The anti-gender movement is often characterized as a transnational network of cohesive right-wing attacks on queer and feminist movements (Kuhar and Paternotte Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2017). However, right-wing actors are joined by self-identified feminists who claim to pursue anti-trans politics and resist patriarchy (Cabral Grinspan et al. Reference Cabral Grinspan, Eloit, Paternotte and Verloo2023; Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Erikainen and Vincent2020). This article investigates how two different movements—what I name anti-trans traditionalism and anti-trans feminism—manage opposite investments in patriarchy in their shared opposition to trans rights. I conduct a critical discourse analysis on anti-trans advocacy materials produced by 175 anti-trans feminist and traditionalist organizations acting in coalition. Based on this analysis, I explain how shared constructions of a trans threat are framed differently by anti-trans feminists and traditionalists and then oriented and mobilized toward diverging political ends.

What I define as anti-trans traditionalism comprises transnationally organized right-wing attacks on queer and feminist movements in service of patriarchal political agendas (Ayoub and Stoeckl Reference Ayoub and Stoeckl2024; Moreau Reference Moreau2018; Murib Reference Murib2024). Anti-trans traditionalism is linked to the larger “anti-gender” movement, which frames LGBTQ rights and gender equality as threats to religious freedom, national values, and the “traditional” family structure (Corredor Reference Corredor2019). The anti-gender movement originated in Vatican anti-feminist UN advocacy in the 1990s but has expanded in a way Paternotte (Reference Paternotte2023) likens to Frankenstein’s monster to include secular, populist, and sometimes violent actors across the globe (Korolczuk et al. Reference Korolczuk, Graff and Kantola2025). At the same time, anti-trans traditionalist framings vary depending on regional context (Edenborg Reference Edenborg2023; Nabanah et al. Reference Nabanah, Andam, Odada, Eriksson and Stevens2022), much centers around the idea that “gender ideology”—what they describe as beliefs about gender, sexuality, and family structures that challenge the naturalness of reproductive heteronormative patriarchy—threatens the “natural” sex/gender order by destabilizing what it means to be a man or a woman. Anti-trans traditionalist transphobia aligns with the dominant characterizations of transphobia as an extension of homophobia (Norton and Herek Reference Norton and Herek2013), tied to conservative ideology (Grigoropoulos Reference Grigoropoulos2024; Makwana et al. Reference Makwana, Dhont, De keersmaecker, Akhlaghi-Ghaffarokh, Masure and Roets2018; Rye et al. Reference Rye, Merritt and Straatsma2019), or following from religious beliefs (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Jordan and Anderson2019; Nagoshi et al. Reference Nagoshi, Adams, Terrell, Hill, Brzuzy and Nagoshi2008; Willoughby et al. Reference Willoughby, Hill and Gonzalez2010).

What I categorize as anti-trans feminism is a bastardization of radical feminist ideas that defines women’s oppression based on “biological” sex rather than gender and characterizes transness as violent and appropriative (Bassi and LaFleur Reference Bassi and LaFleur2022; MacKinnon Reference MacKinnon2023; Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Erikainen and Vincent2020). Because anti-trans feminism originated in radical feminist spaces, it is often described as TERFism (trans-exclusionary radical feminism). Anti-trans feminists characterize themselves as “gender critical” and claim to pursue legal recognition based on sex instead of gender. I use the language of anti-trans feminism because (1) TERF falsely implies a shared grounding in radical feminism despite what Cabral Grinspan et al. (Reference Cabral Grinspan, Eloit, Paternotte and Verloo2023) identify as three distinct varieties of feminism among these actors and (2) because the language of “gender critical” is a strategic attempt to obscure the transphobic nature of their sex-based policing (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2024). Though anti-trans feminism originates and is most mainstream in white Anglo-American contexts (McLean Reference McLean2021), it is growing transnationally (Boyacı and Boyacıoğlu Reference Boyacı and Boyacıoğlu2023; Guerrero McManus and Stone Neuhouser Reference Guerro-McManus and Neuhouser2023; Kim Reference Kim2024; Lee Reference Lee2020; Miranda 2021). Anti-trans feminism breaks from the dominant paradigm of transphobia associated with anti-trans traditionalism: anti-trans feminists are often gay (Yauger Reference Yauger2024), occupy a wide range of progressive, liberal, and leftist politics (Hines Reference Hines2020; Lamble Reference Lamble2024), and are either secular or explicitly opposed to religion (Lofton Reference Lofton2022).

Anti-trans traditionalists pursue policies that erode reproductive freedoms, same-sex protections, and women’s rights to strengthen patriarchal gender roles that they believe stem from a mandate of biological sex difference. Anti-trans feminists seek strengthened reproductive freedoms, same-sex rights, and rights for (some) women to resist the institutionalization of patriarchal gender roles. Despite these incompatibilities, anti-trans feminists and traditionalists form coalitions (Hines Reference Hines2025; House Reference House2023; Libby Reference Libby2022; Morgan Reference Morgan2023; Platero Reference Platero2023; Wuest Reference Wuest and Heaney2024). Given their contradictory ideological commitments and policy agendas, Butler (Reference Butler2021) argues it “makes no sense for ‘gender critical’ feminists to ally with reactionary powers.” This article makes “sense” of this coalition by articulating the strategic benefit of “senseless” politics.

Bassi and LaFleur (Reference Bassi and LaFleur2022, 313) find that these two movements are “rarely distinguished as movements with distinct constitutions and aims, and when distinguished are only sometimes discussed alongside one another, even though the parallels are multiple.” Approaches that collapse anti-trans feminism and traditionalism under the same right-wing umbrella often do so because they recognize (rightly) that attempts to restrict individuals on the basis of their sex share fascist practices (Kosse Reference Kosse2024; Schotten Reference Schotten2022). Treatments of anti-trans feminism and traditionalism as distinct (rightly) recognize traditionalist transphobia as a patriarchal backlash to feminism and recognize feminist transphobia as an attempt to challenge patriarchal orders. I balance these tendencies by treating anti-trans feminism and traditionalism as linked but distinct.

I find both pursue authoritarian practices of governing sex to consolidate power but govern sex in service of sex/gender orders with different relationships to patriarchy. I argue that anti-trans feminists and traditionalists discursively collaborate to author narratives about the threat of transness to generate affective energy which they then direct toward regulative regimes that share form but differ in ends. Affectively, both threat narratives rely on paradox and activate audiences by constructing a trans threat that first constructs and then destabilizes the audience’s sex-based sense of the self. Then they turn an insecure populace toward regulative regimes offering protection through policing sex. While I maintain each regime polices sex in service of different goals, they both benefit symbiotically from the disorientating effect of their contradictory alliance.

My contribution is significant in two ways. First, I build upon work in political science that identifies a tie between reactionary politics and emotion (Rico et al. Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017) by mapping out fear-based othering as a process. Breaking from characterizations of advocacy as a rational and persuasive process culminating in policy formalization (Sabatier Reference Sabatier1988), I treat advocacy discourses as politically productive in themselves. As Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2021) argues, “transphobia does not mean that a person necessarily feels personal animosity towards, or fear of, trans people. … Transphobia describes the process [emphasis my own] whereby trans people are constructed as dangerous, as those who are to-be-feared.” I account for this process by authoring a theoretical framework, which I name the Affective Orientation Threat Structure. My theory outlines how advocacy discourses produce fear as a political resource. I demonstrate that anti-trans actors disorient their audiences to generate anxiety that gains momentum through narrative paradox and contradictions that establish a circular relationship between threat and solution. My insights and theoretical framework can be adapted by scholars of a range of exclusionary politics interested in emotions as political resources.

Second, my comparative analysis reveals the flexibility of hegemony. While existing anti-gender movement scholarship explains how these politics unite diverse right-wing actors (Edenborg Reference Edenborg2023; Graff and Korolczuk Reference Graff and Korolczuk2021), my work explains how anti-trans politics bring actors with opposing—rather than merely different—ideological commitments into coalition. By demonstrating how shared tactics of authoritarian governance of sex can serve different agendas, I challenge oversimplifications of transphobia as backlash to feminism and demonstrate how anti-trans feminist projects use the affective energy generated from anti-feminist backlash to construct victimhood in a way that gives them power over other marginalized groups. This intervention challenges a tendency to relegate authoritarianism and transphobia to the realm of right-wing politics by building on scholarship (Amery Reference Amery2025a; Koyama Reference Koyama2020; Lewis and Seresin Reference Lewis and Seresin2022) that acknowledges feminism’s historical and contemporary adoption of hegemonic agendas. I demonstrate that anti-trans feminists can work against patriarchy while working toward other sex-based regimes of domination. Taken together, these contributions delink the authoritarian practices of anti-trans feminists and traditionalists from any singular ideology or project and identify how shared affective governing practices can enact different hegemonic regimes.

