Introduction

Catsharks are a diverse group of small, bottom-dwelling, generally non-migratory sharks characterized by their elongated, cat-like eyes, adapted for seeing in low light conditions (Compagno, Reference Compagno1984). They were originally classified within the family Scyliorhinidae. However, following a taxonomic revision that distinguished between catsharks and deepwater catsharks, the latter were transferred into a separate family, the Pentanchidae (Iglésias et al., Reference Iglésias, Lecointre and Sellos2005), now considered the largest family of living sharks. Despite the species richness, many pentanchid sharks are poorly known, most likely due to their life history in deepwaters, where research is still scarce but expanding (Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Dando and Fowler2021). Although the deep sea comprises over 90% of the World’s oceans and represents the largest biome on this planet, vast areas remain unknown and discovery rates of new species are high (Ramirez-Llodra et al., Reference Ramirez-Llodra, Brandt, Danovaro, De Mol, Escobar, German, Levin, Martinez Arbizu, Menot, Buhl-Mortensen, Narayanaswamy, Smith, Tittensor, Tyler, Vanreusel and Vecchione2010; Selbach and Paterson, Reference Selbach and Paterson2025). Despite the ecological significance and unique marine environment of Icelandic waters (North-East [NE] Atlantic Ocean), their marine biodiversity remains relatively understudied (Omarsdottir et al., Reference Omarsdottir, Einarsdottir, Ögmundsdottir, Freysdottir, Olafsdottir, Molinski and Svavarsson2013). In this region, 3 pentanchids, namely the Iceland catshark [Apristurus laurussonii (Saemundsson)], the white ghost catshark (Apristurus aphyodes Nakaya & Stehmann), and the mouse catshark [Galeus murinus (Collett)] are among the most frequent chondrichthyans (Jakobsdóttir et al., Reference Jakobsdóttir, Hjörleifsson, Pétursson, Björnsson, Sólmundsson, Kristinsson and Bogason2023). They are small (i.e. less than 80 cm in length), bottom-dwelling species distributed in the NE Atlantic Ocean (A. laurussonii shows the broadest distribution encompassing North and Central Atlantic waters) and found across a wide depth range in the continental slopes (between 380 and 2060 m, Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Dando and Fowler2021). Currently classified as ‘Least Concern’ in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, they are generally attributed stable population trends (A. laurussoni and G. murinus) (Iglésias, Reference Iglésias2015; Walls, Reference Walls2015; Kulka et al., Reference Kulka, Cotton, Anderson, Crysler, Herman and Dulvy2020). Despite their abundance and ecological importance in North Atlantic waters, knowledge on their basic biology (i.e. diet, behaviour) and parasite infections, among others, remains limited.

Parasites represent a significant portion of living organisms (Poulin, Reference Poulin2014) and play a significant role in determining the structure of communities and ecosystems through interactions with their hosts, influencing their behaviour and fitness and ultimately regulating their populations (Price et al., Reference Price, Westoby, Rice, Atsatt, Fritz, Thompson and Mobley1986; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Renaud, de Meeus and Poulin1998; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Byers, Cottingham, Altman, Donahue and Blakeslee2007). They are also useful bioindicators, being able to provide valuable information on their host species, such as trophic interactions and migration patterns (and thus habitat preferences based on prey availability) (Williams et al., Reference Williams, MacKenzie and McCarthy1992; Alarcos and Timi, Reference Alarcos and Timi2013; Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017), or reveal responses of free-living populations and communities to environmental impacts (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie1999; Vidal-Martínez et al., Reference Vidal-Martínez, Pech, Sures, Purucker and Poulin2010). They have been used for many decades as indicators of fish population stocks, to address host phylogenetic relationships (MacKenzie and Abaunza, Reference MacKenzie and Abaunza1998; Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Marcogliese, Locke, McLaughlin and Marcogliese2013) and, more recently, to help assessing the effectiveness of protected conservation areas (Braicovich et al., Reference Braicovich, Irigoitia, Bovcon and Timi2021). Despite playing a vital role in marine ecosystems and constituting an important component of Ocean’s biodiversity, fish parasites have often been neglected in biodiversity and ecosystemic studies (Klimpel et al., Reference Klimpel, Palm, Busch, Kellermanns and Rückert2006).

As for many other North Atlantic elasmobranch species, studies on parasite communities of Icelandic deepwater catsharks are almost entirely absent. For instance, only a single parasite species has been recorded from A. laurussonii and A. aphyodes, the cestodes Ditrachybothridium macrocephalum Rees, 1959 and Yamaguticestus kuchtai Caira, Pickering & Jensen, Reference Caira, Pickering and Jensen2021(Bray and Olson, Reference Bray and Olson2004; Caira et al., Reference Caira, Pickering and Jensen2021), respectively, while parasite records from G. murinus are entirely lacking.

In contrast, there are a considerable number of studies on different ecological aspects of the 2 most common catsharks distributed not only in the Atlantic Ocean but also in the Mediterranean Sea, namely the blackmouth catshark (Galeus melastomus Rafinesque) and the small-spotted catshark [Scyliorhinus canicula (L.)] (Massutí and Moranta, Reference Massutí and Moranta2003; Follesa et al., Reference Follesa, Marongiu, Zupa, Bellodi, Cau, Cannas, Colloca, Djurovic, Isajlovic, Jadaud, Manfredi, Mulas, Peristeraki, Porcu, Ramirez-Amaro, Jiménez, Serena, Sion, Thasitis and Carbonara2019). Their parasite community is particularly well-known and characterized, with 20 and 29 parasite species, respectively, reported across their respective distribution ranges, including monogeneans, cestodes, trematodes, nematodes, copepods and isopods (see Pollerspöck and Straube, Reference Pollerspöck and Straube2025 for a complete list of references). In the Balearic Sea alone, 15 and 12 parasite species have been reported infecting G. melastomus and S. canicula, respectively (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017; Higueruelo et al., Reference Higueruelo, Constenla, Padrós, Sánchez-Marín, Carrassón, Soler-Membrives and Dallarés2024). Given the relatively high diversity of parasites found in Mediterranean catsharks, and considering the higher biomass, species richness and abundance of deep-sea fish assemblages in the Atlantic (Massutí et al., Reference Massutí, Gordon, Morata, Swan, Stefanescu and Merrett2004), it is likely that North Atlantic catsharks will reveal broader parasite communities with potentially new species yet to be discovered.

Although molecular ecology and the use of genetic tools are still poorly applied in parasitology compared to free-living organisms (Selbach et al., Reference Selbach, Jorge, Dowle, Bennett, Chai, Doherty, Eriksson, Filion, Hay, Herbison, Lindner, Park, Presswell, Ruehle, Sobrinho, Wainwright and Poulin2019), molecular tools are of great interest for addressing parasite species identification and host specificity (Criscione et al., Reference Criscione, Poulin and Blouin2005). These tools are highly advisable for the characterization of parasite assemblages, where larval forms (impossible to identify solely based on morphological features), cryptic species and phenotypic plasticity frequently occur. Therefore, combining traditional parasitological techniques based on morphology with molecular analyses is the most effective approach for studying parasite communities across different ecological and geographical contexts. In addition, the use of ecological indices, such as species richness, diversity or dominance, is also widely applied in studies of parasite communities, providing important ecological insights.

Parasitological investigations play a critical role in deepening our understanding of biodiversity and the complex interactions within marine environments. In order to broaden the available knowledge on parasite infection patterns in catsharks from an ecological perspective, the parasite communities infecting A. laurussonii, A. aphyodes and G. murinus from Icelandic waters were characterized and described for the first time in the present study. In addition, differences among these parasite assemblages as a function of different factors (e.g. host species, host maturity, area of capture) were assessed and parasitological descriptors and infection patterns were analysed jointly with data from Mediterranean catsharks and discussed from an ecosystemic approach.

