Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60613 results in Classical studies (general)

The Aegean Civilizations - P. Warren: The Aegean Civilisations. Pp. 152; 175 illustrations (145 in colour). Oxford: Elsevier-Phaidon, 1975. Cloth, £3·95.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 234-236

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Erich Bayer and Jürgen Heideking: Die Chronologie des perikleischen Zeitalters. (Erträge der Forschung, 36.) Pp. xii + 225. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1975. Wrappers, DM. 34. (DM. 19.50 to members).

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 300

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Günther Zuntz: Die Aristophanes–Scholien der Papyri. Pp. 133; 6 plates. Berlin: Richard Seitz, 1975. Paper, DM.36.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 271

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Irish Exotica - Michael W. Herren: The Hisperica Famina: I. The A-Text. Pp. 234. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1974. Cloth, $ 11.50.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 196

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Timoleon - R. J. A. Talbert: Timoleon and the Revival of Greek Sicily 344–317 B.C. (Cambridge Classical Studies.) Pp. xii + 235. Cambridge: University Press, 1974 (1975). Cloth, £5.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 217-218

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Books Received

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 330-335

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Victor J. Matthews: Panyassis of Halikarnassos: Text and Commentary. Pp. xii + 158. Leiden: Brill, 1974. Paper, fl.52.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 268-269

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

G. Roger Edwards: Corinth VII.3: Corinthian Hellenistic Pottery. Pp. xviii + 254; 86 plates. Princeton, N.J.: American School of Classical Studies, 1975. Cloth, $35.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 306

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

John Park Poe: Heroism and Divine Justice in Sophocles' Philoctetes. Pp. 51. Leiden: Brill, 1974. Paper fl.18.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 270-271

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

M. Hellewell: A Book of Topical Latin Verse. Part 2, with introduction, some translations, paraphrases and notes mainly in English. Pp. 76. Stradbroke Lodge, Burnley Road, Sowerby Bridge, West Yorkshire HX6 2TB: published by the author, n.d. Paper, £1 + postage (3 oz. = 85 gms).

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 328

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Louis E. M. Alexis: School of Nero. Pp. xi + 112; 2 pp. illustrations. Sevenoaks School, Kent: the author, 1975. Stiff paper, £8·50.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 279-281

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Carol Dana Lanham: Salutatio Formulas in Latin Letters to 1200. Syntax, Style, and Theory. Pp. xi + 140. Munich: Bei der Arbeo-Gesellschaft, 1975. Paper, DM. 20.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / October 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 322

- Print publication:

- October 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Spartan Austerity

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 111-126

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Euripides, Heraclidae 147–50

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, p. 236

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

CAQ Volume 27 issue 1 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. f1-f2

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Callimachus, Iambus IV FR 194, 100(Pfeiffer)

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 237-238

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Language of Odyssey 5.7–20

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 1-9

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

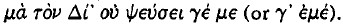

Four Emendations In Aristophanes

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 73-75

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Statius' Silvae in the Fifteenth Century

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 202-225

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

Horace A.P. 128–30: The Intent of the Wording*

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / May 1977

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 191-201

- Print publication:

- May 1977

-

- Article

- Export citation

. For I doubt if they expect that, in your right senses, you would, etc’ For the alleged impersonal use of

. For I doubt if they expect that, in your right senses, you would, etc’ For the alleged impersonal use of  (‘employed in a sense similar to that of our colloquial to come off, Pearson) editors can quote only two passages of Aeschylus, which I transcribe from Page's text: Su. 527–8

(‘employed in a sense similar to that of our colloquial to come off, Pearson) editors can quote only two passages of Aeschylus, which I transcribe from Page's text: Su. 527–8

, Ch. 378–9

, Ch. 378–9  (‘non intellegunturjmutilum esse iudico inclusis scholiorum fragmentis’, Page).

(‘non intellegunturjmutilum esse iudico inclusis scholiorum fragmentis’, Page). .

.  and a wreath is put on his head, which makes him feel like a sacrificial victim. In 261 he is told to hold still, and we gather from

and a wreath is put on his head, which makes him feel like a sacrificial victim. In 261 he is told to hold still, and we gather from  that at this point he is being sprinkled with some dry substance. If we put the full stop at the end, he is saying, ‘I can see you won't disappoint me: being sprinkled like this will make me into flour all right’. If we make it a question, it is ‘No fear, you won't trick me: you mean being sprinkled is the way to turn into flour?’ This seems more in keeping with his apprehension in 257, and it allows what is perhaps a more natural sense to

that at this point he is being sprinkled with some dry substance. If we put the full stop at the end, he is saying, ‘I can see you won't disappoint me: being sprinkled like this will make me into flour all right’. If we make it a question, it is ‘No fear, you won't trick me: you mean being sprinkled is the way to turn into flour?’ This seems more in keeping with his apprehension in 257, and it allows what is perhaps a more natural sense to