INTRODUCTION

Over the last four decades, at least 118 countries adopted new constitutions, often accompanied by popular expectations that political and civil rights would improve. Constitutions have actually had inconsistent effects on democratization, depending on which democracy indicator one uses. Out of the 138 new constitutions adopted in these countries between 1974 and 2011, the Polity score shows that the level of democracy increased in 73 cases but it actually decreased or stayed the same in 45 others. The Unified Democracy Score (UDS), on the other hand, shows an increase in the level of democracy for 51 cases and a decrease in 72 others.Footnote 1 Not all constitutions necessarily intend to advance democracy, but even among those countries that followed an overall democratic trajectory during this period, the empirical record is mixed.

What explains the inconsistent effects of constitutional change on democracy? Using an original dataset and multiple measures of democracy, we test the proposition that the role of ordinary citizens explains the divergent effects of new constitutions. This is an important issue because citizens’ right to participate in crafting the rules that will bind them has emerged as an international norm, and the Third Wave of democratization increased expectations for citizens’ civic involvement. For example after South Sudan became the world's newest country in 2011, citizens argued that crafting a constitution required broad public participation because “citizens are the government.” Respondents in a study declared, “We, the citizens, should be involved in writing the constitution because without involving us, we shall say it was a decreed constitution,” while others asserted that important public decisions cannot be left to elites (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Moro and Lo-Lujo2013, 11–2). Their former compatriots to the north, in Sudan, similarly insisted that “constitution-making is not just a technical work that leads to the formulation of a legal document, but is rather a process requiring comprehensive, collaborative, and transparent social dialogue that excludes no one.”Footnote 2 Constitutional referendums are another sign of this increase in citizen participation: there were more referenda (192) on new constitutions between 1974 and 2012 than over two previous centuries (117).Footnote 3 But despite “very strong recommendations for extensive popular participation” in constitution-making, Horowitz recently asserted “there is not even a scintilla of evidence that it improves the durability or the democratic content of constitutions” (Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Fukuyama, Horowitz and Plattner2014, 100).

In this article, we offer that “scintilla.” We demonstrate how the level of participation in the constitution-making process systematically explains the observed disjuncture between constitutional change and democratization since 1974. Using original participation measures, our cross-national time-series analysis offers strong evidence that constitutions crafted with meaningful and transparent public involvement are more likely to contribute to democratization. Then, after disaggregating the constitution-making process into three stages, our tests show that the degree of citizen participation during drafting has greater consequences for democratization than subsequent “debate” and “ratification” stages. This challenges Elster's claim that “ratification by the citizens, following a national debate, is more important” than direct citizen input during drafting (Elster Reference Elster, Landemore and Elster2012, 169). Since few of the public's substantive ideas survive in the final draft, he suggests the public's role should therefore be “hourglass-shaped” because the anticipation of broad ratification influences (and presumably moderates) constituent assembly debate. Our finding is also important because post-1980s democracy promotion has focused on later stages rather than formative moments when political context can impede or enable constitutions’ democratizing effects. In other words, ratification procedures during the final stage only of constitution-making may offer more symbol than substance. For the reasons outlined by Sudanese citizens above, “buy in” at the front end needs to complement legitimation at the “back end.” Moreover, failure to incorporate societal input into constitution-making may be considered an “original sin” not rectified by getting that input later in the process.

We review literature on the consequences of constitutional change. Democratization research advanced plausible theories about the benefits of participatory constitution-making, but has not rigorously tested these. Comparative constitutionalism has yielded conflicting conclusions about the effects of constitutional change on democracy. A brief discussion about what constitutes constitutional change draws on classic philosophical debates, informs the subsequent task of operationalizing change, and also identifies the right to participate as a global norm.

Second, to explain how and why modalities of making constitutions should have a lasting political impact, we outline developments in democratic theory. Participatory models of democracy argue for direct citizen engagement to remedy defects of representation, often by increasing opportunities for citizens to vote on policy (Pateman Reference Pateman2012, Reference Pateman1970). These models thus challenge notions of trusteeship, delegation, and elitism. Deliberative models also worry about failures of representation, but assert that direct participation through public debate is more important than voting for deepening democracy. Our “participation” hypothesis then posits that high levels of participation throughout the constitution-making process overall will positively impact democracy, and an “origination” hypothesis predicts that citizen involvement in the earliest stage has a larger impact on democratic outcomes.

Third, we describe extant data sets, our data collection strategy, and the research design for testing impacts of participatory constitution-making on democracy. We detail the construction and coding of our process variable for measuring participation, including the rationale for breaking constitution-making down into three broad stages. We identify “control variable” factors such as economic development, ethnic diversity, natural resources, and foreign aid that could interfere with the predicted relationships and adopt standard proxies for these.

Fourth, we test for the effects of participatory constitution-making on democracy, as measured by the Unified Democracy Score (Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Meserve and Melton2010) and Polity IV (Marshall and Jaggers Reference Marshall and Jaggers2008). The first stage tests the process variable, confirms the participation hypothesis, and withstands robustness checks. A further probe for potential endogeneity validates our claim that process does indeed distinctly measure participatory constitution-making. Next, we confirm the deliberative hypothesis through tests using the three stages of constitution-making as separate independent variables.

We conclude that the results offer an important corrective to the democratization literature since the modality of constitution-making matters much more than the mere promulgation of a new constitution. More generally, in contrast to legalistic studies arguing that wording of constitutions shapes institutional outcomes, we show, perhaps for the first time, that arriving at this language via democratic process is also vital. By conducting one of the first large-scale empirical analyses of participatory constitution making, we show that transparent, meaningful input during “constitutional moments” generates vital path dependent benefits for “back end” democracy. By specifying that citizen participation during drafting is the most important, we raise doubts about the lasting benefits of referenda—the hallmark of the ratification stage during the Third Wave and a preferred device for democracy promoters. Voting via referenda and faith in constitutional texts offer poor substitutes for deliberation and inadequate insurance against authoritarian retrenchment. After nearly a decade-long global decline in democratic freedom (see Freedom House 2015), this is an important lesson for political reformers who seek political insurance against illiberal reversals and authoritarian backsliding.Footnote 4

LITERATURE REVIEW

How do citizen participation and the modalities of citizen input affect nations’ levels of democracy? To date, comparative constitutionalism and several significant, related literatures have addressed this fundamental question indirectly, incompletely, or through case studies that offer little basis for generalization. The limited treatment of this question by democratization researchers is surprising given the boom in transition studies in the 1990s. At the time, constitutional change and democratization were often mistakenly conflated, when in fact constitutional replacement occurred within a year of only 19 percent of transitions to democracy and in 27 percent of transitions to authoritarianism (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009). Various studies developed sound theoretical propositions regarding the broader political impact of participatory constitution-making but these ideas were not fully tested, even as international norms of citizen involvement took hold. This literature review discusses these issues and research on constitutional endurance, content, and compliance, to inform how we might expect modalities of constitutional change to impact democracy.

