Introduction

Ticks are medically important arthropods that parasitize the skin surfaces of mammals, reptiles, birds and other animals. They act as vectors for a wide range of pathogenic bacteria, viruses and protozoa, transmitting numerous diseases to humans and animals. Ticks impose substantial economic losses on the global livestock industry. Currently, over 28 tick species are known to transmit a diverse array of tick-borne diseases, including Lyme disease, spotted fever rickettsiosis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and Q fever (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Niu, Liu, Yang, Chen, Guan, Liu, Luo and Yin2016; Madison-Antenucci et al. Reference Madison-Antenucci, Kramer, Gebhardt and Kauffman2020; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang, Fan, Ji, Liu, Zhang, Li, Zhou, Li, Liang, Liu, Yang and Fang2021).

Spotted fever rickettsiosis comprises a group of zoonotic diseases caused by Rickettsia species. The genus Rickettsia is categorized into two primary groups: the typhus group (TG) and spotted fever group (SFG). SFG rickettsiae encompass numerous pathogenic species capable of causing illnesses ranging from mild to severe and life-threatening, posing a significant global public health threat (Azad Reference Azad1990; Raoult and Parola Reference Raoult and Parola2007; Bechah et al. Reference Bechah, Capo, Mege and Raoult2008; Parola et al. Reference Parola, Paddock, Socolovschi, Labruna, Mediannikov, Kernif, Abdad, Stenos, Bitam, Fournier and Raoult2013; Liu et al. Reference Liu, He, Huang, Wei and Zhu2014; Fang et al. Reference Fang, Liu, XL, Liang, Yang, Yao, Rx, Sun, Chen, Zuo, Ma, Li, Jiang, Liu, Yang, Gray, Krause and WC2015; Gong et al. Reference Gong, He, Wang, Shang, Wei, Liu and Tu2015). Recent studies have highlighted the importance of wildlife as reservoirs for tick-borne pathogens in urban environments, such as urban wild boars in Barcelona, which have been found to carry zoonotic tick-borne pathogens like Rickettsia and Francisella species (Carrera-Faja et al. Reference Carrera-Faja, Ghadamnan, Sarmiento, Cabrera-Gumbau, Jasso, Estruch, Borràs, Martínez-Urtaza, Espunyes and Cabezón2025). Similarly, European hedgehogs in urban areas have shown high prevalence of vector-borne pathogens, including Borrelia and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, emphasizing their role as potential amplifiers of these pathogens in human-populated regions (Springer et al. Reference Springer, Schütte, Brandes, Reuschel, Fehr, Dobler, Margos, Fingerle, Sprong and Strube2024).

Lyme disease, a serious zoonosis, results from infection with bacteria of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, which exhibits extensive genetic diversity and widespread prevalence across China (Hao et al. Reference Hao, Hou, Geng and Wan2011). Human granulocytic anaplasmosis in China is primarily caused by tick-borne bacteria of the genus Anaplasma, commonly transmitted to livestock. Species including Anaplasma bovis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Anaplasma ovis have been identified in yaks, sheep and goats in China (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Li, Liu, Liu, Niu, Ren, Chen, Guan, Luo and Yin2015, Reference Yang, Liu, Niu, Liu, Guan, Xie, Luo, Wang, Wang and Yin2016a). A large-scale study in Yunnan Province further revealed high genetic diversity and prevalence of emerging Rickettsiales, including multiple pathogenic species, underscoring the need for surveillance in biodiversity hotspots (Du et al. Reference Du, Xiang, Bie, Yang, JH, Yao, Zhang, He, Shao, Luo, Pu, Li, Wang, Luo, Du, Zhao, Li, Cao, Sun and Jiang2024). Q fever, caused by the widely distributed zoonotic pathogen Coxiella burnetii, has been linked to abortion in cattle. Furthermore, infection rates increase with cattle age (El-Mahallawy et al. Reference El-Mahallawy, Lu, Kelly, Xu, Li, Fan and Wang2014).

The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, characterized by a cold climate and rich biodiversity, is the largest plateau region in the world. Qinghai Province of China is located on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and harbours a large population of yaks, serving as a major production area for Chinese yaks (Bos grunniens). The yak population in Qinghai accounts for approximately 40% of the total national population; they are not only a unique livestock resource that local herders depend on for their livelihoods but also a crucial source of stable income for the regional animal husbandry industry. However, previous studies on tick-borne pathogens have mostly focused on the central and eastern regions of China or single host species, and the molecular characteristics and epidemic patterns of SFG rickettsiae in the yak population on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau remain unclear. Although some studies have reported the presence of rickettsial infections in yaks in Qinghai (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Liu, Niu, Liu, Guan, Xie, Luo, Wang, Wang and Yin2016a; Jian et al. Reference Jian, Li, Adjou Moumouni, Zhang, Tumwebaze, Wang, Cai, Li, Wang, Liu, Li, Ma and Xuan2020; Li et al. Reference Li, Jian, Jia, Galon, Benedicto, Wang, Cai, Liu, Li, Ji, Tumwebaze, Ma and Xuan2020a; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Ai, Kang, Li and Sun2023, Reference Ma, Jian, Wang, Zafar, Li, Wang, Hu, Yokoyama, Ma and Xuan2024), these studies neither systematically screened for other tick-borne pathogens (e.g. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Coxiella burnetii) nor analysed the effects of gender and age on infection rates.