To make my argument, I draw from scholarship about transphobia as affective governance to ground my treatment of anti-trans discourses as a political end in themselves. I follow by describing my grounded theory approach to identifying how anti-trans feminist and traditionalist discourses enact different sex/gender orders. Next, I describe the theoretical framework—Affective Orientation Threat Structure—I develop to explain the process of this affective governance. Then, I apply my theoretical framework to the discourse about the threat transness poses to women/womanhood. I conclude by contextualizing my findings and their relevance to how we understand cisnormativity’s relationship to sex/gender order and anti-gender backlash more broadly.

Affective Governance of Anti-Trans Politics

Foundational scholarship on transnational advocacy networks (TANs) assumes TANs form around shared values and use advocacy processes to persuade audiences to formalize shared policy goals (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1999). Critical scholarship on anti-gender politics makes sense of unlikely coalitions by challenging three assumptions: (1) that coalitions depend on shared values; (2) that advocacy depends on rational persuasion; and (3) that this process culminates in policy. I build on this scholarship to account for how anti-trans coalitions make use of contradictions to advance their goals of affective governance.

First, breaking from the notion that coalitions are united around shared values, Hajer (Reference Hajer, Fischer and Forester1993, 47) argues discourse coalitions overcome incommensurate commitments through storylines “in which elements of the various discourses are combined into a more or less coherent whole and the discursive complexity is concealed.” Emphasizing shared storylines obscures differences and enables “the plasticity of anti-gender politics” (Edenborg Reference Edenborg2023, 176) by masking points of tension to bring diverse actors into a coalition Corrêa describes as a many-headed hydra (Corrêa et al. Reference Corrêa, Paternotte and Claire2023). Mayer and Sauer (Reference Mayer, Sauer, Kuhar and Paternotte2017) describe “gender ideology” as an “empty signifier” in this context because it connects various concerns through the notion of an existential threat to the social fabric. I argue that since gender organizes a wide variety of institutions, identities, and practices, advocacy against “gender” absorbs a wide range of symbols and can usher in diverse outcomes through shared language.

Second, scholarship on disinformation and affect challenges the assumption that advocacy must be rationally persuasive to be impactful. Building on this insight, I argue that the incoherence produced by patchwork narratives is an asset rather than an obstacle to anti-trans projects because the affective disorientation produced by paradox drives audiences of these narratives toward measures that promise security. Per Butler’s analysis of the strategic use of incoherence: “If the head spins, it is supposed to” (Reference Butler2024, 79). Rather than persuasion, anti-trans narratives seek to incite panic via disinformation (Billard Reference Billard2023). In these moral panics about gender, trans people function as political specters or “phantasms” (Butler Reference Butler2024) rather than subjects since transness is often scapegoated and policed via practices that often have other primary focuses. Franklin (Reference Franklin2022, 134S) argues that cultural debates around gender binarism function as “gender proxy wars” where establishing an “essential truth of binary gender” serves as a proxy for establishing other “truths” about race, religion, sexuality, and other contested aspects of identity. In his analysis of anti-trans policies, Currah (Reference Currah2022) argues that policing the sex of trans people creates mechanisms to police sex writ large:

The legitimacy of the majority’s sex classification, which most have probably never questioned, is made possible by erecting obstacles to other’s requests for reclassification; the vulnerability of ‘transgender’ individuals subtends the perceived invulnerability of everyone else on that score. (12)

In this understanding, anti-trans politics work to empower cisnormativity just as they function to disempower transness.

Third, though anti-trans and traditionalists both claim to be “anti-gender” and pursue a shared agenda of sex-based rights, their larger projects are not subsumed by these policy agendas. Instead, these policies are forerunners to larger sex/gender orders. As Gill-Peterson (Reference Gill-Peterson2021) argues, cisness fortifies the state’s regulatory capacity: “Cisness empowers the state to strengthen its authoritarian tendencies, since the stripping of civil rights and any access to public welfare is at stake here.” Regulating individual bodies provides the state with a way of regulating the body politic. Anti-trans politics order sex and gender by first, insisting that sex is a site through which our political and social orders have meaning, and second, explaining what sex means for that order. Butler (Reference Butler2024, 18) argues that when actors identify as anti-gender, “They are not opposed to gender—they have a precise gender order in mind that they want to impose upon the world.” Pursuing sex-based rights has an ordering function because it constructs sex and sex difference as biological facts through the fiction of cisness. Heaney (Reference Heaney and Heaney2024) theorizes cisness as “the concept that recasts sex as a biological fact following political challenges to the sanctity of sex as an ordained social order” (1) and argues, “cisness is the idea that those identified as girls at birth are naturally inducted into the social expectation that sexual difference sets for the feminine and likewise for boys with the masculine” (10). In problematizing the objective sex that “sex-based rights” depend on, Heaney identifies cisnormativity as the institutionalized ascription of meaning to sex difference and the sex/gender order produced through that ascription.

From these insights, I posit that the discourses around sex-based rights (rather than the rights themselves) do the work of “recasting” sex as a biological fact by interpreting what is meaningful about sex as a grounds for recognition. As Hines (Reference Hines2025) argues, sex-based rights have “imaginary foundations” (704) as a legal concept. They take meaning through their framing. In pursuing sex-based rights, both discourses work toward cisnormative sex/gender orders by insisting that sex difference is a meaningful site of recognition. However, where scholars like Heaney (Reference Heaney and Heaney2024) and Butler (Reference Butler2024) use a singular form of the word “order” to describe the arrangement produced by cisnormative regulation, I posit that cisnormativity can order the relationship between sex and gender to multiple ends. To advance this claim, I took a grounded theory approach and analyzed anti-trans discourses with the goals of identifying how anti-trans traditionalist and feminist movements inscribe meaning through interpretations of sex-based rights and what sex/gender orders anti-trans feminist and traditionalist discourses, respectively enact through this inscription.

Methods

Grounded theory approaches generate theories inductively from the collection and analysis of evidence (White and Cooper Reference White, Cooper, White and Cooper2022). Because of my interest in how shared anti-trans language develops and diverges, I started my process of data collection by identifying transnational networks of anti-trans organizations stemming from central anti-trans feminist and traditionalist nodes.

Network Identification

For anti-trans feminists, I began with a network of organizations called Women’s Declaration International (WDI) (formerly Women’s Human Rights Campaign), which is a UK-based network with 50 chapters in other countries. Members of WDI are “key players of anti-trans feminism at a global scale” (Cabral Grinspan et al. Reference Cabral Grinspan, Eloit, Paternotte and Verloo2023, 3). They host transnational conferences and have authored the “Declaration of Sex-Based Rights,” an anti-trans rearticulation of the UN’s CEDAW. To identify anti-trans feminist organizations within this network, I identified active signatory organizations to WDI’s declaration and removed groups that did not discuss trans or LGB rights. Then, I expanded my set via a snowball-like sampling process where I included organizations I observed core groups collaborating with through co-sponsoring events or press releases, naming as partner organizations, or linking to as resources. This process yielded a list of 86 anti-trans feminist organizations.

For anti-trans traditionalists, I began with the network of organizations that participate in the International Organization of the Family’s annual conference, named the World Congress of Families (WCF). The WCF is founded and largely funded by religious conservatives in Russia and the United States and is broadly characterized as central influential actor within the anti-gender movement (Korolczuk et al. Reference Korolczuk, Graff and Kantola2025; Moss Reference Moss2025). I identified anti-trans traditionalist organizations in this network by starting with Ayoub and Stoeckl’s (Reference Ayoub and Stoeckl2023) list of 58 core participants within the WCF and then identifying anti-trans groups that core participants collaborate with. This yielded a set of 86 anti-trans traditionalist organizations. Many organizations had eclectic policy and ideological commitments that did not fit neatly into the ideal types for anti-trans feminism. I made my classificatory choice based on whether organizations positioned their goals as challenging or endorsing a sex/gender order with gender roles rooted in subordination and complementarity and gendered relations organized through a reproductive family structure. I classified three organizations that did not make claims about the sex/gender order as neutral. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of organizations.

