Refine search

Actions for selected content:

37426 results in Art

10 - Housing Temporalities: State Narratives and Precarity in the Global South

-

-

- Book:

- Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Wellbeing in Diverse Global Settings

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 May 2025, pp 185-207

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: What Is Happening to Housing? Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Well-being in Diverse Global Settings

-

-

- Book:

- Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Wellbeing in Diverse Global Settings

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 May 2025, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Aboriginal Social Housing in Remote Australia: Crowded, Unrepaired and Raising the Risk of Infectious Diseases

-

-

- Book:

- Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Wellbeing in Diverse Global Settings

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 May 2025, pp 9-42

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Wellbeing in Diverse Global Settings

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 May 2025, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Reply to Gabriela Quintana Vigiola: Informal Housing Residents’ Well-being in Cities of the Global North and South

-

-

- Book:

- Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Wellbeing in Diverse Global Settings

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 May 2025, pp 71-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Intersections of Housing Precarity, Health and Wellbeing in Diverse Global Settings

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 May 2025, pp 244-252

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

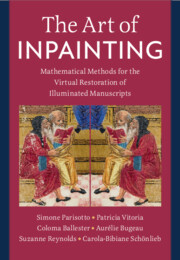

The Art of Inpainting

- Mathematical Methods for the Virtual Restoration of Illuminated Manuscripts

-

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025

2 - Local Inpainting Methods

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 13-51

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp v-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Deep Learning Inpainting Methods

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 115-161

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix Manuscripts in Focus

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 178-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Non-Local Inpainting Methods

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 52-114

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Methods Inspired from Cultural Heritage

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 162-174

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 204-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 1-12

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Export citation

6 - Conclusions

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 175-177

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

About the Authors

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- The Art of Inpainting

- Published online:

- 22 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 183-203

-

- Chapter

- Export citation