The tabulation of historical events appears early in Chinese historiography, before the second century ce. When Sima Qian 司馬遷 (d. ca. 86 bce) was compiling his Shi ji, he felt the need to provide a historiographical design that could “present” (biao 表, the same character as “table or chart”)Footnote 1 the “different generations [of the ruling houses] at the same time whose chronologies varied and were not clear” (并時異世, 年差不明), and he therefore “created ten tables” (作十表).Footnote 2 Although the historiographical subgenre of “table” would be later established as standard in official histories, at this point, these newly invented tables did not follow a singular design, especially in terms of what the vertical and horizontal axes referred to. For instance, the very first table in the Shi ji, the “Table of the Three Dynasties,” only expands on a single axis of various noble clans.Footnote 3 In contrast, just next to this, the Shi ji table of the Spring and Autumn Period (“Yearly Table of the Twelve Feudal Lords”) has a two-dimensional structure with discrete axes for space and time.Footnote 4 Like the table of the Spring and Autumn Period, most of the ten tables in the Shi ji are two-dimensional.Footnote 5 This inconsistency within the ten tables of the Shi ji leads to the question: How do historical accounts, like those of the Spring and Autumn Period, necessitate this primarily two-dimensional tabular design in the Shi ji?

The answer lies in Sima Qian’s own notes. In Sima Qian’s preface to “Yearly Table of the Twelve Feudal Lords,” he discusses the compilation and dissemination of the accounts in the Spring and Autumn Period after the death of Confucius that extend to his own time: From Zuo Qiuming, the acclaimed author of the Zuo Tradition,Footnote 6 until Dong Zhongshu, a contemporary classicist scholar in Sima Qian’s time, those who adopted texts of the Spring and Autumn Annals were “too numerous to be recorded.”Footnote 7 Continuing his discussion about the Annals’ frequent textual appearance, Sima Qian then shifts to discuss the various approaches that people with different expertise focus on: Neither the classicist, the advisors, or experts on calendar and calculation, nor those who recorded genealogical registers “strove to comprehensively examine the beginning and end of the Annals accounts” (不務綜其始終).Footnote 8 Therefore, the multiplicity of the Spring and Autumn texts and the fragmentary status of these texts both result in barriers to achieving “an overall view at various important points” (一觀諸要) in the time period.Footnote 9 For this purpose, Sima Qian “displayed by table” (表見) “the crucial points of prosperity and decline,” (盛衰大指) which were argued by the scholars of the Annals and the Discourses of the States (both accounts of the Spring and Autumn Period) in this Shi ji chapter. Reading the extant Shi ji table of the Spring and Autumn Period, one easily realizes the difficulties Sima Qian faced, as this information has a high degree of numerical and spatial complexity across a long period.Footnote 10 Therefore, this large corpus of historical events and figures requires a historiographical method above and beyond linear and sequential narratives to process and preserve it.

However, Gu Donggao’s 顧棟高 (1679–1759) Chun qiu dashi biao 春秋大事表 (Tables of Major Events in the Spring and Autumn Period), also a well-known and significant tabulation of the Spring and Autumn Period history and a continuation of Sima Qian’s tables,Footnote 11 diverges sharply from the aforementioned form established in the Shi ji. As an astute reader of both the historical accounts of the Spring and Autumn Period and Sima Qian’s tables,Footnote 12 Gu, rather than adopting the two-dimensional design established by Sima Qian, categorizes historical accounts by topic, including dates, territories, cities, noble ranks, topography, battles, annexations, rituals, events involving women, and more in the Chun qiu dashi biao. Gu outlines his purpose for tabulating these accounts in “Du Chun qiu Oubi” 讀春秋偶筆 (Occasional writings on reading the Spring and Autumn Annals), which contains his miscellaneous thoughts on reading the history of the Spring and Autumn Period:

Reading the Spring and Autumn Annals requires an ultra long distance viewpoint: if it is short, one can see a decade or several decades; if it is long, one can comprehend the 242 years [of the Spring and Autumn Annals].Footnote 13

看春秋眼光須極遠,近者十年、數十年,遠者通二百四十二年。

The adjective Gu uses here, yuan 遠 (translated as “long,” referring to distance), can refer to both time and, as will be demonstrated below, space, the two crucial factors of the historical tables. The idea of looking at the history of the Spring and Autumn Period as a whole is undoubtedly an echo of the Sima Qian’s thoughts on tabulation aiming at “an overall view at various important points.”Footnote 14 However, despite its format being described as pangxing xieshang 旁行邪上 (written sideways and obliquely), which is also used to describe Sima’s tables,Footnote 15 the design of Gu’s tables as presented in Chun qiu dashi biao is in no way similar to that of Sima Qian. Moreover, the design even casts doubt on Gu’s beliefs in viewing that historical period from a long distance, that is, in this context, viewing historical events over a long period of time all at once in his tables.

To understand the distinct tabulation choices made at the different times, the analysis below will examine the tabular formats used to process and preserve the historical accounts of the Spring and Autumn Period in the Shi ji and Gu Donggao’s Chun qiu dashi biao in the late imperial period.Footnote 16 How do the Shi ji tables adopt, tabulate, and represent existing historical accounts as visual and spatial presentations? How did Gu Donggao employ a tabular format other than the conventional one that originated in the Shi ji while exploring a new “overview” of historical events as Sima Qian once had? Through the varied tabulations of a particular historical event, the siege involving the states of Qin, Jin, and Zheng taking place in 630 bce, this article investigates the historiographical tabulation established by the Shi ji and its adaptation in later historical contexts.

