Introduction

Xinjiang, a key hub for animal husbandry in China, boasts vast grasslands that support extensive livestock production (Zheng and Qian, Reference Zheng and Qian2003). Sheep and cattle farming are vital to the region’s economy (Dawut and Tian, Reference Dawut and Tian2021). However, livestock diseases, particularly parasitic infections, pose significant threats to animal health and farm profitability (Yan, Reference Yan2022). Among these, Haemonchus contortus, a highly pathogenic gastrointestinal nematode, is a major constraint to ruminant production (Adduci et al., Reference Adduci, Sajovitz, Hinney, Lichtmannsperger, Joachim, Wittek and Yan2022). This parasite infects the abomasa of domestic ruminants, including sheep, goats and cattle, as well as wild ruminants, and occasionally the small intestine (Besier et al., Reference Besier, Kahn, Sargison and Van Wyk2016; Arsenopoulos et al., Reference Arsenopoulos, Minoudi, Symeonidou, Triantafyllidis, Fthenakis and Papadopoulos2024). Its blood-feeding behaviour causes anaemia, diarrhoea, weight loss and, in severe cases, death (Adduci et al., Reference Adduci, Sajovitz, Hinney, Lichtmannsperger, Joachim, Wittek and Yan2022). Seasonal reactivation of diapause larvae, known as the ‘spring rise’, triggers disease outbreaks, leading to significant livestock mortality (Jianhua and Longxian, Reference Jianhua and Longxian2013). Consequently, H. contortus contributes to substantial economic losses globally, with estimated annual treatment costs of USD 26 million in Kenya, USD 46 million in South Africa and USD 103 million in India (McRae et al., Reference McRae, McEwan, Dodds and Gemmell2014; Palevich et al., Reference Palevich, MacleanPH and ScottRW2019; Memon et al., Reference Memon, Tunio, Abro, Lu, Song, Xu and RuoFeng2024).

Located in central Eurasia along the Silk Road, Xinjiang’s strategic position facilitates extensive ruminant trade with mainland China and neighbouring countries. The region’s diverse terrain and climate, ranging from cold high-altitude zones to warm lowlands, influence parasite survival and distribution. Human activities, such as livestock movement, and environmental factors, including climate change, drive genetic diversity in H. contortus, with evidence of selection pressures from anthelmintic use and local climatic variations (Sallé et al., Reference Sallé, Doyle, Cortet, Cabaret, Berriman, Holroyd and Cotton2019).

In China, H. contortus severely impacts animal husbandry, particularly sheep farming, across most provinces (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Gasser, Fang, Zeng, Zhu, Qi, Zhang, Tan, Lei, Zhou, Zhao and Hu2016; Youwei et al., Reference Youwei, Jidong and Xiaoling2021; Ting, Reference Ting2024; Zhiya et al., Reference Zhiya, Shichen and Yuanhui2024). Despite global studies on H. contortus genetic diversity in regions such as Europe, the USA, Brazil, Australia, Malaysia and China, no data exist for Xinjiang (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Gasser, Li, Bao, Huang, Zou, Zhao, Wang, Yang, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and M2013; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Wang, Zhang, Peng, Yang, Wang, Bowman, Hou and Liu2017; Pitaksakulrat et al., Reference Pitaksakulrat, Chaiyasaeng, Artchayasawat, Eamudomkarn, Boonmars, Kopolrat, Prasopdee, Petney, Blair and Sithithaworn2021). This study addresses this gap by analysing the genetic diversity and population structure of 171 H. contortus individuals from 8 populations across southwestern, central and northeastern Xinjiang using the mitochondrial nad4 gene. These findings aim to elucidate the genetic characteristics of H. contortus in Xinjiang, providing a foundation for developing targeted, region-specific strategies to manage anthelmintic resistance and control this economically significant parasite.