In the most rigorous and systematic exploration of the political effects of new constitutions, an ongoing project by Elkins, Ginsberg, and Melton considers constitutional survival. Their study, testing 935 cases spanning two centuries, concludes that more participatory processes are conducive to constitutional survival because they “can promote a unifying identity and invite participants to invest in the bargain” (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 211). A related study reports that inclusive drafting increases the likelihood of constitutional endurance, and is associated with constitutional rights and democratic institutions such as universal suffrage, the secret ballot, and a guaranteed role for public input into amending constitutions (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2012, 54–7). These are seminal findings regarding endurance and content, but they leave unanswered the impact of processes on levels of democracy and de facto protections of rights—as opposed to the de jure protections mentioned in the text itself.

Widner's data-rich research measures participatory constitution-making, but like Elkins et al. it lacks a direct test of participation on level of democracy. Her “Constitution Writing and Conflict Resolution” data set covers 195 constitutions between 1975 and 2002 (Widner Reference Widner2004). Her results show that public consultation does not correlate with improved political rights protection (Widner Reference Widner2008). This finding conflicts with an influential analysis of 12 countries by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (Samuels Reference Samuels2006), as well as 18 case studies of constitutional change in transitional states (Miller and Aucoin Reference Miller and Aucoin2010). However, neither study systematically examines democratization or political rights as a dependent variable.

One study that does conduct direct statistical tests of constitution-making on democracy is Carey's (Reference Carey, Barany and Moser2009). He finds that more “inclusive” constitutional drafting increases the level of democracy over the subsequent three years, as measured using Polity IV data on democracy and executive constraints. However Carey concedes that his bivariate analysis is bound by data constraints, including the use of proportional representation as a proxy for the inclusiveness of institutional actors. These limitations deter him from using standard statistical models that would provide a stronger basis for broader generalization. In sum, to our knowledge, no study tackles the relationship between constitution-making processes and democratization using robust cross-national quantitative analysis.

The dearth of empirical studies of constitution-making processes and democratization is surprising for three reasons: first, because numerous theories expect participatory politics to benefit democratization. Lindberg (Reference Lindberg2009) argues that elections improve levels of democracy over time as the civic ritual of voting is repeated: going to the ballot box places expectations on politicians and educates citizens and, therefore, becomes a means of developing a democratic political culture. Hyden argues that constitution-making is even more of a change agent for ordinary citizens than elections. He predicts that broad-based and participatory constitutional processes will give African countries “better prospects of succeeding with their regime transition than countries where such an exercise has not been carried out” (Hyden Reference Hyden, Hyden and Venter2001, 216). Moehler (Reference Moehler2008) arrives at a surprising finding in Uganda, where participation in constitution-making educated citizens about democracy but also made them skeptical (perhaps constructively so) about government. Wing's study argues that participatory constitution-writing helps nations avoid violent conflict, build democracy, and significantly foster legitimacy (Wing Reference Wing2008). Though they do not test for it, Elkins et al. similarly observe that, “sometimes, we suspect, the process of re-writing higher law can be therapeutic and empowering for citizens and leaders” (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 209).

Second, the political impact of constitutions and citizens’ right to craft them relates to classic legal debates about “legitimate” sources of institutional change. One view among some constitutionalists takes the law as a necessary prior for political pluralism (Hatchard et al. Reference Hatchard, Ndulo and Slinn2004; Levitt Reference Levitt2012). This can lead to an unnecessarily narrow institutionalist perspective that leaves each constitutional text to “speak for itself,” blaming weak compliance on stochastic factors such as quality of leadership. This approach also understates prospects for stable—but illegitimate—institutions. More importantly, by focusing on legal lineages rather than the political context of constitution-making, such arguments ascribe little agency to “bottom up” pressures characteristic of numerous democratic transitions (Bratton and Van de Walle Reference Bratton and Van de Walle1997; Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011; Teorell Reference Teorell2010). Thus our understanding of constitutional change needs to accommodate important global shifts in the cosmopolitan and civic sources of law driven by democratization. To this end, numerous contemporary constitutionalists defend a people's right to rewrite the rules (Holmes Reference Holmes, Slagstad and Elster1988; Mutunga Reference Mutunga and Oloka-Onyango2001), suggesting that constitutions themselves can serve as agents of change by reflecting underlying societal transformations.

Third, limited comparative information about these processes is surprising because many scholars argue that a legal norm guaranteeing a right to participation in international law has emerged (Fox Reference Fox, Fox and Roth2000; Miller and Aucoin Reference Miller and Aucoin2010). The International Monetary Fund in 2014 instituted new transparency codes to this effect, and citizen participation is now integrated into the World Bank's Demand for Good Governance. The United Nations Secretary General cites recent comparative examples to argue for “inclusive, participatory and transparent constitution-making processes.” Reflecting Hyden's logic, processes can foster civic engagement and raise citizen expectations for government transparency (United Nations Secretary-General 2009, 4). Even without “uniform norms” for constitution-making, international law over the last half century has supported “a general requirement of public participation” extending to citizen involvement in “the actual process of drafting the constitution's final text” (Franck and Thiruvengadam Reference Franck, Thiruvengadam and Miller2010, 14).

In sum, despite sound theoretical justifications for participation in the democratization literature, four decades of democratic transformations, and the emergence of strong international norms, we still have a weak empirical basis for assessing the value of direct citizen input into constitution-making. While underdeveloped in the literature, as we have shown, three broad explanations exist for the effects of participatory constitutional change, where citizens are actively engaged in the process, on levels of democracy. First, as per legalistic constitutionalism, changes in the text itself from such citizen involvement might yield a more “legitimate” and thus more readily supported democracy. Second, a more institutional argument might imply that something about the process of consultation itself may generate a more participatory government. Third, a political culture explanation might claim that participation in the constitution-making process might yield a more democratic citizenry over time. We argue broadly in favor of the second argument—the institutional explanation—for reasons noted in the discussion of our hypotheses, which are elaborated below. Upon showing that participation in the constitutional process matters far more in the initial stage of constitution-making, we argue that this “origination” moment is when democracy-promoting elites can obtain “buy in” from a wide swath of societal groups, whereas authoritarian and hybrid regimes, seeking to “window dress” as democrats, also signal their intentions to steer any new social pact from above.

MODALITIES OF CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES

Democratic theory co-evolved alongside democratization itself over the last four decades to increasingly examine procedures that promote consent and challenge elitist, delegative, and rational theories of democracy as incomplete. The “participatory” model of democracy prominently associated with Pateman (Reference Pateman1970) argues for direct citizen engagement to extend representation and remedy defects of pluralist democracy, where lobbyists, interest groups, or elite-run parties marginalize often popular policy preferences. Such critiques have garnered credibility through innovations like Brazil's celebrated “Porto Alegre Experiment” in participatory budgeting that integrated the poor into resource distribution decisions (Pateman Reference Pateman2012). Skeptics characterize the participatory model as normative, impractical due to problems of scale, or over-reliant on referenda that reinforce the status quo (von Beyme Reference von Beyme, Alonso, Keane, Merkel and Fotou2011). Nevertheless, “the direct incorporation of citizens into complex policy-making processes is the most significant innovation of the third wave” (Wampler Reference Wampler2012, 667). More than merely a normative good, evidence also suggests that participation improves the quality of public goods provision by creating a “virtuous cycle” (Touchton and Wampler Reference Touchton and Wampler2013).