In this study, for the first time, we targeted yaks in the Xining area and employed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology to screen for 7 common tick-borne pathogens. The study identified the high prevalence characteristics and influencing factors of R. raoultii, supplemented the basic data on tick-borne diseases in the unique livestock of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and provided a scientific basis for the integrated prevention and control of such diseases in the ‘human–animal–environment’ system.

Methods

Sample collection

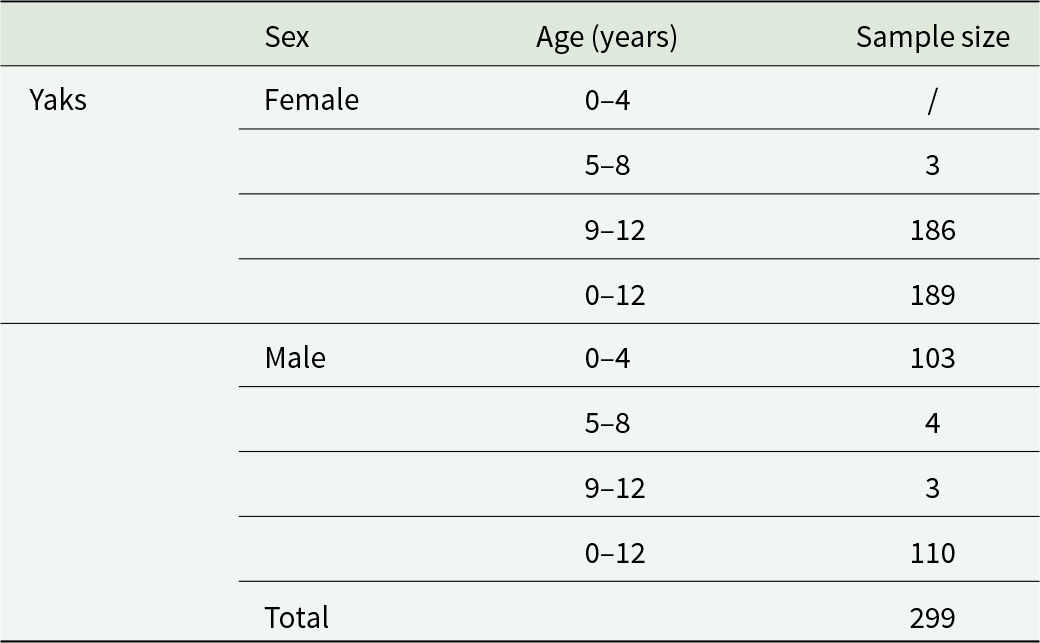

A total of 299 blood samples were collected from grazing yaks in Xining City from the Qinghai Province, in the eastern part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China, at an average elevation of more than 3000 meters. Table 1 showed the sex and age information of current yaks in Xining City.

Table 1. Sex and age distribution of yak samples from Xining

/: no analysis.

The sample size was estimated based on previous studies on the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in yaks on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (estimated prevalence: 30%). Using the formula: n = Z2 × P × (1 − P)/d2 (where Z = 1·96, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval; d = 0·05, margin of error), the minimum required sample size was calculated as 323. Considering potential sample loss during actual sampling (e.g. blood coagulation and failed DNA extraction), a total of 299 samples were finally collected. Verification confirmed that this sample size meets the requirements for statistical tests.

All procedures were carried out according to the ethical guidelines of Qinghai University (permission number: PJ2024-02-131).

DNA extraction

Blood samples were collected from 299 yaks and stored in tubes containing anticoagulant (EDTA) for genomic DNA extraction. The QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) was used for DNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and the DNA was stored at −80 °C until further use.

PCR reaction

In order to ascertain whether the yaks sampled were infected with tick-borne diseases, appropriate genes and primers were selected for testing. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. These include the PCR assay based on the outer membrane protein A (ompA) gene, which was used to identify rickettsiae in the blood of yaks on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. To confirm the presence of SFG rickettsiae, all samples that tested positive for the ompA gene were subjected to further testing for the citrate synthase gene (gltA).

