1 Introduction

Let

![]() $(M,g)$

be a smooth, compact Riemannian manifold with no boundary, unit mass, and let

$(M,g)$

be a smooth, compact Riemannian manifold with no boundary, unit mass, and let

![]() $\Delta _g$

denote the Laplace–Beltrami operator. Also, let

$\Delta _g$

denote the Laplace–Beltrami operator. Also, let

![]() $\{ \phi _{\lambda } \}$

be an orthonormal basis of eigenfunctions of

$\{ \phi _{\lambda } \}$

be an orthonormal basis of eigenfunctions of

![]() $\Delta _g$

with eigenvalues

$\Delta _g$

with eigenvalues

![]() $0 \le \lambda _1 \le \lambda _2 \le \ldots $

. For an observable

$0 \le \lambda _1 \le \lambda _2 \le \ldots $

. For an observable

![]() $f \in C^{\infty }({\mathbb S}^* M)$

, where

$f \in C^{\infty }({\mathbb S}^* M)$

, where

![]() ${\mathbb S}^* M$

denotes the unit cotangent bundle of M, let

${\mathbb S}^* M$

denotes the unit cotangent bundle of M, let

![]() $\operatorname {Op}(f)$

denote its quantization, defined as a pseudo-differential operator (cf. [Reference Dimassi and Sjöstrand9] for details.) A central problem in quantum chaos (cf. [Reference Zelditch52, Problem 3.1]) is to understand the set of possible quantum limits (sometimes called semiclassical measures) describing the distribution of mass of the eigenfunctions

$\operatorname {Op}(f)$

denote its quantization, defined as a pseudo-differential operator (cf. [Reference Dimassi and Sjöstrand9] for details.) A central problem in quantum chaos (cf. [Reference Zelditch52, Problem 3.1]) is to understand the set of possible quantum limits (sometimes called semiclassical measures) describing the distribution of mass of the eigenfunctions

![]() $\{ \phi _{\lambda } \}$

within

$\{ \phi _{\lambda } \}$

within

![]() ${\mathbb S}^* M$

, in the limit as the eigenvalue

${\mathbb S}^* M$

, in the limit as the eigenvalue

![]() $\lambda $

tends to infinity. A cornerstone result in this direction is the quantum ergodicity theorem of Shnirelman [Reference Šnirel'man45], Colin de Verdiére [Reference Colin de Verdière8] and Zelditch [Reference Zelditch51] which states that if the geodesic flow on M is ergodic there exists a density one subsequence of eigenfunctions

$\lambda $

tends to infinity. A cornerstone result in this direction is the quantum ergodicity theorem of Shnirelman [Reference Šnirel'man45], Colin de Verdiére [Reference Colin de Verdière8] and Zelditch [Reference Zelditch51] which states that if the geodesic flow on M is ergodic there exists a density one subsequence of eigenfunctions

![]() $\{ \phi _{\lambda _j}\}$

such that

$\{ \phi _{\lambda _j}\}$

such that

as

![]() $\lambda _j \rightarrow \infty $

, where

$\lambda _j \rightarrow \infty $

, where

![]() $d\mu _{L}$

is the normalized Liouville measure on

$d\mu _{L}$

is the normalized Liouville measure on

![]() ${\mathbb S}^* M$

. (Note that any quantum limit, by Egorov’s theorem, is invariant under the classical dynamics.)

${\mathbb S}^* M$

. (Note that any quantum limit, by Egorov’s theorem, is invariant under the classical dynamics.)

While the quantum ergodicity theorem implies that the mass of almost all eigenfunctions equidistributes in

![]() ${\mathbb S}^{*} M$

with respect to

${\mathbb S}^{*} M$

with respect to

![]() $d\mu _{L}$

, it does not rule out the existence of sparse subsequences along which the mass of the eigenfunctions localizes. Whether or not this happens crucially depends on the geometry of M, cf. Section 1.3.

$d\mu _{L}$

, it does not rule out the existence of sparse subsequences along which the mass of the eigenfunctions localizes. Whether or not this happens crucially depends on the geometry of M, cf. Section 1.3.

In this article, we study quantum limits of ‘point scatterers’ on

![]() $M=\mathbb T^2=\mathbb R^2/2\pi \mathbb Z^2$

. These are singular perturbations of the Laplacian on M and were used by Šeba [Reference Šeba40] in order to study the transition between integrability and chaos in quantum systems. The perturbation is quite weak and has essentially no effect on the classical dynamics, yet the quantum dynamics ‘feels’ the effect of the scatterer, and an analog of the quantum ergodicity theorem is known to hold [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär38, Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär27] (namely, equidistribution holds for a full density subset of the ‘new’ eigenfunctions), even though classical ergodicity does not hold.

$M=\mathbb T^2=\mathbb R^2/2\pi \mathbb Z^2$

. These are singular perturbations of the Laplacian on M and were used by Šeba [Reference Šeba40] in order to study the transition between integrability and chaos in quantum systems. The perturbation is quite weak and has essentially no effect on the classical dynamics, yet the quantum dynamics ‘feels’ the effect of the scatterer, and an analog of the quantum ergodicity theorem is known to hold [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär38, Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär27] (namely, equidistribution holds for a full density subset of the ‘new’ eigenfunctions), even though classical ergodicity does not hold.

The model also exhibits scarring along sparse subsequences of the new eigenfunctions [Reference Kurlberg and Rosenzweig25]. In particular, there exist quantum limits whose momentum push-forwards, which can be viewed as probability measures on the unit circle, are of the form

![]() $c \mu _{\text {sing}} + (1-c) \mu _{\text {uniform}}$

, for some

$c \mu _{\text {sing}} + (1-c) \mu _{\text {uniform}}$

, for some

![]() $c \in [1/2,1]$

. Here, both

$c \in [1/2,1]$

. Here, both

![]() $\mu _{\text {uniform}}$

and

$\mu _{\text {uniform}}$

and

![]() $\mu _{\text {sing}}$

are normalized to have mass one, and

$\mu _{\text {sing}}$

are normalized to have mass one, and

![]() $\mu _{\text {sing}}$

can be taken to be a sum of delta measures giving equal mass to the four points

$\mu _{\text {sing}}$

can be taken to be a sum of delta measures giving equal mass to the four points

![]() $\pm (1,0), \pm (0,1)$

. We note that

$\pm (1,0), \pm (0,1)$

. We note that

![]() $\mu _{\text {uniform}}$

is the push-forward of the Liouville measure and hence maximally delocalized, whereas

$\mu _{\text {uniform}}$

is the push-forward of the Liouville measure and hence maximally delocalized, whereas

![]() $\mu _{\text {sing}}$

is maximally localized since any quantum limits in this setting must be invariant under a certain eight fold symmetry (cf. equation (1.7)).

$\mu _{\text {sing}}$

is maximally localized since any quantum limits in this setting must be invariant under a certain eight fold symmetry (cf. equation (1.7)).

Stronger localization, that is, going beyond

![]() $c=1/2$

, is interesting given a number of ‘half delocalization’ results for quantum limits for some other (strongly chaotic) systems, namely quantized cat maps and geodesic flows on manifolds with constant negative curvature

$c=1/2$

, is interesting given a number of ‘half delocalization’ results for quantum limits for some other (strongly chaotic) systems, namely quantized cat maps and geodesic flows on manifolds with constant negative curvature

![]() $-1$

. In the former case, Faure and Nonnenmacher showed [Reference Faure and Nonnenmacher12] that if a quantum limit

$-1$

. In the former case, Faure and Nonnenmacher showed [Reference Faure and Nonnenmacher12] that if a quantum limit

![]() $\nu $

is decomposed as

$\nu $

is decomposed as

![]() $\nu = \nu _{\text {pp}} + \nu _{\text {Liouville}} + \nu _{sc}$

, with

$\nu = \nu _{\text {pp}} + \nu _{\text {Liouville}} + \nu _{sc}$

, with

![]() $\nu _{\text {pp}}$

denoting the pure point part and

$\nu _{\text {pp}}$

denoting the pure point part and

![]() $\nu _{sc}$

denoting the singular continuous part, then

$\nu _{sc}$

denoting the singular continuous part, then

![]() $\nu _{\text {Liouville}}({\mathbb T}^2) \ge \nu _{\text {pp}}({\mathbb T}^2)$

, and thus

$\nu _{\text {Liouville}}({\mathbb T}^2) \ge \nu _{\text {pp}}({\mathbb T}^2)$

, and thus

![]() $\nu _{\text {pp}}({\mathbb T}^2) \le 1/2$

. (We emphasize that

$\nu _{\text {pp}}({\mathbb T}^2) \le 1/2$

. (We emphasize that

![]() ${\mathbb T}^{2}$

is the full phase space in this setting.) In the latter case, it was shown that the Kolmogorov-Sinai (KS) entropy with respect to any measure arising as a quantum limit is at least

${\mathbb T}^{2}$

is the full phase space in this setting.) In the latter case, it was shown that the Kolmogorov-Sinai (KS) entropy with respect to any measure arising as a quantum limit is at least

![]() $1/2$

. We remark that for arithmetic point scatterers, the KS entropy is zero with respect to any flow invariant probability measure, in particular for any measure arising as a quantum limit.

$1/2$

. We remark that for arithmetic point scatterers, the KS entropy is zero with respect to any flow invariant probability measure, in particular for any measure arising as a quantum limit.

The aim of this paper is to exhibit essentially maximal localization for a quantum ergodic system, namely arithmetic toral point scatterers. In particular, we construct quantum limits (in momentum) corresponding to

![]() $c=1$

in the above decomposition; other interesting examples include singular continuous measures with support, say, on Cantor sets. This can be viewed as a step towards a ‘measure classification’ for quantum limits of quantum ergodic systems.

$c=1$

in the above decomposition; other interesting examples include singular continuous measures with support, say, on Cantor sets. This can be viewed as a step towards a ‘measure classification’ for quantum limits of quantum ergodic systems.