An alternative theory claims “the essence of democracy itself, is now widely taken to be deliberation, as opposed to voting, interest aggregation, constitutional rights, or even self-government” (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000, 1). This “deliberative” model of democracy shares participatory democrats’ concerns about the limits of representation, but it differs by claiming that increased opportunities to vote through ballot initiatives or other means cannot remedy defects of representation. For starters, voting is a weak expression of consent that reduces democracy to the aggregation of preferences. Deliberative models insist that democracy must also be about noncoercive opportunities to change preferences (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000). The very setting of deliberation “can shape outcomes independently of the motives of the participants,” notes Elster (Reference Elster and Elster1998, 104). In addition, voting entails delegation to politicians rather than participation. This gives politicians incentives to be untruthful or vague to increase their appeal. While rational choice theory asserts that public discussion cannot remedy this because “talk is cheap,” deliberative democrats argue that discourse is just as likely to be true as false. They further stress that repeated contact raises the cost of deception; rational assumptions of single iterations simply do not hold up (Mackie Reference Mackie2003). This is not to say that deliberative models wholly dismiss voting. Urbinati and Warren (Reference Urbinati and Warren2008) suggest that aggregation – i.e., making valid inferences about public opinion by adding up individual preferences – contributes to national unification, for example. But one must still confront the underlying “crisis of representation” (Avritzer Reference Avritzer2012, 14).

When formal representative institutions fail, deliberative theory says that “self-authorization” may occur (Urbinati and Warren Reference Urbinati and Warren2008). Such instances of ordinary people collectively deciding to shape rules or make otherwise publicly binding decisions are often limited to specific policy areas, suggesting—perhaps—that deliberative theory concedes the ability (or right) of people to participate in the primitive stages of complex tasks as limited. Yet even moderate deliberative democrats argue that deliberation is vital in addressing “great crises” such as constitution crafting (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000); deliberative rights and abilities are not limited to narrow tasks. Deliberative democrats do allow room for experts, since complex tasks require divisions of labor. But deliberative theory seeks to protect against forms of delegation to experts that “can promote citizen ignorance, with highly negative consequences for the system as a whole,” and also to show how excluding nonexperts “threatens the foundations of democracy itself” (Mansbridge et al. Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012, 14–5). Fishkin's (Reference Fishkin2009) rule of thumb is for citizens to debate ideas and information in a public space based on their merits rather than the social standing of the articulator. Complex decision making may need experts, but preferences should be weighed independently of who offers them, meaning that expertise should not become a back door for exclusion or de-legitimation of certain views.

In sum, participatory models maintain that direct, ongoing citizen input can remedy representative democracy's tendency to favor elite input and privilege the role of parties and interests at the expense of ordinary citizens. Moreover, empirical evidence exists that participation generates a “virtuous cycle” that actually improves policy performance (Fox Reference Fox2014). Deliberative models worry that this view of democracy focuses on preference aggregation at the expense of preference transformation, and that voting contributes to representation via delegation with weak expressions of consent. Deliberation can remedy these defects by correcting for insincerity, supposedly unequal abilities, and information asymmetries. If deliberative procedures in effect matter more than the text, then talk is not “cheap”—it is in fact what generates and protects democracy.

Participation and Deliberation Hypotheses

How has citizen participation in constitution-making actually impacted democratization? Are the peoples’ passions to blame for recent authoritarian retrenchment? To address these issues, we formulate two broad hypotheses about the effects of direct citizen involvement in constitution-making. First, a “participation” hypothesis posits that high levels of participation throughout the process will positively impact democracy. It begins from participatory democracy's critiques of representation and interest group pluralism and supports direct citizen engagement through civic activities including increased opportunities to vote (Pateman Reference Pateman1970; Reference Pateman2012). Confirmation of this hypothesis would support the democratization literature's contentions that constitution-making prevents authoritarian backsliding when major stakeholders “practice” democratic habits and thus generate lasting positive impacts on democracy.

Should tests reveal no significant correlation between participatory constitution-making and democracy postpromulgation, this would justify skepticism about benefits of direct citizen input and effectively defend elitist notions of governance through trusteeship. For example, Edmund Burke's “true principles of government” asserted that government is not made from natural rights. He argued that liberty requires citizens’ surrender to the paternalistic state and subdue their “passions” for their own benefit (Burke Reference Burke1999). Some theorists today similarly claim that despite the inclusive ambitions of deliberative models, elite innovations matter more in governance bodies that mistake stakeholder involvement for increased political inclusion (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). To wit, Horowitz argues that “insiders” crafted a “more democratic (and more effective)” constitution in Indonesia than the one that would have likely emerged from a more consultative and participatory process (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013, 4).

Second, an “origination” hypothesis builds on deliberative democracy's core principles. Voting may be an integral component of modern democracy, but it must be more than a veil of delegation or merely an exercise in aggregation. Participation without direct and inclusive deliberation cheapens democracy and enables elitist notions of representation. We seek to explore whether direct citizen involvement at the original, earliest stage of constitution-making has a larger impact on outcomes than the process for approving the final product. If there is more to public participation than simply voting on a constitution, then this raises questions about ratification in particular. At this stage, voters are easily misled by referendum language and elites spend huge sums to influence public opinion, creating information asymmetries as barriers to citizen input (Catt Reference Catt1999). Mansbridge et al. offer an explanation for why different stages might have different effects: when parts of a deliberative system are “too tightly coupled to one another,” group-think, such as xenophobic feelings, can contaminate judgment in another part. Conversely, if the parts are decoupled, sound reasoning from one part of the system might not carry over to others (Mansbridge et al. Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012, 22–3). The debating stage could also have positive, lasting effects on democracy, and constitution-makers may of course “deliberate” in the colloquial sense at different stages. But we think the origination stage of constitution making provides a tougher test since drafting ostensibly entails technical legal skills that make the public willing to defer to experts. Moreover it may be challenging for ordinary citizens to assert a right to participation so quickly, without much opportunity to organize.

We therefore hypothesize that direct and extensive citizen input during “origination” (its theoretical label, but the stage will also go by its procedural label “drafting”) is self-empowering. As constitution-making progresses elites cannot hide behind prestige or technical expertise as citizen participants monitor the process itself. The text is then more likely to be assessed on its merits, as Fishkin (Reference Fishkin2009) urges. In other words, how the text is considered has an impact on democratic outcomes (though in our tests we consider text substance itself as well). Establishing a precedent for citizen input also helps neutralize constitutional “self-dealing,” as elites cannot easily modify the rules of the game as they are playing it (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009). Hence, their true intentions are in evidence at the moment of “origination,” when out-of-power actors in society have to decide whether to vest themselves in a process which may improve democracy, but at the very least will legitimize whatever rulers remain in power at promulgation. Further, confirmation of the origination hypothesis would validate theoretical claims about lasting benefits of participation (Hyden and Venter Reference Hyden and Venter2001; Wing Reference Wing2008) and the very right of people to participate (Franck and Thiruvengadam Reference Franck, Thiruvengadam and Miller2010; Holmes Reference Holmes, Slagstad and Elster1988).