All yak DNA samples were screened by PCR or nested PCR and amplified using specific primers. The PCR test volume was 25 µL, including 3 µL DNA or the product of the first PCR reaction, 1 µL each forward and reverse primer (10 µM), 0·4 µL deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (200 µM, New England BioLab, USA) and 2 µL 10 × ThermoPol reaction buffer (New England BioLab, USA). Add 1 µL Taq polymerase (0·5 U, New England BioLab, USA) and sufficient double-distilled water to give a final volume of 25 µL. Positive animal DNA samples from a previous study were used as positive controls, while double distilled water was used as a negative control.

Sequence analysis

To confirm the pathogens detected, at least one positive sample per sample was selected for sequencing and molecular characterisation. PCR products from positive samples were purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Purified PCR products were cloned into E. coli DH5α using the PMDTM 19-T Vector Cloning Kit (Takara, Japan). The positive clones were sequenced by Genewiz (Suzhou, China). The sequences obtained were confirmed in GenBank by BLASTn search.

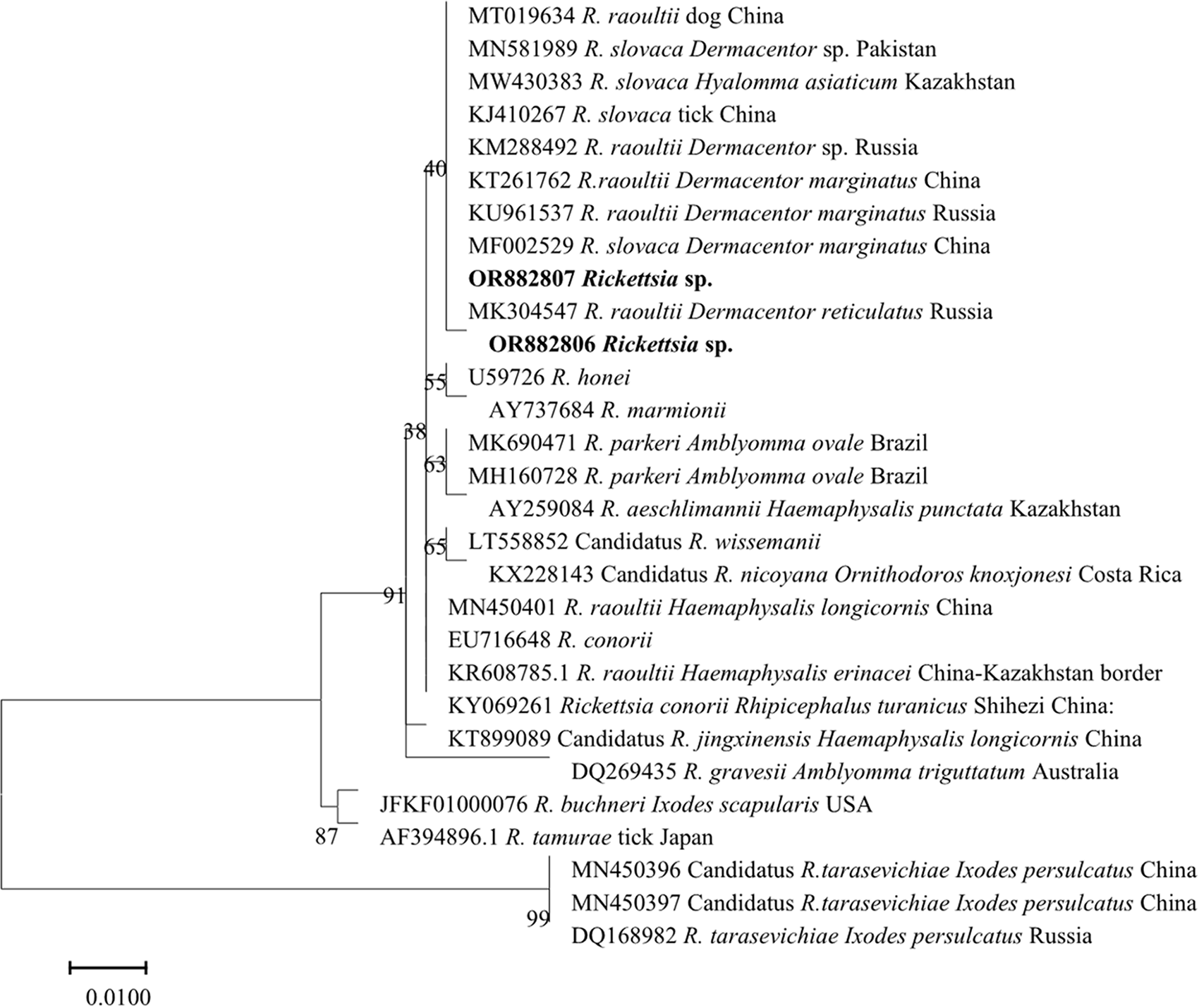

Phylogenetic analyses

Using MEGA 7·0 software, the optimal fitting models were selected using ModelTest – K2 + G model for the ompA gene and T92 model for the gltA gene. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed, with 1000 bootstrap replicates to evaluate the reliability of node branching (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016).

