Introduction

Besnoitia besnoiti is an obligate intracellular apicomplexan parasite that causes bovine besnoitiosis and affects cattle industry, besides causing detrimental effects on animal welfare. The definitive host of this coccidian parasite is still unestablished, being likely mechanically transmitted within infected herds via blood sucking insects (i.e. tabanids or stable flies), while the participation of wild ruminants as reservoirs has been proposed (Alvarez-García et al. Reference Alvarez-García, Frey, Mora and Schares2013). Since 2010, cattle besnoitiosis has been considered an emerging disease in the EU (Alvarez-García et al. Reference Alvarez-García, Frey, Mora and Schares2013). In contrast to other cyst-forming coccidian parasites, such as Neospora caninum, Toxoplasma gondii or Sarcocystis spp., B. besnoiti tissue cysts are mainly found in skin and mucosa (Alvarez-García et al. Reference Alvarez-García, García-Lunar, Gutiérrez-Expósito, Shkap and Ortega-Mora2014; Langenmayer et al. Reference Langenmayer, Gollnick, Majzoub-Altweck, Scharr, Schares and Hermanns2015). Overall, acute bovine besnoitiosis is characterised by unspecific clinical signs, such as lethargy, anorexia, tachycardia and tachypnoea, accompanied by febrile responses of infected animals as a consequence of inflammatory reactions induced by tachyzoite proliferation (Alvarez-García et al. Reference Alvarez-García, García-Lunar, Gutiérrez-Expósito, Shkap and Ortega-Mora2014). In this context, endothelial cells serve as major host cells for B. besnoiti tachyzoite proliferation in vivo. Respective infections induce vasculitis, thrombosis and necrosis in venules and arterioles (Langenmayer et al. Reference Langenmayer, Gollnick, Majzoub-Altweck, Scharr, Schares and Hermanns2015). Besides other cell types, proliferation of B. besnoiti tachyzoites can easily be performed in bovine primary endothelial cells in vitro (Maksimov et al. Reference Maksimov, Hermosilla, Kleinertz, Hirzmann and Taubert2016; Jiménez-Meléndez et al. Reference Jiménez-Meléndez, Ramakrishnan, Hehl, Russo and Álvarez-García2020).

The tachyzoite-based merogonic lytic cycle is a multi-step process initiated when free tachyzoites actively invade a suitable host cell, proliferate within a parasitophorous vacuole (PV) and finally egress by host cell lysis (Black and Boothroyd, Reference Black and Boothroyd2000). On a mechanistic level, the lytic cycle of apicomplexan parasites is tightly regulated by Ca2+ signalling (Black and Boothroyd, Reference Black and Boothroyd2000; Lourido and Moreno, Reference Lourido and Moreno2015; Hortua Triana et al. Reference Hortua Triana, Márquez-Nogueras, Vella and Moreno2018). Overall, cumulated evidence indicates that Ca2+ fluxes in apicomplexans, such as T. gondii, are linked to invasion, conoid extrusion, microneme discharge, intracellular proliferation and egress (Lourido and Moreno, Reference Lourido and Moreno2015; Hortua Triana et al. Reference Hortua Triana, Márquez-Nogueras, Vella and Moreno2018). In this context, apicomplexan parasites store their intracellular Ca2+ within organelles, including endoplasmic reticulum (ER), apicoplast and acidocalcisomes (Lourido and Moreno, Reference Lourido and Moreno2015; Hortua Triana et al. Reference Hortua Triana, Márquez-Nogueras, Vella and Moreno2018), allowing them to tightly modulate cellular responses. Physiologically, cytoplasmic Ca2+ acts as a coupling factor and second messenger for multiple cellular functions (Carafoli and Krebs, Reference Carafoli and Krebs2016). In general, resting cells accumulate Ca2+ in intracellular stores, the ER and mitochondria (Carafoli and Krebs, Reference Carafoli and Krebs2016). In non-excitable cells, such as endothelial cells, extracellular signals are propagated downstream via the activation of the inositol 1,4,5-triposphate/calcium (InsP3/Ca2+) pathway (Berridge, Reference Berridge2016). Activation of this pathway is initiated by the interaction of a cytoplasmic receptor with its ligand, leading to the activation of phospholipase C (PLC). PLC catalyses the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP₂) into diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol trisphosphate (IP₃). IP₃ then binds to its receptor (IP₃R), triggering the release of Ca2⁺ ions into the cytoplasm (Berridge, Reference Berridge2016). Besides, other Ca2⁺-related signalling pathways present in specific cell types can induce intracellular Ca2⁺ fluxes via other receptors, such as ryanodine receptors (RyR).

Nonetheless, Ca2+ signalling has been comparatively much less studied in apicomplexan species than in mammalian cells. Interestingly, the presence of PLC homologs in different apicomplexans, including T. gondii (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Marchesini and Moreno2006) and B. besnoiti (Strain Bb-Ger1; ToxoDB), indicates a conserved role of this enzyme. In this context, a conditional knockout of PLC in T. gondii tachyzoites and Plasmodium falciparum merozoites causes highly altered phenotypes and severe impairment of intracellular development, thereby compromising the cellular lytic cycle and in vivo proliferation (Bullen et al. Reference Bullen, Jia, Yamaryo-Botté, Bisio, Zhang, Jemelin, Marq, Carruthers, Botté and Soldati-Favre2016; Burda et al. Reference Burda, Ramaprasad, Bielfeld, Pietsch, Woitalla, Söhnchen, Singh, Strauss, Sait, Collinson, Schwudke, Blackman and Gilberger2023) and demonstrating a pivotal role of this enzyme in apicomplexan biology. Likewise, pharmacological blockage of PLC in T. gondii tachyzoites interferes with conoid extrusion and microneme discharge, affecting host cell invasion (Ricard et al. Reference Ricard, Pelloux, Favier, Gross, Brambilla and Ambroise-Thomas1999; Del Carmen et al. Reference Del Carmen, Mondragón, González and Mondragón2009; Bullen et al. Reference Bullen, Jia, Yamaryo-Botté, Bisio, Zhang, Jemelin, Marq, Carruthers, Botté and Soldati-Favre2016). Even though a participation of IP3R- and RyR-sensitive mechanisms has been proposed for both T. gondii tachyzoites and P. chaubadi/P. falciparum merozoites (Passos and Garcia, Reference Passos and Garcia1998; Lovett et al. Reference Lovett, Marchesini, Moreno and Sibley2002; Alves et al. Reference Alves, Bartlett, Garcia and Thomas2011), the absence of IP3R and ryanodine receptor homologues in apicomplexan parasites indicates significant divergences in apicomplexans.