Rejection of either one of these hypotheses would suggest that the modality of making a constitution is less important for subsequent democratic development than the substantive text itself or various contextual elements (such as strong ethnic or religious cleavages, or a restrictive political culture). Neither hypothesis here presents an explicit, comprehensive test of the participatory and deliberative models of democracy. But they do draw upon the models’ respective core principles relating to the extent of direct of citizen involvement, inclusion, the role expert interpretation, and voting when all citizens have a stake. And we argue that they do disconfirm claims of the “legal constitutionalists” that changes in the text themselves are determinant and locate the agency in the realm of incumbent signaling and the elaboration of democratic institutions, through mechanisms we consider in the discussion using concrete cases from the Middle East and Latin America.

DESIGNING A CONSTITUTIONALISM AND DEMOCRACY DATABASE

To generate our independent variables and include relevant controls, we constructed a “Constitutionalism and Democracy Database” (CDD) covering the 190 countries with available data between 1974 and 2011. The CDD builds on two extant data sets by Elkins et al. (Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009) on the survival and legal scope of constitutions from the beginning of the 20th Century, and by Widner (Reference Widner2004) on the political processes yielding new constitutions and constitutional reforms since the 1970s. In this section we describe different approaches for measuring constitutional change and adopt a high threshold for coding a constitution as “new.” Next, we break the constitution-making process into drafting, debating, and ratification stages. We then describe how we measure levels of participation at each stage, which we code as “decreed,” “polyarchic,” or a mixture of the two. This generates a process variable measuring overall participation levels which can be disaggregated into each of the three stages.

What Counts as Constitutional Change?

Distinguishing “new” constitutions from amended older ones is not entirely straightforward. Zambia's shift from one party rule to multiparty competition in 1991 or former President Hugo Chávez's 2009 reform of the Venezuelan constitution to allow himself additional terms are arguably the equivalent of new constitutions—even without wholesale redrafting and promulgation. Widner (Reference Widner2008) considers such cases “regime-changing amendments” amounting to new constitutions because they significantly impact civil and political liberties, ethnic or regional autonomy, or property rights. Banks and Wilson (Reference Banks and Wilson2005) similarly include constitutional amendments that reorder prerogatives of different branches of government, such as switching from presidential to parliamentary executives. What counts with these approaches is the content of the constitutional changes. Alternatively, Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Elkins and Ginsburg2011) consider how reforms impact executive power and whether constitutional change took place outside of procedures specified in existing constitutions. This builds on Elkins et al.'s operational definition, that constitutional change adhering to existing amending procedures is coded as an amendment. Their extensive content analysis reports that replacements match parchment predecessors in 81 percent of the topics (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 55–9).

To reduce subjectivity in classification, the CDD applies a narrow definition of change counting only constitutions resulting from explicit promulgations. We identify these discrete political moments from the above datasets, secondary sources listed below, and from promulgation dates in constitutional texts. Applying these criteria between 1974 and 2011 the CDD identified 118 countries that implemented at least one new constitutionFootnote 5 and approximately 72 countries that did not implement a new constitution. We start the data set in 1974 to include the Third Wave (38 years in our data set), encompassing transitions in the era of modern rights and constitutionalism, and because most needed data are available for this period.

Operationalizing Citizen Participation in Constitution-Making

After identifying the constitutions in our sample, constructing the process variable required breaking constitution making into stages, with the ability to measure level of participation separately for each one. Existing research often blends these stages with the degree of participation and the extent of inclusiveness. Widner (Reference Widner2004) measures the level of participation and representation in constitution drafting by coding five process characteristics: type of deliberative body, method of selecting delegates, method of choosing delegates who draft initial texts, level of public consultation, and existence of a public referendum. Unfortunately this ambitious study did not gather enough information for a comprehensive set of cases. Carey (Reference Carey, Barany and Moser2009) focuses singularly on “constitutional moments,” measuring inclusiveness with one variable that counts veto players and another indicating whether citizens voted on the constitution via referendum. Not only does this give us little leverage over discrete stages of the process, but veto players data exclude significant portions of the developing world (LeVan Reference LeVan2015). Elkins et al. break the constitution-making process into stages of writing, deliberation, and approval. They reduce the deliberation stage to whether an elected body publicly debated the draft, while the basis for variation at the approval stage is whether a constitutional referendum took place (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009, 97–9). They operationalize inclusiveness using two proxies: a variable for whether constitutions were drafted during foreign occupations and another for whether a country was democratizing at the time.

Following the broad outlines of Elkins et al., we separate the constitution-making process into three stages of drafting, debating, and ratification. However since level of democracy is our dependent variable, using their democratization variable would generate obvious autocorrelation. More importantly, our process variable strives to directly measure level of participation rather than relying on proxies. To accomplish this, we gathered information on levels and modalities of citizen input or elite control over constitution-making at each of the three stages.Footnote 6 The drafting stage includes activities in the constitution-making process related to selecting those actively and directly involved in crafting the constitution's content. We sought information about whether drafting was done by a previously elected body or a newly elected body, whether those elections were free and fair, and whether there were otherwise systematic opportunities for direct involvement of ordinary citizens rather than delegating to experts. The debate stage explores how decisions were made about content and retentions and omissions from the text. This entailed negotiations and efforts to transform participants’ preferences. The ratification stage entailed procedures for approving the constitution and making it binding for all citizens, including those who did not participate in its creation. If the constitution was approved through a national referendum, we also sought indications of doubts about the vote's credibility.

We then used this information to construct the umbrella process variable, coding each stage of constitution-making with one of three ordered values measuring participation levels. First, “decreed” indicates elite control of a nontransparent process through a strong executive, a committee appointed by the executive with no meaningful external consultation, or a party acting as a central committee. At the drafting stage, constitutions of the Dominican Republic (2010) and Morocco (2011) fit this mold since they were written behind closed doors with little public input. Drafters are often hastily appointed to preempt momentum for public input. Constitutions with decreed qualities at the debate stage include Lesotho's (1993) and Nicaragua's (1974). Similarly, China's 1978 constitution was a product of the Communist Party's closed discussions, and even when a new process in 1982 was opened to elites, we found no evidence that their participation significantly altered content. Countries such as Morocco (2011), Burma (2008), and Nigeria (1999) did not even bother to submit constitutions to referenda for public approval, classifying their ratification stage as decreed.

Second, “mixed modalities” captures cases with overlap or tension between elite and bottom-up influences, but we sought to avoid generating a residual category. Constitutions drafted with mixed modalities include Paraguay (1992), where drafters were elected but elites manipulated candidate selection or the electoral process. Similarly, Spain's constitution (1978) had strong democratic qualities but content was constrained by the elite pact shaping the transition. This also includes cases where a body previously elected for another purpose, such as a regular parliament, drafts a new constitution or appoints a committee. As Elkins put it, this generates the risk of “self-dealing.” At the debate stage, we sought processes that were partially public but lacked readily identifiable divergences from elite preferences as in Peru (1993), where an ad hoc subcommittee of the Democratic Constituent Congress passively received public input and communicated through regular radio broadcasts and press releases, but does not seem to have reckoned with public concerns about executive discretion following President Fujimori's “autogolpe” power grab. Burundi (1992) or Hungary (2011) epitomize mixed modalities at the ratification stage, where constitutions were approved by referenda—but were widely considered flawed.