Materials and methods

Study area and sample collection

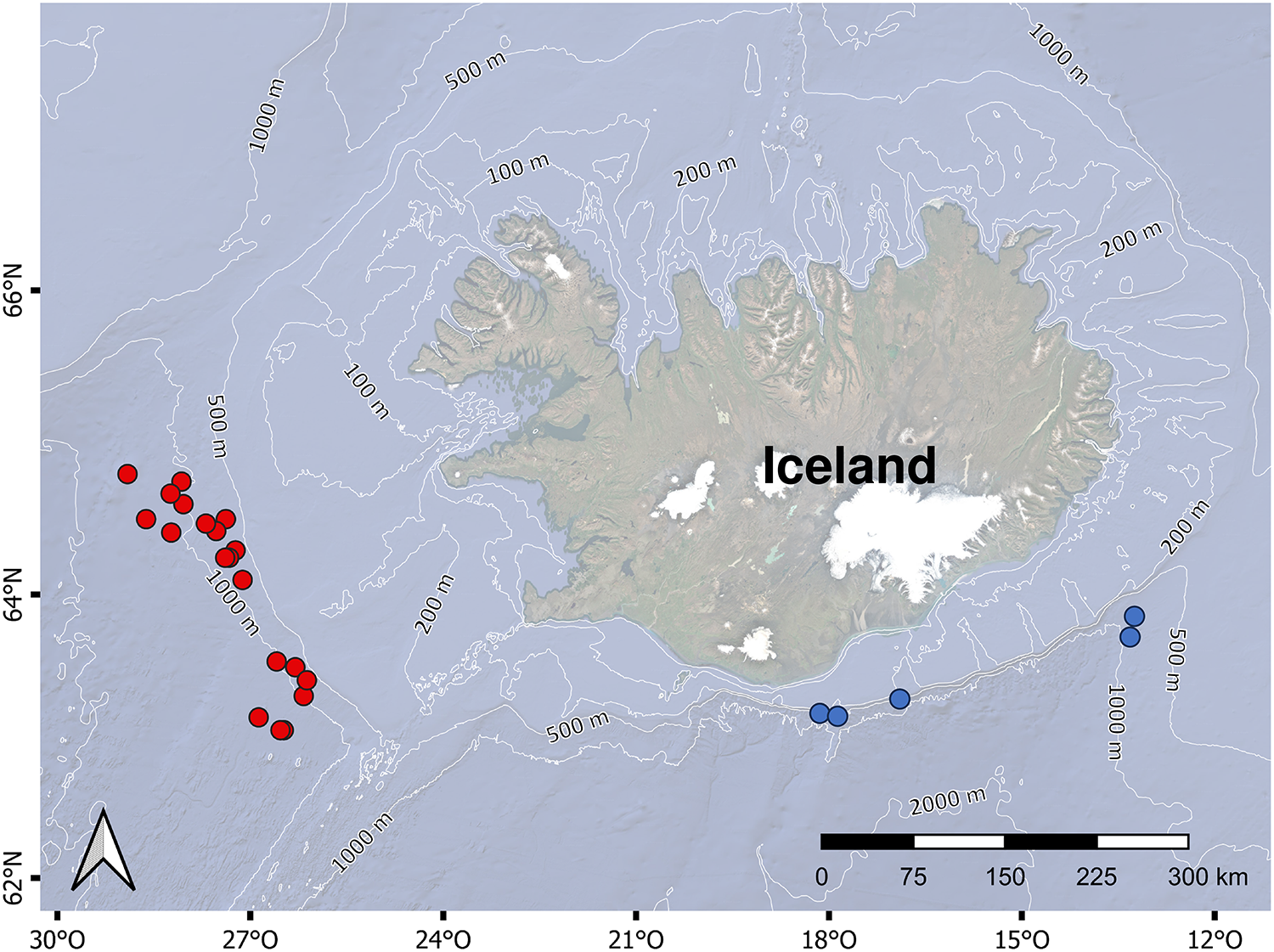

A total of 17 specimens of A. aphyodes, 14 A. laurussonii and 25 G. murinus were collected in autumn of 2023 and 2024 at depths ranging between 466 and 1322 m (Table 1) in southern and western Icelandic waters (North Atlantic Ocean). Samples were collected in the frame of the annual Icelandic Autumn Groundfish Surveys from the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute Iceland (MFRI) on board of the research vessels Árni Friðriksson and Breki. For comparative analysis, the sampling stations were divided into southern and western areas (Figure 1), and the number of individuals caught from each area is presented in Table 3.

Figure 1. Map of the study area. Dots indicate the sampling stations where the pentanchid sharks were collected. Red dots: western area; blue dots: southern area.

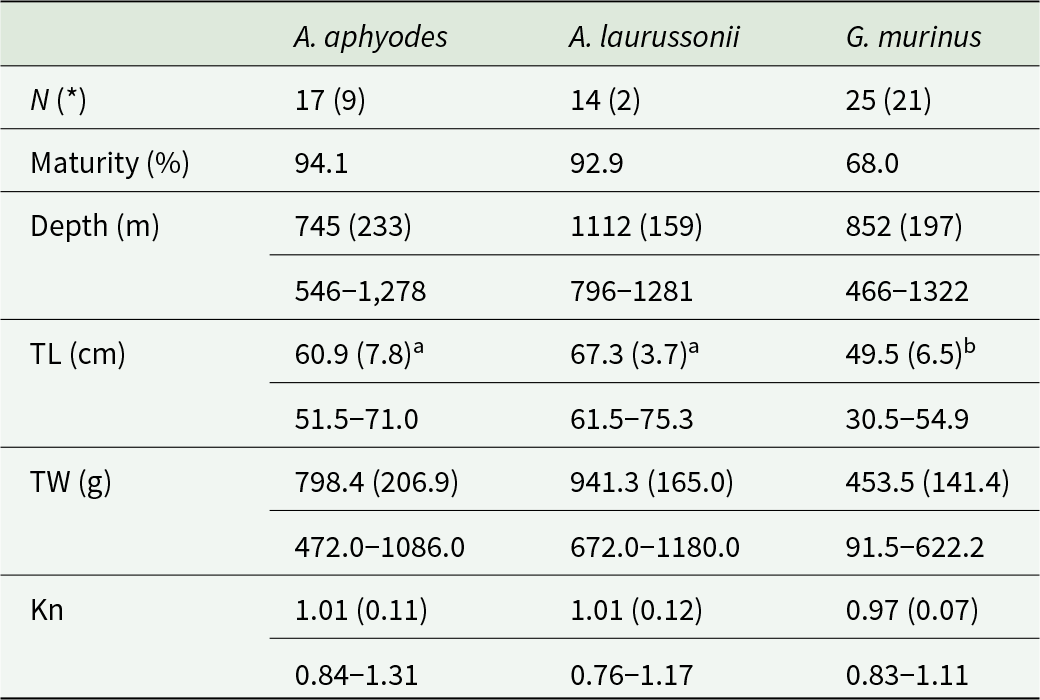

Table 1. Biometric data of Apristurus aphyodes, Apristurus laurussonii and Galeus murinus sampled in Icelandic waters

Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences among host species.

N: sample size; Maturity: Percentage of sexually mature individuals. Mean values followed by standard deviation and range values (minimum – maximum) of depth of collection, total length (TL), total weight (TW) and Le Cren relative condition index (Kn)

(*): Number of females.

Immediately upon capture, a photograph of each individual was taken and records of total length (TL, in cm), total weight (in g) and sex were obtained for each shark individual. Five spiral valves from A. aphyodes were immediately preserved in 95% EtOH and 5 and 4 spiral valves, from A. laurussonii and A. aphyodes, respectively, were preserved in 4% buffered formalin for molecular and morphological parasite identification purposes. Specimens were frozen at − 20 °C for further examination.

Dissection procedure and parasitological study

Prior to dissection, the external surfaces of each individual were examined macroscopically for ectoparasites. After removal of the abdominal organs (i.e. liver, gonads, stomach, spiral valve, spleen and pancreas), which were preserved separately for further examination, the eviscerated weight (EW) was recorded. Subsequently, the remaining organs (i.e. nostrils, gills, heart, kidneys and brain) were also removed. Maturity was inferred from the overall appearance of reproductive organs, the degree of clasper calcification in males, and the presence of egg capsules in females (Higueruelo et al., Reference Higueruelo, Robles, Constenla, Dallarés and Soler-Membrives2025).

All organs were examined for metazoan parasites under a stereomicroscope. In 9 individuals (3 A. aphyodes and 6 A. laurussonii), the liver or gonads were discarded on board for reasons beyond the authors’ control and were therefore unavailable for examination or inclusion in subsequent analyses. Mouth and abdominal cavity were washed with 0.9% saline solution to recover detached parasites potentially present in these cavities. The musculature between pectoral and caudal fins was cut into thin slices and thoroughly inspected for potential encysted endoparasites. All recovered parasites were counted and stored in 70% ethanol.

