Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60709 results in Classical studies (general)

ABOUT AN EARLY FEMALE CLASSICIST - (D.N.) Greenwood Steely-eyed Athena. Wilmer Cave Wright and the Advent of Female Classicists. (Cambridge Classical Journal Supplement 44.) Pp. viii + 150, ills. Cambridge: The Cambridge Philological Society, 2022. Cased, £60. ISBN: 978-1-913701-42-0.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 73 / Issue 1 / April 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 November 2022, pp. 337-339

- Print publication:

- April 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

‘UNFINISHED’ BUILDINGS - (B.) Geißler, (U.) Wulf-Rheidt (edd.) Aspekte von Unfertigkeit in der kaiserzeitlichen Architektur. Ergebnisse eines Workshops am Architekturreferat des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, 26. und 27. September 2016. (Tagungen und Kongresse 1.) Pp. vi + 109, b/w & colour ills. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2021. Paper, €39. ISBN: 978-3-477-11739-5.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 73 / Issue 1 / April 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 November 2022, pp. 292-294

- Print publication:

- April 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

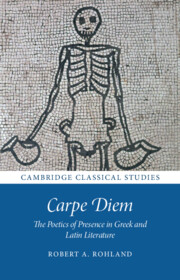

Carpe Diem

- The Poetics of Presence in Greek and Latin Literature

-

- Published online:

- 18 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 01 December 2022

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Xenophon's Anabasis

- A Socratic History

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 18 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 30 June 2022

1 - Hieradoumia

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 1-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp v-v

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Household Forms

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 146-193

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - City, Village, Kin-Group

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 319-356

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Circulation of Children

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 194-215

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp xiii-xvii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp x-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Village Society

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 284-318

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Beyond the Family

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 216-240

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Demography

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 72-102

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Commemorative Cultures

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 25-71

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp vi-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Kinship Terminology

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 103-145

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Lives of Ancient Villages

- Published online:

- 28 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 378-382

-

- Chapter

- Export citation