Between Paragraphs and Table Cells: The “Table of Twelve Lords” and other Shi ji Accounts

The “Table of Twelve Lords” is by no means the only chapter about the history of the Spring and Autumn Period. Many of the events appear in more detailed versions in the hereditary house (shijia 世家) chapters categorized by state. Although occasional differences were already discernible to scholars since the earliest annotations to the Shi ji,Footnote 17 because this table records events that took place in the twelve feudal states from 841 bce to 477 bce, it includes information that overlaps with the hereditary house chapters. This overlap has led to discussion and criticism of the tabular format itself.Footnote 18 However, these debates have centered on Han tables, rather than those focusing on the pre-imperial period. Though they centered on a period long before Sima Qian’s era, these pre-imperial tables preserve historical information available in other extant materials, such as the Zuo Tradition and the Discourses of the States,Footnote 19 in a new fashion, and so the reasoning behind the tabular format is easier to see in chapters such as the “Table of Twelve Lords.” Moreover, since the tables and the hereditary house chapters were products of the same body of primary sources available to Sima Qian, a comparison between the linear narratives and the tabular ones will highlight his use of the tabular format to sift and process historical events. The comparison that follows will begin with a series of events in the “Hereditary House of Zheng,” in which Qin, Jin, and Zheng were involved, and then turn to the corresponding presentation of events in the “Table of Twelve Lords.”Footnote 20

The Hereditary House Narrative

The series of events in the “Hereditary House of Zheng” took place in 630 bce, when Jin besieged Zheng with the help of Qin. With several states’ involvement and tangled interstate interests, the siege was naturally multifaceted. The account of 630 bce in the “Hereditary House” thus captures this situation through several narrative threads, which roughly consist of five parts.Footnote 21

In the first part, the “Hereditary House” introduces the basic information of this siege (when, where, and who) and then states the two reasons for the siege: “for punishing it [Zheng] for assisting Chu in attacking Jin as well as for not treating Lord Wen with propriety when he passed through” (討其助楚攻晉者,及文公過時之無禮也). That is, Zheng had betrayed its alliance with Jin in two ways. First, Zheng had helped Jin’s enemy, Chu. Second, Lord Wen of Zheng did not treat Lord Wen of Jin with propriety when the latter passed through Zheng in 637 bce.

In the second part, the “Hereditary House” narrative shifts to introduce events associated with a seemingly minor player, Zilan 子蘭 (also referred to as “Lan”), a son of Lord Wen of Zheng. Most of the late lord’s sons were dead or in exile, while Zilan was serving Lord Wen of Jin and thus returned to Zheng because of this siege. He “served Lord Wen of Jin with considerable attentiveness” (事晉文公甚謹), currying favor with the Jin lord and “seeking to be brought into Zheng as heir” (求入鄭為太子). This background information in the second part may seem unrelated to the earlier narrative of the Jin siege in the first part, but it suggests and builds up Zilan’s candidacy for lordship within the context of the siege.

The third part turns to the outcome of Zheng’s inappropriate treatment of Lord Wen of Jin covered in the first part. The Lord of Jin wanted to execute Shu Zhan 叔詹 (d. 630 bce), a Zheng official involved in the inappropriate treatment. Zhan voluntarily committed suicide after a short speech to the Zheng lord. In this part, Zhan’s speech takes up considerable space, emphasizing his character rather than the events of 630 bce. Zhan’s death did not end the siege of Zheng. Even though Zheng gave the body of Zhan to the Lord of Jin, the lord insisted to “once [more] meet the Lord of Zheng, insult him, and leave” (一見鄭君, 辱之而去).

Therefore, in the fourth part, Zheng turned to another party in the siege, the state of Qin. Qin was convinced to withdraw their troops from Zheng by the compelling argument of Zheng’s envoy: “Defeating Zheng will benefit Jin; this is not to the profit of Qin” (破鄭益晉, 非秦之利也).Footnote 22 The fourth part follows neither the narrative thread of Zilan nor the thread of Jin’s revenge.

The fifth part again picks up the narrative thread of Zilan, in which a Zheng official, Shi Kui 石癸, gave a speech about installing Zilan as the Lord of Zheng, arguing that his mother’s lineage and the current siege led by Jin made Zilan suitable for the position: “Now Zheng is besieged to the point that it is in dire straits, and Jin has made this request for [him]. What profit could be greater than this?” (今圍急, 晉以為請, 利孰大焉). As a result, Zheng “made a covenant with [Jin] and finally installed Zilan as Heir” (與盟, 而卒立子蘭為太子) and the Jin troops withdrew.

Overall, these five parts in the “Hereditary House” barely contain any transitions, moving abruptly between short narratives that focus on Lord Wen of Jin, Lord Wen of Zheng, Zilan, Shu Zhan, and Shi Kui. Only loosely related to the siege, the pieces hang together mainly because of the linear narrative structure of the “Hereditary House.”Footnote 23

The “Yearly Table” arranges these pieces differently, however, according to the perspectives of Jin, Qin, and Zheng, with many omissions and abridgements.

The Table

To understand the tabular arrangement of the aforementioned events in 630 bce, an introduction to its layout is necessary. The “Table of Twelve Lords” is a two-dimensional table with column (controlling the vertical) and row headers (controlling the horizontal) that records events from 841 bce to 477 bce. In the earliest existing edition of the Shi ji, the column header is the year while the row header divides the table into fourteen domains (one kingdom and thirteen feudal states).Footnote 24 There are over five thousand cells in the columns and rows, but only around one fifth of them contain records; when an event record is not present, the cells merely contain the year number of the reign in each state. For example, in the second year of Lord Zhuang of Zheng (742 bce), the cell simply reads “two” (er 二). Although the original format and writing material(s) of these tables in the time of Sima Qian are unclear (in all probability, silk scrolls or bamboo slips), it is generally believed that the extant editions retain some major features of the original ones.Footnote 25

In the 630 bce column of the “Table of Twelve Lords,” the events are listed as follows, beginning with the year number of the reign in each state:

[Row for Jin:] 7th [year of Lord Wen 文] [Jin] complied with Zhou and sent back Lord Cheng of Wey. [Jin], along with Qin, besieged Zheng.