To our best knowledge, details on Ca2+ signalling in B. besnoiti tachyzoites are currently lacking and related data almost exclusively come from the closely related and much more studied apicomplexan parasite, T. gondii. Interestingly, downstream Ca2+-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) homologues are proposed as new pharmacological targets for B. besnoiti infection control (Jiménez-Meléndez et al. Reference Jiménez-Meléndez, Ojo, Wallace, Smith, Hemphill, Balmer, Regidor-Cerrillo, Ortega-Mora, Hehl, Fan, Maly, Van Voorhis and Álvarez-García2017). The current work aims to study Ca2+ dynamics in B. besnoiti tachyzoites, in the context of PLC activation-related mechanisms and the role of different Ca2+ stores in B. besnoiti tachyzoites in infected primary bovine endothelial cells.

Materials and methods

Host cells and Besnoitia besnoiti tachyzoite in vitro culture

Primary bovine umbilical vein endothelial cells (BUVEC) were isolated as described elsewhere (Taubert et al. Reference Taubert, Zahner and Hermosilla2006). BUVEC were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere in modified endothelial cell growth medium (modECGM), prepared by the dilution of complete ECGM medium (PromoCell; Heidelberg, Germany) with M199 (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) at a 1:3 ratio. The medium was supplemented with 500 U/mL penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) and 5% foetal calf serum (FCS; Biochrom; Cambridge, UK). BUVEC (Isolates= 6) were seeded into 12-well plates (Sarstedt; Nümbrecht, Germany) pre-coated with fibronectin (1:400; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) and cultured until confluence. BUVEC with no more than three passages were used in this study.

Tachyzoites of B. besnoiti (strain Bb Evora04) were propagated in Madin Darby bovine kidney cells (MDBK) in RPMI medium (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA), supplemented with 500 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin and 5% FCS (all Sigma-Aldrich). Infected and non-infected cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere. Vital tachyzoites were collected from supernatants of infected host cells by a centrifugation step at 800 × g for 5 min, and resuspended either in modECGM or HBSS depending on the experimental setup.

Besnoitia besnoiti tachyzoite treatments and infection assays

As illustrated in Table 1, for PLC inhibition-related experiments, freshly collected B. besnoiti tachyzoites (six biological replicates) were pre-treated for 30 min at 37 °C with the PLC inhibitor U73122 (5 µM; AdipoGen Life Sciences; San Diego, USA) or vehicle (0.02% DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich). Complementarily, given that U73122-derived Ca2+ fluxes are triggered by sarco/ER Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) inhibition (Macmillan and McCarron, Reference Macmillan and McCarron2010), additional experiments with the PLC-specific inhibitor D609 (5 µM; Cayman; Ann Arbor, USA) were included in this study. Inhibitor-treated and untreated tachyzoites were used to infect BUVEC at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 8:1 in the presence of inhibitors or vehicle. This MOI is justified on the early infection time points here studied (see below). Additionally, to establish the role of intracellular or extracellular Ca2+ sources on B. besnioti infection, chelation experiments were carried out. Briefly, B. besnoiti tachyzoites were harvested as described above and treated with 50 µM BAPTA-AM (Invitrogen; Thermofisher; Waltham, USA) or vehicle (same as above) for 30 min at 37 °C for intracellular Ca2+ chelation. Excess BAPTA was removed by washing with PBS (5 min, 800 × g). Thereafter, treated and untreated B. besnoiti tachyzoites were used to infect BUVEC as described above in the presence or absence of 5 mM EGTA (extracellular Ca2+ chelator, Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA), to evaluate the effects of extracellular chelation (EGTA) or intracellular and extracellular chelation (BAPTA + EGTA). In addition, endothelial host cell infection by newly released B. besnoiti tachyzoites from previously infected cells was considered to establish the infection rate time points (Jiménez-Meléndez et al. Reference Jiménez-Meléndez, Fernández-Álvarez, Calle, Ramírez, Diezma-Díaz, Vázquez-Arbaizar, Ortega-Mora and Álvarez-García2019). Specifically, since B. besnoiti tachyzoite (strain BbEvora4) proliferation in BUVECs is characterised by an increase in the number of tachyzoites per PV after 12 post-infection (p.i.) (Velásquez et al. Reference Velásquez, Lopez-Osorio, Pervizaj-Oruqaj, Herold, Hermosilla and Taubert2020), only earlier time points p.i. were evaluated to avoid proliferation-driven infection rate effects. Given that BUVEC layers exhibit a flat morphology, intracellular tachyzoites can easily be detected by phase contrast microscopy. Thus, phase contrast images were acquired at one or three h p.i. by an inverted microscope (IX81®, Olympus) equipped with a digital camera (XM10®, Olympus) for infection rate assessment. Finally, the infection rate was established as [(infected cells/total cells) × 100], from four randomly selected fields on each studied time point (1 and 3 h p.i.) as described elsewhere (Larrazabal et al. Reference Larrazabal, López-Osorio, Velásquez, Hermosilla, Taubert and Silva2021b).

