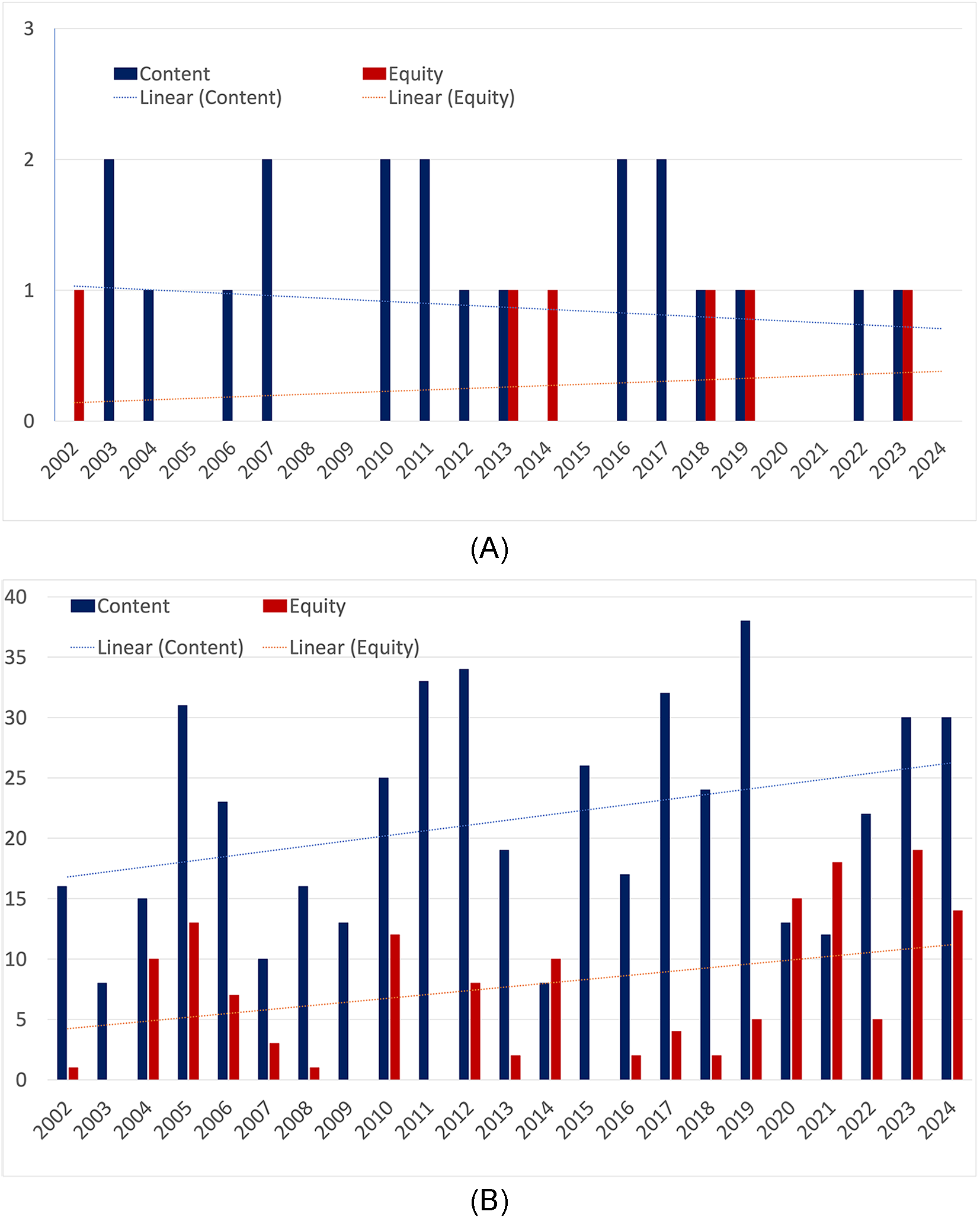

In 2020, Paula England and colleagues argued that decades of movement toward gender equality in the United States had stalled, noting “the degree of segregation of fields of study declined dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s, but little since then” (Reference England, Levine and Mishel2020:6990). Concern with gender equity in anthropological archaeology likewise seems to have stagnated in recent decades (Figure 1). Of the thousands of presentations at the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) annual meeting since 2002, a consistently small number focus on gender, with only a slight upward trendFootnote 1 for presentations on either content or equity issues (sensu Wylie Reference Wylie1997). Similarly, articles on gender are rarely included in American Antiquity, the flagship journal of the SAA. Surprisingly, only a single research article in the history of the journal includes “feminist” in the title (Heitman Reference Heitman2016). While such issues continue to be addressed by a small and significant cohort, the lack of substantial increased engagement suggests gender, and particularly feminist scholarship, has not been integrated into the mainstream of anthropological archaeology (see also Moen Reference Moen2019; Wylie Reference Wylie2007).

Figure 1. Graphs showing the occurrence of papers addressing equity and content critiques in the SAA annual meeting (A) and American Antiquity journal (B) from 2002 to 2024. Articles, papers,and sessions containing a version of gender, women, and feminism in their titles were included in this study. It should be noted that articles in this themed issue were part of a symposium at the 2023 annual meeting and are partially responsible for the peak in equity papers that year.

The consequences of continued gender-based inequity are wide-ranging, including both individual and disciplinary costs. Increasingly, researchers are highlighting the commonality of gender-based discrimination that exists throughout disciplines (e.g., Mattheis et al. Reference Mattheis, Marin-Spiotta, Nandihalli, Schneider and Barnes2022) and is exacerbated by women’s intersectionalFootnote 2 (sensu Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989) identities, including race, class, disability, sexuality, and immigration status, et cetera (see Heath-Stout [Reference Heath-Stout2024a] for a qualitative discussion of the impacts of these intersectional identities on gendered experiences in archaeology). In a recent analysis, Spoon and colleagues (Reference Spoon, Nicholas LaBerge, K. Hunter, Sam, Allison C., Mirta, Bailey K., Daniel B. and Aaron2023) found that across academic disciplines, women are more likely than men to leave their jobs at all stages, even after receiving promotions. Further, women who left were more likely to feel pushed out, while men were more likely to leave for better opportunities. Even when women and other underrepresented individuals do not leave the field, they nevertheless report higher rates of discrimination and harassment (e.g., Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Horton, Bourdreaux, Carmody, Wright and Dekle2018; Simeonoff et al. Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026). Indeed, it is increasingly recognized that harassment is common, particularly in field situations (e.g., Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Mary, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:Chapter 4; Voss Reference Voss2021a, Reference Voss2021b). Unfortunately, it is difficult to assess the experiences of people who have chosen to leave archaeology or limit their engagement with the discipline as a result of these experiences.