Statistical analysis

A chi-square test was conducted using Graph prism 8 software to assess the proportion of positive samples detected between age and sex groups. Observed differences were considered statistically significant if the resulting P-value was less than 0·05.

Results

Using PCR with specific primers targeting the aforementioned pathogen genes, we tested 299 yak blood samples. Results indicated that SFG rickettsiae were detected exclusively in samples from Xining City. Other targeted pathogens, including B. burgdorferi sensu lato, A. phagocytophilum, C. burnetii and Theileria sp., were not detected.

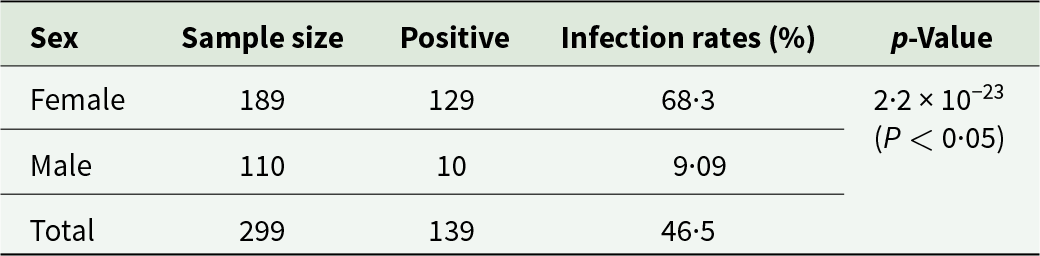

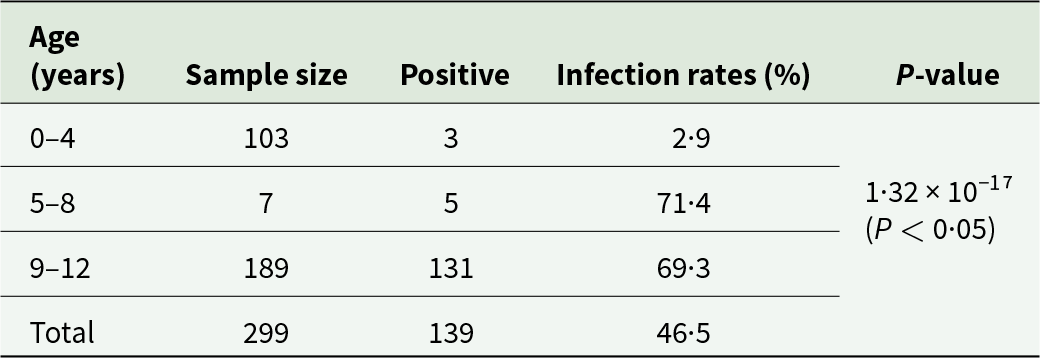

In this study, the 139 of 299 yak blood samples (46·5%) from Xining City tested positive for R. raoultii DNA using the PCR targeting the SFG rickettsial ompA gene, and confirming by the gltA gene. Significant difference of the infection rates were observed between female and male yaks using the ompA primer set (68·3% vs 9·09%, P < 0·05; Table 2). Age also significantly influenced R. raoultii prevalence: infection rates were 2·91% in yaks aged 0–4 years, 71·4% in those aged 5–8 years, and 69·3% in those aged 9–12 years (P < 0·05; Table 3).

Table 2. Infection status of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in yaks of different sexes

Table 3. Infection status of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in yaks of different ages

This study obtained 36 ompA gene sequences and 2 gltA gene sequences, with nucleotide homology of 99·04–100% with reference strains of R. raoultii (see Supplementary Table S2 for details). Notably, sequence OR882807 showed 100% nucleotide sequence similarity to R. raoultii (GenBank accession: MK304547.1).

