1. Defining optimization

Optimization is grounded in the notion of improving upon something that has already been shown to work rather than coming up with something entirely new. As a concept, optimization is thorny because it exists more in theory than in practice. In other words, optimization implies striving to improve existing options without necessarily reaching an optimal endpoint. Indeed, there is unlikely to be a single optimal approach because what is optimal in one context may not be optimal in another. Beyond conceptual issues, optimization is also difficult to operationalize. In quantitative approaches to language learning, a typical way of demonstrating that an intervention works is by comparing a control group that does not receive an intervention to a treatment group that does. Assuming appropriate experimental controls have been implemented, if the treatment group outperforms the control group, then the gain for the treatment group can be attributed to the intervention itself. In this case, the intervention could be described as effective. This type of design and comparison has been the basis of much quantitative experimental research.

Yet, optimization requires going beyond such designs to consider how a particular intervention can be further improved. For instance, researchers might seek to alter some aspect of the intervention to increase the amount of gain that the treatment group achieves relative to the control. This would require a series of studies where an intervention is iteratively implemented and its efficacy assessed. Then, using the assessment data at each stage of implementation, the intervention can be altered in conceptually and practically motivated ways, and the updated intervention can then be tested again to see if the updated format leads to even greater improvements than those observed in the predecessor study (or studies). As this process plays out, the intervention should become optimized, in the sense that it should lead to better and better learning outcomes, including better retention and generalization of learned material. To be clear, not all changes will lead to positive results. Some changes may not lead to any appreciable gains, and others may actually have the opposite effect, producing slightly worse outcomes. Nevertheless, putting aside the results of individual studies, experimentation should help us improve the target intervention over time.

In an applied scientific community such as ours, where there are many researcher-practitioners developing and testing language interventions, a large body of research quickly accumulates, but that research is often conceptually and methodologically diverse. This is certainly the case with applied pronunciation research. One way to systematize this body of research is through meta-analysis, which can shed light on both the average effect (gain) that can be expected and the variables that moderate the size of that effect. Over the past ten years, the meta-analytic literature addressing various aspects of pronunciation instruction has flourished. This literature provides a strong foundation for optimizing instruction, insofar as it establishes an empirically informed benchmark for future experimentation. In other words, accumulated findings now allow us to create a quantitative roadmap for optimizing pronunciation instruction effects. This, in turn, should allow the field to provide better, more actionable information to language instructors on what the best (or at least, a better) approach might be.

I recognize that optimization is not simply about how much is learned. As a concept, it can also encompass the time required to learn and learner experience variables such as learner engagement and enjoyment, among others. In fact, if we assume that anything is learnable given the right instructional input, then optimizing instruction is fundamentally about making learning as efficient as possible. By that view, rather than asking how we can increase gains, we could ask how we can take learners from their current level of performance to 80% accuracy, for instance, in the shortest amount of time, however time is measured (instructional hours, training trials, etc.). To this operationalization, we might add a user experience perspective, asking how we can design interventions that lead to sizable performance gains and/or take learners to threshold in an efficient way while also ensuring that the intervention is engaging, enjoyable, and so on. Indeed, this last dimension of optimization might be one of the most obvious and important for us as practitioners, given that fostering a dynamic and engaging learning environment is an essential aspect of effective language pedagogy.

Although I view optimization as a multicomponential construct, consisting of the dimensions previously discussed and likely many others, in this paper I focus mostly on how we can rethink research practices to gain detailed, actionable insight into how to maximize instructional gains. I take a quantitative approach because it reflects my own background and research training, and I focus on gains as an informative measure of how effective an intervention is because it is the primary way effectiveness has been operationalized in quantitative research reports. I examine this issue within the context of second language (L2) speech learning, which is my primary research area.

My perspective has been shaped by the context in which and the population with whom I work: adult language learners, mostly but not exclusively university students, most of whom are learning Spanish as an additional language. Nonetheless, I believe that the principles I outline here are generalizable to other domains of language learning (vocabulary, grammar) and to other learner groups and learning contexts. Likewise, even though my comments are mostly aimed at researchers (and researcher-practitioners), I hope that my perspective will provide instructors with a useful framework for reflecting upon and evaluating instruction.

The paper is structured as follows. I begin by discussing the state of the art in pronunciation instruction before outlining four research principles that can help us develop more optimal instructional techniques: replicating, systematizing, longitudinalizing, and adapting our approach to experimental design. I provide worked examples of how to apply these concepts using my own research, but these examples should be taken as illustrative case studies that can be repurposed to examine a range of variables and hypotheses. Throughout this paper, I use the terms pronunciation intervention and pronunciation instruction as umbrella terms encompassing both speech perception and speech production training.

2. State of the art

Over the past two to three decades, interest in speech learning has increased exponentially, likely due to the development of both the theoretical and applied branches of L2 speech science. On the theoretical side, several models have been formulated and refined to explicate the speech learning process (e.g., Flege, Reference Flege and Strange1995; Flege & Bohn, Reference Flege, Bohn and Wayland2021). On the applied side, researchers have emphasized more ecologically valid and, indeed, ethical and attainable models for instruction, moving away from the concept of nativeness, which was a driving force for early research on accents, toward an intelligibility-based model (Levis, Reference Levis2021; Levis, Reference Levis2005). Methods have also been scrutinized and refined to provide insight into the diverse ways that pronunciation can be measured and how measurement choices affect the conclusions we reach (Saito & Plonsky, Reference Saito and Plonsky2019).

Bibliometric analysis has tracked the ideas that have shaped L2 learning scholarship (Zhang, Reference Zhang2019), including research on speech (Chen & Chang, Reference Chen and Chang2022), and a growing body of meta-analytic research has provided a baseline for understanding the amount of pronunciation improvement that can be expected on average (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jang and Plonsky2015; Mahdi & Al Khateeb, Reference Mahdi and Al Khateeb2019; Mahdi & Mohsen, Reference Mahdi and Mohsen2024; McAndrews, Reference McAndrews2019; Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2018; Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024, Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2025; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng and Zhang2021). These meta-analyses have addressed diverse topics of theoretical interest, including whether speech perception training has a spillover effect on speech production (Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2018; Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024), the benefit of high variability phonetic training (HVPT; Mahdi & Mohsen, Reference Mahdi and Mohsen2024; Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2025; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng and Zhang2021), and computer-assisted pronunciation training (Mahdi & Al Khateeb, Reference Mahdi and Al Khateeb2019). Synthetic research is important because it provides us with a point of comparison for current and future work. Put another way, if we understand how much improvement we can expect on average, then we can set that amount of improvement as a baseline for determining whether an intervention is more effective than an alternative intervention and, by extension, whether the target intervention is likely to provide a better-than-average outcome.

The fact that we have a growing body of pronunciation meta-analyses is advantageous because the range of pooled estimates can serve as a set of boundary conditions, where we could, for instance, adopt the stance that any intervention falling below the lowest effect size (or the lower limit of its 95% confidence or credible interval) should be implemented with caution, if at all. Regardless of whether we adopt such a stance, the point remains that meta-analyses provide us with critical information that we can use to make decisions that align with the values we hold as researcher-practitioners, such as how effective an intervention needs to be for it be considered effective enough to implement. After all, interventions are not resource neutral.

