Refine search

Actions for selected content:

24562 results in Architecture

Tuscany in the Age of Empire. Brian Brege. I Tatti Studies in Italian Renaissance History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021. xii + 492 pp. $59.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 295-296

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Women Readers and Writers in Medieval Iberia: Spinning the Text. Montserrat Piera. The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World 71. Leiden: Brill, 2019. xxiv + 484 pp.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 324-326

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Knowledge Building in Early Modern English Music. Katie Bank. Routledge Studies in Renaissance and Early Modern Worlds of Knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge, 2021. xiv + 282 pp. + 17 b/w pls. $52.99.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 275-277

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Descartes and the Ingenium: The Embodied Soul in Cartesianism. Ed. Raphaële Garrod and Alexander Marr. Brill's Studies in Intellectual History 323. Leiden: Brill, 2021. xiv + 240. €10.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 311-312

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

ARQ volume 28 issue 1 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- arq: Architectural Research Quarterly / Volume 28 / Issue 1 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 July 2025, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- March 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Scottish History in the Eyes of Sixteenth-Century France

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 97-129

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Transactional architecture: the interwar activities of architect-developer Jean-Florian Collin in Brussels

-

- Journal:

- arq: Architectural Research Quarterly / Volume 28 / Issue 1 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 July 2025, pp. 35-48

- Print publication:

- March 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

“A Sweet but Grave and Sad Melody”: Music and Emotion in Exequies in Post-Tridentine Italy

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 175-214

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Intellectual Education of the Italian Renaissance Artist. Angela Dressen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. x + 386 pp. $99.99.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 272-274

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Shaping bureaucracies for building

-

- Journal:

- arq: Architectural Research Quarterly / Volume 28 / Issue 1 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 July 2025, p. 3

- Print publication:

- March 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Learned Physicians and Everyday Medical Practice in the Renaissance. Michael Stolberg. Trans. Logan Kennedy and Leonhard Unglaub. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022. xxvi + 614 pp. $107.99. Open Access.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 274-275

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

“Di somma aspettazione e di bellissimo ingegno”: Pellegrino Tibaldi e le Marche. Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari, Valentina Balzarotti, and Vittoria Romani, eds. Fonti e studi per la storia dell'arte e del collezionismo. Ancona: Il lavoro editoriale, 2021. 200 pp. €40.

-

- Journal:

- Renaissance Quarterly / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2024, pp. 264-266

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

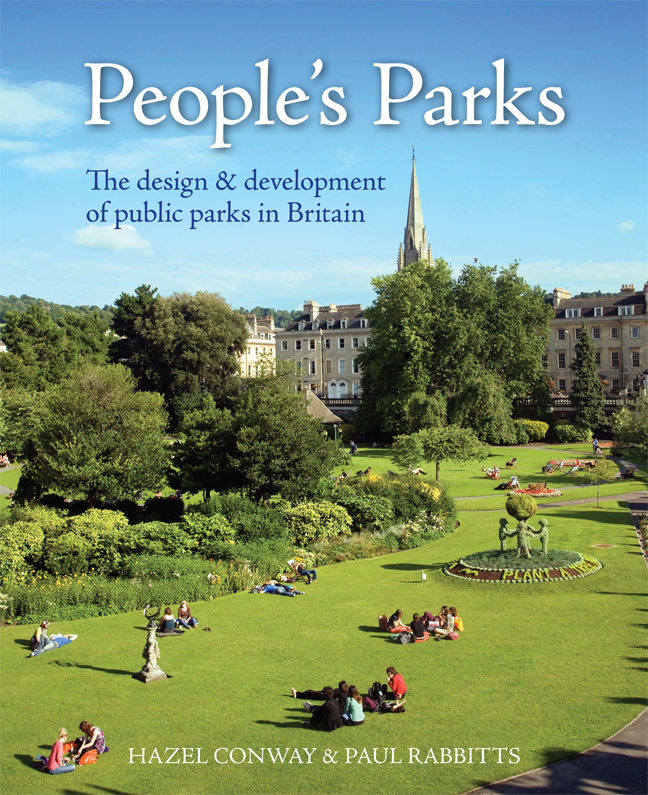

People's Parks

- The Design and Development of Public Parks in Britain

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 22 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 November 2023

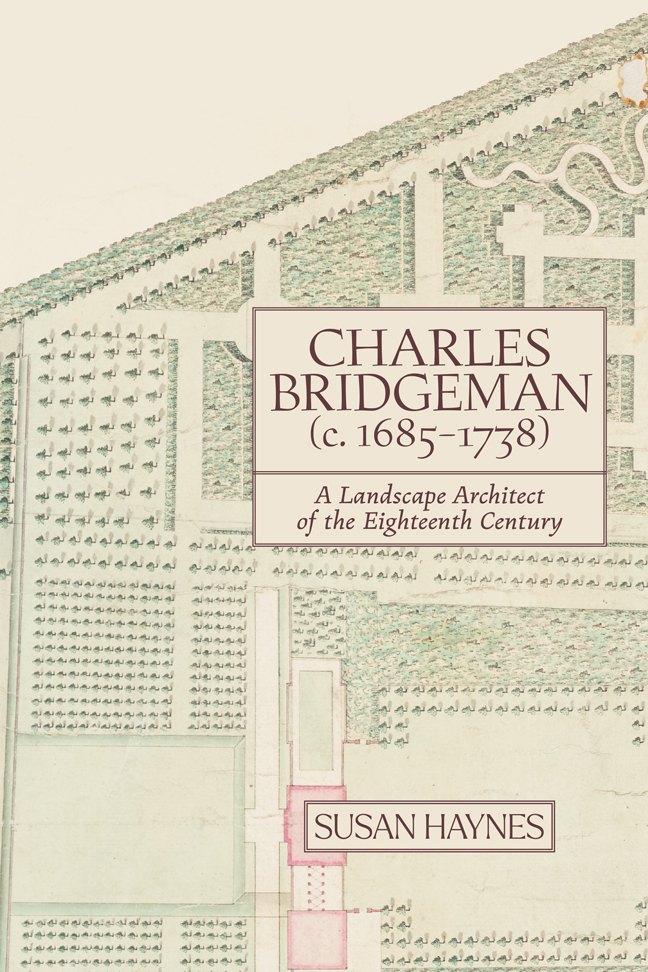

Charles Bridgeman (c. 1685-1738)

- A Landscape Architect of the Eighteenth Century

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2023

List of Figures

-

- Book:

- Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024, pp vi-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Transparent City: Mansions, Montage and Commodity Architecture in The Kill and The Ladies’ Paradise

-

- Book:

- Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024, pp 109-140

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Whiteness of the City

-

- Book:

- Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024, pp 203-227

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Unstable City: Rivers, Railways and Houses in Dombey and Son and Our Mutual Friend

-

- Book:

- Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024, pp 68-108

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Mobility, Concealment, Transparency

-

- Book:

- Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024, pp 1-36

-

- Chapter

- Export citation