For morphological identification, platyhelminths were stained either with Delafield’s haematoxylin or iron acetocarmine, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, cleared in clove oil and permanently mounted in Canada balsam on microscope slides. Nematodes were examined as semi-permanent mounts in pure glycerine. All parasites were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level. Parasite identification was based on dichotomic keys and specialized bibliography (mainly the monographs – Kabata, Reference Kabata1979; Moravec, Reference Moravec1994, Reference Moravec2001; Palm, Reference Palm2004).

Parasites selected for molecular identification were preserved in 95% EtOH in the freezer. When possible, hologenophores (sensu Pleijel et al., Reference Pleijel, Jondelius, Norlinder, Nygren, Oxelman, Schander, Sundberg and Thollesson2008) were prepared. When specimens were too small, a morphologically identical voucher was selected. Representative voucher specimens were deposited in the parasitological collection of the Zoology unit of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Barcelona, Spain) (Accession numbers: M3–M8, C47–C51 and D9–D10).

Genomic DNA was extracted using a QIAgen DNA extraction kit or a QIAcube HT system, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 1 (mtCOI) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) for nematodes and partial nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA (28S rDNA) for the rest of parasites were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications. These were performed as described in Constenla et al. (Reference Constenla, Padrós and Palenzuela2014) or Brabec et al. (Reference Brabec, Scholz, Králová-Hromadová, Bazsalovicsová and Olson2012), respectively, adjusted for Taqman Expression mastermix. The PCR-products were analysed by capillary electrophoresis using a High-Resolution DNA kit in a Qiaxcel Advanced Instrument and viewed in the Qiaxcel ScreenGel (Qiagen) or analysed on RedGel-stained 1% TAE agarose gels. Sequencing of PCR products was performed by Genewiz-Azenta or Macrogen Inc. using either the Sanger method or capillary electrophoresis, respectively. Obtained sequences were aligned using BioEdit 7.7.1 (Hall, Reference Hall1999) checked visually for accuracy and compared to available sequences in GenBank with Mega v.11 (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar2021).

Data analysis

Parasite prevalence (P), mean abundance (MA), mean species richness (MSR) and species richness (S) were calculated for each host species, grouped by area, following Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). A 95% confidence interval for the mean abundance was calculated with the software Quantitative Parasitology (QPweb) (Reiczigel et al., Reference Reiczigel, Marozzi, Fábián and Rózsa2019). Parasite diversity was estimated by Brillouin’s index (H) and calculated with PRIMER 6 software (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Gorley and Clarke2008). The Berger-Parker dominance index (B-P dom) was calculated as the proportion of individuals belonging to the most abundant parasite species relative to the total number of parasites in each individual host. Le Cren’s relative body condition index (Kn) was calculated separately for each shark species with the formula Kn = EW/(α × TLβ), where α and β are the slope and the intercept of the weight–length relationship, of the entire dataset of sampled fish (Le Cren, Reference Le Cren1951). Parasite taxa with a prevalence <5% in all hosts were considered accidental, while parasite taxa with >25% prevalence in at least 1 host species were considered common.

Fish biometric data (TL and Kn) and parasite infection parameters were tested for normality and homoscedasticity using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. Data distribution was also plotted for visual assessment. When necessary, variables were log or square root transformed to comply with normality and homoscedasticity requirements for parametric tests.

To detect potential associations in each host species between individual fish biological data and parasitological descriptors (i.e. richness, total abundance, abundance of common parasite taxa and diversity), Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation tests (the latter when normality was not satisfied) were used. Since the Western area had the highest number of specimens, interspecific differences in parasitological descriptors, parasite abundance, and parasite prevalence were evaluated using only individuals from this area. Differences among the 3 host species were tested using ANOVA for parametric data and Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis tests for non-parametric data, with post hoc pairwise comparisons performed using TukeyHSD and Dunn’s tests (Bonferroni- or Holm-adjusted), respectively. Additionally, Fisher exact test and subsequent pairwise comparisons using the function pairwiseNominalIndependence were employed to assess differences in the prevalence of common parasites among host species.

Whenever sample size was high enough (with at least 8 individuals in each group), these potential differences were also tested between immature and mature individuals (for G. murinus) and between western and southern sampling areas (for A. aphyodes). Intraspecific differences among areas were assessed using TL as a covariate, employing generalized linear models (GLMs) or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Distributions were selected according to data type: Poisson for count data (e.g. S), binomial with a logit link function for prevalence data, and Gaussian or Gamma for parametric and non-parametric variables, respectively.

Ordination of parasite infracommunities (i.e. all parasite taxa infecting a given individual host) according to the different hosts and sampling areas was visualized with a non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) based on a Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix calculated from log + 1 transformed species abundance data. An Euler diagram was also constructed to illustrate the amount of specific or shared parasite taxa among host species. A PERMANOVA (permutational analysis of variance) was conducted using parasite abundance and prevalence data (using a Bray–Curtis and Jaccard dissimilarity matrix, respectively) to reveal potential differences in the composition and structure of parasite assemblages across hosts and areas (the latter only for A. aphyodes). PERMANOVA analyses were performed using the Adonis2 function, followed by pairwise tests, with 999 unrestricted permutations of raw data. The Indicator Value Index (IndVal) (Dufrêne and Legendre, Reference Dufrêne and Legendre1997) was then applied to identify the most representative parasite species for each host species and of each area in the case of A. aphyodes.