Third, “polyarchic” participation refers to extensive and meaningful opportunities for broad sections of the public to directly shape constitution-making processes. As in Mansbridge et al., experts and elites still played important roles. But the risks of delegated authority were minimized through transparency, and leverage that ordinary citizens institutionally held. At the drafting stage, this occurred in cases such as Benin's Sovereign National Conference (1990) and Ecuador's recent (2008) constitution-making with extensive indigenous input. In some ten cases meeting these criteria at the drafting stage, a specially elected body drafted the constitution. At the debate stage, polyarchic participation typically involved a legislature or constituent assembly. But unlike with mixed modalities, civil society and ordinary citizens visibly influenced debates, undermining experts’ abilities to assert monopolies on constitutional wisdom, as in South Africa (1996). At the ratification stage, polyarchic participation is fairly common for the reasons we identified earlier: free and fair national referenda on constitutions legitimize them and their creation. Table 1 summarizes coding criteria and logical conditions. The CDD includes 134 cases at the drafting stage (with 4 missing values) and 133 at the debate and ratification stages (with 5 missing values in each).

TABLE 1. Coding Criteria

A practical issue at each stage concerned conceptual connections between representation and participation: a process could theoretically have an unrepresentative small subset of interests which vigorously and visibly participated; it could also be broadly inclusive but entail little meaningful participation. Though we do not have a separate variable measuring representativeness, we believe our approach is nevertheless an improvement over the use of proxies by extant studies. Our coding strategy is also consistent with Mansbridge et al.'s approach judging exclusion on the strength of justifications offered as well as public acceptance of rationales. Moreover, our search for elite control substantially overlaps with representativeness. Finally, using public signals of exclusion to gauge process inclusiveness is consistent with practitioner real world applications of concepts. For the Carter Center, for example, a participatory process “is one in which citizens are informed about the process and choices at stake, and are given a genuine opportunity to directly express their views to decision makers involved in the drafting and debating of the constitution” (Carter Center 2012, 5).

To characterize constitution-making processes, we assign process variable values on a scale ranging from 0 (“decreed” processes in all three stages) to 6 (“polyarchic” processes in all three stages). The average score is 2.5, indicating a mixture of “decreed” and “mixed” modalities. For an average country with a process score of 2.5, the Polity IV score is 1.6 (on a scale of −10 for most autocratic to +10 for most democratic). However, if a country uses an all “decreed” process, its average Polity score is −3.2 and if it utilizes an all “polyarchic” process, its average Polity IV score increases to +5.3. In other words, polyarchic constitutional processes do correspond with higher levels of democracy. Additionally, over time there is a slight increase in process scores even without changes in Polity IV scores. That is, the number of countries using “polyarchic” modalities increases as the process progresses. The resulting distribution is displayed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Process Variable

EMPRICAL TESTS OF PARTICIPATORY CONSTITUTION-MAKING ON DEMOCRACY

So does participatory constitution-making matter? And does it matter more at some stages of the process than others? In this section we answer affirmatively to each question. Statistical tests of the participation hypothesis regress the process variable on the postpromulgation level of democracy, measured at multiple intervals with the Unified Democracy Score and Polity IV. Endogeneity tests with an additional instrumental variable further our claim that process does indeed measure participatory constitution-making specifically. Next, two sets of tests of the origination hypothesis demonstrate that the earliest stage, drafting, has a greater impact on democratization than the debate stage or the modalities of ratification. Our results hold across a broad range of controls and robustness checks.

First Stage: Process Does Drive Democracy

In the first stage, we test the participation hypothesis, which states that high overall levels of participation throughout the constitution-making process positively impact levels of democracy. This builds on intuitions of the “bottom-up” literature discussed above, arguing that the grassroots basis for democratization has lasting benefits for democracy as well as for participatory models of democracy. To measure levels of democracy, we use the combined Polity IV score, a unified scale ranging from −10 (strongly autocratic) to +10 (strongly democratic). In a separate test, we use Pemstein et al.'s (Reference Pemstein, Meserve and Melton2010) Unified Democracy Score (UDS). The UDS weights multiple democracy indices according to their reliability. The UDS ranges from −2.11 (lowest) to +2.26 (highest) and covers all countries from 1946 to 2012. Both dependent variables are measured as three-year averages after the year of constitution promulgation (t) centered at year 2 (t+1 to t+3), year 5 (t+4 to t+6), and year 9 (t+8 to t+10), respectively. This provides a robustness check and shows the direction of change in democracy levels after constitutional promulgation, which is consistent for both measures of the democracy dependent variable. Hence, positive coefficients would support the participation hypothesis, stated as follows:

H1: Higher overall levels of participatory constitution-making increase levels of democracy.

The statistical models also include variables measuring a variety of social, economic, and historical conditions that could account for the hypothesized relationship. First, the ethnic ratio variable controls for ethnolinguistic diversity using Alesina et al.'s (Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003) data, with 0 indicating ethnic homogeneity and 1 representing significant fractionalization. This is important because ethnicity could impede democratization by breeding parochialism (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985), advance democracy by enabling civil society mobilization (Bessinger Reference Bessinger2008), or, consistent with Widner (Reference Widner2008), not affect impacts of constitutional change on political rights. Second, an Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) variable is used to control net foreign aid assistance, since high participation is an international norm (Franck and Thiruvengadam Reference Franck, Thiruvengadam and Miller2010) and countries more dependent on foreign aid might have more participatory processes. Similarly, countries with more natural resources are considered less dependent on the international community for assistance and perhaps thus may incorporate less participatory processes. As such, we also control for natural resource rent. We use the World Banks's World Development Indicators (2013) of official development assistance (ODA) as a percent of Gross National Product (GNP) and natural resource rent as a percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to control for foreign aid and natural resources, respectively. Each of our variables is measured as the average value for the three years before constitutional promulgation. Because modernization theory remains perhaps the most influential theory of democratization (Coppedge Reference Coppedge2012; Teorell Reference Teorell2010), we also control for level of development with GDP per capita. Next, as larger countries may be less likely to democratize due to population density or other factors (Teorell Reference Teorell2010), we include the natural log of population. These last two variables come from the World Bank's World Development Indicators (2013). We also include year of constitution promulgation to control for trend as participatory constitution-making has emerged over time as a norm (Franck and Thiruvengadam Reference Franck, Thiruvengadam and Miller2010). Finally, we control for a nation's geographical region using data from Norris (Reference Norris2008).