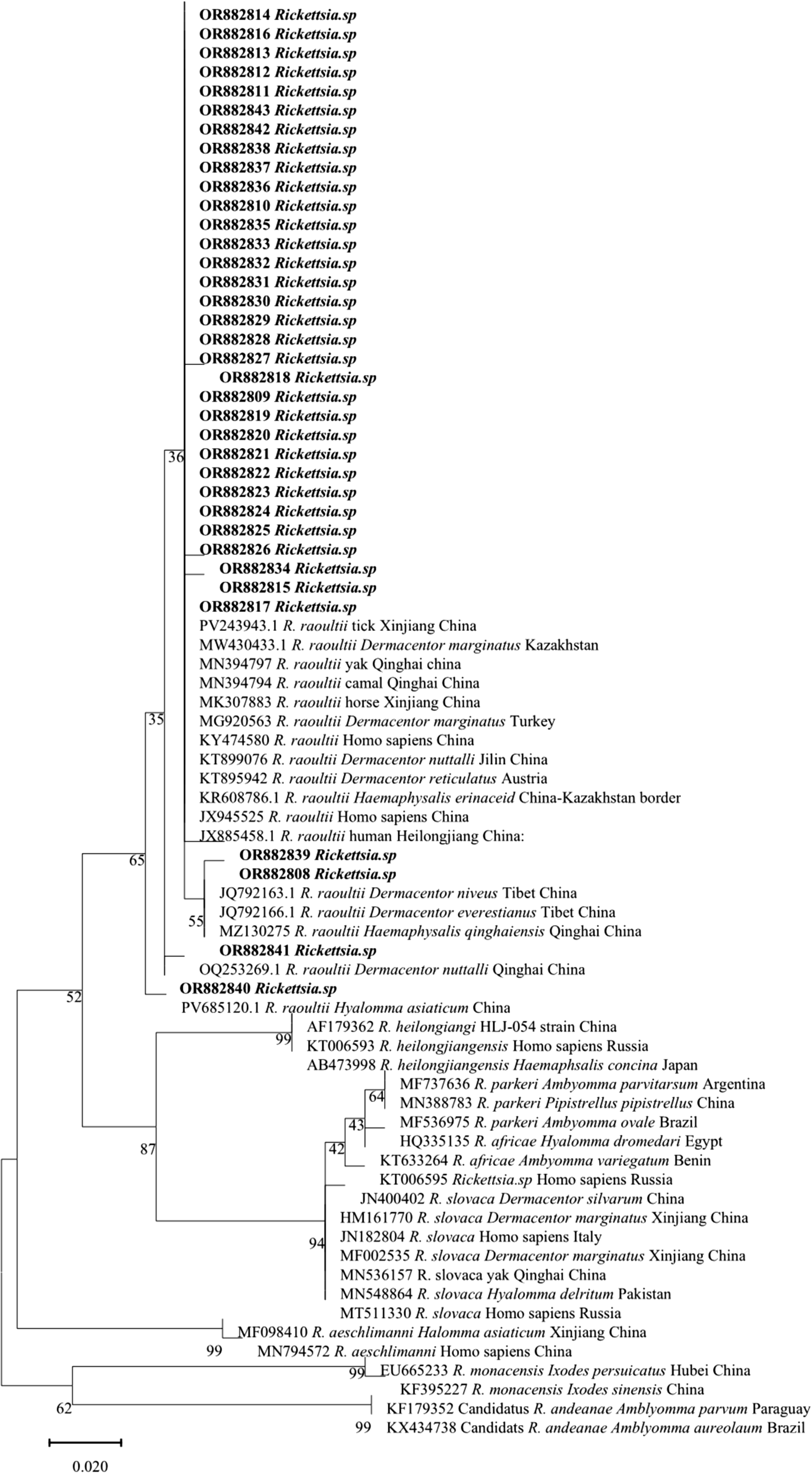

Phylogenetic analysis based on the ompA gene using the maximum likelihood method (Figure 1) confirmed that all ompA gene sequences obtained in this study clustered within the R. raoultii clade in the SFG rickettsiae phylogenetic tree, further confirming that the detected rickettsiae were R. raoultii.

Figure 1. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the rickettsial ompA genes using the maximum likelihood method. Sequences obtained in this study are shown in bold.

Specifically, sequences OR882827–OR882843 formed a tight cluster with reference strains of R. raoultii isolated from yaks, camels, horses, and Homo sapiens in Qinghai Province, China (GenBank accession numbers: MN394797, MN394794, MK307883, KY474580, KT899076). This indicated a close genetic relationship between R. raoultii strains derived from yaks in Xining, Qinghai, and those from other hosts in the same region. In contrast, sequence OR882841 clustered with the reference strain of R. raoultii isolated from Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis ticks in Qinghai Province, China (GenBank accession number: MZ130275), suggesting a potential transmission association between the strain corresponding to this sequence and H. qinghaiensis.