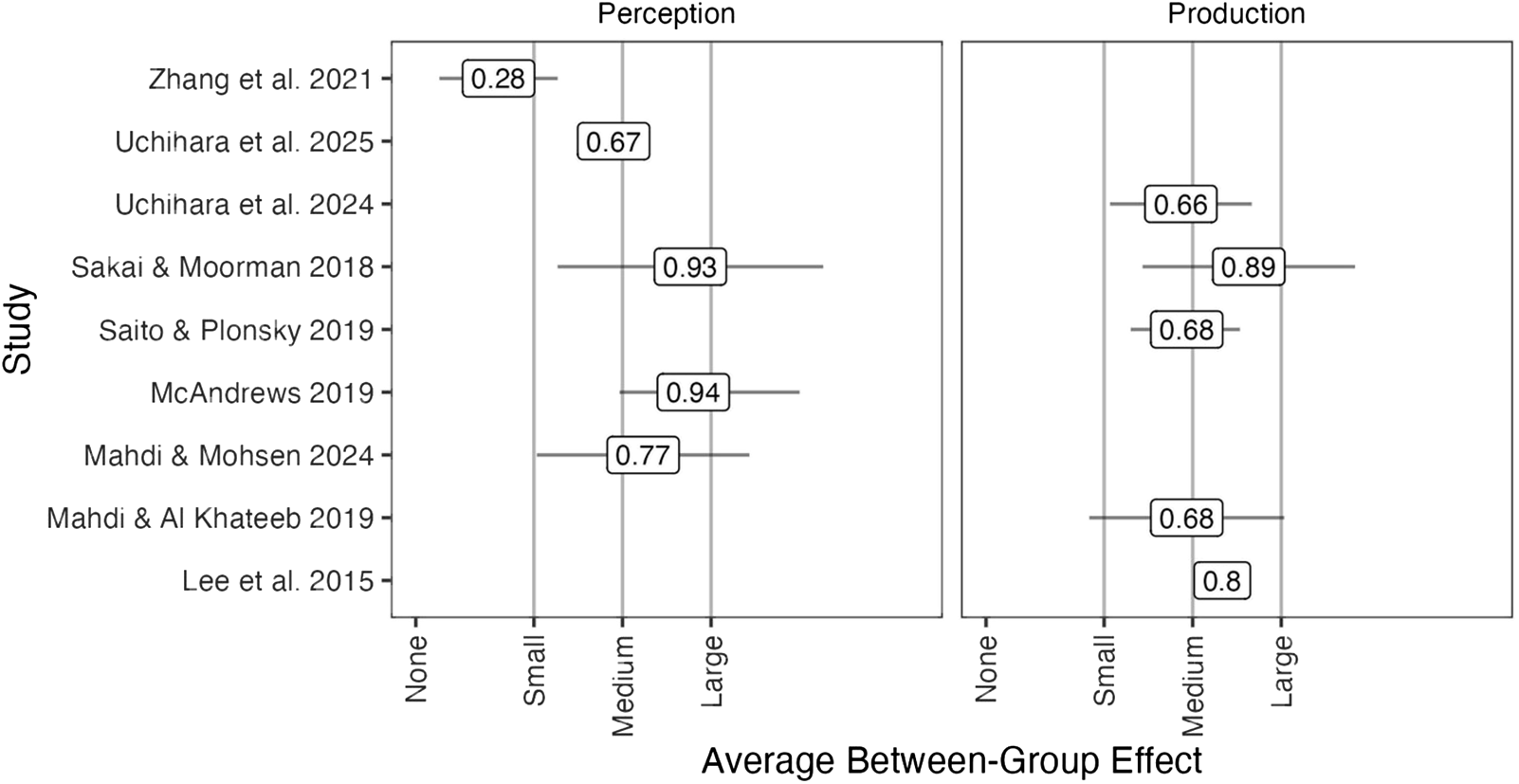

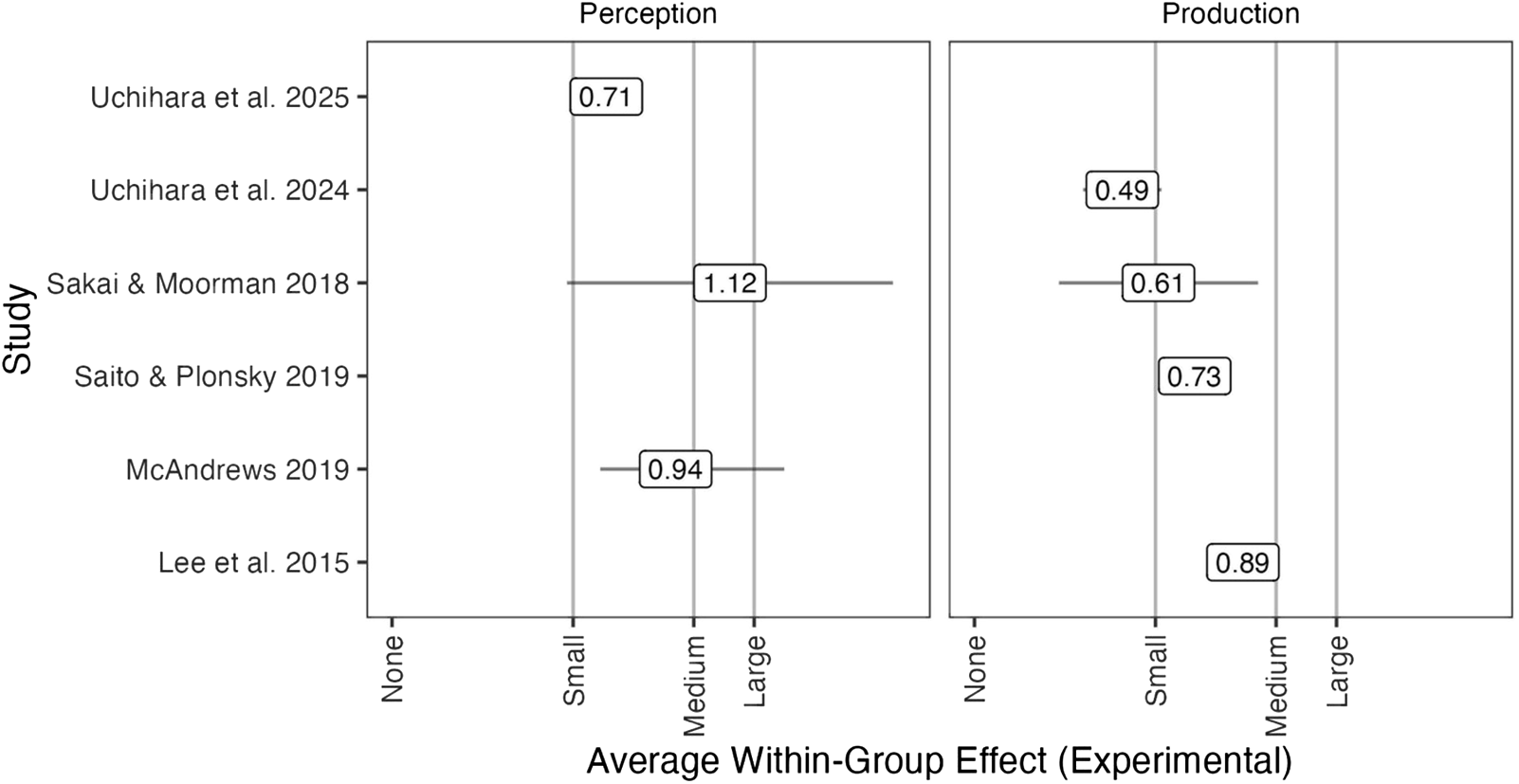

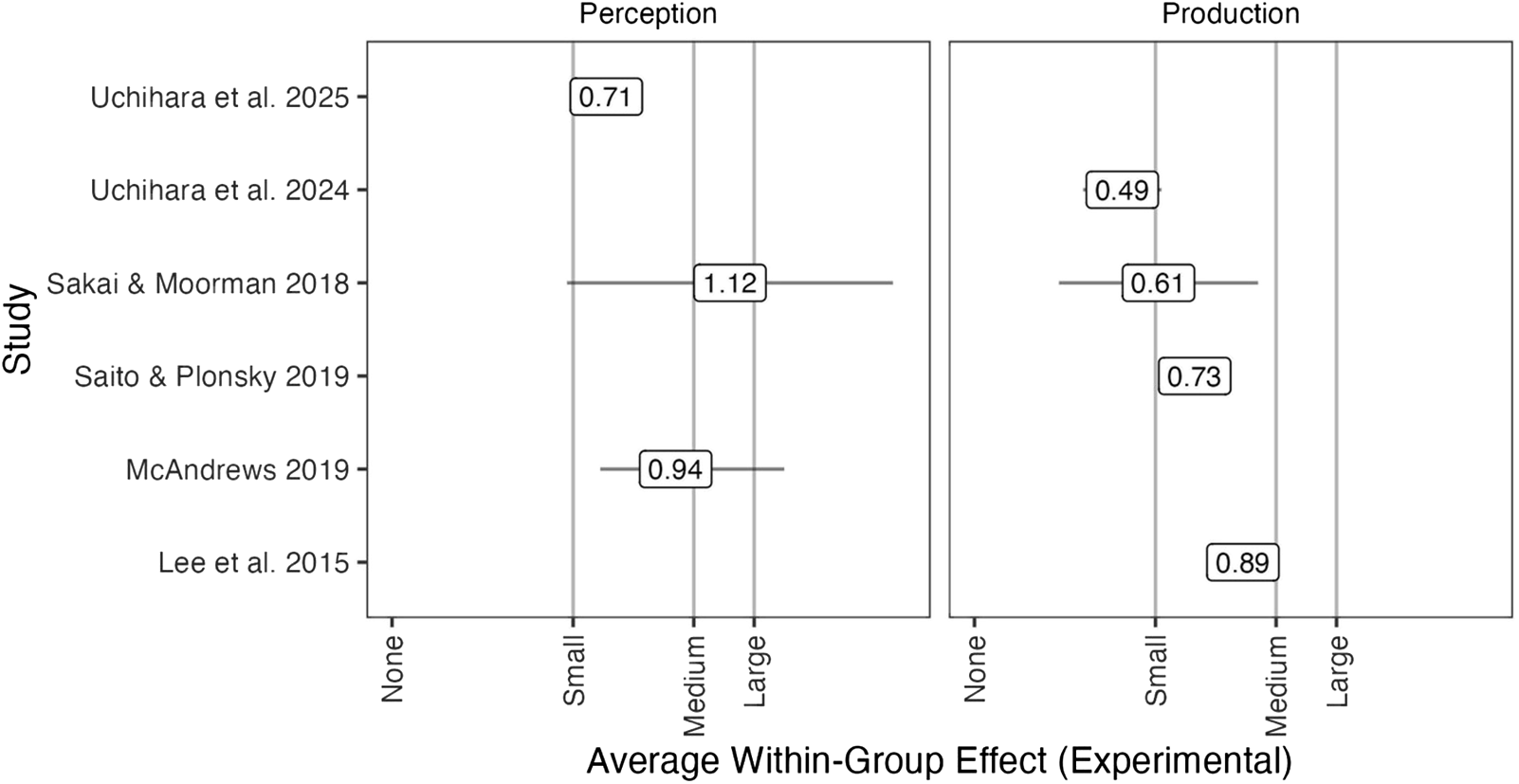

To facilitate discussion, in Figures 1 and 2, I have extracted and plotted effect size estimates from a selection of published pronunciation instruction meta-analyses available at the time of writing. It is important to bear in mind that each meta-analysis addressed a particular research question, which means that the estimates are best interpreted within the context of that question and the corresponding approach to study identification and screening. Despite the fact that these estimates are based on diverse substrands of pronunciation instruction, plotting them together provides useful information on the general range of instructional effects that have been observed.

Figure 1. Between-subjects effect sizes in published pronunciation instruction meta-analyses.

Figure 2. Within-subjects effect sizes for experimental participants in published pronunciation instruction meta-analyses.

In Figure 1, I have plotted the between-subjects pooled effect size estimates, creating separate panels for perception gains (left) and production gains (right). These effect sizes represent the average amount the treatment group can be expected to improve relative to a control group who either does not receive instruction or receives an alternative form of instruction. The figure also contains whiskers extending around each estimate. These whiskers represent the confidence interval. The point estimate is the most plausible effect, given the data, and the confidence interval provides information on the potential range of the effect, which could be as small as the lower limit or as large as the upper limit. I have placed vertical lines at field-specific (second language acquisition) benchmarks for small, medium, and large effects (d = 0.40, 0.70, and 1.00, respectively; Plonsky & Oswald, Reference Plonsky and Oswald2014), and I have also included a tick mark at d = 0, which indicates a null effect or no significant difference between the treatment and control groups.

As shown, we can expect treatment learners to perform approximately 0.28 (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng and Zhang2021) to 0.93 (Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2018) standard deviations better than controls, on average, in the area of speech perception training. Findings for speech production training are similar, though the range of effects appears to be slightly narrower. Participants who receive production instruction can be expected to show a performance advantage ranging from 0.66 (Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024) to 0.89 (Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2018) standard deviations.

Figure 2 is the within-subjects version of the same plot, where the effect sizes can be interpreted as the average gain from pretest to posttest for treatment participants, irrespective of how control participants performed. Because within-subjects effects tend to be larger than their between-subjects counterparts, the small, medium, and large thresholds are shifted toward higher values (d = 0.60, 1.00, and 1.20, respectively). The estimates show that experimental participants improve by 0.71 (Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2025) to 1.12 (Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2018) standard deviations on average when the outcome is perception-oriented and from 0.49 (Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024) to 0.89 (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jang and Plonsky2015) standard deviations on average when the outcome is production-oriented.

These estimates, which are more generalizable than the results generated by any single study, provide strong evidence that pronunciation instruction is likely to be effective, and they also provide information on the likely magnitude of its effectiveness. If we accept that instruction works, insofar as it is likely to lead to some gain relative to a control group, then it seems worthwhile to reconfigure our research practices, prioritizing treatment-treatment over treatment-control comparisons. Though treatment-control comparisons are certainly warranted for some designs and research questions, that type of approach has limited potential for shedding light on how to make current approaches more effective. To do that, treatment-treatment comparisons, where one group receives an intervention known to be effective and another an intervention that could prove superior to the known technique, are needed.

