that only a lack of proper initiative on Birch’s part prevents him from negotiating better remuneration from Andrew Millar, Birch displays a rare flash of resentment:

You may judge of the Bargain, which I have made with Millar, & what better Terms I could expect from other Booksellers, from this short Estimate of the Expence, that the printing of the Sheets will amount to 98£, the paper to 81£, the binding of 500 Copies of the Volumes, in quarto, at 4s. a Book 100£ & advertisements & other incidental Charges to 10£, that is, 289£ in the whole. The Sale of which, computed at 18.s a Book, the highest price to the Booksellers, tho’ sold to Gentlemen at a Guinea, will raise 450£, from which 289£, the Expence, being deducted, the Profit to be divided between the Author & Bookseller will be 161£, out of which the latter cannot be expected to allow 100 Guineas for the Copy, & at the same time run the risque of the whole.40

This account of mid-century print economics is only one of a number of occasions where Birch articulates the interdependence between a man of letters, immersed in historical scholarship, and the everyday work of the trade.

While Chapter 5 of this study will reveal that Yorke in his later years felt considerable suspicion of the commercial press and its readers, he used the print medium (by means of intermediaries) throughout his life, not only to make his own historical work available for restricted distribution, as already discussed, but also to write anonymous letters to newspapers or magazines on political issues, and even to print privately a series of authentic-appearing mock newspapers on the events of the Elizabethan battle against the Spanish Armada, which for a time convinced scholars of their authenticity as the first English newspapers.41 It is noteworthy that as the youthful contributors to the Athenian Letters became more settled in provincial locations, the eyes of this coterie increasingly turned to London, not only as the place where the admirable literary creations of contemporary authors such as Isaac Hawkins Browne and Hester Mulso, or the scandalous ones of Jonathan Swift and John Wilkes, were to be heard read aloud or seen in manuscript, but also as the primary source of news about print events like the publication of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary.42 Increasingly when at Wrest Yorke laments his lack of news from the country to compensate for that which issues from the city. In exchange, as Dustin Griffin has noted in a recent treatment of Birch’s career as “author by profession,” Birch had, by the end of his career, “established remarkable ties with the cultural and political establishment of 1760s England,” a situation certainly in part due to the Hardwicke connection and one that compares more than favorably with that of Samuel Johnson, just four years his junior, at the same period. David Philip Miller has noted more generally that “through their influence in the Royal and Antiquarian Societies and as Trustees of the British Museum, through their powers of Church and legal patronage there was scarcely an office or position in the learned world over which the Hardwickes and their circle did not exercise influence” in the 1750s and early 1760s.43

Ultimately, however, the political shifts already noted and a lack of his father’s ambitious self-assertion, compensated for by an over-riding concern for the family reputation – “our situation & circumstances in general,” as Charles put it when ordering the burning of the printed copies of Athenian Letters – seem to have prevented Philip Yorke from engaging as fully in the new media interface as he might have done if only his personal tastes had been considered. As a result, the influence he initially promised in the eyes of those early observers (and to which Horace Walpole alerted Horace Mann in 1757)44 was arguably never realized. When in later life he admits that in refusing a long-ago dedication request made by Conyers Middleton he acquiesced to the wishes of his father on a point with which he was not in agreement, we sense an acknowledgment that he might have liked to play a more active role in the literary life of his day.45 Birch at one point regrets that the occasional and political nature of much of the Yorke–Grey coterie’s writings made it impossible to publish them: “It is an Instance of prodigious Self-denial, that Authors, who are capable of writing with such Vivacity & Elegance, should fall upon such Subjects, as oblige them to suppress their performances, & deny themselves that Reputation, which might be rais’d in a Miscellany or a Magazine.”46 Facetiousness aside, Yorke’s place in the literary world ultimately remained at one remove from the action, and for all his encouragement of the activities of others, the promise of the Yorke–Grey coterie as a group had dissipated by the 1760s.

Viewed from the perspective of its greatest activity in the 1740s and early 1750s, however, there is no denying the prestige and the energy this coterie infused into the literary scene. One conduit of this energy, as already noted, was the Philip Yorke–Thomas Birch axis, a conjunction greater than the sum of its parts. Another of the circle’s most surprising legacies, the one I will turn to next, is the model it provided for the coterie formed by the printer-novelist Samuel Richardson in the early 1750s.