Scholars have repeatedly demonstrated that diversity enhances innovation and excellence across multiple disciplines (e.g., Freeman and Huang Reference Freeman and Huang2014; Page Reference Page2019; Swartz et al. Reference Swartz, Palmero, Masur and Aberg2019). As discussed by Fong and colleagues (Reference Fong, Ng, Lee, Peterson and Voss2022:235), “Archaeologists are not neutral observers of the past; we actively shape narratives of the past that simultaneously reflect and impact the present.” Drawing on feminist standpoint theory (e.g., Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Collins Reference Collins, Garry and Pearsall1996; Wylie Reference Wylie2007, Reference Wylie2012), Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a:145–148), to take one example, has outlined the ways in which individuals’ intersectional identities shape the archaeological research they pursue and thus how a lack of diversity limits knowledge production. Arguing explicitly for the importance of a feminist archaeology, Wylie (Reference Wylie2007:213) makes a similar point, noting that

what a feminist perspective brings to bear is a critical, theoretically and empirically informed, standpoint on knowledge production. This is embodied . . . in sustained analyses of how the culture and institutions of archaeology reproduce gender-normative conventions not just in the questions asked and variables considered, but in tacit assumptions that structure the terms on which these questions, these aspects of the cultural subject, can be engaged (Wylie Reference Wylie, Figueroa and Harding2003).

As stated powerfully by Agbe-Davies (Reference Agbe-Davies2002:27), greater diversity in archaeology “is more honest, more likely to be critical, aware of its own limits,” or, as outlined by Lyons and Supernant (Reference Lyons, Supernant, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020:7), comes “from a place of profound strength.” Greater consideration of the positionalities of our practitioners is thus not only beneficial but necessary to create robust, inclusive, and accurate pictures of the past.

The goal of this themed issue is to better understand gender inequality in contemporary archaeological practice, highlight how subtle forms of exclusion tied to ideas of fit and prestige affect women’s experiences, and suggest routes to effect meaningful changes in the discipline. We suggest an important component in moving forward is reconceptualizing the causes and consequences of intersectional gender-based inequalities in our field and moving from a leaky pipeline metaphor to a garden metaphor. From here, we offer suggestions for pushing through the current stagnation to a more just and equitable future for an archaeology inclusive of all individuals (women, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, disabled, etc.). Drawing on insights from other fields and the articles within this themed issue, we provide recommendations on how the discipline, institutions, and individuals can improve gender equity, encourage diversity of thought, and thereby strengthen the field of archaeology.

From Leaky Pipelines to Watering Cans: Introducing a Garden Metaphor

In line with the critiques of the leaky pipeline model outlined in the introductory article (Kurnick and Fladd Reference Kurnick and Fladd2026; see also Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a), we believe the employment of alternative metaphors is important to better capture the realities of gender inequality in archaeology and particularly to emphasize that the loss of certain scholars is an active rather than passive process. We are not the first to suggest a different metaphor in archaeology. Some have noted parallels with games of chutes and ladders (Crawford and Windsor Reference Crawford and Windsor2021:17–18), and, building on the work of Sterling (Reference Sterling2021) and Stevens and colleagues (Reference Stevens, Masters, Imoukhuede, Haynes, Setton, Cosgriff-Hernandez and Bell2021), Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a) cogently argues for the use of a mountain-climbing metaphor. Drawing on interviews with archaeologists studying Latin America, historical archaeology, and Mediterranean archaeology, she considers the ways different advantages (e.g., expensive hiking boots), microaggressionsFootnote 3 (bumpy paths), other climbers (either supportive companions or saboteurs ready to push you off a cliff), and structural issues (like having a map) may lead some to an easier climb than others (see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:Figure 1.3). Building on this reorientation, we suggest another metaphorical shift that highlights what we hope our discipline can become: a garden metaphor.

Commonly used in education, this metaphor encourages teachers to view their role as gardeners who create “optimal conditions for development,” meeting their students’ needs and supporting their individual growth (Mintz Reference Mintz2018:416; see also Gopnik Reference Gopnik2016). In a related vein, the idea of “seeding the garden” has been adopted by journal editors seeking to nurture scholarship in education (Dean and Forray Reference Dean and Forray2017, Reference Dean and Forray2020). They argue that support for scholarship and authors, as well as advocacy on the part of journal editors to increase transparency about the publishing process and elevate recognition of editors’ service, are important components in “cultivating our garden’s growth” (Dean and Forray Reference Dean and Forray2020:123). Similarly, conservationists have relied on a garden metaphor to move beyond the dichotomization of nature and culture in restoration ecology (e.g., McEuen and Styles Reference McEuen and Styles2019). The blurring of this divide emphasizes the ways in which human actions, past and present, may be necessary to ensure positive outcomes, such as Indigenous fire management practices used to buffer climate change impacts (Roos et al. Reference Roos, Guiterman, Margolis, Swetnam, Laluk, Thompson and Toya2022).

The strengths of garden metaphors are varied and particularly applicable to reframing inequity in archaeological practice away from a passive leaky pipeline conceptualization (Figure 2). A garden metaphor implies the presence of “gardeners” who guide growth and shape the outcome (see McEuen and Styles Reference McEuen and Styles2019:1195). While gardeners may represent particularly influential individuals in the field, they can also symbolize institutions and forces in the discipline and broader society that transcend any individual actor. Although plumbers may serve as a metaphorical equivalent to gardeners, the conceptualization of individuals as water flowing through a pipeline is unidirectional, constrained, and homogenous (see also Pawley and Hoegh Reference Pawley and Hoegh2011; Petray et al. Reference Petray, Doyle, Howard, Morgan and Harrison2019); plants better represent the variability of archaeologists within our discipline, who start from various places and soils, require distinctive support, and flourish in different ways. Just as archaeologists do not experience the discipline in a vacuum, plants may influence one another actively within a garden, even when those acts are unintentional. Some plants may consume all the water within their reach to ensure their own survival, leaving nearby sprouts parched and dry. Other plants may unintentionally create shade that helps ferns grow but harms fruiting plants. More positively, some plants work in symbiosis, the native North American “three sisters” (maize, beans, and squash) being a prime example (see Kimmerer Reference Kimmerer2013). Maize stalks provide vertical support for climbing pole beans. Vining squash and its large leaves supply ground cover in the garden, minimizing weed growth and reducing soil moisture evaporation. Beans in turn fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil for maize and squash to uptake. The use of all three together is an example of intercropping, as opposed to monocropping. Grown together, they enhance soil quality, which enhances plant growth, which in turn enhances soil quality, and so on. Grown alone, they would not thrive to the same degree. Importantly, positive effects happen at both the macro- and microscopic levels, appearing both as morphological and cellular, visible and invisible, individual and structural.

