1. Introduction

My aim here is to critically engage with the novel meta-inductive approach to induction. Broadly speaking, the meta-inductive approach provides a justification of induction through a two-step process. The first “a priori” step consists in proving that meta-induction is optimal and the second “a posteriori” step consists in showing that meta-induction selects object-induction in our world.

Current engagement with and discussion of the meta-inductive approach have mostly been focused on the first step.Footnote 1 Departing from the existing literature, I will focus here on the second step. Although the first step faces some serious challenges (expanding pool of strategies, non-convex loss functions, appeal to bounded cognition, etc.), for the purposes of this paper I grant the the first step. Even with this substantial concession, I show that the meta-inductive approach faces significant obstacles.

I proceed as follows. In section 2 I briefly provide a sketch of the meta-inductive approach. This will help make clear the bipartite structure of the meta-inductive justification. Following this, I develop the identification problem (section 3) and the indetermination problem (section 4) for the meta-inductive approach. Section 5 concludes.

A preliminary before I start. I use “meta-induction” and “object-induction” to distinguish between induction at the level of methods (meta-induction) and induction at the level of objects (object-induction). However, where the context admits I sometimes use “induction” to stand for object-induction (but never for meta-induction).

2. The meta-inductive approach to induction

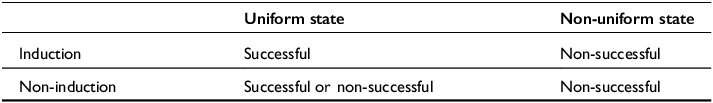

The pragmatic approach to induction—defended most famously by Hans Reichenbach—accepts that in light of Hume’s skeptical challenge a justification for the reliability of induction is not possible (Reichenbach Reference Reichenbach1938, Reference Reichenbach1949). Instead, Reichenbach suggests that a more modest aim is achievable: we can justify induction not by showing its reliability but by showing its optimality. On one reading of Reichenbach’s proposal, induction is justified because it is the most optimal method in predicting finite frequencies of observations.Footnote 2 He argues for this claim using an argument by cases. Dividing the space of states of the world into uniform and non-uniform states, he argues as follows (cf. table 1):

-

If the state of the world is uniform then the world is induction friendly. Hence, induction will be the best method vis-à-vis predictive success. Other methods might be successful but induction will be at least as successful as any other method. Thus induction is optimal (compared to all the other methods) over uniform states of the world.

-

If, however, the state of the world is non-uniform then induction will not be predictively successful. But in such a case no other prediction method will be successful as well. Thus, induction is optimal over non-uniform states of the world.

Table 1. Reichenbach’s matrix, as reconstructed in Salmon (Reference Salmon and Swinburne1974)

| Uniform state | Non-uniform state | |

|---|---|---|

| Induction | Successful | Non-successful |

| Non-induction | Successful or non-successful | Non-successful |

The point of weakness in Reichenbach’s argument is his claim that if the state of the world is non-uniform then no non-inductive method can be successful. As Salmon (Reference Salmon and Swinburne1974) points out, this is incorrect. Consider a non-uniform state of the world where an oracle has foreknowledge. Even though the world is inhospitable to induction, it is a world where a non-inductive method can have an arbitrarily high success rate. Hence, Reichenbach’s claim that induction is optimal when the state of the world is non-uniform fails. Facing this objection, Reichenbach tweaked his account to explicitly take into consideration situations where a non-inductive method can outperform induction. He argued that in such cases (for example, for an oracle in a non-uniform world) induction will still be as successful as the oracle because an inductive method will latch onto the oracle’s predictions. Reichenbach, however, provides no argument to support the claim that such a strategy can be implemented. Taking the advice from Salmon that Reichenbach provides “a valid core from which we may attempt to develop a more satisfactory justification” of induction, the meta-inductive approach to induction aims to provide a rigorous argument to show just how induction is optimal (Salmon Reference Salmon1967, 54).