The results in Table 2 show that process has a positive and significant impact on all Polity and UDS three-year postpromulgation averages, and the model explains a good deal of variance.Footnote 7 The results also show that not only is this impact significant, but that the coefficients increase slightly over time. While natural resource rent is not statistically significant, aid dependence has a significant and negative correlation with democracy scores. In our OLS statistical tests, coefficients do not change significantly with changes in how democracy is measured. Of the dummies for region, only Asia has a positive and significant correlation with both Polity and UDS (t+1 to t+3 and t+4 to t+6 averages). The Middle East has a negative and significant correlation only with the UDS average of t+1 to t+3. This confirms Middle East scholars’ conclusions that in recent decades Arab states have grown rich in constitutions without necessarily growing richer in constitutionalism (Brown Reference Brown2002).

TABLE 2. Participation Hypothesis and Level of Democracy

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

Three caveats are in order. First, our case selection is nonrandom. The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression for the above estimate of the effect of constitution-making process on change in democracy score is

where yi is the change in level of democracy of a country and xi is the nature of its constitution making process. Information is available about the nature of constitution-making process only for countries choosing to write new constitutions. In other words, rather than forecasting outcomes for the universe of countries in our dataset, we must rely solely on a nonrandom subset of them. The “selection equation” for writing a new constitution might be

where Ui represents the utility to country i of writing a new constitution and ω i is a set of factors affecting a country's decision to adopt a new constitution, such as independence. For example, democratizing countries might be more likely to adopt new constitutions than old democracies. To test for selection bias, we run a Heckman selection model (see Appendix Table 5). We used new state—a binary variable indicating whether the country is a newly formed state such as the post-Soviet states—as our variable in the selection equation. The unit of analysis in the Heckman model is country rather than constitution. We included all dataset countries regardless of constitution adoption. For countries adopting more than one constitution during the 1974–2011 time period we included only the latest constitution. We could not reject the null hypothesis that there is no statistically significant difference between the coefficient of the Heckman selection model and the OLS model at a conventional level (ρ: 0.35). The model compares OLS coefficients with the Heckman corrections, showing that there is no statistically significant difference between coefficients of the two models. This is consistent with Elkins et al., who find constitutional replacement associated with regime change to be much less frequent than expected.

Next, we test for collinearity among independent variables. Collinearity could stem from the possibility that countries from certain regions utilize certain types of constitution-making process. It could also stem from foreign aid dependence that might have impacted citizen participation. We use two common indicators of collinearity—variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance—to detect potential collinearity. The mean VIF is 1.24, while the highest value of VIF and the lowest value of tolerance belong to GDP per capita (VIF = 1.4 and tolerance = 0.71).Footnote 8 This indicates that collinearity is not an issue in our models.

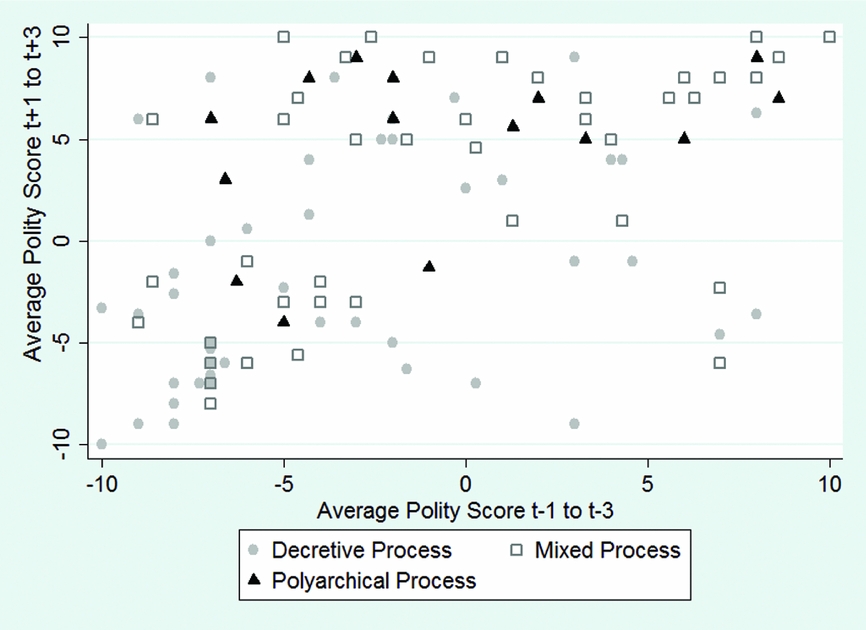

Finally, we address the endogeneity problem since democratic, open societies are more likely to use polyarchic means of creating constitutions. Tests for the correlation between democracy before and after promulgation show a significant correlation of 0.60 in Polity (−0.17 in UDS). However, as Figure 2 shows, the correlation between democracy before (t−1 to t−3) and after (t+1 to t+3) the constitution promulgation is not determinant of the type of constitution-making process. While decretive process is more likely in nondemocracies, polyarchical process is fairly universal across all levels of democracy. In fact, most cases that used polyarchical process had a negative Polity score before the constitution promulgation year (only 40% had a positive score), but that significantly changed after the promulgation year with 80% of those cases then having positive Polity scores.

FIGURE 2. Democracy Before and After Constitution Promulgation Based on Process

Yet, to account for any potential impact of before-promulgation level of democracy we include lagged values of the dependent variables in our models. We also stratify our sample by regime type using Cheibub's Democracy-Dictatorship binary variable (see Appendix Table 6). This solution diminishes our degrees of freedom, but the results show that deliberative constitution-making processes are even more effective in nondemocracies than in democracies. This confirms our finding that deliberative processes significantly improve levels of democracy. We finally use an instrumental variable to test for endogeneity. We use the sum of major national strikes in the three years prior to promulgation as an instrumental estimator for the process variable and run a two-stage least squares (2SLS) model, showing that strikes are as frequent in democracies as in nondemocracies.Footnote 9 Labor movements play an important role in recent transitions, usually through strikes and other means of mobilization (Collier and Mahoney Reference Collier and Mahoney1997). This indicates a close relationship among strikes, constitution-making, and democratic transitions over our study period. Citizens pressed challenges less as individuals than as groups (Diamond Reference Diamond1994). Labor unions played central roles in transition since through general strikes, they entered negotiations with authorities—negotiations often leading to more inclusion in political processes (Collier and Mahoney Reference Collier and Mahoney1997; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela1989). Hence, during times of transition, when constitutions are often crafted, strikes can impact democracy only through negotiating an inclusive political process. More strikes before constitution drafting indicates higher levels of citizen mobilization and a greater chance of polyarchic constitution-making. In other words, during transitions strikes affect the type of drafting process but affect democracy scores only through this drafting process.

To test for endogeneity, then, we construct a strikes instrumental variable from Banks and Wilson's (Reference Banks and Wilson2005) “general strikes” and run a two-stage least squares (2SLS) model using this variable. Since we are interested only in major national strikes, we use Banks and Wilson's (Reference Banks and Wilson2005, 31) “general strikes” including only strikes involving more than 1,000 workers and more than one employer and targeted at national government policies or authorities. We incorporated this estimate for the instrumental variable (IV), regressing it on our participation level process variable as the dependent variable in the first stage. Results from the first-stage of this two-stage least squares regression (reported in Appendix Table 7) show that the strikes independent variable estimate of the process variable (Polity IV) has a coefficient of 0.42 (and 0.46 for UDS) significant at .01 level. Thus, strikes has a positive correlation with process, indicating that the higher the number of strikes before constitution promulgation, the more polyarchical the process. In the second stage of the 2SLS model we substituted our process variable for the fitted value of strikes, now as the independent variable, regressing it on the Polity IV and UDS variables (see Appendix Table 8). The results are similar to our initial OLS coefficients, indicating that process variable variant endogeneity is not determinant. In other words, while strikes, a broader sign that civil society feels excluded from political processes (Mansbridge et al. Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012), impacted the constitution-making process, this instrumental variable impacted broad democracy outcomes only through constitution writing. The democracy outcome was not severely impacted by endogenous variables.