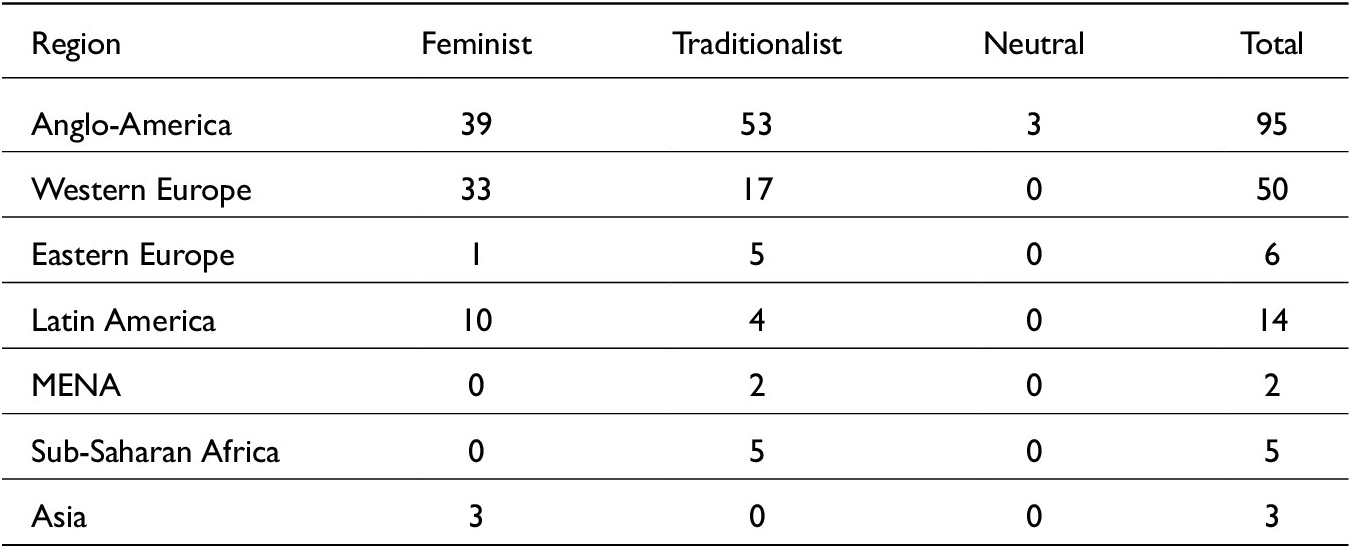

My organizations range in size, formality, and funding. Table 1 summarizes the geographic breakdown of these organizations. The majority of these organizations are concentrated in the Global North. This geographical concentration does not necessarily reflect the global distribution of anti-trans organizations but likely skews toward the Global North because the central network nodes (WDI and the WCF) are based there. The transnational breadth of my dataset remedies a flaw Ojeda et al. (Reference Ojeda, Holzberg and Holvikivi2024) identify in approaches to anti-gender scholarship that either characterize anti-gender movements as Western and center on the Global North or study anti-gender politics in regional contexts such as Latin America or Africa without connecting them to transnational trends.

Table 1. Geographic distribution of organizations

Text Collection

After identifying organizations, I collected documents where these groups discuss anti-trans ideas to build a catalogue of anti-trans talking points. Temporally, documents range between 2015 and 2023 (when I commenced collection). I begin with 2015 because it slightly precedes the mainstreaming of anti-trans feminism in the United Kingdom (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2024) and coincides with increased anti-trans visibility in the United States surrounding bathroom bills (Murib Reference Murib2020). I focused my selection of documents on those where organizations either constructed their own identities (such as mission statements, about us pages, and FAQs) or constructed the threat of transness (such as blog posts, press releases, policy reports, and resource guides). I identified documents in the latter category through keyword searches for “trans*,” “sex-based rights,” “LGBT,” “drag,” and “gender ideology.” When websites had more than 10 anti-trans documents, I stopped collecting once I reached theoretical saturation of ideas. For documents not in English, I procured translation by native speakers through WordPoint. This process yielded 1016 documents: 351 documents from anti-trans feminist organizations, 640 from anti-trans traditionalist organizations, and 25 from neutral organizations.

Analysis

I analyzed these anti-trans texts through an iterative open-ended coding process that focused on the ordering effects of anti-trans language itself. My focus on language and narrative as politically meaningful is informed by Ahmed’s (Reference Ahmed2021) insistence, “We learn about terms from what they are used to do; a story is being told in certain terms for a reason.” Specifically, I utilized critical discourse analysis which “studies the way social power abuse, dominance, and inequality are enacted, reproduced and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context” (van Dijk Reference Dijk2005, 352). Critical discourse analysis allows us to identify how the stories that constitute anti-trans discourses function to restructure political order. As Murib (Reference Murib2024, 3) argues, “narratives of sex as biological and essential are exactly that: stories told about bodies that reify gender stereotypes in service of maintaining power.” By attending to how language enacts power, critical discourse analysis provides a lens for identifying the specific way narratives interpret what is meaningful about sex difference to form the basis of cisnormativity, how these cisnormative interpretations are interpellated among audiences to enact cisnormative governance, and the ordering produced by that governance.

Before coding, I identified key thematic areas to structure my analysis and ground my coding schema. These thematic areas focus on how organizations situate themselves and their audiences, construct the threat of transness, and offer solutions to that threat. During the first round of coding, I iteratively built out my coding schema by developing subcodes for each thematic area based on my observations while coding. During the second round, I adjusted and recoded based on the finalized schema generated in the first round. After coding, I developed my theoretical framework by analyzing similarities and differences among anti-trans feminists and traditionalists’ discourses and mapping their claims in relation to the desired sex/gender orders.

Theoretical Framework

During analysis, I observed both anti-trans feminists and traditionalists argue that transness threatens women by disrupting the tie between sex and women’s roles and offer sex-based rights as a way to defend those ties. However, anti-trans feminists and traditionalists frame the stakes of this disruption differently. Anti-trans traditionalists argue transness destabilizes a patriarchal sex/gender order where gender roles, family structures, and the national organization of power all derive from the hierarchical reproductive roles “ordained” by sex difference. Anti-trans feminists argue that transness naturalizes this patriarchal order through a concept of “gender” that treats patriarchy’s hierarchical and oppositional roles for men and women as essential rather than imposed. Based on these different commitments to protecting and challenging subordinated roles for women, anti-trans feminists and traditionalists pursue sex-based rights with the intention of strengthening cisnormative regulation to different ordering ends.