七 聽周歸衛成公。與秦圍鄭。

[Row for Qin:] 30th [year of Lord Mu 穆] [Qin] besieged Zheng; there was a [persuasive] speech, thus [Qin] left.

三十 圍鄭,有言即去。

[Row for Zheng:] 43rd [year of Lord Wen 文] Qin and Jin besieged us, for the sake of Jin.Footnote 26

四十三 秦、晉圍我,以晉故。

Unlike the “Hereditary House,” the table omits the results of the siege, not even implying an outcome. Although the table’s language is usually formulaic (as seen above), this does not mean that it has undergone a thorough editorial overhaul. Despite the concise language of the table entries, the varied sentence subjects (“us” in Zheng, and omitted subjects in Jin and Qin) still suggest varying sources of information,Footnote 27 echoing the multilayered “Hereditary House” narratives.

The multiple temporalities and textual layers of the “Hereditary House” are brought into a single field of vision in the table at the cost of the events’ details. Compared to the “Hereditary House,” the “Yearly Table” only sketches the siege’s basic information, probably due to the limited space in the table’s cells.Footnote 28 Even so, a different sense of temporality is evident. The table does not include the background of Zilan’s installment, Shu Zhan’s suicide, or Shi Kui’s speech; instead, it focuses narrowly on the siege and the different roles played by the three states in it. Without going back and forth in the timeline, the table simultaneously presents information from the perspectives of different states. Unified under the same column header, the year 630 bce,Footnote 29 the events concerning each state are presented as happening at the same time, creating a sense of synchronization. The table thus offers a different presentation of the multiple temporalities marked by terms like “at the time” or “only then” in the “Hereditary House,” which one can only read linearly and sequentially.

This multiplicity is significant. Textually, it seems easy to believe that the table merely repeats, paraphrases, shortens, or omits the texts of the “Hereditary House,” and at first glance, the small textual slice of the table and its corresponding “Hereditary House” parallel hardly confirm the table’s originality. It even seems natural to think that the tables were arranged on the basis of finished (or at least drafted) chapters of the “Hereditary House.” However, from a structural point of view, the tabular form is crucial for the tables and the hereditary house chapters of the Shi ji. Scholars have advanced compelling hypotheses regarding how Sima Qian organized the “Hereditary House” chapters and chronological tables.Footnote 30 They believe that Sima Qian used individual bamboo slips to copy information from various sources and arranged the slips in particular ways (by year or state, for example) before assembling them into scrolls. With one or more sets of bamboo slips at hand,Footnote 31 Sima Qian then copied the information from the slips when writing the “Hereditary House” chapters or tables.Footnote 32 Building on these arguments, one or more proto-tables—that is, bamboo slips recording events and grouped by year like table cells—must have preceded the synthesized linear narratives; the composition of the five disconnected parts in the “Hereditary House” above is easier to imagine with bamboo slips formatted in this way. Therefore, even though the tables themselves seem to depend on chapters with long narratives like the “Hereditary House,” the tabular framework embedded in the tables is key to the writing of the pre-imperial hereditary house chapters and even determines the overarching design of the Shi ji.

The significance of the tabular form is even greater when we consider its spatial dimension. Many scholars have pointed out that the tabular form used in historiography excels at showing historical trends and embodying Sima Qian’s various views of history,Footnote 33 but they hardly specify how such an effect is achieved, particularly through a visual or spatial perspective.Footnote 34 In addition to discussing this, I will also show how the tabular form allows historiographical flexibility.

The arrangement and consequent reading method of the “Yearly Table” and other chronological tables in the Shi ji is usually described as “writing sideways and obliquely” (pangxing xieshang), a phrase coined by Huan Tan 桓譚 (40 bce–28 ce).Footnote 35 Though its exact meaning is still controversial, the phrase is generally believed to refer to a different method of editing and reading than that used for linear text, in that the editing and reading of a table can be horizontal, diagonal, and vertical.Footnote 36