The Richardson coterie, 1749–55

The above discussion of the Yorke–Grey coterie has demonstrated the close relationship at mid-century between manuscript-exchanging circles and the London print trade, especially regarding poetry production and circulation, the developing discourse of literary criticism, and the valuing of old manuscripts as historical documents. The mid-century novel, however, might appear to want nothing more than to flaunt its printed materiality, ostentatiously staging the discarding and destruction of the manuscript as its ephemeral and precarious precursor: Sarah Fielding’s 1760 History of Ophelia, which she claims, as “the Author of David Simple,” to have found carelessly abandoned in “an old Buroe” purchased at second hand, and Henry Mackenzie’s 1771 Man of Feeling, where the ineffectiveness of the hapless hero is reflected in the fact that his story is recorded in a manuscript gradually being destroyed as gun wadding, come to mind.47 But in some of the most socially ambitious novels of the period – Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa in particular – acts of manuscript production are placed at the center of the reader’s attention, as when Clarissa’s legacy is gathered together by Lovelace’s friend Jack Belford to form the book we read. Janine Barchas has discussed this novel’s foregrounding of the “materiality of book-making” through devices such as the insertion of a musical score on an engraved folding plate. But in this instance Clarissa also claims for its print manifestation a genteel source in the privileged world of coterie exchange, reinforcing the musical score’s associations with “an educated, almost aristocratic, milieu”;48 the unprinted Elizabeth Carter poem that provides the lyrics for Clarissa’s composition is described by the heroine herself as “that charming ODE TO WISDOM, which does honour to our sex, as it was written by one of it.” Thus, not only does the fictional Clarissa Harlowe, in Barchas’s words, “engage the discourse of music” in a manner that aligns her with “Bluestocking philosophy,” but her author’s costly “reproduction” of the score highlights (or in Richardson’s words, “do[es] intentional honour to”) an actual group of women and their practices of manuscript exchange.49

Discussion of Samuel Richardson’s own central involvement in the manuscript-based practices of a coterie involves three adjustments of perspective. First, although Richardson was undoubtedly an innovator of the book, using his dual position as printer-author to experiment with the incorporation of typographical markings, character lists, tables of contents, and indices into his fiction,50 I will focus here on how the form and texture of his novels is of a piece with his desire to replicate coterie life in his own practice. Indeed, the novelist’s belief that he had developed “a new Species of Writing” stemmed in large part from his ability to draw on the effects of immediacy, intimacy, and affect created by manuscript exchange within a select circle of correspondents.51 Second, despite critics’ generalized references to his “circle” of correspondents and visitors, it is actually more precise to say that Richardson participated in multiple circles (albeit overlapping) with various orientations to the culture of letters. One of these circles was primarily focused on print literary production and included authors such as Samuel Johnson, Charlotte Lennox, Sarah Fielding, Jane Collier, and later Frances and Thomas Sheridan. Another was largely professional, though it extended to the family members of colleagues; this included Edward Cave, the Millars, Parliamentary Speaker Arthur Onslow, Edward Young, Philip Skelton, and Benjamin Kennicott. A third contingent centered around response to the novels and discussion of how the social issues they raised could be applied to contemporary conduct – here the range of individuals is broad, ranging from the highly engaged and influential Lady Bradshaigh to Mary Delany, Anne Donnellan, Aaron Hill and his daughters, Sophia Wescomb, Sarah Chapone, Frances Grainger, Mary Watts and Colley Cibber. This chapter, however, draws a distinction between the generality of these readers and those whose cultivation enabled the printer-novelist’s participation in the privileged world of the literary coterie.

