Introduction

The phylum Apicomplexa forms a diverse group of protozoan parasites with several representatives found infecting amphibians and reptiles, such as haemococcidians (Coccidia, Eimeriorina) of the genera Lankesterella, Schellackia and Lainsonia (Desser, Reference Desser1993; Telford, Reference Telford2009). These parasites are characterized as extra-intestinal coccidian parasites that invade the host’s blood cell and which development (merogony, gametogony and sporogony) occurs in the tissues (e.g. liver and intestine) of the same vertebrate host (Desser, Reference Desser1993). Microgamonts produce large numbers of microgametes, and the naked oocysts produce variable numbers of sporozoites (8 in Lainsonia and Schellackia; and 32 or more in Lankesterella), which enter the blood cells (Landau, Reference Landau1973; Desser, Reference Desser1993). These sporozoites are ingested by invertebrate hosts (leeches, mites or mosquitoes) and transmitted to another vertebrate host during blood feeding of the invertebrate host, or by ingestion of the infected vector (Desser, Reference Desser1993). No development is observed in invertebrate hosts (Telford, Reference Telford2009).

Traditionally, haemococcidians have been described as part of the family Lankesterillidae, however molecular studies on 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene sequence have supported the polyphyletic origin of the family, with Lankesterella and Schellackia as distantly related (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2014; Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017). Regarding Lainsonia, despite being considered synonymous with Schellackia based on life cycle characteristics (Levine, Reference Levine1988; Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017), its Neotropical distribution coupled with the lack of available genetic data (Landau, Reference Landau1973; Telford, Reference Telford2009), and the possible restriction of Schellackia to Old World hosts (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017) warrant further investigation into the validity of this genus. In addition, the absence and consistency of morphological diagnostic characteristics to differentiate parasites between genera means that their classification primarily relies on the characteristics of the oocyst during endogenous development (Telford, Reference Telford2009; Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017). These taxonomic uncertainties reflect the lack of knowledge about haemococcidian diversity and phylogenetic relationships, which significantly hinders the accurate classification and understanding of the evolutionary relationships within this group of parasites.

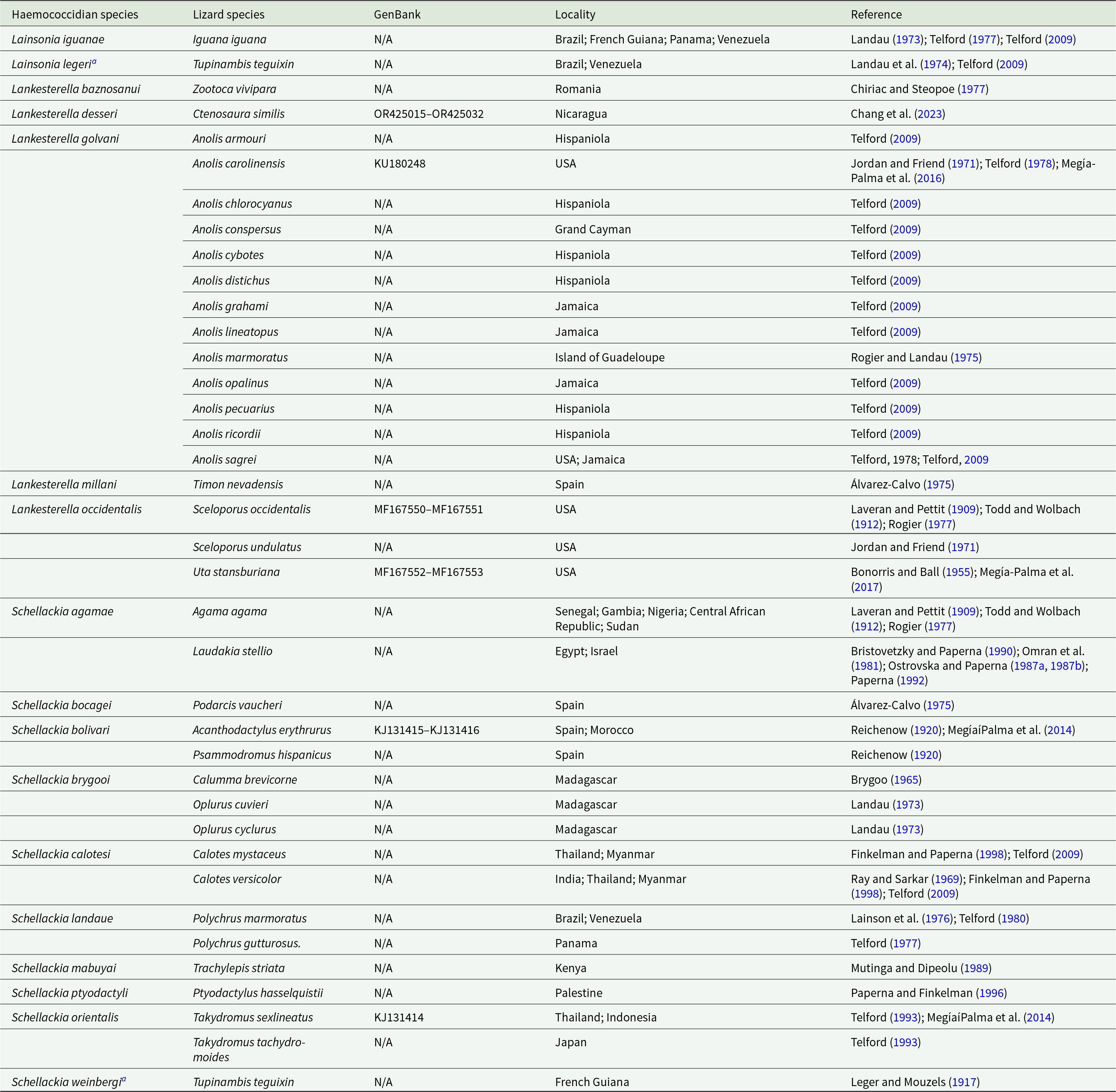

To date, 17 haemococcidian species – 10 Schellackia spp., 5 Lankesterella spp., and 2 Lainsonia spp. – have been described in at least 37 lizard species across 10 families (Agamidae, Anolidae, Chamaeleonidae, Iguanidae, Lacertidae, Phyllodactylidae, Phrynosomatidae, Polychrotidae, Scincidae and Teiidae) in Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe (Table 1). Although more than 30 haemococcidian sequences from reptiles are available in GenBank (Veith et al. Reference Veith, Wende, Matuschewski, Schaer, Müller and Bannert2023; Hajiyan and Javanbakht, Reference Hajiyan and Javanbakht2022), only 4 named species have corresponding 18S rDNA gene sequences (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2014; Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Nasri, Cuervo, Martín, Acevedo, Belliure, Ortega, García-Roa, Selmi and Merino2016, Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023): Lankesterella desseri (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023), Lankesterella golvani (Rogier and Landau, Reference Rogier and Landau1975), Lankesterella occidentalis (Bonorris and Ball, Reference Bonorris and Ball1955) and Schellackia bolivari (Reichenow, Reference Reichenow1920). In the Brazilian Amazon, only 3 species have been described morphologically, all in the 1970s (Landau, Reference Landau1973; Landau et al. Reference Landau, Lainson, Boulard and Shaw1974; Lainson et al. Reference Lainson, Shaw and Ward1976): Schellackia landaue (Lainson et al. Reference Lainson, Shaw and Ward1976); Lainsonia iguanae (Landau, Reference Landau1973) and Lainsonia legeri Landau et al. Reference Landau, Lainson, Boulard and Shaw1974; (Table 1).

Table 1. List of haemococcidian species records in lizards, with GenBank accession numbers (partial 18S rDNA gene sequences available), locality and references

a Lainsonia legeri was considered a synonym of S. weinbergi by Levine (Reference Levine1988).

The green iguana, Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758), is a widespread lizard species in the American continent, ranging from southern North America to central-northern South America and present in some Caribbean islands (Ribeiro-Júnior, Reference Ribeiro-Júnior2015). In Brazil, it is relatively common in the Amazonia, Caatinga and northern Cerrado biomes, often associated with wooded areas close to streams (Ribeiro-Júnior, Reference Ribeiro-Júnior2015). It is primarily arboreal, with diurnal and herbivorous habits (Alberts et al. Reference Alberts, Carter, Hayes and Martins2004). This iguanid lizard has been pointed as the host of some haemoparasite species, such as haemosporidians – Plasmodium basilisci (Peláez and Péres-Reyes, Reference Peláez and Pérez-Reyes1952) reported in El Salvador (Herban and Coatney, Reference Herban and Coatney1969), Plasmodium minasense carinii (Leger and Mouzels, 1917) in Brazil, Colombia, French Guiana and Trinidad (Ayala SC, Reference Ayala1978; Telford, Reference Telford1979), Plasmodium iguanae (Telford, Reference Telford1980) in Venezuela (Telford, Reference Telford1980), Plasmodium rhadinurum (Thompson and Huff, Reference Thompson and Huff1944) in Brazil and Mexico (Thompson and Huff, Reference Thompson and Huff1944; Walliker, Reference Walliker1966; Telford, Reference Telford1977, Reference Telford1980); haemogregarines – Hepatozoon iguanae (Laveran and Nattan-Larrier, Reference Laveran and Nattan-Larrier1912) and Hepatozoon sinimbui (Carini, Reference Carini1942) in Brazil (Laveran and Nattan-Larrier, Reference Laveran and Nattan-Larrier1912; Carini, Reference Carini1942); and haemococcidian – L. iguanae in Brazil (Landau, Reference Landau1973). However, to date, no molecular characterization has been conducted with the haemoparasites of this host.

Thus, by combining microscopy and molecular tools, we investigated the diversity of haemococcidians infecting green iguanas from the Eastern Amazonia, Brazil. This resulted in the description of 1 new species, Lankesterella nucleoflexa sp. nov., and molecular data on another Lankesterella sp. parasite.

Materials and methods

Sampling and microscopy analyses

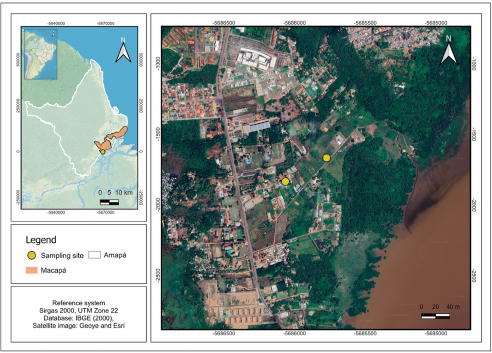

A total of 5 specimens of green iguanas (I. iguana) were manually captured between October 2022 and November 2023 in the metropolitan region of Macapá, State of Amapá, Brazil (Fig. 1). The capture sites included a forest fragment (0°00’53.9” S, 51°04’34.2” W), where 3 specimens were collected, and an urban area (0°00’59.3” S, 51°04’43.6” W), which yielded two specimens. To avoid resampling, individuals were photographed and identified based on sexual dimorphism and unique natural marks, such as scale patterns, scars and colouration. Blood samples were taken via caudal venipuncture (Samour and Hart, Reference Samour and Hart2020) and part was used to prepare blood smears, which were fixed with absolute methanol for 3 min and stained with 10% Giemsa for 30 min (Eisen and Schall, Reference Eisen and Schall2000). The remaining blood was stored in 99.8% absolute ethyl alcohol PA of the Neon brand for molecular purposes. After blood collection, the animals were released in the same environment where they were captured.

Figure 1. Map showing the collection sites (yellow circles) of green iguanas (Iguana iguana) in Macapá municipality, State of Amapá, Eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Sampling points were in forest fragments near urban areas.

The parasitic forms were observed under a Digilab DI-115 T light microscope (Digilab, Brazil) at magnifications of ×400 and ×1000. Images were captured using a digital camera and processed with ImageView® software (BestScope, China), with morphometric data (length, width and area) in micrometers (µm) presented as mean ± standard deviation and range (minimum–maximum). Parasitemia was determined by counting the number of parasites observed in 2000 erythrocytes, divided into 20 fields of 100 erythrocytes (Godfrey et al. Reference Godfrey, Fedynich and Pence1987).

DNA extraction, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Total DNA was extracted from blood samples using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Parasite DNA detection by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) was performed using Hep300 (5’-GTT TCT GAC CTATCA GCT TTC GAC G-3’) and ER (5’-CTT GCG CCT ACT AGG CAT TC-3’) primers, which amplified an ≈1355 base pair (bp) fragment of the 18S rDNA gene (Ujvari et al. Reference Ujvari, Madsen and Olsson2004). The PCR amplifications were carried out in a final volume of 25 μL, containing 2.5 μL of 10 × PCR buffer, 1.5 μL of MgCl₂ (25 mM), 0.5 μL of each dNTP (10 mM), 0.5 μL of each primer (Hep300 and ER, 10 μM), 0.2 μL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL), 2 μL of template DNA, and nuclease-free water to complete the volume. The PCR consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 56 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 40 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Negative (ultrapure water) and positive (DNA of Lankesterella spp. previously amplified) controls were used in every run. To confirm the amplification of the targeted fragment, 2 μL of the final PCR product were run on 1.5% agarose gel. Samples presenting the target DNA size were considered positive. Amplicons were purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System. PCR products were sequenced in both directions with the mentioned primers using the BigDye™ Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

The quality of sequencing and sequences analysis was conducted in Geneious Prime 2023.2.1 (https://www.geneious.com). The obtained sequences were aligned to create a consensus sequence and compared to available sequences in GenBank. All sequences obtained in the present study were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers PX404938 and PX404939).

The sequence database for the Bayesian phylogenetic inference (BI) was constructed using Geneious Prime 2023.2.1 (https://www.geneious.com) and aligned using MAFFT software online v.7 (Katoh et al. Reference Katoh, Rozewicki and Yamada2018). The alignment consisted of 106 sequences up to 1355 bp. The 18S rDNA sequences from Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon were used as an outgroup. The best-fit substitution model SYM + G was selected by MrModelTest2 software version 2.3 (Nylander, Reference Nylander2019). The BI was constructed with MrBayes version 3.2.7 (Ronquist et al. Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012). Each run was conducted with 4 chains and with a sampling frequency of every 100th generation over 3 million generations. We discarded 25% of the trees as ‘burn‐in.’ The remaining trees were used to construct a consensus tree, which was visualized using FigTree v.1.4.0 software (Rambaut, Reference Rambaut2012). Using an alignment of 504 bp, the sequence divergence between all Lankesterella sequences from lizards was calculated with MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Stecher, Li, Knyaz and Tamura2018), using a p-distance model, with uniform substitution rates.

Results

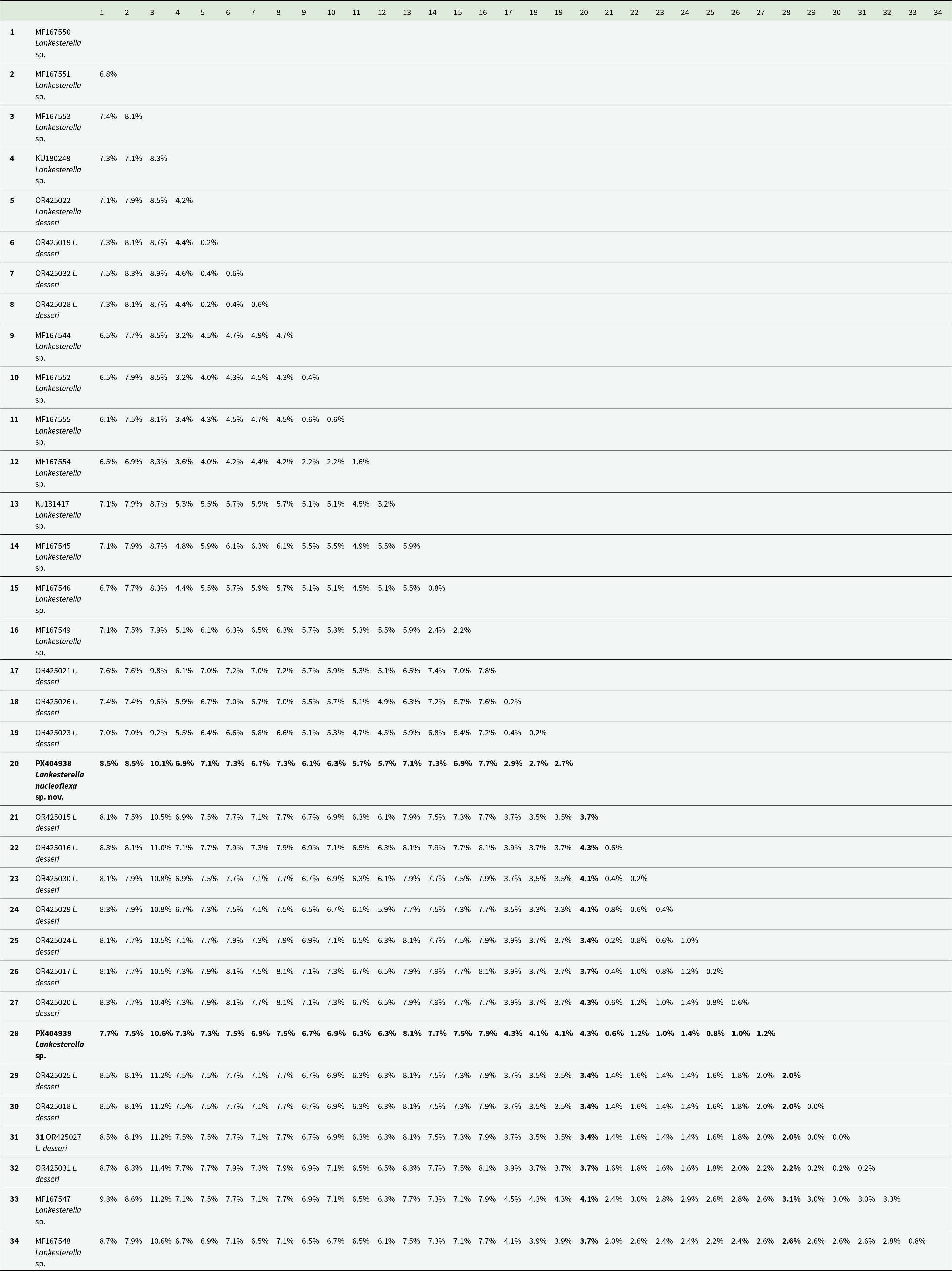

Of the 5 green iguanas tested, 2 were positive for haemococcidian parasites by light microscopy and molecular screening for the 18S rDNA gene. Each infected host harboured a single haemococcidian sequence, with no evidence of mixed infections in the chromatograms. Sequencing results revealed 2 distinct genotypes belonging to the genus Lankesterella: genotype I (GenBank accession number PX404938) and genotype II (GenBank accession number PX404939). The intraspecific divergence (p-distance) between these 2 genotypes was 4.3% (Table 2).

Table 2. Genetic distance matrix (p-distance) based on the 504-bp fragment of the 18S rDNA gene between Lankesterella sequences from lizard hosts. Diagonal cells represent self-comparisons. GenBank accession numbers and corresponding strain IDs are indicated. Sequences include newly obtained sequences from Iguana iguana (Lankesterella nucleoflexa sp. Nov. and Lankesterella sp.) And comparative sequences from GenBank

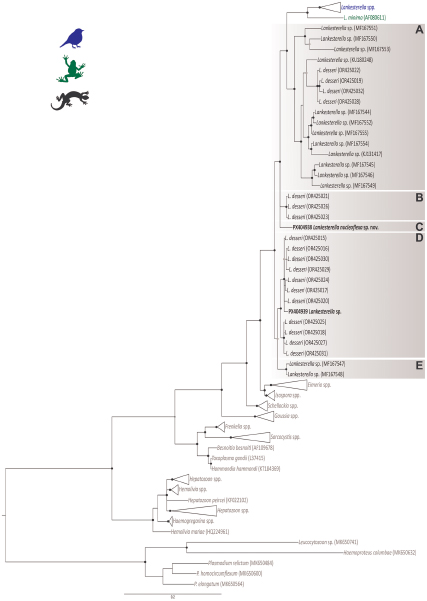

The BI analysis based on the 18S rDNA gene placed the 2 Lankesterella sequences from this study in 2 distinct and well-supported clades (Figure 2). Genotype I (PX404938) was placed in a separate branch closely with L. desseri and other Lankesterella parasites from lizards (Figure 2, Clade C). The genetic distance within this clade ranged from 0.2% (primarily between L. desseri haplotypes) to 10.1% (between our genotype I and Lankesterella sp. MF167553). Genotype II (PX404939) clustered with 7 other haplotypes of L. desseri, which were closely related to 4 additional haplotypes of the same parasite (Figure 2, Clade D). In this clade, the genetic distance varied from 0.2% (mainly between L. desseri haplotypes) to 11% (between L. desseri – OR425016, and Lankesterella sp. – MF167553). Specifically, the genotype II (PX404939) showed a genetic distance ranging from 0.6% to 1.4% with the L. desseri haplotypes in the same clade (Table 2).

Figure 2. Bayesian inference tree of partial 18S rDNA gene sequences (1355bp) of Lankesterella parasites. Haemosporidian parasite DNA sequences (Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon) were used as outgroup. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parenthesis. Lankesterella sequences from lizards are indicated in different shades of brown. Sequences obtained in this study are given in bold. Nodes with posterior probability of <90% are marked with grey dots, and ≥90% are marked with black dots.

Based on an integrative analysis of phylogenetic positioning, molecular data and morphological characteristics, our findings support that the 2 distinct Lankesterella genotypes isolated from I. iguana were classified as 2 separate species, with genotype I formally described herein as the new taxon, L. nucleoflexa sp. nov., and genotype II designated as a Lankesterella sp.

Species description

Phylum Apicomplexa (Levine, 1970)

Class Conoidasida (Levine, Reference Levine1988)

Order Coccidia (Leuckart, 1879)

Suborder Eimeriorina (Léger, 1911)

Family Lankesterellidae (Nöller, 1920)

Genus Lankesterella (Labbé, 1899)

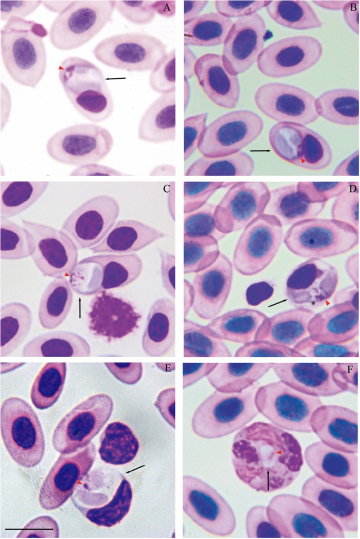

Lankesterella nucleoflexa sp. nov. (Figure 3; Table 3)

Figure 3. Lankesterella nucleoflexa sp. nov. infecting blood cells of Iguana iguana. (A–C) Intraerythrocytic sporozoites folded in spherical body. (D) Intraerythrocytic sporozoite with elongated body. (E) Sporozoite within a mononuclear leucocyte. (F) Sporozoite within a heterophil. Black arrows – parasites; red arrowheads – parasite nucleus; asterisk – refractile body. Thin blood smears stained with Giemsa. Scale bar = 10 μm.

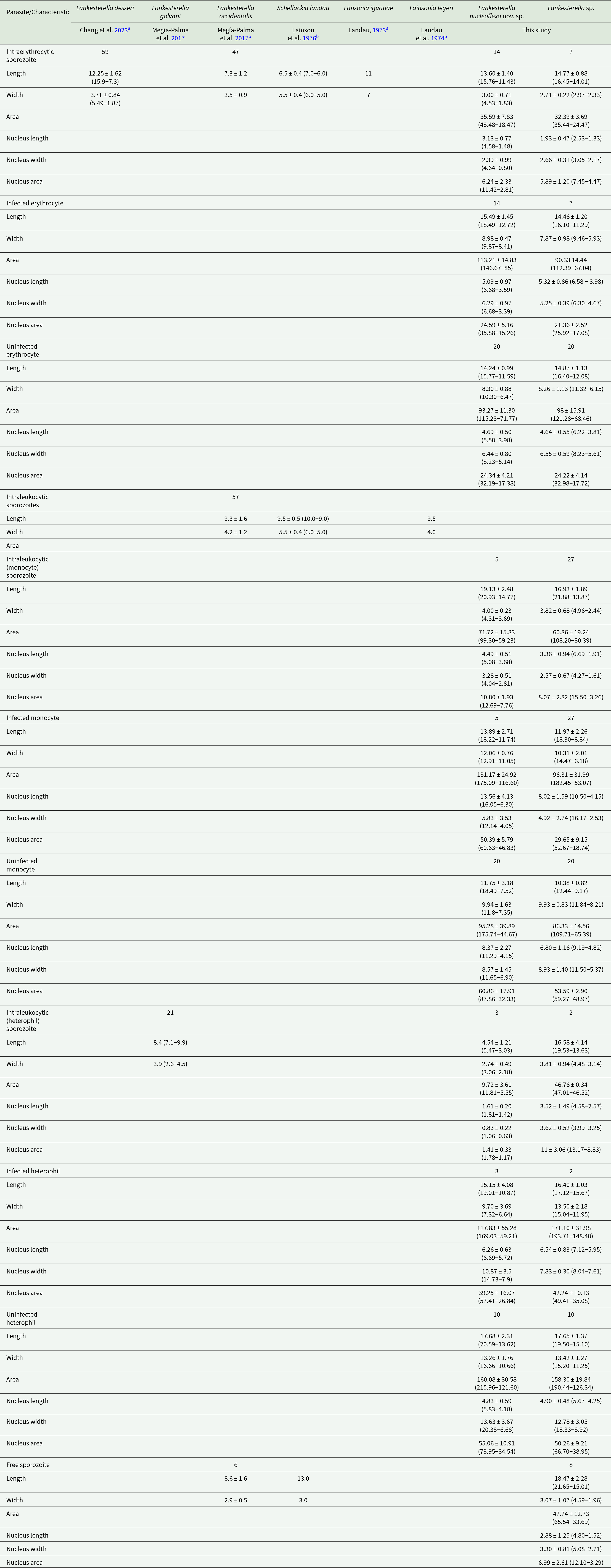

Table 3. Morphometric characteristics of haemococcidian sporozoites detected in green iguana (Iguana iguana) from this study compared with other species described in lizards from the New World. Measurements are in micrometers (µm) and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) followed by the range (maximum and minimum values)

a Authors did not provide morphometric data for sporozoites that infect leucocytes.

b Authors did not morphometrically differentiate sporozoites in different white blood cells; the values were grouped into intraleukocytic sporozoites.

Type host: Green iguana Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758) (Iguanidae)

Other hosts: Unknown.

Type locality: Cerrado forest fragment, Ramal Antena 1, municipality of Macapá, Amapá, Brazil (0°00’53.9” S, 51°04’34.2” W).

Other locality: Unknown.

Site of infection: Blood erythrocytes and leucocytes (mononuclear leucocytes and heterophils).

Prevalence: One individual of Iguana iguana was infected.

Parasitaemia: Parasitaemia was 54 parasites for every 2,000 erythrocytes (2.7%).

Vector: Unknown.

Etymology: The specific epithet ‘nucleoflexa’ is derived from Latin, where ‘nucleo’ refers to the parasite’s nucleus, and ‘flexa’ means ‘flexible’. This name highlights the distinctive characteristic of the parasite’s nucleus.

Type material: hapantotype (1 blood slides) from Iguana iguana were deposited at the Hemoparasite Collection of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Coleção de Hemoparasitos da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – UFMG-HEM) (UFMG-HEM-0055).

DNA sequences: The 18S ribosomal DNA gene sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under accession number (GenBank Accession number PX404938).

ZooBank registration: The Life Science Identifier (LSID) for L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:1B451F2D-CF00-4377-B4DD-9443B796FB80.

Diagnosis: Sporozoites were found mainly in erythrocytes (70.37%; n = 38/54) and less frequently in leucocytes (24.1%; n = 13/54) (mononuclear leucocytes and heterophils). Sporozoites are commonly folded into a large spherical body when infecting erythrocytes and mononuclear leucocyte (Figures 3A–C) and can be rarely seen in their typical elongated form when infecting erythrocytes (Figure 3D). In heterophils, sporozoites exhibit bean-shaped forms and are smaller than those observed in erythrocytes and mononuclear leucocytes (Figure 3F; Table 3). Erythrocytic sporozoites have unequal ends, 1 rounded and the other slightly pointed, while leukocytic parasites present both rounded ends. All sporozoite forms have pale cytoplasm, with a uniform bluish-grey hue. In spherical forms, a colourless cleft is visible between the 2 ends of the sporozoite, and the cytoplasm often exhibits a denser periphery, outlining the parasite. Sporozoite nuclei stain pink and vary in shape and position, from dispersed chromatin filaments (Figure 3D) and condensed masses (Figures 3A and B). Usually, parasite nuclei in erythrocytes appear as condensed masses positioned towards one end. In leucocytes, they are often band-like, centrally positioned and typically occupy the entire width of the host cell. In this case, the band-like structure is observed only in heterophils. In erythrocytes, sporozoites are in a polar position, displacing the host cell nucleus to the cell margin (Figures 3A–D). Sporozoites infecting mononuclear leucocytes are larger than erythrocytic forms (Table 3), occupying the entire cytoplasm of the host cell, and deforming their nuclei (Figure 3D). In heterophils, sporozoites are in the central region of the host cell and do not produce any visible effect in the host cells or their nuclei (Figure 3F; Table 3). Free sporozoites were not observed. A single refractile body is variably present in elongated forms and is inconspicuous in spherical and bean-shaped parasites. The refractile body has a small, round shape and, when present, is usually located close to the parasite’s nucleus (Figure 3D).

Effects on the host cell: In erythrocytes and mononuclear leucocyte, sporozoites produce visible effects. Parasitized erythrocytes became slightly hypertrophied and sometimes distorted, with their nuclei distorted and displaced towards one of the extremities of the host cell (Figure 3E; Table 3). Infected mononuclear leucocytes were also hypertrophied with their nuclei strongly deformed and pushed to one of the margins of the host cell (Figure 3D; Table 3). No deformation was seen in infected heterophils.

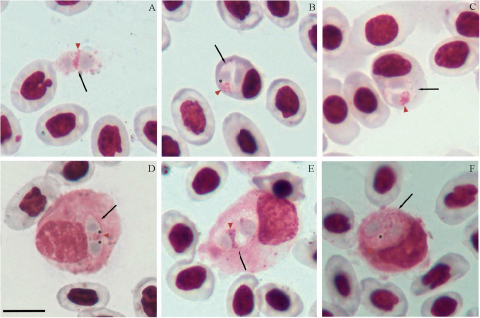

Remarks: Landau (Reference Landau1973) morphologically described L. iguanae in hosts captured in Brazil (states of Pará and Pernambuco) and French Guiana (Cayenne), thus being the first haemococcidian described infecting this host (Figure 4). Later, this parasite species was also found by Telford (Reference Telford1977) in the same host from Panama and Venezuela, but the author did not provide morphological data for the parasite found. In the original description, Landau (Reference Landau1973) stated that similar sporozoites were observed in erythrocytes and monocytes of hosts from the 3 localities (Pará, Pernambuco and Cayenne). However, the characterization of the species and its development in the experimental vector (Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762) was based on the parasites found in a single host collected in Belém, state of Pará, Brazil. Furthermore, the description provided for the sporozoites of L. iguanae in the peripheral blood was quite vague. This limits the comparison with L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. because, beyond the unknown intraspecific morphological variation in L. iguanae that could include forms similar to L. nucleoflexa sp. nov., it is impossible to determine if the other hosts in the other localities harboured L. iguanae or another haemococcidian species. Still, we consider it important to compare the 2 species, since there is no published data for the L. iguanae leukocytic forms, we will be limited to the erythrocytic sporozoites. Sporozoites of L. iguanae differs from L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. by being smaller (Table 3), having both ends rounded, and a triangular nucleus positioned between 2 refractile bodies (Figure 4). Compared to other described species of lizards from the New World, L. legeri, S. landauae, L. golvani, L. occidentalis and L. desseri, the sporozoites of L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. are morphologically different (Table 2). Sporozoites of L. legeri only infect monocytes and lymphocytes; despite being surrounded by a clear space not limited by a membrane inside the host cell, they are always elongated instead of folded like L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. Additionally, they exhibit a smaller length than L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. and possess a transverse or triangular nucleus (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Lainson, Boulard and Shaw1974; Table 2). For S. landauae, sporozoite morphology varies depending on the host cell, which can be leucocytes (monocytes or lymphocytes) and erythrocytes. Within leucocytes assume a stumpy bean or sausage shape and possess a smaller length and bigger width than L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. (Lainson et al. Reference Lainson, Shaw and Ward1976; Table 2). In erythrocytes, they are folded up into a tight oval body with smaller dimensions than L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. (Lainson et al. Reference Lainson, Shaw and Ward1976; Table 2). The sporozoites described for L. golvani and L. occidentalis are elongated and do not exhibit a spherical, folded shape, unlike those of L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. (Bonorris and Ball, Reference Bonorris and Ball1955; Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017; Table 2). Furthermore, L. golvani exclusively infects leucocytes (monocytes, lymphocytes and primarily heterophils) without deforming the host cells (Telford, Reference Telford2009). For L. desseri, sporozoites varied in shape, ranging from bent to lentiform, and most frequently fusiform, displaying eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm, and slightly displacing or distorting both the host cell and its nuclei (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023).

Figure 4. Lainsonia iguanae in green iguana (Iguana iguana) from Para, Brazil, voucher material (no. 15 HA) from Landau’s collection, MNHN. (A) Free sporozoite. (B-C) Intraerythrocytic sporozoite. (D–F) Sporozoites within leucocytes. Black arrows – parasites; red arrowheads – parasite nucleus; asterisk – refractile body. Thin blood smears stained with Giemsa. Scale bar = 10 μm.

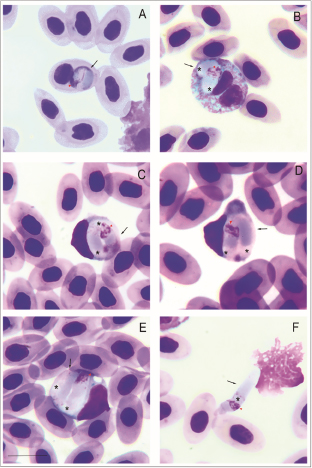

Lankesterella sp. (PX404939; UFMG-HEM-0056; Figure 5; Table 3)

Figure 5. Lankesterella sp. infecting blood cells of Iguana iguana. (A) Intraerythrocytic sporozoite. (B) Small sporozoite in a heterophil. (C–D) Large sporozoites in mononuclear leucocytes. (F) Free sporozoite. Black arrows – parasites; red arrowheads – parasite nucleus; asterisks – refractile bodies. Thin blood smears stained with Giemsa. Scale bar = 10 μm.

This haemococcidian parasite is characterized by sporozoites infecting mainly in mononuclear leucocyte (59.6%; n = 42/70), and less frequently in erythrocytes (12.8%; n = 9/70) and heterophils (2.8%; n = 2/70) of I. iguana in Brazil (0°00’59.3” S, 51°04’43.6” W).

Within host cells, sporozoites are typically curved, occasionally with rounded ends (Figure 5A), with rounded ends. The cytoplasm stains bluish-grey and has a heterogeneous appearance, usually showing reddish-staining granules (Figure 5C). Eventually, a colourless slit of variable size is visible between its ends (Figures 5C and 3D). The nuclei of the parasites are large, with irregularly shaped chromatin, and located centrally or towards one of the ends (Figures 5A and 5B). Sporozoites infecting mononuclear leucocytes are large and wide, occupying the entire host cell cytoplasm, which severely distorts the host cell and its nucleus (Figure 5D; Table 2). The parasite is closely appressed to the host cell nucleus pushing it towards the opposite pole and markedly deforming the host cell nucleus when infecting mononuclear leucocytes Free sporozoites were common (Figure 5F; Table 3), exhibiting slender and elongated bodies, with one pointed end and the opposite rounded. Sporozoites possess 1 or 2 spherical refractile bodies located in variable positions. The presence of the refractile bodies is constant in free forms and sporozoites within host cells. Sporozoites produce visible effects in erythrocytes and mononuclear leucocyte (Figures 5B–D; Table 3). Parasitized mononuclear leucocyte exhibits the most pronounced changes, with marked hypertrophy and nuclear deformations. Erythrocytes show increased volume and distortions, with their nuclei pushed toward the cell margin.

Remarks: This parasite clusters within a clade of L. desseri (Clade D; Figure 2), described by Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023), with minimal intergenotypic divergence. While this phylogenetic position suggests it may represent the same species, the observed polyphyletic position of the sequences named as L. desseri (Clades A, B and D; Figure 2), along with the lack of detailed morphological data from its previous descriptions (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023), precludes a definitive comparison with the Lankesterella sp. from our study and its formal description as a new species. Further morphological data (e.g. on merogony, gamogony and sporogony) and additional molecular markers (e.g. mitochondrial gene amplification) are necessary to resolve this taxonomic conflict. Despite these uncertainties, it is valuable to compare its morphology to that of L. nucleoflexa sp. nov., also described in this study. Although both parasites have similar sporozoite shapes and infect the same type of host cells, they can be clearly distinguished. The sporozoites of L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. are typically spherical with a light cytoplasm, while those of the Lankesterella sp. genotype II are large and elongated, with a heterogeneous and granular cytoplasm (Figures 3 and 4; Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to employ an integrative approach, by combining phylogenetic analyses based on the 18S rDNA gene and morphological data, to characterize haemococcidians infecting I. iguana, and as a result, we described L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. Furthermore, by presenting a complete and updated checklist of haemococcidian species from lizards, we highlight the existence of a significant gap in Lankesterella research in these hosts, particularly in terms of molecular characterization, which is likely among the most neglected within the phylum Apicomplexa, with over 40 years since the last species description in Brazil (see Table 1).

Previously, only one haemococcidian species had been described in green iguanas, L. iguanae, which Landau identified in 1973 through the morphology of the blood and tissue stages. Despite some erythrocytic forms observed in L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. and exhibiting characteristics that could be somewhat similar to L. iguanae (e.g. a spherical shape), other morphological and morphometric characteristics of the sporozoites reveal significant divergences from the species described by Landau, indicating that, L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. is distinct from L. iguanae (see remarks). Unfortunately, our study did not target other developmental stages (e.g. tissue stages) of Lankesterella, preventing a detailed comparison with this species.

By definition, Lainsonia differs from other haemococcidian genera by having merogony, gamogony and sporogony in the reticuloendothelial system, and sporozoites parasitizing erythrocytes or leucocytes (Landau, Reference Landau1973; Landau et al. Reference Landau, Lainson, Boulard and Shaw1974; Lainson et al. Reference Lainson, Shaw and Ward1976). However, these characteristics may not be sufficient to distinguish this genus, as some authors have, over the years, synonymized Lainsonia with Schellackia; both produce 8 sporozoites per oocyst, whereas Lankesterella oocysts produce 32 or more sporozoites (Levine, Reference Levine1988; Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017). Although the parasites we found were morphologically similar to Lainsonia, their sequences grouped with other lineages from the genus Lankesterella. This finding is particularly interesting because it indicates that Lainsonia may be a synonym of Lankesterella, thus refuting its synonymy with Schellackia. Additionally, our data support the hypothesis that the genus Lankesterella in lizard hosts has a distribution restricted to the New World (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017). To resolve the persistent taxonomic conflict surrounding the genus Lainsonia, more comprehensive morphological and molecular data are needed. Our findings highlight that the developmental characteristics previously used to classify haemococcidian genera, along with the overall systematics of the group, require a thorough review (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2014).

Other records of haemococcidians in I. iguana are scarce and generally not formally described. Telford (Reference Telford1977) mentioned a low prevalence of L. iguanae in green iguanas from Venezuela (n = 2/69) and Panama (n = 2/29), though without further descriptive detail. Similarly, morphotypes suggestive of haemococcidians were observed in captive iguanas in the USA (Harr et al., Reference Harr, Alleman, Dennis, Maxwell, Lock, Bennett and Jacobson2001). In Brazil, the most recent report was made by Lima et al. (Reference Lima, Castro, Pedroso, Meneses and Giese2020) in green iguanas from Santarém, Pará state, where intraerythrocytic sporozoites were consistent with the genus Lainsonia, but without morphological descriptions or molecular support. Thus, this study significantly expands the knowledge of the geographic distribution of these parasites in Brazil, including new records in Eastern Amazonia, and provides the first molecular data associated with haemococcidians in green iguanas.

It is important to mention that our literature survey on the haemoparasite species of I. iguana uncovered descriptions of haemogregarines, specifically H. iguanae and H. sinimbui (Laveran and Nattan-Larrier, Reference Laveran and Nattan-Larrier1912; Carini, Reference Carini1942). Their morphological characteristics bear a striking resemblance to haemococcidians previously described in these hosts (Landau, Reference Landau1973; this study). Hepatozoon iguanae, whose type locality was addressing as South America, was observed infecting both erythrocytes and leucocytes and exhibited 3 distinct morphologies. These included small, often curved forms (5–6 × 1–2 μm) with one rounded and one tapered end, surrounded by a clear space. Larger parasites were noted, folded into spherical shapes (8–10 × 1–40 μm) with rounded or slightly tapered ends. Additionally, free forms were elongated (9–15 × 1 µm) and slightly curved, with rounded or sometimes tapered ends (Laveran and Nattan-Larrier, Reference Laveran and Nattan-Larrier1912). In contrast, H. sinimbui, discovered in hosts from Porto Nacional, Tocantins state and Brazil, was exclusively found in erythrocytes. This species was characterized by small, rounded forms (6–8 μm diameter) with a distinct line separating the 2 ends of the parasite internally, alongside free parasites that were elongated or banana-shaped (14 × 5 µm) (Carini, Reference Carini1942). While neither description explicitly mentions the presence of refractile bodies or vacuoles, the available plates clearly illustrate that their cytoplasm was granular. Notably, in H. sinimbui, there was a distinct, clearer and rounder space near the parasite’s nucleus, which closely resembles refractile bodies (Carini, Reference Carini1942). We acknowledge the possibility that these parasites are indeed haemogregarines, especially given that some Hepatozoon species infect reptile leucocytes (Morais et al. Reference Morais, Rodrigues, Diniz, Úngari, O’Dwyer, de Souza, DaMatta and Silva2024). However, based on their unique morphology, we hypothesize they may in fact be haemococcidians.

From an ecological perspective, the hypothesis that these parasites are haemococcidians becomes quite plausible. Iguana iguana is an herbivorous species (Alberts et al. Reference Alberts, Carter, Hayes and Martins2004), which makes their parasites inclusion among haemogregarines unlikely, as the latter’s life cycle typically involves the predation of infected paratenic vertebrate hosts (Smith, Reference Smith1996) – a dietary habit not characteristic of green iguanas. In contrast, passive transmission through ingestion or bites from invertebrates, such as mites and mosquitoes, aligns well with the ecology of green iguanas and known life cycle of haemococcidians (Landau, Reference Landau1973; Desser, Reference Desser1993). Notably, Laveran and Nattan-Larrier (Reference Laveran and Nattan-Larrier1912) reported an abundant presence of mites (Amblyomma dissimile Koch, 1844) on the examined hosts, further bolstering the haemococcidian hypothesis. Furthermore, the wide geographical distribution and high population densities of iguanids favour the persistence and diversification of haemococcidian lineages across different ecological regions (Campos and Desbiez, Reference Campos and Desbiez2013; Maurer et al. Reference Maurer, Burton, Mcclave, Kinsella, Wade, Cooley and Calle2020). This explains the observation of multiple morphotypes, even within single samplings, which is consistent with the high genetic diversity seen in haemococcidians (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017). While definitive identification without molecular data remains challenging, the combined morphological, ecological and comparative evidence strongly suggests that the species described by Laveran and Nattan-Larrier (Reference Laveran and Nattan-Larrier1912) and Carini (Reference Carini1942) belong to the Lainsonia–Lankesterella complex.

The life cycle of the 2 Lankesterella species described in this study remains unknown. Landau (Reference Landau1973) experimentally described the life cycle of L. iguanae in I. iguana following infection of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. These vectors developed infections in stomach epithelial cells, but subsequent transmission to other lizard species was unsuccessful, suggesting vertebrate host specificity. Other studies also indicate that mosquitoes of the genus Culex and sandflies can act as vectors for different haemococcidians in lizards, promoting oocyst development and the release of infective sporozoites (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Lainson, Boulard and Shaw1974; Lainson et al. Reference Lainson, Shaw and Ward1976; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Young, Greiner, Telford and Butler1988). Furthermore, other invertebrates, such as mites, may play a role in Lankesterella transmission (Bonorris and Ball, Reference Bonorris and Ball1955; Jordan and Friend, Reference Jordan and Friend1971), though this still needs more experimental confirmation (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017).

Recent studies suggest high genetic diversity within Lankesterella, particularly in Neotropical reptiles (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017; Er-Rguibi et al., Reference Er-Rguibi, Harris and Aglagane2023; Hajiyan and Javanbakht, Reference Hajiyan and Javanbakht2022). This pattern is corroborated by our results, in which a relatively small number of hosts sampled in a limited area yielded 2 distinct genotypes of haemococcidians. In fact, L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. and Lankesterella sp. exhibit a genetic distance of 4.1%, which, combined with their distinct phylogenetic positions and morphological traits, reinforces their separation as valid and independent species.

Our phylogenetic analyses, based on the 18S rDNA region, recover patterns consistent with previous haemococcidian phylogenies (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2014; Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017). These analyses reinforce the polyphyly of the family Lankesterillidae and the separation of Lankesterella clades among lineages obtained from birds, anurans and lizards (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2014; Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Nasri, Cuervo, Martín, Acevedo, Belliure, Ortega, García-Roa, Selmi and Merino2016, Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017; Chagas et al. Reference Chagas, Harl, Preikša, Bukauskaitė, Ilgūnas, Weissenböck and Valkiūnas2021; Veith et al. Reference Veith, Wende, Matuschewski, Schaer, Müller and Bannert2023).

The 2 novel Lankesterella genotypes isolated from I. iguana show distinct phylogenetic positions and molecular divergences. Genotype I, described here as L nucleoflexa sp. nov., occupies an isolated branch, consistent with interspecific differentiation. This lineage is clearly separated from all others, including the clades A, B and D that contain sequences of L. desseri (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023), with divergence values ranging from 2.7% to 8.5%. This strong divergence supports its recognition as a new species. In contrast, the genotype II, identified here as a Lankesterella sp., clustered within clade D, which comprises 7 other sequences identified as L. desseri (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023).

These findings address the polytomy observed in L. desseri and supports the hypothesis that it is a polyphyletic taxon, comprising multiple genetically distinct species-level lineages that lack a single common ancestor (see Figure 2; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023). While the internal divergence within the clade D is low (0.6–1.4%), a range compatible with intraspecific variation, the divergence between D and the other L. desseri clades A and B exceeds 6%. This high divergence is well above commonly applied thresholds for species delimitation in Apicomplexa using the 18S rDNA marker (Megía-Palma et al. Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2014; Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Nasri, Cuervo, Martín, Acevedo, Belliure, Ortega, García-Roa, Selmi and Merino2016, Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez, Paranjpe, D’Amico, Aguilar, Palacios, Cooper, Ferri-Yáñez, Sinervo and Merino2017) and is consistent with the high intergenotypic divergence (up to 8%) found by Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Lin, Huang, Lee, Shih, Wu, Huang and Chen2023).

This combination of low intra-clade and high inter-clade divergence confirms that the subclades currently grouped under L. desseri likely represent multiple, distinct species. Therefore, while our study formally describes L. nucleoflexa sp. nov., we refrain from formally describing Lankesterella sp. as a new species, until a comprehensive taxonomic revision of the L. desseri complex is conducted. This revision will require expanded geographic sampling, detailed morphological data and higher-resolution molecular markers, such as mitochondrial genes.

The description of L. nucleoflexa sp. nov. expands our knowledge regarding the diversity of haemococcidians in Neotropical reptiles, particularly in iguanas from the Eastern Amazonia region, representing the first study with molecular characterization of haemococcidians in lizards from Brazil. Future studies should address the life cycle of these species, with vector incrimination and endogenous development in the tissues of the green iguana. Here, we also highlight the importance of integrative approaches, careful morphological comparisons and molecular analyses for the precise taxonomic delimitation of parasites with conserved morphology. These findings open new perspectives for more specific investigation with haemococcidians, highlighting the relevance of systematic studies in tropical regions that are still poorly explored.

Data availability statement

Sequence data are available at GenBank accessions: PX404938 and PX404939 (partial 18S rDNA). Haemococcidan hapantotype and voucher specimens are deposited at the Coleção de Hemoparasitos da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG-HEM-0055 and UFMG-HEM-0056).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Postgraduate Development Program (PDPG – Sucupira Platform/CAPES – Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel); the Laboratory of Morphophysiological and Parasitic Studies (Laboratório de Estudos Morfofisiológicos e Parasitários LEMP/UNIFAP) for allowing the use of equipment for microscopic analyses. We are also grateful to Dr Coralie Martin and Dr Irène Landau of the MNHN, Paris, France, for kindly providing the voucher smear of L. iguanae used in this study.

Author contributions

D.P.A., A.M.P. and L.A.V. conceived and designed the study. D.P.A., and L.A.V. conducted fieldwork. D.P.A. performed the microscopic analysis. C.R.F.C. molecular analysis. D.P.A., A.M.P. and C.R.F.C. processed the data, interpreted the results, and worked on the manuscript. L.A.V. was responsible for funding acquisition and supervision. All authors took part in the preparation, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research was funded by the Emergency Postgraduate Development Program (PDPG) for Strategic Consolidation of Academic Stricto Sensu Postgraduate Programs and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Brazil (CAPES) (88887.847774/2023-00). We are grateful to the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq PROTAX 433909/2024-5) for postdoctoral fellowship to A.M.P.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures involving animals in the present study were approved by the animal use ethics committee of the Federal University of Amapá (protocol number 01/2025), and lizard sampling and access to genetic data were authorized by the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment (numbers SISBIO 91583 and SISGEN ADECE59, respectively).