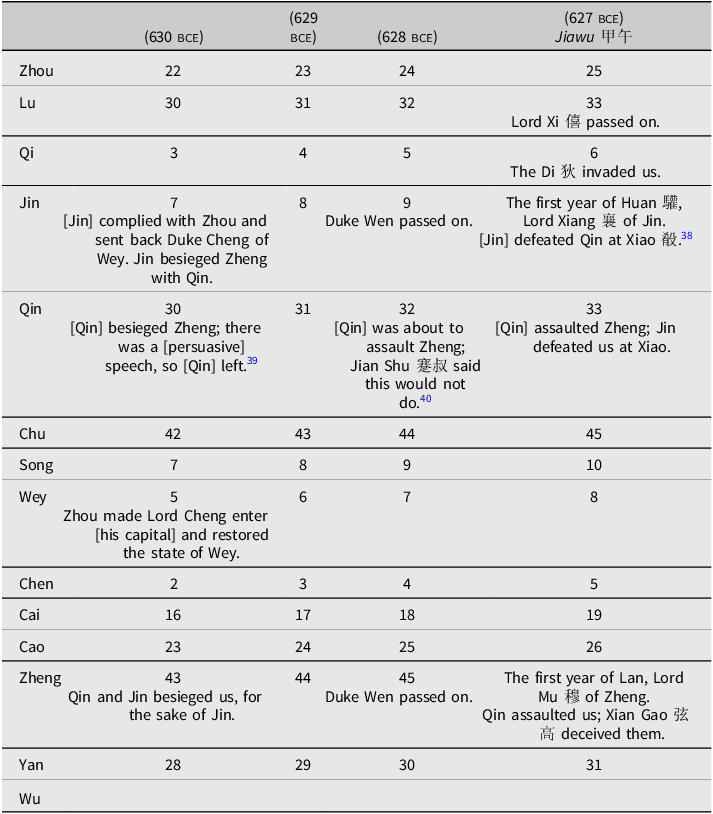

Table 1 is a part of the “Yearly Table” from 630 bce to 627 bce, as typeset in the 1959 edition (Figure 1).Footnote 37 This table follows the disproportionate layout of that edition, with unevenly sized table cells and a uniform font size, designed to maximize content in a given space. Its editors added the column headers corresponding to the Common Era years (630–627 bce), while the row headers (name of states) appear only at the beginning of the table.

Figure 1. The Zhonghua edition of the “Yearly Table” for 631–627 bce.Footnote 41

Table 1. “Yearly Table” (630–627 bce)

While the four columns, beginning with that of 630 bce, offer only scattered information, they contain the potential to sketch out a sequence of events. For example, after the siege led by Qin and Jin in 630 bce, the 628 bce column presents the aftermath: Qin planned to attack Zheng in 628 bce (probably taking advantage of Lord Wen of Zheng’s death in the same year) and carried out the attack in 627 bce. A merchant from Zheng, Xian Gao, met the Qin army marching towards Zheng on the road. He tricked the Qin army by offering twelve oxen to “comfort and please” (lao 勞) them, pretending that the Lord of Zheng had offered the oxen and that Zheng knew Qin’s plan. Thinking that their surprise attack was anticipated, the Qin army retreated. At the same time that Jin came to Zheng’s aid, taking advantage of the opportunity to defeat Qin at Xiao.Footnote 42 Of course, the table only sketches out some of these basic facts: many of the details, such as why Zilan, the new Lord of Zheng, was able to get Jin’s help, are related in the “Hereditary House.”Footnote 43 This is hardly the only point of overlap between the two chapters; earlier cells of the table record the birth of Zilan with an auspicious omen as well as the humiliation that Lord Wen suffered at the hands of Jin in Zheng.Footnote 44 However, combined and read together, these table cells offer something lacking in the “Hereditary House”: They allow readers flexibility in interpreting the relationships between events described in the cells. For example, one will easily connect the defeat of Qin with Xian Gao’s trick, while the remonstration of Jian Shu foreshadows the failure of Qin in cells for Qin, Jin, and Zheng in 627 bce. Open-ended narratives accordingly form through connections like these. Although the “Hereditary House” provides more details, it is never as flexible as the “Yearly Table,” which offers unlimited possibilities for parsing the cells, rearranging them, and thus reinterpreting these seemingly basic facts to form various historical narratives.

Given the potential of the tabular form to shape diverse, limitless narratives, I turn now to exploring its visuality through two Song (960–1270) editions of the Shi ji that have survived: the Northern Song Jingyou 景祐 edition and the Southern Song Huang Shanfu 黃善夫 edition.Footnote 45 Unlike the 1959 edition, which benefits from contemporary typesetting techniques (see Figure 1, on which Table 1 is based), earlier editions of the Shi ji vary in the arrangement of the tables and exhibit different visual characteristics.Footnote 46

In the woodblock printed editions (Figures 2–3), the “Yearly Table” is arranged differently due to different printing processes and techniques. In the Jingyou edition (Figure 2), the table cells are roughly the same size, while the font size varies according to the length of the text in each cell. The Huang Shanfu edition (Figure 3), on the other hand, uses the same font size and varies the size of the table cells on each page according to the text’s length. Publishing designs differ, but all contain identical content and reflect the flexibility of the tabular format in parsing and forming narratives—readers can start from or stop at any cell to form a historical narrative.

Figure 2. The Northern Song Jingyou edition (北宋景祐本) for 631–627 bce.Footnote 47

Figure 3. The Southern Song Huang Shanfu edition for 630–625 bce.Footnote 51

Both editions highlight the visual features of the “Year Table” more than the 1959 edition does. Instead of simply focusing on the cells with the recorded events, the typesetting of the two woodblock editions directs the reader’s attention to the year numbers rather than the coexisting textual records in the cells. The year numbers in sequence are either equal to or larger than the textual records, especially in the Huang Shanfu edition, and in the Jingyou edition, the year numbers are always placed in the middle of the cells. These bold year numbers are helpful when using the tables as indexes for quick searches (e.g., what happened in year X of Lord Y); moreover, the year numbers emphasize not only the contrast between themselves and the textual records in the cells, but also the contrast between the cells with textual records and those without.

Visually, due to the two types of table cells, the information density in each domain changes strikingly no matter in which direction the reader moves across the table. The areas or years with more information are easily recognized as eventful; the cells with only year numbers preserve the sequence of reigns in each domain while also suggesting non-involvement in major events. This arrangement fits well with the purpose of the tables as stated by Sima Qian. These are intended to provide “an overall view at various important points” (一觀諸要);Footnote 48 Sima emphasizes the visual aspect of historiography. The tabular form itself, which does not require a thorough reading of its contents, thus delineates an understated visual aspect of historiography.Footnote 49

Building on the visual characteristics of the table, the tabular format also provides a sense of space. This sense of space is not geographic, because the arrangement of the vertical headers (states) does not follow any rules of geography.Footnote 50 Rather, the spatiality here refers to an imaginative space of readers’ reading and viewing where they could choose to skim or to stop and read.