Figure 2. One possible rendering of the garden metaphor. Drawing by Sasha Buckser.

As with the leaky pipeline, some have critiqued the use of a garden as a metaphor as it implies colonization over the landscape and privileges certain ideas of nature and priorities for a space (e.g., Nash Reference Nash2014; Zipory Reference Zipory2020). One response to these critiques has been to emphasize that “gardening is not an exercise in control, but rather in caring” (McEuen and Styles Reference McEuen and Styles2019:1195; see also Janzen Reference Janzen1998). The tension that exists between colonialism and care is precisely why we feel this metaphor aptly captures the issues with equity in our discipline (see also Supernant et al. Reference Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020). Archaeology, and academia more broadly, exists within colonial systems designed to support the success of a very narrow type of scholar: wealthy, white, male, nondisabled, neurotypical, with no caregiving responsibilities. Others are defined inherently by not being these things (Cobb and Crellin Reference Cobb and Crellin2022:270). A garden metaphor fits the ways in which neat rows of identical plants were cultivated and encouraged to thrive within this system. However, the metaphor is flexible enough for us to reconceptualize what we mean by “garden” and instead advocate for a “wild” or “forest” garden that supports a range of plants with both different strengths and different needs (sensu Gordon Reference Gordon2025). Instead of defining these differences as “weeds” out of place (sensu Cresswell Reference Cresswell1997), we can highlight the benefits of the biodiversity created when many different types of plants are able to thrive and focus on creating a rich and diverse archaeology ecosystem.

A strictly laid-out garden with rows of identical plants (monocropping) may appear clean and tidy but will deplete the soil of necessary nutrients if repeated year after year. Similarly, narrow definitions of value and success in archaeology result in a standardized and homogenous discipline that ultimately creates an equally narrow view of the past that misses the diversity of human experience (see Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Medin, Lee, Bang, Bishop and Lee2014). Our recommendations for (and requests of) the discipline are to broaden our definition of a successful garden and recognize that creating space for different plants to succeed also requires an understanding that success itself may look different than it has in the past.

Gender Equity Action Items: Recommendations and Requests

Recommendations for improving equity in archaeological practice are not new. Both organizations and individuals, often in positions such as journal editor (e.g., Rautman Reference Rautman2012), have proposed a number of suggestions over the years. Following a 2017 report, the SAA Task Force on Gender Disparities in Archaeological Grant Submissions published a coauthored article summarizing their findings and making 16 recommendations—six for funding agencies, five for applicants, and five for the SAA (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018). A few years later, in 2022, the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) published a code of practice that included a section on “Safe Work Environment, Equality and Inclusion” with a series of 11 guiding principles (European Association of Archaeologists 2022). Where the EAA Code of Practice emphasizes broad ethics and initiatives for disciplinary practice, the SAA task force provides actionable steps to address gendered patterns of grant submission. Despite the differences in scope and tone, recommendations for funding agencies by the SAA task force overlapped in several areas with the guiding principles outlined by the EAA Code of Practice, including calls for greater transparency, increased collection of data, and ensuring equal access. The SAA task force additionally recommended five individual changes in approach for applicants, such as revising and resubmitting proposals, building larger research teams, and seeking more information and examples from grant program officers and colleagues (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018:383). Both demonstrate efforts by the main American and European archaeology societies to address inequities in the discipline.

Most recently, a study of anthropological and archaeological grant-making commissioned by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and Social Science Research Council provided recommendations at various scales for building a more equitable funding structure (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024b). Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024b:6–7) distributed a survey to members of the four subfields of anthropology to understand the intersections of demographics, research foci, and funding experiences. Her survey methodology revealed important relationships between different identities in anthropology and specifically highlighted the experiences of Black and Indigenous anthropologists (Reference Heath-Stout2024b:14–15). Heath-Stout also provides a series of recommendations—a narrative containing advice for funding agencies (Reference Heath-Stout2024b:15–16) and a table providing broad recommendations to all anthropologists, mentors of graduate students and early-career researchers, administrators of departments/programs, professional organization staff and leadership, and reviewers (Reference Heath-Stout2024b:16–17). While focused on funding specifically,Footnote 4 Heath-Stout’s suggested actions align with the ethos of care and equity we advocate for throughout this piece.

Here, we build on these frameworks through an attempt to address the various levels at which gender inequality persists in archaeological practice broadly. While acknowledging the issues with sexual harassment and assault in the discipline (e.g., Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Mary, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Voss Reference Voss2021a, Reference Voss2021b), we focus on the ways more subtle and often harder-to-identify gender-based discrimination impacts women’s roles in the field. Critically, we do not advise women and other excluded individuals to somehow do more with their limited time (see also Ike et al. [Reference Ike, Miller and Hartemann2020] for a discussion of the exhaustion felt by Black academics and archaeologists). Compounding factors such as expectations from mentees (El-Alayli et al. Reference El-Alayli, Hansen-Brown and Ceynar2018), invisible service labor (Reid Reference Reid2021), and lack of credit for work (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Glennon, Maurciano-Goroff, Berkes, Weinberg and Lane2022) create continual barriers to gender equity when the impetus for change is placed on the excluded parties. We instead focus on shifts that the entire discipline could undertake to create meaningful change. Or, as stated succinctly by Laursen and Austin (Reference Laursen and Austin2020:22), “Fix the System, Not the Women.”