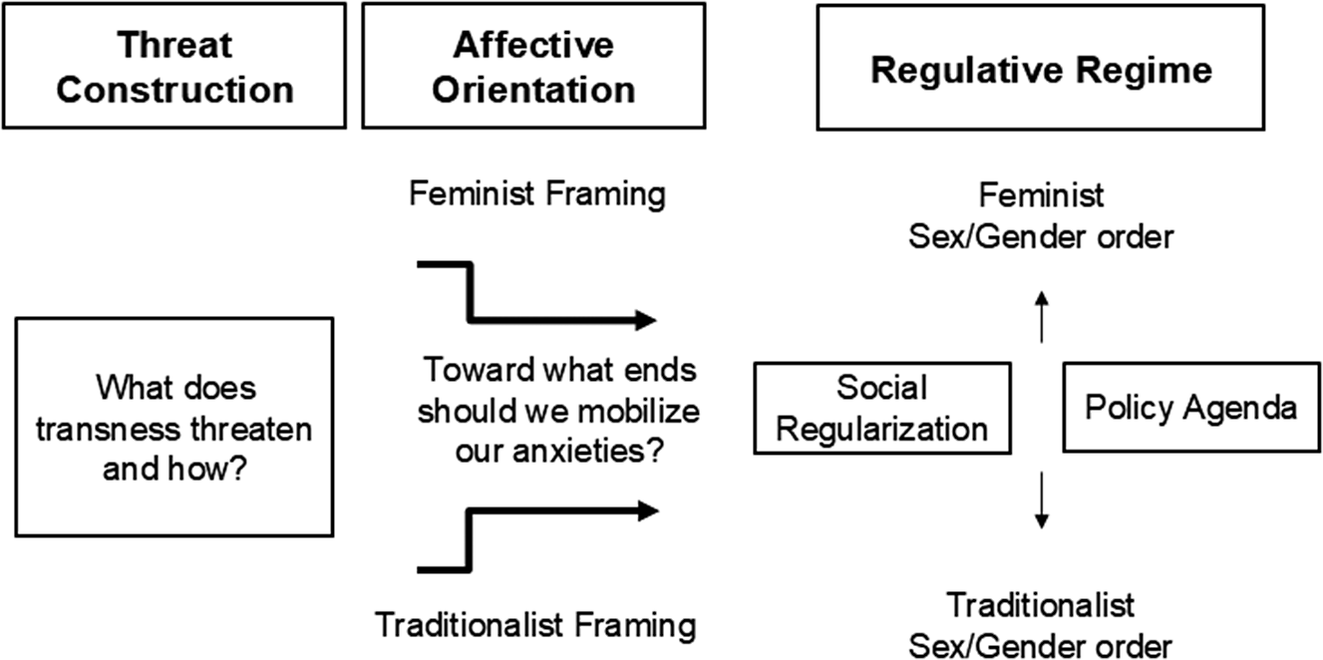

I have designed my theoretical framework—the Affective Orientation Threat Structure—to describe how shared narratives of sex-based rights generate the affective momentum that fuels varying cisnormative regulation. Hemmings (Reference Hemmings2005, 552) describes affect as what “connects us to others and provides the individual with a way of narrating their own inner life (likes, dislikes, desires and revulsions) to themselves and others.” Figure 1 outlines this process within my Affective Orientation Threat Structure. In the first stage of this process—threat construction—anti-trans discourses dialectically construct the threat of transness to construct the cis self as threatened. In the second stage—affective orientation—actors contextualize fear generated by threat through framing that directs audiences toward an ameliorative response. In the final stage, anti-trans actors engage their audiences in regulation that reorders sex by pairing social regularization and formal policies that police sex difference to “secure” cisness.

Figure 1. Affective orientation threat structure.

This process starts with shared threat construction, where anti-trans actors identify a threat in terms of what it poses to a specific group or symbol. Threat construction is accomplished through identity propaganda—“strategic narratives that target and exploit identity-based differences to maintain existing hegemonic social orders” (Reddi et al. Reference Reddi, Kuo and Kreiss2023, 2202). Both threat constructions generate similar affective attachments through threat-based identity construction that presents cisness as an axis to construct identity along. Though anti-trans narratives do not name their audiences as cis (some even describe “cis” as derogatory), they construct their audience through forming an attachment to cisness by insisting the trans threat to sex difference is a threat to the audience’s essential self. Constructing cisness oppositionally to transness allows anti-trans actors to obscure the work they do to enforce cisness. Because threat construction creates oppositional and dialectical relations between the trans threat and the cis victim, it is a “constitutive rhetorics” (Charland Reference Charland1987). Identity construction—especially when relational—is an affective process because as Nay (Reference Nay2019, 68) argues, “emotions direct the ways in which the self is placed in relation to the ‘other’.”

Policy prescriptions do not follow naturally from threat construction. Instead, fear needs contextualization to become actionable. Affective orientation contextualizes fear by identifying it as an emotion warranting a particular response and then directing audiences toward that response. In Ahmed’s reading, fear as an emotion is well suited to the flexible orientation process because fear “does not reside positively in a particular object or sign. It is this lack of residence that allows fear to slide across signs and between bodies” (Reference Ahmed2014; 64). Affective orientation does this work of sliding—it guides fear toward an object. I use the language of “affective orientation” because attachments through these emotions locate and orient individuals in relationship to themselves, others, and the structures that manage these differences. In the orienting portion of threat narratives, the anxious populus provoked by the disruption of the gender binary and the resulting “gender panic” (Westbrook and Schilt Reference Westbrook and Schilt2014) is directed toward processes of formal governance and regularization that promise to quell that panic by restoring sex-based identity. Where threat construction alerts an audience that the trans other threatens their cisness, affective orientation directs the audience toward cisnormativity for protection. However, differences in how anti-trans feminists and traditionalists respectively frame the threat to transness and what cisnormativity promises allow each camp to direct affective momentum toward different cisnormative regimes.

Once directed, anti-trans narratives mobilize affective momentum via regulative regimes. These regimes enact sex/gender orders by marrying formal governance through policy and social governance through regularizing cisnormativity in line with the Foucauldian articulation of the relationship between law and norms. Laws formally forbid deviance, and norms regularize desired behavior by constituting “standards against which people are measured incessantly” (Kelly Reference Kelly2019, 9). In this arrangement, the state asserts control both by legally punishing transness and socially enforcing disciplinary practices that regularize bodies through (cis)normative standards. Amery (Reference Amery2025a, 1245) argues sex-based regulation is biopolitical because one needs “the ability to know the differences between men and women in order to govern them.” In the section that follows, I apply my Affective Orientation Threat Structure to anti-trans discourses about the threat that transness and “gender ideology” pose to women and womanhood. This is not the only shared narrative about the trans threat I observed. Many scholars (Gill-Peterson Reference Gill-Peterson2024; Hines Reference Hines2020; Lamble Reference Lamble2025) describe the predominant narrative that trans women threaten cis women through violence. I chose to analyze narratives about the ideological threat transness poses to the category of womanhood to demonstrate the fundamental link between sex and identity that grounds cisnormative sex/gender orders.

Anti-Trans Threat Narrative: Trans Threat to Womanhood

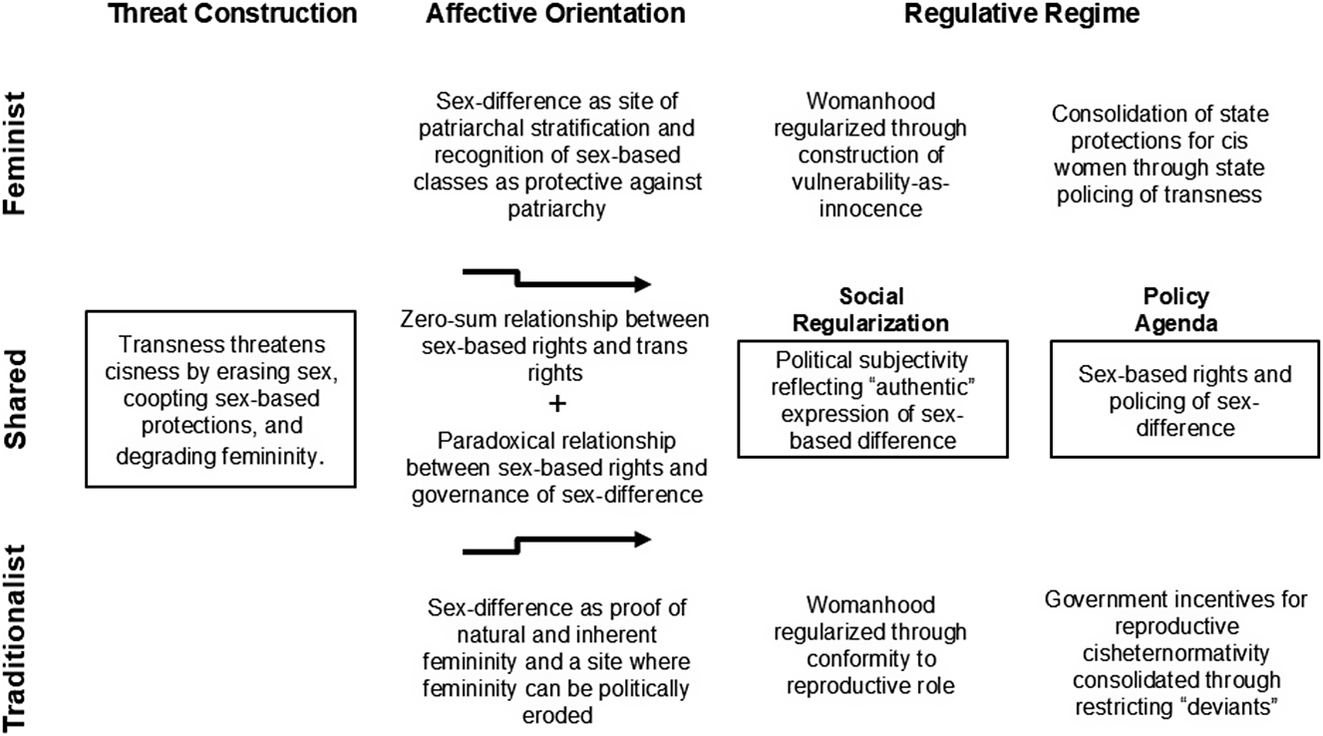

Narratives about the existential threat transness poses to women emerged first in radical anti-trans feminist circles (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2024). Though anti-trans traditionalists are often anti-feminist, they have adopted and adapted parts of this narrative. Both groups construct threat around similar core ideas and stoke affective anxiety around a zero-sum threat to womanhood but use different framings to orient this affective energy toward different regulative regimes. Figure 2 applies my Affective Orientation Threat Structure framework to the diverging articulations of the trans threat to womanhood.