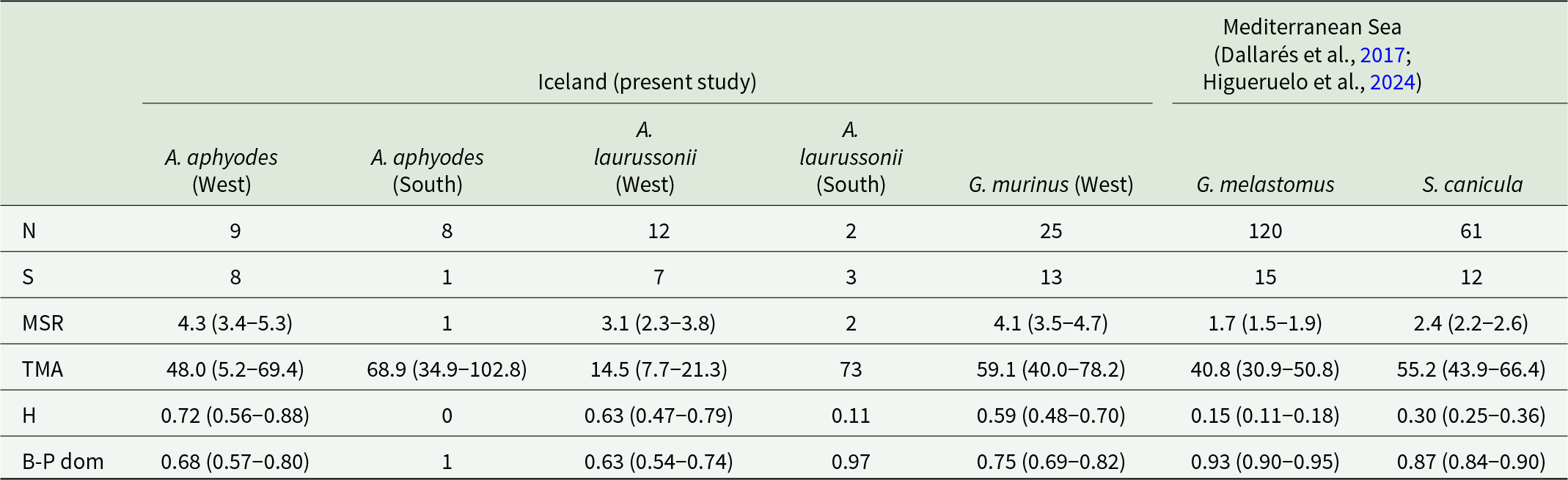

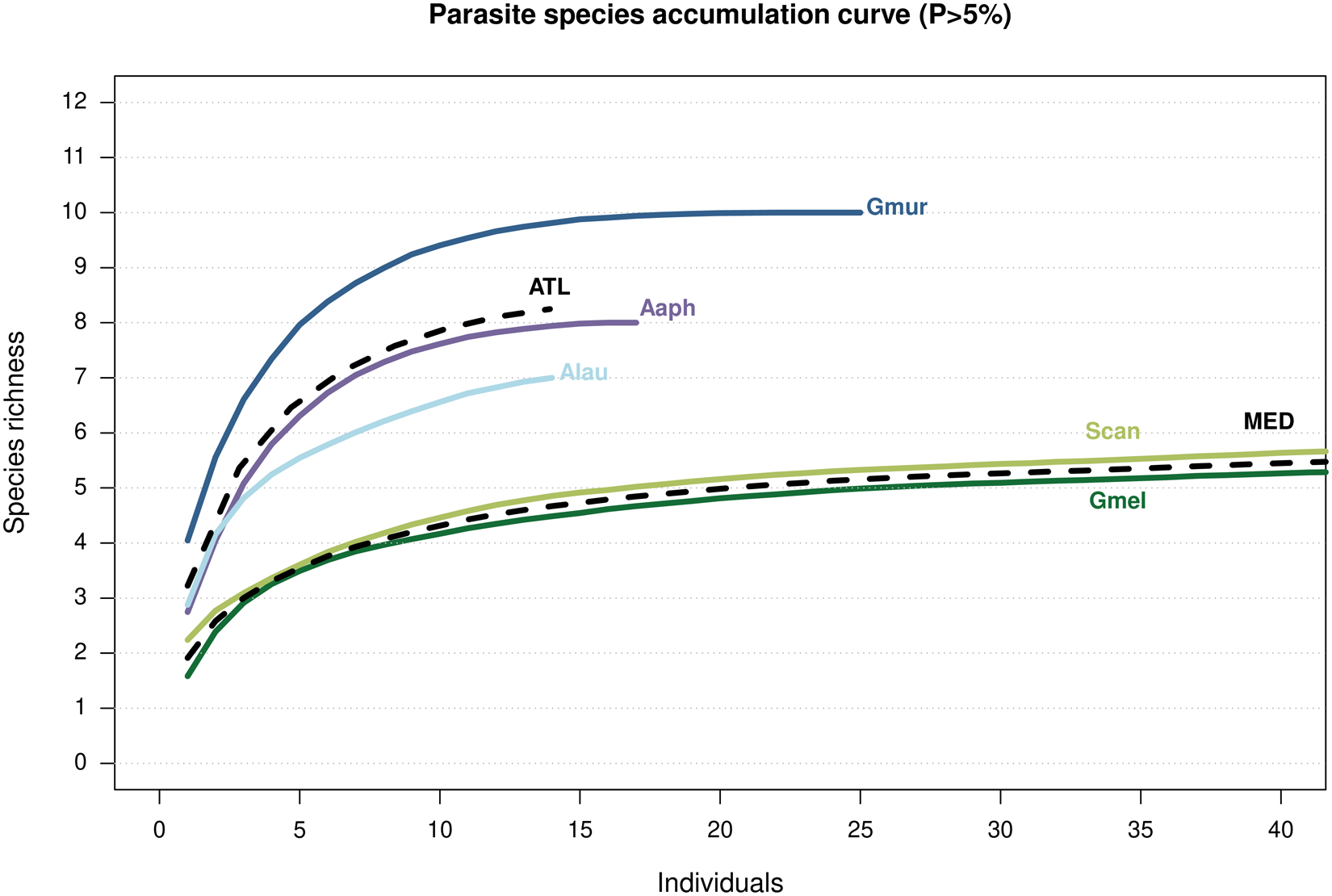

Previously published data by present authors on parasite infection parameters of the 2 most common Mediterranean catsharks (i.e. S. canicula and G. melastomus) (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017; Higueruelo et al., Reference Higueruelo, Constenla, Padrós, Sánchez-Marín, Carrassón, Soler-Membrives and Dallarés2024) were used to explore large-scale geographic patterns, something possible because parasitological protocols matched those followed in the present study. Differences on parasitological indices (i.e. MA, S, H, B-P dom and MA of each parasite phylum) between Mediterranean and Atlantic catsharks were tested with Wilcoxon and Pearson’s Chi-squared test. Species accumulation curves (SACs) were used to predict and compare total species numbers for each host and study area using the specaccum function with random method and 999 permutations. For SACs, only non-accidental parasites were considered. Statistical analyses were conducted with R version 4.4.1. Correlations were considered strong when the correlation coefficient (R) was higher than 0.65. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 56 pentanchid shark individuals were examined for parasites, 82.1% of them being sexually mature. Overall, sharks TL ranged between 30.5 and 75.3 cm, with G. murinus being significantly smaller than Apristurus species (K-W, χ2 = 33.92, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Parasite composition and parasitological descriptors of Icelandic pentanchids

A total of 2780 metazoan parasites belonging to 15 different taxa were recovered from the 3 analysed shark species, including 1 nematode, 1 cirriped, 2 copepods, 4 monogeneans, 5 cestodes and 2 digeneans (Table 2). These findings represent 27 new parasite–host records. All sharks were parasitized by at least 1 parasite, with parasite abundance ranging from 2 to 227.

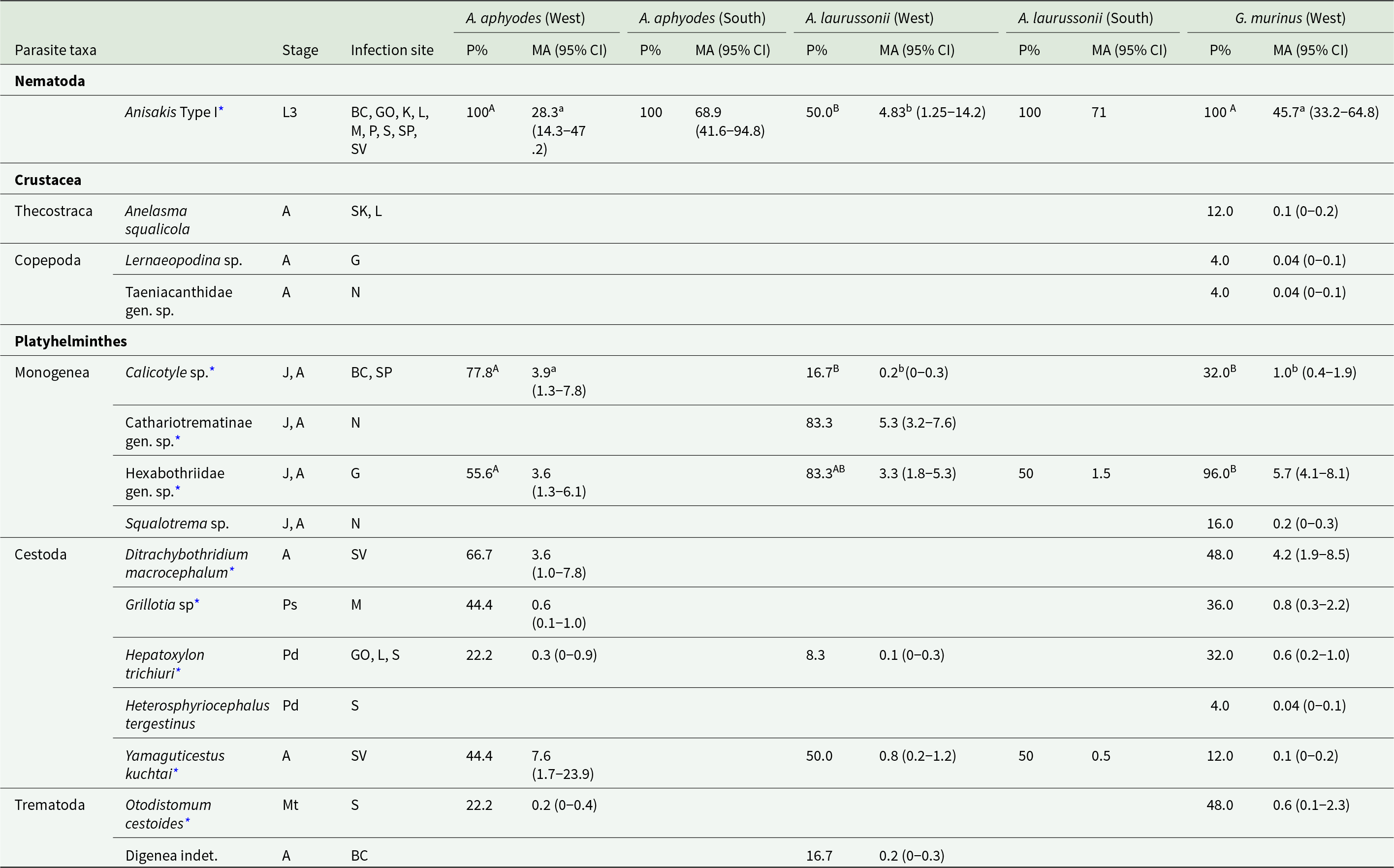

Table 2. Descriptors of parasite component populations (i.e. All parasites of a given species infecting a given host population) on the 3 pentanchid species captured off Iceland

Different superscript lowercase and capital letters show significant differences in the mean abundance and prevalence, respectively, of parasite populations among host species from West area.