While we aim for inclusivity, we nevertheless face limitations with the availability of data. As noted by Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a:5), “Multi-issue equity critiques, as well as critiques of racism, heterosexism and cissexism, ableism, and classism are less numerous, less commonly published in peer-reviewed journals, and more commonly based on qualitative research or on the authors’ personal experience rather than quantitative data” (see also Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024b). Information on intersectional identities can thus be difficult to access, and investigations focused mainly on gender inevitably obscure important distinctions in the range of women’s experiences. We recognize, as illustrated by a recent volume edited by Sandra L. López Varela (Reference López Varela2023), the various ways intersectional identities have influenced women’s experiences in archaeology across the world. Additionally, important pieces that forefront the experiences of Black (e.g., Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2002; Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021; Franklin Reference Franklin1997; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020; Ike et al. Reference Ike, Miller and Hartemann2020; White and Draycott Reference White and Draycott2020), Indigenous (e.g., Atalay Reference Atalay2012; Laluk et al. Reference Laluk, Montgomery, Tsosie, McCleave, Miron, Carroll and Aguilar2022; Nicholas and Watkins Reference Nicholas and Watkins2024; Van Alst and Shield Chief Gover Reference Van Alst and Gover2024), queer (e.g., Blackmore Reference Blackmore2011; Dowson Reference Dowson2000; Eichner Reference Eichner2025; Moral Reference Moral2016; Rutecki and Blackmore Reference Rutecki and Blackmore2016; Springate Reference Springate, Orser, Zarankin, Funari, Lawrence and Symonds2020; Voss Reference Voss2000), and Asian American (Fong et al. Reference Fong, Ng, Lee, Peterson and Voss2022) archaeologists provide invaluable guidance on confronting the histories of the discipline and moving forward more inclusively. Where possible, we have highlighted the compounding barriers and acts of exclusion faced by women who face marginalization along more than one axis of their identity. We also highlight ways in which recommendations may be tailored to be inclusive of women also confronting racism, classism, ableism, and other forms of sexism and gender discrimination. We thus do not suggest a one-size-fits-all model to solve the range of issues faced across the discipline.

Relatedly, the majority of the research on gender equity focuses on academia, making suggestions the easiest to translate to academic archaeology contexts (see Simeonoff et al. Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026). We have attempted to broaden from the case studies presented to make recommendations inclusive of archaeologists working in cultural resource management (CRM) and governmental agency positions, although there are a handful of recommendations that remain firmly rooted in the academic experience. We do not, however, make recommendations on teaching or training but encourage readers to refer to the thoughtful guidance previously published on such issues as decolonizing and diversifying syllabi and classrooms (e.g., Craven Reference Craven2021; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020; Sundal Reference Sundal2025; Surface-Evans Reference Surface-Evans, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020) and improving field school access and safety (e.g., Colaninno et al. Reference Colaninno, Beahm, Drexler, Lambert and Sturdevant2021; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Meehan, Klehm, Kurnick and Cameron2021; Heath-Stout and Hannigan Reference Heath-Stout and Hannigan2020). Overall, we focus our recommendations to address issues of fit (e.g., Leighton Reference Leighton2020; Tholen Reference Tholen2024), prestige (e.g., Beck et al. Reference Beck, Gjesfjeld and Chrisomalis2021), and the hysteresis of habitusFootnote 5 outlined in the introductory article (Kurnick and Fladd Reference Kurnick and Fladd2026) to make active interventions at the disciplinary, institutional, supervisory, and individual levels.

Discipline-Level Recommendations

1. Standardize authorship expectations in archaeology. In a discipline that spans the humanities and the natural sciences, assignments of authorship vary widely and often privilege a handful of individuals (Kawa Reference Kawa2022). Oas and colleagues (Reference Oas, Hoppes, Fladd and Kurnick2026) find men benefit from coauthorship teams to a greater extent than women do (see also Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Castro and Teruel2025; Sarsons et al. Reference Sarsons, Gerxhani, Reuben and Schram2021). In particular, the practice of “honorary authorship,” naming an individual who contributed little to the paper, may inflate the records of certain individuals, likely those who seem to “fit” disciplinary expectations (Reynders et al. Reference Reynders, ter Riet, Di Girolamo and Malicki2022). Alternatively, hired laborers, field school students, field technicians, and others are frequently excluded from authorship lists entirely and may even be missing from the acknowledgments (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:170; Leighton Reference Leighton2015, Reference Leighton2016; Mickel Reference Mickel2019, Reference Mickel2021). Notably, women are less likely than men to be included as authors on papers across the sciences (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Glennon, Maurciano-Goroff, Berkes, Weinberg and Lane2022).

Many high-impact journals now require contributions by each author to be specified, but archaeologists tend to pay little attention to these footnotes, and there exist no discipline-wide norms for authorship (Ouzman Reference Ouzman2023). This fact is particularly important given that coauthorship “can be a function of things other than intellectual contribution” (Ponomariov and Boardman Reference Ponomariov and Boardman2016:1942). Journals in archaeology could offer specific guidance for ethical authorship ascription, something that would decrease honorary authorship and increase the inclusion of individuals too often forgotten in the publication process. In CRM positions, early-career employees could be encouraged and supported to contribute as authors to technical reports, providing an avenue to build their skill set and résumés in the process. Expectations regarding transparency of credit—whether individuals will be acknowledged or named as coauthors—should also be clearly shared at the outset of projects of all kinds. Further, archaeology organizations, including the SAA, could offer guidelines on how to consider and interpret different types of authorship in hiring and promotion decisions and particularly how to assess reports and articles based on type of contribution.