1.1 Description of the model

Let us now describe the basic properties of the point scatterer. This is discussed in further detail in [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär38, Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär39, Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär27, Reference Kurlberg and Rosenzweig25, Reference Šeba40, Reference Shigehara42]. To describe the quantum system associated with the point scatterer, consider

![]() $ -\Delta |_{D_{x_0}}, $

where

$ -\Delta |_{D_{x_0}}, $

where

By von Neumann’s theory of self-adjoint extensions (see Appendix A of [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär38]) there exists a one parameter family of self-adjoint extension of

![]() $-\Delta |_{D_{x_0}}$

parameterized by a phase

$-\Delta |_{D_{x_0}}$

parameterized by a phase

![]() $\varphi \in (- \pi , \pi ]$

. Moreover, for

$\varphi \in (- \pi , \pi ]$

. Moreover, for

![]() $\varphi \neq \pi $

the eigenvalues of these operators may be divided into two categories. The old eigenvalues which are eigenvalues of

$\varphi \neq \pi $

the eigenvalues of these operators may be divided into two categories. The old eigenvalues which are eigenvalues of

![]() $-\Delta $

, with multiplicity decreased by one, along with new eigenvalues which are solutions to the spectral equation

$-\Delta $

, with multiplicity decreased by one, along with new eigenvalues which are solutions to the spectral equation

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{m \ge 1} r(m) \left( \frac{1}{m-\lambda}-\frac{m}{m^2+1} \right)=\tan(\varphi/2)\sum_{m\ge 1} \frac{r(m)}{m^2+1}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{m \ge 1} r(m) \left( \frac{1}{m-\lambda}-\frac{m}{m^2+1} \right)=\tan(\varphi/2)\sum_{m\ge 1} \frac{r(m)}{m^2+1}, \end{align} $$

where

We will refer to the case when

![]() $\varphi $

is fixed as

$\varphi $

is fixed as

![]() $\lambda \rightarrow \infty $

the weak coupling quantization. In this regime work of Shigehara [Reference Shigehara42] suggests that the level spacing of the eigenvalues should have Poisson spacing statistics, and this is supported by work of Rudnick and Ueberschär [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär39] along with Freiberg, Kurlberg and Rosenzweig [Reference Freiberg, Kurlberg and Rosenzweig14]. In the hope of exhibiting wave chaos, Shigehara proposes the following strong coupling quantization

$\lambda \rightarrow \infty $

the weak coupling quantization. In this regime work of Shigehara [Reference Shigehara42] suggests that the level spacing of the eigenvalues should have Poisson spacing statistics, and this is supported by work of Rudnick and Ueberschär [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär39] along with Freiberg, Kurlberg and Rosenzweig [Reference Freiberg, Kurlberg and Rosenzweig14]. In the hope of exhibiting wave chaos, Shigehara proposes the following strong coupling quantization

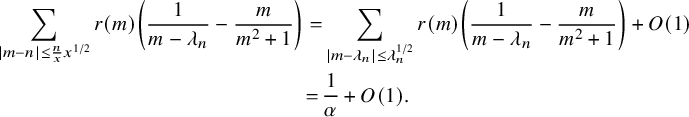

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{|m-\lambda|\le \lambda^{1/2}} r(m) \left( \frac{1}{m-\lambda}-\frac{m}{m^2+1} \right)=\frac{1}{\alpha}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{|m-\lambda|\le \lambda^{1/2}} r(m) \left( \frac{1}{m-\lambda}-\frac{m}{m^2+1} \right)=\frac{1}{\alpha}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\alpha \in \mathbb R$

is called the physical coupling constant and reflects the strength of the scatterer. The strong coupling quantization restricts the spectral equation to the physically relevant energy levels. Notably, this forces a renormalization of equation (1.1)

$\alpha \in \mathbb R$

is called the physical coupling constant and reflects the strength of the scatterer. The strong coupling quantization restricts the spectral equation to the physically relevant energy levels. Notably, this forces a renormalization of equation (1.1)

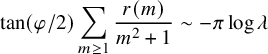

$$\begin{align*}\tan(\varphi/2)\sum_{m \ge 1} \frac{r(m)}{m^2+1} \sim -\pi \log \lambda \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\tan(\varphi/2)\sum_{m \ge 1} \frac{r(m)}{m^2+1} \sim -\pi \log \lambda \end{align*}$$

so that

![]() $\varphi $

depends on

$\varphi $

depends on

![]() $\lambda $

in this case (see [Reference Ueberschär48] equation (3.14)). We note that the weak coupling quantization corresponds to a fixed self-adjoint extension, whereas the strong coupling quantization can be viewed as an energy-dependent, albeit very slowly varying, family of self-adjoint extensions.

$\lambda $

in this case (see [Reference Ueberschär48] equation (3.14)). We note that the weak coupling quantization corresponds to a fixed self-adjoint extension, whereas the strong coupling quantization can be viewed as an energy-dependent, albeit very slowly varying, family of self-adjoint extensions.

From the spectral equation, it follows that new eigenvalues interlace with integers which are representable as the sum of two integer squares. We denote these eigenvalues as follows:

and write

![]() $\Lambda _{new}$

for the set of all such eigenvalues. Also, given

$\Lambda _{new}$

for the set of all such eigenvalues. Also, given

![]() $n=a^2+b^2$

, let

$n=a^2+b^2$

, let

![]() $n^+$

denote the smallest integer greater than n which is also a sum of two squares. Let

$n^+$

denote the smallest integer greater than n which is also a sum of two squares. Let

denote the distance between

![]() $\lambda _n$

and the nearest old eigenvalue n to the left. In addition, given

$\lambda _n$

and the nearest old eigenvalue n to the left. In addition, given

![]() $\lambda \in \Lambda _{new}$

the associated Green’s function is given by

$\lambda \in \Lambda _{new}$

the associated Green’s function is given by

$$ \begin{align} G_{\lambda}(x)=-\frac{1}{4 \pi^2} \sum_{ \xi \in \mathbb Z^2} \frac{ \exp(-i \xi \cdot x_0)}{|\xi|^2- \lambda} e^{i \xi \cdot x}, \qquad g_{\lambda}(x)=\frac{1}{\lVert G_{\lambda} \rVert_2} G_{\lambda}(x) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} G_{\lambda}(x)=-\frac{1}{4 \pi^2} \sum_{ \xi \in \mathbb Z^2} \frac{ \exp(-i \xi \cdot x_0)}{|\xi|^2- \lambda} e^{i \xi \cdot x}, \qquad g_{\lambda}(x)=\frac{1}{\lVert G_{\lambda} \rVert_2} G_{\lambda}(x) \end{align} $$

(see equation (5.2) of [Reference Rudnick and Ueberschär38]). Also, note that the new eigenvalues interlace between the old eigenvalues; hence,

![]() $G_{\lambda }$

is well defined for

$G_{\lambda }$

is well defined for

![]() $\lambda \in \Lambda _{new}$

. Since the torus is homogeneous, we may without loss of generality assume that

$\lambda \in \Lambda _{new}$

. Since the torus is homogeneous, we may without loss of generality assume that

![]() $x_{0}=0$

. Our main focus will be the behavior of the matrix coefficients

$x_{0}=0$

. Our main focus will be the behavior of the matrix coefficients

![]() $ \{\langle \operatorname {Op}(f) g_{\lambda }, g_{\lambda } \rangle \}_{\lambda \in \Lambda _{new}}$

as f ranges over the set of pure momentum observables (i.e.,

$ \{\langle \operatorname {Op}(f) g_{\lambda }, g_{\lambda } \rangle \}_{\lambda \in \Lambda _{new}}$

as f ranges over the set of pure momentum observables (i.e.,

![]() $f \in C^{\infty } (S^1) \subset C^{\infty }({\mathbb S}^{*}(\mathbb T^2))$

; for such f the matrix coefficients are explicitly given by (cf. equation (5.3))

$f \in C^{\infty } (S^1) \subset C^{\infty }({\mathbb S}^{*}(\mathbb T^2))$

; for such f the matrix coefficients are explicitly given by (cf. equation (5.3))

$$ \begin{align} \langle \operatorname{Op}(f) g_{\lambda}, g_{\lambda} \rangle = \frac{1}{\sum_{n \ge 0} \frac{r(n)}{(n-\lambda)^2}} \left( \frac{f(1)}{\lambda^{2}} + \sum_{ n> 0 }\frac{1}{(n-\lambda)^2} \sum_{ a^2+b^2=n} f\left(\frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|} \right) \right). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \langle \operatorname{Op}(f) g_{\lambda}, g_{\lambda} \rangle = \frac{1}{\sum_{n \ge 0} \frac{r(n)}{(n-\lambda)^2}} \left( \frac{f(1)}{\lambda^{2}} + \sum_{ n> 0 }\frac{1}{(n-\lambda)^2} \sum_{ a^2+b^2=n} f\left(\frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|} \right) \right). \end{align} $$

1.2 Results

Our first main result shows that along a zero density, yet relatively large, subsequence of new eigenvalues

![]() $\{\lambda _j\}$

the mass of

$\{\lambda _j\}$

the mass of

![]() $g_{\lambda _j}$

, in momentum space, localizes on measures arising from

$g_{\lambda _j}$

, in momentum space, localizes on measures arising from

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

-lattice points on circles (after projecting them to the unit circle). To describe these measures in more detail, consider an integer

${\mathbb Z}^2$

-lattice points on circles (after projecting them to the unit circle). To describe these measures in more detail, consider an integer

![]() $n=a^2+b^2$

, with

$n=a^2+b^2$

, with

![]() $a,b\in {\mathbb Z}$

, and the following probability measure on the unit circle

$a,b\in {\mathbb Z}$

, and the following probability measure on the unit circle

![]() $S^1 \subset {\mathbb C}$

$S^1 \subset {\mathbb C}$

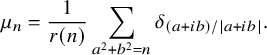

$$\begin{align*}\mu_n =\frac{1}{r(n)} \sum_{a^2+b^2=n} \delta_{(a+ib)/|a+ib|}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\mu_n =\frac{1}{r(n)} \sum_{a^2+b^2=n} \delta_{(a+ib)/|a+ib|}. \end{align*}$$

We remark that

![]() $\mu _n$

can be viewed as the matrix coefficient of the ‘flat’ (old) Laplace eigenfunction

$\mu _n$

can be viewed as the matrix coefficient of the ‘flat’ (old) Laplace eigenfunction

![]() $ \psi _n(x) = \frac {1}{2 \pi \sqrt {r(n)}} \sum _{\xi \in {\mathbb Z}^2 : |\xi |^{2} = n} e^{ -i \xi \cdot x }, $

in the sense that, for f a pure momentum observable, we have

$ \psi _n(x) = \frac {1}{2 \pi \sqrt {r(n)}} \sum _{\xi \in {\mathbb Z}^2 : |\xi |^{2} = n} e^{ -i \xi \cdot x }, $

in the sense that, for f a pure momentum observable, we have

$$ \begin{align} \langle \operatorname{Op}(f) \psi_{n}, \psi_{n}\rangle = \sum_{ a^2+b^2=n} f\left(\frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|} \right) = \mu_n(f).\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \langle \operatorname{Op}(f) \psi_{n}, \psi_{n}\rangle = \sum_{ a^2+b^2=n} f\left(\frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|} \right) = \mu_n(f).\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

Following Kurlberg and Wigman [Reference Kurlberg and Wigman29], we call a measure

![]() $\mu _{\infty }$

attainable if it is a weak limit point of the set

$\mu _{\infty }$

attainable if it is a weak limit point of the set

![]() $\{ \mu _n \}_{n=a^2+b^2}$

. Any such measure is invariant under rotation by

$\{ \mu _n \}_{n=a^2+b^2}$

. Any such measure is invariant under rotation by

![]() $\pi /2$

, as well as under reflection in the x-axis; for convenience let

$\pi /2$

, as well as under reflection in the x-axis; for convenience let

$$ \begin{align} \text{Sym}_{8} := \left\{ \left\langle \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \right\rangle \right\} \subset GL_{2}({\mathbb Z})\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \text{Sym}_{8} := \left\{ \left\langle \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \right\rangle \right\} \subset GL_{2}({\mathbb Z})\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

denote the group generated by these transformations.