The meta-inductive approach uses tools and results from machine learning, in particular from the area of online learning under expert advice (Cesa-Bianchi and Lugosi Reference Cesa-Bianchi and Lugosi2006; Rieskamp and Otto Reference Rieskamp and Otto2006; Dieckmann and Todd Reference Dieckmann, Todd, Peter and Gigerenzer2012). The framework used is that of prediction games and consists of the following components:

-

(1) Events: Individual events are the target for predictions and a stream of events is represented by an infinite sequence of events

${\bf{e}} = {e_1},{e_2},{e_3}, \ldots $

Each individual event is represented by a real number in the interval

${\bf{e}} = {e_1},{e_2},{e_3}, \ldots $

Each individual event is represented by a real number in the interval

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

and can be thought of as a measurement or observation of the quantity of interest.Footnote

3

Denote by

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

and can be thought of as a measurement or observation of the quantity of interest.Footnote

3

Denote by

${e_n}$

the

${e_n}$

the

$n$

th event in an event sequence

$n$

th event in an event sequence

${\bf{e}}$

.

${\bf{e}}$

. -

(2) Methods: Every non-meta-inductive method (or player or prediction strategy)

$p$

is a member of the finite pool of methods

$p$

is a member of the finite pool of methods

${\rm{\Pi }} = \left\{ {{p_1},{p_2}, \ldots, {p_n}} \right\}$

.Footnote

4

Each prediction strategy specifies a prediction for the next event. Denote by

${\rm{\Pi }} = \left\{ {{p_1},{p_2}, \ldots, {p_n}} \right\}$

.Footnote

4

Each prediction strategy specifies a prediction for the next event. Denote by

${{\rm{\Pi }}^{\rm{*}}} = \left\{ {{p_1},{p_2}, \ldots, {p_n},{\rm{MI}}} \right\}$

the pool of methods in

${{\rm{\Pi }}^{\rm{*}}} = \left\{ {{p_1},{p_2}, \ldots, {p_n},{\rm{MI}}} \right\}$

the pool of methods in

${\rm{\Pi }}$

and the meta-inductive method

${\rm{\Pi }}$

and the meta-inductive method

${\rm{MI}}$

.

${\rm{MI}}$

. -

(3) Prediction: A prediction

${\cal P}_n^p$

at stage

${\cal P}_n^p$

at stage

$n$

for the event at stage

$n$

for the event at stage

$n + 1$

by a method

$n + 1$

by a method

$p \in {{\rm{\Pi }}^{\rm{*}}}$

is a real number in the interval

$p \in {{\rm{\Pi }}^{\rm{*}}}$

is a real number in the interval

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

.Footnote

5

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

.Footnote

5

-

(4) Loss function: A loss function

${\cal L}\left( {{\cal P}_n^p,{e_n}} \right)$

is a measure of how far the prediction of method

${\cal L}\left( {{\cal P}_n^p,{e_n}} \right)$

is a measure of how far the prediction of method

$p$

was from the true value of event

$p$

was from the true value of event

${e_n}$

at stage

${e_n}$

at stage

$n$

of the prediction game. Loss functions are monotonic and convex.Footnote

6

$n$

of the prediction game. Loss functions are monotonic and convex.Footnote

6

-

(5) Prediction games: A prediction game

$\left( {{\bf{e}},{{\rm{\Pi }}^{\rm{*}}},{\cal L}} \right)$

is a tuple of a sequence of events, a pool of methods, and a loss function. At each stage of the game, methods in the pool make predictions for the next stage of the game. These predictions are then evaluated with respect to the true value of the event using the loss function. One can then define the notion of the success rate of each method in the pool. The success rate of a method

$\left( {{\bf{e}},{{\rm{\Pi }}^{\rm{*}}},{\cal L}} \right)$

is a tuple of a sequence of events, a pool of methods, and a loss function. At each stage of the game, methods in the pool make predictions for the next stage of the game. These predictions are then evaluated with respect to the true value of the event using the loss function. One can then define the notion of the success rate of each method in the pool. The success rate of a method

$p$

at the

$p$

at the

$n$

th stage of the prediction game is(1)