* Parasites considered common in the present study (>25% prevalence in at least 1 host species).

Developmental stage, location within host, prevalence (P %) and mean abundance (MA, followed, in parentheses, by a 95% confidence interval when N > 2) are provided for the parasites found in Apristurus aphyodes, Apristurus laurussonii and Galeus murinus. For A. Aphyodes, values are also presented separately for 2 areas of capture: west and south of Iceland.

Abbreviations for infection sites within host: BC, body cavity; G, gills; GO, gonad; K, kidney; L, liver; M, muscle; N, nostrils, P, pancreas; S, stomach; SK, skin; SP, spleen and SV, spiral valve. Abbreviations for developmental stages: A, adult; J, juvenile; L, larvae; Mt, metacercaria; Pd, plerocercoid; Ps, plerocercus.

Among the recovered parasites, 5 taxa were found in all 3 analysed hosts. Anisakis Type I (sensu Berland, Reference Berland1961), found as third stage larvae encysted in several organs and displaying the highest prevalence (89.3% overall prevalence) was identified as Anisakis simplex (Rudolphi, 1809) in the 3 hosts (GenBank accession numbers: PV933132, PX101432). Shared monogeneans consisted of a yet undescribed species of Calicotyle Diesing, 1850 infecting the rectum, and a potentially new species of the family Hexabothriidae infecting the gills (GenBank accession numbers: PV972204, PV972205, PV972206), with overall prevalences of 30.4% and 71.4%, respectively. Plerocercoids of the cestode Hepatoxylon trichiuri (Holten, 1802) (GenBank accession number: PV972208) were found encysted in the gonad, liver and stomach wall with a prevalence of 19.6%, while adult specimens of Yamaguticestus kuchtai (Caira et al., Reference Caira, Pickering and Jensen2021) (GenBank accession numbers: PV972202, PV972203) were found infecting the spiral valves in 25% of examined sharks.

In A. aphyodes and G. murinus, trypanorhynch plerocerci and a metacercariae encysted in the tail musculature and stomach wall, respectively, were also commonly found and genetically identified as Grillotia adenoplusia (GenBank accession number: PV972201) and Otodistomum cestoides (Van Beneden, 1870) (GenBank accession number: PV972207).

In total, 8 parasite taxa were found in A. aphyodes, none of which were exclusive to this species (Table 2). The most prevalent and abundant parasite was Anisakis Type I. The yet undescribed species of Calicotyle (Calicotyle sp.) showed the highest prevalence and abundance in this host, with up to 13 parasites found in a single shark individual. For this host, a strong positive correlation between Berger–Parker dominance index and fish TL was found (rho = 0.91, p < 0.001) while parasite richness and Brillouin’s index were negatively associated with fish TL (rho = – 0.79 and −0.70, p < 0.002).

In A. laurussonii, the most prevalent parasites were the monogeneans Hexabothriidae gen. sp. and Cathariotrematinae gen. sp. (GenBank accession number: PV972210); the latter found infecting the nostrils and exclusively in this species. The abundance of Anisakis Type I in A. laurussonii was positively correlated with fish TL (rho = 0.71, p = 0.005) and parasite richness with fish Kn (rho = 0.67, p = 0.008).

All examined specimens of G. murinus were infected with Anisakis Type I, and all but 1 individual with Hexabothriidae gen. sp. These were the 2 most abundant parasites in this host, reaching maximum abundances of 182 and 19 parasites, respectively. Five parasite taxa were exclusive to G. murinus: the monogenean Squalotrema sp., the copepods Lernaeopodina sp. and Taeniacanthidae gen. sp., the cestode Heterosphyriocephalus tergestinus (Pintner, 1913) and the cirriped Anelasma squalicola Darwin, 1852 (GenBank accession number: PV972209). The latter species was typically found externally attached near the mouth and, interestingly, in 1 case the parasite had perforated the skin and was found in the liver. TL of G. murinus was positively correlated with parasite total abundance and with abundance of Anisakis Type I (rho = 0.65 and 0.70, p < 0.001). Concordantly, significant differences in the same 2 parasitological descriptors were observed between juvenile and adult host specimens, with higher values found in mature individuals (t-test, t = −3.73 and t = −4.06, respectively, p < 0.003 in both cases). Parasite assemblages of adult sharks also displayed a higher dominance index (Wilcoxon test, W = 30.50, p = 0.031).

Host-related and geographical patterns of parasite communities of Icelandic pentanchid sharks