Theorem 1.1. Let

![]() $m_0=a^2+b^2 \in \mathbb N$

be odd.Footnote

1

In each of the weak and strong coupling quantizations, there exists a subset of eigenvalues

$m_0=a^2+b^2 \in \mathbb N$

be odd.Footnote

1

In each of the weak and strong coupling quantizations, there exists a subset of eigenvalues

![]() ${\mathcal E}_{m_0} \subset \Lambda _{new}$

with

${\mathcal E}_{m_0} \subset \Lambda _{new}$

with

$$\begin{align*}\frac{ \# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0} \}}{\# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in \Lambda_{\text{new}} \} } \gg \frac{1 }{(\log X)^{1+o(1)}}\\[-9pt] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{ \# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0} \}}{\# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in \Lambda_{\text{new}} \} } \gg \frac{1 }{(\log X)^{1+o(1)}}\\[-9pt] \end{align*}$$

such that for any pure momentum observable

![]() $f \in C^{\infty } (S^1) \subset C^{\infty }(\mathbb S^{*}(\mathbb T^2))$

$f \in C^{\infty } (S^1) \subset C^{\infty }(\mathbb S^{*}(\mathbb T^2))$

$$\begin{align*}\langle \operatorname{Op}(f) g_{\lambda}, g_{\lambda} \rangle \xrightarrow{ \substack{\lambda \rightarrow \infty \\ \lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0}}} \frac{1}{r(m_0)} \sum_{a^2+b^2=m_0} f\left(\frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|} \right).\\[-9pt] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\langle \operatorname{Op}(f) g_{\lambda}, g_{\lambda} \rangle \xrightarrow{ \substack{\lambda \rightarrow \infty \\ \lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0}}} \frac{1}{r(m_0)} \sum_{a^2+b^2=m_0} f\left(\frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|} \right).\\[-9pt] \end{align*}$$

The key idea of the proof is to show that some new eigenvalues

![]() $\lambda $

lie very close to certain old eigenvalues n, and this implies that

$\lambda $

lie very close to certain old eigenvalues n, and this implies that

![]() $g_{\lambda }$

is very well approximated by the flat eigenfunction

$g_{\lambda }$

is very well approximated by the flat eigenfunction

![]() $\psi _{n}$

(cf. equations (1.5) and (1.6)), and consequently, in momentum space, the mass of

$\psi _{n}$

(cf. equations (1.5) and (1.6)), and consequently, in momentum space, the mass of

![]() $g_{\lambda }$

completely localizes on the measure

$g_{\lambda }$

completely localizes on the measure

![]() $ \mu _{m_0}$

. Further, for any attainable measure

$ \mu _{m_0}$

. Further, for any attainable measure

![]() $\mu _{\infty }$

there exists

$\mu _{\infty }$

there exists

![]() $\{m_{0, \ell } \}_{\ell }$

such that

$\{m_{0, \ell } \}_{\ell }$

such that

![]() $\mu _{m_{0},\ell }$

weakly converges to

$\mu _{m_{0},\ell }$

weakly converges to

![]() $\mu _{\infty }$

, and this implies the following corollary.

$\mu _{\infty }$

, and this implies the following corollary.

Corollary 1.1. Let

![]() $\mu _{\infty }$

be an attainable measure. Then there exists

$\mu _{\infty }$

be an attainable measure. Then there exists

![]() $\{\lambda _j\}_{j} \subset \Lambda _{\text {new}}$

such that for any pure momentum observable

$\{\lambda _j\}_{j} \subset \Lambda _{\text {new}}$

such that for any pure momentum observable

![]() $f \in C^{\infty }(S^1) $

$f \in C^{\infty }(S^1) $

We note that the set of attainable measures is much smaller than the set of probability measures on

![]() $S^{1}$

that are

$S^{1}$

that are

![]() $\text {Sym}_{8}$

-invariant, in particular the set of attainable measures is not convex (cf. [Reference Kurlberg and Wigman29, Section 3.2].) In our next result, we show that in the strong coupling quantization there is a subsequence of new eigenvalues along which the entire mass of

$\text {Sym}_{8}$

-invariant, in particular the set of attainable measures is not convex (cf. [Reference Kurlberg and Wigman29, Section 3.2].) In our next result, we show that in the strong coupling quantization there is a subsequence of new eigenvalues along which the entire mass of

![]() $g_{\lambda }$

localizes on a certain convex combination of two measures arising from lattice points on the circle. In particular, the set of quantum limits, in momentum space, is strictly richer than the set of attainable measures.

$g_{\lambda }$

localizes on a certain convex combination of two measures arising from lattice points on the circle. In particular, the set of quantum limits, in momentum space, is strictly richer than the set of attainable measures.

Theorem 1.2. Let

![]() $m_0,m_1$

be odd integers which are each representable as a sum of two squares. Then in the strong coupling quantization there exists a subsequence of eigenvalues

$m_0,m_1$

be odd integers which are each representable as a sum of two squares. Then in the strong coupling quantization there exists a subsequence of eigenvalues

![]() $ {\mathcal E}_{m_0,m_1} \subset \Lambda _{\text {new}}$

such that for each

$ {\mathcal E}_{m_0,m_1} \subset \Lambda _{\text {new}}$

such that for each

![]() $\lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0,m_1}$

there is an integer

$\lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0,m_1}$

there is an integer

![]() $\ell _{\lambda }$

with

$\ell _{\lambda }$

with

![]() $r(\ell _{\lambda }) \neq 0$

and

$r(\ell _{\lambda }) \neq 0$

and

![]() $r(\ell _{\lambda }) \ll 1$

such that for pure momentum observables

$r(\ell _{\lambda }) \ll 1$

such that for pure momentum observables

![]() $f \in C^{\infty }(S^1)$

$f \in C^{\infty }(S^1)$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \langle \operatorname{Op}(f) g_{\lambda}, g_{\lambda} \rangle =\,& c_{\lambda} \cdot \frac{1}{r(m_0)} \sum_{a^2+b^2=m_0} f\left( \frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|}\right) \\ & + (1-c_{\lambda}) \cdot \frac{1}{r(m_1\ell_{\lambda})} \sum_{a^2+b^2=m_1 \ell_{\lambda}} f\left( \frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|}\right)+O\left(\frac{1}{(\log \log \lambda)^{1/11}} \right), \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \langle \operatorname{Op}(f) g_{\lambda}, g_{\lambda} \rangle =\,& c_{\lambda} \cdot \frac{1}{r(m_0)} \sum_{a^2+b^2=m_0} f\left( \frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|}\right) \\ & + (1-c_{\lambda}) \cdot \frac{1}{r(m_1\ell_{\lambda})} \sum_{a^2+b^2=m_1 \ell_{\lambda}} f\left( \frac{a+ib}{|a+ib|}\right)+O\left(\frac{1}{(\log \log \lambda)^{1/11}} \right), \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

where

Additionally,

$$\begin{align*}\frac{ \# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0,m_1} \}}{\# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in \Lambda_{\text{new}} \} } \gg \frac{1 }{(\log X)^{2+o(1)}}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{ \# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in {\mathcal E}_{m_0,m_1} \}}{\# \{ \lambda \le X : \lambda \in \Lambda_{\text{new}} \} } \gg \frac{1 }{(\log X)^{2+o(1)}}. \end{align*}$$

Note that, since

![]() $\sum _{p|\ell _{\lambda }} 1 \ll 1$

, the measure

$\sum _{p|\ell _{\lambda }} 1 \ll 1$

, the measure

![]() $\mu _{m_{1} \ell _{\lambda }}$

can be viewed as a fairly small perturbation of

$\mu _{m_{1} \ell _{\lambda }}$

can be viewed as a fairly small perturbation of

![]() $\mu _{m_{1}}$

.

$\mu _{m_{1}}$

.

Remark 1. By removing a further ‘thin’ set of eigenvalues (with spectral counting function of size

![]() $O(x^{1-\epsilon })$

for

$O(x^{1-\epsilon })$

for

![]() $\epsilon>0$

, we can construct quantum limits that are flat in position (for details, cf. [Reference Kurlberg and Rosenzweig25, Remark 4]), in addition to the momentum push-forward properties given in Theorems 1.1 and 1.2. In particular, taking say

$\epsilon>0$

, we can construct quantum limits that are flat in position (for details, cf. [Reference Kurlberg and Rosenzweig25, Remark 4]), in addition to the momentum push-forward properties given in Theorems 1.1 and 1.2. In particular, taking say

![]() $m_{0}=9$

in Theorem 1.1 and noting that

$m_{0}=9$

in Theorem 1.1 and noting that

![]() $|z|^{2} = 9$

for

$|z|^{2} = 9$

for

![]() $z \in {\mathbb Z}[i]$

has the four solutions

$z \in {\mathbb Z}[i]$

has the four solutions

![]() $\pm 3, \pm 3i$

, this then yields quantum limits that are completely localized on the superposition of two Lagrangian states – essentially two plane waves, one in the horizontal and one in the vertical direction. This phenomenon is sometimes called superscarring (cf. [Reference Bogomolny and Schmit6, Reference Kurlberg and Rosenzweig25]).