Regarding treatment-treatment comparisons, in some cases there is a clear counterpart intervention to which a new intervention can be compared, but in others the counterpart intervention may not exist or may not be obvious. If that is the case, then meta-analytic estimates can provide a meaningful benchmark for determining what counts as effective. Averaging over the estimates given in Figure 1, we can assume that perception training should lead to a gain of 0.72 standard deviations. If we focus on HVPT, the Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Cheng and Zhang2021) and Uchihara et al. (Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2025) estimates are most relevant, in which case we can assume that an HVPT intervention should lead to a gain of 0.28 to 0.67 on average. Furthermore, because most meta-analyses include moderator analyses examining how various methodological features – learner variables such as proficiency, measurement variables such as the type of target structure (e.g., obstruents, sonorants, and vowels in Sakai & Moorman, Reference Sakai and Moorman2018), and training variables such as the length of the training – affect outcomes, benchmarks can be partially tuned to the specific research context, target, intervention characteristics, and so on. Meta-analytic estimates, when combined with moderator analyses, should allow researchers to set a reasonable threshold of how much learners can be expected to improve, on average, for a study with a similar design implemented in a similar context. Likewise, practitioners can use this information to determine how much their learners are likely to benefit from a particular approach.

In this section, I have focused on meta-analysis because this synthetic technique offers a high-level, panoramic view of effects in the field which, as I have argued, can serve as meaningful anchors for future empirical work (and pedagogical decision-making). At the same time, like any form of research, meta-analytic results must be contextualized and interpreted judiciously. Two concerns are worth mentioning. First, meta-analyses run the risk of reproducing and reinforcing a publication bias in favor of significant, positive results. Many meta-analyses include heterogeneity and bias corrections for this reason (e.g., Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2025), but overall, it seems reasonable to assume that some bias persists even after correction. Thus, estimates may be somewhat inflated relative to what we can expect to observe in practice. Second, meta-analyses bring together a principled set of studies on a topic, but those studies are conducted in diverse settings, using diverse methods. Big questions can often be asked and answered, but some of the more nuanced, “smaller” questions that can help us optimize a specific instructional paradigm or approach may not be answerable because there simply may not be enough research in that area to produce reliable estimates. After all, it is impossible to synthesize research that does not exist. Thus, even though meta-analysis is a powerful tool, it does not eliminate the need for a more principled and systematic approach to research design. Such an approach can help us generate deep insights into how to improve the interventions we already have, interventions that have been shown to be effective. From an instructional perspective, it seems reasonable to focus on improving what we have rather than developing, testing, and offering an ever-expanding buffet of instructional options. In the following sections, I discuss four research design principles that can drive the field toward a better understanding of how to develop optimal pronunciation interventions.