$n$

th stage of the prediction game is(1) $${\rm{suc}}{{\rm{c}}_n}\left( p \right) = {1 \over n}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n - 1} \left( {1 - {\cal L}\left( {{\cal P}_i^p,{e_i}} \right)} \right).$$

$${\rm{suc}}{{\rm{c}}_n}\left( p \right) = {1 \over n}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n - 1} \left( {1 - {\cal L}\left( {{\cal P}_i^p,{e_i}} \right)} \right).$$

A meta-inductive method,

![]() ${\rm{MI}}$

, is a method that predicts at stage

${\rm{MI}}$

, is a method that predicts at stage

![]() $n$

by accessing the prediction of all the other non-inductive methods at

$n$

by accessing the prediction of all the other non-inductive methods at

![]() $n$

. The simplest meta-inductive method, “imitate the best,” predicts at

$n$

. The simplest meta-inductive method, “imitate the best,” predicts at

![]() $n$

identical to the non-inductive method with the highest success rate at

$n$

identical to the non-inductive method with the highest success rate at

![]() $n$

.Footnote

7

Schurz (Reference Schurz2019) discusses other more complex meta-inductive methods, including the attractivity-weighted method, the exponentially weighted method, and the collective method. I will use the result of the attractivity-weighted method (

$n$

.Footnote

7

Schurz (Reference Schurz2019) discusses other more complex meta-inductive methods, including the attractivity-weighted method, the exponentially weighted method, and the collective method. I will use the result of the attractivity-weighted method (

![]() ${\rm{aMI}}$

) below.Footnote

8

${\rm{aMI}}$

) below.Footnote

8

The meta-inductive justification of induction consists of two steps. The goal of the first step is to show that the meta-induction—induction over prediction methods—is universally access optimal. A method

![]() $p$

is universally access optimal just in case it is optimal in all prediction games where the methods in

$p$

is universally access optimal just in case it is optimal in all prediction games where the methods in

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }} - \left\{ p \right\}$

are accessible to

${\rm{\Pi }} - \left\{ p \right\}$

are accessible to

![]() $p$

. A method

$p$

. A method

![]() $p^{\rm{\prime}} \in {\rm{\Pi }} - \left\{ p \right\}$

is accessible to

$p^{\rm{\prime}} \in {\rm{\Pi }} - \left\{ p \right\}$

is accessible to

![]() $p$

iff

$p$

iff

![]() $p$

knows the prediction made by

$p$

knows the prediction made by

![]() $p^{\rm{\prime}}$

at any stage of the prediction game and keeps a record of the

$p^{\rm{\prime}}$

at any stage of the prediction game and keeps a record of the

![]() $p^{\rm{\prime}}$

success rate in memory. The notion of universal access optimality is operationalized in the meta-inductive framework by an attractivity (or equivalently a regret) parameter that measures how much a method is attractive to the MI method. For MI, the attractivity with respect to a method

$p^{\rm{\prime}}$

success rate in memory. The notion of universal access optimality is operationalized in the meta-inductive framework by an attractivity (or equivalently a regret) parameter that measures how much a method is attractive to the MI method. For MI, the attractivity with respect to a method

![]() $p$

at a stage

$p$

at a stage

![]() $n$

is

$n$

is

With this in hand, the attractivity-weighted meta-inductive (

![]() ${\rm{aMI}}$

) method can be formulated through the following prediction strategy:

${\rm{aMI}}$

) method can be formulated through the following prediction strategy:

$${\cal P}_{n + 1}^{aMI} = {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{p \in {\rm{\Pi }}} {w_n}\left( p \right) \cdot {\cal P}_{n + 1}^p} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{p \in {\rm{\Pi }}} {w_n}\left( p \right)}},$$

$${\cal P}_{n + 1}^{aMI} = {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{p \in {\rm{\Pi }}} {w_n}\left( p \right) \cdot {\cal P}_{n + 1}^p} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{p \in {\rm{\Pi }}} {w_n}\left( p \right)}},$$

where

![]() ${w_n}\left( p \right)$

is the factor by which aMI weighs the prediction of

${w_n}\left( p \right)$

is the factor by which aMI weighs the prediction of

![]() $p$

at stage

$p$

at stage

![]() $n$

using the attractivity:

$n$

using the attractivity:

It can then be proved that for all convex loss functions, all

![]() $p \in {\rm{\Pi }}$

and all

$p \in {\rm{\Pi }}$

and all

![]() $n \geqslant 1$

(Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 143),

$n \geqslant 1$

(Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 143),

where

![]() $m$

is a constant that depends on the size of

$m$

is a constant that depends on the size of

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }}$

. In the long-run limit the loss rate of aMI is strictly no less worse than any other method. That is,

${\rm{\Pi }}$

. In the long-run limit the loss rate of aMI is strictly no less worse than any other method. That is,

This convergence result (and the short-run result) is taken to show that meta-induction is universally access optimal. The proponent of the meta-inductive approach thus concludes that if prediction is our goal, then in a very rigorous and clear sense, we are best off with meta-induction (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 199). Sure, the proponent concedes, some states of the world will be such that an oracle or a soothsayer will predict perfectly. But without making any assumptions about the state of the world, meta-induction will be the best strategy to follow.

But we should not miss the woods for the trees. The project is to justify object-induction not meta-induction. The first step in the argument is an argument for the universal access optimality of meta-induction and the second step is supposed to provide a justification of object-induction and an answer to Hume’s challenge. The second step establishes the claim that the predictions of meta-induction are identical (or arbitrarily close) to object-induction in our actual world. It is interesting to note, however, that Schurz dedicates less than two pages in his 372-page tome in discussing the second step of the argument. I quote his argument for the second step in full:

Until the present time and according to the presently available evidence, object-inductive methods dominated noninductive methods in the following sense: in many fields some object-inductive method was significantly more successful than every noninductive method, though in no field was a noninductive method significantly more successful than all object-inductive methods. (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 209)

The observation that no non-inductive method has been substantially more successful than any object-inductive method forms the basis of the meta-inductive conclusion that the universal access optimality of meta-induction provides an a posteriori justification of object-induction (Schurz Reference Schurz2021, 987). Because we have evidence for the significant success of object-induction, the meta-inductive argument goes, meta-induction selects object-induction in our world. And since we are justified in following meta-induction because of the first step of the argument, we are thus justified in following object-induction. The warrant, in this sense, flows from the level of methods where meta-induction lives to the level of object-induction. Thus, on the meta-inductive approach, this two-step strategy provides a non-circular justification of object-induction, solving Hume’s challenge (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 197).

3. Identification in meta-induction

Meta-induction selects object-induction, and hence justifies it, only if object-induction has so far been the most successful method. But how is object-induction identified? This is the identification problem for the meta-inductive approach to induction.

A first-pass response is to claim that it is futile to identify object-induction generally. Instead we must identify object-induction by looking in the domains where it has been successful and unsuccessful. The motivation for this is the observation that object-induction has been extremely successful in many domains of scientific and non-scientific inquiry while simultaneously being unsuccessful in other domains. On the one hand, for example, object-induction predicts that the sun will rise tomorrow. Similarly, object-induction has been significantly successful in scientific inquiry. For example, by induction on the mass of observed electrons, object-induction informs us that all electrons will have a mass of

![]() $9.11 \times {10^{ - 31}}$

kg. On the other hand, object-induction has been unsuccessful in many domains of scientific and non-scientific inquiry as well. For example, object-induction provides little useful guidance in predicting stock prices or in guiding us in the area of physics beyond the Standard Model.

$9.11 \times {10^{ - 31}}$

kg. On the other hand, object-induction has been unsuccessful in many domains of scientific and non-scientific inquiry as well. For example, object-induction provides little useful guidance in predicting stock prices or in guiding us in the area of physics beyond the Standard Model.

The first-pass response solves the identification problem by a divide-and-conquer approach: we should only investigate induction-friendly domains. The method that works in those domains is induction. However, this divide-and-conquer response to the identification problem faces difficulties. Sure, there are induction-hostile and induction-hospitable domains, but this response does not give any guidance in picking out object-induction from among other methods in the pool of methods. The identification problem bestows a duty on the meta-inductive approach to provide a principled way to identify object-induction. Only once object-induction is identified can its track record be checked and (if it is significantly more successful than other methods) its use justified. Until object-induction can be identified, Hume’s challenge remains.