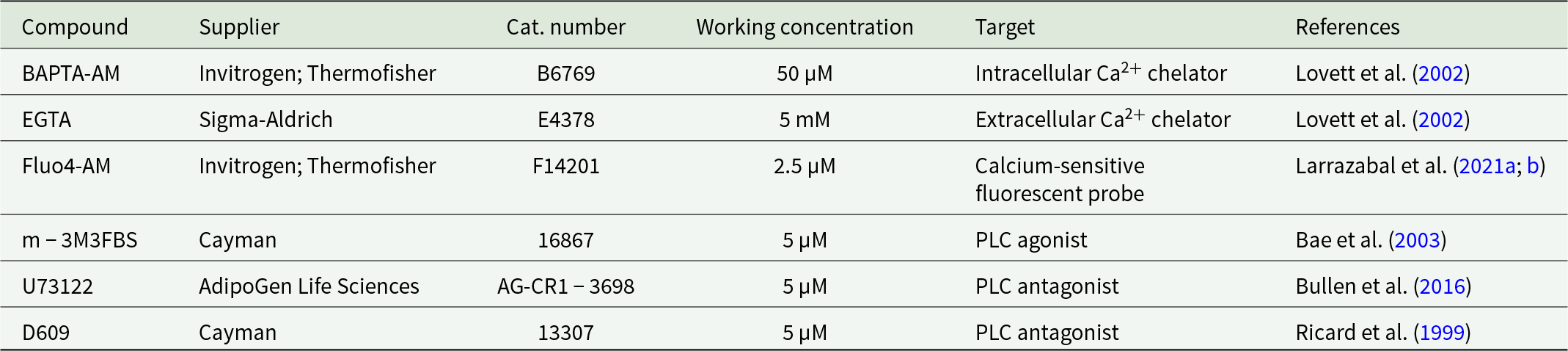

Table 1. Summary of main treatments and assays performed in this study

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Registries of Ca2+ signals were obtained by loading BUVEC (Isolates = 5) or B. besnoiti tachyzoites (six biological replicates) with the Ca2+-sensitive dye fluo-4 (Invitrogen; Thermofisher; Waltham, USA) as described before (Larrazabal et al. Reference Larrazabal, Hermosilla, Taubert and Conejeros2021a; Reference Larrazabal, Hermosilla, Taubert and Conejeros2021a). Briefly, host cells or free tachyzoites were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in HBSS in 2.5 µM fluo-4. Thereafter, excess dye was removed by PBS washing (5 min, 800 × g) and cells were suspended in HBSS. For experimentation, fluo-4-loaded B. besnoiti tachyzoites (2 × 106 and 1 × 107 tachyzoites/ml) were placed into a 96-well plate (Sarstedt; Nümbrecht, Germany) per experimental condition and then exposed to m-3M3FBS (PLC agonist, 5 µM, Cayman; Ann Arbor, USA). In this context, the concentration of m-3M3FBS used in this study was justified by the absence of previous reports in B. besnoiti or other apicomplexans, as well as by the cytotoxic effects on free tachyzoites observed at higher concentrations (25 µM; Supplementary Figure 1). In case of BUVEC-related Ca2+ quantification, cells were seeded into a 12-well plate (Sarstedt; Nümbrecht, Germany), infected with B. besnoiti tachyzoites (MOI 3:1), thereafter loaded with fluo-4 as described above and lysed by 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) treatments at 6, 12 and 24 h p.i. Spectrofluorometric analysis at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm was performed in an automated multiplate monochrome reader (Varioskan Flash®, Thermo Scientific). No technical replicates were carried out in Ca2+ flux assays.