3. Replicating our approach

Replication studies have become an important category of research in applied linguistics and language teaching. According to McManus, “replication provides a systematic framework for reconsidering, refining, extending, and sometimes limiting prior research findings” (Reference McManus2024, p. 1300), all of which are critical to achieving valid, reliable, and generalizable knowledge. Among their many benefits, replications can be used to address known research biases, for instance, by examining the extent to which L2 research findings generalize to nonacademic samples (Godfroid & Andringa, Reference Godfroid and Andringa2023). Replication principles can also be put to use in multisite research, providing a more nuanced portrait of whether findings are consistent across sites (Morgan-Short et al., Reference Morgan-Short, Marsden, Heil, Issa Ii, Leow, Mikhaylova, Mikołajczak, Moreno, Slabakova and Szudarski2018). In this way, replication can serve as a study-internal check on validity and reliability. There is a clear benefit to investing in replication studies in pronunciation instruction given that through replication we can understand the extent to which particular variables enhance or undermine instructional gains across contexts, samples, and target structures.

Replications can be conceptualized along a continuum with respect to the methodological link they maintain to the original research. In an exact or direct replication, the researcher aims to reproduce the methodology exactly, and such a replication can be considered confirmatory, in the sense that it serves as a litmus test for the original results. Exact replications are rare in applied linguistics and language teaching because even when researchers aim to reproduce the methodology of the original study exactly, if new data are collected, there are likely to be nontrivial differences in sampling and study implementation that render the replication distinct from the predecessor study. In a conceptual replication, many changes are made, such that the methodology may involve several deviations from the original design, though the hypothesis motivating the research is the same. In between these two endpoints lie close and approximate replications, where the researcher changes one or two well-motivated variables to investigate how those changes affect research outcomes (for an overview, see Porte & McManus, Reference Porte and McManus2019). Although replication research is gaining traction in the field at large, there are few replication studies in the L2 pronunciation literature, and fewer still involving an intervention. A complete review of replication pronunciation is beyond the scope of this paper, but I would like to discuss HVPT as an illustrative case of where replication studies could be especially helpful and complementary to the current research agenda.

There are three reasons why HVPT makes for a good case study. From an empirical perspective, it has been the most productive line of speech intervention research (for an overview, see Thomson, Reference Thomson2018). From a methodological perspective, it involves complex, yet impactful, decision-making related to how to set up training procedures, particularly with respect to the number of talkers and their presentation format. From a pedagogical perspective, accurate sound recognition is necessary for word recognition and higher-order speech processing, and it is also thought to be a necessary condition for accurate sound production. Thus, there is sustained interest in developing training techniques, like HVPT, that help learners perceive L2 sounds accurately.

HVPT can be traced back to Logan et al. (Reference Logan, Lively and Pisoni1991) and Lively et al. (Reference Lively, Logan and Pisoni1993), where across a series of experiments Japanese speakers of English participated in perceptual training targeting the English /l/-/ɹ/ contrast. Some groups were trained using stimuli produced by one talker, whereas others were trained with stimuli produced by five talkers. Furthermore, some groups were trained with stimuli where the contrast was embedded into few phonetic contexts, whereas others were trained with stimuli where the contrast was embedded into a much more diverse set of phonetic contexts. The goal was to understand how variability during training, delivered through talkers or phonetic contexts, affected participants’ learning, retention, and generalization. Overall, based on between-group comparisons, the authors concluded that higher variability promoted better perceptual learning. Until Brekelmans et al. (Reference Brekelmans, Lavan, Saito, Clayards and Wonnacott2022), no researcher or team had attempted to replicate the original HVPT research.

There are many explanations for why a replication of this research may not have been undertaken despite keen interest in the topic, including the time and resources necessary, and the misguided belief that replication studies are not original research.Footnote 2 It is also easy to forget that studies are naturally constrained by the conceptual, methodological, and technological affordances of the time, which in and of itself can present a compelling rationale for replication. As tools and methods evolve, more complex and empirically rigorous designs and analysis techniques may become available that can provide a stronger litmus test for findings. To that point, the between-group comparisons from Logan et al. (Reference Logan, Lively and Pisoni1991) and Lively et al. (Reference Lively, Logan and Pisoni1993) that formed the conceptual bedrock upon which HVPT research has been built were based on data from six participants!Footnote 3 Brekelmans et al. (Reference Brekelmans, Lavan, Saito, Clayards and Wonnacott2022) increased the sample to 166 participants, ensuring adequate statistical power, while addressing several other methodological limitations that might have had an impact on findings. The authors did not find evidence for a high variability advantage, but they nonetheless noted that “there is … a clear case for future work to determine how and under what circumstances variability can support and boost the efficacy of phonetic training” (p. 21). Perhaps a case can be made for replicating Brekelmans et al.’s (Reference Brekelmans, Lavan, Saito, Clayards and Wonnacott2022) replication (e.g., a close or approximate replication involving a target structure other than English /l/-/ɹ/), but it is also worth considering what other replication studies could be beneficial in the HVPT research landscape, with an eye toward developing paradigms that work well for diverse structures and learner groups.

Much HVPT research has focused on the amount of variability in the input. Another issue, however, is how that variability is structured and delivered during training. In training sets consisting of multiple talkers, stimuli can be blocked by talker or interleaved. In a blocked format, stimuli from one talker are presented back-to-back, which means that from one trial to the next, the listener is exposed to input from the same talker. In an interleaved format, on each trial, the listener can be exposed to input from any talker. Blocking and interleaving can therefore be referred to as low versus high trial-by-trial variability options.Footnote 4 The original HVPT research included a blocked design.Footnote 5 Although trial-by-trial variability was not the object of empirical focus in the Logan et al. (Reference Logan, Lively and Pisoni1991) and Lively et al. (Reference Lively, Logan and Pisoni1993) studies, subsequent research suggests that interleaving (high trial-by-trial variability) might slow learning down for some learners.

Perrachione et al. (Reference Perrachione, Lee, Ha and Wong2011) showed that learners with a low aptitude for pitch perception struggled to learn a four-way tonal contrast in a high variability, interleaved format but performed better in a blocked format. To my knowledge, no one has attempted to replicate Perrachione et al. (Reference Perrachione, Lee, Ha and Wong2011), nor has anyone compared blocked versus interleaved training in a single design, holding all other elements of methodology constant. In fact, blocking has become the default, perhaps due to a combination of the Perrachione et al. (Reference Perrachione, Lee, Ha and Wong2011) findings and our collective propensity to reproduce previous research methods. A close replication could involve replicating the Perrachione et al. (Reference Perrachione, Lee, Ha and Wong2011) study, using the tonal contrasts included in that study but changing, for instance, the sample. In an approximate replication, the sample could be changed, but the training target could also be modified to examine if training format has an impact on, for instance, segmental learning (e.g., the /l/-/ɹ/ contrast featured in the original HVPT research). Such a replication would respond directly to Brekelmans et al.’s (Reference Brekelmans, Lavan, Saito, Clayards and Wonnacott2022) call for more research on the role of variability during training, in this case the effects of overall and trial-by-trial variability and their relationship to perceptual learning. This is one example, but there are many other training paradigms and approaches that could be replicated (for discussion with additional examples, including examples focusing on production training, see Nagle & Hiver, Reference Nagle and Hiver2024).

In summary, replication studies must be viewed as a necessary and complementary addition to the current research agenda (and, indeed, to our own individual research programs). Like all research, replication comes with its own set of challenges, but those challenges should be contextualized within and offset by the vast potential of this research mode to consolidate, and in some instances perhaps even reshape (Brekelmans et al., Reference Brekelmans, Lavan, Saito, Clayards and Wonnacott2022), the state of the art in pronunciation instruction.