And finally, although in one respect Richardson in his late career can be seen as taking an increasingly “modern,” print-oriented approach to his audience, sending typeset pamphlets to anonymous readers who objected to his handling of elements of the plot of Sir Charles Grandison, this model of unidirectional communication parallels a move toward the development of an active literary coterie of his own. Richardson’s cultivation of relationships with his readers, on the other hand, has tended to be seen as feminized and anachronistic when held against the active masculinization and professionalization of authorship in the middle decades of the century by writers such as Alexander Pope and Samuel Johnson.52 Such a dichotomy, as I indicated in this book’s introduction, does not reflect the reality of a mid-century literary culture that felt the very real gravitational pull of the intimate coterie as a model for the nurture of imaginative writing. Re-examining Richardson’s participation in literary circles with an alertness to the coexisting media cultures of the 1740s and 1750s can enrich and nuance our understanding of his choices as about something more complex than a simple gender dichotomy or a stance for or against the inevitable historical trajectory of authorship.

Granting the prestigious status of contemporary manuscript-exchanging circles such as the one centered at Wrest Park, even a London printer with multiple connections among leading members of the book trade and a growing authorial stature might well have measured cultural capital in terms of membership in one or more of them. Indeed, Richardson had a connection of some sort with numerous members of the Yorke–Grey coterie and undoubtedly understood its collective significance. In December 1748, Philip Yorke writes a note of thanks to the author for a gift copy of Clarissa, and in September 1750, Thomas Birch reports to Yorke that Richardson is at work on “the Subject, which you heard him mention at your own house, of the virtuous & generous Gentleman [i.e. the future Sir Charles Grandison].”53 But the relationship can only have been peripheral; some combination of extensive learning, sharp verbal wit, and high status could have made him at ease in such a group, but Richardson possessed none of these. More likely, his contacts with the coterie were mediated through Birch, Wray, Edwards, and Talbot. Birch, that alert denizen of the London print world, continues in the above-quoted letter to mention that Richardson “has desir’d me to give him an Hour or two’s Attention in the reading of his plan.” Richardson’s correspondence with Edwards makes several references to encounters with Wray. Edwards, already a member of the Yorke circle, seems to have discovered Clarissa through his good friend the Parliamentary Speaker Arthur Onslow, also a friend of the author; in late 1748, he thanks Richardson for his gift of the last three volumes of the novel, saying he has been envying “our good Friend the Speaker the privilege of seeing it sheet by sheet as it came from the press.” Meanwhile, Edwards has begun discussing Clarissa with members of the Yorke circle, describing Richardson’s emotional power to Wray as “next to Shakespear” and as having “more of that Magical Power which Horace speaks of than I ever met with,” and pleased with Yorke’s high opinion of the conclusion because “I look upon this work as a Criterion of sensibility.”54 But over time, Richardson’s fullest access to this circle would be through his friendship and collaboration with Catherine Talbot during the period of his composition of Sir Charles Grandison. Richardson consulted extensively with her regarding the creation and representation of his high-life characters for the novel, while a note of early 1750 from her to Richardson passes on messages of thanks from “the Family so obligingly entrusted with [additional portions of Clarissa]” as well as from Jemima Grey’s young step-aunt Lady Sophia Egerton.55

If Richardson would not have dreamed of membership in the Yorke–Grey coterie, its visibility to him, as to others “in the know” in England’s cultural center, established an ideal of literary achievement in the context of sociable exchange to which he seems to have aspired. Thus, he actively facilitated the construction of such a coterie, which coalesced in the late 1740s as he was preparing the expanded and elegant third edition of Clarissa and remained active to at least 1755, through the period of the composition and publication of Sir Charles Grandison – in other words, during the heyday of his print-based authorial success. The formation of the group was enabled, first, by Richardson’s introduction to Edwards. As an enthusiastic admirer, Edwards presented Richardson in 1749 with a sonnet in praise of Clarissa; Richardson reciprocated with a print of himself.56 According to John Dussinger, editor of the Richardson–Edwards correspondence, at about this time Richardson also introduced Edwards to Susanna Highmore, leading to an exchange of sonnets between Edwards and the twenty-five-year-old Highmore, daughter of the painter Joseph.57