A better response than the first-pass divide-and-conquer response was recently proposed in Schurz and Thorn (Reference Schurz and Thorn2020). According to them, Norton’s material theory of induction provides an elegant criterion to identify object-inductive methods in a specific domain (Norton Reference Norton2003, Reference Norton2021). On the material theory of induction, there is no universal schema of induction. Instead, all induction is local and tied to a domain. Norton’s project, as he emphasizes, is not to provide an answer to Hume’s challenge but to provide a criterion to distinguish between good and bad scientific inductive inferences. In the material theory, an induction is good just in case there are local background facts that warrant the particular induction. Norton uses the analogy of placing stones in a self-supporting arch to illuminate the structure the local background facts must conform to. Each stone or background fact is independently well-confirmed and supports every other fact in the arch. Schurz and Thorn argue that the material theory and the meta-inductive approach are “complementary” (Schurz and Thorn Reference Schurz and Thorn2020, 93). The material theory solves the identification problem for meta-induction by supplying “domain-specific aspects of object-induction.” The thought is that the material theory provides a principled criterion to identify induction-friendly domains and pick out object-induction. Of course, because the material theory denies that any universal schema of induction exists, the method the material theory specifies will be local and domain dependent. But it is claimed that that is no bug but a feature:

… there are many domains in which the superiority of object-inductive prediction methods is not obvious. This latter point brings us back to Norton’s material account of object-induction. It is only in domains that are regulated by strong uniformities that the superiority of object-inductive methods over noninductive methods of prediction will be strong enough that it can convince even skeptical persons. The strength of Norton’s material account of object-induction lies in the fact of illuminating the detailed structure of these local uniformities that make the success of inductions in science possible. (Schurz and Thorn Reference Schurz and Thorn2020, 92)

This might seem to allay the problem for meta-induction raised by the identification problem. However, this is mistaken. The material theory and meta-induction are in tension. The material theory and meta-induction are not complementary. Here are two reasons why.

First, the clearest way to see the tension inherent between the material and the meta-inductive approach is by noting that there are cases where their judgments diverge. Examples of this kind are abundant because of the disparate weights meta-induction and material theory place on past successes. While which (if any) method is picked out on the meta-inductive approach depends entirely on the track record of the method, the material theory has no time for past successes. The material theory, unlike the meta-inductive approach, is “memoryless”: the success or failure of past predictions do not play any role in judging whether an inductive inference is good or bad. In the material theory, it is the background facts of the domain and not facts about the success of the methods that determine the goodness of an inductive inference.

One can manufacture cases where the background facts obtain for an inductive inference but the success rate of any object-inference method has not yet been substantially greater than other methods in the pool. In such cases the material theory will judge inductive inferences as good while the meta-inductive approach will not deem object-induction as the favored method. Consider as an example of such a case the discovery of the properties of radium chloride by Marie Curie, discussed in Norton (Reference Norton2021). According to the material theory, Curie’s inference that radium chloride has the same crystalline form as barium chloride is a good inductive inference. It is good because it is warranted by a local background fact—the Weakened Haüy’s Principle. But meta-induction does not pick out Curie’s inference because at the turn of the century it was nowhere near (substantially) more successful than any other predictive method.

Indeed, many scientific discoveries only become significantly successful after some time has elapsed from their conception. Because it does not depend on the success rate of a method, the material theory will still judge these inferences to be good. However, the meta-inductive approach will not judge these inferences as the ones we should follow. Such examples can be easily multiplied.

The second reason, the other way in which the material theory and the meta-inductive approach are in tension, relates to a crucial background assumption. A central assumption of the meta-inductive approach is the assumption of cognitive finiteness (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 266). Schurz uses this assumption to defend the meta-inductive approach against Arnold’s (Reference Arnold2010) critique of the finite pool of methods. According to the cognitive finiteness assumption, the fact that humans are cognitively bounded agents plays an important and central role in the justification of induction. For example, the finiteness of

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }}$

is justified because the cognitive finiteness assumption precludes having infinite methods under consideration.