4. Systematizing our approach

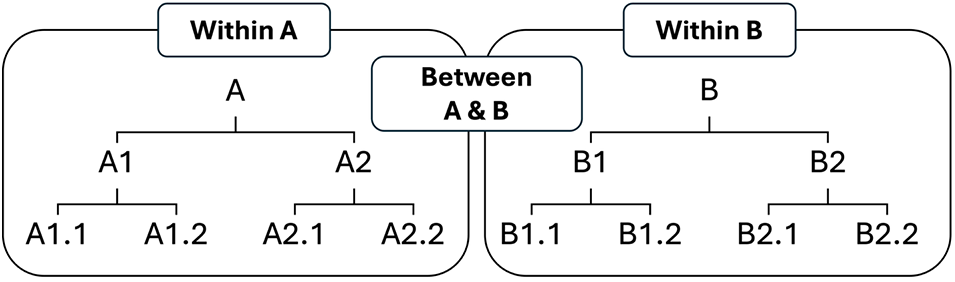

Replication research, by its very nature, flows from previous work. Yet, its principles can also inform novel research because at its core replication is about taking a systematic approach to study concept and design. Given the rapidly expanding knowledge base of what works for pronunciation instruction, in many instances an appropriate design would involve comparing two treatment groups. When this approach is adopted, there are two basic options for study design. On the one hand, two qualitatively different instructional methods can be compared, with the goal of determining which method is more effective than the other. This is a between-methods design, where the methods may bear little to no relationship to one another. The practical outcome of this research is that we can say which of these methods produces better results, but we cannot definitively determine what makes that approach more effective than the other because the methods are likely to differ on many variables, any (combination) of which might be responsible for the observed gains. Another option is to compare two methods that are closely related or, more precisely, to compare two or more variations of a single overarching method. In this within-methods design, the goal is to determine which version of the target method is more effective by isolating specific intervention variables.

Both types of studies can contribute meaningful information to what works for pronunciation instruction, but the within-methods design currently has more potential to advance the state of the art. If we continue to pursue between-methods research, we will generate more and more instructional paradigms. This breadth-based approach could prove overwhelming for practitioners, who may feel uncertain about which paradigm(s) to adopt given an ever-expanding set of options. Conversely, if we focus on within-methods research, we can refine and optimize the paradigms we already have, resulting in deeper knowledge, including perhaps better insight into how to adapt a paradigm depending on the learning context and problem.

Between- and within-method designs are schematized in Figure 3. The between-method comparison would involve moving across the hierarchy, comparing A to B, whereas the within-method comparisons would involve moving down it, comparing two or more versions of A to one another and/or two or more versions of B to one another (e.g., A1 to A2, A1.1 to A1.2). Moving down the hierarchy within methods also implies nesting, that is, that A1.1 and A1.2 are both variations of method A1 that could be compared if, for instance, A1 is shown to lead to better outcomes than A2. Nesting also means that submethods are closely related, insofar as A1.1 and A1.2 might differ with respect to one or two intervention features, whereas in the between-methods approach, A and B are likely to differ on many different features simultaneously.

Figure 3. Research designs comparing different instructional approaches.

Admittedly, research paradigms are complex and therefore may not fit neatly into the hierarchical structure shown here. For instance, there may be an area of pronunciation instruction where variables are already confounded at an intermediate level (A1 and A2), in which case those confounds would be passed to sublevels, complicating the conclusions that can be drawn. This hierarchical conceptualization can hopefully be used to sort out and resolve some of those confounds by providing researchers with a framework for carefully considering and defining in clear terms what makes one (version of an) intervention different from another. This mental map is also useful from a planning perspective, insofar as it encourages researchers to be proactive about reducing differences to the extent possible, for the sake of clarifying the effect of specific target variables. It also bears mentioning that not every version of every intervention paradigm should be tested and compared. In other words, not all variables merit evaluation. Any candidate variable should be carefully motivated based on current theory and practice.

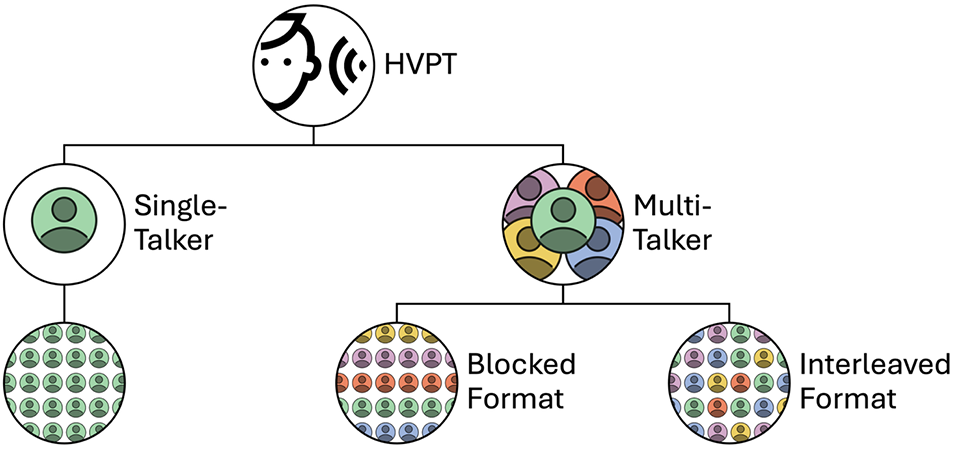

If we situate HVPT research within this framework, we can see that the current state of the art primarily involves two variability-driven manipulations: the number of talkers, which has principally been studied by comparing single- to multi-talker training (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng and Zhang2021); and the presentation format, or whether talkers are blocked or interleaved, though that issue has received less empirical attention. We could schematize the current state of research hierarchically as in Figure 4. In this schematic, talkers are represented by different colors. I have arranged presentation format horizontally in rows. In the blocked format, there is one talker per row, such that moving from left to right the listener would hear stimuli produced by a single talker before moving to a new talker in the next row. In the interleaved format, this is not the case because all talkers appear in all rows, which reflects the fact that from one trial to the next the listener could receive a stimulus produced by any of the talkers. In single-talker designs, there is no possibility of contrasting interleaved and blocked talker formats because there is only one talker, which is why there is only one subcondition under the single-talker design (though it would be possible, for instance, to compare interleaved and blocked formats for phonetic contexts using a single talker but multiple phonetic environments; Fuhrmeister & Myers, Reference Fuhrmeister and Myers2020). Additional layers or architecture could also be added, but to keep the figure manageable, I have focused on number of talkers and presentation format.

Figure 4. Schematic representing two layers of experimental manipulations in HVPT research: number of talkers and presentation format.

Variability has been fundamentally conceptualized as related to the number of talkers included in the training, notably the comparison between single- and multi-talker training conditions. To be clear, all training includes within-talker variability because multiple unique samples are recorded from each talker. Even in a single-talker paradigm, listeners are exposed to acoustically distinct training stimuli. Consequently, in multi-talker training, increasing the number of talkers means increasing the amount of between-talker variability and by extension the overall variability in the training set. If this type of between-talker variability is beneficial for learning (insofar as it may be a better representation of the way the target category can be realized), then it stands to reason that increasing or decreasing the number of talkers (beyond the binary comparison of one versus multiple talkers, where multiple could refer to any number of talkers greater than one) could have an impact on learning. Likewise, interleaving is generally conceived of as a more cognitively demanding presentation format, especially when combined with talker variability. Whereas interleaving might highlight differences between categories, when it is combined with categories produced by multiple talkers it could have a destabilizing effect on learning. This is why presentation format has received some attention in the multitalker training literature (Perrachione et al., Reference Perrachione, Lee, Ha and Wong2011). A more complex HVPT design could be envisioned by crossing single and multitalker training (with two levels of multitalker variability) with presentation format, on the view that different types and amounts of variability could synergistically regulate learning (for meta-analytic evidence, see Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng, Zou and Zhang2025).