Figure 2. Trans threat to womanhood.

Threat Construction

Both narratives construct the trans threat to womanhood by arguing that transness destabilizes cis womanhood along three axes: erasure, cooption, and degradation. Erasure-based narratives insist that inclusive language erases the “material” tie between sex and womanhood. Referencing the US Democrats’ pro-trans policies, Eagle Forum (T-US) writes, “the only ones who truly celebrate women are conservatives. Liberals in Congress have pushed forward policies that erase women.” This zero-sum framing uses the language of erasure to pit the celebration of women against policies that protect trans rights. Similarly, Declaration for Biological Reality (F-UK) writes, “As a direct consequence of gender identity ideology, we have witnessed an erosion of the reality of what it means to be a woman.” The casting of transness as “ideology” in tension with cisness/sex as “reality” and the language of “erosion” implies a zero-sum relationship between these two conceptions.

Shared threat constructions rooted in cooption claim that transness allows men to appropriate womanhood in order to hollow out the protections and opportunities cis women need because of their sex difference. The Association of Concerned Mothers (T-Nigeria) writes, “Girls and women have been extended special protections… not because they identity as ‘girls’ or ‘women’ but due to the biological reality of being female and the inherent differences between the sexes.” Similarly, Voorzij (F-Netherlands) claims, “special protection is offered to women based on their sex … that protection clashes in some respects with the wishes of trans identified men.” The language of “special protection” for women and alludes to a zero-sum tension with the language of “clashes.” Shared language of “special protection” emphasizes sex difference (and, therefore, cisness) as creating unique problems for women that only sex-based rights and recognition can redress.

Both camps construct transness as a threat to women by arguing that any attempt to define women without biological sex necessarily relies on defining women, instead, through a fabricated concept of gender. GARRA (F-Brazil) writes, “transactivism that prevails today is based on strengthening gender stereotypes” and Ethics and Public Policy Center (T-US) accuses trans femininity of “perpetuating a male stereotype of what a woman should be.” The shared language of stereotype claims trans femininity detaches womanhood from whatever meaning anti-trans actors believe cisness inscribes it with and replaces it with an externally imposed paradigm of femininity that degrades women.

Affective Orientation

Anti-trans feminist and traditionalist threat constructions share “affective resonance” (Libby Reference Libby2022) in their shared strategy of stoking a scarcity-based anxiety through a zero-sum framing of the relationship between trans rights/transness and threats to sex-based rights/womanhood. Through language such as For Women Scotland’s (F-Scotland) claim, “we just don’t agree that our rights need to be railroaded over” and C-FAM’s (T-US) claim, “Although activists claim they just want to protect the rights of trans-identifying people, their movement actually seeks to erase biological sex altogether,” both anti-trans narratives affectively orient fear stoked by a zero-sum threat toward responses intended to protect cisness by securing sex-based rights.

However, differences in how anti-trans feminists and traditionalists ascribe meaning to sex difference create diverging understandings about what is at stake in the erosion of cisness and the sex/gender order it foregrounds. In anti-trans feminist framings, women’s sex difference (and specifically their reproductive capacity) matters because it makes women vulnerable to patriarchal exploitation, but anti-trans feminists refuse the traditionalist idea that reproductive capacity creates a naturally subordinated caretaking role for women. In contrast, anti-trans traditionalists frame women’s bodies (and reproductive capacity) as the blueprint for a sociopolitical role based around femininity as motherhood. Anti-trans feminists contextualize the patriarchal sex/gender order as produced by a legacy of institutionalizing sex-based exploitation, while anti-trans traditionalists attempt to depoliticize the difference between women and men by framing gender roles as “natural” rather than structurally imposed.

Anti-trans feminists frame what is at stake in the trans threat to sex difference by arguing that erasing sex difference alienates women from the basis of their oppression. For example, FRIA (F-Argentina) frames erasure by arguing, “Because we are still an oppressed group and our demands are still far from being achieved, we reject all attempts to make women invisible… as a historically invisible group, defined by men as what is not man, we refuse to continue to be defined negatively and in opposition to other identities.” Affectively, this emphasis on continued oppression primes women to construct their identities as victims of historical marginalizations. Similarly, anti-trans feminists frame the threat of stereotypes as an unwelcome imposition of femininity on women. For example, Lesbian Resistance (F-New Zealand) writes, “Girls who don’t conform to stereotypical ‘femininity’ must not be considered to have a ‘male identity.”’ In this framing, “femininity” itself is a stereotype that gender ideology demands women perform via pressure to “conform” to a patriarchal interpretation of sex difference where failure to conform leads to denial of womanhood. Affectively, this framing of femininity as institutionalizing inequality primes women to construct their own identity and recognition as women as something that can be taken if they do not conform to subordination. As a result, attempts to deny the womanhood of trans women are rearticulated, not as acts of violence, but as protective measures that prevent the denial of their own cis womanhood.

Because anti-trans feminists emphasize sex difference as a site where inequality is institutionalized and femininity as an institution that maintains that inequality, these framings converge around a contradictory (and, therefore, anxiety-producing) characterization of womanhood as a tactical political position. Anti-trans feminists maintain the radical feminist idea that patriarchy stratifies populations along sex difference by institutionalizing the exploitation of sex-based vulnerability (Firestone Reference Shulamith1970) while also advocating for measures (like sex-based rights) that institutionalize womanhood through the mechanisms of sex-based differentiation that they attribute subordination to. In these narratives, sexed (rather than androgynous) citizenship is both a bastion against and a necessary condition for a patriarchal sex/gender order. For example, FRIA (F-Argentina) writes:

The historical oppression of women has a material basis, which is the use of our sexuality, our reproductive capacity and our ability to care for the benefit of men. For this reason, we constitute opposite sexual classes. Women are not simply different from men, but we find ourselves in a situation of oppression by them. This is why being a woman is not a mere identity option but a collective political subject. We reject any attempt to erase women as political subjects and to conceal their material basis: our sexualized body.

The statement suggests the stratification of men and women along the lines of sex difference creates “opposite sexual classes” where institutionalizing sex difference leads to a “situation of oppression.” However, even as inequality is framed as socially imposed, woman is defined as a political subject with a “material basis.” This articulation collapses sex and the sociopolitical processes that produce a “sexualized body.” This incoherence creates a muddled argument where the state must recognize women as a materially distinct sex-based class so women can organize against their marginalization and where the marginalization of women comes from the institutionalized interpretations of sex difference as meaningful enough to constitute women as a distinct class. While anti-trans feminists may claim that sex-based recognition provides a subject-position from which to organize against patriarchy, it further stratifies populations into sex-based classes. These contradicting commitments direct audiences toward a circular paradox of embracing sex-based rights and refusing sex-based differentiation.