2. Establish clear equity expectations for conference sessions, journal issues, and field crews. As noted throughout the themed issue (Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Kurnick, Fladd, Evans, Garcia and Simeonoff2026; Oas et al. Reference Oas, Hoppes, Fladd and Kurnick2026; Ponce et al. Reference Ponce, Escobar and de León2026) and in previous work (e.g., Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020, Reference Heath-Stout2024a; Tushingham et al. Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017), women and other underrepresented individuals are generally not invited to present their research, and are not credited for their labor, in the same way as white cisgendered men. Conference organizers, journal editors, and others in positions of power should monitor these disparities and push to ensure equity. Journal editors, for instance, can more systematically track submissions, as many have done in the past (e.g., Hanscam and Witcher Reference Hanscam and Witcher2023; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020; Rautman Reference Rautman2012; Watts Reference Watts2024), share those data publicly, and invite contributions from members of underrepresented groups. SAA editors did jointly commit to increase representation in their journals in 2020 (Gamble et al. Reference Gamble, Martin, Hendon, Santoro, Herr, Rieth, van der Linde, Rodning, Hegmon and Birch2020), and an assessment of the impact of that commitment five years later would be insightful. Conferences could also set guidelines for organizers regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion. Symposia that lack diverse speakers could be required to provide an explanation and receive a waiver if a special exemption is warranted. The ability to solicit papers for organized symposia via a web portal instituted by the SAA in the past few years is an excellent start to ensuring greater equity at the conference, and perhaps more sessions, particularly those lacking equity in their initial papers, should be required to be posted publicly. In field settings, ensure field crews are inclusive and welcoming, and crew chiefs are not allowed to regularly give preference to friendship circles. Ultimately, opening the door for people outside of friend networks (sensu Leighton Reference Leighton2020) could substantially improve representation across our discipline, broadening the types of gardens cultivated.

3. Focus available funding on expanding access to conferences for underresourced and underrepresented scholars. As documented by Ponce and colleagues (Reference Ponce, Escobar and de León2026), access to avenues of prestige remain especially limited for women in the Global South (see also Ike et al. Reference Ike, Miller and Hartemann2020). Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a) has also highlighted the way economic class predicates access to opportunities in archaeology (see Heath-Stout and Hannigan [Reference Heath-Stout and Hannigan2020] for a discussion of field school access). The current suite of scholarships, meeting access grants, and reduced registration fees offered by organizations such as the SAA provides an excellent start; we encourage expanding these funding opportunities, broadly advertising their availability within the field, and ensuring funds are dispersed promptly, so that individuals are not forced to pay for attendance up front. Additionally, childcare and funding to support travel for dependents should be available at meetings to ensure caregivers can consider attending (see also Llorens et al. Reference Llorens, Tzovara, Bellier, Bhaya-Grossman, Bidet-Caulet, Chang and Cross2021). Research consistently shows that caregiving responsibilities and housework fall disproportionately to women (Gender Equity Policy Institute 2024), and funding for dependent travel and free or low-cost childcare increase the feasibility of attending conferences. Finally, journals or organizations could support publication by providing access to free or reduced-cost services, such as translation or map/figure production, for authors from underresourced institutions to encourage greater representation of diverse voices in international outlets. For instance, The Mayanist, an open-access journal focused on the Maya (https://www.goafar.org/themayanist), publishes all articles in both Spanish and English and provides translation services. More journals could make an effort to provide translation services, particularly for the language spoken within the region of study, and organizations could support the creation of additional e-communities focused on connecting individuals with certain skill sets, such as geographic information systems (GIS) cartography production, with potential coauthors.

Institution-Level Recommendations

1. Set standards for equality in hiring, retention, and promotion practices. While inequities in hiring have improved in recent years, hiring practices remain problematic, and many workplaces continue to suffer from stark gender imbalances. Indeed, the most prestigious positions remain the least equitable (Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Castro and Teruel2025). Studies demonstrate that women are more likely to experience gender harassment when they work in gender-imbalanced workplaces (Kabat-Farr and Cortina Reference Kabat-Farr and Cortina2014) and are more likely to leave academia owing to workplace climate rather than work–life balance (Spoon et al. Reference Spoon, Nicholas LaBerge, K. Hunter, Sam, Allison C., Mirta, Bailey K., Daniel B. and Aaron2023). One proposed solution has been the inclusion of more women to insulate against negative experiences; however, women, particularly white women, often uphold systemic inequality to preserve or advance their own privilege (e.g., Berdahl and Bhattacharyya Reference Berdahl and Bhattacharyya2024; Simpson Reference Simpson2004). Further, Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a:6) has noted that the increase in gendered representation in archaeology consists “overwhelmingly of straight cisgender white women” and thus has not accomplished “a more holistic move toward diversity.”

Continuing to expand on the progress made in archaeology will require not only the hiring of women with a range of intersectional identities, but their retention and promotion, changes that must be implemented by the leadership tiers of companies, agencies, and higher education institutions. Brodkin and colleagues (Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011:554) recommend that “cluster hiring—bringing in a critical mass of faculty and graduate students of color—is the single most important practice for creating the safe and welcoming climate needed to change the status quo.” Additionally, increasing pay transparency has the potential to allow underrepresented individuals to better advocate for themselves, an issue that spans work sectors in archaeology. Pay is cited by Simeonoff and colleagues (Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026) as the main reason people consider leaving archaeology, and better and more equitable compensation may both encourage people to stay in the discipline and allow those without fiscal safety nets to consider the career path (for a discussion of intersections with class, see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a, Reference Heath-Stout2024b). While pay transparency is becoming more common in certain states and among public academic institutions, information on retention offers or raises is often less available. Among faculty, women and other underrepresented individuals are less likely to receive retention offers across the board (White-Lewis et al. Reference White-Lewis, O’Meara, Mathews and Havey2024). In addition to providing these data transparently, institutions’ human resource offices could assign an advocate who has all data on pay and raises to advocate for individuals equitably and monitor raises to ensure equal pay for equal work.

2. Implement or expand mentoring programs within institutions. Good mentorship can drastically change the experiences of women and members of other excluded groups in archaeology (see Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:112–114, 148–154; Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Munoz and Hernandez2023). Institutionally organized mentorship is often viewed as more egalitarian than individualized mentorship relationships (Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008:223–224). Involvement of senior faculty and employees in training and mentorship programs that increasingly put people from different backgrounds into close contact can be an effective approach to reducing bias (Dobbin and Kalev Reference Dobbin and Kalev2018:52). Women often prefer other women as mentors (Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Castro and Teruel2025; Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008) and may have more successful careers when paired with a woman mentor (Canaan and Mouganie Reference Canaan and Mouganie2021; Gaule and Piacentini Reference Gaule and Piacentini2018). Currently, mentorship often falls disproportionately to scholars of color (Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011), creating barriers to success in a discipline that emphasizes productivity over care (see also Supernant et al. Reference Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020). Training on effective mentorship should be provided regularly by colleges, departments, companies, and agencies and be required of all supervisors, and the efforts put into such programs need to be valued by the institution in considerations of promotion and raises, as noted in the following recommendation.

3. Rethink how value is defined and how success is measured. The ways work is valued and success is measured and tracked for both hiring and promotion involve inherent biases, privileging certain types of scholars and scholarship (Laursen and Austin Reference Laursen and Austin2020; Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008). Concerningly, for example, women of color are the least likely group of faculty to receive tenure despite comparable productivity (Armstrong and Jovanovic Reference Armstrong and Jovanovic2017). One likely contributing factor is the well-documented fact that women, and particularly women of color, tend to take on higher service and mentorship loads for little compensation or credit (e.g., Ahmad Reference Ahmad, Johnstone and Momani2024; Domingo et al. Reference Domingo, Gerber, Harris, Mamo, Pasion, Rebanal and Rosser2022; Misra et al. Reference Misra, Lundquist, Holmes and Agiomavritis2011). Analyzing results of their survey on behalf of the American Anthropological Association’s Commission on Race and Racism in Anthropology, Brodkin and colleagues (Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011) pinpoint the ways the offloading of unvalued service work on women of color contributes to their marginalization as scholars and creates barriers to advancement in academia. In particular, the authors note, “Expecting numerical as well as racial minorities to carry the workload of enhancing racial diversity places undue burdens on faculty of color while freeing white faculty from responsibility” (Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011:550). Similarly, Ike and colleagues (Reference Ike, Miller and Hartemann2020:13) speak powerfully of the exhaustion felt by Black archaeologists asked to do the work of “cleaning up the reputations of the institutions that continue to exploit us and the communities we study.” A compounding factor is that while career pauses for childcare are technically permitted, these pauses are often used as evidence that an individuals are less committed to their careers (Laursen and Austin Reference Laursen and Austin2020). Comprehensive reevaluations and reassessments of how value is apportioned within institutions should be undertaken with the explicit goal of identifying who benefits from the system and who is disadvantaged by the current metrics. With this information in hand, institutions should reconsider how value is apportioned to ensure all contributions are recognized and weighed in equitable manners, ensuring archaeology can support the inclusive and equitable garden we aspire to become.

Additionally, metrics that measure impact in archaeology and other disciplines often rely on problematic standards. For instance, the common use of the h-index in academia to understand a researcher’s standing in the field measures only how often the researcher is cited and thus the potential utility of the work to other researchers. This number does not measure the “importance or quality” of said work (Barnes Reference Barnes2017:489) and may instead speak to the size or influence of an individual’s friend network (sensu Leighton Reference Leighton2020). In archaeology, these issues are particularly salient, as Hutson (Reference Hutson2002, Reference Hutson2006) has repeatedly found that women are undercited when compared with their male colleagues given their scholarly output, a pattern repeated in other disciplines (e.g., Dworkin et al. Reference Dworkin, Linn, Teich, Zurn, Shinohara and Bassett2020) and reinforced by gendered writing tendencies (e.g., Woolston Reference Woolston2020). This issue is compounded for women with intersectional marginalized identities, such as the documented underciting of Black women in anthropology (e.g., Smith and Garrett-Scott Reference Smith and Garrett-Scott2021; Williams Reference Williams2022). Further, the overvalorization of fieldwork creates problematic expectations of what counts as “real” archaeology (see Leighton Reference Leighton2020; Moser Reference Moser2007; Simeonoff et al. Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026). An important step is expanding the discipline to value work done both in and beyond the field and actually reward efforts beyond publications, grants, cutting costs, and meeting project deadlines. For example, safety and crew satisfaction could be measured for supervisors in CRM, and community-based research, mentorship, and “diversity duty” (sensu Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011) could be weighted more heavily in academia. While many companies and institutions already claim to consider these factors, attaching meaningful outcomes, such as pay bonuses or raises, course releases, or travel funding, could lead individuals to take them more seriously and ensure institutions move beyond performative gestures.

4. Rework responses to gender discrimination and harassment within the institution to demonstrate commitment to equity. Women often feel (Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008), and data suggest (Goltz Reference Goltz2005; Rosenberg et al. Reference Rosenberg, Barton, Bradford, Bell, Quan, Thomas, Walker-Harding and Slater2023), that pursuing official grievance channels within institutions leads to ineffective responses and potentially creates social stigmas or psychologically unsafe conditions for the harmed party themselves (Tauber Reference Tauber2022). A common solution or sanction for discrimination is additional bias training; however, research shows that diversity training alone is ineffective, particularly when the issue stems from a “willful resistance to know” (Applebaum Reference Applebaum2018:130; see also Dobbin and Kalev Reference Dobbin and Kalev2018). Changing sanctions to indicate a greater institutional commitment to equity could encourage reporting of discrimination. One potential is implementing sanctions equivalent to scientific misconduct for individuals who create environments of discrimination (Greider et al. Reference Greider, Sheltzer, Cantalupo, Copeland and Dasgupta2019; Llorens et al. Reference Llorens, Tzovara, Bellier, Bhaya-Grossman, Bidet-Caulet, Chang and Cross2021:Table 2). As it currently stands, sanctions rarely impact scholarship, which carries the greatest value in academia. Institutions at the department, college, or university level could implement research sanctions, such as barring individuals from travel funds, internal grant opportunities, or other research monies internally available. For CRM or agencies, suspensions without pay and termination for repeat offenses would communicate the seriousness of discrimination and bullying. Both the SAA and the Register of Professional Archaeologists have mechanisms in place to handle certain extreme cases of harassment but could increase transparency about individuals who have been excluded. Currently, official grievance channels often place much of the burden on the harmed party and provide minimal protections against retaliation until after the fact. Institutions should assume more responsibility for ensuring not only the physical but also the mental and emotional safety of reporters, as well as more proactive protections against retaliatory behavior, such as clearly outlining banned activities for perpetrators. Such changes may not only encourage women or others dealing with discrimination to report but also discourage poor behavior from researchers concerned with losing access to valued resources.

Supervisory-Level Recommendations

1. Provide regular information about protocols, procedures, and safety issues to everyone, whether or not you believe the information is personally relevant. As noted by Simeonoff and colleagues (Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026), individuals are often put into uncomfortable positions when expected to tolerate inappropriate behaviors or requests in the field early in their careers. Too often a mentality of “this must be how it’s done” encourages women and others who are endeavoring to “prove themselves” to put up with poor behavior that could have been avoided if standards were explicitly set and frequently referenced (see also Leighton Reference Leighton2020). Publicly sharing expected standards of behavior can help empower individuals to speak up when lines are crossed. In general, ensuring that individuals are provided with all potentially relevant information about a project, including physical expectations, can allow individuals to identify potential needs for accommodations ahead of time and establish a plan prior to being in the field. Likewise, safety for individuals with certain identities can be concerning in ways that “unburdened” archaeologists may not recognize, depending on the location of the project (see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:Chapter 6). By proactively sharing information about potential physical, emotional, and mental demands; health risks; and safety concerns for projects supervisors can help determine the appropriate support for individuals on their field crews (or lab groups in some cases) to avoid potentially dangerous situations and allow all archaeologists to flourish.

2. Consider equity and equitable treatment as a part of annual evaluations or performance reviews and offer corrective feedback as necessary. In setting performance expectations, consider what equity might look like in your department, team, or crew. Highlight and reward efforts toward diversity, inclusion, and safety in annual evaluations. Ensure academic service work, logistics, and emotional labor is being recognized, documented, and equally distributed, rather than falling largely to women and people of color (see Domingo et al. Reference Domingo, Gerber, Harris, Mamo, Pasion, Rebanal and Rosser2022; Guarino and Borden Reference Guarino and Borden2017). As an example, Ike and colleagues (Reference Ike, Miller and Hartemann2020:Figure 1) share an “emotional labor invoice” to acknowledge the work regularly done by Black archaeologists. Take failure to support the creation of an equitable and supportive environment seriously and set clear improvement expectations.

3. Value quality over quantity. A clear issue in archaeology, and society more broadly, is the way capitalistic ideas of “productivity” are rewarded. Studies note that work–life balance is an important component of emotional infrastructure in higher education (Aithal and Aithal Reference Aithal and Aithal2023). Yet this is especially difficult to achieve when time becomes a commodity. A trend of valuing quantity over quality is clear in research fields. If standards are continually altered to match the most productive—or most “unburdened” and able to focus solely on work—individuals, those without endless time get left behind regardless of their own success (see also Kawa Reference Kawa2022). This system inevitably privileges those individuals without outside responsibilities, such as caregiving, which continues to disproportionately impact women’s careers (Llorens et al. Reference Llorens, Tzovara, Bellier, Bhaya-Grossman, Bidet-Caulet, Chang and Cross2021). Similarly, in CRM, issues with quantity emerge in the push to survey or excavate as much as possible in a given day to increase the profit of a project, which can lead to health problems or creating workspaces inhospitable for individuals. Instead, we advocate for clearer expectations and a shift to quality over quantity. While quality is admittedly difficult to assess, it is worthwhile for archaeology to attempt to more holistically assess excellence in the discipline. As noted in the institutional-level recommendations, a key component of this would be reconsidering how value is apportioned and compensated to ensure different strengths are recognized and rewarded (see also Hodgetts and Kelvin Reference Hodgetts, Kelvin, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020).

Individual-Level Recommendations

1. Collaborate with individuals beyond your friend network. Homophily, or the tendency to seek out people who are like oneself, is common and impacts career decisions (Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012). The influence of informal friendship networks in archaeology also tends to favor those who “fit” easily into existing dynamics and make others most comfortable socially (Leighton Reference Leighton2020). Individuals can make a conscious effort to combat these tendencies by paying attention to whom they invite as speakers, discussants, members of field crews, members of lab teams, and coauthors on articles, technical reports, or other publications and actively seeking to increase diversity and inclusion. As demonstrated by Bishop and colleagues (Reference Bishop, Kurnick, Fladd, Evans, Garcia and Simeonoff2026) and Oas and colleagues (Reference Oas, Hoppes, Fladd and Kurnick2026), women are already creating more space for women, although we need to continue to question whether this inclusion extends beyond white cisgender women (sensu Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a). Research demonstrates that women also frequently participate in exclusionary practices toward other women, contributing to maintaining whiteness in privileged spaces (e.g., Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011; Simeonoff et al. Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026; Simpson Reference Simpson2004; Smith and Garrett-Scott Reference Smith and Garrett-Scott2021). Actively changing individual practices can begin to change these patterns.

2. Hold yourself accountable for creating a more equitable field. Pay attention to whom you cite in your work and ensure diverse scholars are appropriately represented (see Smith et al. Reference Smith, Williams, Wadud and Pirtle2021). Women are frequently undercited (Hutson Reference Hutson2002, Reference Hutson2006), and this issue is compounded for women of color (Smith and Garrett-Scott Reference Smith and Garrett-Scott2021). The language used by archaeologists can also contribute to the marginalization of certain communities and scholars. As noted by Fong and colleagues (Reference Fong, Ng, Lee, Peterson and Voss2022), discussions of Asian and Asian American women often default to sensationalized language and stereotypical ideas about femininity, which affects both our reconstructions of the archaeological record and the experiences of archaeologists today. Further, Todd (Reference Todd2008) has observed the frequent co-option of Indigenous ideas without credit to Indigenous scholars, and Blakey (Reference Blakey2020:S193) the frequent co-option of Black scholars’ ideas without crediting Black scholars. Expanding whom you read and ensuring appropriate credit are important first steps in the process of creating a more inclusive archaeology. Go a step further and refuse to participate in projects lacking intersectional diversity. Or consider stepping aside if presented with an opportunity that contributes to inequality in the field. Creating space for everyone in the garden will require some to relinquish positions of prestige or share desired resources in favor of inclusiveness, a process we recognize may feel uncomfortable.

3. Ensure that you are recognizing not only the identities of your colleagues but also their expertise and intellectual contributions. Essentialized ideas of gender identity have discouraged women from pursuing certain topics (Horowitz and Brouwer Burg Reference Horowitz and Burg2024). Similarly, remarkably few men in archaeology are involved in work on gender equity in archaeological practice; the conference sessions about gender in archaeological practice (see Figure 1) were almost invariably populated by majority women authors. Even in analyses of the archaeological record, gender is rarely highlighted as a topic (see MacLellan Reference MacLellan2026; Moen Reference Moen2019). While work on gender and identity is important, it is equally important that women be recognized for their research acumen and accomplishments. Specifically, Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a:154–155) notes the assumption that archaeologists of color will study their ancestors, and while many do choose to work with their communities (see Franklin Reference Franklin1997), we should question why white archaeologists do not face the same scrutiny of their research locations and questions.

Women of color, in particular, are often called upon to speak for these identities on panels and at research gatherings, which can lead to a sense of not belonging in archaeology (e.g., Smith and Garrett-Scott Reference Smith and Garrett-Scott2021; Williams Reference Williams2023). Williams (Reference Williams2023) argues that, as a result, women of color are only engaged on their experiential knowledge of race, which in turn limits their visibility in other venues as scholars in their area of expertise. Smith and Garrett-Scott (Reference Smith and Garrett-Scott2021) similarly speak to the reality that Black women are often recognized as service workers rather than scholars, contributing to their intellectual marginalization. While we believe strongly that greater diversity among researchers strengthens our understanding of the past, siloing these researchers into positions to only speak to their identities denies the value added by their contributions to theory-building, lab analyses, and fieldwork methodologies. Greater recognition of the contributions of diverse positionalities to archaeological research itself can also contribute to a greater sense of belonging in the discipline.

4. Call out poor behavior and microaggressions in the moment. Too often, problematic behaviors that may appear minor in the moment are ignored. Frequent interruptions when a colleague is speaking, making problematic comments or jokes, or claiming credit for others’ work may be brushed aside to avoid discomfort. In archaeology, Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024a:Chapter 3) has documented the ways microaggressions wear on women, particularly those also dealing with microaggressions regarding race, disability, or other identities such as immigration status (see also Lawless and Chen Reference Lawless and Chen2015). She advocates for the use of microinterventions—interventions in the moment as a response to a microaggression—by witnesses who can make visible, disarm, educate, or seek support for colleagues (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:65; Sue and Spanierman Reference Sue and Spanierman2020). Similarly, Simeonoff and colleagues (Reference Simeonoff, Matsuda, Perry and Charolla2026) advocate for individuals calling out poor behavior in fieldwork, particularly CRM, and developing reciprocal mentorship relationships outside of formal structures. Unsurprisingly (and disappointingly) research finds that men, owing to their perceived social influence, are able to more effectively point out issues with sexist behavior or gender discrimination (Moser et al. Reference Moser, Watkins and Branscombe2024). However, “unburdened” archaeologists (sensu Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:Chapter 6) often do not perceive discrimination as readily, owing to a lack of awareness of the issues. Individuals of all genders should also be prepared to critically reflect on their own actions when called out for microaggressions concerning gender, race, disability status, or other identities, even when they perceive themselves as allies.

Final Thoughts

Given the systemic nature of discrimination, changes will be necessary at multiple levels to rethink archaeology as a garden meant for everyone. Here, we offer actionable suggestions to start a broader conversation and hopefully effect meaningful change around gender-based and other forms of intertwined inequalities (see also Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:166–167). We encourage readers to reflexively consider their own roles in upholding current systems and bring the relevant recommendations to leadership within their institutions and organizations. Change will require both the rewriting of handbooks and other guidelines and a willingness to act on changing standards to reward inclusivity. Critically, to address sexism and gender discrimination in archaeology, we must be antiracist and confront the settler colonialism inherent within our discipline, which will require “rebuilding internally as well as externally” (Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021:231; see also Acebo et al. Reference Acebo, Campbell, Gonzalez-Tennant, Odewale, Van Alst, White, Mrozowski, Montgomery, Cipolla and Agbe-Davies2025; Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2022; Fong et al. Reference Fong, Ng, Lee, Peterson and Voss2022; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020; Ike et al. Reference Ike, Miller and Hartemann2020). Although aspects of gender equity have improved in archaeology over the past two decades, white women have benefited the most from diversification efforts (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024a:6). We must thus propose interventions that will result in increased equity for all women.

Drawing inspiration from Black (e.g., Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011; Franklin Reference Franklin2001), Indigenous (e.g., Green Reference Green2017; Krawec Reference Krawec2022; Risling Baldy Reference Risling Baldy2018; Supernant et al. Reference Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020), and Posthumanist (e.g., Braidotti Reference Braidotti and Grusin2017, Reference Braidotti2022) Feminisms, as well as queer theory (e.g., Blackmore Reference Blackmore2011; Dowson Reference Dowson2000; Eichner Reference Eichner2025; Moral Reference Moral2016; Rutecki and Blackmore Reference Rutecki and Blackmore2016; Springate Reference Springate, Orser, Zarankin, Funari, Lawrence and Symonds2020; Voss Reference Voss2000), we argue a greater emphasis on care and relationships and their integration into value structures of archaeology would create a more inclusive discipline. Lyons and Supernant (Reference Lyons, Supernant, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020:9) summarize this best when they note, “We envision an archaeology where care is not a liability but a strength.” An important component of this is listening to women in archaeology—women of color, women with disabilities, queer women, immigrant women, et cetera—who are willing to share their experiences through the collection of more high-quality quantitative and qualitative data about the experiences of individuals with intersectional identities (see also Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2002; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024b, Reference Heath-Stout2024a). As advocated by Brodkin and colleagues (Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011:555), anthropology “needs to take seriously the points of view of those who are internal othersFootnote 6 to better understand and diversity itself as well as enhance its theoretical robustness.”

The garden metaphor provides a way to conceptualize necessary shifts and reorientations in our discipline. Not all plants need the same conditions to thrive, and creating systems of support that recognize different needs for water, light, and interactions with other plants will require active alterations not only to our garden features but our very idea of what a garden can and should look like. Institutions and disciplinary societies can act as gardeners, actively encouraging biodiversity while preventing overgrowth of plants that extract resources from others. At the same time, individuals can consider the resources they intake more explicitly and how their actions affect their neighbors. With greater attention to care and active interventions, we believe all people in archaeology could be provided with the support needed to flourish.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the incredible work on gender equality and related topics that has paved the way for this piece. We thank the four generous reviewers whose feedback improved the piece.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All SAA programs from which data for Figure 1a were derived are available at https://www.saa.org/annual-meeting/programs/program-archives. All articles published in American Antiquity used for Figure 1b can be found at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-antiquity.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.