Furthermore, some ompA gene sequences obtained in this study (e.g. OR882814, OR882816, OR882838) were grouped into a large clade together with R. raoultii strains from tick sources in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (GenBank accession number: PV243943.1), Dermacentor marginatus ticks in Kazakhstan (GenBank accession number: MW430433.1), D. marginatus ticks in Turkey (GenBank accession number: MG920563) and Haemaphysalis ticks from the China-Kazakhstan border (GenBank accession number: KR608786.1). However, they showed a relatively distant genetic distance from R. raoultii strains derived from humans or ticks in Heilongjiang and Jilin Provinces, China (GenBank accession numbers: JX885458.1, KT899076) and from Dermacentor reticulatus ticks in Austria (GenBank accession number: KT895942). Meanwhile, all R. raoultii clades were clearly separated from the clades of other SFG rickettsial species, including Rickettsia heilongjiangensis, Rickettsia parkeri, Rickettsia africae and Rickettsia slovaca. This further verified the accuracy of the identification results for the ompA gene sequences in this study.

Similarly, phylogenetic analysis of the gltA gene sequences placed them within a single SFG rickettsiae clade (Figure 2). Sequences OR882806 and OR882807 clustered closely with reference strains including R. slovaca from D. marginatus in Xinjiang, China (MF002529) and R. raoultii from D. reticulatus in Russia (MK304547). The main rickettsial sequences obtained and their corresponding BLAST results are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 2. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the rickettsial gltA genes using the maximum likelihood method. Sequences obtained in this study are shown in bold.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to detect and analysed the prevalence of tick-borne diseases in yaks from Qinghai Province, China, at the molecular biology level by PCR technology. Tick-borne diseases represent a significant obstacle to the advancement of livestock production. As a major livestock province, Qinghai Province has a relatively wide distribution of ticks. It is evident that this has impeded the development of the livestock industry in Qinghai Province. Although zoonotic pathogens such as B. burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma spp., C. burnetii and other current pathogens were not detected in this study, there are still represents a potential risk to the livestock industry in Qinghai Province. The high infection rate for Rickettsia in yaks in this study was 46·5% (139/299), mainly because these yaks were exposed to tick movements. Previous studies have also indicated that tick-borne transmission was the main factor influencing the epidemic of Rickettsia (Regilme et al. Reference Regilme, Sato, Tamura, Arai, Sato, Ikeda and Watanabe2024).

Rickettsial diseases are caused by obligate intracellular bacteria within the SFG of the genus Rickettsia. Over the past three decades, the recognized spectrum and significance of tick-associated rickettsial pathogens have expanded dramatically. Several tick-borne rickettsiae, long considered non-pathogenic, are now associated with human infections, while novel rickettsiae of undetermined pathogenicity continue to be identified in ticks worldwide. This substantial increase in knowledge is largely attributable to molecular techniques, which have revolutionized diagnostics. The implementation of molecular methods facilitates the identification of both novel and previously recognized rickettsiae in ticks and enables rapid detection of infection in clinical samples through PCR and qPCR assays (Holland and Kiechle Reference Holland and Kiechle2005).

Notably, similar to the high prevalence of R. raoultii observed in yaks in this study, a microbiome-based surveillance study on urban wild boars in Barcelona also detected R. massiliae and R. slovaca in ticks, highlighting the widespread distribution of SFG rickettsiae in different host species and geographic regions (Carrera-Faja et al. Reference Carrera-Faja, Ghadamnan, Sarmiento, Cabrera-Gumbau, Jasso, Estruch, Borràs, Martínez-Urtaza, Espunyes and Cabezón2025). Additionally, European hedgehogs in urban environments have been found to carry various vector-borne pathogens, with age-related differences in infection rates, which aligns with our finding that yak age significantly influences rickettsial prevalence (Springer et al. Reference Springer, Schütte, Brandes, Reuschel, Fehr, Dobler, Margos, Fingerle, Sprong and Strube2024).