A recognizable coterie can be said to have formed over the next year, as Edwards sent his earlier sonnet attacking Warburton along with a printed copy of his 1750 edition of The Canons of Criticism and as Richardson introduced the fifty-year-old Edwards to the twenty-year-old Hester Mulso (later Chapone), daughter of “a gentleman farmer,” and therefore, like Highmore, born “into the upper reaches of the middle-class.”58 For Mulso, already the author of poems such as “Ode to Peace written during the Rebellion in 1745,” her introduction into this group, possibly through the mediation of Highmore or of Mary Prescott, her elder brother Thomas’s fiancée, marked the start of her “public” life. Others who were drawn regularly into these literary exchanges included Isabella Sutton, a Miss Farrar, Sally and John Chapone (children of Sarah Kirkham Chapone, whom Richardson accurately described as “a great Championess for her sex”), Elizabeth Carter, John Duncombe (son of William, who in turn was a link between the Highmores, Carter and her father, and Richardson), and Mulso’s brothers John and Edward. Catherine Talbot was simultaneously expanding her relationships with members of this coterie, writing to Carter in late 1750, “Pray who and what is Miss Mulso? She writes very well, and corresponds with you and Mr. Richardson. I honour her, and want to know more about her.”59 Ongoing references to Mulso in the Carter–Talbot correspondence indicate regular contact during the early 1750s, and Talbot in turn appears as a subject of discussion between Richardson and both Edwards and Carter.

This brief description has illustrated a fundamental characteristic of the eighteenth-century coterie: its basis in multiplex social ties of kinship, friendship, and even courtship. Susannah Highmore’s sketch of some of the most frequently gathered members of this group listening to Richardson read from his manuscript of Sir Charles Grandison captures the self-conscious of its existence as a collective entity (Figure 1.3). The sketch also locates the coterie geographically – the scene is set in the grotto of the author’s rented suburban home of North End, to which he retreated regularly from his business premises and City home of Salisbury Court and which was the center of his family and social life from 1738 until the summer of 1754, when his family relocated to Parson’s Green. Young friends of Richardson stayed there for long periods of time, as they might have done at a country house, and his correspondence constantly shows him urging far-flung contacts to avail themselves of the place as a base for London visits. Edwards accepted the invitation on several occasions. The symbolic importance of North End for the coterie is perhaps best illustrated by the efforts of Richardson and Mulso to convince Carter to visit, culminating in what she seems to have seen as almost a plot whereby Talbot promises on Carter’s behalf, in May of 1753, that she will make an overnight visit, “put[ing her] in action,” Carter complains, as “the puppet who moves by wires and strings.”60

Figure 1.3 Susanna Highmore, “Richardson reading the MS History of Sir Cha. Grandison at North End,” c. 1753. Pictured from left to right are Richardson, Thomas Mulso, Edward Mulso, Hester Mulso, Susanna Highmore, Sarah Prescott, and John Duncombe.

Of all the clusters of guests who passed through North End, the Edwards–Highmore–Mulso group is also the only one that also fits the coterie criterion in its practice of social authorship, that is, the exchange of poetry and other literary texts, to solidify relations between members of the group while providing mutual entertainment and improvement. The core group I have identified was built upon regular circulation of poetry, especially in the sonnet and ode forms, encouragement of one another’s literary achievements, writing on set themes, and discussion of other writers’ work. Its interactions were carried out both in person, primarily at North End, and through correspondence. Thus, Paul Trolander and Zeynep Tenger’s characterization of sociable literary criticism in the late seventeenth century applies to the literary activity of this group as well: it was “sanctioned” by personal relationships, operated “by a set of rules that govern[ed] the social activity of the poetic … text,” and functioned as much to “create and build social bonds among individuals who bolstered one another’s social and political standing” as to produce finished literary products for wide consumption.61 While by virtue of its social position the political and economic aims of this mid-eighteenth-century group were more indirect than those of the Katherine Philips’ circle upon which Trolander and Tenger’s argument is based, or than those of the patronage-wielding Yorke–Grey coterie, it certainly functioned to encourage, improve, circulate, and heighten the reputation of the group’s writings.