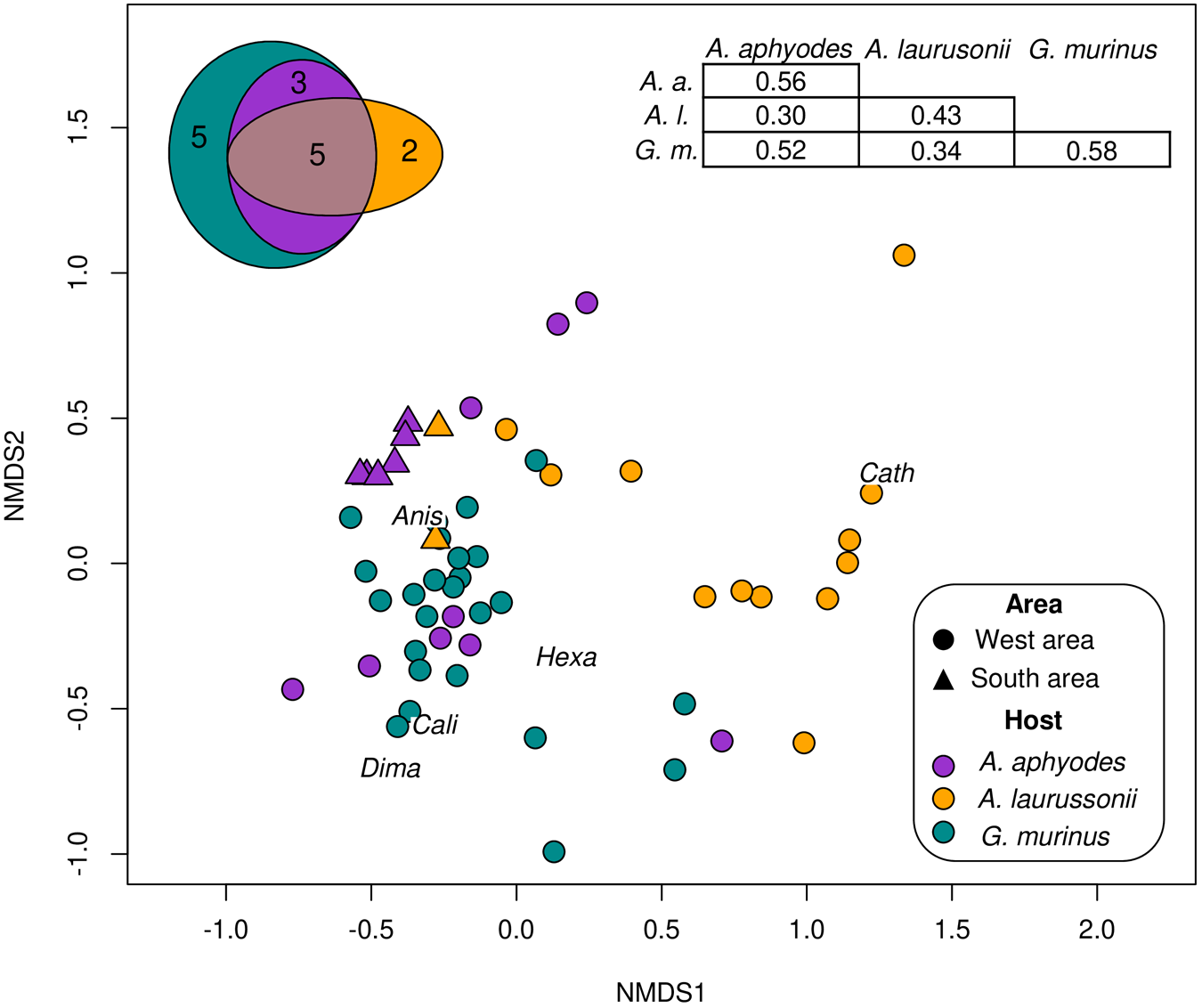

The nMDS ordination plot based on parasite abundance data (stress = 0.167) showed a grouping pattern based on host identity (Figure 2). The most similar intraspecific parasite assemblages were those of G. murinus and A. aphyodes, which showed highest mean intraspecific Bray–Curtis similarity indices. Regarding interspecific comparisons, A. aphyodes and G. murinus displayed the most similar assemblages while A. laurussonii assemblages were the most differentiated. PERMANOVA analyses revealed significant differences in both the structure (Bray–Curtis similarity index, F = 10.70, p < 0.001) and composition (Jaccard similarity index, F = 12.67, p < 0.001) of parasite communities among the 3 hosts. Subsequent pairwise comparisons confirmed that these differences were present across the 3 host species (F = 4.69–14.93, p < 0.003 in all cases). The Euler diagram (Figure 2) illustrated that out of the 15 parasite taxa identified, 7 were exclusively found in 1 host, 6 of these classified as uncommon or accidental (P < 25%). The indicator value analysis identified Cathariotrematinae gen. sp. as strongly associated with its single host A. laurussonii (IndVal = 0.71, p = 0.001) while Hexabothriidae gen. sp and D. macrocephalum were moderately associated with G. murinus, indicating that they occur more frequently and abundantly in this species (IndVal = 0.52, p = 0.003 and IndVal = 0.33, p = 0.045, respectively). No significant indicator species were detected for A. aphyodes.

Figure 2. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) illustrating the ordination of parasite assemblages according to host species and area of capture. The analysis is based on a Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix calculated from log-transformed (log (x + 1)) parasites abundance data. A Bray–Curtis similarity matrix displaying mean similarities within/among hosts (top right) and an Euler diagram depicting distribution of parasite taxa across hosts (top left) are also shown. Abbreviations for representative species according to Indicator value analyses are shown in the plot: Anis, Anisakis Type I; Cali, Calicotyle sp.; Cath, Cathariotrematinae gen. sp.; Dima, Ditrachybothridium macrocephalum; Hexa, Hexabothriidae gen. sp.

The comparison among individuals from the West area revealed that total parasite abundance was lower in A. laurussonii compared to the other 2 hosts (ANOVA, F = 8.92, p < 0.001). Similarly, the abundance and prevalence of Anisakis Type I was significantly lower in A. laurussonii (K-W, χ2 = 17.29, p < 0.001; Fisher test, p < 0.001). Additional differences in the prevalence and abundance of other parasite taxa are detailed in Table 2. No significant differences were found between pentanchid parasite communities with respect to MSR, B-P dom or H.

In the case of A. aphyodes, geographic differences in parasite assemblages were identified. The nMDS showed a separation between samples caught from the southern and western areas of Iceland (Figure 2). Parasite communities of catshark individuals from the southern region appeared more tightly clustered together (Bray–Curtis similarity index = 61%) compared to the more dispersed communities in the western region (Bray–Curtis similarity index = 36%), although the overall similarity between both areas was only slightly higher (Bray–Curtis similarity index = 39%). There were significant geographical differences on the abundance and presence of parasites according to PERMANOVA analyses (PERMANOVA, F = 9.25 and F = 22.20, respectively, p < 0.001 in both cases). The indicator value analyses associated Calicotyle sp., D. macrocephalum and Hexabothriidae gen. sp. with sharks from the western area (IndVal = 0.78, 0.67 and 0.56; p < 0.026 in all cases) and Anisakis Type I with those of the southern area (IndVal = 0.71, p = 0.030). Despite the lack of differences in total parasite abundance (p > 0.05), southern pentanchids exhibited lower MSR (GLM, p < 0.029) and H (ANCOVA, p = 0.002) and a higher B-P dom as well as Anisakis Type I abundance (ANCOVA, p < 0.001 and p = 0.03, respectively).

Large-scale geographic comparison of catshark parasite assemblages

When comparing the parasite assemblages of the most common Mediterranean and Atlantic catsharks, no significant difference in total parasite abundance was found among hosts (p > 0.05). However, when considering parasites grouped by phylum, nematodes were more abundant and prevalent in hosts from the Atlantic Ocean (Wilcoxon test, W = 7863; Chi-squared, χ2 = 43.7, respectively, p < 0.001 in both cases), while crustaceans showed a higher abundance and prevalence in those from the Mediterranean Sea (Wilcoxon test, W = 3852, p < 0.001; Chi-squared, χ2 = 10.13, p = 0.001, respectively). In the case of platyhelminths, no significant differences were observed among hosts of both regions in terms of prevalence and abundance. Differences in parasitological indices were also found to be significant, with Atlantic catsharks displaying a lower B-P dom and a higher H and MSR (Wilcoxon test, W = 2460.5, 8071 and 7711.5, respectively; p < 0.001 in all cases) (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptors of parasite component communities on the 3 pentanchid species captured off Iceland

Total richness (S), mean species richness (MSR), total mean abundance (TMA), Brillouin Diversity Index (H) and Berger–Parker Dominance Index (B-P dom) are displayed for parasite assemblages characterized in sharks captured off Iceland (Apristurus aphyodes, Apristurus laurussonii and Galeus murinus) and in the Balearic Sea (Galeus melastomus and Scyliorhinus canicula) (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017; Higueruelo et al., Reference Higueruelo, Constenla, Padrós, Sánchez-Marín, Carrassón, Soler-Membrives and Dallarés2024). Values are presented separately for the 2 areas of capture: west and south of Iceland. N = number of individuals. 95% Confidence interval is shown in brackets for MSR, TMA, H and B-P dom when N > 2.

The greater parasite richness occurring in the Atlantic Ocean compared to the Mediterranean Sea was reflected in the SACs shown in Figure 3. In general, the curves followed a typical accumulation pattern, with a steep initial increase that gradually flattened, although the curve associated with A. laurussonii did not stabilize. The 3 catshark species sampled in the Atlantic Ocean showed steeper slopes than those from the Mediterranean Sea.

Figure 3. Species accumulation curves showing accumulation of parasite species by host and region. Hosts (solid lines): Aaph, Apristurus aphyodes; Alau, Apristurus laurussonii; Gmel, Galeus melastomus; Gmur, Galeus murinus; Scan, Scyliorhinus canicula. Regions (mean values, dashed lines): ATL, Atlantic Ocean; MED, Mediterranean Sea.

Discussion

This is the first study characterising the parasite communities of deep water catsharks from North Atlantic waters. Present findings provide valuable data on the parasite assemblages of 3 of the most common Icelandic pentanchids, uncovering 27 new host–parasite records and providing baseline data for future research on parasite ecology and environmental parasitology, 2 especially growing fields in the context of global change (Palm and Mehlhorn, Reference Palm and Mehlhorn2011; Poulin, Reference Poulin2021; Sures et al., Reference Sures, Nachev, Schwelm, Grabner and Selbach2023).

The 3 pentanchid species assessed herein hosted relatively diverse and abundant parasite communities, dominated by generalist taxa. This is consistent with previous observations, in which parasite diversity decreases with depth but increases again near the sea floor (Marcogliese, Reference Marcogliese2002). The wide depth range, combined with a diverse diet, enables benthodemersal species to harbour a species-rich parasite fauna, especially compared to meso- and bathypelagic fish (Klimpel et al., Reference Klimpel, Palm, Busch, Kellermanns and Rückert2006, Reference Klimpel, Busch, Kellermanns, Kleinertz and Palm2009, Reference Klimpel, Busch, Sutton and Palm2010).