Anti-trans traditionalists endorse the patriarchal sex/gender order that anti-trans feminists oppose and thus diverge in their framing of what is at stake in the trans threat to sex difference. Where anti-trans feminists argue sex difference matters because it makes women vulnerable to institutional harm, anti-trans traditionalists construct sex difference as meaningful through a complementarity-based frame. Complementarity is a theological argument that men and women—in God’s design—are inherently different in a way that complete one another and therefore they are equal in dignity but not in purpose (Case Reference Case2016). Where anti-trans feminists pursue equality by rejecting (however superficially) sex-based stratification, anti-trans traditionalists pursue equality dependent on sex-based difference. For example, Christian Concern (T-US) writes, “God made men and women in his image—equal but different. As we’ve lost sight of this foundational truth, confusing and ever-changing theories about gender have captured society’s imagination.” In this equality-based-in-difference frame, sex difference creates different roles for men and women (with potentially different political rights and recognitions) that have equal spiritual importance. In this frame, women’s spiritual equality depends on the institutionalization of femininity as a site of difference, which is in direct opposition to anti-trans feminist views that institutionalizing femininity creates inequality. Per this difference, anti-trans traditionalists become affectively attached to institutionalizing a subjugated femininity to secure their desired position in the sex/gender order, while anti-trans feminists become wary of the subordinated position produced by this institutionalization.

Where anti-trans feminists frame femininity as a subjugating interpretation of sex difference, anti-trans traditionalists frame femininity as a natural mandate. For anti-trans traditionalists, introducing gender is dangerous because it devalues femininity (and the sex-based role for women that follows from it) by claiming womanhood is socially constructed rather than bound up in a natural purpose. To this end, The Conservative Woman (T-UK) writes:

By focusing on superficial characteristics, stereotypes turn male and female into costumes which can be cast off or donned. But stereotypes are only symptoms of a cultural disease which has much deeper roots – the erosion of sex difference. Sex differences emerge out of the fact that women give birth and men don’t. This lies at the heart of everything which makes us women and men.

While this framing, like anti-feminist framings, uses the language of stereotypes to characterize gender, it uses this language to different ends. Where anti-trans feminists argue stereotypes are dangerous because they enforce a link between reproductive potential and purpose, anti-trans traditionalists argue stereotypes are dangerous because they create a concept of gender divorced from reproductive capacity.

Because the anti-trans traditionalist sex/gender order ascribes value to women through their reproductive role, anti-trans traditionalists characterize anything that threatens the ontological link between womanhood and reproduction as devaluing women entirely. They insist transness erases sex difference to erase the sex-based roles that emerge “naturally” from dimorphic sex and prescriptive masculinity and femininity. This framing stokes fear that the unnaturalness of transness and the gender order it tries to impose threatens the natural and prepolitical sex/gender order arranged around patriarchal heteronormativity. Affectively, this narrative that a queer/trans order will replace the patriarchal sex/gender order maximizes fear by mirroring the “affective grammar” of racialized Great Replacement myths also central to anti-gender discourses (Holzberg Reference Holzberg, Holvikivi, Holzberg and Ojeda2024, 184).

Anti-trans traditionalist framing directs its audience’s threat response by maximizing affective anxiety via the generation of contradiction. Anti-trans traditionalists pair their insistence that transness threatens the natural sex/gender order that springs, prepolitically, from cis sex difference with the insistence that protecting the allegedly prepolitical patriarchal sex/gender from transness order depends on a regulatory system that prevents individuals from acting outside of their “inherent” sex/gender role. Paradoxically, anti-trans traditionalists articulate cisness as natural, fundamental, and immovable alongside an articulation of cisness as vulnerable to transness. The anxiety generated through this contradiction justifies regulatory measures to enforce conformity to sex-based roles (even as conformity is presented as biologically inevitable) and formal and informal incentivization of participation in subordinated roles derived from reproductive heteronormativity (even as these roles are presented as prepolitical).

Regulative Regimes

By orienting audiences within circular relationships between the trans threat and cisnormative response, narrative paradoxes within both anti-trans feminist and traditionalist discourses generate the affective momentum needed to sustain regulative regimes that govern sex. Both anti-trans feminist and traditionalist regulative regimes marry practices of social regularization that attempt to define “the authentic woman” (Bassi and LaFleur Reference Bassi and LaFleur2022, 312) and policy agendas that reinforce each interpretation of the authentic woman and her place in each respective sex/gender order. Though both regulative regimes enact cisnormativities similar in form and practices, anti-trans feminist and traditionalist interpretations of cisnormativity differ and therefore order sex to different ends.

Anti-trans feminist regulative regimes construct women as vulnerable by formalizing sex-based rights as a response to legacies of marginalization and then consolidating power via practices of social regularization that weaponize constructions of vulnerability to make demands of the state. Drawing from constructions of womanhood as an institutionalized position of oppression, anti-trans feminist regularization crystallizes sex difference as a mechanism for stratifying the population into classes of subjugated and subjugators. Where anti-trans traditionalists view women’s subjugation as natural, anti-trans feminists argue that men’s role in subjugating demonstrates their inherent violence. Following from their view of sex difference as a site where power is distributed unequally, anti-trans feminists interpret their view of dimorphic sex into a sex/gender order organized through an oversimplified binary of vulnerable females and dangerous males. Confluence Feminist Movement (F-Spain) defends a “definition of ‘woman’ based on sex” because “Gender is not an identity, but a hierarchical system and, therefore, the Confluence declares itself in favor of its abolition.” In this articulation, sex difference signifies a difference in men’s and women’s respective access to power. Social regularization that forms womanhood along the single-axis of sex narrows the power relations that anti-trans feminism is concerned with by claiming women are at the bottom of a hierarchy and therefore have no power. Michelis (Reference Michelis2022) argues that this strategically racially blind characterization of patriarchy “rests on the fiction of a single female experience, a fiction which has routinely silenced and side-lined women who experience racism, colonial domination and other forms of oppression that cannot be singularly attributed to their gender.” Insisting sex alone places women at the bottom of a power hierarchy obscures the very racist and colonial hierarchies that produced (and originally policed) the myth of objective sex difference (Schuller Reference Schuller2017).

Constructing womanhood around sex as a singular axis serves hegemonic feminism by setting up a unidirectional system of oppression that obscures any culpability that women might have in participating in the oppression of others. Storenfriedas (F-Germany) rejects “a trend” where people articulate “that white women, especially white academics, are privileged” and refuses to accept “that there are privileged women in patriarchy.” This social regularization positions victimization as proof of innocence to obscure the way cis women might be proximate to or benefit from hegemonic social orders. This narrowed view of structural power is exemplified in anti-trans feminist dismissals of intersectionality. In response to calls for including Muslim women and other religious minorities in feminist politics, For Women’s Rights Quebec (F-Canada) argues that “Intersectional ideology can pose a danger to women’s right to equality.” Since intersectional feminism refuses simplified hierarchies of oppression, it threatens the presumed innocence that anti-trans feminism depends on.

The anti-trans feminist positioning of sex defined through cisness as a site of innocence works alongside the tactics of white women who construct their innocence through sex defined by whiteness. Pearce et al. (Reference Pearce, Erikainen and Vincent2020) argue, “one’s ability to be recognized or awarded a position as ‘vulnerable’ is conditioned by whiteness and gender normativity.” Just as today’s anti-trans feminism has its furthest reach in white Anglo-American contexts, the early hyper-essentialist form of radical feminism “developed and flourished best among white women” (Alcoff Reference Alcoff1988, 138) because essentialized constructions of identity frame power as something that is had rather than something that is exercised. This allows women to obscure their own culpability in wielding power. The increasing popularity of anti-trans feminism outside of exclusively white contexts speaks to the way that cisness allows women to simultaneously construct powerlessness while asserting power across axes of privilege other than race. Reason and Revolution (F-Argentina) writes that when women’s rights are linked to the rights of other marginalized groups, “Feminism then becomes the instrument and vehicle of different interests which are not those of women.” This view of struggles against marginalization as zero-sum and feminism as something that can be co-opted reveals the nature of anti-trans feminism as a project designed to redistribute marginalization rather than work against it in all its forms.

Anti-trans feminist policy agendas (re)enforce innocence-based constructions through calls to protect single-sex spaces. Narratives about single-sex spaces often depend on pastoral views of womanhood, which solidify cis women’s innocence with logics of sexual exceptionalism equating violence with deviant maleness (read: transfemininity) (Lamble Reference Lamble2025). For example, FIST (F-US) argues, “Female-only spaces, free of all persons born and socialized male” are necessary for “safety and privacy away from the male gaze and the threat of male violence” and “providing spaces for healing; spaces for building bonds of friendship and creating culture and community among women; lesbian-only spaces; and spaces for purposes of political organizing for women’s liberation.” This statement claims that trans women threaten pastoral separatist spaces because they are “socialized male” and insists that trans women bringing the “male gaze” and “male violence” into these spaces is what prevents women from developing transformative bonds. Serano (Reference Serano2022) argues that separatist politics sort men and women into the paradigms of predators and prey to associate political danger and virtue with identity rather than practice and reinforce essentialized innocence.