The construction of the coterie can be seen in action early in the Richardson–Highmore–Edwards–Mulso relationship in a letter of Richardson to Edwards dated March 19, 1751, wherein Richardson encloses Hester Mulso’s “Ode, Occasion’ed by Reading Sonnets in the Style & Manner of Spenser, written by Tho. Edwards Esq.” He writes, “You will, I know, excuse me for transcribing one Verse in the following Piece. You will be pleased with it, when you are told it is a Lady’s, on reading your Sonnets already in Print, and seeing that [the sonnet] you have honoured me with. It is Miss Mulso’s.” Richardson uses his pre-existing relationships with both Edwards and Mulso to forge a connection between them in the form of one writer’s praise of the other, flattering Edwards with this expression of admiration by a lady. At the same time, he lays claim to his own position in the group by explaining that what kindled Mulso’s poetic inspiration was the inspiration he had himself incited in Edwards when the latter composed his homage to the author of Clarissa. And the “Verse,” or line, of Mulso’s poem which Edwards must excuse him for transcribing is that wherein the speaker praises Edwards most “When Richardson’s loved Name adorns thy Song,” underscoring once again the novelist’s originary role in the poetic productions of his friends.62

Edwards replies two weeks later with appreciation and a sonnet in response: “Your Linnet twitters most enchantingly, I am exceedingly obliged to her for her music, and have endeavored to chirp to her again as well as I can in the inclosed Sonnet which I beg You to present to her from me if You think it worth her acceptance.” Richardson is invited to play the role of intermediary and judge who will determine if Edwards’ sonnet is worthy of circulation. Edwards continues, “There is, and I doubt not but that You have felt it, there is something more deliciously charming in the approbation of the Ladies than in that of a whole University of He-Critics; and if I can deserve their applause let the sour Pedants rail as much as they please.” While Edwards is most obviously drawing a gendered contrast here, the context of his print-based quarrels with the “sour Pedant” Warburton reminds us that this is as much about repudiating the sorts of controversy fostered by an improperly regulated print regime of literary criticism. By comparison, this coterie setting offers a more exacting, while less noisy, critical standard: he goes on to quote the poet Joseph Thurston, “‘For theirs, the clame to each instructive tongue/And theirs the great Monopoly of Song.’”63

Edwards’ enclosed reply to Mulso addresses her in the persona she established in the originating poem, thereby establishing a sense of insider exchange:

In subsequent letters between Edwards and Richardson, considerable space is devoted to gestures reinforcing the bonds of the circle: greetings are accompanied by affirmations of mutual affection between “the sweet Linnet,” “Miss Highmore,” and “dear Mr. Edwards” and by promises to show “charming” letters from the one to the other. Suffering through a long winter in the country, Edwards revives the life of the coterie in February of 1753 with a challenge that once again pits it against professional authorship: “Has Miss Mulso written any more Odes? Or Miss Highmore any more Sonnets? Or are they contented to shew that they can excell if they would, and to leave the idle work to Scriblers by Profession? What news have you from Deal [Carter’s home]?” Richardson replies by enclosing Mulso’s “Ode to [Robin],” written on a recent trip to Canterbury and annotated by “a certain admirable Lady,” Catherine Talbot.64

Richardson also plays the coterie correspondent’s role of suggesting topics for Edwards’ muse, proposing that he write a poem on Susanna Highmore’s scorching herself with her curling iron, as a specific warning to her for having “often set the Hearts of young Fellows on Fire,” and as a general “Warning to her Sex” against “playing with Fire.” While Edwards initially declines this opportunity, as “a subject too serious for verse,” the spirit of occasional composition embedded in social relations is captured in his refusal nonetheless: “But a Poet would not suppose the conflagration to have proceeded from the heat of the Irons, but from the Love-verses which she used on that occasion; and which, as Mrs. Mincing says, make the curls so pure and so crisp, that they are often put to that use; and the blaze happening on the left side, he would imagine to be extinguished by the prevalent force of the cold about her heart. But if she has spoiled her hair, it is no jesting matter.” This same letter encloses another sonnet to Mulso, one that “my gratitude has forced from me” at the honor she has done him in her earlier offering. The sonnet invites Mulso, just as Edwards’ more rustic muse has praised Clarissa, to produce the higher strains that will encourage Richardson to proceed with the creation of his hero Grandison. Edwards and Richardson agreed in encouraging a woman’s correspondence and writing within “the Circle of her Acquaintance,” whose “Love or Admiration, perhaps Envy, will induce them to spread her Fame” beyond their immediate circle.65 In keeping with this view, the novelist encouraged Mulso’s important letters on filial piety, written early in their relationship (1750–51), as well as challenging her, it seems, to produce her subsequent “Matrimonial Creed” in 1751 as a defense of her view of marriage.