Readers of the Shi ji tables have remarked on its spatiality in the late imperial time. The late imperial scholar Mei Wending 梅文鼎 (1633–1721) referred to the tables’ spatial features in a preface written for his contemporary Wang Yue’s 汪越 (fl. 1721) Du Shi ji shibiao 讀史記十表 (Reading the Ten Tables of the Shi ji). After commenting on the Shi ji’s structure,Footnote 52 he described the benefits of the tables from a spatial perspective: “After this [the tabulation], the plains and slopes, the successes and failures over thousands of years, are as [clear] as if they could be pointed out in the palm of one’s hand.” (然後數千百年之平陂得失, 如指諸掌).Footnote 53 The plains and slopes here are not only metaphors for less eventful times and times of upheaval; they also highlight how Mei viewed the tables from the perspective of a reader. Although the tables are physically flat, they tell the historical ups and downs in a space imagined by the readers’ experience.

More precisely, the “plains and slopes” refer to the two types of cells—those with year numbers and those with both numbers and short narratives. The uneventful years indicated by strictly year numbers are plains, while the eventful years with short narratives are as remarkable as slopes on plains. Readers can easily pass the plains, but traversing the slopes may require more effort. The concepts of “place” and “space” defined by Yi-fu Tuan can better illustrate this spatial experience of reading the tables.

“Space” is more abstract than “place.” What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value…. From the security and stability of place we are aware of the openness, freedom, and threat of space, and vice versa. Furthermore, if we think of space as that which allows movement, then place is pause; each pause in movement makes it possible for location to be transformed into place.Footnote 54

The year numbers marking the unknown history of the various states thus construct “space” or “plains” to which less human experience is attached. Alternatively, the records with their short and dry narratives mark the known part of history and invite us to pause and read them carefully, so that they become “places” or “slopes.” Of course, readers do not experience that history themselves. Nevertheless, by experiencing textual accounts from earlier times through reading, readers make the table cells containing records into cognitive “places” or “slope” capable of being known.Footnote 55 The readers’ empirical travel on the surface of tables, over the slopes and plains, relies deeply on their textual reading. In this way, the opposition between the two cell types achieves the effect of spatiality in the “Yearly Table.” Spatiality not only makes the tables into sites that allow entry from any direction and easy movement within; it makes the eventful cells of the table into imaginary “slopes” to climb and “places” in which to linger, read, or ponder in the vast “space” of the “plains.” Considering the writing materials of Sima Qian’s time—bamboo slips or silk scrolls, both of which allow for a much wider spread than ordinary book leaves in the Song dynasty—the spatiality the tables could project is even more remarkable.Footnote 56 As a result, this spatiality, like the table’s visual characteristics, contributes largely to its flexibility as a historiography.

Overall, the textual comparison between the “Hereditary House” and the “Yearly Table” supports a tabular mentality that underlies both the chronological tables and the chapters on the hereditary houses of the pre-imperial period. Visually and spatially, the tabular format lends flexibility to this historiography, allowing for an overview of general historical trends through the texts’ density and, with its spatial characteristics, demands the active involvement of the reader, allowing for unlimited possibilities of reading, interpretation, and imaginary “traveling” across the plains and slopes and through space and time.

“Tabulating Everything”: The Spring and Autumn Period in Chun qiu dashi biao

The use of two-dimensional tables in historical writing was the innovation of Sima Qian, likely inspired by earlier charts and lists made for divination, calculation, and record-keeping.Footnote 57 After the Shi ji, two significant works applied the tabular form to the history of the Spring and Autumn Period: Cheng Gongyue’s 程公說 (1171–1207) Chun qiu fenji 春秋分紀 (Separated Accounts of the Spring and Autumn Annals; hereafter Separated Accounts) and Gu Donggao’s 顧棟高 Tables of Major Events (春秋大事表; finished in 1748), works whose methodology and content overlap to the point that a commentator of the Tables of Major Events felt the need to explain that Gu had not plagiarized Cheng.Footnote 58

However, Cheng’s tabulation largely follows the tradition of the Shi ji. Cheng’s Separated Accounts contains subgenres like the Shi ji, including yearly tables, registers of generations and names, treaties, and chronological accounts of domains—all gleaned from the Spring and Autumn Annals and its three traditions. The Separated Accounts tabulates the events of this period and the lineage of noble families and clans, which together occupy around a third of the book.Footnote 59 The rest of the book, categorized by domain, merely summarizes or repeats the narratives of the Spring and Autumn Annals and its traditions, maintaining a conventional narrative form. Regarding the tabular design, the Separated Accounts’ yearly tables are highly similar to those of the Shi ji, with years and states as its column and row headers. For example, the records of the siege of 630 bce in this table have the same text as the “Yearly Table” of the Shi ji but are much shorter.Footnote 60 Therefore, although the Separated Accounts predates the Tables of Major Events, it is the latter that offers a new exploration of the historical tables.

With about one million characters, Gu Donggao’s Tables of Major Events contains fifty tables categorizing the contents of the Spring and Autumn Annals, each with an introduction (xu 敘). The categories include recorded dates of the lunar calendar, territories, cities, noble ranks, topography, battles, annexations, ritual ceremonies, women, and so on.Footnote 61 At the end of some tables, Gu also adds “arguments” (lun 論 or bian 辨) that comment on issues in the tables or debate the opinions of other scholars. At the end of the tables is an atlas containing maps of the domains and waterways in the Spring and Autumn Period.Footnote 62

The Tables of Major Events differs significantly from the format of the “Yearly Table” in the Shi ji in its categorization of content and its methods of tabulation. The Tables of Major Events does not simply expand its categories to include more topics, such as those of rituals, battles, or topography. It extends the application of the tabular form to each of its categories, namely, “tabulating everything” (shi shi biao zhi 事事表之).Footnote 63 Moreover, it applies a different method of tabulation that changes the meaning of the tabular forms in the Tables of Major Events and embeds Gu Donggao’s different thinking into early history. Thus, although the Tables of Major Events undoubtedly benefited from the legacy of the tables of the Shi ji and perhaps also from the Separated Accounts,Footnote 64 it adopts a new methodology for employing the tabular form in historiography. To demonstrate this, I will examine tabulation in the Tables of Major Events through the lens of the Qin and Jin siege of 630 bce and then two battles involving Jin and Chu.

The Tables of Major Events does not place the 630 bce siege in a table focused on Zheng; instead, the siege appears in the “Table of Battles between Qin and Jin in the Spring and Autumn” (春秋秦晉交兵表; hereafter “Qin–Jin Table”; see Figure 4). The cell in which the siege appears contains three layers of text: the main text, an explanatory note attached to the main text, and an editor’s note (an 案). Recapitulating the information from the Spring and Autumn Annals and its traditions,Footnote 65 the main text sketches out the basic elements of this event in a style similar to the yearly tables in the Shi ji, reading: “In the autumn of the 30th year of [Lord] Xi, people of Jin and Qin besieged Zheng” (僖三十年秋,晉人秦人圍鄭). Within the cell, expanding to the left of this main text, are two notes by Gu Donggao. The first note begins with a quotation from the Zuo Tradition and elaborates on the main text:

Zuo Tradition: Zheng sent Zhu Zhiwu to persuade Qin [to retreat], and the Earl of Qin made a covenant with Zheng, sending Qizi, Peng Sun, and Yang Sun to guard Zheng, and returned.

The animosity between Qin and Jin started from this.Footnote 66

左傳:鄭使燭之武說秦,秦伯與鄭人盟,使杞子逢孫楊孫戍之,乃還。

秦晉之隙始此。

Figure 4. “The Qin–Jin Table.”Footnote 75

This note, rendered in a smaller font size, goes on to further summarize the records in the Zuo Tradition and caps off the event in the main text by providing its outcome. The note concludes with an observation by Gu on the deteriorating relationship between Qin and Jin, which neatly falls under the topic of this table, the battles between Qin and Jin. The editor’s note next to the explanatory note reads:

Editor’s note: [Lord] Mu of Qin dispelled his resentment regarding [the battle at] Han,Footnote 67 and then followed Jin in the campaign at Chengpu [to fight Chu]. After that, they made covenants at Wen and Diquan, with Qin following [Jin into] every battle [as an ally]. At that point, Qin suddenly betrayed Jin and made other plans. Although this was because of Zhu Zhiwu’s speech [persuading Qin to retreat], in fact, Lord Mu had harbored resentment toward Jin for refusing Qin and going down the river alone earlier;Footnote 68 he thought on some other day Qin could secretly send out troops to the east [to attack the central plain] and rely on Zheng to coordinate [the attack] with them. Therefore, the saying “the host on his way to the east”Footnote 69 exactly struck a chord in his heart. At this time, although Qin had no intention of plotting against Zheng, it began to harbor the intention of plotting against Jin.Footnote 70

案:秦穆釋韓之憾,而從晉于城濮,嗣後盟于溫,于翟泉,無役不從,至此忽然背晉改圖,雖因燭之武之說,實挾前日辭秦師獨下之憾,以為異日潛師東出,可藉鄭為接應耳。是故東道主一語適中其心曲。此時雖未有圖鄭之心,而已萌圖晉之志矣。

In the editor’s note, besides observing the deteriorating relationship between Qin and Jin, Gu goes back to earlier battles involving Qin and Jin from the perspective of Qin—battles that the previous cells of this table had noted.Footnote 71 In these listed events, although Qin appeared to be a steady ally of Jin (following Jin into every battle), Gu points out that tensions between the two states had been present for years. By connecting and contextualizing the siege in the context of the Qin–Jin relationship, Gu explains that Qin’s sudden retreat was not simply due to Zhu Zhiwu’s speech, but was based on a sophisticated consideration of realistic interests. These two notes and the main text in this table thus go beyond simply annotating the event in the cell, but make an argument based on many other cells in the table; they are part of the “ultra long distance viewpoint” mentioned by Gu.Footnote 72

Moreover, the visual arrangement of this “Qin–Jin Table” in the Tables of Major Events is strikingly different than that of the tables in the Shi ji. Unlike the rectangles in the yearly tables of the Shi ji, which are roughly the same size (see Figures 2–3), the cells in Gu’s table vary in size (see Figure 4). All the notes in a smaller font, whether short or long, are aligned with the main text on the right. Gu apparently did not regulate the length of the notes for each table cell; in some cases, more extensive notes can expand leftwards for pages, leaving other cells with shorter notes blank. This feature makes it difficult to imagine the table as a whole but makes it easy to see at a glance the importance of events, as distinct visual weights are assigned to different cells. The main text, supposedly the core of the table itself, does not contribute to this; however, what makes certain cells stand out are the authorial notes in a smaller font. The visuality of the table thus emphasizes specific cells that embody Gu’s authorial voice.Footnote 73

The tabulation of the “Qin–Jin Table” could also explain these visual features. Although usually regarded as a successor to the yearly tables in the Shi ji, Gu did not create a two-dimensional table here. To take the cell highlighted in Figure 4 as an example, there is only a single vertical header in this table, with an individual cell carrying the information concerning the siege: “[In the autumn of 30th year of [Lord] Xi] people of Jin and Qin besieged Zheng.” Moreover, the five cells, from the top to the bottom of Figure 4, follow a chronological order: the autumn of 630 bce, the summer of 627 bce (fourth month, day xinsi [13]), the spring of 625 bce (second month), the winter of 625 bce, and the summer of 624 bce. In other words, Gu’s table here is one-dimensional rather than two-dimensional and is closer to a list than a “yearly table,” which further explains why it functions differently from earlier tables.Footnote 74

Visual and spatial factors are crucial in the aforementioned two-dimensional tables because they decenter the table cells and allow the reader to explore historical trends from any direction, without a designated beginning or ending point. In the “Qin–Jin Table,” however, the visual presentation signals the significance of the events, with the authorial notes serving as a kind of highlighting marker. With long notes that stretch for pages, the “spaces” or “plains” that could have been created with empty cells (as in the “Yearly Table” by Sima Qian) barely exists in this table. Instead, all cells in Gu’s table become familiar with the help of detailed notes that thus stand for “places” in Yi-fu Tuan’s theory, or the aforementioned “slopes.”

There is no imaginary “traveling” through “space” in Gu’s table; the reader’s eyes move directly from one content-bearing cell to the next, losing the mastery of the overall tabular landscape. The “Qin–Jin Table” is thus more of a tool that readers can only use to search for information if they know, at least vaguely, what they are looking for. If the Shi ji table emphasizes the reader’s agency, then the Tables of Major Events offers a guided, even rigid, reading provided by the author.Footnote 76

If the cells of this table are only “places,” with nowhere for readers to wander around (as in a “space”), how could Gu realize his promise of “an ultra long distance viewpoint” to read the history of the Spring and Autumn Period? In terms of the tabular form, what contributions and insights exist in the Tables of Major Events?

Gu’s first solution for providing “an ultra long distance viewpoint” is to share a textual overview of the Spring and Autumn Period through his own notes, categorizing and numbering historical events. This overview is evident in the “Qin–Jin Table,” where the last passage in the cell for 625 bce (spring) reads: “Qin attacked Jin [for] the first time” (秦伐晋一).Footnote 77 Mirroring this, the last passage of the next cell (625 bce, winter) in this table reads: “Jin attacked Qin [for] the first time” (晋伐秦一).Footnote 78 Numberings like these appear whenever there is a battle between Qin and Jin in this table.

Gu numbers a variety of actions in most interstate tables, including battles and other interactions.Footnote 79 Taking the battles between Jin and Qin as an example, through such numbering, the table cells present the vacillating position of Zheng between the two powerful states, a significant feature of Zheng’s interstate relations during this period. The enumeration at the end of each table cell also facilitates quick checks by allowing the reader to skip irrelevant cells (like the three cells at the bottom in Figure 5). Other categories of interactions can be found in the “Table of Jin and Chu Struggling for Hegemony in the Spring and Autumn” (春秋晉楚爭盟表; hereafter, the “Jin–Chu Table”), including, for example, fa 伐 (to lead a punitive campaign [against]), bi 避 (to avoid), dasheng 大勝 (to triumph over decisively), xiaosheng 小勝 (to triumph over in a smaller way), and zhu 助 (to help; see Figure 5). Through grouping and counting the events, the table provides overviews of various trends in a larger picture, all mediated and highlighted by Gu.

Figure 5. “Zheng Helped Jin Defeat Chu [for] the First Time” in the “Jin–Chu Table.”Footnote 81

Gu’s second solution for providing “an ultra long distance viewpoint” lies beyond the tabular or the usual narrative form. In addition to the tables, maps, and narratives (prefaces or arguments), Gu also includes “impromptu poems” (kouhao 口號) after two tables,Footnote 80 one on topography and strategic passes (referring to the aforementioned battles and relations between Zheng, Jin, Chu, and Qin) and another on five major rituals. The impromptu poems are seven-character rhymed verses with plain wording that has characteristics of doggerel. The significance of these poems with regard to the tabular form in the Tables of Major Events will be illustrated through examining several selected verses.

According to Gu’s introduction to the “Impromptu Poems on Topography of Various States in the Spring and Autumn [Period]” (春秋列國地形口號), he composed 113 verses to summarize his ideas about the “Table of Topography and Strategic Passes of Various States in the Spring and Autumn [Period]” (春秋列國地形險要表) “for the benefit of those who study [the Spring and Autumn Annals] to chant and memorize” (取便於學者之記誦). Although Gu only titles this chapter “Impromptu Poems on Topography,” the verses include content that covers a considerable portion of the entire book, such as the vicissitudes of the states, the non-Sinitic groups, the waterways, and the errors of previous scholars.Footnote 82 Gu also mentions that the impromptu poems are “concise while carrying significance” (簡而居要) and can be “the guide for reading the history [of the Spring and Autumn Period]” (讀史之先路).Footnote 83 Gu’s attempts in the impromptu poems were criticized by his contemporaries, one of whom said that “mixing in seven-character rhyming formulas runs counter to the style of scholarly works” (至參以七言歌括,於著書之體亦乖).Footnote 84 Nevertheless, Gu’s impromptu poems help to complete his tables by providing recapitulations of their contents.Footnote 85 As his impromptu poems summarizing the overall situation of the Spring and Autumn Period at the end of all the verses says:

With Guo destroyed, Jin returned to the West and there was no good news for the Zhou anymore.

With Shen eliminated, the southern tribes began to harbor great ambitions.

In the Spring and Autumn period, Jin and Chu had equal shares of power.

The two states’ vicissitudes wounded Zhou deeply and painfully.Footnote 86

虢滅西歸絕好音,申亡南服啟雄心。春秋晉楚平分勢,兩國存亡痛鉅深。

In other words, Gu believed that the ups and downs of the states of Jin and Chu were the most significant thread in the Spring and Autumn Period, which implied the decline of the Zhou royal house. This is also the core idea of the tables titled “Table of Qin and Chu Contending for Hegemony” (春秋晋楚争盟表) and “Table of Battles between Jin and Chu in the Spring and Autumn [Period]” (春秋晋楚交兵表).

Just as some impromptu poems echo the overall layout of the Tables of Major Events, others outline events in the Tables of Major Events and provide clues to understand the subtle nuances the author hoped to demonstrate through his table. For example, in commenting on the territory of Zheng, Gu writes about Zheng’s diplomatic strategy as a major thread of its history in the period:

Zheng was located in the Central Region, an area open to attacks from the four directions,

Choosing allies for their strength alone is the most favorable plan.

The scoundrels of Gao used this same strategy,

Allowing them to avoid violent conflict and maintain their bit of territory.Footnote 87

鄭界中州四戰區,惟強是擇最良圖。高家賴子同斯術,得免兵戈保一隅。

In this verse, Gu offers a geopolitical explanation for the diplomatic strategy of Zheng, corresponding to the constant warfare between it and the other states mentioned in tables such as the “Qin–Jin Table” and the “Jin–Chu Table.” Moreover, to illustrate Zheng’s situation, he alludes to more recent history of the state of Nanping 南平 during the period of Five Dynasties (907–960) and Ten Kingdoms (902–979). To the left of the verse, Gu annotates why at that time the Gaos of Nanping were known as “scoundrels,” and he comments that by using Zheng’s strategy, Nanping “had no large-scale warfare for five decades and its people were at peace for some time”Footnote 88 (五十年無大兵革, 民以少安). This example also demonstrates how Gu situates the history of early China within a long, continuing historical thread and how he wants the readers to picture its early history through a retrospective lens.

The orality of these rhymed, colloquial verses is in striking contrast to the focus on textuality displayed in the “Qin–Jin Table” and the “Jin–Chu Table.” In these rhyming verses, Gu distills into four rhymed lines the historical trends and topographical features he has identified in the Spring and Autumn Period. Unlike the layered notes in cells that stretch for pages in the “Qin–Jin Table” or the “Jin–Chu Table,” which are meant to convey a large store of information and ready-to-use commentaries, these verses aim to be easily remembered (“to chant and memorize”), echoing the oral circulation of the Spring and Autumn history in its earliest stages. Similarly, his forty-four impromptu poems, attached to the tables on the five major rituals (auspicious, inauspicious, congratulatory, hosting, and military) in the Spring and Autumn Annals and its traditions, each has a longer accompanying text. In these texts, the author expands on the events and viewpoints expressed in the poems, demonstrating that the poems are condensed, oral versions of the longer texts that follow them in the tables.Footnote 89 Thus, although the heavily textual tables make it difficult to see events at a glance, Gu still retains “an ultra long distance viewpoint” in a form that is pithy and memorable enough to enjoy the portability of oral recitation or silent recollection, quite apart from the written text.

In the last of the 113 verses appended to the table on the various states’ topographies, Gu claims that his tables and verses retain the overall view of the Spring and Autumn landscape:

Previously talking about the classic [Spring and Autumn Annals] was like a child’s game: you allow others to say [the territories were] in the east or west at will.

Now looking at the landscapes on paper [in the table of topography], the territorial maps are as clear as using a finger to point to your palm.

往日譚經兒戲同,聽人傳說任西東。而今紙上看形勢,歷歷輿圖指掌中。

By referring to the landscape, the territorial map, and even the allusion of using a finger to point to one’s palm,Footnote 90 Gu argues that he maintains the visuality and spatiality of Sima Qian’s original tables in his own way, through his redesigned one-dimensional tables and impromptu poems.

Overall, by designing tables that are different than those in the “Yearly Table,” Gu’s tabulation is closely tied to his own thoughts on texts regarding the Spring and Autumn Period. Namely, he views events from an “ultra long distance” perspective, focusing on the vicissitudes of states while demonstrating management of textual and historical knowledge on a smaller scale. Similar to Sima Qian’s tabulation of historical events, Gu’s tables can also be understood as an example of the technical arts associated with governance.Footnote 91 In fact, the compilation of the Chunqiu dashi biao was the result of Gu’s dismissal from office in 1723,Footnote 92 and it contains Gu’s expectations for using the knowledge of the Spring and Autumn Period to “manage state affairs” (經世).Footnote 93 Such focus on administration, especially information management, explains well his tabulation’s connection with the kaoju xue 考據學 (evidential scholarship) of his time, which concentrated on textual criticism.Footnote 94 For example, the “Jin–Chu Table” and the “Qin–Jin Table” trace the history of Zheng in the context of its relationship with the more powerful domains of Jin, Qin, and Chu; other tables about Zheng, such as the “Table of Battles between Song and Zheng in the Spring and Autumn [Period]” (春秋宋鄭交兵表), present storylines that are not apparent in the Zuo Tradition or even the “Yearly Table” of the Shi ji.Footnote 95 The meticulous attention to detail, ready-to-use commentary, and visual clarity exhibited in the tabular form are remarkable in Tables of Major Events, as Gu conveys a sense of major historical trends through grouping and serialization of events via textual numbering within the cells and the “impromptu poems,” which go beyond simply “tabulating everything” to comprise tabulation, textuality, and orality at a higher level. Tracing the table design from that of Sima Qian to that of Gu Donggao, one can also easily see the canonization process of the Spring and Autumn Period history at its beginning and its maturity in a larger historiographical context.

Whether leaving the table as an open space for readers to wander through like Sima Qian or delineating interpretations and themes with authorial notations like Gu, the tabular form records historical events and embodies historical thinking in a way that shapes and illuminates conventional historiographies into a much larger corpus of linear narratives. In terms of visuality, spatiality, and orality, the tabular form itself evolves, even as it seems to repeat the old stories of the states in the Spring and Autumn Period, testing the boundaries of the historiography of early China.