Materials and methods

Parasite material

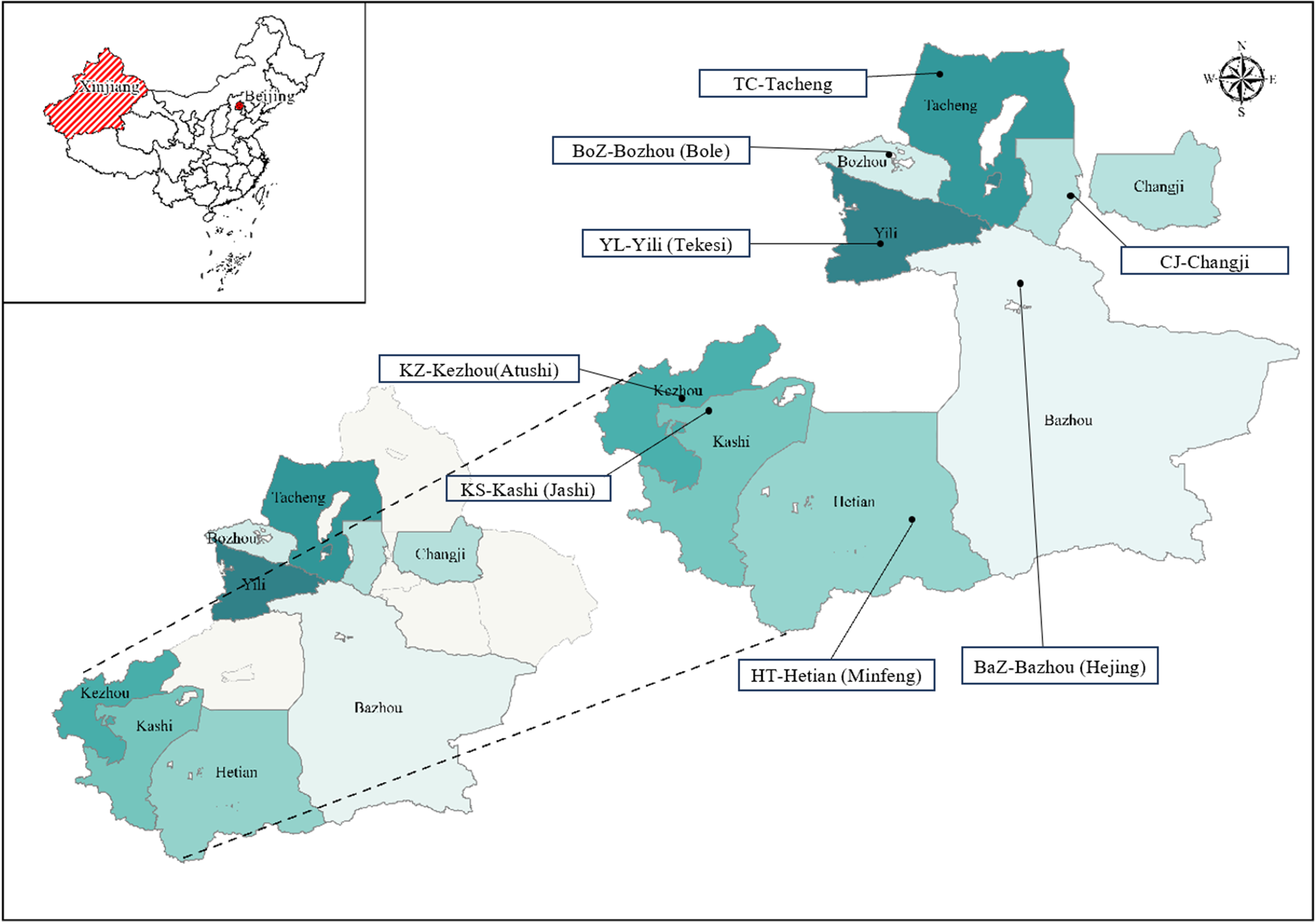

A total of 171 adult H. contortus worms were collected from the abomasa of sheep slaughtered at 8 locations across southern and northern Xinjiang, China, including Bazhou (Hejing), Kezhou (Atushi), Kashi (Jashi) and Hetian (Minfeng) in southern Xinjiang, and Yili (Tekesi), Tacheng, Changji and Bozhou in northern Xinjiang (Table 1 and Figure 1). These locations were separated by 550–2000 km. Worms were washed thoroughly in physiological saline, preserved in 70% ethanol and transported to the Parasitology Laboratory, College of Veterinary Medicine, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi. Upon arrival, worms were identified based on morphological characteristics, including the twisted digestive and reproductive tracts and copulatory bursa, following Tuerhong et al. (Reference Tuerhong, Tuersong, Maimaiti, Maimaitiyiming, Zhang, Xuekelaiti, Tuoheti, Xin and Abula2025). Specimens were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Figure 1. Sampling sites. Eight different geographical locations in China (longitudes and latitudes given in Table 1) at which adult Haemonchus contortus were collected from sheep.