At the same time, Richardson demonstrates his knowledge of the rules of coterie exchange when he reports that Highmore has written an “Ode to Content,” of which “She can only authorize a Copy to be given”; in this manner, the boundaries of the coterie could serve to protect its members from unwanted public exposure. John Duncombe, Highmore’s suitor and author in 1754 of The Feminiad, a poem celebrating the unpublished poetry of Highmore, Mulso, and Farrar, along with the print achievements of Carter, Catharine Cockburn, Elizabeth Rowe, and Mary Leapor, shows his own initiation in coterie practice when he sends Richardson an elusive poem the latter has been hoping to gain permission to see – Miss Farrar’s “Ode to Cynthia” – accompanied with the words “Inclosed is the desired Ode. You know the Conditions; tho’ to you and Mr. Edwards ‘tis needless to prescribe any.” Richardson forwards the poem with the explanation: “These were, not to give out Copies, or allow Copies to be taken.” On occasion, loyalty to the group supersedes even the demands of print controversies, as when Edwards chooses to remove a dig at Warburton from the preface to his 1753 Trial of the Letter Y in deference to Miss Sutton (whose baronet father had been the first patron of Warburton), as “a Lady who does me too much honor for me to venture her displeasure.”66 A posthumous expression of the cohesion at the heart of this coterie is inscribed on the cover of Richardson’s carefully preserved collection of his correspondence with Edwards, in the form of a proviso that it may be seen only by certain of Edwards’ family members and friends, to be returned to his own family, “with whom it must ever be private; – No Extracts to be taken from it or Letters Copied.” On that short list is Hester Mulso – surely a significant choice of this young female friend for a correspondence considered too revealing to be shared by more than six people.67

Elizabeth Carter’s role in this coterie demands special mention. Her initial contact with Richardson came through the mediation of Highmore after Talbot had informed her of the novelist’s unauthorized use of her “Ode to Wisdom.” Carter cultivated literary friendships with Mulso and Highmore individually, just as she had with Talbot earlier, rather than proceeding through Richardson as we have seen others do. Although she is frequently referenced in correspondence between other members of the group, Richardson’s epistolary exchange with Carter does not begin until June 1753, after the reluctant visit to North End mentioned above. While the letters do not involve poetic or prose enclosures, Richardson throws out the gambits typical of coterie correspondence. In one of the more successful of these exchanges, the two writers share their childhood dreams of magic rings or caps that would render them invisible. On the other hand, when Richardson plays the game of shared secrecy by making coded references to their mutual friend Talbot – saying “I must not name her,” calling her “your Sister Mind,” “a certain Lady,” “your Sister Excellence,” or even “––,”and claiming that “The Lady I must not name, is the Queen of all the Ladies I venerate,” Carter responds rather testily, “if you will not write her name, why should I? I do not know that I should write it more prettily than you.” This resistance to coterie conventions is in keeping with Carter’s apparent wariness of being drawn too tightly into Richardson’s orbit, discussed below. Nevertheless, maintaining the seriousness with which he has taken the coterie injunction of protecting reputations, when Richardson subsequently prepared this correspondence for potential publication, he played with various disguises for the names – thus “Carlington,” “Carlingford,” and “Carteret” for Carter, with Talbot finally named as “Miss Tankerville.”68