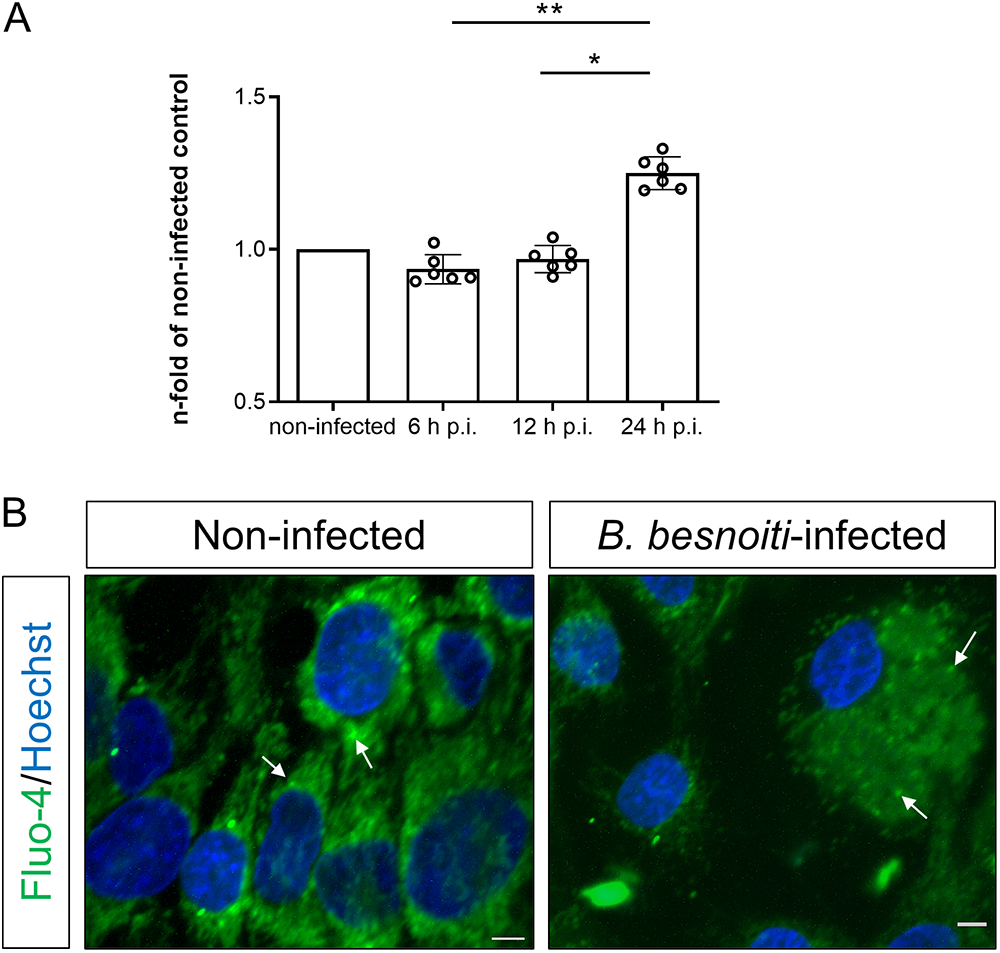

Figure 1. Besnoitia besnoiti infection increases host cellular Ca2+ levels. (A) Fluo-4-based Ca2+ signals at different hours post-infection (h p.i.) in B. besnoiti-infected BUVEC, expressed as fold of its respective non-infected control (B) LSCM from non-infected and B. besnoiti-infected BUVEC at 24 h p.i. Arrows indicate Fluo-4-derived signals located in intracellular vesicles. Size scale bars correspond to 5 μm. Bars represent means of five biological replicates ± standard deviation. *p ⩽ 0.05; **p ⩽ 0.01.

Live cell laser scanning and 3D holotomographic microscopy

For live cell imaging, BUVEC were seeded into 25.5 × 75.5 mm tissue culture µ-dishes (Ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany) and cultured (37ºC, 5% CO2) until confluence. Thereafter, freshly collected B. besnoiti tachyzoites were allowed to infect the monolayers using an MOI of 3:1. For Ca2+ flux analyses on free B. besnoiti tachyzoites, 1 × 106 fluo-4-loaded tachyzoites were placed into 25.5 × 75.5 mm 8-well tissue culture µ-dishes (Ibidi; Gräfelfing, Germany). Ca2+-related spatial distribution – as mirrored by fluo-4-derived signals – was analysed in both B. besnoiti-infected cells and free B. besnoiti tachyzoites. Laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy (LSCM) was performed by a ReScan Confocal Microscope instrumentation (RCM 1.1 Visible, Confocal NL; Netherlands) equipped with a fixed 50 µm pinhole size and combined with a Nikon Ti2-A inverted microscope and a motorised Z-stage (DI1500, Nikon). The RCM unit was connected to a Toptica (TOPTICA Photonics SE; Germany) iChrome CLE laser with the following excitation wavelengths: 405/488/561/640 nm. Images were acquired via a sCMOS camera (PCO edge) using a CFI Plan Apochromat 60 × lambda-immersion oil objective (NA 1.4/0.13; Nikon). The system was operated by the microscope software NIS-Elements (Nikon; v 5.11). Images were acquired via a z-stack optical series with a step size of 0.4 microns. Finally, 3D live cell holotomography was performed by a 3D Cell Explorer Fluo microscope (Nanolive; Switzerland) at 60 × magnification (excitation wavelength = 520 nm, sample exposure 0.2 mW/mm2 and a depth of field of 30 µm) using LED as light source (CoolLED pE-300ultra; Andover, UK).

Image processing and analysis

Infection rates were calculated from phase contrast images in an observer-blind manner. Fluorescence-based images were analysed with Fiji ImageJ v1.54 using Z-projection and merged channel plugins. In addition, live cell 3D-holotomographic images were analysed using STEVE® software v.2.6 (Nanolive; Switzerland) to obtain a z-stack based on refractive index (RI) of organelles. Furthermore, digital staining was applied according to the RI of tachyzoites and inner organelles.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analyses, GraphPad® Prism 8 (version 8.4.3) software was used. Ca2+ flux changes over time were analysed by area under the curve (AUC) estimation during 370 s after treatment, using the first 50 s prior to stimulation as baseline. Likewise, to accurately illustrate Ca2+ fluxes, baseline correction was performed by subtracting from each data point the average value obtained during the first 50 sec before stimulation. Data description was carried out by presenting the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation. To compare two experimental conditions, the non-parametric statistical Mann–Whitney test was applied. In cases of three or more conditions, Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. Whenever global comparison by Kruskal–Wallis test indicated statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05), Dunn post-hoc multiple comparison tests were carried out to compare treated and control conditions. Outcomes of statistical tests were considered to indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 (significance level).

Results

Infection with Besnoitia besnoiti tachyzoites drives Ca2+ accumulation in host cells

To address whether B. besnoiti infection drives alterations in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, we evaluated total fluo-4-derived calcium signals in lysed B. besnoiti tachyzoite-infected BUVEC cultures throughout merogony. Current data showed a significant enhancement of Ca2+-mediated fluorescence in B. besnoiti-infected BUVEC layers at 24 h p.i. when compared with earlier time points (Figure 1A). Specifically, an increase to 134.01 ± 8.89% (p = 0.001) and to 129.28 ± 6.48% (p = 0.029) was detected when comparing 6 and 12 p.i. with 24 h p.i., respectively. Furthermore, live cell scanning laser confocal microscopy illustrated enhanced Ca2+ signals within B. besnoiti meronts in infected BUVEC at 24 h p.i. (Figure 1B). In non-infected BUVEC, a rather vesicular pattern of Ca2+-related signals was observed in the cytoplasm, whilst Ca2+ signals mainly accumulated in tachyzoites inside meronts in B. besnoiti-infected BUVEC (Figure 1B).