Currently, 31 tick species have been documented in Qinghai Province on the Tibetan Plateau. Among these, H. qinghaiensis and D. nuttalli are the dominant species, distributed widely across the province. H. qinghaiensis, a three-host tick, primarily parasitizes domestic animals including sheep, goats, yaks and cattle (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Tian, Liu, Niu, Han, Li, Guan, Liu, Liu, Luo and Yin2016b; Han et al. Reference Han, Yang, Niu, Liu, Chen, Kan, Hu, Liu, Luo and Yin2018; Song et al. Reference Song, Chen, Yang, Zhao, Wang, Hornok, Makhatov, Rizabek and Wang2018; Jiao et al. Reference Jiao, Lu, Yu, Ou, Fu, Zhao, Wu, Zhao, Liu, Sun, Wen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiong2021) and is a recognized vector for multiple zoonoses in Qinghai. Ticks serve as primary vectors for various diseases in Europe and Asia, including tick-borne rickettsioses, Q fever, anaplasmosis and tick-borne encephalitis viruses (Yaxue et al. Reference Yaxue, Hongtao, Qiuyue, Zhixin, Hongwei, Pengpeng, Quan and Lifeng2011; Kulakova et al. Reference Kulakova, Khasnatinov, Sidorova, Adel’shin and Belikov2014; Khasnatinov et al. Reference Khasnatinov, Liapunov, Manzarova, Kulakova, Petrova and Danchinova2016; Pukhovskaya et al. Reference Pukhovskaya, Morozova, Vysochina, Belozerova, Bakhmetyeva, Zdanovskaya, Seligman and Ivanov2018; Černý et al. Reference Černý, Buyannemekh, Needham, Gankhuyag and Oyuntsetseg2019; Kholodilov et al. Reference Kholodilov, Belova, Burenkova, Korotkov, Romanova, Morozova, Kudriavtsev, Gmyl, Belyaletdinova, Chumakov, Chumakova, Dargyn, Galatsevich, Gmyl, Mikhailov, Oorzhak, Polienko, Saryglar, Volok, Yakovlev and Karganova2019; Li et al. Reference Li, Wen, Li, Moumouni, Galon, Guo, Rizk, Liu, Li, Ji, Tumwebaze, Byamukama, Chahan and Xuan2020b; Ni et al. Reference Ni, Lin, Xu, Ren, Aizezi, Luo, Luo, Ma, Chen, Tan, Guo, Liu, Qu, Wu, Wang, Li, Guan, Luo, Yin and Liu2020; von Fricken et al. Reference von Fricken, Qurollo, Boldbaatar, Wang, Jiang, Lkhagvatseren, Koehler, Moore, Nymadawa, Anderson, Matulis, Jiang and GC2020; Jiao et al. Reference Jiao, Lu, Yu, Ou, Fu, Zhao, Wu, Zhao, Liu, Sun, Wen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiong2021). Rickettsiae are well-documented in Qinghai (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Walker, Liu, Han, Bai, Zhang, Lenz and Hong1987a, Reference Fan, Wang, Jiang, Zong, Lenz and Walker1987b; Zou et al. Reference Zou, Wang, Fu, Liu, Jin, Yang, Gao, Xi, Liu and Chen2011; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Diao, Zhao, Chen, Xiong, Shi, Fu, Guo, Pan, Chen, Holmes, Gillespie, Dumler and Zhang2014; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Li, Zhang, Li, Wang, Song, Wei, Wang and Liu2016, Reference Liu, Liang, Wang, Sun, Bai, Hu, Shi, Wang, Zhang, Huang, Liao, Huang, Zhang, Si, Huang, Jin, Liu and Li2020; Han et al. Reference Han, Yang, Niu, Liu, Chen, Kan, Hu, Liu, Luo and Yin2018; Song et al. Reference Song, Chen, Yang, Zhao, Wang, Hornok, Makhatov, Rizabek and Wang2018; Yin et al. Reference Yin, Guo, Ding, Cao, Kawabata, Sato, Ando, Fujita, Kawamori, Su, Shimada, Shimamura, Masuda and Ohashi2018; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Wang, Lu, Xu, Luo, Ni and Zhou2019; Shao et al. Reference Shao, Zhang, Li, Huang and Yan2020; Li et al. Reference Li, Jian, Jia, Galon, Benedicto, Wang, Cai, Liu, Li, Ji, Tumwebaze, Ma and Xuan2020a; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Pan, Jiang, Ye, Chang, Shao, Cui, Xu, Li, Wei, Xia, Li, Zhao, Guo, Zhou, Jiang, Jia and WC2021; Gui et al. Reference Gui, Cai, Qi, Zhang, Fu, Yu, Si, Cai and Mao2022), and H. qinghaiensis is a likely vector for the Rickettsia infections identified in yaks in this study. Phylogenetic analysis of the ompA gene sequences obtained revealed close relatedness to R. raoultii strains from yaks, horses and H. qinghaiensis within Qinghai. Conversely, the gltA gene sequences showed stronger affinity to strains identified in Xinjiang (China), Russia and Pakistan. This genetic diversity is consistent with findings from Yunnan Province, where a large-scale study detected 16 rickettsial species with high genetic variation, indicating that rickettsiae exhibit substantial geographic and host-related diversity in China (Du et al. Reference Du, Xiang, Bie, Yang, JH, Yao, Zhang, He, Shao, Luo, Pu, Li, Wang, Luo, Du, Zhao, Li, Cao, Sun and Jiang2024).

Our findings demonstrate significant epidemiological patterns as prevalence differed markedly between sexes (females: 68·3%, males: 9·09%; P < 0·05), and prevalence increased significantly with age (0–4 years: 2·91%, 5–8 years: 71·4%, 9–12 years: 69·3%; P < 0·05). The higher susceptibility of females aligns with previous research (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Liu, Niu, Liu, Guan, Xie, Luo, Wang, Wang and Yin2016a). The infection rate of female yaks (68·3%) was significantly higher than that of male yaks (9·09%), and this notable discrepancy may be explained by three interrelated factors: First, sampling was conducted in April, which overlaps with the peak period of tick activity in the study area. Female yaks included in the sample were predominantly older adults, and their daily grazing duration was marginally longer than that of younger male counterparts – this prolonged outdoor exposure translated to a greater cumulative risk of tick bites. Compounding this, female yaks exhibit relatively fixed activity ranges, often concentrating in low-lying pastures where high humidity and vegetation cover create favourable habitats for tick proliferation. In contrast, male yaks roam over broader areas, dispersing their exposure to tick-infested zones and thereby reducing bite probability. Second, female yaks experience physiological immunosuppression during pregnancy and lactation – key reproductive phases for breeding stock in this region. This transient decline in immune function impairs their ability to clear pathogenic infections, directly elevating susceptibility to Rickettsia colonization. These proposed mechanisms require further validation through complementary studies, including quantification of immunoglobulin levels (e.g. IgG and IgM) in female yaks across reproductive stages and long-term tracking of grazing trajectories to map spatial overlap with tick habitats.

The prevalence of R. raoultii in this study (46·5%) was higher than that in yaks from the Yushu region of Qinghai Province (32·1%, He et al. Reference He, Li, Sun, Kang, He, Guo, Ma, Wei, Li, Wk, ZH, Li, Qi, Yang, Zhang, Wang, Cai, Zhao, Hu, Chen and Li2022) and in sheep from the Nagqu region of Tibet Autonomous Region (28·5%, Liu et al. Reference Liu, Liang, Wang, Sun, Bai, Hu, Shi, Wang, Zhang, Huang, Liao, Huang, Zhang, Si, Huang, Jin, Liu and Li2020). This difference may be associated with the semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral ecological environment in the Xining area: fragmented pastures lead to the aggregation of ticks, increasing the probability of tick bites on yaks. In contrast, ticks are more sparsely distributed in pure pastoral areas such as Yushu and Nagqu, resulting in a lower infection risk. Herders in the Xining area have frequent contact with yaks (e.g. milking, assisting in calving and handling sick or dead livestock) and often remove ticks from the yak surface with their bare hands, putting them at a high risk of infection. The 46·5% infection rate identified in this study suggests the existence of a potential ‘yak-tick-human’ transmission chain in the local area. Such a high infection rate indicates significant risks. Without the timely implementation of prevention, control and treatment measures, the health and safety of local herders as well as the development of the livestock industry may face substantial threats.

This study has several limitations. First, during sample collection, blood samples from female yaks aged 0–4 years were lacking, and the sample size of the 5–8 years age group was excessively small (n = 7). This limits the representativeness of the results. Second, this study focused on determining the prevalence and species of tick-borne pathogens infecting yaks in Qinghai Province. However, since the ranch in question had previously conducted deworming (acaricidal) treatments, no corresponding tick vector samples were collected from the surface of yaks or the nearby grasslands. This made it impossible to identify the transmission vectors (e.g. whether H. qinghaiensis is the dominant vector) and to analyse the correlation between tick infestation and yak infection rates, thereby restricting the understanding of transmission dynamics. Additionally, no serological testing was performed: this precluded the determination of antibody levels and the duration of immune protection in yaks post-infection, making it difficult to develop targeted immunization strategies. Despite these limitations, the high prevalence of R. raoultii observed in Xining City yaks, consistent with findings from other studies in Qinghai, strongly suggests widespread rickettsial distribution among provincial livestock. Future investigations will expand tick-borne disease surveillance to livestock in other regions of Qinghai Province.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202510098X.

Author contributions

Xinyuan Zhao wrote and revised the manuscript; Xinyuan Zhao, Guanghua Wang, Pei Zhang, Guangwei Hu, Shang Shenbin, Xuelin Shan, Hejia Ma and Yong Hu were responsible for sample collection and sample processing. Xinyuan Zhao, Guanghua Wang and Hejia Ma completed the experimental process and conducted statistical analysis of the data. Guanghua Wang, Yingna Jian, Xiuping Li, Liqing Ma, Yali Sun and Jixu Li designed the paper and rigorously reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript. Jixu Li supervised and managed the project.

Financial support

This work was funded by the Qinghai University Research Ability Enhancement Project (2025KTST05).

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures were carried out according to the ethical guidelines of Qinghai University (permission number: PJ2024-02-131).