Table 1. Collection sites for sheep-derived H. contortus samples across 8 regions in Xinjiang, China

Genomic DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from adult male H. contortus worms using the Tiangen Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (DP-304, Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), following the protocol outlined in Tuerhong et al. (Reference Tuerhong, Tuersong, Maimaiti, Maimaitiyiming, Zhang, Xuekelaiti, Tuoheti, Xin and Abula2025). DNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Samples with concentrations exceeding 30 ng μL−1 were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

PCR amplification and sequencing

The ITS-2 region (265 bp) and mitochondrial nad4 gene (800 bp) of 171 H. contortus were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primer sets and thermal cycling conditions (Table 2; Bott et al., Reference Bott, Campbell, Beveridge, Chilton, Rees, Hunt and Gasser2009; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Gasser, Li, Bao, Huang, Zou, Zhao, Wang, Yang, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and M2013). Each PCR reaction was conducted in a 25 µL volume, containing 2.0 µL of template DNA, 1.0 µL of forward primer, 1.0 µL of reverse primer, 12.5 µL of 2× TransStart FastPfu Fly PCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and 8.5 µL of DEPC-treated water. Post-amplification, 5 µL of PCR products were analysed by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm target amplicons. Amplicons were sequenced (Sanger) by Wuhan Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China).

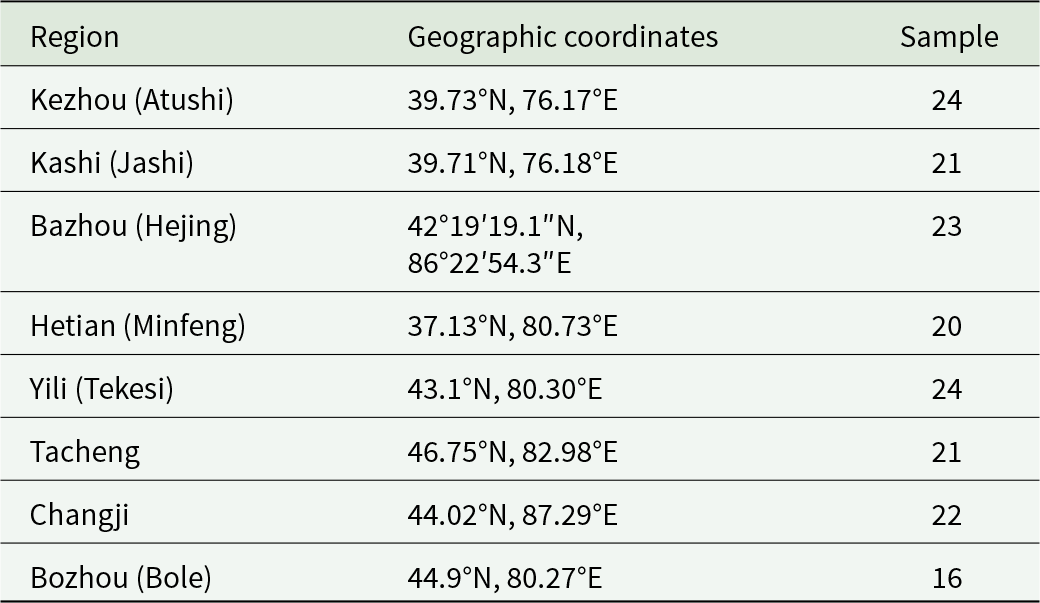

Table 2. Primers and thermal cycling conditions for PCR amplification of H. contortus ITS-2 and nad4 genes

Data analysis

Sequencing results were aligned against NCBI databases to confirm the acquisition of target ITS-2 and nad4 gene sequences. Sequences were aligned using Clustal W in MEGA 7.0 (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Nei and Kumar2004) and manually trimmed. Homology comparisons were performed using BioEdit v7.2 (Tippmann, Reference Tippmann2004) between the obtained sequences and reference sequences from GenBank (accession numbers: MK300723.1, KF176320.1, PP531612.1, and MW662167.1). Haplotype diversity, nucleotide diversity and neutrality tests (Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs) were calculated using DnaSP v6.0 (Rozas et al., Reference Rozas, Ferrer-Mata, Sánchez-delbarrio, Guirao-Rico, Librado, Ramos-Onsins and Sánchez-Gracia2017). Haplotype sequences were aligned in MEGA 7.0 using Haemonchus placei (GenBank accession: AF070825.1) as the out-group, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbour-joining (NJ) method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. AMOVA and genetic differentiation (Fst) were conducted using Arlequin v3.5 (Excoffier et al., Reference Excoffier, Smouse and Quattro1992). A haplotype network was generated using PopART v1.7 (Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Bryant, Nakagawa and Nakagawa2015).