This expanded set of options is given in Figure 5, where I have arbitrarily chosen three- and five-talker options as representative subconditions within the multitalker approach. This schematic could be modified to target other variables such as the number of phonetic contexts trained (which is another important source of variability in the input; see Fuhrmeister & Myers, Reference Fuhrmeister and Myers2020), response options (Fouz-González & Mompean, Reference Fouz-González and Mompean2021), and training task (Cebrian et al., Reference Cebrian, Gavaldà, Gorba and Carlet2024). The point is that the schematic given in Figure 3 is an abstract and flexible architecture that can accommodate a range of variables and subconditions of interest. Furthermore, although I have focused on HVPT for this example, due to my own interests and the prevalence of this technique in the literature, other paradigms, such as visual feedback training, training with and without corrective feedback (Saito & Lyster, Reference Saito and Lyster2012), or training with and without explicit phonetic information (Kissling, Reference Kissling2013) could be similarly schematized.

Figure 5. Schematic representing additional layers of experimental manipulations under the multitalker approach.

One thing is designing a study, another is carrying it out. In Figure 5, which crosses number of talkers with presentation format, there are five groups into which participants can be randomized. Including multiple experimental groups in a single design is beneficial because it helps control potential confounds that might get introduced if separate studies are run. At the same time, there are practical barriers to carrying out multigroup research. Assuming a modest sample size of 20 learners per group, the study shown in Figure 5 would require at least 100 participants. In perceptual training research, participants also complete multiple sessions. In their meta-analysis of perception training studies, Sakai and Moorman (Reference Sakai and Moorman2018) established a threshold of six sessions, where fewer than six was deemed a short intervention and more than six a long intervention. In a laboratory study, accommodating 600 individual sessions is likely to prove difficult, and keeping participants on a consistent training schedule to ensure a consistent intersession interval seems all but impossible. Online participant recruitment is an option, but online recruitment can be expensive and result in significant attrition rates. For multigroup studies, I therefore propose an emphasis on classroom-based designs, when possible. This approach is advantageous because a subset of groups can be run each semester, and, presumably, from one semester to the next, students enrolled in the same course provide a comparable participant pool, ensuring consistency across experimental iterations. Classroom-based research also has the potential to recruit a more diverse and representative learner group while also creating completion conditions that are more realistic and therefore more representative of the ways in which learners might actually engage with training in the real world (e.g., at home, using computer- or mobile-assisted methods).

As a starting point and proof of concept, Germán Zárate-Sández (Western Michigan University), Shelby Bruun (The University of Texas at Austin), and I have integrated HVPT training into introductory Spanish language courses at our respective institutions. Our initial interest was in how the number of talkers included in multitalker perceptual training affects learning gains, a variable which has been critical to HVPT research since its inception. We ran a pilot study during the Fall 2023 semester, and in each subsequent semester, we have maintained our focus on the number of talkers while altering one additional intervention variable. As shown in Table 1 and visualized in Figure 6, the groups we have run have been identical from one semester to the next: a control group that did not receive training and HVPT groups trained on two (2T) and six (6T) talkers.Footnote 6 We also held the number of sessions constant across semesters for practical reasons. Because we integrated the training into the language program, such that students receive credit for completing testing and training activities, we needed to create a design in which all students would complete the same number of training sessions to ensure a consistent and equitable amount of credit-bearing work.

Figure 6. Schematic of experimental groups and the semesters in which they were run.

Table 1. Summary of HVPT studies run

Note: 2T=two-talker, 6T=six-talker. N refers to the total sample (including individuals who completed all six training sessions, as intended, and individuals who completed <6 sessions). Training was incorporated into a pronunciation enrichment activities component that was part of the students’ course grade. We therefore asked students to give us consent to use their academic data for research purposes. N reflects the number of students who consented to data use for research.

From Spring to Fall 2024, we manipulated the duration of training sessions, halving the number of trials per session, and from Fall 2024 to Spring 2025, we manipulated trial-by-trial variability by moving to an interleaved presentation format. Our design decisions have been driven by our theoretical interests and by insights gleaned from preliminary data analyses. For instance, we began (Spring 2024) with a blocked presentation format because blocking is generally viewed as facilitative of learning. Analysis of the testing data from that semester showed that trained learners improved significantly more than the control learners, with no significant difference between the 2T and 6T conditions (Nagle, Bruun et al., Reference Nagle, Bruun and Zárate-Sández2025). Additionally, preliminary analysis of the training data showed that improvement tended to level off, as participants approached ceiling performance, and learner feedback was consistent in indicating that they found the training sessions to be too long.

All of this suggested that we might be able to reduce the number of trials without compromising learning, which could also lead to a better overall learner experience. This is why we moved directly to the 60 trials/session format (Fall 2024) without testing the effect of interleaving at the 120 trials/session level. Likewise, we moved to the interleaved format at 60 trials/session (Spring 2025) because we hypothesized that learners might find the training more engaging if talkers were interleaved (as opposed to hearing the same talker repeatedly). Thus, our motivation was not to promote learning because we had already achieved that in the first semester, in the 120 trials/session blocked format. Rather, we were hoping to enhance the user experience. Furthermore, we found the comparison between blocked and interleaved formats at the 60 trials/session level theoretically interesting because interleaving (introducing greater trial-by-trial variability) could be detrimental when there are fewer instances from which to learn (60 trials), especially in a high talker variability condition (6T).

There are several ways to analyze the data to gain insight into how to optimize the HVPT model we have developed. One option is to analyze the effect of the number of talkers within formats, treating each semester/cohort as an independent sample. This would likely be a first step toward demonstrating that the training paradigm we implemented each semester was effective (that each semester, the treatment groups outperformed the control). Another option is to compare trials/session conditions within talker groups. More concretely, this would involve comparing 120 and 60 trials/session conditions within the 2T and 6T conditions. Finally, we could hold the number of trials/sessions constant, comparing blocked and interleaved formats within the 60 trials/session format to examine the effect of presentation format, albeit only for the 60 trials/session format. Other, more complex, analyses are possible involving both the testing and training data. The point is that these progressive iterations on study design have laid the groundwork for a set of principled analyses that collectively can illuminate which combination of variables (which format) leads to the best learning outcomes, at least as far as this target structure is concerned (for an excellent example of reporting multiple training studies, see Obasih et al., Reference Obasih, Luthra, Dick and Holt2023). Before conclusions can be drawn, however, the same set of studies would need to be carried out with other target structures, which we intend to do in upcoming semesters (cf. the last row of Table 1).

5. Longitudinalizing our approach

In intervention research, learning is typically evaluated on one or more posttests given shortly after the intervention has concluded. This testing format assumes that learning should be most evident immediately after training. It also assumes that the amount of learning observed is tied to when posttesting occurs relative to the offset of training. Typically, this consideration is framed in terms of how well and over what interval learning is retained. The meta-analytic data (effect sizes) I presented previously are based on comparisons between a pretest and an immediate posttest. Several meta-analysts have called for meta-analytic data on retention (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jang and Plonsky2015), but such data are harder to come by because fewer studies include delayed posttests. For this same reason, when meta-analyses do examine retention, the number of studies on which average effect sizes are based tends to be smaller (e.g., ten in Uchihara et al., Reference Uchihara, Karas and Thomson2024; two in Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng and Zhang2021), which can prevent authors from reaching robust conclusions about retention and the factors that affect it. Testing retention is important because even if two interventions seem to promote similar amounts of learning on an immediate posttest, they may have a differential impact on retention (as measured on one or more delayed posttests). In the most extreme (albeit unlikely) case, backsliding could be of such magnitude that there is little to no difference between pretest and delayed posttest, which would indicate that the intervention did not lead to durable learning. Several authors have written about retention in pronunciation research (Rato & Oliveira, Reference Rato, Oliveira, Kickhöfel and Jeniffer Imaregna Alcantara de Albuquerque2023), and I have also published on this topic (Nagle, Reference Nagle2021), so I will not comment on it extensively here. Instead, I turn to a related but much further-reaching issue: situating interventions within a longitudinal framework.