Anti-trans feminists weaponize vulnerability-as-innocence to call upon the paternalistic state for protection. No Self ID’s (F-Japan) defense of sex-based rights is based on the assertion that “The average woman is physically weaker and more vulnerable than the average man.” Establishing vulnerability foregrounds calls for protection. This articulation plays into the patriarchal narrative of women as biologically weaker and, once again, collapses the radical feminist argument that women are constructed as weak with an essentialist endorsement of women as materially weaker. This vulnerability-based interpretation of sex difference insists that patriarchal domination occurs deterministically from the material of sex difference when, in actuality, it stems from a perception of individuals as “actually, properly, or potentially socially positioned as powerless” (Heaney Reference Heaney and Heaney2024, 12).

Anti-trans feminists call for sex-based recognition is fundamentally a call to be recognized as protectable on the basis of sex. In a blog post describing their counterprotesting at a Pride parade, a writer for ReSisters (F-UK) writes, “Police were there but did not keep the mob separate from us—we were surprised by this. We after all numbered just five women holding the banners, and the crowd were hostile.” The way the author contrasts “just five women holding the banners” with the “mob” constructs women’s vulnerability by portraying them as necessarily unthreatening by the nature of their identity and requiring protection on that basis. The use of the word “surprised” here speaks to an existing expectation that the job of the police is to keep women like the author safe. Similarly, FIST (F-US) demands the ability for women to:

Express our opinions on gender and sex-based oppression and engage in public debate on these topics without fear for our physical safety or livelihoods. We demand an immediate end to the threats and acts of violence, slurs (“TERF”), doxing, harassment, retaliation, and no-platforming carried out by vocal sections of the transgender movement in order to intimidate and silence us. Such tactics have more in common with fundamentalism, totalitarianism, and terrorism than those of a genuine liberation struggle.

Characterizing TERF as a slur elevates the accusations that feminists might act violently through transphobia as hate speech. The “demand” for “an immediate end to” being called a TERF is accompanied by the implicit demand that the state censor anyone who accuses a woman of being trans-exclusionary. FIST’s classification of transgender resistance to TERFism as “terrorism” contrasts anti-trans feminists’ “acceptable” power enacted through state protection/violence with a characterization of trans power as extra-state (and, therefore, unacceptable). This call for state protection demonstrates what Amery (Reference Amery2025b, 3) describes as a “will to power” that “Manifests as an affective attachment to governance and to governmental project” and links cis and white feminisms. Anti-trans feminism “blames all men for all violence but only demands the punishment of trans women, ignoring racism, colonialism, and capitalism” (Gill-Peterson Reference Gill-Peterson2024, 25).

In sum, anti-trans feminist regulative regimes formalize sex-based rights and single sex spaces and regularize constructions of womanhood grounded in vulnerability-as-innocence to empower cis women to call upon the state for protection and consolidate power through gaining access to the marginalizing arm of state policing. Hemmings (Reference Hemmings2018, 964) argues feminist projects that are affectively attached to single-issue sexual politics “can be put to work in securing a global landscape of uneven freedoms within a nationalist framework.” Once again, this strategy is paradoxical. Anti-trans feminists allegedly support gender abolition to reverse subordinating interpretations of sex difference and therefore pair their agenda of sex-based rights with policies such as affirmative action for women, increased civil and political rights, and access to reproductive autonomy, which are all positioned to work against state-enforced sex-based differentiation. Yet, anti-trans feminists’ ability to access power and call upon the state depends on their ability to maintain a political innocence they construct through sex-based subordination. This fractured relationship to sex-based differentiation and subordination relies on “an ethos of liberation through control” where anti-trans feminism “claims to be a movement for liberation from gender at the same time as it advocates for the surveillance and control of gender deviants. This control is in fact justified on the grounds of freedom, namely cis women’s freedom from gender inequality and discrimination” (Amery Reference Amery2025a, 1249). Further marginalizing trans women is a nonsensical strategy if anti-trans feminism’s goal is—as it alleges—working against all sex-based marginalization. However, this strategy is well suited to giving anti-trans feminists access to the marginalizing arm of patriarchy to use to redistribute power in their favor.

Anti-trans traditionalist regulative regimes are produced through social regularization that forms womanhood through reproductive roles and policy agendas that formalize incentives and constraints that (re)enforce conformity to these roles. In these regimes, anti-trans traditionalists authenticate women as mothers, and sex-based rights anchor women to reproductive roles. Worldwide Organization of Women (T-US) writes, “Motherhood is the most womanly act a woman ever engages in.” In this framing, anti-trans traditionalists are clear that conforming to the reproductive imperative of sex—rather than merely occupying a sex-based category—authenticates a woman.

Anti-trans traditionalists regularize conformity to the same complementarity-based reproductive roles they claim are inevitable by strengthening the constraining function of the nuclear family. Real Women of Canada (T-Canada) identifies itself as a “pro-family women’s movement” that locates women’s rights and recognition within the family. Moms for America (T-US) urges mothers to “Make your home a fortress.” This militarized language frames the family as both vulnerable to attack and a front from which women can act. Femina Europe (T-France) describes their efforts to “rehabilitate the true identity of women” by promoting “the role played by women in the transmission of oral culture and intangible heritage” and describes women’s role in the nuclear family as providing “an uninterrupted succession of generations that allows for transmission.” Here, women’s reproductive role operates on two levels: literally through birthing children and ideologically through the “transmission” of certain values. This reflects an understanding of the family rooted in reproductive futurity (Edelman Reference Edelman1998), where the promise of children is offered as a way to guarantee a national future. As Enloe (Reference Enloe2014) argues, women’s role in socializing children to submit to patriarchal family structures often prepares them to submit to patriarchal natural structures. This patriarchal socialization works alongside the reproduction of “intangible heritage” (read: whiteness) where the state controls sexuality in order to preserve hegemonic racial orders (McWhorter Reference McWhorter2009). Hemmings (Reference Hemmings2018, 965) argues that the “role that women play as producers of nation” has been formed in global and hegemonic systems of power, which make them “racialized gender roles as part of a colonial civilizing mission.” By regularizing their reproductive role as stewards of hegemony, women benefit from proximity and access to power. Despite assumptions that men enforce patriarchy, these four organizations are all women’s organizations and demonstrate a strategic choice by traditionalist women to regularize the role of women as reproducers to consolidate power within an order that values reproduction’s role in preserving hegemonies.

Anti-trans traditionalists formalize this regularization of reproductive roles through policy agendas that constrain reproductive agency. Because the patriarchal family lies at the middle of the patriarchal cisheteronormative sex/gender order, formalization of policies to promote the family encompasses attempts to preserve the link between sex difference and sex role that precedes the family and the national order that follows from the family. Because transness and gender ideology threaten the very first link (between sex difference and sex-based roles), anti-trans traditionalists systematize this broader policy agenda through the threat of transness. Lifesite News (T-US) writes, “The same demons that hate the sanctity and beauty of human life also hate the sanctity and beauty of marriage, established by God for the sake of bringing forth and nourishing new life. These demons are seeking to destroy these two goods through abortion and the transgender insanity.” This statement links transness and abortion because they interrupt the chain of relation between sex difference and fulfillment of reproductive roles. In addition to restricting reproductive autonomy, anti-trans traditionalists’ policy agendas restrict same-sex marriage and adoption rights, no-fault divorce, and increased participation for women in the workforce to protect the reproductive-based chain of relations.