$\pm 3, \pm 3i$

, this then yields quantum limits that are completely localized on the superposition of two Lagrangian states – essentially two plane waves, one in the horizontal and one in the vertical direction. This phenomenon is sometimes called superscarring (cf. [Reference Bogomolny and Schmit6, Reference Kurlberg and Rosenzweig25]).

Further, assuming a plausible conjecture on the distribution of the prime numbers, we show that given

![]() $m_0,m_1$

as in Theorem 1.2 the quantum limit of

$m_0,m_1$

as in Theorem 1.2 the quantum limit of

![]() $\langle \operatorname {Op}(f) g_{\lambda }, g_{\lambda } \rangle $

can be made to be any given convex combination of

$\langle \operatorname {Op}(f) g_{\lambda }, g_{\lambda } \rangle $

can be made to be any given convex combination of

![]() $\mu _{m_0}$

and

$\mu _{m_0}$

and

![]() $\mu _{m_1}$

. The conjecture on the distribution of primes concerns obtaining a lower bound on the number solutions

$\mu _{m_1}$

. The conjecture on the distribution of primes concerns obtaining a lower bound on the number solutions

![]() $(u,v)$

in almost primes to the Diophantine equation

$(u,v)$

in almost primes to the Diophantine equation

where

![]() $v=p_1p_2$

,

$v=p_1p_2$

,

![]() $u=p_3$

with

$u=p_3$

with

![]() $p_j$

a prime satisfying

$p_j$

a prime satisfying

![]() $p_j=a_j^2+b_j^2$

and

$p_j=a_j^2+b_j^2$

and

![]() $b_j=o(a_j)$

for

$b_j=o(a_j)$

for

![]() $j=1,2,3$

. The precise formulation of this conjecture, which we call Hypothesis 1, is given in Section 5.5.

$j=1,2,3$

. The precise formulation of this conjecture, which we call Hypothesis 1, is given in Section 5.5.

Theorem 1.3. Assume Hypothesis 1. Let

![]() $\mu _{\infty _0}, \mu _{\infty _1}$

be attainable measures and

$\mu _{\infty _0}, \mu _{\infty _1}$

be attainable measures and

![]() $0\le c \le 1$

. Then in the strong coupling quantization there exists

$0\le c \le 1$

. Then in the strong coupling quantization there exists

![]() $\{ \lambda _j \}_{j} \subset \Lambda _{new}$

such that for any

$\{ \lambda _j \}_{j} \subset \Lambda _{new}$

such that for any

![]() $f \in C^{\infty }(S^1)$

$f \in C^{\infty }(S^1)$

Further, assuming a variation of the prime k-tuple conjecture that also allows for prescribing Gaussian angles, we can show (cf. Appendix C) that all

![]() $\text {Sym}_{8}$

-invariant probability measures on

$\text {Sym}_{8}$

-invariant probability measures on

![]() $S^{1}$

arise as quantum limits in momentum space.

$S^{1}$

arise as quantum limits in momentum space.

1.3 Discussion

For integrable systems it is often straightforward to construct nonuniform quantum limits, for example, ‘whispering gallery modes’ for the geodesic flow in the unit ball, and for linear flows on

![]() ${\mathbb T}^2$

, Lagrangian states with maximal localization (i.e., a single plane wave) are easily constructed. We note that strong localization in position for quantum limits on

${\mathbb T}^2$

, Lagrangian states with maximal localization (i.e., a single plane wave) are easily constructed. We note that strong localization in position for quantum limits on

![]() ${\mathbb T}^2$

was ruled out by Jakobson [Reference Jakobson20] – in position, any quantum limit is given by trigonometric polynomials whose frequencies lie on at most two circles (hence absolutely continuous with respect to Lebesgue measure.) Further, for the sphere, Jakobson and Zelditch in fact obtained a full classification – any flow invariant measure on

${\mathbb T}^2$

was ruled out by Jakobson [Reference Jakobson20] – in position, any quantum limit is given by trigonometric polynomials whose frequencies lie on at most two circles (hence absolutely continuous with respect to Lebesgue measure.) Further, for the sphere, Jakobson and Zelditch in fact obtained a full classification – any flow invariant measure on

![]() $S^{*}(S^{2})$

is a quantum limit [Reference Jakobson and Zelditch21].

$S^{*}(S^{2})$

is a quantum limit [Reference Jakobson and Zelditch21].

The quantum ergodicity theorem holds in great generality as long as the key assumption of ergodic classical dynamics holds, but the existence of exceptional subsequence of nonuniform quantum limits (‘scarring’) is subtle. For classical systems given by the geodesic flow on compact negatively curved manifolds, the celebrated quantum unique ergodicity (QUE) conjecture [Reference Rudnick and Sarnak37] by Rudnick and Sarnak asserts that the only possible quantum limit is the Liouville measure. Known results for QUE include Lindenstrauss’ breakthrough [Reference Lindenstrauss30] for Hecke eigenfunctions on arithmetic modular surfaces, together with Soundararajan ruling out ‘escape of mass’ in the noncompact case [Reference Soundararajan46]. On the other hand, for a generic Bunimovich stadium (with strongly chaotic classical dynamics), Hassell [Reference Hassell and Hillairet16] has shown that there exists a subsequence of exceptional eigenstates where the mass localizes on sets of bouncing ball trajectories.

For quantized cat maps, again for Hecke eigenfunctions, QUE is known to hold [Reference Kurlberg and Rudnick26]. However, unlike for arithmetic modular surfaces, where Hecke desymmetrization is believed to be unnecessary, it is essential for quantum cat maps. Namely, Faure, Nonnenmacher and de Bièvre [Reference Faure, Nonnenmacher and De Bièvre13] constructed, in the presence of extreme spectral multiplicities and no Hecke desymmetrization, quantum limits of the form

![]() $\nu = \frac {1}{2} \nu _{\text {pp}} + \frac {1}{2} \nu _{\text {Liouville}}$

; in [Reference Faure and Nonnenmacher12], this was shown to be sharp in the sense that the Liouville component always carries at least as much mass as the pure point one. (We note that, on assuming very weak bounds on spectral multiplicities, Bourgain showed [Reference Bourgain7] that scarring does not occur.) For higher-dimensional analogs of quantum cat maps, Kelmer has for certain maps shown [Reference Kelmer23] ‘super scarring’, even after Hecke desymmetrization, on invariant rational isotropic subspaces. Further, these type of scars persist on adding certain perturbations that destroy the spectral multiplicities [Reference Kelmer24]. Other models where scarring is known to exist include toral point scatterers with irrational aspect ratios [Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär28, Reference Keating, Marklof and Winn22, Reference Berkolaiko, Keating and Winn3] and quantum star graphs [Reference Berkolaiko, Keating and Winn4], though neither model is quantum ergodic [Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär28, Reference Berkolaiko, Keating and Winn4].

$\nu = \frac {1}{2} \nu _{\text {pp}} + \frac {1}{2} \nu _{\text {Liouville}}$

; in [Reference Faure and Nonnenmacher12], this was shown to be sharp in the sense that the Liouville component always carries at least as much mass as the pure point one. (We note that, on assuming very weak bounds on spectral multiplicities, Bourgain showed [Reference Bourgain7] that scarring does not occur.) For higher-dimensional analogs of quantum cat maps, Kelmer has for certain maps shown [Reference Kelmer23] ‘super scarring’, even after Hecke desymmetrization, on invariant rational isotropic subspaces. Further, these type of scars persist on adding certain perturbations that destroy the spectral multiplicities [Reference Kelmer24]. Other models where scarring is known to exist include toral point scatterers with irrational aspect ratios [Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär28, Reference Keating, Marklof and Winn22, Reference Berkolaiko, Keating and Winn3] and quantum star graphs [Reference Berkolaiko, Keating and Winn4], though neither model is quantum ergodic [Reference Kurlberg and Ueberschär28, Reference Berkolaiko, Keating and Winn4].

Classifying the set of possible quantum limits, in particular for quantum ergodic settings, is an interesting question. Here, Anantharaman proved very strong results for geodesic flows on negatively curved manifolds [Reference Anantharaman1]: any quantum limit has positive KS entropy with respect to the dynamics of the geodesic flow. In particular, this rules out localization on a finite number of closed geodesics (for compact arithmetic surfaces this was already known due to Rudnick and Sarnak [Reference Rudnick and Sarnak37].) Moreover, in the case of constant negative curvature, Anantharaman and Nonnenmacher showed [Reference Anantharaman and Nonnenmacher2] that the KS-entropy is at least half of the maximum possible. The measure of maximum entropy is given by the Liouville measure, and thus ‘eigenfunctions are at least half delocalized’. Dyatlov and Jin [Reference Dyatlov and Jin10] consequently showed that any quantum limit must have full support in

![]() $S^{*}(M)$

, for compact hyperbolic surfaces M with constant negative curvature; together with Nonnenmacher this was recently strengthened [Reference Dyatlov, Jin and Nonnenmacher11] to the include the case of surfaces with variable negative curvature.

$S^{*}(M)$

, for compact hyperbolic surfaces M with constant negative curvature; together with Nonnenmacher this was recently strengthened [Reference Dyatlov, Jin and Nonnenmacher11] to the include the case of surfaces with variable negative curvature.

1.4 Outline of the proofs

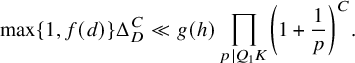

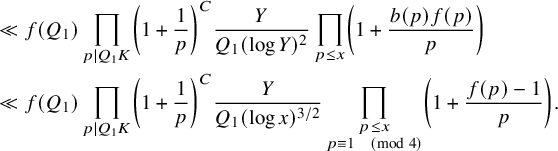

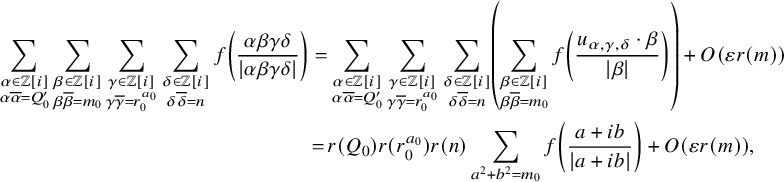

Our arguments use the multiplicative structure of the integers to create an imbalance in the spectral equation (1.2) along a zero density, yet relatively large subsequence of new eigenvalues. Through exploiting this imbalance, we control the location of the new eigenvalues in our subsequence and show that they lie close to integers which are sums of two squares (cf. Section 5.3, in particular equation (5.14) for the argument placing full mass at one nearby eigenspace and 5.4, in particular equation (5.18) for placing mass at two nearby eigenspaces.) This greatly amplifies the amount of mass of the corresponding eigenfunctions in momentum space which lies on the terms which correspond to these integers, so much so that the contribution of the remaining terms is negligible in comparison. Consequently, the mass completely localizes on a convex combination of two measures and moreover our construction allows us to completely control the first measure.