In their narrative review of longitudinal research, Ortega and Iberri-Shea observed that “many questions concerning second language learning are fundamentally questions of time and timing” (Ortega & Iberri-Shea, Reference Ortega and Iberri-Shea2005, p. 27). When thinking about time and timing, it is useful to distinguish between researcher and practitioner perspectives. As practitioners, we are accustomed to thinking about both constructs. Time, from a pedagogical perspective, can be defined in relation to how long it takes a learner to achieve a certain outcome, which is anchored to the contextual affordances, instructional or otherwise, the learner has at their disposal and how they make use of them. As we gain practical experience as language instructors, we develop an intuitive understanding of the developmental time course for various aspects of language proficiency, including pronunciation. Timing is a more active concept that requires us to reflect upon how we can sequence pedagogical activities to achieve maximum impact. Again, through practical experience, we develop a sense of what works and when it works best, often in relation to particular activities in specific courses (courses being the unit of time inherent to academic settings).

As researchers, time is something we observe and model in experimental and longitudinal work (Nagle, Reference Nagle2021). Much research has gone into understanding learner trajectories, and that research can inform pedagogical decisions (Derwing, Reference Derwing, Levis and LeVelle2010). In quantitative longitudinal work, time is included as a predictor in statistical models to examine the rate (and in some cases the shape) of development. Timing has also been central to L2 research. For instance, in work on developmental sequences, timing is encoded in the concept of developmental readiness (e.g., Lightbown & Spada, Reference Lightbown and Spada1999). Yet, in most cases, timing has been conceptualized as an observed as opposed to an experimentally manipulated variable.

I propose a different approach, where researchers track an appropriately large cohort longitudinally and assign subcohorts to different timing conditions. In this design, timing is an experimentally manipulated variable where each subcohort receives instruction (participates in the pronunciation intervention) at a different moment in their instructional trajectories. In this design, the timing of the intervention needs to be anchored to conceptually and/or academically critical turning points in language education, such as the onset and offset of intensive communicative instruction, immersion, and so on. The research would include the usual pre- and posttests, carried out shortly before and after the intervention, which would serve as tests of short-term, intervention-driven learning. With respect to time – that is, the total window of observation over which participants are tracked – the research would encompass a much longer developmental window that could shed light on whether the timing of the intervention fundamentally alters the rate, shape, and even end state of development. A truly longitudinal perspective, where learners are tracked over multiple years of language study, also reminds us that in an instructed context development is driven not by a single intervention, nor by a single variable, but by a set of instructional activities, sequenced and delivered over time at specific, conceptually and practically motivated intervals.

I have schematized a potential design in Figure 7. In this figure, the same group of individuals is tracked over time, such as over the course of a four-year university degree program. The solid black line represents the group that progresses through the usual communicative language sequence. The dotted and dashed lines represent two potential interventions (such as training with two talkers and six talkers, or training with 120 trials and 60 trials per session) and the two colors represent different moments at which those interventions could be implemented (earlier, in year 1, shown in orange, versus later, in year 2, shown in green). The boxes represent the typical (narrowly constructed) approach to measurement, centered on the intervention itself. I have not included potential observation or data points along the lower x-axis representing the longitudinal window because I do not want to convey the idea that a certain number of data points is necessary or optimal. The number and timing of data points included depends on myriad conceptual and practical factors and is therefore best determined in light of the specific research objectives and context. It also bears mentioning that the trajectories are purely hypothetical and, in all likelihood, would not show such marked differences. However, they do serve to reinforce the view that in typical pre-post designs, the emphasis is on differences in posttest performance or pre-post gains, whereas when a more comprehensive longitudinal window is adopted, differences in trajectories can be examined. Crucially and most importantly, in this design, the researcher actively assigns participants to distinct timing conditions, with the goal of examining their impact on short- and long-term learning.

Figure 7. Hypothetical longitudinal intervention study showing two experimental formats delivered at two points: at the outset of intensive language study and during a pronunciation course.

The timing of the interventions would need to be coordinated with other curricular elements, and it would also be tied to the goal of instruction. When implemented early, such as during year 1, the goal might be to jumpstart learning; in year 2, if by that time learners were not showing much improvement on the target structure, then the goal could be to help learners improve on a structure that does not seem to show much automatic or natural development (Derwing, Reference Derwing, Levis and LeVelle2010). More complex designs are also possible. For instance, the same intervention could be implemented several times (format 1 in both year 1 and year 2), or a sequence of distinct interventions could be created and implemented (format 1 in year 1 and format 2 in year 2, or vice versa). A seemingly infinite number of timing options and combinations can be tested, but not all of those timing options and combinations are conceptually motivated and practically feasible. Thus, within constellations of possibilities, researchers need to make sensible and informed decisions about what is likely to work for their specific learner population in their research context. Out of this body of work, important generalizations can eventually emerge, generalizations that transcend population- and context-specific findings.

As an example, Jose Mompean (University of Murcia), Jonás Fouz-González (University of Murcia), and I have undertaken research on how the timing and intensity of HVPT affect the longitudinal development of L2 English vowel perception and production. In our study, we administer HVPT to one group of students in year 1, at the very outset of their degree program, and to another group in year 2, during a pronunciation course. We have chosen these two moments carefully, considering participant characteristics and the characteristics of the language curriculum in which students are enrolled. With respect to intensity, we implement HVPT over four weeks in both years, but the number of sessions participants complete over that period differs. In one format, participants complete four sessions, one per week, whereas in the other, they complete eight sessions, two per week, which provides the second group with double the amount of training input over the same training window. This is a two-by-two between-subjects design where we have crossed timing and intensity to create four experimental groups. We test learners immediately before and after training to quantify (short-term) training gains. Additionally, in line with the principles of longitudinal, developmental research, we track learners over time, outside of HVPT windows, to gain insight into overall trajectories in vowel perception and production.

In Nagle, Mompean et al. (Reference Nagle, Mompean and Fouz-González2025), we tracked a group of learners over their first two years of university-level intensive language instruction. We compared two single-intensity groups (four HVPT sessions), one trained in year 1 and the other in year 2. We found that both groups of learners improved as a result of HVPT. We also found that both groups improved outside of HVPT, likely as a result of the intensive communicative English courses in which they were enrolled. By the end of the two-year observation window, the two groups of learners had reached approximately the same level of accuracy in English vowel identification, which suggests that at least for the learners who participated in this initial study and for the timing options we implemented, timing did not matter much at all.

Longitudinal research is challenging because it is time- and resource-intensive and because participant attrition can be a threat to the validity and generalizability of the research. These issues are likely to be more pronounced in longer-term studies, such as the designs I have proposed here. Through careful planning, researchers can choose sensible options for timing manipulations and data collection points, balancing methodological rigor, especially temporal resolution (the granularity with which learning trajectories are represented), and feasibility. In our 2025 study, we decided that four data points, anchored around the year 1 and year 2 HVPT interventions, were sufficient to capture the type of learning we wanted to measure. Limiting data collection to four sessions was also necessary due to logistics, notably scheduling and data processing, and participant retention. Regarding the latter, we offered participants a small amount of compensation for their time and effort, and we felt that had we asked more of them, many would have opted not to participate in the study. We were able to maintain participants within each year, but there was notable attrition between years, which in my experience is common for research conducted in an academic setting. Thirty-seven participants completed the year 1 pretest, and 36 returned for the posttest. In contrast, only 23 returned for the year 2 pretest, with 23 completing the posttest. This attrition does not fully undermine the study – indeed, were that the case, longitudinal research would have little purpose – but it does suggest that it may be beneficial to think of running complex, multiyear designs collaboratively, at multiple sites, or to conceptualize such designs as long-term projects, with the goal of adding new samples to existing ones (for additional discussion, see Nagle, Reference Nagle2021).