Intracellular Ca2+ and PLC signalling governs Besnoitia besnoiti tachyzoite invasion

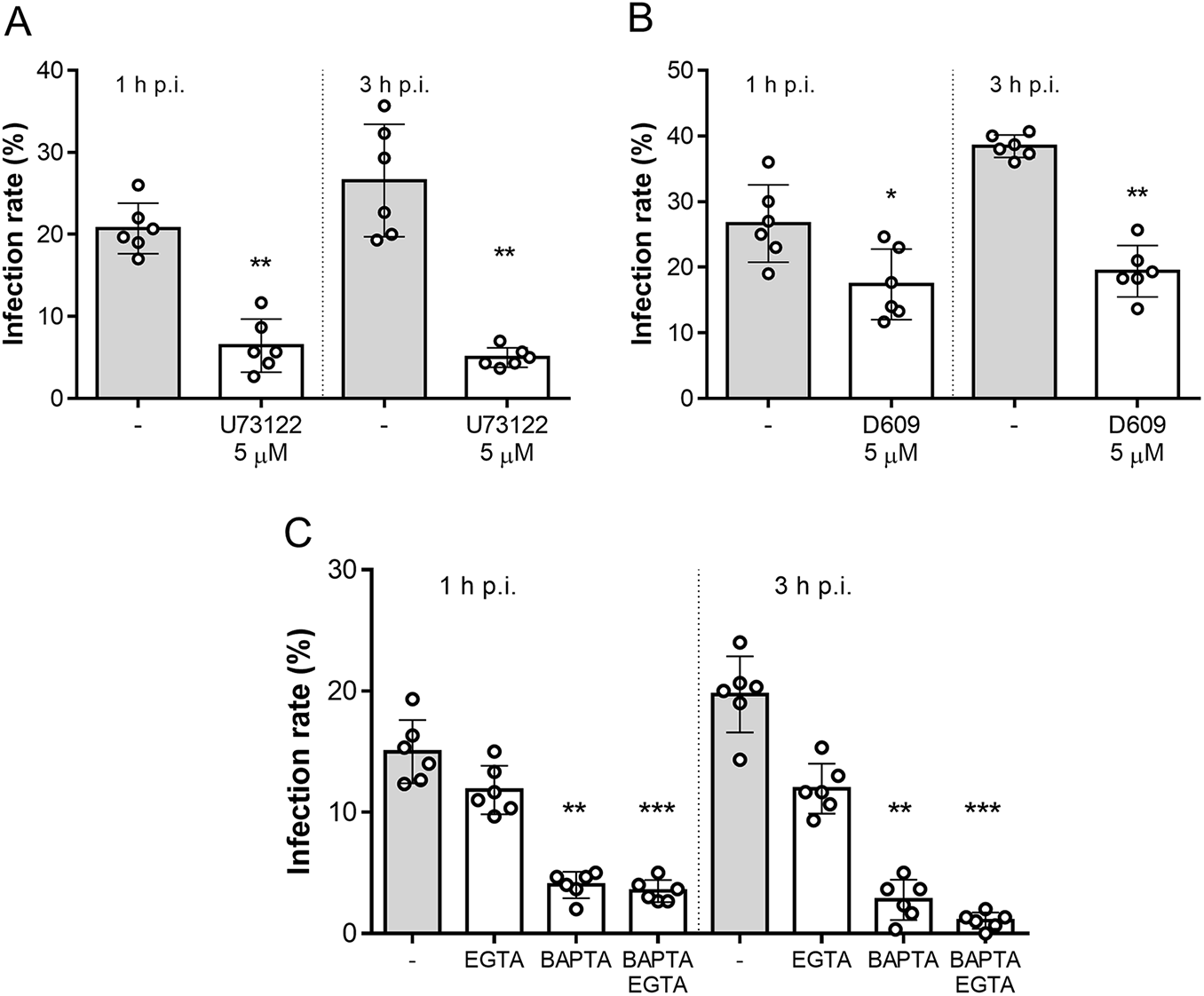

To test whether this mechanism also applies to B. besnoiti, we performed functional invasion assays using B. besnoiti tachyzoites pre-treated with the aminosteroid PLC blocker U73122. As shown in Figure 2A, 5 µM U73122 pre-treatments significantly reduced infection rates, compared with vehicle-treated tachyzoites, by 72.48 ± 11.23% (p = 0.002) and 77.71 ± 8.52% (p = 0.002) at 1 and 3 h p.i., respectively. In line, treatments with another PLC blocker (D609, 5 µM) also significantly blocked parasite host cell invasion as reflected by reduced infection rates at both 1 h p.i. (41.74 ± 16.94%, p = 0.017) and 3 h p.i. (49.26 ± 8.88%, p = 0.002) (Figure 2B). Additionally, we aimed to address the role of intra- and extracellular Ca2+ sources in tachyzoite invasion. Therefore, tachyzoites were treated with BAPTA (50 µM, intracellular Ca2+ chelator) or EGTA (5 mM, extracellular Ca2+ chelator) to block intra- and extracellular Ca2+ sources. In case of EGTA treatments, infection rates were only diminished by tendency [20.62 ± 7.80% (p = 0.49) and 37.63 ± 15.07% (p = 0.86) at 1 and 3 h p.i., respectively]. In contrast, BAPTA treatments strongly affected parasite invasion since infection rates were reduced by 72.53 ± 8.49% (p = 0.005) and 85.42 ± 15.70% (p = 0.003) at 1 and 3 h p.i., respectively. Finally, combinatory treatments with both BAPTA and EGTA significantly blocked parasite invasion by 76.72 ± 3.76% (p = 0.0001) and 94.97 ± 2.76% (p = 0.0007) at 1 and 3 h p.i., respectively (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Besnoitia besnoiti invasion relies on PLC activity and on intracellular Ca2+ stores. Bar graphs illustrate infection rates at 1 and 3 h p.i. of B. besnoiti tachyzoites exposed to U73122 (A) D609 (B) or Ca2+ chelators (C). Bars represent means of six biological replicates ± standard deviation. *p ⩽ 0.05; **p ⩽ 0.01. ***p⩽ 0.001.