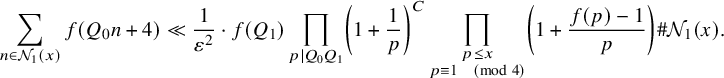

In Section 2, we use sieve methods to produce integers

![]() $n=p_1p_2$

, where

$n=p_1p_2$

, where

![]() $p_j$

,

$p_j$

,

![]() $j=1,2$

, is a prime with

$j=1,2$

, is a prime with

![]() $p_j=a^2+b^2=(a+ib)(a-ib)$

,

$p_j=a^2+b^2=(a+ib)(a-ib)$

,

![]() $0< b \le a$

, with

$0< b \le a$

, with

![]() $0\le \arctan (b/a) \le \varepsilon $

, where

$0\le \arctan (b/a) \le \varepsilon $

, where

![]() $\varepsilon $

is a small parameter, such that

$\varepsilon $

is a small parameter, such that

![]() $Q_0p_1p_2+4$

is also a sum of two squares,

$Q_0p_1p_2+4$

is also a sum of two squares,

![]() $Q_1|Q_0p_1p_2+4$

and

$Q_1|Q_0p_1p_2+4$

and

![]() $(Q_0p_1p_2+4)/Q_1$

has a bounded number of prime factors, where

$(Q_0p_1p_2+4)/Q_1$

has a bounded number of prime factors, where

![]() $Q_0,Q_1$

are large integers whose purpose we will describe later. In particular, we exploit special features of the half-dimensional sieve using an ingenious observation of Huxley and Iwaniec [Reference Huxley and Iwaniec18]. Further, in order to find suitable Gaussian primes in narrow sectors we use a classical result of Hecke together with nontrivial bounds on exponential sums over finite fields to control sums of integral lattice points in narrow sectors with norms lying in arithmetic progressions to large moduli.

$Q_0,Q_1$

are large integers whose purpose we will describe later. In particular, we exploit special features of the half-dimensional sieve using an ingenious observation of Huxley and Iwaniec [Reference Huxley and Iwaniec18]. Further, in order to find suitable Gaussian primes in narrow sectors we use a classical result of Hecke together with nontrivial bounds on exponential sums over finite fields to control sums of integral lattice points in narrow sectors with norms lying in arithmetic progressions to large moduli.

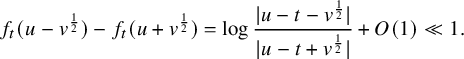

The subsequence of almost primes

![]() $\{n_{\ell }\}$

constructed as described above creates the imbalance in the spectral equation (1.2) by boosting the contribution of the terms

$\{n_{\ell }\}$

constructed as described above creates the imbalance in the spectral equation (1.2) by boosting the contribution of the terms

![]() $m=Q_0n_{\ell }, Q_0n_{\ell }+4$

, without perturbing the target measure(s). The next step in our argument is to show that this imbalance typically overwhelms the contribution of the remaining terms. To do this, we first show in Section 3 that for all new eigenvalues lying outside a small exceptional set the spectral equation (1.2) can be effectively truncated to integers m with essentially

$m=Q_0n_{\ell }, Q_0n_{\ell }+4$

, without perturbing the target measure(s). The next step in our argument is to show that this imbalance typically overwhelms the contribution of the remaining terms. To do this, we first show in Section 3 that for all new eigenvalues lying outside a small exceptional set the spectral equation (1.2) can be effectively truncated to integers m with essentially

![]() $|m-\lambda | \ll (\log \lambda )^{10}$

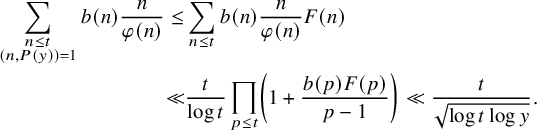

. This is done by controlling sums of

$|m-\lambda | \ll (\log \lambda )^{10}$

. This is done by controlling sums of

![]() $r(n)$

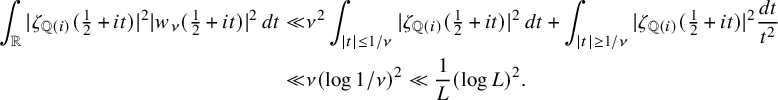

over short intervals and uses a second moment estimate of the Dedekind zeta-function

$r(n)$

over short intervals and uses a second moment estimate of the Dedekind zeta-function

![]() $\zeta _{\mathbb Q(i)}$

. In Section 4, we apply this result to new eigenvalues which lie between

$\zeta _{\mathbb Q(i)}$

. In Section 4, we apply this result to new eigenvalues which lie between

![]() $Q_0n_{\ell }$

and

$Q_0n_{\ell }$

and

![]() $Q_0n_{\ell }+4$

and show that for almost all such new eigenvalues the remaining terms in the spectral sum (i.e.,

$Q_0n_{\ell }+4$

and show that for almost all such new eigenvalues the remaining terms in the spectral sum (i.e.,

![]() $|m-\lambda | \ll (\log \lambda )^{10}, m \neq Q_0n_{\ell }, Q_0n_{\ell }+4)$

is relatively small, provided that we take

$|m-\lambda | \ll (\log \lambda )^{10}, m \neq Q_0n_{\ell }, Q_0n_{\ell }+4)$

is relatively small, provided that we take

![]() $Q_0,Q_1$

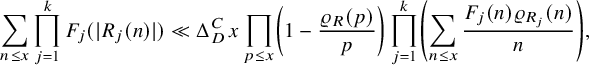

sufficiently large thereby boosting the contribution of the closest two terms. This is accomplished by using bounds for sums of multiplicative functions over polynomials due to Henriot [Reference Henriot17]. Crucially, we need good estimates for these sums in terms of the discriminant of the polynomials.

$Q_0,Q_1$

sufficiently large thereby boosting the contribution of the closest two terms. This is accomplished by using bounds for sums of multiplicative functions over polynomials due to Henriot [Reference Henriot17]. Crucially, we need good estimates for these sums in terms of the discriminant of the polynomials.

Finally, to get complete control on the first measure in Theorem 1.2 we choose

![]() $Q_0$

so that it is the product of a given fixed integer

$Q_0$

so that it is the product of a given fixed integer

![]() $m_0$

and large primes

$m_0$

and large primes

![]() $p_{k}=a^2+b^2$

with

$p_{k}=a^2+b^2$

with

![]() $0 \le \arctan (b_k/a_k) \le p_k^{-1/10}$

so that the probability measure on

$0 \le \arctan (b_k/a_k) \le p_k^{-1/10}$

so that the probability measure on

![]() $S^1$

associated with

$S^1$

associated with

![]() $Q_0n_{\ell }$

weakly converges to the measure associated with

$Q_0n_{\ell }$

weakly converges to the measure associated with

![]() $m_0$

as

$m_0$

as

![]() $\ell \rightarrow \infty $

. This last construction uses work of Ricci [Reference Ricci35] on Gaussian primes in narrow sectors.

$\ell \rightarrow \infty $

. This last construction uses work of Ricci [Reference Ricci35] on Gaussian primes in narrow sectors.

1.5 Notation

We write

![]() $f(x) \ll g(x)$

provided that

$f(x) \ll g(x)$

provided that

![]() $f(x)=O(g(x))$

. Additionally, if for all x under consideration

$f(x)=O(g(x))$

. Additionally, if for all x under consideration

![]() $|f(x)| \ge c g(x)$

we write

$|f(x)| \ge c g(x)$

we write

![]() $f(x) \gg g(x)$

. If we have both

$f(x) \gg g(x)$

. If we have both

![]() $f(x) \ll g(x)$

and

$f(x) \ll g(x)$

and

![]() $f(x) \gg g(x)$

, we write

$f(x) \gg g(x)$

, we write

![]() $f(x) \asymp g(x)$

. For some additional notation related to sieves, see Section 2.1.1.

$f(x) \asymp g(x)$

. For some additional notation related to sieves, see Section 2.1.1.

2 Sieve estimates

Let

![]() $B_0$

be a sufficiently large integer, define

$B_0$

be a sufficiently large integer, define

![]() $\varepsilon = (\log \log x)^{-1/11}$

, and let

$\varepsilon = (\log \log x)^{-1/11}$

, and let

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon,x}=\,&\{ p \ge (\log x)^{B_0} : p=a^2+b^2 \, \text{ and } \, 0 < \arctan(b/a) \le \varepsilon \}, \\ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon,x}'=\,&\{ p \in {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon} : p \le x^{1/9}\}. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon,x}=\,&\{ p \ge (\log x)^{B_0} : p=a^2+b^2 \, \text{ and } \, 0 < \arctan(b/a) \le \varepsilon \}, \\ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon,x}'=\,&\{ p \in {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon} : p \le x^{1/9}\}. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

For brevity, we will write

![]() ${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon }$

and

${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon }$

and

![]() ${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon }'$

for

${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon }'$

for

![]() ${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon ,x}$

and

${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon ,x}$

and

![]() ${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon ,x}'$

, respectively. Also, given

${\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon ,x}'$

, respectively. Also, given

![]() $f,g : \mathbb N \rightarrow \mathbb C$

we define the Dirichlet convolution of f and g by

$f,g : \mathbb N \rightarrow \mathbb C$

we define the Dirichlet convolution of f and g by

Also, let

![]() $Q_0,Q_1 \le (\log x)^{1/10}$

be odd coprime integers whose prime factors are all

$Q_0,Q_1 \le (\log x)^{1/10}$

be odd coprime integers whose prime factors are all

![]() $\equiv 1\ \pmod 4$

. Moreover, we assume that

$\equiv 1\ \pmod 4$

. Moreover, we assume that

![]() $Q_0=f_0^2 e_0 r_0^{a_0}, Q_1=f_1^2e_1 r_1^{a_1}$

, where

$Q_0=f_0^2 e_0 r_0^{a_0}, Q_1=f_1^2e_1 r_1^{a_1}$

, where

![]() $e_0,e_1$

are square-free,

$e_0,e_1$

are square-free,

![]() $f_0,f_1 \ll 1$

and

$f_0,f_1 \ll 1$

and

![]() $r_0,r_1$

are primes congruent to

$r_0,r_1$

are primes congruent to

![]() $1\ \pmod 4$

. Throughout, the arithmetic function

$1\ \pmod 4$

. Throughout, the arithmetic function

![]() $b(n)$

is the indicator function of the set of integers which are representable as a sum of two squares. Also, for

$b(n)$

is the indicator function of the set of integers which are representable as a sum of two squares. Also, for

![]() ${\mathcal S} \subset \mathbb N$

we define

${\mathcal S} \subset \mathbb N$

we define

$$\begin{align*}1_{ {\mathcal S}}(n)=\begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } n \in {\mathcal S}, \\ 0 & \text{ otherwise,} \end{cases} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}1_{ {\mathcal S}}(n)=\begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } n \in {\mathcal S}, \\ 0 & \text{ otherwise,} \end{cases} \end{align*}$$

and let

![]() $\varphi (n)=\#\{ m < n : (m,n)=1\}$

.