New findings concerning the only 2 previously recorded parasites in these 3 catshark species are reported. Ditrachybothridium macrocephalum had only been recorded in A. laurussonii in its plerocercoid form (Bray and Olson, Reference Bray and Olson2004). However, in the present study, mature specimens were identified infecting A. aphyodes and G. murinus, supporting the hypothesis proposed by Faliex et al. (Reference Faliex, Tyler and Euzet2000) that deepwater catsharks serve as definitive hosts for species of Ditrachybothridium Rees, 1959. The second previously reported parasite, Y. kuchtai, recently described in A. aphyodes as its type host (Caira et al., Reference Caira, Pickering and Jensen2021), was also found in A. laurussonii and Galeus murinus. Therefore, the known host range is expanded for both cestode species.

Plerocercoids found in the tail musculature of A. aphyodes and G. murinus were tentatively identified as G. adenoplusia (Pinter, 1903) based on molecular results, which indicated conspecificity with Grillotia larvae from the Balearic Sea that had been identified as G. adenoplusia based on the study of oncotaxis (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017; Isbert et al., Reference Isbert, Dallarés, Grau, Petrou, García-Ruiz, Guijarro, Jung and Catanese2023). Molecular characterization of adult specimens of this parasite, which will allow confirming unequivocally its identity, remains to be done. The definitive host of this parasite is known to be the bluntnose sixgill shark, Hexanchus griseus (Bonnaterre), a widely distributed species and capable of long-distance migrations (Ebert and Stehmann, Reference Ebert and Stehmann2013). This finding, together with the genetic structure population results of Vella and Vella (Reference Vella and Vella2017), who found shared haplotypes in H. griseus from the NE Atlantic and central Mediterranean Sea, suggests potential connectivity between the Atlantic and Mediterranean populations. Similarly, Hepatoxylon trichiuri has been reported in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (Palm, Reference Palm2004), while O. cestoides is known from the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea (Pollerspöck and Straube, Reference Pollerspöck and Straube2025). These parasites use various large elasmobranchs as definitive hosts (Pollerspöck and Straube, Reference Pollerspöck and Straube2025 and references therein). The frequent occurrence of these larval forms in Icelandic pentanchids suggests predation of these catsharks by larger sharks, a frequent phenomenon (Ebert, Reference Ebert1994; Dedman et al., Reference Dedman, Moxley, Papastamatiou, Braccini, Caselle, Chapman, Cinner, Dillon, Dulvy, Dunn, Espinoza, Harborne, Harvey, Heupel, Huveneers, Graham, Ketchum, Klinard, Kock, Lowe and Heithaus2024) that suggests intricate trophic interactions in the region that remain to be fully understood. Anelasma squalicola is a cirriped barnacle that directly extracts nutrients from its shark host, a trait that has drawn scientific interest (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Noever, Høeg, Ommundsen and Glenner2014, Reference Rees, Noever, Finucci, Schnabel, Leslie, Drewery, Theil Bergum, Dutilloy and Glenner2019; Ommundsen et al., Reference Ommundsen, Noever and Glenner2016; Sabadel et al., Reference Sabadel, Cresson, Finucci and Bennett2022). Rees et al. (Reference Rees, Noever, Finucci, Schnabel, Leslie, Drewery, Theil Bergum, Dutilloy and Glenner2019) concluded that this unique feeding strategy, described as a ‘de novo innovation’, triggered its global expansion, occurring so quickly that it didn’t have time to evolve into separate species. Molecular data from the present study, showing conspecificity with previously published sequences, further support this hypothesis by extending the known host range of A. squalicola to include G. murinus, and its geographic distribution northward into Icelandic waters. In addition, a barnacle was found inside the shark’s body cavity for the first time, where it was attached to the liver after penetrating the skin. Yano and Musick (Reference Yano and Musick2000) reported that A. squalicola is able retard the development of the reproductive organs of male sharks. Further studies monitoring this intriguing parasite and its potential effects on shark health would be welcome, especially considering its apparent rapid expansion.

The higher parasite loads, particularly of Anisakis Type I, found in mature individuals, together with the correlation observed between TL and parasite abundance, is consistent with the life cycle of this species. Indeed, Anisakis species, like many other parasites’ larval forms, accumulate throughout the lifespan of their paratenic or intermediate host (Mattiucci et al., Reference Mattiucci, Cipriani, Paoletti, Levsen and Nascetti2017), potentially becoming more dominant over time. The life cycle of anisakid nematodes involves aquatic invertebrates as first intermediate hosts and cephalopods and fishes as second or paratenic hosts (Klimpel et al., Reference Klimpel, Palm, Rückert and Piatkowski2004). Fishes, due to their longer lifespans and trophic positions, are more likely to carry Anisakis larvae compared to smaller, shorter-lived organisms such as crustaceans (Münster et al., Reference Münster, Klimpel, Fock, MacKenzie and Kuhn2015). Thus, the present findings may reflect an ontogenic shift of adult sharks towards higher-trophic-level prey items and a more diversified diet; patterns also reported in other cat sharks (Carrassón et al., Reference Carrassón, Stefanescu and Cartes1992; Van der Heever et al., Reference Van der Heever, van der Lingen, Leslie and Gibbons2020). Nonetheless, such a diet shift is usually associated with a higher parasite richness (Poulin, Reference Poulin2004; Timi and Lanfranchi, Reference Timi and Lanfranchi2013), which was not observed herein. To reliably detect dietary patterns, studies with a broader size range and a larger sample size would be necessary.

Regarding monogeneans, Cathariotrematinae gen. sp. and Squalotrema sp. were exclusively found infecting the nostrils (also referred to as the olfactory bulbs) of A. laurussonii and G. murinus, respectively. Both species belong to Cathariotrematinae, a monophyletic group of monocotylids known to parasitize shark nostrils (Bullard et al., Reference Bullard, Warren and Dutton2021) and reported herein for the first time from pentanchid sharks. Contrary to the general believe that monogeneans were highly specific taxa (Poulin, Reference Poulin1992), there is growing evidence that various monocotylid species exhibit low host specificity (Chisholm and Whittington, Reference Chisholm and Whittington1996; Kritsky et al., Reference Kritsky, Bullard, Bakenhaster, Scharer and Poulakis2017; Bullard et al., Reference Bullard, Warren and Dutton2021). This contradicts present findings, according to which closely related parasite species sampled from the same area show increased host specificity in the nostrils.

Research on specific parasite groups often leads to selective necropsy practices (e.g. cestode-focused studies specifically targeting the spiral intestine) (Caira and Healy, Reference Caira, Healy, Carrier, Musick and Heithaus2004). While this kind of studies are clearly justified from a taxonomically-based approach, they can also leave the full parasite diversity in elasmobranchs heavily underappreciated because of the dismission of other body regions than the selected ones, such as the nostrils in the case of sharks. Including these often neglected organs and tissues in routine necropsies could reveal a broader range of metazoan parasites than currently recognized, highly benefiting the knowledge on general parasite biodiversity.

Among the commonly found parasite species (P > 25%) across the 3 hosts, it is noteworthy that 8 out of 9 species were not host-specific and were present in at least 2 hosts. Among these, 6 are trophically transmitted parasites, while the remaining 2 (Hexabothriidae gen. sp. and Calicotyle sp.) are ectoparasites found in all 3 shark species. These findings support the notion that the studied sharks are sympatric species sharing similar feeding habits, having a similar trophic position and habitat preferences (Williams et al., Reference Williams, MacKenzie and McCarthy1992; Klimpel et al., Reference Klimpel, Seehagen and Palm2003). Parasites have also been recognized as effective indicators of hosts’ evolutionary history, with phylogenetically related host species typically sharing more parasite species (Poulin, Reference Poulin2010; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Bellay, Giacomini, Isaac and Lima-Junior2016). Yet, the parasite community of A. aphyodes was more similar to that of G. murinus than to its congener A. laurussonii. This difference can be mainly attributed to the high prevalence and abundance of Cathariotrematinae gen. sp. along with the overall lower parasite burden, especially Anisakis Type I, observed in A. laurussonii. While evolutionary history is a contributing factor in shaping parasite communities, it is the ongoing ecological interactions during the species’ lifespan that most directly account for the observed patterns (Poulin, Reference Poulin1995).