This account of the Richardson–Highmore–Edwards–Mulso coterie reveals a group of individuals who were relatively equal in their status as genteel, but of the lower gentry or upper middle-class, well-educated, and tied together by multiple relations of “friendship,” by literary projects such as Clarissa, Samuel Johnson’s The Rambler, and Sir Charles Grandison, and by shared moral and intellectual interests in questions emanating from these works, such as matters of female autonomy and social responsibility. Catherine Talbot’s very real, yet somewhat peripheral, position in the group can be related to the fact that she was at once superior in status and connections, yet very supportive of the coterie’s literary and social aims, and geographically proximate through her residence at the Deanery of St. Paul’s during this period (see Chapter 2).69 The importance of social nuance is also suggested by this group’s remaining distinct from the more professional authors’ circle gathered around Richardson at this time which, as already noted, included Sarah Fielding, the Collier sisters, Samuel Johnson, and Charlotte Lennox. Beyond shared status and interests, the coterie was characterized by the powerful centrality of Richardson, whom Hester’s brother John describes as “infinitely dear to those who know Him, and studiously sought after by those who do not. Rare Avis in Terris.”70 As we have seen, bringing the group’s members together, either physically at his country house of North End or through epistolary exchange, he worked tirelessly to facilitate the bonds of literary sociability between them.

The decline of a coterie

Nevertheless, this active, productive, and by some measures well-balanced coterie eventually dissolved, seemingly when mutual criticism became too fundamental. In the summer of 1754, coinciding with the Richardsons’ move from North End to Parson’s Green, Susanna Highmore wrote a sonnet chiding Edwards for limiting himself to that form; Richardson insisted on showing it to its addressee, provoking from Edwards a lengthy defense of his propensity. Just a few weeks later, John Duncombe in turn sent Richardson a similar sonnet, rather peremptorily writing that “If you approve the design of the following sonnet you may, if you please, communicate it to your friend. Whether the author approves it or not, it speaks my real thoughts (in which I am far from being singular).” Richardson responds tactfully that “Your sonnet, dear Sir, well as I like it, will not be communicated to Mr. Edwards by me, for reasons I will read to you the next time I have the pleasure of seeing you.” One can conclude that Richardson saw the junior members of the coterie becoming a little too rebellious and intervened not only by blocking the channels of exchange but also by taking the communications of the coterie “offline,” so to speak – that is, out of the medium of script altogether. Although Edwards originally thanked Highmore for her poem, “which does me so much honor that I cannot find in my heart [to] repent my doing that which occasioned it,” it seems the damage had been done. The following January, Edwards writes to Richardson, “I must own I have written no Sonnets since I saw You, nor indeed have I had any impulse that way; Whether the vein is exhausted, or whether it is checked by that frost which You know happened last summer, I cannot tell; but I believe I have done with Poetry.” By 1755, his conveyed greetings are most often to Richardson’s family and to the more passive Sophia Wescomb, rather than to Mulso or Highmore, and Richardson writes to Mary Delany’s sister Anne Dewes, “I believe Miss M., Miss P., and that more than agreeable set of friends, and we, love one another as well as ever … but we meet not near so often as we used to do.”71

Richardson goes on in this letter to speculate that “the pen and ink seems to have furnished the cement of our more intimate friendship; and that being over with me, as to writing any more for the public, the occasion of the endearment ceases.” With this theory he acknowledges the centrality of his stature as novelist to the group’s structure, but he also more inadvertently suggests the broader significance of “pen and ink” – that is, of both epistolary and poetic production – to the vitality of the coterie. In addition to the subversive use of pen and ink to challenge Edwards as writer, outlined above, there are indications of how Hester Mulso’s place in the group might ultimately have become an uneasy one. A brief quotation from her preamble to the “Matrimonial Creed” mentioned above suggests some of the tensions at work. Mulso begins with the statement: “Being told one evening that I could not be quite a good girl, whilst I retained some particular notions concerning the behaviour of husbands and wives; being told that I was intoxicated with false sentiments of dignity; that I was proud, rebellious, a little spitfire, &c. I thought it behoved me to examine my own mind on these particulars.”72 Although Richardson may not have been the only conversational accuser here, the passage hints at the constraint an asymmetry of age and gender could place on the ability of the group members to grow intellectually and express disagreement, and by extension, on the sustainability of the group. Similarly, the stance Mulso seems to feel is required in her earlier debate with Richardson on filial obedience in relation to the choice of a marriage partner suggests the inevitable limitations of her position. Thomas Keymer’s detailed discussion of this exchange as “bring[ing] to bear citations from an array of moralists, jurists and political theorists, from Hall and Allestree on Richardson’s side, by way of Grotius and Pufendorf, to Algernon Sidney and Locke on her own” makes clear the challenging intellectual plane at which Mulso was operating.73 While demonstrating in the letters her learning, capacity for close reasoning, and critical faculty, she begins the series with the formulation that she is “expos[ing]” her “opinions” to Richardson, “in order to have them rectified” by him; insists throughout that while she is working towards the end of “bring[ing] [her] reason to give its free assent to [his] opinion,” she is nevertheless impeded by a tendency to be “very slow in apprehending truths”; and concludes with the assertion, “I wish to think with you on all subjects.”74 Despite the fact that Carter, Duncombe, and Mulso’s brother John privately assured Mulso of having got the better in the exchange,75 it is clear that significant rhetorical skill is being invested in maintaining the fine balance between debate on equal intellectual terms and the requirements of respectful submission to a male elder who has revealed, in Keymer’s apt phrase, his “instinctive authoritarianism and his fear of insurrection.”76