In summary, longitudinal research offers the clearest insight into development, and longitudinally situated interventions the clearest insight into medium-to-long-term instructional effects. As is the case with all research methods, longitudinal designs come with challenges and opportunities. Thus, I encourage researchers who are interested in development to make longitudinal research a component of their research agenda and to seek out collaborations with like-minded colleagues. Beyond the designs I have discussed here, there are several excellent published reports that researchers can consult for additional, complementary ideas with respect to how to structure longitudinal data collection (Huensch & Tracy-Ventura, Reference Huensch and Tracy-Ventura2017; Mora, Reference Mora and Pérez-Vidal2014).

6. Adapting our approach

We are living in an era of rapid and unprecedented technological advancement. To be sure, technology has always been important to pronunciation teaching and research (for a review, see O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Derwing, Cucchiarini, Hardison, Mixdorff, Thomson, Strik, Levis, Munro, Foote and Levis2022). Early work had a strong emphasis on computer-assisted pronunciation training, and that line of research continues to be productive. Yet, smartphones have also become an essential tool in everyday life. In the Pew Research Center’s 2011 survey on smartphone ownership, only 35% of respondents reported owning a smartphone. In their latest survey, conducted in 2024, 91% of respondents reported owning a smartphone, including 98% of individuals in the 18 to 29 age bracket (Pew Research Center, 2024). The rise of smartphones has brought with it an uptick in research on mobile-assisted pronunciation teaching (Stoughton & Kang, Reference Stoughton and Kang2024). In the coming years, artificial intelligence will undoubtedly reshape the educational and research landscape. The appeal of technology, including artificial intelligence, is multifaceted, but two features are especially important to intervention research. First, technology can enable a highly individualized approach, whereby learners can practice and receive real-time feedback on the specific pronunciation problems they have. Second, it offers an opportunity to practice anytime, anywhere, especially in the case of mobile-assisted pronunciation training.

To take advantage of the individualization, adaptability, and convenience that technology-enhanced approaches afford, researchers must begin to investigate the principles that should guide adaptation. Instructors are used to adapting, but researchers are not necessarily accustomed to or comfortable doing so because empirical research is grounded in the notion of experimental control and isolation. Thus, research designs tend to be relatively fixed, so that any differences that are observed after training can be attributed to the training itself. Put another way, current practice is to devise an intervention and implement that intervention in exactly the same way for all participants. In fact, in this paper I have argued for a highly systematic approach that is predicated on these ideas. A systematic approach is valuable because it can provide precise insight into the variables that regulate learning, contributing to our knowledge of optimal instructional techniques. Nevertheless, another way to optimize instruction is to move in the opposite direction, making instruction more adaptive, which I define as a flexible approach that is responsive to learner performance and driven by learner (and instructor) insights. Crucially, as I explain below, this does not mean giving up experimental control. Instead, it moves experimental control away from individual variables toward the levers and thresholds that dictate the structure of the adaptive framework itself.

From an empirical standpoint, an adaptive approach begins with an overarching intervention framework that constrains the how, when, and why of adaptation. Although learners will ultimately participate in different instructional formats, as in all empirical work, there must be boundary conditions within which adaptive decisions can be made. An adaptive approach also implies more active data tracking because adaptive decisions are often tied to learner performance. For example, in their study on perception training, Qian et al. (Reference Qian, Chukharev-Hudilainen and Levis2018) determined that once learners reached an 80% cumulative accuracy threshold, they would advance to a new training target. Conversely, learners who did not reach that threshold would repeat the training block for the same target until the threshold was achieved. In their study, the set of training activities was fixed, but the number of blocks or cycles per contrast was adaptive, insofar as that number was driven by learner performance. In short, not everyone received the same amount of training input because some learners needed less input, whereas others needed more. Qian et al. (Reference Qian, Chukharev-Hudilainen and Levis2018) used a block-based accuracy threshold, but more dynamic trial-driven thresholds (e.g., responding correctly to 10% of trials in a row, which for the 120 trial/session and 60 trial/session conditions described previously, would be 12 and 6 trials).Footnote 7

Another option would be to create a model where the training activities change as learners become more proficient in their perception (and/or production) of the pronunciation target. For instance, using Qian et al.’s (Reference Qian, Chukharev-Hudilainen and Levis2018) 80% accuracy threshold, once learners achieve criterion they could move to a different training condition for the same target (e.g., from isolated words to words in sentences, from noiseless to noisy conditions). Furthermore, drawing upon the variables that have been foundational to HVPT research, the number and blocking of talkers could also be adapted throughout training. At the outset of training, a blocked multitalker format could be used. Once learners achieve an acceptable level of accuracy on that format, they could move on to an interleaved format.

At first glance, this approach may seem to loosen or lose all of the traditional experimental controls that are the hallmark of robust empirical designs. However, upon further inspection, it becomes clear that what needs to be transparent and reproducible is the decision tree that guides when and how to adapt training because the goal of adaptive research is to demonstrate that the adaptive framework itself is effective. Ultimately, learners will move through the same set of intervention activities, but they will do so at different rates (completing different numbers of blocks, trials, etc.), depending on their individual needs. One basic goal of adaptive research, then, is to determine if the thresholds set, and the sequence in which intervention activities are implemented, is effective. Across a series of adaptive studies, researchers could explore, for instance, if the 80% threshold Qian et al. (Reference Qian, Chukharev-Hudilainen and Levis2018) set is appropriate and realistic, or if some other threshold would be more effective. Comparing multiple adaptive frameworks can shed light on which framework appears to be most effective (for additional discussion, see Hiver & Nagle, Reference Hiver and Nagle2024).

Adapting our approach requires relying on technology, and technology has sparked concerns about computers, apps, and most recently artificial intelligence systems partially or completely replacing instructors. Such concerns are not unfounded in the language sciences because administrators have begun to view instructional faculty as expensive and expendable. Professional organizations such as the Modern Language Association and the American Association for Applied Linguistics have offered compelling arguments for maintaining language training. Here, I offer an empirically driven argument: technology-enhanced instruction is highly, if not completely, dependent on our shared intellectual work. Without investigator and practitioner insights into what works, technology-enhanced approaches are little more than empty shells devoid of content and pedagogical knowledge. Put another way, we provide the empirical evidence and pragmatic perspectives that guide how such approaches should function.

7. Conclusion

We have at our disposal an impressive array of proven pronunciation instruction techniques. We can continue to broaden our interventions, but an alternative and, in my view, more fruitful approach is to invest in optimizing the ones we already have. There is ample room to replicate existing findings, shoring up our knowledge of what works in relation to proven techniques. There is also ample room to move down the intervention genealogy, developing and testing approaches that are variants of known interventions. Placing those interventions in a broader longitudinal framework will help us understand their long-term impact. By engaging in longitudinal work, we can also gain a better understanding of how interventions fit into the suite of language learning activities in which learners choose to proactively engage (Papi & Hiver, Reference Papi and Hiver2025). As a final step, we can begin to relocate experimental control, focusing on how we adapt training rather than the surface format that the training ultimately takes. Taken together, these four research pathways, which demand that we reconsider research methodology, have great potential to provide relevant and actionable information for optimizing pronunciation pedagogy. To put it more concretely, this four-pronged approach should allow us to identify how to make current approaches even better and when to implement them for maximum impact. We can then provide instructors with the specific information they need to make informed decisions about what is likely to prove highly effective in their teaching. At the same time, these ideas cannot and should not be interpreted in an overly mechanistic way. Instead, they must be balanced with instructor perspectives if we are to develop an empirically grounded but pragmatically informed approach to pronunciation learning and instruction that is optimal for all stakeholders.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the organizers and the audience of the 17th International Conference on Native and Non-Native Accents of English, especially Anna Jarosz, for their interest in my work. I would also like to thank Pavel Trofimovich and reviewers, whose thoughtful feedback helped me improve the clarity and accessibility of this manuscript.

Competing interests

I declare none.

Charlie Nagle is Associate Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at The University of Texas at Austin. He studies second language pronunciation and speech learning, and the linguistic and learner variables that regulate development. He is especially interested in speech research methods and open speech science. His work has been supported by the National Science Foundation and the Fulbright Commission.