Treatments with m-3M3FBS induce a fast but PLC-independent calcium flux in Besnoitia besnoti tachyzoites

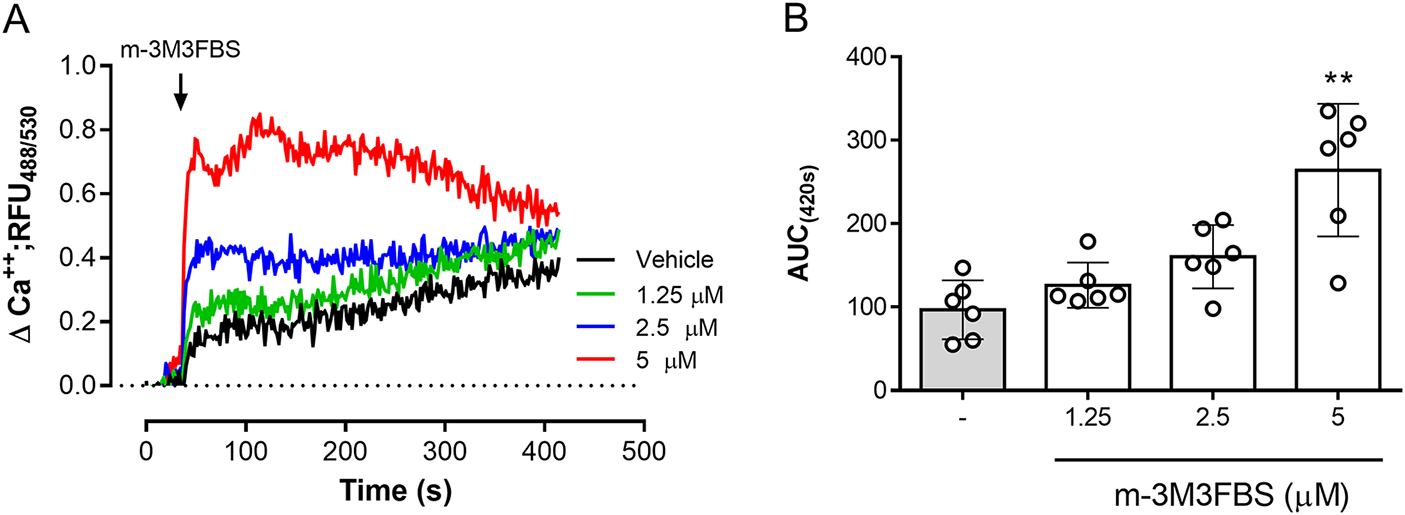

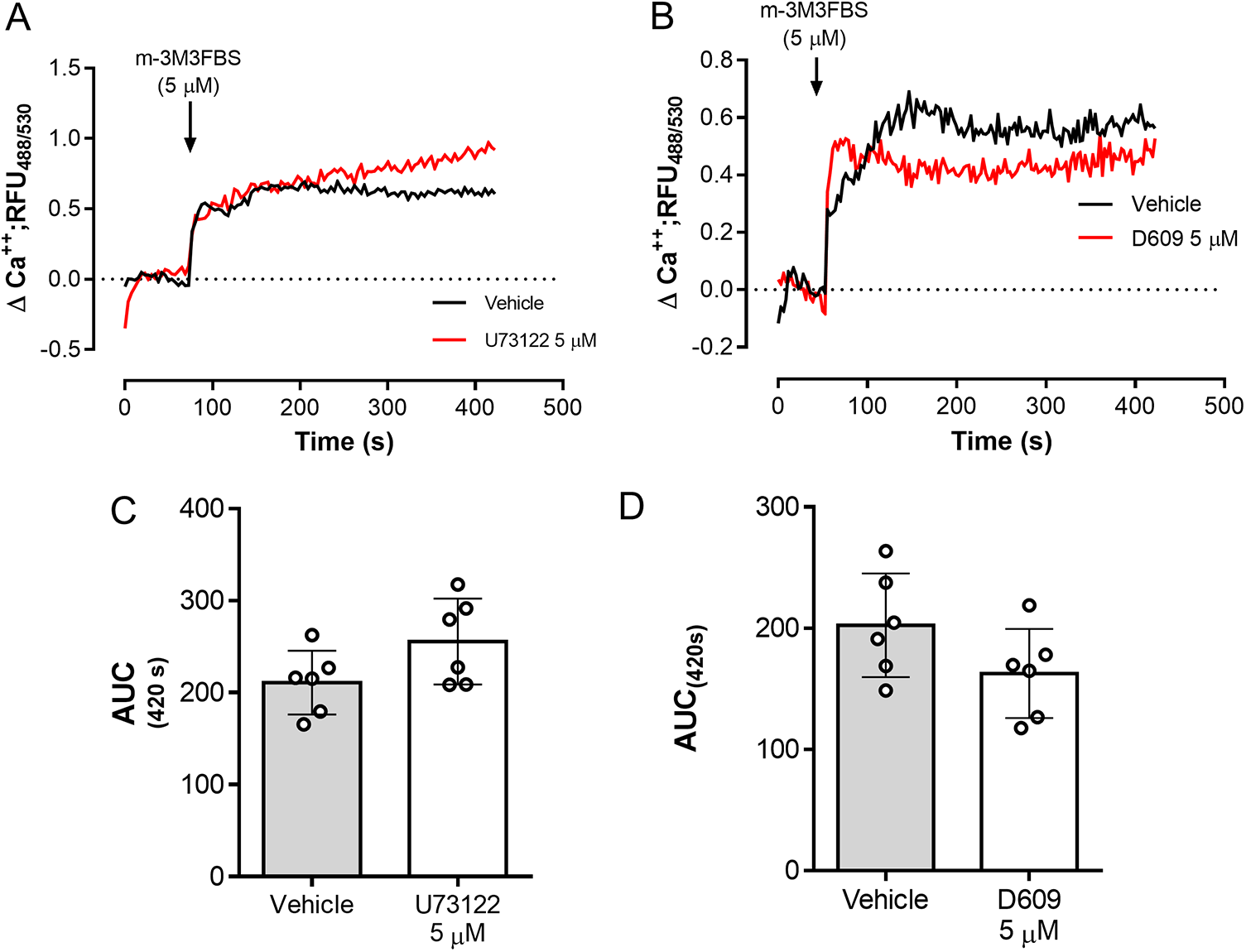

The role of PLC activation in tachyzoite-related Ca2+ flux was addressed by using the PLC-agonist m-3M3FBS (Bae et al. Reference Bae, Lee, Park, Hur, Kim, Heo, Kwak, Suh and Ryu2003). As illustrated in Figure 3A, m-3M3FBS tachyzoite treatments at 1.25-5 µM concentrations induced a dose-dependent Ca2+ flux over time. In addition, AUC analyses revealed an m-3M3FBS-driven, statistically significant increase in Ca2+ fluxes at 5 µM (p = 0.0014) (Figure 3A–B). EC50 calculation stated an effective concentration of 24.7 ± 1.5 µM (Supplementary Figure 1A). Notably, prolonged exposure (240 s) to 25 µM m-3M3FBS concentration also affected tachyzoite morphological integrity as evidenced by live cell 3D-holotomographic microscopy (Supplementary Figure 1B). Finally, to confirm m-3M3FBS specificity in B. besnoiti, we performed functional analyses on fluo-4-loaded B. besnoiti tachyzoites either in the presence or absence of PLC inhibitors (U73122 or D609). Unexpectedly, both compounds failed to interfere with m-3M3FBS-driven Ca2+ flux kinetics or amplitude over time, thereby indicating PLC-independent effects of m-3M3FBS (Figure 4A–B). This observation was quantitatively confirmed by AUC analyses, where no statistically significant differences were found when comparing vehicle or PLC inhibitor-treated tachyzoites (Figure 4C–D).

Figure 3. m-3M3FBS treatments induce a fast and sustained Ca2+ flux in B. besnoiti tachyzoites. (A) Fluorometric registries over time of fluo-4-loaded m-3M3FBS-treated (1.25–5 µM) B. besnoiti tachyzoites. (B) Bar graph showing the AUC at 420 s average ± standard deviation of six biological replicates. ** P ⩽ 0.01.

Figure 4. m-3M3FBS-driven Ca2+ flux in B. besnoiti tachyzoites is PLC-independent. Fluorometric registries and respective AUC of fluo-4-loaded B. besnoiti tachyzoites exposed to m-3M3FBS (5 µM) in the presence or absence of 5 µM U73122 (A, C) or 5 µM D609 (B, D). Bar graphs show the average values ± standard deviation of the AUC at 420 s of six biological replicates. **p ⩽ 0.01.

Discussion

During acute merogonic replication cycles, coccidian parasites like B. besnoiti must actively invade, proliferate and egress from suitable host cells (Black and Boothroyd, Reference Black and Boothroyd2000). In this context, cumulative evidence from T. gondii- and P. falciparum-related data indicates a pivotal role of Ca2+-dependent routes governing these processes in apicomplexan parasites (Lourido and Moreno, Reference Lourido and Moreno2015). Since intracellular parasitism implies a close interaction of two eukaryotic cells, the maintenance of different Ca2+ concentrations in both cell types represents a challenging scenario in vivo. To address this, we performed an analysis on B. besnoiti-infected primary bovine endothelial host cells to be as close as possible to the in vivo situation (Alvarez-García et al. Reference Alvarez-García, Frey, Mora and Schares2013). Current data revealed that at 24 h p.i., infected BUVEC layers show higher fluo-4-driven fluorescent signals than earlier infection time points (i.e. 6 and 12 h p.i.), suggesting that parasite intracellular proliferation is indeed directly