Results

Sequences analyses

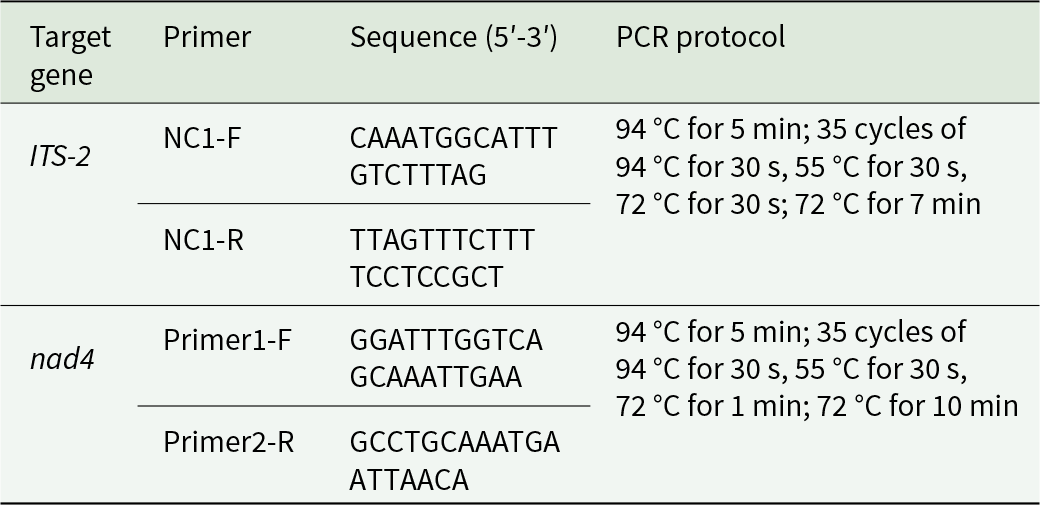

To further validate the species identity, a homology analysis was performed on a representative subset of 171 sequenced samples. These samples had previously been aligned and confirmed as H. contortus using NCBI. Specifically, 2 sequences were randomly selected from each of the 8 geographical regions (16 sequences in total) and aligned against reference sequences. These included 2 H. contortus reference sequences (GenBank: MK300723.1 and KF176320.1) and 2 H. placei reference sequences (GenBank: PP531612.1 and MW662167.1). Sequence homology with H. contortus ranged from 92.8% to 100%, while nucleotide identity with H. placei ranged from 87.8% to 97.8% (Figure 2). These alignments confirmed that all sequenced samples were H. contortus. The majority of these sequences exhibited high sequence similarity (≥99%) with H. contortus reference sequences, consistent with the established molecular identification threshold for this genus (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Chilton and Gasser1995). However, 2 sequences (e.g., from samples HT16 and YL14) displayed intermediate similarity to both reference species. Subsequent inspection of their sequencing chromatograms revealed heterozygous base calls at diagnostic nucleotide positions, a pattern indicative of interspecific hybridization between H. contortus and H. placei, as previously reported (Brasil et al., Reference Brasil, Nunes, Bastianetto, Drummond, Carvalho, Leite, Molento and Oliveira2012). With the exception of these 2 putative hybrids, the alignments confirmed the identity of the remaining sequenced samples as H. contortus.

Figure 2. Pairwise sequence homology (%) of 16 ITS-2 sequences from H. contortus with reference sequences of H. contortus and H. placei from GenBank.

Population genetic analysis, based on the nad4 gene, was therefore conducted on a confirmed dataset of 171 pure H. contortus samples. This analysis identified 163 haplotypes, with 16–24 haplotypes per population. Nucleotide diversity across the 8 populations ranged from 0.02007 to 0.03145, with the Tacheng population exhibiting the highest value (0.03145). Haplotype diversity ranged from 0.995 to 1.000, reflecting high genetic variation. Tajima’s D values ranged from −1.711 to −0.862, and Fu’s Fs values ranged from −19.345 to −7.669 (Table 3). These findings suggest no recent population bottlenecks in the 8 populations.

Table 3. Genetic diversity parameters of the nad4 gene in H. contortus populations from 8 regions in Xinjiang, China

Phylogenetic analysis of nad4

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using nad4 sequences from 163 H. contortus isolates from Xinjiang, China, with H. placei (GenBank: AF070825.1) as the out-group (Figure 3). Genetic distances among haplotypes showed continuous variation, with sequences distributed across diverse geographic regions without clear geographic clustering. Most nodes had low bootstrap support (<55%), but a clade of 2 Atushi isolates, 1 Hetian isolate and 1 Yili isolate showed moderate support (71%). Additionally, a clade comprising 2 Bozhou isolates, 1 Changji isolate, 1 Bazhou isolate and 2 Yili isolates exhibited strong bootstrap support (91–96%).

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of 163 nad4 haplotypes from H. contortus constructed using the neighbour-joining (NJ) method.. TC: Tacheng, ATS: Atushi, YL: Yili, KS: Kashi, HT: Hetian, HJ: Hejing, CJ: Changji, BoZ: Bozhou.

