Refine search

Actions for selected content:

37426 results in Art

6 - The Library Through a Workplace Lens: A Conversation with Neil Everitt

-

- Book:

- Privileged Spaces

- Published by:

- Facet

- Published online:

- 20 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 87-100

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Reviews

-

- Book:

- The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science

- Published online:

- 29 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp ii-ii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures and Tables

-

- Book:

- Privileged Spaces

- Published by:

- Facet

- Published online:

- 20 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Two - Devising the Architectura: Rationalism and Empiricism in Architectural Design

-

- Book:

- The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science

- Published online:

- 29 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 103-168

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - ‘Selling’ the University: The Role of the Academic Library

-

-

- Book:

- Privileged Spaces

- Published by:

- Facet

- Published online:

- 20 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 73-86

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science

- Published online:

- 29 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Encounters in Theatre and Liberature

- B. S. Johnson and Zenkasi

-

- Published by:

- Jagiellonian University Press

- Published online:

- 18 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023

Eastern Drama of the Absurd in the Twilight of the Soviet Bloc

-

- Published by:

- Jagiellonian University Press

- Published online:

- 18 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2023

Conflict and Development in Iranian Film

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 18 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 December 2012

-

- Book

- Export citation

Infrastructural Times

- Temporality and the Making of Global Urban Worlds

-

- Published by:

- Bristol University Press

- Published online:

- 18 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2024

Belarusian Theatre and the 2020 Pro-Democracy Protests

- Documenting the Resistance

-

- Published by:

- Anthem Press

- Published online:

- 18 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 April 2024

Abundance and Fertility

- Representations Associated with Child Protection in the Visual Culture of Ancient India

-

- Published by:

- Jagiellonian University Press

- Published online:

- 18 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 September 2023

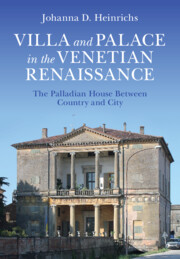

Villa and Palace in the Venetian Renaissance

- The Palladian House Between Country and City

-

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025

Foreword

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp xiii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp 161-176

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp ix-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp 177-184

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Afterword

-

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp 155-159

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Timelessness and Permanence

-

- Book:

- Aboriginal Rock Art and the Telling of History

- Published online:

- 12 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp 126-149

-

- Chapter

- Export citation