linked to increased Ca2+ concentration in infected cell layers. In line, Velásquez et al. (Reference Velásquez, Lopez-Osorio, Pervizaj-Oruqaj, Herold, Hermosilla and Taubert2020) showed that after 6 and 12 h p.i. most BUVEC still contain one and two tachyzoites, respectively, whilst full proliferation of the parasite is achieved at 24 h p.i., leading to the formation of 8–16 tachyzoites/host cell thereby implying that Ca2+-derived fluorescent signal increase indeed is consequence of tachyzoite replication. Current data are in line with findings on N. caninum-infected BUVEC at 24 and 42 h p.i. (Larrazabal et al. Reference Larrazabal, Hermosilla, Taubert and Conejeros2021a), where 3D-holotomography revealed that Ca2+-derived signals accumulated within the intracellular meront and that intracellular N. caninum tachyzoites were the principal source of Ca2+ signals. Likewise, enhanced Ca2+ levels in meronts (72% higher than in host cytoplasm) were detected in T. gondii-infected human epidermoid carcinoma epithelial cells at 24 and 48 h p.i. (Pingret et al. Reference Pingret, Millot, Sharonov, Bonhomme, Manfait and Pinon1996). These findings suggest that B. besnoiti tachyzoites infecting BUVECs should have a similar Ca2+ distribution in time points later than 24 h p.i. Referring to general cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels, apicomplexans like T. gondii, P. falciparum or P. chabaudi share typical concentrations with other eukaryotic cells by 70–100 nM (Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Dluzewski, Catalani, Burting, Hoyland and Mason1996; Moreno and Zhong, Reference Moreno and Zhong1996).

During the coccidian lytic cycle, free-released tachyzoites must actively invade new suitable host cells, which support the parasite’s metabolic requirements (Black and Boothroyd, Reference Black and Boothroyd2000). In this context, PLC-driven signalling is considered essential for host cell invasion by apicomplexans. Nonetheless, considering the absence of IP3R or RyR homologues in these protozoan parasites, the participation of this route in apicomplexans remains unclear (Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Alves, Pereira, Bartlett, Thomas, Mikoshiba, Plattner and Sibley2017). To gain functional insights into PLC-dependent pathways in B. besnoiti tachyzoites, we performed cell invasion assays after pre-treating tachyzoites with the PLC inhibitors U17122 and D609. The infective capacity of tachyzoites was estimated based on infection rates at 1 and 3 h p.i. Our findings indicate that both compounds interfere with the host cell infection, suggesting the involvement of a PLC-dependent pathway in B. besnoiti tachyzoite host cell invasion. However, considering the known off-target effects of U73122 on SERCA in other cell models (Taylor and Broad, Reference Taylor and Broad1998; Macmillan and McCarron, Reference Macmillan and McCarron2010), the observed impact of this compound on the invasion step may also involve PLC-independent mechanisms. Referring to compound D609, its anti-invasive effect was already reported for T. gondii tachyzoites, where respective treatments reduced cell invasion of human MRC5 fibroblasts by 69% but at a considerably higher concentration (100 µM) (Ricard et al. Reference Ricard, Pelloux, Favier, Gross, Brambilla and Ambroise-Thomas1999).