To further explore genetic relationships among the 163 nad4 haplotypes, a haplotype network was constructed (Figure 4). Results revealed no distinct geographic clustering of haplotypes, consistent with phylogenetic analysis. However, a few haplotypes from Bazhou and Yili formed relatively distinct branches, corroborating the phylogenetic findings.

Figure 4. Haplotype network of 163 nad4 haplotypes from H. contortus across 8 regions in Xinjiang, China.

Nucleotide distance analysis

Nucleotide distance analysis of 8 H. contortus populations from Xinjiang, China, revealed minimal variation in genotype frequencies and no significant population structure (Figure 5). These results align with genetic differentiation (Fst) and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA), both indicating high gene flow among populations. Geographic isolation did not significantly influence genetic differentiation, with no evidence of subpopulation structure driven by geographic distance. Thus, frequent gene flow results in a largely homogeneous genetic structure across populations.

Figure 5. Genetic distance analysis of nad4 sequences from 8 H. contortus populations in Xinjiang, China.

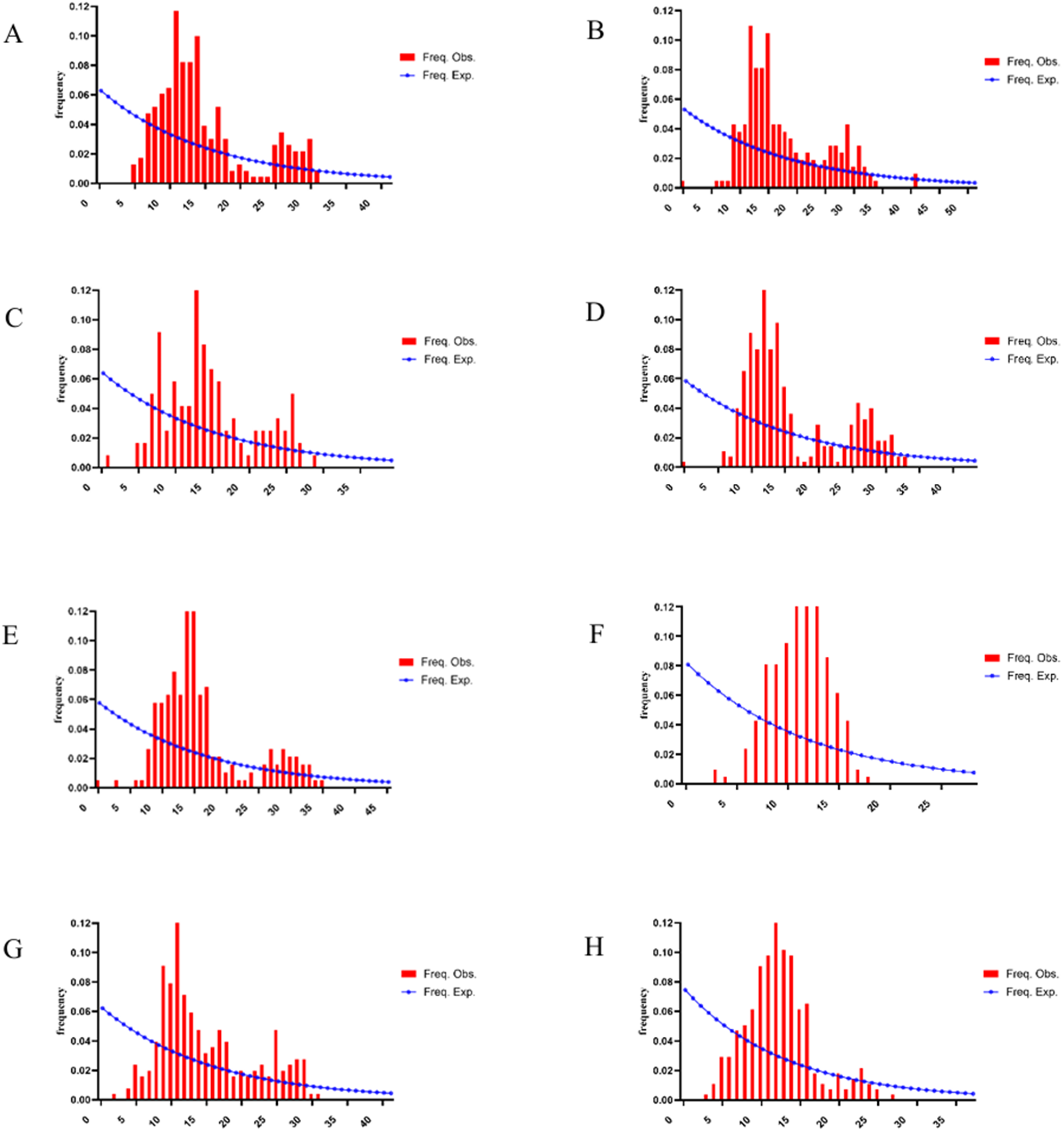

Mismatch distribution analysis

Mismatch distribution analysis of the nad4 gene in 8 H. contortus populations from Xinjiang, China, revealed a multimodal distribution (Figure 6). The red curve represents the expected distribution under a population expansion model, while the blue bars depict the observed distribution from sequencing data. A unimodal distribution typically indicates recent population expansion, whereas a multimodal distribution suggests population stability. The multimodal pattern observed across Xinjiang populations, together with significantly negative Fu’s Fs values and evidence of high gene flow, indicates a structured population experiencing demographic expansion.

Figure 6. Mismatch distribution of nad4 gene sequences from 8 H. contortus populations in Xinjiang, China. A:CJ.B:TC.C:BoZ.D:YL.E:HT.F:KS.G:BaZ.H:KeZ.