Second Stage: Democratic Drafting Matters for Democracy

We then test the origination hypothesis using the stages of constitution-making as three separate independent variables (drafting, debating, and ratification).Footnote 10 This is important because it explores whether the original sin of a nondemocratic drafting stage can be corrected by more participatory—and subsequent—debate and ratification stages, and therefore improve postpromulgation levels of democracy. Each stage of the process was coded for level of participation and participatory discussions may occur throughout. But we associate this hypothesis with deliberative democratic theory because meaningful public input at the earliest stage is least likely given the role of legal expertise that the literature associates with drafting. The basic hypothesis is stated as follows:

H2: Citizen involvement in the earliest “origination” stage of constitution-making (the drafting stage) has a greater impact on democratic outcomes.

In our first tests of the drafting stage, we run linear regression models showing that moving from a decretive drafting process to a polyarchical process increases the t+1 to t+3 average Polity score by 11.2 percent (or an average of 2.24, holding other values constant, on the −10 to +10 continuum). For t+4 to t+6, the average Polity score increases by 15.6 percent, and for t+8 to t+10 it increases by 14.1 percent. Each country also experiences a nearly 8 percent increase in all three-year averages of postpromulgation UDS scores (between 0.28 and 0.35 units on average, holding other values constant, on the −2.11 to +2.26 index). Recall that only 17 cases used polyarchic processes in the drafting stage, while 23 and 50 cases had polyarchic processes in the debate and ratification stages, respectively. Even given that fewer cases had polyarchic drafting than polyarchic debate and ratification, the results from Table 3 show that only in the origination stage, drafting, is the move from decretive to polyarchic process statistically significant. This is the central finding of our study. Polyarchy matters in drafting much more than in debate or ratification.

TABLE 3. Significance of Drafting, Relative to Debating and Ratification

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

Admittedly, this finding is driven by few cases which could raise the suspicions that outlying observations might drive the results. To ease this concern, we conducted further statistical tests. First, after running all our models, we generated standardized residuals. All standardized residuals fall in the range of +2.24 and −1.71 indicating no outliers in our models.Footnote 11 Second, we estimated the model using only covariates without missing data to see if we observed the same effects in the more comprehensive model (see Table 11 in the Appendix). Finally, we estimated the model using bootstrapped standard errors. As Table 12 in the Appendix shows, the results also held using bootstrapped standard errors. Together these tests help show that our findings are not driven by outliers.

With regard to our controls, aid dependence (ODA) had a negatively significant correlation with each democracy measure. The natural log of population, ethnic, natural resource rents, and GDP per capita all showed negative but insignificant correlations with both measures of democracy. The promulgation year variable had a positive and insignificant correlation with all Polity scores and the t+1 to t+3 average score of the UDS, but its direction changes for t+4 to t+6 and t+8 to t+10 UDS averages.

An alternative explanation suggests that the content of constitutions itself, rather the processes that designed it, has greater impacts on the levels of democracy. Such ideas are evident in recent research exploring the “congruity” of constitutional content (Galston Reference Galston2011), the impact of particular provisions on broader democratic accountability (Fombad Reference Fombad2010), or on constitutional endurance (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2012). We control for democratic content of constitutions using three proxies from the Comparative Constitutions Project dataset (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009): whether the head of state has decree power (HOS decree), whether the constitution places any restriction on the right to vote (Voter restriction), and whether the constitution contains provisions for a human rights commission (HR provision). Table 4 shows the results with controls for the content of constitutions included as independent variables. While the results for process and other variables do not change significantly (except for natural resources becoming statistically significant) from Table 3 when these “democratic content” variables are added, these content variables do not show any significant correlation with levels of democracy. The results show that process has more significant and positive impacts on democracy than constitution content. This further confirms our broader point that strong empirical evidence exists that the process of constitution-making has vital implications for improving a country's level of democracy.

TABLE 4. Impact of Process and Content of Constitutions on Democracy

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

As with the findings regarding the process variable in our earlier statistical findings, the drafting variable is robust in all cases when the process variable is disaggregated into three partials, while debate and ratification are not statistically significant. Hence we are able to rule out the broad “legalistic constitutionalism” hypothesis suggested in the literature review as a cause of democratic gains after some new constitutions. While we cannot definitively rule out changes in democracy levels brought by changes in political culture somehow set off by the constitutional process, our control variables related to political culture (regional dummies and ethnic division, for example) were not significant. A further argument against the agency of political culture in our model is that the results after t + 10 are quite similar to those at t + 1. In other words, the passage of time has no effect on changing political culture. Rather, we strongly believe that the changes in levels of democracy we identify which we can trace back to the origination (drafting) stage are due to the sorts of political institutions utilized by democratic reformer-driven processes as opposed to those managed by “window dresser” authoritarians. We offer contrasting ideal types using notorious authoritarian constitutional promulgations from Latin American history and a couple of participatory ones from the Arab Spring-era Middle East to illustrate our argument.

While not beyond critique (starting with Dahl Reference Dahl2001), modern democratic constitutionalism is said to have commenced with the U.S. promulgation in 1789. This republican (if not fully democratic) precedent created an expectations gap between the hopes of liberation-era reformers of Spanish America in the 1820s for enlightened postmonarchical rule, and their fears of anarchy, famously articulated by The Liberator himself, Simon Bolivar (“America is ungovernable; those who served the revolution have plowed the sea” as quoted in Liss and Liss Reference Liss and Liss1972). Their solution then (and followed by 35 data set constitutions such as Kenya 2010, Niger 2010, and Venezuela 1999), was to enact “dead letter” republican parchments, but with no implementation whatsoever, or, to our direct argument, no societal participation, to keep 19th-Century authoritarians from making “regimes of exception” the rule (Loveman Reference Loveman1993). Similarly, in 20th-Century Brazil authoritarians used constitutional processes as an “escape valve” for social tensions, but not as a means of constructing democracy (Stepan Reference Stepan1988; Veja 1980), and in 20th-Century Mexico, ruling party autocrats implemented one of the most progressive constitutions in the world (Hansen Reference Hansen1971, 90) but established metaconstitutional practices (Garrido Reference Garrido, Cornelius, Gentleman and Smith1989) and informal bargaining tables (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2004) to circumvent de jure dictates in favor of de facto elite practices. Indeed, Negretto's (Reference Negretto2014, 10) analysis of 194 post-independence constitutions in 18 Latin American nations shows that the pluralism of institutions in new constitutions depends on “whether the party that controls or is likely to control the presidency has unilateral power or requires the support of other parties to approve reforms.” In other words, from the top down, authoritarians and “hybrid regime” leaders sometimes must break political logjams by calling for new constitutions, but this may have nothing to do with democracy and everything to do with consolidating authority.