Physiologically, PLC activation triggers cytoplasmic Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, depending on IP3 receptor activation (Berridge, Reference Berridge2016). In non-excitable cells like endothelial cells, this early event of Ca2+ flux promotes the opening of cytoplasmic Ca2+ channels, thereby allowing for extracellular Ca2+entry in a process named store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) (Hogan and Rao, Reference Hogan and Rao2015). Referring to this pathway, we explored the role of intra- and extracellular Ca2+ sources for B. besnoiti tachyzoite invasion by using treatments with BAPTA and EGTA, serving as selective chelators of intra- and extracellular Ca2+, respectively. Current data show that intracellular Ca2+ chelation results in a marked reduction of B. besnoiti infective capacity. In contrast, extracellular Ca2+ chelation by EGTA treatments (5 mM) had no statistically significant effects on infection rates (20.62 ± 7.80% reduction), without inducing any significant effect in BAPTA-treated tachyzoites. Overall, these findings strongly suggest that B. besnoiti tachyzoites mainly rely on intracellular Ca2+ stores to actively invade host cells. In agreement, the pivotal role of intracellular Ca2+ for parasite invasion was also documented for T. gondii tachyzoites by BAPTA treatments (Lovett et al. Reference Lovett, Marchesini, Moreno and Sibley2002; Song et al. Reference Song, Ahn, Ryu, Min, Joo and Lee2004; Del Carmen et al. Reference Del Carmen, Mondragón, González and Mondragón2009). However, the role of extracellular Ca2+ entry during the apicomplexa invasive process remains unclear. In case of T. gondii, EGTA pre-treatments of tachyzoites at double concentration (10 mM) dampened parasite invasion into HeLa cells at 4 and 18 h p.i. (Song et al. Reference Song, Ahn, Ryu, Min, Joo and Lee2004). However, the capacity of EGTA to affect invasion seemed to be Ca2+-independent since T. gondii infectivity was shown to be mainly affected by EGTA-driven extracellular acidification (Lovett and Sibley, Reference Lovett and Sibley2003). This last indicates that further studies are necessary to fully establish the participation of extracellular Ca2+ sources in B. besnoiti invasion.

Even though PLC signalling appears highly crucial in apicomplexan parasites, so far, physiological ligands capable of activating this pathway in resting tachyzoites have not been identified. In this report, we characterised Ca2+ fluxes induced by the only reported pharmacological PLC activator m-3M3FBS (Bae et al. Reference Bae, Lee, Park, Hur, Kim, Heo, Kwak, Suh and Ryu2003). Since – to our knowledge – no information is available on the suitable working concentration of m-3M3FBS for protozoan parasites, we first estimated the respective EC50 concentration (24.7 µM) using Ca2+-driven signals as readout. Of note, 25 µM m-3M3FBS induced cytotoxic effects in B. besnoiti tachyzoites at 3 min post-exposure. However, when applying 5 µM m-3M3FBS, this detrimental effect was absent and respective treatments led to a fast and sustained Ca2+ flux in B. besnoiti tachyzoites, confirming the principal functionality of this compound in these parasite stages. However, when assessing PLC-dependency of m-3M3FBS-driven Ca2+ fluxes by registering Ca2+ fluxes in the additional presence of the PLC inhibitors U17122 and D609, current data revealed that m-3M3FBS-driven Ca2+ flux did not change and therefore seemed PLC-independent. Overall, m-3M3FBS-driven, PLC-independent Ca2+ fluxes were already reported in human neuroblastoma (Krjukova et al. Reference Krjukova, Holmqvist, Danis, Akerman and Kukkonen2004). Furthermore, other PLC-independent effects of m-3M3FBS, such as apoptosis in the pro-monocytic human cell line U937 (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Kim, Park, Choi, Lee, Ryu, Kwak and Bae2005), suggested that data resulting from the use of this compound as PLC agonist must be interpreted with caution and need further investigations.

In summary, we here observed that B. besnoiti tachyzoites accumulate Ca2+ during their intracellular merogony and confirmed intracellular stores as the main Ca2+ sources during host cell invasion. Likewise, functional inhibition of cell invasion by PLC inhibitors suggests that this process is governed – at least partially – by a PLC-dependent mechanism. Finally, m-3M3FBS treatments induced a dose-dependent increase of Ca2+ flux, which was not affected by PLC inhibition in B. besnoiti tachyzoites. Overall, these novel data can be useful for the development of new therapeutic agents, targeting intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and/or PLC-dependent signals in B. besnoiti tachyzoites, to control bovine besnoitiosis; nonetheless, further studies with a larger sample size and/or in vivo experiments are still necessary to establish the suitability of this therapeutic strategy. Likewise, the use of molecular tools, such as shRNA, CRISPR-Cas9 and transcriptomics/proteomics-derived data, represents a valuable opportunity to discover and validate novel targets involved in B. besnoiti Ca2+ homeostasis. In this context, elucidating the mechanisms underlying B. besnoiti Ca2+ homeostasis regulation during both acute and chronic infection, as well as exploring the parasite’s potential ability to modulate bovine host Ca2+ signalling, could provide novel insights into the biology of this neglected parasitosis.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101182.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Christin Ritter and Hannah Salecker for their outstanding technical support. We also are very thankful to Prof. Dr A. Wehrend (Clinic for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Andrology of Large and Small Animals, Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany) for the continuous supply of bovine umbilical cords.

Author’s contribution

CL and IC conceived and designed the study. CL, DG and ZV designed and conducted the experiments. Funding: AT. All authors performed analyses and interpretation of the data, prepared the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

CL was funded by the National Agency for Research and Development [(ANID), DOCTORADO BECAS CHILE/2017 – 72180349].

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.