${\rm{\Pi }}$

is justified because the cognitive finiteness assumption precludes having infinite methods under consideration.

Using such an assumption to justify induction is anathema to the material-theorist. In the material account of induction, there is no place at all for considerations about human cognition and capabilities. Indeed, the material account goes even further. Humans or any other inference-doers are not necessary for the material account. For example, if humans did not exist, there would still be good and bad inductive inference. From the viewpoint of the meta-inductive approach that justifies object-induction based on the success of object-induction, such a claim seems bizarre. On the meta-inductive approach, if there are no inference-doers there is no method one should follow. Thus, the appeal to the material theory to assuage the identification problem fails because of inherent and inescapable tension between the material theory and the meta-inductive approach. The identification problem remains a serious issue for the meta-inductive approach.

4. Indetermination in meta-induction

Suppose, modulo the identification problem presented above, there is a principled way to identify object-induction. Even so, the second step fails because meta-induction fails to uniquely select object-induction. This is the indetermination problem for the meta-inductive approach.

Indetermination arises because, at any stage, there exist many methods that have the success rate (and hence the same attractivity to a meta-inductive method) as object-induction. And moreover, these equal-success-rate methods diverge from object-induction at some stage in the future and are non-identical to object-induction. That this is the case is straightforward to see. Recall that event sequences consist of infinite individual events

![]() ${\bf{e}}$

(where

${\bf{e}}$

(where

![]() ${\bf{e}} = {e_1},{e_2},{e_3}, \ldots $

). Now consider the set

${\bf{e}} = {e_1},{e_2},{e_3}, \ldots $

). Now consider the set

![]() ${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}} \subset {\rm{\Pi }}$

of Goodman methods at the stage

${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}} \subset {\rm{\Pi }}$

of Goodman methods at the stage

![]() $n$

. The membership of

$n$

. The membership of

![]() ${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

at

${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

at

![]() $n$

can be enumerated as follows:

$n$

can be enumerated as follows:

p1: Method

![]() ${p_1}$

predicts identically to object-induction up until

${p_1}$

predicts identically to object-induction up until

![]() $n$

but predicts differently from object-induction at

$n$

but predicts differently from object-induction at

![]() $n + 1$

.

$n + 1$

.

p2: Method

![]() ${p_2}$

predicts identically to object-induction up until

${p_2}$

predicts identically to object-induction up until

![]() $n$

but predicts differently from object-induction at

$n$

but predicts differently from object-induction at

![]() $n + 2$

.

$n + 2$

.

p3: Method

![]() ${p_3}$

predicts identically to object-induction up until

${p_3}$

predicts identically to object-induction up until

![]() $n$

but predicts differently from object-induction at

$n$

but predicts differently from object-induction at

![]() $n + 3$

.

$n + 3$

.

⋮

Even if one grants the assumption that

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }}$

contains finitely many methods, the indetermination problem remains nebulous. The second step of meta-induction does not provide a justification for object-induction uniquely. At best, if everything works, at

${\rm{\Pi }}$

contains finitely many methods, the indetermination problem remains nebulous. The second step of meta-induction does not provide a justification for object-induction uniquely. At best, if everything works, at

![]() $n$

the second step selects all the methods in

$n$

the second step selects all the methods in

![]() ${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

plus object-induction. The meta-inductive approach cannot justify induction uniquely.

${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

plus object-induction. The meta-inductive approach cannot justify induction uniquely.

This result is significantly more problematic for meta-induction than the challenge presented in Sterkenburg (Reference Sterkenburg2020). Sterkenburg argues that meta-induction cannot provide justification for object-induction simpliciter. Instead, he claims that the second step of the argument warrants a more modest claim: object-induction is justified now. However, indetermination using Goodman methods blocks even this more modest claim. Given the indetermination problem, meta-induction cannot even justify object-induction now. The claim must be even more modest. The meta-inductive approach provides us, at most, that some method in

![]() ${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

is justified now. From this very weak conclusion, it does not follow that object-induction is justified. This is very far from responding to Hume’s challenge.

${{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

is justified now. From this very weak conclusion, it does not follow that object-induction is justified. This is very far from responding to Hume’s challenge.