Despite the insistence that the traditionalist sex/gender order prepolitically precedes the state, anti-trans traditionalists lobby for regulative regimes that enforce the interpretations of sex difference that stabilize the traditionalist sex/gender order. Family Policy (T-Russia) writes that one of its core goals is “To promote the protection of family, motherhood, fatherhood and childhood, as well as strengthening the prestige and role of the family in society.” The language of “promote” and “protection” calls upon explicit regulation. To navigate this paradox of an order that is both prepolitical and needs political maintenance, anti-trans traditionalists reframe authoritarian attempts to enforce cisheterosexuality as defensive measures to protect against the enforcement of gender ideology. Heritage Foundation (T-US) warns of “federally mandated gender ideology” and Children in Danger (T-Germany) warns that “it is not uncommon for federal ministries or federal authorities to behave like gender or LGBTQI lobbyists.” These foreground what are, in actuality, calls for government regulation of sex (protective of cisheterosexuality) by framing enforcement of cisheterosexuality as a defense against government regulation. This paradox allows anti-trans actors to frame transphobia as defensive and reverse the relationship between oppressor and oppressed (Schotten Reference Schotten2022).

The mandate to police the deviant and unnatural other serves as a cover that obscures the active work needed to enforce the “natural.” For example, the Dads4Kids (T-Australia) writes, “We live in an age of gender confusion. Much of this is a result of the deliberate attempt by various social engineers to convince us that gender is not fixed or static, but fluid and changeable.” In this framing, the language of “social engineers” portrays gender ideology as a means of re(ordering) social institutions. Gender ideology, presented dialectically to traditionalist sex/gender order as a “deliberate attempt" to “convince” society of its worldview, constructs cisheteronormativity as independent from social engineering. This discourse culminates in a paradoxical view of sex difference as both concrete and fragile. Anti-trans traditionalists dismiss “gender ideology” by insisting sex difference (and the order following naturally from it) is inherent, immovable, and deterministic, while also claiming transness and gender ideology pose a real threat to that sex order by chipping away at the fundamental linkages between sex difference and sex-based purpose.

Conclusion

My analysis demonstrates why the counterintuitive coalition of anti-trans feminists and traditionalists works: the contradictions at the heart of this alliance create the affective momentum needed to sustain circular projects where anti-trans actors’ agendas depend on oppositional relationships to the same threat they promise to protect their audiences from. Both anti-trans feminists and traditionalists construct a trans threat to sex-based rights as a way to form their audience’s attachments to sex-based rights and sex difference. Then, anti-trans feminists and traditionalists mobilize these attachments to sex difference in service of regulative regimes that strengthen cisnormativity and consolidate power through the enforcement of cisnormative sex/gender orders. My comparative analysis of anti-trans feminist and traditionalist discourses demonstrates the process through which this affective governance occurs and generates two key insights.

First, I identify the role of paradox and contradiction in reactive politics. I break from characterizations of advocacy as rationally deliberative processes aimed and resolution, and, instead, demonstrate how the illogics and contradictions at the core of this anti-trans coalition empower the efforts of both groups. I argue that contradictions and paradoxes allow anti-trans actors to set up an existential problem where actions framed as ameliorative perpetuate rather than assuage vulnerability. Anti-trans feminists frame patriarchal sex/gender orders as simultaneously caused and solved by institutional recognition based on sex difference. By interpreting sex difference as the basis for a construction of women as vulnerable and innocent and institutionalizing this interpretation through sex-based rights, anti-trans feminists engage in the very practices of sex-based stratification that they attribute to patriarchy. Rather than making women less vulnerable, anti-trans feminist tactics of sex-based governance preserve the vulnerability of women as a site from which to call upon the state. This contradictory relationship between threat and solution places women into a circular vulnerability that affectively primes women for a dependent relationship to the state to sustain its biopolitical regimes. Similarly, anti-trans traditionalists frame patriarchal sex/gender orders as simultaneously prepolitical and dependent on political intervention. By interpreting sex difference as a mandate for “natural” reproductive roles for men and women and pursuing policies that mandate conformity to these roles, anti-trans traditionalists undermine the distinction between the naturalness of cisness and the artificial engineering of transness that their worldview depends on. Rather than defending the natural sex/gender order, anti-trans traditionalist tactics of sex-based governance create a political infrastructure that ensures the family (and the sex/gender order that surrounds it) remains a site of political contestation and regulation. This contradictory relationship between threat and solution leaves the “naturalness” of the family dependent on the social engineering of the state.

By identifying paradox as a strategy, I caution against dismissing anti-trans feminism and traditionalism as viable threats because they lack logical consistency, compelling evidence, and coherent agendas. While these characteristics might (but do not always) predict success or failure in deliberative politics, I demonstrate that these anti-trans projects are not subsumed by policy processes. In the affective realm of sex/gender governance, the incoherence of these anti-trans discourses ensures that the existential anxiety and insecurity stoked by these discourses are too muddled to be easily resolved. This circular relationship between threat and solution maintains attachments between the anxious populus and the regulative regimes they turn to for security.

Second, my comparative analysis of discourses reveals regimes that share form while differing in content and effect. Recognizing common form and strategy isolates which practices are necessary to cisnormative attempts to consolidate power. Attention to shared affective strategies allows us to identify what transphobia does and what about this effect makes it valuable to diverse actors with different intentions. I demonstrate that transphobia allows anti-trans feminists and traditionalists to generate identity-based attachments to the fiction of sex difference that are inevitably fraught, and this invites an insatiable loop of identity-based securitization. I show that both anti-trans feminism and traditionalism order sex through regulative regimes that work through dialectic processes of regularization and formalization of sex-based subjectivity, treat sex as dimorphic to ground oppositionally constructed sex classes, weaponize constructions of victimization to frame offensive identity-based policing as defensive through shared imaginings of erasure-based threats, and pair linked race and sex-based essentialism to carve out power for privileged women within hierarchal cisnormative sex/gender orders.

Attending to the differences in the content and effect of these anti-trans discourses problematizes the association of transphobia (and exclusionary politics generally) with any singular partisan, religious, or cultural context. The cisnormativity of anti-trans traditionalists interprets sex difference as grounding roles for men and women based around reproductive capacity, organizes relationships between men and women through a patriarchal cisheteronormative reproductive nuclear family, and then enacts social, political, and national structures through extrapolating and reproducing these dynamics. Within anti-trans traditionalist sex/gender orders, cis women consolidate power through framing their own reproductive work as central to the maintenance and transmission of hegemony and call upon the state to maintain this position by formalizing the structural position of the family.

Anti-trans feminist cisnormativity interprets sex difference as essentialized—rather than enacted—vulnerability to ground a sex-gender order where women’s vulnerability-as-innocence gives them access to state power. By characterizing patriarchal exploitation as an exclusively cis female experience, anti-trans feminists work against devaluation on the basis of sex rather than through the ascription of femininity. Like the white feminism that precedes it, this leads to a redistribution of patriarchal exploitation (Carby Reference Carby2007). Feminism protective of cisness “offers women the opportunity to advance in the current patriarchal hierarchy of values” (Heaney Reference Heaney and Heaney2024, 1) by oversimplifying the necessary relation between female bodies and subjugation and strategically ignoring that feminization is not an exclusive experience of cis women. Rather, subjugation is enacted through devaluation, not exclusive to female sex difference or even women as a class. This article focuses primarily on the variation between anti-trans feminism and anti-trans traditionalism and does not fully account for variation within categories. Further work that distinguishes between how white anti-trans feminism and anti-trans feminism in racially marginalized contexts differ in how they redistribute the burdens of marginalization would enable a deeper analysis of differences among cisnormativities.

While anti-trans traditionalists consolidate power through strengthening conventional (cishetero and reproductive) conditions of patriarchy, I demonstrate that anti-trans feminists consolidate power by reinterpreting patriarchy. In making these distinctions, I am not presenting anti-trans feminism as the lesser of two evils. Rather, my analysis of difference picks up on the versality of transphobia through application of my Affective Orientation Threat Structure. All anti-trans sex-based governance is hegemonic because it depends on constraining allowable embodiments, but stratification along sex-based roles requires interpretations of sex difference. Analyzing the language of anti-trans discourses demonstrates that these interpretations vary, and this variance produces different sex/gender orders. When we understand that these anti-trans regimes depend on regularizing identity-based interpretations of sex difference alongside the formalization of sex-based rights, it becomes clear that it is not enough to work against transphobia by refuting anti-trans talking points. Transphobia is a useful resource for so many political projects because it provides the affective momentum needed to keep the circular project of identity-based destabilization and re-stabilization in motion. Based on my findings, I encourage further theorization about how queer, feminist, and trans movements might return to a politics against identity (Butler Reference Butler1997) and direct an affective embrace of destabilization as productive of possibility rather than necessitating policing.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X26100610.