$\varphi (n)=\#\{ m < n : (m,n)=1\}$

.

Proposition 2.1. Let

![]() $\eta>0$

be sufficiently small, and let

$\eta>0$

be sufficiently small, and let

![]() $y=x^{\eta }$

. Suppose

$y=x^{\eta }$

. Suppose

![]() $y>Q_0Q_1$

. Then

$y>Q_0Q_1$

. Then

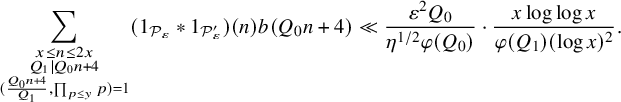

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1 | Q_0 n+4 \\ (\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1},\prod_{p \le y} p)=1}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) b(Q_0n+4) \asymp \frac{ \varepsilon^{2} Q_0}{ \eta^{1/2} \varphi(Q_0)} \cdot \frac{x \log \log x}{ \varphi(Q_1) (\log x)^2}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1 | Q_0 n+4 \\ (\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1},\prod_{p \le y} p)=1}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) b(Q_0n+4) \asymp \frac{ \varepsilon^{2} Q_0}{ \eta^{1/2} \varphi(Q_0)} \cdot \frac{x \log \log x}{ \varphi(Q_1) (\log x)^2}. \end{align*}$$

This proposition builds on a result of Friedlander and Iwaniec [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Ch. 4]. The main novelty here is that we capture almost primes

![]() $n =p_1p_2$

such that each prime factor

$n =p_1p_2$

such that each prime factor

![]() $p=a^2+b^2$

, with

$p=a^2+b^2$

, with

![]() $0 \le b \le a$

, has the property that

$0 \le b \le a$

, has the property that

![]() $a+ib$

lies within a certain small sector.

$a+ib$

lies within a certain small sector.

We also will require the following result.

Proposition 2.2. We have that

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1 | Q_0 n+4 }} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) b(Q_0n+4) \asymp \varepsilon^2 \frac{x \log \log x}{ \varphi(Q_1) (\log x)^{3/2}}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1 | Q_0 n+4 }} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) b(Q_0n+4) \asymp \varepsilon^2 \frac{x \log \log x}{ \varphi(Q_1) (\log x)^{3/2}}. \end{align*}$$

Since Proposition 2.2 follows from a similar, yet simpler argument than the one used to prove Proposition 2.1, we will omit its proof. The rest of this section will be devoted to proving Proposition 2.1.

2.1 The Rosser–Iwaniec sieve

Let us first introduce the Rosser–Iwaniec

![]() $\beta $

-sieve and the classical sieve terminology. We start with a sequence of

$\beta $

-sieve and the classical sieve terminology. We start with a sequence of

![]() $\mathcal A=\{ a_n \}$

of nonnegative real numbers, a set of primes

$\mathcal A=\{ a_n \}$

of nonnegative real numbers, a set of primes

![]() ${\mathcal P}$

and a parameter z. Define

${\mathcal P}$

and a parameter z. Define

$$ \begin{align} P(z)=\prod_{\substack{p \in {\mathcal P} \\ p < z}} p. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} P(z)=\prod_{\substack{p \in {\mathcal P} \\ p < z}} p. \end{align} $$

Our goal is to obtain an estimate for the sieved set

$$\begin{align*}{\mathcal S}(\mathcal A, {\mathcal P}, z):=\sum_{\substack{n \le x \\ (n, P(z))=1}} a_n. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{\mathcal S}(\mathcal A, {\mathcal P}, z):=\sum_{\substack{n \le x \\ (n, P(z))=1}} a_n. \end{align*}$$

This will be accomplished through calculating, for square-free

![]() $d \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$d \in \mathbb {N}$

,

$$ \begin{align} A_d(x):=\sum_{\substack{n \le x \\ n \equiv 0\ \ \ \pmod d}} a_n. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} A_d(x):=\sum_{\substack{n \le x \\ n \equiv 0\ \ \ \pmod d}} a_n. \end{align} $$

We now make the hypothesis that our estimate for

![]() $A_d(x)$

will be of the form

$A_d(x)$

will be of the form

where

![]() $g(d)$

is a multiplicative function with

$g(d)$

is a multiplicative function with

![]() $0 \le g(p)<1$

. The number

$0 \le g(p)<1$

. The number

![]() $r_d$

should be thought of as a remainder term, so X is an approximation to

$r_d$

should be thought of as a remainder term, so X is an approximation to

![]() $A_1(x)$

, and the function

$A_1(x)$

, and the function

![]() $g(d)$

can be interpreted as a density.

$g(d)$

can be interpreted as a density.

Let

We further suppose for all

![]() $w<z$

that

$w<z$

that

$$ \begin{align} \frac{V(w)}{V(z)}=\prod_{\substack{w \le p <z \\p \in {\mathcal P}}}(1-g(p))^{-1} \le \left( \frac{\log z}{\log w}\right)^{\kappa}\left( 1+O\left( \frac{1}{\log w}\right)\right) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{V(w)}{V(z)}=\prod_{\substack{w \le p <z \\p \in {\mathcal P}}}(1-g(p))^{-1} \le \left( \frac{\log z}{\log w}\right)^{\kappa}\left( 1+O\left( \frac{1}{\log w}\right)\right) \end{align} $$

for some

![]() $\kappa>0$

. The constant

$\kappa>0$

. The constant

![]() $\kappa $

is referred to as the dimension of the sieve.

$\kappa $

is referred to as the dimension of the sieve.

Our arguments also require sieve weights. Let

![]() $\Lambda =\{ \lambda _{d}\}_d$

be a sequence of real numbers, where d ranges over square-free integers. The sequence

$\Lambda =\{ \lambda _{d}\}_d$

be a sequence of real numbers, where d ranges over square-free integers. The sequence

![]() $\Lambda $

is referred to as an upper bound sieve provided that

$\Lambda $

is referred to as an upper bound sieve provided that

where

![]() $1_{n=1}$

equals one if

$1_{n=1}$

equals one if

![]() $n=1$

and equals zero otherwise. We call

$n=1$

and equals zero otherwise. We call

![]() $\Lambda $

a lower bound sieve if

$\Lambda $

a lower bound sieve if

For a sieve

![]() $\Lambda =\{\lambda _d\}$

, we use the notation

$\Lambda =\{\lambda _d\}$

, we use the notation

(This will be used to show the existence of primes, or almost primes, with desired properties.) Additionally, we say that the sieve

![]() $\Lambda $

has level D if

$\Lambda $

has level D if

![]() $\lambda _d=0$

for

$\lambda _d=0$

for

![]() $d>D$

.

$d>D$

.

Given

![]() $\kappa>0$

, the

$\kappa>0$

, the

![]() $\beta $

-sieve gives both an upper and lower bound for

$\beta $

-sieve gives both an upper and lower bound for

![]() ${\mathcal S}(\mathcal A, {\mathcal P}, z)$

whenever

${\mathcal S}(\mathcal A, {\mathcal P}, z)$

whenever

![]() $s=\log D/\log z$

is sufficiently large in terms of

$s=\log D/\log z$

is sufficiently large in terms of

![]() $\kappa $

. The bounds consist of an error term, which is a sum of the remainder terms

$\kappa $

. The bounds consist of an error term, which is a sum of the remainder terms

![]() $|r_d|$

for

$|r_d|$

for

![]() $d \le D$

and a main term

$d \le D$

and a main term

![]() $XV(z)F(s)$

,

$XV(z)F(s)$

,

![]() $XV(z)f(s)$

(resp.), where

$XV(z)f(s)$

(resp.), where

![]() $F,f$

are certain continuous functions with

$F,f$

are certain continuous functions with

![]() $0 \le f(s) < 1 < F(s)$

. For precise definitions, motivation and context, we refer the reader to [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Chapter 11].

$0 \le f(s) < 1 < F(s)$

. For precise definitions, motivation and context, we refer the reader to [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Chapter 11].

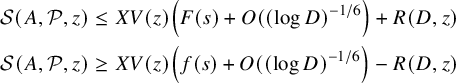

Theorem 2.1 (Cf. [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Theorem 11.13])

Let

![]() $D \ge z$

, and write

$D \ge z$

, and write

![]() $s=\frac {\log D}{\log z}$

. Then there exists

$s=\frac {\log D}{\log z}$

. Then there exists

![]() $\beta $

-sieve weights such that

$\beta $

-sieve weights such that

$$\begin{align*}\begin{aligned} {\mathcal S}(A, {\mathcal P}, z) \le X V(z)\left( F(s)+O(( \log D)^{-1/6}\right)+R(D,z)\\ {\mathcal S}(A, {\mathcal P}, z) \ge X V(z)\left( f(s)+O(( \log D)^{-1/6}\right)-R(D,z) \end{aligned} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\begin{aligned} {\mathcal S}(A, {\mathcal P}, z) \le X V(z)\left( F(s)+O(( \log D)^{-1/6}\right)+R(D,z)\\ {\mathcal S}(A, {\mathcal P}, z) \ge X V(z)\left( f(s)+O(( \log D)^{-1/6}\right)-R(D,z) \end{aligned} \end{align*}$$

for

![]() $s \ge \beta (\kappa )-1$

and

$s \ge \beta (\kappa )-1$

and

![]() $ s\ge \beta (\kappa )$

(resp.), where

$ s\ge \beta (\kappa )$

(resp.), where

$$\begin{align*}R(D,z) \le \sum_{\substack{d \le D \\ d|P(z)}} |r_d| \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}R(D,z) \le \sum_{\substack{d \le D \\ d|P(z)}} |r_d| \end{align*}$$

and

![]() $\beta (\kappa )$

denotes the sifting limit of dimension

$\beta (\kappa )$

denotes the sifting limit of dimension

![]() $\kappa $

(cf. [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Ch. 6.4].)