Concerning the potential impact of parasite infections on the health condition of the studied hosts, the only significant correlation observed with the Kn was with MSR in A. laurussonii, suggesting that parasite burden have no major negative impact on the host’s condition. Although condition indices can fluctuate due to a variety of factors, complicating the identification of clear relationships, the long-term coevolution between parasites and sharks (Hoberg and Klassen, Reference Hoberg and Klassen2002) may have resulted in an increased host tolerance to parasitism, limiting the fitness costs of infection without necessarily preventing it (Råberg, Reference Råberg2014). Consistent with the present data, some studies pointed out that healthier fish often harbour more abundant and diverse parasite communities (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Constenla, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2014; Falkenberg et al., Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Ramos and Lacerda2024).

The comparative data on A. aphyodes sampled off the west and south of Iceland revealed interesting differences in terms of parasite assemblages’ composition and structure despite the limited sample size. These differences are mainly attributed to a lower MSR and H, as well as higher dominance and abundance of Anisakis Type I in the southern sampling area. This area lies closer to the coast, with steeper topography and greater substrate heterogeneity, whereas the western sampling area is characterized by a gentler slope and more homogeneous substrate (ICES, 2022; EMODnet, 2025). The higher dominance of Anisakis in the southern area could potentially be linked to a preference of some cetaceans to productive coastal shelf areas (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Gunnlaugsson, Øien, Desportes, Víkingsson, Paxton and Bloch2005). However, various environmental factors, along with the distribution of intermediate and definitive host species, influence small-scale spatial differences in parasite communities, making it difficult to clearly determine the causes of the observed patterns with the limited data available. Iceland is influenced by a complex system of converging oceanic water masses (Logemann et al., Reference Logemann, Ólafsson, Snorrason, Valdimarsson and Marteinsdóttir2013). In this context, analysing more samples from a broader range of localities would be of great interest, as it could reveal a greater diversity of parasite species associated with these pentanchid hosts and contribute to a better understanding of the biological and ecological complexity of the region. Samples from northern Iceland would be of particular interest, since it is considered a different subarea within the Icelandic Waters ecoregion with influence of cold, low salinity Arctic waters compared to the relative warm and saline Atlantic waters influence in the southern subareas (ICES, 2022). In this sense, a preliminary study identified differences in the parasite composition of Atlantic wolffish (Anarhichas lupus L.) when comparing fish from the southern and northern areas (Elfarsson, Reference Elfarsson2023).

Accurately assessing parasite diversity requires consistent and thorough sampling practices. The standardized methodologies applied in this study enable a comprehensive approach and facilitate reliable comparisons. A large-scale geographic comparison is something often difficult to achieve, as many surveys either overlook specific host organs (e.g. nostrils or musculature) or concentrate solely on particular parasite groups, as explained above. Based on the joint analysis of present results with data obtained during the last years in the Mediterranean Sea by authors of the present study (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017; Higueruelo et al., Reference Higueruelo, Constenla, Padrós, Sánchez-Marín, Carrassón, Soler-Membrives and Dallarés2024), some differences in the parasite composition of catsharks with similar ecological characteristics have been detected when comparing both study areas.

The higher prevalence and abundance of nematodes in Atlantic catsharks is mainly attributed to Anisakis infections. In the Mediterranean Sea, A. pegreffii is the dominant species whereas A. simplex, an Arctic boreal species with a circumpolar distribution, prevails in colder waters (Mattiucci et al., Reference Mattiucci, Cipriani, Levsen, Paoletti and Nascetti2018). Despite their different distributions, both nematode species use cetaceans as definitive hosts (Mattiucci et al., Reference Mattiucci, Cipriani, Levsen, Paoletti and Nascetti2018). Although multiple biotic and abiotic factors influence the biogeography and infection dynamics of Anisakis species, the distribution and demography of their definitive hosts is a major relevant factor in explaining infection levels (Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Cunze, Kochmann and Klimpel2016). The high productivity of waters around Iceland due to the confluence of warm and cold waters, among others, makes the region an important feeding ground for cetaceans (Charles et al., Reference Charles, McGinty, Rasmussen and Bertulli2025), with 23 species recorded, of which 12 are considered regular inhabitants (Víkingsson et al., Reference Víkingsson, Pike, Valdimarsson, Schleimer, Gunnlaugsson, Silva, Elvarsson, Mikkelsen, Øien, Desportes, Bogason and Hammond2015). This likely contributes to the elevated Anisakis larval infections observed in Icelandic catsharks compared to those from the Mediterranean Sea, a pattern well documented in several teleost species (Valero et al., Reference Valero, López-Cuello, Benítez and Adroher2006; Levsen et al., Reference Levsen, Cipriani, Mattiucci, Gay, Hastie, MacKenzie, Pierce, Svanevik, Højgaard, Nascetti, González and Pascual2018; Debenedetti et al., Reference Debenedetti, Madrid, Trelis, Codes, Gil-Gómez, Sáez-Durán and Fuentes2019). In contrast, the higher prevalence and abundance of crustaceans in Mediterranean catsharks is mainly attributed to the high occurrence of the copepod Eudactylina vilelai in G. melastomus (Dallarés et al., Reference Dallarés, Padrós, Cartes, Solé and Carrassón2017), and therefore broader generalizations cannot be drawn from present results.

Regarding SACs generated in this study, the curve for A. laurussonii, the species with the smallest sample size, does not reach a plateau, suggesting that additional parasite species may remain undetected and that the observed diversity is likely underestimated. In addition, and consistently with previous observations on different fish species, present results indicate greater parasite species richness in Atlantic species than in their Mediterranean counterparts (Mattiucci et al., Reference Mattiucci, Garcia, Cipriani, Santos, Nascetti and Cimmaruta2014; Constenla et al., Reference Constenla, Montero, Padrós, Cartes, Papiol and Carrassón2015). Smaller fish sizes, reduced food consumptions, and lower biomass and abundance of animal communities in the Mediterranean have been proposed as potential factors contributing to this pattern (Constenla et al., Reference Constenla, Montero, Padrós, Cartes, Papiol and Carrassón2015 and references therein). Woolley et al. (Reference Woolley, Tittensor, Dunstan, Guillera-Arroita, Lahoz-Monfort, Wintle, Worm and O’Hara2016) found that while species richness on continental shelves and upper slopes peaks in the tropics, deep-sea species reach their highest richness at mid-to-high latitudes, particularly across the boreal Atlantic Ocean. Therefore, higher free-living species richness in these regions may lead to greater parasite richness, as more diverse host communities provide a wider range of ecological niches for parasites. This would promote host-specific adaptations and parasite speciation, resulting in more diverse parasite assemblages. Nonetheless, many biotic and abiotic factors influence the richness of parasite communities and broad generalizations must be drawn carefully.

The results presented herein highlight the potential parasite biodiversity and host–parasite relationships still to be uncovered in deepwater marine ecosystems. By shedding light on these neglected components of ecosystems, the present study contributes to the development of the growing fields of ecological and environmental parasitology. The study of parasite communities evidences the close and complex relationships occurring between parasites, their hosts and the environment, and can make a significant contribution to unravelling the intricate dynamics at play in natural systems.

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to members of the Marine Freshwater Research Institute of Iceland (MFRI) for granting the participation of BCS and AH on-board the research vessel during the Autumn Groundfish Surveys, in particular Jon Solmundsson and Klara Björg Jakobsdottir. We are also grateful to Dr Haseeb Randhawa for providing samples and Knut Albrecht (both University of Iceland) for his help processing certain shark individuals. We also thank Þórunn Sóley Björnsdóttir, Samuel Casas Casal and Heida Sigurdardottir for their valuable assistance with the molecular analyses.

Author contributions

AH conceived the study, collected and curated data, performed analyses, and wrote the original draft. SD contributed to conceptualization and methodology, coordinated the project, provided resources and supervision, and revised the manuscript. ASM contributed to study design, funding acquisition, methodology, and software, provided resources and supervision, and revised the manuscript. BCS contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and investigation, coordinated the project, provided resources and supervision, and revised the manuscript.

Financial support

This study was supported by the PhD student grant from the FI SDUR (AGAUR 2021) to AH with the support of the Secretariat of Universities and Research of the Generalitat de Catalunya and the European Social Fund, as well as (in parts) the University of Iceland Research Fund awarded to BCS (award no. 15539).

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All samples were collected in accordance with the standards of the Marine Freshwater Research Institute of Iceland (MFRI) under the auspices of the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries (Matvælaráðuneytið).