1. Introduction

The role of affective variables such as anxiety, motivation, and enjoyment on the learning process and learning outcomes in foreign language acquisition has long been acknowledged. However, despite growing concern about university students’ deteriorating mental health, the relationship between mental health issues and the ways students experience emotions during formal language learning has not yet been explored. This omission implicitly assumes a ‘normative’ learner who is emotionally stable and neurotypical, without chronic conditions. Bringing thinking around inclusivity in higher education into Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) research is not only overdue but allows us to recognise that affective experiences are shaped not only by individual differences, but also by systemic factors of participation, accessibility, and wellbeing. In terms of prevalence, in their systematic review of the factors associated with (poor) mental health of students in higher education Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Blank, Cantrell, Baxter, Blackmore, Dixon and Goyder2022) report that, while in 2018 one in three students with a mental health diagnosis said they needed professional help, in 2020 this increased to one in two. It has also been widely discussed that mental health issues may significantly impact campus students’ academic achievement, progression, and overall study outcomes (e.g. Thorley, Reference Thorley2017). Those who are well-prepared and adaptable to the changes that come with transitioning into higher education – which often means moving out of their parents’ home and living in halls of residence – tend to experience better mental health (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Blank, Cantrell, Baxter, Blackmore, Dixon and Goyder2022). However, there is evidence suggesting that students in online and distance learning who do not have to move to pursue their studies disclose mental health issues at least as frequently as campus students. Lister et al. (Reference Lister, Andrews, Buxton, Douce and Seale2023) report that 7.8% of the students studying at the Open University in the UK – a large online and distance learning provider – disclosed a mental health condition, compared to the UK higher education average of 5.8%. In 2022, Student Minds, a mental health charity, reported much higher numbers: 27% of respondents had a diagnosed mental health condition (Lewis & Stiebahl, Reference Lewis and Stiebahl2024). In 2023/24, 24.5% of students at the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University (OU) declared mental health conditions and there was a 13.6 percentage point gap in module completion for them. The significant impact that mental health difficulties have on campus university students’ academic self-efficacy and study progress is well attested (Grøtan et al., Reference Grøtan, Sund and Bjerkeset2019). In the online context, based on data from 8,472 students on beginner and pre-intermediate language modules in the academic years 2022/23 and 2023/24, the average difference in scores on tutor marked assignments was only 3.8 points (81.8 for students with no declared disability and 78 for students with declared mental health conditions), however, the submission rate of the assignments was 78.2% versus only 68.4%. That is, students with mental health conditions who actually submit their assignments score more or less as their peers without mental health problems, but they are much less likely to submit. Looking at written assignments only, the difference in submission rates is 7.6% (82% vs 74.4%; average scores 82.8 vs 79.5). Interactive spoken assignments show a very different picture: only 59% of students with mental health conditions complete these assignments (their average score is 73.2), while 72.6% of their peers with no additional needs do so (score 77.5). It is not hard to see how detrimental an effect this can have on students’ academic progression. Examining how learners with mental health conditions experience foreign language speaking anxiety (FLSA) and the techniques they use to manage can therefore provide valuable insights for fostering inclusivity in online learning contexts, particularly in the UK where language learning appetite remains limited despite its significant employability advantages (Association of Translation Companies, 2023).

While the shift to online (language) learning has expanded access and flexibility for many learners, it also introduces conditions that may amplify or attenuate affective challenges such as FLSA, particularly for students with mental health conditions. On one hand, the online format may reduce anxiety for some learners by offering greater anonymity, fewer immediate social pressures, and the option to engage asynchronously. On the other hand, it may amplify anxiety through increased feelings of isolation, reduced access to nonverbal cues that aid communication, and greater demands for self-regulation. For students with anxiety, depression, or related conditions, these structural affordances of online learning may interact in complex ways with their emotional and cognitive profiles, influencing how they experience and manage FLSA.

2. Foreign language speaking anxiety in online learning

Few studies compare FLA in online and face-to-face (f2f) learning. Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Song and Chiu2020), using Second Life, and Báez-Holley (Reference Báez-Holley2013), with beginner online Spanish learners, found no significant anxiety differences between online and f2f groups. However, other studies suggest f2f students tend to be less anxious. For instance, Bollinger (Reference Bollinger2017) found lower anxiety in f2f classes among 147 community college language learners in Georgia, USA. Simsek and Capar (Reference Simsek and Capar2024) observed similar results among 234 Turkish ESL university students. Lisnychenko et al. (Reference Lisnychenko, Dovhaliuk, Khamska and Glazunova2020), examining 38 Ukrainian students forced into online learning due to Covid, reported higher communication apprehension and fear of negative evaluation online, despite greater comfort with mistakes. This forced transition into online learning, like that in Resnik et al. (Reference Resnik, Dewaele and Knechtelsdorfer2022), may have amplified anxiety and negative attitudes toward language learning.

Online language learning presents unique challenges and opportunities compared to f2f settings (e.g. Gacs et al., Reference Gacs, Goertler and Spasova2020). Pichette (Reference Pichette2009) notes that students with high Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) may opt for online courses to benefit from anonymity. Nevertheless, students with ADHD and specific learning difficulties report having a less positive perception of distance learning, lower academic self-efficacy and sense of coherence, and higher levels of loneliness than their peers without disabilities (Sharabi & Shelach Inbar, Reference Sharabi and Shelach Inbar2024). Sun’s (Reference Sun2014) qualitative study with 46 Chinese learners identified key difficulties in online learning, including time management, engagement, collaboration, socialisation, and maintaining motivation and self-direction. At the same time, effective language learning requires active participation and interaction, meaning online learners must engage in speaking activities, collaborate with peers, and maintain resilience and self-discipline to stay on track.

Although to the best of our knowledge there are no studies explicitly focusing on foreign language classroom emotions experienced by students with mental health issues, there is a growing interest in how learners’ personality traits predict the ways they experience these emotions (Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2022) and ultimately their learning outcomes. While results are inconclusive regarding the predictive power of personality traits on FLA, Botes et al. (Reference Botes, Dewaele, Greiff and Goetz2024) show that students with neuroticism or general anxiety are more likely to experience FLA, but we do not know whether they experience it in a similar way to students with other personality traits. Neither do we know how students with mental health difficulties experience FLA and specifically speaking in their target language. This research seeks to fill an important gap in our knowledge by finding answers to the following specific research questions:

1. How do the triggers for FLSA in synchronous online university language tutorials differ between students with mental health conditions and those without additional needs?

2. What are the key differences in FLSA management strategies between students with mental health conditions and those without additional needs in online university language learning contexts?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

This study was conducted at the Open University, a major provider of online and distance education where language courses are developed using the latest theoretical approaches and research-informed pedagogies specifically tailored for online learning. Language modules are delivered in a blended format that combines asynchronous activities with optional synchronous sessions, including self-paced online activities, peer interaction through forums, wikis and meetings in online rooms, and tutor-led group tutorials. However, establishing lasting connections can be difficult, as students can attend any tutorial sessions they wish, which means they may not encounter the same peers or tutor each time. Given that all modules are delivered in an online format, and that the online context poses unique affective and social challenges, this setting offered a relevant environment to investigate the interplay between mental health status and FLSA.

There were 307 undergraduate students in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics who responded to the survey, aged 18 and over, of which 262 were eligible to participate in this study. This was the same data collection event as described in Bárkányi and Brash (Reference Bárkányi and Brash2025). The majority of students combine part-time study with employment. To comply with research ethics and data protection, students were provided with an outline of the study, prior to data collection with the approval of the OU Research Ethics Committee (HREC/4164).

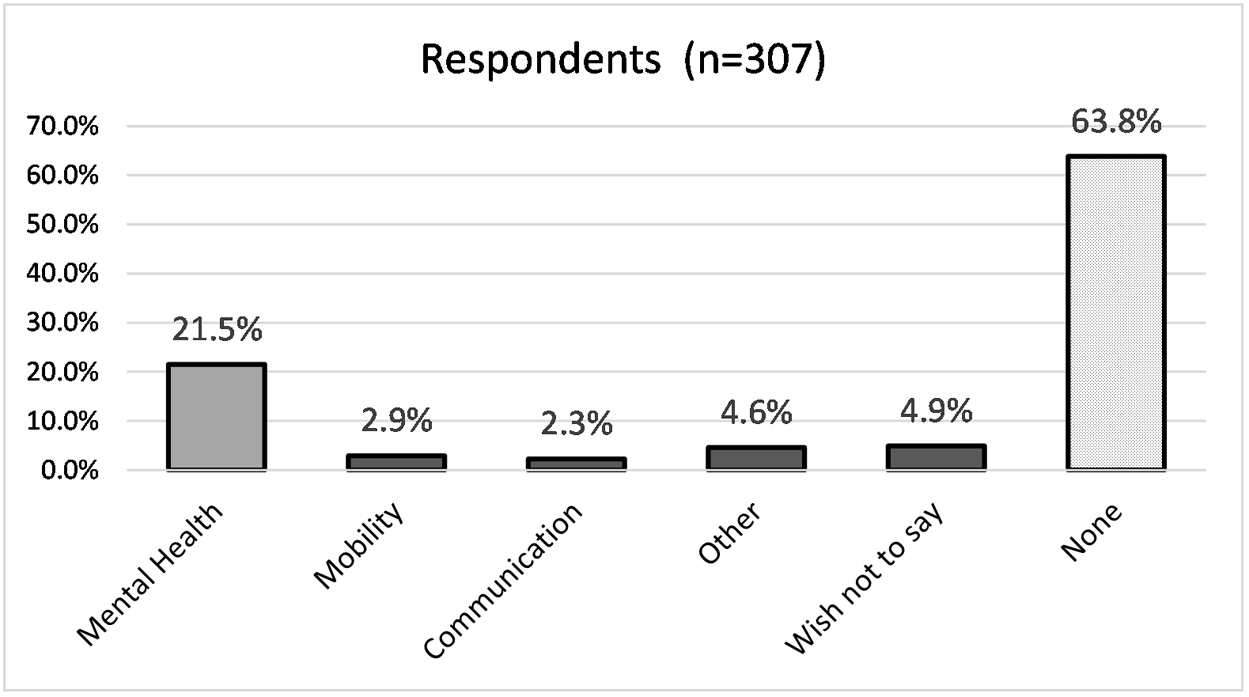

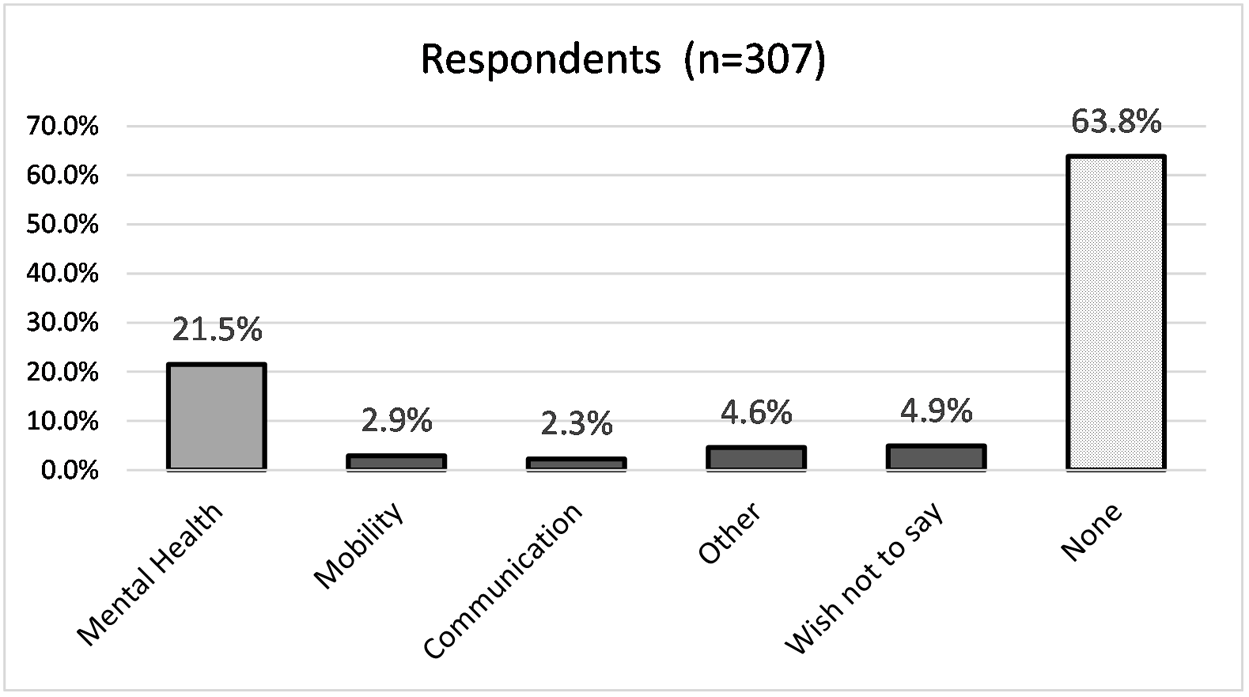

The demographic part of the questionnaire also enquired about students’ additional needs (Do you consider that you have additional requirements that may impact on your study?). Students could answer No, Yes, and I wish not to say. If they answered ‘yes’ they were prompted to specify. On the basis of their answer the following categories were established (Fig. 1):

1. Mental health issues (e.g. depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, etc.)

2. Mobility issues (e.g. use of wheelchair, awaiting knee surgery)

3. Communication and interaction needs (e.g. dyslexia, hard of hearing)

4. Other (e.g. ‘I’m a single mum with two young children’)

5. Wish not to say

6. No additional needs

Figure 1. Distribution of respondents based on their additional needs.

Note that mental health status in this study was self-reported, and no formal diagnostic instrument or clinical verification was used, in line with the ethical considerations of the study and the anonymised nature of the survey. This is also in line with institutional policies at the OU for study support and assessment purposes. While mental health exists on a continuum and many conditions are heterogeneous in severity and impact, for the purposes of comparison, two broad groups were established: students declaring mental health problems (Group MH; n = 66) and those reporting no additional needs (Group None; n = 196). We acknowledge that this binary classification simplifies a complex spectrum of psychological experiences. However, it provides a starting point to explore potential differences in FLSA-related barriers and coping techniques across groups. Eleven students declared multiple different types of needs. If a mental health issue was among them, we categorised it as such. Intersectionality and comorbid conditions were not systematically analysed and are recognised as limitations of the present study.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

The study employed a mixed-methods approach carried out in sequential phases. Data collection followed the same procedures as in Bárkányi and Brash (Reference Bárkányi and Brash2025). In December 2021, a questionnaire containing both closed- and open-ended questions was sent to 999 languages students to explore their perspectives on FLSA and to identify its main causes, as well as to understand their coping strategies. Qualitative data were gathered from open-ended questions of the questionnaire. More information on each question is given in the Results section. Quantitative data came from closed questions with single and multiple-choice answers. The questionnaire design was informed by insights from two prior interventions in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics, attended by 88 students. Given that the questionnaire required approximately 20 to 30 minutes to complete, three Amazon vouchers per language (Spanish, French, German) were raffled among students to encourage participation. A total of 307 responded, reflecting a strong 30% response rate, highlighting the relevance of this topic for language learners. A limitation of the study is that it conceptualises anxiety as a static affective characteristic. We did not measure the intensity of anxiety, and all data is self-reported rather than based on physiological measures or behavioural observations, although research shows that there is a closely correlation between learners’ self-reported FLA scores and physiological indicators such as heart rate and skin conductance (MacIntyre & Gregersen, Reference MacIntyre and Gregersen2021).

Within the questionnaire, students could volunteer for additional research via four Group Interviews (GIs) each lasting around 60 minutes, intended to gain deeper insights into the fears and coping strategies of students with and without mental health issues. The GIs were conducted between February and June 2022 in English only and were conceptualised and presented to students as interventions where coping strategies were elicited and discussed, and students could then apply these to their upcoming tutorials and discuss their impact in subsequent GI sessions. Applications were received from 108 students to take part in GI sessions and 10 students were selected. Selection criteria included an even spread across the three languages (Spanish, French, German), levels of languages (beginners’ level/level 1, level 2, and level 3) and even distribution of students who declared additional needs, those who reported FLSA, and those who did not. The four GI sessions were moderated by three tutors who were briefed so that they could facilitate but would influence discussions and approaches to mitigating FLSA as little as possible. In a fifth GI session tutors and the research team met to discuss results and insights.

In order to address the two research questions, this paper primarily focuses on quantitative data which is supported and explained in more depth with the help of the qualitative data from both the questionnaire and the five GI sessions. All quantitative data were transferred to Excel for the initial calculations. Inferential statistics were carried out in SPSS13. To identify the differences between the two learner groups and the main triggers of FLSA we applied chi-squared tests. For the comparison of the answers by the two groups of students to Likert questions, the Mann-Whitney test was applied. We opted for this non-parametric test as it does not require the underlying distribution to be normal, the z-score value is reported when the distribution is approximately normal. Data from open-ended questions and GI sessions were transcribed to undergo template analysis (King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012), but only a limited set of these data are presented in this paper as mentioned above. This method of data analysis was chosen as it ensures consistency and rigour in data interpretation. Four first level codes were derived: context, experience, perceived cause and strategies. The code context captured the situational and environmental dimensions of FLSA (e.g. synchronous tutorials, breakout rooms) reflecting the contextualised nature of language anxiety. Experience drew on affective and phenomenological perspectives on language learning (e.g. Dewaele & Li, Reference Dewaele and Li2020) to capture students’ lived emotional encounters with speaking. Perceived cause aligned with theoretical constructs such as self-efficacy, fear of negative evaluation, and confidence, that is, central elements in FLA theory (Horwitz et al., Reference Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope1986), while strategies reflected the behavioural, cognitive, and avoidance coping mechanisms learners employed to manage anxiety (e.g. MacIntyre & Gregersen, Reference MacIntyre and Gregersen2012; DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser, Loewen and Sato2017). The template was iteratively refined in line with King’s (Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012) approach. This allowed theoretical constructs such as fear of negative evaluation, coping regulation, and so on, to guide interpretation while also remaining open to emergent, context-sensitive themes. All coding was carried out in NVivo12.

4. Results

In this section we first present quantitative and qualitative data that provide answers to our first research question relating to triggers for FLSA, then present data that addresses our second research question relating to coping strategies in synchronous online tutorials.

RQ1: How do the triggers for FLSA in synchronous online university language tutorials differ between students with mental health conditions and those without additional needs?

First, we focus on students’ feelings and worries regarding speaking in general. We start with those triggers that both groups – students with declared mental health conditions (Group MH) and students without additional needs (Group None) – ranked high. Then, we proceed to compare how the main worries of the two groups differ. Chi-squared tests were carried out, if in either of the groups around 10% of the respondents chose the answer as their main trigger of FLSA. After that we present data relating to FLSA in synchronous online tutorials.

4.1. Feelings and worries regarding speaking in general

4.1.1. Similarities between the groups

When asked what the principal worry is when they speak in their target language (single choice – options based on earlier interventions), there were some striking similarities between the groups. The highest-ranked worry for both groups was that they could not remember the vocabulary although they knew it. This option was selected by 18.9% of Group None and 18.2% of Group MH (χ2(1, N = 262) = 0.016, p = 0.9, Cramer’s V = 0.008). This has been cross validated in the Likert data ‘I feel confident that I can easily use the vocabulary that I know in a conversation’ where a Mann Witney test was carried out and the results were not significant either (U = 5580, z = 1.612, p = 0.107, r = 0.1). It is also confirmed by tutors in the fifth GI session who remarked:

Another thing that came in the way of fluency and caused anxiety in a similar way to pronunciation was […] remembering vocabulary and being worried about not remembering a word and you got stuck […], vocabulary was another important area. More than grammar.

Two further options showing no significant differences between the groups were ‘Everyone else is better at speaking’, selected by 12.8% in Group None and 9.1% in Group MH (χ2(1, N = 262) = 0.636, p = 0.425, Cramer’s V = 0.049), and ‘I do not worry,’ selected by 10.7% in Group None and 9.1% in Group MH (χ2(1, N = 262) = 0.14, p = 0.708, Cramer’s V = 0.023), which means that students with mental health conditions are as likely to experience FLSA as students with no declared needs or disabilities.

4.1.2. Main worries for Group None

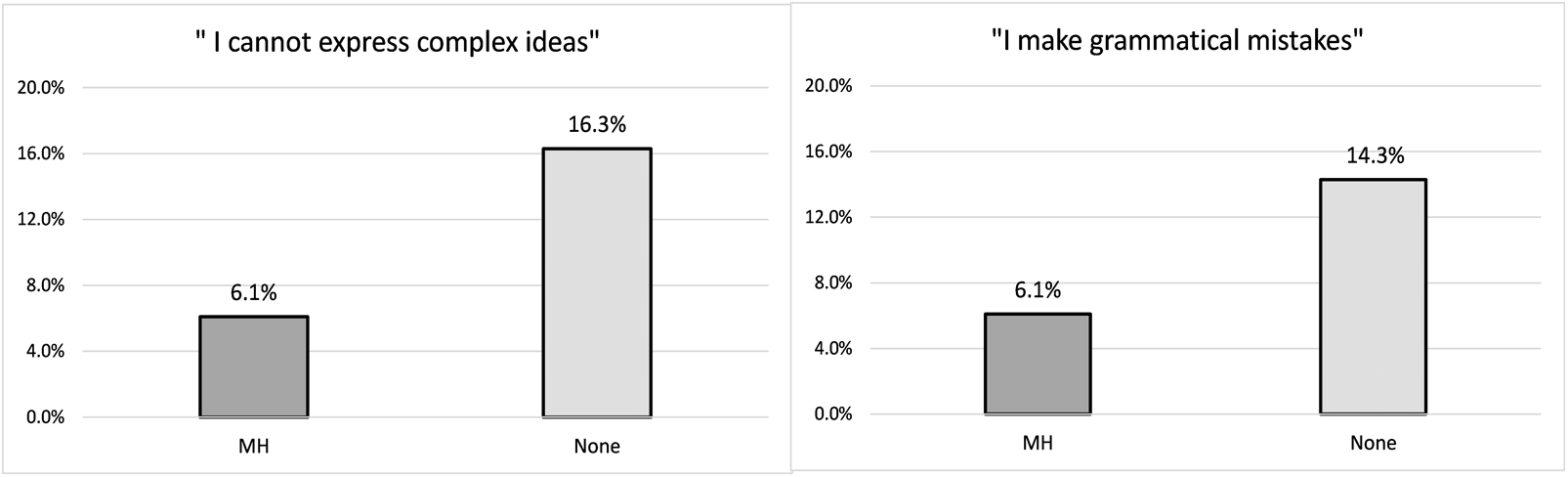

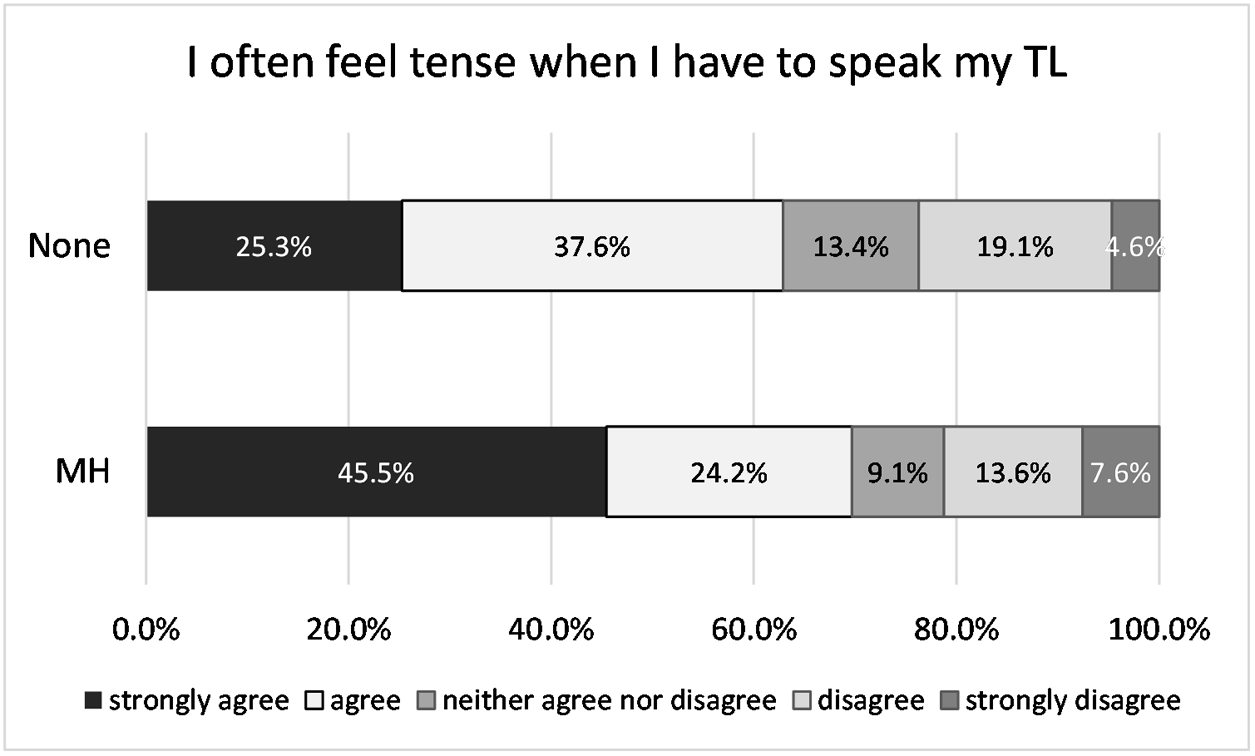

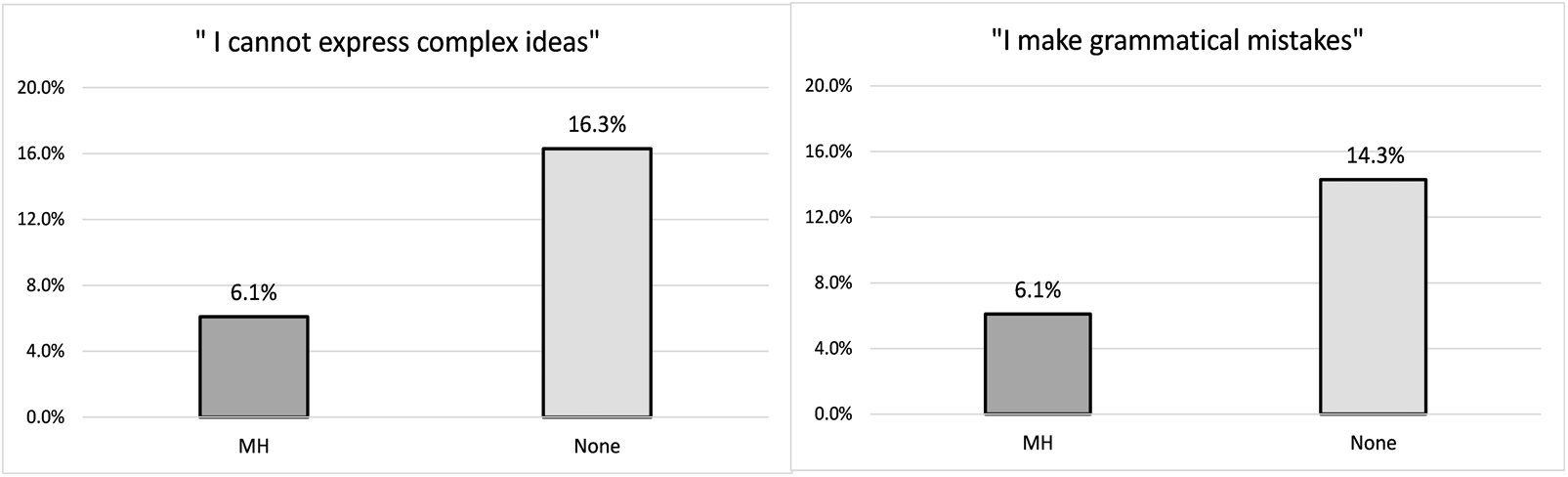

The biggest worry for Group None that significantly differed from Group MH was not being able to express complex ideas when speaking in the target language. While 16.3% of Group None selected this option, this was a main worry for only 6.1% of Group MH, as illustrated in Figure 2 (χ2(1, N = 262) = 4.39, p = 0.0361, Cramer’s V = 0.129).

The second biggest such concern in Group None was making grammatical mistakes, selected by 14.3%, but this was again not a frequently chosen trigger for Group MH (6.1%), as can be seen in Figure 2. The results are not statistically significant, but reveal a tendency (χ2(1, N = 262) = 3.11, p = 0.077, Cramer’s V = 0.109).

Figure 2. ‘I cannot express complex ideas’/‘I make grammatical mistakes’ (single choice).

4.1.3. Main worries for Group MH

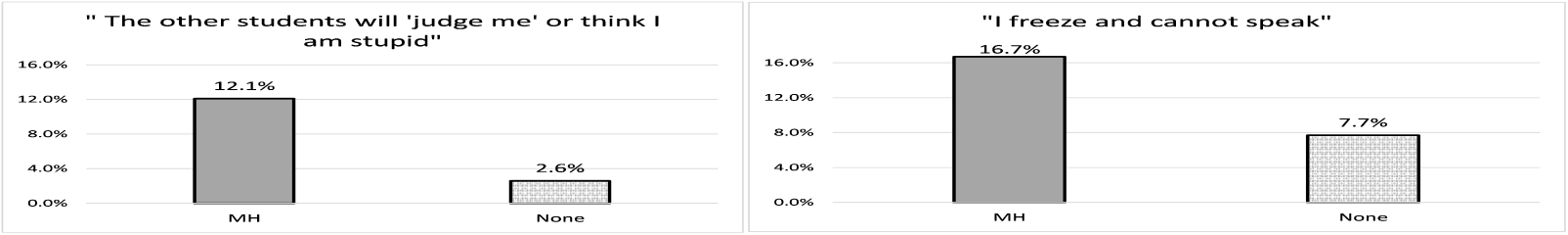

On the other hand, the main worries for Group MH, significantly different from Group None, was their perception that other students would ‘judge’ them or think they were stupid, selected by 12.1%. That did not seem to worry Group None as much, selected only by 2.6%, as illustrated in Figure 3 (χ2(1, N = 262) = 9.59, p = 0.002, Cramer’s V = 0.191).

Figure 3. ‘The other students will “judge me” or think I am stupid’/‘I freeze and cannot speak’ (single choice).

This was validated in the GI sessions as well, for example:

… everyone else is judging me […] it all leaves my head and I just don’t know what I’m saying or what I’m doing and then it’s frustrating and you ruminate on it for the rest of the day.

And ‘I freeze and cannot speak’ was selected by 16.7% of Group MH, but only 7.7% of Group None (Fig. 3) (χ2(1, N = 262) = 4.49, p = 0.034, Cramer’s V = 0.131).

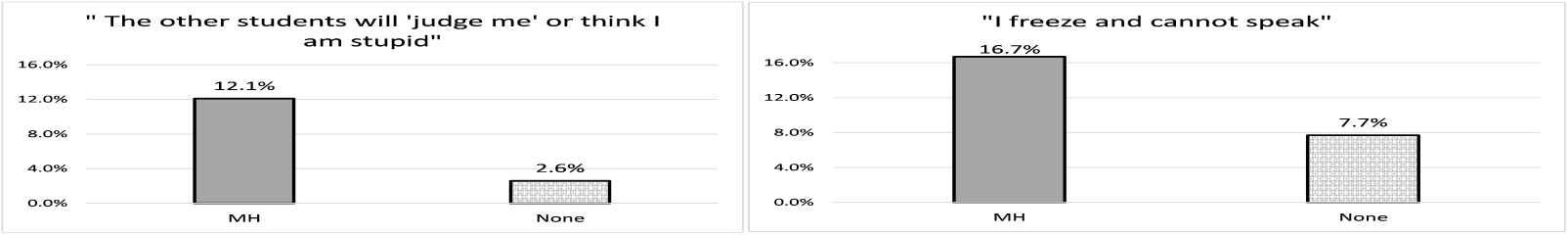

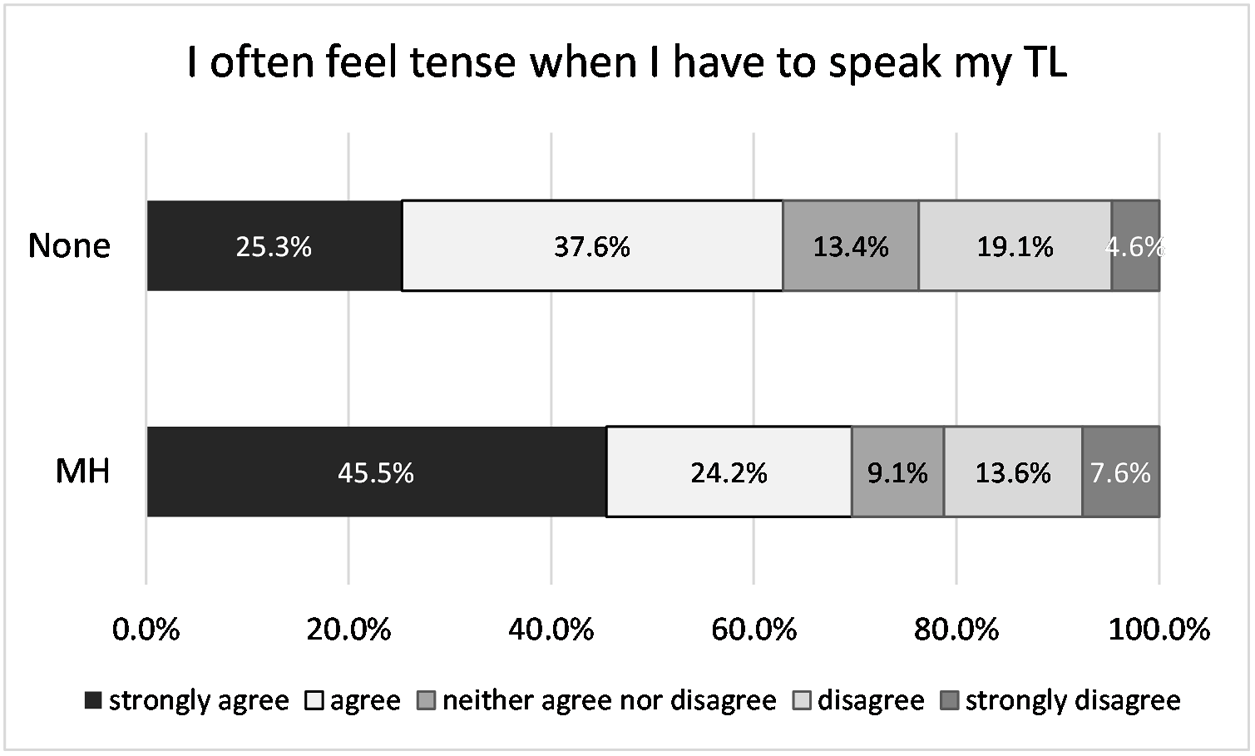

Based on Mann-Whitney test, there were also significant differences between both groups when asked to rank the following statements on a Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree):

I often feel tense when I have to speak my target language.

I am anxious about spoken assignments.

Nearly half of Group MH (45.5%) strongly agreed that they often feel tense when they have to speak in their target language, in comparison to only 25.3% in Group None, as illustrated in Figure 4. A Mann-Whitney U test was performed to evaluate whether the difference is statistically significant. Results indicated that students in the MH group feel significantly more tense than students without additional needs, even if the effect size is small here too: U = 5359, z = 1.975, p = 0.047, r = 0.12).

Figure 4. Ranking of ‘I often feel tense when I have to speak my target language’.

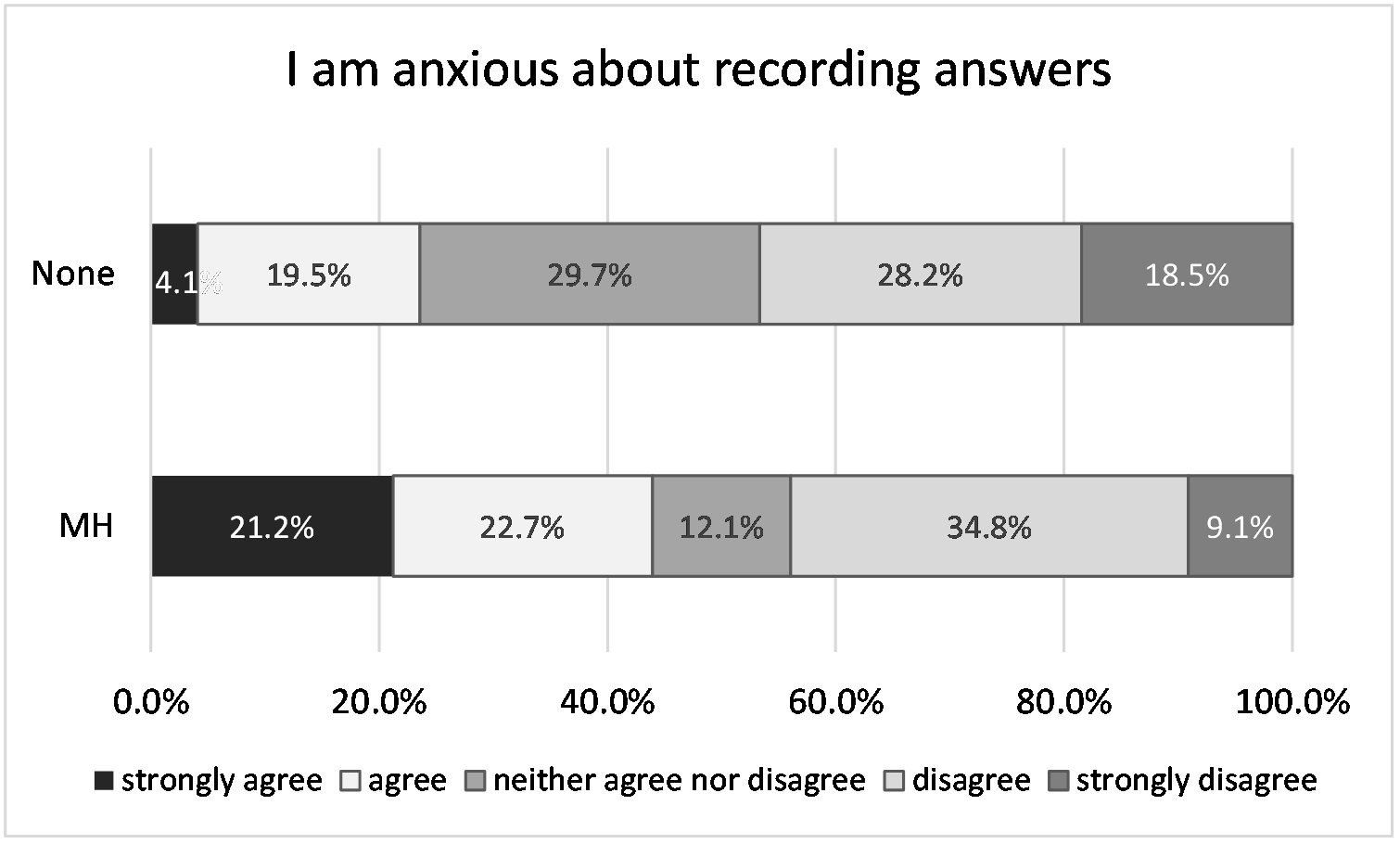

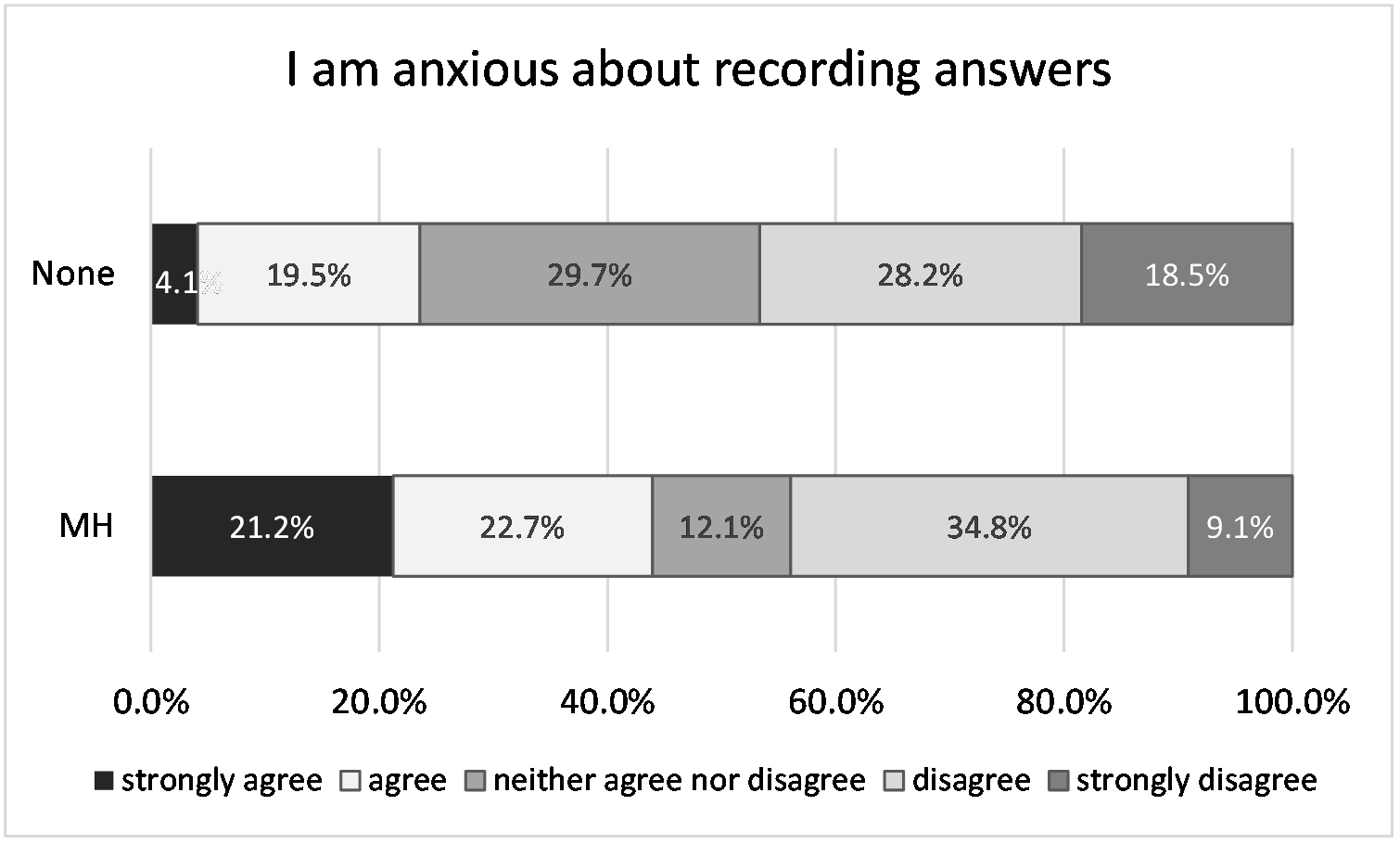

Spoken assignments are experienced very differently: Group MH 36.4% agree strongly that they are anxiety provoking, compared to 15.8% in Group None, as illustrated in Figure 5; the difference is highly significant, though the effect size is still small (U = 4302, z = − 4.066, p < 0.0001, r = 0.25).

Figure 5. Ranking of ‘I am anxious about spoken assignments’.

4.2. Feelings and worries about speaking in tutorials

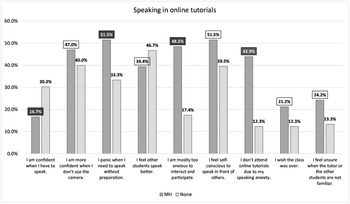

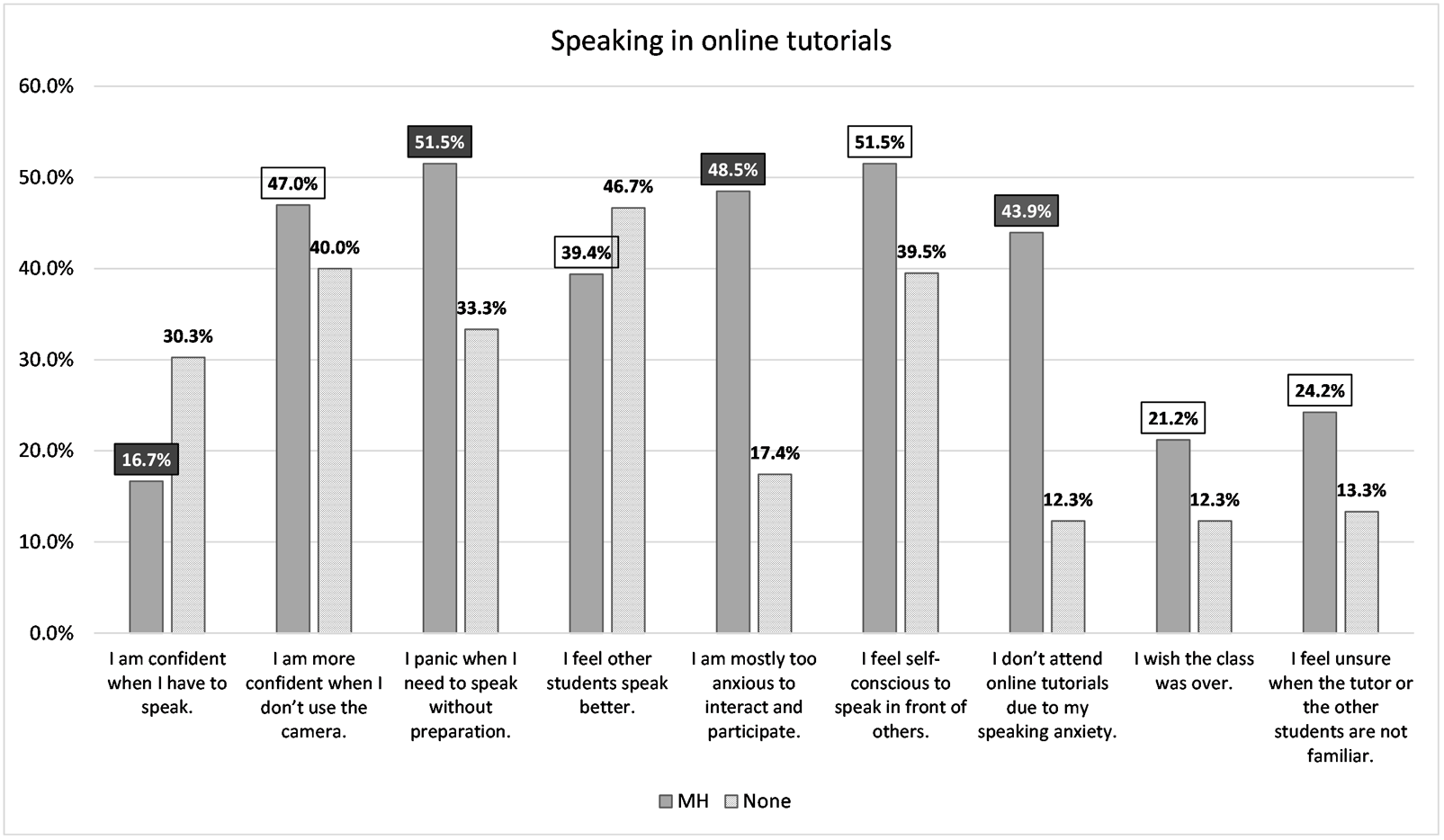

When asked to select all statements regarding speaking in online tutorials that apply, there were also substantial differences (black label) between both groups (Fig. 6). For those questions where participants could choose as many options as they liked only descriptive statistics are presented.

Figure 6. ‘Choose as many statements with regard to your speaking in online tutorials as apply’.

Students in the two groups have very different feelings regarding real-time interaction in tutorials. Only 16.7% of Group MH feel confident when they have to speak, compared to 30.3% in Group None (in line with Fig. 4). Furthermore, 51.5% of Group MH panic when they need to speak without preparation, compared to 33.3% in Group None (also Fig. 3). The differences regarding spontaneous speech are also substantial. In Group MH 48.5% consider themselves too anxious to interact and participate, compared to 17.4% in Group None. Almost half of the students within Group MH (43.9%) report that they do not attend tutorials due to their speaking anxiety, compared to 12.3% in Group None.

There are further noticeable differences (white label) between both groups – 47% of Group MH feels more confident in tutorials when they don’t use the camera, in comparison to 40% in Group None. Interestingly here, 46.7% of Group None felt that other students spoke better in comparison to only 39.4% in Group MH. In Group MH, 51.5% feel self-conscious to speak in front of others, compared to 39.5% in Group None; with 21.2% of Group MH wishing the class was over, compared to 12.3% in Group None. About a quarter of Group MH (24.2%) feel unsure when the tutor or the other students are not familiar, compared to about a seventh in Group None (13.3%).

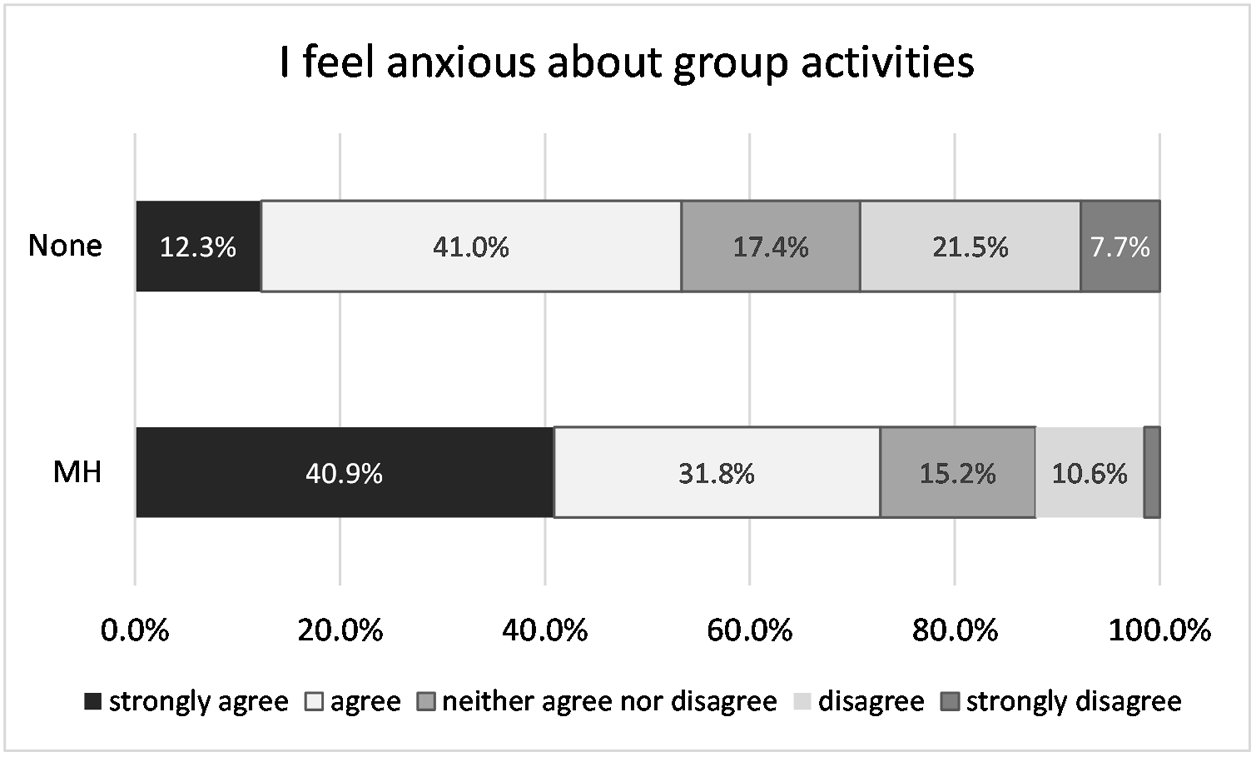

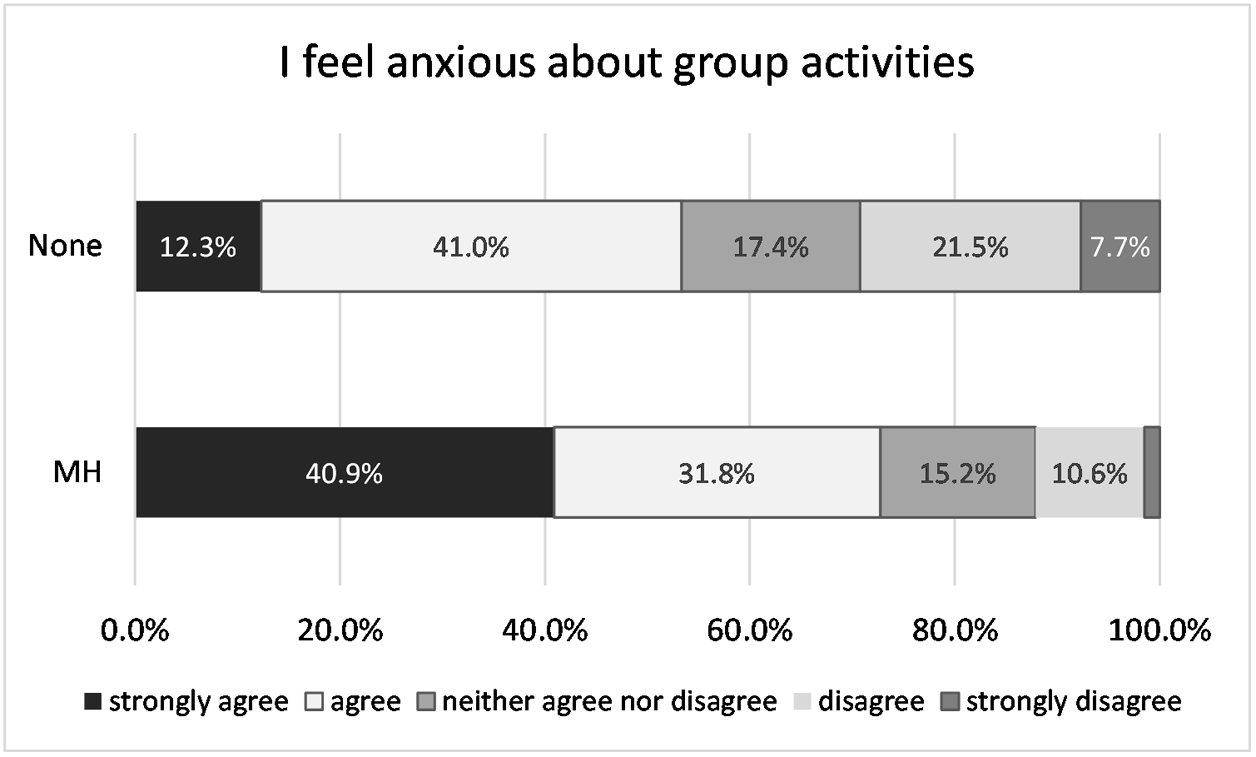

In Group MH 40.9% also feel more anxious about group activities in tutorials compared to 12.3% in Group None (Fig. 7) – the results indicate that the difference is highly significant (U = 4178.5, z = − 4.255, p < 0.0001, r = 0.26).

Figure 7. Ranking of ‘I feel anxious about group activities’.

When asked further to describe their feelings in online tutorials, the qualitative data suggests that Group MH viewed the other participants in the tutorial as a critical and judging audience, particularly in relation to making mistakes, for example:

I once spoke and didn’t like how I sounded, so I have avoided speaking since then. My colleagues are also perfect, which makes me uncomfortable because I assume they are laughing at me in the background. I also don’t want my tutor to think I am stupid.

I do not want anyone other than the tutor to hear me talk as I get very nervous with them [other students] and I get worse when there’s more people.

In comparison, Group None felt more positive about making mistakes in front of other students in online tutorials:

I don’t care if I’m not perfect and mess up in front of everyone.

However, both groups expressed their concern at tutorials being a place where students compare themselves to others, as illustrated by the following quotes:

I feel that I am under constant evaluation and criticism even when there is no basis for that. (Student in Group None)

However, for some reason, making mistakes when learning to play an instrument, sport, or whatever skill that one would enjoy isn’t as fearful or paralyzing as when it comes to speaking a foreign language. I feel like an impostor playing a spy game, and everyone can see through my façade. (Student in Group None)

I feel inadequate compared to others. (Student in Group MH)

I still feel intimidated when there are others who speak better than me. (Student in Group MH)

This discomfort is amplified for students with mental health issues when they are moved into breakout rooms. When asked to describe their feelings in online tutorials, Group MH noted:

I find breakout rooms, particularly those with a relatively open topic of conversation, very anxiety-invoking.

I really struggle with being split into small groups. I feel a lot more exposed in a small group.

When quantifying the recurring feelings towards online tutorials in the qualitative data, it was interesting to see that 9 of 161 students in Group None who replied said they feel happy or content in online tutorials whereas no students in Group MH reported feelings of happiness or contentment.

I am happy to be able to practice the language although I often realize I still have a lot to improve.

Feel happy and supported to just have a go.

I love to speak and practice my target language.

The second research question examines how students manage real-time speaking. First, we look at how students prepare for speaking in tutorials, followed by an overview of their strategies during synchronous online sessions.

4.3. Preparing for speaking in tutorials

RQ2: What are the key differences in FLSA management strategies between students with mental health conditions and those without additional needs in online university language learning contexts?

When asked how they prepare to participate in tutorials, Group None seems to be more willing to attend tutorials unprepared: while 27.3% of Group MH do not prepare, this is much higher in Group None with 37.1%. Group MH is also more likely to ask the tutor for materials in advance to help prepare (4.5% as compared to Group None 1.5%). Practising out loud is a common way to prepare for all students, while they are much less likely to seek support from or practice with their peers (see also Bárkányi & Brash, Reference Bárkányi and Brash2025). When prompted to further elaborate, their replies revealed notable differences in approach between the two groups.

Students in Group None frequently described engaging with materials in advance to build confidence before tutorials. They rarely mentioned avoiding tutorials and no respondents used calming or relaxation techniques to prepare for tutorials.

I listen to podcast and watch movies. I listen to music in my target language. I practice my speaking with native speakers.

I read over recent materials and revise verb conjugations.

In comparison, the most frequently mentioned strategy by Group MH was avoiding tutorials, giving further explanations such as:

I avoid going to tutorials and try to focus on finding native speakers online.

Stick my head in the sand and hope it goes away.

I don’t attend because of the anxiety of working in small groups with strangers.

While instead of using the course materials, they were looking at calming or relaxation techniques to prepare for the tutorial, as for example:

I visualise […] myself speaking fluently. I practise calming techniques.

No student in this group reported attending a tutorial without preparation.

4.4. Speaking strategies in tutorials

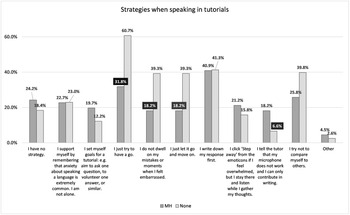

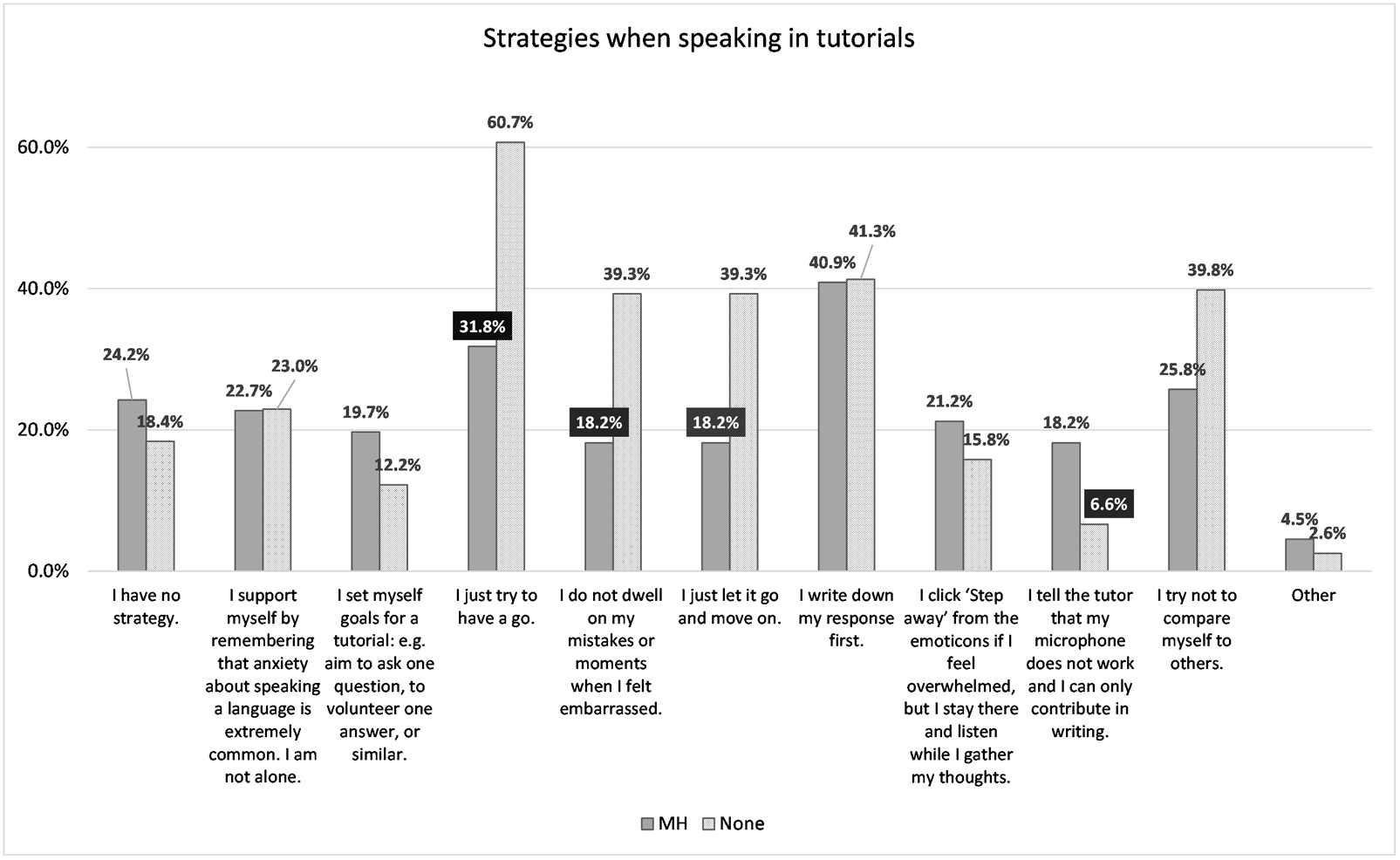

As for managing speaking during tutorials, there are several notable differences between students with mental health problems and students without additional needs (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. ‘Which of the following strategies do you use if you have to speak in tutorials? Please choose all that apply.’

The most used strategies for Group None were to just try to have a go speaking the target language in a tutorial, which 60.7% of students reported, followed by writing down their answers first (41.3%), trying not to compare themselves to others (39.8%), not dwelling on their mistakes (39.3%), and just letting mistakes go and moving on (39.3%). In comparison, Group MH’s most used strategy was writing down their response first, which 40.9% of students reported, followed by not trying to compare themselves to others (25.8%), supporting themselves by remembering that anxiety about speaking a language is extremely common and they are not alone (22.7%). About one quarter of students in Group MH reported not having a strategy (24.2%).

Nearly twice as many students in Group None try to have a go at speaking the target language in a tutorial, compared to Group MH. Students in Group None are also about twice as likely not to dwell on mistakes and to just let them go and move on, when compared to students in Group MH. On the other hand, students in Group MH were three times as likely to tell the tutor that their microphone did not work and that they could only contribute in writing compared to students in Group None.

When asked to elaborate further, students in Group None also reported the following strategies:

I don’t compare myself to others, dare to make mistakes and move on and always have a go irrespective of the situation.

I just do it, my tutor is very supportive so I am not scared to make mistakes.

I keep relevant materials and a dictionary beside me for reference.

I try to talk as much as I can. When I make mistakes I take it as a chance to learn and improve.

Students in Group MH also used the following strategies:

I contribute as much as possible and if I made mistakes, I apologize and carry on.

We’re learning.

I don’t attend them [the tutorials].

5. Discussion

This is the first study to examine how students with mental health conditions experience FLSA and to what extent this differs from the experiences of those languages students who have no additional needs. Although we found differences in barriers, the small effect sizes and the barriers in common advocate for a continuum-based approach of varying degrees of vulnerability and resilience rather than a dichotomy between the examined groups.

The results presented here provide new insights about a missing aspect of FLA research, and we will view the implications of these findings through the lens of the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Guidelines 3.0 (CAST, 2024). This educational framework is grounded in neuroscience and educational psychology and understands learner variability as systematic and predictable, thus highlighting the need for proactive instructional design rather than reactive accommodation of learner differences. Based on the three interrelated principles of means of engagement, representation, and action/expression, UDL 3.0 promotes an equitable, flexible, and culturally responsive pedagogy. This framework is particularly helpful for our results as it focuses on the learning environment rather than on the learner and aims to remove barriers that can often exacerbate both FLA and mental health-related difficulties.

5.1. Vocabulary retrieval

The main trigger of FLSA for both groups was ‘not remembering vocabulary’ students think they know. The negative correlation between vocabulary anxiety and willingness to speak as well as productive vocabulary knowledge and learners’ anxiety levels has been demonstrated (e.g. Izadi & Zare, Reference Izadi and Zare2016). Vocabulary knowledge has also been shown to account for most of the variation observed in L2 listener’s listening test scores (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2022). The development of proficient listening comprehension serves as a driving force for effective communication, and as such is closely linked to spontaneous speaking situations. Most studies exploring the link between listening comprehension and vocabulary knowledge focus on form-meaning mapping, that is, declarative phonological vocabulary knowledge. Our findings suggest that the participants of this study may have substantial explicit vocabulary knowledge, but they might struggle with accessing it quickly, consistently, and automatically. This is in line with the skill acquisition theory for instructed language learning (DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser, Loewen and Sato2017) which clearly differentiates between declarative knowledge (knowing what) and procedural knowledge (knowing how). According to this theory, acquisition occurs in three main stages: declarative, procedural, and automatic. At the declarative stage learners know what the word means and what its form is, but to understand or produce it involves conscious effort (and typically relies on explicit instruction). At the procedural stage learners can use the word in context and it requires less effort, while at the automatised stage learners are able to understand and produce vocabulary without conscious effort. In Saito et al.’s (Reference Saito, Uchihara, Takizawa and Suzukida2024) study automatised knowledge of vocabulary correlated with the age at the onset of learning (besides practice with listening activities and language immersion experiences). Since our participants are adult learners who typically started learning at the OU ab initio or as false beginners in non-immersion context, they have not yet managed to transition from declarative knowledge to procedural/automatised knowledge, which seems to cause considerable anxiety for them and thus prevents practice that is essential for automatisation. The inability to access known vocabulary aligns with cognitive load theory (Chen & Chang, Reference Chen and Chang2009), where anxiety consumes working memory resources needed for language processing. This may be compounded with emotion regulation demands, creating a ‘dual-task’ cognitive burden. The ‘freeze mode’ reported by students connects to the polyvagal theory (Porges, Reference Porges1995) where the speaking situation is a perceived social threat that activates neurobiological safety systems and triggers a fight, flight, or freeze response (Sawyer & Behnke, Reference Sawyer and Behnke2002). This means that vocabulary retrieval problems may have different – although overlapping – underlying mechanisms from lack of automatisation to a complete freeze response.

In terms of actionable changes, from a UDL 3.0 perspective online language course designers should consider integrating more listening activities into the teaching materials to accelerate the development of automated vocabulary knowledge. This could include not only a variety of different authentic listening activities allowing for diverse learner interests and backgrounds but also activities with adaptive difficulty. For example, listening activities could be differentiated based on adjustable playback speed or other scaffolding options, such as subtitles or glossaries. They could include multimodal listening activities together with repetition and variation which can in turn reinforce phonological recognition and strengthen lexical traces in long-term memory. Multiple means of action and expression should be aimed for by encouraging learners to use digital interaction such as speech recognition or interactive listening quizzes to provide real-time feedback and assess accuracy. Further innovative pedagogical solutions are needed to promote a verbal approach to language teaching, repeated and contextualised use of language that foments automaticity, simulates spontaneous real-world usage, and thus facilitates skill transfer, which at the same time lessens the emotional burden and thus might affect wellbeing and eventually impact on retention, progression, and success for these learners. It requires further investigation whether the inability to retrieve the appropriate vocabulary has different roots for students belonging to the two groups.

5.2. Differences in barriers

An interesting pattern arises when we look at the differences that trigger FLSA between the two groups. Group None mentions more competence focused concerns (expressing complex ideas, grammar) which reflects healthy learning motivation in line with Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan2000) who identify the psychological need of competence as one of the basic components of intrinsic motivation. Students in Group MH, on the other hand, are more likely to encounter fear of judgement and social evaluation and identity-focused barriers, which are the core features of social anxiety disorder. They in general tend to feel more tense when they have to use their target language. These perceptions lead to different speaking practices and coping strategies. Both groups generally experience FLSA, but students with mental health issues report being more likely to panic during spontaneous speaking in online tutorials and interact less with peers. They also report lower confidence in this situation, making them less likely to participate or move on from mistakes.

Existing knowledge from mental health research suggests that relating compassionately to oneself is thought to be particularly beneficial when responding to difficult and stress-inducing experiences, as it buffers individuals from some of such experiences (Blackie & Kocovski, Reference Blackie and Kocovski2019), as lower self-compassion is associated with higher psychological distress (Robinson-Auer & Gutiérrez-Menéndez, Reference Robinson-Auer and Gutiérrez-Menéndez2024). Ferrari et al. (Reference Ferrari, Hunt, Harrysunker, Abbott, Beath and Einstein2019) show that self-compassion-based interventions significantly reduce stress and anxiety alongside broader psychological benefits. The authors also showed that improvements in depression symptoms continued at follow-up and self-compassion gains were maintained particularly for group delivery methods, a type of intervention that could be integrated into online language modules for the benefit of all students.

It has been shown that avoidance strategies in the online language learning context are more nuanced (Bárkányi & Brash, Reference Bárkányi and Brash2025). Students not willing to interact might learn by watching recorded tutorial sessions, and those unwilling to speak might interact and fully engage with the tutorial via the chat function. The present study, however, found that students in Group MH are more likely to choose complete avoidance of the tutorials rather than partial or cautious participation. This causes them to miss valuable practice time which would equip them with more holistic skills, beyond improving their language skills, like handling unanticipated challenges, transmitting their knowledge effectively, and working in groups – qualities that employers highly value. From a UDL 3.0 lens, rapidly developing AI technologies may play a role in mitigating avoidance strategies. Knowledge from mental health research suggests that technology-driven interventions, such as virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET), are emerging as an effective way of treating adults with anxiety and related disorders (for example, Carl et al., Reference Carl, Stein, Levihn-Coon, Pogue, Rothbaum, Emmelkamp, Asmundson, Carlbring and Powers2019). Botella et al. (Reference Botella, Villa, Baños, Perpiñá and Alcañiz2000) highlight a number of benefits of the use of virtual reality (VR) such as providing a protected environment for patients to act without feeling threatened, the flexibility of VR to tailor to the specific needs of individuals, as well as offering for users to experience different situations at their own pace with a high degree of control over time and space. As Zacarin et al. (Reference Zacarin, Borloti and Haydu2019) and Girondini et al. (Reference Girondini, Frigione, Marra, Stefanova, Pillan, Maravita and Gallace2024) show, VR therapy can be harnessed for public speaking anxiety as it relies on anxiety habituation, where prolonged exposures to feared public speaking situations in simulated virtual environments will result in systematic desensitisation to such scenarios. Practising with chatbots and avatars in augmented reality or immersive VR settings can provide a controlled and supportive environment that can ease students into real-life-like language speaking situations effectively and reduce anxiety (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zou and Du2024). However, there are no studies yet explicitly focusing on how language learners with mental health issues could benefit from the affordances of emerging technologies. Prioritising such research is essential for the development of inclusive, UDL-driven language education.

5.3. Three in one: Mental health, FLSA, and spoken exams

Spontaneous speaking exams can be considered as a three in one bundle of anxiety: this context adds social anxiety to students’ FLSA, and coupled with test anxiety, creates a barrier that almost half of the students with mental health issues cannot overcome (Fig. 5). The dramatic rate differences for interactive spoken assignments represent more than academic performance gaps; they indicate systematic exclusion of students with mental health conditions from demonstrating competence, similarly to assessment practices that inadvertently discriminate against neurodivergent learners (Dolmage, Reference Dolmage2017).

The UK education system does not adequately prepare students for an oral assessment. While some English language courses at GCSE level might have an interactive spoken language endorsement, it is only foreign languages that include a spoken exam component, unlike in many other European countries that integrate oral assessment into a broader range of subjects (e.g. history, geography). These require students to think on their feet, which might be stressful, but also allows for immediate follow-up questions and clarifications that can help and guide them. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of such examination systems, but it is unquestionable that pupils in UK schools are less likely to acquire the skill set for oral exams – thus learning a language adds an extra layer of challenge. At the same time, there are several factors that can contribute to the feeling of constant pressure for students in UK higher education. Competitive job markets require one to ‘stand out’ by achieving high marks and building an impressive CV, while high tuition fees can also add to stress levels. Languages students also face native speaker ‘competitors’ while their efforts invested in language learning are not highly valued by the wider society.

In their ambition to protect students, the Equality and Human Rights Commission issued an advice note for the HE sector (2024) according to which universities have an anticipatory duty to make reasonable adjustments for students with mental health difficulties. This means that students do not need to provide evidence and do not need to follow a formal process to get support. Also, according to the note, once a student has told one member of staff about their difficulties this counts as if they had told the university. It is not clear yet what implications this will have for the HE sector in the long run, but in our view, finding satisfactory practice in language teaching is even more difficult. The learning outcomes for languages involve being able to speak spontaneously in the target language while FLSA is a context-specific anxiety most language learners encounter at some point during their language learning journey. The mentioned advice puts an unproportionate responsibility and pressure on language educators as they are expected to protect students without compromising competency standards, that is, to judge when a student experiences ‘normal’ FLSA and needs slight pressure, more encouragement, and easing into speaking, or when they require a ‘reasonable adjustment’ for a spoken assessment. Thus, policy-making regarding language education is crucial and should focus on a combination of preparing and protecting students while also keeping in mind language teachers’ wellbeing and giving them clearer suggestions on how to work with anxious students on (online) language courses. Applying graduated assessment pathways can be a good practice to care for diverse learners, to promote deep learning, and make assessment a tool for learning, not just a test of learning contributing to what Nieminen (Reference Nieminen2023) called anti-ableist assessment approaches.

5.4. Relationships

When it comes to preparation strategies, there are noteworthy differences between those applied by students with and without mental health difficulties. Students in Group None are more likely to use the course materials to prepare for the upcoming synchronous sessions, which suggests that they are more confident in their agency regarding their learning. This is in line with previous research showing a link between students’ autonomy in learning and their wellbeing (O’Shea & Salzer, Reference O’Shea and Salzer2020 – although the study is set in the f2f classroom context). Students in Group MH are also less likely to reach out to the tutor and seek help as part of preparation for synchronous sessions. This might keep them in the vicious circle of loneliness and isolation and failing to seek help while it is well-known that preventing social isolation is an important enabler of mental wellbeing (Davies, Reference Davies2014). Open University courses and tuition are designed to enhance the creation of learning communities via forum discussions, tutorials, and online meet-ups. However, students with mental health conditions find it hard to take part in any form of interaction in real time or asynchronous, although they need a supportive learning community. According to Lister et al. (Reference Lister, Seale and Douce2021), there is a fine line between the distance learning context being a barrier or an enabler for students with mental health difficulties. It is worth exploring how institutions, online language course designers, and tutors can ensure that the virtual learning context avoids isolation, but ‘keeps the distance’, considering that speaking a language is a skill that requires a lot of real-time practice. A step to take could be to develop action and participatory research with wider student involvement, or even student-lead research to explore what helps students with mental health conditions to increase participation and interaction.

The positive psychology movement has brought mental health and wellbeing factors in language learning also into the focus of L2 education (e.g. Derakhshan, Reference Derakhshan2022; Wang, Reference Wang2021). Although FLA and foreign language enjoyment are not negatively correlated (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2017) and negative and positive emotions often complement each other (MacIntyre & Gregersen, Reference MacIntyre and Gregersen2012), it is worth exploring how joyful learning can be achieved for students with mental health problems and whether it can ease them into interaction. From a UDL 3.0 perspective, providing emotional safety for learners by promoting autonomy and choice when it comes to topics or modes of interaction, as well as integrating reflective pauses, mindfulness exercises, or language games can help regulate stress and maintain cognitive-emotional balance. Accessible and sensory-rich materials can support comprehension without overloading the learner, while contextual scaffolding can help to reduce uncertainty, often a FLA trigger. Integrating uplifting and humorous content can allow for positive affective priming and enjoyment of learning. Saito et al. (Reference Saito, Dewaele, In’nami and Abe2025) show that long-term L2 progress is sustained when learners experience enjoyment, which reinforces motivation and practice.

It is interesting to note that a cause of anxiety among students in Group MH is the fear of offending their tutor – whether due to lack of knowledge or poor pronunciation – which can lead to avoidance and reluctance to interact. However, such avoidance can also discourage tutors, making them question whether their efforts are appreciated, potentially leading to their own avoidance strategies. Teachers might feel helpless about not being able to change the situation they have to put students in. Language teachers experience anxiety too (Horwitz, Reference Horwitz1996; Liu & Wu, Reference Liu and Wu2021), yet there is often little space in academic culture to express vulnerability. Openly acknowledging our own FLSA, in this way modelling resilience and openness, can help create a more inclusive and supportive learning environment with a stronger sense of belonging for students. Additionally, incorporating mindfulness practices or social-emotional learning (SEL) techniques in language teaching can help alleviate anxiety and foster greater confidence and engagement among learners (Gregersen & MacIntyre, Reference Gregersen and MacIntyre2014). Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Roberto, Pereira, Marques-Pinto and Veiga-Simão2021) showed that SEL interventions delivered to teachers significantly improved their social-emotional competence and reduced psychological distress. Teacher wellbeing, in turn, has been associated with improvements in teacher-student relationships and student outcomes (Dreer, Reference Dreer2023). These insights resonate with Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory, which stresses that affective and cognitive development are deeply interconnected, meaning that mental health is integral to effective language teaching. With mental health concerns increasing globally, embedding psychological support within language learning environments is both an educational necessity and a moral responsibility.

6. Conclusions, limitations and future research

This is the first study that explicitly compared the triggers and coping strategies of foreign language speaking anxiety (FLSA) for learners with mental health conditions and learners without additional requirements in online university language learning. The findings confirm that the main trigger of FLSA for all students is vocabulary retrieval. Beyond this, students with mental health conditions tend to experience barriers related to identity and confidence, while students without additional requirements frequently mention barriers related to competence, study, and learning as a cause of FLSA. These differences help explain disparities in participation and assessment outcomes. While students without mental health issues are more likely to use the course materials to prepare for synchronous sessions, those with mental health conditions often do not reach out to the tutor but avoid attending tutorials. Worryingly, the three in one bundle of FLSA, mental health, and spoken exam test anxiety creates a barrier that almost half of students with mental health issues cannot overcome.

It is important to acknowledge that students experiencing FLSA were probably more inclined to respond to the questionnaire. The study is not exempt from limitations, including its reliance on self-reported data, the static treatment of anxiety rather than its fluctuating intensity, and the absence of systematic analysis of intersectionality and comorbidity. These constraints should be kept in mind when interpreting the results.

Future research should move beyond description to investigate the mechanisms underlying vocabulary retrieval problems, distinguishing between cognitive processing and freeze responses. Intervention studies are also needed to evaluate strategies such as AI-supported speaking environments, virtual reality exposure, and self-compassion-based approaches that may reduce avoidance and foster enjoyment. Longitudinal and mixed-methods designs could further capture fluctuations in anxiety and motivation, and comparative studies across online and face-to-face contexts would clarify whether the patterns observed here are unique to digital learning.

Despite its limitations, this study breaks new ground by placing mental health at the center of FLSA research. It highlights the urgent need for more inclusive pedagogical and assessment practices that acknowledge the role of mental health in shaping language learning experiences. By addressing these challenges, institutions can better support all students in developing the confidence and skills required for successful language use.

Dr Zsuzsanna Bárkányi is a Senior Lecturer in Spanish at The Open University. Zsuzsanna has published extensively on the interface between phonetics and phonology, with a particular focus on voicing-related processes. Her current research focuses on multilingual speech acquisition, especially Spanish pronunciation learning and teaching, as well as foreign language speaking anxiety. Previously, she worked as a Speech Linguistic Project Manager for Google’s text-to-speech synthesis team. Zsuzsanna has expertise in teacher training and in online and distance language teaching and learning. She holds a PhD in Spanish Linguistics from Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary.

Bärbel Brash is a Staff Tutor in Languages at The Open University (UK). Bärbel has extensive experience both in upskilling language teachers worldwide in learning how to take their teaching online and teaching on distance language learning courses. Her research centres around the use of digital tools, language learning for wellbeing, older language learners, teacher education, as well as foreign language anxiety. She also contributes to the innovative external engagement activities of the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics across Scotland, in enterprise as well as research.