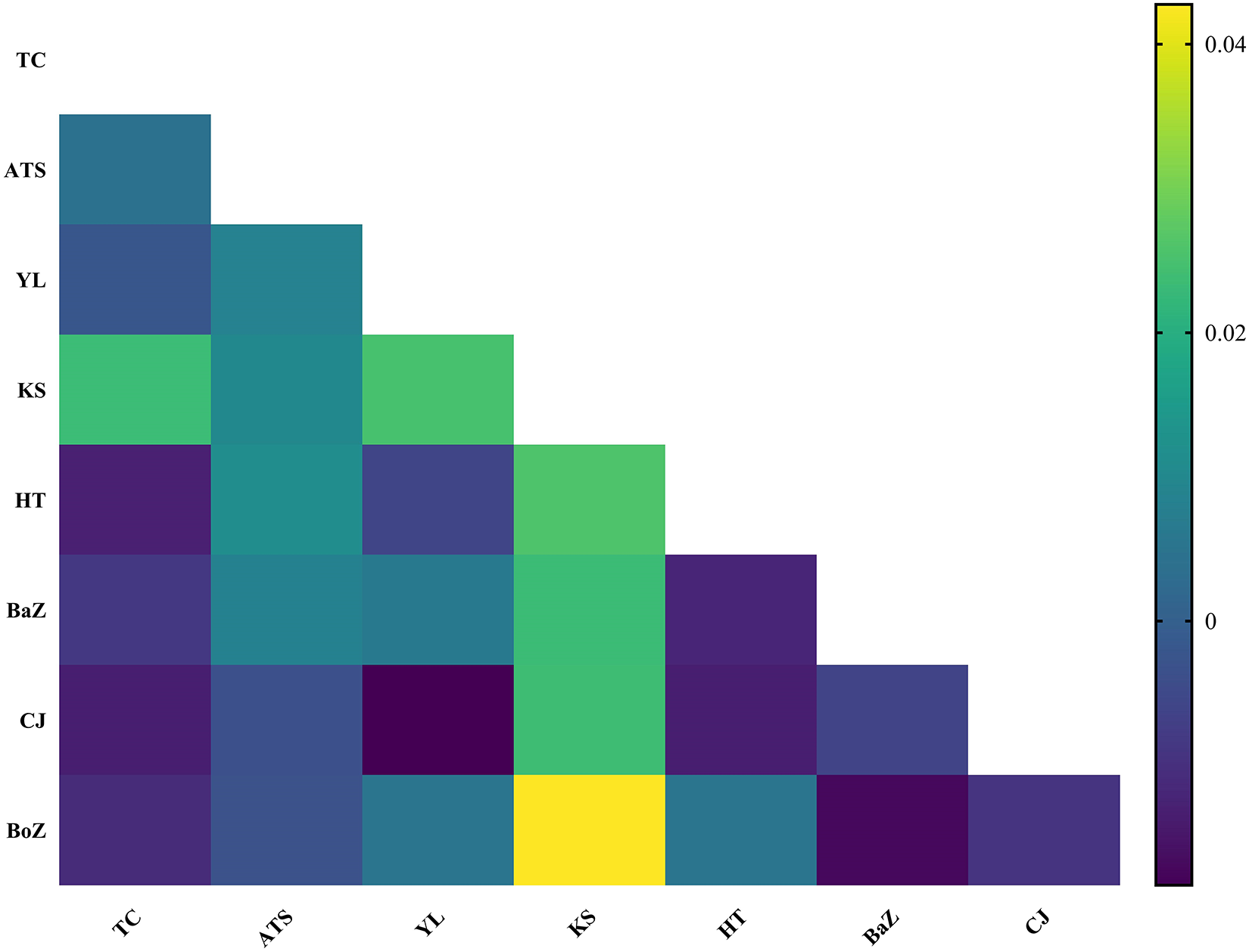

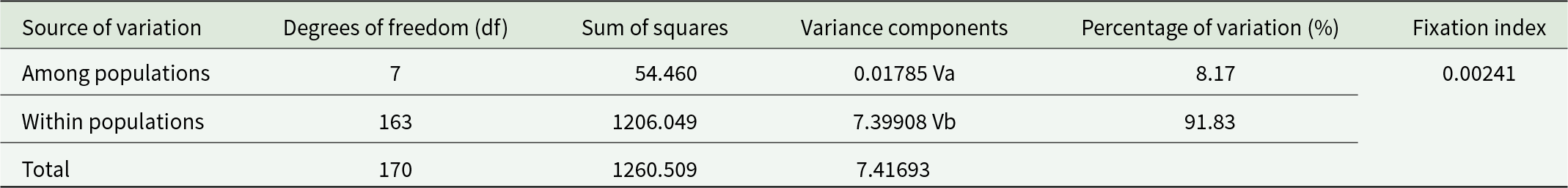

Population genetic structure

Despite their diverse geographic origins, the haplotype network of 163 nad4 haplotypes from H. contortus populations in Xinjiang, China, showed no significant genetic structure, consistent with low pairwise genetic differentiation (Figure 4). Fst values, ranging from −0.013 to 0.043, indicated minimal genetic differentiation among the 8 populations, reflecting high gene flow (Figure 7). Although most populations showed extremely low genetic differentiation, the pairwise comparison heatmap (Figure 7) indicated that the Kashi (KS) population exhibited relatively higher differentiation. Notably, KS was genetically closest to the Atushi (ATS) population, and as shown in Figure 1, these 2 populations are also geographically proximate, providing a reasonable explanation for the observed genetic pattern.

Figure 7. Pairwise Fst values among 8 H. contortus populations from Xinjiang, China. TC: Tacheng, ATS: Atushi, YL: Yili, KS: Kashi, HT: Hetian, HJ: Hejing, CJ: Changji, BoZ: Bozhou.

AMOVA of 8 H. contortus populations from Xinjiang, China, revealed that 91.83% of genetic variation occurred within populations, with only 0.24% attributed to differences among populations (Table 4).

Table 4. AMOVA for nad4 gene sequences in 8 H. contortus populations from Xinjiang, China

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of the genetic diversity of H. contortus based on the nad4 gene across 8 populations in Xinjiang, China. All populations exhibited high haplotype diversity (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Gasser, Li, Bao, Huang, Zou, Zhao, Wang, Yang, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and M2013). The haplotype diversity in our Xinjiang populations (Hd = 0.995–1.000) is comparable to the high levels of genetic diversity (Hd = 0.993–1.000) reported for other Chinese H. contortus populations. Nucleotide diversity (Pi: 0.02007–0.03145) indicates substantial genetic variation, consistent with thresholds for high diversity (Pi > 0.005, Hd > 0.5; Grant and Bowen, Reference Grant and Bowen1998). Low Fst values (−0.013 to 0.043) suggest minimal genetic differentiation and high gene flow among populations, aligning with previous studies on H. contortus in China (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Gasser, Li, Bao, Huang, Zou, Zhao, Wang, Yang, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and M2013, Reference Yin, Gasser, Li, Bao, Huang, Zou, Zhao, Wang, Yang, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and Hu2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Gasser, Yang, Yin, Zhao, Bao, Pan, Huang, Wang, Zou, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and Hu2016).

AMOVA revealed that 91.83% of genetic variation occurred within populations, with only 0.24% among populations, indicating a negligible impact of geographic isolation on genetic structure. These findings are consistent with global studies on H. contortus populations (Gharamah et al., Reference Gharamah, Azizah and Rahman2012; Hussain et al., Reference Hussain, Periasamy, Nadeem, Babar, Pichler and Diallo2014; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Wang, Zhang, Peng, Yang, Wang, Bowman, Hou and Liu2017; Pitaksakulrat et al., Reference Pitaksakulrat, Chaiyasaeng, Artchayasawat, Eamudomkarn, Boonmars, Kopolrat, Prasopdee, Petney, Blair and Sithithaworn2021; Mannan et al., Reference Mannan, Chowdhury, Hossain and Kabir2023; Arsenopoulos et al., Reference Arsenopoulos, Minoudi, Symeonidou, Triantafyllidis, Fthenakis and Papadopoulos2024).