$\kappa $

(cf. [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Ch. 6.4].)

In particular, note that for

![]() $\kappa =1/2$

(which is of particular interest to us since we sieve out by the density

$\kappa =1/2$

(which is of particular interest to us since we sieve out by the density

![]() $1/2$

sequence of primes

$1/2$

sequence of primes

![]() $ \equiv 3\ \pmod 4 $

to detect sums of two squares), it is well known that

$ \equiv 3\ \pmod 4 $

to detect sums of two squares), it is well known that

![]() $\beta (\kappa ) =1$

(e.g., see [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Ch. 14.2]), which will be important for us as the ‘sifting variable’ s (which measures the sifting range relative to the sifting level, for example, smaller s corresponds to a smaller sifting range) only needs to be

$\beta (\kappa ) =1$

(e.g., see [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Ch. 14.2]), which will be important for us as the ‘sifting variable’ s (which measures the sifting range relative to the sifting level, for example, smaller s corresponds to a smaller sifting range) only needs to be

![]() $\ge 1$

to provide a lower bound for

$\ge 1$

to provide a lower bound for

![]() ${\mathcal S}(A,{\mathcal P},z)$

, whereas for the linear sieve

${\mathcal S}(A,{\mathcal P},z)$

, whereas for the linear sieve

![]() $\beta (1)=2$

so that one needs

$\beta (1)=2$

so that one needs

![]() $s \ge 2$

. In our arguments, we will use

$s \ge 2$

. In our arguments, we will use

![]() $\beta $

-sieve weights, which are as defined in [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15] Sections 6.4–6.5. In particular for these weights, we have

$\beta $

-sieve weights, which are as defined in [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15] Sections 6.4–6.5. In particular for these weights, we have

![]() $|\lambda _d| \le 1$

. We will sometimes refer to the fundamental lemma of the sieve, by which we mean the following result (see [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Lemma 6.11].)

$|\lambda _d| \le 1$

. We will sometimes refer to the fundamental lemma of the sieve, by which we mean the following result (see [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15, Lemma 6.11].)

Theorem 2.2. Let

![]() $\Lambda ^{\pm }=\{ \lambda _d^{\pm } \}$

be upper and lower bound (resp.)

$\Lambda ^{\pm }=\{ \lambda _d^{\pm } \}$

be upper and lower bound (resp.)

![]() $\beta $

-sieves of level D with

$\beta $

-sieves of level D with

![]() $\beta \ge 4 \kappa +1$

. Also, let

$\beta \ge 4 \kappa +1$

. Also, let

![]() $s=\log D/\log z$

. Then for any multiplicative function satisfying equation (2.5) and

$s=\log D/\log z$

. Then for any multiplicative function satisfying equation (2.5) and

![]() $s \ge \beta +1$

we have

$s \ge \beta +1$

we have

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{d|P(z)} \lambda_d^{\pm} g(d)=V(z)\left(1+O\left(s^{-s/2} \right) \right). \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{d|P(z)} \lambda_d^{\pm} g(d)=V(z)\left(1+O\left(s^{-s/2} \right) \right). \end{align*}$$

We also require the following estimate for the convolution of two sieves (see equation (5.97) and Theorem 5.9 of [Reference Friedlander and Iwaniec15]).

Theorem 2.3. Let

![]() $\Lambda _1=\{ \lambda _{d} \}$

and

$\Lambda _1=\{ \lambda _{d} \}$

and

![]() $\Lambda _2=\{ \lambda _{d}^{'} \}$

be upper-bound sieve weights of level

$\Lambda _2=\{ \lambda _{d}^{'} \}$

be upper-bound sieve weights of level

![]() $D_1,D_2$

(resp.). Also, let

$D_1,D_2$

(resp.). Also, let

![]() $g_1,g_2$

be multiplicative functions satisfying equation (2.5) with

$g_1,g_2$

be multiplicative functions satisfying equation (2.5) with

![]() $\kappa =1$

. Then

$\kappa =1$

. Then

$$\begin{align*}\bigg|\sum_{\substack{d,e \\ (d,e)=1 }} \lambda_d \lambda_e^{'} g_1(d)g_2(e) \bigg| \le (4 e^{2\gamma}+o(1)) \prod_{p}(1+h_1(p)h_2(p)) \prod_{j=1}^2 \prod_{p < D_j} (1-g_j(p)) \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\bigg|\sum_{\substack{d,e \\ (d,e)=1 }} \lambda_d \lambda_e^{'} g_1(d)g_2(e) \bigg| \le (4 e^{2\gamma}+o(1)) \prod_{p}(1+h_1(p)h_2(p)) \prod_{j=1}^2 \prod_{p < D_j} (1-g_j(p)) \end{align*}$$

as

![]() $\min \{D_1,D_2\} \rightarrow \infty $

, where for

$\min \{D_1,D_2\} \rightarrow \infty $

, where for

![]() $j=1,2$

,

$j=1,2$

,

![]() $ h_j(n)=g_j(n)(1-g_j(n))^{-1} $

and

$ h_j(n)=g_j(n)(1-g_j(n))^{-1} $

and

![]() $\gamma $

is Euler’s constant.

$\gamma $

is Euler’s constant.

If in addition

![]() $g_1(p), g_2(p) \le 1/p$

so that

$g_1(p), g_2(p) \le 1/p$

so that

![]() $h_1(p)h_2(p) \ll 1/p^2$

, which will be the case for us, then

$h_1(p)h_2(p) \ll 1/p^2$

, which will be the case for us, then

$$ \begin{align} \bigg| \sum_{\substack{d,e \\ (d,e)=1 }} \lambda_d \lambda_e^{'} g_1(d)g_2(e) \bigg| \le C \prod_{p< D_1}(1-g_1(p))\prod_{p<D_2}(1-g_2(p)), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \bigg| \sum_{\substack{d,e \\ (d,e)=1 }} \lambda_d \lambda_e^{'} g_1(d)g_2(e) \bigg| \le C \prod_{p< D_1}(1-g_1(p))\prod_{p<D_2}(1-g_2(p)), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $C>0$

is an absolute constant.

$C>0$

is an absolute constant.

2.1.1 Notation

We will also use the notation

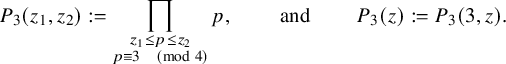

$$\begin{align*}P_3(z_1,z_2):=\prod_{\substack{z_1 \le p \le z_2 \\ p \equiv 3\ \ \ \pmod 4}} p, \qquad \text{ and }\qquad P_3(z):=P_3(3,z). \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}P_3(z_1,z_2):=\prod_{\substack{z_1 \le p \le z_2 \\ p \equiv 3\ \ \ \pmod 4}} p, \qquad \text{ and }\qquad P_3(z):=P_3(3,z). \end{align*}$$

Additionally, let

![]() $1(n)=1_{\mathbb N}(n)=1$

denote the identity function and let

$1(n)=1_{\mathbb N}(n)=1$

denote the identity function and let

![]() $\tau (n)=(1\ast 1)(n)=\sum _{d|n} 1$

. Also, define

$\tau (n)=(1\ast 1)(n)=\sum _{d|n} 1$

. Also, define

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal B(x;q,a,\varepsilon) := \sum_{\substack{ x \le n \le 2x\\ n \equiv a\ \ \ {\pmod q}}} (1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)-\frac{1}{\varphi(q)} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ (n,q)=1}} (1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}'}) (n). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal B(x;q,a,\varepsilon) := \sum_{\substack{ x \le n \le 2x\\ n \equiv a\ \ \ {\pmod q}}} (1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)-\frac{1}{\varphi(q)} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ (n,q)=1}} (1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{{{\mathcal P}}_{\varepsilon}'}) (n). \end{align} $$

Further,

![]() $\delta> 0$

will denote a small, but fixed real number.

$\delta> 0$

will denote a small, but fixed real number.

2.2 Preliminary lemmas

We begin by showing that the difference between the upper and lower bound sieves is ‘small’.

Lemma 2.1. Let

![]() $\Lambda ^{\pm }=\{ \lambda _d^{\pm }\}$

be upper and lower bound linear sieves (resp.) each of level

$\Lambda ^{\pm }=\{ \lambda _d^{\pm }\}$

be upper and lower bound linear sieves (resp.) each of level

![]() $w=x^{\sqrt {\eta }}$

, where

$w=x^{\sqrt {\eta }}$

, where

![]() $\eta>0$

is sufficiently small, whose sieve weights are supported on integers d such that

$\eta>0$

is sufficiently small, whose sieve weights are supported on integers d such that

![]() $d|P(y)$

, where

$d|P(y)$

, where

![]() $y=x^{\eta }$

,

$y=x^{\eta }$

,

![]() $y>Q_0Q_1$

, and

$y>Q_0Q_1$

, and

![]() $(d,2Q_0 f_1r_1)=1$

; in particular,

$(d,2Q_0 f_1r_1)=1$

; in particular,

Then

$$\begin{align*}\begin{aligned} &\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1|Q_0n+4}} \left((\lambda^+ \ast 1)\left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)-(\lambda^- \ast 1) \left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)\right) (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) \\ &\qquad \qquad \qquad \ll \varepsilon^{2} \eta^{1/(4\eta^{1/2})-1} \frac{Q_0}{\varphi(Q_0)} \frac{x \log \log x}{\varphi(Q_1) (\log x)^2}+\frac{x}{(\log x)^{10}}. \end{aligned}\\[-9pt] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\begin{aligned} &\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1|Q_0n+4}} \left((\lambda^+ \ast 1)\left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)-(\lambda^- \ast 1) \left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)\right) (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) \\ &\qquad \qquad \qquad \ll \varepsilon^{2} \eta^{1/(4\eta^{1/2})-1} \frac{Q_0}{\varphi(Q_0)} \frac{x \log \log x}{\varphi(Q_1) (\log x)^2}+\frac{x}{(\log x)^{10}}. \end{aligned}\\[-9pt] \end{align*}$$

Remark 2. We imposed the assumption that

![]() $\eta>0$

is sufficiently small so small that the error

$\eta>0$

is sufficiently small so small that the error

![]() $O(\eta ^{1/(4\eta ^{1/2})})$

in equation (2.16) is less than

$O(\eta ^{1/(4\eta ^{1/2})})$

in equation (2.16) is less than

![]() $1/2$

. The requirement

$1/2$

. The requirement

![]() $y>Q_0Q_1$

is not essential; in the case

$y>Q_0Q_1$

is not essential; in the case

![]() $y<Q_0Q_1$

the argument proceeds similarly, but some additional, straightforward estimates are needed to treat the contribution of the primes between y and

$y<Q_0Q_1$

the argument proceeds similarly, but some additional, straightforward estimates are needed to treat the contribution of the primes between y and

![]() $Q_0Q_1$

.