It must be underscored that differences of age and gender were not impediments to the formation and successful functioning of the coterie for a time. Susan Staves has noted the importance of clergy connections to intellectually ambitious Bluestocking women;77 Mulso herself, as a very young woman, clearly found the literary mentorship and encouragement of older men valuable. Thus, her brother’s correspondence reports Hester’s “conquests,” in January 1750, of the Dean of Peterborough and “old Dr. Robinson,” with the latter of whom “there passes … such a pretty war of wit, as deserves printing as much as Jo: Miller, & Durfey’s Pills to purge Melancholy.” If Richardson was originally “infinitely dear” to his young admirers, who viewed “all that Mr R – says” as “oracular,” his praise of Mulso’s poems as those of “a charming child” (according to John Mulso’s report of his reponse to her 1751 “Ode, written during a violent Storm at Midnight”) may have worn thin as Mulso approached her mid-twenties.78 Richardson, in turn, accustomed to his position as mentor and conduit at the center of the coterie, may well have felt the pang suspected by Johnson, who later wrote with reference to his own relationship with Hester Thrale: “You make verses, and they are read in publick, and I know nothing about them. This very crime, I think, broke the link of amity between Richardson and Miss Mulso, after a tenderness and confidence of many years.”79 This is not to imply that Richardson’s respect for his “dear Miss Mulso” was not sincere – after all, it was she, Highmore, Carter, and Lady Bradshaigh who were urged to submit letters in the voices of Grandison’s principal characters to initiate a continuation of the novel.80 But the relations upon which this network had been constructed inevitably changed to the point where it could no longer function as a literary coterie.

The importance of the Richardson coterie

Despite this coterie’s relatively short time of flourishing, its interpenetration with other literary circles and with the print publishing trade – in other words, its influence – is instructive. Not only did it stimulate, during its existence, the production of a body of poetry by Edwards, Mulso, and others, as well as Mulso’s epistolary writings on filial obedience, but these works circulated widely in both script and print. Edwards’ sonnets in praise of Richardson soon made their way into the paratexts of editions of the latter’s novels, and later in the decade into the sixth edition of the Canons; his treatise on orthography was also strongly encouraged by Richardson and the group. But Edwards entered the coterie as an already well-connected writer with an established reputation in manuscript-exchanging circles, as we have seen. More remarkable is the fame achieved by Hester Mulso through the connections opened up by the Richardson-centered coterie of which she became a part.

The efficiency of this coterie in circulating materials through the multiple links between its members is demonstrated when Carter offers in 1752 to send Talbot “a copy of Miss Mulso’s verses,” only to learn that Talbot has already been shown them by Richardson.81 But Mulso’s poems can also be seen moving as a valuable commodity along the channels of manuscript exchange beyond this network cluster in the early 1750s. In a particularly striking example, a letter from Thomas Birch to Mary Capell, daughter of the third Earl of Essex, and at this point, together with her sister Charlotte, a member of Lady Grey’s social circle, thanks her for “some of the most agreeable Days of my Life, which I ow’d lately to your Conversation,” and in exchange offers her copies of three manuscripts whose access is highly restricted: