1. Introduction

There are many well-known connections between mathematics and music. These include the Pythagorean numerical study of harmonics and tuning systems (e.g., Jeans, Reference Jeans1937; Fokker, Reference Fokker1949), group-theoretic representations of musical structures (e.g., Forte, Reference Forte1973; Crans et al., Reference Crans, Fiore and Satyendra2009), the mathematics of bell ringing (e.g., Fletcher, Reference Fletcher1956), and many others (e.g., Fauvel et al., Reference Fauvel, Flood and Wilson2003). Here we are interested in an under-appreciated connection between the two: both mathematics and music employ distinctive notational systems, and these notational systems play important, active roles in the respective practices. Practitioners engage in debates about notation, develop new notational systems, complain of the restrictions notation places on the practice in question, and bemoan the complexities of notation. But the similarity between mathematical and musical notation runs deeper than this. After investigating what notation is expected to deliver in music and in mathematics, we suggest that in both cases it is useful to think of the notational systems as models of particular musical and mathematical structures. This idea helps make sense of the variety of roles notation plays, the debates over notation, and the pursuit of better notational systems.

The philosophical discussion of notation in music is well advancedFootnote 1, so we will start there. We will rehearse some of the lines of thought about musical notation in order to get a feel for the variety of roles musical notation is plays. Then we will turn to mathematical notation, where there has been much less philosophical attention and there is a poorer understanding of the role of notation.Footnote 2

2. Notation and Convention

In order to motivate the subsequent discussion, let’s dispense with a rather natural, but ultimately misguided, view about notation. It is tempting to think of notation, be it mathematical, musical, or whatever, as nothing more than a conventional system of signs or names of things and it’s the things that matter: any name will do.Footnote 3 To see why this view is misguided one only has to think of cases where a name encodes information about the object it names. Examples include ‘amplifier’, and ‘Cambridge’. Our concern here, however, is not with onomastics or names in general but with particular kinds of names or symbols found in mathematics and music: mathematical notations and musical notations.

There are certainly conventional elements in mathematical and musical notation. For example, variables in mathematics are usually italicised. It is useful to distinguish variables, so some notation is required, but the notation here is purely conventional. Similarly, in musical notation, note-heads are usually represented by rounded shapes rather than squares or diamonds (although this wasn’t always the case). But amidst the various conventional elements it is easy to overlook the non-conventional and thus miss the variety of roles notation plays in both mathematics and in music. A rose by any other name may well smell as sweet, but in mathematics and music it’s different.

It is also worth recognising that mathematical and musical notation did not just fall from the heavens – a great deal of effort by many people, over long periods of time have been involved in developing the various notational systems. An appreciation of the historical notational developments and contexts can contribute to an understanding of notational convention, but this aspect is largely beyond the scope of this paper.Footnote 4 That, in itself, should give us a clue that there is more to these notations than meets the eye. If they were merely conventional, what would be the point of arguing over them? This is at least a reason to dig deeper and consider ways in which notation is more than merely a system of conventional signs. As we will see, good notation can facilitate new developments, help in the abstraction process, and can even help facilitate explanations. We start with musical notation.

3. Musical Notation

The evolution of Western musical notation over more than a thousand years has resulted in a symbolic notational system known as Common Western Musical Notation (CWMN), which is, in many ways, both efficient and elegant as a method of communication of musical intention. It is also well documented and its conventions largely fixed (e.g., see Gould, Reference Gould2011). Thus both its familiarity and ubiquity can be regarded as a mark of its effectiveness for the job it does in, for example, representing ‘musical works’. However, a word of caution is needed here, as a significant strand of the philosophy of music in recent years has been directed to the problem of tackling the question of what constitutes a musical work. Where is a musical work situated?; when did music change from music-making to the composition and performance of musical works per se?; where does the composer figure in all this? It is from this ontological perspective that most discussion of musical notation arises in the relevant literature. While the arguments that revolve around this issue are lively, discussion of musical notation – often in the form of a score – is usually relegated to bolster a particular view of how much of the musical work in question it contains.

In what follows, we are more interested in comparing notational types than making claims around boundaries between notations and associated complete ‘musical works’ and their authorship (Goehr, Reference Goehr2007). Almost all musical notation (whether or not in the form of a scoreFootnote 5) requires interpretation beyond that notationally specified. This interpretation typically relies on knowledge of the relevant performance practice associated with the music in question and comprises a significant part of the pedagogy of learning a musical instrument. To give a simple example, the human voice and many instruments are often sounded using vibrato – small variations of pitch which are usually not indicated in the score (on the other hand, sometimes ‘senza vibrato’ or ‘molto vibrato’ may be indicated). Likewise, in many performance practices, rubato is common, in which the performer makes local changes in tempo in order, for example, to mark musical divisions in the music. Where a work resides between the score and a particular performance is moot, but not under discussion here.Footnote 6 Rather, our focus is on the affordances and constraints of different notations on different aspects of the practices of a variety of Western music.Footnote 7

Musical notation serves many purposes. It’s worth sketching notation’s different functions, which are much wider than a prescription for performance. For example, in the form of a score that is a musical transcription, musical notation can be considered descriptive and serve as a record of a particular performance, warts and all (Gould, Reference Gould2011, p. xiv; Cole, Reference Cole1974, p. 16).Footnote 8 In such cases, even performance mistakes are transcribed along with any other extraneous sounds.Footnote 9 Alternatively, a score can serve as a representation of some perfect performance. On this reading a score is not any particular performance – since no performance is perfect. Rather, it’s a documentation of aspects of an ideal abstract performance to which any actual performance aspires (or, perhaps, approaches as the limiting case).

Note again that a score may represent some aspects of the music, but not others, as should be clear from the discussion of vibrato and rubato above. Related to this last purpose, a score can be prescriptive, and so serve as a recipe for the performance of the work in question.Footnote 10 While this is similar to the previous purpose (the perfect performance), here the focus is on the generation of the music; the music that results may well disregard some elements specified in the notation and add others. Along similar lines, the score might be simply a mnemonic and, as found in some popular music scores, include only the song’s lyric and simple chord charts as a reminder of how a known piece is to be played. Some scores may deliberately lack detail, not because the unspecified details are understood, but because the details are deliberately left to the performer to fill in as she sees fit (see examples below). Here the score is a kind of invitation to play music along only partially-specified lines.

Scores can serve purposes not directly related to performance. For example, one of the most fundamental purposes of music notation is to allow the legal protection of musical compositions in the form of copyright. In the UK, the British Copyright Act of 1911 distinguished between music’s material objects (e.g., a recording of a piece in the form of a mechanical record) and its abstract copyright (Goehr, Reference Goehr2007, pp. 218–219). Musical notation can also be primarily pedagogical, for example directed at learning an instrument. Here the focus is not on playing a particular piece but on acquiring the basic skills required for playing any piece on the instrument in question.Footnote 11

Notation can also serve as a representation of some musical abstraction that may not, for example, be intended for performance. To give a trivial example, a piece of clothing (e.g., a sartorial tie) may have a decorative design comprising notational symbols. Or notation in the form of a musical sketch might serve a composer as an aid in the process of composition, by suggesting, for example, new musical structures (e.g., rhythmic, melodic or harmonic, etc.).Footnote 12 Without entering into the entanglements of what constitutes a musical work, a ‘short score’ not yet arranged for particular instruments could also be included in this category; the short score is more abstract than the full score in that it may lack precise details regarding exactly which instruments are required in the indicated music.

Sometimes notation can be used to help document known patterns and can also serve to highlight similarities and differences between musical pieces. For example, we might want a form of notation that emphasises the similarities (rather than the differences) between a piece or section of music and a transposition of it to a different key (i.e., ‘move’ the music higher or lower in pitch). Standard Western theories of musical harmony allow chords to be labelled using Roman numerals that remain constant regardless of pitch transposition. So, for example, the chord progression C, D minor, G7, in the key of C major, and A, B minor, E7, in the key of A major can both be represented as I, ii, V7. This system is considered functional in the sense that each chord is considered in relation to its tonal function – I is the tonic and equivalent to the key signature; V is the dominant and often leads back to I, etc. Thus, each chord represented by a Roman numeral is not any particular chord until a key signature is specified. Rather, the notation specifies structural relations between potential chords.Footnote 13 Here, arguably, these kind of notations have an advantage to the graphical symbols of CWMN, which, in this context, might also be thought to capture too much: rather than indicating functional relations between chords given by the Roman numeral notation, CWMN dutifully represents each chord, note by note. Indeed, historically figured bass notation, developed during the early 17th Century, gets closer to this idea through representing a notated bass line combined with a numerical notation indicating notes to play above the bass (Rastall, Reference Rastall1983, p. 202). On the other hand, unlike CWMN, such notations do not capture such aspects such as register or chord voicing.

With so many different purposes beckoning, it should come as no surprise that no notation system can simultaneously serve all such purposes. In particular, for all its strengths, well-documented elsewhere, CWMN is arguably inadequate in a number of the above contexts in relation to timbre, pitch and temporality/rhythm. For example, without the additional instructional text or annotations that form part of CWMN, its purely symbolic graphical apparatus cannot easily capture:

i. scores requiring certain improvisation or musical interpretation/realisation are not easily specified in CWMN (this broad category is discussed at length in the musical examples below);

ii. certain tempo variations (e.g., ‘on top of the beat’ verses ‘behind the beat’; incremental increase or slowing of tempo; rubato and ‘loose’ playing);

iii. notes whose length is not a multiple of a power of 1/2 in duple time or 1/3 in triple time (e.g., a note of length 1/19 or a note of length √7);

iv. the specific sound (or timbre) of a given instrument or the manner of playing a particular note. (For example, on a guitar, a middle C sounds timbrally different when played on the B string compared to higher up the fretboard on the D string.);

v. tones outside of the standard chromatic equal-tempered scale (e.g., the various possible tones between B and C, which can occur as part of different tuning systems and/or in complex microtonal music), though see example in Figure 4 below;

vi. differences between finger bends, slides, hammer on and pull offs on fretted stringed instruments such as a guitar;

vii. subtle changes in volume, either the absolute volume of sound, or the relative volume (e.g., between instruments).Footnote 14

Given the notational contexts that CWMN is less well suited for, as outlined above, there has been considerable work in contemporary music devoted to devising new musical notational systems and various extensions of CWMN. These follow on from the subtle modifications over the course of the Nineteenth century, at a time when the notational system was considered complete (Rastall, Reference Rastall1983, p. 231). In the Twentieth century, there were many radical approaches to modifying and extending and even jettisoning CWMN as composers reached the limits of CWMN as a system. Many of these were well-documented last century by, for example, Karkoschka (Reference Karkoschka and Koenig1972), Cole (Reference Cole1974), and Stone (Reference Stone1980). A focus of this work was attempting to accommodate varied approaches to temporality and the representation of complex changes in rhythm and tempo. Composer Elliott Carter’s approach to notating a ‘tempo glissando’, for example, is documented in Cole (Reference Cole1974, p. 72), and the use of ‘fanned’ beamed groups indicating changes in tempo (Gould, Reference Gould2011, p. 158) has now become commonplace. Such individual approaches as the above have also been employed by other Twentieth century composers from Stravinsky, Messiaen, Ligeti, Boulez and others, and are well represented in the works referred to above. Our aim is not to offer a comprehensive account of such different notations systems developed or even an account of the most significant notational systems, all of which are readily available elsewhere. Rather, we deliberately choose a number of different notational systems to help emphasise the variety of purposes to which such systems can be put.

We now turn to exploring some of the alternatives and extensions to CWMN via examples of different notational systems in order to get a feel for them and to appreciate their strengths and constraints. It is important to note that these alternative systems are not typically advanced as replacements for CWMN across the board. Rather, the various notational systems are best thought of as alternatives to CWMN for particular musical purposes (and usually for a particular composer and sometimes for a particular work). In particular, we are interested to explore what a given notation in question is supposed to achieve and why it is being used. We start with fairly familiar examples and move to some radical departures from CWMN. A common theme in much of what follows is the use of novel notation to produce new musical possibilities – possibilities that are, in some sense, overlooked by CWMN.

With the exception of the absence of bar-lines and clefs (understood as the treble and bass of the usual ‘grand staff’ for piano), Figure 1 employs CWMN. Nevertheless, there is more going on here than at first sight. Satie loves a musical joke: an English translation of the title is ‘The carrier of large stones’. He plays with this idea in a number of ways in the notation. Firstly, he inserts many unusual performance instructions in his native French: the example shown here, Péniblement et par à coups, translates as ‘in fits and starts’. This remark is a cross between a regular performance instruction and part of the unfolding of the playful narrative programme, engagement with which can be understood as what Dickson (Reference Dickson2024, p. 3) would categorise as the ‘extra-notational interaction’ aspect of a score.

Figure 1. Erik Satie, ‘Le Porteuer de grosses Pierres’ (1913).

We also find an unusual use of fermatas (pauses – seen below the staff on the first and third lines), which are inserted in unexpected places to break up the regular temporal flow of the semi-quaver notes. This metrical discontinuity corresponds to the performance instruction (‘in fits and starts’), portraying the physical struggle of carrying large stones (in additional, the fermata symbol on the page also has the look of a stone). This gives rise to playful tensions between the way the piece looks as notation and the way it sounds, and represents something of a private joke between composer and score reader. This private game is facilitated by the humorous mild notational transgressions that Satie takes with the conventions of CWMN.

In Figure 2 we see only a fragment of the opening melodic line of The Beatles’ song ‘Hey Bulldog’. This aims to remind the singer or score reader of the main vocal tune, after which the lyrics and guitar chords follow (not fully reproduced here). The main intended purpose is to aid the production of a performance, but little detail is required or notated. Initial rhythmic and melodic details are presented but the underlying assumption is that the performer knows the piece and only requires a reminder. However, in this example, the notated melodic line throughout is that sung by John Lennon, whereas the initial three quaver notes are also sung by Paul McCartney a major third higher. Arguably, McCartney’s contribution can also be heard as the main melody at this point, but this is not acknowledged in the published notation (however, see Figure 4 below).

Figure 2. Excerpt from ‘Hey Bulldog’, by John Lennon and Paul McCartney from The Beatles Guitar Chord Songbook.

In Figure 3 we see an obvious departure from a standard score, yet it still employs significant aspects of CWMN. In this composition for one or two pianos, Morton Feldman specifies the pitches: notes and chords – but their temporal order and their duration are unspecified – thus overturning the temporal convention of CWMN along the x-axis. Instead, the sequence of events is free, and durations are left to be determined by the acoustics of the instrument(s) used in the performance and the space in which it occurs. In this sense the composition can be considered as ‘underspecified music’ enabled through Feldman’s experimental notation. In other examples (e.g., Projection 2, from the early 1950s), Feldman specifies temporal durations and sequence, but not pitch (Boutwell, Reference Boutwell2013). The aim is to transfer the responsibility for some aspects of the performance away from the composer to the performer (or the acoustics of the instruments), in the process redefining the kind of musical identity that a score can specify. Other notations embracing temporal notational alternatives include proportional spacing, used by Feldman and others, in which duration is either roughly or precisely indicated by the horizontal space (e.g., in centimetres) given to musical events on the page. This is well represented in the literature and has been codified to an extent in Gould, Reference Gould2011 (pp. 629–634).

Figure 3. Morton Feldman, Intermission 6 (1953).

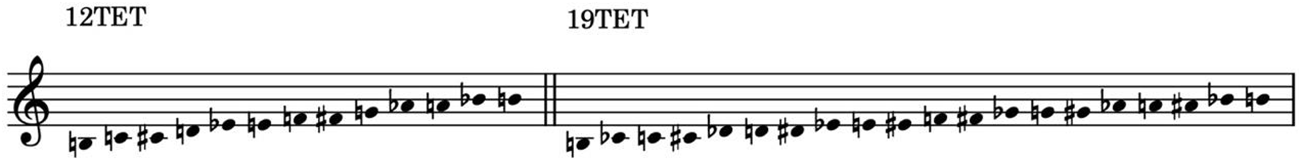

If Feldman, in the example above, seeks new temporal explorations in composition and performance, other composers have rethought continuities through explorations in pitch and musical temperament. Under a system employing equal temperament (as with a piano keyboard), we can think of CWMN as assuming twelve equal divisions of the octave, sometimes referred to as 12TET or 12EDO,Footnote 15 in which the seven note names A to G are raised or lowered via flat or sharp symbols to arrive at the twelve discrete divisions of octave, as shown in Figure 4 as 12TET. Simple extensions to the CWMN symbols used to indicate these sharps, flats (and naturals) in CWMN can be used to indicate quarter-tones in microtonal 24-TET (Gould, Reference Gould2011, pp. 94–98). A more unexpected use of CWMN, however, using wholly standard (unmodified) symbols, has been adopted to notate microtonal 19TET music.

Figure 4. Chromatic steps in CWMN and 19TET microtonal notation.

As shown in Figure 4, a nineteen tone division of the octave (19TET) can be notated by eschewing the enharmonic equivalence relationship between sharps and flats (other than B-sharp/C-flat and E-sharp/F-flat), so that for example, rather than indicating equivalence, B-flat is a 19TET chromatic step higher than A-sharp (Woolhouse, Reference Woolhouse1835, p. 50). Figure 5 shows the opening bars of Lennon-McCartney’s ‘Hey Bulldog’ notated in both 12TET (a) and translated to 19TET (b) using this notational arrangement. (The example, however, favours McCartney’s opening notes as the main melody over Lennon’s.) Interpreted as (12TET) CWMN, the 19TET version might appear simply to swap tones for chromatic semitones, however, as shown in the figure, the number of chromatic steps between adjacent melodic notes is, in fact, maintained once interpreted according to Woolhouse’s schema discussed above.Footnote 16

Figure 5. ‘Hey Bulldog’ with chromatic steps in 12TET and 19TET.

Heinrich Schenker developed his notation in the early 20th Century as an aid to musical analysis. As shown in Figure 6, Schenkerian analysis combines aspects of

Figure 6. Heinrich Schenker, analysis of Mozart Sonata in F Major, K.332.

CWMN with that of Roman numeral and figured bass notations. In this tonal analysis of a phrase from the Allegro of Mozart Piano Sonata in F (Allegro, bars 41–48), note values typically do not indicate duration, but rather a hierarchy of tonal significance within the music. Thus the notation is not intended for direct performance, but rather provides reductions of the music at hand, intended to indicate its structural essence. Schenkerian analysis has also been used in recent times for the analysis of popular music, for example that of The Beatles (Moore, Reference Moore1997). To its advocates, the notation offers fresh insight for understanding tonal music, which would otherwise not be as readily evident through other means.

In Cage’s ‘Solo for Piano’ we find a celebrated compendium of experimental notation practices, in which each page of the score differs from the others (Figure 7). The notation here is partially indeterminate with regard to both pitch and duration, whilst being underpinned by the conventions of CWMN. In response, David Tudor, for whom Cage wrote the composition, chose to write out his own more ‘fixed’ realisation in advance of performance. A similar practice has been adopted by more recent performers such as Philip Thomas, who gives detailed examples of the methodology for his realisation of the composition in Thomas (Reference Thomas2013).

Figure 7. John Cage, ‘Solo for Piano’ (1958), p. 9 (extract).

It is worth noting that sometimes musical notation can serve as a piece of visual art and there are close connections between the two. For example, it is not unusual for John Cage’s scores to be hung in art galleries. Music produced from such visual art pieces might be thought to be inspired by the notation in question, in much the same way as

Harrison Birtwistle’s Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum (1972) is a meditation on Paul Klee’s 1922 oil transfer drawing Die Zwitscher-Maschine (‘The Twittering Machine’).

Computer technologies have enabled a wide variety of real-time or ‘live’ computer-based digital scores (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Armstrong, Hoadley, Wilson, Cottle and Collins2025; Vear, Reference Vear2019). Figure 8 shows a screen capture from Hall’s composition All the Chords, which uses a form of digital notation that is animated onscreen as a live score for the performer. Hall’s notation can be interpreted in a number of ways, assisted by the live animation, which can rotate the helix and ‘refresh’ the view with new collections of notes. Here absolute musical register (pitch) is not indicated, however, the notation suggests chord inversions or relative pitch. The helix can be rotated to either aid reading of the notation or to indicate entry or emphasis of a given note. Thus digital scores can accommodate different forms of indeterminate musicFootnote 17 and can also be made visible to the audience at a performance. Sharing the score in this way functions as a kind of aid to understanding the music and as a piece of time-based visual art in its own right (Hall and Blackwell, Reference Hall and Blackwell2014).

Figure 8. PitchCircle3D helix, All the Chords (in Hall and Blackwell, Reference Hall and Blackwell2014).

The notation shown in Figure 8 is controlled by user interaction with computer code, an established tool for the creation of so-called algorithmic music.Footnote 18 Domain-specific computer music software such as SuperCollider (https://supercollider.github.io), for instance enables the ‘live coding’ of computer music (e.g., https://blog.toplap.org). In other contexts, computer code is used to encode more conventional music notations including CWMN for transfer between different music notation software. MusicXML (https://www.musicxml.com), like the code that sits behind web pages, is also a human readable schema using plain text, intended as an intermediate step in musical representation.

As the preceding examples and discussion make clear, a great deal of modern experimental musical notion is invoked in the service of indeterminacy (Behrman, Reference Behrman1965). This is, in part, due to a desire to return to a more improvisational style of music – a style that arguably grants greater artistic freedom to composer and performer alike. In each case built to greater or lesser degrees on CWMN, this approach can be seen as a move away from particular details towards a more general and abstract musical representations.Footnote 19

4. Mathematical Notation

Now we turn to mathematical notation. We start with a simple, familiar example: two notational systems for the natural numbers. The Indo-Arabic numerical system is a brilliant notational system. Apart from anything else, the most important property of the natural numbers – recursiveness – is built into the notation (Brown, Reference Brown2008). This has many flow-on consequences. For a start, it leads very naturally to simple algorithms for arithmetic operations (+, –, ×, ÷).

Another familiar example comes from differential calculus. There are several notational systems for derivatives in calculus but here we just contrast two: Lagrange and Leibniz notation. In Leibniz notation we have dy/dx for the first derivative and d2y/dx2 for the second derivative of a real-valued function y; in Lagrange notation we have y’ for the first derivative and y’’ for the second derivative. Clearly Lagrange’s notation is more economical but it does not generalise very well to multi-variate calculus. For example, in Lagrange’s notation there is no straightforward way to represent the mixed partial derivatives: ∂2f(x,y)/∂x∂y, of a multi-variate function f, nor is there a way to distinguish this from ∂2f(x,y)/∂y∂x. Taking things a little further, it might be argued that Leibniz’s notation prompts moves to multivariate calculus, by suggesting very natural questions about differentiating with respect to different independent variables.

An historically-important example is the representation of complex numbers as ordered pairs of real numbers. A complex number is a number of the form x+yi, where x and y are real numbers and i = √–1. Complex numbers are crucial for all manner of intra-mathematical and extra-mathematical applications, but initially they were treated with some suspicion because of difficulty in grasping √–1. But we can simply introduce some new notation for complex numbers and treat them as ordered pairs (x,y). Moreover, these ordered pairs can be interpreted geometrically (thanks to Descartes’ innovation of analytic geometry, where ordered pairs can be seen as points on the Cartesian plane. With all this notation in place, the complex number (x,y) is just the vector with the origin as the initial point and the point (x,y) as its terminus. Addition of complex numbers is then vector addition and multiplication of complex numbers can be interpreted as a stretching (or squeezing) and rotation of vectors. There’s no need for the details here but this geometric interpretation of complex numbers (via the ordered-pair notation) helps us to understand them (Ahlfors, Reference Ahlfors1966).

Next we consider the role notation can play in solving mathematical problems. Bisecting an angle with only a straightedge and compass involves dividing an arbitrary angle into two equal angles, using only the aforementioned tools. This construction is straightforward and has been known since antiquity. But the related problem of trisecting an arbitrary angle remained unsolved until 1837. Some angles can be trisected using the specified construction methods but, crucially, not all angles can. That there are such trisection-resistant angles was shown by Pierre Wantzel. Remarkably, the proof came from abstract algebra, not from geometry. A quick sketch of the connection between these two is worthwhile, because the algebraic notation is crucial to the proof in question (Bold, Reference Bold1982, pp. 33–37).

We start by cataloguing the legitimate, straightedge-and-compass constructions (drawing a line through two given points, constructing a circle with centre at one given point and running through another given point, and so on). We then provide notation for the basic geometric objects (lines, points, and arcs of circle) and note that we can represent these objects in the Cartesian plane, in the usual way. We then show that the permissible geometric constructions give rise to a small set of algebraic operations on line lengths: addition, subtraction, division, multiplication, and taking the square root. The idea here is that if two line segments of lengths, a and b are given, we can construct line segments of length ab, a+b, a–b, a/b and √a. Moreover, these are the only algebraic operations the geometric constructions licence. We then show that constructing an angle of θ radians is equivalent to constructing two line segments such that the ratio of the lengths of the line segments is cos(θ).

What we have done here is to again forge a link between geometry and algebra. This allows us to apply algebraic methods to the problem at hand. We have thus transformed the problem from one of geometry – that of constructing an angle 1/3 the size of a given angle – to one of abstract algebra, namely, that of determining whether, for all θ, cos(θ) can be obtained by successive applications of the algebraic operations just listed. In particular, consider the problem of trisecting an angle of π/3 radians, which requires the construction of an angle of π/9 radians. Using the notation just described, this construction is transformed into an algebraic problem involving the roots of polynomials. If cos(π/9) were constructible, it would be the root of a polynomial with powers 0, 1, or an even integer, and with rational coefficients. It can be shown that cos(π/9) is not the root of any such polynomial. (Invoking the triple-angle formula from elementary trigonometry, cos(π/9) can be shown to be the root of 4x 3 – 3x – 1/2.) The straightedge-and-compass construction is thus impossible.

The fact that cos(π/9) is not the root of any of the polynomials in question is the key to the impossibility result, but it is important to see how the problem needs to be set up as an algebraic problem. This involves the introduction of algebraic notation for the geometric objects and operations, and noting that the geometric operations give rise to familiar algebraic systems. Again, we see good mathematical notation playing a key role in delivering a mathematical explanation. But notice that the explanation goes beyond pure mathematics. We have also explained why all attempts at a straightedge-and-compass trisection of π/3 have failed and why anyone who claims to have a general method of trisecting angles with only straightedge and compass is not taken seriously by mathematicians.Footnote 20

Finally, an example of the use of mathematical notation in a surprising application: juggling.

There are a number of different notations for juggling moves. Most notations are rather inefficient. For example one juggler complained that when he tried to write down a juggling move it resulted in ‘three days of work and two and a half pages for a 1 second move’ (Gray, Reference Gray2012). Site-swap (or Cambridge notation) is a very interesting and economical numerical notation independently developed in the mid-1980s by mathematician jugglers at the University of California Santa Cruz, the California Institute of Technology, and the University of Cambridge. The basic idea is that the notation indicates the order that balls (or whatever) are thrown, how many ‘beats’ each ball is in the air, and whether the ball is caught by the same hand that threw it or by the other hand. So, for example, a standard three-ball cascade has three balls and each is in the air for three beats so this is written as ‘3,3,3’ or simply ‘3’. Since 3 is odd, every ball is caught by the opposite hand to the one that threw it. A three-ball shower is notated ‘5,1’, where each ball is in the air for five beats, is caught by the opposite hand to the one that threw it, and it takes one beat to pass a ball between hands.

The notation has many advantages over existing juggling notation but one in particular deserves singling out: the notation led to the discovery of new juggling routines. Once standard moves were documented in site-swap, ‘gaps’ (i.e., unperformed moves) became apparent. For example, the move 4,4,1 was discovered via site-swap (Beek and Lewbel, Reference Beek1995).Footnote 21 Not all site-swap sequences correspond to humanly-possible juggling moves and not all aspects of juggling are represented (e.g., throwing from behind the back or under the leg). Site-swap notation also has some very nice and useful mathematical properties. For example, the arithmetic mean of the numbers in the site-swap sequence tells you the number of balls needed to perform the trick and the number of legitimate site-swap sequences that are n digits long using no more than b balls is bn.

Site-swap is a very efficient and instructive notation. As already noted, it was developed independently by three people. This, alone suggests that there is something non-arbitrary about it. But crucially, this notation led to the discovery of new juggling moves. This shows that site-swap is much more than a way of naming known items.

5. Models

A model is a representation of particular features of a target system and is designed for a specific purpose.Footnote 22 Familiar examples include maps and blueprints (Casati, Reference Casati2024). It is important to note that models also typically misrepresent some aspects of the target system. Often carefully-chosen misrepresentations are why a model is so valuable. For example, for some purposes a map can be more useful than a satellite photograph, even though the latter is a more faithful representation of the terrain. Very often models misrepresent by omitting detail – lying by omission – as when the London tube map ignores distance between stations and shows only network connections. But sometimes models distort, and they can also exaggerate, as, for example, when scientific models of ocean waves treat the ocean as infinitely deep (Maddy, Reference Maddy1992).

Models can be used for different purposes. For example, a street map of London is a very poor way to navigate the London underground and, similarly, a London underground map is a poor way to navigate the streets of London. A model should be assessed not in terms of its accuracy in representing its intended target system but for how well the model suits its specified purpose.Footnote 23 Of course a model needs to bear some resemblance to its intended target but the resemblance here does not need to be anything so tight as an isomorphism and the degree and nature of the resemblance will be determined by the purposes for which the model will be used.

It’s worth pausing to consider how models can achieve their purposes when, as is typical, they don’t faithfully represent their target systems. There are a number of quite different reasons for this, corresponding to the nature of the idealisation in question.Footnote 24 Sometimes the idealisations are minor ones: it’s close enough for the purposes at hand.Footnote 25 Sometimes the idealisations cancel out as when air-molecule movement is ignored in a pendulum model because the molecular movement is in all directions and thus (approximately) cancels out (i.e., the mean air molecule velocity is approximately zero). Sometimes the idealisations make the model tractable, as when we use (continuous) differential equations rather than (their discrete analogue) difference equations in population models in ecology. Sometimes an idealisation is invoked because there just seems no other way forward. For example, in risk analysis, we sometimes treat various relevant risk factors as independent when we have no clue about the relevant dependencies.

Despite all the lies, omissions, exaggerations, and distortions, models work. How can this be? In some cases it’s straightforward: if the idealisations are small enough and the level of precision required is course-grained enough, the idealisations don’t matter. For example, it doesn’t matter that not every detail of Oxford Street is represented on the London street map; typically we simply are not interested in such precision. Similarly, it is easy to see why the idealisations don’t compromise the model when they cancel. More puzzling, however, are other cases where the idealisations are neither small nor cancelling. It’s tempting to think that such idealisations really would lead to trouble.

Sometimes models can be very good at achieving their intended purpose despite many quite significant idealisations. Indeed, in many cases, the success of the model depends on such idealisations. To see one way this can happen, we shift our focus to a somewhat different case: an impressionist painting. There are various misrepresentations in impressionist paintings, with the kind and severity of the misrepresentations depending on the style of painting. Here are a few of the misrepresentations we find in impressionist works:

i. Landscapes are three-dimensional but paintings are two-dimensional.

ii. Landscapes are dynamic yet paintings are static.

iii. Landscapes do not come with a privileged perspective but paintings do.

iv. Landscapes are not made up of many tiny dots yet some (pointillist) paintings are.

v. Landscapes are sharp and fully determinate but impressionist paintings are not.

We suggest that an impressionist painting can achieve its goal, not despite the inaccuracies and omissions, but because of them. A Monet painting of a lily pond, for example, with its many and obvious inaccuracies, better conveys the interaction of flickering light on the lily pond than any photograph or even a naked-eye viewing. Taking the analogy between an impressionist works and scientific models seriously, hints at how scientific models may fulfil their function because of (well chosen) idealisations.

An example here will help. Minimal models are models that are designed to represent only the most fundamental causal interactions of the system (Weisberg, Reference Weisberg2013). Consider the Schelling (Reference Schelling1971) segregation model. This model represents households as squares on a piece of graph paper and two different races of people by different kinds of coins occupying the squares on the graph paper. On the assumption that people will move to a more desirable location if they are unhappy where they live, Schelling demonstrated that racially segregated neighbourhoods can result from a very weak assumption, namely, that individuals have a slight preference for living near their own kind. The model is minimal in its representation of neighbourhoods (collections of squares on a grid) and of people (two kinds). But what is of interest in this model is that it (arguably) shows that racially-segregated neighbourhoods are possible, even without overt racism.

The Schelling model would not be able to deliver this result, were it more realistic. To be more realistic, it would need to resemble real urban neighbourhoods, but which ones? If the model were a realistic portrayal of, say, Miami, the strongest conclusion the model would be able to deliver would be that it is possible to have racially-segregated neighbourhoods in Miami without overt racism. In this case, it would be reasonable to think that the result stemmed from some odd geographic fact about Miami or perhaps a quirk of the climate in Miami. The lack of realism in Schelling’s model sidesteps these issues. It succeeds in its intended purpose not despite its lack of realism but because of it.

6. Notations as Models

The discussion of models in the previous section carries over straightforwardly to musical notation. As we have seen, there are various things we might want to do with musical notation. These different purposes – such as copyright protection, providing a recipe for a performance, representing an indeterminate work and so on – are not all best served by the same notation. Nor are all these purposes equally important in a given context. Moreover, in these cases the musical notation is playing a representational role – the notation represents some target system (e.g., an actual or abstract musical piece).Footnote 26 The notation serves as a model and, depending on the purpose, different models will better serve the purpose in question.

More surprising, perhaps, is that mathematical notation shares these characteristics and can usefully be thought to be a model of the mathematical objects or mathematical structures in question.Footnote 27 To be clear, we are not talking about mathematical notation modelling physical systems here as in, for example, using the Navier-Stokes differential equations to model fluid flow through a pipe. We have in mind the notation used in the Navier-Stokes equation modelling the relevant mathematical structures: differential operators and the like. These mathematical structures may, in turn, be used to model physical systems such as fluid flowing through a pipe but this is not the modelling role we are claiming for the notation. There can be different models of the same structure (e.g., different notations for the natural numbers) each highlighting different features of the mathematical structure in question and some better than others for the purpose at hand.Footnote 28

We are thus suggesting that mathematical notation can be thought of (in admittedly Platonist terms) as representing a target system (e.g., a mathematical structure or the mathematical objects in such a structure), with key properties of the systems in question encoded in the notation (e.g., the iterative property of the natural numbers mirrored in the notation).Footnote 29 This is almost enough for mathematical notations to join their musical counterparts as models. Given the account of models sketched in the previous section, we also need to be able to specify a purpose for the notations in question. As we have already seen, mathematical notation can be used for calculations (e.g., the Hindu-Arabic notation for the natural numbers), for gaining understanding of the system (e.g., ordered pair notation and the accompanying geometric interpretation of the complex numbers), for aiding proofs of theorems (e.g., the algebraic notation invoked for the straight-edge-and-ruler geometric constructions, and finding new and interesting lines of research (e.g., the site-swap notation). It is thus appropriate to think of both musical and mathematical notations as models.

There are several things to be said in favour of this modelling view of notation. The first is that musical and mathematical notations are seen to be richer and more interesting than under the alternative view that notation is merely a system of conventional names for the objects of interest (e.g., musical works or mathematical structures). And this rings true with the respective practices, where notational systems are, indeed, active players in musical and mathematical activity and are the subjects of a great deal of attention. The modelling picture helps make sense of this.

That does not mean that there is a well-developed account of how good models work, but thinking of musical and mathematical notations as models, in effect, reduces two problems to one. Understanding more about the way models work will help shed light on mathematical and musical notation. Even with the current understanding of scientific models, there is a great deal that might be applied to notation. For example, appreciating the role that minimal models play in scientific investigation naturally invites questions about whether there are examples of minimal notations that serve such purposes in music or in mathematics.Footnote 30 We can also appeal to the literature on abstraction and idealisations in scientific models in understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of various notational systems in music and mathematics.

Another interesting consequence of the view argued for here is that in some cases there is very little, if any, significant difference between notation and diagrams. The latter are clearly models and we’re suggesting that notational systems are similar in at least this respect. This is interesting because, in mathematics circles, at least, it is often assumed that there is a clear distinction between notation (which is algebraic) and diagrams (which are pictorial). (The line is more blurred in musical circles.) For example, the orthodox view in mathematics is that diagrams cannot provide a proof of a theorem; diagrams can, at best, serve as pedagogical devices.Footnote 31 If what we are suggesting here is correct, the difference, if any, will not amount to much, for both diagrams and notation can serve as models and that’s what is most important. In any case, the modelling view of notation will provide a new perspective on the debate over diagrammatic proofs.

We have argued that notation can be thought of as a kind of model of the music or mathematics in question. We have noted several advantages of this way of thinking about notation. Apart from anything else, it helps to make sense of debates about the best and most appropriate notations in both music and mathematics. In any case, similarity between the roles of musical and mathematical notations is remarkable and constitutes another interesting connection between music and mathematics.Footnote 32