Is there a response to the indetermination highlighted here? A potential reply is provided by Schurz in discussing what he calls the selection problem, the problem of selecting which methods to include in

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }}$

. In providing a criterion for selecting methods that go into the pool

${\rm{\Pi }}$

. In providing a criterion for selecting methods that go into the pool

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }}$

, Schurz argues against the inclusion of Goodman methods by pointing out that they are algorithmically more complex than non-Goodman methods. He appeals to the notion of Kolmogorov complexity to choose methods that have higher “epistemic naturalness” (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 269). Appealing to complexity to exclude Goodman methods from entering into

${\rm{\Pi }}$

, Schurz argues against the inclusion of Goodman methods by pointing out that they are algorithmically more complex than non-Goodman methods. He appeals to the notion of Kolmogorov complexity to choose methods that have higher “epistemic naturalness” (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 269). Appealing to complexity to exclude Goodman methods from entering into

![]() ${\rm{\Pi }}$

from the start trivially dissolves the indetermination problem. However, this reply does not work.

${\rm{\Pi }}$

from the start trivially dissolves the indetermination problem. However, this reply does not work.

If the meta-inductive approach includes any inductive assumption, charges of circularity will naturally follow and the meta-inductive justification of induction will fail. This is evident in Schurz’s rejection of Goodman’s solution of inductive projectability to the the new problem of induction on the basis that Goodman’s solution is “circular” (Schurz Reference Schurz2019, 271). But in appealing to algorithmic simplicity and epistemic naturalness to solve the selection problem (and the indetermination problem), the meta-inductive approach inadvertently makes an inductive (and hence an inadmissible) assumption.

To claim that one should favor simpler rather than complex methods is making a claim about the world. Thinking that only simpler non-Goodman methods can be included in the pool of methods amounts to weighting more complex Goodman methods (

![]() $p \in {{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

) by zero. But that is just to say that we assume that a Goodman method cannot predict, with a perfect success rate, the true event sequence. This is clearly an inductive assumption. If one of the most attractive features of the meta-inductive approach is its independence from any inductive assumptions, then the problem of indetermination cannot be solved by any appeal to simplicity (or naturalness).

$p \in {{\rm{\Pi }}_{\rm{G}}}$

) by zero. But that is just to say that we assume that a Goodman method cannot predict, with a perfect success rate, the true event sequence. This is clearly an inductive assumption. If one of the most attractive features of the meta-inductive approach is its independence from any inductive assumptions, then the problem of indetermination cannot be solved by any appeal to simplicity (or naturalness).

Although it is true that we observe in our actual worlds that simple non-Goodman methods are more successful than gerrymandered Goodman methods, such an observation cannot support the meta-inductive approach. It cannot solve the indetermination problem. The prospects for the meta-inductive approach look bleak.

5. Conclusion

The meta-inductive approach is a novel and a well-thought-out response to Hume’s challenge. Two developments are particularly welcomed. First, shifting the focus from the reliability of induction to its optimality seems to be a more fruitful and fertile philosophical program. And second, justifying induction in a two-step process with an empirical second step is promising because it justifies induction only for our actual world rather than justifying induction for all worlds (something that has proven to be extremely difficult).

Although the meta-inductive approach should be commended for these aspects, I have raised two problems for the approach here. Instead of focusing on the first step of the argument, which has received the most critical attention, I focused on the second step. I introduced two problems for meta-induction: the identification problem and the indetermination problem. Both are serious and possibly fatal to the meta-inductive approach. I entertained some potential replies but concluded that none are helpful. These problems are especially concerning for any meta-inductive approach because they block the empirical part of the approach and thus these cannot be resolved by theoretical advances in machine learning, which is the foundation for the meta-inductive approach.

Acknowledgments

For her discussions, encouragement, and comments on previous versions of this paper, I am grateful to Francesca Zaffora Blando. Thanks also to John D. Norton and audiences at the 29th PSA biennial in New Orleans and the Pittsburgh History and Philosophy of Science WiP seminar in Fall 2024.

Funding disclosure

None to declare.

Competing interests

None to declare.