$Q_0Q_1$

.

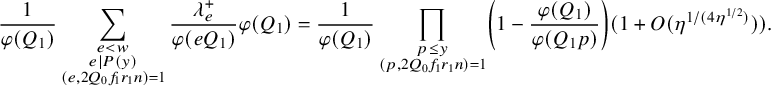

Proof. Switching order of summation, it follows that

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} &\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1|Q_0n+4}} \left((\lambda^+ \ast 1)\left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)-(\lambda^- \ast 1) \left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)\right) (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) \\ & \qquad \qquad \qquad = \sum_{\pm} \pm \sum_{\substack{d <w \\ d|P(y) \\ (d,2Q_0f_1r_1)=1}}\lambda_d^{\pm} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_0n+4 \equiv 0\ \ \ {\pmod dQ_1}}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n). \end{aligned}\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} &\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_1|Q_0n+4}} \left((\lambda^+ \ast 1)\left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)-(\lambda^- \ast 1) \left(\frac{Q_0n+4}{Q_1}\right)\right) (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) \\ & \qquad \qquad \qquad = \sum_{\pm} \pm \sum_{\substack{d <w \\ d|P(y) \\ (d,2Q_0f_1r_1)=1}}\lambda_d^{\pm} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_0n+4 \equiv 0\ \ \ {\pmod dQ_1}}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n). \end{aligned}\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

The inner sum on the right-hand side (RHS) of equation (2.12) equals

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{\varphi(dQ_1)} \sum_{\substack{x\le n \le 2x \\ (n,dQ_1)=1}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)+\mathcal B\left(x; dQ_1, \gamma, \varepsilon \right), \end{aligned}\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{\varphi(dQ_1)} \sum_{\substack{x\le n \le 2x \\ (n,dQ_1)=1}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)+\mathcal B\left(x; dQ_1, \gamma, \varepsilon \right), \end{aligned}\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\gamma $

is the unique reduced residue

$\gamma $

is the unique reduced residue

![]() $\pmod {dQ_1}$

satisfying

$\pmod {dQ_1}$

satisfying

![]() $\gamma \cdot Q_0 \equiv -4\ \pmod {dQ_1}$

and

$\gamma \cdot Q_0 \equiv -4\ \pmod {dQ_1}$

and

![]() $\mathcal B$

is as defined in equation (2.10). Also,

$\mathcal B$

is as defined in equation (2.10). Also,

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{\substack{ x\le n \le 2x \\ (n,dQ_1)=1}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)=\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x }} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)+O\bigg( \sum_{\substack{p_1p_2 \le 2x \\ (p_1p_2,dQ_1) \neq 1}}1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}}(p_1) 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'}(p_2) \bigg).\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{\substack{ x\le n \le 2x \\ (n,dQ_1)=1}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)=\sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x }} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)+O\bigg( \sum_{\substack{p_1p_2 \le 2x \\ (p_1p_2,dQ_1) \neq 1}}1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}}(p_1) 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'}(p_2) \bigg).\\[-9pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

Since

![]() $dQ_1 \le x^{1/9}$

(as

$dQ_1 \le x^{1/9}$

(as

![]() $\eta $

is small) and

$\eta $

is small) and

![]() $p_2 \le x^{1/9}$

the contribution to the error term from

$p_2 \le x^{1/9}$

the contribution to the error term from

![]() $p_1p_2 \le x$

with

$p_1p_2 \le x$

with

![]() $p_1|(p_1p_2,dQ_1)$

is

$p_1|(p_1p_2,dQ_1)$

is

![]() $\ll \sum _{p_2 \le x^{1/9}} \sum _{p_1 \le x^{1/9} } 1 \ll x^{2/9}$

. Also, since

$\ll \sum _{p_2 \le x^{1/9}} \sum _{p_1 \le x^{1/9} } 1 \ll x^{2/9}$

. Also, since

![]() $p_2 \ge (\log x)^{B_0}$

$p_2 \ge (\log x)^{B_0}$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{\substack{p_1p_2 \le 2x \\ (p_1p_2,dQ_1) = p_2}}1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}}(p_1) 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'}(p_2) \le \sum_{\substack{p_2|dQ_1 \\ p_2 \ge (\log x)^{B_0}}} \sum_{p_1 \le 2 x/p_2} 1 \ll \frac{x}{\log x} \sum_{\substack{p_2|dQ_1 \\ p_2 \ge (\log x)^{B_0}}} \frac{1}{p_2} \ll \frac{x (\log \log x)}{(\log x)^{B_0}}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{\substack{p_1p_2 \le 2x \\ (p_1p_2,dQ_1) = p_2}}1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}}(p_1) 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'}(p_2) \le \sum_{\substack{p_2|dQ_1 \\ p_2 \ge (\log x)^{B_0}}} \sum_{p_1 \le 2 x/p_2} 1 \ll \frac{x}{\log x} \sum_{\substack{p_2|dQ_1 \\ p_2 \ge (\log x)^{B_0}}} \frac{1}{p_2} \ll \frac{x (\log \log x)}{(\log x)^{B_0}}. \end{align} $$

Hence, using equations (2.13), (2.14) and (2.15) along with the fundamental lemma of the sieve (see Theorem 2.2 and recall

![]() $|\lambda _d|\le 1$

) with

$|\lambda _d|\le 1$

) with

![]() $g(d)=\varphi (Q_1)/\varphi (Q_1 d)$

,Footnote

2

and

$g(d)=\varphi (Q_1)/\varphi (Q_1 d)$

,Footnote

2

and

![]() $s=\log w/\log y=\eta ^{-1/2}$

we have that

$s=\log w/\log y=\eta ^{-1/2}$

we have that

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} &\sum_{\substack{d <w \\ d|P(y) \\ (d,2Q_0)=1}}\lambda_d^{\pm} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_0n+4 \equiv 0\ \ \ {\pmod dQ_1}}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)\\ &=\frac{1}{\varphi(Q_1)} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x }} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) \prod_{\substack{p \le y \\ (p , 2Q_0f_1r_1 )=1}}\left(1-\frac{\varphi(Q_1)}{\varphi(Q_1p)} \right)(1+O(\eta^{1/(4\eta^{1/2})}))\\ & \qquad \qquad \qquad +O\bigg( \sum_{\substack{d < w \\ (d,2)=1}} \left|\mathcal B \left(x; dQ_1, \gamma, \varepsilon \right)\right|\bigg)+O\left( \frac{x \log \log x}{(\log x)^{B_0-1}}\right). \end{aligned}\\[-17pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} &\sum_{\substack{d <w \\ d|P(y) \\ (d,2Q_0)=1}}\lambda_d^{\pm} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x \\ Q_0n+4 \equiv 0\ \ \ {\pmod dQ_1}}} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n)\\ &=\frac{1}{\varphi(Q_1)} \sum_{\substack{x \le n \le 2x }} (1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}} \ast 1_{ {\mathcal P}_{\varepsilon}'})(n) \prod_{\substack{p \le y \\ (p , 2Q_0f_1r_1 )=1}}\left(1-\frac{\varphi(Q_1)}{\varphi(Q_1p)} \right)(1+O(\eta^{1/(4\eta^{1/2})}))\\ & \qquad \qquad \qquad +O\bigg( \sum_{\substack{d < w \\ (d,2)=1}} \left|\mathcal B \left(x; dQ_1, \gamma, \varepsilon \right)\right|\bigg)+O\left( \frac{x \log \log x}{(\log x)^{B_0-1}}\right). \end{aligned}\\[-17pt]\nonumber \end{align} $$

Applying Theorem A.1 from the appendix, since

![]() $w=x^{\sqrt {\eta }} < x^{1/2-o(1)}$

we get that

$w=x^{\sqrt {\eta }} < x^{1/2-o(1)}$

we get that

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{d < w \\ (d,2)=1}} \left|\mathcal B \left(x; dQ_1, \gamma, \varepsilon \right)\right| \ll \frac{x}{ (\log x)^{10}}.\\[-17pt] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{d < w \\ (d,2)=1}} \left|\mathcal B \left(x; dQ_1, \gamma, \varepsilon \right)\right| \ll \frac{x}{ (\log x)^{10}}.\\[-17pt] \end{align*}$$

Using the two estimates above in equation (2.12) (note the main terms in equation (2.16) are the same for each of the sieves

![]() $\Lambda ^{\pm }$

so they cancel in equation (2.12)) and applying equation (A.3) (with

$\Lambda ^{\pm }$

so they cancel in equation (2.12)) and applying equation (A.3) (with

![]() $q=1$

) from the appendix to estimate the sum over n completes the proof upon noting that

$q=1$

) from the appendix to estimate the sum over n completes the proof upon noting that

$$\begin{align*}\prod_{\substack{p \le y \\ (p , 2Q_0f_1r_1)=1}}\left(1-\frac{\varphi(Q_1)}{\varphi(Q_1p)} \right) \asymp \frac{Q_0}{\varphi(Q_0) \log y} = \frac{Q_0}{\varphi(Q_0) \eta \log x}.\\[-56pt] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\prod_{\substack{p \le y \\ (p , 2Q_0f_1r_1)=1}}\left(1-\frac{\varphi(Q_1)}{\varphi(Q_1p)} \right) \asymp \frac{Q_0}{\varphi(Q_0) \log y} = \frac{Q_0}{\varphi(Q_0) \eta \log x}.\\[-56pt] \end{align*}$$