Phylogenetic and haplotype network analyses of 163 nad4 haplotypes revealed no distinct geographic clustering, suggesting extensive gene flow likely driven by human-mediated sheep migration. This high gene flow is consistent with the open farming systems and extensive animal transportation practices common in Xinjiang, which facilitate the movement of parasites across regions. These results align with studies in China, Bangladesh and Greece, which report high gene flow across H. contortus populations using various genetic markers (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Gasser, Li, Bao, Huang, Zou, Zhao, Wang, Yang, Zhou, Zhao, Fang and M2013; Arsenopoulos et al., Reference Arsenopoulos, Minoudi, Symeonidou, Triantafyllidis, Katsafadou, Lianou, Fthenakis and Papadopoulos2020; Parvin et al., Reference Parvin, Dey, Rony, Akter, Anisuzzaman and Alam2022; Kalule et al., Reference Kalule, Vudriko, Nanteza, Ekiri, Alafiatayo, Betts, Betson, Mijten, Varga and Cook2023).

Mismatch distribution analysis indicated a multimodal pattern, suggesting stable population dynamics in Xinjiang, likely due to high environmental adaptability. Tajima’s D values (−1.711 to −0.862) suggest population expansion or negative selection, but high gene flow (evidenced by Fst and AMOVA) precludes significant subpopulation differentiation. These findings collectively highlight frequent gene flow, likely facilitated by host movement, maintaining a homogeneous genetic structure across populations.

However, the interpretation of pronounced gene flow should be tempered by the limitations of the study. The use of a single mitochondrial marker (nad4) may lack the resolution to discern fine-scale population structure or to fully distinguish contemporary gene flow from shared ancestral polymorphism. This is a recognized constraint of mitochondrial DNA in nematode population genetics, where its resolution is often lower compared to nuclear markers (Blouin, Reference Blouin2002). Therefore, while the observed genetic homogeneity is consistent with high gene flow, the potential influence of historical demographic processes cannot be ruled out. Future studies utilizing high-resolution nuclear markers, such as genome-wide Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, will be essential to accurately quantify the extent of contemporary gene flow and elucidate the population dynamics of H. contortus in this region.

With no commercial vaccine available for haemonchosis, control of H. contortus relies heavily on anthelmintics such as albendazole, ivermectin and levamisole (Kotze and Prichard, Reference Kotze and Prichard2016). However, widespread anthelmintic resistance exerts strong selective pressure on parasite populations (Besier et al., Reference Besier, Kahn, Sargison and Van Wyk2016). Specifically, the common use of albendazole and ivermectin in Xinjiang, where resistance has been documented (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Zhang, Yang, Ahmad, Li, Du and Hu2017), means that the high gene flow observed among our studied populations likely accelerates the regional dispersal of resistance alleles, promoting resistant genotypes (Kotze et al., Reference Kotze, Hunt, Skuce and von Samson-himmelstjerna2014; Chaudhry et al., Reference Chaudhry, Redman, Raman and Gilleard2015). This underscores the urgent need to investigate anthelmintic resistance in H. contortus in Xinjiang.

These findings provide critical insights into the adaptive evolution and population dynamics of H. contortus in Xinjiang, highlighting the role of gene flow in reducing geographic differentiation and enabling rapid adaptation to selective pressures, such as anthelmintic use (Kaplan and Vidyashankar, Reference Kaplan and Vidyashankar2012). This study establishes a foundation for developing region-specific control strategies to manage anthelmintic resistance and mitigate the economic impact of this parasite, while acknowledging that its reliance on a single mitochondrial gene (nad4) represents a limitation. Future whole-genome studies could provide finer-scale resolution of population structure and resistance mechanisms to further advance these control efforts.

Conclusions

In this study represents the first detailed investigation of H. contortus genetic diversity across 8 regions in Xinjiang. Data from the nad4 gene suggest that high gene flow minimizes genetic differentiation despite geographic separation, which could facilitate the spread of anthelmintic resistance. These insights, while noting the limitation of a single genetic marker, enhance our understanding of H. contortus population dynamics and support the development of targeted control measures, contributing to broader efforts in biodiversity conservation and evolutionary ecology.

Data availability statement

The datasets of this article are included within the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to all the veterinary technicians within the study area for their help in sample collection.

Author contributions

W.T. and R.T. designed the methodology, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. A.T., A.M., D.X., L.X., A.A. and Y.X. contributed to the methodology and reviewed and edited the manuscript. B.C., M.H. and S.A. validated the results, conducted statistical analysis, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Q.G. and W.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript and approved the submitted version. W.T. and R.T. contributed to the work equally and should be regarded as co-first authors.

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32360890 to WT) and the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Grant No. 2023D01B32 to W.T.).

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.