If these “stage managed” and unimplemented Latin American constitutions, mostly negotiated by military elites, dominant-party leaders, and other authoritarians (at least prior to the 1980s Third Wave opening), demonstrate the pattern of “top down” origination yielding little democracy, Benin 1990 and Greece 1975 (with +13 and +12.6 points increase in Polity score, respectively) embody the other extreme, polyarchical, participatory process yielding more democratic outcomes. In the most recent constitution in the world, Tunisia (as with 12 cases in our data set, including Colombia 1991, Portugal 1976, and Uganda 1995) opened the constitutional process in the hopes of strengthening their democratic institutions or building new ones (Maboudi, Forthcoming). Tunisian constitutionalist Habib Khedher (Personal communication, 22 January 2015), Secretary General of the Tunisian National Constituent Assembly's Constitution Drafting Committee, made the following point:

Right after the revolution, our main concern was how to avoid a return to the authoritarian rule. As such we decided to open the [constitutional] process from its initial stages because only an open, participatory process can secure a democratic transition.

A polyarchical process not only guarantees a democratic transition by including all groups, but also by checking the majority (Maboudi and Nadi Reference Maboudi and Nadi2014). “Bottom up” processes only balance power when opened at origination, however, because a closed process in the drafting stage, no matter how polyarchical it becomes later on, only includes certain groups and excludes others from participation in the first place.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

By demonstrating the central importance of the drafting stage, our results refute elitist Burkean notions of constitutional drafting via trusteeship. Our statistical results demonstrate first that constitutional change contributes to improvements in democracy in only half of all cases of constitutional promulgation during the Third Wave. This is important because despite democratic backsliding worldwide over the last several years we have learned little about conditions under which new constitutions effectively deepen democracy. Second, tests of our “participation” hypothesis demonstrate that increased public participation throughout the constitution-making process overall significantly contributes to levels of democracy at all three-year average intervals after promulgation. This offers empirical support for emerging international norms of participatory governance and for participatory models of democracy. Moreover, it shows that participatory procedure, rather than drafting particular language, matters.

Third, the results from our “origination” hypothesis generated the unexpected finding that drafting, which occurs earlier in constitution-making, has the greatest impact on subsequent levels of democracy. This is an important caveat to would-be constitutional engineers about the “original sin” of the drafting stage so clearly demonstrated here. More broadly, to the extent that our tests capture the essence of deliberative democracy, our results suggest that the model may be both more beneficial and more feasible than its critics contend. “The preconditions of free and equal discussion are much the same as the preconditions of free and equal voting,” argues Mackie (Reference Mackie2003, 387). Moreover, democracy promotion has often emphasized—even romanticized—referenda, which often take place only in the final stages of ratification. Indeed, democracy levels improved only in 45 percent of cases that incorporated broad consultation at debate and ratification stages, but not at the initial, drafting stage. Contrarily, 82 percent of the cases in our data which used polyarchic drafting, regardless of popular participation levels in later stages, show such improvement.

The few nations that do integrate polyarchic “bottom up” participation from constitutional process inception tend to involve more serious democrats, and by signaling this early, they vest other actors in the process which becomes a democracy-improving shared effort. Late entrants to polyarchic participation (73 in our sample), seeking to remedy their “original sin” of neglecting popular participation early on are more likely to fail. Contrary to Elster's “hourglass shaped” process amplifying the importance of approval procedures, our findings show that direct citizen input early might not matter much for the constitution's content, but it matters a great deal more than referenda for the kind of democracy that emerges. Since the components of a constitution-making process are “tightly coupled” in Mansbridge et al.'s terms, our evidence suggests that direct citizen participation early on increases the likelihood of positive spillovers later.

Extant single-country studies, such as the 19th- and 20th-Century Latin American cases briefly mentioned above, have exposed the vulnerability of constitutional processes to elite manipulation. While we have made important strides by identifying the overwhelming importance of participatory drafting in other cases, such as the Arab Spring's successes (to date) such as Tunisia, constitutional processes in specific cases at particular moments need to be further examined cross-sectionally and longitudinally. If the citizen engagement that brought down dictators has a mixed effect on the quality of constitutions and their enduring effects on political culture and rule compliance, this could influence both donor priorities and which processes of constitution-making are deemed most effective.

Our findings, while preliminary and imperfect, offer important conclusions useful to scholars and analysts seeking to understand the political effects of constitutions. They may also be used to improve levels of democracy using statistical analysis of the CDD in nations implementing new constitutions, as well as in carefully selected ethnographies of constitution-founding moments. We argue that the degree of participation by citizens is crucial to understanding whether constitutional change improves levels of democracy. Further research should merge procedural and substantive concerns by addressing not only whether and how citizens participate in drafting, debating, and ratification, but also how substantial this participation is in terms of proposing concrete language which otherwise would not have made the draft.

The strong call for greater participation emerging from this article should be joined by a call for “quality participation” rather than just populism. To this end the intentionality of incumbent rulers who “allow new constitutions”—dictated by the enablements and constraints they face—also merits much further study in order to more decisively conclude that these rulers’ initial permissiveness or even encouragement of broad participation is the mechanism behind the relationship between origination participation and improved democracy later. Several different measures of democracy (including Polity and UDS) demonstrate that participatory constitution-building improves levels of democracy, but we also still need to know which components of democracies are actually improved. Along the same lines, it would probably be useful to further disaggregate participation as a causal variable by separately measuring inclusion, or the breadth of participation by stage. Such an approach might help resolve the paradox presented by Horowitz, who argues that Indonesia's constitution-making process was “representative and inclusive, but it was certainly not participatory” (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013, 12).

Contemporary constitution-making has differed in important ways from earlier eras, when these were considered to be the result of extraordinary crises. Over the last several decades, the frequency of new constitutions has increased slightly. Constitutional changes during the Third Wave have had a mixed impact on democracy, and our analysis offers a compelling explanation for this ambiguity by demonstrating the systematic benefits of early and direct citizen involvement, thus offering a compelling rationale for the claim that participation creates the kinds of institutions and societal oversight that improves democracy. New knowledge of the relationship between constitution-making and democracy will help scholars, analysts, and policymakers focus attention more on process, as well as their traditional emphasis on substantive content, and to reconsider those elements of the process most conducive to realizing democrats’ still elusive aspirations.

APPENDIXES FOR ADDITIONAL STATISTICAL ANALYSES AS CHECKS ON ROBUSTNESS OF MODELS

TABLE 5. Heckman Selection Model

TABLE 6. Participation Hypothesis and Level of Democracy Stratified by Regime Type

TABLE 7. Stage 1 of the 2SLS Models

TABLE 8. Stage 2 of the 2SLS Models

TABLE 9. Correlation among the Three Stage Variables

TABLE 10. Test of Collinearity

TABLE 11. Large Sample Model

TABLE 12. Model using Bootstrapped Standard Errors: Bootstrap Replications (1000) Seed (123)

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.